1. Introduction

Open clusters (OCs) are densely bound collections of stars, born out of the collapse of large clouds of gas. They can range in age from a few tens of Myr to a few Gyr and are single stellar populations (SSPs Portegies Zwart, McMillan, & Gieles Reference Portegies Zwart, McMillan and Gieles2010; Cantat-Gaudin & Casamiquela Reference Cantat-Gaudin and Casamiquela2024). Due to this, they are useful as tracers of Galactic chemical trends (Donor et al. Reference Donor2020), as well as understanding simple stellar evolution in a dynamical environment (Hurley et al. Reference Hurley, Pols, Aarseth and Tout2005; Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2024). Because of their distribution in the Milky Way and proximity to Earth, their individual stars can be resolved and well studied.

Data from ESA’s Gaia satellite (Gaia Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2016) has completely revolutionised the census of OCs in just a few short years (Cantat-Gaudin & Casamiquela Reference Cantat-Gaudin and Casamiquela2024). Since the release of Gaia DR2 (GaiaCollaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2018), thousands of new OCs have been discovered (e.g. Castro-Ginard et al. Reference Castro-Ginard2018; Liu & Pang Reference Liu and Pang2019; Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2023), over a thousand OCs from before Gaia have been ruled out as asterisms (Cantat-Gaudin et al. Reference Cantat-Gaudin2020; Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2023), and the general quality of the OC census has improved, both in terms of improved membership determination (Cantat-Gaudin et al. Reference Cantat-Gaudin2018; Dias et al. Reference Dias2021; Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2023; Perren et al.Reference Perren, Pera, Navone and Vázquez2023) and improved determination of parameters such as cluster distance, age, and mass (Cantat-Gaudin et al. Reference Cantat-Gaudin2020; Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2023; Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo2024). There has hence never been a better time to do science with OCs in the Milky Way.

With the available wealth of X-ray and radio surveys, it is now possible to delve into the contents of OCs by searching for their multiwavelength counterparts. For example, Belloni, Verbunt, & Mathieu (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998), van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004) and Mooley & Singh (Reference Mooley and Singh2015) used X-ray observations from Chandra and XMM-Newton to identify X-ray counterparts to individual cluster members of the old OC M67. Radio emission is also helpful to classify X-ray sources (e.g. Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2024; Paduano et al. Reference Paduano2024, among others)

Two major sources of uncertainty for these kinds of studies are (1) determining whether a given X-ray point source has an optical counterpart (which is dependent on positional accuracy), and (2) whether that optical counterpart is a cluster member. While the association of multiwavelength sources to OC members is challenging, it is useful to find unique sources to benchmark SSP evolution in a dense field.

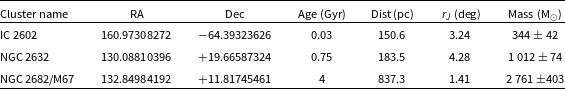

Table 1. Observed cluster properties from Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024), except for the age of M67, as the ages are underestimated for clusters with blue straggler stars (Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2024; Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo2024). M67 is estimated to be around 4 Gyr old (Reyes et al. Reference Reyes2024, and references therein).

In old OCs (older than a few Gyr), most single stars have spun down due to magnetic braking and are consequently faint in X-ray (e.g. Caillault Reference Caillault, Pallavicini and Dupree1996). In clusters around this age, bright X-ray sources are instead dominated by binaries. In binaries with relatively short separations (or relatively large radii), tidal interactions can force the stars into a higher rotation rate, leading to higher X-ray emission (e.g. Belloni et al. Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998). In other cases, accretion onto compact objects within a binary also produces luminous X-ray sources. Multiwavelength observations, particularly in the X-ray, allow us to probe the populations of these close binary systems. Since binary populations are drivers of cluster evolution (Hut et al. Reference Hut1992), this in turn gives us greater understanding of the dynamical evolution of clusters.

Beyond the influence that dynamics provide to enhance BH formation in clusters, from the observational standpoint, it is natural to associate the origins of many black holes with star clusters, including new evidence in the form of Gaia BH3 (Gaia Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2024), which is found in the stellar stream of ED-2, a disrupted low mass cluster (Balbinot et al. Reference Balbinot2024). In this paper, we use archival and survey observations from X-ray and radio facilities to search for multiwavelength counterparts to individual OC stars, as identified by Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024). We specifically target nearby OCs from three different ages and compare their unique multiwavelength contents, with the aim to use this information to provide a benchmark for the contents of OCs of different ages and masses to improve future iterations of N-body simulations of OCs.

2. Data and analysis

For our cluster sample, we use individual cluster members as identified in data from Gaia DR3 (Gaia Collaboration et al.Reference Collaboration2023) by Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024). We search for X-ray counterparts from Chandra (Weisskopf et al. Reference Weisskopf2002), XMM-Newton (Jansen et al. Reference Jansen2001), eROSITA (Merloni et al. Reference Merloni2024), as well as radio counterparts from the Evolutionary Map of the Universe (EMU) survey (Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins2025) and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (Perley et al. Reference Perley, Chandler, Butler and Wrobel2011). We also take advantage of the Gaia variability flags to further classify sources, and we search for evidence of optical variability and further classification thanks to work by Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023).

2.1. Cluster sample

The cluster sample is selected as follows; we targeted nearby OCs (within 1 kpc) observed in X-ray, targeting three different age ranges; a young OC, IC 2602 (30 Myr), a middle age OC, NGC 2632 (350 Myr), and an old cluster, NGC 2682/M67 (4 Gyr). IC 2602 and NGC 2632 are both within the publicly released German eROSITA footprint, and M67 has been well studied in X-ray with ROSAT, Chandra, and XMM-Newton (Belloni et al. Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998; van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004; Mooley & Singh Reference Mooley and Singh2015). M67 is one of the most well studied OCs in almost every wavelength (except radio), with optical studies to determine stellar cluster membership and ultraviolet studies to find evidence of a blue straggler population (Peterson, Carney, & Latham Reference Peterson, Carney and Latham1984).

Blue stragglers are bluer and brighter than the main sequence turnoff stars (Sandage Reference Sandage1953). Stellar merger, collision, and mass-transfer are known to be the primary channels for their formation (Boffin, Carraro, & Beccari Reference Boffin, Carraro and Beccari2015). Due to the low density of OCs, stellar merger, and mass-transfer are the only viable channels. The formation of blue stragglers due to multiple stellar interactions places them among the massive populations in star clusters (Shara, Saffer, & Livio Reference Shara, Saffer and Livio1997), and therefore they are representatives of dynamical ages of their host clusters as well (Ferraro et al. Reference Ferraro2012; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Vaidya, Agarwal, Balan and Bhattacharya2023)

We revisit M67 in light of new Gaia memberships. For our multi-wavelength study of M67, we can take advantage of Geller, Latham, & Mathieu (Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015)’s spectroscopic study of M67 members to search for radial velocity variability. We report the cluster properties in Table 1.

2.2. X-ray

Due to their extended size (often spanning several degrees), nearby OCs are often not the target of detailed X-ray studies (with the exception of M67, which has been well studied at the center), but benefit from sensitive all-sky X-ray surveys like eROSITA, which can provide a consistent picture of the entire cluster. For IC 2602 and NGC 2632, we searched for X-ray counterparts to individual cluster members in eROSITA. We rejected three matches in IC 2602 because the optical magnitude was brighter than 6, and the X-rays were likely due to optical loading (for further discussion, see Merloni et al. Reference Merloni2024; Saeedi et al. Reference Saeedi2022).

M67 is nominally in the publicly available eROSITA footprint. However, we did not identify any X-ray counterparts from eROSITA. We therefore made use of archival pointed observations from Chandra and XMM-Newton. For Chandra, we used the Chandra Source Catalog version 2.1 (Evans et al. Reference Evans2010), which contains two relevant observations: ObsID 1873 (50 ks, 2001 May 31, PI: Belloni) and ObsID 17020 (10 ks, 2015 February 26, PI: van den Berg). For XMM-Newton, we examined the European Photon Imaging Camera (EPIC) Pipeline Processed Source (PPS) catalogues for ObsID 0212080601 (15 ks, 2005 May 8, PI: Jansen) and ObsID 0109461001 (10 ks, 2001 October 20, PI: Mason).

We were particularly interested in follow up on a specific X-ray source in M67, WOCS 3012/S1077. We extracted it from the merged Chandra dataset and estimated its unabsorbed fluxes using the srcflux script in CIAO. A power-law spectral model with a fixed photon index of

![]() $\Gamma = 2$

was adopted, and the hydrogen column density was fixed at

$\Gamma = 2$

was adopted, and the hydrogen column density was fixed at

![]() $N_H = 2.2\times10^{20}$

cm

$N_H = 2.2\times10^{20}$

cm

![]() $^{-2}$

(van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004).

$^{-2}$

(van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004).

For ObsID 1873 (effective exposure 46.26 ks), the unabsorbed flux in the 0.5–8.0 keV band was

![]() $7.8^{+0.49}_{-0.49}\times10^{-14}$

erg cm

$7.8^{+0.49}_{-0.49}\times10^{-14}$

erg cm

![]() $^{-2}$

s

$^{-2}$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

. For the same model, the fluxes in the 1–10 and 0.5–10 keV bands were

$^{-1}$

. For the same model, the fluxes in the 1–10 and 0.5–10 keV bands were

![]() $4.75^{+0.40}_{-0.40}\times10^{-14}$

and

$4.75^{+0.40}_{-0.40}\times10^{-14}$

and

![]() $7.87^{+0.50}_{-0.49}\times10^{-14}$

erg cm

$7.87^{+0.50}_{-0.49}\times10^{-14}$

erg cm

![]() $^{-2}$

s

$^{-2}$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

, respectively. Assuming a distance of 820 pc to M67 (van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004), this flux corresponds to an X-ray luminosity of

$^{-1}$

, respectively. Assuming a distance of 820 pc to M67 (van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004), this flux corresponds to an X-ray luminosity of

![]() $L_X\approx6.3 \times 10^{30}$

erg s

$L_X\approx6.3 \times 10^{30}$

erg s

![]() $^{-1}$

in the energy band of 0.5–8.0 keV.

$^{-1}$

in the energy band of 0.5–8.0 keV.

In contrast, no significant X-ray emission was detected at the same coordinates in ObsID 17020 (effective exposure 9.82 ks). Using the Bayesian prescription for Poisson statistics in the case of zero source counts (Kraft, Burrows, & Nousek Reference Kraft, Burrows and Nousek1991), we derived a 90% confidence count-rate upper limit of

![]() $2.34 \times {10^{ - 4}} {\rm{counts }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

. Assuming the same spectral model as above (

$2.34 \times {10^{ - 4}} {\rm{counts }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

. Assuming the same spectral model as above (

![]() $\Gamma = 2$

,

$\Gamma = 2$

,

![]() ${N_H} = 2.2 \times {10^{20}} {\rm{c}}{{\rm{m}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}$

), the corresponding unabsorbed flux upper limits are

${N_H} = 2.2 \times {10^{20}} {\rm{c}}{{\rm{m}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}$

), the corresponding unabsorbed flux upper limits are

![]() $9.4 \times {10^{ - 16}} {\rm{erg }} \, {{\rm{cm}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}{\rm{ }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

(0.5–10 keV) and

$9.4 \times {10^{ - 16}} {\rm{erg }} \, {{\rm{cm}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}{\rm{ }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

(0.5–10 keV) and

![]() $8.2 \times {10^{ - 16}} {\rm{erg}} \, {{\rm{cm}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}{\rm{ }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

(1–10 keV), which translate to luminosity limits of

$8.2 \times {10^{ - 16}} {\rm{erg}} \, {{\rm{cm}}^{ - {\rm{2}}}}{\rm{ }}{{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

(1–10 keV), which translate to luminosity limits of

![]() ${L_X} \lt 7.6 \times {10^{28}}$

and

${L_X} \lt 7.6 \times {10^{28}}$

and

![]() ${L_X} \lt 6.6 \times {10^{28}} {\rm{erg}} \, {{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

, respectively.

${L_X} \lt 6.6 \times {10^{28}} {\rm{erg}} \, {{\rm{s}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}}$

, respectively.

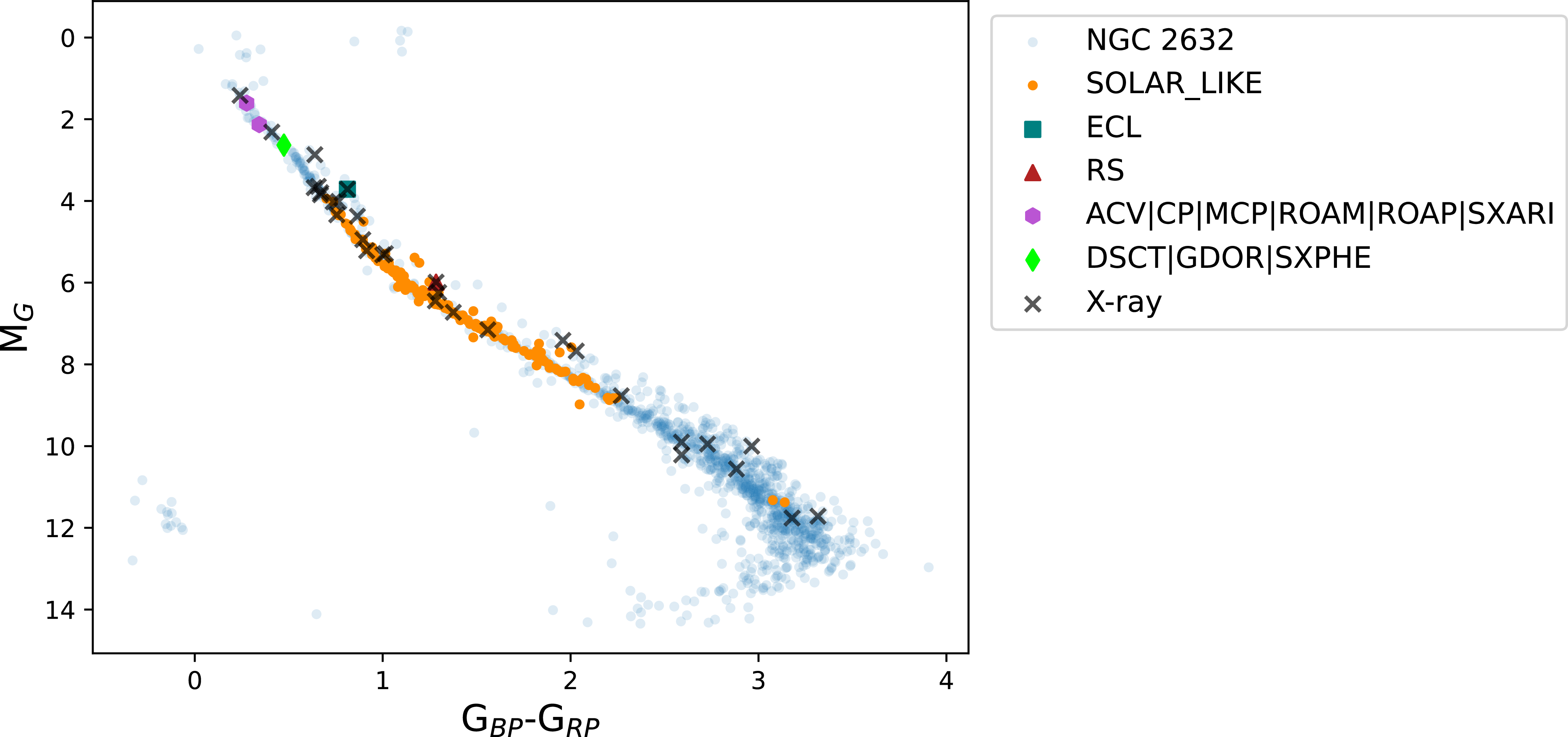

2.3. Radio

IC 2602 has been observed by the Australian SKA Pathfinder Telescope EMU survey (Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins2025). We searched for radio counterparts to X-ray point sources associated with cluster stars in the pipeline-processed catalogues. The EMU survey will mainly be sensitive to background AGN, but at the 150 pc distance of IC 2602, it is also sensitive to radio emission produced by chromospherically active contact binaries.

Of the 77 X-ray sources with high probability matches to cluster stars, only three had detected radio counterparts in EMU, all in the central region of IC 2602.

NGC 2632 and M67 are too far north to be observed by ASKAP. However, M67 has been observed by VLA on 2010 December 11 (Project code: VLA/10B-173) for four hours in total. The observations were taken with the C-band receiver (centred at 5 GHz) with a 2 GHz total bandwidth. 3C286 (J1331+3030) was observed and used for bandpass and flux scale calibration and J0842+1835 for gain calibration. The data were calibrated and imaged with CASA (CASA Team et al. Reference Team2022). The VLA Pipeline 2024.1.1 (CASA 6.6.1)Footnote a was used to perform flagging and calibration. Briggs weighting with robustness parameter 0 was used to image the data.

We used pyBDSF (Mohan & Rafferty 2015), to detect radio point sources down to a

![]() $\sim 5 \sigma$

threshold, and detected 50 unique point sources. We crossmatched VLA and Gaia data for potential matches within

$\sim 5 \sigma$

threshold, and detected 50 unique point sources. We crossmatched VLA and Gaia data for potential matches within

![]() $1^{\prime\prime}$

and found four radio sources with a Gaia counterpart. Only one of these sources has cluster membership in M67 (604921855602675968, with a flux density of 96

$1^{\prime\prime}$

and found four radio sources with a Gaia counterpart. Only one of these sources has cluster membership in M67 (604921855602675968, with a flux density of 96

![]() $\pm 5\,\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy). One is classified as a background AGN SDSS J085150.31+114855.9 (Gaia DR3 604918380973692800). Two have stellar classifications, Gaia DR3 604918174820102400 is classified as rotating variable EY Cnc, Gaia DR3 604915808290404480 is classified as a cluster member by Fan et al. (Reference Fan1996), but the X-ray counterpart from van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004) is classified as a QSO, highlighting the prevalence of background AGN contamination in pre-Gaia cluster catalogues.

$\pm 5\,\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy). One is classified as a background AGN SDSS J085150.31+114855.9 (Gaia DR3 604918380973692800). Two have stellar classifications, Gaia DR3 604918174820102400 is classified as rotating variable EY Cnc, Gaia DR3 604915808290404480 is classified as a cluster member by Fan et al. (Reference Fan1996), but the X-ray counterpart from van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004) is classified as a QSO, highlighting the prevalence of background AGN contamination in pre-Gaia cluster catalogues.

2.4. Crossmatching with nway

We use nway Footnote b (Salvato et al. Reference Salvato2018) to crossmatch between crossmatch between X-ray data from eROSITA and Chandra and Gaia fields of IC 2602 and NGC 2632 (querying the full Gaia catalogue from the position and Jacobi radius given in Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2024).

nway computes the match probability, useful in the case of multiple potential matches, and rules out sources with a high probability of chance superposition. Because these OCs are not very crowded fields, we did not find any issues with crowding or multiple optical counterparts to an X-ray counterpart. nway’s match probability for all matches was very high (

![]() $\gt$

95% in all cases).

$\gt$

95% in all cases).

We crossmatched up to a radius of

![]() $5^{\prime\prime}$

for the following reasons: while the positional errors of eROSITA sources typically ranged from

$5^{\prime\prime}$

for the following reasons: while the positional errors of eROSITA sources typically ranged from

![]() $1^{\prime\prime}$

up to

$1^{\prime\prime}$

up to

![]() $15^{\prime\prime}$

, we do not report matches with separations larger than

$15^{\prime\prime}$

, we do not report matches with separations larger than

![]() $5^{\prime\prime}$

. We shifted the RA and Dec of one catalogue in several directions by

$5^{\prime\prime}$

. We shifted the RA and Dec of one catalogue in several directions by

![]() $10^{\prime\prime}$

and, after rematching, found that the shifted catalogues gave a large number of matches beyond

$10^{\prime\prime}$

and, after rematching, found that the shifted catalogues gave a large number of matches beyond

![]() $5^{\prime\prime}$

, suggesting that matches with a separation higher than

$5^{\prime\prime}$

, suggesting that matches with a separation higher than

![]() $5^{\prime\prime}$

were contaminated.

$5^{\prime\prime}$

were contaminated.

For M67, thanks to Chandra’s subarcsecond spatial resolution, we considered matches between Gaia and the CSC up to

![]() $1^{\prime\prime}$

. We only found two XMM-Newton matches to M67 stellar members that were not also detected by Chandra. We note that we expect to have different results to Belloni et al. (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998), van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004), and Mooley & Singh (Reference Mooley and Singh2015), as Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024)’s Gaia cluster catalogues are more accurate than those used in previous X-ray studies of M67.

$1^{\prime\prime}$

. We only found two XMM-Newton matches to M67 stellar members that were not also detected by Chandra. We note that we expect to have different results to Belloni et al. (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998), van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004), and Mooley & Singh (Reference Mooley and Singh2015), as Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024)’s Gaia cluster catalogues are more accurate than those used in previous X-ray studies of M67.

2.5. Optical variability

We searched for evidence of optical variability using the Gaia variability flags, and Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023) which crossmatches Gaia data to all known optical surveys. For each cluster, we search the optical counterpart to a given X-ray source in these databases, and we catalogue their classification and period if one exists in the literature. A preview of these tables can be seen in the Appendix.

Gaia classifications include solar-like variability, eclipsing binaries, RS Canum Venaticorum,

![]() $\alpha^2$

CVn and associated stars,

$\alpha^2$

CVn and associated stars,

![]() $\delta$

Scuti/

$\delta$

Scuti/

![]() $\gamma$

Doradus/SX Phoenicis, young stellar objects, RR Lyrae and slowly pulsating B stars. Thanks to longterm optical surveys such as Drake et al. (Reference Drake2014),Watson, Henden, & Price (Reference Watson, Henden and Price2006), Heinze et al. (Reference Heinze2018), Tian et al. (Reference Tian2020), Pourbaix et al. (Reference Pourbaix2004), Jayasinghe et al. (Reference Jayasinghe2019), Palaversa et al. (Reference Palaversa2013), Perryman et al. (Reference Perryman1997) in some cases, we are able to obtain optical periods for the systems. For the X-ray sources, we report variability class and period (if known) in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

$\gamma$

Doradus/SX Phoenicis, young stellar objects, RR Lyrae and slowly pulsating B stars. Thanks to longterm optical surveys such as Drake et al. (Reference Drake2014),Watson, Henden, & Price (Reference Watson, Henden and Price2006), Heinze et al. (Reference Heinze2018), Tian et al. (Reference Tian2020), Pourbaix et al. (Reference Pourbaix2004), Jayasinghe et al. (Reference Jayasinghe2019), Palaversa et al. (Reference Palaversa2013), Perryman et al. (Reference Perryman1997) in some cases, we are able to obtain optical periods for the systems. For the X-ray sources, we report variability class and period (if known) in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

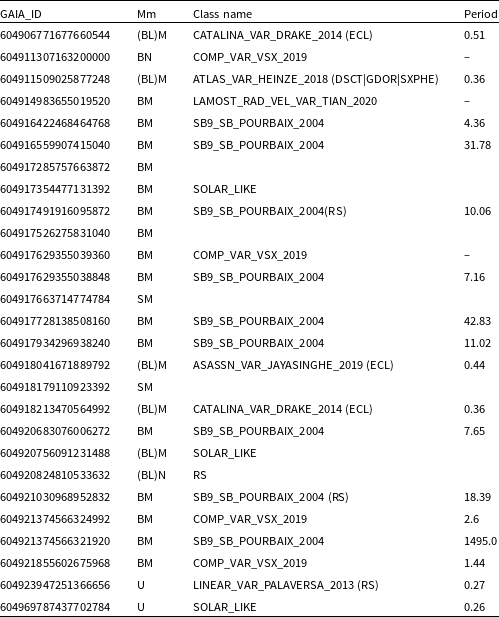

Of the 33 X-ray sources we found associated with a M67 individual star, 27 were found in the Geller et al. (Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015) spectroscopic study. Of these, 80% fall in the binary member category, or likely binary member category. Three are likely single members, and two are unknown (but still proper motion members). We report the Geller et al. (Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015) binary member category in Table 4, along with the variability classification from Gaia for M67.

3. Results and discussion

We used new and archival multiwavelength observations to search the contents of three OCs: IC 2602 (0.03 Gyr), NGC 2632 (0.35 Gyr), and M67 (4 Gyr).

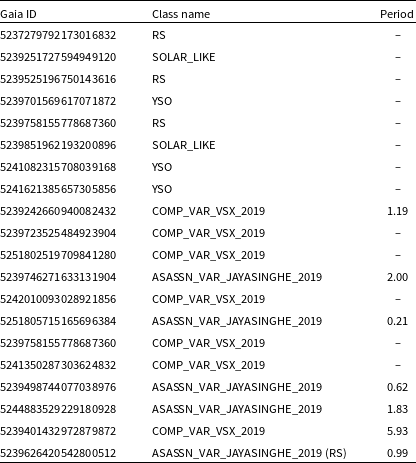

Table 2. Variability flags and optical periods for X-ray sources in IC 2602, where reported in Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023). Less than half of these X-ray sources have detected variability.

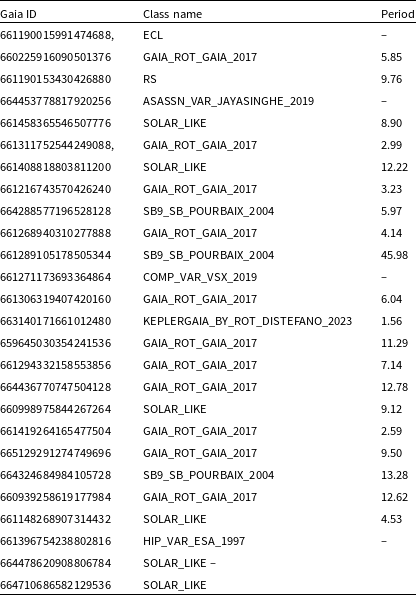

Table 3. Gaia variability flags and optical periods for X-ray sources in NGC 2632 (where available) from Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023). The majority of the X-ray sources in NGC 2632 are from rotational variables.

3.1. IC 2602

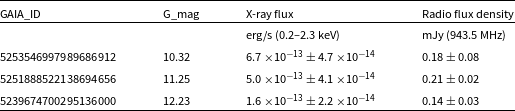

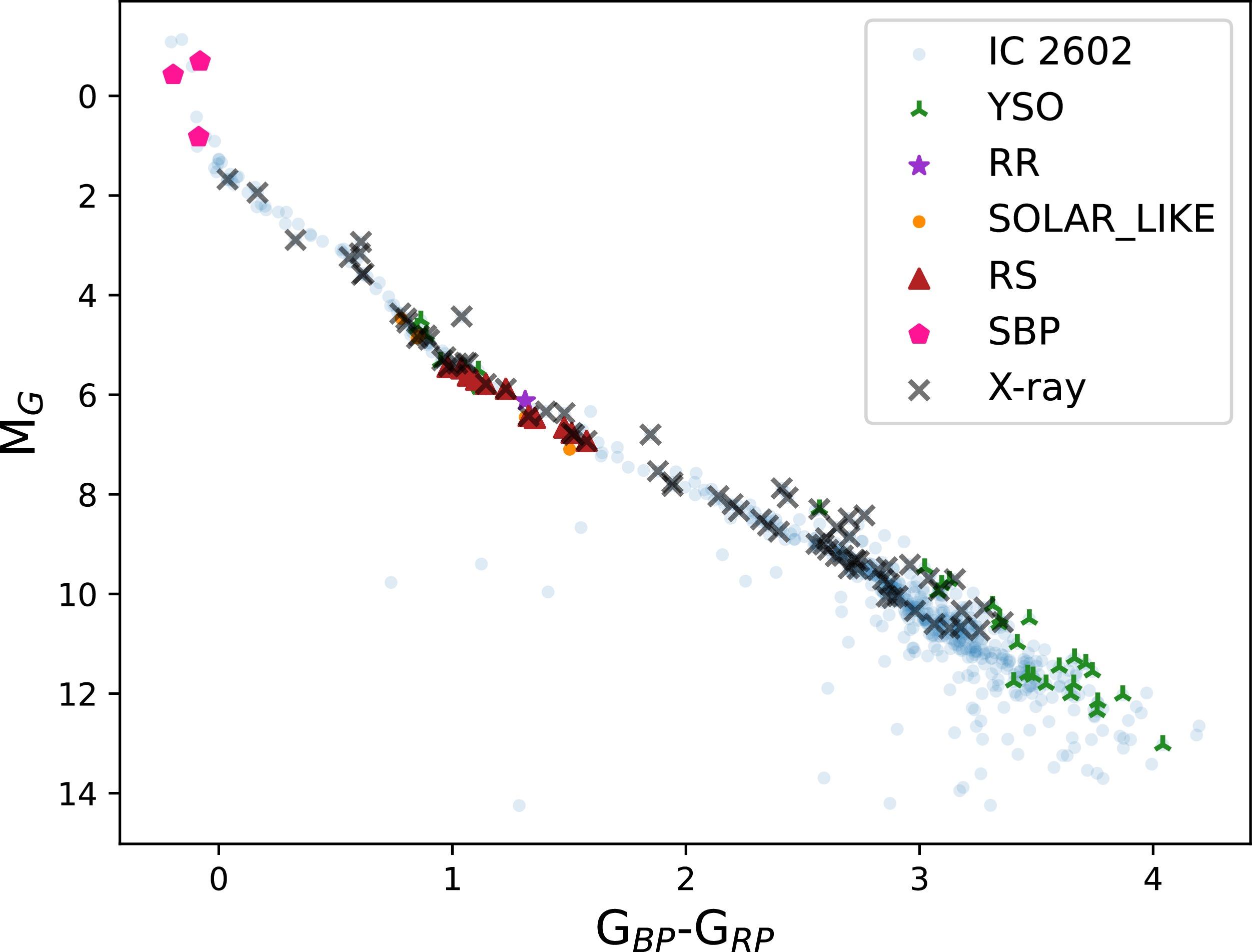

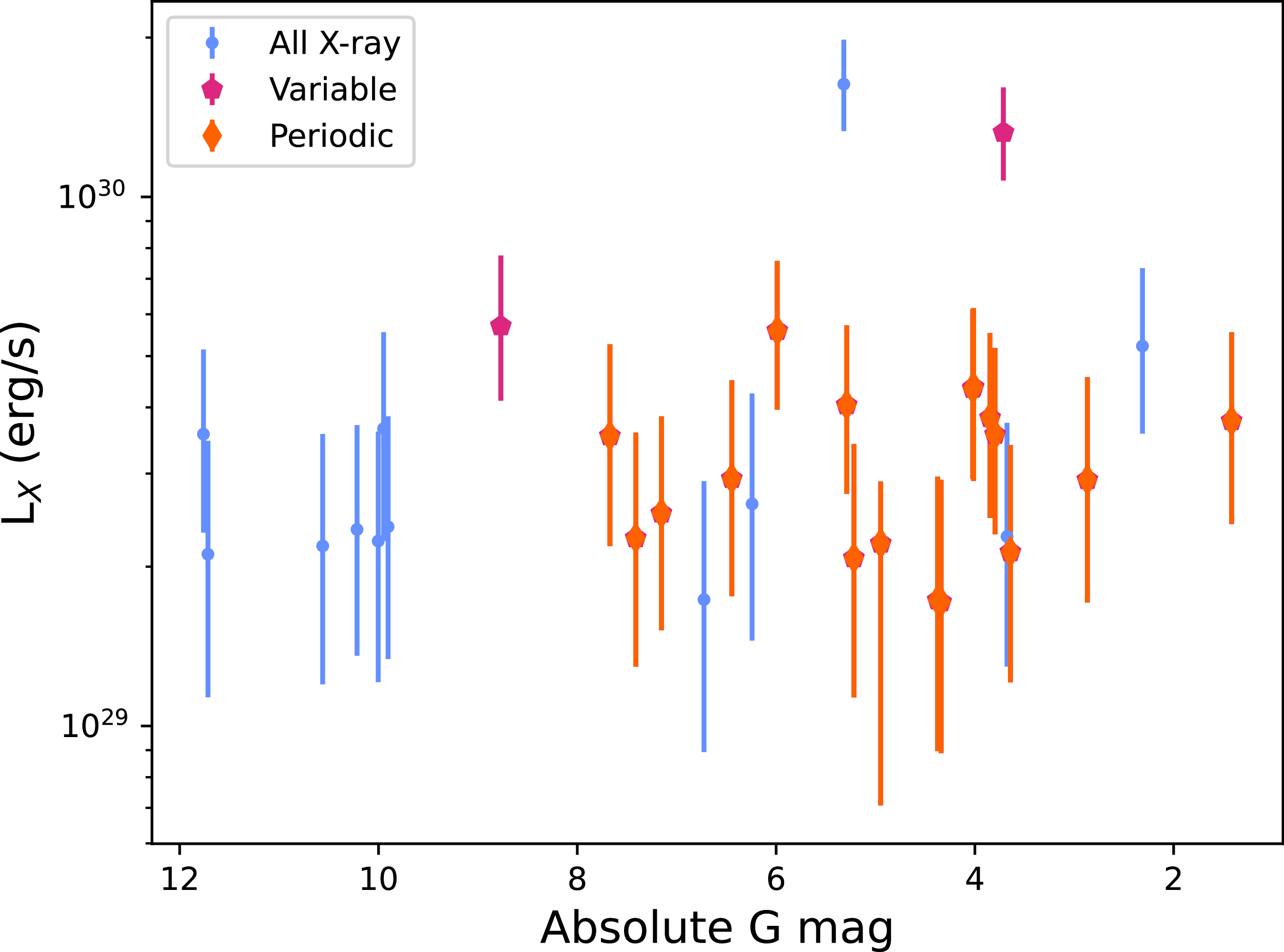

Of the 77 X-ray sources associated with IC 2602, only 14 had variability classification or measured periods. Three sources had radio from EMU associated with them, and the radio and X-ray fluxes suggest these systems are chromospherically active binary stars, consistent with Guedel, Schmitt, & Benz (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995), Driessen et al. (Reference Driessen2024) (see also Paduano et al. Reference Paduano2024). The radio and X-ray fluxes of these sources are summarised in Table 5. Other classification of the X-ray sources include young stellar objects, RS Canum Venaticorum, and solar-like sources. Several other of the X-ray sources are unclassified variable sources found in AAVSO and ASAS-SN. The location of these sources on the colour-magnitude diagram (CMD) can be seen in Figure 1, and the X-ray luminosity versus optical magnitude in Figure 2. The radio detections appear to be early to mid-F spectral type stars. Based on the CMD of IC 2602, these stars have masses between 1.2 and 1.5 solar masses, which indicates that they have begun to develop convective envelopes, signifying that their stellar structure is changing.

An upper main-sequence star with Gaia ID = 5239843200460432384 is identified as a very fast rotator and has also been classified as an SPB variable. This matched to a detection in eROSITA, which we rejected as contaminated as it fell into the optical loading range. If this source is indeed X-ray bright, the combination of SPB variability, rapid rotation, and strong X-ray emission would point towards either the presence of a companion or a Be/Bp spectral classification. Be stars are a subset of B-type stars that host decretion discs driven by their rapid rotation, and a fraction of them are known to exhibit SPB-type pulsations (Rivinius, Baade, & Carciofi Reference Rivinius, Baade and Carciofi2016; Shi et al. Reference Shi2023). Additionally, two other stars, Gaia IDs = 5299121205191777792 and 5239841340702856960, show high RUWE values, strongly suggesting the presence of gravitational companions. Notably, Gaia ID = 5299121205191777792 is even listed in SIMBAD as a double or multiple system.

Table 4. Variability flags and optical periods compiled by Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023) along with binary membership from Geller et al. (Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015) for M67 X-ray sources. (BL)M stands for likely binary member, BM for binary member, SM for single member, (BL)N for binary likely non-members, and U for unknown.

Table 5. IC 2602 cluster members with X-ray from eROSITA and radio from the EMU survey.

3.2. NGC 2632

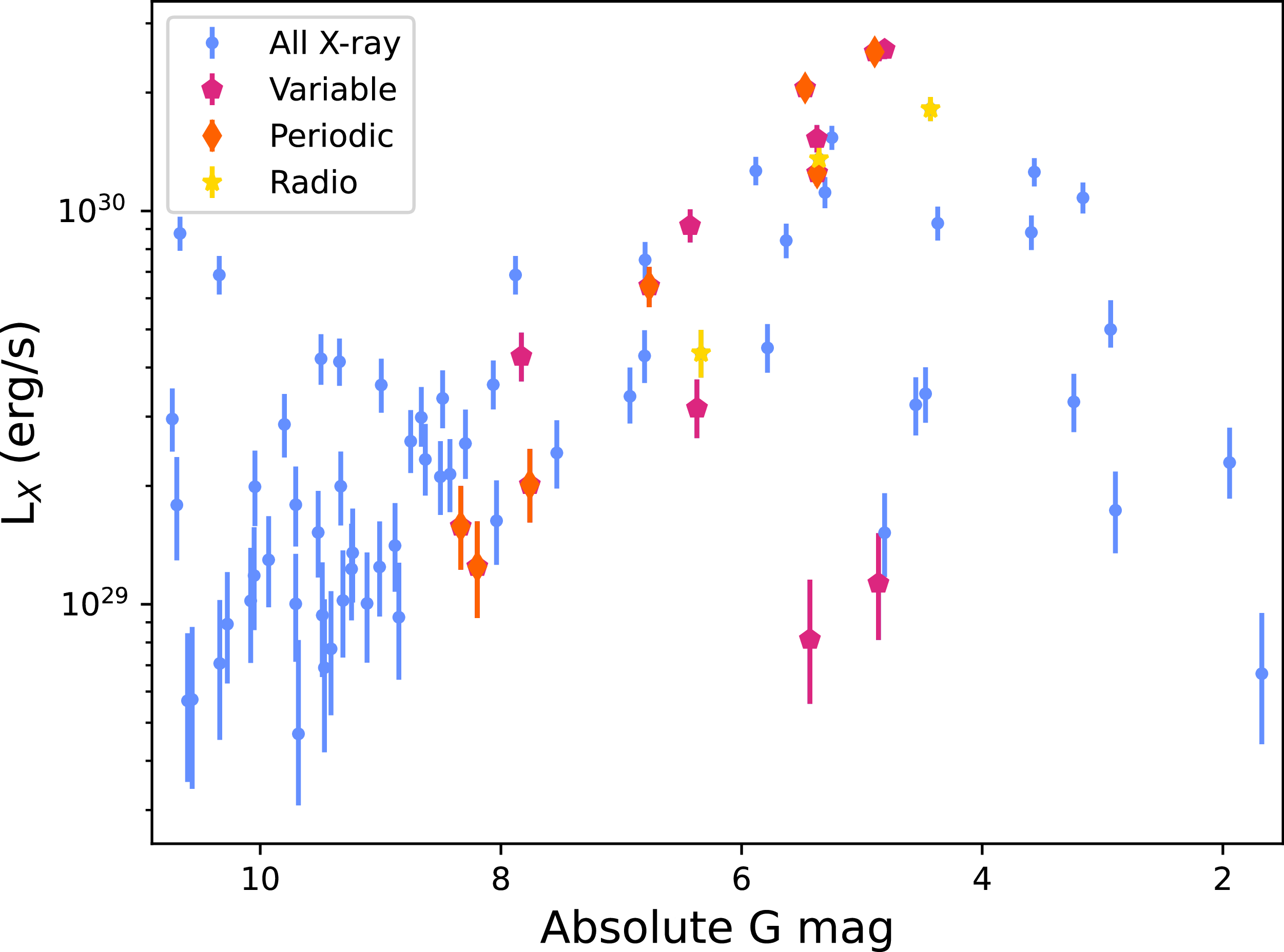

We identified 31 eROSITA sources which can be associated with NGC 2632 stellar members. Of these, 19 showed optical variability. The majority of the X-ray systems have solar-like variability, with one eclipsing binary, one RS Canum Venaticorum, rotational sources, and other variability (Pourbaix et al. Reference Pourbaix2004; Jayasinghe et al. Reference Jayasinghe2019; Perryman et al. Reference Perryman1997; Distefano et al. Reference Distefano2023). The location of the X-ray sources and optical variables on the CMD can be seen in Figure 3, and we plot the X-ray luminosity versus optical magnitude in Figure 4. We searched the VLASS all sky catalogue (Lacy et al. Reference Lacy2020), but there were no detected radio counterparts matching to eROSITA cluster associated X-ray sources within 10".

Figure 1. CMD for IC 2602. Black x’s are X-rays from eROSITA, green triangles are

![]() $\delta$

Scuti/

$\delta$

Scuti/

![]() $\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, purple pentagons are ACV systems, red triangles are RS Canum Venaticorum, teal squares are eclipsing binaries and orange points are solar-like variability.

$\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, purple pentagons are ACV systems, red triangles are RS Canum Venaticorum, teal squares are eclipsing binaries and orange points are solar-like variability.

One of the upper main-sequence X-ray sources in NGC 2632 (Gaia ID = 664314759317023360,

![]() $G = 8.632$

mag, corresponding to an absolute G mag of 2.31) has a

$G = 8.632$

mag, corresponding to an absolute G mag of 2.31) has a

![]() $v_{\text{broad}} = 195.29 \pm 2.43$

km s

$v_{\text{broad}} = 195.29 \pm 2.43$

km s

![]() $^{-1}$

and a high RUWE value of 5.12, suggesting the presence of a gravitationally bound companion. The observed X-ray emission may either arise from interaction processes within the system that is also driving rapid stellar rotation, or from a low-mass companion.

$^{-1}$

and a high RUWE value of 5.12, suggesting the presence of a gravitationally bound companion. The observed X-ray emission may either arise from interaction processes within the system that is also driving rapid stellar rotation, or from a low-mass companion.

3.3. M67

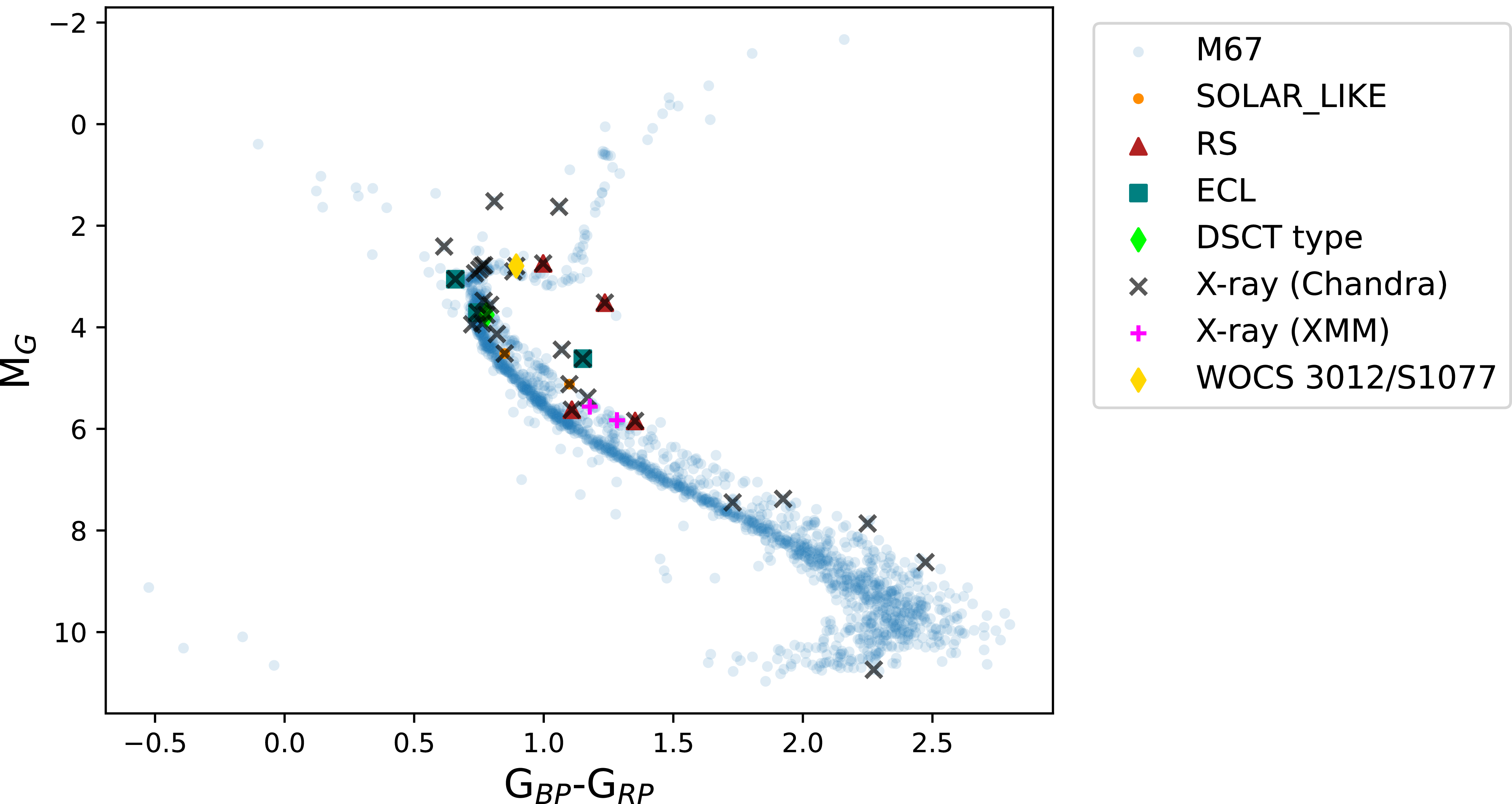

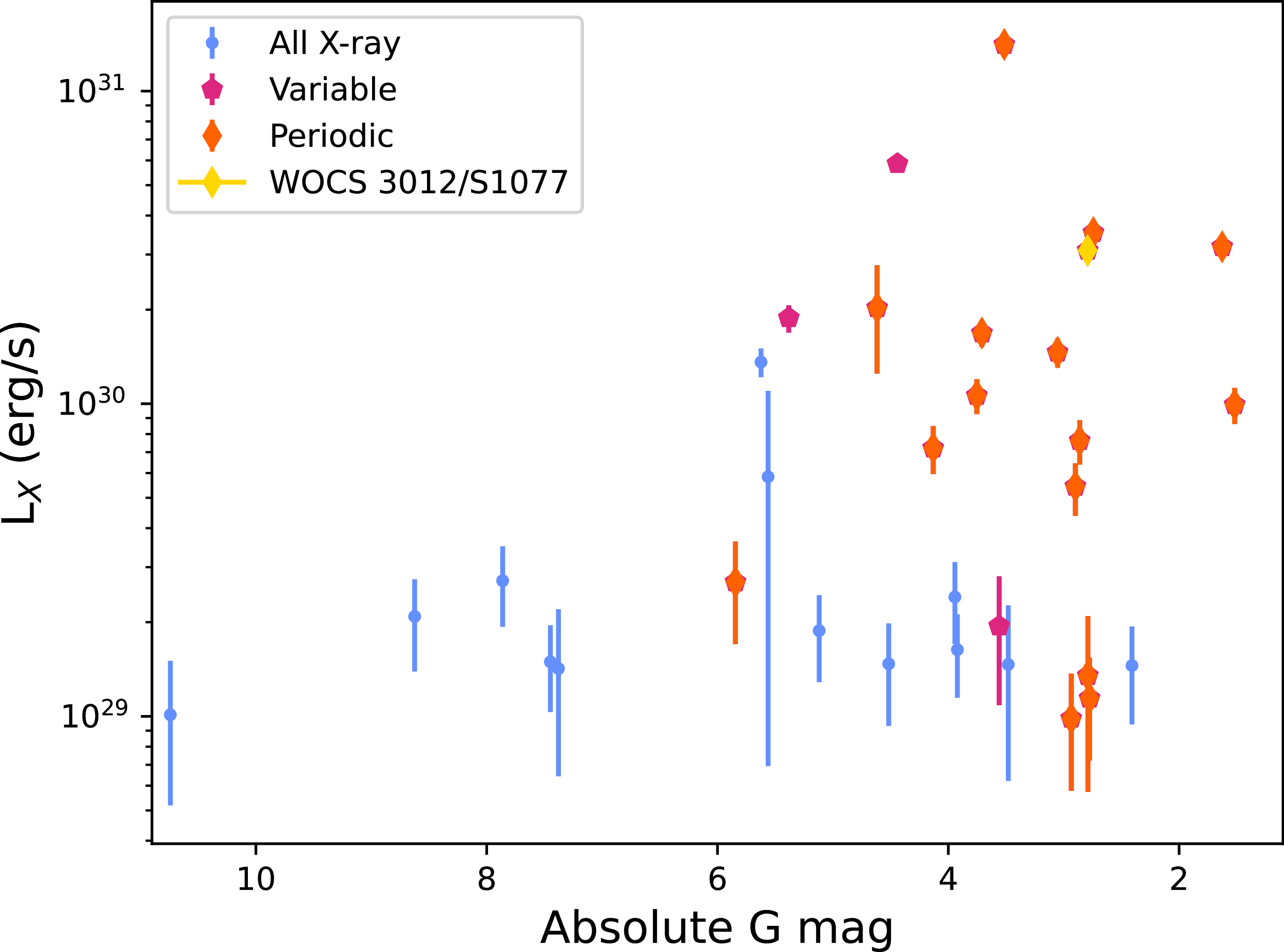

In M67, we found 31 Chandra sources associated with an individual cluster member; we plot these sources and the optical variables on M67’s CMD in Figure 5, and the X-ray luminosity vs optical magnitude in Figure 6.

We note that our X-ray associations to M67 are significantly different from previous studies (van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Tagliaferri, Belloni and Verbunt2004; Mooley & Singh Reference Mooley and Singh2015), because despite using the same X-ray observations, our cluster catalogue is significantly different. In particular, Belloni et al. (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998)’s ROSAT study, which uses a very different ground-based cluster catalogue (where the typical uncertainties are on the order of Gaia at 21st magnitude (

![]() $\sim$

1 mas/yr), which is the limiting mag of Gaia). We do not attempt to replicate this particular study because the ROSAT positional uncertainty is significant (ranging from 3" to 29"), and although M67 as an OC is less crowded than a globular cluster, that positional uncertainty is still large enough that there can be multiple optical counterparts to a given X-ray source. Using Belloni et al. (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998)’s positions and uncertainties, we found that the only ROSAT sources with relatively small positional uncertainties, which crossmatched to an individual Gaia cluster member, were also found with the Chandra data.

$\sim$

1 mas/yr), which is the limiting mag of Gaia). We do not attempt to replicate this particular study because the ROSAT positional uncertainty is significant (ranging from 3" to 29"), and although M67 as an OC is less crowded than a globular cluster, that positional uncertainty is still large enough that there can be multiple optical counterparts to a given X-ray source. Using Belloni et al. (Reference Belloni, Verbunt and Mathieu1998)’s positions and uncertainties, we found that the only ROSAT sources with relatively small positional uncertainties, which crossmatched to an individual Gaia cluster member, were also found with the Chandra data.

In M67, two X-ray sources that are brighter and bluer than the main sequence turnoff are blue stragglers, two X-ray sources located above sub-giant branch stars are evolved BSS/yellow stragglers, and one X-ray source located below the sub-giant branch is a sub-subgiant star (GaiaDR3 ID 604921030968952832). Geller et al. (Reference Geller2017) found two M67 sources as sub-subgiant stars, GaiaDR3 ID 604921030968952832 (S1063), GaiaDR3 ID 604972089540120832 (S1113), and both of those show X-ray emission and are binaries.

Unlike IC 2602 and NGC 2632, where the X-ray studies are complete (if not contaminated due to eROSITA positional uncertainties), the Chandra and XMM pointings only targeted near the centre of the cluster, and thus our knowledge of M67’s contents is less complete.

For the X-ray sources associated with Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024)’s M67 catalogue, 27 have been studied spectroscopically by Geller et al. (Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015). 21 of these have binary membership classification. Many of these systems are variable, with Gaia variability flags solar-like, ECL, DSCT, RS, and have periods reported in the literature. We note that only 6 of the M67 X-ray sources do not have binary membership (Table 4).

Figure 2. X-ray luminosity (eROSITA band) versus absolute G magnitude for X-ray sources in IC 2602. Sources with variability flags from Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023) are labelled in orange pentagons, with periodic sources marked with pink diamonds. Three sources (yellow triangles) had radio emission associated with them, but were not flagged as variable by Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023).

From the VLA observation pointed at M67’s centre, we identified 50 radio point sources. Of these, only four matched to X-ray and optical sources detected by Chandra and the complete Gaia catalogue of the central region of M67. Two were classified as QSO/AGN and were previously classified as M67 candidate members by Fan et al. (Reference Fan1996). Gaia DR3 604918174820102400 is not classified as a cluster member by Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024) and is too faint to have parallax and proper motions measured, but has an 8.4 day optical period. This optical period may be more consistent with a non-member star than an AGN.

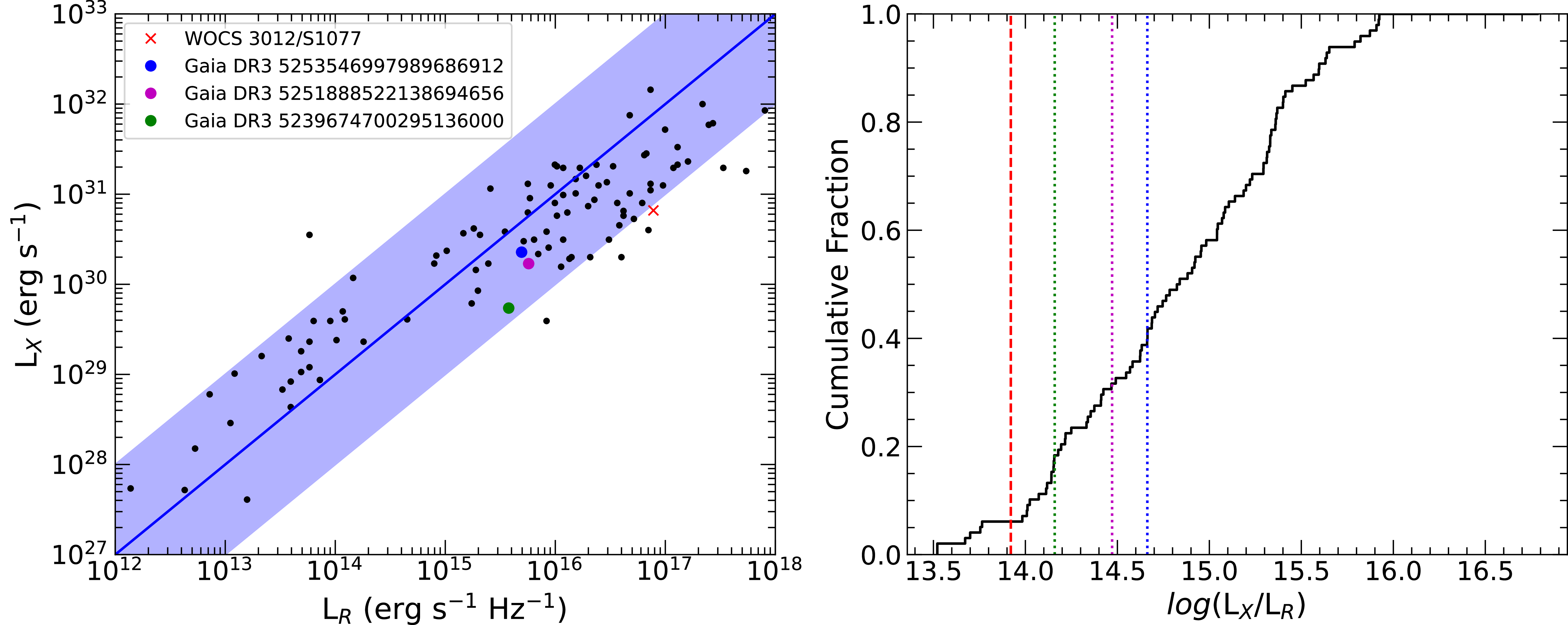

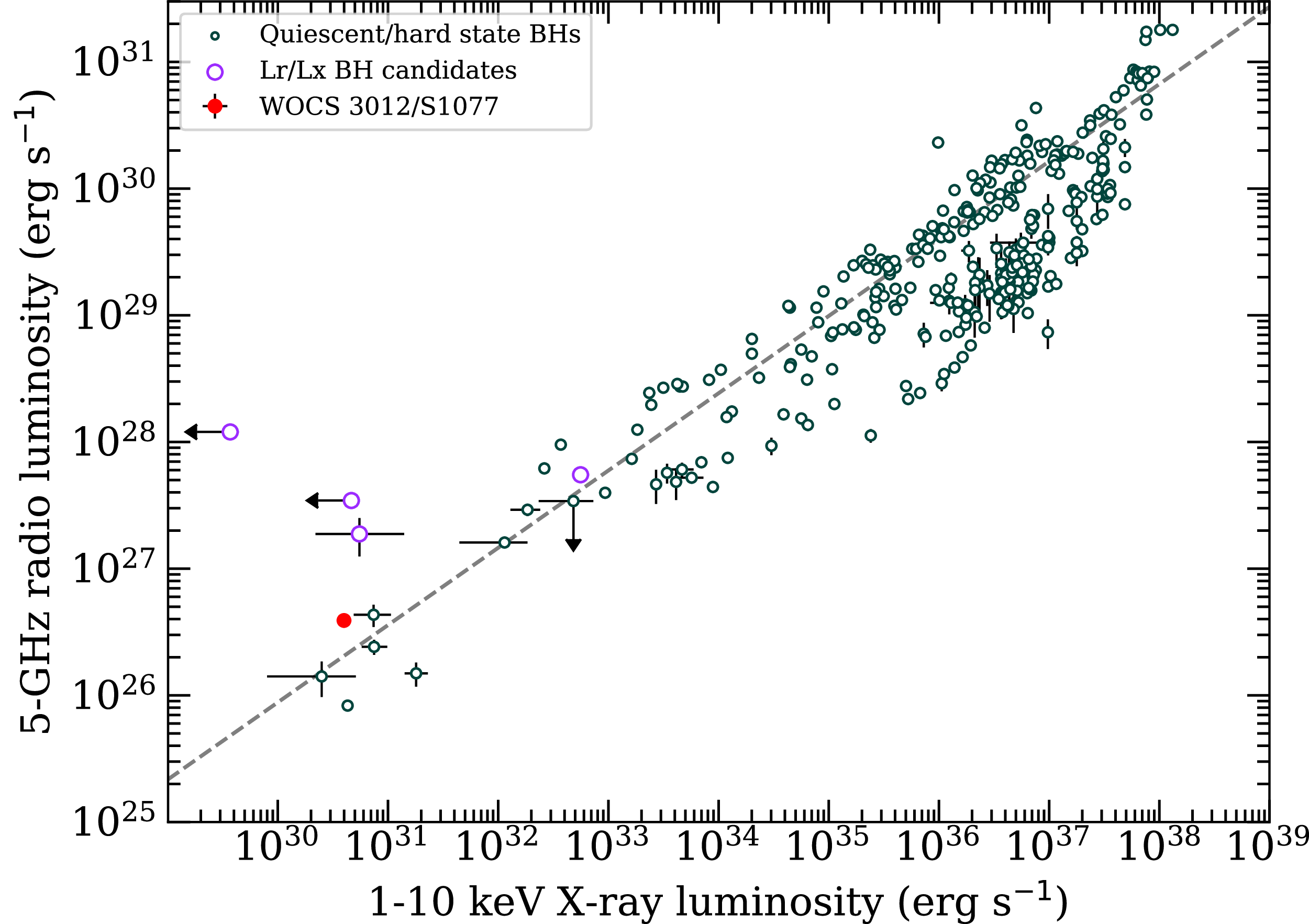

Gaia DR3 604921855602675968 (WOCS 3012/S1077) is a cluster member, both from Gaia proper motions (Hunt & Reffert Reference Hunt and Reffert2024), but also confirmed via spectroscopy (Geller et al. Reference Geller, Latham and Mathieu2015). The 10 GHz radio luminosity of this source, assuming the distance to M67, is

![]() $3.96 \pm 0.25 \times 10^{26}$

erg/s. We analysed the radio and X-ray luminosities, comparing them to both chromospherically active binary stars (Guedel et al. Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995), (Figure 7) as well as quiescent black hole binaries in Figure 8. In Figure 7, we see that WOCS 3012/S1077 falls in the scatter of the luminous end of the Guedel et al. (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995) relationship for chromospherically active binaries (and on the flatter part of the cumulative distribution function) and also fits neatly on the radio/X-ray correlation for a quiescent X-ray binary. In contrast, the three radio/X-ray sources identified in IC 2602 do not fit on the X-ray binary correlation plane at all, but do fit in the Guedel et al. (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995) correlation.

$3.96 \pm 0.25 \times 10^{26}$

erg/s. We analysed the radio and X-ray luminosities, comparing them to both chromospherically active binary stars (Guedel et al. Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995), (Figure 7) as well as quiescent black hole binaries in Figure 8. In Figure 7, we see that WOCS 3012/S1077 falls in the scatter of the luminous end of the Guedel et al. (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995) relationship for chromospherically active binaries (and on the flatter part of the cumulative distribution function) and also fits neatly on the radio/X-ray correlation for a quiescent X-ray binary. In contrast, the three radio/X-ray sources identified in IC 2602 do not fit on the X-ray binary correlation plane at all, but do fit in the Guedel et al. (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995) correlation.

Figure 3. CMD for NGC 2632. Black x’s are X-rays from eROSITA, green diamonds are

![]() $\delta$

Scuti/

$\delta$

Scuti/

![]() $\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, purple pentagons are ACV stars, red triangles are RS Canum Venaticorum, teal squares are eclipsing binaries, and orange points are solar-like variability.

$\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, purple pentagons are ACV stars, red triangles are RS Canum Venaticorum, teal squares are eclipsing binaries, and orange points are solar-like variability.

If the radio/X-ray emission from WOCS 3012/S1077 is due to a compact object and is not of stellar origin, it is more likely to be from a black hole than a neutron star. While neutron stars do sometimes occupy the location on the radio/X-ray correlation generally occupied by black holes, very few neutron stars produce X-ray luminosity this faint (Heinke et al. Reference Heinke2003, Reference Heinke2006; Bahramian et al. Reference Bahramian2015; Degenaar et al. Reference Degenaar2017; van den Eijnden et al. Reference van den Eijnden2021; Postnov et al. Reference Postnov, Kuranov, Yungelson and Gil’fanov2022). Because the VLA observation of M67 was only a 4-h exposure, we also cannot currently rule out that the radio emission is caused by a radio flare star (e.g. Driessen et al. Reference Driessen2024).

Like the putative black hole discovered by Paduano et al. (Reference Paduano2024), WOCS 3012/S1077’s radio and X-ray emission have ambiguous interpretations, where it falls into both chromospherically active binary stars and quiescent stellar mass black holes. Spectroscopy by Geller et al. (Reference Geller2021) provides a mass ratio of the inner binary

![]() $(q=m2/m1)$

as 0.76. We assume, based on its location on the CMD, that the inner visible star has just left the main sequence, and the mass is between 1.2 and 1.3 M

$(q=m2/m1)$

as 0.76. We assume, based on its location on the CMD, that the inner visible star has just left the main sequence, and the mass is between 1.2 and 1.3 M

![]() $_\odot$

, suggesting that the unseen secondary has a minimum mass that is roughly solar, but the object’s true mass is highly dependent on the inclination angle, which is not constrained. Therefore, this spectroscopic information does not exclude a less luminous star as the unseen companion to the inner binary and also allows for a neutron star or black hole to explain the system, in the case of a very extreme inclination angle (

$_\odot$

, suggesting that the unseen secondary has a minimum mass that is roughly solar, but the object’s true mass is highly dependent on the inclination angle, which is not constrained. Therefore, this spectroscopic information does not exclude a less luminous star as the unseen companion to the inner binary and also allows for a neutron star or black hole to explain the system, in the case of a very extreme inclination angle (

![]() $\gt9$

%).

$\gt9$

%).

Figure 4. X-ray luminosity (0.5–2.3 keV) versus absolute G magnitude for X-ray sources in NGC 2632. Variable sources are denoted with orange pentagons, and periodic variable sources are marked with pink diamonds.

The long-term X-ray variability, dropping by around two orders of magnitude in X-ray over

![]() $\sim$

15 yr may provide a hint as to the nature of the unseen inner binary member. While chromospherically active binaries are known to exhibit X-ray variability (e.g. Kashyap & Drake Reference Kashyap and Drake1999; Perdelwitz et al. Reference Perdelwitz2018, among others), a change of two orders of magnitude of X-ray luminosity is highly consistent with behaviours in the accretion processes of black holes and neutron stars (e.g. Tetarenko et al. Reference Tetarenko, Sivakoff, Heinke and Gladstone2016; Panurach et al. Reference Panurach2021, of many notable examples).

$\sim$

15 yr may provide a hint as to the nature of the unseen inner binary member. While chromospherically active binaries are known to exhibit X-ray variability (e.g. Kashyap & Drake Reference Kashyap and Drake1999; Perdelwitz et al. Reference Perdelwitz2018, among others), a change of two orders of magnitude of X-ray luminosity is highly consistent with behaviours in the accretion processes of black holes and neutron stars (e.g. Tetarenko et al. Reference Tetarenko, Sivakoff, Heinke and Gladstone2016; Panurach et al. Reference Panurach2021, of many notable examples).

However, the Kepler K2 photometric lightcurve of this source (EPIC 211416111) exhibits optical variability profiles consistent with chromospherically active binaries, with clear evidence of significant stellar flaring activity. Several optical flares, including a superflare, were identified through visual inspection, all displaying the characteristic flare profile of a rapid rise followed by a relatively slower decay. In addition, notable variations in the lightcurve shape suggest varying starspot activity. Taken together, these findings indicate that this source is likely a chromospherically active binary, rather than a quiescent black hole. However, if the chromosperic activity is coming from a very spun-up primary star at an extreme inclination angle, then it would be possible for this system to also host a quiescent stellar mass black hole.

4. Summary and conclusions

We take advantage of the wealth of multiwavelength surveys, from X-ray to optical to radio, and we search for multiwavelength contents of three OCs, IC 2602 (30 Myr), NGC 2632 (0.75 Gyr), and M67 (4 Gyr), using archival X-ray and radio data, and Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024)’s Gaia catalogue of cluster members. We identified 77 X-ray sources in IC 2602, many of which were variable systems, and detected evidence of chromospherically active binaries in the EMU survey. In NGC 2632, we found 31 X-ray sources, 27 of which were variable.

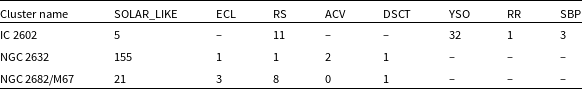

Table 6. Gaia variability flags (Eyer et al. Reference Eyer2023) for stellar members of the three clusters: solar-like variability (SOLAR_LIKE), eclipsing binaries (ECL), RS Canum Venaticorum (RS),

![]() $\alpha^2$

CVn and associated stars (ACV),

$\alpha^2$

CVn and associated stars (ACV),

![]() $\delta$

Scuti/

$\delta$

Scuti/

![]() $\gamma$

Doradus/SX Phoenicis stars (DSCT), young stellar objects (YSO), RR Lyrae (RR), and slowly pulsating B star (SBP). The main types of variability are either due to rotation (ACV, RS, SOLAR_LIKE) or pulsation (DSCT, RR, SPB).

$\gamma$

Doradus/SX Phoenicis stars (DSCT), young stellar objects (YSO), RR Lyrae (RR), and slowly pulsating B star (SBP). The main types of variability are either due to rotation (ACV, RS, SOLAR_LIKE) or pulsation (DSCT, RR, SPB).

Figure 5. CMD for M67. X-rays from Chandra are denoted in x’s, and X-rays from XMM-Newton are denoted by purple plusses. Different Gaia variability classifications are shown, a green diamond for pulsating systems

![]() $\delta$

Scuti/

$\delta$

Scuti/

![]() $\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, teal squares for eclipsing binaries (which are also X-ray sources), red triangles for RS Canum Venaticorum (which are also X-ray sources), and orange dots for solar-like variability.

$\gamma$

Doradus/SX Pheonicis, teal squares for eclipsing binaries (which are also X-ray sources), red triangles for RS Canum Venaticorum (which are also X-ray sources), and orange dots for solar-like variability.

NGC 2632 contained the largest number of variable stars (155 stars with solar-like variability). IC 2602 contains a large number of young solar objects, 1 RR Lyrae star, 3 slowly pulsating B stars, and 11 RS Canum Venaticorum. In contrast, M67 contains fewer variable systems, only 21 stars with solar-like variability, and 8 RS Canum Venaticorum stars, with 3 eclipsing binaries, and 1 pulsating DSCT. The X-ray contents of the clusters with known optical variability are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4, and the overall summary of the optical variability is summarised in Table 6.

Figure 6. X-ray luminosity (0.5–7.0 keV) versus absolute G magnitude for M67’s X-ray sources. Pink diamonds denote periodic variability, while orange pentagons show variability flags from Eyer et al. (Reference Eyer2023).

The global study of optical variability in Anderson & Hunt (Reference Anderson and Hunt2025) shows that the fraction of types of variables is dependent on age; young systems like IC 2602 are expected to have a significant number of YSOs. Older systems like NGC 2632 will have a large fraction of solar-like variables, which we also see. At gigayear ages like M67, one expects a rather low fraction of RS systems, however, that is the second highest amount of variable systems seen in M67, highlighting its uniqueness as an old and massive OC. Gaia gives us a chance to do a population study of a massive amount of OCs in the optical, and it is currently unknown how much radio and X-ray flux can be observed as a function of age. With the advent of all sky X-ray and radio surveys, this question can be addressed for the first time. With a larger sample, it may be possible to understand the detailed properties of a cluster’s contents by its overall X-ray flux.

M67 may harbour more radio and X-ray sources than the 31 cluster X-ray sources detected, but with the current coverage, we do not yet have a complete picture of its contents, but what we do know is already illuminating.

Figure 7. The location of IC 2602 radio/X-ray sources (Table 5) and WOCS 3012/S1077 on the relation of radio and X-ray for active binaries from Guedel et al. (Reference Guedel, Schmitt and Benz1995). Adapted from Paduano et al. (Reference Paduano2024). The three sources in IC 2602 fall firmly on the correlation for active binaries. WOCS 3012/S1077 (dashed line in left hand side) falls in the scatter near the correlation.

Figure 8. Location of WOCS 3012/S1077 on the radio/X-ray correlation for black holes, next to known quiescent black holes, and black hole candidates. WOCS 3012/S1077 occupies a space on this correlation that is near where one would expect to find a quiescent black hole, based on the X-ray and radio. In comparison, the three X-ray/radio sources identified in IC 2602 are much fainter in X-ray, and several orders of magnitude louder in radio than than known X-ray binaries, and are not near the correlation plane at all. Figure modified from Bahramian et al. (Reference Bahramian2018).

Modelling dynamical stellar evolution in clusters is one of the most pressing topics in modern astronomy; knowing the behaviours of all individual cluster stellar members is vital for benchmarking simulations of dynamical evolution in star clusters (Hurley & Shara Reference Hurley and Shara2002; Hurley, Aarseth, & Shara Reference Hurley, Aarseth and Shara2007). After around 10 Myr, black holes and neutron stars are expected to start forming in a star cluster system, but their final fates, and if they are retained in the clusters at all are unknown, because their natal kicks are currently not well constrained. Therefore, it is especially interesting to examine these clusters for potential black holes/neutron stars.

This paper demonstrates that by combining modern X-ray and radio surveys, along with new optical cluster studies, it is possible to be sensitive to the high energy emission of compact objects in the very wide variety of OCs in the Milky Way. Thanks to the wide variety of optical data available on these stars, it is also possible to probe a black hole origin for the high energy emission, as well as capture the broad range of stellar activity in these clusters, which all serve the purpose of better improving models of dynamical evolution in star clusters.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the referee for their helpful comments which greatly improved the manuscript. KCD thanks Aaron Geller for helpful discussion and is indebted to Susmita Sett for her LaTeX skills. This work has made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement. This work is based on data from eROSITA, the soft X-ray instrument aboard SRG, a joint Russian-German science mission supported by the Russian Space Agency (Roskosmos), in the interests of the Russian Academy of Sciences represented by its Space Research Institute (IKI), and the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR). The SRG spacecraft was built by Lavochkin Association (NPOL) and its subcontractors and is operated by NPOL with support from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE). The development and construction of the eROSITA X-ray instrument was led by MPE, with contributions from the Dr. Karl Remeis Observatory Bamberg & ECAP (FAU Erlangen-Nuernberg), the University of Hamburg Observatory, the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP), and the Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics of the University of Tübingen, with the support of DLR and the Max Planck Society. The Argelander Institute for Astronomy of the University of Bonn and the Ludwig Maximilians Universität Munich also participated in the science preparation for eROSITA. Facilities: Gaia, XMM-Newton, eROSITA, Chandra X-ray Observatory, ASKAP, VLA Software: astropy (Astropy Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2013), CASA (CASA Team et al. Reference Team2022), matplotlib (Hunter Reference Hunter2007), NumPy (Harris et al. Reference Harris2020), pandas (McKinney Reference McKinney, van derWalt and Millman2010), and LSDB (Caplar et al. Reference Caplar2025)

Data availability statement

All data is publicly available.

Appendix

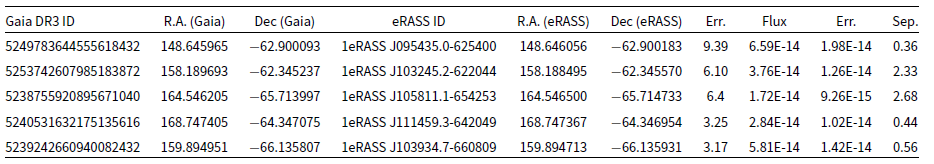

We include the crossmatch catalogues of X-ray and optical for IC 2602, NGC 2632 and M67. The X-ray information for IC 2602 and NGC 2632 come from eROSITA, and the X-rays for M67 come from Chandra. All three clusters were crossmatched with Gaia, and sub-selected for cluster membership based on Hunt & Reffert (Reference Hunt and Reffert2024). We include eRASS ID, R.A & Dec and positional error from eROSITA, along with the 0.5–2.3 keV flux in erg/s and flux error, and the Gaia ID, R.A. and Dec from optical, along with the maximum match separation. For M67, we include the same information from Gaia and NWAY, and include the Chandra positions and fluxes. A preview of these tables is displayed below.

Table A1. Gaia and eRASS crossmatches for IC 2602 and NGC 2632.

Table A2. Gaia and Chandra crossmatches for M67.