Introduction

While the economic integration of EU member states has proceeded further than most would initially have anticipated, the impact of the EU as a political project has not been equally successful. Empirical evidence suggests that European integration has proceeded via a technocratic mode and that the EU has not yet succeeded in creating European demos or fostering a European identity. Adding to that, the various crises in which the EU has been engulfed since the mid-2000s have triggered eurosceptic dynamics and challenged the notion of Europe as a whole (Jones Reference Jones2012).

These developments have revitalised interest in European identity politics, thus, leading to the emergence of novel postfunctional theories of European integration developed on the grounds of identity-based factors (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Hutter, Grande, and Kriesi Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). The re-emergence of European identity as a salient topic can also be seen in the light of the current state of transatlantic relations and how Europe needs to present a united front. Scholars tend to agree that support for and identification with the European project are necessary elements for the EU to foster its legitimacy (Mendez and Bachtler Reference Mendez and Bachtler2017) and to sustain itself as a political regime (Bellucci, Sanders, and Serricchio Reference Bellucci, Sanders, Serricchio, Sanders, Bellucci, Tóka and Torcal2012). While the bulk of research on European identity is concerned with identity formation at the citizens’ level, the level of policy elites remains underexplored. As such, a critical question is whether policy elites, enmeshed in the EU’s multilevel governance (MLG) system,Footnote 1 have adhered to the political goals of the EU and whether this has translated into the formation of a shared European identity.

The EU socialisation framework, which focuses on the socialising role of EU institutions and examines the process whereby actors are induced into the rules and collective understandings of a given community, is analytically relevant and useful to address this question. The scholarship has so far focused on how socialisation takes place among EU officials and national representatives interacting in the various Brussels-based committees. This article follows the less explored perspective of socialisation dynamics among policy elite actors at the national and the subnational levels, thus, offering novel insights on when and how EU socialisation takes place at lower government levels. The MLG policy model implies interaction and collaboration between state actors representing all three government levels. It is assumed that it is in the context of this interaction that normative ideas about political goals, consolidated at the supranational level, can be diffused at the national and the subnational levels. A key mechanism of socialisation is then identified and analysed: that is, discourse. In particular, the analysis examines whether the coordinative discourse, developed among policy actors at different government levels, and the communicative discourse, taking place between political actors and the general public, include normative ideas about political goals and whether this can lead policy actors and the public to socialise into EU normative ideas and shape a shared European identity.

The analysis employs as a case study the field of Cohesion Policy. This is so because this is a major EU policy aiming to bring greater economic, social, and territorial cohesion across and within European regions, while its political goals are closely intertwined with its economic ones. More specifically, the article delves into the formation, implementation, and communication of Cohesion Policy during the period 2000 – 20 in three European regions: Wales in the UK, Crete in Greece, and Silesia in Poland. While the UK is no longer part of the EU, Brexit makes it even more important to include it in the discussion. The three cases are instructive in terms of understanding the EU’s limited success in building a shared identity among national and subnational elites as well as among the public independently of the national/regional context.

The article contributes to the scholarship on European identity politics by arguing that the MLG policy model and the way EU public policies are designed, implemented, and communicated do not favour – and may even obstruct – the achievement of political goals, such as the cultivation of a shared European identity. It also complements existing research on Cohesion Policy-induced identification with Europe by providing evidence on the elite perspective and echoing accounts suggesting that the impact of the policy on European identity-building has been limited as well as accounts indicating communication deficits and poor EU communication strategies. Lastly, the article contributes to the research on EU socialisation and discourse by providing empirical evidence on the content of coordinative and communicative discourse about EU public policies and the reasons why normative ideas about political goals are crowded out of them.

The article is organised as follows: First, the relevance of Cohesion Policy to the promotion of EU political goals and the reasons why its economic goals have to be understood as closely intertwined are discussed. The next section addresses the suitability of social constructivist and discursive approaches to the study of ideational aspects of policy-making and identity formation, followed by an overview of the EU socialisation and discourse analytical frameworks. Then, the study’s case selection rationale and data are presented. The analysis proceeds with the empirical material, discussed in a comparative perspective. The paper concludes by discussing its theoretical contribution to the field of EU studies while also offering avenues for further research and policy recommendations.

EU Cohesion Policy: A policy with closely intertwined political and economic goals

The goal of Cohesion Policy, as initially stated in Article 130a of the 1986 Single European Act, has been to ‘reduce disparities between the various regions and the backwardness of the least-favoured regions’. This has been pursued through the less abstract objective of reducing regional disparities in GDP compared with the EU average, which has, in turn, been broken down into narrower targets such as increasing employment and economic activity and promoting social inclusion. The targets of Cohesion Policy have changed considerably over time as a result of a series of internal and external factors such as EU enlargements and treaty reforms. These shifts have also been informed by the changing economic assumptions driving the EU’s broader developmental model (Piattoni and Polverari Reference Piattoni, Polverari, Piattoni and Polverari2016). Meanwhile, place-based policy shifts within member states, such as devolution and decentralisation, have had an impact upon the structure of Cohesion Policy and the organisational/functional systems governing the planning and management of EU-funded regional programmes (Manzella and Mendez Reference Manzella and Mendez2009: 21).

Cohesion Policy has gradually become more ‘all-encompassing’ with Structural Funds being directed towards investments in a wide range of sectors. While this has provided member states and their regions with some flexibility to select the interventions that better suit their needs, it has also presented a challenge: a possible risk that Cohesion Policy will lose its ‘identity’ and lose sight of its underlying mission to promote convergence and cohesion. Piattoni and Polverari (Reference Piattoni, Polverari, Piattoni and Polverari2016) have advanced a similar argument, asserting that, if Cohesion Policy continues to direct resources into too many sectors, it might end up achieving nothing because of the thin dispersion of resources. Adding to that, possible tensions between different approaches to regional development could result in Cohesion Policy being ‘accused’ of lacking policy clarity in terms of pursued objectives. In that regard, Keating (Reference Keating2013) has stressed the tension between convergence/cohesion and the policy assumption of improving regional competitiveness. It is obvious that these two objectives are not entirely aligned and that they can even pull in different directions. While the economic goal of Cohesion Policy is open to different interpretations (e.g., convergence versus competitiveness), the political one, reflected in the very term ‘cohesion’, is a straightforward one.

The Thomson Report had acknowledged the political agenda in the European Community regional policy, the predecessor of Cohesion Policy, as early as the mid-1970s, setting out the ideas of unity and solidarity as lying at the heart of the policy (European Commission 1973: 12 – 13, 19). It has thus been argued that ‘Cohesion Policy has assumed since the beginning the political objective of laying down the principles of mutual solidarity’ (Leonardi Reference Leonardi2005: xiii). The political goal of the policy was institutionalised by the Single European Act and reaffirmed in all subsequent treaty reforms, while ‘cohesion’ became a broader European objective. Leonardi (Reference Leonardi2005) has stressed that convergence is the means through which cohesion is pursued, implying that the key goal of Cohesion Policy is a political one. It is from that perspective that this study advances the argument that the political goals have to be understood as being closely intertwined with the economic ones.

Taking the above into consideration, it is quite surprising that Cohesion Policy has attracted relatively little attention within the scholarship on European identity politics. Existing research, concerned almost exclusively with the citizens’ perspective, has resulted in mixed findings. While some studies employing data on public opinion surveys and allocations of Structural Funds at the regional level have reported a positive effect of the latter on public support for the EU (Osterloh Reference Osterloh2011; Borz, Brandenburg, and Mendez Reference Borz, Brandenburg and Mendez2022), others have stressed that such an effect is conditional upon a series of individual-level factors such as pre-existing perceptions about the EU, socio-economic background and level of education (Verhaegen and Hooghe Reference Verhaegen and Hooghe2015; Dellmuth and Chalmers Reference Dellmuth and Chalmers2018). Notwithstanding the inconclusiveness of this scholarship, what is worth noting is the lack of accounts investigating the influence of the policy on attitude formation and European identity-building among policy elite actors (with the exception of Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2011 and Bachtler, Mendez, and Oraze Reference Bachtler, Mendez and Oraze2014). Yet, the latter accounts do not conceptualise identity as the dependent variable and lack sufficient consideration of the mechanisms through which normative ideas are being diffused among policy elite actors at different government levels, the determinants of EU socialisation for actors operating at each level, and how possible divergent degrees of socialisation might affect the perceptions and attitudes of each towards the EU.

Theoretical framework

The article employs a social constructivist and discursive approach to the study of policy-making to bring to the fore the cognitive dimension of institutional impact. At the most general level, constructivists postulate that institutional and ideational environments interact, thus shaping actors’ interests, self-images, and, possibly, their very sense of identity, on the basis of norms and values rather than just narrow self-interest. In contrast to rational choice approaches, where institutions are treated as static structures with fixed rationalist preferences, constructivists assume that ‘actors and structures are co-constituted’ (Saurugger Reference Saurugger2013: 890). This fundamental disagreement is captured by the contrast between two logics: a logic of consequentialism and a logic of appropriateness. The first reflects the rationalist assumption that actors will behave according to whether they will benefit from or lose out because of their actions, whereas the second reflects the constructivist thesis that actors’ behaviour will be guided by what is acceptable in a given context (March and Olsen 1989; Reference March and Olsen2004).

For the purposes of this study, discursive institutionalism is also analytically relevant and useful. Developed as a fourth strand of the new institutionalism account – alongside the traditional approaches of rational choice institutionalism (RI), historical institutionalism (HI), and sociological institutionalism (SI) – discursive institutionalism draws from a logic of communication. In contrast to the basic premises of the three older approaches – namely rationalist preferences (RI), historical paths (HI) and cultural norms (SI) – it places ideas and discourse at the core of institutional analysis (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2002; Reference Schmidt2006). Arguably, this allows for a more dynamic approach to institutional analysis. To shed light on whether policy elites have adhered to EU political goals and whether this has translated into the formation of a shared European identity, the article draws from the logics of appropriateness and communication, and adopts a socialisation framework, approached through the lens of discourse.

The EU socialisation framework

Socialisation is the process whereby actors are induced into the rules and collective understandings of a given community (Checkel Reference Checkel2005). Socialisation can take place in different settings, via different mechanisms and following different modes of rationality. In the EU context, socialisation research focuses primarily on the socialising role of EU institutions and how the acceptance of collective norms on the part of socialisation ‘targets’ has an impact upon policy-making processes. The socialisation ‘targets’ can be countries and individual policymakers. In Europeanisation analysis, socialisation is framed as a soft Europeanisation mechanism able to inform change outside adaptational pressures (Radaelli Reference Radaelli, Featherstone and Radaelli2003).

The bulk of empirical research in this area still concentrates on how socialisation takes place between individual policymakers, most notably the officials of European institutions (Hooghe Reference Hooghe2005; Suvarierol, Busuioc, and Groenleer Reference Suvarierol, Busuioc and Groenleer2013) and members of European Council committees, the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER), and other interest groups active in Brussels (Lewis Reference Lewis2005; Beyers Reference Beyers2005; Trondal, Van Den Berg, and Suvarierol Reference Trondal, Van Den Berg and Suvarierol2008; Quaglia, De Francesco, and Radaelli Reference Quaglia, De Francesco and Radaelli2008). With regard to EU officials, most scholars acknowledge the existence of ‘an esprit de corps’ (Georgakakis Reference Georgakakis, Beck and Thedjeck2008), a feeling that the former have embraced the spirit of working for Europe ‘in the sense of adopting supranational norms and serving the overarching interests of Europe above and beyond particular national or professional interests’ (Suvarierol, Busuioc, and Groenleer Reference Suvarierol, Busuioc and Groenleer2013: 908). This yet may also be owing to personal gain from being involved with the EU (Niskanen Reference Niskanen1968) or a pre-existing positive inclination towards EU values before joining the EU institutions (Hooghe Reference Hooghe2005). With reference to national officials interacting through the various Brussels-based committees and elsewhere, most scholars suggest that socialisation effects are usually weak and/or subject to domestic-level factors (Beyers Reference Beyers2005; Hooghe Reference Hooghe2005).

Yet, the socialisation literature has not addressed the question of how subnational-level actors can become socialised into EU norms and values. Within the framework of Cohesion Policy, the European Commission (notably the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy [DG REGIO]), the European Council, and the Committee of the Regions are the main sites for national- and subnational-level actors’ possible socialisation. In particular, socialisation could result from their sustained interaction as well as the exchange engaged in during events such as the European Week of Regions and Cities. Notwithstanding the fact that the notion of European identity is broad and might be affected by a plurality of variables outside the area of EU policies, including Cohesion Policy, it is postulated that socialisation can primarily be a by-product of policy elite actors’ daily collaboration for the implementation of EU policies. Departing then from the thesis that EU officials have become socialised into EU normative ideas, it is assumed that they have the capacity to induce national- and subnational-level actors to take up these ideas, thus acting as ‘socialisation agents’. The literature has so far focused on policy areas which fall within the competence of member states, suggesting that socialisation is more likely to occur in the absence of binding EU regulations. This is explained by the underlying assumption that, in cases where the EU has more competences, socialisation will not be necessary, because change will occur as an outcome of hard mechanisms such as directives. What is missing altogether from the existing body of literature (with the exception of Lewis Reference Lewis2005) is evidence on EU-policies-induced socialisation dynamics and/or how socialisation processes vary between different types of policies.

While the scholarship on socialisation is not explicitly concerned with the construction of a shared European identity (Saurugger Reference Saurugger2013), the framework is still useful for understanding how normative ideas about political goals are diffused in an MLG system and how policy elites perceive their role in their engagement with EU institutions. In that regard, drawing from Zürn and Checkel’s (Reference Zürn and Checkel2005) argument that socialisation can be influenced, among others, by the properties of the norms that are being transferred, discourse is identified as a key socialisation mechanism.

Discourse as a socialisation mechanism

The application of discursive institutionalism to the study of the EU has made discourse an integral part of Europeanisation analysis, where the former is approached as a mechanism of the latter (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2002). Discourse is conceptualised as language, either in the form of rhetoric (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001) or policy narratives (Radaelli Reference Radaelli1999), and as the interactive process of conveying specific sets of ideas with transformative power (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). In practical terms, this means that to fully grasp the explanatory power of discourse, it is necessary to take into consideration not only the structure, meaning what is said and in which context, but also agency, referring to who is saying what to whom (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). Both elements are important in view of the article’s argument meaning that, besides being a mechanism of Europeanisation, discourse is also a mechanism of socialisation.

With reference to structure, Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2008) has distinguished between two types of ideas, cognitive and normative. Cognitive ideas refer to the more practical aspects guiding political action, for instance, what makes policies necessary and the means through which they can achieve their goals. Normative ideas attach values to these aspects. By referring to commonly perceived conceptions as socially appropriate rules, normative ideas serve the purpose of legitimising actions or policies (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989). It becomes clear that the ‘idea’ that is of interest to this study, that is, European identity-building through EU policies, is a normative one. This raises the question of whether normative ideas about political goals are incorporated – alongside cognitive ones – into the discourse about EU policies. To provide an answer, it is essential to shift the focus of analysis from structure to agency, in other words, to ask who is the carrier of ideas and to whom ideas are conveyed.

To that end, the literature has distinguished between two types of discourse, coordinative discourse and communicative discourse. The first occurs in the policy sphere, whereas the second operates in the political sphere. More specifically, the coordinative discourse revolves around the formulation of policy ideas and takes place among policy elite actors, most notably civil servants, elected officials, and expert groups within advocacy coalitions and epistemic communities (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). The communicative discourse emerges between political actors and the general public and serves the purpose of communicating and legitimising these ideas (Mutz, Sniderman, and Brody Reference Mutz, Sniderman and Brody1996).

The EU polity has been characterised as having a strong coordinative discourse and a weak communicative one (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2006). While the quasi-federal structures governing EU policy-making allow for the development of a solid discourse in the policy sphere, the absence of directly elected bodies – with the exception of the European Parliament – at the EU level leaves the task of communication entirely to national governments. However, what happens within member states and how discursive processes take place between different government levels, especially at the subnational level, has not been adequately explored. In effect, the assumption that the EU has a strong coordinative discourse and a weak communicative discourse captures how cognitive ideas relating to EU policies are formulated, conveyed, and legitimised in an MLG system. When it comes to normative ideas about political goals, it is expected that discursive processes of coordination will be ‘less strong’ and discursive processes of communication will be ‘even weaker’.

Regarding the first assumption, the various actors enmeshed in the EU’s MLG system are, in a sense, obliged to ‘build’ a strong coordinative discourse because it is only through systematic consultation and close collaboration that they can gradually adhere to EU practices and administrative procedures and, thus, increase the chances for EU policies to be successfully implemented. This, however, does not require the diffusion of and/or familiarisation with the EU norms and ideas that underlie these political goals. In that respect, given that policy actors at different government levels are only required to comply with cognitive policy ideas and other practical aspects pertaining to EU policies, it is likely that normative ideas are being crowded out of the coordinative discourse.

Regarding the second assumption, the way supranational policies are portrayed and communicated by EU and national/subnational political elites might have an impact upon their capacity to foster European identity. Communication, in terms of cognitive mobilisation (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1970) and psychological persuasion and symbolism (Bruter Reference Bruter2003; Laffan Reference Laffan, Hermann, Risse and Brewer2004), has already been framed as a key determinant of European identity. Yet, the disentanglement between the level at which policies and policy ideas originate (EU) and the level at which they are implemented and then communicated (national or subnational) might have serious implications for the final message conveyed to the general public. Besides the fact that communication largely depends on the will and priorities of domestic political elites to portray any given policy in a positive or a negative manner, the communicative discourse in any political system also encompasses other actors – influential in terms of attitude formation – such as members of opposition parties, the media, and expert groups (Bruter Reference Bruter2005; Copeland and Copsey Reference Copeland and Copsey2017). Adding to that, cultural and educational policies are controlled by national institutions, thus making it impossible for EU institutions to use them as channels to promote political messages (Shore Reference Shore2000; Gillespie and Laffan Reference Gillespie, Laffan, Cini and Bourne2006). These features make the task of controlling the final product of communication difficult (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008), while EU communication strategies have been widely criticised as being poor in terms of scope and resources and overly complex and out of reach for the general public (Mendez and Bachtler Reference Mendez and Bachtler2017). Last but not least, even if normative ideas about political goals manage to enter the communication agenda, the extent to which they are going to gain acceptance among the general public is largely determined by national/regional traditions and collective values (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1996).

Case selection and methodology

The article focuses on the coordinative and communicative discourse about Cohesion Policy to examine whether the latter has contributed to European identity-building. The presence or absence of a shared European identity among policy elites is verified by means of the inclusion (or non-inclusion) in their discourse of notions such as ‘redistribution’, ‘unity’, ‘solidarity’, and ‘Europeanism’ or the direct association of the policy with European identity. The citizens’ perspective is examined only indirectly, that is, through the communicative discourse and the mediation of political elites and the media. Cohesion Policy is approached as a most likely case of EU policies that pursue political – alongside economic – goals and which are governed by the MLG model of policy formation and implementation. The impact of the policy on European identity-building is explored through the comparative analysis method.

As qualitative methods are better suited to capturing the cognitive dimension of institutional impact, empirical findings are supported by 64 semistructured interviews with policy elite actors representing all three government levels involved in Cohesion Policy practice. The empirical research for the article covers the period 2000 – 20, thus covering three Multi-annual Financial Frameworks (2000 – 6, 2007 – 13, and 2014 – 20). The interviews were analysed using the coding method. The coding process initially resulted in the distinction between two overarching themes: practical aspects relating to the policy, such as difficulties and constraints encountered during the formation, implementation, and communication policy stages, and more ideational aspects, such as the political message embedded in it and whether it had been communicated and embraced in each context. In the second instance, the definition of additional coding categories informed a number of supporting themes. This enabled a distinction between different intervening variables that could help explain why Cohesion Policy had not contributed to European identity-building in each case.

With regard to case selection, the UK, Greece, and Poland were identified as suitable country cases on the basis of the following selection criteria: (i) representation of old net contributor member states (UK), old net recipient member states (Greece), and new net recipient member states (Poland); (ii) representation of unevenly developed regions within each country as defined by the triple division of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 2 regional classification;Footnote 2 and (iii) differentiated models of territorial governance.Footnote 3 One region from each country was then selected. The selection rationale involved the comparability of regions in terms of GDP/head and the existence of clearly articulated regional identities, as this could possibly affect discursive and socialisation processes relating to European identity-building. As such, the NUTS 2 regions of West Wales and the Valleys (UK), Crete (Greece), and Silesia (Poland) emerged as the most suitable cases.Footnote 4 Despite having significant differences, the three cases turned out to have several unexpected commonalities.

EU socialisation and discourse in the field of Cohesion Policy

Coordinative discourse about Cohesion Policy

All three regions seem to have built a good policy implementation record over time, a thesis also supported by DG REGIO desk officers responsible for monitoring the management of the Structural Funds in each (Interview 21; Interview 40; Interview 60). This suggests that EU requirements regarding the implementation of Cohesion Policy have generated convergence pressures across member states forcing national and regional policymakers to abide by EU practices and administrative procedures. Yet, the fact that successful policy transposition has not required their compliance with normative policy ideas has resulted in the coordinative discourse being dominated by cognitive policy ideas and practical aspects regarding the practice of the policy.

This was reflected most prominently in the case of Greece, where the dominant discourse between policy practitioners, stakeholders, and analysts has long revolved around a series of domestic policy practices and how they have jeopardised the effectiveness of EU funding. The debate on the questionable efficiency of the Structural Funds became more pronounced in the postcrisis period as the coordinative discourse involved reflections on the country’s past mistakes with regard to the employment of EU funds and even criticism that the EU had not provided sufficient safety nets to cushion the impact of the crisis, through Cohesion Policy among other channels (Interview 50). The effectiveness of the Structural Funds was also contested in the UK, albeit not by Welsh policymakers and practitioners but rather by representatives of the UK government, members of the opposition (Welsh Conservatives), and the English media and press. Despite Welsh policy elites’ positive view of the policy, however, the coordinative discourse developed between them and supranational-level actors has only involved facts, figures, and practical aspects regarding the day-to-day management of the Structural Funds, thus failing to touch upon the intellectual underpinning of the policy. A possible explanation, as put by two policy officers at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy of the UK government, is that ‘the very meaning and message of ‘cohesion’ has never been received and accepted in the UK and by extension Wales’ (Interview 34; Interview 35). In the case of Poland, although nobody questioned the positive impact of EU funding, the complex administrative procedures and very scope of EU-funded programmes have arguably discouraged domestic policy elites from ‘prioritising how to sell the policy’ (Interview 13).

Despite these variations, only a few informants brought the attention to notions such as ‘redistribution’, ‘unity’, ‘solidarity’, and ‘Europeanism’ (Interview 10; Interview 12; Interview 19) or, explicitly, associated Cohesion Policy with the creation of a shared European identity (Interview 4; Interview 11). This suggests that in none of the three cases has the coordinative discourse about Cohesion Policy involved normative ideas about political goals. Two key reasons seem to have frustrated the process of EU socialisation and, in turn, of European identity-building among national- and subnational-level actors. Firstly, Commission policy elites have focused on ensuring the legal certainty and sound administration of the Structural Funds and have not dedicated the same, or even some, effort to disseminate the political message embedded in the policy (Panagiotatou Reference Panagiotatou2020). As put by a senior policy officer at the Polish Ministry of Development ‘Cohesion Policy is very important at the level of ideas… unfortunately, implementation issues, deadlines, financial indicators, regularity of expenditure… it is very difficult to concentrate on the strategic issues in the area of cohesion if you have to organise calls for proposals, carry out public procurement, and you have all these procedures around you… the target actually disappears with all these issues… so the idea was good but the practice brought mixed effects’ (Interview 8).

Secondly, the ambiguity of Cohesion Policy in terms of pursued goals has undermined the political message embedded in it (Panagiotatou Reference Panagiotatou2020). Policymakers in all three countries/regions raised the ‘incompatibility’ between the convergence/cohesion and competitiveness objectives, highlighting that it was unclear which of the two messages the Commission wanted to bring forward (Interview 8; Interview 22; Interview 52). In fact, successive policy reforms and ensuing shifts in the scope and objectives of the policy have resulted in the policy lacking consistent goals. This has also been acknowledged by some Commission officials, one of whom compared the policy to a ‘Swiss army knife’ to denote how its scope had become too broad and all-encompassing over time (Interview 63). Adding to that, the gradual turn towards productivity- and competitiveness-related targets has resulted, in all three cases, in the political dimension of the policy being completely swallowed up by the economic one.

Communicative discourse about Cohesion Policy

The EU regulation governing the administration and management of the Structural Funds explicitly states that the responsibility for communicating about Cohesion Policy lies with member states’ authorities. Commission desk officers sustained that the managing authorities in Wales, Crete, and Silesia had been compliant overall with Commission communication requirements by physically displaying publicity material when a project was co-funded by the EU (Interview 21; Interview 40; Interview 60). Yet, regulatory communication, which focuses on policy inputs and outcomes and does not involve policy principles and political goals, differs significantly from other communication channels. In that regard, it is not surprising that the message registered with the general public with regard to Cohesion Policy and/or EU funding depended by and large on how the policy in question and the EU more broadly have been portrayed by domestic political elites and the media environment.

In the case of Wales, although successive Labour-led governments used to portray EU membership and Structural Funds as beneficial for the country (Interview 25; Interview 32; Interview 37), the eurosceptic rhetoric of Welsh Conservatives and of the English media seem to have affected the perceptions of the Welsh electorate about EU funding. In fact, the Welsh vote in the EU referendum revealed that some people believed that their surroundings had not changed over time and that EU funding had not benefited them significantly (Interview 24).

In contrast to Wales, Cohesion Policy has traditionally been portrayed in a positive light in Greece (Interview 50; Interview 55). Besides the fact that the country has been one of the main beneficiaries of the Structural Funds since the early 1980s, the pro-integration narratives of successive Greek governments and the concentration of EU funding on easily perceivable hard infrastructure projects have increased the visibility of the policy. Therefore, although Greece’s Europhile affiliation was challenged to its core in the aftermath of the socio-economic crisis, the communicative discourse about Cohesion Policy continued to highlight the country’s appreciation for and dependency on the policy.

Similar to Greece, public support for Cohesion Policy has been high in Poland (Interview 4; Interview 8; Interview 17). The willingness of the Polish governments in office until the early 2010s to extol the benefits of EU membership have played an important role in that regard. The change in the domestic political scenery, culminating in the election in 2015 – and reelection in 2019 – of the populist right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party, has, however, revealed a shallowness to Polish Euroenthusiasm. Although the PiS government differentiated its position towards Cohesion Policy from that of other EU policies (Interview 13), the shift in the communicative discourse about EU membership and how it has entailed benefits and costs has resulted in Cohesion Policy losing something of the high regard it held in recent years.

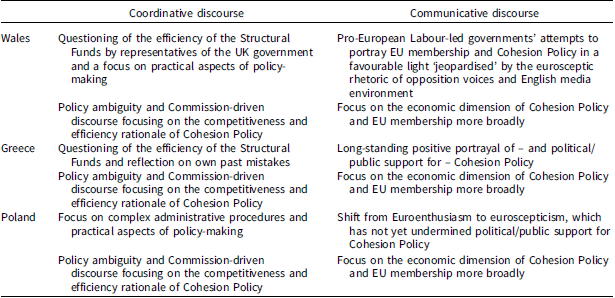

Despite these variations, the communicative discourse about Cohesion Policy has in all three cases focused on the economic dimension of the policy. The main – and common – reason was that the EU more broadly had mainly been portrayed and perceived in economic terms. With domestic political elites and the media having long concentrated on the economic pros and cons of EU membership and EU policies, Europe has largely been imprinted as another way of redistributing public money (Interview 18) or a free source of funding (Interview 42; Interview 58) rather than an integrated political space with shared norms and values. This suggests that the limited role of Cohesion Policy in fostering a European identity is owed to the way it has been portrayed by domestic political elites and/or the media and, more so, to the broader national and/or regional political cultures and perceptions about the purpose and limitations of EU membership. Besides the fact that in all three cases national and regional identities proved to be more powerful than the European identity, the analysis has shown that the limited effort made by supranational policy elites to promote Cohesion Policy as something more than merely an economic tool has further minimised the chances of it contributing to the achievement of EU political goals. Table 1 presents determinants of discourse regarding Cohesion Policy.

Table 1. Determinants of discourse about Cohesion Policy

As with the majority of studies, the empirical results reported herein should be considered in light of some limitations. The first is the difficulty in detecting when a change of attitudes is produced through socialisation, which, similar to other somewhat ideational processes, is hard to measure and operationalise. The added value of this study yet suggests that the socialisation framework provides key insights into the policy process, even though finding specific instances thereof remains challenging. The second concerns the chosen methods, as the research findings are largely based on self-reported data. Nonetheless, the constraining of potential sources of bias, such as selective memory, telescoping, and exaggeration, was attempted through the combined analysis of informants’ insights with relevant academic literature and press articles; where this was not possible, an effort was made for insights provided by individual informants not to lead to generalised statements. Lastly, the study did not involve citizens’ surveys, focus groups, or other methods that could shed light on public perceptions and attitudes. Besides the fact that such evidence exists in abundance and largely confirms that Cohesion Policy has not had a direct effect on the Europeanisation of populations, the objective of this study consisted in framing Cohesion Policy-induced European identity-building mainly among policy elites and, indirectly, among the public.

Conclusions

So far, the literature on European identity politics has not engaged much with identity formation at the level of policy elites. This paper employed Cohesion Policy as a most likely case through which to explore EU socialisation via discursive practices, with the potential of leading to European identity-building, among policy elites at different government levels and, indirectly, among the public. The analysis showed that, despite major differences between EU countries and regions, results do not differ much. In an MLG system, normative ideas about political goals, consolidated at the supranational level, are difficult to communicate to domestic policy elites, and it is hard for them to gain acceptance because coordinative discourses about EU policies are dominated by notions of economic and material benefit as well as practical aspects of policy-making. In the case of Cohesion Policy, the fact that Commission-driven discourse has focused on the competitiveness and efficiency rationale of the policy has also played its part. On a similar note, normative ideas about political goals are difficult to communicate to the general public, and it is hard for them to gain acceptance because communicative discourses are controlled by domestic political elites and the media and are ultimately determined by the broader national/regional political cultures and perceptions about the purpose and limitations of EU membership.

This paper contributes to the currently relevant European identity theoretical agenda by arguing that the MLG policy model and the way EU public policies are designed, implemented, and communicated do not favour the achievement of political goals, such as the cultivation of a shared European identity. It also complements existing research on Cohesion Policy-induced European identity-building, which is mainly concerned with the citizens’ perspective, by offering insights into the elites’ perspective and echoing accounts suggesting a limited impact of the former on the latter and accounts bringing to the fore communication deficits and failed EU communication strategies. Lastly, it contributes to the EU socialisation and discourse literatures by providing evidence of socialisation and discourse dynamics in policy areas. Further research could focus on other policy areas and test the comparability of findings or investigate the interplay between European and regional identity in the light of Cohesion Policy practice.

Finally, the paper offers practical insights for policy elites. As enhancing European identity seems more important than ever, European elites have the capacity – if not an informal mission – to try to diffuse and gain support for normative ideas about political goals among national and subnational-level actors. Otherwise, this task will be restricted to academic and political circles.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1682098325100131.

Data availability statement

Available upon request.