Introduction

Numerous scholars from multiple disciplines have investigated the effects of globalization on social and political processes. As states face new challenges due to border-crossing markets, immigration and pandemics, individuals’ self-determination is shifting, especially vis-à-vis the traditional communal belonging to the nation-state as the primary source of identity (Jung, Reference Jung2008). Some have suggested that globalization has, to some extent, contributed to cultural homogenization, particularly in the Western world, leading to the dominance of consumerism and neoliberalism as widespread cultural norms. As transnational similarities align into a ‘cosmopolitan culture’ that often transcends national communalities (Brysk & Shafir, Reference Brysk and Shafir2004; Marden, Reference Marden1997), there is a growing sense of frustration among individuals who long for diversity in cultural ideas and ways of life. Indeed, while people enjoy the benefits of globalization, encompassing economic and cultural facets such as the ease with which they can travel and communicate, purchase goods online and watch live sports events or concerts from a different continent, they may also desire some kind of particular identity that distinguishes them and makes them feel that they are nevertheless unique (Bell & de Shalit, Reference Bell and de Shalit2011, Reference Bell and de Shalit2022). Therefore, with the ability of states to serve as a source of particular identity curtailed by global political-cultural values, there is a growing demand for an alternative, or at least additional, self-identity that connects individuals to the unique manifestations rooted in their surrounding local community (Scholte, Reference Scholte2017; Touraine, Reference Touraine1984). In this situation, some cities can become significant sources of identities. This is particularly noteworthy in the case of globalized cities, which function beyond ‘the local’. Instead, they ‘have become actors meaningfully contribute to shaping what we imagine “the global” to be’ (Aust & Nijman, Reference Aust and Nijman2021, p. 1). The ‘globalism’ of cities is thus manifest in their position as centers of vital political, economic and innovative activity that reconfigure the social order (Sassen, Reference Sassen1991, Reference Sassen2007). By using the term ‘globalized’ cities, we particularly refer to the extent of the city's ‘global connectivity’ (Derudder & Taylor, Reference Derudder and Taylor2016; Taylor, Reference Taylor, LeGates and Stout2020) as one of the key manifestations of globalism (Brenner & Keil, Reference Brenner and Keil2006). This accords with Sassen's (Reference Sassen1991) classic conceptualization of the global city's formation as a central productive site. The concept of global connectivity mainly encompasses social and economic aspects of global integration (Friedmann & Wolff, Reference Friedmann and Wolff1982, pp. 310−11; Sun, Reference Sun2008), but it is also associated with elements of culture and identity (Robertson & Buhari-Gulmez, Reference Robertson and Buhari‐Gulmez2017). Therefore, in this study globalism describes the city's global presence by emphasizing the networks that establish its power, for example by constructing Transnational Municipal Networks (Kern & Bulkeley, Reference Kern and Bulkeley2009) that bypass the nation-state and challenge its traditional authority (Curtis, Reference Curtis2016; Friedmann, Reference Friedmann2002).Footnote 1 As Parag Khanna (Reference Khanna2010) asserted in a somewhat prophetic manner, the 21st century will be dominated neither by the Unites States (US) nor by China but rather by cities. Indeed, functional geography and functional infrastructure are becoming more important than political borders, and geopolitical competition concerns connectivity rather than borders and territories.

The emergence of cities as actors addressing global challenges is not new. Over the last two decades, cities have increasingly become powerful, pragmatic and innovative bodies that succeed in implementing local solutions to international issues, confronting challenges that have been addressed poorly on the state level (Acuto, Reference Acuto2013; Aust, Reference Aust2015; Barber, Reference Barber2013; de Shalit, Reference de Shalit2018). This does not suggest that cities have complete autonomy to enact any policy they choose independently, nor does it imply that cities’ global networks inherently diminish the territorial power of states (Brenner, Reference Brenner1998). Nevertheless, cities can attain a degree of autonomy to champion issues they prioritize (Barak & Mualam, Reference Barak and Mualam2022), openly demonstrating their shared values and aspirations and collectively adhering to them. For example, in September 2020, European cities such as Palermo in Italy and Barcelona in Spain challenged their national governments, announcing they would unconditionally host refugees from North Africa.Footnote 2 Another example is the gap between London residents and the rest of the United Kingdom (UK) in the 2016 UK European Union membership referendum (Brexit).Footnote 3 Naturally, this process is highly evident in cities endowed with substantial legal authorities, economic power and global connectivity, as exemplified by some cities in the US. One example is San Francisco issuing licenses for same-sex marriages in 2004, long before the issuing of such licenses was approved by the US Supreme Court; similarly, in response to Trump's immigration policy, cities in the US declared themselves ‘sanctuary cities’, asserting that they would not cooperate with the federal government's efforts to treat undocumented immigrants with greater stringency and enforce immigration laws (Baumgärtel & Oomen, Reference Baumgärtel and Oomen2019). It has been suggested that when individuals associate their city with distinguishable and relatable images of particular notions, they may define their self-identity in relation to the city (Cheshmehzangi, Reference Cheshmehzangi2015; Watson & Bentley, Reference Watson and Bentley2007, p. 6). This applies in particular when the city espouses a particular ethos – a shared way of life that informs the thinking and judgements of the city's inhabitants and distinguishes them from other cities (Bell & de Shalit, Reference Bell and de Shalit2011). Although globalized cities share a similar notion of modernization, diversity and liberalism (Sassen, Reference Sassen2007), they can construct their character and collective identity around particular values that highlight their distinctiveness and relative independence vis-à-vis the state and challenge its traditional national values. These processes raise the question of whether the degree to which the city is globalized is associated with the likelihood that city-zens will foster an urban identity. More specifically, does this urban identity challenge or even replace the national identity?

To answer these questions, we first outline a theoretical framework concerning the shifts in the saliency of states and cities in individuals’ self-identity due to globalization processes and the different degrees to which cities follow this trend. Subsequently, we expose these ideas to empirical scrutiny, utilizing a large-scale original survey conducted in 2022 in six European cities characterized by different degrees of globalism: Paris and Madrid (Alpha), Barcelona and Berlin (Beta), Utrecht and Glasgow (Gamma).Footnote 4 We hypothesize and demonstrate that (1) the city's level of globalism is positively associated with city-zens’ decision to express their self-identity in urban terms (2) rather than in national terms.

We conclude by arguing that urban identity can be considered a possible alternative to national identity, particularly in the context of the globalized city. While this constitutes only a fragment of a broad and intricate mechanism of urban identity formation, the findings establish the tension between urban and national identity and the potential complexity that besets the coexistence of these two identities in the globalized world.

Urban and national identities in global cities

The concept of urban identityFootnote 5 is rooted in the notion of ‘place’ as a set of experiences and meanings attached to a physical dimension (Cresswell, Reference Cresswell2014; Hubbard & Kitchin, Reference Hubbard and Kitchin2010; Proshansky et al., 2014, [Reference Proshansky, Fabian, Kaminoff, Gieseking, Mangold, Katz, Low and Saegert1983]; Yi Fu, 2001, [Reference Yi Fu1974]). When individuals define their identities as a ‘Berliner’, ‘Merseysider’, ‘Milanese’ or ‘Porteños’ (meaning people of the port, as citizens of Buenos Aires call themselves), they attribute meanings and connotations to the city. These are constructed by both abstract, intangible elements of that urban space – such as history, culture and literature – and physical features of architecture, monuments and buildings that distinguish it from other places (Buttimer & Seamon, Reference Buttimer and Seamon2015; de Shalit, Reference de Shalit2019; Okaty, Reference Okaty2002; Solesbury, Reference Solesbury2021). Such subjective interpretations create one's place-identity (Löw, Reference Löw2013), which can be defined as a process via which, through interaction with a place, people describe themselves in terms of belonging to that specific place (Stedman, Reference Stedman2002). In this process, cities reflect and shape their inhabitants’ personal and collective values and outlooks in various ways: from the design and architecture of their buildings (Evans, Reference Evans2011), or alternatively when their architecture has an indirect effect on values via mood change when one strolls through the city (de Botton, Reference de Botton2006; Landry, Reference Landry2008), through public monuments marking significant episodes or dates, and, most notably, regulations and policies. For example, in 2016 the city of Copenhagen, where 40 per cent of the population was already commuting by bicycle, changed its traffic lights system to recognize cyclists and favour them over cars (Davies, Reference Davies2016). It made bike riding more efficient than driving and, as expected, encouraged more people to abandon their cars and ride bikes, in turn changing the city's atmosphere, making people feel it was greener and more environmentally friendly than ever.

D. A. Bell and de Shalit (Reference Bell and de Shalit2011, Reference Bell and de Shalit2012) refer to these shared ways of life that inform the thinking and judgements of the city's inhabitants as cities’ ‘ethoses’. The city's ethos does more than shape one's urban identity. Indeed ‒ as an idea that distinguishes a particular city from other cities ‒ it allows city-zens to take pride in the distinctiveness of their city, conceptualized by Bell and de Shalit (Reference Bell and de Shalit2011) as ‘civicism’. This concept embodies one's association and self-identification with the city and the ethos it sustains, or, as framed by Löw (Reference Löw2012; Berking & Löw, Reference Berking and Löw2008), the unique intrinsic logic of the city. More importantly, it differentiates urban pride from national pride (i.e., ‘patriotism’), because the nation-state has long constituted the primary source of communal belonging and political identification. Urban identities are often defined in comparison to other cities: Rome versus Milan, Berlin versus Munich, Beijing versus Shanghai. However, unlike the enmity between states and nations, rivalry between cities often involves a much lighter attitude, frequently combined with a wink. This was vividly demonstrated in the US: When Rahm Emanuel was Chicago's mayor, he took pride in the city's public transport system. In an op-ed for the NY Times, he argued that Chicago's system was extremely popular (gaining 85 per cent approval from Chicago's city-zens), explaining that this was due to the city's ongoing ethos regarding mayors who are directly accountable for service and the city's prioritizations. He added a few sarcastic remarks about New York's subway. The New York based Daily News did not remain silent. Referring to the ‘Murder capital mayor’, its headlines announced: ‘Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel takes cheap shot at NYC subways, but at least Big Apple's not as dangerous’.Footnote 6

Considering that cities form their ethoses based on their unique attributes, the case of globalized cities is fascinating because they embody the tension between the global and the local. Although this (seeming) contradiction is arguably an inextricable component of globalization (Marden, Reference Marden1997; Oomen, Reference Oomen, Buikema, Buyse and Robben2019, p. 129), the position of cities in this process should be understood within its context. On the one hand, a city that waves the flag of globality aligns with the notion of border-crossing similarity, thereby losing its distinctiveness. On the other hand, globalized cities can be a source of an alternative ‒ or additional ‒ identity to national-identity because they distinguish themselves from other cities in the country, for example, in promoting semi-autonomous foreign policy as independent actors in the international arena (Gordon & Ljungkvist, Reference Gordon and Ljungkvist2022; Ljungkvist, Reference Ljungkvist and Curtis2014), thereby advancing their own unique, often liberal ethos. Thus, if city-zens of globalized cities feel less attachment to national values, they may tend not to define their identities along national lines and yet feel that they desire a more particular identity than a global (detached) one. The globalized city could be the source of this identity, embodying both local and global manifestations. This ‘glocal’ dynamic – whether referred to as a process of diffusion (Robertson, Reference Robertson1992), a hybrid merge (Ritzer, Reference Ritzer2003) or a symbiotic mechanism (Roudometof, Reference Roudometof2016) of global and local movements ‒ is particularly evident in globalized cities’ ability to modify global standards to local circumstances and needs (Barber, Reference Barber2013; Jenks, Reference Jenks2012). If globalization is in fact glocalization (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw2004), then globalized cities embody this process and translate it into cultural and identitarian manifestations.

In that respect, globalized cities are a platform for developing a more complex urban identity that is inclusive, universal and flexible but also more local, place-based and rooted in the particular character, or ethos, of the city. This ethos, which often evolves from modern, liberal values shared by global cities (Sassen, Reference Sassen2007), can manifest in local initiatives that further shape the city's spirit. For example, the proliferation of LGBTI movements in urban spaces (Ayoub & Kollman, Reference Ayoub and Kollman2021), the promotion of human rights in Barcelona (Berends et al., Reference Berends, Hamaker, Hoff, Goossens, Hadtstein and Van Gerven2013; Grigolo, Reference Grigolo2010, Reference Grigolo2019), multiculturalism in Montreal (Picco, Reference Picco2008) and the age-friendly city approach in Madrid (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson, Rémillard‐Boilard, Gu and Dupre2019). These developments presuppose the liberal inclinations of residents in large, globalized cities, who tend to be more educated and politically aware (Henriques, Reference Henriques2023; Rangarajan & Rahm, Reference Rangarajan and Rahm2011).

To thoroughly capture the mechanisms of identity formation regarding the globalized city's collective ethos, we borrow Frug's (Reference Frug, Rodwin and Hollister1985) distinction between thinking of the city as a social entity and conceptualizing it as a legal entity. The social aspect is associated with both global and local dimensions of the globalized city, while other cities (i.e., less globalized) could be conceived in more legal terms, as part of the nation-state. The social aspect is associated with both global and local dimensions of the globalized city, in contrast to other cities (i.e., less globalized), which might be perceived more in legal terms as integral to the nation-state.

When we consider the city as a social concept, we think of it as diminishing national bonds because this highlights the city as a public, participatory local domain (Frug, Reference Frug, Rodwin and Hollister1985, p. 1,068) wherein individuals can collectively shape the city's distinct ethos, which constitutes their urban identity. Globalized cities ‒ characterized by international ties, exposure to global political discourse, tourism and transnational migration (Amen et al., Reference Amen, Archer and Bosnian2008; Nagel, Reference Nagel2005; Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Derudder, Timberlake and Witlox2015) ‒ serve as fertile ground for fostering this social perception. Due to the multi-national diversity of globalized cities, alongside the overall variation in backgrounds, occupations and business connections, their inhabitants may develop a stronger sense of attachment to their close urban community ‒ which is also inherently global ‒ rather than to the nation-state. Therefore, globalized cities are easier to identify with because they display a degree of independence vis-à-vis the state (Ross & Trachte, Reference Ross and Trachte1990), allowing them to foster social activity that reflects the city's unique (glocal) ethos. At the same time, when we think of the city as a legal entity, we cannot avoid the nation-state; indeed, the city depends on the state to legitimize its regulatory authority and its power to tax. Although recently a substantial number of cities have challenged this system, as well as many particular laws and policies issued by the state that enable cities to regulate various subfields, the city still derives its power and authority from the state, making it harder to develop a unique urban identity and pride concerning the city.

In highly globalized cities (Alpha rank in the GaWC Index [Taylor, Reference Taylor, LeGates and Stout2020]), namely cities with a high level of cosmopolitan ties, the social overrides the legal: the social ties and the social atmosphere are so influential that the legal vulnerability of the city vis-à-vis the state fades away, so to speak, or becomes much less present in the minds of the city dwellers. By contrast, when the city is less cosmopolitan, people are more aware of their city's legal ties to the state. Hence, they assimilate the sub-state character of local governments (Nijman, Reference Nijman2016), as though the city constitutes a legal extension or an organ (Aust, Reference Aust2015) of the state, instead of an autonomous authority that can express and promote distinctive values manifesting through urban identity.

Therefore, our hypotheses are:

H1: A higher level of globalism in the city increases the likelihood that city-zens will define themselves in urban terms.

Just as urban identity emerges as a viable alternative or evolves into a somewhat tense relationship with national identity, we likewise hypothesize that the decision of city-zens in globalized cities to define themselves in urban terms may potentially come at the expense of their national identity. This hypothesis primarily pertains to the process of prioritizing identity from the repertoire of identities ‒ a set of multiple personal identities that individuals possess simultaneously. This is a flexible, fluid, chosen set that can change circumstantially (Lawler, Reference Lawler1992; Lustick et al., Reference Lustick, Miodownik and Eidelson2004).

In accordance, we emphasize that while we anticipate some degree of interchangeability between urban and national identities within individuals’ repertoire of identities, we do not assert that individuals who express a particular identity at a given moment completely forsake the other. Just as the rise of cities does not necessarily mean the decline of states (Brenner, Reference Brenner1998, Reference Brenner1999; Curtis, Reference Curtis2016), prioritizing and highlighting urban identity does not automatically imply the absolute loss of a national sentiment, and vice versa. City-zens can possess both identities at the same time, but they can emphasize or think more dominantly about one of them in a given moment, during a particular period in their lives, or under specific circumstances and in certain contexts and places (Marston, Reference Marston2002). Therefore, the argument posits that the potential tension between urban and national identities can incentivize city residents to prioritize and emphasize the prevalence of one identity over the other within their identities’ repertoire, without necessarily completely abandoning the latter. More precisely, we expect that city-zens who do not choose national identity as part of their repertoire will be more affected by the glocal context of globalized cities. Put more formally:

H2: The higher the level of the city's globalism, the greater the likelihood that its city-zens will define themselves in urban terms, especially among those whose identities’ repertoire does not contain a national identity.

Method

The analysis herein is based on an online survey that we conducted in January and February 2022 in six European cities: Paris, Madrid, Berlin, Barcelona, Utrecht and Glasgow (N = 2,900; ns between 500 and 400). Cities were chosen for the sample to represent similar cultural and spatial West-European conditions but also different degrees of globalism, according to the GaWC Index (Taylor, Reference Taylor, LeGates and Stout2020).Footnote 7 The latter defines and ranks cities’ level of globalization worldwide based on the prevalence of firms providing ‘advanced producer services’ (APS) in four categories: accountancy, advertising, banking/finance and law. The selection of this measure for the study was grounded in its empirical alignment with the theoretical framework positing the centrality of global cities as sites of both demand for and production of key services (Derudder & Taylor, Reference Derudder and Taylor2016, p. 625). As a widely employed metric for the past two decades, it incorporates a particularly extensive database. This enables us to select precisely the most appropriate cases for the study, aligning with the categories we aim to address – specifically, globality, population diversity and linguistic attributes, as elaborated in the following paragraph.

Based on the GaWC Index, we sampled pairs of cities in three categories representing various levels of globalism (from the highest to the lowest level): Paris and Madrid (‘Alpha’),Footnote 8 Berlin and Barcelona (‘Beta’),Footnote 9 and Utrecht and Glasgow (‘Gamma’).Footnote 10 To be confident that city-zens’ self-definition with regard to urban identity is affected by the level of globality rather than other local circumstances, we took into account three additional distinct attributes of cities: (1) cultural diversity; (2) a unique regional identity (which could be the result of a dominant local-ethnic identity, as in Barcelona and Glasgow); and (3) the stature of cities as capitals of their states and centres of political activity (Paris, Madrid and Berlin).

Cultural diversity constructs a particular ethos in the city (as a multicultural city/contested city) that affects individuals’ self-determination. A culturally heterogeneous city could be associated with a large portion of city-zens who identify themselves with the city rather than the state, which represents the primary national identity. Alternatively, local cultural heterogeneity could also be associated with preferring the state as a source of identity over the city in a search for one unified (national) identity. Local cultural diversity is often entangled with the city's portion of immigrants to the country (and the city) – introducing different ethnicities, backgrounds and norms into the urban fabric – and thus we sampled cities with varying degrees of cultural heterogeneity based on population composition vis-à-vis immigration rates. Specifically, we chose cities with similar population compositions but different degrees of globalism to rule out the explanation that cultural diversity shapes city-zens’ urban identity. In accordance, Madrid (Alpha), Barcelona (Beta) and Glasgow (Gamma) have a similar proportion of foreign-born city-zens (13−17 per cent),Footnote 11 while Paris (Alpha) and Utrecht (Gamma) have similar (higher) proportions of immigrants (21−23 per cent; Berlin has a higher proportion: 30 per cent foreign-born city-zens).Footnote 12

In addition, we sampled two cities in which city-zens are characterized by a rather distinctive identity that falls somewhere between urban and national identities in their typical forms. Barcelona (Beta) has a Catalan community with a solid ethnolinguistic effect that creates multiple identity conditions (Melich, Reference Melich1986, p. 150), embodied in a non-state form of nationalism that constitutes a unique Catalan, non-Spanish identity. At the Gamma level, we utilized Glasgow, also known for its particular ethnonational identity (i.e., Scottish not British). In addition to the linguistic aspect, Glasgow has a history of autonomy, increasing the likelihood of developing a separate regional identity (Fitjar, Reference Fitjar2010). If there were no differences between cities based on globalization, Barcelona and Glasgow would exhibit similar levels of self-determination in terms of the city (however, as the analysis shows, there are differences between these cities).

To rule out the explanation that embracing an urban identity is just another way of associating with the state when the city is the capital, we included two capital cities from the Alpha level (i.e., Paris and Madrid) and one city from the Beta level (i.e., Berlin). All three additional aspects ‒ cultural diversity, regional identity and capital cities ‒ should enable us to control for competing explanations regarding cities’ levels of globalism.

Within cities, respondents were sampled via a random sampling test, including quotas of age, gender and education, to guarantee representation along these lines.Footnote 13 The survey, consisting of over 50 questions concerning local political participation, self-identity and personal preferences and attributes, was available in five languages: English, Spanish, Catalan, French and Dutch.

Measures

The dependent variable is urban identity, a dummy variable coded 1 for city-zens who defined themselves with reference to the city and 0 if urban-related identity was not mentioned. The variable is based on an open question: ‘Besides being a resident of [country name], please write the name of a specific group to which you feel that you belong first and foremost’.Footnote 14 Respondents could describe themselves using several self-identities, in line with the premise that the “self” has multiple dimensions of identities (Jones & McEwen, Reference Jones and McEwen2000). The answers were initially classified into 27 broad categories and then narrowed down to 14 categories.Footnote 15 All the identities mentioned by a respondent were given equal weight in the coding process,Footnote 16 regardless of the order in which they were mentioned (for example, national, ethnic or socio-economic-related identities that a respondent mentioned were granted 1 point each in the classification into categories). Urban identity is thus one identity among a set of 14 identities; indeed, respondents who defined themselves with regard to the city could have other additional identities (for example, national identity, which is one of the independent variables, detailed below). In total, 9.1 per centFootnote 17 of the respondents defined themselves with reference to the city (the distribution of urban identity across cities is displayed in the results section).

There are two independent variables at the heart of the analysis. Globalism is based on the GaWC ranking of cities’ levels of globalism (Taylor, Reference Taylor, LeGates and Stout2020). Therefore, we created an ordinal variable with three categories, from the lowest to the highest level of globalism: Gamma (Utrecht and Glasgow, 31 per cent of respondents), Beta (Berlin and Barcelona, 34.5 per cent of respondents), and Alpha (Paris and Madrid, 34.5 per cent of respondents) (M = 1.03, SD = 0.8). This variable is constructed as an ordinal scale variable to focus on distinctions between types of cities’ globalism rather than the numeric ranking of individual cities.

National identity is based on the same open question as the dependent variable: Urban identity, asking respondents to name a group to which they feel they belong (more than one answer is allowed). We created a dummy variable coded 1 for respondents’ self-definition with reference to the nation, and 0 if none of the identities mentioned was nation-related. The nationality category includes references to the nation within which the city lies (Berlin – Germany, Madrid and Barcelona – Spain, Glasgow – Great Britain); otherwise, it is coded as ethnicity (country of origin). The distribution of the variable shows that 21.7 per cent of respondents mentioned the nation as (one of) their group affiliations.

Control variables: additional factors that may be associated with city-zens’ urban identity were taken into account.

Identity repertoire is a variable measuring the number of identities by which a respondent chooses to define herself. The wider the respondent's repertoire is, the more likely it is that one of the identities will be associated with the city. By controlling for this variable, we can be more confident that the correlation between urban and national identity is significant regardless of the number of identities included in the respondent repertoire. Respondents used up to six different groups, and thus the variable ranges from 0 (in case of no answer) to 6, with a majority of 82.9 per cent of respondents choosing only one identity (M = 1.09; SD = 0.52).

Length of residence is a dummy variable coded 1 when respondents had resided in the city for more than 10 years and 0 if less. The length of residence is a common predictor of the formation of self-determination associated with the urban space ‒ that is, developing place attachment (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Gottfredson and Brower1984) and a sense of place (de Shalit, Reference de Shalit2019). Although studies do not indicate a minimum time necessary to develop a bond with places (Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, Hidalgo, Salazar‐Laplace and Hess2007, p. 318), the 10-year cut-off point was used in this study because this is a sufficiently long period of one's life ‒ which would rarely be considered temporary by both young and older individuals ‒ to create memories, experiences and meanings that construct place-identity. In addition, the respondents who were born in the city have lived in it for at least 10 years (the participants’ minimum age is 18). Accordingly, the groups are often parallel, hence they were united and defined as a threshold.Footnote 18 Among the respondents, 73 per cent had lived in the city for more than 10 years.

A few socioeconomic variables were incorporated into the model. Age group is an open-question variable recoded into four categories reflecting the main phases in life: young adults (18–29); adults (30–45); mid-life adults (45–65); elderly (66–88). Age is a factor that manifests the flexibility of self-identity, which develops and changes during the decades of adult life, especially in modern societies (Côté & Levine, Reference Côté and Levine2002; Jung, Reference Jung2008). As such, age could be associated with urban identity in two opposing directions. Negatively – the younger generation gradually neglects the group-dependent and communal political identity that both the city and the state represent, while the older generation might be more connected to the physical urban space and the political authority that manages it (Persiko, Reference Persiko2022). By contrast, age could be positively associated with urban identity if younger city-zens feel that the city is a space advocating the notions of freedom, globalization and liberalism (especially global cities), while the older generation might identify more with traditional national belonging. The distribution of the variables indicates that the most frequent age group in the sample is mid-life adults (35 per cent), closely followed by adults (34 per cent), whereas the elderly group is the minority in the sample (13 per cent) (M = 2.41, SD = 0.93; non-scaled age: M = 45.26, SD = 15.7). Income is a dummy variable coded 1 for ‘high income’ and 0 for ‘low income’ based on respondents’ subjective evaluation on a four-point scale (1 = ‘Living comfortably on present income’; 4 = ‘Finding it very difficult on present income’). Income can be positively associated with urban identity because the city is an alternative source of identification to the traditional notion of the state, which is often criticized by higher classes who have the time and intellectual capacity to peruse democratic, liberal values (Welzel & Ingelhart, Reference Welzel, Ingelhart and Caramani2011). After splitting the original scale into two equal categories, 71 per cent of respondents reported a high income, while 29 per cent have a low income. Education is a dummy variable coded 1 for higher education (secondary and above, 84 per cent of responses) and 0 for lower education (below secondary, 16 per cent). Like Income, it could be positively associated with the higher class looking for another source of identification in a globalized era. Gender is a dummy variable coded 1 for female respondents and 0 for men (58 and 42 per cent, respectively). City name is a categorical variable used as the grouping variable in the multilevel model.

Results

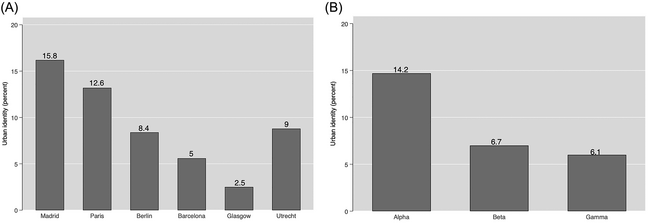

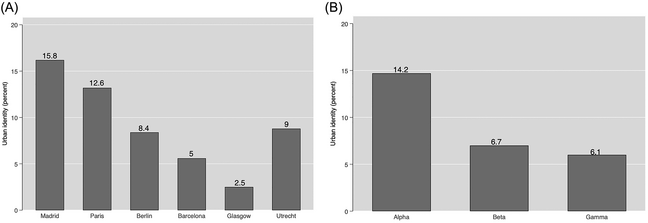

We begin with two descriptive statistics that demonstrate the distribution of city-zens who define themselves as having an urban identity in each city (Figure 1A) and by cities’ level of globalism (Figure 1B). The evidence suggests that cities with higher levels of globalism have higher portions of city-zens who embrace an urban identity. Although the city of Utrecht has a relatively high percentage of city-zens who define themselves with reference to the city (compared with the other Gamma-city, Glasgow), the general trend is pretty consistent, providing initial support for H1 regarding the positive connection between urban identity and the city's level of globalism.

Figure 1. (A) Percentage of urban identity across six cities. (B) Percentage of urban identity by degrees of cities’ globalism.

To thoroughly test the two hypotheses, we conducted three multilevel logistic regression models that account for cities’ clustering effect, enabling us to estimate individuals nested within cities. The grouping variable in the three models is City name,Footnote 19 when at least some of the variances in city-zens’ likelihood to define themselves with reference to the city are attributed to the differences between cities.Footnote 20 All the models include control fixed effects: identity repertoire, length of residence, age group, income, education and gender.Footnote 21

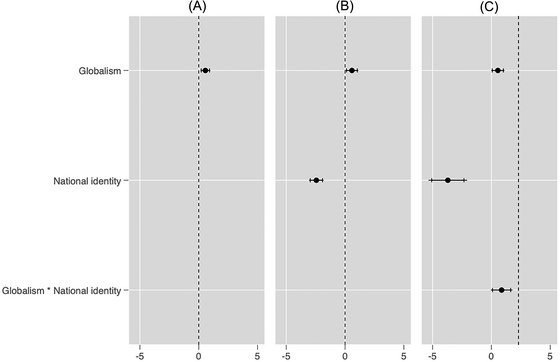

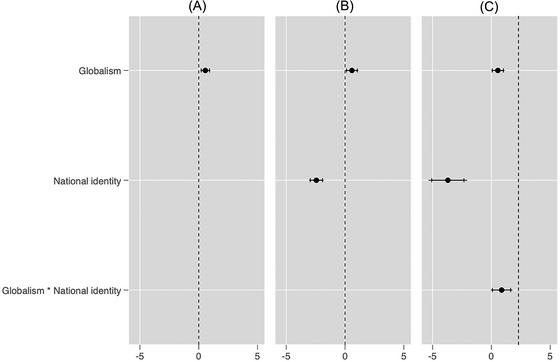

Figure 2 displays the three stages of the analysis via three models.Footnote 22 Model 2.0 tests the correlation between the dependent variable Urban identity and the city's level of globalism. The results confirm H1, indicating that urban identity is positively associated with the city's level of globalism.

Figure 2. Multilevel analysis (A) Correlation of urban identity with globalism; (B) Correlation of urban identity with globalism and national identity; (C) Interaction model: Correlation of urban identity with national identity, by globalism degrees.

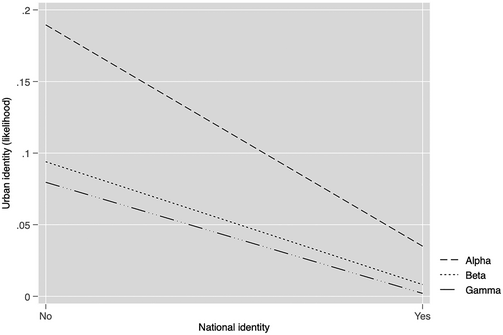

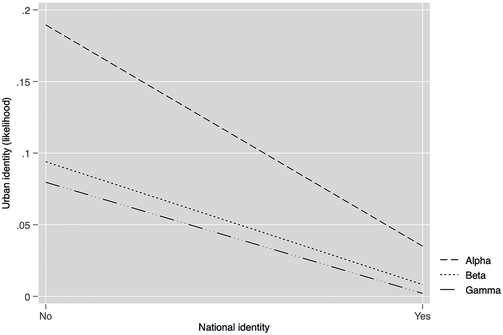

Model 2.1 builds on Model 2.0 by adding the independent variable National identity. This is a preliminary step for testing H2 – according to which city-zens who do not define themselves with reference to the nation are more prone to embrace an urban identity, especially in globalized cities. Model 2.1 indicates that urban identity correlates negatively with national identity, indicating a tension between these two identities.Footnote 23 To confirm that this prioritization of urban identity over national identity is indeed associated with the city's level of globalism, we added an interaction term (i.e., multiplication) of Globalism and National identity, in which the city's level of globalism moderates the effect of national identity (Model 2.2). Model 2.2 displays a significant and negative interaction between these two main effects, along with the control fixed effects, confirming a negative correlation between city-zens in globalized cities who define themselves with reference to the city and those who define themselves with reference to the nation. Figure 3 unpacks the interaction term into its categories, displaying a much more prominent negative connection between urban and national identity in Alpha cities (90 per cent confidence), compared with Beta and Gamma cities.

Figure 3. Correlation of urban and national identities by three levels of globalism.

These multilevel logistic regression models were conducted on Stata 17 and use the dummy variable Urban identity as the dependent variable. The grouping variable is City name. The models are controlled for identity repertoire, length of residence, age group, income, education and gender. Confidence intervals = 0.05.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper offers a framework for understanding individuals’ preferences in expressing their self-identity in globalized cities. The empirical results support the two hypotheses scrutinized, demonstrating a consistent trend of prioritizing urban identity over national identity in highly globalized cities (Alpha), compared to Beta and Gamma cities.

The examination of findings relating to H1 indicates that the city's level of globalism is a catalyst promoting the likelihood that city-zens will foster an urban identity. For example, city-zens of Madrid and Paris are more prone to nurture an urban identity than people in Barcelona and Berlin, and the latter are more likely to do so than the city-zens of Utrecht and Glasgow. However, while the study establishes this connection empirically, it cannot capture the complex mechanism of urban identity formation in those cities. We suggest that this lacuna could be theoretically addressed by the duality of the global city ‒ its association with global and local attributes. We borrow the notion of ‘glocality’ (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw, Dunford and Kafkalas1992) to illuminate this global-local dynamic.

The empirical results allow as to apply this concept more confidently to the discourse of identity formation and suggest that the globalized city could provide a compromise for those who wish to have a universal, border-crossing identity on the one hand, yet on the other preserve an attachment to their local environment, which they consider constitutive of their ‘selves’ (Cheshmehzangi, Reference Cheshmehzangi2015, p. 402). This explanation is particularly strengthened by the analysis of H2, showing a negative correlation between urban and national identities, especially in highly globalized cities. As city-zens often refrain from expressing national identity to prioritize urban identity, it seems more plausible that the latter ‒ when embraced in globalized cities ‒ constitutes an alternative for those not interested in associating themselves with the nation (temporarily or partially). In this regard, it is important to note, again, that despite the negative correlation between urban and national identities found in this study ‒ which could be referred to as a trade-off ‒ one should not conclude that the two identities cannot prevail at the same time. City-zens who define themselves by mentioning one or two identities at a particular moment do not necessarily lack other sources of identification. This is a dynamic process; indeed, the fluidity of personal identity means that it can change during a lifetime even without being influenced by external occurrences (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2009). The results could suggest tension or conflict between urban and national identities, at least for specific episodes in a person's life. In line with Frug's (Reference Frug, Rodwin and Hollister1985) distinction between the social and legal notions of the city, we can argue more confidently that the allure of the globalized city as a source of identity lies in its capacity to nurture social aspects. This is achieved by providing prospective bonds with other people worldwide, by crossing the nation-state's legal, economic and political borders, and by emphasizing shared world history (Booth, Reference Booth1991, p. 542).

The study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgement and consideration in future research. Its main weakness lies in its inability to unpack the process of city-zens’ identity formation. As any statistical analysis, it is limited to observing probabilistic connections, not causal mechanisms or social constructions. While we assert that the positive correlation between the city's level of globalism and urban identity is explained by the unique glocal ethos that globalized cities nurture, alternative theoretical interpretations of the empirical results should not be dismissed. A reversed theoretical mechanism suggests that the tendency for urban identification prevalent in diverse cities ‒ that is, globalized cities ‒ (Colic-Peisker, Reference Colic‐Peisker2014; Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Derudder, Timberlake and Witlox2015; Sassen, Reference Sassen1991) accelerates these cities’ global connectivity, political influence and cultural centrality. However, this hypothesis falls outside the scope of this study; it cannot account for the causal mechanism behind the empirical connection.

While one could view the study's exclusive focus on European cities as a limitation, it is important to note that the relatively similar characteristics of European cities allow us to mitigate cultural differences and exert more precise control over alternative explanations. Although we recognize that this case-selection inevitably overlooks other social, cultural and geopolitical circumstances that future research should address, we suggest that this study's results should be interpreted within their context, considering that they may differ from other cities in accordance with each city's unique local, social, cultural and historical circumstances.

The contextual interpretation of the results is also crucial at the individual level, given that personal characteristics influence self-identification (Antonsich & Holland, Reference Antonsich and Holland2014). However, our examination did not consistently reveal associations between the examined connection and city-zens’ attributes, including gender, age, income or others. This lack of consistency may be attributed to limitations in the diversity of our sample. Considering these constraints, which limit our capacity to control for all alternative explanations, we acknowledge that the results could have differed under other conditions. For instance, personal satisfaction with life (Węziak-Białowolska, Reference Węziak‐Białowolska2016) may influence identity prioritization, or conducting the survey at various times, such as during a war, holiday or COVID-19 lockdowns, could potentially shift individuals’ self-identification in a different direction ‒ more urban or national.

Despite its limitations, this study sheds light on the connection between the urban and the national in the globalized world, as posited in previous studies. For example, evidence from three Asian global cities (Shanghai, Singapore and Hong Kong) indicates some degree of conjunction between the process of constructing cultural capital (aimed at accelerating cities’ global positions) and serving national agendas (Kong, Reference Kong2007). While residents of these cities may take different approaches to assimilating this connection, our results from six European cities indicate that although the global city ethos could be, among other things, associated with nationhood, city-zens not only distinguish between these notions but also prioritize one over the other when it concerns their self-determination.

Moreover, this study's findings can be enriched by exploring theories that adopt a symbiotic approach to the interaction between national and urban levels in the context of globalization. Brenner's (Reference Brenner1998, Reference Brenner1999) concept of re-scaled state configuration proposes that the territorial power of the state undergoes a rearticulation concerning sub- and supra-state scales, rather than being diminished. However, attempts to empirically trace a comparable rescaling of individuals’ territorial identities have yet to yield conclusive results (Antonsich & Holland, Reference Antonsich and Holland2014). This study provides new insights that could illuminate the link between changes in economic-political institutions and shifts in individuals’ identities resulting from globalization. By substantiating the prioritization of individuals' urban over national identity in globalized cities, this study does not diminish the stature of national-related aspects within individuals’ identities’ repertoires. Despite the tension it detects between urban and national identities, it acknowledges the adaptability and co-evolution of individuals’ personal identities in accordance with global occurrences. From this perspective, future research could explore whether, and to what extent, national identity is already integrated into an individual's urban identity. This involves unpacking the process of urban identity formation in globalized cities by asking what city-zens think of when they think of their city. Given the perspective that national identity is an inherent component of global culture (Robertson & Buhari-Gulmez, Reference Robertson and Buhari‐Gulmez2017, p. 14), expressing urban identity in globalized cities may already encompass new configurations of the nation-state in its ‘glocal’ form (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw1996).

Lastly, this study contributes to understanding the societal dimension of globalized cities regarding urban identity formation. In contrast to scholars’ pessimistic projections concerning the unravelling of global cities because they are ‘deeply divided and polarized in ways that threaten the integrity of the urban fabric’ (Curtis, Reference Curtis2018, p. 3), we show that city-zens of these cities, more than others, tend to define themselves in urban terms, that is, emphasizing their connection to the urban community. Globalism, even with the capital structure it entails, and in the shadow of today's populist atmosphere, does not necessarily erode the social fabric, nor does it prioritize national sentiment, at least not in the global city.

The tension between the urban and national identities displayed here invites us to explore other political phenomena from an urban perspective. For example, researchers should investigate how these competing identities manifest in states with high political polarization, or how the urban setting can constitute a liminal space between rival groups. It has been demonstrated that the urban sphere fosters local pluralism, leading to greater compassion and consideration of the rights of the ‘other’ at the city level, compared to the level typically observed in states (de Shalit, Reference de Shalit, Baubock and Orgad2020; Lehrs et al., Reference Lehrs, Brenner, Avni and Miodownik2023). The pronounced human diversity and multinationalism within globalized cities can possibly expedite this phenomenon. Especially in regions or states characterized by ethno-national polarization, such as Israel, Northern Ireland, Cyprus and Lebanon, cities that have experienced heightened globalization processes may emerge as a source of identity that transcends divisions prevalent at the national level. This urban identity may signify a more harmonious, peace-seeking communal ethos, resonating with other globalized cities worldwide and extending the tensions between urban and national identities to diverse realms.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Avner de Shalit for his insightful observations on earlier drafts of this manuscript, to Kristof Steyvers for his compelling comments at the ECPR conference (September 2023), and to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. We are thankful for the financial support provided by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant Number: 1183/21), and the Max Kampelman Chair in Democracy and Human Rights.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix