1. Introduction

Sedimentary basins are Earth’s natural archive, preserving evidence of past landscapes, surface processes and internal dynamics across various geological timescales. By analysing sedimentary successions that have accumulated over time, provenance shifts can be identified, giving insights into evolving tectonic systems and the specific palaeoclimatic conditions that influenced basin development (Weltje & von Eynatten, Reference Weltje and von Eynatten2004; Caracciolo, Reference Caracciolo2020). Additionally, changes in sediment routing pathways can constrain geomorphological changes across vast regions, for instance, orogenic uplift, subsidence and erosion (Caracciolo et al. Reference Caracciolo, Ravidà, Chew, Janßen, Lünsdorf, Heins, Stephan and Stollhofen2021; Pastore et al. Reference Pastore, Baird, Vermeesch, Bristow, Resentini and Garzanti2021).

Heavy-mineral analysis (HMA), widely used in sandstone provenance, helps to discriminate source-rocks, alongside their specific compositions and depositional settings (Morton & Hallsworth, Reference Morton and Hallsworth1994; Garzanti & Andò, Reference Garzanti and Andò2019). Heavy minerals are normally abundant in most siliciclastic sediments, allowing for easy extraction and measurement (Mange & Maurer, Reference Mange and Maurer1992). HMA is a straightforward method for identifying changes in the type, size, shape and appearance of heavy minerals through the rock record. It is a key first-order provenance tool that is often applied prior to other more complex single-grain approaches (e.g., geochronology or trace element geochemistry). In addition, automated techniques for quantitative HMA allow for rapid measurement, thus increasing numbers of analysed minerals by orders of magnitude and improving data robustness (Lünsdorf et al. Reference Lünsdorf, Lünsdorf, Újvári, Dunkl, Wolfram, Hobrecht, Laake and von Eynatten2023; Dröllner et al. Reference Dröllner, Barham, Kirkland, Zametzer and Schulz2025). Although heavy minerals reflect parent rock mineralogy, various processes during erosion, transport and deposition may or may not alter their relative abundances, that is, chemical weathering causing selective mineral dissolution (Velbel, Reference Velbel, Mange and Wright2007; Andò et al. Reference Andò, Garzanti, Padoan and Limonta2012), grain-size inheritance from the source rock (Feil et al. Reference Feil, von Eynatten, Dunkl, Schönig and Lünsdorf2024), hydrodynamic processes and selective grain sorting (Garzanti, Andò & Vezzoli, Reference Garzanti, Andò and Vezzoli2008, Reference Garzanti, Andò and Vezzoli2009), or burial diagenesis leading to intrastratal solution (Turner & Morton, Reference Turner, Morton, Mange and Wright2007; Garzanti et al. Reference Garzanti, Andò, Limonta, Fielding and Najman2018).

Alongside HMA, single-grain analysis of detrital minerals offers detailed information on source rock characteristics, including assigning a metamorphic grade where relevant, and geochronological insights, which allow quantitative identification of grains from actively exhuming basements, overcoming the challenge of recycled sedimentary material (von Eynatten & Dunkl, Reference von Eynatten and Dunkl2012). Apatite and garnet, selected for their near-ubiquitous presence in igneous and metamorphic rocks, are valuable minerals for provenance analysis due to their wide compositional variability which is dependent on specific petrogenetic conditions of host rocks (Krippner et al. Reference Krippner, Meinhold, Morton and von Eynatten2014; O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020). For garnet, major-element chemistry was used as input for a random forest classifier which discriminates garnets first into host-rock setting (mantle, metamorphic, igneous, or metasomatic), and then, where applicable, metamorphic facies (Schönig et al. Reference Schönig, von Eynatten, Tolosana-Delgado and Meinhold2021). Similarly, apatite trace element compositions vary across diverse bedrock types and have been categorized into seven principal categories using a support vector machine (SVM) approach (O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020). In conjunction with apatite trace element analysis, apatite U–Pb thermochronology is another key tool in single-grain provenance analysis, especially as both methods can be applied simultaneously. The U–Pb apatite system has a partial retention zone (i.e., closure temperature) of ∼350–570 °C for geologically typical grain sizes and cooling rates, providing thermochronological constraints on exhumation from middle- to lower-crustal levels (Chew & Spikings, Reference Chew and Spikings2021).

The Calabrian Arc, situated in southern Italy, represents a complex convergent-margin orogen, where subduction, arc-continent accretion and slab-rollback-driven extension have interacted to produce a highly dynamic and complex tectonic environment. Its northern sector consists of an Alpine-age (i.e., Cenozoic) nappe stack which underwent high pressure-low temperature metamorphism (HP-LT), a rather complete crustal section of Variscan crystalline basement, and some Mesozoic to Cenozoic sedimentary cover (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). The central Calabria Massif is a distinct topographic high made up of an allochthonous segment of western Variscan crust. Structurally below and geographically towards the W/NW are Mesozoic oceanic units (Liguride Complex) and carbonate platform deposits (Apennine Complex; Fig. 1). Along the eastern Ionian margin of northern Calabria, a series of Neogene forearc basins (Rossano, Cirò, Crotone and Catanzaro) record the evolution of the Calabrian Arc. Previous work on the provenance and evolution of these basin sediments has primarily focused on sandstone petrography and sequence stratigraphy (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008; Muto et al. Reference Muto, Spina, Tripodi, Critelli and Roda2014; Robustelli & Muto, Reference Robustelli and Muto2017; Ortolano et al. Reference Ortolano, Visalli, Fazio, Fiannacca, Godard, Pezzino, Punturo, Sacco and Cirrincione2020; Zecchin et al. Reference Zecchin, Civile, Caffau, Critelli, Muto, Mangano and Ceramicola2020), while studies incorporating HMA and single-grain varietal techniques remain notably limited. Although late Oligocene to Miocene exhumation of the Sila Massif is constrained via AFT and AHe dating (Thomson, 1994; Olivetti et al. Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017; Gallen et al. Reference Gallen, Seymour, Glotzbach, Stockli and O’Sullivan2023), the reconstruction of uplift and the development of the sediment supplying topography remain incomplete.

Figure 1. (a) Geological map of northern Calabria. Major cities marked by a red square. Sample locations and their associated basins marked with filled coloured circles. The main lithologies and their associated unit/ formation are provided in tectono-stratigraphic order (from lowest/oldest at the bottom to uppermost/youngest at the top). (b) W–E section from A to A’ across northern Calabria cutting through the Coastal Chain, Crati Valley, Sila Massif and Rossano basin. Modified from Brandt & Schenk (Reference Brandt and Schenk2020) and Vitale et al. (Reference Vitale, Ciarcia, Fedele and Tramparulo2019a) and references therein.

In this study, we present a regional example of how a multi-proxy (non-zircon-based) provenance study provides new insights into changing source-to-sink patterns within a complex supra-subduction setting, an approach that can be readily applied to other regions, tectonic regimes and basin systems. In addition, it provides a nice case study for orogenic divide migration (e.g., Mark, Cogné & Chew, Reference Mark, Cogné and Chew2016; He et al. Reference He, Braun, Tang, Yuan, Acevedo-Trejos, Ott and Stucky de Quay2024), enabled by mineralogically and geochronologically different proximal and distal rocks. Overall, the region offers a superb natural laboratory for reconstructing source-to-sink relationships and deciphering the geomorphological evolution of an active forearc system.

2. Geological background

The region of northern Calabria, at the southern peninsula of Italy, records a long and complex geological history. Bordered by the Ionian oceanic basin to the east, the Tyrrhenian backarc basin to the west and the Apennine and Maghrebide thrust belts to the north and south, Calabria is a tectonically active region with the strongest seismicity in the Apennine chain (Tortorici et al. Reference Tortorici, Monaco, Tansi and Cocina1995; Galli et al. Reference Galli, Spina, Ilardo and Naso2010). From west to east, its main morphological features include the Coastal Chain (Catena Costiera), Crati Valley, Sila Massif and a series of forearc basins (Fig. 1 ). The Coastal Chain comprises an N–S trending horst system bounded eastward by normal faults (Sorriso-Valvo & Sylvester, Reference Sorriso-Valvo and Sylvester1993; Tansi et al. Reference Tansi, Muto, Critelli and Iovine2007; Tansi et al. Reference Tansi, Gallo, Muto, Perrotta, Russo and Critelli2016; Brozzetti et al. Reference Brozzetti, Cirillo, Liberi, Piluso, Faraca, Nardis and Lavecchia2017), while the adjacent Crati Valley represents a complementary N–S extensional graben infilled with Plio–Pleistocene deposits (Tortorici et al. Reference Tortorici, Monaco, Tansi and Cocina1995; Robustelli & Muto, Reference Robustelli and Muto2017). The Sila Massif, an elevated mountainous plateau and the region’s main topographic high, exposes late Variscan crust of the Calabride Complex (Ortolano et al. Reference Ortolano, Visalli, Fazio, Fiannacca, Godard, Pezzino, Punturo, Sacco and Cirrincione2020). A series of N–S trending Neogene–Quaternary basinal successions, marking a transgressive sedimentary infill, rest unconformably along the eastern margin (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008; Muto et al. Reference Muto, Spina, Tripodi, Critelli and Roda2014; Zecchin et al. Reference Zecchin, Praeg, Ceramicola and Muto2015; Zecchin et al. Reference Zecchin, Civile, Caffau, Critelli, Muto, Mangano and Ceramicola2020).

2.a. Major geological units

The geology of Northern Calabria is highly diverse (Bonardi et al. Reference Bonardi, Cavazza, Perrone, Rossi, Vai and Martini2001; Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Variscan continental slices form part of an Alpine nappe stack thrust during the Miocene onto the Apennine carbonate platform system, the structurally lowest complex of northern Calabria (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). This platform, deposited from Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous, represents shallow-water carbonates of the central Tethys Ocean (Cirrincione et al. Reference Cirrincione, Fazio, Fiannacca, Ortolano, Pezzino and Punturo2015; Parente et al. Reference Parente, Amodio, Iannace and Sabbatino2022). The overlying Liguride Complex (Fig. 1b), a Jurassic-early Cretaceous ophiolite-bearing segment of Neo-Tethys oceanic crust (Liberi, Morten & Piluso, Reference Liberi, Morten and Piluso2006), underwent Alpine high pressure-low temperature (HP-LT) metamorphism from 38–33 Ma, based on 39Ar/40Ar data (Rossetti et al. Reference Rossetti, Faccenna, Goffé, Monié, Argentieri, Funiciello and Mattei2001; Vitale et al. Reference Vitale, Ciarcia, Fedele and Tramparulo2019a). It comprises several tectonometamorphic units throughout northern Calabria, including the North-western Diamante-Terranova Unit (Cello, Invernizzi & Mazzoli, Reference Cello, Invernizzi and Mazzoli1996; Fedele et al. Reference Fedele, Tramparulo, Vitale, Cappelletti, Prinzi and Mazzoli2018; Tursi et al. Reference Tursi, Bianco, Brogi, Caggianelli, Prosser, Ruggieri and Braschi2020), characterized by glaucophane–lawsonite metabasalts metamorphosed under blueschist-facies conditions (Vitale et al. Reference Vitale, Fedele, Tramparulo and Prinzi2019b).

Tectonically above is the Calabride Complex, composed of Variscan crustal segments affected by several thrusting cycles leading to the present-day nappe stack (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Its lower part, the Bagni nappe, representing the upper Variscan crust, underwent Alpine greenschist- to lower-amphibolite-facies metamorphism and contains micaschists, quartz-phyllites and actinolite schist (Cirrincione et al. Reference Cirrincione, Ortolano, Pezzino and Punturo2008; Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). The overlying mid-crustal Castagna nappe consists of metapelites and granitic augen gneisses formed under Alpine amphibolite-facies conditions (Schenk, Reference Schenk1990; Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Low-angle thrust faults separate the underlying nappes from the overlying metapelite and Sila Unit. A large unit from the lower Variscan crust dominated by aluminous paragneisses and metabasic rocks with granulite-facies assemblages (Schenk, Reference Schenk1980; Graessner & Schenk, Reference Graessner and Schenk2001).

Lying between the upper and lower Variscan crust is the late Palaeozoic plutonic intrusion of the Sila Batholith, composed mostly of granites and granodiorites, with tonalite, peraluminous granite, diorite and some gabbroic units (Messina et al. Reference Messina, Compagnoni, Vivo, Perrone and Russo1991; Ayuso et al. Reference Ayuso, Messina, Vivo, Russo, Woodruff, Sutter and Belkin1994; Caggianelli, Del Moro & Piccarreta, Reference Caggianelli, Del Moro and Piccarreta1994; Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). The Bocchigliero and Mandatoriccio Units, forming part of the upper Variscan crust above the Sila Batholith (Fig. 1; Barone et al. (Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008), consist of phyllites, metaarenites, metavolcanics and marbles metamorphosed under very-low- to low-grade (sub-)greenschist conditions (Bocchigliero Unit) (Borghi, Colonna & Compagnoni, Reference Borghi, Colonna, Compagnoni, Carmignani and Sassi1992; Acquafredda, Lorenzoni & Lorenzoni, Reference Acquafredda, Lorenzoni and Lorenzoni1994), and paragneisses, porphyroids, porphyritic schists and amphibolites that record low- to medium-grade LP-HT greenschist to amphibolite facies metamorphism (Mandatoriccio Unit) (Fornaseri et al. Reference Fornaseri, Acquafredda, Lorenzoni, Lorenzoni, Barbieri and Trudu e1992; Acquafredda, Lorenzoni & Lorenzoni, Reference Acquafredda, Lorenzoni and Lorenzoni1994; Langone et al. Reference Langone, Godard, Prosser, Caggianelli, Rottura and Tiepolo2010).

Along the eastern and north-eastern Sila Massif, Mesozoic-Cenozoic sedimentary successions unconformably overlie the basement (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). The Mesozoic Longobucco Group (Upper Triassic–Lower Jurassic) comprises continental red beds, platform carbonates and shelf/slope marls, overlain by deep-marine turbidites, forming an unmetamorphosed transgressive sequence of a rifted continental margin (Zuffa, Gaudio & Rovito, Reference Zuffa, Gaudio and Rovito1980; Santantonio & Teale, Reference Santantonio, Teale, Leggett and Zuffa1987; Perri et al. Reference Perri, Cirrincione, Critelli, Mazzoleni and Pappalardo2008).

2.a.1. Neogene formations

Following a period of non-deposition, the early Miocene (Aquitanian) Paludi Formation was unconformably deposited on top of the Jurassic sediments (Longobucco Group) or Variscan basement (Zuffa & de Rosa, Reference Zuffa and De Rosa1978; Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). Interpreted as a Mass Transport Complex (Innamorati et al. Reference Innamorati, Fabbi, Pignatti, Aldega and Santantonio2024), it contains alluvial conglomerates and breccia, grading upwards into marls, siltstones interbedded with calcarenites, turbiditic sandstones and silty marls (Bonardi et al. Reference Bonardi, Capoa, Di Staso, Perrone, Sonnino and Tramontana2005; Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). Along the Ionian margin, a series of Neogene–Quaternary basins, Rossano, Cirò, Crotone and Catanzaro (from north to south), unconformably overlie basement units and preserve transgressive sedimentary sequences (Fig. 2; Zecchin et al. Reference Zecchin, Civile, Caffau, Critelli, Muto, Mangano and Ceramicola2020). Basin infill occurred during several stages throughout the Miocene, with changing sediment sources reflecting the regional tectonic evolution (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). These cyclic basinal sequences begin with alluvial and fan-delta conglomerates, transitioning into a nearshore succession of sandstones, fining upwards to shelf deposits, marls, clays and locally olistostromes (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). Early Messinian evapourites in the Rossano and Crotone basins record regional sea level fall and isolation of the Mediterranean during the Messinian salinity crisis (Borrelli et al. Reference Borrelli, Perri, Avagliano, Coraggio and Critelli2022). The petrographical composition of these pre-Neogene units provides the potential heavy-mineral suites supplying the Miocene forearc basins (Table 1).

Figure 2. Stratigraphy of the Miocene forearc basin of Northern Calabria, with sample positions marked. Note Cirò basin section includes an allochthonous unit (so-called Cariati nappe, Muto et al. (Reference Muto, Spina, Tripodi, Critelli and Roda2014) encompassing Cretaceous to Tortonian strata (samples KB-22B, -23). Adapted from Barone et al. (Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008), Muto et al. (Reference Muto, Spina, Tripodi, Critelli and Roda2014), and Brutto et al. (Reference Brutto, Muto, Loreto, Paola, Tripodi, Critelli and Facchin2016).

Table 1. Mineral suites and associated lithology/facies for each major tectonic unit of Northern Calabria, compiled from literature. General heavy minerals are given in normal font, heavy minerals most relevant for provenance interpretation in the present study are given in bold

2.b. Tectonic evolution

Ongoing north–south directed convergence of the African and Eurasian plates since the Cretaceous led to closure of the Alpine Tethys in the western Mediterranean (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). The offshore Calabrian Arc, an independent tectonic block, splits the Sicilian Maghrebides from the southern Apennines (Bonardi et al. Reference Bonardi, Cavazza, Perrone, Rossi, Vai and Martini2001). Late Oligocene to Miocene south-eastward directed slab rollback drove counterclockwise rotation of the Italian peninsula (Faccenna et al. Reference Faccenna, Piromallo, Crespo-Blanc, Jolivet and Rossetti2004; Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Subduction and convergence led to Miocene emplacement of the Alpine nappe stack onto the Apennine carbonate platform (Fig. 1b) (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Rollback and eventual rifting of the Tyrrhenian backarc basin in the Tortonian led to the formation of extensional basins within the entire Calabrian Arc domain and the detachment of Calabria from the Sardinia-Corsica block (Mattei et al. Reference Mattei, Cipollari, Cosentino, Argentieri, Rossetti, Speranza and Di Bella2002).

2.c. Geochronological and thermochronological review of tectonic units

A compilation of zircon U–Pb ages is detailed in Fornelli et al. (Reference Fornelli, Festa, Micheletti, Spiess and Tursi2020) and yields complex U–Pb zircon populations ranging from the Pre-Cambrian through to the Permian. Protoliths of the Castagna nappe record Ediacaran magmatism (Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Barbey, Fornelli, Piccarreta and Deloule2007), with detrital zircon ages from Sila Massif and Catena Costiera paragneisses, and actinolite schists being mostly Neoproterozoic to Ordovician (452 Ma, 519 Ma, 637 Ma and 722 Ma) with some (<22%) Meso-Paleoproterozoic ages, meanwhile Catena Costiera orthogneisses contain zircons ages peaking in the Cambrian (Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Festa, Micheletti, Spiess and Tursi2020). The Mandatoriccio Unit records Late Mississippian regional amphibolite-facies metamorphism at 326 Ma (Rb/Sr whole-rock dating; Acquafredda et al. Reference Acquafredda, Barbieri, Lorenzoni, Trudu and Zanettin Lorenzoni1992), with detrital zircon U–Pb ages recording Ediacaran-Ordovician (1005 Ma, 622 Ma, 524 Ma and 446 Ma) (Langone & Micheletti, Reference Langone and Micheletti2012; Laurita et al. Reference Laurita, Prosser, Rizzo, Langone, Tiepolo and Laurita2015). The greenschist-facies Bocchigliero Unit records similar regional metamorphism at 330 Ma (Rb/Sr whole-rock dating; Acquafredda et al. Reference Acquafredda, Lorenzoni, Zanettin Lorenzoni, Barbieri and Trudu1991) but zircon U–Pb ages are lacking. The lower-crust Sila-Serre Unit records Ediacaran magmatism (Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Barbey, Fornelli, Piccarreta and Deloule2007; Laurita et al. Reference Laurita, Prosser, Rizzo, Langone, Tiepolo and Laurita2015), with zircon U–Pb ages spanning Paleoproterozoic to Triassic (1784 Ma, 922 Ma, 649 Ma, 556 Ma, 542 Ma and 452 Ma) containing a prevalent Variscan component (321 Ma, 299 Ma and 282 Ma) (Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Barbey, Fornelli, Piccarreta and Deloule2007; Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Langone, Micheletti and Piccarreta2018). The late Variscan intrusion of the Sila Batholith, synchronous with peak metamorphism, is dated to approx. 300 Ma by U–Pb zircon, xenotime and monazite (Graessner et al. Reference Graessner, Schenk, Bröcker and Mezger2000).

Low-temperature thermochronometers have been used to constrain the tectonic evolution of northern Calabria. Zircon and apatite fission track (ZFT and AFT) ages (Thomson, 1994) indicate accelerated basement cooling from 35 to 15 Ma, reflecting regional exhumation and coeval syn-orogenic flysch deposition linked to extensional tectonics and erosion. In the Longobucco area east of the Sila Massif, AFT ages (Vignaroli et al. Reference Vignaroli, Minelli, Rossetti, Balestrieri and Faccenna2012) record an 18–13 Ma exhumation phase attributed to underplating/crustal shortening and erosional denudation at the front of the Calabrian wedge, concurrent with exhumation of the HP-LT Liguride Complex within the Coastal Costiera. A rapid exhumation and cooling phase at 18–17 Ma, known as the ‘Longobucco thrusting event’, marks renewed compressional tectonics within the internal part of the Calabrian wedge, followed by decreasing relief indicated by an inverted age-elevation relationship (Vignaroli et al. Reference Vignaroli, Minelli, Rossetti, Balestrieri and Faccenna2012). Apatite (U-Th)/He and AFT data from the Sila Massif plateau (Olivetti et al. Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017) reveal a phase of rapid exhumation from 18 to 15 Ma, then slower exhumation, erosion and relief degradation from 15–2 Ma.

3. Methods and sampling

A total of 19 sandstone samples were collected from northern Calabria (Fig. 1), representing the major forearc basins along its eastern margin: Rossano, Cirò, Crotone and Catanzaro. The samples span ∼18 Myr from early Miocene (Aquitanian) to late Miocene (Messinian) (Fig. 2), and range from coarse- to fine-grained sandstone. Individual sample stratigraphic ages, location coordinates and techniques applied can be found in Supplementary Table ST1. Sample preparation for heavy-mineral mounts followed the procedure of Feil et al. (Reference Feil, von Eynatten, Dunkl, Schönig and Lünsdorf2024). Mounts were prepared for three grain-size fractions (30–63 µm, 63–125 µm and 125–250 µm), according to the Udden-Wentworth scale (Wentworth, Reference Wentworth1922).

3.a. Heavy-mineral analysis via Raman spectroscopy

In order to increase the output for quantitative heavy-analysis and produce a large heavy-mineral dataset for each sample, semi-automated Raman spectroscopy via the Lünsdorf et al. (Reference Lünsdorf, Kalies, Ahlers, Dunkl and von Eynatten2019) method was applied. All grain mounts were individually photographed, images were stitched together and grains were selected for measurement. Number of grains selected per sample (for 63–125 µm interval) ranges from 1274 to 5566 with an average of 2475. To reduce selection bias, all grains mounted for each sample were chosen according to Fleet (Reference Fleet1926), taking care to avoid opaque minerals, polymineralic grains and lithoclasts. Instrumental parameters and analytical conditions for Raman microscopy are described in Feil et al. (Reference Feil, von Eynatten, Dunkl, Schönig and Lünsdorf2024). The evaluation process for Raman spectra is outlined in detail in Lünsdorf et al. (Reference Lünsdorf, Kalies, Ahlers, Dunkl and von Eynatten2019). Supplementary Table ST2 displays all collected quantitative heavy-mineral data for each sample.

3.b. Garnet geochemistry

Chemical analysis on garnet grains was conducted using a JEOL-JXA iHP200F electron probe microanalyser at the Göttingen laboratory for correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (GoeLEM) at the University of Göttingen. Since Raman spectroscopy is a non-destructive method, and the coordinates of all garnet grains had been determined, the same 63–125 µm heavy-mineral mounts were used for this method. The mounts were carbon coated to ensure conductivity before they were placed into the microprobe. Approximately 100 garnet grains were randomly selected from 11 samples across each basin, typically including one of the oldest, youngest and an intermediate sample. For samples containing fewer than 100 grains, all garnets were measured. Measurements on both grain margins and centres were conducted for 239 garnet grains, revealing minimal variation and zoning effects. Therefore, subsequent analyses included only a single measurement per grain. In total, the chemical composition of 1,216 garnet grains was analysed. An accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 20 nA were applied. Si, Mg, Ca, Fe and Al were measured using a 15 s peak time and 5 s background, while Cr, Ti and Mn were measured using a 30 s peak time and 15 s background. Quantitative geochemical data for all garnet grains is presented in Supplementary Table ST3. Garnet chemical analysis was evaluated using the Schönig et al. (Reference Schönig, von Eynatten, Tolosana-Delgado and Meinhold2021) host-rock discrimination scheme.

3.c. Apatite geochemistry and U–Pb dating

Apatite geochemistry and U–Pb dating were performed in the same analytical session at the LA-ICP-MS laboratory, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Samples containing sufficient apatite (i.e., more than 100 grains) were selected for analysis, resulting in 17 samples analysed. The same 63–125 µm heavy-mineral mounts were used, with the coordinates of ∼150 random apatite grains transferred for each sample.

In situ U–Pb isotopic and trace element analyses of apatite grains were undertaken using a Photon Machines Iridia ArF excimer laser coupled to an Agilent 7900 Q-ICP-MS. Each ablation was carried out using a 35 µm spot size, a repetition rate of 11 Hz (250 shots, corresponding to a 22.7 s ablation duration), and a 2.5 J cm-2 fluence. Upon aerosol production, pure helium gas (0.4 l min-1) was used for transportation, and subsequently mixed with argon carrier gas (0.6 l min-1) and nitrogen (c. 9 ml min-1) to enhance signal sensitivity. Raw data was processed using the IOLITE data reduction package, and the VizualAge_UcomPbine data reduction scheme (DRS) with the full data reduction methodology described in Paton et al. (Reference Paton, Hellstrom, Paul, Woodhead and Hergt2011) and Chew, Petrus & Kamber (Reference Chew, Petrus and Kamber2014). Trace element data were processed using the ‘Trace Elements’ DRS package in Iolite, with 43Ca used as the internal elemental standard.

The primary reference material for U–Pb geochronology was the Madagascar apatite (473.5 ± 0.7 Ma; Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Gehrels, Ruiz and Buchwaldt2012), with Durango apatite (31.44 ± 0.18 Ma; McDowell, McIntosh & Farley (Reference McDowell, McIntosh and Farley2005) and McClure Mountain apatite (523.51 ± 2.09 Ma; Schoene & Bowring (Reference Schoene and Bowring2006) used as secondary reference materials. For apatite trace element analysis, NIST-612 glass served as the primary reference, with McClure Mountain apatites as secondary reference. Primary reference materials were used for correction of mass bias, intra-session analytical drift and for the U–Pb analyses, the correction of downhole fractionation (Paton et al. Reference Paton, Woodhead, Hellstrom, Hergt, Greig and Maas2010); secondary references were treated as unknowns. In some apatite grains, low uranium contents resulted in minimal radiogenic Pb production and led to high uncertainties in the age data. The empirical age uncertainty filter of Chew et al. (Reference Chew, O’Sullivan, Caracciolo, Mark and Tyrrell2020) was applied, with only grains passing the following threshold criterion

![]() $2\sigma \ \text{uncertainty} \lt 16 \cdot \text{age}^{-0.65}$

taken as accepted ages. Apatite U–Pb ages and trace element analysis data are available in supplementary Table ST4 and in Table ST5, respectively.

$2\sigma \ \text{uncertainty} \lt 16 \cdot \text{age}^{-0.65}$

taken as accepted ages. Apatite U–Pb ages and trace element analysis data are available in supplementary Table ST4 and in Table ST5, respectively.

4. Results

4.a. Heavy-mineral composition

A total of 525–1540 transparent heavy-mineral grains were analysed per sample (63–125 µm fraction). Heavy-mineral concentration (HMC) falls between 0.5 and 11.1% for all samples (Supplementary Table ST2). The Rossano basin averages 2.7% HMC, with one outlier (KB-13; Serravallian/Tortonian) at 9.8%, all others are <2.2%. The Cirò basin shows the highest overall HMC (average 5.1%), with all samples >1.5% and the youngest sample (KB-7) reaching 11.1%. The Crotone and Catanzaro basins show lower averages (1.8% and 2.8%, respectively) with all samples ranging from 0.5% to 5.5%. Although some basins contain their lowest HMC value in their oldest sample, there is no general up-section trend.

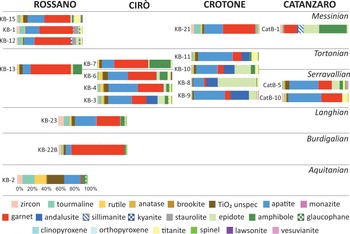

Seven samples were collected from the Rossano basin (Aquitanian–Messinian; Fig. 3), the Burdigalian and Langhian samples are included although geographically they lie between the Rossano and Cirò basins. The oldest, Aquitanian sample (KB-2) has the highest ZTR (zircon, tourmaline and rutile) at 41% and TiO2 polymorphs (not including rutile) at 26%. All other samples contain less ZTR (4%–19%), and garnet as a major component (34%–77%). Apatite is present in all samples, with proportions highest in Messinian KB-15 (25%), Langhian KB-23 (31%), and Aquitanian KB-2 (23%) samples. Amphibole ranges from 0.4%–13.6% with the highest concentration in the Serravallian/Tortonian sample (KB-13) and the lowest in the Messinian samples. Glaucophane appears in small proportions (0.07%–1.85%) in all samples with the highest quantities in Aquitanian sample (KB-2) and the three Messinian samples. Kyanite and lawsonite are only observed in the Messinian samples ranging between 0.2% and 1.9%. Titanite, staurolite and epidote are most common in the Messinian samples (total contributions ∼12%). Staurolite content is highest of all samples in two Messinian samples from the Rossano basin (KB-1, KB-15).

Figure 3. Heavy-mineral compositions for all four basins from north (Rossano basin) to south (Catanzaro basin). Stratigraphic ages (not to scale) along the left-hand side from oldest (bottom) to youngest (top). ‘TiO2 unspec’ relates to all TiO2 minerals which cannot be assigned as rutile, brookite or anatase.

The Cirò basin (four Serravallian–Tortonian samples, Fig. 3) is dominated by garnet and apatite (50%–72%). The ZTR index is <9% for all, the lowest in the youngest sample KB-7 (3%). Significant andalusite can only be found in the oldest sample KB-3 at 15%. Epidote decreases up-section (10% to 2%), while amphibole increases (4% to 28%). Minor contributions include titanite (1%–4%), glaucophane (<1%) and spinel (<1%).

In the Crotone basin (five Serravallian–Messinian samples Fig. 3), apatite is consistently major (16%–51%), with highest concentrations in KB-11 and KB-9. The ZTR index is <5% except in Messinian sample KB-21 (16%) which also shows elevated garnet (47%). These samples stand out from all the other basins by their significant andalusite content, decreasing up-section from 27% in KB-9 to 11% in KB-11. Where apatite concentration is lowest (KB-8; 16%), epidote makes up 57%, the highest of all samples. KB-10 and KB-9 also contain 24% and 11% epidote, respectively, while it almost disappears in the two youngest samples. Minor minerals include titanite (max. 9% in KB-11), amphibole (max. 6% in KB-10), and staurolite in KB-21.

The Catanzaro basin (three Serravallian–Messinian samples, Fig. 3) contains high apatite (43% and 50%) and garnet (20% and 31%) in its Serravallian samples (CatB-10 and CatB-5) (Fig. 3). CatB-5 and CatB-1 contain significant proportions of epidote (12% and 23%, respectively), which is absent in CatB-10, however, CatB-10 contains most titanite at 9%. The Messinian CatB-1 sample is distinct for its high amphibole (41%), andalusite (2%) and sillimanite (8%), the latter of which is not found in considerable amounts (>1%) in any other sample.

4.a.1. Mitigating controls on heavy-mineral assemblages

As mentioned above (see section 1), controls on heavy-mineral assemblages can alter their relative abundances and lead to potentially unreliable interpretations. Therefore, it is important to ensure the composition of the grain-size interval being studied is representative of the entire sample. Feil et al. (Reference Feil, von Eynatten, Dunkl, Schönig and Lünsdorf2024) highlights one of these control factors, termed grain-size inheritance, which emphasizes the importance of selecting the most characteristic grain-size interval for each sample. They show that fine (30–63 μm) and coarse (125–250 μm) grain-size intervals are extremely susceptible to being enriched or depleted in certain mineral species, directly dependent on parent-rock lithology. Here, we applied the same methodology to determine the effect, if any, of grain-size inheritance on these samples (Supplementary Fig. SF1). Results show that for the four samples where three grain-size fractions were analysed (KB-1, KB-2, KB-8 and CatB-1), their fine and coarse grain-size intervals contain evidence of inheritance. Several heavy-mineral ratios (which are generally used to compare minerals with similar stabilities) follow the expected grain-size trend (CatB-1), however, significant deviations are also observed. This includes, besides the well-known ‘over-enrichment’ of zircon in fine fractions (KB-2), depletion of andalusite in fine fractions (KB-8) or the enrichment of tourmaline in the coarse fraction (KB-1). Overall, the focus of the intermediate grain-size interval (63–125 μm) appears fully appropriate for the purpose of this study.

4.b. Garnet geochemistry

Twelve samples (Burdigalian–Messinian) representing all four basins were analysed for their garnet chemistry, totalling 1113 grains. Where available approx. 100 grains were measured for each sample, only KB-9 and KB-11 did not reach this threshold. The major-element chemical compositions of garnet define proportions of the common endmembers: almandine, pyrope, spessartine and grossular, although Ca can also be found in andradite. Petrogenetic information was evaluated using ternary plots (Fig. 4a) and the garnet host-rock discrimination scheme from Schönig et al. (Reference Schönig, von Eynatten, Tolosana-Delgado and Meinhold2021) (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Garnet geochemistry overview. (a) Ternary plots for each basin displaying common garnet endmembers with their associated major-element composition: pyrope (XMg), almandine (XFe) + spessartine (XMn) and grossular or andradite (XCa). (b) Bar plots for each sample showing their garnet host-rock proportions, calculated from the random forest machine learning approach of Schönig et al. (Reference Schönig, von Eynatten, Tolosana-Delgado and Meinhold2021).

The Rossano basin samples show a wide range in garnet chemistry. Burdigalian sample KB-22B is dominated by Ca-rich (>50% proportion of XCa; Fig. 4a) grossular garnet (94%). The other samples contain Fe- and Mn-rich (>50% XFe + XMn) almandine and spessartine garnet (95%–99%), but with varying Mg and Ca contents. For the host-rock discrimination scheme, KB-22B is dominated by metasomatic (48%) and granulite-facies (47%) garnets (Fig. 4b). Sample KB-13 (Serravallian–Tortonian) contains abundant amphibolite-facies garnet (72%), decreasing to 40%–50% in the Messinian samples (KB-1, KB-15). Igneous garnet similarly declines (15%–5%), while high-grade metamorphic types increases upsection, with granulite-facies garnet highest in KB-15 (48%) and eclogite/ UHP and blueschist/greenschist-facies garnet highest in KB-1 (11% and 16%, respectively).

The majority of grains for the Cirò basin congregate in the almandine + spessartine corner (Fig. 4a), though high-Ca grains (>50% XCa) are common in the oldest sample KB-3 (49%) and decline up-section (7% in KB-6; 2% in KB-7). KB-3 and KB-6 show higher pyrope content (up to 46%) compared to KB-07 (max. 26%). Host-rock types evolve up-section with increasing amphibolite-facies garnet (28% to 68%) and decreasing metasomatic host rocks (43% to 1%), while igneous (11%–12%), granulite (15%–22%) and blueschist/greenschist (1%–2%) proportions remain stable (Fig. 4b). The younger two samples (KB-6,-7) resemble sample KB-13 from the Rossano basin, all of them having roughly the same stratigraphic age.

For the Crotone basin, the two Serravallian–Tortonian samples (KB-9 and KB-11) are dominated by Ca-rich garnet (∼93%), whereas the Messinian sample KB-21 clusters in the almandine + spessartine corner with up to 40% pyrope content (Fig. 4a). Correspondingly, KB-9 and KB-11 are dominated by metasomatic garnets (81% and 70%), with minor granulite (<25%) and amphibolite (<6%) facies garnets (Fig. 4b). KB-21 is more diverse: 54% amphibolite facies, 17% blueschist/ greenschist, ∼12% from both granulite facies and igneous, and <3% for metasomatic and eclogite/ UHP. The composition of KB-21 closely matches Messinian samples from the Rossano basin.

The two Catanzaro basin samples (CatB-10 and CatB-1) contain mixtures of almandine + spessartine rich garnet and Ca-rich garnet (Fig. 4a). Ca-rich (>50% XCa) grains comprise 73% (CatB-10) and 48% (CatB-01) of garnets. Pyrope-rich garnet (>20% Mg) is more common in the younger sample CatB-1 (37% versus 19%). Metasomatic and granulite-facies garnets decrease from 42% to 20% from CatB-10 to CatB-1, while igneous and amphibolite-facies increase (15% to 24% and 1% to 32%, respectively) (Fig. 4b). Both samples are compositionally distinct from age-equivalent samples in other basins.

4.c. Apatite geochemistry

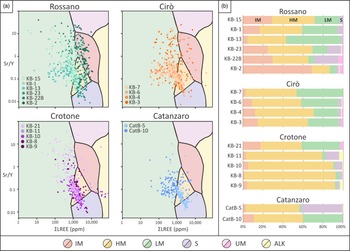

For apatite geochemistry, the Sr/Y vs ΣLREE (LREE defined as ranging from La to Nd) plots (Fig. 5a) help categorize the data according to source rock type (O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020). Approximately 150 apatite grains were randomly selected for 17 samples, with 2274 grains measured in total.

Figure 5. Apatite trace element composition for each basin. (a) The sum of light rare earth elements (ΣLREE) versus strontium/yttrium plots overlain with the SVM category boundaries from O’Sullivan et al. (Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020); ΣLREE is defined as the sum of concentrations of La to Nd. Both axes use logarithmic scale. (b) Apatite host-rock classification bar plot. Legend with classification groups at the base. IM: mafic I-type granitoids and mafic igneous rocks; HM: partial-melts/leucosomes/high-grade metamorphic; LM: low- and medium-grade metamorphic and metasomatic; S: S-type granitoids and high aluminium saturation index (ASI) ‘felsic’ I-types; UM: ultramafic rocks including carbonatites, lherzolites and pyroxenites; ALK: alkali-rich igneous rocks.

The Rossano basin samples show wide compositional variability with ΣLREEs values of 80–10,000 ppm, and a decreasing trend with age from KB-2 (Aquitanian) to KB-13 (Serravallian/Tortonian), followed by a slight increase in Messinian samples (KB-1 and KB-15) (Fig. 5a). Values for Sr/Y range broadly, KB-2 and KB-22B display the widest spread and highest (>10) Sr/Y values, while KB-13 has the lowest mean value and KB-1 and KB-15 show narrow, low Sr/Y ranges. Apatites provenance is dominated by mafic I-type granitoids and igneous rocks (IM), especially in the three oldest samples KB-2 (69%), KB-22B (30%), and KB-23 (25%), and youngest sample KB-15 (29%) (Fig. 5b). High-grade metamorphic rocks (HM) contribute 36%–45% for all but KB-2 (18%), while low-medium grade metamorphic and metasomatic rocks (LM) supply 25%–55% in the youngest samples.

Samples of the Cirò basin cluster around 1000 ppm for the ΣLREEs and 0.1 for Sr/Y, with minor sample variation and a subtle trend of decreasing ΣLREE and Sr/Y with age (Fig. 5a). The oldest sample KB-7 shows the broadest Sr/Y range, while KB-7 shows the narrowest. Host-rock discrimination (Fig. 5b) indicates apatites are most dominant from high-grade metamorphics and partial-melts (HM) (49%–59%) and low-medium grade metamorphics (LM) (24%–46%) sources, with decreasing mafic igneous (IM) apatite contributions from 15% (KB-3) to 3% (KB-7). Again, the younger Cirò samples (KB-6, KB-7) closely resemble coeval Rossano sample KB-13.

The Crotone basin exhibits a narrower range for ΣLREE values (1000–2000 ppm) across all samples, except for KB-21, which shows much greater variability and some very low (<300 ppm) values (Fig. 5a). Sr/Y values for most samples fall between 0.4–0.14, but KB-21 includes grains from 0.3–20. Host-rock discrimination shows high HM apatite proportions (76%–91%) in Serravallian–Tortonian samples, unique among all basins (Fig. 5b). The Messinian sample KB-21 differs, with only 41% HM apatite, with 38% LM and 18% IM sources.

The two Catanzaro basin samples contrast strongly: CatB-5 contains higher ΣLREE concentrations and lower Sr/Y values, and CatB-10 shows the opposite trend (Fig. 5a). Variation is lowest for both variables in CatB-5, while CatB-10 exhibits a much greater spread. Both samples contain ∼50% HM apatite (Fig. 5b). However, where CatB-10 contains 39% LM-derived apatites, CatB-5 has 41% coming from S-type granitoids and ‘felsic’ I-types.

4.d. Apatite U–Pb dating

Of the 2,278 apatite grains analysed, 2,010 produced acceptable ages (see section 3.c), across 17 samples. Samples are grouped based on stratigraphic age and/ or basin location. The three oldest samples from the Rossano basin, and between the Rossano and Cirò basins (KB-2, KB-22B and KB-23), span from Aquitanian to Langhian in age and show roughly similar age distributions (Fig. 6a). They display two main age populations: a dominant Carboniferous to Permian (359–252 Ma) group and a subordinate Cambrian to Silurian (540–440 Ma) group. Samples KB-22B and KB-23 contain ∼50% grains in the narrow 330–290 Ma age group. KB-2 has the widest spread of ages, including more a pronounced Permo-Triassic shoulder and a significant contribution (∼18 %) of younger apatites (<200 Ma).

Figure 6. Overview of apatite U–Pb Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) plots using the R provenance package (Vermeesch, Resentini & Garzanti, Reference Vermeesch, Resentini and Garzanti2016). Samples have been split into groups by basin and/or stratigraphic age. Grey bars represent the geological periods from Carboniferous to Triassic (e). The symbol for each sample key is associated with its stratigraphic age (d). Note n equals the number of accepted apatite grains over the total apatite grains analysed. Samples within each panel (a-e) are listed in stratigraphic order with oldest at the bottom.

The two Messinian samples from the Rossano basin (KB-15 and KB-1) are grouped with the Messinian Crotone basin sample KB-21 (Fig. 6b). They show one significant Carboniferous to Permian age population. While samples KB-1 and KB-21 have a peak in the Carboniferous, KB-15 contains a pronounced Permian shoulder. Mesozoic ages (252–66 Ma) make up only 10%. A small Silurian peak (∼430 Ma) is visible.

The Serravallian/Tortonian sample from the Rossano basin (KB-13) shares similarities with the Cirò basin samples of the same age (KB-3, KB-4, KB-6, KB-7; Fig. 6c). All show a clear Upper Carboniferous to Permian age population (358–252 Ma). An additional Triassic age group (252–201 Ma) is most prominent for KB-13, but also clear for KB-6, KB-7, KB-3 and KB-4. The Rossano basin sample, KB-13, shows an approximately 55/45 split between the Triassic and Carboniferous-Permian age populations, whereas KB-6 and KB-3 differ with splits of 35/65 and 20/80, respectively. The four Serravallian–Tortonian Crotone basin samples show a single significant age population from late Carboniferous to early Permian (330–280 Ma) which encompasses 80% of all ages (Fig. 6d). There is a distinct lack of apatite ages in the ranges <250 Ma and >350 Ma, representing only 6% of the grains, which is unique compared to the other basins.

Once again, the Catanzaro basin samples show significant variation (Fig. 6e). The CatB-10 contains a much larger spread of ages, with an overall younger spectrum than CatB-5. The main age population, containing 58% of ages, is Permian to early Triassic (300–230 Ma), but with a pronounced shoulder towards the Late Carboniferous (23%; 350–300 Ma) and a smaller one comprising Late Triassic to Early Jurassic ages (9%; 230–180 Ma). Conversely, CatB-5 displays one major age population from Late Devonian to middle Permian (370–280 Ma) with a slight skew towards the older ages.

Apatite grains classified using the trace element discrimination scheme (O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020) were plotted against their corresponding U–Pb ages to assess potential relationships between source rock lithology and age (Supplementary Figure SF2). No systematic trend was observed; however, some of the relatively young (<100 Ma) and old (600–500 Ma) grains cluster within the mafic I-type granitoid and mafic igneous rock (IM) field. Most of the non-datable apatites (∼12% of all analysed apatite) are derived from low-grade metamorphic rocks.

5. Discussion

Variations in heavy-mineral suites, garnet and apatite chemistry and apatite U–Pb ages both spatially and temporally give insights into changing sediment provenance, the migration of the orogenic divide, and thus, drainage pathways through the Miocene. Principal component (PC) analysis allows for capturing major variations, and their controlling variables, for both the multivariate heavy-mineral assemblage and mineral chemistry data sets. For analysis of geochronology data, a Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) plot produces a ‘map’ in which similar samples are plotted closely together and vice versa, utilizing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test as measure of dissimilarity (Vermeesch, Reference Vermeesch2013).

5.a. Aquitanian to Langhian (Rossano basin)

Early Miocene samples are only available from the Rossano basin: KB-2 (Aquitanian), KB-22B (Burdigalian) and KB-23 (Langhian) with the latter two located between Rossano and Cirò basins (Fig. 1a). While these samples share some common features, they exhibit variability in their mineralogical and chemical composition. The oldest sample KB-2 contains the most stable heavy-mineral assemblage, reflected in its high ZTR index (Figs. 3, 7b). Despite the presence of apatite and minor amphibole including glaucophane, this assemblage suggests higher sediment maturity compared to all other samples. In contrast, KB-22B and KB-23 show lower ZTR values and are more dispersed, but plot on the garnet side of PC-1 (Figs. 7a, 7b). Garnet chemistry reveals a dominance of metasomatic and granulite-facies garnets for KB-22B (Fig. 7c), plotting apart from most other basins. Unique for all the early Miocene samples are the considerable proportions of IM-derived apatites (Figs. 5, 7d), with proportions decreasing up-section through the early Miocene to Serravallian/Tortonian (S/T) sample KB-13, alongside increasing metamorphic (HM- and LM-derived) apatite. These samples, most notably KB-2, display the widest range of U–Pb apatite ages among all samples (Fig. 8a). All samples have a pronounced ∼300 Ma age population, however, a secondary Early Palaeozoic age population (mostly Ordovician) is seen in all three samples (especially KB-2 and -23), suggesting significant admixture of apatite grains that escaped resetting during the Variscan orogeny. These most likely originate from upper-crustal greenschist to lower amphibolite-facies units of the Calabride Complex (Fig. 1) and/or low-grade metasediments of the Liguride Complex. Comparable zircon U–Pb ages have previously been reported from the Mandatoriccio Paragneiss Unit (446 ± 12 Ma), the lower crust of the Sila Unit (452 ± 12 Ma), and metasediments of the Castagna Unit (452 ± 10 Ma) (Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Festa, Micheletti, Spiess and Tursi2020). Permian to Triassic apatites (∼20%) suggest sources in the lower crustal Sila Unit (Permian) and/or even lower structural units (Triassic; Liguride, Apennine). Due to the positioning of Calabria either directly connected or nearby the Sardinia-Corsica block during the early to middle Miocene (e.g., Faccenna et al. (Reference Faccenna, Piromallo, Crespo-Blanc, Jolivet and Rossetti2004), sourcing of oceanic ophiolite units (incl. blueschists) may have also originated from this region.

Figure 7. Principal component (PC) analysis for heavy minerals, garnet geochemistry and apatite trace element analysis. (a) and (b): PC-1 vs. PC-2 and PC1 vs. PC 3, respectively for heavy-mineral data. Heavy minerals with low variability all fall within the circle in the centre of the plot, these mineral species are listed in the top right corner. (c) PC-1 vs. PC-2 for garnet geochemical data. (d) PC-1 vs. PC-2 for apatite trace element analysis. Red to orange coloured arrows in all subplots mark the trend from old to young for Cirò basin samples. Coloured envelopes connect samples from the same time period/basin as described in the key. Darker colours relate to older samples within the respective group. Heavy-mineral abbreviations according to Whitney & Evans (Reference Whitney and Evans2010); garnet host-rock abbreviations from Schönig et al. (Reference Schönig, von Eynatten, Tolosana-Delgado and Meinhold2021), and apatite group abbreviations from O’Sullivan et al. (Reference O’Sullivan, Chew, Kenny, Henrichs and Mulligan2020). Please note: for garnet and apatite chemistry PC-1 and PC-2 (c and d) cover almost all variability (95 and 89%, respectively), while for the heavy minerals PC-1 to-3 (a and b) capture altogether 89% of total variability.

Figure 8. (a) Cumulative frequency plot for apatite U–Pb age data. Green shaded region encompasses all Messinian samples (KB-1, KB-15 and KB-21). Pink shaded region encompasses all Serravallian/ Tortonian Crotone basin samples (KB-8, KB-9, KB-10, and KB-11). All other lines reference a single sample, with filled lines representing Aquitanian to Langhian samples, and dashed lines referring to Serravallian/ Tortonian samples (except for the Crotone basin). Note sample KB-13 in brown colour to signify its outstanding character and the upsection increasing similarities of the Cirò basin samples with KB-13. (b) Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) plot for the apatite U–Pb age data, made using the R provenance package (Vermeesch, Resentini & Garzanti, Reference Vermeesch, Resentini and Garzanti2016). Solid lines denote closest (most similar) neighbours, and dashed lines denote second closest neighbours.

5.b. Serravallian to Tortonian

5.b.1. Crotone basin

The Serravallian/Tortonian (S/T) samples from the Crotone basin exhibit distinct characteristics. PC-1, calculated from heavy-mineral composition, accounts for ∼50% of the total variance and separates andalusite, epidote and apatite on the left-hand side, from garnet on the right (Figs. 7a, 7b). All S/T Crotone basin samples cluster on the far-left side, setting them apart from other basins. The unique presence of andalusite in the Crotone basin samples points to low pressure-high temperature (LP-HT) conditions, characteristic of contact metamorphism. These conditions are consistent with the influence of the Sila Batholith, a large granitic intrusion which drove contact metamorphism in the surrounding country rocks, producing andalusite-bearing parageneses along its contact. Andalusite in this context likely formed through muscovite dehydration melting in pelitic rocks of the Sila unit, triggered by the high-temperature emplacement of the batholith (Graessner & Schenk, Reference Graessner and Schenk2001; Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Dorais, Barbarin, Barker, Cesare, Clarke, El Baghdadi, Erdmann, Förster, Gaeta, Gottesmann, Jamieson, Kontak, Koller, Leal Gomes, London, Morgan, Neves, Pattison, Pereira, Pichavant, Rapela, Renno, Richards, Roberts, Rottura, Saavedra, Sial, Toselli, Ugidos, Uher, Villaseca, Visonà, Whitney, Williamson and Woodard2005). Andalusite is also reported within leucogranites and granodiorites associated with both minor and major intrusions of the Sila Batholith (Messina et al. Reference Messina, Compagnoni, Vivo, Perrone and Russo1991; Ayuso et al. Reference Ayuso, Messina, Vivo, Russo, Woodruff, Sutter and Belkin1994; Caggianelli, Del Moro & Piccarreta, Reference Caggianelli, Del Moro and Piccarreta1994). Apatite is commonly found as an accessory mineral in intermediate to felsic igneous rocks, such as those composing the Sila Batholith. Epidote is characteristic of low- to medium-grade metamorphic rocks, in agreement with the heavy-mineral assemblages observed in the surrounding metapelites and within the Sila Unit itself (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020). Andalusite is also described in metasedimentary rocks of the Mandatoriccio Unit, especially in the Campana area in proximity to granodiorites (Langone et al. Reference Langone, Godard, Prosser, Caggianelli, Rottura and Tiepolo2010).

Regarding garnet chemistry, the S/T Crotone basin samples show a distinctive, uniform source. PC-1 in Figure 7c (∼80% of variance) differentiates metasomatic garnet host-rocks from amphibolite-facies garnets, with Crotone basin samples exhibiting a strong metasomatic influence. The abundance of metasomatic source rocks complements the andalusite–epidote–apatite-bearing heavy-mineral assemblage. Metasomatic rocks are typically associated with igneous intrusions, likely forming through contact metamorphism and hydrothermal fluid activity during the emplacement of the Sila Batholith. Minor proportions of granulite-facies garnet (Fig. 4) are likely associated with the adjacent Sila Unit as described in Graessner & Schenk (Reference Graessner and Schenk2001). The S/T Crotone basin apatites form a discrete group away from other basins (Fig. 7d). PC-1 (∼50% sample variance) differentiates apatites sourced from partial melts, leucosomes and high-grade metamorphic rocks (HM) from those associated with mafic I-type granitoids and mafic igneous rocks (IM), and low- and medium-grade metamorphic sources (LM). The S/T Crotone basin samples plot in the HM group, suggesting a dominant influence from partial melts and leucosomes, while S-type granitoids and high aluminium saturation index (‘felsic’) I-types are also seen, particularly in samples KB-10 and KB-11. These findings align with sourcing from the Sila Batholith, where partial melting and crustal anatexis generated apatite-rich leucosomes (Messina et al. Reference Messina, Compagnoni, Vivo, Perrone and Russo1991).

Apatite U–Pb dating of the S/T Crotone basin samples (Fig. 6d) yields a strikingly consistent Late Carboniferous to Early Permian age population, with 46% falling between 310–290 Ma. The MDS plot (Fig. 8b) displays the close similarities between these samples, separated from other basins. The narrow and well-defined age distribution of all four samples (Fig. 8a) is consistent with widespread felsic magmatism associated with the final stages of the Variscan orogeny. Timing closely matches the ∼300–295 Ma emplacement of the Sila Batholith, according to U–Pb dating of zircon, xenotime and monazite (Graessner et al. Reference Graessner, Schenk, Bröcker and Mezger2000). It also matches the dominant range of Variscan zircon ages (ca. 325–280 Ma) from the deeper crust of the Sila Unit (Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Festa, Micheletti, Spiess and Tursi2020). Given that apatite U–Pb ages reflect cooling through temperatures of 350–550 °C (Chew & Spikings, Reference Chew and Spikings2015), these ages likely record fast cooling following granite emplacement and its high-temperature impact on surrounding units.

5.b.2. Cirò and Rossano basins

The four samples from the Cirò basin, together with KB-13 from the Rossano basin, illustrate a transitional trend through time. Compared to the Crotone basin, these samples display greater variability in heavy-mineral assemblages on PC-1 (Figs. 7a, 7b). A major increase in garnet up-section alongside subordinate amphibole, seen by the general trend from lower left to upper right on Figure 7a, shows a provenance evolution from a ‘Crotone basin-like’ setting in the basal Serravallian to a ‘Rossano basin-like’ setting in the Tortonian. Garnet geochemistry supports this trend with a change from garnets hosted mainly by metasomatic and igneous rocks to mainly amphibolite-facies-derived garnets (Figs. 4, 7c). Apatites derived from low- to medium-grade (LM) metamorphic rocks also increase, reflecting compositional affinities with the Rossano basin sample KB-13 (Fig. 7d).

This progressive shift suggests sourcing from the Sila granitoids and the surrounding high-temperature contact aureole becomes less important up-section for the S/T samples of the Cirò basin and almost negligible for the Rossano basin and sourcing from metamorphic rocks becomes significant. Sourcing from the high-grade metapelite and Sila Unit of the lower crust can be linked to the increase in metamorphic grade of the garnets. This shift would imply continued exhumation of the Sila Massif, leading to increasingly exposed deeper levels of metamorphic basement over time. The other possible sources are the Mandatoriccio and Bocchigliero Units, forming part of the upper Variscan crust which outcrops proximal to both basins (Fig. 1). These units underwent greenschist to amphibolite-facies metamorphism during the Variscan orogeny, which would explain the presence of both low- to medium-grade apatites and garnets (Langone et al. Reference Langone, Godard, Prosser, Caggianelli, Rottura and Tiepolo2010).

The up-section trend from KB-3 to KB-13 is also seen by the trend in apatite ages on the MDS plot (Fig. 8b), where dissimilarities with the early Rossano basin samples increase up-section. All four Cirò basin samples, along with the coeval Rossano basin sample KB-13, contain a Late Carboniferous to Early Permian age population (Fig. 6c). Although somewhat similar to the ∼300 Ma age population observed in the Crotone basin, especially for KB-3, these samples span a broader age range with pronounced Permian shoulders (300–265 Ma), with KB-6, KB-7 and KB-13 only containing ∼15% ages >300 Ma (Fig. 8a). Similar Permian detrital zircon U–Pb ages have been reported in both fine-grained leucocratic gneisses of the Castagna Unit (Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Langone, Micheletti and Piccarreta2011; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Xia, Zheng and Chen2011) and deep continental crustal rocks of the Sila-Serre Unit (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Xia, Zheng and Chen2011). Permian apatite ages likely reflect post-emplacement cooling of the Sila Batholith granitoids associated with late- to post-Variscan tectono-magmatic processes. However, Micheletti et al. (Reference Micheletti, Fornelli, Piccarreta, Barbey and Tiepolo2008) report detrital zircon ages ∼280 Ma from the Variscan lower crust of the Serre Massif (southern Calabria), assigning these ages to decompressional anatexis as a result of crustal thinning and biotite-dehydration melting. The 280–260 Ma apatite ages reported here may also reflect this Late Variscan crustal decompression event. Additionally, the Cirò/Rossano basin samples exhibit a Triassic age population (250–200 Ma) which is most prominent in the younger Cirò basin samples and especially KB-13 from the Rossano basin. Similar Triassic ages have been reported from the Serre Unit (lower crust) of southern Calabria (which can be considered coeval to the northern Sila Unit) by U–Pb zircon dating (249±4 Ma and 231 ± 5 Ma, Micheletti et al. (Reference Micheletti, Fornelli, Piccarreta, Barbey and Tiepolo2008); Rb-Sr whole rock ages (234 ± 6 Ma, Caggianelli et al. (Reference Caggianelli, Del Moro, Paglionico, Piccarreta, Pinarelli and Rottura1991); Rb-Sr biotite cooling ages (244–230 Ma, Borsi et al. (Reference Borsi, O. Hieke Merlin, Lorenzoni, Paglionico and Zanettin Lorenzoni1976); and Sm-Nd garnet cooling ages (215 Ma, Schenk (Reference Schenk, Daly, Cliff and Yardley1989). In addition, U–Pb dating of Fe-Mg gabbros from the northern Catena Costiera from the base of the Variscan lower crust section yield 242–227 Ma magmatic ages (Liberi, Piluso & Langone, Reference Liberi, Piluso and Langone2011). They likely represent a phase of Triassic magmatic activity sent from the Dinarides through the Southern Alps to Sardinia and Calabria (Borsi et al. Reference Borsi, O. Hieke Merlin, Lorenzoni, Paglionico and Zanettin Lorenzoni1976), and might be considered an early indicator of the extensional stage preceding the opening of the Jurassic Tethys (Del Moro, Fornelli & Piccarreta, Reference Del Moro, Fornelli and Piccarreta2000; Fornelli et al. Reference Fornelli, Festa, Micheletti, Spiess and Tursi2020).

5.b.3. Catanzaro basin

The two S/T Catanzaro basin samples share a comparable heavy-mineral composition and plot in similar regions on the PCA biplot, with PC-1 (∼50% of variance) showing apatite is most influential for both samples (Figs. 3, 7a, 7b). After apatite and garnet, titanite is the third most common mineral for CatB-10 and epidote for CatB-5. Garnet chemistry shows a diverse source of host-rock types involved, with CatB-10 plotting very centrally (Fig. 7c), seemingly not dominated by one particular host-rock (Fig. 4). Both samples plot in different fields of apatite host-rock composition, with CatB-10 strongly influenced by LM-derived apatites, and CatB-5 by S-derived apatites, while both samples contain ∼50% of HM-derived apatites. This contrast is also seen by their U–Pb apatite age distribution (Figs. 6e, 8). CatB-5 shows one strong age population at ∼330–290 Ma, displaying similarities with the Crotone basin samples. CatB-10 yields Variscan ages alongside a pronounced Permian population (300–250 Ma), in addition to minor Triassic ages (250–200 Ma). The high proportion of granitoid-derived apatite of Variscan age (∼300 Ma) for CatB-5 clearly points to a dominant Sila Batholith provenance, similar to that seen in the Crotone basin, and further supported by significant epidote concentrations. In contrast, CatB-10 has a dominant metamorphic apatite population of Permian age, which is typical for the lower crustal rocks of the Sila Unit and potentially also the Castagna nappe. The proximal Bagni nappe may also be a source, providing minor proportions of low-grade greenschist-facies garnets and epidote. Significant titanite (Fig. 3) along with the highest proportions of igneous garnet for all samples (Fig. 4) may suggest additional contribution from mafic rocks (i.e., the Liguride Complex, Table 1). The strong contrast between the two samples and their spatial position (Fig.1) points to diverse drainage into the Catanzaro basin during the Serravallian.

5.c. Messinian

The three Messinian Rossano basin samples are defined by their enrichment of high-pressure (HP) metamorphic minerals glaucophane, kyanite and lawsonite, which are absent from other basins (Supplementary Fig. SF3). Additionally, significant staurolite is only present in the Messinian samples (except for KB-15). PCA biplots (Figs. 7a, 7b) place these four samples together towards the garnet-rich end of the compositional space, reflecting their similarities. When evaluating sediment sourcing, the presence of HP minerals suggests an origin from the Liguride Complex, likely the Diamante-Terranova Unit, which extends E–NE across northern Calabria. This unit comprises metaophiolites that experienced HP-LT blueschist-facies metamorphism during the Eocene (Shimabukuro et al. Reference Shimabukuro, Wakabayashi, Alvarez and Chang2012) linked to the subduction of Liguride oceanic lithosphere (Vitale et al. Reference Vitale, Fedele, Tramparulo and Prinzi2019b). The subsequent exhumation of the Diamante-Terranova Unit during the late Oligocene to Serravallian, dated through zircon and apatite FT thermochronology (Thomson, 1994, 1998), makes it plausible that HP–mineral-rich detritus was available for deposition into the Crati and Rossano basin during the Messinian. Vitale et al. (Reference Vitale, Fedele, Tramparulo and Prinzi2019b) describe the unit as consisting of glaucophane–lawsonite-bearing metabasalts with accessory titanite, supporting this interpretation.

The three Rossano/Crotone basin samples display similar trends in garnet chemistry along PC-1, highlighting abundant amphibolite-facies garnets, but show considerable variation along PC-2, due to variation in granulite-facies garnets (Fig. 7c). Although in relatively smaller proportions, the presence of blueschist/greenschist-facies and eclogite/UHP garnets in these samples is unique (Fig. 4). The garnet chemistry of KB-21 (Crotone basin) closely resembles that of KB-1 (Rossano basin), suggesting either a shared sediment source during the Messinian or potential southward sediment recycling from Rossano to Crotone basin, perhaps prior to the development of the Cirò structural high during the late Messinian (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008). Sourcing for the garnets found in the Rossano basin can be assigned to the Diamante-Terranova Unit of the Liguride Complex, with its distinctive HP-LT metamorphic nature. The presence of amphibolite-facies garnets, alongside a heavy-mineral composition including staurolite, could be a signal of sediment draining the Mandatoriccio Unit of the upper Variscan crust. However, with amphibolite-facies garnets decreasing and granulite-facies garnets increasing up-section (KB-15, Fig. 7c), the higher-grade metapelite and Sila Unit becomes more significant during the late Messinian.

Apatite trace element chemistry in the Rossano/Crotone basin samples implies most influence from mafic I-type granitoids and mafic igneous rocks (IM) and LM-derived apatites (PC-1; Fig. 7d). PC-2 differentiates IM from LM, which reflects the up-section increase in IM-derived apatites from Serravallian sample KB-13 to the youngest Messinian sample KB-15 (Fig. 5). High proportions of IM-derived apatites are unique to the Rossano basin. The coexistence of apatite-bearing mafic I-type granitoids and garnet-bearing blueschists with HP minerals provides insight into the tectono-magmatic evolution associated with the subduction of the Liguride Oceanic Complex within the Southern Ligurian Domain. The blueschist garnets and HP minerals reflect subducted Liguride oceanic crust and its sedimentary cover, which underwent blueschist-facies metamorphism (Liberi, Morten & Piluso, Reference Liberi, Morten and Piluso2006). In contrast, the presence of mafic I-type granitoid apatite in the Rossano basin is a sign of subduction-related magmatic activity, likely driven by mantle wedge melting above the subducting slab (Liberi & Piluso, Reference Liberi and Piluso2009).

Apatite U–Pb dating reveals a significant ∼330–300 Ma age population, with KB-15 having the most pronounced Permian shoulder (Fig. 6b). Similarities in their age populations are underlined in the MDS plot (Fig. 8b), with KB-1 and KB-21 plotting particularly close together. The age distributions are broader than in the Serravallian–Tortonian samples from the Crotone basin and include a distinct Permian age component (Fig. 8a), which is consistent with sources related to Variscan plutonism and high-temperature metamorphism within the basement units of the Sila Massif.

The single Messinian Catanzaro basin sample (CatB-1) has a distinctive heavy-mineral composition containing sillimanite, the only sample with proportions this high, alongside abundant epidote and amphibole. In most mineralogical and chemical biplots, CatB-1 plots away from other basins (Fig. 7). Most garnets are derived from either metasomatic or granulite-facies host rocks (Fig. 4). Figure 7c highlights the high proportions of granulite-facies garnets, which is only shared with the Burdigalian (KB-22B) and Messinian (KB-15) samples from the Rossano basin. The presence of sillimanite suggests sourcing from the mid-crustal Castagna Unit, where prismatic sillimanite is frequently described (Brandt & Schenk, Reference Brandt and Schenk2020) or from the high-grade Metapelite and Sila Unit of the lower crust, supported by the abundant granulite-facies garnets. The proximal Bagni nappe could be the source of the abundant amphibole and epidote.

5.d. Implications for drainage evolution

Integrating the erosional history of northern Calabria from the early Miocene to present (Fig. 9d; Olivetti et al. Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017) with our detailed provenance analysis, we present an updated reconstruction of the Ionian margin drainage evolution in northern Calabria throughout the Miocene (Fig. 9a–c). This synthesis expands upon the paleotectonic framework made by Barone et al. (Reference Barone, Dominici, Muto and Critelli2008).

Figure 9. Schematic sketches showing the provenance evolution for the Ionian margin of northern Calabria during the (a) Early to middle Miocene, (b) Serravallian to Tortonian, and (c) Messinian. (d) Evolution of Neogene relief within Northern Calabria adapted from Olivetti et al. (Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017). Only the major units supplying sediments are marked by their respective colours, the buried, not eroding or minor units are shown in greyscale. The Corsica-Sardinia block is shown in (a), representing its connected/ nearby position during the Early to middle Miocene, and its potential delivery of high-pressure ophiolite units. This block is expected to have split away from northern Calabria by the middle Miocene (i.e., Langhian–Serravallian) (Faccenna et al. Reference Faccenna, Piromallo, Crespo-Blanc, Jolivet and Rossetti2004; Critelli et al. Reference Critelli, Muto, Perri and Tripodi2017). The red arrow in (a) signals the beginning of thrusting and uplift in the Burdigalian. By the Serravallian–Tortonian, in (b), the plutonic and Sila Unit rocks form the highest relief in the region.

5.d.1. Early to middle Miocene (23–14 Ma)

All three samples originate from the Rossano basin, and thus our interpretations of sediment transport during this time are limited to this area. At this time during the early Miocene, the pre-thrusting lower topographic relief suggests longer distance transport a possibility. Therefore, sediment likely sourced from the HP-LT metamorphic Liguride Complex in NW Calabria, and perhaps from similar ophiolite units in the nearby Sardinia-Corsica block (Faccenna et al. Reference Faccenna, Piromallo, Crespo-Blanc, Jolivet and Rossetti2004; Critelli et al. Reference Critelli, Muto, Perri and Tripodi2017), were delivered towards the E/SE into the Rossano basin (Fig. 9a). This pathway became less relevant by Langhian time, compensated by increased input from the Calabride Complex, that is, Sila and Mandatoriccio/ Bocchigliero Units. Rapid extensional exhumation of Liguride units is at least partly contemporaneous with shortening and exhumation of Calabride units in the Sila Massif, with AFT ages of 18–13 Ma linked to top-to-the-E Longobucco thrusting (Vignaroli et al. Reference Vignaroli, Minelli, Rossetti, Balestrieri and Faccenna2012). The data thus suggest that the provenance change initiated during the Langhian reflects migration of the main area of exhumation, uplift and erosion from (N)W to (S)E, therefore shifting the paleo water divide eastward, causing an increase of Sila Unit-derived detritus at the expense of HP-LT metamorphic Liguride detritus.

5.d.2. Serravallian to Tortonian (14–7 Ma)

Deposition of Serravallian–Tortonian sediments directly followed the ca. 16–14 Ma (Langhian) peak in exhumation and relief formation caused by the Longobucco thrusting episode as constrained by tectonics reconstruction and thermal modelling (Vignaroli et al. Reference Vignaroli, Minelli, Rossetti, Balestrieri and Faccenna2012; Vitale et al. Reference Vitale, Ciarcia, Fedele and Tramparulo2019a). During this time frame, plutonic and Sila Unit rocks marked the highest relief of the region, creating a paleo water divide through these units from NW to SE northern Calabria, controlling the onset of sedimentation through all forearc basins in Serravallian time (Fig. 2).

This is best visible in the Crotone basin, where consistent input from Sila plutonic rocks in the west indicates sustained east-directed sediment transport, with only minor contributions from metamorphic rocks of the Sila nappe (Fig. 9b). In the Cirò basin, the data indicate a transition with time, from early Serravallian sediments resembling Crotone basin-like derivation from the Sila plutonics to Tortonian deposits increasingly incorporating material from the metamorphic Sila and Mandatoriccio Units, which are most prominent contributors to the Serravallian–Tortonian Rossano basin. This suggests progressive unroofing and erosion of deeper crustal units and/or widening of the drainage area due to decreasing relief (Olivetti et al. Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017). Serravallian–Tortonian Rossano and Tortonian Cirò basin samples thus share easterly drainage from the Sila and Mandatoriccio Units.

Input to the Catanzaro basin depends on sample locality: the eastern CatB-5 sample is dominated by N/NE to S/SE directed transport from the granitoids of the Sila Batholith, while the western CatB-10 sample contains proximal input from the Castagna/Bagni and Sila Units to the northwest and north, respectively. Following the end of Longobucco thrusting (Olivetti et al. Reference Olivetti, Balestrieri, Faccenna and Stuart2017), the Sila Massif remained topographically elevated, restricting input from distal sources and enhancing the delivery of plutonic material to the Crotone basin. Continued erosion through the late Serravallian and Tortonian led to the exposure of deeper crustal lithologies, reflected in the increased metamorphic grade of detritus deposited in the Cirò and Rossano basins.

5.d.3. Messinian (7-5 Ma)

Messinian sandstone samples exhibit striking similarities to the early Miocene, for instance, the high contribution of HP/LT metamorphic and mafic igneous minerals (Figs. 3 to 5) as well as apatite U–Pb age distributions (Fig. 8b). This suggests, erosion and decreasing topographic relief had returned the source regions, including the Sila Massif, to a pre-Longobucco thrusting configuration. Provenance data from the Rossano basin indicate a renewed influence of Liguride-derived sediments and SE-directed transport across northern-most Calabria, implying the Sila Massif no longer obstructed this drainage pathway (Fig. 9c). Although Sila and Mandatoriccio-derived material persists, its contribution is less important compared to Serravallian–Tortonian times. In the Catanzaro basin, the Castagna nappe becomes the principal sediment source for this time, alongside subordinate higher-grade metamorphic rocks of the Sila Unit.

6. Conclusions

The Miocene evolution of the northern Calabrian Arc provides new insights into the relationship between tectonically driven morphological changes including orogenic divide migration, and the reorganization of source-to-sink sediment routing pathways. Key observations include the presence of a high-pressure heavy-mineral assemblage (i.e., glaucophane, lawsonite and kyanite), mostly in the Rossano basin. This indicates sediment input from oceanic crustal rocks of the Liguride Complex of north-western Calabria and/or potential sourcing during the early Miocene from similar lithologies in the more distal Sardinia-Corsica block. While this high-pressure Liguride signal is minor in the Aquitanian, further decreasing and partly disappearing in the Burdigalian to Tortonian deposits, it becomes increasingly significant during the Messinian, alongside supporting garnet chemistry data. The Serravallian–Tortonian samples from the Crotone basin present a unique heavy-mineral assemblage dominated by andalusite, epidote, apatite and mainly metasomatic garnet. Consistent with predominant sourcing from the plutonic Sila Batholith and its contact aureole, additional apatite U–Pb ages (∼310–290 Ma) reflecting Variscan magmatism and rapid post-emplacement cooling further confirm this. A clear up-section transition in sediment provenance is observed within the Serravallian–Tortonian successions of the Cirò and Rossano basins. From a Crotone basin-like signature reflecting influence from the Sila Batholith, into a Rossano basin-like signal with increased input from metamorphic sources such as the Sila or Mandatoriccio-Bocchigliero Units. This provenance shift reflects progressive unroofing of the Sila Massif and the erosion of increasingly deeper Variscan crust and its associated metamorphic units. The Serravallian–Tortonian Catanzaro basin samples reveal a highly variable and spatially heterogeneous sediment provenance, controlled by a short distance, largely local, sediment supply.

These observations reveal changes in sediment routing through three main time intervals: the early to middle Miocene (23–14 Ma), the Serravallian to Tortonian (14–7 Ma) and the Messinian (7–5 Ma). These stages reflect: (i) an initial period of relative tectonic dormancy followed by thrusting, rapid exhumation and uplift; (ii) a phase of peak relief around Langhian to early Serravallian time accompanied by increased erosion, and the onset of Serravallian sedimentation; and (iii) continued erosion and landscape denudation, returning the region to a pre-thrusting morphology. Provenance data documents this progressive thrusting, unroofing and successive exposure of deeper crustal units throughout the Miocene. This study highlights, for an overall zircon-poor case, the value of integrating heavy-mineral, geochemical and geochronological datasets to better understand the dynamics of complex tectonic settings and their associated evolving provenance histories.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100411

Acknowledgements