Infants with CHD often face challenges in developing oral feeding, Reference McKean, Kasparian, Batra, Sholler, Winlaw and Dalby-Payne1 with feeding problems particularly common in critical congenital heart disease (CHD; i.e., requiring surgery <1 year of age). Approximately 44% of infants undergoing neonatal surgery for CHD do not meet expectations for oral feeding volume by hospital discharge and require feeding tube support at home. Reference Alten, Rhodes and Tabbutt2 Feeding challenges contribute to suboptimal direct breastfeeding prevalence in this population, with rates as low as 3.2% (exclusive) at 6 months. Reference Elgersma, Spatz and Fulkerson3 Emerging evidence demonstrates that human milk may be a “life-saving intervention” Reference Davis and Spatz4 for infants with CHD due to lowered risk for necrotising enterocolitis Reference Elgersma, McKechnie and Schorr5 – a devastating disease with 19–26% mortality in CHD. Reference Kelleher, McMahon and James6 Providing human milk via direct breastfeeding reduces early human milk weaning in term and preterm infants, Reference Pang, Bernard and Thavamani7,Reference Pinchevski-Kadir, Shust-Barequet and Zajicek8 allows greater cardiorespiratory stability while feeding, Reference Marino, O’Brien and LoRe9 offers personalised immunological benefits, Reference Patel, Johnson and Meier10–Reference Fernández, Langa, Martín, Jiménez, Martín and Rodríguez12 and is preferred by most birthing persons. Reference Wagner, Chantry, Dewey and Nommsen-Rivers13 Furthermore, emerging research with very low birth weight infants has demonstrated that early direct breastfeeding is associated with quicker attainment of full oral feeding, Reference Suberi, Morag, Strauss and Geva14 potentially due to the infant-driven Reference Thomas, Goodman, Jacob and Grabher15,Reference Wellington and Perlman16 nature of direct breastfeeding experiences.

Lactating parents of hospitalised infants face barriers to direct breastfeeding. Reference Carpay, Kakaroukas, D. Embleton and van Elburg17 Experiences of direct breastfeeding for other vulnerable infants have been described; Reference Demirci, Caplan, Brozanski and Bogen18–Reference Palmquist, Holdren and Fair20 however, infants with critical CHD encounter unique challenges (e.g., volume restriction; lengthy fortification; historic breastfeeding discouragement) that may not be captured by this evidence. The only report focused on parents’ experiences breastfeeding infants with CHD is a 1998 informal survey Reference Lambert and Watters21 including both critical and non-critical diagnoses. No studies examining the process of directly breastfeeding infants with critical CHD, from lactating parents’ perspectives, have been found. An understanding of this process is imperative, as there is no standard for evidence-based direct breastfeeding care in this population and substantial provider- and site-specific variation in feeding practice exists. Reference Tume, Balmaks, da Cruz, Latten, Verbruggen and Valla22,Reference Elgersma, McKechnie, Gallagher, Trebilcock, Pridham and Spatz23

Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine how lactating parents establish direct breastfeeding with an infant hospitalised for critical CHD. Improved understanding of this process may provide a theoretical foundation for interventions to improve the low rates of direct breastfeeding in this population.

Materials and Methods

A grounded dimensional analysis approach Reference Bowers, Schatzman, Morse, Stern, Corbin, Bowers, Charmaz and Clarke24–Reference Schatzman and Maines26 guided our inquiry into “what all is involved” Reference Schatzman and Maines26 in the process of establishing direct breastfeeding, from lactating parents’ perspectives.

Definitions

For simplicity, we will refer to direct breastfeeding as “breastfeeding,” defined as human milk via a latch at the breast. We acknowledge that direct breastfeeding is not the only way to breastfeed Reference Elgersma and Sommerness27 and that individuals may prefer other terms (i.e., chestfeeding). We will often refer to participants as “parents,” as not all identified as women/mothers.

Recruitment

Recruitment began in July 2021 with purposive sampling through a private social media group dedicated to breastfeeding children with CHD and an online CHD parent advocacy group, with administrator approvals. Eligibility criteria included parents of infants hospitalised postnatally for critical CHD who directly breastfed in any amount within the past three years, Reference Li, Scanlon and Serdula28 were ≥18, could read English, lived in the United States (U.S.), and had internet access. Individuals were excluded if the child died within two weeks postnatally. An online screening form confirmed eligibility and directed participants to a full description of the study. Interested participants completed informed written eConsent via REDCap. Reference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde29 High interest required us to pause recruitment after a few hours, with further purposive and snowball theoretical sampling as the study progressed.

Data collection and analysis

After consent, participants completed an online survey to collect demographics and basic feeding information (Supplementary File S1). This survey was followed by a face-to-face interview (45–120 minutes), conducted from July to November 2021 by the first author via video conference (i.e., Zoom). Participants received a $50 gift card.

Consistent with the grounded dimensional analysis approach, Reference Bowers, Schatzman, Morse, Stern, Corbin, Bowers, Charmaz and Clarke24,Reference Caron, Bowers, Rodgers and Knafl25 an initial unstructured interview guide evolved into a semi-structured format based on emerging salient concepts (Supplementary File S2), facilitating constant comparison of concepts. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., Release 1.6) for immediate analysis, with K.M.E. or N.M.S. verifying accuracy.

To explain the core process, analysis involved dimensionalising through open, axial, and selective coding Reference Bowers, Schatzman, Morse, Stern, Corbin, Bowers, Charmaz and Clarke24,Reference Caron, Bowers, Rodgers and Knafl25 using MaxQDA 2020 (VERBI Software, 2019). Two researchers independently coded interviews. Initial open coding often employed in vivo labels like “standing my ground” or “asking everyone I met.” Axial coding supported preliminary organisation of higher-order concepts and relationships. For example, the previously listed codes were grouped into the higher-order concept, “advocating.” Selective coding elaborated on patterns related to the core process while seeking out variation. Explanatory matrices Reference Caron, Bowers, Rodgers and Knafl25 were created to identify relationships between salient concepts. Analysis continued through theoretical saturation. Reference Strauss30

Study rigour was realised through multiple strategies. The research team had varied expertise (i.e., certified nurse-midwife, paediatric physical therapist, neonatal ICU nurse, critical CHD researchers). The first author has experiential perspective as a parent of an infant with critical CHD, which facilitated rapport with participants and allowed for a nuanced analysis of parents’ experiences. To mitigate potential bias and encourage alternative analytical perspectives, the full team met weekly for discussion and peer review. A transparent audit trail of memos and reflexive journals documented key decisions. Member checking was continuous, with later interviewees asked to reflect on concept salience.

Results

Participants

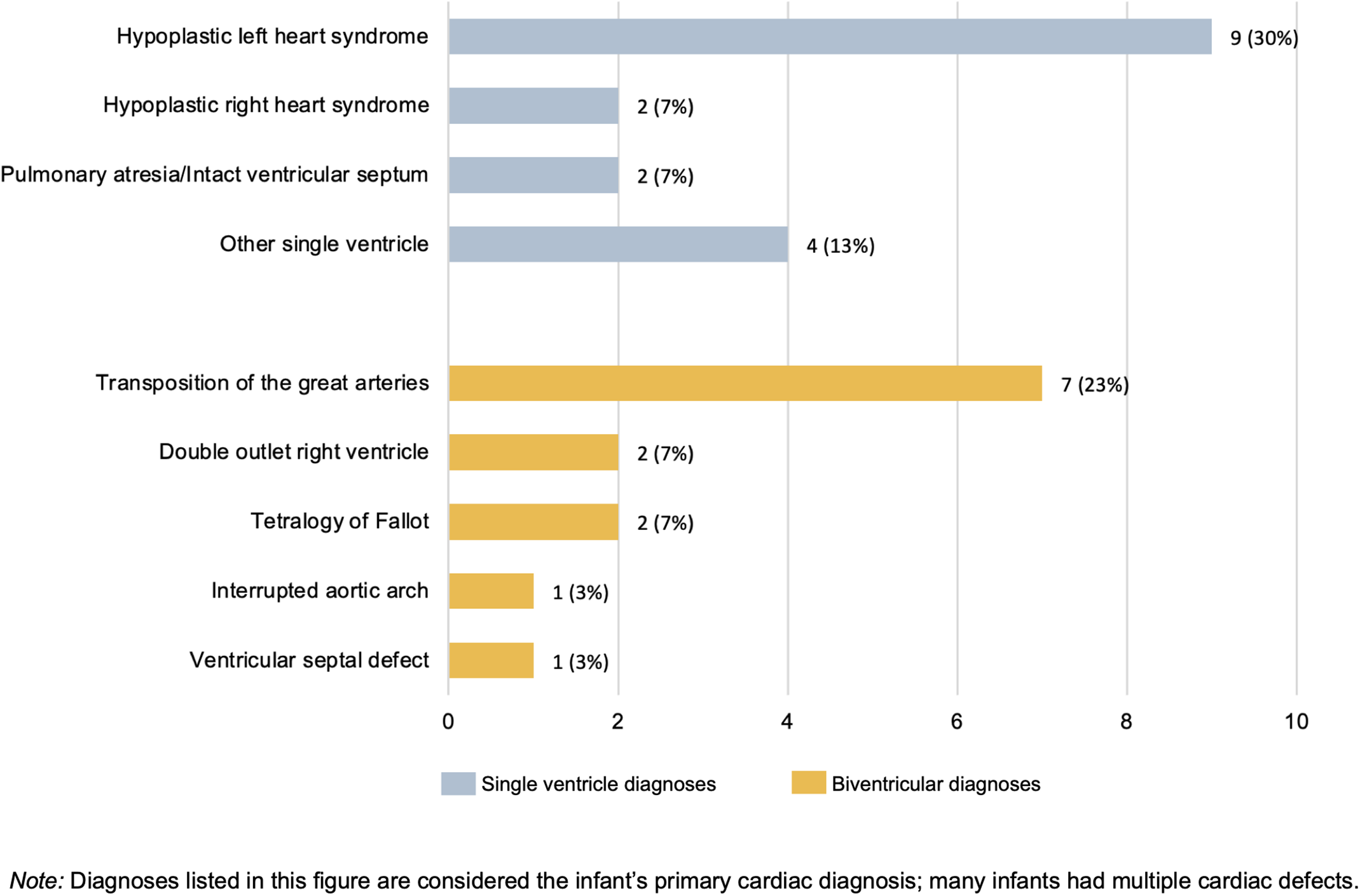

The sample included 30 parents representing 26 hospitals in 20 states. Sample characteristics can be found in Table 1. Primary critical CHD diagnoses are in Figure 1, with a majority single ventricle physiology (n = 17, 57%) Additional anomalies/syndromes were diagnosed in 27% of infants.

Figure 1. Primary cardiac diagnoses of participants’ infants (N = 30).

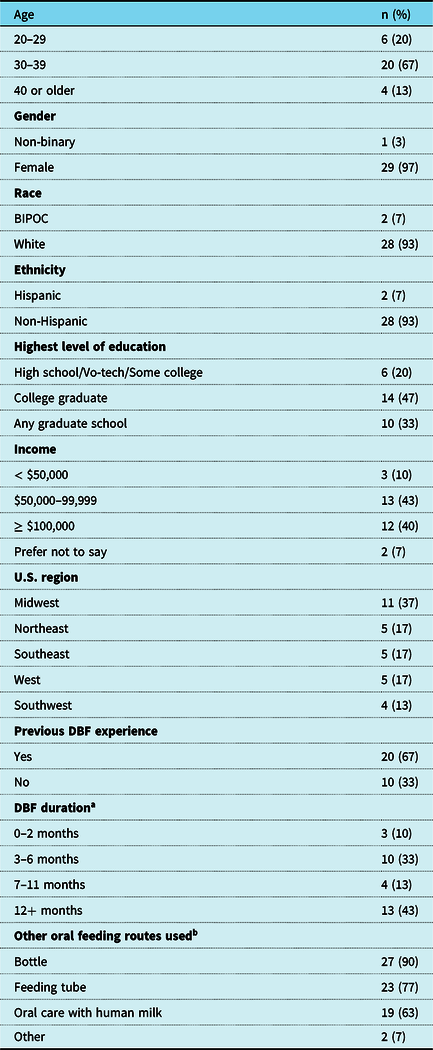

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 30).

Abbreviations: BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and people of colour; DBF = Direct breastfeeding; U.S. = United States; Vo-tech = Vocational or technical school.

a n = 10 currently directly breastfeeding

b At any time during the infant’s life

Wayfinding through the “ocean of the great unknown”

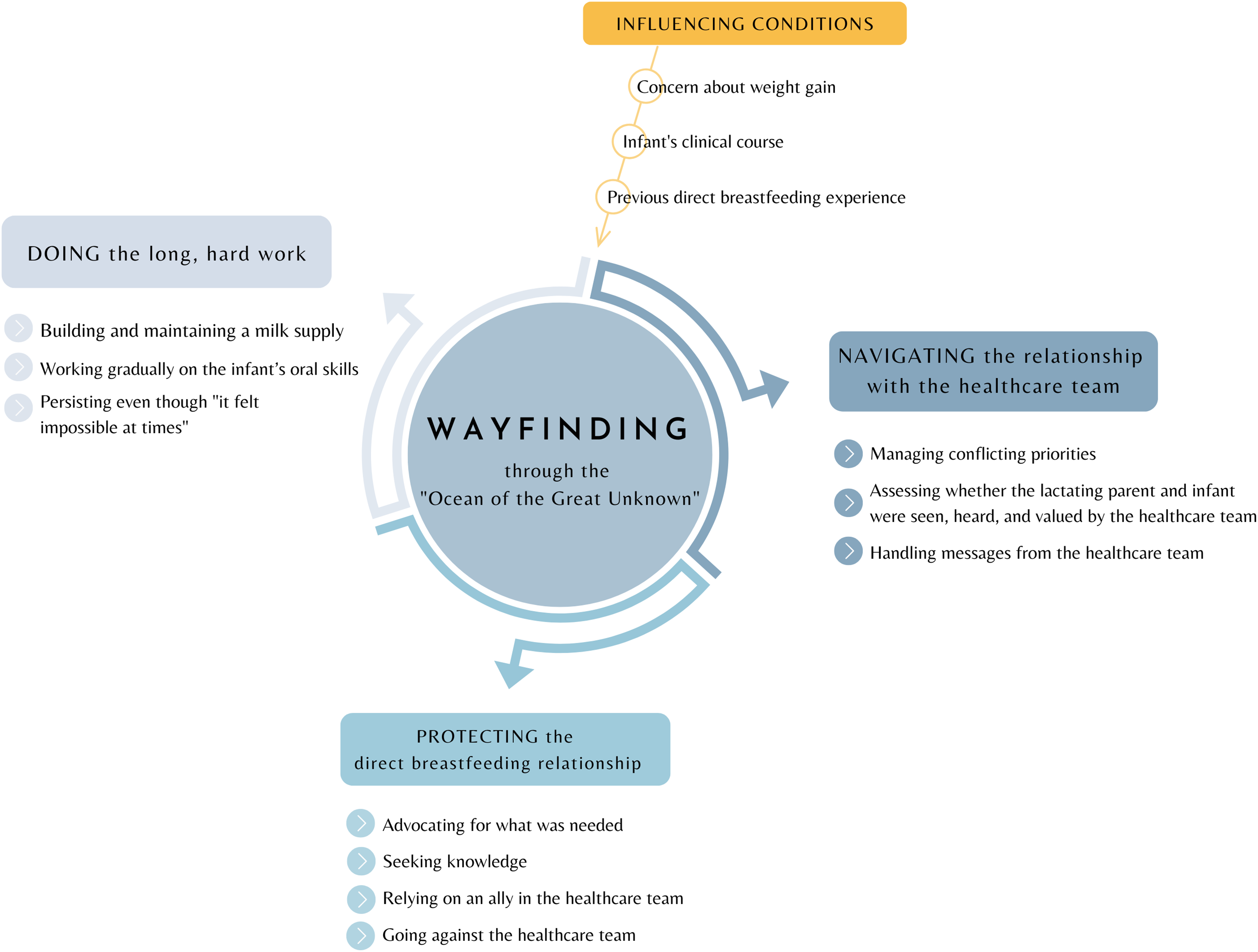

The core process of establishing direct breastfeeding with an infant hospitalised for critical CHD was one of Wayfinding through the “ocean of the great unknown” (04), with the conceptual model in Figure 2. Example quotations can be found in Table 2.

Figure 2. The conceptual model, “Wayfinding through the ‘ocean of the great unknown’,” explains how lactating parents establish a direct breastfeeding relationship with an infant with critical congenital heart disease.

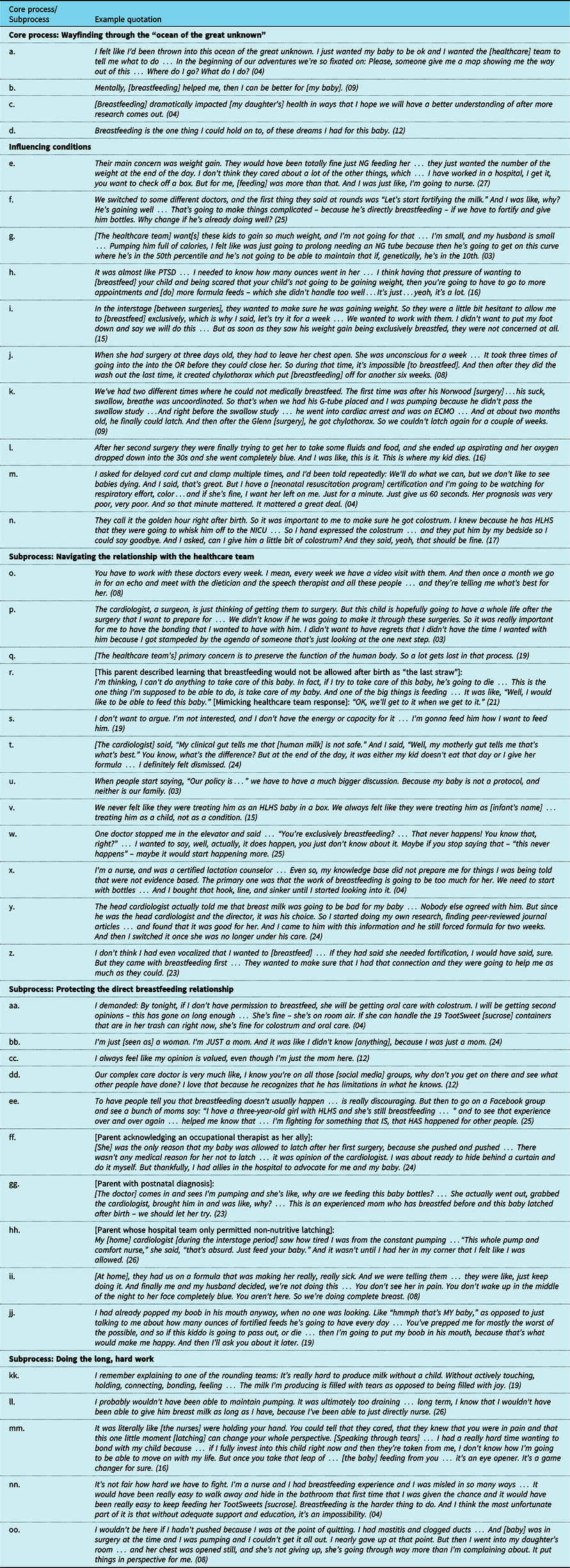

Table 2. Example quotations describing the core process, subprocesses, and influencing conditions of “Wayfinding through the ‘ocean of the great unknown’."

Abbreviations: ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; G-tube = gastrostomy tube; HLHS = hypoplastic left heart syndrome; NG = nasogastric; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit; OR = operating room; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Wayfinding was a nonlinear process requiring immense persistence as parents became navigators of an unfamiliar journey conducted in a context of life-and-death consequences for the infant (Table 2.a). Parents continually observed, assessed, and course-corrected to determine the best path. Wayfinding was an active endeavour involving three core subprocesses: navigating the relationship with the healthcare team; protecting the direct breastfeeding relationship; and doing the long, hard work. These core subprocesses were impacted by three primary influencing conditions: concern about weight gain, the infant’s clinical course, and the parent’s previous breastfeeding experience.

The core subprocesses of Wayfinding were related and could occur concurrently. For example, when parents experienced feeding-related obstacles in navigating the relationship with the healthcare team, the need to protect the breastfeeding relationship was heightened. Engagement in these protective processes facilitated the work of breastfeeding, but sometimes strained the relationship with the healthcare team.

The primary consequence of Wayfinding was breastfeeding establishment. This establishment could result in positive consequences (e.g., pride) because of the parent’s perception of providing their infant with the best chance for optimal health. Some parents described mental health benefits (Table 2.b) or positive consequences for the infant’s physical health (e.g., weight gain, lack of illness, improved cardiorespiratory stability; Table 2.c). Nearly all parents described breastfeeding as allowing them to fulfil an important aspect of the relationship they had envisioned with their infant (Table 2.d).

Influencing conditions

Three primary influencing conditions impacted the Wayfinding process: concern about weight gain, the infant’s clinical course, and previous breastfeeding experience. Concern about weight gain was ubiquitous, with many parents describing a single-minded healthcare team focus “all about the numbers” (02) both in the hospital and after discharge (Table 2.e). This concern about weight informed feeding protocols that often interfered with direct breastfeeding (Table 2.f) due to the healthcare team’s perceived need to be, as one parent explained, “very specific and controlling on exactly how much [the infant] was getting in” (11).

At times, parents viewed this concern about weight gain as limited, unrealistic, or illegitimate (Table 2.g). Many parents described “fear and worry and chaos” (04) related to their infant’s weight, with one parent explaining, “that fear … it was kind of instilled from them … placed by the doctors being so concerned with how much he was getting” (11). Some parents became “obsessed” (30) with their infant’s weight gain and found that the intense focus on weight could negatively impact their mental health (Table 2.h) or cause tension between the parent and the healthcare team. One parent described frustration that the healthcare team would not honour her request to fortify her child’s feedings with the high-fat cream from her own expressed milk: “They’re like, no, there’s no way for us to know how many calories [there are]. It’s all very scientific for them” (08). In contrast, some healthcare teams allowed for more experimentation and flexibility in assessing the infant’s weight status, which positively impacted the Wayfinding process (Table 2.i).

This concern about weight gain was sometimes related to the infant’s clinical course. Infants with the same CHD diagnosis often have vastly different trajectories, and the clinical course was unpredictable in our sample. A few parents described feeling “lucky, because she has some pretty heavy diagnoses” (26). For one parent, this smooth clinical course was perceived to facilitate the Wayfinding process: “I was blessed when he was born. He did not need any direct intervention … I was able to establish a direct breastfeeding relationship with him right away” (06).

More commonly, parents reported a wide range of challenges related to clinical course that interfered with breastfeeding establishment and necessitated increased engagement in Wayfinding processes (Table 2.j & 2.k). Parents described experiences with cardiac arrest, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ventricular assist devices, heart transplants, emergency reoperation, chylothorax, paralysed vocal chords, failed swallow studies, hypoxic events requiring lengthy intubation, necrotising enterocolitis, intestinal malrotation, diaphragmatic paresis, reflux, hospital-acquired infection, hypotonia, genetic syndromes, and tongue ties. While many of these health challenges were life-threatening (Table 2.l), their impact on breastfeeding establishment varied. One parent whose infant was immediately intubated for several weeks after birth and developed post-surgical chylothorax reported that her infant latched perfectly at 7 weeks old. In contrast, another parent explained that “by the time he really got [breastfeeding], he was like a year old” (30).

Some parents reported that the healthcare team’s prenatal perception of the severity of the infant’s clinical course impacted their willingness to support the Wayfinding process at birth, which could conflict with parents’ priorities for establishing a relationship with their new child (Table 2.m). Other institutions worked within the constraints of the clinical course to assist parents in initiating processes to facilitate breastfeeding establishment (Table 2.n).

The parent’s previous breastfeeding experience also played a role, with one parent acknowledging that “having that previous experience … gave me the confidence to know that we could do it” (26). Others did not feel that previous experience facilitated Wayfinding, as the process was different with a medically fragile infant. As another parent explained, “In some ways [experience] hurt because I did have hopes and I did have expectations (21).”

Subprocess: Navigating the relationship with the healthcare team

As a subprocess of Wayfinding, navigating the relationship with the healthcare team involved parents’ efforts to sustain a working relationship with their infant’s caregivers – not only as individuals, but as a collective system. Navigating the relationship with the healthcare team is central to Wayfinding, as most infants with critical CHD need multiple interventions and life-long follow up (Table 2.o). For parents, navigating this relationship entailed managing conflicting priorities between the healthcare team and the parent; assessing whether the parent and their infant were seen, heard, and valued by the healthcare team; and handling messages from the healthcare team.

Managing conflicting priorities. Parents perceived conflicting priorities when the healthcare team was focused primarily on the infant’s survival: “hyperfocused on the diagnosis” (06) or “just there to do their job, check some things off” (25). While parents were concerned about their child’s survival, they also considered quality of life in the present and long term (Table 2.p).

Many parents described a dawning understanding that breastfeeding – and by extension, the parent-infant relationship – was not a priority of the medical system (Table 2.q). While breastfeeding was typically not a healthcare team priority, it was described as a “very important wish” (21) for parents that was central to parental identity (Table 2.r). Some parents communicated with the healthcare team to try to overcome these conflicting priorities, while others disengaged (Table 2.s).

Assessing whether the parent and infant were seen, heard, and valued. Parents assessed the level to which the healthcare team saw, heard, and valued the parent and the infant. In some cases, the parent was invited into collaborative care. For these parents, navigating the relationship required less burden of time and energy. In contrast, some parents felt unseen, unheard, or actively marginalised (Table 2.t). One parent described feeling “like I did not matter as a human being” (19), while others perceived being “disrespected and traumatised” (04) or “looked down on … judged … for trying so hard [to breastfeed]” (24). Not feeling seen, heard, or valued by the healthcare team was emotionally taxing and prompted engagement in processes to protect breastfeeding, such as seeking knowledge or going against the healthcare team. Navigating the relationship with the healthcare team was more difficult when parents perceived their child being treated as a statistic – that the healthcare team “[did not] want to deviate” (08) from feeding protocols (Table 2.u). In contrast, navigating the relationship with the healthcare team required less energy when parents perceived that their child was viewed as an individual (Table 2.v).

Handling messages from the healthcare team. Parents synthesised numerous feeding-related messages from the healthcare team, constantly weighing what they were told against their own assessment and deciding how to proceed. Messages about breastfeeding were linked to concerns about infant weight, which were not always viewed as legitimate by parents. Most often, messages were perceived as negative or unsupportive of breastfeeding and were considered a barrier to parents’ feeding goals (Table 2.w). Common warnings included: “these babies just donʼt exclusively breastfeed” (27) and “it’s easier for them to take a bottle” (05). Parents were often instructed to fortify feedings and permitted to offer the breast for “comfort” (11) or “pleasure” (19) rather than nutritional value. Such messages were perceived to be a “traditional mindset” (10), prompting many parents to engage in the protective process of seeking knowledge to verify what they were told (Table 2.x). Parents consistently described needing permission to breastfeed, with one parent recalling, “It was kind of like a three-parent household when we were in the hospital” (08). In extreme cases, any guise of parental authority over feeding was eradicated (Table 2.y).

While negative messages about breastfeeding dominated, some parents received positive messages of reassurance and encouragement. A few described institutions with unified support of breastfeeding, which was enough to mitigate other barriers (Table 2.z).

Subprocess: Protecting the direct breastfeeding relationship

Protecting the breastfeeding relationship involved parents’ efforts to ensure the opportunity to work toward breastfeeding by advocating for what was needed, seeking knowledge, relying on an ally in the healthcare team, and going against the healthcare team. All parents engaged in these protective processes, but the level of engagement varied. Parents experiencing a lack of healthcare support devoted much energy to protection, with going against the healthcare team a last resort.

Advocating for what was needed. All parents advocated to protect breastfeeding, which involved “standing your ground” (30) and “having a voice” (29). Parents often had to repeat their breastfeeding requests incessantly, before and after birth. When healthcare team support was low, parents recounted being “adamant” (17), “pushing” (10), and “fighting” (02; Table 2.aa). In unsupportive environments, language alluding to war was pervasive, with parents being “hypervigilant” (04) using research as “ammunition” (04) or a “best line of defence” (24), or fighting an “uphill battle” (26).

Advocating may have relied on social capital or privilege, as some parents discussed feeling “out of my league” (12) or “condescended to” (24; Table 2.bb). In other cases, advocating was made easier by a non-hierarchical relationship with the healthcare team (Table 2.cc). In those supportive healthcare systems, the burden of advocating was shifted away from the parent, although it was never completely absent.

Seeking knowledge. To protect breastfeeding, many parents sought knowledge to fill perceived gaps in understanding. This often occurred as a response to problems during the subprocess of doing the long, hard work (e.g., transitioning from tube feeding), or as a response to the subprocess of navigating the relationship, if messages about breastfeeding elicited distrust.

Knowledge was sought from academic research or – most often – from other parents of infants with CHD via social media. Many parents viewed social media as a shadow healthcare system, filling critical knowledge gaps. One parent was invited to share this knowledge with their healthcare team, which was a positive contributor to this relationship (Table 2.dd). The process of seeking knowledge supported persistence in the Wayfinding process and provided expectations for the journey (Table 2.ee).

Relying on an ally in the healthcare team. At times, breastfeeding was protected when parents relied on an ally who was part of their infant’s primary cardiac healthcare team. This ally took action to help the parent achieve their breastfeeding goals, often in contrast to institutional culture or policies (Table 2.ff). Some allies were in positions of power (e.g., surgeon, cardiologist, physician) and could set the institutional tone. For parents who experienced this top-down support, the burden of protecting breastfeeding was lifted (Table 2.gg). In contrast, when parents encountered an unsupportive healthcare team, an ally sometimes helped the parent in going against feeding directives (Table 2.hh). Allyship increased parents’ perception that they were seen, heard, and valued; facilitated the relationship with the healthcare team; and supported parents in doing the long, hard work of establishing breastfeeding.

Going against the healthcare team. Protecting the breastfeeding relationship sometimes involved parents going against feeding-related directives. Parents took this action in response to the healthcare team’s persistent reluctance to support breastfeeding in a way that was acceptable to the parent (Table 2.ii). While some parents communicated their decision to change the feeding plan, it was more common for parents to hide what they were doing, not wanting to “rock the boat” (27). For some parents, taking things into their own hands was described as a reclaiming of parental autonomy (Table 2.jj). While going against the healthcare team was not a comfortable process, some parents were willing to strain the relationship with the team to do what they determined was best for their infants.

Subprocess: Doing the long, hard work

Doing the long, hard work involved parents’ physical and technical efforts to establish breastfeeding with their child while moving through challenges related to hospitalisation, neonatal surgery, and cardiac physiology. This entailed building and maintaining a milk supply, gradually working on the infant’s oral skills, and persisting even though “it felt impossible at times” (04). The need to engage in this subprocess could be facilitated by the healthcare team and influenced by previous breastfeeding experience or a smooth clinical course.

Building and maintaining a milk supply. Building and maintaining a milk supply was considered critical to the possibility of breastfeeding, as early parent-infant separation interrupted the breastfeeding trajectory (Table 2.kk). Most parents described pumping immediately after birth and around the clock. In contrast, one parent blindsided by a postnatal diagnosis explained, “[Pumping] wasnʼt something I was even thinking about at that point, because I just wanted her to live” (23). Parents recognised that pumping was necessary and one thing they could do for their baby. However, pumping was described as “dreadful” (12), “exhausting” (26), “disappointing” (14), and “the worst” (12). Many parents found extended pumping unsustainable, particularly in the context of their child’s significant medical needs (Table 2.ll).

Gradually working on the infant’s oral skills. Parents described gradually working on the infant’s oral skills in hopes of breastfeeding. This process can be considered multi-staged technical work (i.e., illness-related work that can be addressed by common clinical interventions). Reference Thygeson, Sturmberg and Martin31 Parents used some or all of the following strategies: oral care with human milk while the baby was nil per os (npo), pacifiers to stimulate sucking, skin-to-skin contact, non-nutritive latching at an empty breast, nipple shields, assessment and assistance by feeding specialists, slow incorporation of nutritive breastfeeding, and pre- and post-breastfeeding weights to track volume (i.e., test weights). The infant’s first latch at the breast was universally described as pivotal. This first latch could be facilitated by the healthcare team (Table 2.mm), which positively impacted the subprocess of navigating the relationship.

Persisting even though “it felt impossible at times.” Doing the long, hard work of establishing a milk supply and building infant oral skills required persistence and strength. Parents described a “roller coaster journey” (09) that could be “stressful” (07), “gruelling” (08), and “frustrating” (25). Many parents reported wanting to give up at times (Table 2.nn), but drawing strength from their infant’s resilience (Table 2.oo). For these parents, persisting in doing the long, hard work ultimately led to breastfeeding establishment. However, the process looked different than parents had envisioned and they needed to adapt to changing circumstances by, as one parent explained, “holding hopes and dreams with an open hand” (12).

Discussion

This study addresses a critical knowledge gap as the first in-depth examination of the process of establishing direct breastfeeding with an infant with critical CHD, from parents’ perspectives. The findings reveal that, while challenging, breastfeeding is feasible, meaningful, and consequential.

The Wayfinding process aligns with previous work in other neonatal populations. Demirci et al’s Reference Demirci, Happ, Bogen, Albrecht and Cohen32 theoretical model of late preterm breastfeeding describes a “volatile and labour-intensive” process, echoing the Wayfinding subprocess of doing the long, hard work. Many strategies described by parents to do this long, hard work align with Spatz’s Reference Spatz33 10 steps for promoting and protecting breastfeeding for vulnerable infants (e.g., pumping early and often, non-nutritive latching, test weighing).

However, the primary issues described by Demirci and colleagues (e.g., suck-swallow coordination, snacking behaviour) Reference Demirci, Happ, Bogen, Albrecht and Cohen32 are different than those affecting infants with critical CHD (e.g., neonatal surgery, extensive time npo, volume restriction, lengthy fortification). Reference Floh, Slicker and Schwartz34 Jones et al. Reference Jones, Desai and Fogel35 have identified numerous factors that contribute to disruptions in feeding development for infants with critical CHD, including cardiac physiology, necrotising enterocolitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, surgical intervention, sedation and medication, chylothorax, respiratory support, neurodevelopment, genetic syndromes, a noxious feeding environment, nerve paralysis/paresis, and dysphagia. All of these disruptions were described by our sample as part of the influencing condition of the infant’s clinical course, often resulting in increased engagement in Wayfinding processes to protect the breastfeeding relationship. Furthermore, the critical nature of critical CHD results in a looming threat of life-and-death consequences, which does not dissipate after discharge. While other vulnerable neonates may also experience post-discharge health concerns, the parents in this study reported infant health challenges and multiple surgeries that could extend the Wayfinding process well into the first year.

It is notable that 57% of the infants in this sample had single ventricle physiology, considered the most severe form of critical CHD with high risk for oral feeding problems. Reference Butto, Mercer-Rosa and Teng36 Previous literature reporting breastfeeding for infants with single ventricle CHD is limited to one case study, Reference Steltzer, Sussman-Karten, Kuzdeba, Mott and Connor37 and many parents in our sample received messages that breastfeeding would not be possible. In the case study, breastfeeding was described as a challenging process necessitating a strong relationship between the parent and the healthcare team. Reference Steltzer, Sussman-Karten, Kuzdeba, Mott and Connor37 Our study expands upon this previous finding, demonstrating that breastfeeding an infant hospitalised for critical CHD can occur without cohesive healthcare team support, although the parental burden is substantial.

Our findings reveal that parents often felt compelled to seek support outside of the healthcare system or go against feeding directives, and suggest that few U.S. cardiac centres prioritise families’ breastfeeding goals. Concerningly, some parents described being actively misinformed by their healthcare team, receiving messages that human milk is not safe for infants with critical CHD or that breastfeeding is more work for these infants than bottle feeding. These types of statements conflict with available evidence, which demonstrates that exclusive human milk feeding confers benefits including a reduced risk of necrotising enterocolitis in this population Reference Elgersma, McKechnie and Schorr5 and that, as the American Heart Association explains in its online patient education, “the ‘work’ of breastfeeding is actually less than the work of bottle feeding.” Reference Marino, O’Brien and LoRe9,38 Especially considering that infant feeding holds deep moral and relational meaning for parents, it is ethically objectionable for healthcare teams to dissuade families from pursuing human milk or breastfeeding goals based on opinions that contradict previous evidence.

Our findings point to a clear gap in practice in which families are not receiving evidence-based, family-centred breastfeeding care, which is in line with previous work demonstrating a lack of consensus about best practices for breastfeeding in this population. Reference Elgersma, McKechnie, Gallagher, Trebilcock, Pridham and Spatz23 While research focused on breastfeeding for infants with critical CHD is sparse, previous literature describes relevant clinical practices that support breastfeeding for other vulnerable neonatal populations. These practices include prenatal lactation care with feeding specialists; frequent, continuous skin-to-skin contact; oral care with colostrum; direct breastfeeding for the first oral feed (vs. bottle feeding); non-nutritive oral practice at the breast; using test weights to measure direct breastfeeding volume; specialised training for hospital staff; and evidence-based feeding policies that are clearly communicated to families. Reference Edwards and Spatz39–Reference Swanson, Elgersma and McKechnie42 Studies testing the safety and feasibility of these practices for infants with critical CHD are emerging, Reference Lisanti, Buoni, Steigerwalt, Daly, McNelis and Spatz43,Reference Harrison and Brown44 but more research is needed to determine whether these practices can effectively increase the low rates of breastfeeding in this population.

Furthermore, there is a growing interest in individualised, family-centred developmental care as a way to counteract the negative impact of the hospital environment for infants with critical CHD and their families. Reference Lisanti, Vittner, Medoff-Cooper, Fogel, Wernovsky and Butler45 This approach advocates cue-based, developmentally appropriate infant care; supports parental engagement in caregiving processes; and has potential to improve breastfeeding outcomes through neuroprotective practices such as skin-to-skin care Reference LaRonde, Connor, Cerrato, Chiloyan and Lisanti46 and infant-driven feeding. Reference Lisanti, Cribben, Connock, Lessen and Medoff-Cooper47 Unfortunately, as in the case of the parent who perceived the healthcare team as primarily concerned with “preserv[ing] the function of the human body” (19), many of the participants in this study described dismissive, inflexible hospital environments that operated in stark contrast to developmental care principles. Our findings suggest that there is a clear opportunity for improvement in individualised, family-centred developmental care in U.S. cardiac centres.

For parents in our sample, a perceived lack of support for feeding goals could result in impaired mental health. Clinically concerning symptoms of depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress for parents in this population have been well described Reference McKechnie, Pridham and Tluczek48,Reference Woolf-King, Arnold, Weiss and Teitel49 and an additional burden related to infant feeding can exacerbate this distress, as highlighted by previous qualitative research. Reference Hartman and Medoff-Cooper50,Reference Tregay, Brown, Crowe, Bull, Knowles and Wray51 The link between feeding challenges and parents’ distress might be due in part to parental role alteration (i.e., a perceived inability to provide care or comfort for the infant), which has been associated with increased anxiety and depression in parents of infants hospitalised for critical CHD. Reference Lisanti, Kumar, Quinn, Chittams, Medoff-Cooper and Demianczyk52,Reference Lisanti, Demianczyk and Vaughan53 Considering that feeding is a critical aspect of care and direct breastfeeding an empowering way to comfort an infant with critical CHD, our findings demonstrate missed opportunities to support parents’ mental health during a tumultuous time.

It is important to note that parents in our sample experienced varying degrees of difficulty in establishing breastfeeding with their infant suggesting that, for some, breastfeeding may be more feasible than previously understood. Our findings indicate that healthcare providers should merge clinical experience with individualised assessment, resist the default assumption of considering breastfeeding too difficult for this population, critically examine the evidence behind unit breastfeeding policies, intentionally address institutional barriers to breastfeeding, and work collaboratively with parents to support feeding goals.

Considering the critical lack of evidence about breastfeeding in this population, Reference Elgersma, McKechnie, Gallagher, Trebilcock, Pridham and Spatz23 there is an urgent need for future research to identify clinically appropriate support for breastfeeding from prenatal diagnosis through the first year of life. The conceptual model of Wayfinding highlights opportunities for research and practice change. Future translational research is needed to develop and test comprehensive, family-centred interventions that facilitate breastfeeding for infants with critical CHD. Such interventions should provide evidence-based lactation care, adapted to the specific needs of this population, to aid parents in doing the long, hard work; should span the prenatal and postnatal timeframe to facilitate clear, consistent messaging from the healthcare team; should empower parents to advocate for their feeding goals; and should acknowledge that infant feeding can be deeply meaningful in the midst of a highly traumatic family experience. Effective, accessible interventions are critically needed to increase the low rates of breastfeeding in this population and have the potential to improve infant and family outcomes.

Future research should also examine the impact of breastfeeding on these outcomes for infants with critical CHD and the potential mechanisms to explain differences in outcomes, particularly as participants in our study observed physical and developmental benefits for their infants related to breastfeeding that are not well understood in infants with critical CHD. As one example, research into the interaction between human milk, direct breastfeeding, and the infant microbiome is beginning to emerge, with a particular focus on preterm populations. Reference Nolan, Rimer and Good54 Direct breastfeeding has been shown to confer unique immunological benefits, Reference Patel, Johnson and Meier10,Reference Al-Shehri, Knox, Liley and Netto11 and is a reliable means of delivering bioactive immunological properties directly to the infant without risk of alterations related to milk storage and handling that could denature these delicate structures. Reference Păduraru, Dimitriu, Avasiloaiei, Moscalu, Zonda and Stamatin55 However, to our knowledge, there has been little investigation into the relationship between direct breastfeeding and the microbiome of infants with critical CHD. A better understanding of the relationship between breastfeeding and an infant’s health and development could support clear, consistent healthcare team-parent communication, thereby facilitating navigation of the relationship with the healthcare team.

Future work should also focus on the influencing condition of concern about weight gain, particularly as ubiquitous fortification and stringent feeding protocols were perceived to interfere with breastfeeding establishment in our sample. We recommend future research on the development and testing of alternative fortification strategies Reference Haiden, Haschke, S.Karger, Embleton, Haschke and Bode56 for infants with critical CHD, which could include targeted fortification Reference Merlino Barr and Groh-Wargo57 or fortification “shots” provided as medication via after breastfeeding – a practice used by some Danish neonatal ICUs (Ragnhild Måastrup, PhD, e-mail communication, March 2021). Advanced statistical methods could support the development of risk prediction models to help identify infants with critical CHD who are at low risk for growth failure and may not need immediate postoperative or post-discharge fortification.

Limitations

The primary study limitation is a sample that was majority white, college educated, and financially resourced. Sample demographics might reflect the impact of structural racism and social determinants of health (SDoH), as there are well-documented disparities in human milk and breastfeeding rates for vulnerable infants associated with racism Reference Thomas58 and socioeconomic status. Reference Patel, Johnson and Meier10 Although parents in our sample reported variance in SDoH, findings cannot be generalised to all populations. There is a clear need for research to determine the impact of SDoH on feeding for infants with critical CHD. Additional limitations could include the cross-sectional design with retrospective explanation of a temporal process reliant on participant recall; the potential for self-selection bias; or recruitment from selected online sites.

Conclusion

The findings in this study are a step toward addressing the knowledge gap about direct breastfeeding for infants with critical CHD. The conceptual model of Wayfinding explains how breastfeeding can be established with these infants. Future work is needed to implement family-centred interventions that support parents’ feeding goals, with potential to increase the current low rates of direct breastfeeding in this population and improve infant and family health.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951122003808

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the participants and thank them for their generosity of time, expertise, and spirit.

Financial support

Support for this study was provided by the Sophia Fund, School of Nursing Foundation, University of Minnesota.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and have been approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (STUDY00013186).