1. Introduction

The incorporation of objects into sound art installations continues to be adopted by current artists. This pairing is by no means a new phenomenon but has become more practically achievable than ever. Mo H. Zareei, in his 2020 article Audiovisual Materialism, attributes this to ‘advancements in computer-aided design and manufacturing technologies and increased accessibility of DIY and open-source tools, combined with wide-reaching access to online learning…’ (Zareei Reference Zareei2020: 362). This increased practicality lends itself to works being created that provide visual stimulus via the physical movement (and resulting sound) of featured objects. Examples in this category are typified by Zimoun, who often utilises multiple iterations of everyday objects and actuates them using simple motors to create multisensory installations (Zimoun 2023). Nicolas Bernier builds on this approach in one of his main tuning fork series of works, Frequencies (A), which, in addition to using solenoids to strike the forks, combines LED white light pulses emanating from a specially designed table used to perform the installation (Bernier Reference Berniern.d.). Both these artists celebrate the physicality of the objects involved alongside the sonic results: Zimoun, in that the only sound we hear is produced by the physical objects that make up the work, and Bernier, by interacting with the acrylic-mounted tuning forks, contrasted by the stark white light and synthesised audio.

Part of the effectiveness of these works lies in the ‘animation’ of the objects involved and how these movements are perceptually welded to the sounds we hear. The vast potential offered by combining visual movement alongside sonic material is attractive for many artists, including those from an electroacoustic composition background. Diego Garro ascribes this partly to a ‘technological convergence’ of the computer workstation (Garro Reference Garro2005: 1), which, as Maura McDonnell describes, is facilitated by video and photo editing software being ‘conceived of metaphorically as if they were sound editors’ (McDonnell Reference McDonnell and Knight-Hill2020: 252).

It is from this electroacoustic starting point that this article proposes a list of transformations to assist audiovisual composition choices in the context of object-based sound installations. Specifically, this method is aimed at works that use projection mapping to visually animate the objects in question, rather than via motors or other electromechanical means. Mapping can offer a greater range of visual manipulation than could be achieved by mechanical actuation aloneFootnote 1 . It also offers a higher level of complexity and metaphor compared to works that only use lighting fixtures. It also helps to further integrate the object or objects featured in the installations, given that, as Martina Stella argues, ‘…mapping confronts the spectator with two visual elements, the image and the medium, each loaded with its own meaning (…) The object on which the projection is expressed is thus decisive in the meaning and reception of the video’ (Stella Reference Stella, Schmitt, Thébault and Burczykowski2020: 63).

Two of my own recent installation works, 8040 (2021) and Paiste 36 (2023), both use projection mapping to modify the surface layer of the objects at the centre of the works. The former uses a Genelec 8040A active loudspeaker as the projection canvas, the latter projects onto a 36-inch Paiste Symphonic Gong set alongside a Genelec 7270A subwoofer. In both works, all the sounds heard (with varying processing) come directly from, or are associated with, the objects mentioned above. The creation of these works informed the research process that gave rise to the transformation strategies explained in this article. A Supplementary video is available showing brief excerpts from both works with annotated descriptions of some of the transformations in Tables 1 and 2 later in this article.

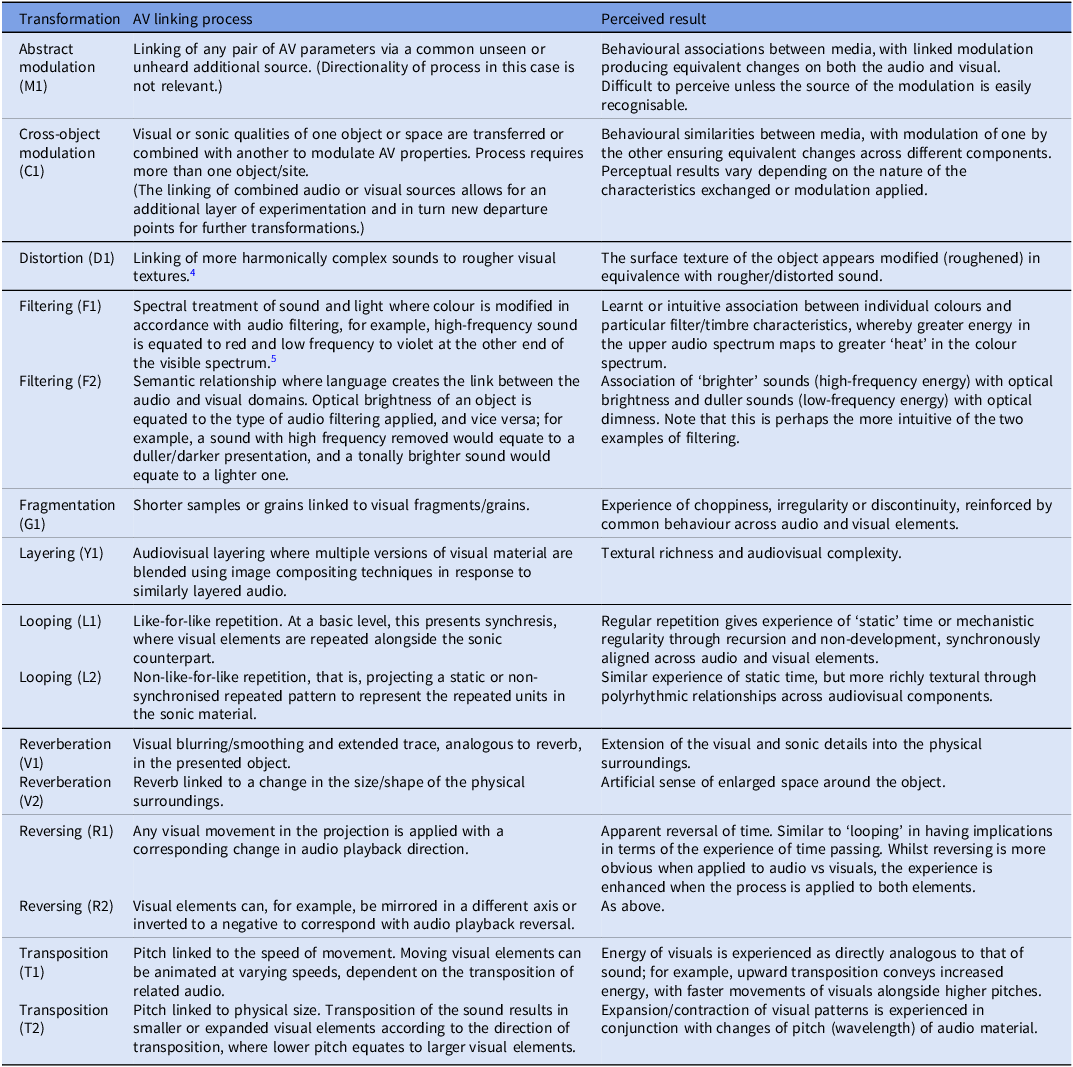

Table 1. Transformations Part 1 (process linked)

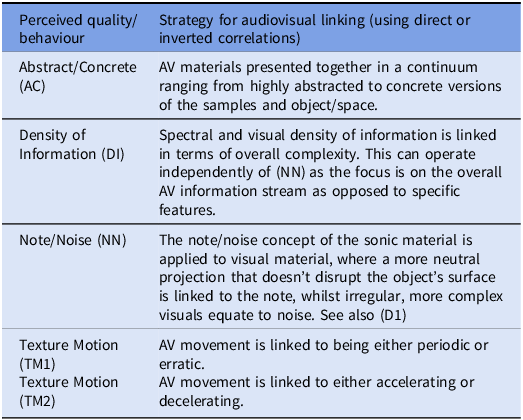

Table 2. Transformations Part 2 (concept linked)

At this juncture, it is important to highlight that, in addition to offering the broader aesthetic starting point, electroacoustic processing techniques serve as the inspiration for all the transformations presented in these tables. The next section presents a discussion of electroacoustic audiovisual approaches relevant to the creation of the table and then briefly discusses audiovisual models that apply to screen and installation-based works. From there, the proposed transformation strategies are presented, concluding with a reflection on their further use.

2. An electroacoustic audiovisual approach

At first glance, combining a traditionally acousmatic art form with visual material may appear counterintuitive, but as discussed above, both Garro and McDonnell see this as a natural progression when considering the convergence of technology. More importantly, as observed by Andrew Lewis, ‘[t]his is not just a similarity in working methodology, but a similarity in how that methodology affects one’s relationship with the material’ (Lewis Reference Lewis2014). There is no doubt, then, that the strategies presented in both parts of the table below would not have transpired without these similarities. McDonnell goes further, describing her relationship to the material where ‘[a]n extended form of listening takes place where one comes to know the sounds in a music composition with a view to creating a visual work with the music’ (Reference McDonnell and Knight-Hill2020: 253). This extends to her explaining how she applies musique concrète techniques to camera-originated visual footage (ibid.: 240), as well as comparing her approach to more abstract visuals as being aligned with elektronische Musik (ibid.: 248).

One further example of electroacoustic ideas informing audiovisual practice is of interest. Joseph Hyde, in his 2012 article, presents the idea of translating reduced listening into the audiovisual domainFootnote 2 . Hyde’s idea is that one can achieve a type of ‘visual suspension’ akin to reduced listeningFootnote 3 by presenting either visual silence or visual noise (Hyde Reference Hyde2012: 174–177). This is an interesting concept, although Hyde admits that it may be ‘an ultimately futile aim’, only available to true synaesthetes (ibid.: 177–178). Hyde’s approach is much more towards abstraction in terms of the resulting audiovisual material, which may explain why he pursues the visual suspension idea. Surprisingly, he does not extend the concept to that of an audiovisual object (in the Schaefferian mould), stating that it ‘implies a fixed audiovisual synchronic relationship’ (ibid.: 172).

Unlike Hyde, others engage with the concept and possible forms of the audiovisual object in detail. Although some of the examples mentioned above deal specifically with physical objects in audiovisual installations, the ‘audiovisual object’ is an ambiguous descriptor that can be used in a variety of ways. For example, Adam Basanta applies the term to the physical ‘luminosonic’ objects found in his own and others’ installations (Basanta Reference Basanta2013: 2). The audiovisual object discussed now is a means to theorise audiovisual material in the same way we would a sound object as defined by Schaeffer. Garro (Reference Garro2005) appears to be one of the first to use this term, and, in keeping with Schaeffer’s objet sonore, he maintains the use of French in the abstract to his paper, offering the term ‘objet audiovisuelle’. The power in Garro’s idea is his willingness to translate phenomenological characteristics from electroacoustic composition to the audiovisual domain. This offers a starting point to the techniques outlined below, even if Garro’s focus is on broader audiovisual composition techniques rather than a detailed analysis of the audiovisual object itself.

Andrew Connor takes the term further, making it central to his thesis. By his own admission, his application of the audiovisual object is limited by the creative work being ‘solely within the realms of electroacoustic composition and abstract animation’ (Connor Reference Connor2017: 224). He is, however, a strong advocate of the concept to expand the notion of the objet sonore and sees the audiovisual object as a ‘key building block’ in audiovisual composition (ibid.: 225). Recent work by Francesc Martí Pérez takes the audiovisual object to the micro-level by treating fixed audiovisual events as samples or smaller grains that are processed simultaneously (Pérez Reference Pérez2020). Finally, from an analytical perspective, Myriam Boucher and Jean Piché present a very clear definition of the audiovisual object in their chapter on video music:

An audiovisual object is formed by the fusion of a media pair in the viewer-listener’s mind. Audiovisual objects act as the smallest components of audiovisual discourse, like sound objects are the main constituents of electroacoustic music or musical chords form the backbone of harmonic progressions. (Boucher and Piché Reference Boucher, Piché and Knight-Hill2020: 16)

Crucially, the authors acknowledge that the object can apply both to ‘strongly source-bound associations’ and to situations where the sonic and visual sources are ‘non-representational’. By allowing this, their concept of the audiovisual object extends to ‘include any sound/image association that the viewer-listener instinctively accepts as perceptually bound’ (ibid.: 16).

All the above examples offer further encouragement to apply an electroacoustic mindset to the process of creating audiovisual works (and by extension, installations with audiovisual components). Without compounding the ambiguity already mentioned, I would propose that in audiovisual installations using objects, the framing of the audiovisual object can involve applying the phenomenological reduction outlined by Schaeffer in his objet sonore to the physical objects featured in the installations. This helps to reveal their inherent (and sometimes hidden) qualities in terms of sound, materiality and visual aesthetic. Once this process is undertaken, the qualities and their interplay help inform the modified audiovisual objects that build and structure the installations. In my own recent works, this process is only possible with the adoption of projection mapping, which, by adding visual layering onto the objects, helps alleviate any restrictive source bonding issues.

3. Pre-exisiting models

3.1. Screen-based

Rather than addressing broader models of audiovision in narrative film, the following discussion focuses on theory and practice combining electroacoustic music with visual media. This section first examines screen-based audiovisual approaches, followed by two models that specifically address installations.

As mentioned earlier, Garro’s paper on his own ‘perspective on electroacoustic music with video’ is particularly useful (Garro Reference Garro2005). In addition to introducing the idea of the audiovisual object and giving comparative insights into working across the auditory and visual domains, his paper acts to highlight pertinent issues discussed in subsequent audiovisual models. Whilst not offering a specific model per se, Garro identifies two significant things. First, he presents a continuum acknowledging that ‘association strategies’ between audio and visual material will range at one end from ‘interpretative clues’ relying on the ‘psychological response’ to strict parametric mapping at the other, where ‘explicit links [exist] between one or more attributes of the visuals and one or more attributes of the sounds’ (Garro, Reference Garro2005: 5). Second, Garro is quick to acknowledge that ‘parametric mapping on its own does not constitute a self-sustaining methodology to define an audio-visual language’ (ibid.: 6) and that ultimately an overreliance on this method can lead to audiovisual redundancy (ibid.: 7–8).

One could be forgiven for thinking that the deterministic nature of parametric mapping is inferior to more nuanced strategies, such as the phenomenological counterpoint described by Battey (Reference Battey2015), where the concept of species counterpoint is applied between gestures of audiovisual material. I would suggest, however, that there is a strong place for the parametric, especially to enhance synergy between the sounds and physical objects at the centre of the installations. This is based on the assumption that, as is the case in my own works, a causal link exists between the sounds we hear and the objects presented in the installation. Garro (Reference Garro2005: 5) concurs that establishing (perceptual) synergy is one of the main benefits of parametric relationships. Abbado’s work on ‘Perceptual Correspondences of Abstract Animation and Synthetic Sound’ is of note due to the simple but intuitive linking of parameters between 3D computer-generated shapes and corresponding sounds. His ‘Timbre-Shape’ correspondence is one example of this, where he ‘associate[s] low-energy spectra with smooth shapes and high energy spectra with edged shapes’ (Abbado Reference Abbado1988: 4). The reason for this interest in Abbado’s method is that it prompted me to consider audiovisual transformations that fall outside of the classic musique concrète, pre-defined studio transformations (transposition, reverse, looping, etc.) towards an approach that originates instead from the perception of audiovisual material.

The other valuable aspect of Abbado’s approach is that he presents animated computer-generated 3D objects as the visual element of his work alongside associated sonic material. It is not a great leap to imagine similar visual processes being applied to the physical objects in my own works, although there is admittedly a limit as to what can be achieved with projection mapping as the tool only applies to the surface layer of the objects. It would be difficult, for example, to extend this much further than changes of texture on the exterior of the object, although there is scope to create a limited illusory change of 3D visual space from projection mappingFootnote 6 . Panourgia, Wheelaghan and Yang (Reference Panourgia, Wheelaghan and Yang2018) present a more direct and complex parametric link between computer-generated 3D objects and synthesis in their research, which is understandably more sophisticated with the benefit of 30 years of computing progress since Abbado’s first experiments. Their investigation demonstrates links between multiple parameters of 3D shapes and those of subtractive and granular synthesis. In the same way as Abbado, their approach is intuitive, and they admit to being guided by ‘personal preference’ and ‘[o]ther interpretations [that] draw on acoustic phenomena relating to the reflective properties and behaviours of objects and spaces…’ (Panourgia et al. Reference Panourgia, Wheelaghan and Yang2018: 4). Of note is one process that changes timbre as the 3D shape morphs from cube to sphere and, in the same example, faces of the cube detach alongside a low-pass filter change giving the impression the sound is emanating from inside the cube (ibid.: 8). Although these ideas are not directly incorporated into the list of transformation strategies below, they offer potential exploration in future research and creative work.

3.2. Installation specific

Discussion in the literature of audiovisual models aimed towards installations appears to be limited. Two that do exist come from Basanta (Reference Basanta2013) and Blow (Reference Blow2014). Basanta’s model is a fusion of ideas building on Chion’s (Reference Chion1994) synchresis and the ‘media pairing’ concept from Coulter (Coulter Reference Coulter2010). By combining those ideas and adding his own strength of the ‘perceptual bond’ dimension, Basanta presents eight typologies mapped onto a 3D graph.

Basanta’s inclusion of the strength of perceptual bond is justified by addressing what he sees as shortcomings in Chion’s and Coulter’s models, which he ultimately decides are ‘inadequate tools for compositional design of audiovisual works…’ due to their ‘lack of perceptual correlation’ (Basanta Reference Basanta2013: 33). This is possibly unfair, as by his own admission both base their theories around screen-based audiovisual media which have ‘near-infinite possibilities of sound-image combinations’ (ibid.: 32). Basanta, on the other hand, can afford to be more controlled and specific in his model as the luminosonic works that he studies are, by their nature, more restricted in the visual domain. He does not, for example, need to concern himself with abstract visuals as Coulter does; the luminosonic objects in question are fixed apart from their ability to emit varying amounts of light. Basanta also acknowledges that his model ‘offers various complications’ relating to analysis of screen-based media, especially when dealing with the complexity arising from less abstract visual content (ibid.: 55–56). Basanta’s model is justified given the context and is relatively transferable from the luminosonic works that he creates and cites to projection-mapped installations, which are the target for the strategies outlined below. Finally, in what could be viewed as additional flexibility, Basanta himself notes that ‘(i)n reality, the boundary lines between any given typology are blurry, depending in part on the individual perceiver and the preceding compositional context’ (Basanta Reference Basanta2013: 35). He would seem then to concede, as Coulter does, that the subjective experience (to use Coulter’s terminology) of the ‘listeners/viewers’ will influence the variability of the model (Coulter Reference Coulter2010: 28).

Mike Blow confronts the matter of subjective interpretation in his thesis in a different way. Rather than seeing this subjectivity as a problem, it becomes a key feature in his ‘Multisensory continuum and categories’ (Blow Reference Blow2014: 81). In fact, he appears to regard an increase in subjectivity on the part of the viewer as an opportunity for them to actively promote the creation of new meaning in his works. In practice, Blow suggests that as the ‘coherence between the sound and object’ decreases, the scope for interpretation, imagination and co-creation increases (ibid.: 81, 98–99).

Causally linking sound and object is fundamental to my own practice, and this practice helped define the transformation strategies. As expected, most of my own recent works would (conceptually) sit in Category 1 of Blow’s chart – ‘Sound and object are causally linked’, although others do stray into the ‘Direct Semantic Relationship’ of Category 2 (ibid.: 81). His second category ‘break[s] away from the physical causality’ of the first and ‘enables more esoteric sound/object relations to be explored’ via association or ‘imaginable processes that have happened in the object’s past…’ (ibid.: 85–86). Blow’s approach raises questions about my own, one implication being that meaning in works can only be established as the semantic gap between sound and object widens. Although the starting points may be in the first two categories, the processing that can occur via the audiovisual transformation strategies helps works oscillate across the semantic gap into Categories 3 and 4 – ‘Indirect Semantic Relationship’ and ‘Process Relationship’, respectively.

4. Audiovisual transformation strategies

This section introduces the two subsections of transformation strategies in their entirety, followed by a more detailed presentation of each of the entries. Part 1 originated from reflection on my own practice and began as an attempt to formally record some of the intuitive composition strategies that combined sonic and visual material using specific electroacoustic processing techniques. Part 2 was a response away from this specific approach towards a broader conceptual method of audiovisual linking. The term ‘transformation’ was deliberately chosen because it describes the modification of a process to link with an audio or visual equivalent, but more fundamentally, the transformations are employed during the composition process to transform sonic and visual material, together over time. The transformation tables, then, act primarily as a tool to aid audiovisual composition choices. They are not intended to be the only method of creating audiovisual correspondence in works; they are one formal strategy that resonates with an electroacoustic, practice-based methodology.

As previously discussed, the initial motivation to create the strategies was purely to assist with audiovisual composition choices and, more specifically, to integrate visual material using projection mapping. The strategies feed into an overall aesthetic approach to create the installations by reinforcing both the perceptual and metaphoric associations between objects/site and related source sounds. The strategies could also be adapted as a speculative analytical tool to examine pre-existing works, especially as the second part of the table contains the influence of spectromorphology – itself an approach originally designed to describe and analyse the listening experience (Smalley Reference Smalley1997: 107).

All the transformations were conceived within the context of visual projection mapping onto static objects. Arguably, similar processes could also be used in screen-based works, especially those that present objects as on-screen source material. Further experiments could be conducted that evaluate the effectiveness of the physical presence of an object vs. a screen-based representation, but this is outside the scope of this article.

Codes using one or two letters and/or a number are used to indicate each of the transformations to provide a shorthand for discussion later in the article and beyond. The table headings ‘perceived result’ and ‘perceived quality’ in the two respective parts are intended to describe the experience of the audience (or at least my estimation of their experience). In reality, this degree of perception will vary depending on the transformation type, individual perceiver and how the materials are managed within the framework of each transformation. Finally, although the audiovisual link was almost exclusively inspired by an audio process as the starting point, there is an expectation that when used in the compositional process, either sonic or visual material could be the starting point. Put another way, each of the transformations in both parts of the table can be bidirectionally applied.

4.1. Part 1 discussion

Part 1 of the table, although prompted by a granular synthesis process in an earlier work, was devised initially by imagining what Schaeffer’s transformation of sound objects by means of ‘filtration, editing, looping, reverberation, and changes in speed and direction’ (Kane Reference Kane2014: 33) would look like when applied to physical objects. Crucially, there is a strong process-driven basis to the transformations, which by design are biased towards stricter parametric mappings. Each category is now presented individually with further details and examples as required:

4.1.1 Abstract modulation (M1)

Abstract modulation easily has the potential to be the most opaque of the transformations. It uses a modulation source that can be applied to any transformation rather than being based on a specific studio process like most other items in Part 1 of the table. It offers the chance to construct an audiovisual pairing without the resulting effect being constrained. Its strongest feature is that it allows a hidden or more obscure audio or video source to act as the modulator of the transformation. Ideally, this would be something from within the same work that acts as a metaphorical resonance as it becomes embodied within a new audiovisual object. Abstract modulation is more likely to function only as a compositional tool to help control and link audiovisual material. It offers a vast amount of flexibility; however, it is less likely to be perceived as obviously linking sources from an audience perspective, although with a source of modulation, which produces an obvious resultFootnote 7 , recognition of a link may still be possible.

4.1.2. Cross-object modulation (C1)

Cross-object modulation is the most specialised of the transformations because it requires more than one object (or site) to be involved in the work to function. It is also, like abstract modulation, very flexible as it does not prescribe any specific processes. In my own recent work, it was used to hybridise visual elements from two objects to generate material, as well as to use samples from one of the objects as a control source for audiovisual material linked to the other. A successful strategy was to use samples with more rhythmic texture as sidechain inputs for noise gates and software instrument controls. Admittedly, it could be viewed as being like abstract modulation. However, it is not intended to obscure the source of the modulation and, crucially, it requires material from another object or site to be imposed onto another.

4.1.3. Distortion (D1)

This is similar to the two filtering transformations (F1 and F2) featured next in the table and links to practice explored by Abbado (Reference Abbado1988) in terms of timbre and visual texture.

4.1.4. Filtering (F1) and (F2)

Two transformations are proposed involving filtering. F1 takes the visible light spectrum and maps it so that sounds with strong high-frequency components show as red in colour, whilst at the other end of the spectrum, sounds with more low-frequency energy display as violet. This choice felt intuitive, especially as we are accustomed to seeing heat maps that present higher values as red. As such, I use this mapping consistently in my works, though it is the reverse of the physics involved, where higher frequency light in the electromagnetic spectrum is towards the violet end of the range; however, such a disparity is not uncommon as despite many experiments mapping sound to light ‘over history’ there is still no agreed practice (Daniels & Naumann Reference Daniels and Naumann2010: 6).

F2 is less prescriptive. Rather than mapping colours like F1, it uses a more semantic approach, where intensity of the light (and possibly colour saturation) is mapped against subjectively ‘brighter’ and ‘darker’ sounds. This is similar to Abbado’s more intuitive approach to texture and colour (Reference Abbado1988: 4).

4.1.5. Fragmentation (G1)

The fragmentation transformation was the catalyst for the transformation strategies. The audio is processed using granular synthesis, and in my own works, the corresponding visual processes are more representative than a precise analogous process, such as fracturing a computer-generated 3D model or using a more granular visual texture via the material projected. This transformation is arguably less transparent in terms of the audio process compared with most listed already, which could increase the semantic gap (Blow Reference Blow2014: 81) between sound and object.

4.1.6. Layering (Y1)

This is a simple process that provides a visual analogy to audio layering (mixing) through image compositing. Variations using this technique are described by Garro (Garro Reference Garro2005: 14–15).

4.1.7. Looping (L1) and (L2)

L1 is a simple pairing that results in synchresis. The effectiveness of this is supported by Blow (Blow Reference Blow2014: 28) who states that for sound and object ‘[to] be fully integrated similar amounts of movement should be perceived in both media’.

L2 is a less formal way of representing the duplication of looped audio material. Contrary to L1, synchresis is not involved, but instead, repeating patterns in the visual material act as a metaphor for the audio.

4.1.8. Reverberation (V1) and (V2)

V1 is a simple visual analogy to reverb. V2 is intended to use 3D lighting effects where the projection mapping renders a virtual light source to give the impression of artificial, elongated shadows around the physical object.

4.1.9. Reversing (R1) and (R2)

Only the first of the reverse transformations has been utilised in my own works up to this point, and it was combined with other visual textures so as not to be too overt. There was some reluctance in the end to adopt this transformation, probably given that reverse can be one of the more clichéd and obvious of audio processes (Emmerson Reference Emmerson2000: 67). This transformation also highlights a mismatch between perception of the audio and visual elements, given that sound is more obviously exposed when reversed compared to the more abstract video elements. As Chion describes, ‘aural phenomena are much more characteristically vectorised in time, with an irreversible beginning, middle, and end, than are visual phenomena’ (Chion Reference Chion1994: 19).

4.1.10. Transposition (T1) and (T2)

Related to the previously described loop-based transformation, T1 makes the connection between pitch and playback speed and translates these dynamic changes to the animated visual elements. T2, in a recent work, uses the scale of the noise pattern to represent a changing size of the visual elements to correspond with pitch.

4.2. Part 2 discussion

The second part of the table seeks to expand on the first by offering a more holistic way of linking audio and visual material. The issue, as noted above by Garro, is that an overreliance on direct parametric mapping can lead to ‘audiovisual redundancy’ (Garro Reference Garro2005: 7–8). By making associations on a conceptual level, the aim is to allow more flexibility in the compositional approach without being tied to a specific technical process. The conceptual transformations, then, are also felt to be more appropriate for medium to longer-term durations of material, as their progress can be managed in a variety of ways and therefore sustain interest for longer than a more obvious parametric process. Another advantage is the option to use inverse mappings between the audio and visual features. This helps to manage the resulting complexity of the audiovisual stream. The overall concept of using inverse relationships is highlighted by Battey and Fischman when speaking of the ability to shape discourse and overall structure (Battey & Fischman Reference Battey, Fischman and Kaduri2016: 13).

The starting point was, like Part 1, an electroacoustic-inspired approach to formulate the transformations. However, where Part 1 utilises specific audio transformations, the second part draws from analytical concepts, mainly inspired by Denis Smalley’s spectromorphology (Reference Smalley1997). These ideas seemed appropriate given their acceptance of visual descriptions to support the analytical concepts. Additionally, Smalley’s focus on perception rather than a specific process helps align with the second part of the table. Whilst Smalley is keen to highlight that his ideas are not created to be compositional tools, he admits that ‘…once the composer becomes conscious of concepts and words to diagnose and describe, then compositional thinking can be influenced…’ (ibid.: 107). The ‘concepts’ in this case then have been selected for their ability to translate to visual material – a feature also central to Manuella Blackburn’s ‘Visual Sound-Shapes’, which draws on the accessibility of spectromorphology’s vocabulary pool (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2011: 5). As in Part 1, there is no expectation that the transformation needs to be led by, or begin with sonic material, even if again, the inspiration for each item is from an electroacoustic foundation.

4.2.1. Abstract/concrete (AC)

The first transformation, ‘Abstract/Concrete’, is the most generalised of the four. Rather than seeking to become enmeshed with the dualism explored by Schaeffer with these terms (Chion Reference Chion2020), it functions simply to vary the presentation of sounds and visual material presented in their original (concrete) guise, compared to abstract versions heavily effected by processing. In this way, the transformation is aligned with Emmerson’s description of aural and mimetic discourse from his language grid (Emmerson Reference Emmerson1986: 17–19).

4.2.2 Density of information (DI)

This and the remaining transformations all borrow from Smalley’s spectromorphology (Reference Smalley1997). Density of Information is inspired by ‘Spectral space and density’ (ibid.: 121) and reinforced by the ideas of Battey and Fischman when used in an inverse correlation so as not to ‘purposefully stun the viewer…’ (Reference Battey, Fischman and Kaduri2016: 13). To be clear, this is an arrangement-related matter (to use a musical analogy), as opposed to concerning absolute spectral content of the sounds, and is more likely to combine multiple audiovisual streams at the complex end of the continuum. Smalley describes the continuum in audio terms as being like a ‘fog, curtain or wall…’ (Smalley Reference Smalley1997: 121). Visually, those descriptions could be translated literally in terms of the ability to blend and composite visual material, or a more spatial approach could be taken where individual details inhabit different parts of the projected surface or overlap.

4.2.3. Note/noise (NN)

The note/noise transformation is useful as it offers another way to control more abstract (or artificial) material that sometimes arises intuitively in the works. It could be viewed as a subcategory of abstract/concrete but is useful in works where the raw source sound of the object may vary naturally anyway in terms of ‘note to noise continuum’ (Smalley Reference Smalley and Emmerson1986: 65–68). In this context, sound sources that vary from either end of the note/noise continuum can be arranged over time with little or no processing in order to map against corresponding visual material.

4.2.4. Texture motion (TM1) and (TM2)

In the spectromorphological sense, texture plays an important role in many works, so assigning a method of managing this as an audiovisual relationship and in higher-level structuring seems important. The two variations listed above are borrowed from ‘Texture motion’ as described by Smalley (Reference Smalley1997: 118). The management of simultaneous audio and visual textures is of course possible with many of the transformations listed in Part 1 of the table. The difference in this case is that the transformation has the flexibility to be decoupled from any specific audio process.

5. Reflections on the transformations

The transformations listed above have helped create material in my own works that would have been unlikely to transpire if left to intuition alone. Also, despite being conceived specifically for installations, there are no transformations that could not be easily adapted to other audiovisual works, especially those presented on screen, which, by their nature, can depict all of the physical objects found in the installations. I would, however, speculate that the cross-object modulation transformation (C1) is more effective in an installation setting, given the multiple perspectives of the viewer combined with the physical reality of the objects in the space. I believe that in this context, it is more likely a viewer would make the connection between the grille of the subwoofer and the same patterning appearing projected onto the gong as occurs in Paiste 36 than if this were presented on video alone.

A potential limitation is that, unlike Basanta’s eight typologies, none of the transformations in the table imply a strength of perceptual bond between object and sound as perceived by the audience. Basanta’s rationale for focusing on this is to allow more comprehensive control over the compositional process, although, as discussed above, Basanta himself has some doubts regarding the subjective interpretation involved and how this affects the typologies (Basanta Reference Basanta2013: 35). The initial sense for the table was that all transformations would help reinforce the link between object and the sounds. In reality, the context of how the transformations are applied means there will be varying degrees of recognition of this link at any one time. Also, because of their ever-present physical, causal nature, there is perhaps by default a higher level of perceptual bond than in more abstract, screen-based works. Reflecting on Blow’s concept of the semantic gap (Blow Reference Blow2014: 81), it is likely that some of the transformations are perceived as being more causally linked than others. For example, the fragmentation process (F1) is less obvious compared with the basic loop (L1): here, the synchresis is inescapable, and the causal link between object and sound is clearly implied.

Finally, as discussed above, the transferability of the table to audiovisual practice beyond installations suggested in this article makes it available to other practitioners and researchers to use, repurpose and build on to meet their own requirements. Repurposing could find others reinterpreting what a particular audio process might ‘look like’. Transposition, for example, is presented above as being linked to physical size, as that seemed most intuitive to me. Another way of linking transposition could be based on changes to the overall audio spectrum, where the result would be a corresponding shift in the colour of the visual material. In addition to being a useful tool for practitioners with similar backgrounds to myself, the table’s effectiveness for shaping and inspiring audiovisual composition choices could extend to those with a visual art background who use video or images as a point of departure and who wish to generate corresponding audio material. Linked to this, the cross-disciplinary nature of the table makes it a resource for collaborative projects involving separate sound and visual artists. Finally, as all the transformations in the table operate independently and could be simplified by removing some of the more complex entries (e.g., Cross-object modulation, Abstract/Concrete), they could easily be adapted for use at undergraduate, college or school level.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771825101052.