Plain language summary

This study applies computational methods to revisit the Formalist theory of defamiliarization, which posits that art renews perception by rearranging familiar forms in unpredictable ways. The research goal was to formalize and measure the stylistic tension between predictability and surprise using a large language model as a stand-in for a historically situated reader. To achieve this, the study employed a multi-stage experimental design. First, a GPT-2 style transformer model (223M parameters) was pre-trained on a large, high-quality corpus of modern Chinese text (FineWeb Edu Chinese V2.1) to establish a neutral linguistic baseline. This model was then fine-tuned for five epochs exclusively on the Selected Works of Mao Zedong to simulate a reader becoming saturated with “Maospeak,” the highly formulaic and militant language of the Mao era. The core metric was perplexity, which quantifies the model’s predictive uncertainty, or “surprise,” at each token. The primary finding was a dual process of familiarization and defamiliarization. By tracking the largest decreases in perplexity, the study identified the core phraseology of Maospeak, including canonical lists of class enemies and rigid rhetorical patterns. This “cognitive overfitting” demonstrated how propaganda automates language to create a predictable, low-perplexity environment and legitimatize violence.

![]() $N$

-gram entropy analysis confirmed that the Mao corpus was measurably more repetitive than a literary corpus at smaller

$N$

-gram entropy analysis confirmed that the Mao corpus was measurably more repetitive than a literary corpus at smaller

![]() $n$

-gram sizes, i.e., in its foundational vocabulary and short collocations. Concurrently, as the model specialized in Maospeak, its average perplexity on a corpus of 100 modern Chinese novels increased, making literary language appear more alien. Microscopic analysis of novels by Zhang Wei, Lilian Lee and Dung Kai-cheung revealed how literary style creates “non-anomalous surprise” through high-perplexity moments, such as creative metaphors, the use of classical Chinese syntax and the abrupt insertion of non-standard Chinese languages such as Cantonese. Ultimately, the research proposes “cognitive stylometry” as a new mode of inquiry, redefining style as a measurable cognitive signature that orchestrates a reader’s predictive processing by balancing familiar grounding with moments of meaningful deviation.

$n$

-gram sizes, i.e., in its foundational vocabulary and short collocations. Concurrently, as the model specialized in Maospeak, its average perplexity on a corpus of 100 modern Chinese novels increased, making literary language appear more alien. Microscopic analysis of novels by Zhang Wei, Lilian Lee and Dung Kai-cheung revealed how literary style creates “non-anomalous surprise” through high-perplexity moments, such as creative metaphors, the use of classical Chinese syntax and the abrupt insertion of non-standard Chinese languages such as Cantonese. Ultimately, the research proposes “cognitive stylometry” as a new mode of inquiry, redefining style as a measurable cognitive signature that orchestrates a reader’s predictive processing by balancing familiar grounding with moments of meaningful deviation.

Introduction: Rethinking defamiliarization in the age of LLMs

Large language models (LLMs) present an exciting opportunity for literary theory, inviting new perspectives on the foundational concepts, such as meaning, attention and memory. Yet, in addition to ethical concerns (Weidinger et al. Reference Weidinger, John and Rauh2021; Hendrycks, Mazeika, and Woodside Reference Hendrycks, Mazeika and Woodside2023; Kirschenbaum Reference Kirschenbaum2023; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Sha and Zhao2024), their integration within humanistic studies faces two disciplinary challenges. On the one hand, radically anthropocentric beliefs continue to frame machine intelligence through a lens of inadequacy, as seen in Noam Chomsky’s critique of ChatGPT’s “false promise” (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2023) or Michele Elam’s assertion that the “creative process cannot be reduced to a prompt” (Elam Reference Elam2023). On the other hand, computational approaches that are adopted by literary scholars risk veering so far into benchmarking and quantification that they lose sight of literature as a source of aesthetic experience and interpretive engagement. These concerns are particularly relevant to the computational analysis of literary style, or stylometry, where the focus on precision metrics often overshadows the very texts under study. Paradoxically, highly accurate attribution models might fail to tell us anything about style.

An alternative path may lie in restarting the conversation between probabilists and humanists that unfolded in the early twentieth century but then subsided under historicist pressures. In 1913, Andrey Markov analyzed 20,000 letters from Pushkin’s poem Eugene Onegin to demonstrate his theory of dependent trials, later known as Markov chains, proving that the probability of a letter being a vowel or a consonant depends on the class of the preceding letter (Markov Reference Markov2006). Decades later, Claude Shannon reframed this problem in the empirical terms of information theory: “How well can the next letter of a text be predicted when the preceding N letters are known?” (Shannon Reference Shannon1951, 50). He demonstrated that humans possess an implicit knowledge of language statistics, effectively casting them as predictive language models. The aesthetic implications of this tension between predictability and surprise were anticipated by the Formalist scholar Viktor Shklovsky, who argued that art combats the “automatization of perception,” a process whereby, through habit, life “becomes nothing and disappears” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 80). By contrast, in a process he called defamiliarization (ostranenie), art “increases the complexity and duration of perception” and “recovers the sensation of life” by rearranging familiar forms in unpredictable ways (Resseguie Reference Resseguie1991; Steiner Reference Steiner1984).

Recent advances in computational hardware, artificial intelligence and cognitive science call for a renewed humanistic perspective on these complementary phenomena. Trained on vast corpora spanning literature, journalism and social media, LLMs represent what Shklovsky could call the “familiar,” a statistically distilled reflection of human knowledge, language use and cultural expectations. Meanwhile, the concept of “defamiliarization” has been reinvigorated with new empirical evidence, from eye-tracking experiments showing that readers fixate longer on unexpected words (McDonald and Shillock Reference McDonald, Shillock, Carreiras and Clifton2004; Bonhage et al. Reference Bonhage, Mueller and Friederici2015) to fMRI scans revealing heightened mental engagement with unusual sentence structures, consistent with theories of the brain as a predictive organ (Dehaene et al. Reference Dehaene, Cohen and Sigman2005; Schuster et al. Reference Schuster, Weiss and Hutzler2025; Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Choi and Lowder2016; Bohrn et al. Reference Bohrn, Altmann and Lubrich2012; Clark Reference Clark2013, Reference Clark2016). Shannon’s blurring of the human/machine reader distinction has also been pushed further, with research suggesting parallels between narrative comprehension in humans and in Transformer-based models (Caucheteux and King Reference Caucheteux and King2022; Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Sumers and Yamakoshi2024), though scholars urge caution (Feghhi et al. Reference Feghhi, Hadidi and Song2024; Soni et al. Reference Soni, Srivastava and Kording2024; Fodor, Murawski, and Suzuki Reference Fodor, Murawski and Suzuki2025). Humanists are particularly well-positioned to contribute to this interdisciplinary dialogue – not to surrender to the discourse of technoscience, but to offer new perspectives on literature as a source of multi-layered engagements with our cognitive, emotional and predictive faculties (Kurzynski Reference Kurzynski2025), a goal that motivates this project.

Methods: Predictability and perplexity

The tension between expectation and surprise, central to both information theory and the notion of defamiliarization, can be formalized using perplexity, a measure of a statistical model’s predictive certainty (Jelinek et al. Reference Jelinek, Mercer and Bahl1977). Lower perplexity on the correct output indicates high confidence, while higher perplexity signals surprise. Most of the currently available LLMs learn to minimize this surprise by iterating over large amounts of text, either by predicting the next token in a sequence (autoregressive models) or by reconstructing an original sequence from a perturbed one (masked language models) (Paaß and Giesselbach Reference Paaß and Giesselbach2023, 19–78).

In this study, perplexity will serve as a metric for simulating human engagement with texts. While acknowledging the significant differences between natural cognition and artificial intelligence, notably the different ways in which they emerge (Lillicrap et al. Reference Lillicrap, Santoro and Marris2020), I leverage language models as proxies of historically situated human readers to revisit Shklovsky’s argument (Varnum et al. Reference Varnum, Baumard and Atari2024). Style, in this framework, is not merely a property of the text itself but is understood in relation to the predictive coding mechanisms inherent to both biological and artificial cognition. Phrases that elicit high perplexity will be especially relevant here, aligning with the understanding of style as a “deviation from the norm” (Enkvist, Spencer, and Gregory Reference Enkvist, Spencer and Gregory1964; Herrmann, Dalen-Oskam, and Schöch Reference Herrmann, van Dalen-Oskam and Schöch2015), whereas highly predictable phrases will instead reveal the automatized linguistic background against which stylistic distinctions emerge. Of particular importance to this article, however, is how an initially unfamiliar phrase becomes familiar through repeated exposure, and, conversely, how a particular phraseology becomes surprising when a model overfits on a different linguistic style. Such a process may offer a compelling computational analog for phenomena of broader cognitive-historical interest: for instance, how literary canons form, or how, under specific historical circumstances, prescriptive linguistic norms violently narrow the scope of legitimate expression (Bloch Reference Bloch1975; Epstein Reference Epstein1990; Ji Reference Ji2004; Hughes Reference Hughes2009; Klemperer Reference Klemperer and Brady2013).

Stylometrists have rarely considered predictability a primary stylistic feature, traditionally favoring more tangible elements like function words, syntactic structures and thematic profiles (Lutosławski Reference Lutosławski1898; Mosteller and Wallace Reference Mosteller and Wallace1963; Burrows Reference Burrows1987; Herrmann, Dalen-Oskam, and Schöch 2015; Rybicki, Eder, and Hoover Reference Rybicki, Eder, Hoover, Crompton, Lane and Siemens2016; Evert et al. Reference Evert, Proisl and Jannidis2017). This has changed with the advent of LLMs, whose human-like output spurred an urgent search for markers to differentiate machine from human text, with perplexity emerging as a key candidate. An influential early paper by Holtzman et al. argued that human text is not the most probable text: “natural language rarely remains in a high probability zone for multiple consecutive time steps, instead veering into lower-probability but more informative tokens” (Holtzman et al. Reference Holtzman, Buys and Du2020). Subsequent studies confirmed that low-perplexity sequences often indicate machine provenance (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Lee and Khazatsky2023; K. Wu et al. Reference Wu, Pang and Shen2023). However, as newer LLMs produce text that is “nearly indistinguishable from human-written text from a statistical perspective” (Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Tonmoy, Zaman, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023), researchers have developed methods like watermarking, which embeds statistically detectable patterns into AI-generated content for provenance verification (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Ananth and Li2023; Kirchenbauer et al. Reference Kirchenbauer, Geiping, Wen, Krause, Brunskill and Cho2023). A few studies in the computational humanities have also begun to explore perplexity’s stylometric potential, using it to distinguish canonical from non-canonical novels (Y. Wu et al. Reference Wu, Bizzoni and Moreira2024), machine from human translation (Bizzoni et al. Reference Bizzoni, Juzek and España-Bonet2020) and political discourse from novelistic prose (Kurzynski Reference Kurzynski2023, Reference Kurzynski2024), signaling a broader turn toward evidence of cognitive and informational processing in literary analysis.

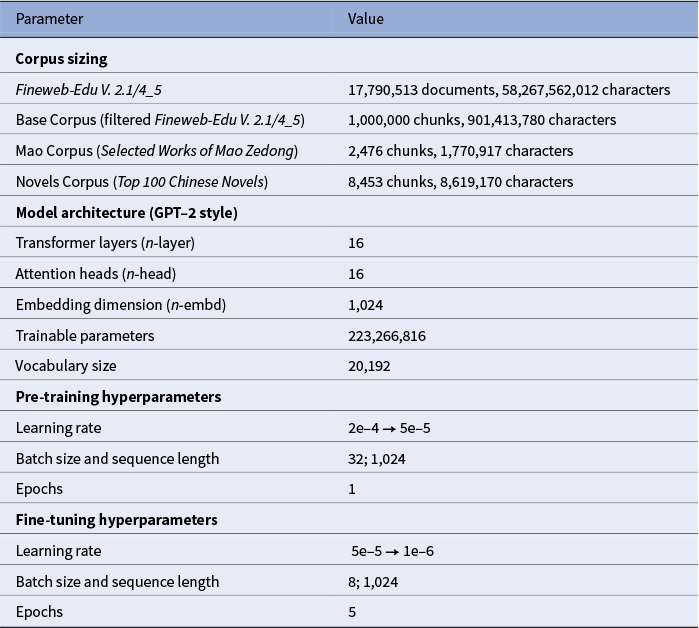

Datasets and tokenizers

The foundation of this study is the Fineweb Edu Chinese V2.1, a large-scale, high-quality Chinese corpus constructed from diverse datasets, including Wudao, Skypile, IndustryCorpus and Tele-AI (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Dai and Wang2025). The Fineweb authors employed a filtering pipeline where a scoring BERT model evaluated each document on a 0-to-5 scale for educational value and writing quality. The present study utilizes the “4–5” split, which contains only the highest-scoring, deduplicated content. From this top-tier partition of approximately 70 GB, one million Chinese passages varying in length from 256 to 1,024 characters were sampled for pre-training, serving as a neutral linguistic environment. Passages in languages other than Chinese as well as those with a high percentage of numbers and scientific notation were removed.

Two distinct test corpora were then constructed to represent stylistically opposed domains. The first is a seven-volume compilation of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong 毛泽东选集, which combines the official five-volume collection (covering 1925–1957) with the two unauthorized “Jinghuo” 静火 volumes, extending the collection through 1976. Together, these texts comprise Mao’s most significant speeches, essays and directives, establishing the core tenets of Mao Zedong Thought and representing the target style for the familiarization hypothesis (Leese Reference Leese and Cook2014). The second test corpus is the Top 100 Chinese Novels of the 20th Century, a canon compiled in 1999 by Asia Weekly 亚洲周刊 in tandem with a jury of fourteen literary experts (Qiu Reference Qiu1999). The Chinese term xiaoshuo 小说 (lit. “small talk”) is broader than the English “novel,” so this list includes both full-length novels and short story collections from Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, providing a diverse sample of modern literary styles. All texts were normalized and converted to simplified Chinese. To prevent longer documents from dominating the datasets, a sampling technique was applied to ensure that each document from either corpus could contribute no more than 100 chunks of 1,024 characters (Table 1).

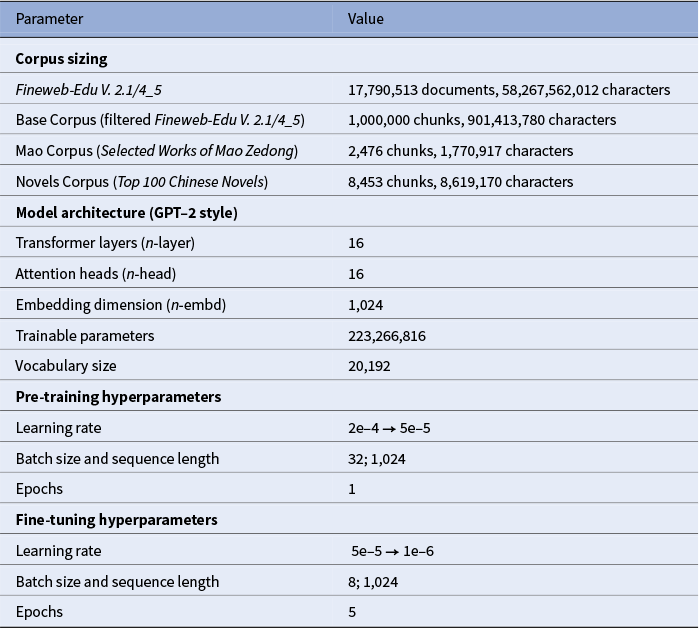

Table 1. Corpus and model training parameters.

To prevent data leakage, i.e., the inclusion of evaluation content in the training data, an

![]() $n$

-gram hashing technique was employed. This is crucial for measuring familiarity with a style rather than memorization of specific passages or even entire documents. All documents in the test corpora were processed to generate a set of unique, character-level 13-grams. This

$n$

-gram hashing technique was employed. This is crucial for measuring familiarity with a style rather than memorization of specific passages or even entire documents. All documents in the test corpora were processed to generate a set of unique, character-level 13-grams. This

![]() $n$

-gram size is long enough to capture verbatim quotations but short enough to avoid falsely flagging common Chinese expressions; it also aligns with contamination analysis methods used for LLMs (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mann and Ryder2020; OpenAI 2023). Each 13-gram was hashed using MD5 to create compact fingerprints, which were then used to scan all training documents. Any match was verified with a literal string search, and confirmed documents were discarded from the training set.

$n$

-gram size is long enough to capture verbatim quotations but short enough to avoid falsely flagging common Chinese expressions; it also aligns with contamination analysis methods used for LLMs (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mann and Ryder2020; OpenAI 2023). Each 13-gram was hashed using MD5 to create compact fingerprints, which were then used to scan all training documents. Any match was verified with a literal string search, and confirmed documents were discarded from the training set.

The conversion of raw text into numerical identifiers via a tokenizer is a foundational step that shapes the outcome of any computational analysis of language. While state-of-the-art models frequently employ subword tokenizers like byte-pair encoding (BPE), these algorithms introduce significant analytical challenges, particularly for logographic languages like Chinese that lack explicit word delimiters. For example, BPE tokenizers operate by iteratively merging frequent pairs of characters or subwords, which can result in segmentations that are both non-intuitive and inconsistent. A greedy BPE tokenizer might segment 学科技 (“to study electronics”) as 学科 (“discipline”) 技 (“skill”), rather than 学 (“to study”) 科技 (“electronics”). This happens because 学科 (“discipline”), an otherwise valid word, has been learned first by the tokenizer during training and thus appears earlier in the list of merges. Similarly, 第二天 (“the next day”) might be merged into a single token, while 第三天 (“the third day”) might not, as the former occurs more frequently in the training data, etc.

While such inconsistencies may not drastically alter aggregate perplexity scores across a large corpus, they can severely distort the close analysis of individual sequences, mistaking the quirks of a tokenizer for genuine authorial choices. A BPE tokenizer imposes its own statistical “theory” of language onto a text, a theory biased towards common symbol collocations found in its training data. This pre-processing can effectively neutralize the very stylistic effects under study; a sequence of characters might be collapsed into a single token, artificially lowering its perplexity and rendering the author’s stylistic choice invisible to the model. In computational studies of classical Chinese poetry, for instance, the fact that DeepSeek R1 represents ai’ai 曖曖 (“dimly”) as four tokens [923, 247, 923, 247] but yi’yi 依依 (“softly”) as one token [66660] can severely impact character-to-character comparisons (Kurzynski, Xu, and Feng Reference Kurzynski, Xu and Feng2025). To circumvent such inconsistencies, this study treats each Chinese character as a distinct token, allowing for a more fine-grained analysis of which characters in multi-character words and phrases elicit surprise. A custom character-level tokenizer was constructed by training on the first two million documents from the Fineweb-Edu corpus, and the resulting vocabulary was supplemented with single-character tokens from the widely used bert-base-chinese model (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang and Lee2019). The final vocabulary consists of 20,192 tokens and was used consistently across all experiments in this study.

Experiment 1: Macroscopic analysis of Maospeak

The first experiment is a macroscopic study examining how a language model’s statistical worldview is altered when its linguistic environment becomes saturated with a powerful idiolect. “Maospeak” (Mao yu 毛语 or Mao wenti 毛文体 in its written form) refers to the militant, ideologically charged language style that emerged during the Mao Zedong era (1949–1976) in the People’s Republic of China (Li Reference Li1998). While Mao himself was a creative rhetorician, the institutionalization of his discourse transformed his words into instruments of mass indoctrination, producing a ritualistic culture of near-compulsory recitation (Lifton Reference Lifton1956; Leese Reference Leese2011; Kiely Reference Kiely2014). This engineered form of discourse became a central feature of everyday life, particularly during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when proficiency in Maospeak became essential for survival amid massive outbursts of violence (Ji Reference Ji2004; Juntao and Brady Reference Juntao, Brady and Brady2012; Schoenhals Reference Schoenhals2007). Though Mao passed away in 1976, his distinctive language continues to influence contemporary Chinese speech, from jingoistic discourse to colloquialisms like xiaomie (消灭, lit. “to annihilate”) for finishing a meal or the encouraging phrase haohao xuexi, tiantian xiang shang (好好学习, 天天向上, “study well, every day upwards”) (Link Reference Link2012, Reference Link2013; Barmé Reference Barmé1996).

The experiment tests a dual hypothesis. First, I hypothesize that a dominant political style has a representative phraseology that, through frequent exposure, becomes automatic in the Shklovskian sense. The experiment aims to identify these core expressions by tracking changes in model’s loss, predicting that as the model is exposed to Maospeak, its loss will decrease significantly on ideologically reinforced phrases, specifically those that were either absent from the training data (Base Corpus) and/or frequently repeated in the fine-tuning data (Mao Corpus). Second, I hypothesize that as the model overfits on Maospeak, the stylistic and lexical patterns of literary prose (Novels Corpus) will become increasingly alien. The literary language, in essence, will become more difficult for the model to predict as its perceptual baseline shifts.

The experiment uses a GPT-2 style Transformer model pre-trained from scratch on the Base Corpus for one epoch and then fine-tuned for five epochs on the Selected Works (Table 1). The core analysis compares the model’s performance on the Mao Corpus before fine-tuning (“Pre-trained”) and after (“Epoch 5”). To track how the model internalizes this specific discourse, I deliberately deviate from standard practice and compute loss on the fine-tuning corpus itself. If

![]() $Q\left({x}_i|{x}_{<i}\right)$

denotes the probability that model

$Q\left({x}_i|{x}_{<i}\right)$

denotes the probability that model

![]() $Q$

assigns to token

$Q$

assigns to token

![]() ${x}_i$

given the preceding tokens, and if, following Shannon, the amount of surprise can be represented as a negative logarithm of the event’s probability (unlikely events are surprising), then for a sequence of

${x}_i$

given the preceding tokens, and if, following Shannon, the amount of surprise can be represented as a negative logarithm of the event’s probability (unlikely events are surprising), then for a sequence of

![]() $n$

tokens, the cross-entropy loss is the average of all individual surprises:

$n$

tokens, the cross-entropy loss is the average of all individual surprises:

To identify the most significantly learned phrases, loss on each character was calculated across all documents in the Mao Corpus using a sliding window with a 256-character context. Only 16-character phrases (called “patterns” below) where every character was predicted with a full context were considered, eliminating bias from variable context lengths. For each valid pattern, aggregate loss was computed as the arithmetic mean of its character-level losses. The improvement on each pattern was quantified as the difference between the losses of the pre-trained and the fine-tuned model. All discovered patterns were then sorted in descending order of this loss drop.

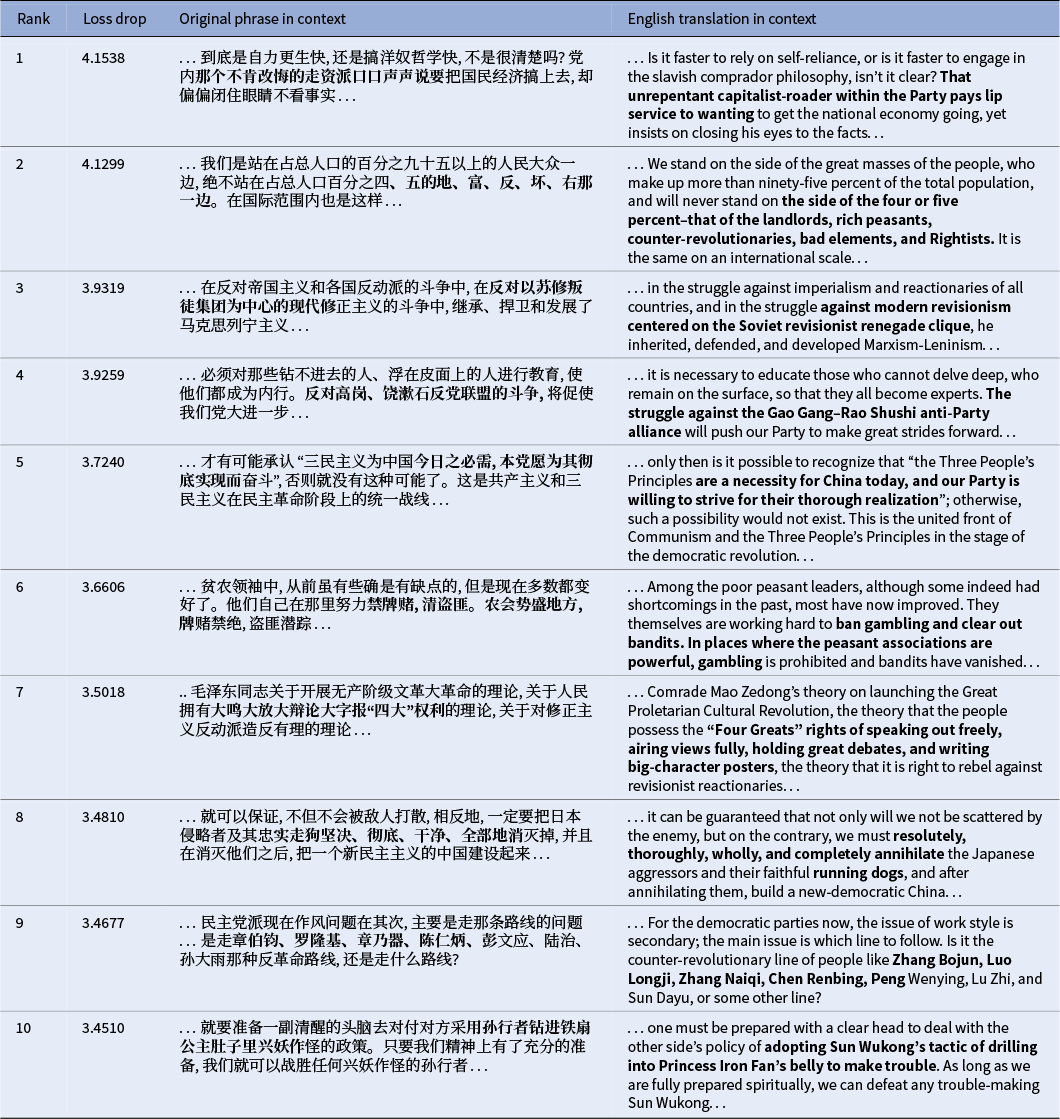

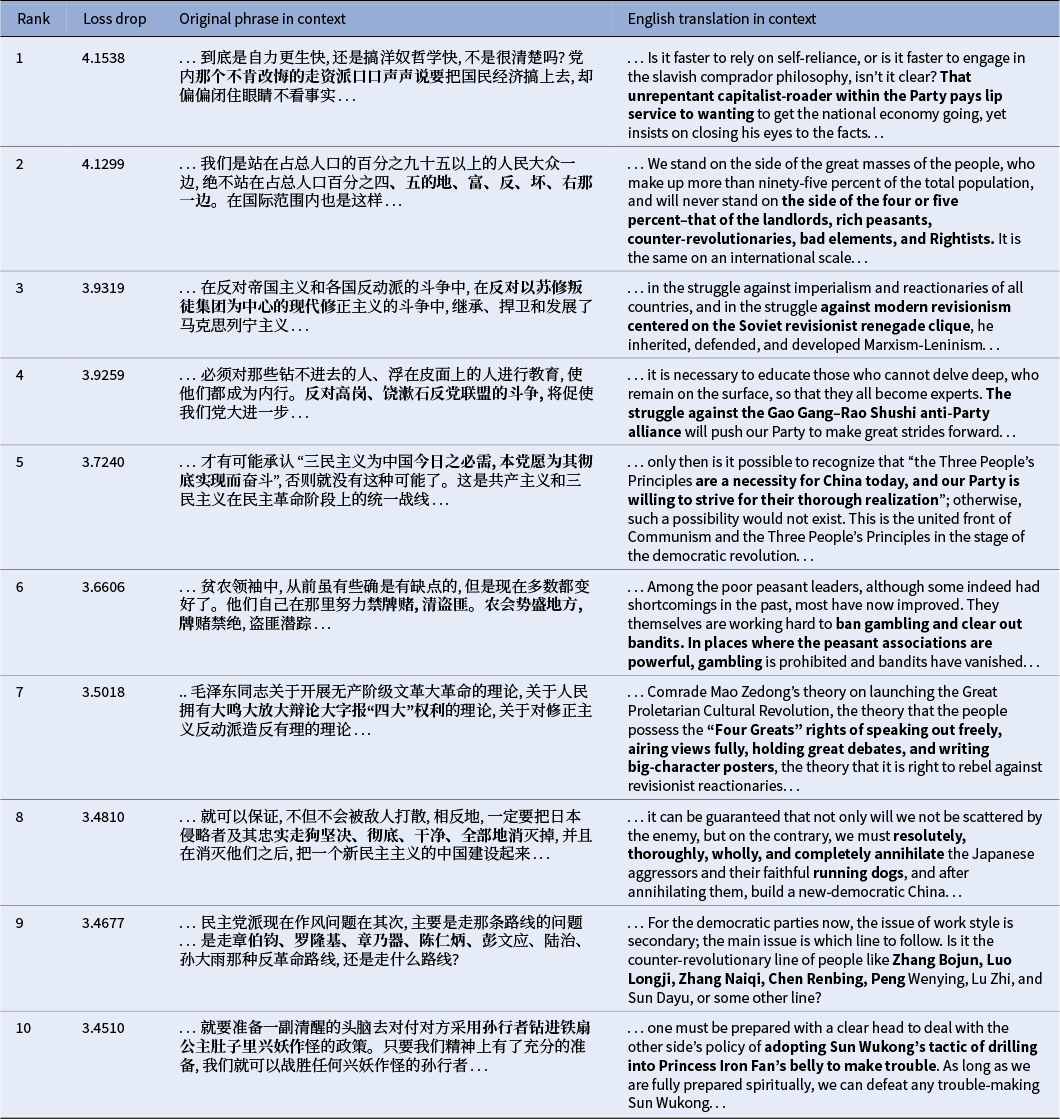

As Tables 2 and 3 show, the most significant gains in predictive certainty occurred on phrases central to the era’s political machinery. The model learned to anticipate the formulaic language used to categorize class adversaries, from the canonical list of “landlords, rich peasants, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements, and Rightists” (Rank 2) to the ubiquitous label for internal party targets: the “unrepentant capitalist-roader” (Rank 1) and the “small handful of capitalist-roaders in authority” (Rank 12). This familiarization extended to highly specific political targets, including internal factions like the “Gao Gang-Rao Shushi anti-Party alliance” (Rank 4), external ideological foes such as the “Soviet revisionist renegade clique” (Rank 3), and personalized lists of enemies, both domestic (“Zhang Bojun, Luo Longji, Zhang Naiqi,” Rank 9) and international (“Chairman Chiang, Syngman Rhee, and Ngo Dinh Diem,” Rank 11). The model also mastered the rigid, legalistic language of policy, such as the principle that the “chief culprits shall be punished, those who were coerced are not prosecuted, and those who perform meritorious service shall be rewarded” (Rank 16) and the formulation to “resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilate” the enemy (Rank 8). Beyond political labeling, the model also captured the discourse’s distinctive rhetorical features, such as Mao’s characteristic use of classical allusions repurposed for political ends, like the phrase “Sun Wukong drilling into Princess Iron Fan’s belly to make trouble” (Rank 10), which co-opts a well-known episode from the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West 西游记 to describe subversive tactics.

Table 2. Top 20 most significantly learned 16-character phrases with context.

Table 3. Top 20 most significantly learned 16-character phrases with context (continued).

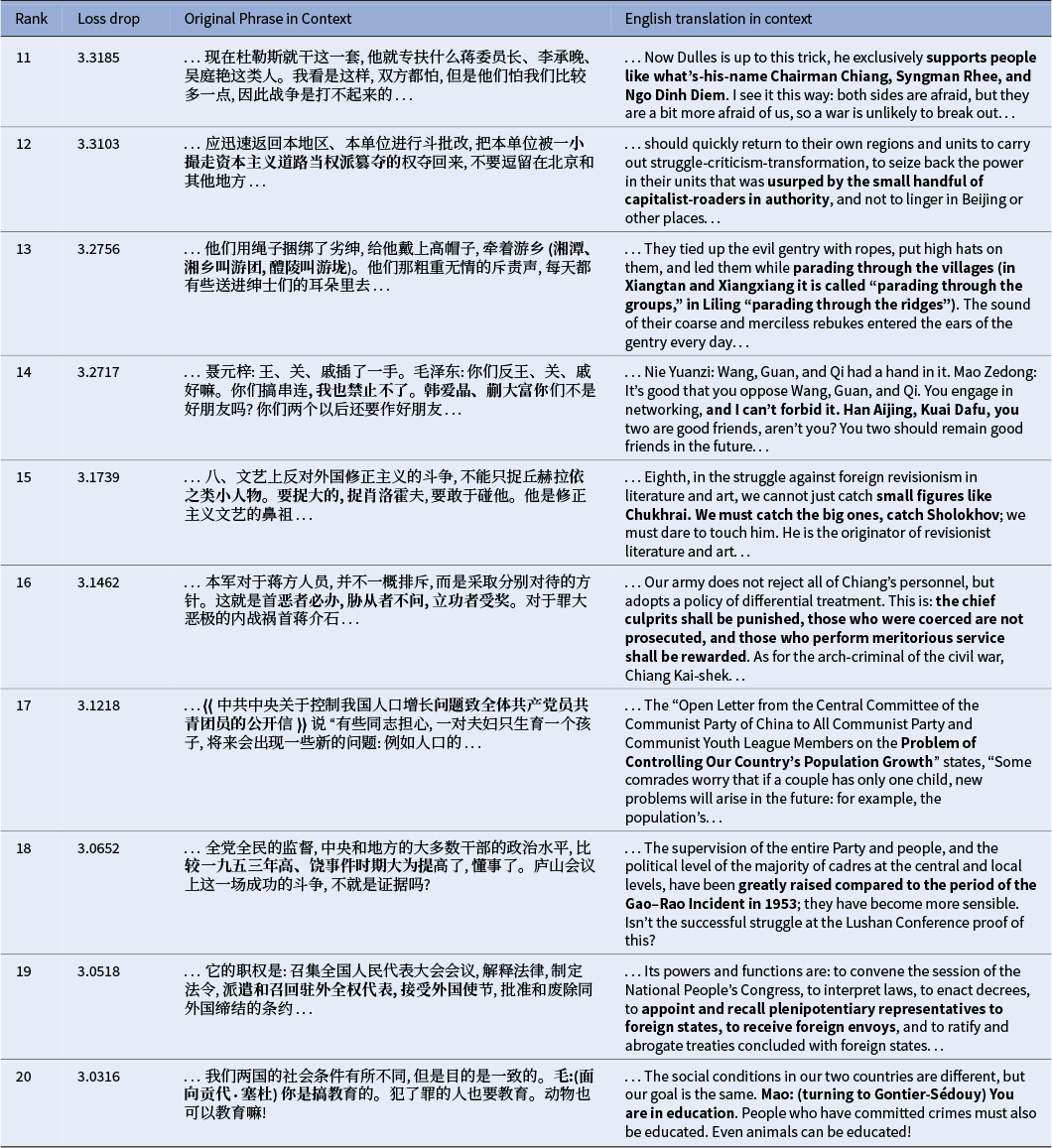

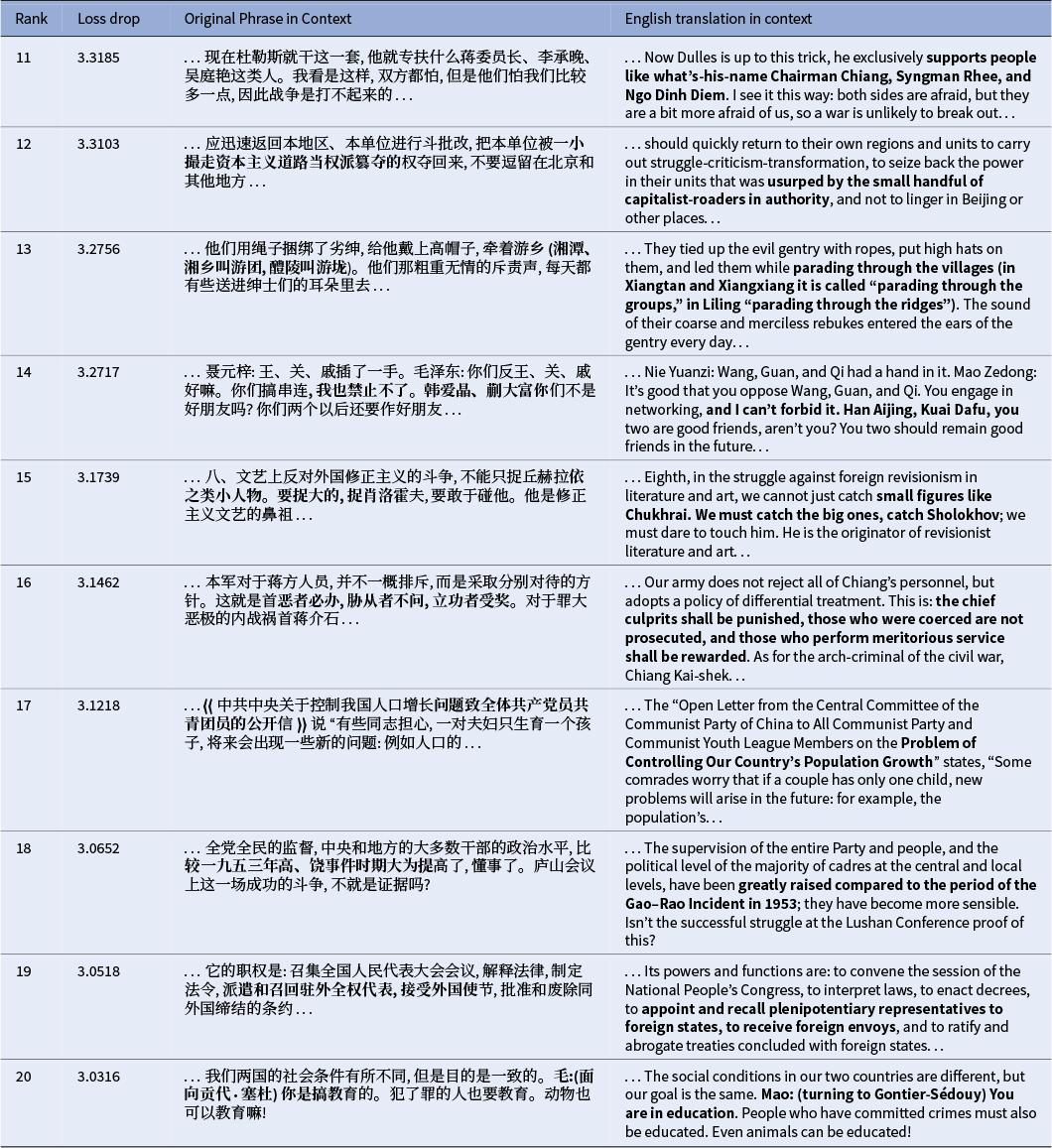

These findings illustrate a process of Shklovskian familiarization, where a powerful idiolect turns slogans, labels, rhetorical strategies and even conversational tics into the automatic discursive background, a process which “replaces things with symbols” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 79). The new symbolic order functioned as political common sense, establishing the terms of legitimacy and effectively rendering the new regime’s authority self-evident. This principle found its ultimate expression in Lin Biao’s declaration that “one sentence of Chairman Mao’s is worth ten thousand of ours,” creating a high-stakes environment where a mere slip of the tongue could have fatal consequences (Schoenhals Reference Schoenhals1992, 19–20). The complementary phenomenon of defamiliarization can be illustrated by comparing the model’s average perplexity on 16-grams and entire documents in both test corpora as it is progressively fine-tuned on Maospeak. As shown in Figure 1, a large difference exists even for the pre-trained model, suggesting that the stylistic gap between the Novels Corpus and the Base Corpus is wider than that between the Mao Corpus and the Base Corpus. As the model specializes in Mao’s text, the more varied, lexically diverse, and structurally complex language of fiction becomes increasingly alien and harder to predict. This trade-off exemplifies what one might call “cognitive overfitting,” a process where becoming an “expert” in a narrow linguistic domain, without access to external stimuli, leads to a quantifiable loss of fluency in another.

Figure 1. Comparison of average perplexities on 16-grams (top) and 1,024-token documents (bottom), as calculated on 1,000 trials with 10,000 samples per trial.

Experiment 2: Microscopic analysis

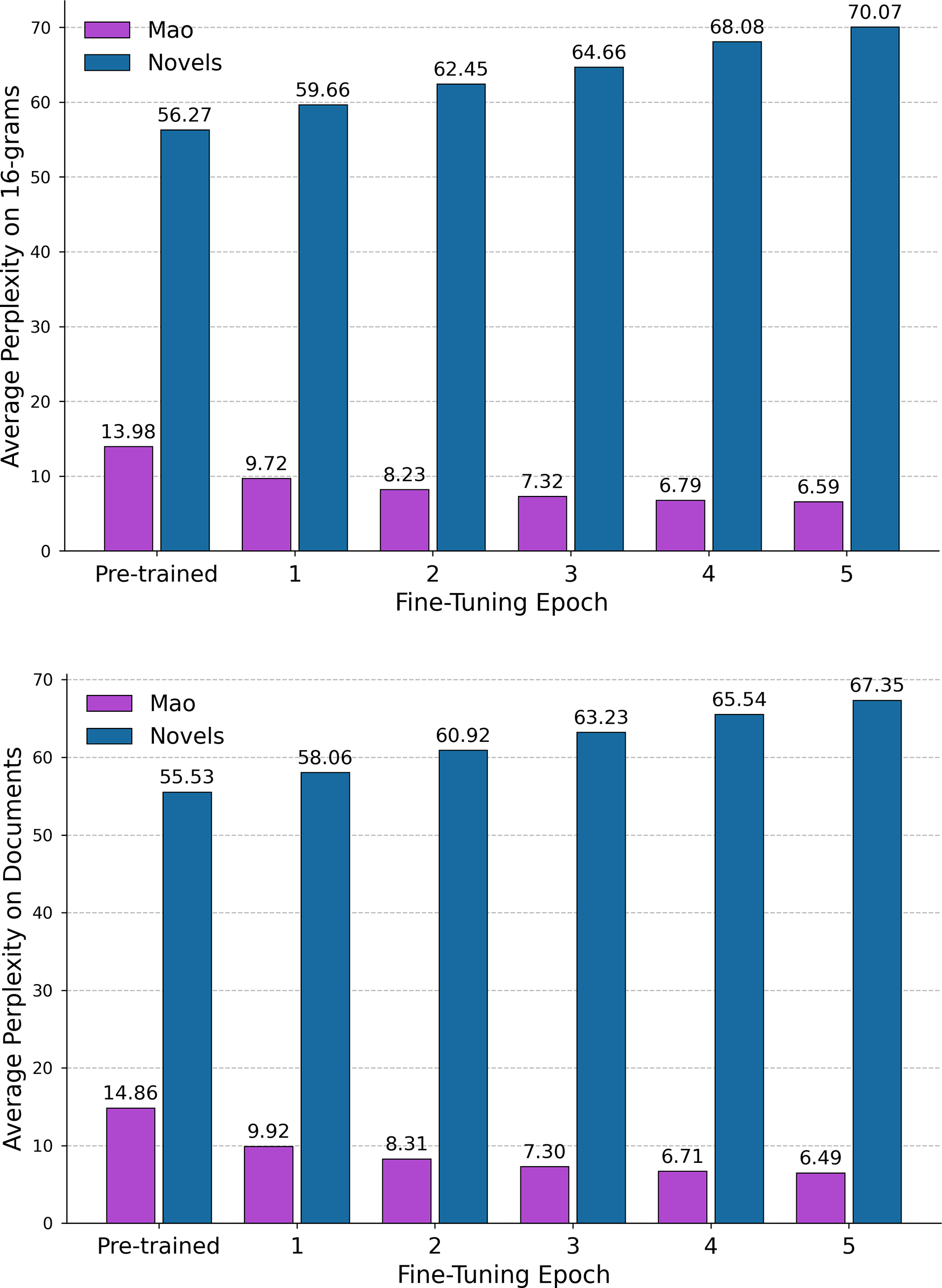

Transitioning from a macroscopic to a microscopic view, the second experiment examines how statistical familiarization manifests at the character level. To this end, I use perplexity, a more interpretable metric calculated by exponentiating the loss defined in Equation (1). A perplexity of 5, for instance, indicates that the model is as uncertain as if it were choosing the next token from five equally likely options. By plotting per-character perplexity for representative passages, we can observe precisely which linguistic elements are initially surprising and how fine-tuning reduces this surprise, effectively “indoctrinating” the model. The figures below illustrate this process, with the yellow line representing the base model’s initial perplexity and the darkening shades of orange and red showing the progressive decrease across five epochs.

All plots exhibit a characteristic “waterfall” pattern: the first character of a key phrase surprises the model, but once this character is revealed, it strongly constrains what can follow, causing subsequent characters to cascade downward with near-certainty. This phenomenon, where the beginning of a sequence is more informative and thus harder to predict than its end, is a general feature of language modeling, whether applied to words (Pimentel, Cotterell, and Roark Reference Pimentel, Cotterell and Roark2021; Pagnoni et al. Reference Pagnoni, Pasunuru, Rodriguez, Che, Nabende and Shutova2025) or chapter breaks (Sun, Thai, and Iyyer Reference Sun, Thai and Iyyer2022). What is distinctive about Maospeak is the length and frequency of such rigid sequences, which severely limit the range of valid continuations.

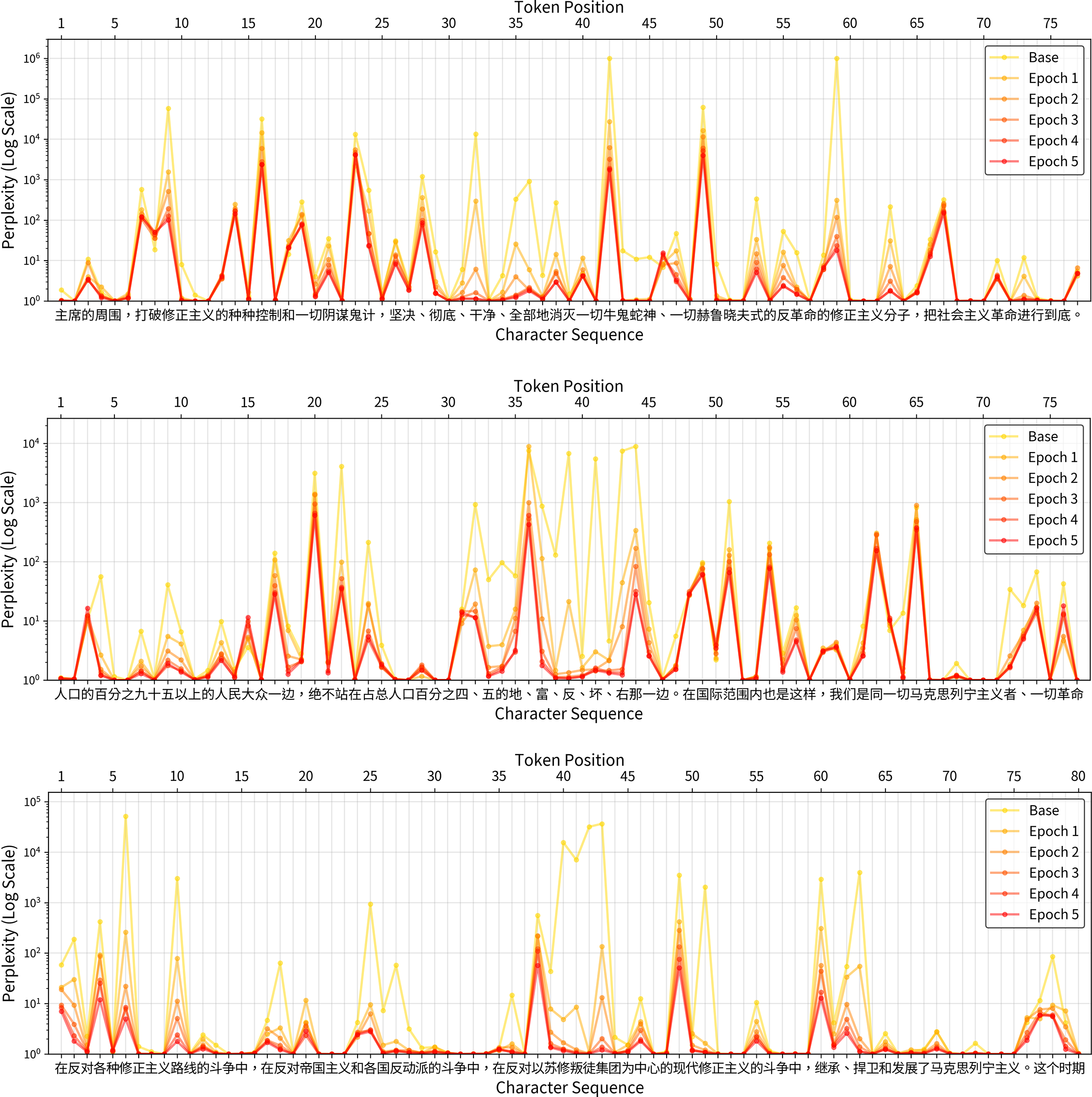

Bearing resemblance to what Shklovsky described as an automatized perception in which objects are recognized “by their initial features” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 79), this characteristic is clearly visible across the three examples (Figure 2). The first passage (top figure) highlights the model’s internalization of characteristic rhetorical structures, featuring the militant formulation 坚决、彻底、干净、全部地消灭掉 (“resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilate,” positions 26–39). The base model is initially very surprised by the sequence of four parallel adverbs. While 坚决 (resolutely) is a common word, the piling on of three more in this escalating sequence is a stylistic hallmark of Maoist rhetoric. The adverbs are followed by an equally characteristic term, niugui sheshen 牛鬼蛇神 (lit. “cow demons and snake spirits”), originally rooted in Buddhist sutras but repurposed by Mao for political agitation and persecution of intellectuals (Lee Reference Lee2014, 49–51). An additional check reveals that this exact rhetorical structure is used widely across the Selected Works, often in nearly identical contexts:

-

• 对于任何敢于反抗的反动派, 必须坚决、彻底、干净、全部地歼灭之 (“As for any reactionaries who dare to resist, they must be resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilated”).

-

• 在此种情况下, 我们命令你们:奋勇前进, 坚决、彻底、干净、全部地歼灭中国境内一切敢于抵抗的国民党反动派 (“In these circumstances, we order you: advance bravely, and resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilate all Kuomintang reactionaries within China who dare to resist”).

-

• 一定要把日本侵略者及其忠实走狗坚决、彻底、干净、全部地消灭掉 (“The Japanese aggressors and their loyal lackeys must be resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilated”).

-

• 也罢, 任何这类的欺骗, 必须坚决、彻底、干净、全部地攻击掉, 决不容许保留其一丝一毫 (“So be it; any such deception must be resolutely, thoroughly, wholly, and completely annihilated, with not the slightest trace allowed to remain”).

The second passage (middle figure) showcases the learning of a canonical list of political labels: 地、富、反、坏、右 (“landlords, rich peasants, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements, and Rightists,” positions 33–39). For the base model, this string of single characters is nonsensical and generates extremely high perplexity. Although the characters are common individually, their specific concatenation as an enumeration of class enemies is unique to Maoism.

The third passage (bottom figure) provides a clear example of the model learning specific ideological jargon, containing the phrase 在反对以苏修叛徒集团为中心的现代修正主义的斗争中 (“in the struggle against modern revisionism centered on the Soviet revisionist renegade clique”). The base model (yellow line) displays massive perplexity spikes on the key term 苏修叛徒集团 (“Soviet revisionist renegade clique,” positions 40–44). This is a highly specific piece of Cold War-era verbiage that is rare in general-purpose text and thus highly surprising. Like in the previous example, with each epoch of fine-tuning, the perplexity on this exact phrase plummets as the model learns to recognize it as a core component of the discourse (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Per-character perplexity plots for three excerpts from the Selected Works of Mao Zedong. The yellow line (Base) shows the perplexity of the pre-trained model, while the lines from orange to red show the decreasing perplexity over five epochs of fine-tuning on the Mao Corpus. The

![]() $x$

-axis displays the Chinese character sequence, and the

$x$

-axis displays the Chinese character sequence, and the

![]() $y$

-axis shows perplexity on a logarithmic scale.

$y$

-axis shows perplexity on a logarithmic scale.

As Ji Fengyuan argues, linguistic engineering was central to Maospeak as a tool of political control (Ji Reference Ji2004). Aligning with a weak interpretation of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, she suggests that language influences thought by making certain cognitive pathways more accessible. The constant repetition of slogans and labels activated associative networks and cognitive schemas tied to concepts like “class struggle” and “proletarian revolution,” aligning public sentiment with ideological goals and providing ready-made justifications for denunciation and violence, effectively automating cruelty. However, Ji also cautions against an Orwellian view of language as a totalizing instrument of domination (Ji Reference Ji2004, 134–143). The low-perplexity canyons are interspersed with less predictable tokens, revealing moments of instability; some grammatical connectives or less common phrasings elicit moderate surprise even after fine-tuning, representing points where Maospeak gives way to the more varied patterns of general language. Conversely, common function words like 的 (of), 在 (at) and 中 (in) consistently show low perplexity from the outset. The initial perplexity spikes are therefore reserved for elements stylistically and ideologically unique to Maospeak, underscoring the method’s ability to isolate the process of familiarization with the specific features of a discourse against the backdrop of general linguistic competence.

Experiment 3:

$N$

-gram entropy

$N$

-gram entropy

The previous experiments suggested that Maospeak operates by relying on a constrained set of high-frequency, low-perplexity phrases, making it more statistically compressible than other forms of discourse. To test this hypothesis quantitatively, I conducted an

![]() $n$

-gram entropy analysis. The experiment compared the Mao Corpus against the Novels Corpus by repeatedly sampling 100,000

$n$

-gram entropy analysis. The experiment compared the Mao Corpus against the Novels Corpus by repeatedly sampling 100,000

![]() $n$

-grams (from

$n$

-grams (from

![]() $n=2$

to

$n=2$

to

![]() $n=16$

) from each and calculating the Shannon entropy. As a measure of predictability, lower entropy signifies a more repetitive text (approaching zero for a text with no variation), while higher entropy indicates greater linguistic variety (maximized in a uniform distribution of

$n=16$

) from each and calculating the Shannon entropy. As a measure of predictability, lower entropy signifies a more repetitive text (approaching zero for a text with no variation), while higher entropy indicates greater linguistic variety (maximized in a uniform distribution of

![]() $n$

-grams).

$n$

-grams).

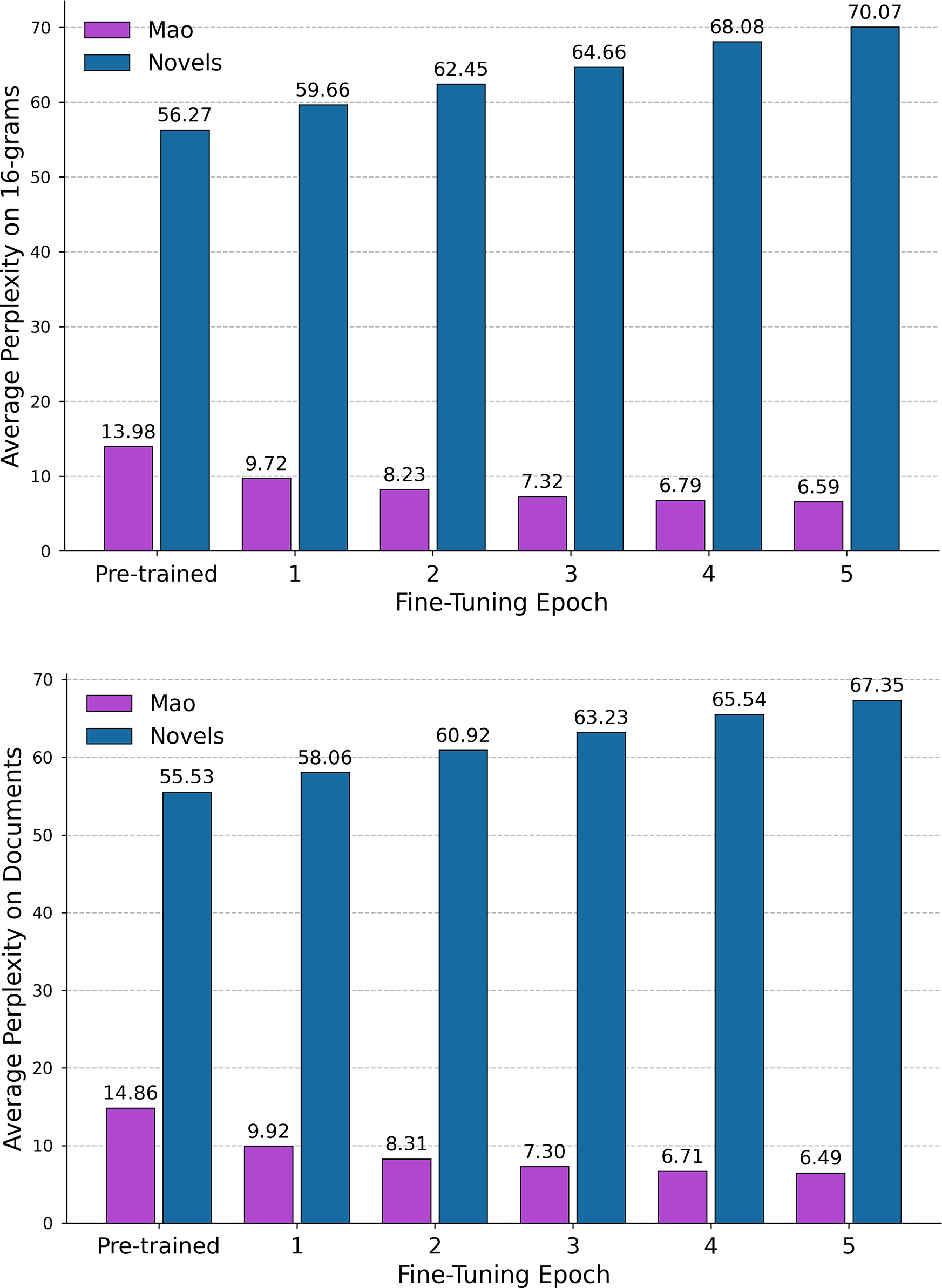

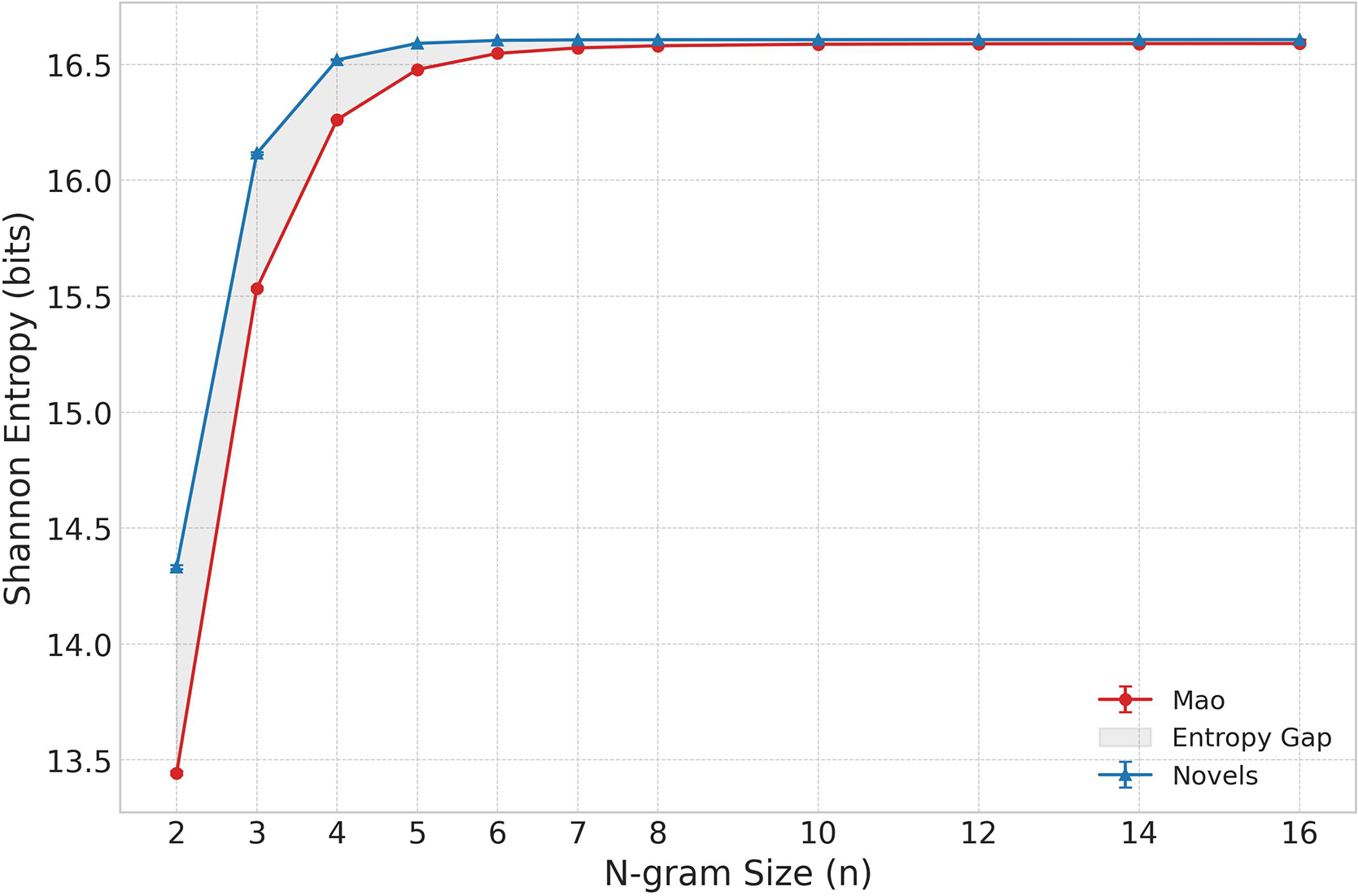

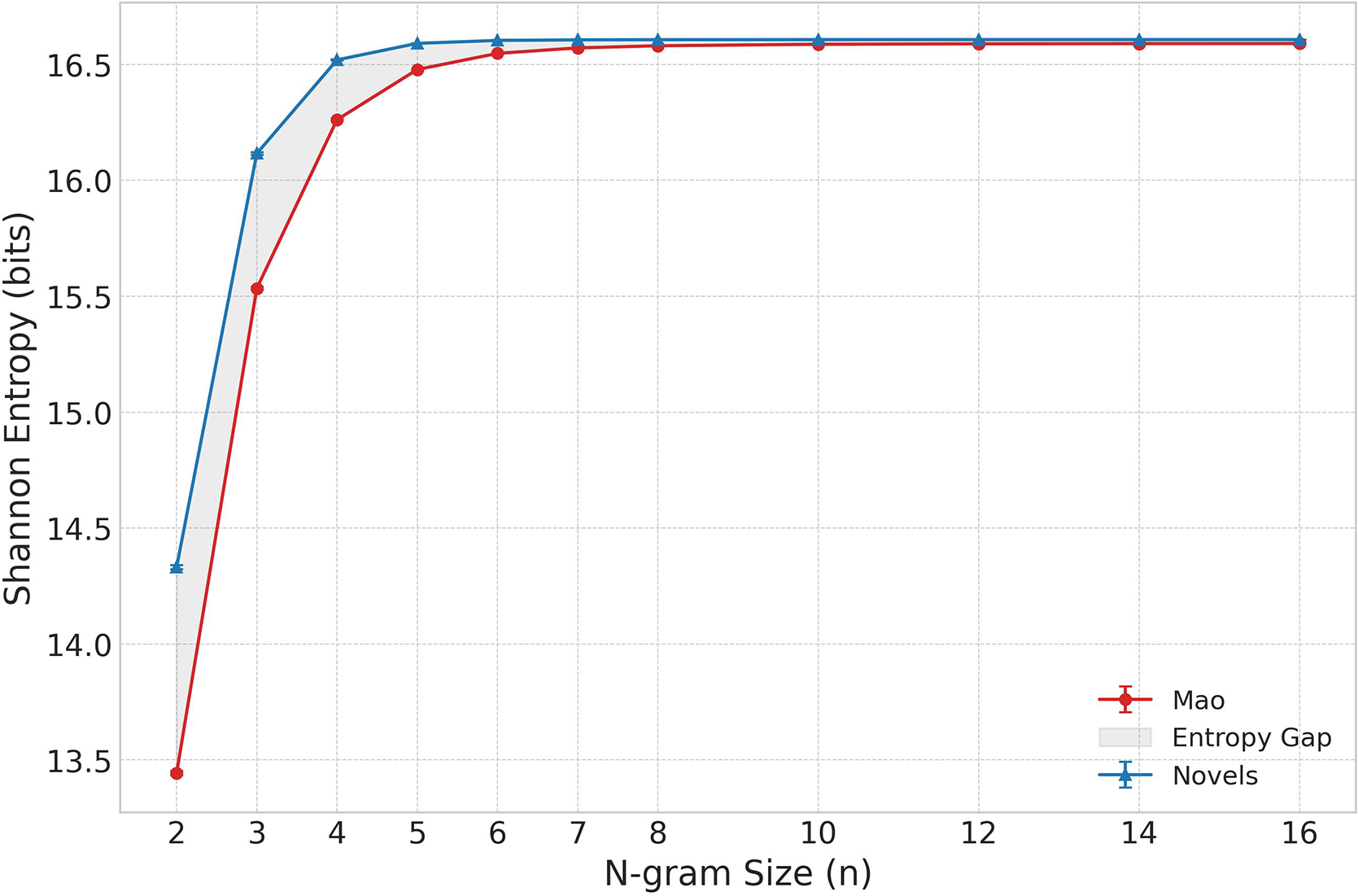

The results (Figure 3) support the initial hypothesis. At every

![]() $n$

-gram size tested, the Mao Corpus exhibited lower entropy than the literary corpus, indicating a more constrained and formulaic linguistic system. The difference was most pronounced for short phrases; for bigrams (

$n$

-gram size tested, the Mao Corpus exhibited lower entropy than the literary corpus, indicating a more constrained and formulaic linguistic system. The difference was most pronounced for short phrases; for bigrams (

![]() $n=2$

), the entropy of the Mao Corpus was 13.442 bits compared to 14.331 for the novels. This entropy gap narrowed as

$n=2$

), the entropy of the Mao Corpus was 13.442 bits compared to 14.331 for the novels. This entropy gap narrowed as

![]() $n$

-gram size increased, which is expected: as

$n$

-gram size increased, which is expected: as

![]() $n$

grows,

$n$

grows,

![]() $n$

-grams become so specific that they are unlikely to repeat within a fixed sample, causing the entropy of both corpora to approach the theoretical maximum for a sample of this size (

$n$

-grams become so specific that they are unlikely to repeat within a fixed sample, causing the entropy of both corpora to approach the theoretical maximum for a sample of this size (

![]() ${\log}_2\left(\mathrm{100,000}\right)\approx 16.6$

bits). The key finding is that the Mao Corpus remains measurably less entropic at smaller

${\log}_2\left(\mathrm{100,000}\right)\approx 16.6$

bits). The key finding is that the Mao Corpus remains measurably less entropic at smaller

![]() $n$

-gram sizes, confirming that its repetitiveness is most evident in its foundational vocabulary and short collocations. The heavy repetition of specific

$n$

-gram sizes, confirming that its repetitiveness is most evident in its foundational vocabulary and short collocations. The heavy repetition of specific

![]() $n$

-grams, resulting in lower entropy, corresponds to the “waterfall” patterns observed in the fine-tuned model’s perplexity scores.

$n$

-grams, resulting in lower entropy, corresponds to the “waterfall” patterns observed in the fine-tuned model’s perplexity scores.

Figure 3. Shannon entropy comparison between Mao’s Selected Works and Chinese novels across different

![]() $n$

-gram sizes on 1,000 trials.

$n$

-gram sizes on 1,000 trials.

Experiment 4: Impact on literature

Finally, I turn to works of literature to examine how the opposing impulses of familiarization and defamiliarization manifest in novels. By examining how three distinct modern Chinese authors engage with, repurpose, or resist predictable linguistic patterns, we can observe how literary art creates meaning through surprise. While familiarization reduces perplexity through repeated exposure, defamiliarization emerges (indirectly) as a by-product of overfitting and (directly) as an aesthetic intervention. Therefore, to explore this phenomenon, the following passages were selected subjectively for their aesthetic and stylistic significance.

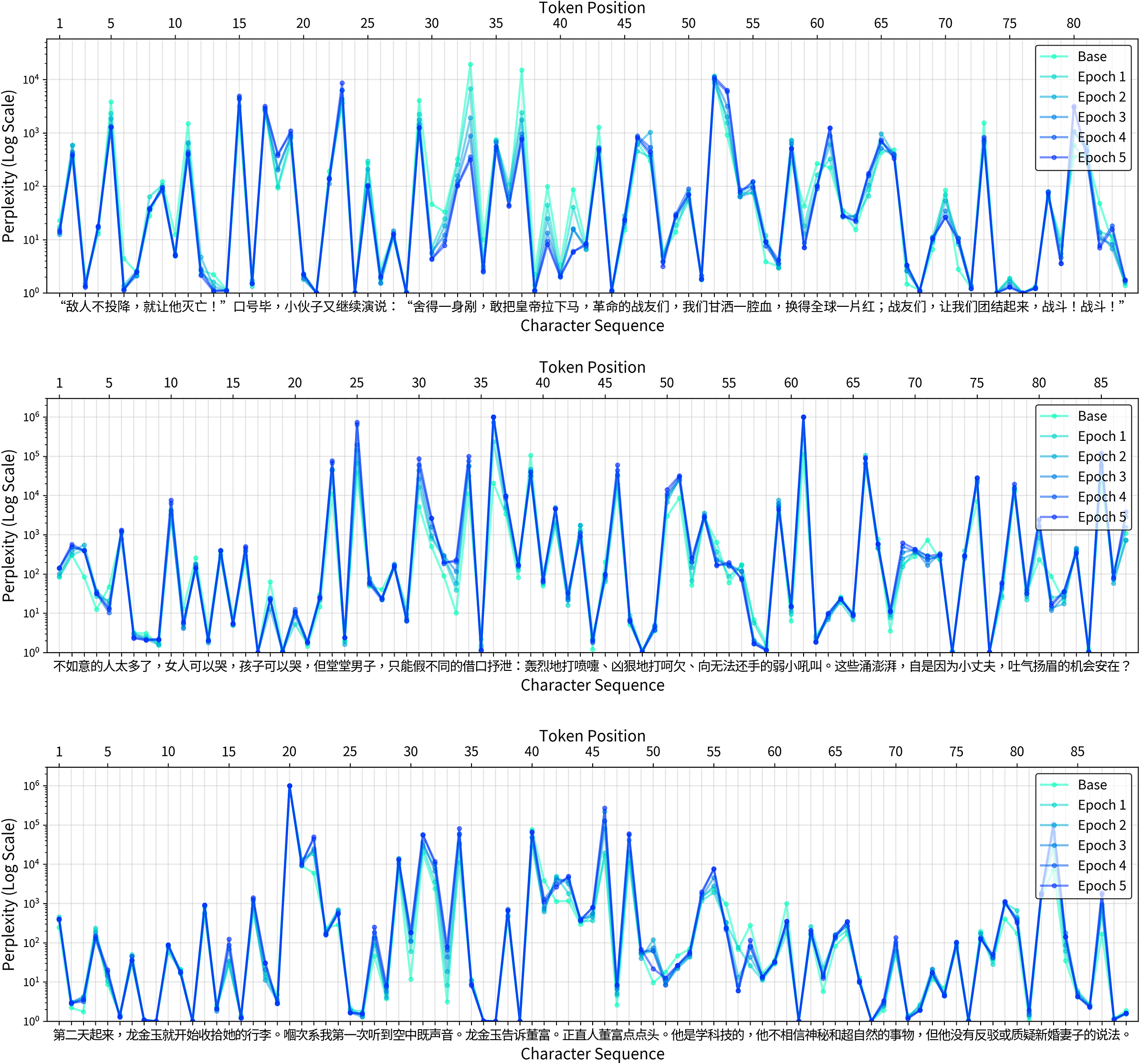

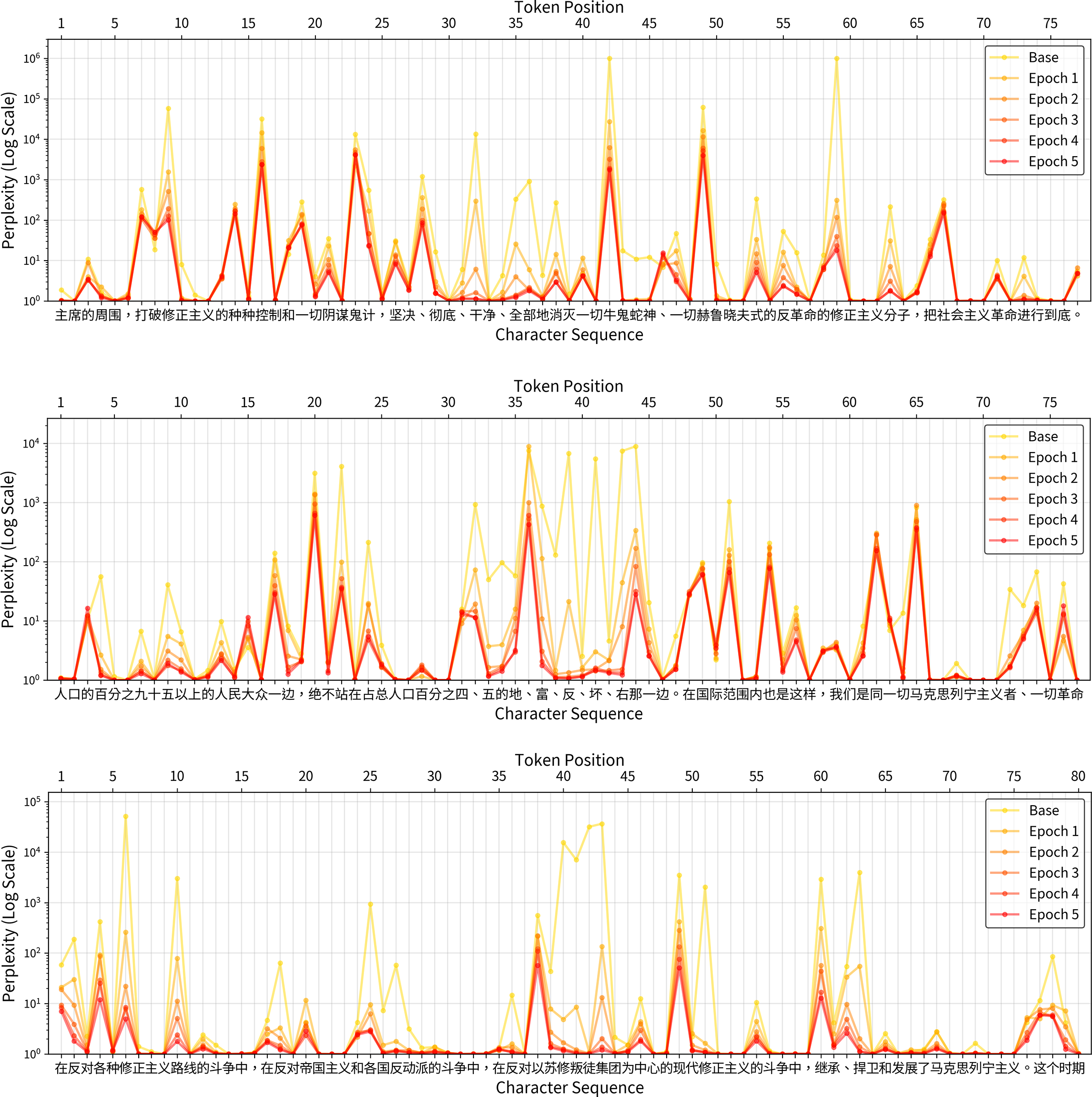

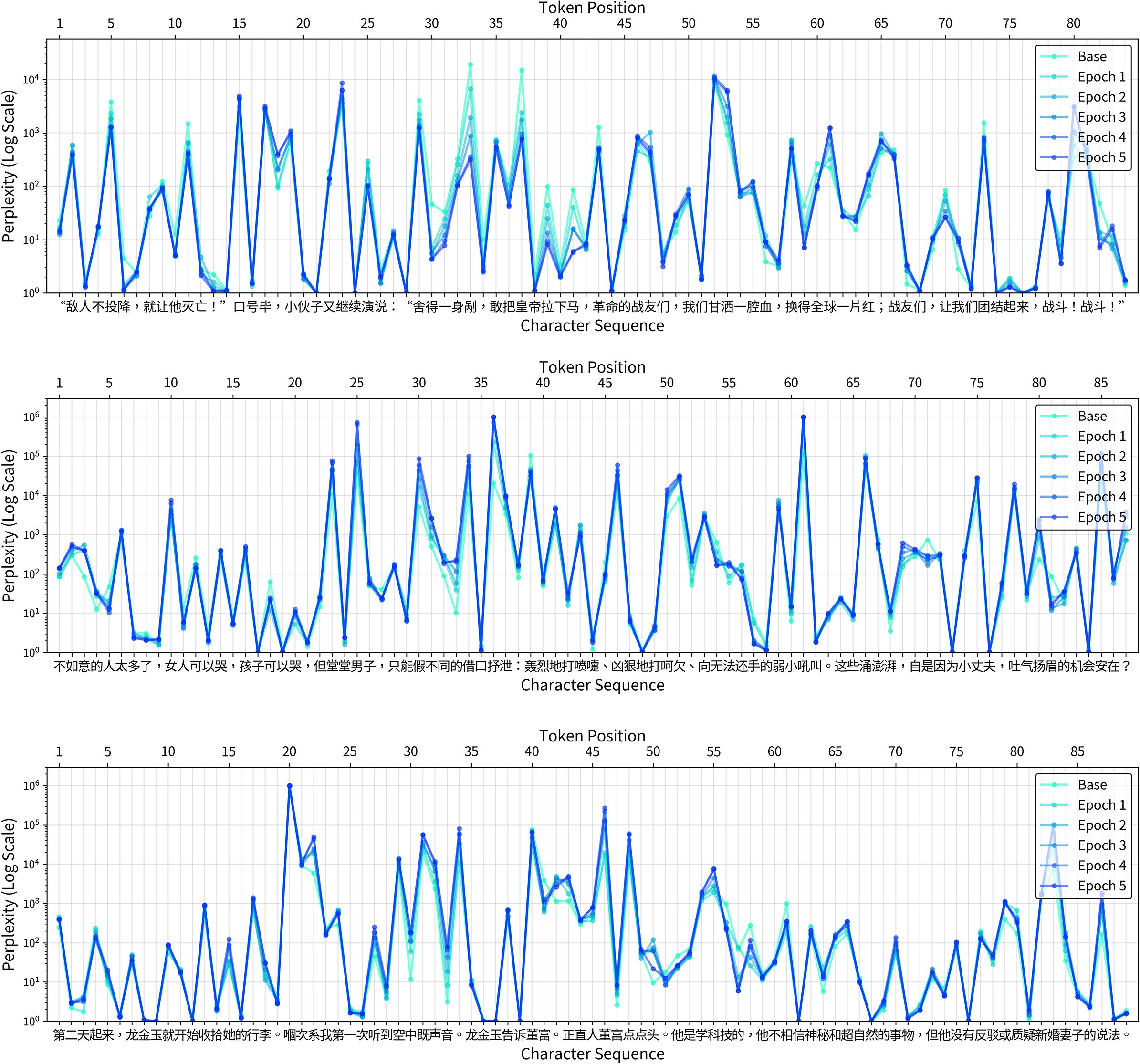

The first passage (Figure 4, Top) comes from a pivotal scene in Chapter 24 of Zhang Wei’s 张炜 (b. 1956) novel The Ancient Ship 古船 (1987). The story is set in Wali, an imagined microcosm of Chinese society which witnesses the vicissitudes of the communist revolution. In the passage, a “red-faced young man,” representing the fervent revolutionary youth, delivers an incendiary speech at a public struggle session, aiming to mobilize the crowd to overthrow the town’s authorities.

Many people recalled the hunger of those years, remembered the waves of devastation, and felt immense anger. Everyone shouted, “It is right to rebel! Down with the die-hard capitalist-roaders!” “If the enemy refuses to surrender, let them perish!” After the slogans, the young man continued his speech: “Those who are not afraid of being cut to a thousand pieces dare to pull the emperor off his horse. Revolutionary comrades, we are ready to shed our blood to make the whole world red. Comrades, let us unite and fight! Fight!”

Figure 4. Per-character perplexity plots for three excerpts from novels. The light blue line (Base) shows the perplexity of the pre-trained model, while the darker lines show the decreasing perplexity over five epochs of fine-tuning on the Mao Corpus. The

![]() $x$

-axis displays the Chinese character sequence, and the

$x$

-axis displays the Chinese character sequence, and the

![]() $y$

-axis shows perplexity on a logarithmic scale. Top: Zhang Wei’s The Ancient Ship; Middle: Lilian Lee’s Farewell My Concubine; Bottom: Dung Kai-cheung’s Works and Creations.

$y$

-axis shows perplexity on a logarithmic scale. Top: Zhang Wei’s The Ancient Ship; Middle: Lilian Lee’s Farewell My Concubine; Bottom: Dung Kai-cheung’s Works and Creations.

不少人想起了那些年的饥饿、想起了一场场蹂躏, 无比愤怒。大家高喊:“造反有理!打倒死不改悔的走资派!” “敌人不投降, 就让他灭亡!” 口号毕, 小伙子又继续演说:“舍得一身剐, 敢把皇帝拉下马, 革命的战友们, 我们甘洒一腔血, 换得全球一片红;战友们, 让我们团结起来, 战斗!战斗!”

Zhang Wei immerses the reader in the linguistic reality of the turbulent era that he himself experienced as a child. The speech is a barrage of Maoist-era slogans showcasing the romanticization of violence (“spill our blood”) and rhythmic chants (“Fight! Fight!”). The most potent phrase is the proverb, “Those who are not afraid of being cut to a thousand pieces dare to pull the emperor off his horse” (positions 29–41), which comes from another Chinese classic, the Dream of the Red Chamber, and which gained new life through Mao’s use. By placing this slogan in the young man’s mouth, Zhang Wei not only highlights the central paradox of the era: the nation’s supreme leader encouraging violent rebellion against all “emperors,” but also masterfully imitates the dominant language style of the period. The Maoist slogan is the only part of the sequence that experienced a significant drop in perplexity (Figure 4, Top). As such, the method was able to identify the Maospeak embedded within the novel.

The second case study examines a passage from Farewell My Concubine 霸王别姬, the seminal 1985 novel by Hong Kong author Lilian Lee 李碧华 (b. 1958). The novel chronicles the tumultuous relationship between two Peking opera performers, Duan Xiaolou and Cheng Dieyi, against the backdrop of China’s political upheavals. The passage in question appears early in the novel, as the protagonists, then young boys, endure the brutal training of an opera troupe. After Xiaolou is caught secretly helping Dieyi ease the pain of a torturous leg-stretching exercise, Master Guan punishes the entire troupe with collective beating. The passage offers a piercing narrative insight into the master’s psychology and the constrained nature of masculinity that defines the novel’s world.

There are too many people whose lives are not as they wish. Women can cry, and children can cry, but a dignified man can only vent through different feigned excuses: a heroic sneeze, a ferocious yawn, a roar at the weak and small who cannot fight back. All this surging and churning, is it not because for a petty man, the chance to feel proud and elated is nowhere to be found?

不如意的人太多了, 女人可以哭, 孩子可以哭, 但堂堂男子, 只能假不同的借口抒泄:轰烈地打喷嚏、凶狠地打哈欠、向无法还手的弱小吼叫。这些汹涌澎湃, 自是因为小丈夫, 吐气扬眉机会安在?

The perplexity distribution for this passage (Figure 4, Middle) shows how literary language creates its effects through moments of surprise. The highest perplexity spikes occur on the creative juxtapositions: 凶狠地打哈欠 (“a ferocious yawn,” 45–51) or 向… 弱小吼叫 (“to roar at the weak,” 59–62). These phrases elicit high perplexity likely because figurative language is less probable than literal phrases (Pedinotti et al. Reference Pedinotti, Di Palma, Cerini, Bastings, Belinkov and Dupoux2021). Even more telling is the passage’s use of pre-modern and classical Chinese phrasings, which become increasingly unfamiliar to the model as it is fine-tuned on Maospeak. For instance, the adjective 堂堂 in 堂堂男子 (“dignified man”) is a formal, literary term for “imposing” or “grand” that ironically evokes here a traditional sense of masculinity, a register alien to the functional dialect of Maospeak. Likewise, the final question, 机会安在 (lit. “the chance is where?”), uses the character 安 in its classical function as an interrogative pronoun (“where”), a usage largely replaced by words like 哪里 in modern vernacular and mostly absent from the Mao Corpus. The fine-tuned model finds both of these literary phrasings even more anomalous than it did initially, causing their perplexity to increase.

These high-entropy word choices, which slow down the narrative, are set against a backdrop of linguistic convention (Bizzoni, Feldkamp, and Nielbo Reference Bizzoni, Feldkamp and Nielbo2024) and narrative scaffolding that glues together the surprising tokens. The passage opens with just such a phrase: 不如意的人太多了 (“too many people whose lives are not as they wish”). This is a low-perplexity, almost proverbial, statement that eases the reader into the scene by establishing a familiar emotional context. This kind of predictable framing anchors the unique description of events in familiar literary conventions, signaling the narrative’s fictional nature and making the subsequent, high-perplexity surprises more effective.

The final case study focuses on Hong Kong writer Dung Kai-cheung 董启章 (b. 1967), known for his postmodern narratives merging memory, technology, and urban space. A distinctive feature of Dung’s style is his interspersion of standard written Chinese with Cantonese, the non-normative language spoken in Guangdong, Hong Kong, and numerous overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia and North America. His novel Works and Creations: As Vivid As Real 天工开物·栩栩如真 (2005) interweaves fictional and autobiographical storylines. In the autobiographical part, Dung’s grandmother, Lung Gam Juk, confides in her husband a painful memory of separation from her brother, which is when she first realized her extraordinary ability to hear radio waves:

The next day, Lung Gam Juk began packing her luggage. That was the first time I heard the sound in the air. Lung Gam Juk told Dung Fu. The upright Dung Fu nodded. He studied electronics and didn’t believe in esoteric or supernatural things, but he didn’t argue or question his newly-wed wife’s words.

第二天起来, 龙金玉就开始收拾她的行李。嗰次系我第一次听到空中既声音。龙金玉告诉董富。正直人董富点点头。他是学科技的, 他不相信神秘和超自然的事物, 但他没有反驳或质疑新婚妻子的说法。

This seemingly straightforward scene blends free indirect speech, unmarked direct quotations, and internal monologue. The perplexity plot (Figure 4, Bottom) shows how Cantonese terms like 嗰 (“that”), 系 (“to be”) and 既 (“of”) disrupt the perplexity arc. The surprise is enhanced because the Cantonese statement is not announced with quotation marks, making an abrupt switch from the narrator’s to the character’s voice. Meanwhile, novel-specific terms like “upright” (正直人) and character names challenge the model’s predictive capacities, providing a clear example of what empirical literary studies call “foregrounding” (Peer et al. Reference Peer, Sopčák, Castiglione, Kuiken and Jacobs2021). As such, the heteroglossic novel “puts the brakes on perception” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 94), challenging both human and machine readers. Written Cantonese contains many characters that are absent from standard written Chinese but are essential to transcribe words used by Cantonese speakers on a daily basis (Snow Reference Snow2004). Many Hong Kong writers use these non-standard characters to signal the cultural distinctiveness of their work, and some go as far as to write entire novels in Cantonese. On a technical level, Cantonese expressions resist prediction because they are underrepresented in training data, highlighting the normative assumptions underlying most Chinese LLMs (Xiang et al. Reference Xiang, Chersoni and Li2025; Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Chen, Chen, Chiruzzo, Ritter and Wang2025).

This use of a topolect as a defamiliarizing device is a classic literary strategy. For language to be poetic, Shklovsky argued after Aristotle, it ought to have “the character of the foreign” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 94). He observed that when a literary establishment exhausts the standard language, it turns to regional vernaculars, and so “folk language and literary language have changed places” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 95). Although Cantonese can boast significantly richer cultural heritage than “modern standard Chinese,” Dung’s insertion of Cantonese speech operates through similar mechanisms. By deliberately disrupting the automatized perception of written Chinese, the author forces readers—or at least those accustomed only to the standard tongue—to encounter the cultural specificity of his text.

Discussion

The dialectic of familiarity and surprise

Literary critics since Shklovsky have often focused on defamiliarization as the primary function of art, dismissing the familiar as “worn-out rhetoric” and “jaded conventions” (Resseguie Reference Resseguie1991). This perspective ignores the fact that no element of language is inherently familiar or conventional; such qualities emerge only through repeated exposure and cultural reinforcement. The present study has thus approached style not as a static property of a text but as a dynamic, processual engagement between a reader and a text unfolding in time.

The stylometric analysis of Maospeak offers a case study in how familiarity might be achieved in language. The relentless reinforcement of its phraseology creates the “economy of mental effort” that Shklovsky critiqued and which, as cognitive stylistician Reuven Tsur explains, fosters a “psychological atmosphere of control, certainty, and patent purpose” (Tsur Reference Tsur2008, 20). This effect is achieved by radically collapsing the probabilistic space of expression around a few high-stakes binaries – class struggle, revolution versus counter-revolution, East versus West – making dissent not only politically dangerous but also lexically improbable. In a similar vein, the institutional promotion of a single “standard Chinese” marginalizes non-normative languages. Faced with such top-down regulation, cognitive studies in the humanities have focused on the bottom-up “violence against cognitive processes” (Tsur Reference Tsur2008, 4) – the ways literature strikes back and interferes with habituated perception.

Yet the above experiments also indicate that a singular focus on defamiliarization overlooks the crucial role played by the familiar in grounding perception. Recent years have witnessed a renewed interest in the “eventness” of narratives (Baldassano et al. Reference Baldassano, Chen and Zadbood2017; Sims, Park, and Bamman Reference Sims, Park and Bamman2019; Gius and Vauth Reference Gius and Vauth2022), but singular events are meaningful only within a sea of stability where “things do not happen all the time” (Sayeau Reference Sayeau and Bulson2018). This principle applies directly to perplexity: a sequence of completely random characters would certainly be unfamiliar and perplexing, but it would not defamiliarize. Wendy O’Brien suggests that, in addition to its defamiliarizing function, fiction can also “make the familiar and the ordinary familiar again” (O’Brien Reference O’Brien and Tymieniecka2007). This important restorative function of fiction lies in its ability to re-establish meaning by arranging overwhelming events into a temporal sequence, allowing the reader to “adapt to her new history” and “tell the time” again (O’Brien Reference O’Brien and Tymieniecka2007).

In this context, Patrick Colm Hogan’s notion of “non-anomalous surprise” offers a compelling theoretical alternative that might account for the findings of this project (Hogan Reference Hogan2016, 20–36). Faced with the question whether aesthetic pleasure is a function of predictability or surprise, Hogan differentiates between focal and non-focal aspects of the aesthetic target: “focal aspects would be pleasurable to the degree that they foster non-anomalous surprise whereas non-focal aspects would be valued primarily for predictability” (Hogan Reference Hogan2016, 27). In Hogan’s cognitive framework, which echoes the figure-ground hypothesis of Gestalt psychology, having a predictable part of a work would be valuable even if the main aesthetic pleasure comes from the unpredictability of another part. He speculates that in music, “aesthetic pleasure results from the predictability of the non-focally processed rhythmic cycles in combination with the non-anomalous surprise of the focally processed melody” (Hogan Reference Hogan2016, 27). We can observe a similar phenomenon in novelistic texts, where the familiar narrative rhythms are disrupted with high-perplexity tokens, leading to rapid oscillations in perplexity arcs. Although such tokens are surprising, they are not anomalous, because the reader is able to recognize their meaning and function in the sequence once they occur.

Redefining style as a cognitive signature

The tension between a predictable ground and a surprising figure also allows us to redefine style in cognitive and probabilistic terms and to move beyond the prevailing definition of style as something that affects only how information is conveyed. This model underpins computational style transfer (Gatys, Ecker, and Bethge Reference Gatys, Ecker and Bethge2016; Shen et al. Reference Shen, Lei and Barzilay2017; Jin et al. Reference Jin, Jin and Hu2022), which can render a family photo in van Gogh’s style or rewrite a hamburger description in Du Fu’s verse. Instead, my project supports the Formalist refusal of the form-content separation, suggesting that stylistic differences are better understood as “varying relationships between highly categorized and pre-categorial information” (Tsur Reference Tsur2008, 20). From this perspective, style is the signature of how a text manages historically specific readerly expectations by orchestrating the interplay between clear-cut figures and their low-differentiated backgrounds. A meeting of two characters may provide a schematic foil for a surprising dialogue; the irruption of Cantonese, as seen in Dung Kai-cheung’s work, challenges the presumed naturalness of standard Chinese (Yeung Reference Yeung2023). Maospeak operates more insidiously, pushing highly categorized political abstractions into the non-focal spectrum until the ideological discourse becomes a subconscious, low-perplexity rhythm.

From an LLM perspective, this model of style is directly measurable. The “norm” is the set of regularities learned during training; any perplexity above 1 indicates a choice. To speak with minimum perplexity would require quoting a memorized dataset without variation, a scenario glimpsed in the institutionalized forms of Maospeak which elevated self-similarity to an unprecedented degree. Consider this excerpt from Mao’s seminal speech “Serve the People”:

To die for the People’s interests is weightier than Mount Tai; to die in service of fascists, or for those who exploit and oppress the People, is lighter than a feather. Comrade Zhang Side died for the People’s interests, and his death was weightier than Mount Tai.

为人民利益而死, 就比泰山还重;替法西斯卖力, 替剥削人民和压迫人民的人去死, 就比鸿毛还轻。张思德同志是为人民利益而死的, 他的死是比泰山还要重的。

Such rigid syllogisms reinforce a global discourse through local, fractal-like iterations (Drożdż et al. Reference Drożdż, Oświęcimka and Kulig2016). Literature, by contrast, is not a self-perpetuating dataset but a dynamic interplay of fuzzy quotations and their creative recontextualizations, which together generate the “different ways of de-automatizing things” (Shklovsky Reference Shklovsky and Berlina2017, 81). While a recent study argues for the presence of fractality in Chinese prose (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Gunn and Youssef2023), this finding is based on sentence length variability rather than semantics. Curiously, the authors do note that “Maoist-era novels of socialist realism depicting rural China are among the narratives with the highest Hurst values [indicating high fractality]” (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Gunn and Youssef2023, 609). The present study has argued that literature resists the self-similar, low-perplexity patterns of engineered languages, but further research is needed to explore this tension. In particular, we have noted that Maospeak itself draws heavily upon literary quotations; it is the cognitive effect of repetition that differentiates it from literature. Where literature recontextualizes a quotation to defamiliarize and provoke thought, Maospeak repeats it to familiarize and ultimately foreclose it.

Perplexity arcs and emotional arcs

Finally, the focus on the unfolding of historically grounded readerly experience aligns this project with the analysis of narrative “emotional arcs” (Teodorescu and Mohammad Reference Teodorescu, Mohammad, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023), a concept pioneered by the novelist Kurt Vonnegut, who proposed that stories could be plotted on a simple graph of fortune against time, identifying fundamental shapes like the “Man in a Hole” archetype. This intuitive idea was later operationalized by a wave of digital humanities research, which applied quantitative methods like stylometry and lexicon-based sentiment analysis to large corpora of novels, computationally identifying a set of recurring emotional trajectories and character patterns (Burrows Reference Burrows1987; Jockers Reference Jockers2013; Reagan et al. Reference Reagan, Mitchell and Kiley2016; Rebora Reference Rebora2023). However, this methodology has been the subject of critical refinement. For example, in her book The Shapes of Stories, Katherine Elkins argues that scholars must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach, demonstrating that different sentiment analysis models are required to capture the unique “affective fingerprint” of each narrative (Elkins Reference Elkins2022). Elkins advocates for an ensemble, critic-in-the-loop methodology that prioritizes the singular patterns of individual texts over generalized shapes.

The “perplexity arc” proposed in this study operates on a parallel, yet distinct, cognitive axis. A moment of emotional intensity might be rendered in simple, low-perplexity language to create a blunt effect. Conversely, a seemingly neutral description could be delivered in highly complex, high-perplexity prose, signaling its importance. The present approach is not immune to the critiques leveled against its affective counterpart; a single focus on local, token-level surprise risks overlooking how meaning and affect are constructed over larger spans of text. Shklovsky’s examples, for instance, operate mostly at the macro-level of plot and perception, such as Tolstoy’s use of a horse as a narrator. In this article, I have suggested that such disruptions can be measured at the most fundamental level (the moment-to-moment encounter with language) and that such micro-level surprises are the building blocks of larger-scale formal effects. A crucial next step is to bridge these scales, moving from phrases to sentences and beyond, an accumulation of linguistic contexts that has shown parallels in both artificial and human cognition (Tikochinski et al. Reference Tikochinski, Goldstein and Meiri2025). By integrating these multiple cognitive dimensions and analytical scales, future work can create a far richer, multi-layered model of the reading experience that maps the complex interplay between emotional valence, cognitive surprise and the hierarchical structuring of literary meaning.

Conclusion

More than a century after Shklovsky’s “Art as Device” laid the groundwork for theories from New Criticism to narratology (Wake Reference Wake, Malpas and Wake2013), his focus on defamiliarization continues to inspire literary studies. As complementary perspectives have noted, the aesthetic role of “familiarization” is equally crucial (O’Brien Reference O’Brien and Tymieniecka2007; Vos Reference Vos, Bayraktar and Godioli2024). The present study has argued that it is in between these two impulses that the Formalist project joins hands with information theory. Each style possesses a distinct cognitive signature, a specific strategy for managing a reader’s predictive processing by balancing familiar grounding with moments of perplexity.

Cognitive stylistics explores the link between textual structure and perceived effect (Tsur Reference Tsur2008), while computational stylometry measures textual patterns (Argamon, Burns, and Dubnov Reference Argamon, Burns and Dubnov2010). By integrating these fields through the predictive lens of LLMs, I propose “cognitive stylometry” as a new mode of literary inquiry that turns the common critique of language models as “glorified autocomplete” into a methodological advantage and a new viewpoint. In a world where “everything is predictable” (Chivers Reference Chivers2024), literature can still teach us something about freedom and choice.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the results are contingent on the chosen GPT-2 style architecture and the Fineweb-Edu corpus, which serves as the “neutral” baseline of modern Chinese. A different, perhaps larger, model or a baseline corpus with a different composition (e.g., one richer in classical literature or web-based text) would inevitably alter the specific perplexity values and could shift the perceived boundary between the familiar and the unfamiliar. Furthermore, the fixed context window of 256 tokens imposes an artificial boundary on the model’s predictive horizon, which cannot fully replicate the long-term memory and rich contextual understanding of a human reader. The very fact that each literary excerpt in this study required a brief prose introduction highlights this gap. While there is no scholarly consensus on the optimal context length for such comparisons (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Wang and Liu2024), and internal tests with different window sizes confirmed the overall trends and identified patterns, this parameter remains a significant variable.

Second, it bears repeating that the study’s core analogy, which equates perplexity with cognitive surprise, is a deliberate simplification. Human reading involves embodied cognition, emotional resonance and multi-modal knowledge that the LLMs employed in this study lack, just as fine-tuning only approximates the socio-historical saturation of Maospeak. New model architectures and human-centered artificial intelligence might reduce these gaps, allowing scholars to better model historical contexts and circumstances.

Finally, the selected hyperparameters, while supported by local testing, necessarily impact the final results. Notably the fine-tuning learning rate and the gradient norm clipping influence the learning process and, if not carefully adjusted, might lead to “catastrophic forgetting” of the base model. An alternative setting would be to progressively contaminate the training dataset and train a series of different models, thus bypassing the fine-tuning stage. This approach is less practical than the one adopted in this study, however, as fine-tuning is less computationally expensive than training entire models from scratch.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and questions. Special thanks are also extended to the organizers and participants of the NLP4DH 2023 conference.

Data availability statement

The corresponding code and training settings can be found in the online repository (https://github.com/mcjkurz/cogstyl).

Author contributions

Maciej Kurzynski — Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

None.

Disclosure of use of AI tools

Claude Opus 4 was used to create the figures included in this document and to generate a Streamlit application for easier perusal of identified patterns.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/chr.2025.10020.

Rapid Responses

No Rapid Responses have been published for this article.