Introduction

Social prescribing is a person-centred approach involving referral to non-clinical services including those within the third sector (Public Health England, 2019), which describes groups or organisations operating independently to government, where social justice is the primary goal (Salamon & Sokolowski, Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2016). It is an intervention that directs patients with non-medical health needs away from healthcare and towards social means of addressing their needs (Muhl et al., Reference Muhl, Mulligan, Bayoumi, Ashcroft and Godfrey2022), such as support with the social determinants of health including finance and housing, activities around art and creativity, and exercise (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Camic and Chatterjee2015). Social prescribing can also involve referring clients to engage in volunteering (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Camic and Chatterjee2015; Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Mahtani, Wong, Todd, Roberts, Akinyemi, Howes and Turk2022), defined as unpaid work or activity to benefit others outside of the family or household, in which the individual freely chooses to participate (Salamon & Sokolowski, Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2016). Volunteering, also known as community service in the USA, can be regular and sustained or ad hoc and short term (episodic) (Macduff, Reference Macduff2005) and encompasses activity directed towards helping others (civic) (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013), environmental conservation (environmental) (Husk et al., Reference Husk, Lovell, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2016), and as part of education (service learning), often accompanied by structured reflection of the voluntary activity (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009).

Unique to other referrals within social prescribing, volunteering may provide a twofold benefit. Volunteering provides clear economic benefits to organisations (NCVO, 2021a) and acts as a ‘bridge’ of welfare services to deprived communities (South et al., Reference South, Branney and Kinsella2011). There are also distinct benefits for recipients in comparison with professional help including increased sense of participation, self-esteem and self-efficacy, and reduced loneliness, due to a more neutral and reciprocal relationship (Grönlund & Falk, Reference Grönlund and Falk2019). As utilised by social prescribing, volunteering as an intervention in itself is supported by clear health benefits to the volunteer, particularly improved mental health and reduced mortality (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013). There are many primary studies which find significant positive effects of volunteering on social, physical and mental health, including mortality and health behaviours (Casiday et al., Reference Casiday, Kinsman, Fisher and Bambra2008; Linning & Volunteering, Reference Linning and Jackson2018). Furthermore, there is evidence that these benefits occur from adolescence across the lifespan (Mateiu-Vescan et al., Reference Mateiu-Vescan, Ionescu and Opre2021; Piliavin, 2010), although they may increase with age (Piliavin, 2010). However, due to the poor quality of this evidence, it is unclear which of the benefits, particularly concerning mental health, predict rather than result from volunteering (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Kamerāde, Connolly, Ellis, Nichols and Grotz2020; Thoits & Hewitt, Reference Thoits and Hewitt2001).

An investigation of the benefits of volunteering can therefore inform on the utility of this practice in improving the health and well-being of clients (Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Mahtani, Wong, Todd, Roberts, Akinyemi, Howes and Turk2022) and support a twofold benefit (Mateiu-Vescan et al., Reference Mateiu-Vescan, Ionescu and Opre2021). Also, establishing the benefits may help retain volunteers within organisations (Mateiu-Vescan et al., Reference Mateiu-Vescan, Ionescu and Opre2021), as low volunteer retention (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Zhang, Xing, Guan, Cheng and Li2020) has been a key debated issue (Snyder & Omoto, Reference Snyder and Omoto2008; Studer & Schnurbein Reference Studer and Von Schnurbein2023), with suggested solutions including maintaining motivation through opportunities for evaluation and self-development (Snyder & Omoto, Reference Snyder and Omoto2008), improved management of volunteers (Studer & Schnurbein Reference Studer and Von Schnurbein2023), and recognising their value (Studer & Schnurbein Reference Studer and Von Schnurbein2023). However, outcomes of volunteering such as self-efficacy (Harp et al., Reference Harp, Scherer and Allen2017) and sense of connection (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Ng, Hyde, Legg, Zajdlewicz, Stein, Savage, Scuffham and Chambers2021) have also been shown to predict retention.

An umbrella review methodology is appropriate to provide a systematic and comprehensive overview of the vast evidence on the benefits of volunteering and to determine which are most supported, making clear and accessible recommendations for research and policy (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Fernandes, Becker, Pieper and Hartling2020). An umbrella review can also help establish what works, where, and for whom, through comparison of different settings, volunteering roles, and populations from systematic reviews with different focuses (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Devane, Begley and Clarke2011). Thus, it is important that an exploration of the benefits of volunteering consider potential moderators. Umbrella reviews also assess the quality of the included systematic reviews and weight findings accordingly (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Devane, Begley and Clarke2011), which may help to establish a causal influence of volunteering. The emerging use of an umbrella review methodology in third sector research has enabled clear recommendations for practice, exploration of moderators and mediators, identification of gaps in the research, and recommendations for future reviews (Saeri et al., Reference Saeri, Slattery, Lee, Houlden, Farr, Gelber, Stone, Huuskes, Timmons, Windle and Spajic2022; Woldie et al., Reference Woldie, Feyissa, Admasu, Hassen, Mitchell, Mayhew, McKee and Balabanova2018).

Aims

The aims of this umbrella review were to;

1) Assess the effects of volunteering on the social, mental and physical health and well-being of volunteers, and;

2) Investigate the interactions between outcomes and other factors as moderators or mediators of any identified effects.

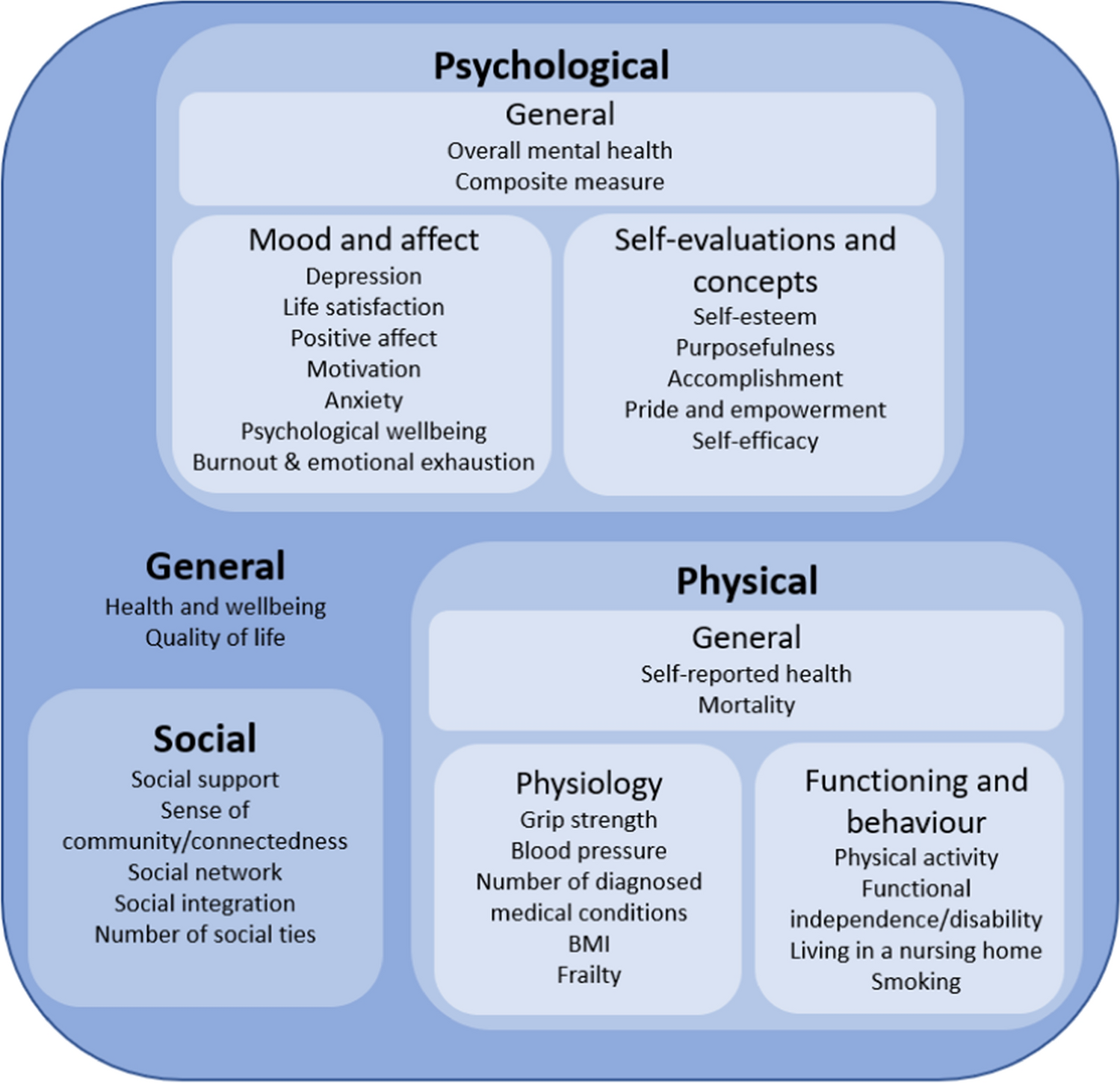

Establishing clear conclusions to these aims helped identify gaps in the literature to direct future research and provided directions to support research and implementation of interventions involving volunteers. Specific outcomes explored within this review are displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Outcomes identified and analysed within the current umbrella review, grouped by coding of outcome

Methods

This umbrella review was pre-registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Nichol et al., Reference Nichol, Wilson, Rodrigues and Haighton2022) following scoping searches but prior to the formal research (registration number: CRD42022349703). Reporting of the umbrella review methodology followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan and Chou2020). Prior to formulating the research question, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Systematic Review Register, and the Open Science Framework Registry were checked for pre-registrations of umbrella reviews of the same or a similar topic. No such umbrella review protocols were retrieved.

Inclusion Criteria

Intervention: Volunteering

Volunteering was defined as conducting work or activity without payment, for those outside of the family or household. Participants of all ages were included. There were no limits by country or organisation or group that the volunteering was for. Although part of the definition of volunteering is that it is sustained (Salamon & Sokolowski, Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2016), all durations of volunteering were included in this review to ensure a comprehensive search. Additionally, only reviews of volunteering involving some interpersonal contact with other volunteers or recipients were included. Reviews of volunteering in disaster settings such as warzones and aid for natural disasters were excluded, as these represent volunteering in extreme circumstances that is unusual and highly stressful (Thormar et al., Reference Thormar, Gersons, Juen, Marschang, Djakababa and Olff2010).

Systematic reviews were required to investigate the effect of volunteering on the volunteer. Reviews were excluded if volunteering was a component of a wider intervention. Reviews only assessing the effect of volunteering on the recipient were also excluded. The distinction between volunteer and recipient was sometimes less clear for reviews assessing the effect of intergenerational programmes. In this case, outcomes were only extracted for the group(s) that were performing work or activity, and no data was extracted from primary studies where neither group were.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest was health and well-being. This was categorised into general, psychological, physical, and social. Of additional interest was the interaction between these effects and with other factors such as demographics or factors associated with volunteering such as duration and type. Outcomes could be self-reported, or objective for physical outcomes (e.g. body mass index (BMI)). Reviews that did not assess effect were excluded, such as those exploring implementation, feasibility, or acceptability of volunteering as an intervention.

Types of Studies

The focus of this umbrella review was on systematic reviews of quantitative studies with or without meta-analyses to assess effect, although reviews of mostly quantitative studies were also included. The adopted definition of a systematic review was a documented systematic search of more than one academic database. Primary studies, reviews of qualitative or mostly qualitative literature, opinion pieces and commentaries were excluded.

Search Strategy

The search was conducted on the 28th July 2022 via 11 databases including EPISTEMONIKOS, Cochrane Database, and PsychARTICLES, ASSIA and the Health Research Premium collection via ProQuest (Consumer Health Database, Health & Medical Collection, Healthcare Administration Database, MEDLINE®, Nursing & Allied Health Database, Psychology Database and Public Health Database). The search was applied to title and abstract and restricted to peer-reviewed systematic reviews published in English, as all reviewers were English language speakers with no translation services available. Initial scoping searches helped to build the search strategy (Supplementary Material 1). To maximise scope, forward and backward citation searching was applied, and the results of scoping searches and further sources such as colleagues and other academics were combined into the final umbrella review.

Study Selection

Search results were exported via a RIS file and uploaded onto Rayyan for screening. Reviewer BN screened all reviews by title and abstract against the inclusion criteria, before screening the remaining (not previously excluded) articles based on full text. Details on independent screening and inter-rater reliability are available in Supplementary material 2.

Quality Appraisal

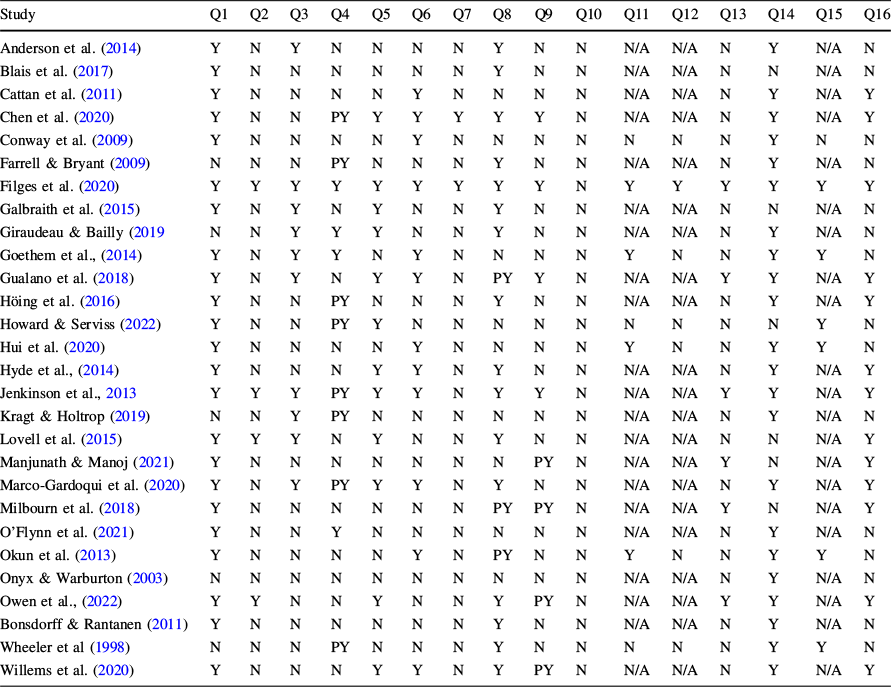

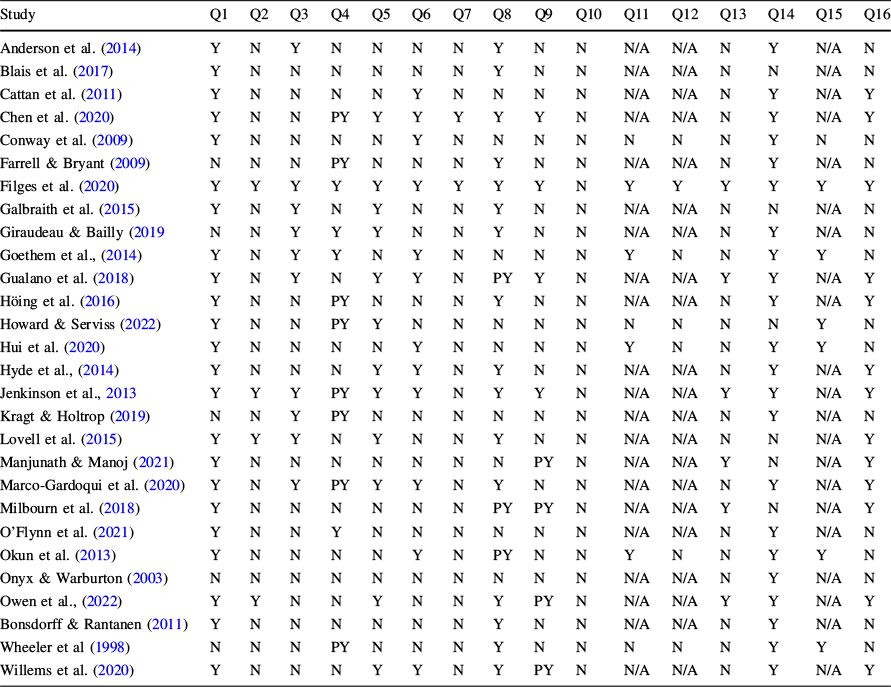

Quality was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 checklist (Shea et al., Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel, Moran, Moher, Tugwell, Welch, Kristjansson and Henry2021), which is designed to assess the quality of quantitative systematic reviews of healthcare interventions (Shea et al., Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel, Moran, Moher, Tugwell, Welch, Kristjansson and Henry2021) and has the highest validity in comparison to other quality assessment tools (Gianfredi et al., Reference Gianfredi, Nucci, Amerio, Signorelli, Odone and Dinu2022). Also, the accompanying guidance sheet ensures consistent use across reviewers. The 16 checklist items are presented under Table 1. Further details on quality appraisal for both the included reviews and primary included studies are available in Supplementary Material 3.

Table 1 Quality of the included reviews, as rated using the AMSTAR 2

Study |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 |

Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

Q14 |

Q15 |

Q16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014) |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Blais et al. (Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

N |

N/A |

N |

Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chen, Zhang, Xing, Guan, Cheng and Li2020) |

Y |

N |

N |

PY |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Conway et al. (Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Farrell & Bryant (Reference Farrell and Bryant2009) |

N |

N |

N |

PY |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Filges et al. (Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Galbraith et al. (Reference Galbraith, Larkin, Moorhouse and Oomen2015) |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

N |

N/A |

N |

Giraudeau & Bailly (Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019 |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014) |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Gualano et al. (Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018) |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

PY |

Y |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

Y |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Höing et al. (Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016) |

Y |

N |

N |

PY |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Howard & Serviss (Reference Howard and Serviss2022) |

Y |

N |

N |

PY |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Hui et al. (Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Hyde et al., (Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013 |

Y |

Y |

Y |

PY |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

Y |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Kragt & Holtrop (Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019) |

N |

N |

Y |

PY |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

N |

N/A |

Y |

Manjunath & Manoj (Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

PY |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

Y |

N |

N/A |

Y |

Marco-Gardoqui et al. (Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020) |

Y |

N |

Y |

PY |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Milbourn et al. (Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

PY |

PY |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

Y |

N |

N/A |

Y |

O’Flynn et al. (Reference O’Flynn, Barrett and Murphy2021) |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Okun et al. (Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

PY |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Onyx & Warburton (Reference Onyx and Warburton2003) |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Owen et al., (Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

PY |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

Y |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Bonsdorff & Rantanen (Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

N |

Wheeler et al (Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998) |

N |

N |

N |

PY |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Willems et al. (Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020) |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

PY |

N |

N/A |

N/A |

N |

Y |

N/A |

Y |

Q1: Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO?

Q2: Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocolreview?

Q4: Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy

Q5: Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate?

Q6: Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate?

Q7: Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions?

Q8: Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail?

Q9: Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias in individual studies that were included in the review?

Q10: Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review?

Q11: If meta-analysis was performed did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results?

Q12: If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis?

Q13: Did the review authors account for RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review?

Q14: Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review?

Q15: f they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review?

Q16: Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review?

Data extraction and Synthesis

The data extraction form was created with guidance from Cochrane (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Fernandes, Becker, Pieper and Hartling2020). To increase transparency, data extraction was completed via SRDR plus, and made publicly available (https://srdrplus.ahrq.gov//projects/3274). Further information on data extraction, including on inter-rater agreement, is available in Supplementary Material 4.

Data Analysis

The strategy of summarising rather than re-analysing the data of the reviews was adopted (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Fernandes, Becker, Pieper and Hartling2020). Vote counting by direction of effect was applied (McKenzie & Brennan, Reference McKenzie, Brennan, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019), relying on the reporting of included systematic reviews. Variables were formed to allow for votes to be counted across reviews (e.g. self-esteem, self-efficacy and pride and empowerment were collapsed due to them regularly being combined by reviews). To test for significance, a two-tailed binomial test was applied with the null assumption that positive effects were of a 50% proportion (McKenzie & Brennan, Reference McKenzie, Brennan, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019). Given that vote counting does not indicate magnitude of effect, results of meta-analyses are also presented. To estimate the degree of overlap of primary studies between the included reviews, the equation for calculated covered area (CCA) (Pieper et al., Reference Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer and Eikermann2014) was applied. To prevent underestimating overlap, only primary studies addressing the effect of volunteering on the health of the volunteer were included when calculating overlap. Although vote counting also accounts for overlap, the resulting CCA was used as an additional tool for assessing the credibility of conclusions made.

Results

Search Outcomes

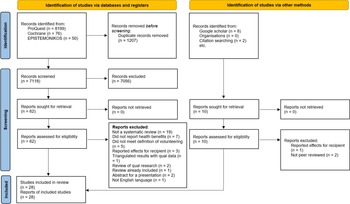

Initially 8325 articles were retrieved, as shown in Fig. 2. After removal of duplicates, 7118 remained for screening based on title and abstract and 62 articles remained to screen based on full texts, of which 21 reviews were included in the final review. A further 10 articles were retrieved from google scholar and citation searching, of which 7 were included, providing a total of 28 reviews. Excluded articles and the reasons for exclusion are available in Supplementary Material 5. Details on the inter-rater agreement of article screening can be found in Supplementary Material 6.

Fig. 2 PRISMA flow diagram of retrieved articles (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan and Chou2020)

Overlap

Authors of three included reviews were contacted to gain sufficient information to accurately calculate overlap, for example to separate studies of volunteering from those on prosociality in general (Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014); Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020). For one review (Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014)), sufficient information to calculate true overlap was not obtained and thus it was excluded from the calculation of CCA. The excluded review was the only one that focused on adolescents; thus the exclusion is more likely to result in a conservative estimate of overlap rather than an underestimation. Despite this, CCA was 1.3%, indicating slight overlap. The overlap table used to calculate CCA is available from the corresponding author on request.

Methodological Quality of Included Primary Studies

Only 12 of the included reviews assessed primary studies for quality or risk of bias (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015; Manjunath & Manoj, Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021; Marco-Gardoqui et al., Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020; Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022; Willems et al., Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020). The tools most commonly used to assess study quality were the Effective Public Health Practice Project tool (Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) and JBI checklists (Manjunath & Manoj, Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021; Marco-Gardoqui et al., Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020). Those that assessed risk of bias mainly utilised Cochrane tools ROB-2 for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013), and ROBINS-I for non-RCTs (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018). Only two reviews removed studies from the narrative review (Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018) or meta-analysis (Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020) based on quality. Reported study quality varied, but most often was reported as mainly poor quality or high risk of bias.

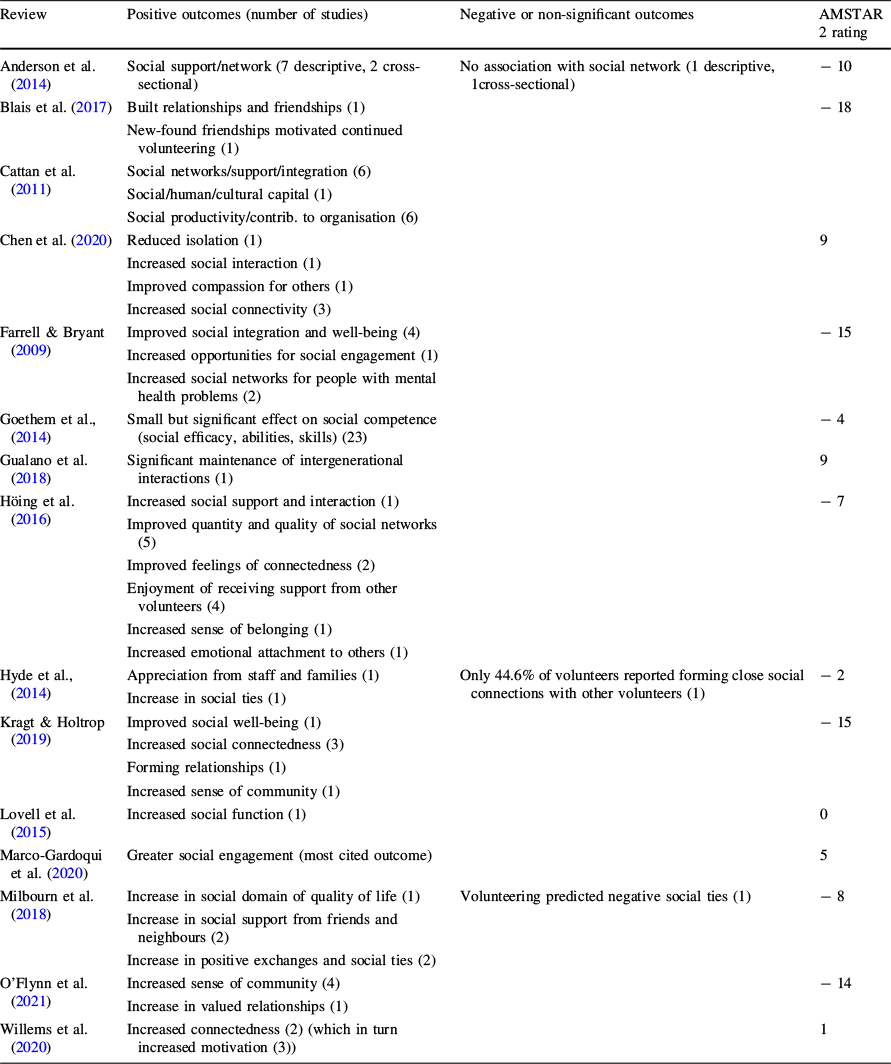

Methodological Quality of Included Reviews

As shown in Table 1, the quality of included reviews varied hugely. Only seven reviews scored more than 50% (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013; Marco-Gardoqui et al., Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022; Willems et al., Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020). One review was found to be significantly higher quality than the rest (Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020). None of the included reviews reported the funding source of the included studies, and most did not report a pre-registration or protocol, or reference to excluded studies.

Characteristics of Included Reviews

The main characteristics of included reviews are displayed in Table 2. Publication of reviews spanned from 1998 (Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998) to 2022 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022), with search dates up to 2020 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022). Most reviews focused on older people (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Bonsdorff & Rantanen Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Manjunath & Manoj, Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021; Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018; Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013; Onyx & Warburton, Reference Onyx and Warburton2003; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022; Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998), with inclusion criteria ranging from aged over 50 years (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Manjunath & Manoj, Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021; Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018) to a sample with a mean age of 80 years or above (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022). Only one review focused specifically on adolescents (Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014)). The number of included primary studies included in the reviews ranged from 5 (Blais et al., Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017) to 152 (Kragt & Holtrop, Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019), although not all related to the benefits of volunteering. For those that reported on location of included samples, most reviews included participants mostly from the USA (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Blais et al., Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017; Bonsdorff & Rantanen Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Giraudeau & Bailly, Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013; Marco-Gardoqui et al., Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020; Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018; Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013; Onyx & Warburton, Reference Onyx and Warburton2003; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022; Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998), followed by North America (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Blais et al., Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013), the UK (Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015), and Australia (Kragt & Holtrop, Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019; Onyx & Warburton, Reference Onyx and Warburton2003). Four reviews focused on intergenerational programmes (Blais et al., Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017; Galbraith et al., Reference Galbraith, Larkin, Moorhouse and Oomen2015; Giraudeau & Bailly, Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018), two on service learning (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009; Marco-Gardoqui et al., Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020), and five on specific roles including crisis line (Willems et al., Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020), environmental conservation (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Huang and Loh2022; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015), care home work (Blais et al., Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017), and water sports inclusion (O’Flynn et al., Reference O’Flynn, Barrett and Murphy2021). One review limited the search to volunteering at a frequency less than seasonally (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014).

Table 2 Characteristics of included reviews

Review |

Scope of the review |

Search dates |

Number of included studies |

Population |

Exclusion criteria for participants |

Criteria for volunteering |

Coding of outcomes assessed |

Meta-analysis |

AMSTAR 2 rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014) |

The benefits of volunteering for older adults and build a theoretical model of how volunteering reduces risk of developing dementia |

Inception up to April 2014 |

73 |

Mostly based in the USA and Canada, aged between 41 and 93 |

Older adults aged 50 or over |

Formal volunteering |

Psychological Physical Social General |

No |

− 10 |

Blais et al. (Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017) |

The benefits of intergenerational volunteering by students and residents of long-term care homes |

Not provided |

5 |

Based in the USA and Canada, mostly university students |

High school or postsecondary volunteers, working with older adults residing in long-term care homes |

Volunteering inside the long-term care homes and involved direct contact with the residents. Excluded service learning |

Social |

No |

− 18 |

Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011) |

The impact of volunteering on older volunteers’ quality of life |

Between 2005 and 2011 |

21 |

Mainly based in the USA and included participants from either the age of 55 or 65 years |

Older adults aged 50 years or over |

Formal volunteering |

Psychological Physical General |

No |

− 10 |

Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chen, Zhang, Xing, Guan, Cheng and Li2020) |

The benefits, motivations and drawbacks of environmental volunteering in older adults |

Inception to July 2020 |

9 |

SS of 328, most based in Taiwan or the USA. Mean age ranged from 65.6 to 75.7 |

Older adults |

Volunteering with an intention to improve the outdoor environment |

Psychological Physical Social General |

No |

9 |

Conway et al. (Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009) |

Changes associated with service learning and moderators of these changes |

Inception to June 2008 |

103 |

SS of 1,819 for self-evaluations, and 274 for well-being |

None |

Service learning |

Psychological General |

Yes |

− 20 |

Farrell & Bryant (Reference Farrell and Bryant2009) |

Volunteering to promote social inclusion for volunteers with mental health problems |

Not provided |

14 |

Mainly based in the UK or USA, range of subpopulations (e.g. people with disabilities) |

Participants with mental health problems |

Volunteering to promote social inclusion |

Psychological Social General |

No |

− 15 |

Filges et al. (Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020) |

The effects of volunteering on physical and mental health adults aged over 65 |

Inception to December 2018, more searches carried out in September and October 2019 |

90 (26 for this data synthesis) |

Average SS of 2,369 for volunteers, and an average of 61% female. Mostly from the USA, average age of 76 for volunteers |

Older adults aged 65 or over |

Formal volunteering in comparison to non-volunteers |

Psychological Physical General |

Yes |

30 |

Galbraith et al. (Reference Galbraith, Larkin, Moorhouse and Oomen2015) |

The goals, characteristics, and outcomes of intergenerational programmes for children or youth and people with dementia |

Inception to February 2014 |

27 |

No information (only studies were of volunteering) |

People with dementia and participants aged under 19 |

Dementia specific intergenerational programmes |

Psychological |

No |

− 10 |

Giraudeau & Bailly, Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019 |

Characteristics, definition, and benefits of intergenerational programmes for school-aged children and adults aged above 60 years |

2005–2015 |

11 |

SS ranged from 11 to 46 for older volunteers, mostly based in the US |

Older adults aged 60 or over and school-aged children |

Intergenerational programmes |

General |

No |

− 6 |

Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014) |

The general, academic, personal, social, and civic outcomes of community service, and their moderators including reflection |

1980 and September 2012 |

49 |

No information |

Adolescents between 12 and 20 years old without a mental disability |

Volunteering, community service, and service learning |

Psychological Social |

Yes |

− 4 |

Gualano et al. (Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018) |

The effects of intergenerational programmes on elders and children, and the key elements that determine their success |

Not provided |

27 |

SS of older adults ranged from 6 to 162, based mostly in the USA followed by Japan |

Older adults and school or pre-school children |

Intergenerational programmes |

Psychological Physical Social General |

No |

9 |

Höing et al. (Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016) |

To support the development of policy and selection of volunteers working with medium to high risk sex offenders |

1999 to October 2012 |

50 |

Most either focused on adults in general, or older adults aged 55 or over |

For volunteering with sex offenders: working with sec offenders with the aim of reducing the behaviour |

Volunteering in general and volunteering for medium to high risk sex offenders |

Psychological Physical Social General |

No |

− 7 |

Howard & Serviss (Reference Howard and Serviss2022) |

Benefits of corporate volunteering programmes, and whether individual or organisational-level participation is most beneficial |

Inception to May 2020 |

57 |

No information |

Individual or organisational level |

Corporate volunteering programmes |

Psychological General |

Yes |

− 1 |

Hui et al., (Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020) |

Strength of the prosociality to well-being link under different conceptualisations, and their moderators |

Inception to April 2014, more searches conducted in December 2016 and September 2019 |

126 |

No information |

Adults 18 or over |

Prosociality variables (including volunteering) |

General |

Yes |

− 12 |

Hyde et al., (Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014) |

Benefits of episodic volunteering |

Inception to April 2014 |

41 overall (20 within health and social welfare) |

Mostly based in North America, most common age range was 30–60, mostly Caucasian, married, employed, and of middle income |

None |

Episodic volunteering outside of disaster settings and within one’s country (once or on a seasonal or annual basis) |

Social |

No |

− 2 |

Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013 |

Benefits of formal volunteering for physical and mental health and survival, and the influence of volunteering type and intensity |

Inception to January 2013 |

40 |

Mostly based in the USA and North America and recruited those 50 years or over. Total SS of 308 for RCTs and 307 for NRCTs, and most cohort studies recruited samples over 1000 |

Adults aged 16 or over |

Formal volunteering (sustained and regular: over 1 h twice monthly) |

Psychological Physical General |

No |

17 |

Kragt & Holtrop (Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019) |

Characteristics, motivations, benefits, psychological contract, commitment, and withdrawal of volunteering in Australia |

Inception to August 2018 |

152 (it total, on all aspects of volunteering) |

All based in Australia |

Participants in Australia |

None |

Psychological Social General |

No |

− 15 |

Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015) |

Impact of participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities on health and well-being |

Inception to October 2012 |

23 (13 with quantitative data) |

Mostly based in the UK with samples aged between 40 and 60. SS ranged from 3 to 2630 |

None |

Volunteering: outdoor and physically active environmental enhancement or conservation |

Psychological Physical Social General |

No |

0 |

Manjunath & Manoj (Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021) |

Effectiveness of interventions to decrease social isolation in older adults |

No information |

20 |

2 studies eligible for volunteering; 1 international, the other based in Sweden |

Adults aged 50 or over |

Interventions to reduce isolation targeted towards older adults experiencing loneliness (included volunteering) |

Psychological |

No |

− 11 |

Marco-Gardoqui et al. (Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020) |

The academic, personal, and social impact of service learning on students in business schools |

Inception to October 2019 |

32 |

Mean SS of quant studies was 228. Mostly based in the USA. No first year students |

Business students |

Service learning |

Psychological Social |

No |

5 |

Milbourn et al. (Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018) |

The relationship between time spent volunteering and quality of life in adults aged over 50 |

January 2000 to April 2014 |

8 |

SS ranged from 180 to 4860, mostly based in the USA, women, Caucasian, with a variety of income and education levels |

Adults aged 50 or over |

Time spent volunteering |

Psychological Physical Social |

No |

− 8 |

O’Flynn et al. (Reference O’Flynn, Barrett and Murphy2021) |

The motivation and benefits of volunteers in inclusive watersports |

Not provided |

8 for benefits |

No information |

None |

Volunteers in sport or disability inclusion |

Social General |

No |

− 14 |

Okun et al. (Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013) |

The relationship between organisational volunteering and mortality in adults aged over 55 |

Inception to November 2011 |

13 |

Mainly based in the USA. SS ranged from 868 to 15,938. Median age was 66.5 years |

Older adults |

Organisational volunteering |

General |

Yes |

− 9 |

Onyx & Warburton (Reference Onyx and Warburton2003) |

To investigate the relationship between volunteering and health among older people |

Not provided (searched last 10 years) |

25 |

Developed countries, mostly the USA and Australia |

Older adults |

Volunteering |

Psychological Physical General |

No |

− 22 |

Owen et al., (Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) |

The effectiveness of purposeful activity on well-being and quality of life outcomes in ‘oldest old’ adults (aged over 80) |

Inception to April 2020 |

8 (5 for volunteering) |

Mostly from the USA, SS ranged from 10 to 88 |

Older adults with a mean age of 80 or above |

Purposeful activity (divided into volunteering and learning a new skill) |

Psychological General |

No |

5 |

Bonsdorff & Rantanen (Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011) |

The relationship between formal volunteering and well-being for older volunteers and the people they serve |

Inception to November 2009 |

16 |

All based in the USA. SS ranged from 705 to 7496 for prospective studies, the SS for the included RCT was 128. Ages ranged between 60 and 97 for the prospective studies, mostly women and White, and were more highly educated and were of better perceived health than non-volunteers |

Adults aged 60 or over |

Volunteering in visits or within a timeframe |

Psychological Physical General |

No |

-14 |

Wheeler et al (Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998) |

The effectiveness of volunteering for older adults and the people they serve |

No information |

37 (30 for outcomes of volunteers) |

SS ranged from 15 to 2164 (median 98), mostly based in the USA. Average age was 71, mostly White (90%) and female (72%) |

Older adults |

All forms of volunteering |

Psychological |

Yes |

− 17 |

Willems et al. (Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020) |

The mental well-being of crisis line volunteers and moderators |

Inception to November 2018 |

13 |

SS ranged from 28 to 216 for the quantitative surveys. Sample were a range of ages and mostly female |

Crisis line volunteers |

Volunteers from a crisis line or chat line |

Psychological Social |

No |

1 |

Several of the included meta-analyses, whilst employing a systematic search, did not perform any form of narrative synthesis alongside the results of the meta-analyses, meaning information about the characteristics of included studies was missing.

Publication Bias

Seven of the included reviews applied a meta-analysis (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014); Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020; Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013; Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998). Of these, five reported testing for publication bias (Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014); Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020; Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013; Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998). Generally, there was no strong evidence to indicate publication bias, although one review found a likelihood of publication bias specifically for the analyses of moderators on the risk of mortality (Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013). Also, one review reported three approaches to assess publication bias which gave mixed findings (Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020), and as the remaining reviews assessed publication bias in a variety of ways such as funnel plots (Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020), publication as a moderator (Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014)), trim and fill procedure (Okun et al., Reference Okun, Yeung and Brown2013), and Rosenthal’s failsafe (Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998), results may not be reliable.

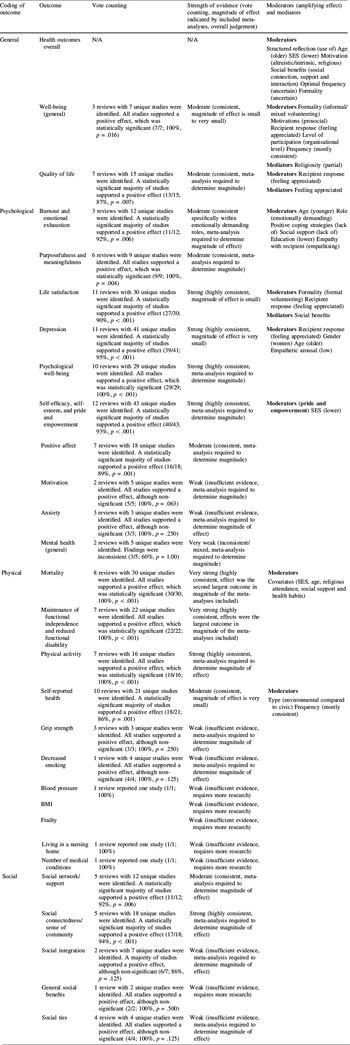

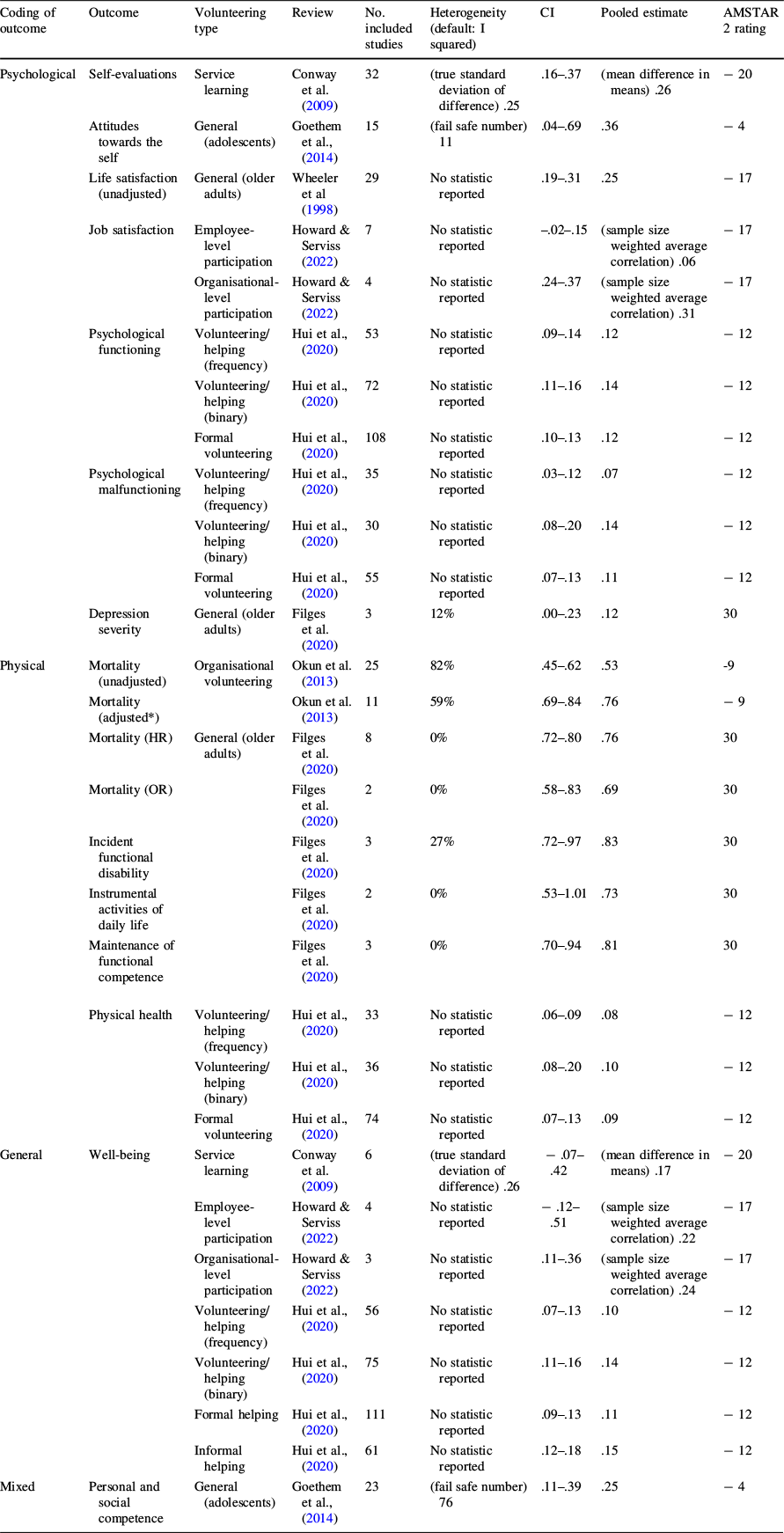

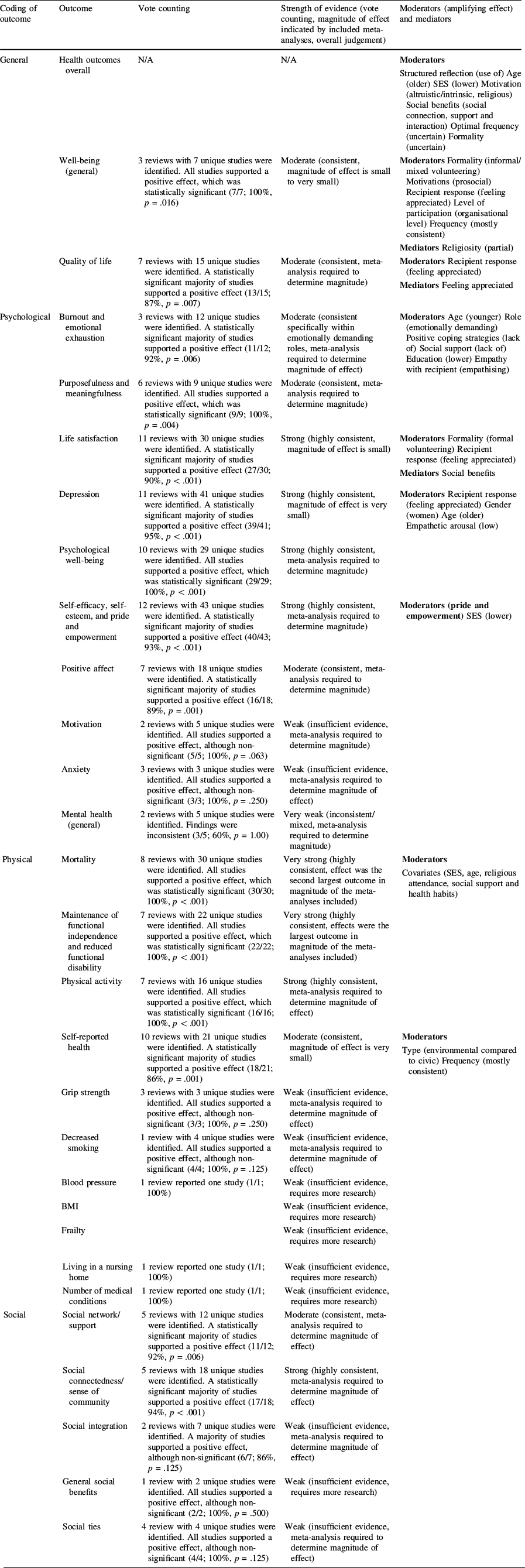

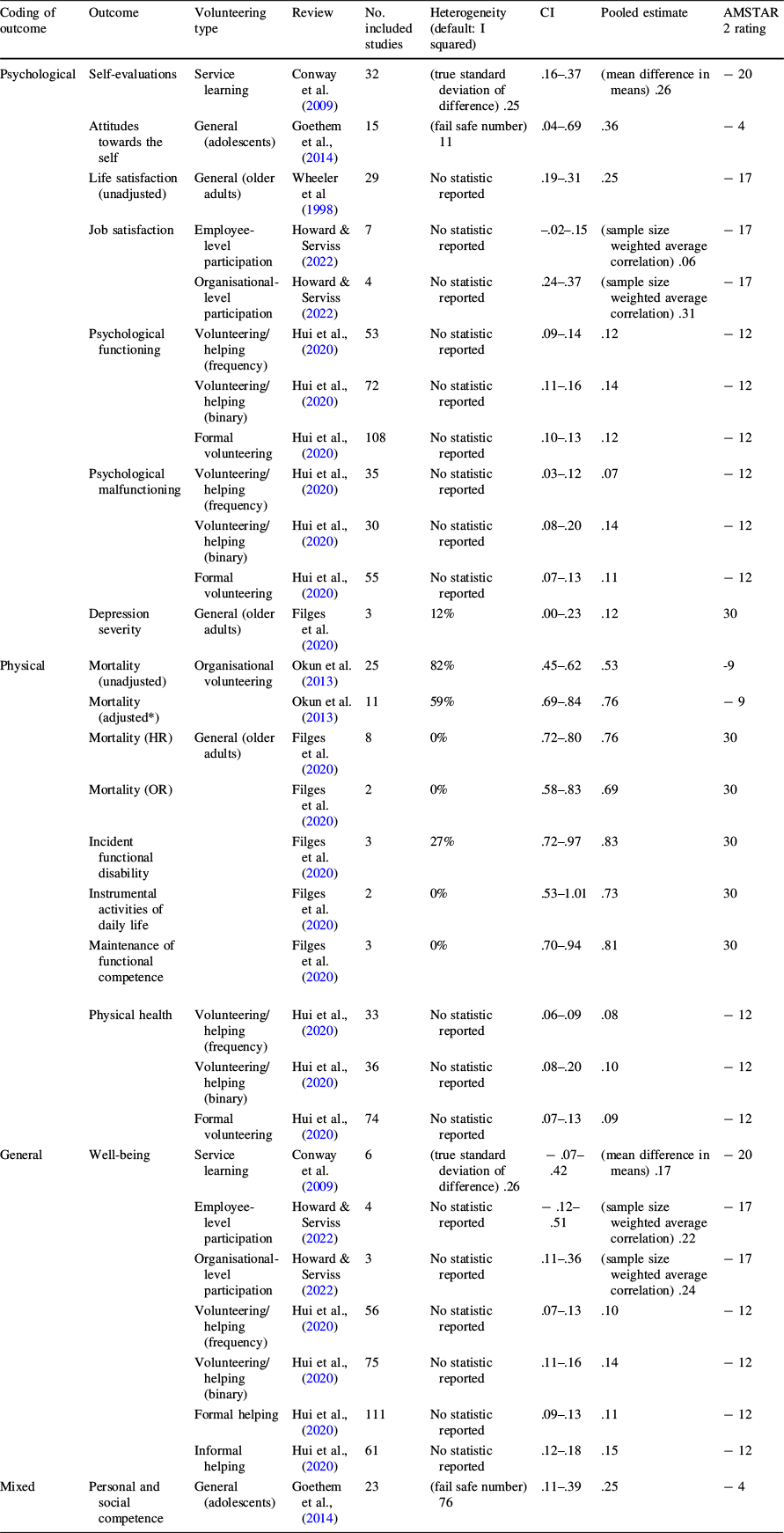

Findings

Results of vote counting by direction of effect from the 18 included reviews are shown in Table 3. Five meta-analysis did not provide sufficient information to be included (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009; Goethem et al., (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014); Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020; Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998), and one only provided sufficient information to include one variable (Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011).

Table 3 Summary table of direction and strength of evidence for each outcome, and strength of potential moderators and mediators

Coding of outcome |

Outcome |

Vote counting |

Strength of evidence (vote counting, magnitude of effect indicated by included meta-analyses, overall judgement) |

Moderators (amplifying effect) and mediators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

General |

Health outcomes overall |

N/A |

N/A |

Moderators Structured reflection (use of) Age (older) SES (lower) Motivation (altruistic/intrinsic, religious) Social benefits (social connection, support and interaction) Optimal frequency (uncertain) Formality (uncertain) |

Well-being (general) |

3 reviews with 7 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (7/7; 100%, p = .016) |

Moderate (consistent, magnitude of effect is small to very small) |

Moderators Formality (informal/mixed volunteering) Motivations (prosocial) Recipient response (feeling appreciated) Level of participation (organisational level) Frequency (mostly consistent) Mediators Religiosity (partial) |

|

Quality of life |

7 reviews with 15 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (13/15; 87%, p = .007) |

Moderate (consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

Moderators Recipient response (feeling appreciated) Mediators Feeling appreciated |

|

Psychological |

Burnout and emotional exhaustion |

3 reviews with 12 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (11/12; 92%, p = .006) |

Moderate (consistent specifically within emotionally demanding roles, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

Moderators Age (younger) Role (emotionally demanding) Positive coping strategies (lack of) Social support (lack of) Education (lower) Empathy with recipient (empathising) |

Purposefulness and meaningfulness |

6 reviews with 9 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (9/9; 100%, p = .004) |

Moderate (consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

||

Life satisfaction |

11 reviews with 30 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (27/30; 90%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, magnitude of effect is small) |

Moderators Formality (formal volunteering) Recipient response (feeling appreciated) Mediators Social benefits |

|

Depression |

11 reviews with 41 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (39/41; 95%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, magnitude of effect is very small) |

Moderators Recipient response (feeling appreciated) Gender (women) Age (older) Empathetic arousal (low) |

|

Psychological well-being |

10 reviews with 29 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (29/29; 100%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

||

Self-efficacy, self-esteem, and pride and empowerment |

12 reviews with 43 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (40/43; 93%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

Moderators (pride and empowerment) SES (lower) |

|

Positive affect |

7 reviews with 18 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (16/18; 89%, p = .001) |

Moderate (consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

||

Motivation |

2 reviews with 5 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (5/5; 100%, p = .063) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

||

Anxiety |

3 reviews with 3 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (3/3; 100%, p = .250) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

Mental health (general) |

2 reviews with 5 unique studies were identified. Findings were inconsistent (3/5; 60%, p = 1.00) |

Very weak (inconsistent/mixed, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude) |

||

Physical |

Mortality |

8 reviews with 30 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (30/30; 100%, p < .001) |

Very strong (highly consistent, effect was the second largest outcome in magnitude of the meta-analyses included) |

Moderators Covariates (SES, age, religious attendance, social support and health habits) |

Maintenance of functional independence and reduced functional disability |

7 reviews with 22 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (22/22; 100%, p < .001) |

Very strong (highly consistent, effects were the largest outcome in magnitude of the meta-analyses included) |

||

Physical activity |

7 reviews with 16 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, which was statistically significant (16/16; 100%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

Self-reported health |

10 reviews with 21 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (18/21; 86%, p = .001) |

Moderate (consistent, magnitude of effect is very small) |

Moderators Type (environmental compared to civic) Frequency (mostly consistent) |

|

Grip strength |

3 reviews with 3 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (3/3; 100%, p = .250) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

Decreased smoking |

1 review with 4 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (4/4; 100%, p = .125) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

Blood pressure |

1 review reported one study (1/1; 100%) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

||

BMI |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

|||

Frailty |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

|||

Living in a nursing home |

1 review reported one study (1/1; 100%) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

||

Number of medical conditions |

1 review reported one study (1/1; 100%) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

||

Social |

Social network/ support |

5 reviews with 12 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (11/12; 92%, p = .006) |

Moderate (consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

|

Social connectedness/ sense of community |

5 reviews with 18 unique studies were identified. A statistically significant majority of studies supported a positive effect (17/18; 94%, p < .001) |

Strong (highly consistent, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

Social integration |

2 reviews with 7 unique studies were identified. A majority of studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (6/7; 86%, p = .125) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

||

General social benefits |

1 review with 2 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (2/2; 100%, p = .500) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, requires more research) |

||

Social ties |

4 review with 4 unique studies were identified. All studies supported a positive effect, although non-significant (4/4; 100%, p = .125) |

Weak (insufficient evidence, meta-analysis required to determine magnitude of effect) |

Coding used to describe strength of the evidence: Highly consistent: vote counting significant at the p < .001 level. Consistent; vote counting significant at the p = .05 level. Insufficient evidence; all in favour, but binomial test non-significant, Inconsistent: highly mixed. Magnitude of effect; small (OR of between .30 and .20), very small (OR below .10). Overall judgement: very strong (highly consistent, largest effect size), strong (highly consistent, small effect size), moderate (consistent, no pooled effect size determined or small to very small effect), weak (insufficient evidence), very weak (inconsistent evidence)

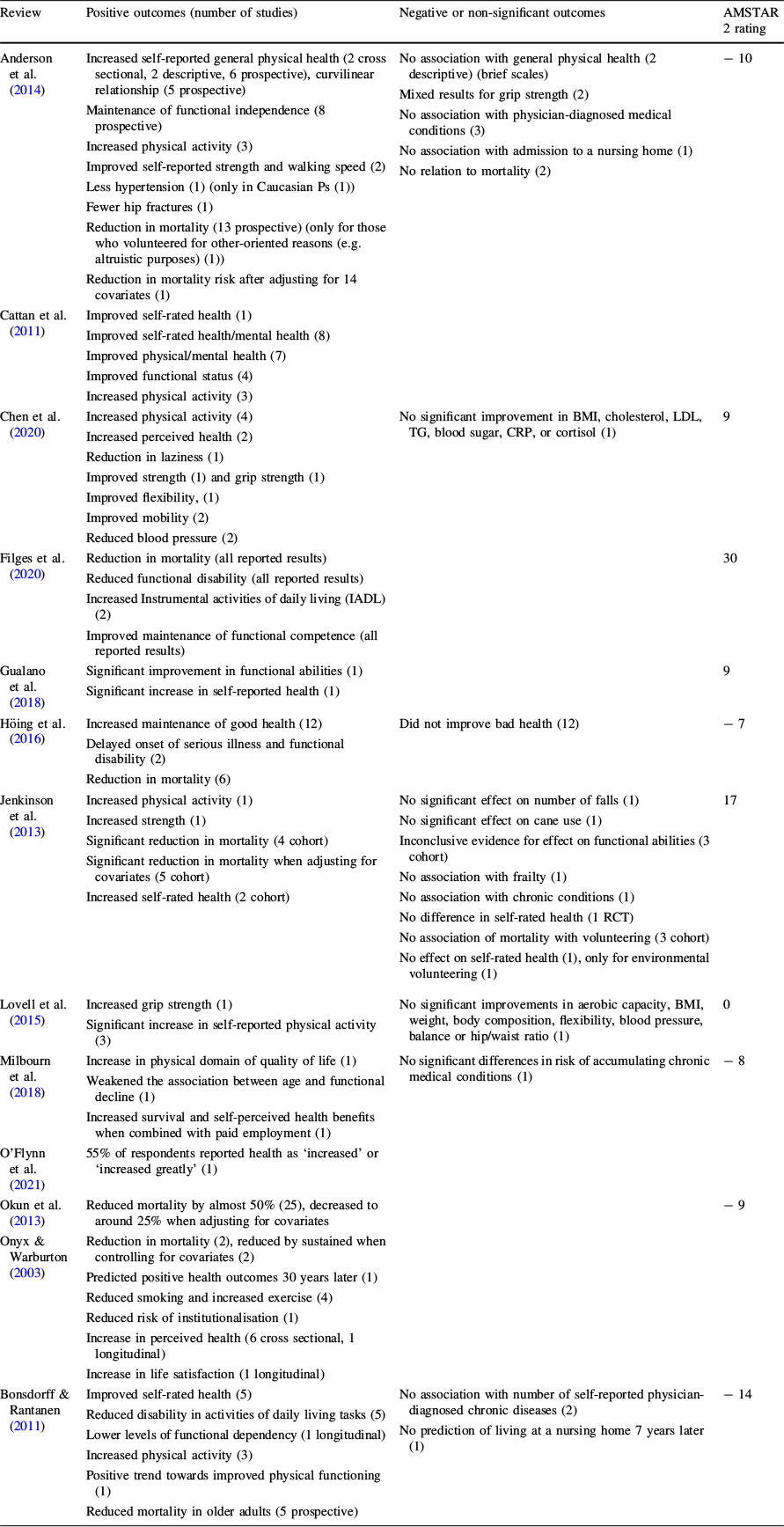

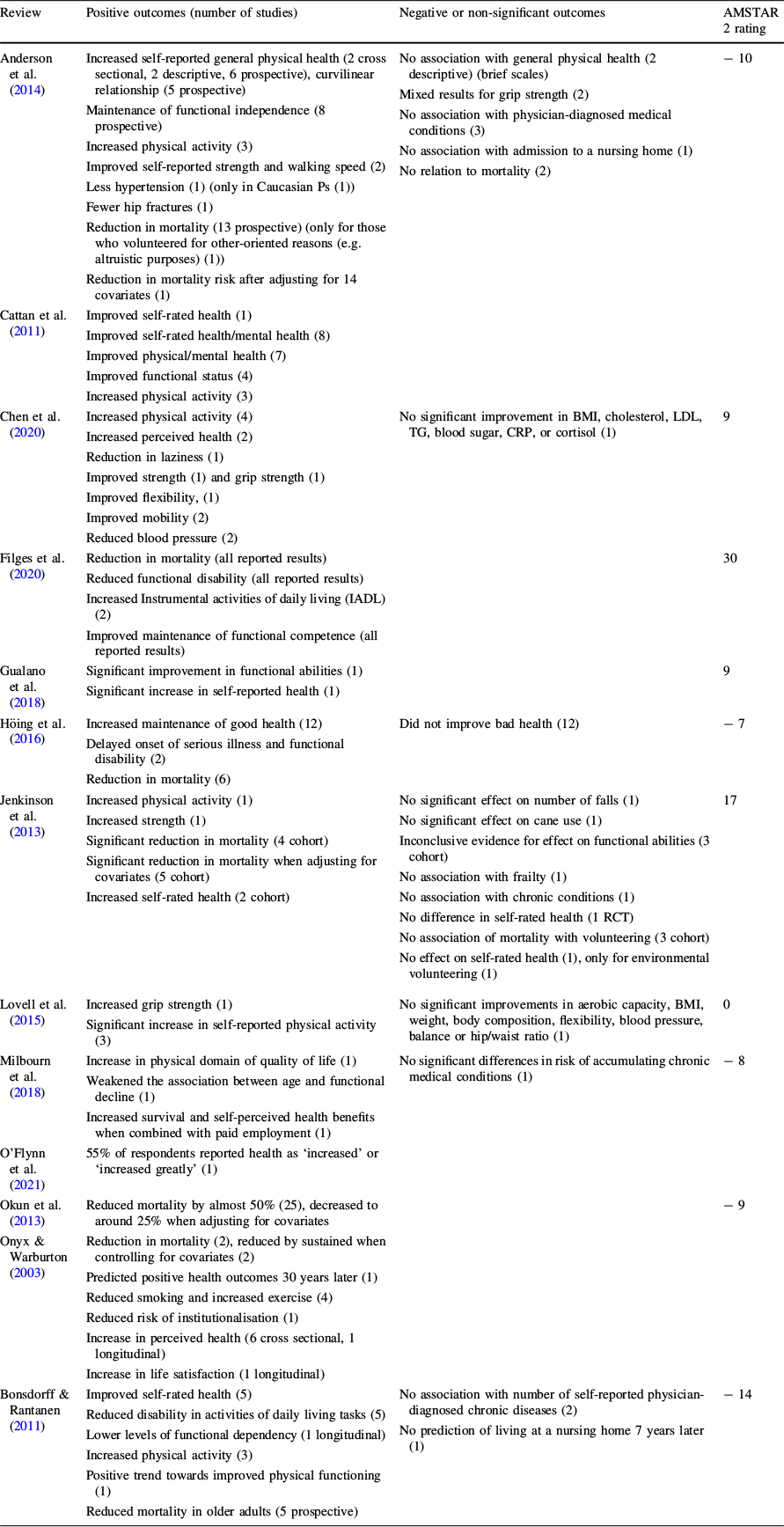

General Effects on Health and Well-being

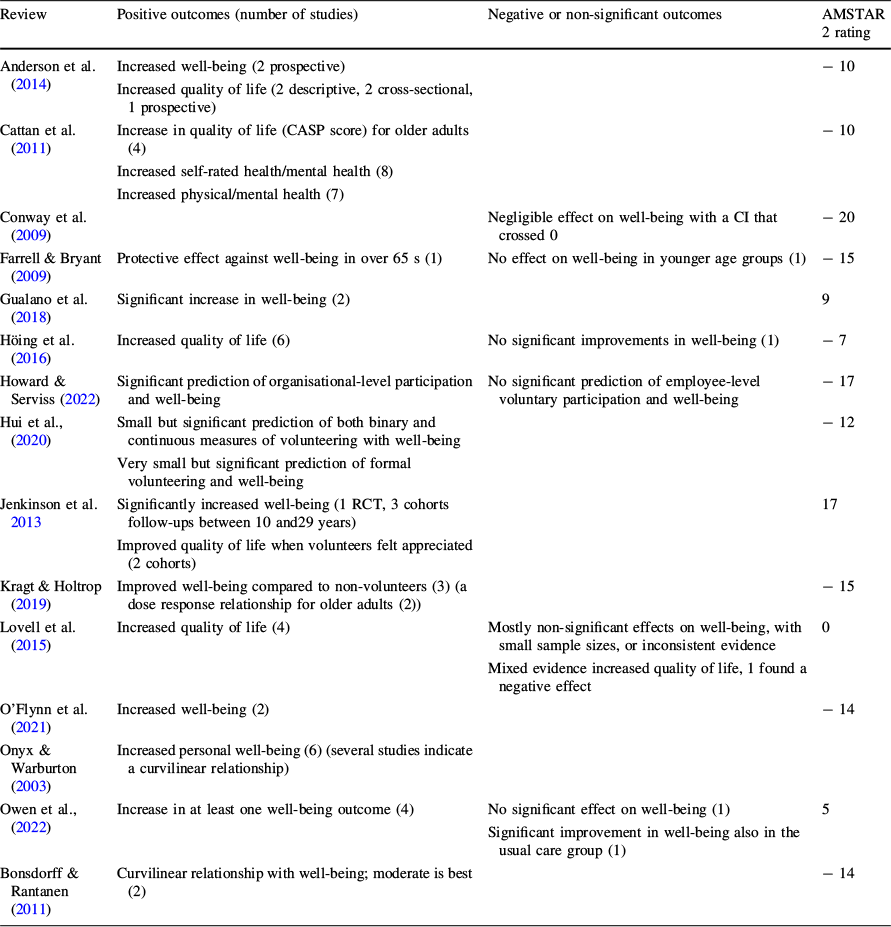

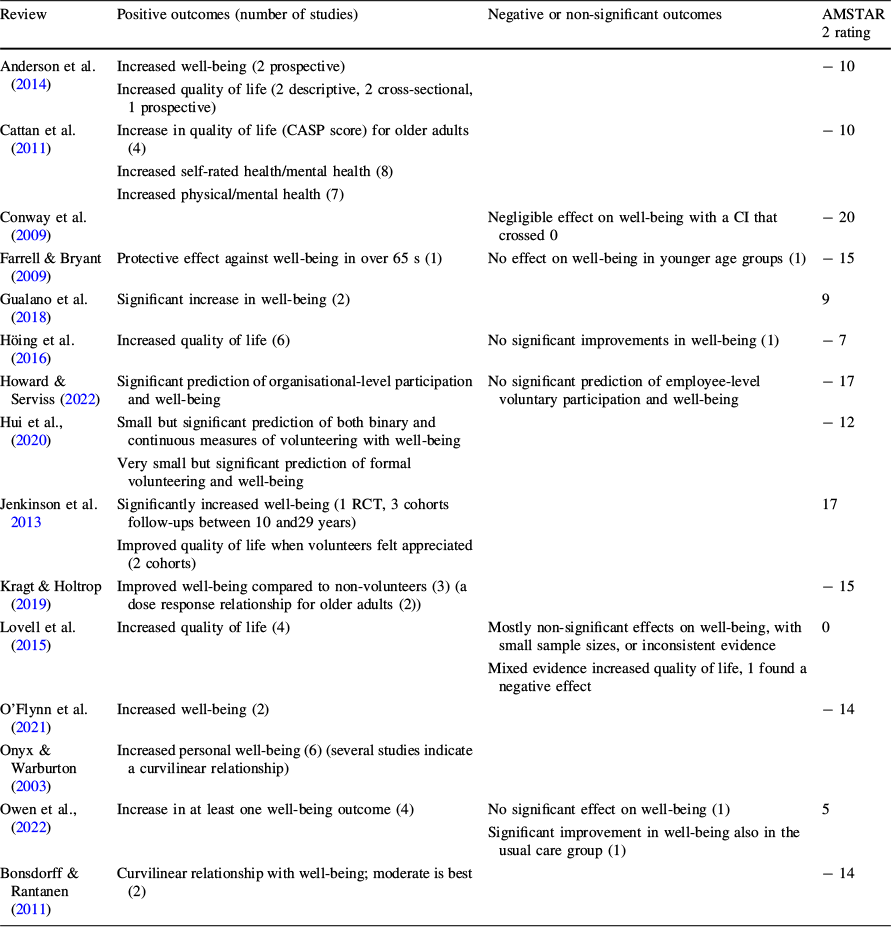

Fifteen of the included reviews reported general effects on health and well-being (Table 4). Reviews reporting on composite, general measures of health mainly assessed well-being, although others measured quality of life. Generally, most reviews reported that volunteering improved well-being (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Gualano et al., Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018; Hui et al., Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020; Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013; Kragt & Holtrop, Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019; O’Flynn et al., Reference O’Flynn, Barrett and Murphy2021; Onyx & Warburton, Reference Onyx and Warburton2003; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) and quality of life (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Höing et al., Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016). However, the relationship with well-being was often small and with exceptions (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009), and one review found most studies reported no significant impact on well-being or quality of life (Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015), possibly because the review assessed environmental volunteering specifically. The review that reported on quality of life with the highest quality reported only significant positive relationships between volunteering and well-being and quality of life (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013), although there was evidence to suggest an impact on quality of life only when volunteers felt their contribution was appreciated (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013). One review found only organisational level and not individual level participation in volunteering to significantly increase well-being (Howard & Serviss, Reference Howard and Serviss2022), another found increased well-being for older but not younger people (Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009), and another found a curvilinear relationship such that a moderate intensity of volunteering was most beneficial (Bonsdorff & Rantanen Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011).

Table 4 General benefits

Review |

Positive outcomes (number of studies) |

Negative or non-significant outcomes |

AMSTAR 2 rating |

|---|---|---|---|

Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014) |

Increased well-being (2 prospective) Increased quality of life (2 descriptive, 2 cross-sectional, 1 prospective) |

− 10 |

|

Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011) |

Increase in quality of life (CASP score) for older adults (4) Increased self-rated health/mental health (8) Increased physical/mental health (7) |

− 10 |

|

Conway et al. (Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009) |

Negligible effect on well-being with a CI that crossed 0 |

− 20 |

|

Farrell & Bryant (Reference Farrell and Bryant2009) |

Protective effect against well-being in over 65 s (1) |

No effect on well-being in younger age groups (1) |

− 15 |

Gualano et al. (Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018) |

Significant increase in well-being (2) |

9 |

|

Höing et al. (Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016) |

Increased quality of life (6) |

No significant improvements in well-being (1) |

− 7 |

Howard & Serviss (Reference Howard and Serviss2022) |

Significant prediction of organisational-level participation and well-being |

No significant prediction of employee-level voluntary participation and well-being |

− 17 |

Hui et al., (Reference Hui, Ng, Berzaghi, Cunningham-Amos and Kogan2020) |

Small but significant prediction of both binary and continuous measures of volunteering with well-being Very small but significant prediction of formal volunteering and well-being |

− 12 |

|

Jenkinson et al. Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013 |

Significantly increased well-being (1 RCT, 3 cohorts follow-ups between 10 and29 years) Improved quality of life when volunteers felt appreciated (2 cohorts) |

17 |

|

Kragt & Holtrop (Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019) |

Improved well-being compared to non-volunteers (3) (a dose response relationship for older adults (2)) |

− 15 |

|

Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015) |

Increased quality of life (4) |

Mostly non-significant effects on well-being, with small sample sizes, or inconsistent evidence Mixed evidence increased quality of life, 1 found a negative effect |

0 |

O’Flynn et al. (Reference O’Flynn, Barrett and Murphy2021) |

Increased well-being (2) |

− 14 |

|

Onyx & Warburton (Reference Onyx and Warburton2003) |

Increased personal well-being (6) (several studies indicate a curvilinear relationship) |

||

Owen et al., (Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) |

Increase in at least one well-being outcome (4) |

No significant effect on well-being (1) Significant improvement in well-being also in the usual care group (1) |

5 |

Bonsdorff & Rantanen (Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011) |

Curvilinear relationship with well-being; moderate is best (2) |

− 14 |

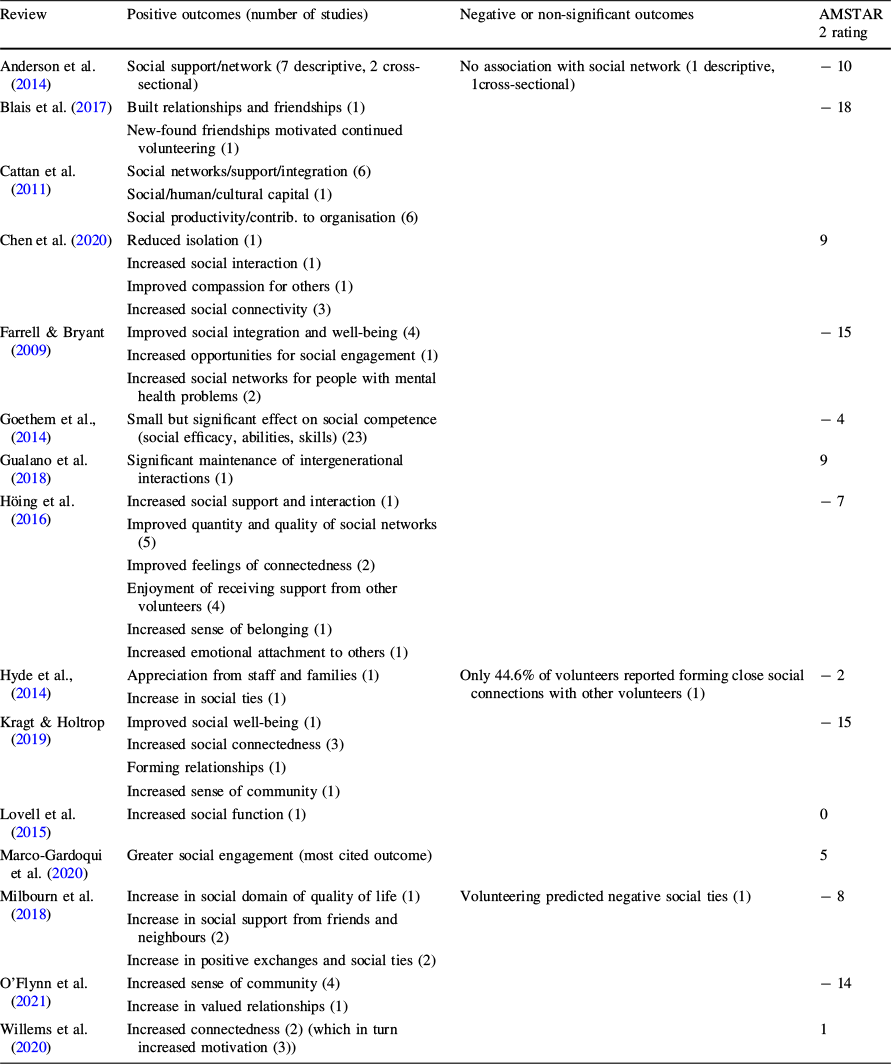

Psychological Effects on Health and Well-being

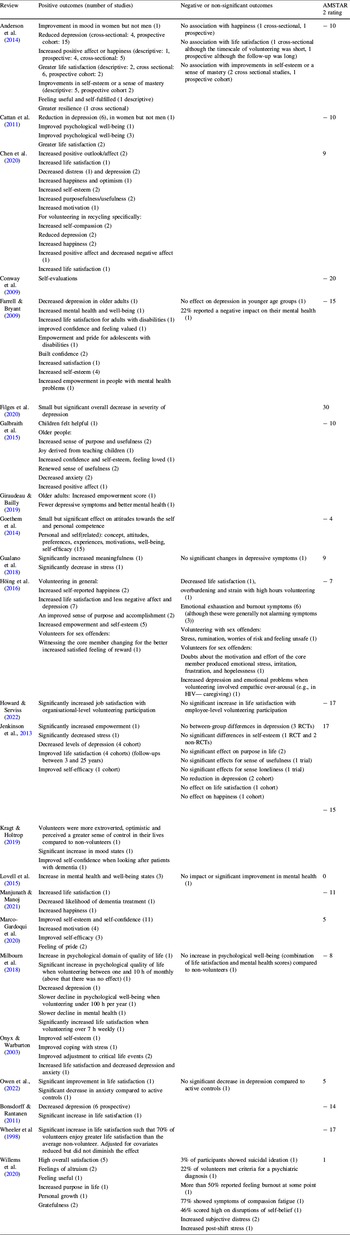

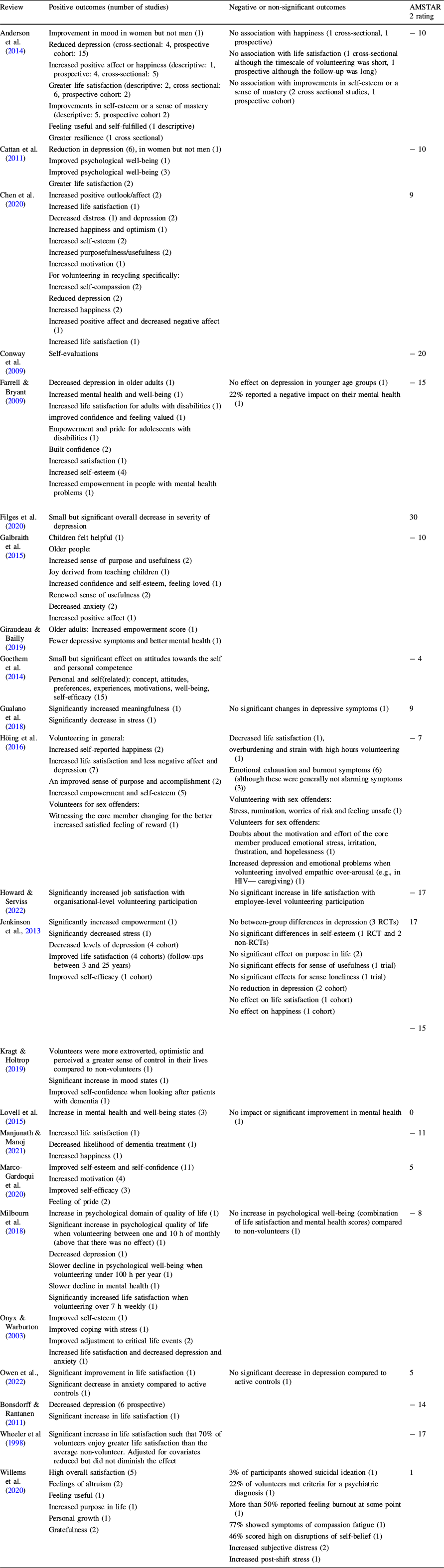

Psychological effects were the most commonly reported health and well-being outcome of volunteering, reported by 23 reviews (Table 5). The reviews that reported on general mental health reported mixed findings (Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015; Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018), likely due to the large variation in how mental health was defined and measured. Whilst some considered mental health to be a distinct factor (Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009; Lovell et al., Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015), others combined factors such as life satisfaction into a composite measure of mental health (Milbourn et al., Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018).

Table 5 Psychological benefits. Displayed in brackets are the number of primary included studies to support the review findings. Where no brackets are provided, findings are the result of meta-analyses

Review |

Positive outcomes (number of studies) |

Negative or non-significant outcomes |

AMSTAR 2 rating |

|---|---|---|---|

Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014) |

Improvement in mood in women but not men (1) Reduced depression (cross-sectional: 4, prospective cohort: 15) Increased positive affect or happiness (descriptive: 1, prospective: 4, cross-sectional: 5) Greater life satisfaction (descriptive: 2, cross sectional: 6, prospective cohort: 2) Improvements in self-esteem or a sense of mastery (descriptive: 5, prospective cohort 2) Feeling useful and self-fulfilled (1 descriptive) Greater resilience (1 cross sectional) |

No association with happiness (1 cross-sectional, 1 prospective) No association with life satisfaction (1 cross-sectional although the timescale of volunteering was short, 1 prospective although the follow-up was long) No association with improvements in self-esteem or a sense of mastery (2 cross sectional studies, 1 prospective cohort) |

− 10 |

Cattan et al. (Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011) |

Reduction in depression (6), in women but not men (1) Improved psychological well-being (1) Improved psychological well-being (3) Greater life satisfaction (2) |

− 10 |

|

Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chen, Zhang, Xing, Guan, Cheng and Li2020) |

Increased positive outlook/affect (2) Increased life satisfaction (1) Decreased distress (1) and depression (2) Increased happiness and optimism (1) Increased self-esteem (2) Increased purposefulness/usefulness (2) Increased motivation (1) For volunteering in recycling specifically: Increased self-compassion (2) Reduced depression (2) Increased happiness (2) Increased positive affect and decreased negative affect (1) Increased life satisfaction (1) |

9 |

|

Conway et al. (Reference Conway, Amel and Gerwien2009) |

Self-evaluations |

− 20 |

|

Farrell & Bryant (Reference Farrell and Bryant2009) |

Decreased depression in older adults (1) Increased mental health and well-being (1) Increased life satisfaction for adults with disabilities (1) improved confidence and feeling valued (1) Empowerment and pride for adolescents with disabilities (1) Built confidence (2) Increased satisfaction (1) Increased self-esteem (4) Increased empowerment in people with mental health problems (1) |

No effect on depression in younger age groups (1) 22% reported a negative impact on their mental health (1) |

− 15 |

Filges et al. (Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020) |

Small but significant overall decrease in severity of depression |

30 |

|

Galbraith et al. (Reference Galbraith, Larkin, Moorhouse and Oomen2015) |

Children felt helpful (1) Older people: Increased sense of purpose and usefulness (2) Joy derived from teaching children (1) Increased confidence and self-esteem, feeling loved (1) Renewed sense of usefulness (2) Decreased anxiety (2) Increased positive affect (1) |

− 10 |

|

Giraudeau & Bailly (Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019) |

Older adults: Increased empowerment score (1) Fewer depressive symptoms and better mental health (1) |

||

Goethem et al. (Reference Goethem, Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014) |

Small but significant effect on attitudes towards the self and personal competence Personal and self(related): concept, attitudes, preferences, experiences, motivations, well-being, self-efficacy (15) |

− 4 |

|

Gualano et al. (Reference Gualano, Voglino, Bert, Thomas, Camussi and Siliquini2018) |

Significantly increased meaningfulness (1) Significantly decrease in stress (1) |

No significant changes in depressive symptoms (1) |

9 |

Höing et al. (Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016) |

Volunteering in general: Increased self-reported happiness (2) Increased life satisfaction and less negative affect and depression (7) An improved sense of purpose and accomplishment (2) Increased empowerment and self-esteem (5) Volunteers for sex offenders: Witnessing the core member changing for the better increased satisfied feeling of reward (1) |

Decreased life satisfaction (1), overburdening and strain with high hours volunteering (1) Emotional exhaustion and burnout symptoms (6) (although these were generally not alarming symptoms (3)) Volunteering with sex offenders: Stress, rumination, worries of risk and feeling unsafe (1) Volunteers for sex offenders: Doubts about the motivation and effort of the core member produced emotional stress, irritation, frustration, and hopelessness (1) Increased depression and emotional problems when volunteering involved empathic over-arousal (e.g., in HIV— caregiving) (1) |

− 7 |

Howard & Serviss (Reference Howard and Serviss2022) |

Significantly increased job satisfaction with organisational-level volunteering participation |

No significant increase in life satisfaction with employee-level volunteering participation |

− 17 |

Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013 |

Significantly increased empowerment (1) Significantly decreased stress (1) Decreased levels of depression (4 cohort) Improved life satisfaction (4 cohorts) (follow-ups between 3 and 25 years) Improved self-efficacy (1 cohort) |

No between-group differences in depression (3 RCTs) No significant differences in self-esteem (1 RCT and 2 non-RCTs) No significant effect on purpose in life (2) No significant effects for sense of usefulness (1 trial) No significant effects for sense loneliness (1 trial) No reduction in depression (2 cohort) No effect on life satisfaction (1 cohort) No effect on happiness (1 cohort) |

17 |

Kragt & Holtrop (Reference Kragt and Holtrop2019) |

Volunteers were more extroverted, optimistic and perceived a greater sense of control in their lives compared to non-volunteers (1) Significant increase in mood states (1) Improved self-confidence when looking after patients with dementia (1) |

− 15 |

|

Lovell et al. (Reference Lovell, Husk, Cooper, Stahl-Timmins and Garside2015) |

Increase in mental health and well-being states (3) |

No impact or significant improvement in mental health (1) |

0 |

Manjunath & Manoj (Reference Manjunath and Manoj2021) |

Increased life satisfaction (1) Decreased likelihood of dementia treatment (1) Increased happiness (1) |

− 11 |

|

Marco-Gardoqui et al. (Reference Marco-Gardoqui, Eizaguirre and García-Feijoo2020) |

Improved self-esteem and self-confidence (11) Increased motivation (4) Improved self-efficacy (3) Feeling of pride (2) |

5 |

|

Milbourn et al. (Reference Milbourn, Jaya and Buchanan2018) |

Increase in psychological domain of quality of life (1) Significant increase in psychological quality of life when volunteering between one and 10 h of monthly (above that there was no effect) (1) Decreased depression (1) Slower decline in psychological well-being when volunteering under 100 h per year (1) Slower decline in mental health (1) Significantly increased life satisfaction when volunteering over 7 h weekly (1) |

No increase in psychological well-being (combination of life satisfaction and mental health scores) compared to non-volunteers (1) |

− 8 |

Onyx & Warburton (Reference Onyx and Warburton2003) |

Improved self-esteem (1) Improved coping with stress (1) Improved adjustment to critical life events (2) Increased life satisfaction and decreased depression and anxiety (1) |

||

Owen et al., (Reference Owen, Berry and Brown2022) |

Significant improvement in life satisfaction (1) Significant decrease in anxiety compared to active controls (1) |

No significant decrease in depression compared to active controls (1) |

5 |

Bonsdorff & Rantanen (Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011) |

Decreased depression (6 prospective) Significant increase in life satisfaction (1) |

− 14 |

|

Wheeler et al (Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998) |

Significant increase in life satisfaction such that 70% of volunteers enjoy greater life satisfaction than the average non-volunteer. Adjusted for covariates reduced but did not diminish the effect |

− 17 |

|

Willems et al. (Reference Willems, Drossaert, Vuijk and Bohlmeijer2020) |

High overall satisfaction (5) Feelings of altruism (2) Feeling useful (1) Increased purpose in life (1) Personal growth (1) Gratefulness (2) |

3% of participants showed suicidal ideation (1) 22% of volunteers met criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis (1) More than 50% reported feeling burnout at some point (1) 77% showed symptoms of compassion fatigue (1) 46% scored high on disruptions of self-belief (1) Increased subjective distress (2) Increased post-shift stress (1) |

1 |

The main effects of volunteering on psychological well-being clustered around those affecting mood and affect, and self-evaluations and concepts. For affect outcomes, reviews mostly reported a significant positive improvement in depression scores (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Bonsdorff & Rantanen Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020; Giraudeau & Bailly, Reference Giraudeau and Bailly2019; Höing et al., Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016; Onyx & Warburton, Reference Onyx and Warburton2003). Only one review reported highly mixed findings (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013), possibly attributable to the higher quality of included primary studies (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013). Reviews reporting a smaller number of contributing studies found possible moderators; two reported a reduction in depression in women but not men (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson, Binns, Bernstein, Caspi and Cook2014; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011), one found a reduction in older but not younger populations (Farrell & Bryant, Reference Farrell and Bryant2009), and another found a reduction for general volunteering but increased depression for volunteering involving high empathetic arousal (Höing et al., Reference Höing, Bogaerts and Vogelvang2016). In support of age as a moderator, the reviews finding a consistent positive effect on depression mainly focused on older adults (Bonsdorff & Rantanen Reference von Bonsdorff and Rantanen2011; Cattan et al., Reference Cattan, Hogg and Hardill2011; Filges et al., Reference Filges, Siren, Fridberg and Nielsen2020), and the review with mixed findings included adults of all ages (Jenkinson et al., Reference Jenkinson, Dickens, Jones, Thompson-Coon, Taylor, Rogers, Bambra, Lang and Richards2013).