Introduction

Cochlear implants (CIs) are neural prostheses that are implanted in the cochlea and stimulate the auditory nerve, restoring some hearing capacity after its partial or complete loss (Zeng, Reference Zeng2022). The speech signal CIs convey is less fine-grained than the one provided by normal hearing conditions (Chatterjee & Peng, Reference Chatterjee and Peng2008; Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2020), with in particular altered transmission of the fundamental frequency (F0) information affecting the processing of prosody (Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2020). For example, CI-hearing conditions can affect how lexical stress perception (e.g., distinguishing between the noun CONtent and the adjective conTENT) takes place in languages where this information is conveyed by F0 modulations (e.g., English, Dutch). In particular, individuals with CIs appear to weigh F0 information in lexical stress perception to a lesser extent than individuals with normal hearing, while relying more on other cues such as intensity and vowel duration (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022). Additionally, alterations in lexical stress perception have been shown when individuals with normal hearing listen to vocoded speech stimuli, which mimic the reduced availability of F0 in CI-mediated speech by dividing the audible frequency range into a fixed number of frequency bins. In this case, individuals with normal hearing use less effectively (Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2024) or completely disregard (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022) F0 information in lexical stress perception.

The multimodal nature of human communication offers several affordances for successful comprehension (Holler & Levinson, Reference Holler and Levinson2019), which can support the decoding of disrupted speech input. In face-to-face interactions, interlocutors provide visual information such as facial expressions (Guaïtella et al., Reference Guaïtella, Santi, Lagrue and Cavé2009; Nota, Trujillo, & Holler, Reference Nota, Trujillo and Holler2023), lip movements (Campbell, Reference Campbell2008; Drijvers & Holler, Reference Drijvers and Holler2023; McGurk & MacDonald, Reference McGurk and MacDonald1976; Sumby & Pollack, Reference Sumby and Pollack1954), and iconic gestures (i.e., gestures representing meaning; Drijvers & Özyürek, Reference Drijvers and Özyürek2017; Holle et al., Reference Holle, Obleser, Rueschemeyer and Gunter2010; Ter Bekke et al., Reference Ter Bekke, Drijvers and Holler2024a, Reference Ter Bekke, Drijvers and Holler2024b) that facilitate speech comprehension. In fact, several studies showed that listeners benefit more from visual information in speech perception when the acoustic input is degraded (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Kitterick, Jones, Sumner and Stacey2019; Desai et al., Reference Desai, Stickney and Zeng2008; Drijvers & Özyürek, Reference Drijvers and Özyürek2017, Reference Drijvers and Özyürek2020; Krason et al., Reference Krason, Fenton, Varley and Vigliocco2022; Rouger et al., Reference Rouger, Lagleyre, Fraysse, Deneve, Deguine and Barone2007; P. C. Stacey et al., Reference Stacey, Kitterick, Morris and Sumner2016; Sumby & Pollack, Reference Sumby and Pollack1954; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Li, Shen, Yu and Feng2024).

During communication, speakers produce not only lip movements and iconic gestures, but also rapid up-and-down strokes of the hand called “beat gestures” (McNeill, Reference McNeill1992). Beat gestures highlight the prominence of an associated linguistic unit (Krahmer & Swerts, Reference Krahmer and Swerts2007), for example contributing to marking prosodic focus in sentences (Dimitrova et al., Reference Dimitrova, Chu, Wang, Özyürek and Hagoort2016). Recent studies showed that the timing of beat gestures can even bias lexical stress perception, a phenomenon referred to as the manual McGurk effect (Bosker & Peeters, Reference Bosker and Peeters2021; Bujok et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2024; Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025; Cos et al., Reference Cos, Bujok and Bosker2024; Maran & Bosker, Reference Maran and Bosker2024; Rohrer et al., Reference Rohrer, Bujok, Van Maastricht and Bosker2024, Reference Rohrer, Bujok, van Maastricht and Bosker2025): a beat gesture falling on the first syllable of a disyllabic minimal pair (e.g., content) biases towards perceiving a strong-weak (SW) stress pattern (e.g., the noun CONtent), while a beat gesture falling on its second syllable biases towards perceiving a weak-strong (WS) stress pattern (e.g., the adjective conTENT). While minimal pairs are employed as an experimental tool in manual McGurk studies to test the perception of lexical stress, they are not the only instances in which this linguistic feature is relevant. In fact, lexical stress influences online comprehension of non-minimal word pairs by constraining the activation of lexical candidates, as shown both by priming (van Donselaar et al., Reference van Donselaar, Koster and Cutler2005) and eye-tracking (Kong & Jesse, Reference Kong and Jesse2017; Reinisch et al., Reference Reinisch, Jesse and McQueen2010) studies (see also Bujok et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2024 for a similar approach to beat gesture-speech integration), emphasizing the relevance of accurate lexical stress perception in natural conversation.

In light of the reduced lexical stress perception observed when individuals with normal hearing listen to vocoded speech (Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2024) and the different strategies employed by CI users in this process (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022), beat gestures might aid speech processing when F0 information is disrupted. In particular, the beat gestures produced by the speaker might represent an additional cue that CI users can weigh more heavily in speech perception, mirroring strategic weighing processes based on other cues to lexical stress (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022) or lexical-semantic features (Richter & Chatterjee, Reference Richter and Chatterjee2021) previously shown in the literature.

The present study tested whether the manual McGurk effect can be observed in vocoded speech, here presented to individuals with normal hearing to mimic the reduced availability of F0 information that characterizes CI-mediated speech. The first goal of the present study was to investigate if beat gestures might bias lexical stress perception in vocoded speech, in order to lay the foundations for future work investigating beat gesture-speech integration in CI users. Importantly, in contrast to face-to-face conversations, listeners also often face situations in which they receive speech only via the auditory channel (e.g., phone calls, listening to podcasts/radio). In these instances, speech comprehension can be challenging for CI users, since they cannot rely on visual information to compensate for the degraded acoustic input they receive. One solution to this issue might be provided by software and apps generating avatars that move to the prosody of an interlocutor’s speech, providing CI users with artificially generated visual cues (i.e., gestures) supporting comprehension. Accordingly, the second goal of this study was to test whether the manual McGurk effect can be observed when the gestures are made by an avatar, complementing previous studies testing audiovisual integration based on avatars’ facial expressions (Nota, Trujillo, Jacobs, et al., Reference Nota, Trujillo, Jacobs and Holler2023), lip movements (Schreitmüller et al., Reference Schreitmüller, Frenken, Bentz, Ortmann, Walger and Meister2018), and beat gestures (Treffner et al., Reference Treffner, Peter and Kleidon2008).

We expected a significant manual McGurk effect when an avatar made beat gestures while vocoded speech was produced, possibly even with larger effects compared to unprocessedFootnote 1 speech.

Methods

Participants

Fifty participants (47 females, 3 males; mean age = 19.26 years, range = 18–28) were recruited from the Radboud Research Participation System. Participants were native Dutch speakers, with normal hearing and normal or corrected-to-normal vision, as self-reported in an initial screening questionnaire when joining the Radboud Research Participation System. The larger proportion of female participants, compared to participants with male or non-binary gender identities, might have stemmed from the demographics of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Radboud University, at which all the participants were students. All participants gave informed consent, as approved by the Ethics Committee of the Social Sciences department of Radboud University (project code: ECSW-LT-2023-10-11-21350), and were reimbursed with course credit for their participation.

Materials and design

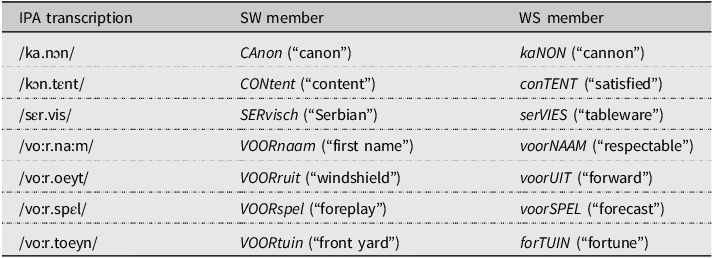

Audio recordings of 7 Dutch disyllabic minimal pairs were used (Table 1), taken from the publicly available materials of a study in which acoustic stress information was manipulated over 7-step F0 continua between naturally produced SW (e.g., CONtent) and WS (e.g., conTENT) stress (Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025). In these recordings, each syllable was acoustically ambiguous in intensity and duration, while the word-level F0 contour was manipulated. Note that, as shown by recent work (Severijnen et al., Reference Severijnen, Bosker and McQueen2024), Dutch talkers mainly use F0, intensity, and duration as cues to lexical stress, with vowel quality having a relatively marginal role. For each minimal pair, 3 recordings were used: the original SW and WS recordings and the most perceptually ambiguous audio step based on Bujok and colleagues’ (Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025) data (see Section 1 in Supplementary Materials). A vocoded version of each recording was created, adopting the procedure of Fleming and Winn (Reference Fleming and Winn2022; for specifics, see the online data repository). Note that in the study of Fleming and Winn (Reference Fleming and Winn2022) “a sine wave vocoder was selected because it should preserve cues to voice pitch in a way that is similar to what is available in a CI” (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022, p. 1304). This vocoder encoded F0 as the rate of amplitude modulations in the channel envelopes. Additionally, it created sidebands in the spectrum corresponding to the F0 of the voice in order to preserve information about voice pitch (Souza & Rosen, Reference Souza and Rosen2009; Whitmal et al., Reference Whitmal, Poissant, Freyman and Helfer2007). Specifically, each unprocessed stimulus was filtered into eight channels between 100 and 8000 Hz using Hann filters with 25 Hz symmetrical sidebands, with center frequencies spaced logarithmically between 160 and 6399 Hz. The temporal envelope was calculated in each channel using the Hilbert transform and sampled at a rate of 600 Hz to ensure that F0 was encoded in the envelope. Each envelope was used to modulate a corresponding sine wave matched to the analysis band, and all carrier bands were summed together to create the final vocoded stimulus. Importantly, vocoded speech was here employed to mimic in individuals with normal hearing the reduced availability of F0 information that characterizes CI-mediated hearing. However, as discussed in more detail in the “Discussion” section, the present work does not assume that vocoded speech might fully capture CI users’ experience in speech perception.

Table 1. Dutch minimal pairs employed

Note. The table shows the Dutch minimal pairs, together with IPA transcription and English translation for the Strong-Weak (SW) and Weak-Strong (WS) member. The stressed syllable is written in uppercase font.

The video of a male human avatar with a neutral face making a beat gesture was generated using DeepMotion (https://www.deepmotion.com/), based on an input video of a woman making a beat gesture. The avatar did not produce any lip movements in order to isolate the contribution of beat gestures to lexical stress perception. Note that the manual McGurk effect can be observed independently from (Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025) and without (Bosker & Peeters, Reference Bosker and Peeters2021; Rohrer et al., Reference Rohrer, Bujok, Van Maastricht and Bosker2024, Reference Rohrer, Bujok, van Maastricht and Bosker2025) visible lip movement information. The present work differs from these previous studies, as in this case the lips are visible (i.e., contrary to Bosker & Peeters, Reference Bosker and Peeters2021, and Rohrer et al., Reference Rohrer, Bujok, Van Maastricht and Bosker2024, Reference Rohrer, Bujok, van Maastricht and Bosker2025) but do not produce any movement (i.e., contrary to Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025). The results of Bujok and colleagues (Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025) indicate that the type of lip movements (i.e., producing an SW or WS word) does not affect lexical stress perception based on F0 modulations. Still, it is worth considering whether the lack of any lip movement could in principle lead participants not to consider the avatar as the speaker. In the specific case of our study, this is unlikely due to both the task’s instructions provided to the participants and the avatar’s appearance. In particular, the task’s instructions indicated to the participants that they would see and hear a speaker. As the avatar is the only element present in the employed videos (Figure 1), these instructions primed participants to consider the avatar as the source of speech. In addition, the avatar’s appearance is less sophisticated than the animations individuals are nowadays exposed to in media or movies. Thus, participants might have considered the lack of lip movements as a technical limitation in the realism of the avatar, rather than a cue towards not considering it as the speaker. Therefore, we considered that the ease of use of DeepMotion software and its free-access nature, which might be relevant for future studies based on these findings, overcame the limitations of the avatar employed, especially since our study focuses on beat gestures and not on lip movements. Relevant to the research question addressed in this study, the lack of lip movements might in principle lead to an underestimation, but not to an overestimation, of beat gesture and speech integration, therefore still allowing us to draw conclusions in case of a significant effect of beat timing. We return to this aspect of our materials in the “Discussion” section. Each of the 42 audio recordings was merged with the video of the avatar using the software Hitfilm twice (Figure 1), with the gesture’s apex (i.e., point of maximal extension) temporally aligned to the onset of the first (BeatOn1) or the second vowel (BeatOn2).

Figure 1. The Manual McGurk paradigm. Note. Schematic illustration of the paradigm. The same acoustic token was aligned with a beat gesture falling on the first syllable in the BeatOn1 condition and on the second syllable in the BeatOn2 condition. The dashed blue line approximates the avatar’s hand trajectory, while the full blue line approximates the timing of the beat gesture’s apex (i.e., point of maximal extension).

Procedure

The experiment was run online using the Gorilla experiment builder (Anwyl-Irvine et al., Reference Anwyl-Irvine, Massonnié, Flitton, Kirkham and Evershed2020). All participants used headphones or earbuds of sufficient quality, as assessed with a screening test (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Bianco, Poole, Zhao, Oxenham, Billig and Chait2021). Participants were split into two groups: one (26 participants) was exposed first to unprocessed and then to vocoded speech, and the other (24 participants) had the opposite order. The minimal difference in size between the two groups was due to a programming error.

Participants performed two two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) blocks identical in structure, one with the unprocessed and one with the vocoded speech stimuli, each preceded by a short practice block of six trials. In each block, participants were asked to indicate if they perceived an SW or a WS word. Each trial began with two members of a minimal pair presented on the screen: the member with an SW stress pattern (e.g., CONtent) on the left and the member with a WS stress pattern (e.g., conTENT) on the right. After a fixation cross, participants watched a video of an avatar making a Beat gesture falling on the first or second syllable (BeatOn1 and BeatOn2, respectively), while a word with one acoustic Stress Pattern (SW, Ambiguous, or WS) was played in the Speech Condition (Unprocessed or Vocoded) of the block. The videos were followed by the presentation of three response buttons: the member with an SW stress pattern on the left, the member with a WS stress pattern on the right, and “Ik zag een CHIMPANSEE!” (“I saw a CHIMPANZEE!”, to respond to catch trials) below in the center. After clicking on one of the options or 3996 ms passed, the next trial started after a 500 ms blank screen.

Each video was reproduced twice in the relative block (unprocessed or vocoded), leading to a total number of 168 trials of interest (84 per speech condition, in a randomized order). To motivate participants to maintain fixations on the video stimuli, 32 catch trials were additionally included (16 in each speech condition), in which participants were instructed to indicate the appearance of a chimpanzee (i.e., the avatar’s head was overlaid with a chimpanzee head).

Statistical analysis

Perceived stress data (i.e., selecting the SW or WS word; a binomial variable with 1 = SW, 0 = WS) were analyzed with generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) with logistic link function, using the R (R Core Team, 2023) packages “lme4” (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) and “car” (Fox & Weisberg, Reference Fox and Weisberg2019). The fixed-effects structure included the factors Beat (BeatOn1, BeatOn2), treatment-coded with BeatOn1 as reference level, Stress Pattern (SW, Ambiguous, WS), treatment-coded with SW as reference level, and Speech Condition (Vocoded, Unprocessed), treatment-coded with Vocoded as reference level. The random-effects structure included random intercepts and slopes for Beat and Speech Condition by Item (i.e., the minimal pair) and by Participant. P-values were obtained via ANOVA Type II Wald χ2 tests. Significant three-way interactions were examined with two-way analyses in each Stress Pattern.

As participants responded using mouse clicks rather than button presses and were not asked to respond as quickly as possible, the analysis of Response Times (RTs) data should be considered exploratory in nature. Response times were log-transformed and analyzed with linear mixed models (LMM) using the R packages “lme4” (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) and “lmerTest” (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). The fixed-effects structure included the factors Beat, Stress Pattern, and Speech Condition. The random-effects structure included random intercepts and slopes for Stress Pattern and Speech Condition by Participant and random intercepts by Item. P-values were obtained via ANOVA Type III with Satterthwaite’s method.

For both the Perceived Stress and RTs analyses, the random-effects structures were defined as the most complex possible ones without leading to convergence issues using the R package “buildmer” (Voeten, Reference Voeten2023). All the GLMM/LMM formulas used are documented in Sections 2 and 3 of the Supplementary Materials.

Results

Participants watched the screen attentively, as shown by the low percentage of missed catch trials in both Unprocessed (average: 3.5%, by-participant range: 0–18%) and Vocoded (average: 2%, by-participant range: 0–12%) speech conditions. In total, only 0.043% of the data were discarded due to missing responses (i.e., reaching the 3996 ms time-out).

Perceived stress

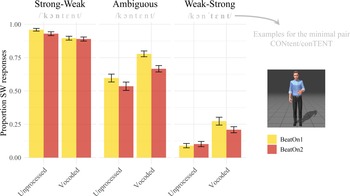

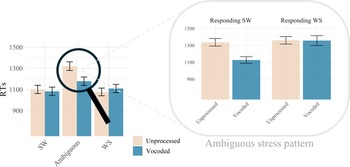

A significant main effectFootnote 2 of Beat (χ2 = 11.260, p < .001) was observed (Figure 2; see also Tables S2 and S3 in Section 4 of the Supplementary Materials; see Section 6 of the Supplementary Materials for descriptive statistics), with a higher proportion of SW responses for BeatOn1 relative to BeatOn2 (i.e., a manual McGurk effect). A significant main effect of Stress Pattern (χ2 = 2129.231, p < .001) showed an expected difference in the proportion of SW responses between SW, Ambiguous, and WS conditions, with participants showing fewer SW responses as the audio sounded more WS-like. A significant main effect of Speech Condition (χ2 = 15.009, p < .001) indicated an overall difference in the proportion of SW responses between Unprocessed and Vocoded speech, with more SW responses in the latter. This effect was modulated by stress pattern, as shown by the significant Speech Condition × Stress Pattern interaction (χ2 = 104.009, p < .001), suggesting a reduced difference between the two acoustic stress patterns (SW vs. WS) in Vocoded speech. The Beat × Speech Condition interaction, assessing a possibly enhanced manual McGurk effect in Vocoded vs. Unprocessed speech, did not reach significance (χ2 = 3.660, p = .056). However, the significant three-way interaction Beat × Stress Pattern × Speech Condition (χ2 = 6.934, p = .031) suggests that differences in the manual McGurk effect between Unprocessed and Vocoded speech emerged at specific levels of the factor Stress Pattern (i.e., SW, Ambiguous, WS). This notion is supported by the significant interaction contrasts StressPatternAmbiguous:SpeechConditionUnprocessed:BeatBeatOn2 (β = 0.808, SE = 0.346, z = 2.332, p = .020) and StressPatternWS:SpeechConditionUnprocessed:BeatBeatOn2 (β = 0.962, SE = 0.384, z = 2.506, p = .012) provided by the full model (see Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials). Accordingly, each stress pattern was examined separately. To test whether the manual McGurk effect was present in both speech conditions, each model was additionally run changing the reference level from Vocoded to Unprocessed speech.

Figure 2. Perceived stress data. Note. The manual McGurk effect, for each combination of Stress Pattern and Speech Condition, consists of the difference between BeatOn1 and BeatOn2. Mean value indicates the average of single-subject averaged proportions. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

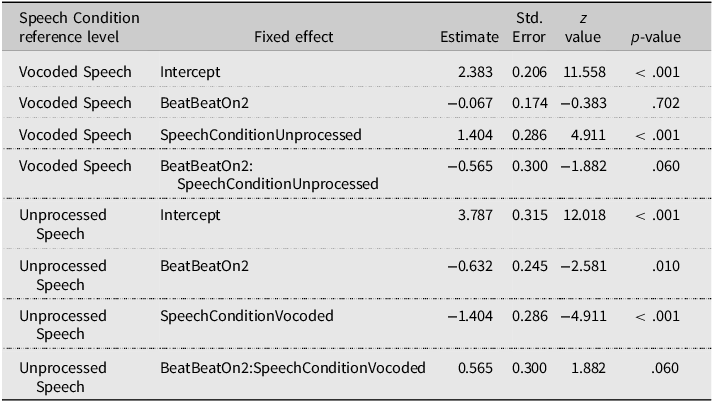

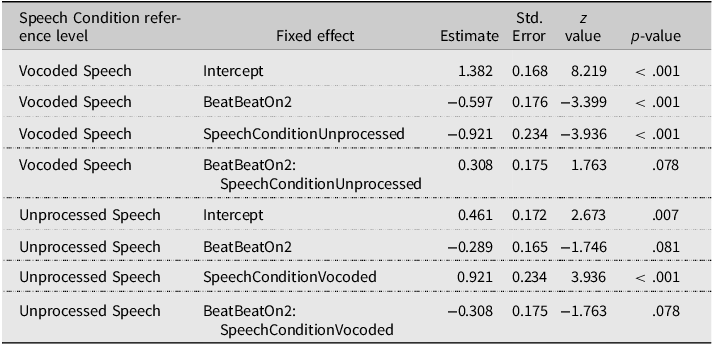

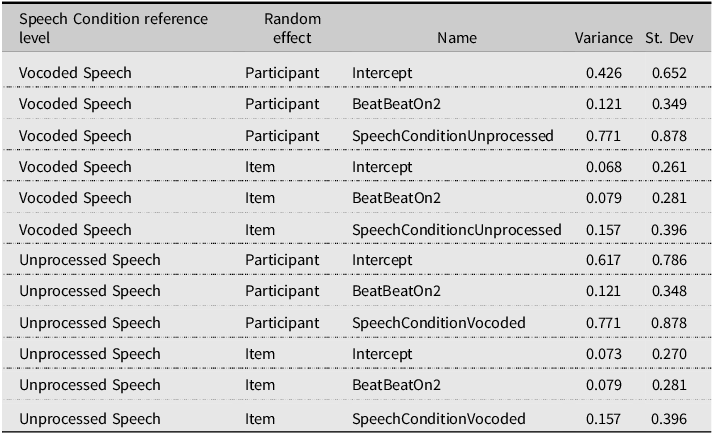

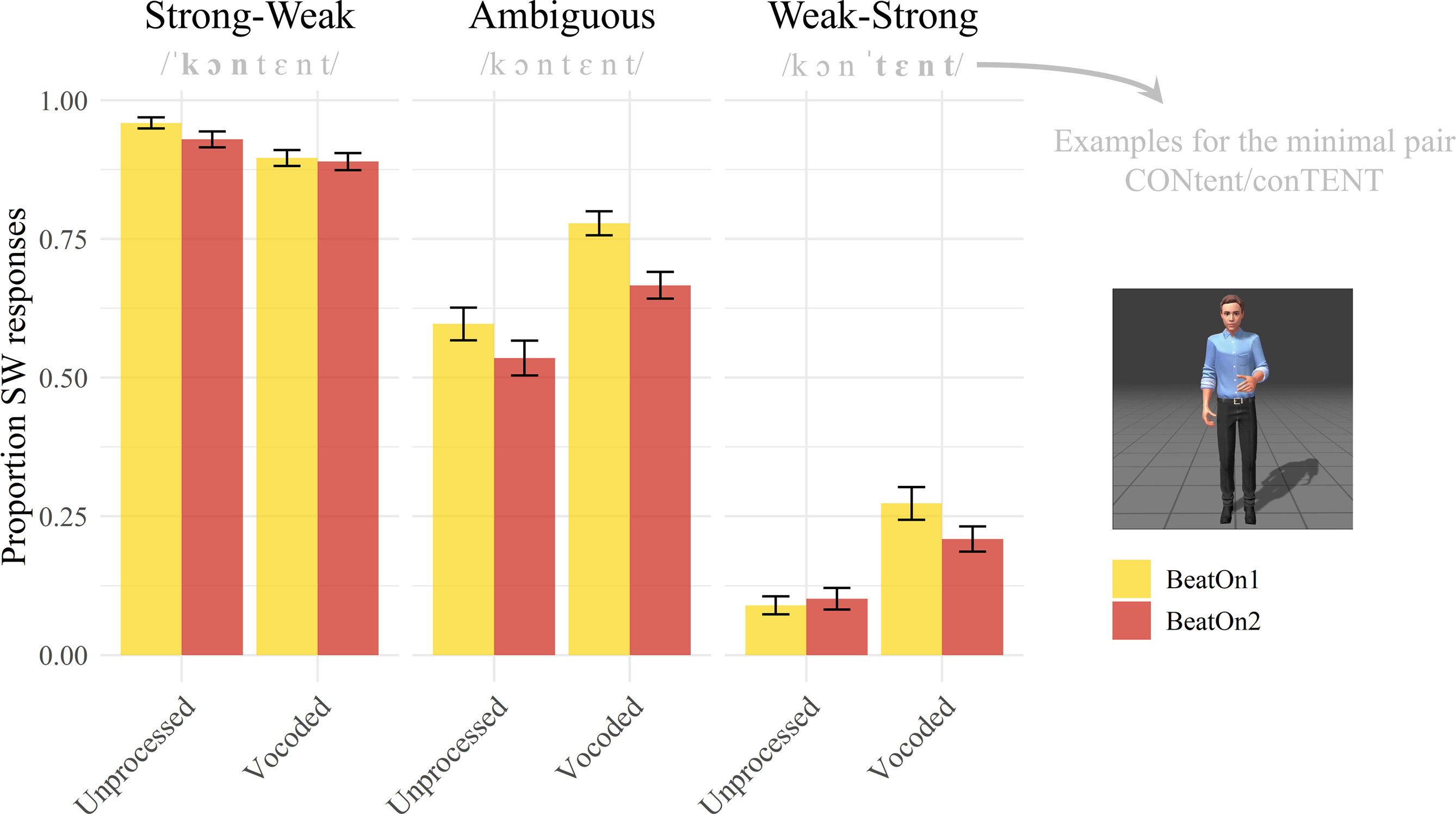

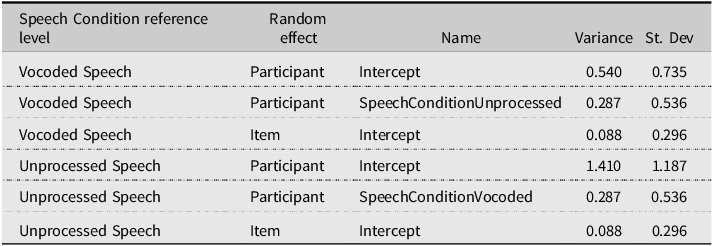

In the SW stress pattern, only a significant main effect of Speech Condition was observed (χ2 = 23.060, p < .001), indicating a larger number of SW responses when hearing Unprocessed speech. Both the main effect of Beat (χ2 = 3.266, p = .071) and the Beat × Speech Condition interaction (χ2 = 3.542, p = .060) did not reach significance. The fitted models’ estimates (Tables 2 and 3) reveal that the manual McGurk effect was not significant in Vocoded speech (BeatBeatOn2, p = .702), but reached significance in Unprocessed speech (p = .010).

Table 2. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model fixed effects’ estimates and contrasts in the SW stress pattern

Note. The table summarizes the contrasts of the GLMM model run on the SW stress pattern, including Beat and Speech Condition as fixed effects. Contrasts for Beat were treatment-coded with BeatOn1 as the reference level.

Table 3. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model random effects in the SW stress pattern

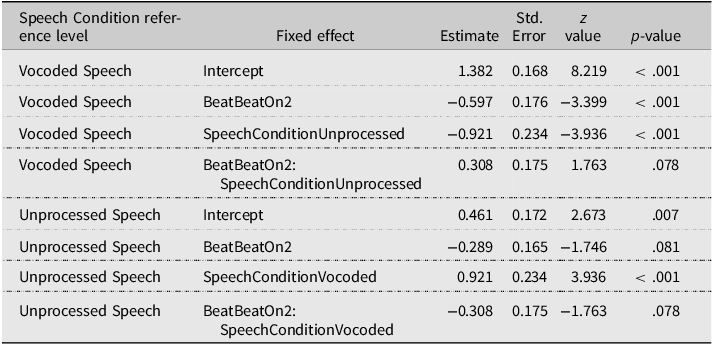

In the Ambiguous stress patternFootnote 3 , a significant main effect of Beat (manual McGurk effect) was observed (χ2 = 8.466, p = .004). A significant main effect of Speech Condition (χ2 = 12.416, p < .001) indicated a higher proportion of SW responses for the Vocoded compared to the Unprocessed speech. Since SW is the most frequent disyllabic stress pattern in Dutch (Vroomen & de Gelder, Reference Vroomen and de Gelder1995), this effect might reflect an internal bias towards perceiving the most frequent stress pattern, emerging more strongly when processing the most ambiguous acoustic signal (ambiguous F0, degraded by vocoding). Note that such a bias appears to be present both in Vocoded and Unprocessed speech (Figure 2). The Beat × Speech Condition interaction did not reach significance (χ2 = 3.109, p = .078). However, the fitted model estimates (Tables 4 and 5) reveal that the manual McGurk effect was significant for Vocoded speech (BeatBeatOn2, p < .001) only.

Table 4. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model fixed effects’ estimates and contrasts in the Ambiguous stress pattern

Note. The table summarizes the contrasts of the GLMM model run on the Ambiguous stress pattern, including Beat and Speech Condition as fixed effects. Contrasts for Beat were treatment-coded with BeatOn1 as the reference level.

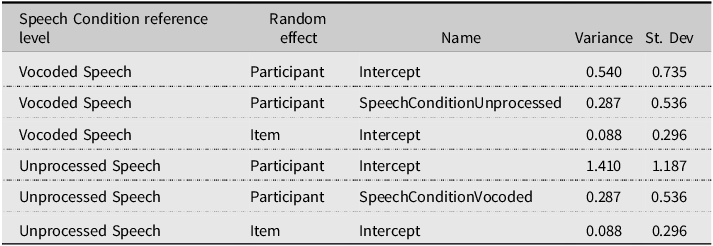

Table 5. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model random effects in the Ambiguous stress pattern

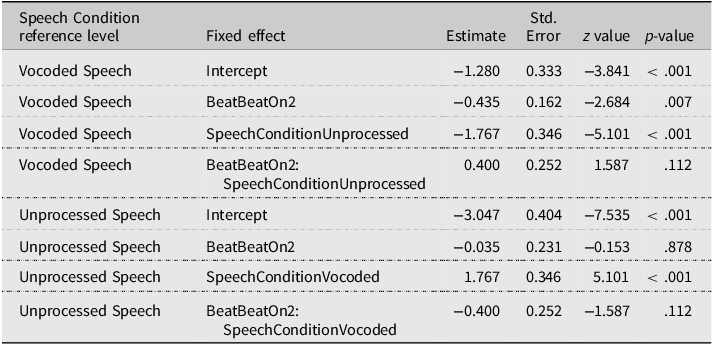

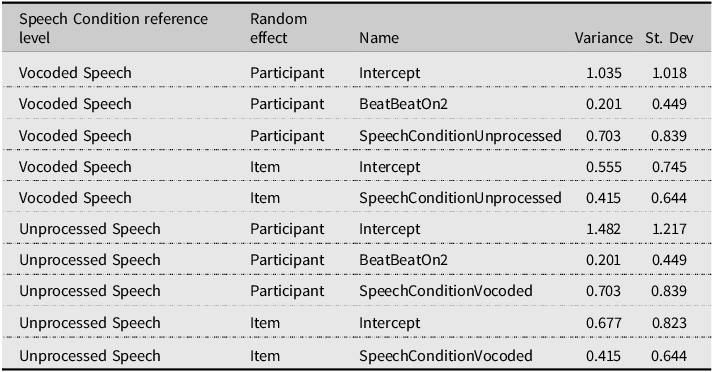

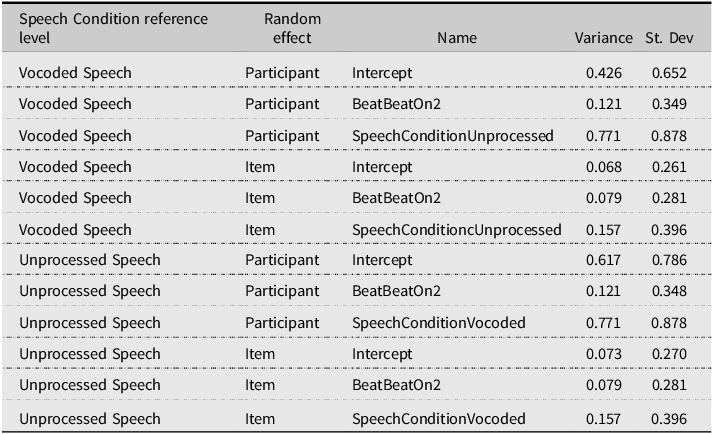

Finally, in the WS stress pattern, a significant main effect of Beat was observed (χ2 = 4.876, p = = .027), indicating a manual McGurk effect. A significant main effect of Speech Condition was observed (χ2 = 23.531, p < .001), indicating a larger proportion of SW responses for Vocoded than Unprocessed speech. The Beat × Speech Condition interaction did not reach significance (χ2 = 2.520, p = .112). The fitted model estimates (Tables 6 and 7) reveal that the manual McGurk was significant in Vocoded speech (BeatBeatOn2, p = .007) but not when Unprocessed speech was set as the reference level (p = .878).

Table 6. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model fixed effects’ estimates and contrasts in the WS stress pattern

Note. The table summarizes the contrasts of the GLMM model run on the WS stress pattern, including Beat and Speech Condition as fixed effects. Contrasts for Beat were treatment-coded, with BeatOn1 as the reference level.

Table 7. Perceived stress judgments: GLMM model random effects in the WS stress pattern

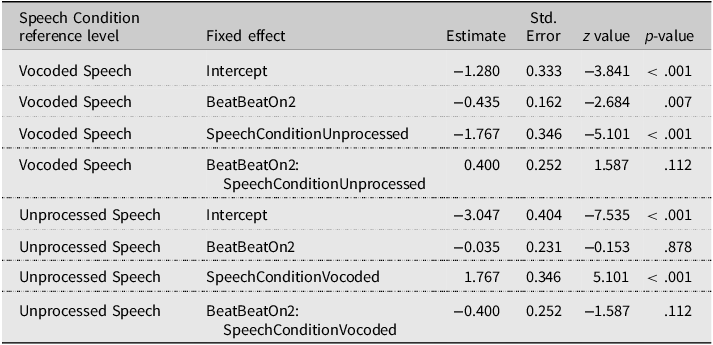

Response times

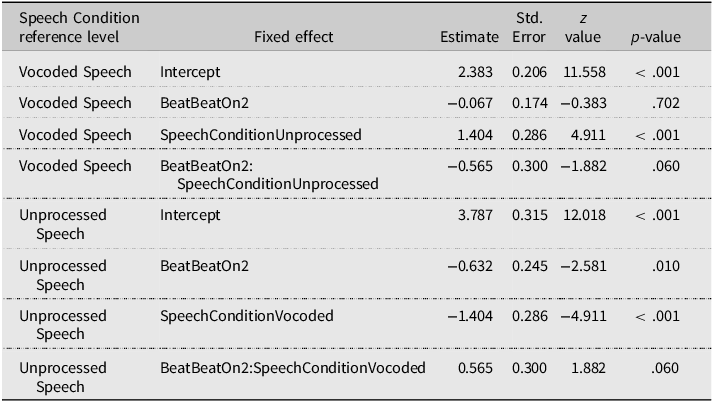

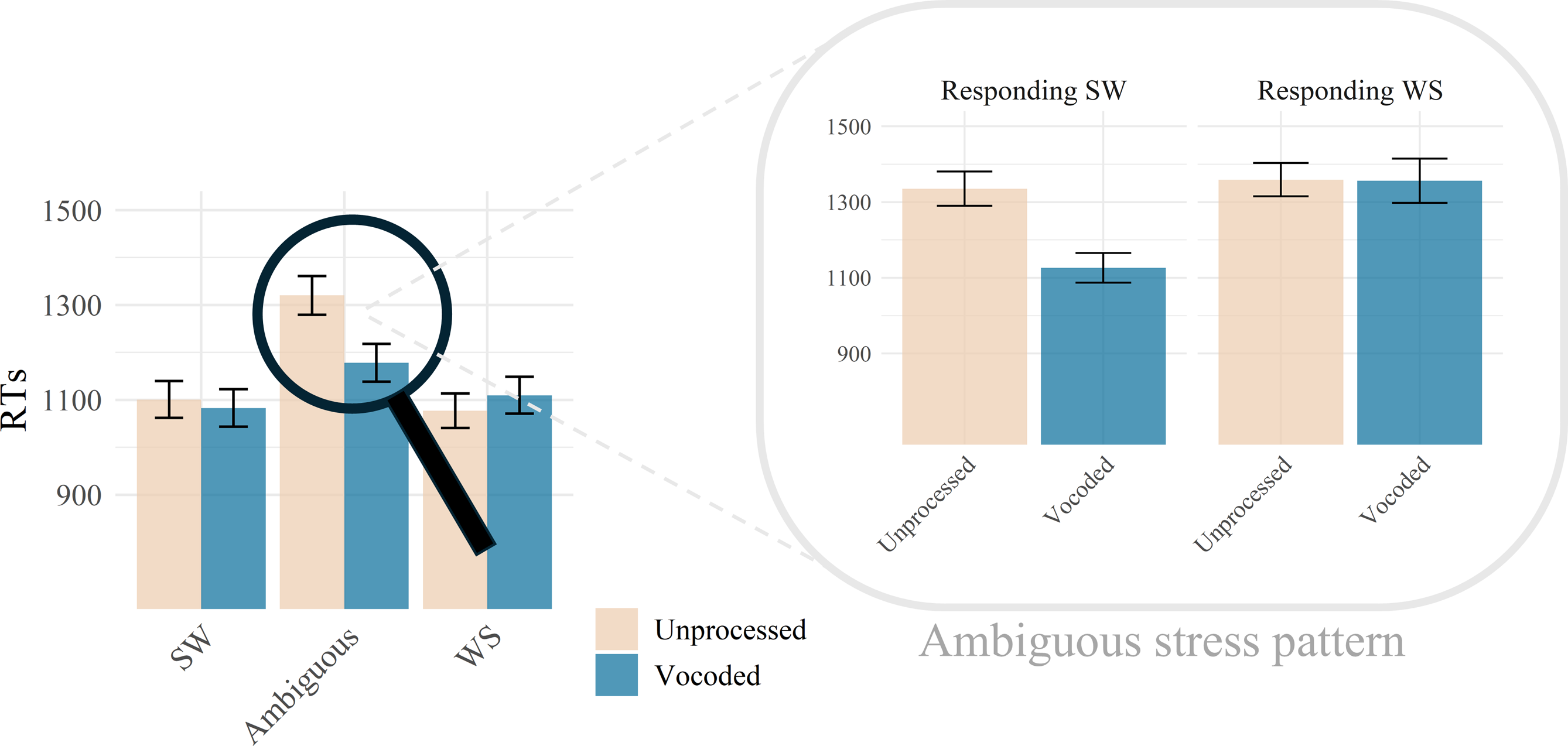

The analysis of RTs is summarized in Table 8. Due to its exploratory nature, we limit the in-text discussion to the Stress Pattern × Speech Condition (p < .001) interaction. An extensive discussion of RTs data is provided in Section 5 of the Supplementary Materials. Descriptive statistics are provided in Section 6 of the Supplementary Materials.

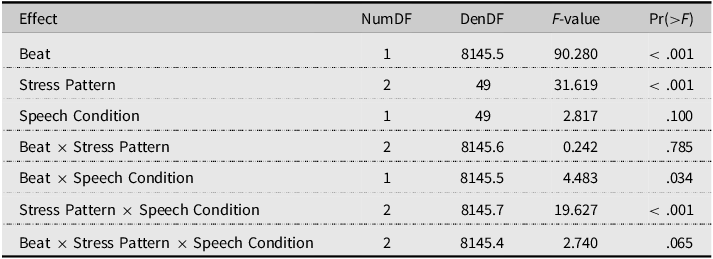

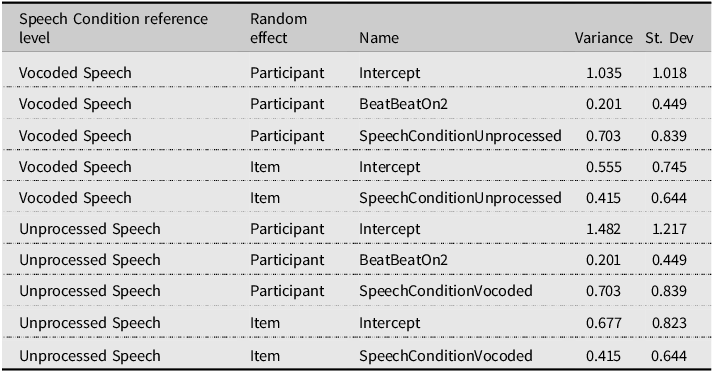

Table 8. Reaction time data

Note. The LMM analysis was run on log-transformed RTs (Type III Analysis of Variance, Table with Satterthwaite’s method).

The significant Stress Pattern × Speech Condition interaction was driven by faster RTs in the Ambiguous stress pattern for Vocoded than Unprocessed speech (p < .001, Figure 3). This could reflect facilitation driven by beat gestures when processing vocoded but not unprocessed speech. However, an alternative hypothesis is that the faster RTs stem from using heuristics based on stress pattern distributions in Dutch. As SW is the most common stress pattern in Dutch (Vroomen & de Gelder, Reference Vroomen and de Gelder1995), the alternative hypothesis would be reflected in faster RTs specifically when responding SW. We examined RTs data from the Ambiguous stress pattern, including as predictors Speech Condition and Given Response (SW/WS; see also Tables S7-S9). In line with the heuristics-based hypothesis, a significant Speech Condition × Given Response interaction was observed (p < .001), driven by differences between Unprocessed and Vocoded speech emerging only when responding SW (p < .001 Bonferroni-corrected, Figure 3). Faster RTs for responding SW compared to WS were observed in Vocoded speech only (p < .001, Bonferroni-corrected).

Figure 3. Response time data. Note. The figure illustrates the average of averaged single-subject RTs across combinations of Speech Condition and Stress Pattern (SW: Strong-Weak; Ambiguous; WS: Weak-Strong). The zoom-in illustrates the average of averaged single-subject RTs across combinations of Speech Condition and Given Response (responding SW or WS) in the Ambiguous condition. Response times are provided in ms for illustration purposes, but the analysis was based on log-transformed RTs. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Discussion

The present study successfully demonstrated that beat gestures can support the perception of vocoded speech, here chosen to mimic the reduced availability of F0 information that characterizes CI-mediated speech, especially when processing infrequent prosodic patterns. Beat gestures biased speech perception mostly when vocoded speech conveyed a stress pattern that was either ambiguous or uncommon (WS: 12%, Vroomen & de Gelder, Reference Vroomen and de Gelder1995). In these instances, listeners might have weighed incoming visual information more heavily as a source of disambiguation, since the prosodic information they retrieved from a degraded (and therefore, not fully trustworthy) speech signal was ambiguous or unexpected (i.e., infrequent).

The significant main effect of Beat indicates that beat gestures made by an avatar bias lexical stress perception, extending previous studies showing the manual McGurk effect when beat gestures were made by a human (Bosker & Peeters, Reference Bosker and Peeters2021; Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025; Cos et al., Reference Cos, Bujok and Bosker2024; Maran & Bosker, Reference Maran and Bosker2024; Rohrer et al., Reference Rohrer, Bujok, Van Maastricht and Bosker2024, Reference Rohrer, Bujok, van Maastricht and Bosker2025). The significant interaction between Beat, Stress Pattern, and Speech Condition suggests that the manual McGurk effect differed between Vocoded and Unprocessed speech at specific stress patterns. Possibly due to a lack of statistical power, the expected Beat × Speech Condition interaction failed to reach significance in any of the stress patterns when examined in isolation, despite a numerically larger effect in Vocoded speech in the Ambiguous and WS stress patterns. However, the significant StressPatternAmbiguous:SpeechConditionUnprocessed:BeatBeatOn2 and StressPatternWS:SpeechConditionUnprocessed:BeatBeatOn2contrasts, both with positive estimates (i.e., more SW-like perception, given the model’s reference levels), indicate that the BeatOn2 condition biased less towards WS perception in the Ambiguous and WS stress patterns when the speech was Unprocessed, compared to when it was Vocoded. Thus, when F0 information was disrupted by vocoding, individuals with normal hearing weighed beat gestures more heavily than when hearing unprocessed speech. While keeping in mind the differences between vocoded and CI-mediated speech discussed in the previous sections, these results suggest that beat gestures might in principle represent an additional (visual) cue to lexical stress that CI users could weight more than individuals with normal hearing, similarly to the compensatory effects based on intensity and vowel duration shown in previous work (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022). In this regard, the temporal relationship that beat gestures exhibit with pitch peak (Leonard & Cummins, Reference Leonard and Cummins2011) might make compensatory processes based on beat gestures in CI users particularly strong when decoding linguistic features that, in normal hearing, rest mainly on F0 modulations. At a broader level, such a finding would converge on the notion that CI users might deal with the altered nature of the F0 information conveyed by CIs by relying more on other speech cues (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022) or abstract linguistic features (e.g., lexical-semantic; Richter & Chatterjee, Reference Richter and Chatterjee2021). Furthermore, it would converge on the observation that CI users exploit visual cues such as lip movements in speech perception to a larger extent than individuals with normal hearing (Desai et al., Reference Desai, Stickney and Zeng2008; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Kirk, Lachs and Pisoni2003; Rouger et al., Reference Rouger, Lagleyre, Fraysse, Deneve, Deguine and Barone2007; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Li, Shen, Yu and Feng2024). Overall, these considerations motivate future studies testing whether the influence of beat gestures on speech perception is larger in CI users compared to participants with normal hearing.

As mentioned in the “Introduction” section, vocoded speech was here employed to limit the reliability of F0 cues available to individuals with normal hearing in a way that resembles CIs as a first step towards future work testing gesture-speech integration in CI users. It is important to point out that vocoded speech is not a perfect proxy for how CI-mediated speech is perceived. In fact, data from single-sided deaf patients with a CI suggest that vocoded speech and CI-mediated speech might be qualitatively different (Dorman et al., Reference Dorman, Natale, Butts, Zeitler and Carlson2017). Furthermore, both similarities and dissociations between the speech perception of normal hearing participants exposed to vocoded speech and of CI users exposed to unprocessed speech have been documented (Laneau et al., Reference Laneau, Moonen and Wouters2006; Winn, Reference Winn2020). In fact, in the study of Fleming and Winn (Reference Fleming and Winn2022), both CI users and individuals with typical hearing exposed to vocoded speech relied more on intensity and duration in lexical stress perception compared to individuals with normal hearing listening to unprocessed speech. However, individuals with typical hearing exposed to vocoded speech completely disregarded F0 information, while CI users still made use of this cue, albeit less than individuals with normal hearing exposed to unprocessed speech. These dissociations highlight the need for studies testing both CI users exposed to unprocessed speech and individuals with normal hearing exposed to vocoded speech. Furthermore, they highlight the fact that, while vocoded and CI-mediated speech might in certain instances be associated with similar performances (Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2020), possibly different strategies might be employed by the two groups (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022). It remains at present an open question whether such differences are grounded on neural plasticity events associated with the implantation of CIs (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Heo, Joo, Choi, Shim and Park2024) or the preceding sensory deprivation (Stropahl et al., Reference Stropahl, Chen and Debener2017), which by definition cannot be modelled simply by exposing individuals with normal hearing to vocoded stimuli.

As expected, vocoding degraded the perception of speech acoustic stress cues (Everhardt et al., Reference Everhardt, Sarampalis, Coler, Başkent and Lowie2024). Additionally, participants showed a tendency to perceive an SW word when hearing an Ambiguous stress pattern, and more pronouncedly so in the Vocoded speech condition. As SW is the most common disyllabic stress pattern in Dutch (88%, Vroomen & de Gelder, Reference Vroomen and de Gelder1995), when facing an ambiguous acoustic input, listeners might weigh both internal models of language frequency (hence the SW bias and the faster RTs when responding SW to vocoded ambiguous items) and the gestures made by the interlocutor (hence the difference between BeatOn1 and BeatOn2). Notably, in previous manual McGurk studies employing the same unprocessed speech materials as this study, but paired with videos of a person rather than an avatar (Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025; Cos et al., Reference Cos, Bujok and Bosker2024; Maran & Bosker, Reference Maran and Bosker2024), no such an internal bias towards SW was present. Since the avatar’s gestures are less natural than human ones (e.g., in terms of velocity, size, and trajectory), the beat gestures produced by the avatar might not have been considered a fully reliable visual cue. Hence, the avatar’s beat gestures might have influenced speech perception slightly less than beat gestures produced by humans in previous studies testing beat gesture and speech integration (Bosker & Peeters, Reference Bosker and Peeters2021; Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025; Cos et al., Reference Cos, Bujok and Bosker2024; Maran & Bosker, Reference Maran and Bosker2024; Rohrer et al., Reference Rohrer, Bujok, Van Maastricht and Bosker2024). Additionally, the fact that the employed avatar did not make any lip movements might in principle have reduced the extent to which participants considered it to be the source of speech, possibly attenuating audiovisual effects. However, as discussed in the “Methods” section, it is likely that participants still interpreted the avatar as the speaker due to the instructions received and the lack of any potential alternative speaker in the videos. Another potential factor that might have further motivated participants to consider the avatar as the speaker is the temporal relationship between the produced beat gestures and speech (i.e., beat gestures fell on either the first or second syllable; beat gestures were never produced before the word onset or after the word offset). In fact, the observed effects of beat gesture’s timing on speech perception suggest that participants considered the avatar as the source of speech. Still, the lack of lip movements might have made participants consider the visual information of our study less reliable than in previous ones, allowing additional factors to bias the decisional process (e.g., internal models of frequency of occurrence). This speaks to accounts positing that, in audiovisual settings, the quality of information received (e.g., auditory or visual) modulates the extent to which participants rely on it in audiovisual perception (J. E. Stacey et al., Reference Stacey, Howard, Mitra and Stacey2020), extending these accounts to include internal linguistic knowledge of the listener. Future studies comparing audiovisual integration elicited by human and avatar’s beat gestures, or by more and less naturalistic avatars (e.g., in terms of smoothness of gestures and presence of lip movements), constitute a testing ground for this hypothesis. In particular, it is expected that the more human-like the interlocutor is perceived, the more listeners will rely on visual information in speech perception, hence reducing the extent to which internal heuristics based on frequency of occurrence are weighted in the decisional process.

Before concluding, we would like to discuss four aspects of our study, related to the demographics of the participants tested and the methods employed, which might be further investigated in future studies. First, as introduced in the “Methods” section, our sample was largely composed of female participants. The within-subject nature of our experimental design ensures that potential gender differences in beat gesture-speech integration and vocoded speech perception do not represent a confound. Nonetheless, it is worth considering whether beat gesture and (vocoded) speech integration might be modulated by gender differences. Gender differences appear to moderate audiovisual effects based on the integration of lip movements and speech in middle-aged individuals, but not in young adults of similar age as our sample (Alm & Behne, Reference Alm and Behne2015). To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet investigated whether the integration of beat gestures and speech is modulated by gender differences. Future studies testing samples with more balanced gender ratios and with large age ranges might ensure the generalization of the present results or expand them, revealing potential gender and age differences in the integration of beat gestures and vocoded speech. Second, as discussed above, larger biases on speech perception induced by avatars’ beat gestures might be observed employing more advanced avatars than the one of the present study, especially if the avatars make lip movements. While lip movements produced by human speakers do not bias lexical stress perception (Bujok, Meyer, et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2025), their presence might ultimately contribute to perceiving the visual cues provided by the avatar as a more reliable source of information. At present, this hypothesis awaits further testing, for example via a parametric manipulation of multimodal cue reliability. Furthermore, future studies might employ avatars that produce facial visual cues such as head nods, eye widening, and eyebrow movement, which in human communication can support prosodic processing. Third, due to the “offline” nature of the 2AFC responses, the paradigm here employed cannot indicate which stage of processing was affected by the avatar’s beat gestures (i.e., prosodic perception vs. post-perceptual decision stage). Eye-tracking (Bujok et al., Reference Bujok, Meyer and Bosker2024) and recalibration (Bujok, Peeters, et al., Reference Bujok, Peeters, Meyer and Bosker2025) studies showed that human beat gestures affect speech processing in an online and automatic fashion, but no study has yet tested whether the same applies to avatar gestures. Future studies employing eye-tracking or recalibration paradigms might address potential differences and similarities in the processing stage affected by human and avatar beat gestures. Finally, as discussed in the “Introduction” section, the present work employed minimal pairs in isolation as an experimental tool to test the perception of lexical stress. However, in everyday communication, words are rarely presented in isolation, with the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic context affecting their processing. Instead, they typically occur in rich syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic contexts that themselves affect target word processing. At present, only one behavioral study tested how beat gestures guide spoken word recognition when target words occurred in rich semantic sentential contexts (Bujok et al., Reference Bujok, Maran, Meyer and Bosker2025), showing that lexical access was faster when beat gestures accompanied a target word (for related EEG findings, see Wang & Chu, Reference Wang and Chu2013). However, this behavioral study did not observe greater facilitation for beat gestures that were aligned to stressed syllables, compared to beat gestures falling on unstressed syllables. Future studies might also examine if CI users benefit not only from the presence of a beat gesture but also from its congruency with the lexical stress of words in sentential context. As shown by a previous study (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022), CI users still make use of the F0 information they can receive through CIs. In light of the temporal relationship that beat gestures have with F0 peaks (Leonard & Cummins, Reference Leonard and Cummins2011), beat gestures might reinforce the bias in lexical stress perception induced by F0, possibly speeding up lexical recognition in CI users.

That being said, the present study is the first to show that the manual McGurk effect can be observed when employing an avatar. The manual McGurk effect might rely on perceiving the gesture as coming from a human or a human-like interlocutor, since the movement of an isolated pointing hand does not affect lexical stress perception (Jesse & Mitterer, Reference Jesse and Mitterer2011). This observation might be grounded on the existence of neural circuits dedicated to audiovisual integration for speech and movements produced specifically by a human-like agent (Biau et al., Reference Biau, Morís Fernández, Holle, Avila and Soto-Faraco2016; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Latinus, Charest, Crabbe and Belin2014). The possibility of biasing lexical stress perception with avatars, together with the larger accessibility of avatar technology, might lay the foundations for the development of technology (e.g., smartphone apps with avatars moving to the speech prosody) that can be widely used to assist speech perception, both in altered (e.g., apps that support speech perception of audio-only content for CI users) and normal hearing (e.g., avatars providing visual cues when learning how words are stressed in a different language).

Conclusions

The present study showed for the first time that beat gestures produced by an avatar affect lexical stress perception when individuals with normal hearing listen to vocoded speech, which mimics the reduced availability of F0 cues that characterizes CI-mediated speech. The bias induced by beat gestures was particularly pronounced when listening to vocoded ambiguous and less frequent stress patterns in Dutch, suggesting that the quality of the speech signal, visual cues, and internal models of frequency distribution might jointly affect lexical stress perception. The analysis of response times suggests that, when individuals were presented with an ambiguous stress pattern degraded by vocoding, they exploited internal heuristics based on the frequency of stress patterns in their language.

Overall, the fact that an avatar’s beat gestures bias lexical stress perception of vocoded speech lays the foundation for future applications of the avatar’s technology to support speech perception in CI users. In fact, avatars’ beat gestures might represent another example of a (visual) cue that CI users may exploit for lexical stress perception to a larger extent than individuals with normal hearing, similarly to other speech features (Fleming & Winn, Reference Fleming and Winn2022). While simulating certain aspects of CI-mediated input, as previously discussed, vocoding speech is not equivalent to hearing through a CI. Accordingly, future studies testing the effect of gesturing avatars on speech perception with CI users represent an essential step for the application of avatar-mediated multimodal technology in speech perception.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716425100180.

Funding Statement

Funded by an ERC Starting Grant (HearingHands, 101040276) from the European Union awarded to Hans Rutger Bosker. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Open access funding provided by Radboud University Nijmegen.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Data accessibility statement

The anonymized experimental data and analysis code of this study are publicly available at (https://doi.org/10.34973/fr6d-c702), under a CC BY 4.0 license. The stimuli here employed cannot be sublicensed, due to the latest Terms of Use of Deepmotion (https://www.deepmotion.com/), published on March 30, 2025. Requests to access the video materials employed here can be made to the authors of the present work and will be evaluated solely with regard to the latest Terms of Use of Deepmotion. In other words, the authors do not impose any additional restriction to access to the video materials beyond their compliance with the latest Terms of Use of Deepmotion.

Author contributions

Matteo Maran: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision. Renske M. J. Uilenreef: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing. Roos Rossen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing. Hans Rutger Bosker: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition. Renske M. J. Uilenreef and Roos Rossen contributed equally to the present work and share the second-author position.