People with schizophrenia have a two- to three-times higher premature mortality risk Reference Laursen, Nordentoft and Mortensen1 and a 12- to 45-times higher rate of suicide Reference Chan, Chan, Pang, Yan, Hui and Chang2,Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath3 compared with the general population. Other key primary causes of death are cardiovascular disease (CVD) and metabolic and infectious diseases. Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani‐Montez and Fairley4 About 15 to 30% of patients with schizophrenia do not respond to standard antipsychotics and are considered to have treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS). Reference Chan, Chan, Honer, Bastiampillai, Suen and Yeung5,Reference Siskind, Orr, Sinha, Yu, Brijball and Warren6 Clozapine has shown superior efficacy in improving psychiatric symptoms for TRS patients Reference Masuda, Misawa, Takase, Kane and Correll7,Reference Tiihonen, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Majak, Mehtälä, Hoti and Jedenius8 and is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of TRS. Reference Correll, Agid, Crespo-Facorro, de Bartolomeis, Fagiolini and Seppälä9 Clozapine has also been suggested to be effective in reducing suicidal behaviour in patients with schizophrenia. Reference Hennen and Baldessarini10 Despite the unique efficacy of clozapine, delays in clozapine initiation are common. Reference Howes, Vergunst, Gee, McGuire, Kapur and Taylor11,Reference John, Ko and Dominic12 Such delays have been found to be associated with poorer treatment outcomes Reference Shah, Iwata, Plitman, Brown, Caravaggio and Kim13 and are likely to be attributed to concerns about clozapine’s severe and potentially life-threatening side-effects. Reference Farooq, Choudry, Cohen, Naeem and Ayub14,Reference Zheng, Lee and Chan15 Therefore, evidence relating to the long-term association of clozapine with mortality is important. A meta-analysis of 24 studies reported a significant long-term reduction in all-cause mortality in patients continuously treated with clozapine compared with those continuously treated with other antipsychotics. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 However, some more recent studies have reported either no association between clozapine use and mortality risk Reference Katz, Szymanski, Marder, Shotwell, Hein and McCarthy17 or an increased mortality risk associated with clozapine use. Reference Zagozdzon, Dorozynski, Waszak, Harasimowicz and Dziubich18 Inconsistent and biased sample selection and lack of consideration of confounding factors may have contributed to the varied results and have led to concerns about the quality of the available evidence. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16,Reference van der Zalm, Termorshuizen and Selten19 Although there is a possible effect of clozapine in reducing suicide-related behaviour, Reference Hennen and Baldessarini10 meta-analyses have not found a significant effect of clozapine in reducing suicide. Reference Hennen and Baldessarini10,Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 This discrepancy is partly due to the limited number of studies focusing on these outcomes and the methodological limitations previously mentioned. Similarly, research on other specific causes of death, such as CVD, has also been limited and has yielded inconclusive results. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 Furthermore, despite the increased risk of clozapine-associated serious neutropenia, Reference Myles, Myles, Xia, Large, Kisely and Galletly20 inflammation Reference de Leon, Ruan, Verdoux and Wang21 and haematological malignancies, Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen, Bell, Dawson, Kataja and Taipale22 few studies have explored the potential association between clozapine use and infection- or cancer-related mortality. Hong Kong has universal healthcare coverage and the highest life expectancy in the world. Reference Ni, Canudas-Romo, Shi, Flores, Chow and Yao23 In the current study, we aimed to investigate the long-term associations of clozapine with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortalities – including suicide, CVD, infectious diseases and cancer – using a population-representative cohort of schizophrenia patients in Hong Kong, specifically focusing on the continuation of clozapine use. We also examined the impact of clozapine monotherapy versus polypharmacy on mortality risks, acknowledging that polypharmacy is common among clozapine-prescribed patients and may reflect illness severity.

Method

Data source

All data were retrieved from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) between 1 January 1999 and 31 March 2021. CDARS is a clinical data repository of electronic health records for all public hospitals managed by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority, including 43 public hospitals and 122 out-patient clinics. Reference Chai, Luo, Man, Lau, Chan, Yip and Wong24 The Hospital Authority is the primary in-patient and out-patient psychiatric service provider in Hong Kong, covering approximately 90% of psychiatric care for severe mental illness. Reference Chan, Chan, Pang, Yan, Hui and Chang2 All clinical data entry uses the same standardised format across all units to ensure consistency. A previous pharmaco-epidemiological study extensively validated the reliability of the CDARS data regarding psychiatric prescription and mortality information on the basis of its consistency with other data sources. Reference Zhou, Tang, Chan and Luo25 The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 20-854). All information was obtained anonymously from the electronic health records, and the requirement for patients’ written consent was waived. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline (Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10312). Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke26

Study design and participants

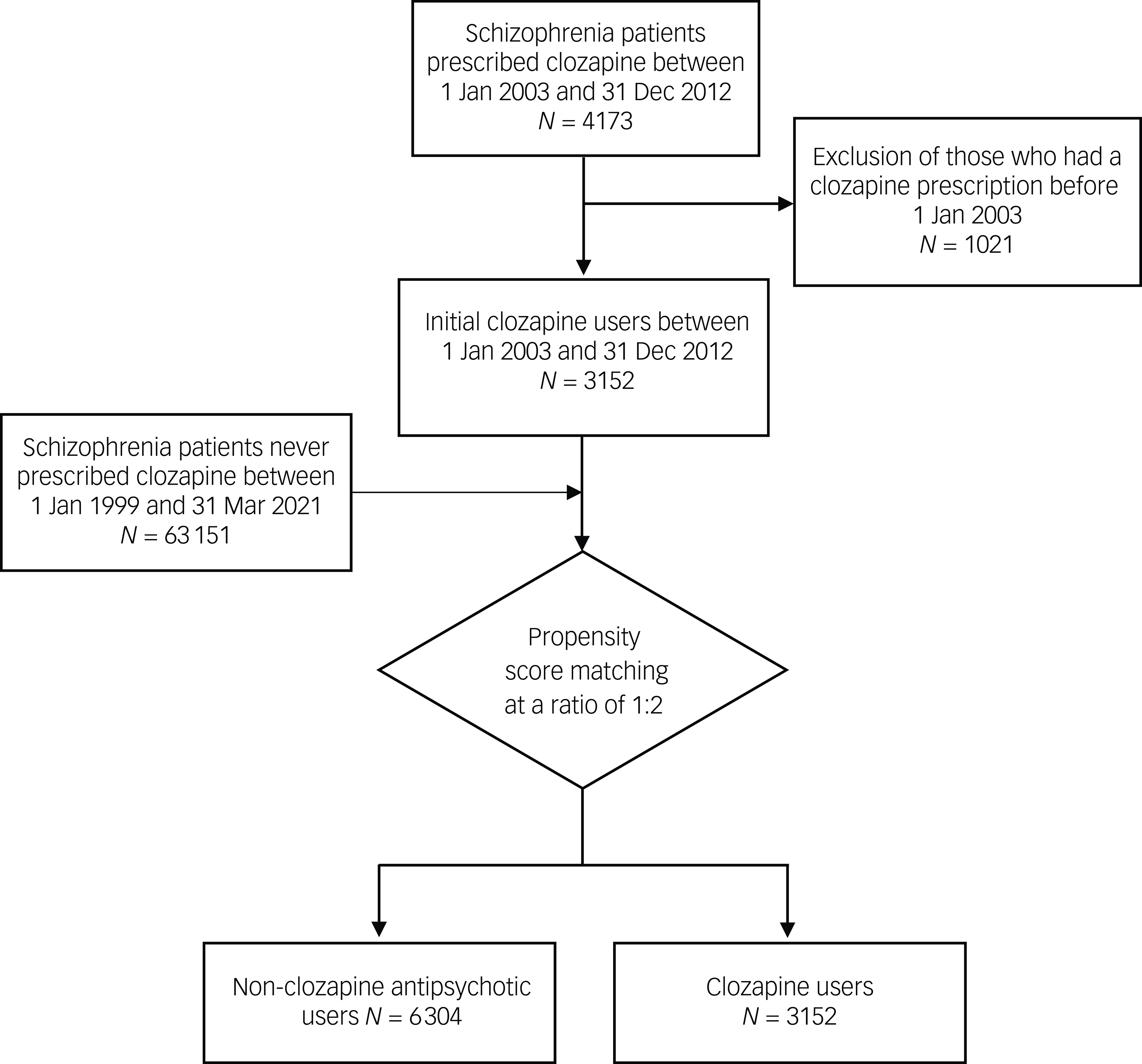

Clozapine users (ClozUs) were defined as patients who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295) and had their first clozapine prescription between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2012. The inclusion period was set to ensure a sufficient number of new clozapine users while allowing for an adequate duration of follow-up. Non-clozapine antipsychotic users (Non-ClozUs) were patients with the same diagnosis but no record of clozapine prescription before 31 March 2021. Basic demographic information (age, gender and educational level), relevant physical and psychiatric diagnoses, suicide attempts (identified using ICD-9-CM codes; Supplementary Table 1) and medication records of these individuals were obtained from the CDARS. The date of antipsychotic commencement was used as a proxy for the date of illness onset. The date of the first clozapine prescription was defined as the index date. The duration of illness before clozapine use was defined as the length between the illness onset date and the index date. The count of previous antipsychotics was the number of different types of antipsychotic used before the index date. Propensity scores were calculated on the basis of demographics, physical and psychiatric comorbidities, and suicide attempts before the illness onset date for each patient. Non-ClozUs were matched individually with each ClozU on the basis of propensity scores using a nearest neighbour matching algorithm without replacement to establish a 1:2 matched cohort of ClozUs and Non-ClozUs for the study (see Supplementary Method for details). The index date for each ClozUs (i.e. clozapine commencement date) was assigned as the index date for the matched Non-ClozUs. Non-ClozUs who died before the assigned index date or who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia for the first time after this date were excluded during matching. All participants were followed from the index date to 31 March 2021 or the date of death, whichever was earlier.

ClozUs were further categorised into continuous and discontinuous ClozUs. Reference Tiihonen, Lönnqvist, Wahlbeck, Klaukka, Niskanen and Tanskanen27 Continuous users were those prescribed clozapine for more than 90% of the entire observation period and within the last year before the end of the observation. Those who did not meet these criteria were considered to be discontinuous clozapine users. The same criteria were used to categorise the Non-ClozUs into continuous and discontinuous non-clozapine antipsychotic user groups. We also included a polypharmacy indicator for ClozUs to define whether clozapine was jointly prescribed with other antipsychotics for longer than 90 days within an uninterrupted period.

Outcomes

The outcomes were all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality, including deaths attributable to suicide, CVD, infection and cancer, identified using ICD-10-CM codes (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

We tabulated the sample characteristics at the index date and calculated the incidence rate of mortality per 100 person-years for the ClozU and Non-ClozU groups. Our preliminary analysis indicated that the hazard ratios of patients with and without clozapine prescription were not proportional; therefore, we applied an accelerated failure time (AFT) model with log-logistic distribution to estimate mortality risk associated with various types of clozapine use instead of Cox proportional hazards models. AFT models allow the effect of a covariate to accelerate or decelerate over the observational period; here, the use of such a model enabled estimationof the acceleration factors of survival time for different combinations of ClozUs (continuous versus discontinuous use and monotherapy versus polypharmacy) compared with Non-ClozUs for each study outcome. An acceleration factor greater than 1 indicated a prolonged survival time (i.e. a decreased hazard ratio for of mortality risk) compared with the reference group. Standardised mean differences were calculated to examine the covariate balance of all variables used for the propensity score calculation between continuous and discontinuous ClozUs and Non-ClozUs. Variables with a maximum pairwise standardised mean difference greater than 0.1 were further adjusted in the AFT models. As five outcomes were included in this analysis, we adjusted the significance level (0.05/5 = 0.01) and confidence intervals (99%) based on Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparison bias. A sensitivity analysis was performed by collapsing the continuous and discontinuous Non-ClozUs into one group as the reference group. To examine the robustness of the results, we repeated the analyses by shifting the entry period of the ClozUs cohort to between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014. The end of the observation period remained the same. To further examine the association between clozapine use and mortality risk, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis by modelling the percentage of clozapine use as a continuous variable. To account for competing risks, we used Gray’s test to compare cumulative incidence functions between groups and Fine–Gray models to estimate cause-specific mortality risks. The dplyr, tableone, cobalt, survival and SurvRegCensCov packages in R version 4.3.2 were used for data analysis.

Results

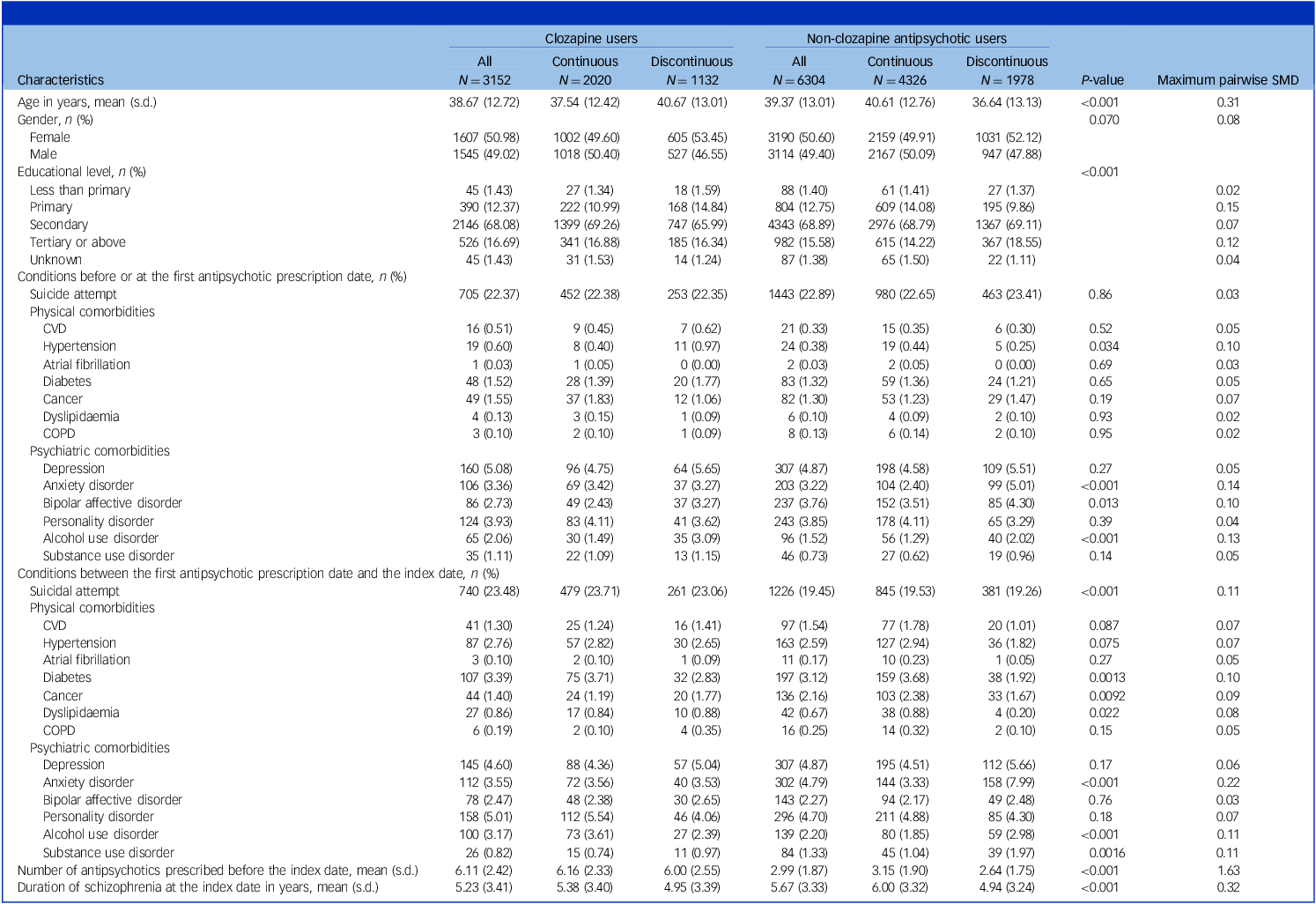

This study included a total of 9456 patients (50.73% females); 3152 ClozUs and 6304 matched Non-ClozUs (Fig. 1), with a mean age at index date of 39.13 years (s.d. = 12.92) and a median follow-up time of 12.37 years (interquartile range: 9.78–15.22 years). Among ClozUs, 2020 individuals (64.09%) were continuous users (mean age 37.54 years, s.d. = 12.42 years), and 1132 (35.91%) were discontinuous users (mean age 40.67 years, s.d. = 13.01). Among Non-ClozUs, 4326 (68.62%) individuals were continuous (mean age 40.61 years, s.d. = 12.76) and 1978 (31.38%) were discontinuous (mean age 36.64 years, s.d. = 13.13) antipsychotic users. Table 1 shows the sample characteristics at the index date, stratified by prescription pattern. Compared with Non-ClozUs, ClozUs had a higher prevalence of suicide attempts between the onset of illness and index date (23.48% v. 19.45%) and a higher number of antipsychotic drugs prescribed before the index date (6.11 [s.d. = 2.42] v. 2.99 [s.d. = 1.87]). No substantial difference in the prevalence of comorbidities was observed between groups, except for anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder. The mortality incidence rate was stratified by clozapine prescription (Supplementary Table 2). The all-cause mortality rates per 100 person-years were 1.11 (95% CI: 1.01–1.21) for ClozUs and 1.13 (95% CI: 1.06–1.21) for Non-ClozUs. ClozUs exhibited a lower suicide mortality rate (incident rate ratio 0.73; 95% CI: 0.55–0.98) but a higher infection-related mortality rate (incidence rate ratio 1.40; 95% CI: 1.10–1.78) compared with Non-ClozUs. Supplementary Table 3 shows a list of the antipsychotics prescribed to ClozUs when clozapine was discontinued. Olanzapine was the antipsychotic drug most frequently prescribed after clozapine (69.88%), followed by haloperidol (54.86%).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the sample selection.

Table 1 Sample characteristics at the index date (i.e. the date of the first clozapine prescription)

CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SMD, standardised mean difference.

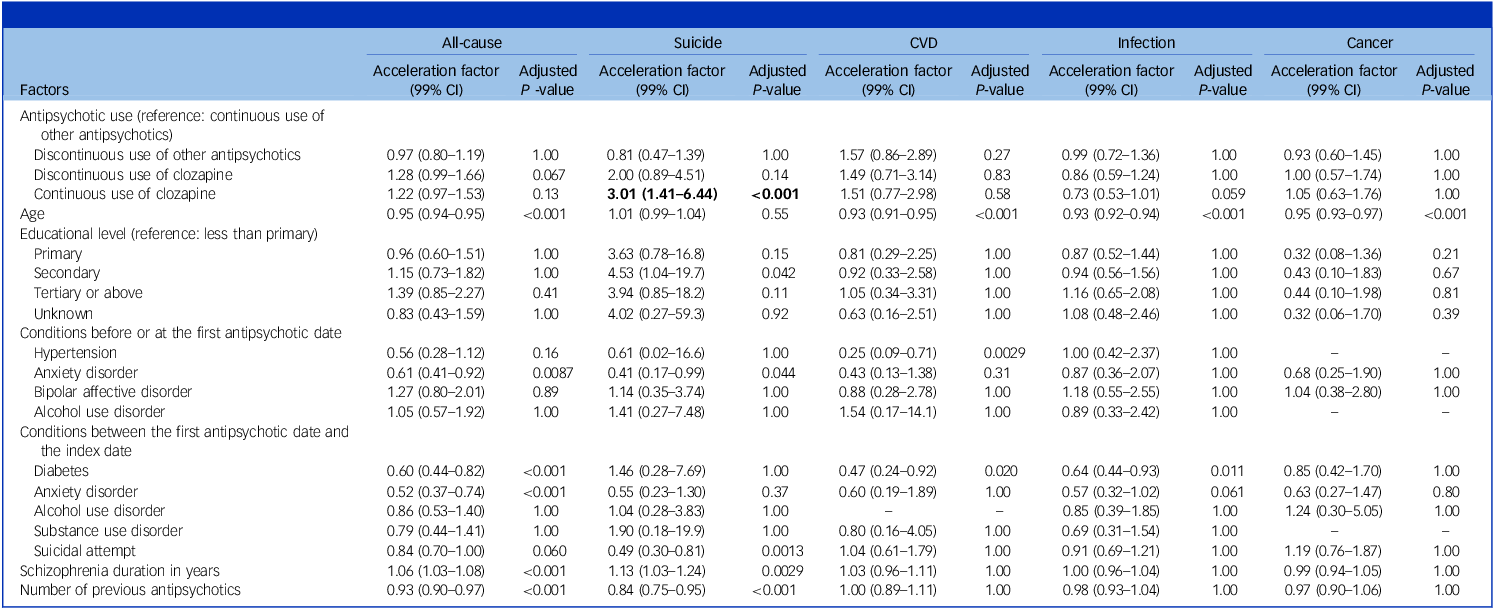

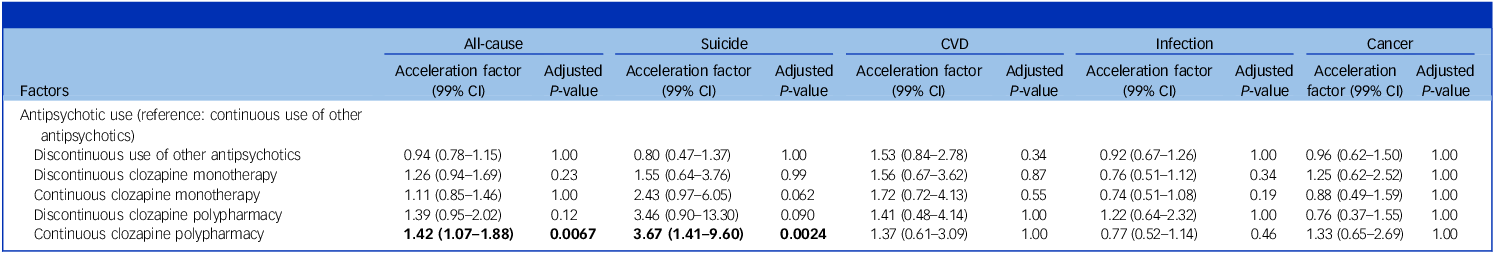

Table 2 shows the estimation results of five AFT models examining the associations between various types of antipsychotic prescribing and causes of mortality, adjusting for covariates that were imbalanced. Compared with continuous prescription of other antipsychotics in Non-ClozUs, continuous clozapine prescribing was associated with longer survival time (and lower risk of mortality) for suicide only (acceleration factor 3.01; 99% CI: 1.41–6.44). Although no association was observed for all-cause mortality or other causes of mortality, there was a higher risk of infection-related mortality (acceleration factor 0.73; 99% CI: 0.53–1.01), which approached statistical significance before Bonferroni correction. Table 3 shows the results of another five AFT models, which further accounted for whether other antipsychotic drugs were co-prescribed with clozapine during the same period. Continuous clozapine prescribing remained associated with longer survival time for suicide compared with the reference group. However, the association was mainly observed in those who were prescribed other antipsychotics (acceleration factor 3.67; 99% CI: 1.41–9.60). Besides, continuous ClozUs co-prescription with other antipsychotics was also associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality (acceleration factor 1.42; 99% CI: 1.07–1.88). A list of other antipsychotics co-prescribed with clozapine is shown in Supplementary Table 4, and a detailed comparison of baseline characteristics and sample sizes for clozapine monotherapy, clozapine polypharmacy and Non-ClozUs is shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Table 2 Risk of mortality associated with continuous and discontinuous use of clozapine compared with continuous use of other antipsychotics among participants recruited between 2003 and 2012a

a. Accelerated failure time models were controlled for 13 imbalanced covariates of 33 covariates (standardised mean difference > 0.1; i.e. age, educational level, hypertension, anxiety disorder, bipolar affective disorder and alcohol use disorder before or at the first antipsychotic date; diabetes, anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder and suicide attempt between the first antipsychotic date and the index date; schizophrenia duration; and number of previous antipsychotics). The bold text indicates statistically significant results.

Table 3 Risk of mortality associated with clozapine monotherapy and polypharmacy compared with continuous use of other antipsychotics among participants recruited between 2003 and 2012a

a. Accelerated failure time models were controlled for 22 imbalanced covariates of 33 covariates (standardised mean difference > 0.1; i.e. age, gender, educational level, hypertension, cancer, anxiety disorder, bipolar affective disorder, alcohol use disorder and substance use disorder before or at the first antipsychotic date; cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, dyslipidaemia, depression, anxiety disorder, personality disorder, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder and suicide attempt between the first antipsychotic date and the index date; schizophrenia duration; and number of previous antipsychotics). The bold text indicates statistically significant results.

In the sensitivity analysis which treated Non-ClozUs as a combined reference group (Supplementary Table 6), both continuous clozapine use (acceleration factor 1.32; 99% CI: 1.02–1.70) and discontinuous clozapine use (acceleration factor 1.26; 99% CI: 1.01–1.57) were associated with longer survival time for all-cause mortality. Other results remained consistent. In the sensitivity analysis which shifted the cohort entry period of ClozUs by 2 years to between 2005 and 2014, 3107 ClozUs and 6214 Non-ClozUs were identified (Supplementary Fig. 1). Supplementary Table 7 shows basic demographics and clinical variables, and Supplementary Table 8 shows the mortality rates of each group. We similarly found that continuous clozapine use (acceleration factor 3.64; 99% CI: 1.49–8.90) was associated with a prolonged survival time for suicide mortality compared with continuous use of other antipsychotics. Both continuous clozapine polypharmacy (acceleration factor 3.45; 99% CI: 1.13–10.40) and clozapine monotherapy (acceleration factor 4.03; 99% CI: 1.33–12.20) were associated with prolonged survival time for suicide mortality (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). In the sensitivity analysis treating clozapine use as a continuous variable, higher percentage of clozapine use (see distribution in Supplementary Fig. 2) was associated with longer survival time for suicide mortality (acceleration factor 2.99, 99% CI: 1.46–6.08) (Supplementary Table 11). The marginal association between clozapine use and infection-related mortality was not observed in the shifted cohort (Supplementary Table 9). However, continuous ClozUs showed significantly higher infection-related mortality risk after competing risks had been accounted for (hazard ratio 1.68; 99% CI: 1.05–2.69). Gray’s test results are detailed in Supplementary Tables 12 and 13. Other associations remained consistent with the findings of the main analyses (Supplementary Tables 14 and 15).

Discussion

In this cohort study of 9456 patients with schizophrenia and a median of 12 years of observation conducted in Hong Kong, we found that continuous clozapine use was associated with a lower risk of suicide mortality compared with continuous use of other antipsychotics. No significant associations were observed between continuous clozapine use and all-cause mortality or CVD-related or cancer-related mortality, although a marginal increase in infectious-disease-related mortality was seen. Furthermore, the continuous clozapine polypharmacy group had significantly lower risks of both suicide mortality and all-cause mortality. There was marginal significance for the continuous clozapine monotherapy group having a lower risk of suicide mortality. Similar results were found in sensitivity analyses in which the identification period for ClozUs was shifted by 2 years.

The all-cause and suicide mortality rates of ClozUs and Non-ClozUs were slightly higher than those found in previous studies, Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 consistent with our previous findings locally. Reference Chan, Chan, Pang, Yan, Hui and Chang2 By contrast, CVD-related mortality rates were lower than suicide mortality rates, a difference that can probably be explained by the relatively young age of our cohort, consistent with previous studies. Reference Yung, Wong, Chan, Chen and Chang28 Coding bias may also have contributed to this observation, as the direct cause of death is often recorded rather than the underlying cause. Reference Harriss, Ajani, Hunt, Shaw, Chambers and Dewey29 Continuous ClozUs were found to have a significantly lower risk of suicide mortality compared with continuous Non-ClozUs. The results remained the same in the sensitivity analysis. These results accounted for basic demographics and important clinical variables such as physical and psychiatric comorbidities, duration of illness and the number of different antipsychotics used. In fact, the continuous Non-ClozUs had an average of 6 years of schizophrenia illness and three different antipsychotic medications used before the index date, suggesting compatible chronicity between the comparator group and the clozapine group. Therefore, our results showing an effect of continuous clozapine use in reducing suicide mortality are relatively robust, adjusting for chronicity. Continuous ClozUs were defined in the study as individuals prescribed clozapine for 90% or more of the follow-up period (mean of 12 years) and the whole preceding year of follow-up. Although about two-thirds of the ClozUs fulfilled these relatively stringent criteria, the study’s results might have been biased towards a group of individuals with long-term adherence to clozapine treatment. This performance bias has been suggested as one explanation for the superior effectiveness of clozapine. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16,Reference Meltzer, Alphs, Green, Altamura, Anand and Bertoldi30 The superior efficacy of clozapine in alleviating psychotic symptoms and depressive symptoms Reference Khokhar, Henricks, Sullivan and Green31,Reference Taipale, Lähteenvuo, Tanskanen, Mittendorfer-Rutz and Tiihonen32 and its efficacy in controlling aggressive and impulsive behaviour Reference Taipale, Lähteenvuo, Tanskanen, Mittendorfer-Rutz and Tiihonen32 might also contribute to its effects in reducing suicide and death. In fact, a possible anti-suicide effect of clozapine has also been shown in people with bipolar and borderline personality disorders. Reference Han, Allison, Looi, Chan and Bastiampillai33,Reference Masdrakis and Baldwin34 Nevertheless, the actual underlying mechanisms of the anti-suicide effect of clozapine are not fully elucidated.

Compared with Non-ClozUs (continuous and discontinuous) as one comparator group, both ClozU groups (continuous and discontinuous) were found to have longer survival for all-cause mortality. However, when they were compared with the continuous Non-ClozUs, no significant effect on longer survival for all-cause mortality was found for either ClozU group. On the other hand, the continuous clozapine polypharmacy group had significantly longer survival for all-cause and suicide mortality compared with the continuous Non-ClozUs. These varied results among different groups suggest that varied characteristics of antipsychotic use may have contributed to the inconsistent results reported in the literature. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 The relatively consistent effect of continuous clozapine use on suicide mortality in our study supports the exposure–response relationship of clozapine effectiveness; Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16 that is, continuous use of clozapine is most beneficial for prolonging life expectancy, and such an effect seems to be lost when clozapine is discontinued. In fact, patients discontinuing clozapine were found to have increased mortality risk compared with patients never treated with clozapine. Reference Wimberley, MacCabe, Laursen, Sørensen, Astrup and Horsdal35 Clozapine is used for patients with TRS. Reference Chan, Chan, Honer, Bastiampillai, Suen and Yeung5 For those patients not responding to clozapine, adding another antipsychotic medication is a possible treatment strategy. Reference Luykx, Gonzalez-Diaz, Guu, van der Horst, van Dellen and Boks36,Reference Siskind, Siskind and Kisely37 The continuous clozapine polypharmacy group might thus represent clozapine-resistant patients, and the longer survival time of this group of patients for all-cause mortality may indicate the importance of adequate pharmacological treatment and a possible benefit of polypharmacy in patients with TRS. Reference Tiihonen, Taipale, Mehtälä, Vattulainen, Correll and Tanskanen38 A recent nationwide cohort study further suggested that when the total daily antipsychotic dose is higher than the 1.1 standard, polypharmacy is associated with a significantly lower risk of physical incidents leading to hospital admission. Reference Taipale, Tanskanen and Tiihonen39

Studies of the effects of clozapine on death related to CVD have been limited and have generated conflicting results. Reference Taipale, Tanskanen, Mehtälä, Vattulainen, Correll and Tiihonen40,Reference van der Zalm, Foldager, Termorshuizen, Sommer, Nielsen and Selten41 Although a higher risk of haematological malignancies has been found with long-term clozapine use, Reference Tiihonen, Tanskanen, Bell, Dawson, Kataja and Taipale22 the overall evidence with respect to an association between clozapine and cancer-related mortality is limited. Our study identified no significant association between clozapine use and CVD- or cancer-related mortality. One possible explanation for this is the comparatively lower incidence of these causes of death. On the other hand, our study identified a marginally significant increase in infectious-disease-related mortality among continuous ClozUs. Although this association was not significant in the shifted cohort, it reached statistical significance after competing risks had been accounted for in the Fine–Gray model. The small number of events might also be an explanation for the unstable findings. Nonetheless, a recent meta-analysis revealed a four-fold higher risk of overall infectious-disease-related mortality in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general public, Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani‐Montez and Fairley4 and clozapine is specifically related to inflammation, Reference Leung, Zhang, Markota, Ellingrod, Gerberi and Bishop42 particularly at high dosage levels. Reference de Leon, Schoretsanitis, Smith, Molden, Solismaa and Seppälä43 Therefore, close monitoring of clozapine levels is needed for those with signs of infection. Reference Clark, Warren, Kim, Jankowiak, Schubert and Kisely44

Study strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was its comprehensiveness, given its use of population-based data and median follow-up of 12 years. Furthermore, extensive measures were used to ensure comparability between the comparator and clozapine groups to reduce survival treatment bias, and sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure the replicability of the results. For example, previous studies have often solely considered in-patient populations Reference Chen, Chen, Pan, Su, Tsai and Chen45 or used medication records restricted to out-patient settings, Reference van der Zalm, Foldager, Termorshuizen, Sommer, Nielsen and Selten41 leading to inconsistent results. In addition, most cohort studies have not accounted for the timing of clozapine initiation or the duration of illness in the comparators; this may have introduced survivor treatment bias. Reference De Leon, Sanz and De Las Cuevas46 Important confounding factors such as the presence of physical conditions before commencing treatment and demographic information have typically not been included in previous studies, resulting in only a crude mortality rate for comparison. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan16,Reference van der Zalm, Termorshuizen and Selten19

However, the low number of events for some causes of death may have limited the power of the present study; this represents one of its main limitations. Although occurrences of mortality in CDARS records were verified with the government population registry record, Reference De Leon, Sanz and De Las Cuevas46 the coding of cause-specific mortality relies on clinical documentation and may be underreported. Moreover, medication information from CDARS was based on prescription data without information on actual medication usage, and other important factors related to mortality, such as family history and socioeconomic and lifestyle-related information, were not taken into consideration. Furthermore, study sample characteristics, patterns of clozapine use and the healthcare model might have varied across different regions and cultures, Reference Wong, Root, Douglas, Chui, Chan and Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie47,Reference Wagner, Siafis, Fernando, Falkai, Honer and Röh48 which may limit the generalisability of the results. Although the same clinical governance applied to all public psychiatric units in Hong Kong, possible heterogeneity between the units may limit interpretation of the results. Owing to the need for anonymity in data collection, the design of the current study did not enable us to understand the varied effects of different psychiatric units or perform within-subject assessment of the relationship between clozapine use and mortality risk.

Clinical implications

This study offers robust evidence supporting the protective effect of continuous clozapine use in reducing long-term suicide mortality among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Therefore, clozapine may be especially beneficial in patients with schizophrenia who are at high risk of suicide. An effect of reducing all-cause mortality was also seen in continuous clozapine polypharmacy users. These results add to existing evidence regarding the effectiveness of clozapine beyond its antipsychotic effects, particularly anti-suicide effects, and emphasise the need for continuous clozapine use for suitable patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10312

Data availability

The CDARS is managed by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. The Hospital Authority Data Sharing Portal provides various access channels to Hospital Authority data for research purposes. The relevant information can be found online at https://www3.ha.org.hk/data.

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Eric Blyth for proofreading.

Author contributions

H.Z. and S.K.W.C. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. H.L. and S.K.W.C. are co-corresponding authors. Study design: H.Z., H.L. and S.K.W.C. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: H.Z., H.L., J.Y.-M.T., J.Z. and S.K.W.C. Drafting of the manuscript: H.Z., H.L. and S.K.W.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H.Z., J.Y.-M.T., W.G.H., T.B., W.C.C.C., S.S.Y.L., E.H.M.L., H.T., H.L. and S.K.W.C. Research funding acquisition and research question conceptualisation: S.K.W.C. Administrative, technical or material support: J.Y.-M.T., E.H.M.L., H.L. and S.K.W.C. Supervision: W.G.H., T.B., H.T., H.L. and S.K.W.C.

Funding

General Research Fund of the University Grants Committee Hong Kong to S.K.W.C. (ref: 17111922). The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interest

W.G.H. is a consultant to Bochringer Ingelheim, Otsuka and AbbVie. H.T. has participated in research projects funded by Janssen and has received personal fees from Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck and Otsuka.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.