Introduction

CHD outcomes have significantly improved in the past few decades, especially in developed regions of the world. 1 As more individuals with CHD survive into adulthood, the number of patients at risk for long-term adverse outcomes continues to rise. Reference Best and Rankin2 A major goal of long-term follow-up is to identify patients at risk of adverse events and intervene prior to developing morbidity or mortality. Exercise capacity has been shown in adult studies to predict mortality in heart failure patients and those with various CHD diagnoses. Reference Myers, Arena and Dewey3–Reference Giardini, Specchia and Tacy6

A major limitation in assessing exercise capacity in paediatric CHD patients lies in interpreting fitness data in the presence of wide variability in underlying pathophysiology, comorbidities, and exercise testing protocols used to measure cardiorespiratory fitness. Reference Amedro, Gavotto and Guillaumont7,Reference van Genuchten, Helbing and Ten Harkel8 Patients with univentricular hearts following Fontan palliation have cardiorespiratory fitness as measured by peak aerobic capacity that is 60–70% of a reference cohort without CHD, Reference Atz, Zak and Mahony4,Reference Bossers, Helbing and Duppen9–Reference Wolff, van Melle and Bartelds12 while patients with transposition of the great arteries status post arterial switch operation have peak aerobic capacity around 80–90%. Reference Kuebler, Chen, Alexander and Rhodes13 It is recommended to interpret cardiopulmonary exercise testing data within the context of a particular CHD diagnosis; Reference Burstein, Menachem and Opotowsky14 however, diagnosis-specific reference values are limited for children and adolescents with CHD. Utilising adult CHD reference values may inaccurately characterise a paediatric patient’s exercise capacity due to the physiologic increase in exercise capacity during early adolescence and an accelerated decline in exercise capacity in adults with certain subsets of CHD. Reference Raghuveer, Hartz and Lubans15–Reference Kuebler, Chen, Alexander and Rhodes18

Recently, studies by Van Genuchten and Amedro and colleagues created lesion-specific cardiorespiratory fitness percentile charts. Reference Amedro, Gavotto and Guillaumont7,Reference van Genuchten, Helbing and Ten Harkel8 They showed that peak aerobic capacity for the CHD cohort was lower than that of an age- and sex-matched control cohort without CHD, and that cardiorespiratory fitness varied based on the specific CHD lesion. Reference van Genuchten, Helbing and Ten Harkel8 Since both studies were performed on a cycle ergometer, which has been demonstrated to yield lower peak aerobic capacity values when compared to cardiopulmonary exercise testing performed on a treadmill, Reference Raghuveer, Hartz and Lubans15 there exists a knowledge gap in cardiorespiratory fitness percentiles for paediatric patients with CHD who performed cardiopulmonary exercise testing via treadmill. Additionally, although studies have shown a gradual decline in cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with CHD, Reference Amedro, Gavotto and Guillaumont7,Reference Muller, Ewert and Hager17 there are no studies to our knowledge documenting the changes in peak aerobic capacity during early to late adolescence for individual CHD lesions.

Thus, the primary aim of our study was to characterise the exercise capacity and cardiopulmonary exercise testing performance of a contemporary cohort of paediatric patients with various CHD diagnoses who underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing via a treadmill protocol. We also aimed to create diagnosis-specific percentiles and characterise the association between age and exercise capacity across the paediatric and adolescent years to provide a comparison metric for more accurate interpretation of objectively obtained exercise capacity.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of cardiopulmonary exercise testing data from a single paediatric tertiary care hospital from 2004 to 2022. Demographic data and clinical history were obtained through the cardiopulmonary exercise test and a review of the electronic medical record. Patients with CHD were categorised based on their primary cardiac lesion. Patients with more than one cardiac lesion were characterised by the most haemodynamically significant lesion. Cardiopulmonary exercise tests were obtained during routine clinical follow-up. We included all patients with CHD aged 6–18 years who had a maximal effort cardiopulmonary exercise test defined by a respiratory exchange ratio of ≥1.10. Our cardiopulmonary exercise testing laboratory performs cardiopulmonary exercise tests on both treadmill and cycle ergometers; however, all cardiopulmonary exercise tests included in the current analyses were performed on a treadmill using the Bruce protocol. Only patients with repaired CHD via cardiothoracic surgery or catheter-based intervention were included in this study. Patients with unrepaired CHD of all severity were excluded. Several CHD groups were combined (e.g. atrial and ventricular septal defects), and some were not included (e.g., Ebstein’s anomaly and atrioventricular septal defect) as they were too small to analyse individually.

Optimal interventional techniques for CHD have steadily evolved over the past half-century. As the primary aim of our study is to create exercise capacity percentiles for a contemporary cohort of CHD patients, certain historical interventions were excluded. Thus, single ventricle patients following Fontan palliation were only included if they had a lateral tunnel or extracardiac Fontan as their initial Fontan operation. Patients with an atriopulmonary Fontan or a Fontan conversion were excluded. In addition, patients with transposition of the great arteries were included if their definitive repair was an arterial switch or Rastelli operation. Transposition of the great arteries patients who had an atrial switch were excluded. There were no other exclusion criteria.

The resting heart rate was the baseline heart rate obtained in the supine position prior to exercise. The peak heart rate was the highest heart rate achieved during the cardiopulmonary exercise test. Percent of age-predicted maximal heart rate (%) was obtained by dividing the maximal heart rate achieved during cardiopulmonary exercise testing by the predicted maximal heart rate for age via the following equation: maximum heart rate achieved (bpm)/(208 – [0.7 * age]) × 100. Reference Tanaka, Monahan and Seals19 The parameters of exercise capacity recorded for every cardiopulmonary exercise test included exercise duration (min), peak aerobic capacity indexed to weight (mL/kg/min), and percentage of expected peak aerobic capacity (%). The percentage of expected peak aerobic capacity was calculated as the percent of age- and sex-specific value representing the 50th percentile for each individual patient and was previously derived from Bruce Protocol testing with objectively confirmed maximal effort. Reference Griffith, Wang, Liem, Carr, Corson and Ward16,Reference Griffith, Wang, Liem, Carr, Corson and Ward20 This approach was utilised as there are currently no available paediatric- or adolescent-specific peak aerobic capacity prediction equations derived from treadmill-based cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Other often cited cycle ergometer and treadmill-based equations are pre-test predictive equations, as they do not include data from the cardiopulmonary exercise test. Reference Cooper and Weiler-Ravell21–Reference Blanchard, Blais and Chetaille23 Thus, our estimated peak aerobic capacity values represent the most appropriately representative age- and sex-matched data in the literature.

The 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles for the percentage of expected peak aerobic capacity achieved for each diagnosis category were calculated. Diagnosis-specific peak aerobic capacity data were then displayed via histograms, which graphically illustrate these diagnosis-specific fitness percentiles for each patient group. The relationship between age and percent expected peak aerobic capacity was plotted for each diagnosis category, with the cubic trend line included to characterise fitness during the paediatric and adolescent years. Since all percent expected peak aerobic capacity data were analysed in the context of age- and sex-matched fitness reference standards, data are presented by each diagnostic category and not by age- or sex-based sub groups. Data were plotted for ages 10–18 years, as the number of patients below age 10 was minimal, leading to potentially inappropriate extrapolations of the trend line into the younger years. The 95% confidence intervals were also included. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 29.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

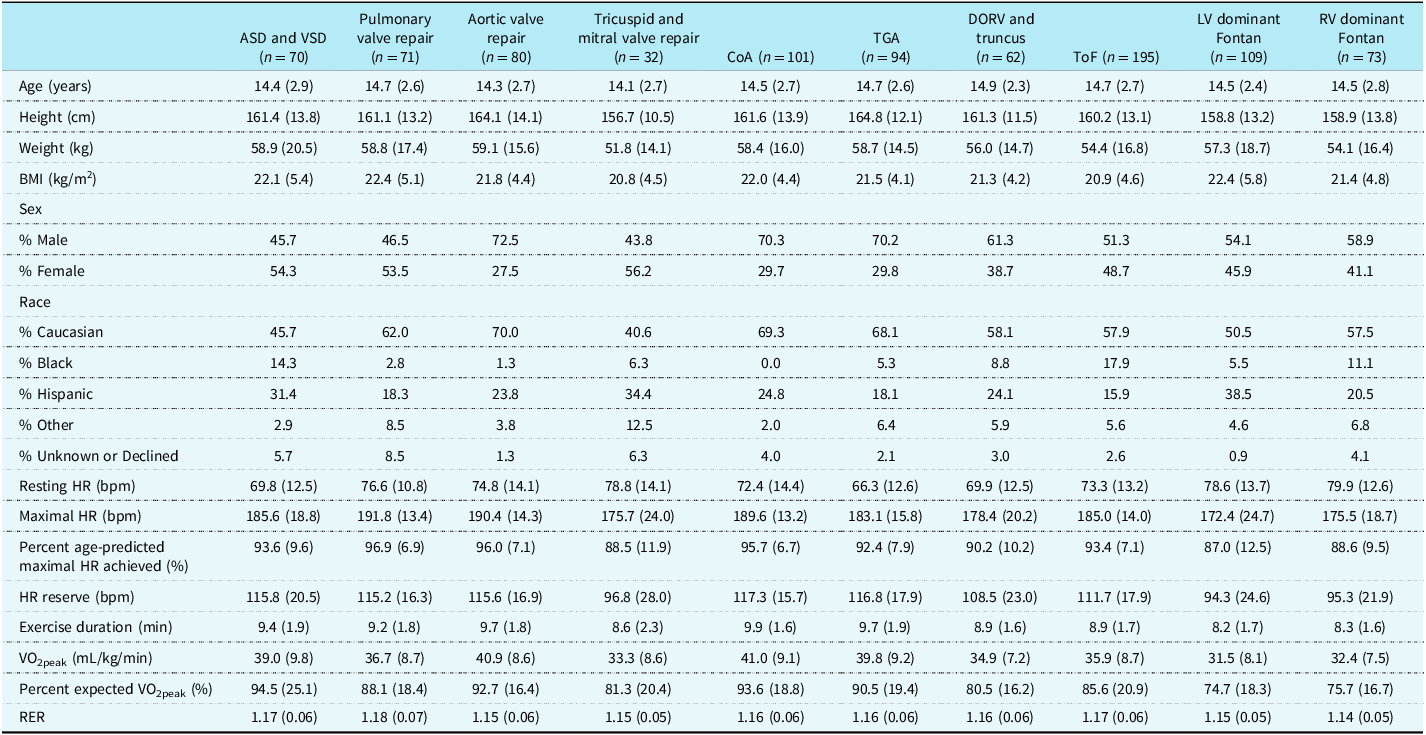

A total of 887 cardiopulmonary exercise tests were included in analyses. Patient diagnoses were classified as atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect, pulmonary valve repair, aortic valve repair, tricuspid and mitral valve repair, coarctation of the aorta, transposition of the great arteries, double outlet right ventricle or truncus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, left ventricle dominant Fontan, and right ventricle dominant Fontan (Table 1). The average age of the entire cohort was 14.6 ± 2.6 years, and 57.9% of cardiopulmonary exercise tests were performed in male patients. The mean height of the entire cohort was 161.0 ± 13.2 cm and the mean weight was 56.8 ± 16.8 kg. The majority (58.4%) of patients were White, 23.9% of patients were Hispanic, and 8.7% of patients were Black.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics and cardiopulmonary exercise testing profile of study participants

Data are Mean (SD). ASD = atrial septal defect; VSD = ventricular septal defect; CoA = coarctation of the aorta; TGA = transposition of the great arteries; DORV = double outlet right ventricle; ToF = tetralogy of Fallot; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

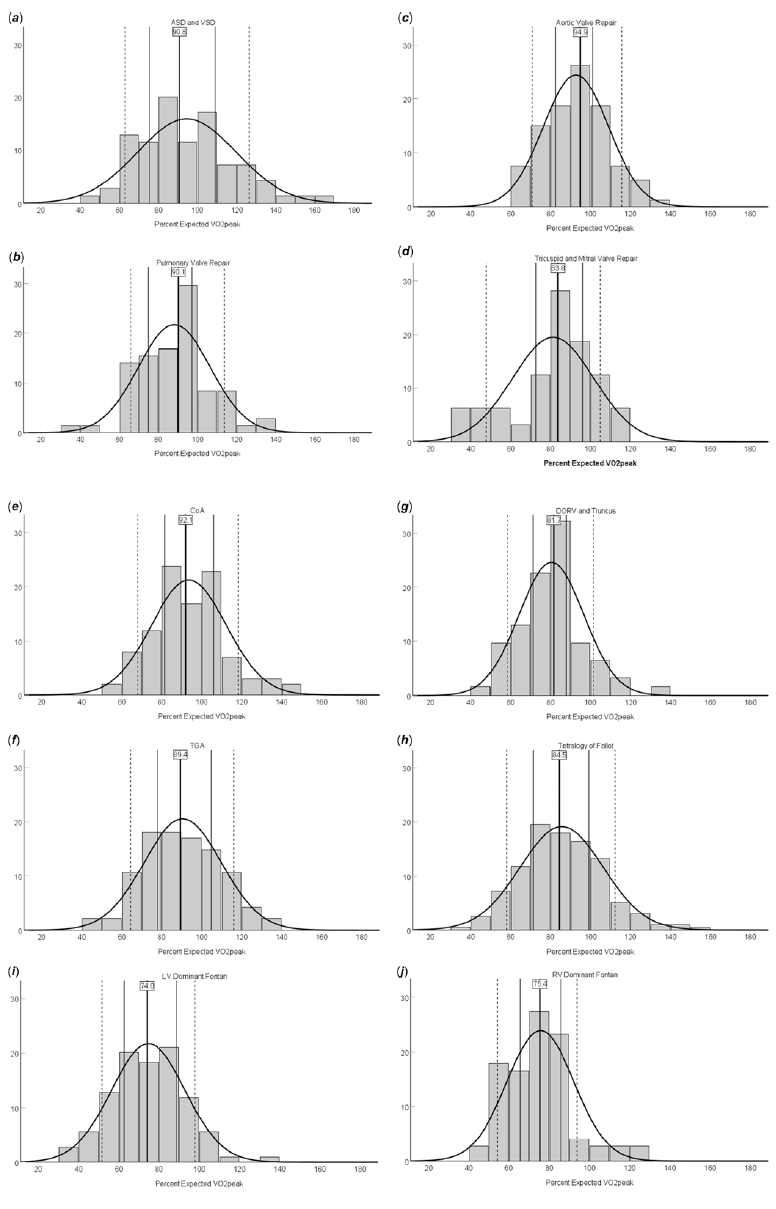

The average peak aerobic capacity of our entire cohort was 36.7 ± 9.2 mL/kg/min, and the mean respiratory exchange ratio for the total study sample was 1.16 ± 0.06, confirming maximal effort during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. We found significant variations in exercise capacity based on the type of CHD lesion. The single ventricle cohorts had the lowest peak aerobic capacity at 31.5 ± 8.1 mL/kg/min and 32.4 ± 7.5 mL/kg/min for left ventricle and right ventricle dominant Fontan patients, respectively (Table 1). The highest peak aerobic capacity was found in our aortic valve repair, coarctation of the aorta, and transposition of the great arteries cohorts (40.9 ± 8.6, 41.0 ± 9.1, and 39.8 ± 9.2 mL/kg/min, respectively). The range of percent expected peak aerobic capacity for the CHD cohorts also varied from 74.7 ± 18.3% for left ventricle dominant Fontan to 94.5 ± 25.1% in the atrial septal defect/ventricular septal defect group. We found patients reached an average of 92.5 ± 9.3% of age-predicted maximal heart rate, and the average duration on the Bruce protocol was 9.1 ± 1.8 minutes. There also existed a range of age-predicted maximal heart rate achieved, ranging from 96.9 ± 6.9% for pulmonary valve repair to 87.0 ± 12.5% for left ventricle dominant Fontan patients. The complete cardiopulmonary exercise testing profiles for each patient diagnosis category are provided in Table 1. Sex-based analyses of exercise testing results for each diagnostic group are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile values for percent expected by peak aerobic capacity for each CHD category are shown in Table 2. Diagnosis-specific distributions of the percentage of expected peak aerobic capacity and corresponding percentile values are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagnosis-specific distributions of percent expected VO2peak and corresponding percentile values. Data are shown as percentage of each patient cohort. (a) ASD and VSD. (b) Pulmonary valve repair. (c) Aortic valve repair. (d) Tricuspid and mitral valve repair. (e) CoA. (f) TGA. (g) DORV and truncus. (h) ToF. (i) LV dominant Fontan. (j) RV dominant Fontan. Solid bold lines represent the median (with the median value directly listed), solid lines represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and dotted lines represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. The x-axes represent percent expected VO2peak achieved, and y-axes represent percentage of patients within each diagnosis category in each histogram bar.

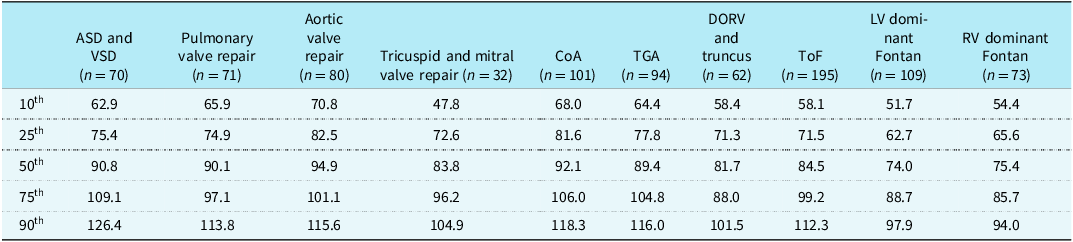

Table 2. Percentiles of percent expected VO2peak achieved for each diagnosis category

ASD = atrial septal defect; VSD = ventricular septal defect; CoA = coarctation of the aorta; TGA = transposition of the great arteries; DORV = double outlet right ventricle; ToF =tetralogy of Fallot; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle.

Scatterplots of percent expected peak aerobic capacity compared to age were created for all CHD lesions and are shown in Figure 2. The average trendline in cardiorespiratory fitness was above the 80th percentile for all cardiac lesions in early adolescence. Single ventricles and tricuspid or mitral valve repair showed a gradual decline in percent expected peak aerobic capacity starting in mid-adolescence and crossed below the 80th percentile mark in late adolescence. There was overall stable exercise capacity in early adolescence, although tetralogy of Fallot and Fontan patients trended towards a decline in later adolescence.

Figure 2. Changes in percent expected VO2peak across the paediatric and adolescent years in each diagnosis category. (a) ASD and VSD. (b) Pulmonary valve repair. (c) Aortic valve repair. (d) Tricuspid and mitral valve repair. (e) CoA. (f) TGA. (g) DORV and truncus. (h) ToF. (i) LV dominant Fontan. (j) RV dominant Fontan. The red dotted line represents 80% of percent expected VO2peak used to characterise cardiorespiratory deconditioning. The black bold line represents the cubic line of best fit, and the black dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This study represents one of the largest analyses of treadmill-derived and objectively measured peak aerobic capacity in paediatric and adolescent CHD patients to date. Our primary results include the development of lesion-specific peak aerobic capacity values for a contemporary CHD cohort based on treadmill-based exercise testing via the Bruce Protocol. Furthermore, we have illustrated age-related and diagnosis-specific trends in fitness for these paediatric and adolescent cardiac patients undergoing routine cardiopulmonary exercise testing for clinical care and follow-up.

We found that, as a cohort, children with CHD had a mean percent expected peak aerobic capacity of 85.9 ± 20.4% when compared to 50th percentile values for age- and sex-matched peers without CHD, representing low-normal cardiorespiratory fitness. Reference Griffith, Wang, Liem, Carr, Corson and Ward24 Importantly, VO2peak prediction equations specifically for paediatric patients based solely on non-exercising patient parameters have not yet been established for treadmill-based fitness measurement. Rather, existing non-exercising equations have been developed using cycle ergometry, Reference Cooper and Weiler-Ravell25 which has been demonstrated to yield a lower VO2peak when compared to treadmill-derived values. Reference Turley, Rogers, Harper, Kujawa and Wilmore26 This makes application of such cycle ergometry-derived prediction equations to data collected from the Bruce Protocol inadvisable. Therefore, our approach of comparing objectively measured fitness with median values from established reference standards using a representative cohort is a reasonable strategy when analysing fitness in this paediatric population.

The mean exercise duration for our repaired CHD cohort was also lower than the mean exercise duration for our previously published cohort without CHD. Reference Griffith, Wang, Liem, Carr, Corson and Ward20 The median value for percent expected by peak aerobic capacity in atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect patients was above 90%, while patients with univentricular hearts achieved approximately 75% of expected values. This distribution highlights the need for appropriately representative reference standards to facilitate contextualised interpretation of cardiopulmonary exercise tests. Further, these data support the incorporation of aerobic exercise training with the specific goal of improving cardiorespiratory fitness across the various patient populations represented in these analyses, as increased peak aerobic capacity has been linked with improved outcomes. Reference Fernandes, Alexander and Graham27,Reference Egbe, Driscoll and Khan28

The average indexed peak aerobic capacity (mL/kg/min) for various CHD categories in our study is higher than that of adult studies Reference Kempny, Dimopoulos and Uebing29–Reference Cunningham, Nathan, Rhodes, Shafer, Landzberg and Opotowsky31 and similar to those published in paediatric cohorts. Reference Amedro, Gavotto and Guillaumont7,Reference van Genuchten, Helbing and Ten Harkel8 Analysis of the trend in fitness across the paediatric and adolescent years in these CHD patients suggests that exercise capacity is maintained in early adolescence. There is an apparent reduction in exercise capacity (defined by percent of expected by peak aerobic capacity) during the late adolescent years in patients with complex CHD, including those with tetralogy of Fallot, double outlet right ventricle, tricuspid and mitral valve repair, and following single ventricle palliation. This observation is consistent with prior studies showing a decline in exercise capacity in patients with complex CHD starting in mid to late adolescence. Reference Muller, Ewert and Hager17,Reference Egbe, Driscoll and Khan28,Reference Atz, Zak and Mahony30,Reference Egbe, Khan and Miranda32,Reference Giardini, Hager, Pace Napoleone and Picchio33 Prior studies have shown differences in body composition with single ventricle patients having more fat mass and less lean muscle mass compared to their age- and sex-matched peers. Reference Griffith, Wang, Liem, Carr, Corson and Ward24 Thus, we suspect the reduction in percent of expected peak aerobic capacity is partially due to a decrease in lean muscle mass development during puberty as well as gradual declines in cardiopulmonary efficiency. Reference Shafer, Opotowsky and Rhodes34 The trend of diminishing exercise capacity, even compared to peers with the same exercise duration, suggests that routine cardiopulmonary exercise testing for surveillance in paediatric cardiology patients should be started prior to adolescence. Patients with complex cardiac diagnoses may benefit from more frequent cardiopulmonary exercise testing to track changes longitudinally and determine if cardiac rehabilitation or other interventions may be indicated. Reference Cifra, Cordina and Gauthier35

The strengths of this study included the large overall sample size, with 887 paediatric and adolescent cardiopulmonary exercise tests representing the largest known analysis of treadmill-derived cardiorespiratory fitness in this patient population. Furthermore, peak aerobic capacity data were objectively obtained and confirmed to be maximal effort. These treadmill-derived data may better represent the daily ambulatory activities of these patients and may be more directly representative of capacity during activities of daily living than cycle ergometry-derived data. Finally, we excluded patients with historical CHD repairs, such as atriopulmonary Fontan and atrial switch procedure, to create a more contemporary and representative cohort of adolescent patients with CHD.

While this study represents a significant step in the direction of improved understanding of exercise capacity in paediatric cardiology patients with repaired CHD, it is not without limitations. These include relatively small sample sizes for certain diagnosis categories. Analysis of relationships between age and cardiopulmonary exercise testing variables in the patient groups with relatively small sample sizes should be viewed as preliminary, and additional research is warranted in this area to provide age- and sex-specific CHD reference values. Further, sex-based analyses should be performed as more CPET data become available, as such findings may contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of fitness data in these populations and continue to inform treatment approaches. The inclusion of all cardiopulmonary exercise tests and our institution being a tertiary referral centre may lead to selection bias. We did not have data on patient medications during the cardiopulmonary exercise test, and certain medications, such as β-blockers, may have a negative effect on exercise capacity. Reference Ladage, Schwinger and Brixius36 We also did not exclude patients who may have genetic or extracardiac conditions that could limit exercise capacity. Future studies should include additional measured metabolic indices such as ventilatory efficiency, oxygen uptake efficiency slope, and spirometry data to better understand the pulmonary and ventilatory contributions to exercise capacity in paediatric patients with repaired CHD. Additionally, larger future analyses will benefit from larger data sets, facilitating the creation of reference standards based on age- and sex-specific indexed VO2peak (in mL/kg/min), as these data will be important for clinicians performing and interpreting these tests. Lastly, studies investigating the longitudinal relationships between fitness and clinical outcomes are required to both explore the prognostic ability of impaired exercise tolerance and to guide targeted aerobic exercise interventions.

This study provides clinicians with diagnosis-specific peak aerobic capacity reference standards for contemporary paediatric patients with repaired CHD undergoing treadmill cardiopulmonary exercise testing. This represents an improvement in the resources available to clinicians and allows providers to more accurately characterise cardiorespiratory fitness. This study also characterised the association between age and fitness, helping to inform clinicians regarding the frequency of ordering cardiopulmonary exercise testing based on specific CHD diagnoses.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951125111268

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and have been approved by the institutional review board of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.