Introduction

As recent years and decades have impressively demonstrated, one and the same policy problem can be addressed with solutions of widely varying complexity. The policies governments adopt to solve societal problems like raging viruses, obesity, gun violence, or unemployment are cases in point, as they vary enormously in terms of detail and differentiation. To this date, however, we know only very little about the origins of this variance. Why are policies sometimes simple and straightforward and why are they sometimes highly intricate, contingent and inaccessible? Is the complexity of public policies exclusively driven by functional considerations, or does the phenomenon also have institutional and political roots?

We need better answers for these questions for several reasons. First, more complex policies are more difficult to evaluate (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Steinebach and Knill2018), bind more implementation resources (Limberg et al., Reference Limberg, Steinebach, Bayerlein and Knill2021) and generally require legislators to delegate more authority to rule‐making bodies (Anastasopoulos & Bertelli, Reference Anastasopoulos and Bertelli2020; Franchino, Reference Franchino2004; Senninger, Reference Senninger2020). Accordingly, complex policies entail significant transaction costs for democratic political systems (Hurka & Haag, Reference Hurka and Haag2020). Second, policy complexity can significantly undermine compliance and thereby threaten the effectiveness of political programs, with tax codes being the most notorious example (Kaplow, Reference Kaplow1996). Finally, excessive complexity can also affect the perceived legitimacy of democratic decisions, when the legal principle leges ab omnibus intellegi debent (‘Laws must be understood by all’) is increasingly hard to achieve. Accordingly, policy complexity entails important normative implications for democratic governance.

While there are certainly very often functional and rather technical reasons for varying policy complexity, there is also good reason to suspect that policy complexity is crucially affected by institutional and political factors. Focusing on the political system of the European Union (EU), I show in this article, that the inclusiveness of decision‐making processes (i.e., the number of veto players involved) and the degree of preference bias and heterogeneity within a collegial decision‐making body (i.e., the extremeness of its median member and its dividedness), constitute major costs of policy formulation and jointly lead to more complex policy proposals. For several reasons, the EU is ideally suited to test these ideas. First, the EU features substantial variance both with regard to the inclusiveness of its decision‐making procedures and with regard to the preferences represented within the EU's main agenda‐setting institution, the European Commission (from now on: the Commission). This allows us to exploit variance in institutional and political variables of interest, while holding many confounding factors constant. Second, given its technocratic reputation, the Commission can be considered a least‐likely case to confirm political explanations of policy complexity. In other words, if we find political factors to matter for the complexity of public policies in the Commission, we should expect them to play an even more important role in other empirical contexts, for example, at the national level. Finally, the case selection also allows the study to contribute to the literature on EU legislative politics. In particular, the study highlights the political character of the Commission as the EU's main agenda‐setter and suggests that partisanship might be more important during the policy formulation process than previously thought. Moreover, the study's findings imply that the Commission uses its right of legislative initiative strategically by calibrating the complexity of its policy proposals in response to various degrees of legislative uncertainty, generated by the inclusiveness of the decision‐making procedure.

The paper is structured as follows: after a brief literature review, the paper argues that on a conceptual level, the complexity of a policy should be thought of as a feature of its underlying compromise design. Based on this assumption, the paper develops research hypotheses on how political and institutional costs of policy formulation favour the creation of complex policies. The paper then introduces the data foundation which is employed to put these theoretical expectations to an empirical test. The empirical section reveals that after controlling for functional explanations, political and institutional factors play a major role in shaping the complexity of policy outputs.

The politics of policy formulation

When searching for the roots of complex policies, the policy formulation stage can be considered a natural starting point. In parliamentarian systems, governments and their ministerial bureaucracies often dominate this phase of political decision making (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). In a typical scenario, the ministries responsible for a given issue area take a leading role and draft the initial proposals, which are then adopted by the cabinet and sent into the legislative process, where they can be amended by a varying amount of veto players (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002). In many instances, however, cabinets operate on the principle of collegiality, which implies that the cabinet takes collective responsibility for its policy proposals. This means that policy drafters always operate in the shadow of the cabinet and hence, cannot ignore the preferences of the other members of government and – importantly – the presence of other veto players, like the chambers of parliament (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020). This pattern is particularly pronounced in coalition cabinets, which are composed of members from different political parties (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020) and in consensual political systems, where multiple institutional constraints affect the leeway of governments (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012).

These insights have also been reflected in EU scholarship in recent years. While classic approaches had relied on the assumption that the institutions of the EU act as unitary actors during legislative processes, it has become increasingly clear that this assumption is at odds with the empirical reality of how the EU operates. In fact, several studies have shown that the Commission applies distinct patterns of interdepartmental coordination (Blom‐Hansen & Finke, Reference Blom‐Hansen and Finke2020; Senninger et al., Reference Senninger, Finke and Blom‐Hansen2021) and that the way the Commission coordinates its business internally has significant repercussions for the content of the policies it adopts (Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Rauh, Reference Rauh2019, Reference Rauh2021; Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2013). To a large extent, this is due to the fact that also the Commission operates on the principle of collegiality, which implies that ‘each Commissioner must be consulted on every proposal’ (European Commission, 2021). This strict consensus norm would hardly complicate policy formulation if the Commission's main decision‐making body, the College of Commissioners (CoC), were a highly homogeneous group of politicians with similar preferences. Yet, ample research has demonstrated that this is not necessarily the case (Wille, Reference Wille2013; Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Egeberg, Reference Egeberg2006; Wonka, Reference Wonka2007; Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2013). As Wonka (Reference Wonka2008) has shown, for example, Commissioners take the preferences of their colleagues into account when drafting their policy proposals and also interfere in policy areas outside of their own portfolio when national interests are at stake. Commissioners are also often members of a governing party in their member state and the number of non‐partisan Commissioners has decreased over time (Döring, Reference Döring2007). In addition, Franchino (Reference Franchino2009) demonstrated that the ideological profiles of potential Commissioners matter when portfolios are distributed, especially with regard to their positions on the left/right scale. Accordingly, Hix (Reference Hix2008, p. 1259) argued that the CoC should be seen ‘as a party‐political coalition between the parties in government at the time of the appointment of the Commission’. In one of the most comprehensive studies on decision making within the Commission to date, Hartlapp et al. (Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014) analysed the formulation of 48 policy proposals and held 130 interviews with Commission officials, concluding that internal interaction in the Commission ‘is quite intense and often conflictual’ (Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014, p. 5). Accordingly, there is no obvious reason to expect the Commission to be immune from the struggles and disagreements that characterize policy formulation processes at the national level (Wille, Reference Wille2013).

One unresolved question in the literature is whether these political and institutional factors also increase the complexity of the Commission's policy outputs. Despite its normative relevance for the legitimacy and effectiveness of democratic governance, political science has hardly paid any systematic attention to the analysis of policy complexity. Is the complexity of a policy only the result of functional requirements inherent to the policy domain at hand or are there also institutional and political factors that incentivize the formulation of complex policies? To answer this question, we first need a solid understanding of what policy complexity is.

What makes a policy complex?

Unlike political science, legal scholarship has a long tradition of dealing with policy complexity from a normative perspective (e.g., Schuck, Reference Schuck1992; Webb & Geyer, Reference Webb and Geyer2020) and with empirical‐analytical ambitions (e.g., Waltl & Matthes, Reference Waltl and Matthes2015; Katz & Bommarito II, Reference Katz and Bommarito II2014; Bommarito II & Katz, Reference Bommarito II and Katz2010). Yet, the question of what exactly constitutes a complex policy has always been contested and no single, authoritative definition exists in the literature. The association most people probably have in mind if they were asked to define a complex policy is some notion of ‘difficulty’ or ‘technicality’. For example, most people would arguably find policies regulating financial markets or chemical substances very complex as they lack the necessary expert knowledge to understand them. Alternatively, policies might be considered particularly complex if they are difficult to understand or apply in a legal sense, either because they are strongly connected to a host of other policies or because their individual legal provisions are highly interdependent. Finally, complexity can result from a high level of detail, that is, when policies address their targets on a very fine‐grained level.

In this study, I adopt another conceptual perspective and argue that the complexity of a policy is a feature of its underlying compromise design. Some policies are very straightforward in the sense that their design is based on few or no constraints, scope conditions, derogations, specifications or loopholes. Other compromise designs are much more complex and contain a multitude of such instruments, which all serve to reconcile competing values, interests and preferences in one coherent policy text. This complexity of a compromise design is not necessarily related to the technicality or difficulty of the subject matter, but can vary regardless of what exactly is being regulated. The complexity of a policy is therefore not so much based on what the policy is about, but on how the policy is designed.

Policies are written for different audiences, or ‘end users’ (Katz & Bommarito II, Reference Katz and Bommarito II2014), like implementers, corporations or ordinary citizens. Any individual end user needs to invest cognitive capacities to read, process and understand the substance contained in these policies in order to be able to comply with them. While the required cognitive capacities vary depending on the expert knowledge of the end user, the transaction costs required to internalize the substance of a policy generally increase with the complexity of how the policy is designed. In this context, it is important to understand that the main mechanism through which more complex policy designs affect those transaction costs is by raising the difficulty of the language by which they are communicated. If the design of a policy compromise increases in terms of complexity, for example, through the incorporation of conditional clauses, this directly impacts the way a policy is formulated and thereby the transaction costs end users need to expend to process the policy cognitively (Senninger, Reference Senninger2020; Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Munger and Spirling2019; Tolochko et al., Reference Tolochko, Song and Boomgaarden2019).

Conceptualizing the complexity of a policy as a feature of the policy's underlying compromise design yields several analytical advantages over alternative approaches in the present research context. First, the conceptualization allows us to obtain a more fine‐grained understanding of how policies are designed than the widely established practice of equating policy complexity with policy length, for example, by assessing a policy's number of words (e.g., Kousser, Reference Kousser2006) or recitals (e.g., Rasmussen & Toshkov, Reference Rasmussen and Toshkov2011). Second, while previous network‐analytical research has shown that also the interdependence between individual laws is an important component of their complexity (e.g., Katz et al., Reference Katz, Coupette, Beckedorf and Hartung2020; Koniaris et al., Reference Koniaris, Anagnostopoulos and Vassiliou2018; Fjelstul, Reference Fjelstul2019), such a relational approach to policy complexity mainly yields benefits if our analytical interest is centred on the aggregate growth and evolution of entire legal landscapes.

Accordingly, I argue that the complexity of a policy is not directly related to the technicality and difficulty of its policy content, but that it is a consequence of how the underlying policy compromise is structurally designed. Given those conceptual considerations, the next section provides a theoretical framework to explain why the complexity of policies varies and how complex policies are affected by the political and institutional costs that accrue during the process of policy formulation.

Theorizing complex policies: The political and institutional costs of policy formulation

This theory section consists of two parts. First, I argue that the complexity of policy proposals should increase as a function of the political costs of policy formulation that accrue within a group of decision makers. These political costs are conceptualized as the combination of internal preference heterogeneity and bias. Second, I propose that there are also institutional costs of policy formulation associated with the inclusiveness of the decision‐making process that follows after the adoption of the initial policy proposal. When more actors have the power to veto and amend a legislative proposal, this increases legislative uncertainty for the agenda‐setting institution and provides incentives for more complex proposals.

The political costs of policy formulation: Preference heterogeneity and bias

When governments formulate new policy initiatives, they often need to reconcile quite diverse ideas, interests and policy preferences in their policy proposals. While governments typically operate on a clear division of labour along the lines of ministerial portfolios during policy formulation, ministers are aware that their proposals need to be agreed upon by the entire cabinet before the legislative process can continue. This implies, however, that those in charge of drafting the policy proposal cannot simply propose their own ideal point during the policy formulation process, but need to pay close attention to the preference distribution of the cabinet. This preference distribution has two major components that jointly enhance the political costs of policy formulation: preference heterogeneity and preference bias.

First, when decisions are made on the basis of the collegiality principle and if we invoke the classic assumption of rational choice institutionalism that preferences are fixed and exogenously given, the costs of arriving at a policy compromise are higher the more the preferences of the decision makers diverge. When the members of a decision‐making body are highly unified, these low political costs of policy formulation should be reflected in a comparatively simple policy compromise, which does not need to factor in the positions of preference outliers. As preferences diverge, however, we should expect to see an increase in the complexity of the compromise design. In this scenario, the decision‐making body will come under pressure to fine‐tune the compromise to the interests of a more diverse group of decision makers. These increasing political costs of policy formulation should be reflected in policy proposals formulated in rather complex language. The mechanism at play here is essentially the same that dominates the negotiation of coalition agreements at the national level: as the ideological heterogeneity of the negotiating parties increases, the resulting coalition agreement needs to become more complex (Strøm & Müller, Reference Strøm and Müller1999; Indridason & Kristinsson, Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013). Complexity ensures that the preferences of all relevant stakeholders are sufficiently reflected in the agreement.

-

H1a (unconditional effect of preference heterogeneity): As preference heterogeneity increases within a decision‐making body, the agreed‐upon policy compromises become more complex.

Yet, in practice, the principle of collegiality is often understood as a norm underlying the policy formulation process, not as a decision rule. Formally, also collegial cabinets eventually often decide by majority and given the fact that also the CoC – either explicitly or implicitly – decides on a simple majority basis, ‘there are plausibly limits to how far policies can drift from the median commissioner’ (Blom‐Hansen & Senninger, Reference Blom‐Hansen and Senninger2021, p. 633). While policies are drafted at the administrative level of the Commission, coordination across departments always takes place under the shadow of a potential majority vote in the CoC. Hence, we can assume that when policies are drafted at the administrative level, the distribution of preferences at the political level are taken into account.Footnote 1

When policies are drafted, the position of the median member in the cabinet should therefore be of critical importance. Yet, a more biased median decision maker does not necessarily lead to more complex policy compromises. If the median is biased towards either side of the political spectrum, but decision makers are united behind this biased median, there is no obvious reason to expect the formulation of more complex policy compromises, as the political costs of policy formulation are hardly enhanced in this scenario. If the median moves to the extremes and preference heterogeneity increases simultaneously, however, this should raise the costs of finding a viable policy compromise significantly. This is because, in this scenario, two pressures are at odds with each other: on the one hand, the collegiality principle dictates that any compromise should reflect the positions of a highly diverse group of policy makers; on the other hand, the balance of power is tilted towards a biased sub‐group of these policy makers. Under these circumstances, political costs of policy formulation are maximized and the resulting policy compromises should display high degrees of complexity.

-

H1b (conditional effect of preference heterogeneity): As preference heterogeneity and preference bias increase jointly within a decision‐making body, the agreed‐upon policy compromises become more complex.

Selecting the European Commission as a case to test these hypotheses yields the main analytical advantage that given its technocratic reputation, the Commission can be considered a least‐likely case to confirm the hypotheses. If we find these political factors to make a difference for policy formulation in the Commission, it is quite likely that they also matter in contexts in which we would expect political conflicts to be more pronounced to begin with, for example, on the national level.

The institutional costs of policy formulation: Procedural inclusiveness

Beyond political pressures, we should also expect institutional arrangements to affect the strategic considerations of governments when they formulate policy proposals. In particular, the inclusiveness of the decision‐making process by which a legislative proposal is negotiated should be of relevance as an important institutional cost of policy formulation. In the EU, rules of decision making and their applicability to particular policy issues have changed considerably with successive Treaty revisions. Although the consultation procedure had been in extensive use up until 2009, the Lisbon Treaty made co‐decision the so‐called Ordinary Legislative Procedure (OLP). While consultation merely grants the European Parliament (EP) the right to a non‐binding opinion and a right to delay the legislative process (Kardasheva, Reference Kardasheva2009), co‐decision/OLP upgrades the EP to a legislator equal to the Council with full veto and amending rights (Tsebelis & Garrett, Reference Tsebelis and Garrett2000; Costello & Thomson, Reference Costello and Thomson2013). Thus, the EU has effectively been operating a ‘quasi‐unicameral’ and a bicameral system simultaneously over long stretches of its history, which implies that the Commission has been facing varying institutional costs of policy formulation depending on the inclusiveness of the prescribed legislative procedure.

But why should governments care about these institutional costs? If we assume that governments are interested in getting their policy proposals adopted as quickly and with as little amendment as possible, they should try to anticipate and accommodate the interests of all institutions with veto and amending power when formulating their policy proposals (Rauh, Reference Rauh2021). This is why governments often take considerable time to gather information and repeatedly consult with relevant stakeholders before they adopt their positions (Bunea, Reference Bunea2017). They do so to reduce the uncertainty associated with subsequent legislative negotiations. Yet, the amount of uncertainty governments face during the preparation of their policy proposals is a direct consequence of the inclusiveness of the employed decision‐making procedure (Boranbay‐Akan et al., Reference Boranbay‐Akan, König and Osnabrügge2017). When no other actor can veto or amend a government's proposal, the government faces no uncertainty and can simply propose its ideal point. The more veto players enter the scene, however, the higher the uncertainty over the outcome of the legislative process and the stronger the pressure for the agenda‐setter to accommodate this uncertainty in its policy proposals by raising their complexity. In the EU, the Commission has a strong and institutionalized working relationship with the Council during the policy preparation phase, which reduces uncertainty significantly (Blom‐Hansen & Senninger, Reference Blom‐Hansen and Senninger2021). In contrast, however, the position of the EP often becomes clear much later in the legislative process and there is often also substantial uncertainty over who the lead negotiator (the rapporteur) of the EP will be. Thus, the more inclusive OLP raises the institutional costs of policy formulation by enhancing the uncertainty of the eventual legislative outcome of the negotiations for the Commission. This enhanced uncertainty should be reflected in more complex policy proposals. Based on these theoretical considerations, we should find the following relationship to hold:

H2: The complexity of policy proposals increases as the decision‐making process becomes more inclusive.

Data and methods

This section describes the data foundation for the empirical analysis (‘The data foundation’), the operationalization and measurement of the dependent (‘The dependent variables’), independent (‘The independent variables’) and control (‘Control variables’) variables, as well as the study's methodological approach (‘Methodological approach’).

The data foundation

The empirical analysis is based on a dataset containing information on 1771 legislative proposals adopted by the Commission between 1 January 1994 and 3 February 2021 (Hurka et al., Reference Hurka, Haag and Kaplaner2022). The data were retrieved from the EUR‐Lex database (http://eur‐lex.europa.eu/). While the database has certain limitations (Fjelstul, Reference Fjelstul2019; Blom‐Hansen, Reference Blom‐Hansen2019), it is widely used in academic research and is quite extensive in its coverage since the year 1994 (Rauh, Reference Rauh2021; Ovádek, Reference Ovádek2021). Please see the Appendix in the Supporting Information for information on text pre‐processing and parsing.

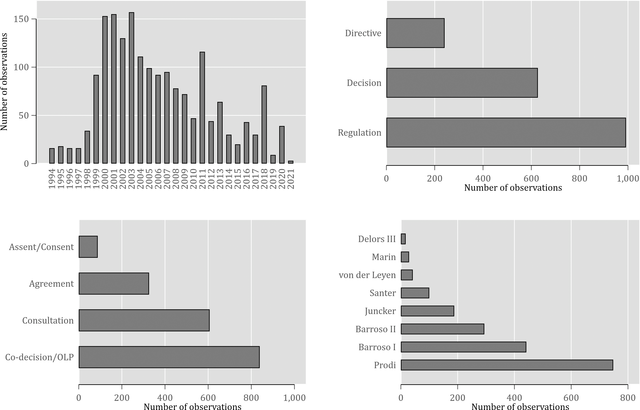

Figure 1 displays how the 1771 observations are distributed over time, legal instruments, legislative procedures and Commission administrations. For the analysis of textual difficulty (i.e., readability), the sample size is reduced to 1202 due to formatting issues in some proposal texts, in particular missing line breaks. While these missing line breaks do not invalidate the measurement of semantic diversity, which is based on a bag‐of‐words approach, they potentially cause problems for the parser in identifying the boundaries of sentences and hence, threaten the validity of the readability calculations (see ‘The dependent variables’ subsection). The Appendix in the Supporting Information demonstrates that the different sample sizes do not affect the substantive findings, however.

Figure 1. Distribution of observations.

To maximize the comparability of the individual legislative proposals, the empirical analysis does not contain any amending proposals, codifications and recasts. Furthermore, next to the two main legislative procedures of theoretical interest in H2 (consultation and co‐decision/OLP), also some assent/consent and agreement procedures are part of the sample. Excluding those cases does not affect the conclusions (see the Appendix in the Supporting Information).

The dependent variables

In this study, I capture the complexity of policy proposal's underlying compromise design by the policy text's syntactic and semantic properties. While the former can be approximated by assessing the text's readability, the latter requires a measure for the conceptual diversity featured in the text. Various readability measures have been proposed in the literature, but the most common one is arguably the Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease (FRE; Flesch, Reference Flesch1948). The measure is based on the syntactical properties of a text, in particular sentence and word lengths and it is defined as follows:

Accordingly, higher FRE values indicate better readability, as they result from shorter words and sentences. It is commonly assumed that understanding texts scoring below 50 requires an academic education, while texts scoring between 50 and 60 are still quite difficult to understand. To make sure that higher values reflect higher complexity, the FRE score is reversed in the empirical analysis.

To capture semantic diversity, I follow the approach advocated by Katz and Bommarito II (Reference Katz and Bommarito II2014, p. 354ff.) and rely on Shannon's word entropy (Shannon, Reference Shannon1948):

where pw is the probability p of a token's occurrence in the given bag of tokens w, whereas I use lemmatized unigram tokens of the proposal text to measure word entropy. In the language of information theory, word entropy measures the minimum amount of ‘bits’ required to store the information contained in a variable (in our case, a legislative text). When texts contain very uniform language, the contained information can be reduced to only a few bits, leading to a low word entropy score. In contrast, when texts contain very diverse language, every individual word entails a large amount of unique information, which implies that we require more ‘minimum storage space’ to represent the raw data, leading to higher word entropy. As Katz and Bommarito II (Reference Katz and Bommarito II2014, p. 358) have shown, word entropy is a useful indicator to distinguish texts ‘with central clustered topics from those embracing a far more diverse set of subjects’.

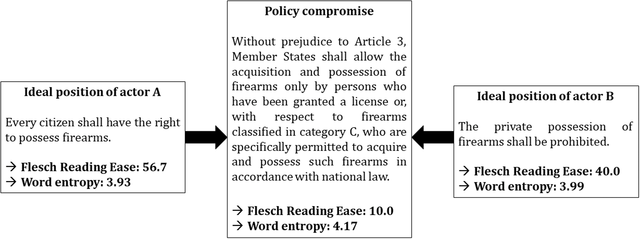

A simple, hypothetical example helps to illustrate how syntactic and semantic complexity increase when ideal positions are merged into a policy compromise (see Figure 2). In this scenario, two political actors A and B hold diametrically opposed views on whether citizens should be allowed to possess firearms and both need to strike a compromise. Actor A favours complete legalization, whereas actor B favours a comprehensive ban. While the difficulty of achieving a compromise is certainly very high on such a value‐laden policy issue, governments around the world have demonstrated that such compromises are possible by tying the legality of firearm possession to certain conditions (Hurka, Reference Hurka, Knill, Adam and Hurka2015). In Figure 2, the policy compromise is the text of Article 4a of the EU Firearms Directive in its current version. It is virtually impossible to formulate such a compromise in simpler and more uniform language than the respective ideal positions. Not only readability declines, also the variety of the language required to formulate the compromise increases due to the definition of the scope conditions for legality. The values of the two indicators for the respective texts underline the argument, which can easily be extended to every other policy conflict.

Figure 2. Illustration of a complex policy compromise.

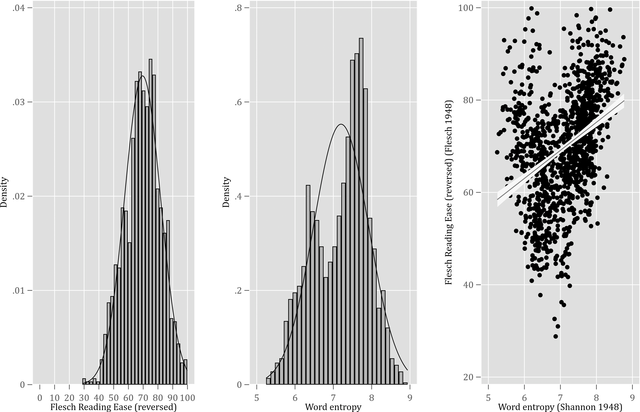

Figure 3 displays how both dependent variables are distributed in their respective samples. Both variables are mildly correlated (r = 0.37), indicating that readability tends to decline as semantic diversity increases.Footnote 2 The relationship even appears to follow a curvilinear pattern, which suggests that the dataset also contains policy proposals of a limited scope that are nonetheless formulated in a very complex way.

Figure 3. Distribution of the dependent variables.

The independent variables

To test the influence of preference bias and heterogeneity (H1a/b), the analysis focuses on the preference distribution of the incumbent Commissioners’ national parties on the general left/right dimension. I skip the pro‐/anti EU dimension, because due to its institutional role as the ‘Guardian of the Treaties’, the Commission operates on an institutionally designed pro‐EU bias and hence, there is only very limited variance within the Commission on this conflict dimension (see also Warntjen et al., Reference Warntjen, Hix and Crombez2008, p. 1248). To arrive at measures for preference bias and heterogeneity, I first constructed a dataset tracking the partisan composition of the Commission on a daily basis from 1 January 1994 until 19 March 2021, combining data provided by Döring (Reference Döring2007) and the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP), which contains estimates for policy positions of political parties based on their election manifestos (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020a).Footnote 3 Party positions based on CMP data come with well‐known limitations. For example, positions communicated in party manifestos might partially reflect strategic electoral considerations instead of sincere policy preferences and they are generated at the national, not the supra‐national level. In addition, while the correlation between the CMP positions and those derived from expert surveys is rather high, temporal shifts in preferences are not correlated across alternative measurement strategies (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019). Limitations like those need to be kept in mind when interpreting the results of this study. However, CMP data also have the main advantages that they are available over a rather long period of time and that they are potentially less influenced by observed political behaviour than estimates derived from expert surveys. Accordingly, they can be considered an exogenous measure allowing me to assess how political preferences are distributed in the CoC. In the past, several previous studies have adopted the same approach to describe the distribution of preferences in the Commission (e.g., Franchino, Reference Franchino2009; Klüver & Sagarzazu, Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2013; Ershova, Reference Ershova2019; Warntjen et al., Reference Warntjen, Hix and Crombez2008) and the approach broadly resembles previous attempts to measure the partisan composition of EU institutions (e.g., Manow et al., Reference Manow, Schäfer and Zorn2008). Of course, this study also cannot provide bullet‐proof evidence that national party positions perfectly represent the policy preferences of individual Commissioners, but we already know that appointments to the Commission are driven at least partially by partisan considerations (Wonka, Reference Wonka2007). Hence, ‘because almost all Commissioners are career party politicians, it is not unreasonable to assume that the left–right […] locations of a Commissioner's national party are correlated with the Commissioner's positions on these dimensions’ (Crombez & Hix, Reference Crombez and Hix2011, p. 302).

To calculate how preferences are distributed in the Commission, I use the CMP's rile‐variable as introduced in Laver and Budge (Reference Laver and Budge1992).Footnote 4Preference heterogeneity within the Commission is operationalized by the standard deviation in the distribution of left/right positions represented by the parties of the Commissioners. Average preference bias is represented by the position of the Commissioner located at the median of the preference distribution. Yet, the theoretical interest of this study is not so much related to the absolute position of the Commission median at a given point in time, but to the question of how extreme this median position is relative to the ‘average’ Commission. The easiest way to translate this idea into an empirical strategy is to use standardized values of the median positions, which measure the number of standard deviations the position of the median Commissioner at any given point in time is located from the average median Commissioner. A value of 0 implies that the College's median is located at the long‐term average. A value of 1 (−1) implies that the median on the respective day is located one standard deviation to the right (left) of this long‐term average. The same logic is applied to preference heterogeneity.

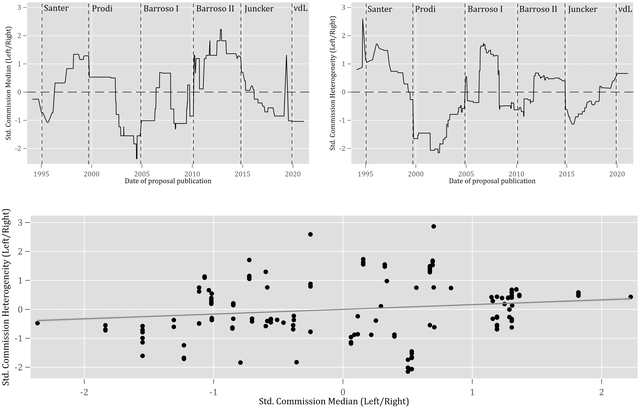

Figure 4 shows how standardized preference bias and heterogeneity have evolved over time and that they are mildly correlated (r = 0.16). The Appendix in the Supporting Information contains robustness analyses in which the median is replaced by the mean to measure bias, and the standard deviation is replaced with the range of the distribution to measure heterogeneity.

Figure 4. Distribution of preference bias and heterogeneity.

To test the effects of procedural inclusiveness outlined in H2, the analysis relies on meta‐information relating to the legislative procedure employed for each policy proposal. While the model contains several types of legislative procedures, I mainly focus on those that are most relevant given the empirical frequency of their usage in EU politics and given the theoretical expectations: co‐decision/OLP (i.e., the bicameral scenario) and consultation (i.e., the ‘quasi‐unicameral’ scenario).

Control variables

The empirical analysis includes a range of important control variables. First, we need to take into account that certain policy problems might require more complex solutions than others from a purely functional perspective. Therefore, it is essential to include fixed effects for policy areas, which were coded based on the Commission's sub‐division responsible for the respective legislative proposal, the so‐called Directorates General (DGs). To take into account that problem complexity can also vary within policy areas, I additionally include a variable capturing the number of EUROVOC descriptors enlisted for any individual policy proposal (see Van Ballaert, Reference Van Ballaert2017, p. 415). This proxies both for the autonomy of the lead DG and inter‐departmental coordination requirements (Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Blom‐Hansen & Finke, Reference Blom‐Hansen and Finke2020; Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2013), as well as for the complexity of the underlying policy problem. Another factor that could drive policy complexity is the salience of the policy proposal. Besides focusing only on new (instead of amending) proposals and controlling for the use of different legal instruments (directives, regulations and decisions), the models include several proxies for proposal saliency (or technicality) suggested by Blom‐Hansen and Finke (Reference Blom‐Hansen and Finke2020): the ratio of numbers vs. words in the proposal title, the title's length, whether the title includes words signalling budgetary implications and whether the title mentions one or more member states.

Second, governments are subject to temporal constraints when formulating their policy proposals. Long‐term constraints arise from the fact that policy landscapes are dynamic (Mettler, Reference Mettler2016) and any new policy proposal necessarily needs to take into account the existing stock of legislation. These time trends are captured by the number of days elapsed since 1 January 1960 on the day the proposal was adopted and its squared version to account for possible non‐linearities. Short‐term constraints result from the legislative cycle: governments need time to prepare highly complex proposals and to get them passed (see also Osnabrügge, Reference Osnabrügge2015). Therefore, the models include a squared variable capturing the inversely U‐shaped relationship between the legislative cycle and the complexity of adopted policy proposals (see the Appendix in the Supporting Information). The variable is measured by the number of days elapsed since the Commission took office.

Finally, the models contain a control variable capturing the distance of the Commissioner responsible for the draft proposal from the Commission median to take into account that extreme positions could matter more if they are held by the lead Commissioner. In addition, I control for the number of Commissioners present in the CoC, for the preference heterogeneity in the EP and the Council (using data shared by Haag (Reference Haag2022)), as well as measures for the distance between the Commission median and the median in the other legislative chambers.

Methodological approach

The hypothesis tests are conducted with fixed‐effects linear regressions, in which panels are defined by 17 policy areas. Next to the controls specified in the previous subsection, fixed effects are included for the nationality of the lead Commissioner and the Commission term. This ensures that the research hypotheses can be evaluated while controlling for latent effects of policy area characteristics and general ideological orientations of the Commission. The empirical analysis presented below focuses exclusively on the marginal effects of the key explanatory variables and presents them graphically. The regression tables are available in the Appendix in the Supporting Information along with several robustness checks and descriptive analyses.

Results

This section consists of three parts. First, I evaluate the role of political (‘Evaluating the political costs of policy formulation’ subsection) and institutional (‘Evaluating the institutional costs of policy formulation’ subsection) costs of policy formulation separately. In ‘Additional analysis: How do political and institutional costs interact?’ subsection, I perform an additional analysis on the interaction between political and institutional costs.

Evaluating the political costs of policy formulation

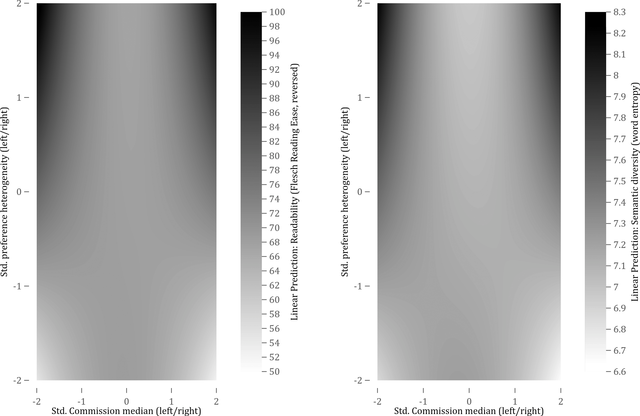

Figure 5 demonstrates how preference bias and heterogeneity jointly shape the complexity of policy compromises adopted by the Commission. The underlying models contain an interaction term of two variables, both in their standardized versions: (a) the standard deviation of the policy preferences represented in the CoC at the time the respective proposal is adopted as an indicator for preference heterogeneity and (b) the squared distance of the Commission median to the long‐term median as a measure for preference bias.Footnote 5 One way to visualize such a complex interaction of continuous variables is a contour plot. Darker areas reflect more complex policy texts, whereas brighter areas indicate simpler policy compromises.

Figure 5. Contour plot on the interplay of preference bias and heterogeneity.

Both plots look remarkably similar and convey the same, general messages. First, when the Commission median is located at a moderate position (i.e., a value of 0), preference heterogeneity has hardly any impact on policy complexity. This suggests that the Commission is very well able to contain policy complexity even under conditions of high preference heterogeneity as long as its median member is a moderate. In this scenario, policy texts generally reflect moderate degrees of textual difficulty and rather low semantic diversity. Substantively, the model estimates no significant difference in textual difficulty as heterogeneity moves from its minimum to its maximum value while holding the median at 0 (p = 0.56). Interestingly, increasing preference heterogeneity has a significantly negative effect on semantic diversity in this baseline scenario (decrease of 0.25 bits, i.e., 0.35 standard deviations, p = 0.03). This indicates that the scope of legislative proposals tends to become somewhat narrower when preferences are dispersed more widely around a moderate median, but the effect is not particularly large. Combining these insights, we can conclude that as long as the median member of the collegial decision‐making body assumes a moderate position, preference heterogeneity does not render the agreed‐upon policy compromises more complex.

But do the effects of preference heterogeneity depend on the location of the median decision maker, as postulated by H1b? Indeed, we find an extreme increase in policy complexity when preferences simultaneously become more heterogeneous and political conflict is structured around a more extreme median. When the Commission median moves from a moderate position to its maximum on the left and preference heterogeneity is simultaneously maximized, textual difficulty increases by 36.13 reversed FRE points (2.97 standard deviations, p = 0.000) and word entropy increases by 1.27 bits (1.76 standard deviations, p = 0.000). On the right, the pattern is similar with an increase of 32.07 reversed FRE points in textual difficulty (2.63 standard deviations, p = 0.000) and an increase of 1.24 bits in word entropy (1.72 standard deviations, p = 0.000). Thus, policy compromises become particularly complex when preference bias and heterogeneity jointly raise the costs of policy formulation. In the Appendix in the Supporting Information, I show that these effects do not materialize if we replace the dependent variable with indicators of proposal length, which suggests that political costs of policy formulation primarily affect the way in which compromises are formulated, not how long they are. This is also bolstered by the finding that the effects remain stable if we replace the dependent variable with alternative indicators (see the in the Supporting Information).

The results therefore suggest that collegial decision‐making bodies like the CoC seem to be able to deal rather efficiently with situations in which their median member is not a moderate or with situations of high preference heterogeneity. They have problems, however, to deal with both situations at once. Yet, the analysis also yields an additional, unanticipated result: when the median member becomes more extreme and preferences become more homogeneous, policy compromises tend to become much simpler, both regarding their readability and their semantic diversity. This suggests that a cohesive group of biased decision makers can formulate simpler policy compromises than a cohesive group of moderates. This makes intuitive sense if we accept that moderate positions are likely more ambiguous and harder to reconcile in a policy compromise than very similar extreme positions.

In sum, complex policy compromises have political roots. For EU research, the findings therefore cast doubt on the ‘technocratic’ character of the Commission and the widespread notion that partisan preferences are irrelevant in the Commission. Even if we control for their national and sectoral backgrounds, Commissioners seem to be responsive to how policy preferences are distributed in the CoC when they formulate policy proposals. Importantly, however, it is not the position of the drafting Commissioner that matters. Instead, it is the degree of political conflict in the CoC as a whole that drives incentives to enhance policy complexity. The highly consistent pattern found on H1b also underlines that processes of policy coordination across governmental departments can crucially affect policy content (Hartlapp et al., Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Senninger et al., Reference Senninger, Finke and Blom‐Hansen2021). Like any other government coalition at the national level, the Commission needs to make sure that its legislative proposals sufficiently accommodate the views of its component members.

Evaluating the institutional costs of policy formulation

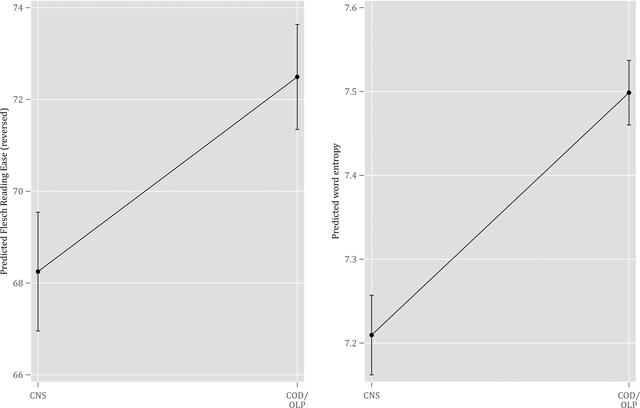

During policy formulation, governments not only need to solve problems arising from internal preference bias and heterogeneity, but also need to anticipate complications that might arise during the following legislative process. This is particularly important in the EU, where the legislative influence of the agenda‐setter is severely constrained during the subsequent legislative negotiations. In H2, I therefore formulated the expectation that the Commission should be inclined to increase the complexity of its policy proposals when legislative uncertainty increases due to the inclusion of EP.

The marginal contrasts displayed in Figure 6 show that this expectation is fully corroborated by the data, both for the syntactic and the semantic structures of policy proposals. In the full model, a switch from consultation to co‐decision/OLP yields a moderate increase in textual difficulty of 4.24 reversed FRE points (0.35 standard deviations, p < 0.000). Similarly, word entropy is estimated to increase by 0.29 bits (0.40 standard deviations, p < 0.000) when the more inclusive decision‐making process is being employed. While these unconditional effects appear small in comparison to the effects of increased preference bias and heterogeneity reported above, they are very robust and highly significant. Contrary to political costs, institutional costs also affect the length of the compromise in expected ways (see the in the Supporting Information).

Figure 6. Effects of the inclusiveness of the decision‐making procedure.

Additional analysis: How do political and institutional costs interact?

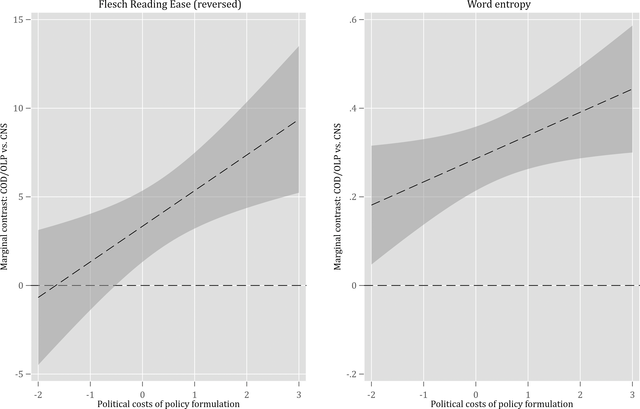

Thus far, we assumed that political and institutional costs are independent of each other. But does the effect of procedural inclusiveness also vary depending on the preference distribution we find in the Commission? One might argue that when a cabinet is highly unified around a moderate median, high institutional costs of policy formulation imposed by the shadow of an inclusive decision‐making process should have a lower marginal impact on the complexity of the agreed‐upon policy compromise than when the cabinet's preference distribution is both biased and heterogeneous, that is, when high institutional costs meet high political costs. In this latter scenario, the institutional costs of policy formulation might amplify the impact of the political costs.

To test this conjecture, I first calculate a term that adds the standardized absolute value of the median Commissioner and the standardized value of preference heterogeneity. The resulting measure increases as preference bias and heterogeneity increase jointly and assumes its lowest values when the cabinet is unified around a moderate median. I then interact this variable with the decision‐making procedure and estimate the marginal contrasts of the two main procedures of interest as the political costs of policy formulation increase. Figure 7 displays the results of this exercise.

Figure 7. Interactive effects of political and institutional costs.

The data indicate that an inclusive decision‐making process impacts most strongly on the complexity of the Commission's policy proposals when the Commission faces high political costs of formulation. When Commissioners are unified behind a moderate median, the readability of policy proposals adopted under consultation cannot be distinguished from those adopted under co‐decision/OLP statistically, while word entropy is slightly higher. As the median moves to the extremes and preferences become more diverse, the impact of the institutional costs increases. Substantively, the contrast in textual difficulty between co‐decision/OLP and consultation amounts to 9.4 FRE points when the political costs of decision making are their empirical maximum. For semantic diversity, the difference amounts to 0.44 bits of word entropy.

Accordingly, cabinets draft their policy proposals in a more complex language when they face a bicameral, instead of a unicameral decision‐making situation and the magnitude of the effect hinges on the cabinet‐internal costs of policy formulation. This finding complements earlier studies which have shown that the Commission's quality of legislative anticipation is severely constrained when the EP is involved under co‐decision/OLP (Rauh, Reference Rauh2021; Laloux & Delreux, Reference Laloux and Delreux2021). Accordingly, we can conclude that the Commission is responsive to pressures induced by the EU's institutional framework at the policy formulation stage.

Conclusion

Contemporary democratic political systems are confronted with increasingly complex governance challenges, to which they often respond with solutions of widely varying complexity and the degree of this complexity likely matters for the perception, acceptance and ultimately the effectiveness of public policies (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Limberg et al., Reference Limberg, Steinebach, Bayerlein and Knill2021). This study provided first insights into the institutional and political origins of complex policies, focusing on the policy formulation stage in the political system of the EU.

Building on a dataset on the texts of 1771 policy proposals adopted by the Commission between 1994 and 2021, the study showed that the Commission increases the complexity of its policy proposals when it faces an inclusive decision‐making process and when preference bias and heterogeneity increase within its central decision‐making body, the CoC. Accordingly, the Commission is not only responsive to functional requirements imposed by the addressed policy areas, but also to institutional and political scope conditions. Even after controlling for time trends, policy area characteristics and legal requirements, we find a clear, significant and robust impact of political institutions, preference bias and heterogeneity on the complexity of the policy proposals adopted by the EU executive.

While the study makes a general argument on how political and institutional costs of policy formulation affect the complexity of policy outputs, the study also yields a range of implications for EU scholarship in particular. First, it underscores that the Commission should be seen as a political body that is responsive both to internal political disagreement and the wider institutional environment when it formulates its policy proposals. Second, the findings provide some indications that partisan preferences might be more important for decision making in the Commission than previously thought and accordingly, the widespread notion of a ‘non‐partisan’ (Manow et al., Reference Manow, Schäfer and Zorn2008, p. 22) Commission should be revisited critically. At the very least, we should no longer ignore the Commission if we are interested in determining ‘Europe's party‐political centre of gravity’ (Manow et al., Reference Manow, Schäfer and Zorn2008). Third, the study suggests that the Commission anticipates the inclusiveness of the legislative process by enhancing the complexity of its policy proposals, which highlights an important and hitherto unknown, strategic element in the EU's agenda‐setting process. Finally, while pundits, politicians and the people have often criticized the EU for excessively complex policy outputs, this study suggests that the political and institutional factors that promote complex policies are not particular to the EU, but can be found in any democratic political system in the world.

The article's findings suggest a variety of important follow‐up questions. First, it is still unclear how the complexity of the initial policy proposal evolves after the policy formulation stage. Some studies have investigated how institutional and political factors influence the degree to which the Commission's proposals are changed by the other legislative institutions (Rauh, Reference Rauh2021; Cross & Hermansson, Reference Cross and Hermansson2017; Laloux & Delreux, Reference Laloux and Delreux2021). Future studies could add to this line of research by exploring the extent to which changes in text similarity imply changes in policy complexity. Second, this study only focused on a narrow set of institutions and defined preference bias and heterogeneity exclusively along the left/right axis. In future research, it might be instructive to disaggregate preferences to individual policy dimensions or investigate the potential impact of other institutional factors, like federal vs. unitary structures, party systems, different types of executive‐legislative relations, or voting rules. For these latter efforts, however, we require cross‐sectional and comparative research designs, as well as complexity data that can be compared across national legal systems. Finally, the argument presented in this article rests on the assumption that policy formulation processes are independent. We know that this assumption is not always warranted and that package deals do exist. While this article did not disentangle these interdependencies, it might be worthwhile to investigate trade‐offs in complexity across policy proposals as a next step.

To what extent can we generalize the findings of this study to other political systems? In some ways, the CoC differs from typical national governments. In particular, the way its members are appointed and the extent to which it enjoys support in the legislative institutions is rather special. Unlike the Commission, national governments in parliamentary systems often have own working majorities in legislative chambers and they are typically composed of much fewer than 27 political parties. Yet, also at the national level, we often find second legislative chambers that do not necessarily reflect the preferences of the national government and we often find significant disagreement among coalition partners when policy compromises are negotiated. The current German government, which has to seek consensus with the opposition in the Bundesrat on some, but not all, of its policy proposals and which now consists of three political parties with distinct ideological profiles is a case in point. If the argument presented in this paper can be generalized, we should see an increase in the complexity of policy proposals in Germany due to increased political and institutional costs of policy formulation. Accordingly, despite its empirical focus on the EU, the article's general argument on the relevance of institutional and political costs of policy formulation for the complexity of policy outputs is adaptable to any democratic political system in the world, where policy formulation is mostly a task of the executive. While the way the Commission is selected and composed is special, this study suggests that the way it operates politically resembles the typical patterns of intra‐coalitional and inter‐institutional politics we find elsewhere. In fact, the general logic behind the paper's argument should, in theory, be transferable to any situation in which a collegial decision‐making body needs to agree on a compromise. In principle, the empirical variety of such decision‐making bodies is very broad and ranges from national governments to sports associations or universities. Accordingly, this study is also an invitation to scholars of comparative politics and comparative public policy to study whether the identified patterns travel to other empirical contexts. This is a particularly promising endeavour against the background that given its technocratic reputation, the Commission is clearly a least‐likely case to observe the effects hypothesized in this study. If we observe partisan preferences to make a difference for policy formulation processes inside the Commission, these effects are likely to be even more pronounced in other contexts where degrees of political conflict are generally higher to begin with.

On a general level, the study's findings imply that to some degree, complex policy compromises are the price of inclusive, democratic decision making. Whenever we criticize excesses in policy complexity, we should therefore bear in mind that complex policies are likely complex for a reason. To paraphrase U.S. author Henry Louis Mencken (Reference Mencken1920, p. 158): for every complex problem, there is a solution that is clear, simple and wrong. More complex policy formulations might sometimes be needed to make a law more just, more precise or even more effective. And very often, it might just be the case that a complex policy is broadly considered better than having no policy at all. This might be particularly true for consensus democracies, and especially for the EU, where the normative goals of consensus and compromise are deeply enshrined into the DNA of the political system (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). Yet, the institutional and political costs of policy formulation vary greatly across the democratic political systems of the world and this study can only be considered a first step in a broader, comparative research program that explores the origins of complex policies on a global scale.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my four anonymous reviewers for their challenging and constructive comments, which have helped to improve the article considerably. Moreover, I am indebted to Christian Rauh, Christoph Knill, Yves Steinebach, Maximilian Haag, and Constantin Kaplaner, who provided me with highly useful comments on very early versions of this paper. This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Grant number 407514878.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix