Introduction

Time is a scarce resource in politics, which motivates political actors to decide strategically the sequence and order of their activities (Döring, Reference Döring and Döring1995; Linz, Reference Linz1998). In European parliamentary democracies, the scarcity of time is manifested by the constitutionally fixed maximum length of a government or legislature tenure, renewable with competitive elections (Döring, Reference Döring and Döring1995, pp. 242–243). While varying across countries and over time, the length of a parliamentary term determines the upper limit of the number of policies a government could possibly propose and enact (Van Schagen, Reference Van Schagen1997). In governments ruled by a single majority party, policymaking largely follows the agenda and schedule determined by the ruling party (Miller, Reference Miller1956). However, the situation becomes complicated in coalition governments when two or more parties share governing responsibility, distribute policy agendas, coordinate policymaking efforts and compete for the influence on final policy outcomes (see, e.g., L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2003; Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003, Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008, Reference Strøm, Müller and Smith2010). Parties in a coalition government can only agree upon a single policy at a time, which may reflect either the jurisdiction of a single party that controls the corresponding ministry (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996) or a compromise reached among all coalition partners (Austen‐Smith & Banks, Reference Austen‐Smith and Banks1988; Becher, Reference Becher2010; Goodhart, Reference Goodhart2013; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014). The coordination and cooperation problem among coalition parties becomes further exacerbated when coalition parties need to consider not only policy contents but also the temporal dimension of their initiation and enactment (Döring, Reference Döring2001).

In most parliamentary democracies, legislation pending at the end of a term is not automatically carried over to the next legislature renewed by elections (Van Schagen, Reference Van Schagen1997). Even in countries without legislative time limits or in cases where a party can re‐introduce a pending bill in the next term, legislators attempt to achieve timely policy goals due to concerns about reputation costs, and uncertainty about coalition formation, portfolio allocation and parliamentary scrutiny in the next term (Falcó‐Gimeno & Indridason, Reference Falcó‐Gimeno and Indridason2013). Thus, the rhythm of elections generates not only policy cycles but also time pressure for coalition parties to fulfill their policy commitment within a term. Under time constraints, the temporal dimension of agenda control and decisions of when to propose what policies, in which sequence and at what speed are crucial for the policy and electoral success of political parties, who have to compete individually at election time for a relatively fixed number of votes in a country (Laver & Schofield, Reference Laver and Schofield1990). However, despite the recent progress in research on the temporal perspective of coalition governance (see, e.g., Döring, Reference Döring2001; T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022; Lupia & Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995; L. Martin, Reference Martin2004; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004), we are still limited by our understanding of how this temporal consideration impacts policy agendas of ministers and whether interactions among coalition parties on policymaking vary over time.

This article aims at advancing our understanding of coalition governance and multiparty policymaking by looking at the interaction between ministers and coalition partners in agenda control under time constraints. The key premise of this study is that the pace of policymaking in coalition governments is set by the legislative cycles commenced with new elections. Since most policymaking activities have to start anew after formation of a new legislature, ministers face stringent time pressure to draft, propose and enact their policy projects. Coalition partners, on the other hand, have to ensure within a limited period that policies proposed by ministers do not systematically deviate from their own preferences and the compromise reached in the coalition agreement. I address the dynamics of coalition policymaking under time pressure by proposing a game‐theoretical model, which explicitly accounts for time budgets and specifies different timing strategies ministers may adopt in the face of time constraints. The equilibrium analysis demonstrates that depending on the available time budget and the scrutiny of coalition partners, ministers adopt distinct strategies within a term to maximize policy and/or office benefits. In particular, in contrast to a productivity‐maximizing early initiation strategy in earlier periods of a term, I identify in the late term a postponing strategy by which ministers intentionally delay policy proposals in the face of coalition scrutiny, which enhances reelection chances of the ministerial parties at the cost of policy enactment.

To empirically test my argument, I take advantage of recently published data on governmental policy proposals that document detailed information on the timing of governmental legislative bills in European parliamentary democracies over a period of 30 years (T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022). I treat parliamentary terms as policymaking cycles with varying time constraints and account for the cyclical structure of the data by applying a circular modelling strategy (Gill & Hangartner, Reference Gill and Hangartner2010). By directly modelling time budgets, the model allows for estimating time‐varying effects over a term. Thereby, the new empirical approach not only addresses variation in timing strategies of ministers over time and across nations but also significantly improves the explanatory power of the model.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, the paper promotes our understanding of coalition governance by emphasizing, besides ministerial discretion and institutional arrangements (see, e.g., Austen‐Smith & Banks, Reference Austen‐Smith and Banks1988; Becher, Reference Becher2010; Goodhart, Reference Goodhart2013; Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Laver & Budge, Reference Laver and Budge1992; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014, Reference Martin and Vanberg2019, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020), a temporal condition that is imposed on both ministers and coalition partners. I emphasize that the extent to which a policy outcome represents the ministerial jurisdiction or coalition compromise also depends on the time a policy has been made. While early initiation of a policy allows coalition partners to thoroughly scrutinize ministerial proposals, postponing policies until close to the end of the term, though risking policy failure, reduces partners' time budget for scrutiny and thus enhances ministerial autonomy.

Second, advancing the studies that have established the micro‐foundation for explaining timing decisions of ministers (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004), I combine the arguments on ministerial agenda setting at the aggregated level with a dynamic policy learning perspective at the individual level. While T. König et al. (Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022) have revealed an important heuristic learning mechanism in which timing decisions of ministers depend on the acquired knowledge about partners' types on an ad hoc basis, I emphasize that ministers will also calculate time budgets and set up timetables to allocate policy priorities across the term. This not only reduces cognitive burden, policy uncertainty and learning costs of ministers but also allows them to have a better trade‐off between policy and electoral benefits under time constraints. In other words, I argue that the minister and coalition partners care not only about policy and electoral pay‐offs at a specific point in time but also the aggregated pay‐offs given the available time budget across the term.

Finally, this work speaks to the literature on agenda control in parliamentary democracies. Following the work on the temporal dimension of coalition agenda control (Döring, Reference Döring and Döring1995, Reference Döring2001), I advance the research by postulating temporal conditions under which strategic postponement represents an effective strategy for ministers to deal with coalition scrutiny. My findings suggest that when facing hostile coalition partners who trade scrutiny costs for policy gains, postponing bill initiation serves as an effective agenda‐control strategy for ministers to minimize the number of bills that will undergo scrutiny. However, an optimal strategy at a specific time point may be sub‐optimal when viewed from the whole term. By relaxing the assumption of a constant timing strategy, the results imply that rational actors may adopt quite different timing strategies when the whole time horizon is considered. Therefore, advancing the temporal perspective of coalition governance, this work reveals the conditional nature of policy timing that has been largely neglected in the previous research and helps to answer questions such as why not all highly contested proposals have been postponed (P. D. König & Wenzelburger, Reference König and Wenzelburger2017; Strobl et al., Reference Strobl, Bäck, Müller and Angelova2021).

Ministerial agenda control and strategic timing of policymaking

The property of time as both a resource and a constraint manifests itself in strategic interactions among coalition parties in legislative policymaking, where time is ‘something that could be scheduled, anticipated, delayed, accelerated, deadlined, circumvented, prolonged, deferred, compressed, parcelled out, standardized, diversified, staged, staggered, and even wasted – but never ignored’ (Schmitter & Santiso, Reference Schmitter and Santiso1998, p. 71). According to the prominent ‘portfolio allocation’ model (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1990, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996), policymaking in a specific area is ‘dictated’ by the party controlling the corresponding ministry, and thus the timing of policymaking activities should mirror independently the policy priorities of the respective ministerial parties. Accordingly, the sequence and priority of coalition policymaking crucially depend on the allocation of cabinet portfolios, which determines the informational, administrative and procedural advantages of coalition parties in different policy areas (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994). Given this policy ‘dictatorship’, a minister may reap ‘position‐taking’ benefits by proposing policies at her own ideal position at the expense of her coalition partners.

However, such potential ‘ministerial drift’ motivates coalition partners to monitor and, if necessary, challenge policymaking by the minister in order to reduce agency loss and bring policy closer to their own ideal policy positions (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). Multiple institutional arrangements, such as junior ministers (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Lipsmeyer & Pierce, Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011; Thies, Reference Thies2001), coalition agreements and procedural guidelines (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Indridason, Bräuninger and Debus2016; Indridason & Kristinsson, Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013; Klüver & Bäck, Reference Klüver and Bäck2019; Moury, Reference Moury2010, Reference Moury2013; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2003, Reference Müller, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2017), legislative committees and their chairs (Carroll & Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2019), among others, could be adopted by coalition partners to monitor and scrutinize ministerial policymaking, which also affect the timing decisions of ministers on policy initiation (Döring, Reference Döring2001; T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022; L. Martin, Reference Martin2004; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004).

Nevertheless, parliamentary institutions provide only an imperfect mechanism for coalition partners to rein in ‘drifting’ ministers (Goodhart, Reference Goodhart2013),Footnote 1 and due to commitment problems ministers may still renege on their promise (Bäck & Lindvall, Reference Bäck and Lindvall2015; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Lu, Reference Lu2023; Tavits, Reference Tavits2008; Zubek & Klüver, Reference Zubek and Klüver2013). In particular, ministers can strategically manipulate time to reduce the negative effect of coalition scrutiny on policy outcomes. For example, L. Martin (Reference Martin2004) shows that compared to contentious issues, consensual policies are more likely to be introduced earlier by ministers to garner position‐taking benefits. In a more recent study, T. König et al. (Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022) demonstrate that ministers are able to use agenda control in response to different types of coalition partners: in the face of a competitive partner who pursues her own electoral interest, the minster will delay bill initiation in order to constrain scrutiny and maximize both policy and electoral benefits.

While the existing research has provided important foundations for explaining the policymaking behaviour of ministers under coalition scrutiny, the question remains as to how ministers strategically organize their policy agendas under time constraints. In order to answer this question, we need to know not only how ministers initiate their policies at specific time points but also how the available time budget in a term influences their policymaking. In the following, I explore this question by first proposing a simple formal model formalizing strategic interactions between a minister and a coalition partner under time constraints, after which I introduce the data and estimation strategy to empirically test the hypotheses derived from the model.

Model setup

The game involves two players, namely a minister and a coalition partner, who decide, respectively, when to initiate a proposal and whether/how to scrutinize it in the term.Footnote 2 In a term spanning over a time interval

![]() $[0,T]$, the minister chooses a timing strategy

$[0,T]$, the minister chooses a timing strategy

![]() $d(t): [0,T] \rightarrow \mathbb {R}$, which specifies how she allocates proposals across the term with a maximum time budget of

$d(t): [0,T] \rightarrow \mathbb {R}$, which specifies how she allocates proposals across the term with a maximum time budget of

![]() $T$. Due to constraints such as personnel, expertise and administrative capacity in the term, there are limitations on the maximum number of proposals

$T$. Due to constraints such as personnel, expertise and administrative capacity in the term, there are limitations on the maximum number of proposals

![]() $M$ that could possibly be initiated:

$M$ that could possibly be initiated:

Since the passive adoption of ministerial proposals may imply policy loss and negative electoral consequences when voters view the compromising party as irresponsible or incompetent in defending its own policy position (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019a, Reference Fortunato2019b), coalition parties have incentives to scrutinize and amend ministerial proposals as a signal of their policy commitment to the constituency (Heller, Reference Heller2001; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005). Following the existing literature (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004), I model scrutiny by its duration

![]() $T_s$. With a likelihood of

$T_s$. With a likelihood of

![]() $p_s \in (0, 1)$, the coalition partner will scrutinize and amend the proposal, thereby curbing ‘ministerial drift’ and making the policy closer to his ideal position (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), which brings a policy pay‐off of

$p_s \in (0, 1)$, the coalition partner will scrutinize and amend the proposal, thereby curbing ‘ministerial drift’ and making the policy closer to his ideal position (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), which brings a policy pay‐off of

![]() $D = 1$ to him. When the remaining term or the available time budget is less than the minimum scrutiny duration, I expect that the proposal will not be enacted, in which case the status quo remains and it brings no additional policy gains to both the minister and the coalition partner. Because it also requires the coalition partner to invest scarce resources in scrutinizing the details of the proposal (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004), I assume that scrutiny is costly and its likelihood is a negative function of the cost

$D = 1$ to him. When the remaining term or the available time budget is less than the minimum scrutiny duration, I expect that the proposal will not be enacted, in which case the status quo remains and it brings no additional policy gains to both the minister and the coalition partner. Because it also requires the coalition partner to invest scarce resources in scrutinizing the details of the proposal (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004), I assume that scrutiny is costly and its likelihood is a negative function of the cost

![]() $C$, which can be expressed formally by

$C$, which can be expressed formally by

![]() $p_s = f(C)$ and

$p_s = f(C)$ and

![]() $\partial f(C) / \partial C< 0$. I adopt a functional form of

$\partial f(C) / \partial C< 0$. I adopt a functional form of

![]() $f(C) = \frac{1}{1 + C^2}$ with

$f(C) = \frac{1}{1 + C^2}$ with

![]() $C \in (0,D)$ which endogenize the scrutiny costs of the coalition partner into the scrutiny probability. For simplicity and without loss of generality, I set

$C \in (0,D)$ which endogenize the scrutiny costs of the coalition partner into the scrutiny probability. For simplicity and without loss of generality, I set

![]() $C = 0.8D$.

$C = 0.8D$.

Given the limitation on the number of proposals she could possibly initiate, the minister has to trade off between early initiation and postponement of proposals. While the former increases the chance of enactment of the proposals but at the same time provides the coalition partner with sufficient time and chances of scrutiny, the latter reduces both the chance of passage and the scrutiny opportunity of the coalition partner. I further expect that on average the pay‐off of the minister is higher the earlier she enacts a bill for at least two reasons. First, enacting a bill early allows the minister to benefit from the policy change and oversee its implementation to ensure it aligns with the original policy objectives. Second, the public tends to recognize and value the speedy honoring of electoral promises, which can be advantageous for the minister who enacts bills earlier.Footnote 3 Therefore, for each enacted bill, I assume that the minister receives a policy pay‐off of

![]() $B_t > 0$, which decreases over time by a discount factor of

$B_t > 0$, which decreases over time by a discount factor of

![]() $\alpha \in (0,1)$. This is also a standard assumption in modelling pay‐offs over time when political actors tend to discount the future (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975) and has been confirmed with experimental evidence (Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012). For comparability, I assume

$\alpha \in (0,1)$. This is also a standard assumption in modelling pay‐offs over time when political actors tend to discount the future (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975) and has been confirmed with experimental evidence (Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012). For comparability, I assume

![]() $B_0 = D$ at time

$B_0 = D$ at time

![]() $t = 0$.

$t = 0$.

Once the proposal is scrutinized and amended by the coalition partner, it reflects both coalition conflicts and compromised policies that are less preferred by the minister than her ideal policy position. Because voters may perceive compromise negatively, associating it with ineffective representation and tending to penalize parties they perceive as compromising (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019b; Harbridge et al., Reference Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison2014), I suppose that for each scrutinized proposal it incurs a cost

![]() $L < B_0$ for the minister due to the reputation and policy loss.Footnote 4 For simplicity and without loss of generality, I assume that the cost is half of the policy pay‐off at time

$L < B_0$ for the minister due to the reputation and policy loss.Footnote 4 For simplicity and without loss of generality, I assume that the cost is half of the policy pay‐off at time

![]() $t = 0$:

$t = 0$:

![]() $L = 0.5B_0$. However, when it comes close to the election time and when the time budget for scrutiny is limited, the minister has the opportunity to make a make‐or‐break offer to the coalition partner. In response, the coalition partner can decide either to reduce scrutiny which enacts the most preferred policy of the minister or to continue with scrutiny that risks failure of the minister to enact her policy. Thus, despite the policy risk, the minister can at least garner two types of benefits from initiating proposals late: First, she receives a position‐taking benefit by signaling her policy commitment to the constituency (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005). Second, she enjoys an electoral benefit by defaming her partner as uncooperative (Skaperdas & Grofman, Reference Skaperdas and Grofman1995; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Van der Brug and van Praag2014). I denote these benefits by a positive value

$L = 0.5B_0$. However, when it comes close to the election time and when the time budget for scrutiny is limited, the minister has the opportunity to make a make‐or‐break offer to the coalition partner. In response, the coalition partner can decide either to reduce scrutiny which enacts the most preferred policy of the minister or to continue with scrutiny that risks failure of the minister to enact her policy. Thus, despite the policy risk, the minister can at least garner two types of benefits from initiating proposals late: First, she receives a position‐taking benefit by signaling her policy commitment to the constituency (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005). Second, she enjoys an electoral benefit by defaming her partner as uncooperative (Skaperdas & Grofman, Reference Skaperdas and Grofman1995; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Van der Brug and van Praag2014). I denote these benefits by a positive value

![]() $R = 2B_0$, which is twice the value of the baseline pay‐off

$R = 2B_0$, which is twice the value of the baseline pay‐off

![]() $B_0$.

$B_0$.

Based on the above specifications, we are able to construct the full pay‐offs of the minister and the coalition partner depending on their timing and scrutiny decisions. The aggregated pay‐off of the minister in the whole term can be computed as follows:

$$\begin{equation} U_{\text{minister}} = \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T - T_s}\alpha ^td(t)B_0dt}_{\text{Policy gain}} - \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T}Lf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Scrutiny cost}} + \underbrace{\int _{t = T - T_s}^{T}Rf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Electoral benefit}}, \end{equation}$$

$$\begin{equation} U_{\text{minister}} = \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T - T_s}\alpha ^td(t)B_0dt}_{\text{Policy gain}} - \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T}Lf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Scrutiny cost}} + \underbrace{\int _{t = T - T_s}^{T}Rf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Electoral benefit}}, \end{equation}$$which consists of the policy gain, the cost from scrutiny and the electoral benefit. Similarly, we can compute the pay‐off of the coalition partner as follows:

$$\begin{equation} U_{\text{partner}} = \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T - T_s}\alpha ^tDf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Policy gain from scrutiny}} + \underbrace{\int _{t = T - T_s}^{T}Rf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Electoral benefit}}, \end{equation}$$

$$\begin{equation} U_{\text{partner}} = \underbrace{\int _{t = 0}^{T - T_s}\alpha ^tDf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Policy gain from scrutiny}} + \underbrace{\int _{t = T - T_s}^{T}Rf(C)d(t)dt}_{\text{Electoral benefit}}, \end{equation}$$where, despite the risk of policy failure, scrutiny before the election also signals the commitment of the coalition partner to his own constituency and thus also yields an electoral benefit to him (L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). For simplicity, I assume that when there is insufficient time to pass a bill, the electoral benefits for both the minister and the coalition partner are equal. Note that the scrutiny cost of the coalition partner has been endogenized into the scrutiny probability and thus is not listed as a separate component in his pay‐off. For illustrations of the pay‐offs of the minister and the coalition partner, see Supporting Information Section A.1.

Equilibrium and hypotheses

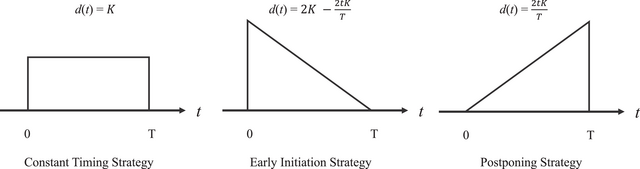

While there are infinite timing strategies the minister could possibly adopt in a term, I distinguish among three ‘ideal‐type’ strategies, which are illustrated in Figure 1. For comparability, I make sure that within the term the total numbers of bills initiated under these three strategies are the same.

Figure 1. Illustration of three ideal‐type timing strategies. A timing strategy could also be nonlinear in the sense that the minister may initiate significantly more or less bills at specific time points. Nonlinear strategies can be approximated by mixing and combining the three ideal types with varying weights over time.

In the first strategy, where

![]() $d(t) = K$, the minister evenly distributes proposals across the whole term.Footnote 5 Since this strategy does not vary over time, I call it a ‘constant timing’ strategy, which implies that time constraints have no or very limited effects on policymaking of the minister so that she does not prioritize legislative proposals at specific time points in the term. In the second strategy, where

$d(t) = K$, the minister evenly distributes proposals across the whole term.Footnote 5 Since this strategy does not vary over time, I call it a ‘constant timing’ strategy, which implies that time constraints have no or very limited effects on policymaking of the minister so that she does not prioritize legislative proposals at specific time points in the term. In the second strategy, where

![]() $d(t) = 2K - \frac{2tk}{T}$, the minister attempts to initiate proposals early on in the hope that they will be adopted before the end of the term (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004). I call this strategy an ‘early initiation’ strategy, which may bring benefits to the minister if she is able to demonstrate to the voters her competence and commitment by, for example, a high number of policy initiations or adoptions (Kovats, Reference Kovats2009). Finally, as opposed to the second strategy, in what I call a ‘postponing’ strategy, where

$d(t) = 2K - \frac{2tk}{T}$, the minister attempts to initiate proposals early on in the hope that they will be adopted before the end of the term (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004). I call this strategy an ‘early initiation’ strategy, which may bring benefits to the minister if she is able to demonstrate to the voters her competence and commitment by, for example, a high number of policy initiations or adoptions (Kovats, Reference Kovats2009). Finally, as opposed to the second strategy, in what I call a ‘postponing’ strategy, where

![]() $d(t) = \frac{2tk}{T}$, the minister tends to postpone proposals till the end of the term, and, as a result, more proposals are stacked in the late term.Footnote 6 As an example, Lagona and Padovano (Reference Lagona and Padovano2008) find that in the Italian parliament, legislative outputs can increase at the end of the term. For both the minister and the coalition partner, it can be shown that while early initiation yields the highest policy and electoral pay‐off in the early periods, the postponing strategy performs better when it is close to the end of the term (see the illustrations of the pay‐offs in Supporting Information Section A.1). However, compared to the other strategies, the postponing strategy also introduces the highest risk of policy failure due to the limited time budget when the scrutiny of the partner continues till the end of the term.

$d(t) = \frac{2tk}{T}$, the minister tends to postpone proposals till the end of the term, and, as a result, more proposals are stacked in the late term.Footnote 6 As an example, Lagona and Padovano (Reference Lagona and Padovano2008) find that in the Italian parliament, legislative outputs can increase at the end of the term. For both the minister and the coalition partner, it can be shown that while early initiation yields the highest policy and electoral pay‐off in the early periods, the postponing strategy performs better when it is close to the end of the term (see the illustrations of the pay‐offs in Supporting Information Section A.1). However, compared to the other strategies, the postponing strategy also introduces the highest risk of policy failure due to the limited time budget when the scrutiny of the partner continues till the end of the term.

Nevertheless, this is not to say that except for the three ideal‐type strategies the minister cannot adopt other strategies. For example, the postponing and early initiation strategy may also be nonlinear in the sense that the minister may initiate significantly more or less bills at the start or the end of the term. In fact, by mixing and combining the three ideal types with varying weights over time, we are able to approximate almost all types of timing strategies a minister could possibly adopt. Theoretically, I concentrate on these three ideal strategies in order to demonstrate how timing decisions of late or early initiation given the available time budget affect the pay‐offs and outcomes in the strategic policy interaction between the minister and the coalition partner.

Holding the scrutiny duration

![]() $T_s$ constant, it is straightforward to show that with an increasing time budget, the minister is more likely to initiate proposals earlier than postponing them. This is due to an increased proportion of policy gains from early initiation compared to electoral benefits from postponement for both the minister and the coalition partner. To maximize her overall pay‐off under an increased time budget, the minister is more likely to adopt an early‐initiation strategy which yields the highest policy gains. Therefore, we are able to derive the first hypothesis:

$T_s$ constant, it is straightforward to show that with an increasing time budget, the minister is more likely to initiate proposals earlier than postponing them. This is due to an increased proportion of policy gains from early initiation compared to electoral benefits from postponement for both the minister and the coalition partner. To maximize her overall pay‐off under an increased time budget, the minister is more likely to adopt an early‐initiation strategy which yields the highest policy gains. Therefore, we are able to derive the first hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1. Everything else being equal, ministers are more likely to initiate a greater number of bills early in the term the higher their time budget.

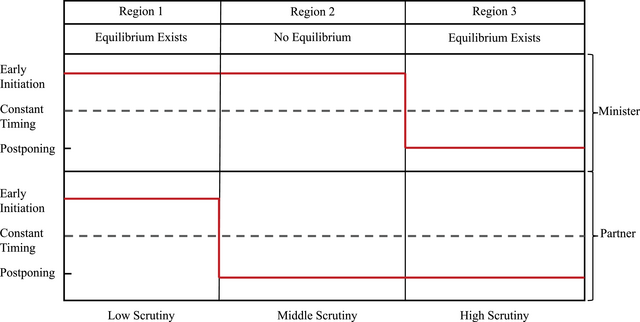

Because the strategic timing choice depends on the aggregated pay‐off of the minister which is also contingent on the scrutiny of the coalition partner, I calculate equilibrium outcomes focusing on the highest aggregated pay‐offs under different scrutiny duration. Figure 2 illustrates the equilibrium outcomes for different strategies adopted by the minister and the coalition partner.Footnote 7 I divide the strategic space into three regions according to the scrutiny duration and the timing strategies that yield the highest pay‐offs for the minister and the coalition partner.Footnote 8 The red lines in the figure represent the timing strategies that yield the highest pay‐offs for the minister and the coalition partner.

Figure 2. Illustration of equilibrium outcome. Solid red lines represent the strategies yielding the highest pay‐off in the respective regions. In Region 1, early initiation is an equilibrium strategy as it yields the highest pay‐offs for both the minister and the coalition partner and therefore both players have no incentive to deviate. In Region 3, postponement is the equilibrium strategy. In Region 2, there is no equilibrium.

First note that the constant timing strategy has never become the dominant strategy in all three regions, which suggests that, instead of doing it randomly, the minister times strategically bill initiation. In the first region (Region 1) where the scrutiny of the coalition partner is low, both the minister and the coalition partner receive the highest pay‐offs when the minister adopts the early initiation strategy. As a result, the minister is able to maximize her policy gains while catering to the preferences of the voters by initiating proposals earlier. At the same time, the coalition partner will have sufficient time to scrutinize the proposals to reduce ministerial drift. However, as illustrated in the second region (Region 2), with increasing scrutiny the early initiation strategy yields the lowest pay‐off for the coalition partner. Although the strategy is still the best choice for the minister in this situation, the coalition partner has incentives to deviate by either reducing or increasing scrutiny. In the third region (Region 3) where the scrutiny intensifies, the postponing strategy dominates. The strategy provides the minister with both the chance to signal her policy commitment to the constituency and the chance to blame the coalition partner for the policy delay. Overall, while there is no equilibrium in the second region, there exist equilibria when the coalition partner reduces scrutiny and the minister initiates proposals earlier (Region 1), and when the coalition partner increases scrutiny and the minister postpones bill initiation (Region 3).

Because at the time of initiation, the minister cannot foresee exactly how the coalition partner will scrutinize the bill, she can only form an expectation of the potential scrutiny based on the experienced scrutiny. As is clear from the comparison between Regions 1 and 3, with increasing expected scrutiny, the dominant timing strategy of the minister changes from early initiation to postponement. Thus, I expect that on average, higher scrutiny leads to the postponement of bill initiation (see also T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022).

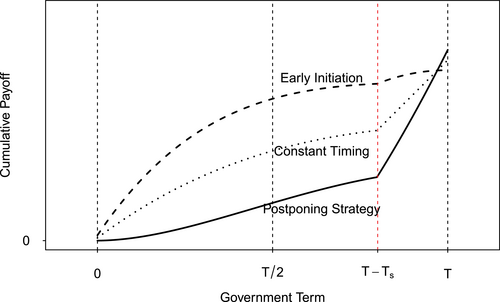

With regard to time‐varying characteristics of the equilibrium, Figure 3 illustrates the cumulative pay‐offs for the minister adopting different timing strategies. Not surprisingly, the strategy of early initiation yields the highest cumulative pay‐off for the minister during the early periods of the term, while the lowest pay‐off in the early term comes from the postponing strategy. Although the difference in cumulative pay‐offs among the three ideal‐type strategies becomes larger during the early period (

![]() $t < T/2$), it remains relatively constant in the mid‐term (

$t < T/2$), it remains relatively constant in the mid‐term (

![]() $T/2 < t < T - T_s$). When approaching the end of the term, the difference narrows. And, there exists a time point across which the postponing strategy outperforms both the constant timing and early initiation strategy. This suggests that the minister has the incentive to strategically postpone bills in later periods even though it yields a lower pay‐off in the earlier term.

$T/2 < t < T - T_s$). When approaching the end of the term, the difference narrows. And, there exists a time point across which the postponing strategy outperforms both the constant timing and early initiation strategy. This suggests that the minister has the incentive to strategically postpone bills in later periods even though it yields a lower pay‐off in the earlier term.

Figure 3. Cumulative pay‐offs of the minister over time with different timing strategies.

Furthermore, due to time‐varying pay‐offs of the minister within the term, the impact of legislative scrutiny on bill initiation may vary over time. As illustrated by the cumulative pay‐offs of the minister with different timing strategies, legislative scrutiny is likely to have greater influence in the late term. Furthermore, Figure 3 shows that the minister's choice of timing strategies differs depending on both the relative temporal location and scrutiny of the coalition partner (see also Figure 2). In earlier periods of the term, early initiation represents the best strategy for the minister when she faces high scrutiny from the coalition partner. However, in the late term, the postponing strategy may instead provide the minister with the highest pay‐off. Thus, I suppose that

-

Hypothesis 2. While scrutiny may incentivize early initiation in earlier periods of a term, ministers are more likely to postpone bill initiation in the late term when facing high scrutiny.Footnote 9

For simplicity, I do not directly specify factors in the model that may influence the scrutiny cost. Yet, it is a straightforward extension by modelling the scrutiny costs as a function of other variables, which consequently impact bill initiation. Scrutiny and its relation with timing of bill initiation may be further impacted by policy divergence between the minister and coalition partners as well as the issue of saliency under consideration. High coalition policy divergence incentivizes the ministers responsible for drafting a bill to deviate from the coalition compromise, which in turn motivates coalition partners to scrutinize and amend the ministerial proposal to reduce policy loss (Becher, Reference Becher2010; Huber, Reference Huber1996; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020; S. Martin, Reference Martin2011). This can risk legislative delay or even policy failure which may bring both electoral and policy costs to the responsible party (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021). The scrutiny efforts of coalition partners and timing decisions of ministers also vary depending on saliency attached to different policy areas (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004). Arguably, coalition partners are more likely to scrutinize highly salient bills, which motivates the minister to time strategically the initiation of those bills. In particular, ministers are less likely to postpone salient bills as the risk of policy failure and potential reputation costs are high. Therefore, I expect empirically that

-

Hypothesis 3.1. Everything else being equal, ministers postpone bill initiation with increasing coalition policy divergence.

-

Hypothesis 3.2. Everything else being equal, ministers initiate salient bills earlier than other bills.

Because of the strategic trade‐off of ministers between policy and electoral benefits in different periods of a term, I anticipate that the above effects vary depending on the available time budget. According to T. König et al. (Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022), high scrutiny combined with increasing coalition policy divergence will lead to the postponement of bill initiation. To examine whether this prediction holds under varying time constraints, I expand the game by modelling scrutiny duration as a function of coalition policy divergence. The equilibrium analysis in Supporting Information Section A.3 demonstrates a positive effect of the interaction between scrutiny and coalition policy divergence on postponement.

In Supporting Information Section A.4, I further relax the discontinuity assumption by introducing a positive likelihood

![]() $\beta \in (0,1)$ that pending bills will be adopted in the next term. The value of

$\beta \in (0,1)$ that pending bills will be adopted in the next term. The value of

![]() $\beta$ depends on factors such as the expected coalition composition and whether the minister expects her party to remain in government. A re‐analysis of the equilibrium shows that when the expected passage rate of pending bills in the next term is moderate or low, the equilibrium outcome remains similar to that of the main model.

$\beta$ depends on factors such as the expected coalition composition and whether the minister expects her party to remain in government. A re‐analysis of the equilibrium shows that when the expected passage rate of pending bills in the next term is moderate or low, the equilibrium outcome remains similar to that of the main model.

Data and measurement

I test the hypotheses against a recently published dataset on coalition policymaking in European parliamentary democracies (T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022). The dataset represents one of the most comprehensive cross‐national data on coalition legislative policymaking collected to date, which covers government bills from coalition governments available in the following countries between 1981 and 2014: Belgium (1988–2010), Czech Republic (1993–2013), Denmark (1985–2011), Estonia (2007–2011), Finland (1989–2010), Germany (1981–2012), Hungary (1998–2014), Latvia (2002–2011), Norway (1989–2013) and Poland (1997–2011).Footnote 10 These countries have all been governed by coalition parties but vary in their historical, cultural, economic, demographic and institutional settings, which allow for examining both the commonalities and variation among different coalition governments. The unit of analysis is individual governmental bill proposals introduced in the lower house of the respective parliaments, and the corresponding minister and policy area of each bill are identified via legal documents available in respective online parliamentary databases.

Following Woldendorp et al. (Reference Woldendorp, Keman and Budge2000), a new term in the data is commenced by any change in the composition of the coalition government (either by a change in party composition or prime minister) (see also Seki & Williams, Reference Seki and Williams2014). Since the duration of terms differs across countries and over time, I introduce a measure of timing by calculating the relative temporal locations of bills within each term. As a result, the dependent variable ranges from the 0th percentile to the 100th percentile, corresponding to the dates between the first and last days of a term. For example, in a term with 1000 days, a bill initiated 250 days after the government formation is located at the 25th percentile (250/1000) of the term. To account for the cyclical nature of bill initiation, I further transfer the above measure into a radius measure between

![]() $-\pi$ and

$-\pi$ and

![]() $\pi$, that is, via a one‐to‐one map from

$\pi$, that is, via a one‐to‐one map from

![]() $[0 \text{per cent},100 \text{per cent}]$ to

$[0 \text{per cent},100 \text{per cent}]$ to

![]() $[-\pi,\pi]$.

$[-\pi,\pi]$.

The available time budget and expected scrutiny are two of the main explanatory variables of the analysis. To measure the available time budget, I calculate for each proposal the number of months remaining in the term. I measure the expected scrutiny for each proposal in a particular ministerial portfolio by the experienced scrutiny duration of the previous bills of the same area in the same term. This measure is built on L. Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2004) who approximate scrutiny by the duration of legislative bills from initiation to adoption (see also T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022). To avoid extrapolation and extreme values that could potentially bias the results and to ensure comparability across countries, I further dichotomize the variable by identifying high experienced scrutiny when the scrutiny duration is higher than the median value of all bills in the same term.

I introduce a measure of coalition policy divergence by calculating the divergence of policy‐specific positions among coalition parties (T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022). Specifically, I draw on the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data on parliamentary parties since 1945 (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Theres, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019) and adopt the scaling approach of Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) to calculate partisan positions of 13 ministerial portfolios (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011).Footnote 11 The resulting measure is a sum of policy‐specific positional differences between the ministerial party and her coalition partners.Footnote 12

Finally, I measure saliency of bills in each policy area by counting the number of times a specific policy category was mentioned in a given party's manifesto from the CMP data (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Theres, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019). This measure is then log‐transformed to eliminate extreme values (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011).

I also control for a set of variables that are suspected to influence both the dependent and the explanatory variables. First, because the relative strength of the minister against coalition partners impacts both the effectiveness of ministerial agenda control with strategic timing and the capacity of coalition partners to scrutinize bills (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004), I control for the minister's party size measured by the percentage of seat share in the parliament. Second, policy conflict among opposition parties may inhibit them from presenting a meaningful challenge to the governing coalition (T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022). This provides not only greater space for the partners to scrutinize bills but also enhanced flexibility for the minister to decide the time of bill initiation. Therefore, I include the policy divergence of the opposition parties as a control. Third, according to the model, the duration of terms influences the aggregated pay‐offs of both the minister and the coalition partner who make their timing and scrutiny decisions based on the available time budget. Due to the variation of terms across countries and over time, I control for the duration of respective terms. Fourth, minority coalitions have to ensure support of some pivotal opposition parties (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990), which influence the timing strategy of the minister. The minority status may also restrict the capacity of the coalition partner to scrutinize bills. Accordingly, I control for whether the coalition is a minority. Finally, the legislative median may play an influential role in policymaking (Black, Reference Black1948; Laver & Schofield, Reference Laver and Schofield1990; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014). When the opposition parties control the median, it imposes greater constraints on intra‐coalition policymaking regarding both scrutiny and policy timing. Thus, I consider in the model whether the opposition parties take the median position of the parliament. Note that due to varying institutional features and electoral environments, there may exist heterogeneous effects on timing. Therefore, I additionally control for country‐specific effects and demonstrate country‐specific distributions of bills over time. For an overview of the summary statistics of the variables included in the analysis, see Supporting Information Section B.

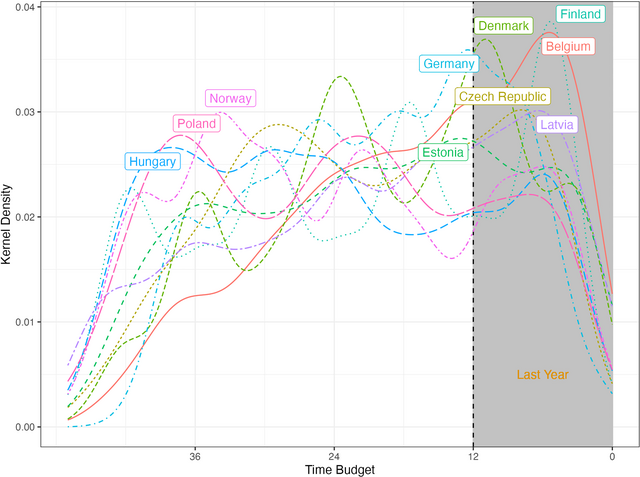

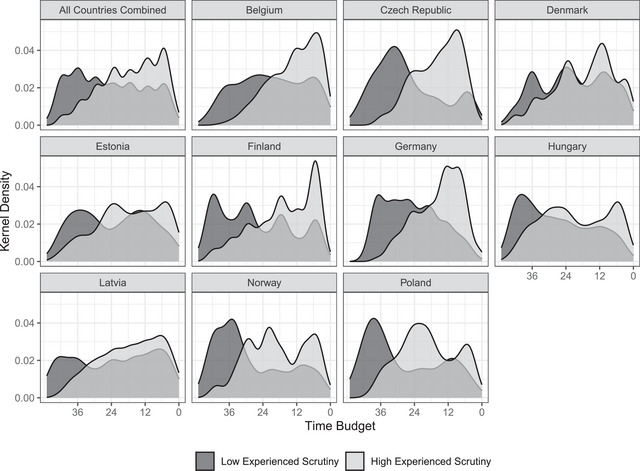

Figure 4 illustrates the distributions of bill proposals with a decreasing time budget. While there is considerable variation among countries, we can clearly discern a pattern in which, except for Hungary, Poland and Norway, most countries have the highest concentration of bill proposals in the last year of the term.

Figure 4. Distributions of bill proposals with a decreasing time budget. Country labels are placed at time points with the highest concentration of bill proposals in the respective countries.

Some preliminary exploratory analysis already lends support to my argument for the adoption of the postponing strategy. Figure 5 depicts the distributions under low and high experienced scrutiny. It is apparent from the country‐specific distributions as well as the overall pattern that compared to the situation with low experienced scrutiny, ministers on average tend to postpone proposals when the experienced scrutiny is high.

Figure 5. Distributions of bill proposals under low and high experienced scrutiny. Proposals under high experienced scrutiny are those experiencing scrutiny duration of past bills larger than the median scrutiny duration within a term. Otherwise, I identify them as under low experienced scrutiny.

Analysis and results

Because the timing data of legislative policymaking is periodic in nature due to recurring legislative cycles, the commonly used linear model may generate bias in estimation. To reduce bias and account for the cyclicity of the legislative data, I use circular regression,Footnote 13 whose essential model specification takes the following form:

where

![]() $\mu _0$ is the circular intercept,

$\mu _0$ is the circular intercept,

![]() $g^{-1}(\cdot)$ is a transformation function taking the form of

$g^{-1}(\cdot)$ is a transformation function taking the form of

![]() $2\text{arctan}(\cdot)$,

$2\text{arctan}(\cdot)$,

![]() $\bm{X}$ includes a set of explanatory and control variables,

$\bm{X}$ includes a set of explanatory and control variables,

![]() $\bm{\beta }$ represents the associated coefficients and

$\bm{\beta }$ represents the associated coefficients and

![]() $\varepsilon$ is an error term.

$\varepsilon$ is an error term.

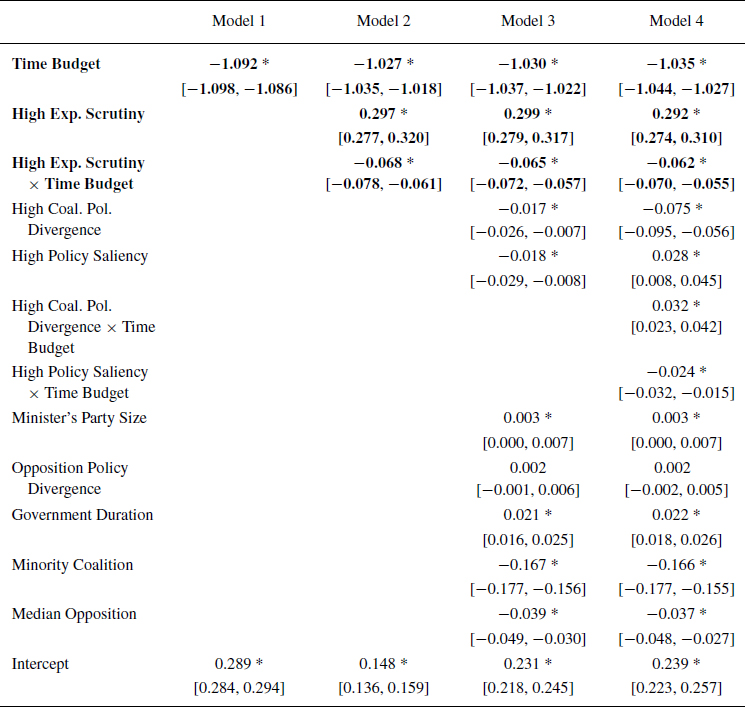

Table 1 presents the main estimation results, which show the effect of each variable on the timing of bill initiation. The positive estimates indicate postponement of bill initiation, while the negative values imply early initiation.Footnote 14 The 95 per cent credible intervals for coefficient estimates are included in brackets in the table. To test the respective hypotheses, I present different specifications: Model 1 includes a single explanatory variable of time budget to test the general prediction of the relation between time constraints and timing of bill initiation. Model 2 adds the variable measuring experienced scrutiny and interacts the variable with the available time budget. Model 3 further controls for coalition policy divergence and policy saliency, among other variables. Finally, in Model 4, the variables of coalition policy divergence and policy saliency are additionally interacted with the available time budget.

Table 1. The effects of experienced scrutiny, coalition policy divergence and powerful ministers on timing of bill initiation (positive coefficients indicate postponement and the values given in bold are the estimates of the main explanatory variables and their interaction term for the first two hypotheses)

Dependent variable: Temporal location of bills within a term. N: 23,936

Lower and upper bounds of 95 per cent credible intervals in brackets.

The asterisk * denotes an estimate whose 95 per cent credible interval does not overlap zero.

According to Hypothesis 1, I expect that an increased time budget is likely to accelerate bill initiation. This expectation is empirically supported by the negative effect of the available time budget in Model 1. In Hypothesis 2, I further argue that the effect of scrutiny on timing of bill initiation varies within a term. In particular, I expect a higher postponing effect with a reduced time budget. This hypothesis is supported by the significant negative interaction effect between the high experienced scrutiny and the available time budget in Model 2.Footnote 15

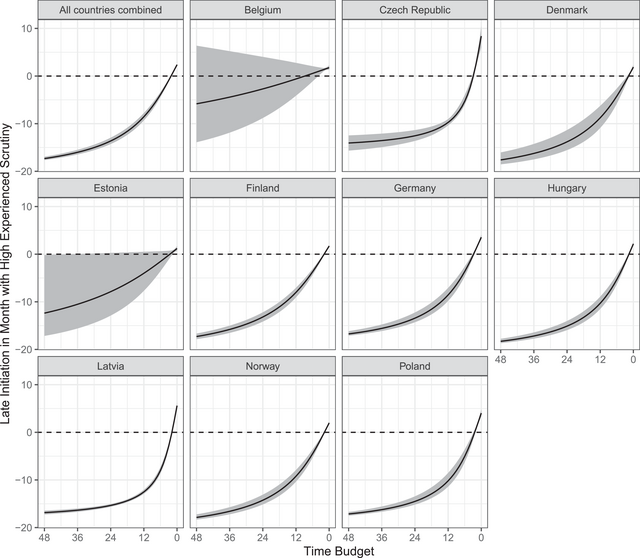

The substantive effects of high experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation are depicted in Figure 6, which illustrates both the aggregated and country‐specific effects. On average, when there are fewer than 6 months remaining in the term, ministers tend to delay bill initiation when experiencing high scrutiny; the concrete effects, however, vary across countries. For example, the effects are substantively insignificant in Belgium and Estonia, compared to other countries. We can find the most significant postponing effects in the late term in the Czech Republic and Latvia.

Figure 6. Predicted timing of bill initiation with high experienced scrutiny and a decreasing time budget. The values below zero indicate early initiation while those above zero indicate postponement. The predictions of bill initiation are first calculated by days and then transformed into months for better comprehension. For bill initiation in the Czech Republic, I control for whether a bill was proposed in the last year of a term to account for the unbalanced distribution of the bills.

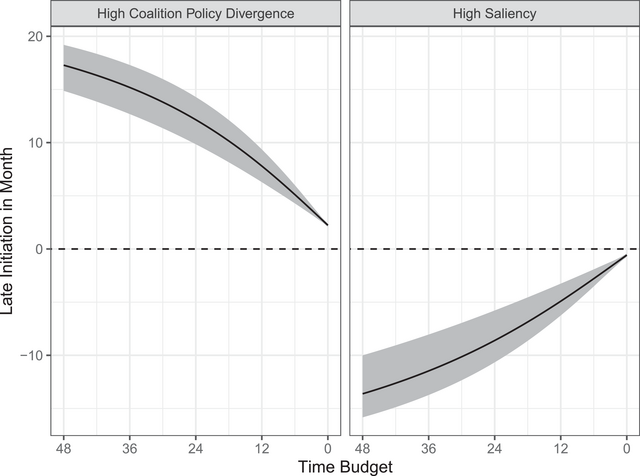

The above variation may be explained by the varying preference configurations among coalition parties (Hypothesis 3.1), and saliency of the bills that were proposed (Hypothesis 3.2). Therefore, in Model 3, I further control for high coalition policy divergence and bills of high policy saliency, among other variables.Footnote 16 Both effects are significantly negative, suggesting that when coalition policy divergence and policy saliency are high, ministers tend to accelerate bill initiation, everything else being equal. I suspect that both effects vary within a term and therefore further interact the two variables with the available time budget in Model 4. As shown by the positive interaction effect between high coalition policy divergence and time budget, and the negative interaction effect between high policy saliency and time budget, the effect of coalition policy divergence on late bill initiation tends to decrease over time while the opposite is true for policy saliency.

I plot the substantive effects in Figure 7. As shown in the left panel of the figure, when there is a large time budget (when there are about 48 months remaining in the term), high coalition policy divergence leads to an average of 17 months postponement in bill initiation. However, when the time budget shrinks, the duration of postponement will be reduced to almost zero. The right panel of the figure further illustrates that compared to a less salient bill, a highly salient bill on average leads to an early initiation of around 10 months at the beginning of the term. However, at the end of the term, the effect of high policy saliency decreases to almost zero. Both effects suggest that when the time budget is limited, ministers will be more concerned about electoral benefits than the possible policy gains from the passage of the proposed bills.

Figure 7. Substantive effects of high coalition policy divergence and high saliency on timing of bill initiation with a decreasing time budget. The predictions of bill initiation are first calculated by days and then transformed into months for better comprehension.

To demonstrate the robustness of the findings, I conduct a sensitivity analysis to account for the uncertainty ministers face at the beginning of a term when few bills have been adopted and thus there is little to learn from the experienced scrutiny. The result in Supporting Information Section D.3 shows that while the main effects decrease with increasing uncertainty at the beginning of a term, the main findings remain even by introducing fairly large uncertainty. By ‘exogenizing’ measures of high coalition policy divergence and high policy saliency with respect to high experienced scrutiny,Footnote 17 and adding an interaction between policy divergence and saliency, the main estimates still remain robust (see Supporting Information Section D.4).

I further control for the impact of expected government status in the model estimation using the real government configuration as an approximation, that is, (1) whether the minister's party is still in office and (2) the share of incumbent parties in the following government. While the main findings still hold, the result in Supporting Information Section D.5 shows that when the minister's party expects itself to be in office or to have a similar coalition configuration in the next term, it is more likely to initiate bills earlier than postponing them. However, when the minister has experienced high scrutiny from the coalition partners, the expectation that her party will still be in office in the next term will lead to postponement of bill initiation. This may help to reduce the scrutiny cost and increase the policy benefit when the minister's party can re‐introduce the bills in the face of more cooperative coalition partners in the next term.

To address potential omitted variable bias, I adopt some additional model specifications and demonstrate that the main empirical findings are robust against unobserved confounding variables. For instance, the complexity of a bill, which varies across different policy areas, may impact both the timing of its initiation and the duration of scrutiny. In other words, bills that are expected to be highly scrutinized may be proposed later due to complexity rather than scrutiny. Also, the relationship between scrutiny and bill initiation can be confounded by institutional provisions and legislative traditions of different countries. Therefore, I include country‐ and policy‐fixed effects in the full model specification to further account for these potential confounders. Due to possible interpretation and identification problems of two‐way fixed‐effects models (Kropko & Kubinec, Reference Kropko and Kubinec2020), I also estimate one‐way country‐policy‐fixed effects. As shown in Supporting Information Section D.6, the original findings remain the same.

Conclusion and discussion

While the ministerial jurisdictional system partially overcomes the policy stability problem featured by indeterminacy and inconsistency of policy outcomes from majority voting in multidimensional policy space (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1994; McKelvey, Reference McKelvey1976; Schofield, Reference Schofield1983), policies that can be possibly made through ministerial ‘monopoly’ have oftentimes been criticized as suboptimal (Thies, Reference Thies2001, pp. 583–585), and sometimes even unrealistic in the presence of strong institutional controls by coalition partners (L. Martin, Reference Martin2004; L. Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020; Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Smith2010). In this article, I introduce a theoretical model to study the temporal dimension of ministerial agenda control in coalition governance and analyse the variation in timing of bill initiation under time constraints. I argue that strategic timing constitutes one of the most important agenda control mechanisms, which is not only an ad hoc response to the type of coalition partners the minister learned during the policymaking process (T. König et al., Reference König, Lin, Lu, Silva, Yordanova and Zudenkova2022) but is also contingent on the available time budget and policy priorities viewed from the whole term. The theoretical analysis and empirical results suggest that ministers strategically manipulate the timing of bill initiation in order to achieve favourable outcomes that trade off policy for electoral benefits. However, timing strategies of ministers can vary at different points in time; with the approaching of the next election, ministers are more likely to strategically postpone bill initiation. Thereby, it provides ministers with a credible threatening tool vis‐à‐vis coalition partners who attempt to scrutinize the ministerial bills for both policy and electoral gains.

This article also challenges the common wisdom that the introduction of time limits for legislation will always speed up the legislative process and avoid forever pending bills (Van Schagen, Reference Van Schagen1997). Instead, I demonstrate that under certain conditions this time pressure, along with electoral incentives in the upcoming election, generates strategic motivations for parties within coalition governments to postpone their proposals. In addition to credit‐claiming, ministerial parties tend to adopt a postponing strategy to signal their policy commitment, while blaming their partners for policy delay.

Besides the strategic perspective of policy timing emphasized in this article, other reasons for the delayed introduction and the successful conclusion of legislative projects cannot be discounted. First, there might be closed‐door negotiations that have been carried out between the coalition partners, and bill initiation is postponed until a consensus has been reached (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Bergman and Müller2023). Consequently, successful passage of a bill towards the end of a government term can be attributed to an extensive process of bargaining and consensus finding.Footnote 18 Second, successful conclusion of legislative processes that commenced late in the term might be a result of logrolling among coalition parties (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Bergman and Müller2023; Carrubba & Volden, Reference Carrubba and Volden2000; De Marchi & Laver, Reference De Marchi and Laver2020, Reference De Marchi and Laver2023). While political policy experts are normally adept at and quick in finding what they consider problematic in a proposal, reaching a compromise is a time‐consuming process. In contrast, logrolling can be achieved in a much shorter time, making it a preferred approach as the term nears its end. Third, the pool and timing of legislative projects may also be influenced by new demands and challenges. Urgent issues like COVID‐19 or economic crises in Europe necessitate immediate government action, even with limited time remaining in the legislative calendar. Finally, policies initiated by ministers may vary in terms of precision, controversy, saliency and development stage, all of which can impact the timing of their initiation. For instance, it is reasonable to assume that highly ambiguous policies taking the form of merely agreed goals and non‐controversial policies with low saliency are more likely to be postponed.

This study leaves several avenues for future research. First, I suspect that the variation in the distribution of proposals at the end of the term may be due to both shifted resources to elections and uncertainty about the election dates which were not prefixed (Kayser, Reference Kayser2005; Lupia & Strøm, Reference Lupia and Strøm1995). Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate whether and how governing coalitions manipulate the election time to expand or reduce the time budget, and how this manipulation impacts policymaking among coalition partners.

Time pressure may not only change the proposing behaviour of the coalition parties but also the content and quality of the proposals. To reduce policy costs and enhance electoral chances, ministerial parties may impose self‐constraints on bill contents and propose consensual or trivial bills that have little impact on the actual policy change (Manow & Burkhart, Reference Manow and Burkhart2007). This may lead to ‘garbage time’ at the end of a government term despite a high initiation rate, and thus compromise the policymaking quality. Research in this respective will advance our understanding of the relation between the quality and time horizon of democratic policymaking.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2023 ECPR General Conference. For their helpful comments and suggestions, I thank the EJPR editorial team, anonymous reviewers, and the participants of the panel ‘Executive‐Legislative Relations’ at the 2023 ECPR General Conference.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: