After milking at the farm, milk is stored in a reservoir at low temperatures for up to 48 hours (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Pinto, Riedel and Vanetti2015). The protease and lipase enzymes, which are responsible for the digestion of protein and lipids, are produced by psychrotrophic microbes that develop in this milk. These psychrotrophic bacteria mentioned above had been growing for approximately 2–3 days, before any heat treatment, resulting in the production of small but significant quantities of lipases and proteases (Samaržija et al., Reference Samaržija, Zamberlin and Pogačić2012). The proteases and lipases immediately start to degrade proteins and lipids (Knudsen et al., Reference Knudsen, Lokerse, Pedrotti, Nielsen, Dekker, Rauh, Fogliano and Larsen2024). Even at low levels these proteases break down the proteins of the globular membrane of fat globules present in milk, allowing lipases to access the fat molecules within the globule and to start liberating fatty acids during lipolysis (Miettinen et al., Reference Miettinen, Nyyssölä, Rokka, Kontkanen and Kruus2013; Wiking et al., Reference Wiking, Løkke, Kidmose, Sundekilde, Dalsgaard, Larsen and Feilberg2017).

Ultra-high temperature treatment (UHT) is a method of preserving milk by quickly heating it to very high temperatures of between 135°C and 145°C for 2 to 6 seconds (Prakash et al., Reference Prakash, Kravchuk and Deeth2015). This process results in the complete elimination of psychrotrophic bacteria and any other microbes present in the milk, as well as the inactivation of all the enzymes that might have been secreted; however, minimal levels of fatty acids, resulting from lipid hydrolysis, remain in the milk (Le et al., Reference Le, Datta and Deeth2006; Cappozzo et al., Reference Cappozzo, Koutchma and Barnes2015).

The milk is subsequently packaged (Gaur et al., Reference Gaur, Schalk and Anema2018). This milk is quiescent and devoid of microbial agents, including proteases and lipases; however, it is still subject to age gelation after some time or when subjected to certain conditions (Raynes et al., Reference Raynes, Vincent, Zawadzki, Savin, Mertens, Logan and Williams2018). If the fatty acids in UHT milk are exposed to a low-temperature environment for an extended period, the plasminogen that survived pasteurization may be activated at a high level, resulting in rapid milk decomposition

Plasmin is part of a complex system that includes zymogen plasminogen, plasminogen activators, plasminogen activator inhibitors and plasmin inhibitors. In fresh milk, plasminogen is the predominant form, with concentrations 2–20 times that of plasmin (Richardson and Pearce, Reference Richardson and Pearce1981; Bastian and Brown, Reference Bastian and Brown1996). Inactive plasminogen is activated to plasmin (Gazi et al., Reference Gazi, Vilalva and Huppertz2014) by enzyme plasminogen activators (PAs), which fall into two principal classes. The classes include urokinase-type (u-PA) and tissue-type (t-PA) (Ismail and Nielsen, Reference Ismail and Nielsen2010), which are associated with somatic cells and casein micelles, respectively (Deharveng and Nielsen, Reference Deharveng and Nielsen1991; Lu and Nielsen, Reference Lu and Nielsen1993; Heegaard et al., Reference Heegaard, Rasmussen and Andreasen1994; White et al., Reference White, Zavizion, O'Hare, Gilmore, Guo, Kindstedt and Politis1995). Plasminogen activators are resistant to heat, and processes such as pasteurization do not affect them. However, slight inactivation occurs during high UHT process temperatures (Datta and Deeth, Reference Datta and Deeth2001).

Therefore, any potential plasminogen activation by plasminogen activators could contribute to plasmin activity in milk. Plasmin levels increase in milk during mastitis infection (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Daniel and Coolbear2003) with higher levels of somatic cells than in regular milk. This occurs due to the increase in activity of plasminogen activators and other proteolytic enzymes present within the somatic cells (Bastian and Brown, Reference Bastian and Brown1996). High levels of plasmin, along with increased numbers of somatic cells in mastitis milk, lead to enhanced proteolysis; therefore, mastitis milk is more prone to age gelation than normal milk (Chavan et al., Reference Chavan, Chavan, Khedkar and Jana2011). There is a need to investigate factors that directly affect plasminogen activation (Burbrink and Hayes, Reference Burbrink and Hayes2006; Prado et al., Reference Prado, Ismail, Ramos and Hayes2007). The factors that affect the plasmin system activity are many, thus adding to the complexity of the system.

Processing conditions, namely heating, pH manipulation and storage, can affect the plasmin system in various ways. The plasmin system components interact together (Bastian and Brown, Reference Bastian and Brown1996) and with other components of milk, such as casein (Markus et al., Reference Markus, Hitt, Harvey and Tritsch1993) and whey proteins (Kelly and Foley, Reference Kelly and Foley1997; Enright et al., Reference Enright, Bland, Needs and Kelly1999), promote or inhibit proteolysis, depending on the processing and storage conditions of milk. Furthermore, the proteases produced by psychrotrophic microorganisms, which contribute to casein hydrolysis (Kohlmann et al., Reference Kohlmann, Nielsen and Ladisch1991; Chavan et al., Reference Chavan, Chavan, Khedkar and Jana2011), also influence the plasmin system activity (Fajardo-Lira et al., Reference Fajardo-Lira, Hayes and Nielson2000; Frohbieter et al., Reference Frohbieter, Ismail, Nielsen and Hayes2005; Larson et al., Reference Larson, Ismail, Nielsen and Hayes2006) during cold storage of raw and pasteurized milk. The effect of heat on the plasmin system has been studied to reveal varied thermal stabilities and heat-induced interactions involving the plasmin system components. In literature, however, there are no reports on the activation of bovine plasminogen by free fatty acids (FFA).

Traditional methods for identifying mastitis infections in milk occur prior to commercial processing and include somatic cell count and culturing. In contrast, newer methods employ polymerase chain reaction and sequencing, nanotechnology and protein detection (Ashraf and Imran, Reference Ashraf and Imran2018). Additionally, Taher et al. (Reference Taher, Hemmatzadeh, Aly, Elesswy and Petrovski2020) detected the presence of viable but nonculturable bacteria in pasteurised and UHT milk, which may have negative implications for the industry. Thus, an easy method to identify plasminogen activation in UHT milk would be advantageous.

The aim of this study was firstly to evaluate if commercial bovine plasminogen can be activated to active plasmin by the principal FFAs present in milk. Secondly, if the actions of native plasminogen activators within colostrum and mastitic milk could activate plasminogen to plasmin and be detected using plasminogen agar plates.

Materials and methods

Free fatty acid plasminogen activation determination

Preparation of the FFA stock solutions

Stock solutions for each FFA in a powder or paste form were prepared by weighing 0.02 g of each FFA and individually adding to 980 µL of the 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The samples were mixed using a vortex mixer for 2 min and incubated in the ultrasonic water bath at 50°C for 15 min to obtain a homogeneous suspension. The FFA cocktail was prepared similarly to what has been described above, but in this case, 10 µL of each FFA suspension was added into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube.

The activation of plasminogen by commercial FFA

Bovine plasminogen (0.32 U/mg) (EC 232.641.9) and plasmin (EC 3.4.21.7) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich, South Africa (P9156 and 10,602,370,001, respectively). The plasmin (5 U/mL) originated from bovine plasma. At a volume of 50 µL, commercial free-fatty acids based on their respective carbon content, namely butyric acid (C4), 2-keto-d-gluconic acid (C6), hexanoic acid (C6), octanoic acid (C8), decanoic acid (C10), DNP-ε-amino-N-caproic acid (C12), lauric acid (C12), tridecanoic acid (C13), myristic acid (C14), palmitic acid (C16), stearic acid (C18), linoleic acid C18) and oleic acid (C18:1) were added independently and as a cocktail to 950 µL of plasminogen phosphate buffer. The samples were incubated for 3 h at 37°C to enable the FFA to activate plasminogen. After the incubation period, the samples were evaluated and assayed for plasminogen activation to plasmin using the milk agar plate and the Merck protease assay.

Detection of plasmin activation using the Merck protease assay kit

The proteolytic level of plasmin protease activity (U mL−1) induced by plasminogen activators (commercial FFA) was assayed with the spectrophotometric Merck protease assay kit. Each sample was prepared according to the supplier's assay protocol (Calbiochem user protocol, 2007).

Preparation of milk agar for protease activity detection (clearing zones)

A total volume of 500 mL of milk agar (bacteriological) solution in 2 × 250 mL First Erlenmeyer flasks were prepared to contain 250 mL low-fat UHT milk and the 10 mL plasminogen buffer (in the case of the internal control only phosphate in glycerol without plasminogen was used). The second 250 mL flask contained 1% agar. The first flask containing UHT milk, was preheated to 55°C in a water bath. The second flask containing agar, was heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min in order to dissolve the agar, after which it was placed in a water bath at 55°C for 30 min to cool down. Subsequently, the first flask containing the UHT milk was mixed with the agar solution in a 2 L Schott bottle and sterilised by autoclaving at 121°C for 20 min. After sterilisation, the milk–agar solution was placed in a water bath at 55°C for approximately 20 min to cool down. The sterile milk–agar solution (±10 mL) was aseptically poured into sterile Petri dishes. After cooling and setting for 15 min, the Petri dishes were stored upside down on the benchtop at room temperature for 24 hours to dry and to detect any possible microbial contamination. The Petri dishes were then wrapped in plastic and stored in a refrigerator at 4°C until further use. The supernatant (5 µL) from each sample was pipetted onto the milk agar plates (triplicate) and incubated at 37 °C upside down for 24 h to observe the formation of the clear protein hydrolysis zones (Hattingh, Reference Hattingh2017). This milk agar method is a modification of the method established by Fransen et al. (Reference Fransen, O'Connell and Arendt1997).

Statistical analysis

Treatments were compared using one-way analysis of variance, and the means were differentiated with the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test at α = 0.05 (NCSS Statistical Software package (2017), ver 11.0.20, LLC, Kaysville, Utah, USA, 2018).

Plasminogen agar plate method

Abnormal milk

The raw, mastitis (somatic cell count [SCC] > 500,000/mL) and colostrum milk (48 h postpartum) were obtained from three separate Holstein milk producers.

Proteolytic enzymes and plasminogen buffer

Bovine plasminogen was prepared as a stock solution by dissolving 20 mg of the plasminogen powder in 1400 µL DH2O, topping it up to 2 mL with 600 µL glycerol. For experimental purposes, 8 mL of a 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) solution was added to the 2 mL of plasminogen with glycerol. This 10 mL plasminogen buffer was added to the UHT milk during the preparation of the milk agar plates in order to fortify plasminogen levels.

Preparation of the plasminogen activation agar plates

The same process was followed as for milk agar plates for protease activity detection (clearing zones).

Preparation of abnormal milk type for plasminogen activation

The three abnormal milk samples (1 mL) were precipitated using 0.1 M HCl (250 µl) followed by 5 s vortex mixing step. The samples were then centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge tube for 20 min at 10,000 rpm to obtain a clear supernatant.

Preparation of milk agar for plasminogen activation detection (clearing zones)

The supernatant of the three milk samples was pipetted (5 µL) on top of the milk agar within the Petri dishes and incubated upside down at 32°C for 24 h (Hattingh, Reference Hattingh2017). This milk agar method is a modification of the method established by Fransen et al. (Reference Fransen, O'Connell and Arendt1997).

Results and discussion

Free fatty acid plasminogen activation determination

Assay for plasmin protease activity induced by various FFA using the Merck protease assay kit

All the samples of the Merck protease assays (Table 1), except lauric acid (C12) (0.336 U mL−1) and tridecanoic acid (C13) (0.354 U mL−1) showed significantly higher proteolytic activity than the negative control (0.338 U mL−1).

Table 1. Proteolytic activity of plasmin protease on free fatty acids and a fatty acid cocktail (proteolytic activity determined by the Merck protease kit)

Means with a different superscript in the same column differ significantly.

Values are means of triplicate.

Most significant plasmin activity was observed in samples with (decreasing order), butyric acid (C4), hexanoic acid (C6), palmitic acid (C16), oleic acid (C18:1), FFA cocktail, 2-keto-D-gluconic acid (C6), decanoic acid (C10), myristic acid (C14), DNP-ε-amino-N-caproic acid (C12), linoleic acid (C18), stearic acid (C18), and octanoic acid (C8) when compared against a negative control (plasminogen without FFA activators). This activity indicated that plasminogen was activated significantly to plasmin by the FFA. The positive control (KIO3) indicated that plasminogen could be activated to plasmin protease (Enright et al., Reference Enright, Bland, Needs and Kelly1999). Thus far, only Kelly and Fox (Reference Kelly and Fox2006) have established that plasminogen in milk is activated to plasmin protease by the FFA oleic acid, but there is no evidence to substantiate the findings.

Evaluation of clear zones using the milk agar test

This test was done to determine whether commercial FFA could activate inactive plasminogen to plasmin protease. After incubation of plates for 24 h at 32°C, clearing zones were visible (Figure 1). Plasminogen can only be activated to plasmin and no other compounds. The formation of zones was, therefore, the result of plasmin action.

Figure 1. Casein digestion (clear halo) as a result of plasminogen activation by various free fatty acids (FFA) to plasmin protease *CT = cocktail of FFA, PC = positive control KIO3, NC = negative control. Section 1 C4 (top row in triplicate), C6 (middle row in triplicate +), C8 (bottom row in triplicate). Section 2 C6 (top row in triplicate), C10 (middle row in triplicate), C12 (bottom row in triplicate). Section 3 C12 (top row in triplicate), C13 (middle row in triplicate), C18 (bottom row in triplicate). Section 4 C14 (top row in triplicate), C18:1 (middle row in triplicate), CT (bottom row in triplicate). Section 5 C18 (triplicate). Section 6 PC (top row in triplicate), NC (middle row in triplicate), C16 (bottom row in triplicate).

The individual and combined roles of FFA were evaluated on the milk agar plates. It was established that there were clear zones formed as a result of plasminogen activation to plasmin-induced by FFA, butyric acid (C4, plate 1), hexanoic acid (C6, plate 2), decanoic acid (C10, plate 2), DNP-ε-amino-N-caproic acid (C12, plate 3), linoleic acid (C18, plate 3), myristic acid (C14, plate 4), oleic acid (C18:1, plate 4), palmitic acid (C16, plate 6), stearic acid (C18, plate 5) and the cocktail of all the FFA (CT, plate 4) as shown in Figure 1. Also, it is important to note that plasminogen can only be activated to plasmin and no other protease, as the formation of zones with sharp edges confirmed that the activity was due to plasmin protease action (Plasmin zones have a well-defined sharp edge, whereas the edge of other non-plasmin proteases studied is almost a smear [data not shown]). Thus, the formation of clearing zones by plasmin was compared against a negative control (plasminogen in the absence of FFA activators) (NC, plate 6). The FFA, namely, lauric acid (C12) and tridecanoic acid (C13), did not exhibit zones of hydrolysis in the plates. Some of the zones could not be captured by the camera, which included 2-keto-d-gluconic acid (C6, plate 1), and octanoic acid (C8, plate 1). The results obtained in the milk agar test corresponded with the results obtained from the Merck assay method. Plasmin plays an important role in age gelation and if the plasminogen can be activated by FFA it will be harmful to milk stored for longer periods, such as ultra-pasteurised and ultra-high temperature milk, due to the fact that plasminogen is still intact and can be activated to plasmin, resulting in potential age gelation, which may have a negative effect on the consumer.

Plasminogen agar plate method

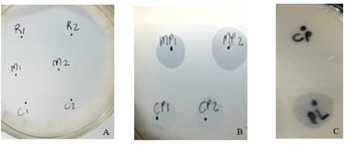

Plasminogen activation in the raw, mastitis and colostrum milk agar plates are shown in Figure 2. Plate A served as the control, with supernatants from raw milk (R1 and R2), mastitis milk (M1 and M2) and colostrum milk (C1 and C2) without plasminogen buffer. No halos developed in the absence of plasminogen buffer within the incubation time. Thus, no plasmin activity was induced when the native milk was added, probably because of the low plasminogen levels in raw milk. Plate B contained the plasminogen buffer with supernatants from mastitis (M1 and M2) and colostrum (C1 and C2) pipetted onto a milk agar plate. Clear, sharp-edged halos soon developed in the plates that were indicative of plasmin activity. It was clear that plasminogen was activated to plasmin and that activators were present in these abnormal milk types. Plate C with supernatants from normal raw milk (CP) did not activate plasminogen within the incubation time. Commercial bovine plasmin (PL) was included as an internal control protease to test agar plate functionality.

Figure 2. Milk agar plates with the raw, mastitis and colostrum samples. Plate A contains no plasminogen buffer with raw milk supernatant (R1 and R2), mastitis supernatant (M1 and M2), and colostrum supernatant (C1 and C2). Plate B contains plasminogen buffer with mastitis supernatant (MP1 and MP2) and colostrum supernatant (CP1 and CP2). Plate C contains raw milk (CP) and active plasmin (PL, internal control) on a milk agar plate plus plasminogen buffer.

Constituents within mastitis and colostrum milk were capable of activating plasminogen to plasmin, as evidenced on the milk agar plate containing plasminogen buffer (Datta and Deeth, Reference Datta and Deeth2001). Raw milk did not contain high levels of plasminogen activators and no clearing zone was formed. It was expected that with an increased incubation time, a clearing zone would have become visible. The fact that plasminogen survived sterilisation was once again proof of the stability of plasminogen towards heat exposure 97°C for 15 min. This technique will enable processing plants to avoid abnormal milks with high levels of plasminogen activators (somatic cell count and colostrum) that could activate to plasmin and result in proteolysis and age gelation during UHT storage at room temperature.

Conclusions

The short, medium and long-chain fatty acids have the ability to activate plasminogen to plasmin. The long exposure of UHT milk to room temperature contributes to plasminogen activation to plasmin and the resulting low level of proteolysis, even at low levels, resulting in age gelation in UHT milk (viscosity slowly increases).

Additionally, the plasminogen agar plate method will enable processing plants to detect abnormal milk with high levels of plasminogen activators (high somatic cell count and colostrum) that could activate to plasmin and result in proteolysis during UHT storage.

Acknowledgements

Milk SA (Milk South Africa) is acknowledged for financial support and the National Research Foundation of South Africa for funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.