In 331 bce, on a limestone ridge bounded by Nile-fed Lake Mareotis to the south and the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Alexander the Great founded the Egyptian city that was to bear his name.309 Alexandria was conceived as a Greek city, and so it remained throughout the period of Roman rule. Poised on the edge of Egypt, it became known as “Alexandria ad Aegyptum,” Alexandria by (or near) Egypt. As the capital of Ptolemaic Egypt and the seat of the prefect after Egypt's conquest by Rome, Alexandria remained culturally aloof from other polities of Graeco-Roman Egypt, and its tombs reflect its special status.

Newly forged, Alexandria was a fabricated polity.310 Constitutionally fashioned as a Greek polis, it claimed the political machinery integral to a democracy despite the autocratic reality of regal power.311 The city boasted a citizen body (the demos), a civic law code, an assembly (ecclesia), a council (boule), a board of magistrates (prytanies), and a body of elders (gerousia),312 and its citizens were accorded a fictive past with their division – modeled on Athens – into phyles, demes, and phratries.313 Upon his conquest of Egypt, Augustus reorganized the demes,314 and under Roman rule, the tribes (phyles) were renamed,315 but throughout the period of Roman rule, tribal and deme membership still constituted the basis for Alexandrian citizenship. Alexandrian citizenship, as a hereditary institution, thus played a defining role in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Alexandrian citizens (as those of the Greek cities of Ptolemais and Naukratis and, after its foundation by Hadrian, Antinoöpolis) enjoyed special economic and legal privileges. They were, for example, exempt from taxes that burdened other inhabitants of Roman Egypt and that also acted as a social determinative to designate the others’ lower status.316 Most significant, however, was that until the third century ce, Alexandrian citizens were the only non-Roman inhabitants of Egypt who could claim the prestige of Roman citizenship.317 These privileges, which positioned the citizens of Alexandria as a superior social class, permitted Alexandrian tombs to develop differently from other tombs in Graeco-Roman Egypt, on the one hand, and, on the other, were keenly recognized by Greek inhabitants of the Egyptian chora, who expressed their conversance with the social hierarchy in the decoration of their own monumental tombs as discussed in Chapter Three.

In addition to its Greek system of governance, Alexandria offered a Classically inspired physical presence. Laid out on a Greek Hippodamian plan,318 the city contained the Greek elements of an agora (Arr. An. 3.1.5), a theater, a council hall (bouleuterion),319 law courts, a gymnasium, and, by the Roman period, a hippodrome and an armory (Philo, Flacc. 92), as well as temples to Greek gods (Strabo 17.1.9–10). Though Rome's conquest of Egypt changed both the political administration of the polity and the governance of Alexandria,320 and the ensuing centuries of Roman rule added monuments that provided a contemporary cast to the urban landscape of the city, the language, ethnic priority, intellectual life, and identity of the city remained culturally Greek.321 Its famed library founded under Ptolemy I Soter (305/4–283 bce) drew intellectuals to the city, as did its daughter libraries in the Caesareum and the Serapeum, and lecture halls discovered in the center of the city signal a continued intellectual presence in Alexandria through the Late Antique.322

In accordance with the classicizing intellectual and physical vista of the city, Alexandria's monumental tombs also assume a Graeco-Roman visage. Deeply cut into the nummulitic limestone, Ptolemaic-period tombs are multiroom buildings accessed by a staircase and often built around an open courtyard, so that they were easily visible from above. Though in its aggregate the Alexandrian-type tomb follows no earlier Greek model, it nevertheless incorporates conceptual inspiration from Macedonia;323 klinai, for example, – which trebled in Greece as a bed, bier,324 and banqueting couch – are cut to lay out the dead, permitting them to join in the funerary banquet. Walls of Alexandrian tombs are decorated in both the Greek zone style325 and the Greek masonry style,326 and architectural components – columns, capitals, and entablature friezes – all follow Greek architectural principles.

Roman-period Alexandrian tombs conform to the Ptolemaic model. They too are multiroom tombs, rock cut, and entered through a staircase. Roman-period tombs, however, often dispense with the kline and its niche and substitute instead a triclinium-shaped chamber (or chambers) with trabeated or arctuated niches formed by cutting Roman-type sarcophagi into the fabric of the room. Only in the Roman Imperial period and in Latin is a bed differentiated from a banqueting couch – lectus cubicularis, for the one, and lectus triclinaris for the other – 327 so the introduction of the triclinium-shaped chamber in Roman-period tombs does not merely indicate a contemporary emendation of the banqueting metaphor, but reflects a semantic change, ensuring that a banqueting couch is recognized as the intended allusion.

Despite this inherent classicism, an innate self-confidence in their Hellenic identity born from their privileged social position in Ptolemaic Egypt early permitted Alexandrians to admit Egyptian elements into their burial monuments. Almost from their inception in the late-fourth or early-third century bce, Alexandrian monumental tombs incorporate Egypt. Loculi, the long, narrow burial slots for inhumation and cremation burials that perforate the walls of even the earliest Alexandrian tombs, have their genesis in Egypt,328 and at least as early as the third century bce, figurative Egyptian elements invade the otherwise Classical fabric of the monumental tomb. During the period of Roman rule, Alexandrians adopted further Egyptian architectural elements, motifs, narratives, and signs to express their own Greek eschatological necessities.

Greeks early recognized the primacy Egypt held in mortuary religion, and its authority is encapsulated by Herodotus.329 In Book II of his Histories, Herodotus, who visited Egypt between 449 and 430 bce,330 frequently privileges the antiquity of Egyptians over that of Greeks, especially in the realm of religion. “[Egyptians] are beyond measure religious, more than any other nation,” Herodotus (II.37) writes. He adds (Hdt. II.4) that Egyptians were the first to use the term twelve gods,331 that many of the names of Greek gods come from Egypt (Hdt. II.50; 52; 54), including that of Herakles (Hdt. II.43),332 and that from Egypt came the oracle of Zeus at Dodona in Greece (Hdt. II.54). Herodotus (II.49) credits the origin of Dionysiac ritual to Egypt, as well as divination from the entrails of sacrificial animals (Hdt. II.58). It was the Egyptians, Herodotus (II.64) continues, who first forbade intercourse with women in temples, obviating the hieros gamos and the more generalized temple prostitution of their Eastern neighbors,333 a proscription encapsulated in the Greek myth of Tydeus and Ismene.

Herodotus (II.85–89) devotes four chapters to Egyptian mourning customs and embalming and says that Egyptians were the first to teach that the human soul is immortal (II.123).334 The general privileging of Egypt in all matters religious, regardless of the veracity of these claims, and the antiquity claimed by Herodotus for Egypt in these matters instructed the educated Greek population and strongly informs the incorporation of Egyptian elements into the decoration of the monumental tombs of Alexandrian Greeks. In Alexandria, the inclusion of Egyptian elements into an otherwise classicizing tomb acts as a further means of ensuring a blessed afterlife for the inhabitants of these tombs.

Ptolemaic-Period Tombs

The earliest Ptolemaic tomb that best exemplifies the underlying model for Alexandrian tombs, as well as their burgeoning bilingualism, is Hypogeum A in the cemetery at Chatby,335 which hugs the coast just beyond the putative line of the eastern wall of ancient Alexandria. Only slightly later than the tomb of Petosiris at Tuna el-Gebel, Hypogeum A is probably to be dated no later than 280 bce.336 It is the earliest fully realized monumental tomb extant in Alexandria, and it is directly ancestral to all later Alexandrian monumental tombs. Like later Alexandrian tombs, it held multiple burials, which stretched over a number of generations.

Hypogeum A

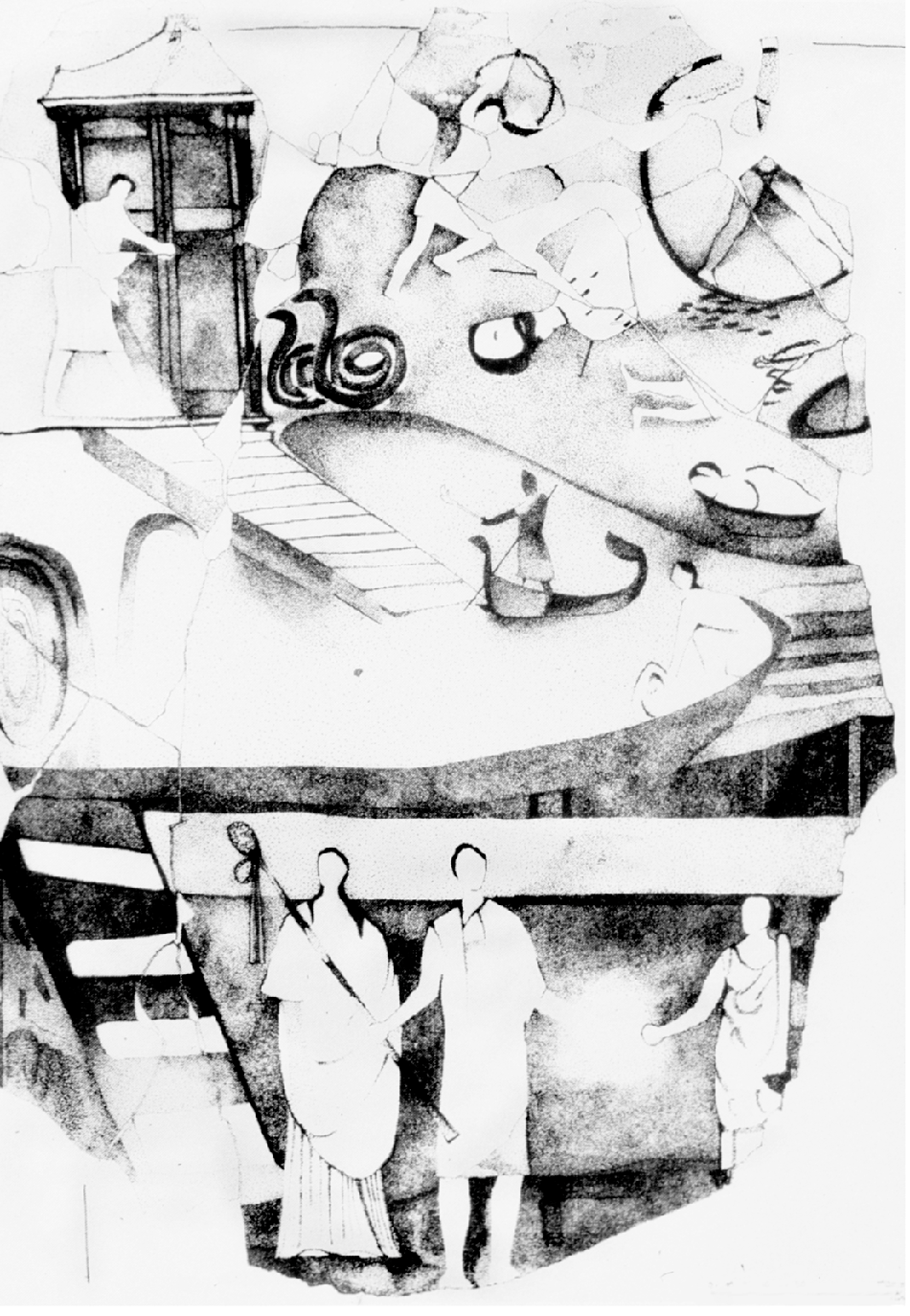

Hypogeum A assumes the form of a multichambered tomb accessible by a stairway (no longer extant) cut down through the living rock (Fig. 2.1). It is architecturally articulated and illusionistically painted to re-create a monumental building with a court open to the sky around which the burial chambers and subsidiary rooms are arranged, and its walls are embellished in both Greek masonry- and zone-style.337 Both types of wall decoration divide the surface into a low plinth, a high zone of orthostats, a narrow string course, a main zone of isodomic blocks, and a narrow upper frieze,338 and almost all the architectonically treated walls in Ptolemaic-period Alexandrian tombs conform to this general type, as – more surprisingly – do many Roman-period tombs in the chora (see Chapter Five).

Though the ultimate form of Hypogeum A finds no model in Greece, itself, the individual architectural elements of which it is composed are of pure Greek descent. The walls of the anteroom preceding the open court are treated in the plastic Greek masonry-style (Fig. 2.2). The plinth is incised vertically to indicate individual blocks, and, above it, yellow orthostats are capped with a blue string course, carved in low relief, and a white painted frieze. The walls of the anteroom and the court are both enlivened by engaged Doric half-columns, carved with their lower sections plain and their upper sections fluted – an early example of the horizontally divided, partially fluted column.339 Strikingly, and preserved in no other Alexandrian tomb, the interstices between the columns were painted light blue to simulate an airy vista, and to add further veracity to the trompe l'oeil effect, garlands were painted as strung between the columns of the court and birds were depicted fluttering against the blue sky.340 Even more strikingly, on the south wall of the anteroom, fictive windows with shutters painted yellow against the blue enliven the wall (See Fig. 2.2). The stone around the ‘window’ itself is cut obliquely, permitting the second ‘shutter’ to be placed at a diagonal angle to the stone's surface,341 and giving the impression that someone has just lazily pushed a shutter ajar, thus populating the uninhabited anteroom with a human agent similarly to the empty court having been brought alive by painted birds.

2.2. Alexandria, Hypogeum A, Reconstruction of the South Wall of the Anteroom

The long walls of the burial room are each punctuated by five engaged Ionic columns visually supporting an entablature capped with dentils near the springing of the low-vaulted ceiling. On the far, short wall of the room, an Ionic doorway leads into the kline chamber. The latter holds two kline-sarcophagi set at right angles to one another,342 an arrangement known from Macedonian tombs and others,343 but so far exceptional in Alexandria. Greek dining rooms (unlike Roman triclinia) admitted a varying number of couches, which were arranged around the periphery of the room – set head to foot abutting one another and fitted into the corners of the room – a model followed by the two kline-sarcophagi in Hypogeum A.344

Despite the Greek architectural envelope of Hypogeum A, however, and the Greek kline-sarcophagi, the tomb's primary burial room and its somewhat later subsidiary burial rooms are cut with loculi for the disposition of the greater number of the dead. In fact, unpretentious chamber tombs in early Alexandrian cemeteries also admit loculi cut into the walls. Though a pragmatic necessity for the disposition of multiple dead, loculi mark the earliest intrusion of an Egyptian element into the otherwise Classically based Alexandrian tomb. Of much greater relevance, however, to the thesis of the bilingual nature of Alexandrian tombs are the tombs that follow from Hypogeum A.

The Tombs at Moustapha Pasha

Also to the east of Alexandria, but more distant from the city than Hypogeum A, the tombs at Moustapha Pasha (in the quarter now renamed Moustapha Kamel345) provide a more complicated visual bilingualism than that encountered in the former tomb. Moustapha Pasha 1, better preserved upon its excavation than Hypogeum A, was early reconstructed. Though other tombs in Alexandria were certainly as opulent,346 Moustapha Pasha 1's wealth of original detail and careful restoration ensure that it serves as the poster-child for early Ptolemaic Alexandrian tombs.347 It is most likely that the tomb dates somewhat before the middle of the third century bce,348 and it exemplifies the maturation of the original model characterized by Hypogeum A.

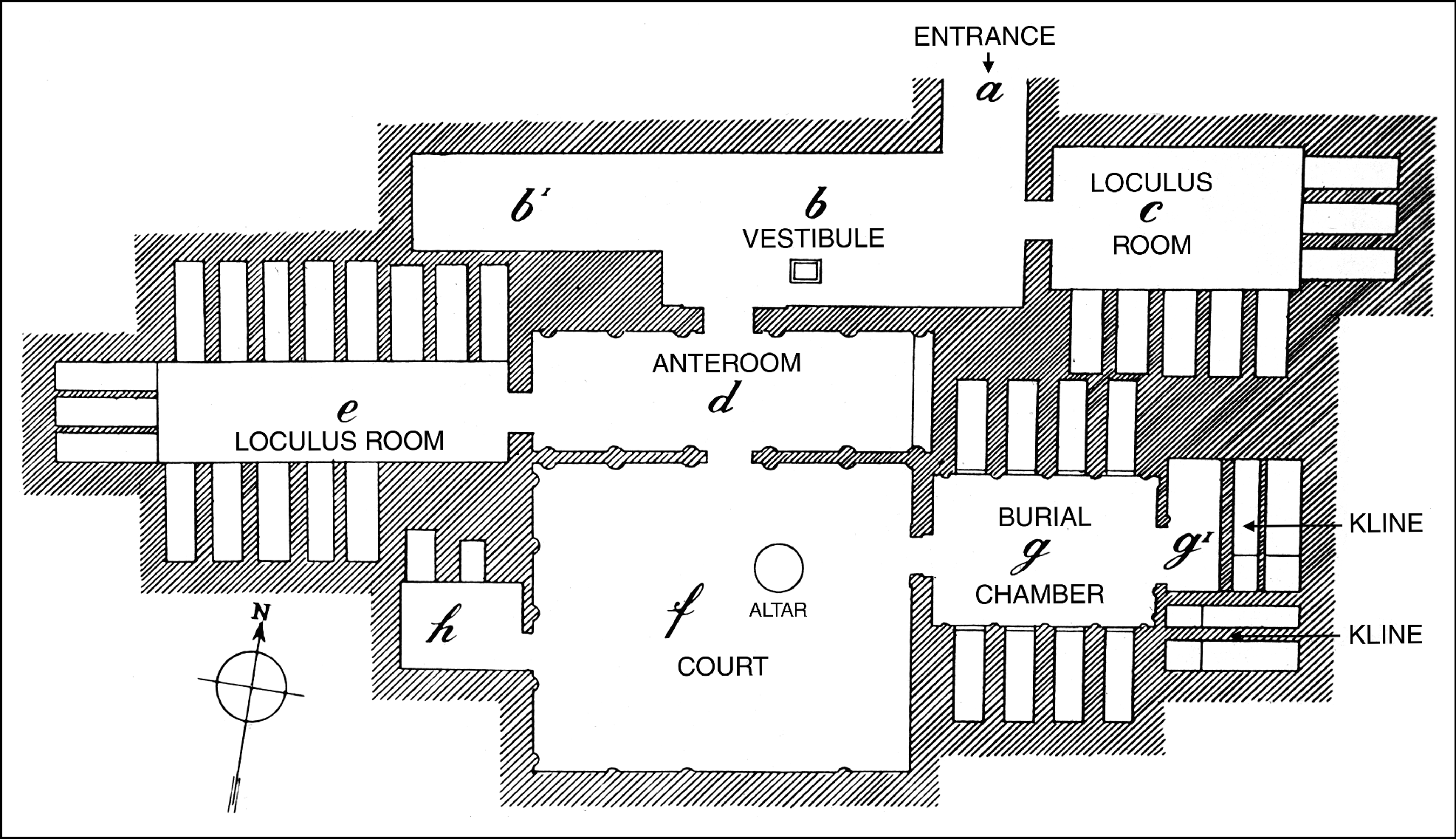

Like Hypogeum A, Moustapha Pasha 1 is a multiroom construction built around an open court (Fig. 2.3). A rock-cut stairway enters the court at the north end of the west wall, and rooms open from the court's south and north walls. Centering the court is an altar that still preserved the ashes of the last sacrifice when it was excavated.349 The burial room is to the south of the court, with its kline niche preceded by an anteroom accessible through any of the three doorways cut into the court's south wall. Although no remains of a kline are evident, the kline room's architecturally articulated doorway finds a parallel in the kline chamber in Moustapha Pasha Tomb 2, and its richly painted interior and the low platform set at its entrance as a base for the trapeza (a small table) that stood before the kline – which can be reconstructed by the trapeza extant in front of the kline in Moustapha Pasha 2350 – solidify the chamber's function.351 To further emphasize the metaphorical purpose of the rock-cut banquette, klinai in Moustapha Pasha 2 and Moustapha Pasha 3 add footstools carved in high relief.352 These domestic appointments remove the kline (and the kline-sarcophagus) from a primary function as a bier. They further confirm the evidence yielded by the arrangement of the kline-sarcophagi in Hypogeum A that situate the couches in the realm of the banquet of (or with) the dead.

As in all Alexandrian tombs, the architectural details of Moustapha Pasha 1 are Greek (Fig. 2.4 and Fig. 2.5). The doors in the court are each formed of two uprights crowned by a projecting short cornice decorated with superimposed bands of plastically rendered Lesbian-leaf, Ionic egg-and-dart, and Doric-tongue ornament. Though unusual in Alexandrian tombs – and possibly an artifact of the tomb's early date – as in Hypogeum A, the walls of the court are conceived in Greek masonry-style; as also in Hypogeum A, they are further punctuated by engaged, horizontally divided, partially fluted Doric columns. At each corner of the court, these columns become heart- or ivy-leaf-shaped in section, assuming a form probably of East Greek origin,353 to bridge the angle.

2.4. Alexandria, Moustapha Pasha 1, the South Wall and the Altar

2.5. Alexandria, Moustapha Pasha 1, the South Wall, Detail of the Sphinxes

Above the Doric columns is a Doric frieze with three metopes within each intercolumniation on the north and south sides of the court and two on the east and west. The three-metope wide intercolumniation on the walls of the court that open onto rooms conforms to the established practice in Greek stoas and theater buildings. This configuration is used to retain reasonable proportions for both the metopes and the architrave in a situation in which, on the one hand, the column diameter is relatively small because the columns are relatively short and, on the other, the intercolumniation has to be relatively wide to accommodate pedestrian traffic.354 Yet within this fully understood Greek architectural framework, Moustapha Pasha 1 incorporates the earliest example of figurative Egyptian content in an Alexandrian tomb.

This nascent bilingualism is telling both in its sophistication and in its form. In front of the south facade of the court of Moustapha 1, sphinxes crouch on pedestals guarding the entrances to the burial chamber (see Fig. 2.5). Yet though the sphinx is a very old Greek guardian of the tomb,355 the Moustapha Pasha sphinxes are not Greek sphinxes, which are normally winged and female and sit back on their haunches with their forelegs firmly planted, as does, for example, the sphinx that queries Oedipus in Chapter Three. Egyptian sphinxes are notably different: they perform a different function, assume a different gender, and strike a different pose. They are not tomb guardians but instead are connected with royal power, and they are normally male, unwinged, and crouch like lions. Yet though the sphinxes in the Moustapha Pasha tomb function as Greek sphinxes, in form, pose, and attribute they replicate those of Egypt. Crouched like Egyptian sphinxes and wingless like Egyptian sphinxes, their gender indeterminate, they wear the royal nemes headcloth of Egyptian pharaohs. Similar sphinxes once guarded the Hellenically styled doorway to the first suite of burial rooms of the Alexandrian tomb Anfushy II, on Pharos Island, and they were also set in front of the egyptianized doorway between its anteroom and burial room (Rooms 1 and 2).356 With sophisticated efficiency, these sphinxes incorporate the efficacy of Egyptian antiquity into their Greek visual synonym, and by means of this Egyptian reference, they create a new, more greatly nuanced, and doubly efficacious image of supernatural protection for this monumental tomb. Concurrently, with their nemes headdresses and their reference to Egyptian royalty, these sphinxes add a regal note to tombs in which no royalty were interred.

The Tombs of Pharos Island

The sphinxes that inhabit Anfushy Tomb II mark only one contribution to the bilingualism that informs the Alexandrian tombs of Pharos Island. Once connected to the mainland by the manmade Heptastadion and now a peninsula north of the mainland, Pharos Island is named after the lighthouse, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, that stood at its eastern tip.357 The monumental tombs of Pharos Island, those at Anfushy and those on the grounds of the former palace at Ras el Tin, occupy the western part of the peninsula with Anfushy as the farther west of the two complexes. First cut in the second century bce, these tombs actively demonstrate Alexandrian bilingualism and the conceptual and visual richness that results, though – aside from the sphinxes in Anfushy II – their strategies differ from those devised for Moustapha Pasha 1.

Accessed by a covered stair and built around an open court like Hypogeum A and the Moustapha Pasha tombs, the tombs at Anfushy and Ras el Tin follow similar, though reduced, plans to those encountered in earlier Alexandrian tombs. Extending from the open court are one or two suites of rooms, in each of which a long anteroom precedes a smaller burial chamber. Rock-cut klinai are rare in Pharos Island tombs,358 and it is probable that in most tombs wooden klinai served in their place.

Obviating any possibility of these tombs being those of Egyptians native to Pharos Island as argued by Achille Adriani,359 Anfushy tombs retain their Graeco-Roman underpinning well into the first century ce. Room 3 of Anfushy Tomb I,360 for example, the only tomb that is significantly reconfigured architecturally, is refashioned with three brick-built sarcophagi forming the metaphorical triclinium that Roman-period Alexandrian tombs adopt for their burial room as they architecturally transform the earlier Greek banqueting metaphor of the kline to a form paradigmatic of the Roman period. Anfushy I.3 preserves this change from the Greek to the Roman dining format in material form. This architectural change, as well as showing a continuity in classicizing style, also underscores the importance of the banqueting metaphor in the conception of the Alexandrian tomb, a theme that is further explored later.

In addition to the architectural transformation in Anfushy Tomb I, the original decoration of the other tombs at Anfushy also demonstrates their Classical heritage. Their walls are decorated in Greek zone-style, as seen earlier in Hypogeum A, with a socle, a course of orthostats treated – as is normal in Alexandria – as if made of alabaster, a string course, and a main frieze painted to simulate isodomic blocks. Ceilings of the rooms are most often painted to simulate coffered blocks, also a Classical reference. Yet despite their Hellenic heritage, Egyptian decorative elements are incorporated into the tombs at Anfushy, either applied later or integrated into the original Hellenic decorative scheme.

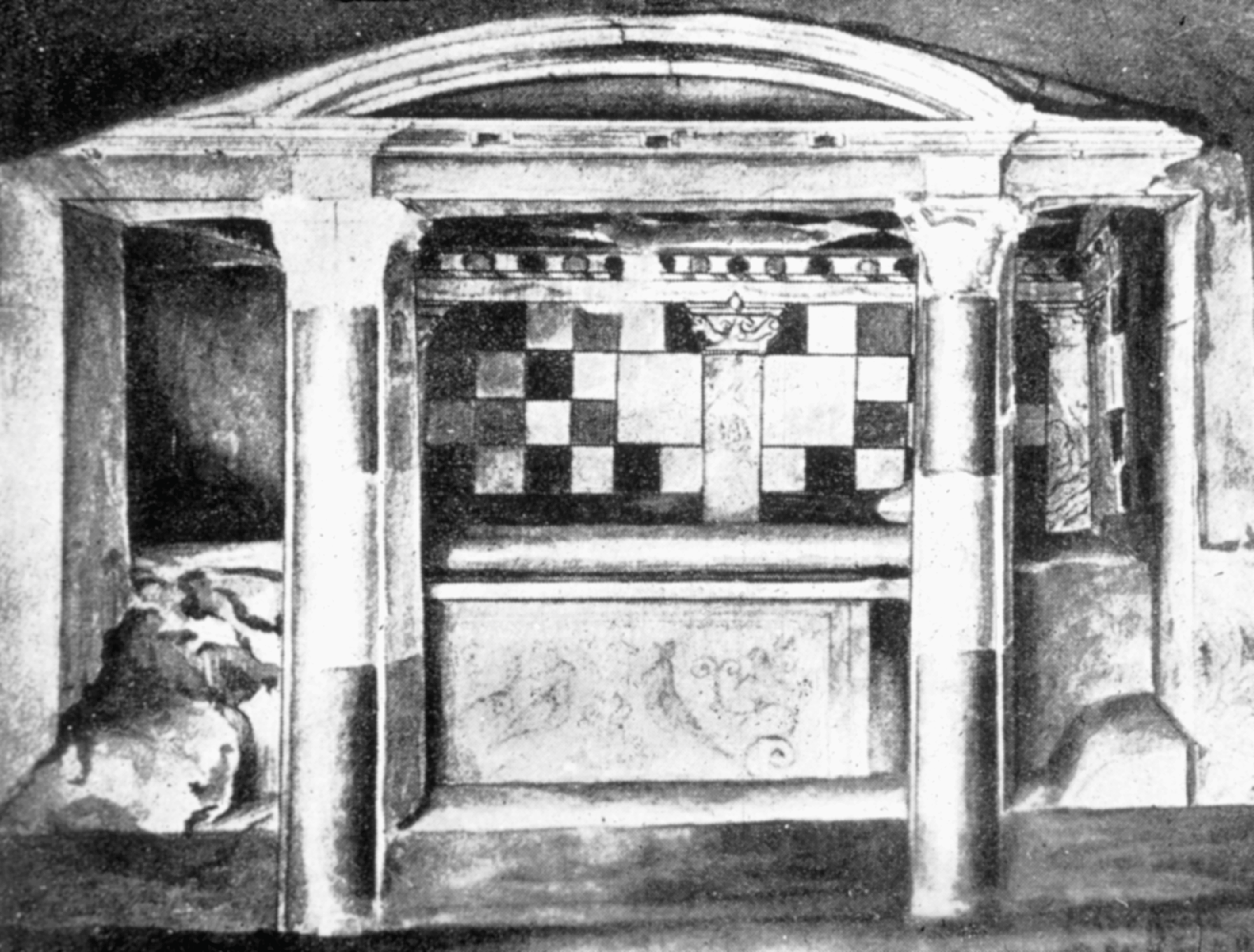

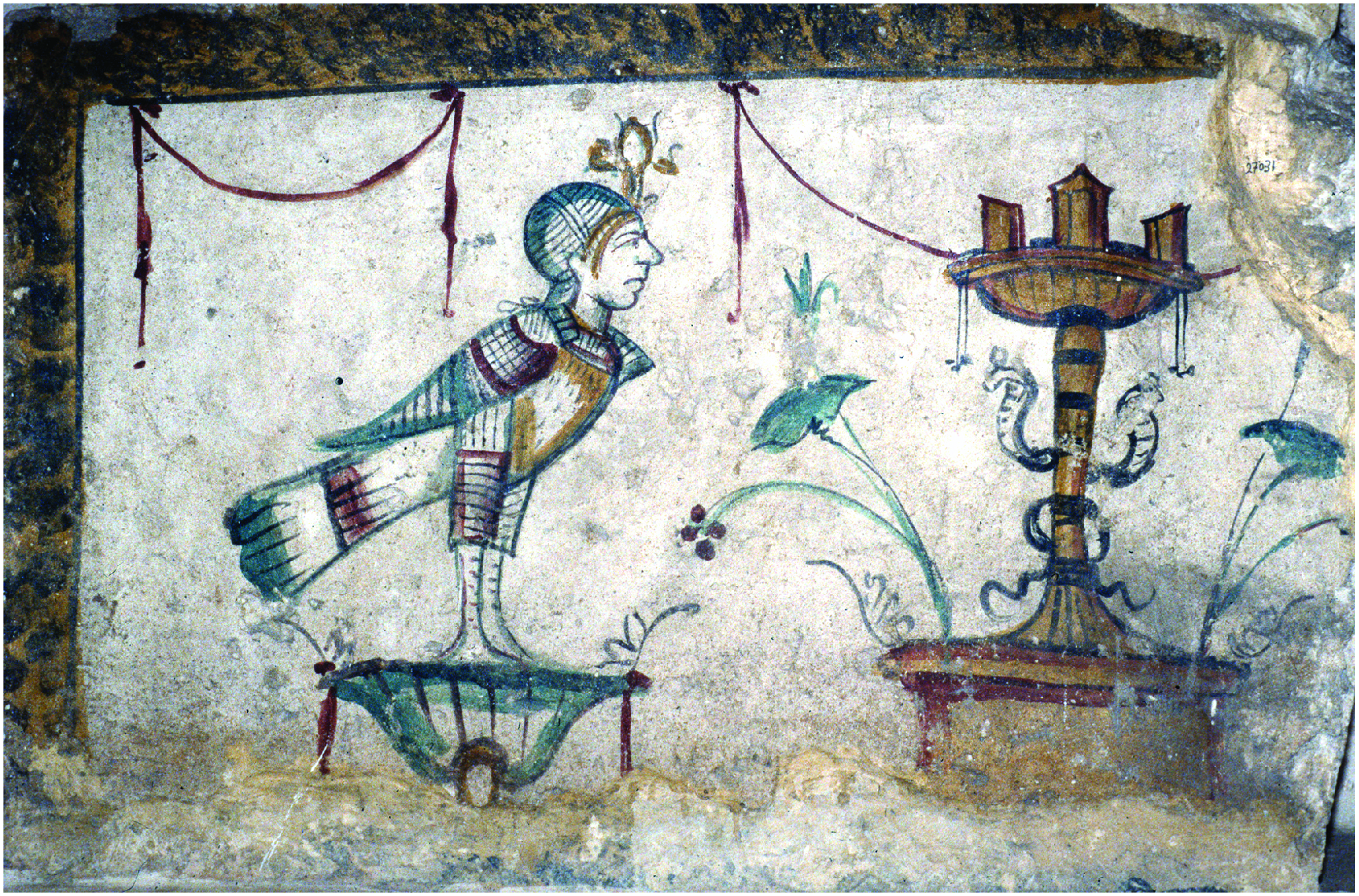

One of the anterooms (Room 1) of Anfushy Tomb II,361 for example, preserves this change in the renovation of the main frieze region of its zone-style wall (Pl. IV). In its original state, the main frieze had been painted to simulate ashlar masonry, as in other Alexandrian tombs; in a second phase, however, the main frieze was repainted with a checker pattern in black and white with Egyptian crowns painted on white ‘plaques’ set within the checkerboard of the wall. The string course and upper frieze of the original Greek zone-style wall were also refashioned with the checker pattern, but the orthostats were repainted to appear as the original alabaster and the coffered ceiling remained unchanged. The same checkered pattern is also applied to the tomb's burial room (Room 2), which was previously undecorated and in which the checker-pattern covers the entire wall.362 As in the antechamber, the checkers are interrupted by plaques painted with Egyptian crowns; in addition, on the entrance wall, a plaque to either side of the doorway bears a painted jackal, which faces the entrance and guards the burial room as jackals do on the seals of the necropolis in pharaonic Egypt,363 though the Anfushy jackals sit alertly upright like Greek sphinxes.364 The same checker decoration is found in the kline room of Ras el Tin 8 (Fig. 2.6), which also has two large plaques incorporated in the design, and in Anfushy V365 (Pl. V), though in both tombs, the checkered pattern coexists with contemporaneously painted Greek-style elements.

IV. Alexandria, Anfushy Tomb II, a Refashioned Wall in the Anteroom

V. Alexandria, Anfushy Tomb V, Room 4, Checkers and the Doric Embrasure

The checker motif, as first noted by Rudolf Pagenstecher,366 was intended to simulate faience tiles, a decorative wall treatment historically tied to Egypt.

Faience tiles appear in Egypt as early as Dynasty I,367 but they are most frequently attested in the New Kingdom where they are found in palace context.368 In these palaces, faience tiles can bear figurative subjects ranging from delicately rendered vegetative and faunal elements to descriptively faithful portrayals of foreign peoples; therefore, though, so far as I know, the specific subjects of the mimetic faience plaques on the walls of Anfushy Tomb II are unattested in extant New Kingdom material, in their ideation the figured faience plaques also find a pharaonic model, and that model is a royal one.

Actual glazed faience tiles are also found in Ptolemaic Alexandria. Sixty faience squares were excavated in Alexandria's Royal Quarter, and, although their specific architectural context is unclear, their findspot argues for their having embellished some part of the palace complex at about the same time that Anfushy Tomb II was redecorated.369 Their findspot consequently argues that the faience tile retained the Egyptian palatial connotation that it carried in the pharaonic period, and it constitutes the strongest argument against identifying this culturally Egyptian material in the Ptolemaic period solely with peoples that are ethnically Egyptian. In a tomb complex, such as the one at Anfushy, that normally shuns figurative content and relies on illusionistic architecture to make its statement, the faience tiles must stand (as they undoubtedly do in the Ptolemaic palace) as a referent for Egypt. Like the crouched royal sphinxes that guard the doorways to the burial rooms at Moustapha Pasha Tomb 1 and Anfushy II, the faience tiles in the tombs on Pharos Island articulate the intention to entomb the dead within a complex with regal implications.

At the same time as the refurbishing of the walls of Anfushy II, the doorway between the anteroom and the burial room was reconfigured from a Greek doorway to an egyptianizing one (Fig. 2.7). The redesigned door enclosure boasts Egyptian varicolored columns crowned with papyriform capitals supporting an Egyptian segmental pediment with a central disc and a broken lintel, which is applied to the door frame about halfway up. In contrast, Anfushy V, which also presents two types of simultaneously constructed ethnically specific doorways, admits this bilingual decoration contemporaneously. The entrance to one of the anterooms of Anfushy V (Room 4), for example, is effected through an architecturally egyptianizing doorway, whereas the embrasure between the anteroom and its burial chamber (Room 5) is hellenizing with white uprights crowned by a molding of brightly painted Lesbian leaf (see Pl. V).

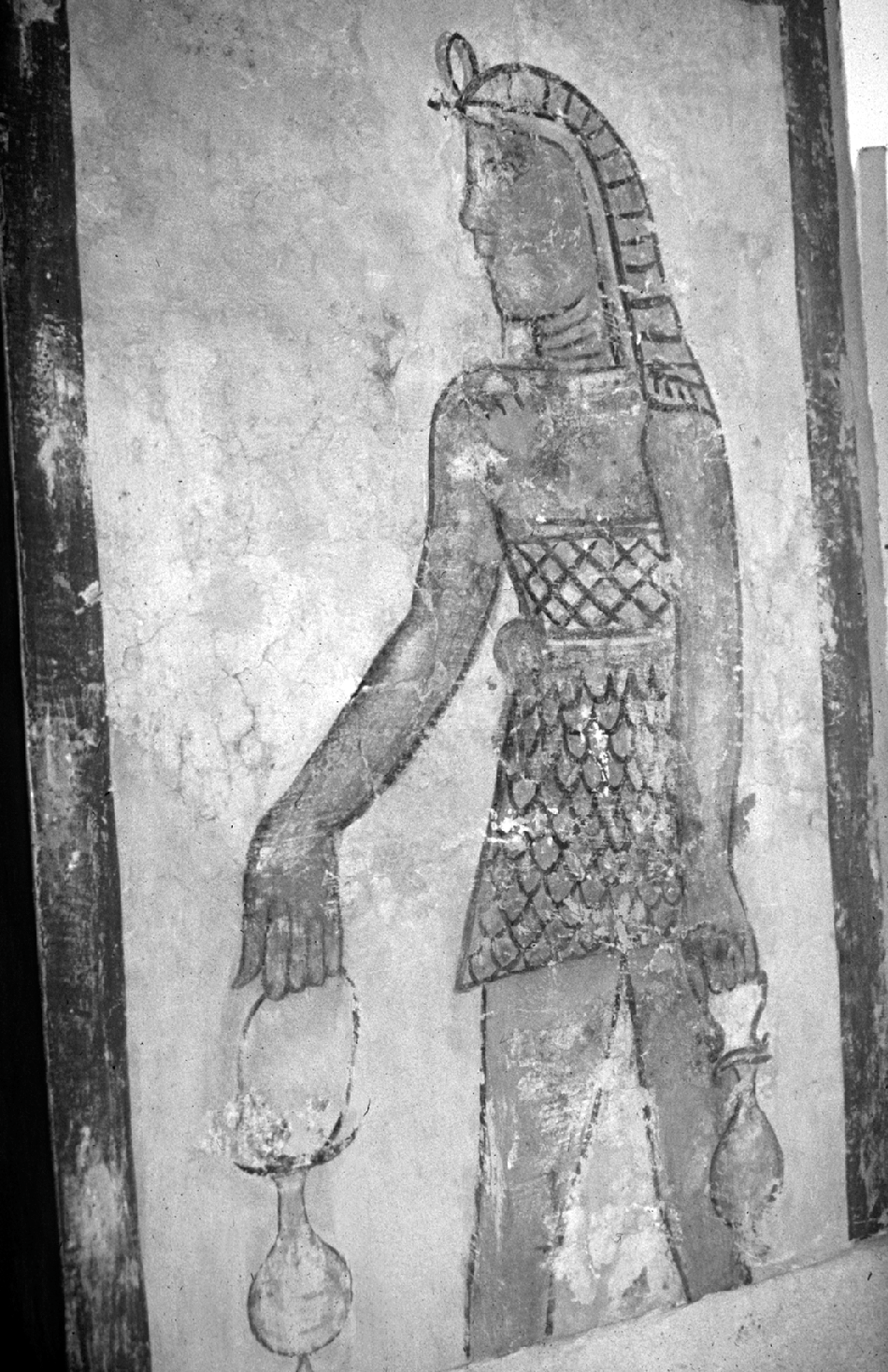

Probably at the same time in the first century bce that Anfushy II was redecorated, three egyptianizing paintings were added to the otherwise Greek-style walls of the staircase. Two are extant; one is set into the main frieze on the first landing at the bottom of the first flight of stairs, and the second is placed in the semicircular space created by the vaulted ceiling at the end of the second flight of stairs immediately before the doglegged entrance to the court.

Because the tombs on Pharos Island generally reject figurative imagery in favor of architectural iconography, the paintings of Anfushy Tomb II are notable. The painting at the bottom of the second stairway is the less well preserved of the two. At the right of the panel, a figure of Osiris is seated to the left on a throne with a jackal seated upright on a stand behind him. Any figures facing Osiris are no longer visible, but Adriani identified the figure immediately in front of Osiris as the dead man,370 and he saw another figure, which he identified as Horus.371 If Adriani's identifications of the missing figures are correct, this painting is an exceptional example in recorded Alexandrian tombs, since it would have presented an actual Egyptian eschatological narrative beyond that of the singularly frequently depicted lustration of the mummy.

The image on the first landing is better preserved and less exceptional within the Alexandrian corpus (Fig. 2.8). It shows the dead person welcomed by Egyptian deities. The figures are presented in a reasonably accurate, although generalized, Egyptian form and stand in the composite Egyptian pose. Their skin is painted the gold color reserved for the gods, but, aside from Horus at the left, whose falcon-headed form is immediately readable, they lack identifying attributes. Horus stands with his right hand upraised and his left poised on the back of the deceased. The deceased faces away from Horus toward the two figures at the left. He is garbed in an ankle-length garment, intricately arranged across his torso, and he wears an elaborate pectoral; his hair is styled in a conventional Egyptian manner.372 This mode of representation, in which deities lack attributes or in which attributes are awarded cavalierly without respect to tradition, is an aspect that more greatly invades Alexandrian mortuary representation during the period of Roman rule. In both the Ptolemaic and the Roman period, however, this pervasiveness of a generalized iconographic treatment indicates, at once, the efficacy of the egyptianized image itself, independent of the veracity of its precise form or the specificity of its narrative, and the disinclination of Alexandrian Greeks to depict traditional Egyptian narrative. As shall become clear, the lustration of the dead is the only certain exception to this generalization, with the image at the bottom of the staircase of Anfushy Tomb II providing a possible anomaly.

The tombs on Pharos Island, which may begin as tombs based fully on Hellenic components, evolve into ones that are architecturally (and in the case of Anfushy II, pictorially) bilingual. The elements that are chosen from the Egyptian architectural vocabulary to construct this bilingualism indicate that this linguistic choice is employed to speak to the fabricated regal status of the deceased entombed within the monuments, as well as to the efficacy of Egyptian mortuary religion.

The Sāqiya Tomb

Even the most classicizing of the later Ptolemaic-period tombs, the Sāqiya Tomb373 from the modern quarter of Wardian – part of ancient Alexandria's western necropolis – also admits Egyptian elements. When discovered, only the court, a kline room, and the remains of another room that abutted the court were at all preserved.374 The surviving painted slabs, which form a unique ensemble, were subsequently hewn from the bedrock and installed in the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria.

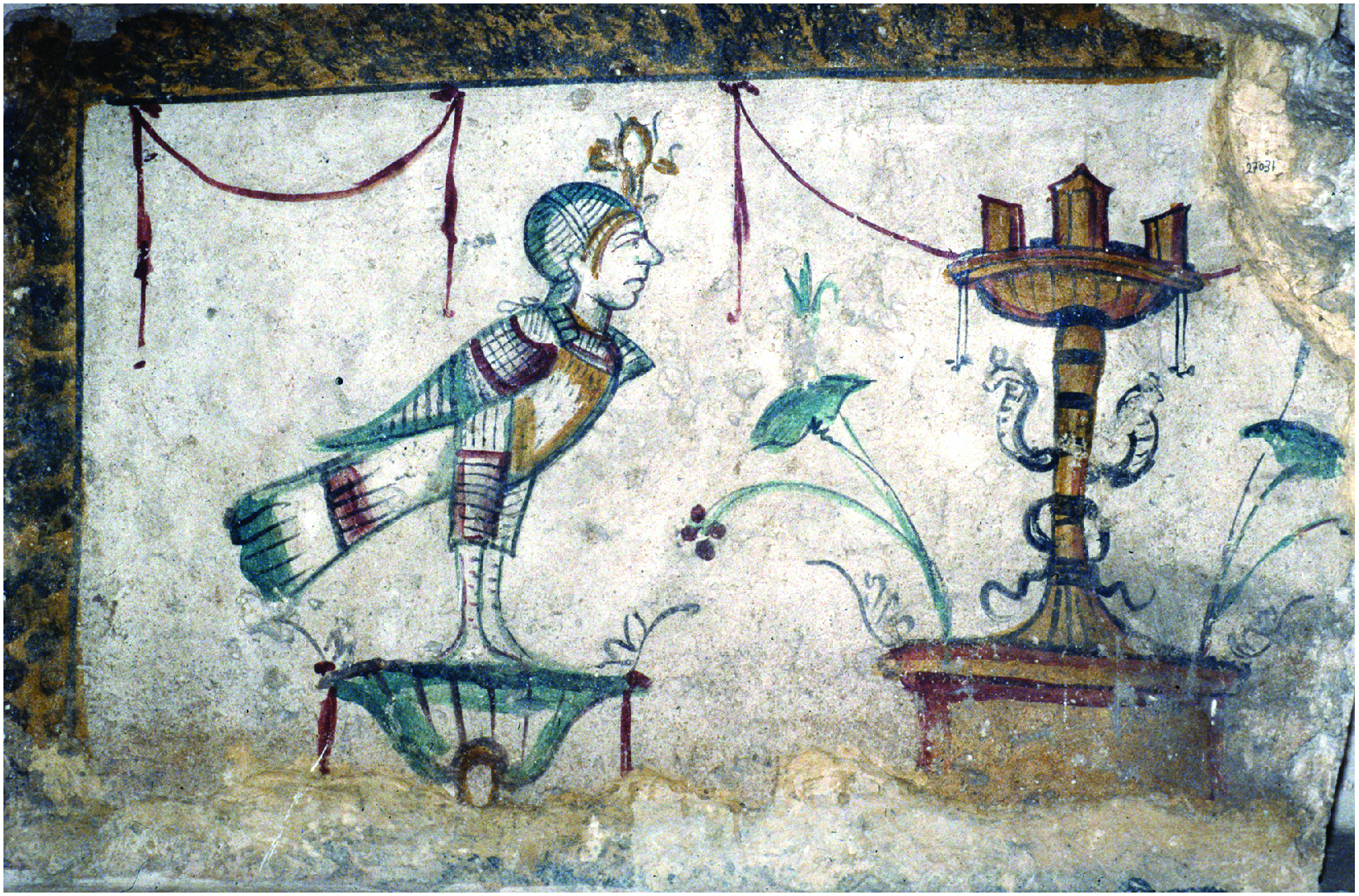

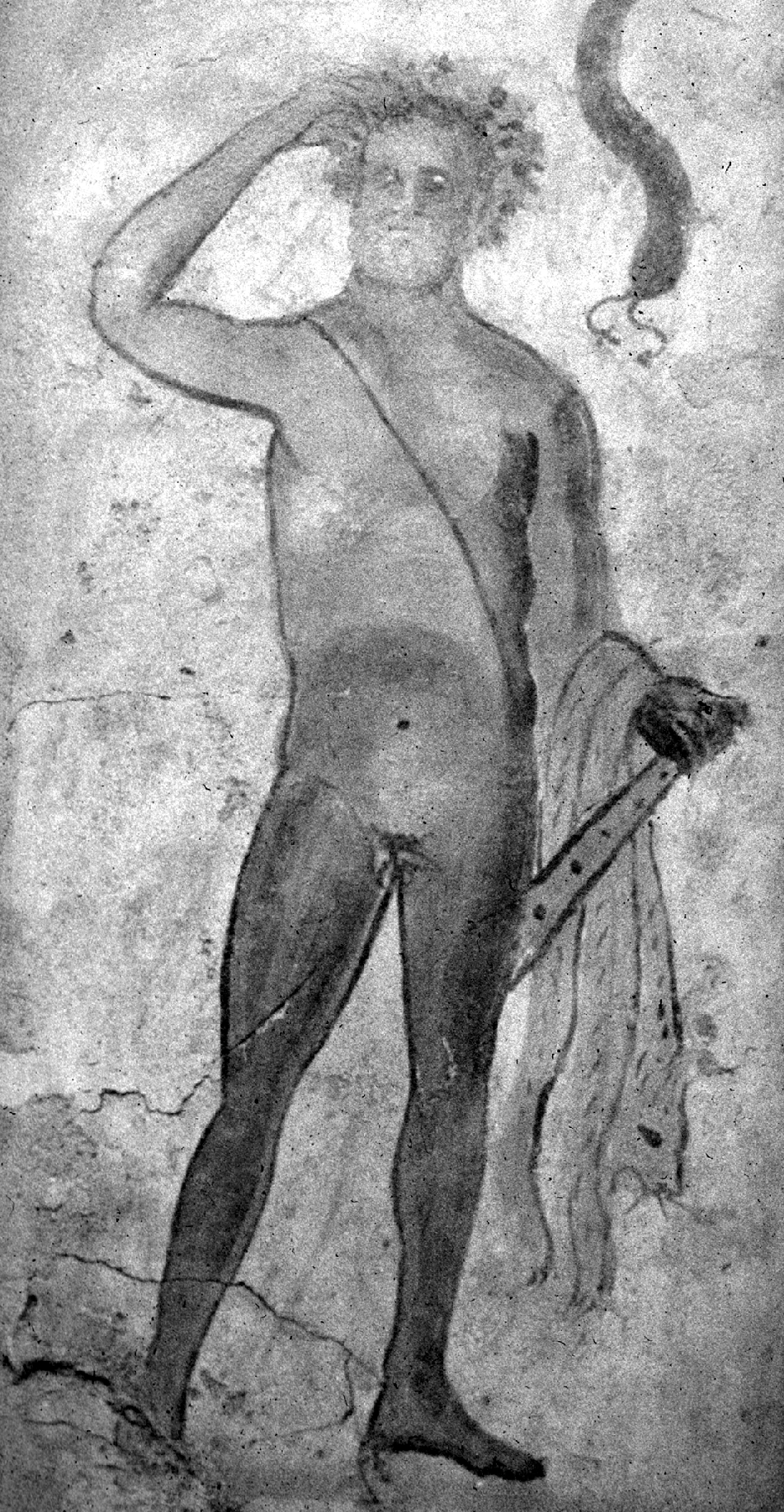

The tomb takes its name from the water-lifting device in the largest remaining painting in the court that shows a piping boy walking around a sāqiya, accompanying the oxen that turn the wheel (Pl. VI). Painted on the short wall perpendicular to the sāqiya scene is a bearded herm of Pan set in a woodland enclosure (Fig. 2.9). On the wall perpendicular to that one, and on what must have been the jamb leading into a second room, a shepherd overlooks his flock (Fig. 2.10), painted below, and protects it from the lurking jackal at the bottom of the picture. He holds an animal across his shoulders and stands in an easy chiastic pose. The scene finds a close visual parallel in an image of Herakles from Tomb 3 at Ras el Tin (Fig. 2.11), which also decorated a door jamb and which also is divided horizontally into two halves. Below the Ras el Tin Herakles (though not extant on the slab transported to the museum), a hoopoe perches on a plant,375 while above, the hero dominates the jamb – as does the shepherd – although Herakles stands in a much less convincing pose. The images in the Sāqiya Tomb are constructed using varying thicknesses of wash, and the details are quickly sketched with pen-like calligraphic lines. Their disposition follows that of contemporaneous (and earlier) Greek works: the oxen in the sāqiya scene are rendered in three-quarter view, and the shepherd stands in an easy weight-leg, free-leg stance. The style of all the scenes in the Sāqiya Tomb is undeniably Greek, and its content – with the exception of the waterwheel itself, which is a Hellenistic invention – is found in the Greek visual repertoire as early as the sixth century bce.

VI. Alexandria, the Sāqiya Tomb, the Sāqiya

2.9. Alexandria, the Sāqiya Tomb, the Herm in the Court

2.10. Alexandria, the Sāqiya Tomb, the Shepherd on the Jamb from the Court into an Adjoining Room

2.11. Alexandria, Ras el Tin 3, Herakles Soter

In concert with the Classical style of the figures on the walls of the court, the burial chamber incorporates facing klinai each set into an arcosolium.376 Arcosolia (arcuated niches) characterize Roman-period and, later, Christian tombs throughout the Mediterranean world, and the Sāqiya Tomb's arcosolia are among the earliest. Painted on the back wall of the niche formed by the klinai are birds (reminiscent of the avian treatment in the court of Hypogeum A), and fictive columns create the impression of a third dimension, as in Ras el Tin 8 (see Fig. 2.6). On the back wall of the kline chamber itself, a male reclines under a fruited arbor (Fig. 2.12).

2.12. Alexandria, the Sāqiya Tomb, Reclining Male on the Back Wall of the Kline Room

Nevertheless, within this exceptionally Classical tomb, two elements conjoin to add the Sāqiya Tomb to the inventory of Alexandrian bilingual monuments. First is the painting on the facade of a kline-sarcophagus cut into the court directly across from the sāqiya scene (Pl. VII). Conceptually similar to the cross-bred sphinxes in Moustapha Pasha 1, it presents another ancient creature, at once recognizable as an Egyptian ba-bird by the papyrus on which it perches and the nemes headcloth and the uraeus that it wears (neither of which, however, truly follows an Egyptian model) and as a Greek siren, which since at least the early fifth century bce has also had funerary connotations.377

VII. Alexandria, the Sāqiya Tomb, the Facade of the Sarcophagus

The Egyptian ba and the Greek siren are visually similar, but eschatologically distant. The siren, figured on vases – where it stands on the grave mound – and on grave stelai,378 is a protector of the tomb. The ba-bird is not. One of the constituent parts of a human being, the ba is an active element and therefore articulated in hieroglyphs as a heron and figured in imagery as a human-headed bird.379 The ba, usually translated as the soul, becomes especially important upon the death of the body. It is similar to the Greek ‘free soul’ (psyche) that leaves the body at death,380 but the ba, which also leaves the body of the deceased to roam about the celestial and underworld regions, must – unlike the Greek psyche – nightly reunite with the body to preserve the unity of the deceased. The ba is not a guardian of the deceased body, as the siren is, but provides the body with “life-giving connectivity.”381 The form and the funerary connotations of the Greek siren may well originally have been imported from Egypt,382 but the Sāqiya Tomb's soul-bird has acquired an occupational aspect from its Greek residence, since on the sarcophagus – where another ba-bird must have decorated the lost right side383 – it serves as a guardian for the deceased interred within. The oversized ba-bird with its fierce frown on the facade of Sāqiya Tomb sarcophagus assumes the form of an Egyptian soul-bird, but it functions protectively as a Greek siren.

Despite the Egyptian form and the egyptianized style the image adopts, however, details such as the thin washes of color and the fine, black, pen-like calligraphic lines that characterize the other paintings from the court reveal that the ba-bird (or siren) is by the same hand that painted the other images in the tomb and thus coeval with the remainder of the painted program. The integration of the Greek siren with the Egyptian soul-bird in the Sāqiya Tomb accords with the treatment of the sphinxes in Moustapha Pasha Tomb 1 and Anfushy II and argues for a dual reference inhabiting the heretofore culturally specific eschatological signs. In addition, the presence of this creature in this otherwise overwhelmingly classicizing tomb underscores the importance of the inclusion of the egyptianizing content throughout the tombs of Alexandria.

The second egyptianizing element in the Sāqiya Tomb is found in the remains of a room adjacent to the court384: its wall is designed in Greek zone-style with a plinth, orthostat blocks painted to appear as alabaster, and a main frieze, but the latter is decorated with a black-and-white checker pattern similar to that of the repainted walls in Anfushy Tomb II, and the original walls in Anfushy V and Ras el Tin 8. This simulation of faience tiles associates the Sāqiya Tomb from Wardian in Alexandria's western cemetery with tombs on Pharos Island,385 reemphasizing the Greek patronage of the former tombs. More important for the theme of this chapter, however, the checker decoration of the zone-style wall, as in the tombs on Pharos Island, incorporates Egypt, indicating an intentional bilingualism in a tomb in which the great majority of the imagery is in a style that evokes the Hellenic world.

The Sāqiya Tomb is bilingual in yet another way, since the landscapes also can be read to embrace both Greek and Egyptian eschatological viewpoints. They act, as do the poems in the tomb of Isidora (discussed in Chapter Three), to embrace both cultures by employing references culturally specific to each. I have previously argued386 that the Sāqiya Tomb's landscapes perfectly parallel those evoked in the shepherd's song in the First Idyll of Theocritus – the poet-in-residence in the Ptolemaic court in the 270s – as articulated by Charles Segal,387 and I have also argued that these landscapes in the Sāqiya Tomb (as those in Theocritus’ poem) can be interpreted metaphorically to address the range of human experience. The first two landscapes – those of the sāqiya and the herm – express the polarities of the human psyche. Civilization, and the triumph of culture, is epitomized in the land that is brought under human control by the invention of the sāqiya, while the untamed aspect of the human condition is delineated in the woodland sanctuary of the rustic, semi-goatlike Pan. Between these two extremes stands the third image: the shepherd guarding his flock. The pastoral land he exemplifies mediates between the cultivated and the undomesticated, for it is at once beneficial to humankind, since it supports his flocks, and yet it lies unaltered by human intervention. Thus, the three paintings of the court embrace the complexity of nature in its relationship to humankind. And, in doing so, they also speak to Egypt. S. C. Humphreys388 has proposed that the thrice-yearly harvest in the Egyptian Isles of the Blest indicates not only perpetual abundance but also an unchanging state that echoes the timelessness of the existence of the dead. The paintings in the Sāqiya Tomb may be intended to evoke a similar metaphor, as they too denote a fully rounded vision of the completeness and the permanence of nature and, by extension, the immutable eternal life of the deceased buried within the monument. Thus, though in ways distinct from one another, the Sāqiya Tomb and the tombs from Pharos Island, continue, amplify, and further nuance the bilingual quality of Ptolemaic-period Alexandrian tombs.

Roman-Period Tombs

Whereas rumblings of bilingualism can be heard as early as the first extant monumental Alexandrian tombs, the practice fully erupts during the period of Roman rule. In the first two centuries of the Common Era, almost all Alexandrian tombs that are architecturally particularized or figurally enhanced show an intersection of carefully chosen Greek and Egyptian elements. I have devoted a chapter to this phenomenon in Monumental Tombs of Ancient Alexandria,389 as well as an article,390 but I should like to revisit this curiosity to summarize previous thoughts and to offer new ideas on a subject that acts as a foundation for the appreciation of Roman-period Alexandrian tombs.

The Bilingual Tombs in the ‘Nebengrab’

The hill called Kom el-Shoqafa (the ‘Hill of Sherds’) shelters both Christian and Roman-period tombs beneath its current domestic and commercial crust, and it is two of the latter that are of immediate interest here – the so-called Nebengrab and the Great Catacomb.

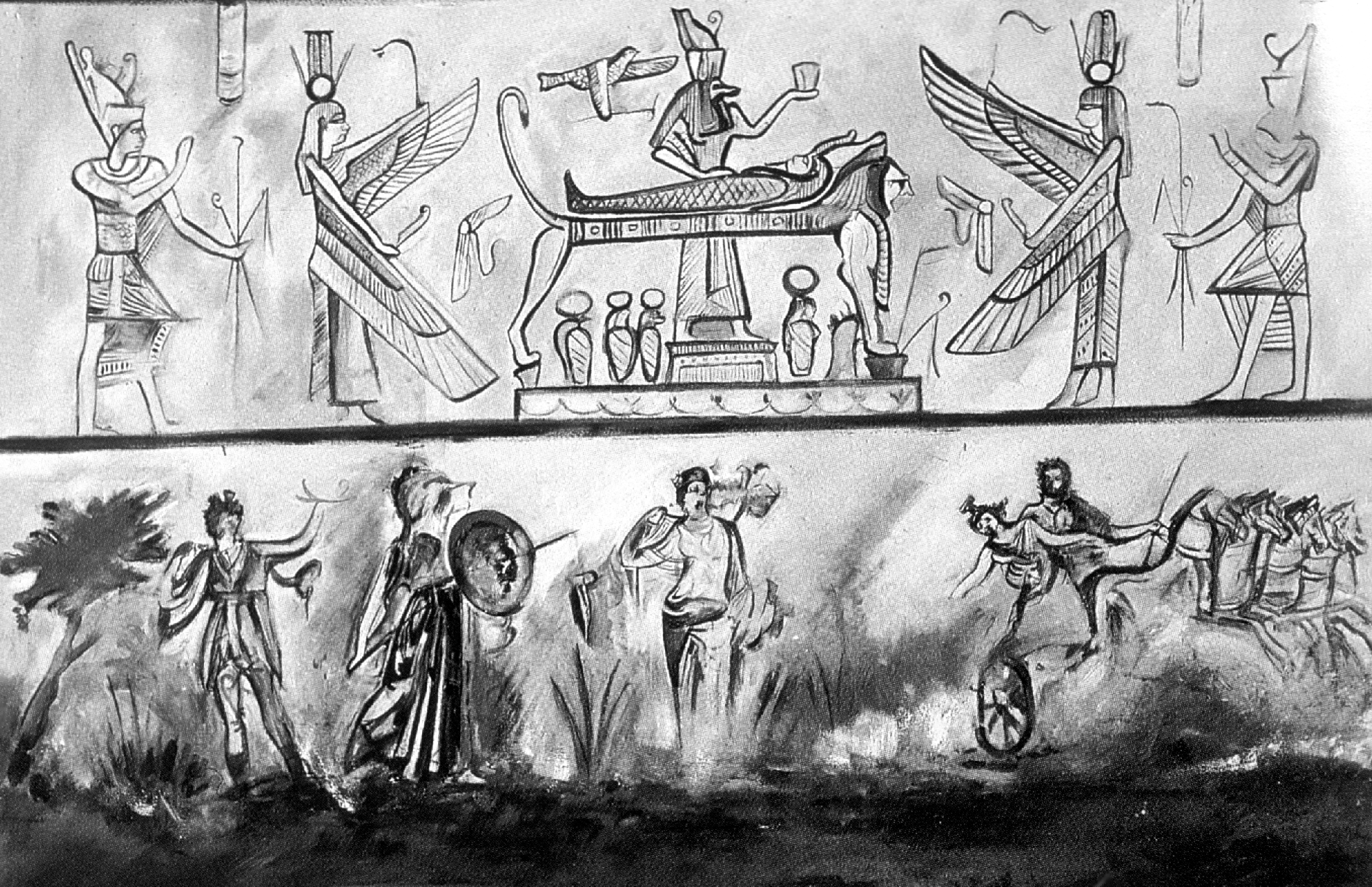

The ‘Nebengrab’ (so-called for its proximity to the better known ‘Great Catacomb’ at Kom el-Shoqafa) or, alternatively, the ‘Hall of Caracalla’ (called so, based on dubious historical interpretation),391 is now accessible from the Great Catacomb through a tomb-robbers’ hole in the bedrock. Originally a small independent catacomb accessible by a staircase, it consists of a corridor with a large room of neatly cut loculi at its end and two short corridors parallel to one another containing rock-cut sarcophagi that create niches – an early form of arcosolia, but with flat ceilings – that extend the conceit of the kline niche into the Roman period. The niches, with their triangularly shaped pediments supported by engaged piers, are conceived in Graeco-Roman architectural style. The paintings that once decorated the niches, pediments, and piers of the tombs are scarcely visible (or entirely lost) today, but upon the catacomb's discovery in 1901, Giuseppe Botti was able to identify the faint image of the lustration of the mummy on Tomb ‘i,’392 and a watercolor in Theodor Schreiber's monumental work preserves the decoration of Tomb ‘h,’ which shows confronted Graeco-Roman Nemesis sphinxes overseeing the tomb from their perch in the pediment and iconic Egyptian figures (including a ba-bird) on the piers and walls of the niche.393 Almost 100 years later, ultraviolet photographs taken under the auspices of the Centre d’Études Alexandrines clarified paintings on two other tombs in the adjacent corridor that humidity had dimly raised since the middle of the last century,394 which were published by Anne-Marie Guimer-Sorbets and Mervat Seif el-Din.395

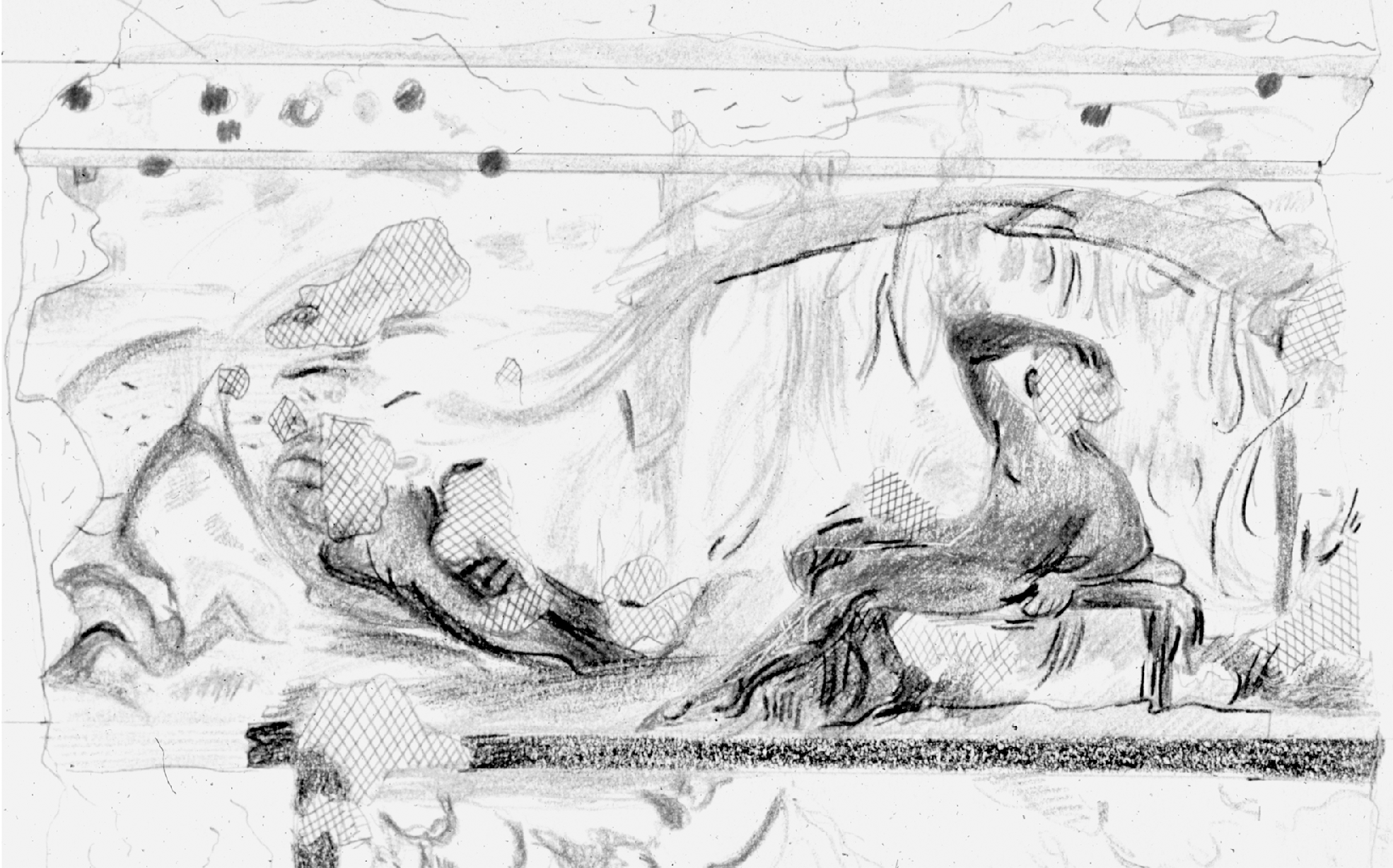

The walls of the niches of these two tombs are each divided into two registers: the upper register is devoted to the myth of Osiris, the lower to that of Persephone (Fig. 2.13).396 The upper frieze of the tombs’ back walls shows the lustration of the mummy (read by the authors as the death of Osiris, though it may as likely refer to the death of the inhabitant of the sarcophagus assimilated to the deity). Below is a scene of the abduction of Persephone, a scene frequent in Roman-period tombs throughout the Empire, regardless of the gender of the deceased.397 The left wall of Tomb 2, and almost certainly the right wall of Tomb 1 (the lower part is destroyed by the robbers’ cut), present two more scenes – the upper interpreted by the authors as the resurrection of Osiris and, below, the anodos of Persephone partly risen from the earth, having finally been discharged from Hades for six months of the year. The latter is a scene rarely visualized in Greek or Roman art and almost unknown in sepulchral context elsewhere.398

The authors of the publications of the two Nebengrab tombs coined the term ‘bilingualism’ to describe the visual polarity of the tombs’ imagery, concomitant with the inherent code-switching of the ensemble:399 the death and resurrection of Osiris coupled with the abduction to the Underworld and subsequent return of Persephone present congruent narratives. Neither is a literal translation of the other; each makes its point within its native visual language and its native mortuary ideal. But the inherent meaning of each – so far as the deceased is concerned – is the essentially same: each denotes the continuation of life after death.

Aside from the sophistication of the interlingual visual text that inhabits each of the two tombs, and even aside from the rarity of the anodos image of the ‘resurrected’ Persephone in mortuary context (occasioned here doubtless by the ‘resurrection’ image of Osiris and the necessity of parallelism), the scene of the abduction of Persephone carries another indication of the sophistication, as well as the iconoclasm, of these Alexandrian monuments. And this is an aspect that the authors do not address. This facet is of major consequence, however, since it demonstrates the erudition, originality, and resourcefulness of the Alexandrian constituency in their approach to visual imagery, and it thus provides a firm basis from which to argue the intentionality of the examples of interaction proposed throughout this chapter.

In both Nebengrab tombs, five characters populate the scene of the abduction of Persephone: Artemis (Diana), Athena (Minerva), Aphrodite (Venus), Hades (Pluto), and Persephone (Proserpina) herself.

The iconographic trope of Hades seizing an unwilling Persephone and carrying her off in his chariot, her arms flailing, is a late addition to the visual description of the scene.400 Early fifth-century Attic vases normally show a pursuit on foot in the gods-pursuing-women motif, and, later, fourth-century Italic vases most often show Persephone as a compliant accessory to her abduction.401 The work closest to the model that is seen here, and throughout the Roman period, is embodied in the painting in the Persephone tomb at Vergina that Manolis Andronikos argues was painted by Nikomachos preceding his portable painting of the same subject.402 The central image preserved in the Vergina tomb is duplicated on funerary monuments throughout the Roman world and also appears on Alexandrian coins of Trajan, Hadrian, and Antoninus Pius.403 Well before the 1977 discovery of the Vergina tomb, scholars had long considered that a painting by Nikomachos, known from Pliny (NH 35.36.108), was the source for Roman representations of the subject. Carried off to Rome where it was displayed in the Temple of Minerva on the Capitoline, the painting probably perished in the fire of 64 ce during the reign of Nero.404 Since representations in Rome – especially a polychrome mosaic from a columbarium on the Via Portuensis,405 which preserves the nymph Kyane and her basket of flowers – so closely adhere to the Vergina painting,406 it is likely that the painting in Rome was a reliable analogue of the extant painting from Vergina, whose discovery, in turn, now provides concrete evidence for the model. Though the extant replicas of the painting seen by Pliny excavated in Rome usually read – as does the Vergina painting – from right to left,407 those from the eastern Roman Empire tend even more often to read – as do the two in Alexandria – from left to right. The change in direction may not be noteworthy, since – boustrophedon aside – writing was directed left to right, and this orientation may have seemed much more natural.408 Nevertheless, the directional change encountered outside Rome may hint at the motif's means of transmission – that is, transference through the dissemination of cast objects. If the mold-maker failed to reverse the image, the ensuing object would carry the scene in reverse, as do the Alexandrian coins; the roughness of the Alexandrian paintings (and others in the Roman East; see Chapter Three) may in part stem from their reliance on a small-sized model. Nevertheless, the change in direction of the scene aside, the Alexandrian paintings do not faithfully follow the more usual model in another, more telling, detail.

The image in the Vergina tomb incorporates Hermes leading the chariot and one of Persephone's playmates, Kyane, still crouching near the flowers she had been picking. Other images of the story substitute Athena, or Athena and Artemis, for Persephone's mortal companion or companions, based on the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter” (line 424), probably composed in the early sixth century bce, that numbers the two virgin deities among the maidens playing and gathering flowers in the meadow. The two deities are specifically picked out by Euripides (Helen 1314–1318) and, later, Diodorus Siculus (V.4), which undoubtedly augments their visual frequency thereafter.409 The images in the two Alexandrian tombs, however, add the libertine Aphrodite to the two virgin deities elsewhere depicted. In this way, these tombs are almost unique in seemingly deriving their visual and textual source from one untapped by the other depictions of the subject.

This combination of the three deities appears in only one other object known to me, a stone relief on Corfu that Ruth Lindner thinks may have once formed part of a statue base and that she is comfortable dating only to the “Imperial period” followed by a question mark.410 The difference in the group is slight: the figure of Aphrodite is reversed, but it achieves the same pose as the one in the Nebengrab with the goddess lifting her veil signifying the impending union.

It is Aphrodite, Ovid (Met. 5.362–384) relates, who – galled by the virginity of Artemis and Athena and that of the virgin Kore, too – spurs on Eros to enrapture Hades. Aphrodite is occasionally pictured among the deities that witness the abduction of Persephone, but Lindner, who could not have known the Alexandria images, correctly notes in regard to the Corfu base that “the three-figure group of the playmates of Persephone, in this form, is unique.”411 She also observes that “the figure of Aphrodite, who steps majestically between the abduction and the pursuing sisters, is especially emphasized,”412 as she is in the Nebengrab's Persephone tombs, where she is set slightly apart from Artemis and Athena and centered in the frieze. The image on the Corfu stone also differs from the Alexandrian paintings in adding the figure of Hermes leading Hades’ chariot, as in the Vergina tomb painting and others, and it also includes a stylized image of an oversized lotus below the chariot. The flower – which is alien to the physical setting of the narrative – and its formal treatment – which is incompatible with the naturalistic treatment of the scene – might suggest Alexandria as the source for the iconoclastic threesome. Nevertheless, despite these slight differences, the Corfu relief seemingly employs the same visual source as the two Alexandrian images that, though painted by different hands, stem from a single model, as Guimier-Sorbets has seen.413

Despite the incongruous lotus blossom, the original visual source for the image cannot be definitively traced. The literary source seems clearer, though its authorship and date are complicated. “While Proserpina was picking flowers [on Mount Aetna] with Venus, Diana, and Minerva,” Hyginus records (Fabulae 146.2), “Pluto came on a chariot and abducted her.”414 The Hyginus often attributed as the author (or compiler) of the Fables is Gaius Julius Hyginus, a freedman of Augustus – according to Suetonius (On Grammarians 20) – who was either a Spaniard or an Alexandrian and who became the librarian at the Palatine Library. But as noted by Jean-Yves Boriaud,415 “the problems of authorship had already been raised in the first modern edition of the text by Jacobus Mycillus in 1535, where he set them forth in terms that have scarcely been outdated.” Boriaud, who recently edited and translated the Latin text,416 opts for Suetonius’ Hyginus as the Fables’ author or, more correctly, its compiler,417 though others have argued on etymological and stylistic grounds for an early-third-century ce date for the work.418 Since the Fabulae appear to be a compilation of earlier sources, however, the specific time of its compilation is incidental to any argument about the primacy of any specific myth.

The two Persephone tombs from Alexandria are loosely dated by the authors of their publication to the end-of-the-first through the middle-of-the-second century ce.419 They, and the undated relief from Corfu they bring with them, indicate that the myth that included Aphrodite among Persephone's immortal playmates was probably known in some form before the mid-second century (obviating the early-third-century date some propose for the origin of the variation of the myth), and it would not be entirely irresponsible to speculate that the author of the Fables was an Alexandrian who compiled his work under Augustus. The central position that Aphrodite assumes in the images – despite Ovid's version in which she embodies the fulcrum on which the narrative turns – may be tied to the originality of her role in the Fables, as understood and exploited by the creator of the model of the extant images. The use of this arcane version of the myth accords well with the rarified intellectual air that Alexandrians breathed daily and encapsulates the acuity that transfuses tomb programs in the Graeco-Roman capital of Egypt.

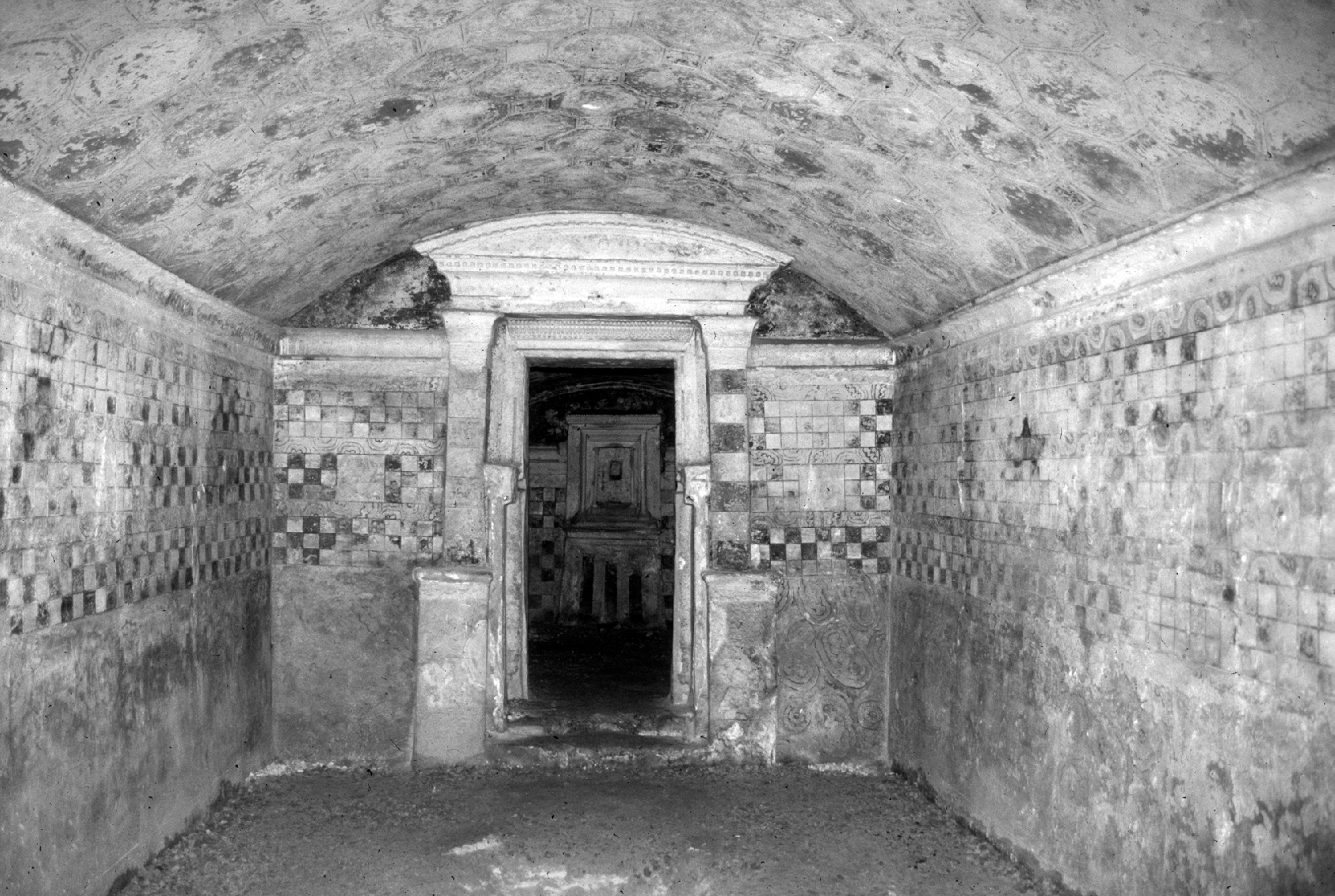

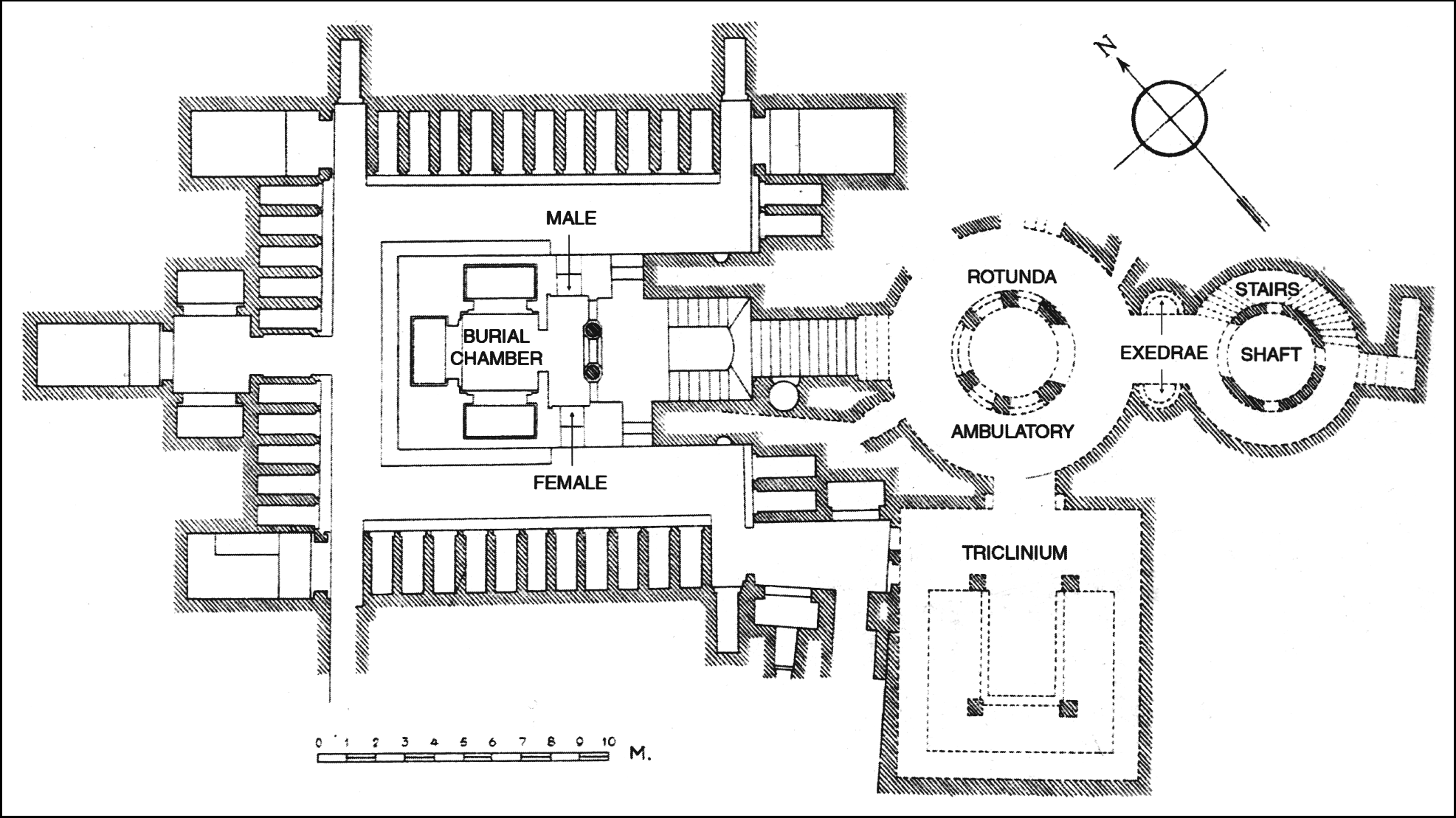

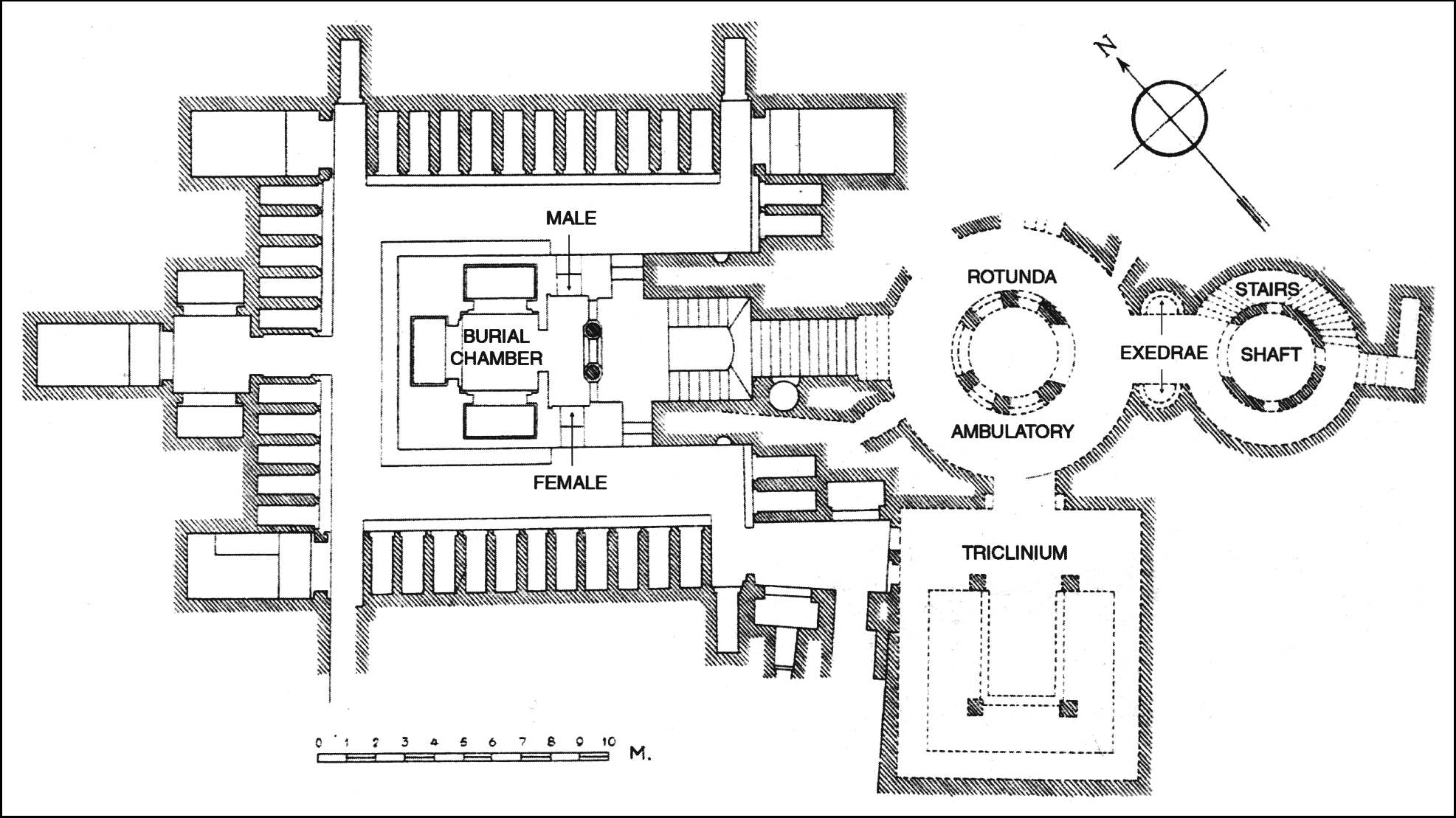

The Main Tomb in the Great Catacomb at Kom el-Shoqafa

Abutting the Nebengrab, the Great Catacomb at Kom el-Shoqafa420 is by far the best known tomb complex in Alexandria; it is visited almost daily by groups of Alexandrian school children, and it is most often the only tomb encountered by casual visitors and tourists to the city. It is a vast multiroom complex comprising at least three levels, the lowest of which has been underwater – with few fleeting exceptions – since the tomb's discovery.421 Like the Nebengrab, it adheres to a Graeco-Roman architectural model (Fig. 2.14) drawn from Graeco-Roman elements. It is accessed by a deep staircase, in its case circular, and centers on a ‘rotunda,’ which serves the physical and visual function of the central court of Ptolemaic-period tombs. It incorporates two exedrae, each covered by a Tridacna-shell-shaped half-dome – a Graeco-Roman motif unknown in pharaonic Egypt422 – and a banqueting room in the form of a triclinium for the funeral feast, the silicernium,423 and memorial repasts.424 The Main Tomb, the focus of the complex remaining above the waterline, is also in triclinium form (as are a wealth of the subsidiary tombs), and its niches shelter rock-cut, Roman-style sarcophagi serving as the metaphorical banqueting couches. Yet despite the generally Classical and specifically Alexandrian aspects of the tomb, the ensemble provides an impression of Egyptian opulence that verges on nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Egyptomania. In its case, however, the applications of Egyptian forms and the inclusion of Egyptian deities figured in Egyptian narratives are not decorative elements but are instead components essential to the meaning of the tomb's visual program.

2.14. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, Plan

Concordant with the Classical architectural disposition of the Great Catacomb, the Main Tomb assumes the plan of a Greek temple (or temple-tomb) with a naos (the burial chamber) preceded by a pronaos (the anteroom). Yet despite its underlying Classical plan, the architectural units that raise the plan assume their inspiration from Egypt.

The Pronaos of the Main Tomb

The pronaos is introduced by two columns set between antae, but these antae are egyptianized (Fig. 2.15). They take the form of engaged pilasters carved with papyrus at their foot and crowned with anta capitals in Egyptian composite form. Similarly egyptianizing, the columns rise from disc bases and, following the scheme of the antae, terminate in Egyptian composite capitals, which carry the heavy impost blocks that characterize Egyptian architecture. The reliefs carved on the architrave are egyptianizing, too, showing a central winged sun-disc flanked by a Horus falcon to either side. And, though discordantly, the architrave is capped by a row of Greek dentils, the facade is finished off with an Egyptian segmental pediment with a disc centered in its tympanum. In addition to the dissonant dentils above the architrave, another Graeco-Roman architectural element precedes the pronaos. It is a large, plastic, semicircular Tridacna-shell-shaped conch carved in the stone above the short staircases leading to that level,425 echoing the half-domes of the exedrae and visually tying the facade of the Main Tomb to the catacomb's entrance.

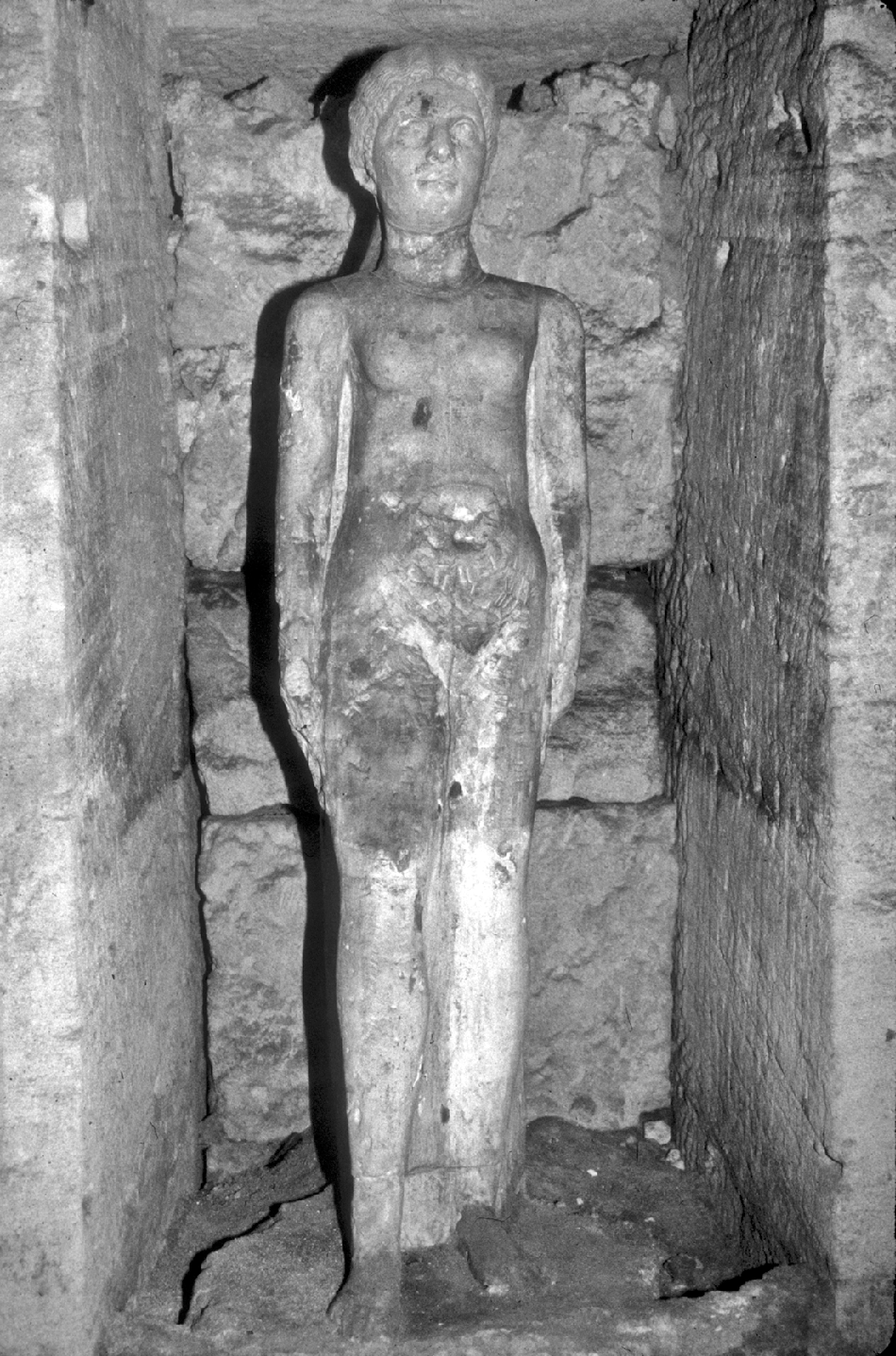

Set in niches capped with plain cavetto moldings and facing one another across the pronaos of the Main Tomb, two almost life-sized statues – one of a female, the other of a male – must be images of the tomb's patrons (Fig. 2.16 and Fig. 2.17).426 These statues are in the tradition of Roman tomb-statues, and their heads are carved in Roman style. The male has snail-like curly hair arranged above a countenance that shows a plastic treatment of his furrowed brow, the hollows under his eyes, his bony cheeks, and the deep groove and ridges that form the nasolabial fold.427 The pupil of his eye is drilled out, affording him a piercing gaze. The female's head also assumes a Roman-portrait form, and her hairstyle – the locks pulled to either side forming neat waves – is found in many classicizing works from the Greek Classical period to the Late Antique. The two portrait heads, nevertheless, suggest a date in the latter part of the first century ce for the tomb.428

2.17. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Male Statue

Yet though the male and female's portrait heads conform with those in Rome, their stance and garments immediately distinguish these statues from tomb portraits from the capital. Both figures stand with their weight evenly divided between both legs in stiff poses that have their genesis millennia past in Egypt, and instead of the expected Greek (or Roman) attire, they wear garments that also speak to Egypt's antiquity. The man wears only a shendyt-kilt,429 belted about the waist, known from Old Kingdom royal portraits430 and a type that is characteristic of the archaizing sculptures of Dynasty Twenty-six and Twenty-seven for nonroyal persons.431 It is one employed variously in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods and corresponds, too, to the type of kilt awarded the Emperor Hadrian's favorite, Antinous, in posthumous portraits that fashion him as pharaoh.432 The woman is clothed in a diaphanous garment that hugs her body and bares her ankles in a length that would be otherwise unseemly for a Greek (or Roman) matron. With their pose and garments, then, these patrons assume an intentionally Egyptian aspect. Simultaneously, however, with their portrait heads, they retain not only their Roman identity but also the specificity of their individual identity, for – despite their Egyptian pose and garb – these statues indeed appear as true portraits. The seeming verisimilitude of their faces distances these figures from all other images in the sculptural program of the tomb. It underlines the impulse toward individuality rooted in the Hellenistic world that flourished in Rome and the regions it influenced, and this verisimilitude separates these statues from Egyptian ‘portrait’ types.

The doorway to the burial room – the naos or chapel of the temple-tomb – is flanked by Agathodaimons (‘good daemons’ in the form of snakes) (see Fig. 2.15),433 which mirror one another.434 They face inward toward the opening to the burial room as they coil themselves atop stands that assume the form of a truncated Egyptian naos. Each snake is capped with an Egyptian pschent crown, signifying its connection to royalty, for in Alexandria the Agathodaimon received both public and private cults.435 But these Agathodaimons also each support a Greek thyrsus and a Greek kerykeion in its coils. The kerykeion (caduceus), a signifier of Hermes, is a common attribute of Agathodaimons on coins of Roman emperors,436 but the thyrsus is rarely, if ever, pictured with Agathodaimons elsewhere, and the coupling of the two staffs is unexpected. As the kerykeion connects the Agathodaimons with Hermes, the thyrsos connects them with Dionysos – two deities that engage multiple eschatological functions.

Within mortuary context, the kerykeion recalls Hermes as psychopompos, who leads the dead to the skiff that traverses the river Styx, and to Charon its navigator; it also connects to Hermes as chthonios, who harrows the Underworld at will. The thyrsos, for its part, activates the chthonic aspect of Dionysos,437 recalling his mysteries and his importance in afterlife religion celebrated, for example, on ‘Orphic’ gold leaves. Diodorus Siculus (Bibl. 3.65.6), writing in the first century bce, considered Orphic mystery rites the same as Dionysiac,438 and ‘Orphic’ gold leaves – which preserve poems found in mortuary context once attributed to Orpheus – confirm the connection. One ‘Orphic’ gold tablet, for example, which sets out directions for the journey, ends:

Notably, a relatively large share of Alexandria's early population derived from regions in which ‘Orphic’ gold leaves or ‘Orphic’ texts can be attested, and furthermore it has been persuasively argued that the Grand Procession of Ptolemy II, which was recorded by Kallixeinos and which must have taken place in Alexandria some time in the early 270s bce, carried ‘Orphic’ elements on its floats.440 It is possible, too, that the library at Alexandria, given the breadth of its holdings, contained scrolls with ‘Orphic’ texts.

In addition to their connection to Hermes and Dionysos, the Agathodaimons provide a formidable presence at the entrance to the tomb. Their role as guardians441 is emphasized by the Greek hoplite shields carved in low relief on the wall above them that bear apotropaic gorgoneions set within winged quatrefoils. The Agathodaimons on the exterior wall of the burial chamber provide an introduction to their protective counterparts on the corresponding interior wall of the room and render double protection for those deceased entombed within the sarcophagi of the burial room.

The Burial Room

Responding to the protective images on the exterior of the burial room, Anubis, the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis, is seen in two different aspects on the interior entrance wall of the room. Poised to either side of the doorway, the images of Anubis face toward the opening posed on the same sort of egyptianizing naos-like stands that support the Agathodaimons on the other side of the wall. One version of Anubis sees him as anthropomorphic, the other as anguiped, but although the form of the deity differs, the poses mirror one another, and each aspect is garbed in military dress.

The version of Anubis with the head of a jackal and a human body stands frontally in a differentiated pose with his weight borne by his left leg and with his head, crowned by a solar disc, turned to his right (Fig. 2.18). Assuming the pose developed for Hellenistic rulers and appropriated for Roman emperors, he holds in his upraised left hand a spear or scepter, on which he leans his weight, and with his lowered right, he holds a shield that rests on the ground. He wears a muscle cuirass with pteryges (flaps) over a short chiton and has a short sword suspended at his left hip from a baldric over his right shoulder.

Anubis in military garb is a relatively common Roman reinterpretation of the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis, although the meaning of the image is problematic. Henri Seyrig takes the military garb as apotropaic, whereas Jean-Claude Grenier and Jean Leclant give it the double meaning of protection and victory over death, and Ernst H. Kantorowicz and Roberto Paribeni see it taking its model from emperors and therefore incorporating regality.442 In the context of the image in the burial room of the Main Tomb, any, or all, of these interpretations may be correct.

The anthropoid Anubis at Kom el-Shoqafa and a similarly garbed and posed Anubis that appears on the piers of the painted Roman-period Stagni tomb from Alexandria's western necropolis443 demonstrate one aspect of the sophisticated bilingual style that contiguity with Egypt encouraged. In these images, the deity assumes his normal Egyptian cynocephalic human form, but he dresses the part of a Roman legionary as he assumes the chiastic pose that is the hallmark of classicizing sculpture. In pose, garb, and execution, the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis is refashioned in Roman terms, but he also takes on an extended meaning as his assimilation to a Roman centurion – a Roman guard, as it were, – at once reiterates and broadens his Egyptian function. This bilingualism recalls the similar iconographical efficiency of the Egyptian sphinxes crouching before the main facade in the tomb Moustapha Pasha 1 and the doorways of Anfushy Tomb II and the ba-bird of the Sāqiya Tomb. Despite the Classical heritage each acknowledges, each references Egyptian signs and symbols to create a new and more potent image of supernatural protection for its tomb.

The other entrance wall of the Main Tomb shows a more exceptional version of Anubis: he is in similar martial form but with a snaky tail instead of human legs (Fig. 2.19). Garbed similarly to the anthropoid Anubis, he adds only a short chlamys pinned on his right shoulder and replaces the solar disc with an atef crown. He holds a spear in his upraised right hand and grasps the end of his chlamys with his left.444 Despite (or perhaps because of) his uncanonical form, this figure must be the primary one of the two because he supports his weapon in his correct right hand.445 The image of an anguiped Anubis is very rare, but not unknown beyond his depiction in the Main Tomb, though none finds Anubis garbed as a Roman legionary.446 Nevertheless, Anubis in anguiped form is exceptional, and the snaky-legged Anubis as a Roman soldier is currently unique to the Main Tomb, where he responds to and reiterates the function of the Agathodaimons on the exterior wall. The image exemplifies – as does the abduction of Persephone in the ‘Hall of Caracalla’ niche – the iconoclastic creativity of the Alexandrian artists. It stands as yet another example of the intentional integration of Roman and Egyptian conceptual and formal elements employed by Alexandrians to produce a new means of expression in a city whose population had accumulated the knowledge to address this complex past. These images of Anubis (and the ones on the piers of the Stagni tomb) also perpetuate the ancient Greek tradition of ‘monsters’ guarding the tomb, seen in Alexandria in the sphinxes in Moustapha Pasha Tomb 1 and Anfushy Tomb II, the ba-bird of the Sāqiya Tomb sarcophagus, and the Agathodaimons and gorgoneion shield emblems on the exterior of the burial chamber of the Main Tomb.

The plan of the burial chamber of the Main Tomb, in consonance with the generally Classical plan of the entire tomb, assumes a Roman form. Trabeated niches (but with arced ceilings) cut into its walls create its cruciform plan, and a rock-cut sarcophagus set into each of the niches gives the room its triclinium aspect.447 Apart from being a Roman modification of the kline chamber, and in addition to the triclinium form specifically identifying the sarcophagi as metaphorical banqueting couches as suggested earlier in this chapter, other considerations may also have prompted the cutting of triclinium-shaped burial rooms in Roman-period tombs. Certainly, the Great Catacomb's real, usable triclinium fitted out with rock-cut klinai near the tomb's entrance demonstrates the importance of the funerary feast that took place at the tomb and the memorial meals that would have occurred during the year in commemoration of the dead, and the Totenmahl reliefs – one of the standard motifs for Roman gravestones in the Egyptian chora448 – which, by placing the deceased at a hero's banquet, heroized him or her, may have propelled the eschatological impulse to memorialize the banquet of the dead in architectural form.449

In contrast to the triclinium plan, but in concert with the Egyptian architectural elements in the pronaos of the tomb, each of the three niches of the triclinium-shaped burial chamber is defined by engaged piers carved to repeat those of the antechamber. Yet antithetical to the architectural framework of the niche, each niche in the Main Tomb encloses a fully realized Roman garland sarcophagus,450 and each narrative that enlivens the walls of the niches is framed above with a Classical egg-and-dart motif. Nevertheless, complementing the piers, the figural decoration of the Main Tomb is also egyptianizing. Consonant with the two versions of Anubis on the entrance wall that fuse Egyptian and Graeco-Roman traditions, egyptianized narratives decorate the back and side walls of the niches above the Roman sarcophagi, according the niches their bilinguality.

The symmetry of the cruciform-shaped room is emphasized both by its figural decoration and by the treatment of the sarcophagus facades, for though all the sarcophagi are carved as garland sarcophagi, details of the garland of the central sarcophagus differ from those of the other two. Their major motifs remain the same, however, and the duplication of these motifs underscores the intention of the ornament: all sarcophagi show frontal heads (or masks) of apotropaic figures. The central sarcophagus fastens a gorgoneion and a frontal satyr head to the circlet that pins the garland to the wall (Fig. 2.20) and the lateral ones fix two gorgoneions to the background wall in the semicircles created above the swags. Protective devices thus reach their apogee in the Main Tomb, which is multiply protected by the gorgoneions emblazoned on the hoplite shields and the Agathodaimons on the exterior of the chamber, the two versions of the militaristic Anubis facing the doorway on the chamber's interior wall, and the gorgoneions and satyr masks on the room's sarcophagi.

In accord with the details of the sarcophagus decoration, the Main Tomb's symmetry is further enhanced by the figurative treatment of the walls of the niches. Recalling the upper scenes on the back walls of the Persephone tombs in the Nebengrab, as well as those depicted in other tombs in Alexandria, the back wall of the Main Tomb's central niche shows the lustration of the mummy (see Fig. 2.20). Nevertheless, despite the frequency of the lustration scene in the tombs at Kom el-Shoqafa and elsewhere in Alexandria, few mummies are found in the catacombs at Kom el-Shoqafa, and few mummies – or traces of mummies – have been found in Alexandria at all. Unlike elsewhere in Roman-period Egypt, in Alexandria the appropriation of mummification is not based on the physicality of mummification but on the use of the imagery of mummification – and often its extended narrative – to visualize Greeks’ own concepts of the afterlife.

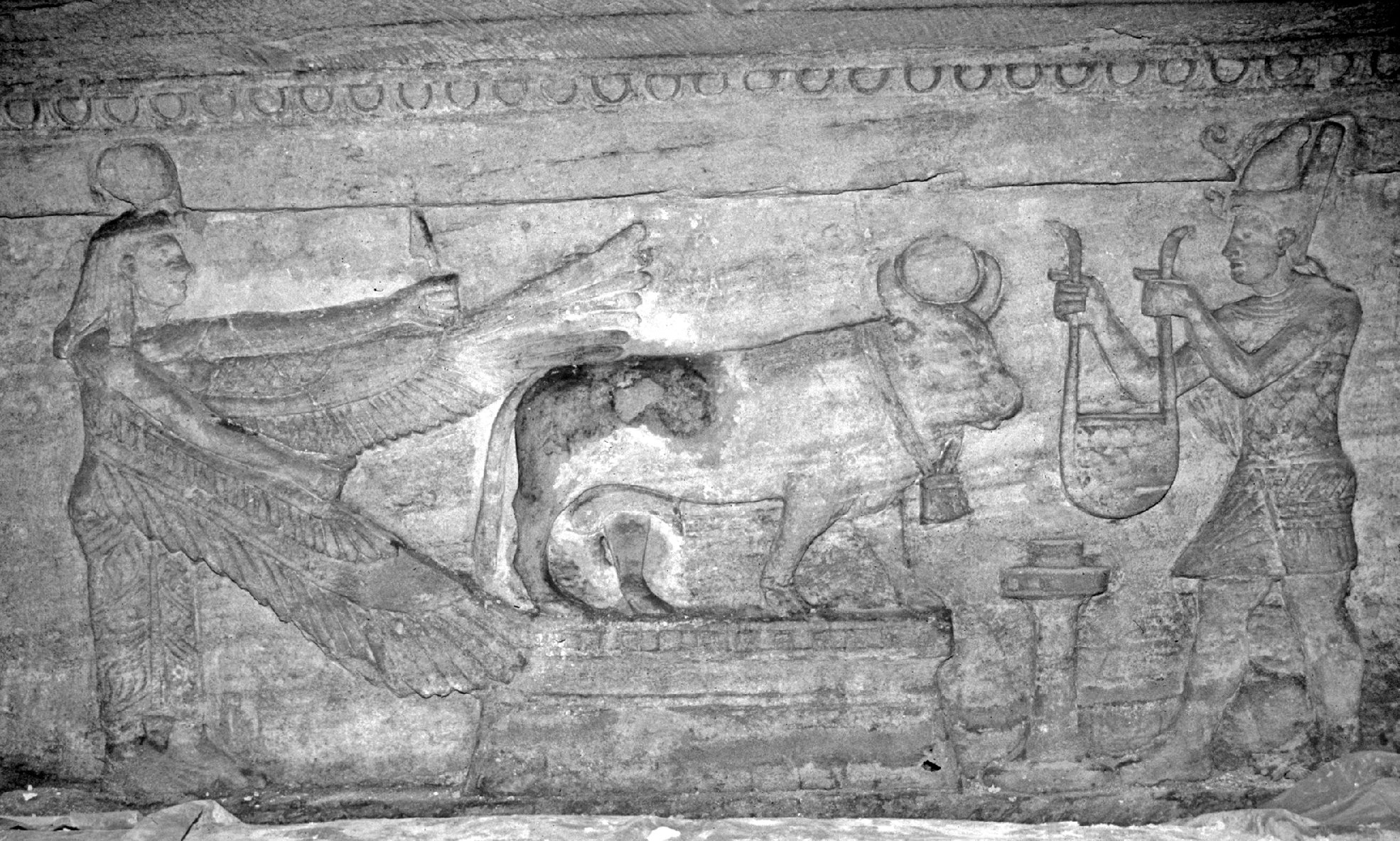

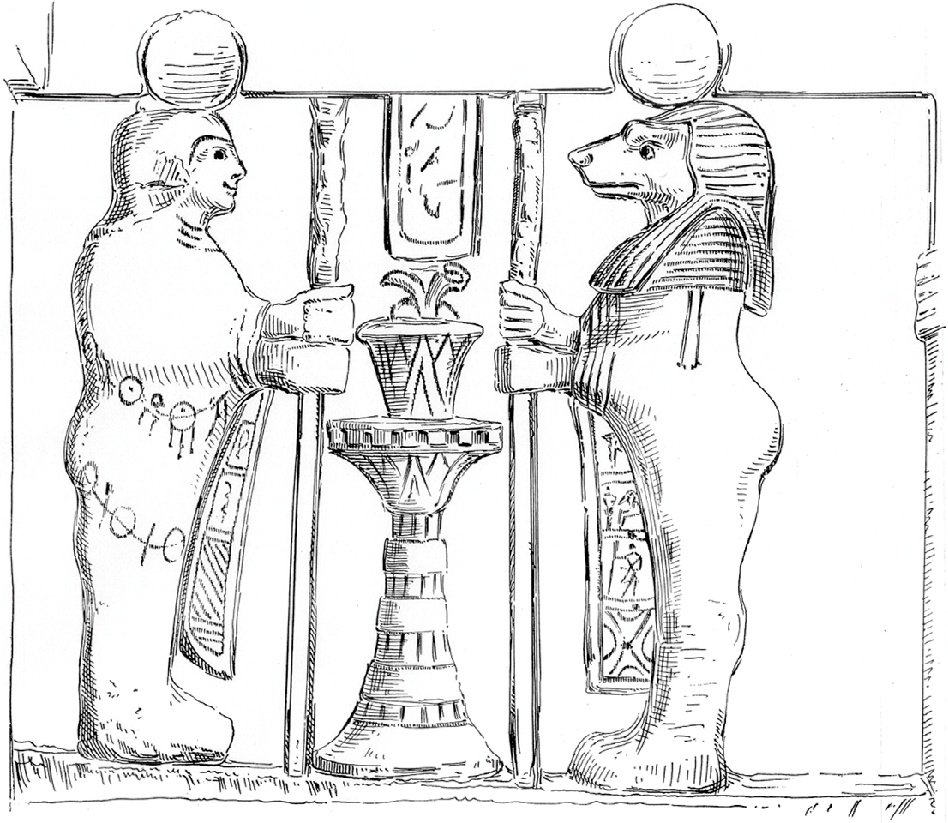

In contrast to the frequency of the theme of the back wall of the central niche in Alexandria, the back walls of the left and right niche – which are almost perfect mirror images of one another – show scenes that are unique in Alexandria. Each lateral niche embraces an image of the Apis bull standing on a truncated naos-like pedestal. He is sheltered by the wings of Isis-Ma'at who stands behind him, holding out the ostrich feather of truth in her farther hand. In front of him, across a small altar, a male in a kilt and corset, a short mantle slung across his neck, and wearing a pschent crown holds out a decorated collar (Figs. 2.21 and 2.22). Unless the royal crown is used cavalierly, the male figure should be an Egyptian pharaoh or a Roman emperor in his Egyptian manifestation.

2.21. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Back Wall of Right Niche

2.22. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Back Wall of Left Niche

Though the central niche is privileged by its unduplicated subject, compositionally uniting the three scenes on the back walls of the niches is their general bilateral symmetry, although the Apis bulls, which face toward the rear of the tomb, permit the scenes on the left and right walls to appear directional. All scenes admit anomalies, but none of these deviations are especially out of place in a Roman-period context.451

In contrast to the back wall of the central niche, which is singled out by its subject, the lateral walls of all the niches are treated similarly. All admit symmetrically disposed two-figure compositions, though the characters depicted and their gestures differ, and all the figures face one another across an altar that is raised on variously shaped stands.

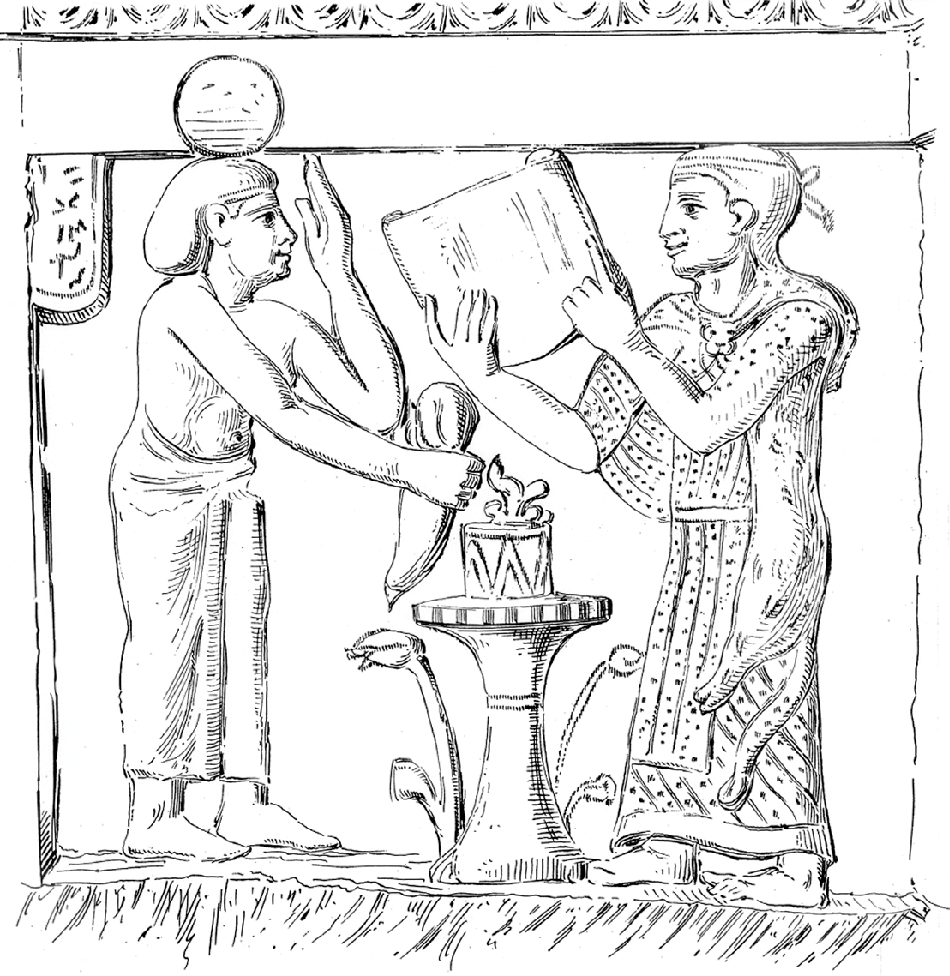

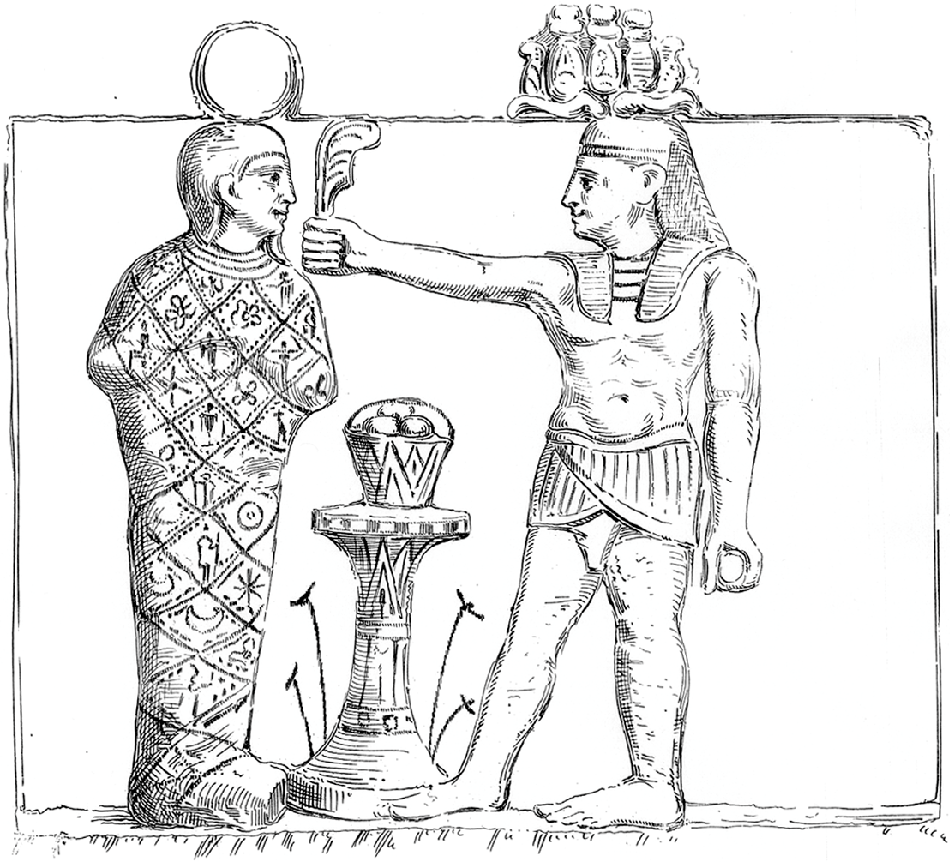

The left wall of the central niche depicts a male figure facing a priest across the altar, on which a fire burns within a cylindrical vessel, probably filled with incense (Fig. 2.23).452 The male figure,453 crowned with a solar disc, wears only a long garment bound about his waist. In his right hand he holds out an object difficult to interpret; it appears to be flexible and soft, and although it does not precisely replicate the traditional Egyptian form, it might be the ubiquitous srips of linen – “fabric bands that signify rebirth”454 – that mortuary figures often hold. He bends slightly and awkwardly from the waist and raises his left hand to his face in the Greek male gesture of mourning. Behind him is a partial cartouche with pseudo-hieroglyphs that reoccurs in all the two-figure scenes. Opposite the mourning male, a lector priest, barefoot and wearing a long, wrapped garment with a panther skin draped over it, holds up a scroll from which he reads out the appropriate spells.

The priest on the right wall of the central niche faces a woman across the altar (Fig. 2.24). The two feathers the priest wears in his headband identify him as a pterophoros (wearer of feathers), a hierogrammatos or sacred scribe in the cult of Isis.455 Like the priest on the left-hand wall, he wears a long garment, but his is slightly shorter, of thicker cloth, and differently arranged and decorated, and the animal skin that denotes his office is also differently draped. He holds out a lotus (?) in his right hand and extends a plate that supports a spouted lustration vessel in his upraised left. The woman who faces him across the altar wears a layered wig and a long, clinging, fringed garment that permits a view of her body underneath. Like her male counterpart, she is crowned with a solar disc.456

2.24. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Right Wall of the Central Niche

The scenes on the side walls of the lateral niches present other characters, and, like the scenes on their back walls, they correspond to one another, though they lack the almost perfect mirror-imaging of the scenes at the rear of the niches.

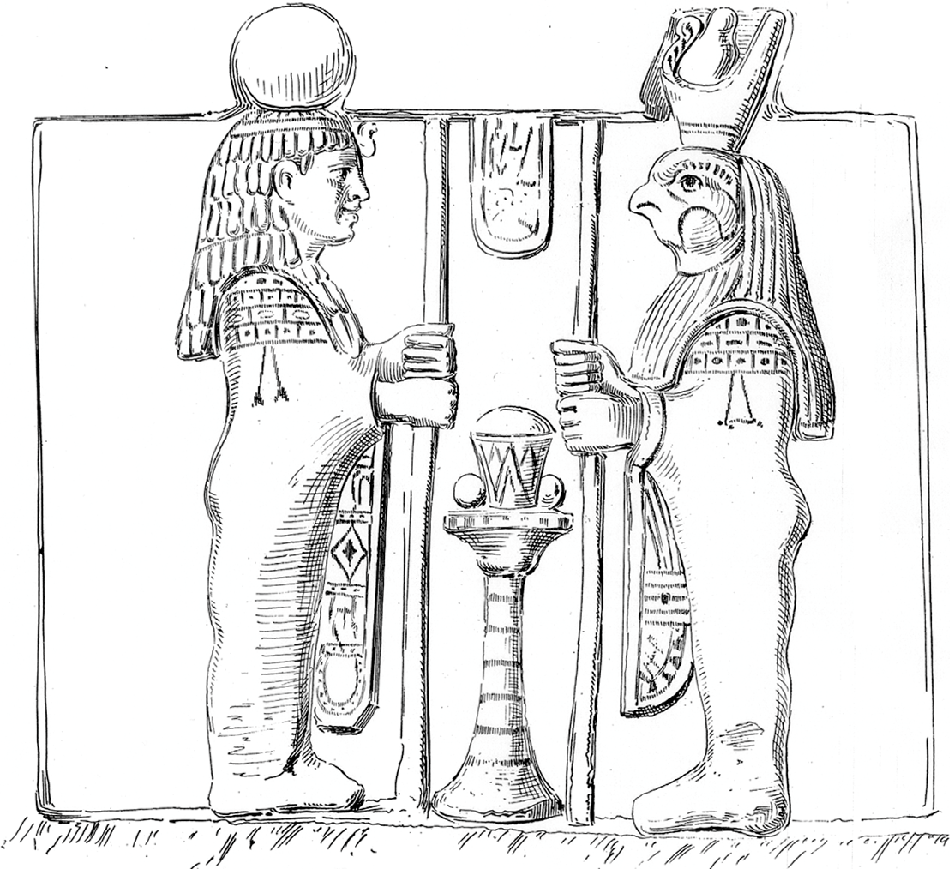

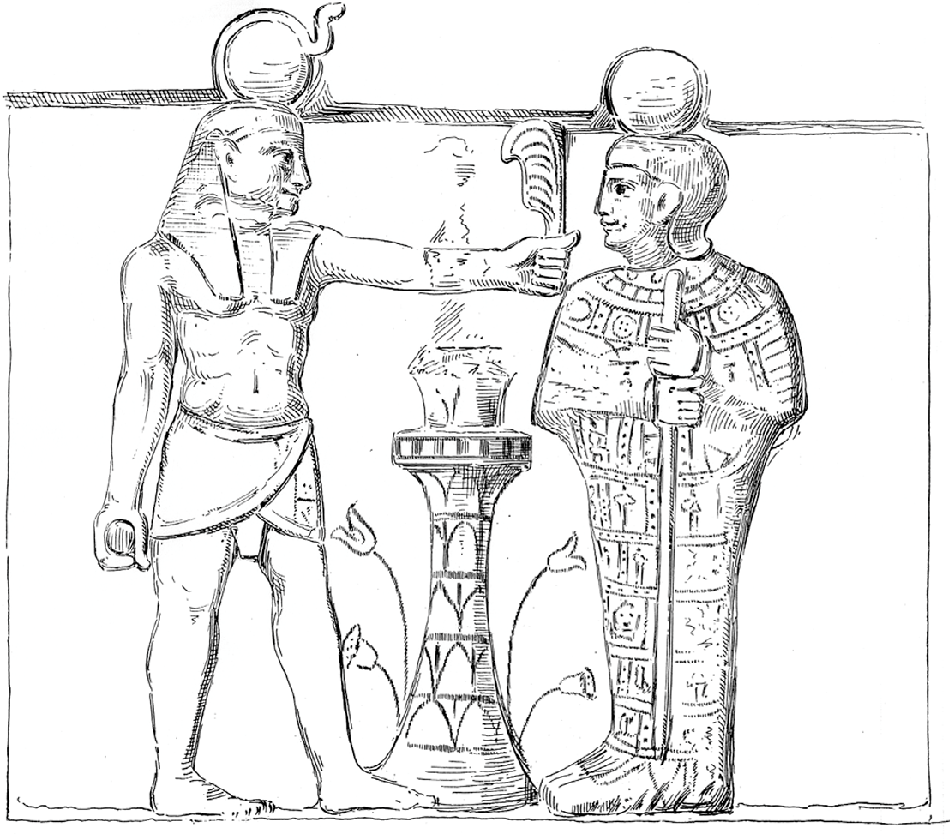

On the left wall of left niche, a female wrapped in a tight garment faces the falcon-headed son of Horus, Qebehsenuef, who wears a pschent crown (Fig. 2.25). Unlike most of the figures in the confrontations on the short walls, these figures are in true profile. Each figure holds a scepter in hands that emerge from its tightly wrapped garment, and each has a decorated swath of fabric pulled tightly across its shoulders that falls vertically in front of its body so that its decoration is visible. Sons of Horus normally do not wear crowns or hold staffs,457 but Qebehsenuef's crown and scepter accord with the generally regal tone encountered throughout the imagery of the Main Tomb. The female figure wears a layered wig and a band fronted by a uraeus across her forehead, and she is crowned with a solar disc like the male and female in the lateral walls of the central niche. Rowe interprets her as Isis,458 but given the symmetry of the decoration, this figure – which corresponds to a male figure directly across the tomb on the right wall of the right niche – is unlikely to be an Egyptian deity, and the solar crown demands another explanation.

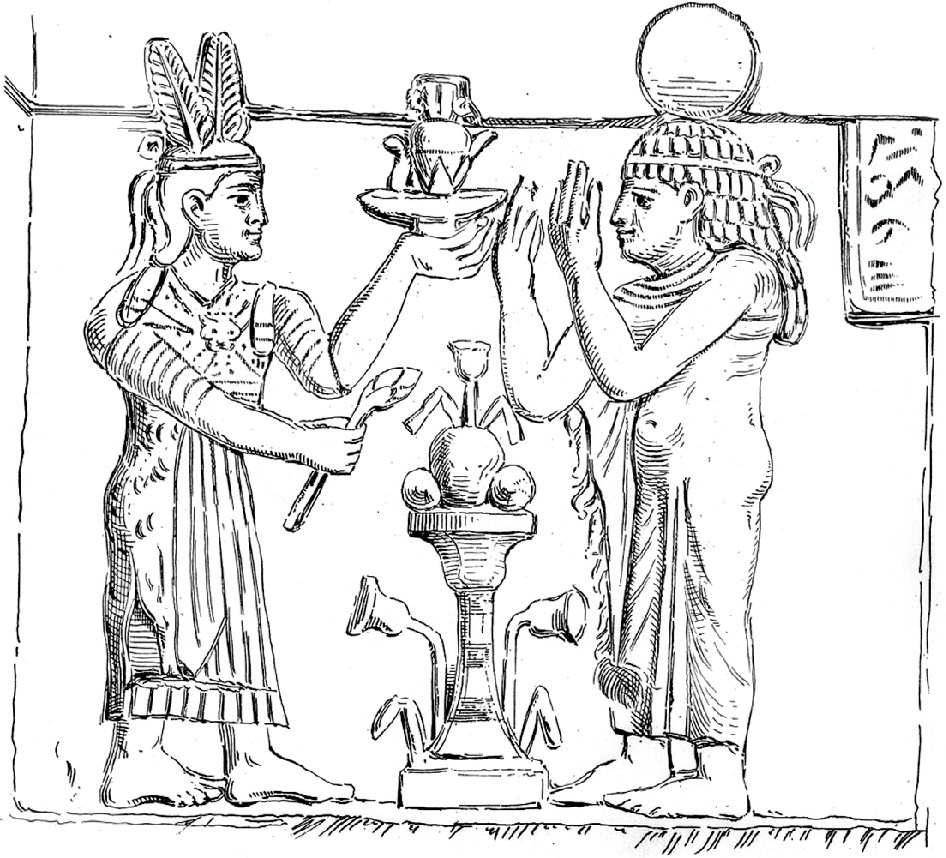

On the right wall of the left-hand niche, a figure that is completely mummiform faces a pharaoh, who is nude but for a shendyt-kilt, a pectoral, and a nemes capped with a hem-hem crown (Fig. 2.26). The pharaoh holds the rolled cloth of authority in his lowered left hand, which is no longer extant,459 and extends the feather of Ma'at toward the mummy with his right. The male mummy-like figure, who wears a false beard and is crowned with a solar disc, stands properly in the Egyptian composite stance with his face and feet in profile and upper body frontal, but remarkably his arms and joined hands appear plastically indicated beneath his garment. The garment itself is crossed with a diamond pattern, a simplification of the reticulated bandaging characteristic of Roman-period mummies, and in each diamond-shaped coffer, varied signs seem to denote bodies associated with the celestial realm.460

2.26. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Right Wall of the Left Niche

The composition of the left wall of the right niche (Fig. 2.27) mirrors that of the right wall of the left niche (see Fig. 2.26) although the details differ. The pharaoh, or Roman emperor in the guise of pharaoh, is crowned with a solar disc fronted by a uraeus instead of a hem-hem crown, and he extends the feather of truth to a mummiform figure who holds a staff in his hands.461 This figure stands in the same composite pose as the one of the right wall of the left niche, but his hands emerge from his mummiform cloak to grasp a staff. In contrast to the garment of the first mummy-like figure, his garment is patterned with a horizontal-vertical grid – one that is also employed to distinguish mummy bandages – which contains less-readable signs in the boxes created.

2.27. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Left Wall of the Right Niche

The right wall of the right niche (Fig. 2.28) follows the structure of the left wall of the left niche (see Fig. 2.25). A mummiform male figure faces Hapy, the baboon-headed son of Horus, both figures confronting one another in true profile stances. Both are crowned with solar discs, and both have decorated swaths of fabric falling vertically in front of their bodies, as do the figures on the left wall of the left niche,462 but the male adds two strings of amulets looped across its lower body. Alan Rowe identifies the male figure as Imsety,463 another of the sons of Horus, but this identification is improbable. The lateral scenes in the side niches correspond so closely to one another that it would be remarkable if the male were meant as Imsety (or any deity), given the complementary female figure that he parallels.464

Clearly a strongly symmetrical structure underlies not only the architecture of the burial room, but also constitutes the impetus behind its pictorial program. The lustration scene of the central niche is flanked to left and right by priests facing human figures, a male on one side and a female of the other. Both male and female face inward, toward the back of the niche and, consequently, toward the back of the tomb. The side niches complete the symmetrical arrangement, for not only do the central scenes of the lateral niches mirror one another, but a direct correspondence between their left and right walls augments the symmetry. Hapy and Qebehsenuef are paired across from one another on the lateral walls closest to the entrance to the tomb. The two mummy-like figures face one another across the royal figures that engage them and who stand back to back across the room. This precise conceptual parallelism demands that a unified program must govern all the figured scenes in the niches.

In Monumental Tombs of Ancient Alexandria, I argued for the identification of the ‘emperor’ in the large panels in the lateral niches as Vespasian.465 It is indeed possible that Vespasian is honored here, but Rowe, more perceptively, sees the emperor on the left wall of the right niche who wears the solar-disc crown as deceased and the one who wears the hem-hem crown as his live successor.466 I now think, however, as is evident from my description of the scenes, that the precise identity of the royal figure may be of less consequence than his station, and I address this concern later. In Monumental Tombs, I followed, to a great extent, Rowe's identification of the nonroyal figures on the walls of the Main Tomb, but I now think that neither he nor I was correct. Jean-Yves Empereur initially queried the identity of the mummy-like figure with the staff as other than a mummy,467 and I discounted his interpretation, noting that he had ignored the figure's staff. With respect to his perspicacity, I should like to revisit the identification of the all the figures in the room in an attempt to unravel the meaning of the sculpted program of the burial chamber.