Introduction

Non‐legislative and technical modes of policy making are becoming more prominent in global politics, with unelected decision‐makers heavily relying on private sector interests for expert and technical input (Büthe & Mattli, Reference Büthe and Mattli2011; Mattli & Woods, Reference Mattli and Woods2009). The decisions made are allegedly driven by relevant information and scientific assessments, rather than partisan‐motivated considerations. But the provision of expertise is not value neutral, and such policy making can have important distributional implications. Notably, corporate interests have much to lose if compliance with international standards requires making considerable changes to existing practices. Seemingly technical policies can entail controversial choices and feature intense debates, calling for a systematic analysis of politicisation.

Broadly considered, politicisation refers to the expansion of the scope of conflict in society (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960, p. 7), making a matter a subject of debates and/or contestation (De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012, p. 139; de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016, p. 17). The concept of politicisation has become an important subject in academic debates, particularly regarding European Union (EU) governance and questions about the bloc's democratic legitimacy (e.g., de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016; Statham & Trenz, Reference Statham and Trenz2013, Reference Statham and Trenz2015). In a large n‐study, Hutter et al. (Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016) investigate the politicisation of European integration and point out the ‘politicising effect’ of specific moments, like the Euro crisis in 2008. In the public policy literature, these moments can be referred to as ‘focusing events’. The contributions of focusing events to the development of public policy have been widely addressed (e.g., Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993; Birkland, Reference Birkland1997, Reference Birkland1998, Reference Birkland2006; Nohrstedt, Reference Nohrstedt2008). Nevertheless, missing from the literature is an examination of the role of focusing events within more technical and specialised regulatory venues, with few elected actors (if at all), and, thereby, voters. Despite a rich body of literature on politicisation as well as focusing events, we still know very little about the potential impact of focusing events on politicisation outside the EU context (Zürn, Reference Zürn2016) and beyond the electoral arena.

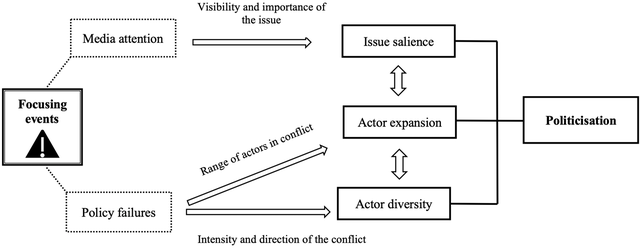

This paper seeks to examine the extent to which focusing events contribute to politicisation within global and seemingly technical venues. I conceptualise politicisation as a combination of three key components: (1) issue salience (the amount of attention given to the issue), (2) actor expansion (the number of participants in debates) and (3) actor diversity (the degree of diverse interests represented in debates). My central argument is that focusing events largely contribute to politicisation in technical arenas by raising public attention and revealing potential policy failures.

To examine this, I narrow the empirical focus of this analysis to one critical and far‐reaching global policy issue: internet privacy regulation.Footnote 1 An encompassing global regulatory regime regarding internet privacy has not yet evolved (Feick & Werle, Reference Feick, Werle, Baldwin, Cave and Lodge2010). Instead, the patchwork of standards and guidelines that do exist have mostly been issued by leading (but little‐known) internet regulatory agencies, namely: the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C are private–public international organisations, which are not established through international treaties as independent government bodies. They are thus distinct from independent regulatory agencies like the European Food Safety Authority. They are, nevertheless, expert bodies prescribing the quality of given practices and procedures, which is in line with the common definition of regulation (Büthe & Mattli, Reference Büthe and Mattli2011). The rules set by these agencies are indispensable for the internet to perform, as they allow multiple systems and electronic devices to exchange information. They can furthermore allow or restrict the design of systems and computer programs that address data protection's practical needs. I examine the effect of three focusing events on internet privacy regulation: the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, the global surveillance revelations made by Edward Snowden in 2013 and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018.

In terms of methodology, I map the politicisation process of internet privacy regulation using a large‐scale and systematic media analysis of 20 critical policy recommendations (i.e., internet standards and guidelines) adopted by ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C. I collect data on the internet policies selected for this study over a 20‐year period, resulting in an original dataset of 2,100 news articles. Although the present analysis focuses on internet privacy regulation, the effect of focusing events on politicisation can be generalised beyond this particular case to the politicisation of other issues developed by seemingly technical expert bodies, like in finance.

My analysis reveals that focusing events contribute to politicisation within global and seemingly technical venues, in particular regarding the actors involved in conflict. This paper's contribution to the literature is thus threefold. Firstly, this paper deepens our understanding of the extent to which focusing events affect politicisation. Importantly, it does so by focusing on policies and venues less covered by existing research and where politicisation is least likely to occur given the technicality of the policy area. Politicisation and its driving forces are an important object of research as the concept of politicisation suggests that debates involving a growing range of actors take place, which is a key ingredient of democratic politics. Secondly, the present research extends the predominantly European governance‐centred literature on politicisation by applying this concept to a global public policy issue. The internet continues to become further integrated into all aspects of the global culture and economy, making data protection and internet privacy the most pressing policy issues of the contemporary era. Thirdly, and closely related to the previous points, the empirical findings shed light on the structure of political conflict over internet regulatory agencies’ decisions. This is critical as, to an important extent, ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C work beyond the purview of democratic accountability, delegating decision‐making powers to unelected regulators. The findings thus contribute to the broader academic debate on the legitimacy of global forms of governance. In what follows, I first review the driving forces of politicisation suggested by the existing literature and develop a theoretical model to explain how focusing events also affect politicisation, particularly within technical venues. I then describe my methods and present the findings of the analysis. I conclude with remarks about their implications and avenues for future research.

Politicisation and its driving forces

Existing approaches to politicisation

Two objects of politicisation can be distinguished, specifically: the polity and the policy. The polity refers to the institutional system, whereas the policies are the solutions provided to solve problems (De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012, p. 140). An issue (i.e., polity or policy) is regarded as politicised when a growing range of actors with diverse preferences get involved in debates over that issue, expanding the scope of conflict (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2017; De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1984; Leupold, Reference Leupold2015). Politicisation can thus be seen as a combination of three components: issue visibility (referred to as salience), actor expansion (Grande & Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2014, Reference Grande and Hutter2016; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016) and actor diversity (Masini & Van Aelst, Reference Masini and Van Aelst2017; Pagliari & Young, Reference Pagliari and Young2016). Whereas polity politicisation is associated with debates over the overall legitimacy of supranational decision making, policy politicisation relates to debates on societal matters (Leupold, Reference Leupold2015, p. 86). The two, however, are closely linked as policy politicisation can lead to broader struggles over the appropriateness of the institutional order and thereby move to polity politicisation (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016). Politicisation being defined, I now point out the driving forces behind this process.

Politicisation can occur at several political levels, which, although they are distinct, interact with each other. One strand of literature supports a society‐based perspective. It suggests that the rise in the standard of living fosters the involvement of citizens (i.e., all actors that are non‐decision makers) in debates (Inglehart & Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Tarrow, Reference Tarrow1998). More specifically, better education and more sophisticated mass media enhance individuals’ ability and interest in participating in debates over various policy issues. Initially, this process occurs at the national level, but in the age of globalisation, these mechanisms are taken at the global level and drive global politicisation patterns (Furia, Reference Furia2005).

The accumulated effects of authority transfers at the global level are also considered by the literature as a key determinant of politicisation (e.g., De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012; Zürn et al., Reference Zürn, Binder and Ecker‐Ehrhardt2012; Rixen & Zangl, Reference Rixen and Zangl2013; Ecker‐Ehrhardt, Reference Ecker‐Ehrhardt2014; Grande & Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2016; Rauh & Zürn, Reference Rauh and Zürn2020). The rationale being that the transformation of an international institution like the EU ‘into a more encompassing political system’ (Grande & Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2016, p. 23) increases debates over the institution's procedures as well as policies. However, these authority transfer effects interplay with sub‐levels. Research indeed suggests that they can be filtered by additional factors, such as national economic structures (e.g., Leupold, Reference Leupold2015) or domestic politics (e.g., Ecker‐Ehrhardt, Reference Ecker‐Ehrhardt2014; Hoeglinger, Reference Hoeglinger2016), hence explaining cross‐national divergences in politicisation (e.g., De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2016; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Rauh et al., Reference Rauh, Bes and Schoonvelde2020). Institutional context also matters as the rules and incentives under which actors can express their preferences (like consultation procedures) expand or limit the scope of conflict (De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012; Häge & Naurin, Reference Häge and Naurin2013).

Broadly considered, another strand of research specifically focuses on the strategies of political actors to account for politicisation (e.g., Koopmans et al., Reference Koopmans, Statham, Giugni and Passy2005; De Bièvre, Reference De Bièvre2018; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019), encompassing the literature on outside lobbying dynamics (e.g., Kollman, Reference Kollman1998; Beyers, Reference Beyers2004; Dür & Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014). The explanation is that the expansion of conflict is strategically pursued by certain actors to favour their policy preferences. For instance, De Bièvre (Reference De Bièvre2018) provides evidence that the politicisation of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership in Germany is primarily driven by wealthy NGOs.

Existing research has thus demonstrated that institutional and structural factors, as well as actors’ strategies, are important determinants of politicisation. The role of events is, however, less clear‐cut. Studies on EU politicisation suggest that specific moments, such as the Euro crisis in 2008, have intensified political conflict (e.g., Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Leupold, Reference Leupold2015; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019), but more theory is still needed to understand the impact of focusing events. Furthermore, little scholarly attention has been paid to the role of events within more technical venues (e.g., standard‐setting bodies, technical committees). The role of events must not be overstated yet. Politicisation can already be in process when an event occurs, and that event may then be used as a politicisation strategy. But even in that case, focusing events are still critical forces that expand further the scope of conflict. I elaborate on this argument in what follows.

The effect of focusing events

Although a focusing event is a key concept in public policy studies, there is no agreement on a common terminology. While Kingdon describes a focusing event as a “little push” (Reference Kingdon2003, p. 94) and includes fatal accidents but also personal experiences of policy makers, Downs conceptualises focusing events as an ‘alarmed discovery’ of a problem by the public (1972, p. 39). Examples of focusing events usually include natural disasters, industrial accidents, as well as scandals. Birkland's definition is often used by political science scholars as his definition is broad enough to cover different types of events while also narrow enough to not simply cover anything that happens. Birkland defines a focusing event as

An event that is sudden; relatively uncommon; can be reasonably defined as harmful or revealing the possibility of potentially greater future harms; has harms that are concentrated in a particular geographical area or community of interest; and that is known to policy‐makers and the public simultaneously. (Birkland, 1997, p. 54)

Birkland's definition underscores that not all events can be described as focusing; the crucial traits are suddenness and implied harm. As a result of these traits, focusing events can contribute to politicisation in technical arenas. Specifically, they can increase the visibility of a given issue, the range of actors in conflict over that issue and the intensity of conflict, through two main mechanisms, as displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

The first mechanism relates to media attention. Specifically, focusing events attract media attention, putting the spotlight on existing, but out‐of‐sight, issues. This leads to increasing their salience, making ‘quiet politics loud’ (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015; Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2010; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013). Salience generally refers to the level of public attention, hence importance, given to a specific issue (Oppermann & Viehrig, Reference Oppermann and Viehrig2009). The impact of focusing events on salience is notably suggested by public policy theories, in particular the multiple streams framework (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1984), the issue‐attention cycle model (Downs, Reference Downs1972) and the punctuated equilibrium theory (Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). Through this first mechanism, media play a critical role, particularly in the news selection processes (Boydstun et al., Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrav2014). This role would require further investigation, but the assumption here is that focusing events attract media attention primarily because of their implied harm. Events can thus propel seemingly technical policies and corresponding technical debates into the public spotlight.

Salience in turn affects the configuration of actors in conflict. Indeed, when an issue becomes more salient, more actors feel concerned and enter the conflict (Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). Regarding internet privacy regulation, this can imply that large technology companies like Microsoft are joined in debates by smaller technology companies. However, the concept of focusing events is not about ‘attention‐grabbing’ events only. Issues may be salient in media debates but may not attract political contestation. Looking at issue salience only disguises the magnitude and character of the conflict. It is thus important to consider another mechanism that links focusing events to politicisation.

The second mechanism is associated with the policy failures revealed by the event. Focusing events reveal (perceived) policy failures as well as potential future failures, and, in this regard, they symbolise everything that is wrong (Birkland, Reference Birkland1998). This means they serve as an impetus for actors to promote competitive alternative ideas, challenging the policy status quo and the dominant coalition defending the status quo (Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). This is important as the concept of politicisation involves that the actors engaged in debates represent different positions (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016, p. 20; van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Berkhout and Ruedin2015, p. 2). By revealing policy failures, focusing events affect the substance of politicisation, that is, the existing ‘policy paradigm’ (Hall, Reference Hall1993). A policy paradigm is a set of ideas that structure public policies in terms of overall goals as well as instruments enabling the reaching of those goals. As Hall points out, policy failures, which can be revealed by focusing events, ‘gradually undermine the authority of the existing paradigm and its advocates’ (Reference Hall1993, p. 290). Policy failures thus lead to increasing the number of actors engaged in debates as well as the interests and opinions expressed. In the case of internet governance and technical privacy rules specifically, this suggests the inclusion of non‐technology actors in debates. Indeed, internet regulation primarily engages technology companies (Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020; DeNardis, Reference DeNardis2014), which operate in the design and installation of computer hardware components as well as software applications. In contrast, non‐technology actors include companies operating in various sectors as well as governmental organisations and non‐state actors. At the same time, the increase in the number and range of actors can also increase the issue salience. It should be noted that the potential shift to new policy arrangements then depends on further conditional factors that are not the focus of this paper. Instead, the emphasis here is on the scope of political conflict over existing policy arrangements in technical arenas. The points mentioned here lead to a central hypothesis:

The presence of a focusing event contributes to politicisation in technical arenas.

Research design

Data selection: internet privacy rules and focusing events

This paper aims to test the effect of focusing events on politicisation at the global level and within seemingly technical venues. In this section, I provide details on the cases selected as well as the variables considered in the analysis and their operationalisation.

Internet governance is often seen as ‘an arcane and even marginal topic, of interest primarily to a few geeks’ (Verhulst et al., Reference Verhulst, Noveck, Raines and Declercq2014, p. 96), or to technology companies (Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020; DeNardis, Reference DeNardis2014). Still, the last decade has shown a shift toward greater attention to internet governance, specifically regarding data protection and internet privacy regulation (Culpepper & Thelen, Reference Culpepper and Thelen2020, p. 304). The design of data protection and internet privacy rules seems now to spark the interest of various companies, international organisations and a broad range of non‐state actors, suggesting this issue has become politicised. Yet no empirical analysis has been produced, to date, on this matter.

The selection of focusing events raises some challenges as there is no agreement on a common terminology. Nevertheless, three focusing events seem to be particularly relevant regarding global internet privacy regulation, namely: the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, the Edward Snowden revelations in 2013 and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018. Three reasons explain the selection of these events. First, the three events involved issues associated with internet privacy regulation. Although privacy and security issues were not new (Bennett, Reference Bennett1992), the terrorist attacks substantially shifted the emphasis of the public discourse from privacy to security needs while raising questions regarding the emerging new technologies and their regulation (Levi & Wall, Reference Levi and Wall2004, p. 195). In contrast, the Edward Snowden revelations and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal put the spotlight on illegal surveillance activities operated by states and businesses, leading to public debates on the level of privacy protection required against surveillance and illegal data collection (Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020; Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019; Pohle & Van Audenhove, Reference Pohle and Van Audenhove2017). Other important events involved data protection and privacy issues, such as the AOL Search Leak (in 2003), Google Street View scandal (in 2007), World scandal (in 2011), where journalists ‘hacked’ into digitally stored personal data. However, compared to these privacy‐related events, the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Edward Snowden revelations and the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal received substantial coverage in media all around the world, suggesting an impact at the global level. This is the second reason explaining the selection of the three events. Worldwide media coverage does not mean that the events have affected all countries similarly and with the same intensity. The US‐centred nature of the events might, in fact, lead to stronger debates in this country. Third, widespread media coverage also indicates that the events selected are severe enough to be defined as harmful, which aligns with Birkland's definition of a focusing event (Reference Birkland1997). Table A1 in the online Appendix provides details on the characteristics and media coverage of the events.

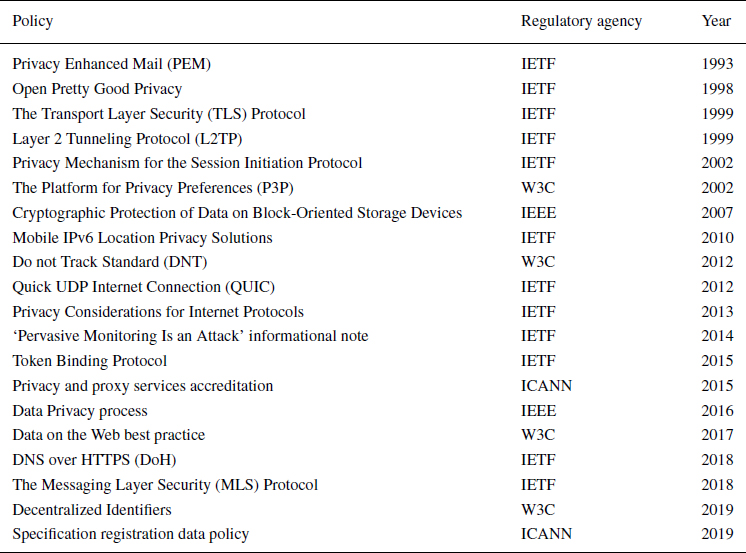

To analyse the effect of focusing events on the politicisation of internet privacy regulation at the global level and within seemingly technical venues, I select 20 internet policies adopted by global regulatory agencies between 1990 and 2019. They are mostly standards and guidelines, which are common arrangements of global regulation (Mattli & Woods, Reference Mattli and Woods2009, p. 16). They are selected on the basis that they seek to protect personal data (e.g., private communications, users’ personal preferences) against data misuse and surveillance practices. Policies specifically related to other internet issues (such as the accessibility for the disabled) are ignored. The list of the policies selected is provided in Table 1.Footnote 2

Table 1. List of internet privacy policies examined

The regulation of internet privacy and data protection has evidently been marked by important national and supranational laws, one of the most significant being the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GRPR). Events like the Edward Snowden revelations have furthermore been shown to contribute to the EU regulation's change by making data protection issues front‐page news (Bennett & Raab, Reference Bennett and Raab2020, p. 448) whilst creating a space for civil society to exert influence on decision making (Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019, p. 463). Focusing on legislative frameworks thus certainly provides valuable insights on politicisation. However, I focus on technical internet policies as they are largely regarded as apolitical, bringing only technical responses to technical challenges. The implication is that the internet privacy policies examined in the present paper represent a least‐likely case of politicisation. In other words, if focusing events do affect the scope of conflict over these technical policies, this will lend strong evidence supporting my argument. Furthermore, relatively little is known about the data protection and internet privacy rules determined by global internet regulatory agencies. ICANN, IEEE, IETF and W3C deal with the core architecture and infrastructure for internet communication. They consist of government representatives, engineers, civil society organisations, as well as large corporations, including Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and Google (Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020). There is no enforcement authority, and, therefore, the rules they develop are not binding by law. However, there is a huge market pressure to adhere to the rules as they allow different systems to operate together.

Data for this analysis is then derived from news articles. Media indeed represent an indispensable source which allows us to examine the different dimensions of politicisation (Grande & Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2016; Hoeglinger, Reference Hoeglinger2016). Data collection proceeded in two steps. First, I defined a time‐period starting 5 years before the policy's promulgation. Decision‐making processes within the internet regulatory agencies usually last between 3 and 5 years (Greenstein & Stango, Reference Greenstein and Stango2006). The time period ends 10 years after the policy's promulgation since this paper seeks to analyse the long‐term effects of focusing events on politicisation.Footnote 3 As some of the policies have been reviewed during 1990 and 2019, the time period for these policies ends 10 years after the promulgation of their most recent versions. Second, I collected articles covering each of the internet privacy policies selected for this study over the specified time period. I gathered articles from Factiva, an international database that collects contents from various sources of information, including major national newspapers like The Wall Street Journal (United States), The Financial Times (United Kingdom), Chosun Ilbo (South Korea), as well as more internet‐specialised newspapers, such as the Journal of Engineering.Footnote 4 Further examples of newspapers are found in the online Appendix (see Table A3) as well as the search terms used to collect the news articles (see Table A4).

Operationalisation of the variables

Politicisation

Building on existing studies (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Masini & Van Aelst, Reference Masini and Van Aelst2017), I operationalise Politicisation by focusing on three components: (1) issue salience, (2) actor expansion and (3) actor diversity. Politicisation is measured for each privacy policy during the defined time period (e.g., the Do‐Not‐Track standard in 2011, 2012, and so forth).

Issue salience

The salience of an issue can be assessed through its media coverage. Indeed, media sources only try to publish news articles that their consumers care reading about, and consequently use their services. For each internet privacy policy, I measure Salience as a percentage of all the articles published and recorded by Factiva.

It should be noted that Factiva records a vast number of media sources. Many of them are not relevant for the salience of a regulatory issue (e.g., the Dufa‐Index Handelsregister), potentially leading to an underestimated measure of salience. Alternatively, issue salience can be measured by counting the articles in different newspapers (e.g., Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2010, p. 162) or by taking the percentage of all the articles published by a sample of newspapers (Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013, p. 126). Although these methods are a valid measure of attention, I adopt a slightly different approach as my purpose is to measure the worldwide media coverage of technical internet policies over a long period of time. The raw number of articles does not give a meaningful number as more articles are published today than 20 years ago. Relying only on a few general newspapers limits the amount of data collected and the scope of the analysis.

Salience is highly skewed as some policies have not always received media coverage. After cleaning data from irrelevant articles, I chose to remove duplicates to get a conservative measure of salience.Footnote 5 Although duplicates can be an indicator of public attention, I argue that removing them is needed to ensure a valid and reliable measure of the second dimension of politicisation, that is, actor expansion. Salience ranges from 0 to 0.26.

Actor expansion

Actor expansion refers to the extent to which debates include a growing number of actors. For each internet privacy policy, I extract the actors mentioned in the news articles collected and measure Actor expansion as the total number of actors.Footnote 6Actor expansion ranges from 0 to 36. Such a measure is meaningful insofar as a limited number of actors does not suggest a high level of political conflict. However, a large number does not necessarily mean that the actors involved in debates represent diverse interests and opinions.

Actor diversity

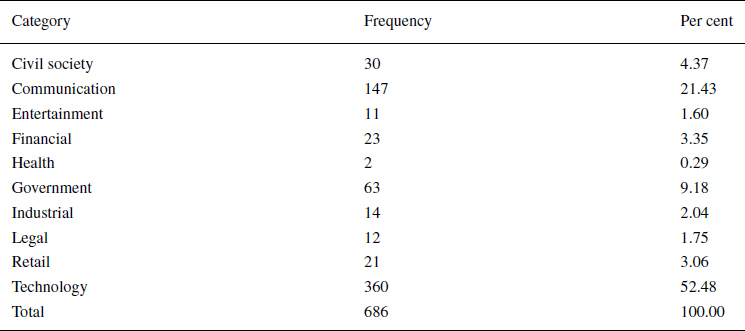

The third dimension of politicisation is, therefore, actor diversity. Actor diversity describes the degree to which various types of actors are engaged in debates. Measuring actor diversity required several steps. First, I hand‐code the actors mentioned in the news articles by their primary industrial activity according to the Dow Jones Industry taxonomy. This results in the identification of 10 actor types: technology (hardware and software applications); communication (social media platforms, telecommunication services, media); industry (production of electrical equipment, defence and aerospace); finance (financial services activities, insurance, banking); legal (legal service); retail (retail trade, including e‐retail); health (human health activities); entertainment (video and television programme production); government (national and international governmental organisations); and civil society (representing advocacy groups, scientists affiliated with universities and other knowledge institutions). The regulatory agencies were also mentioned in the news articles. However, I chose to exclude them in the measure of actor diversity as they are the venues which develop the internet privacy policies that are debated.

Second, I measure Actor diversity for each internet privacy policy using a Herfindahl–Hirschmann index, which is a well‐established method for this purpose (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2015; Rasmussen & Carroll, Reference Rasmussen and Carroll2014). It is measured as the sum of the squared proportions of actors belonging to each of the actor types considered and mentioned in the collected news articles. The index ranges from 0 to 1, initially with values closer to 0 indicating greater actor diversity. As greater diversity is an indicator of greater politicisation, I reverse the scale; hence values close to 1 indicate greater diversity in my measure of actor diversity. The overall distribution of the actors is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Distribution of actors for all internet privacy policies

It is worth emphasising that actor diversity does not necessarily imply different policy positions as diverse actors can hold similar preferences. Nevertheless, if more diverse interests are engaged in debates, it is more likely to see competing positions in debates. The notion of actor diversity thus captures the potential for contestation (Masini & Van Aelst, Reference Masini and Van Aelst2017). Furthermore, it points out that the issue is not only debated among a specialised community of actors with concentrated, vested interests.

Politicisation index

I construct a Politicisation index by standardising and combining the three components into an additive index. An alternative approach would involve giving greater weight to issue salience (Grande & Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2014; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). However, I suggest that politicisation is both a matter of salience and political mobilisation (i.e., expansion and diversity), and high politicisation can be associated with low salience (Rauh, Reference Rauh2019). I compute Cronbach's alpha for all three components to measure internal consistency. The alpha coefficient is 0.73, suggesting a relatively high internal consistency. Such an index seems to be, therefore, validated.

Focusing events

Building on Marsch and Mikhaylov's analysis of the Irish election (Reference Marsch and Mikhaylov2012), three variables are included in the analysis to test the impact of focusing events. The first variable, F ocusing event, is a dichotomous variable that equals 0 in the years preceding a focusing event and 1 in the following years. The year in which a focusing event takes place also equals 1. To avoid overlaps, the period following the September 11 ends in 2007, and the period following the Edward Snowden revelations ends in 2017. The post‐Facebook Cambridge–Analytica scandal period ends in 2019, that is, the last year in which data are collected. As the attention and participation raised by a focusing event are expected to lessen (Birkland, Reference Birkland1997; Downs, Reference Downs1972), a second variable is included as a control variable. Indeed, Downs argues that an increase in attentiveness and participation tends to falter as ‘more and more people realise how difficult, and how costly to themselves, a solution to the problem would be’ (Reference Downs1972, p. 40). Birkland also notes that the process through which individuals seek to apply new information and propose new ideas to handle a problem also decays over time (1997, pp. 17–21). He argues that policy alternatives and preferences will become fewer, but this decline in interest and mobilisation can still be reversed if a new focusing event happens. The second variable, After the event, is a count of the number of years since a focusing event occurred. It equals 1 in the year of a focusing event, 2 in the year after the event, and so forth. It equals 0 in the 5 years preceding a focusing event. Finally, I include a variable, time, to control for time trends. This variable equals 1 in the first year of the sample, 2 in the second, and so forth.

Alternative explanations and additional control variables

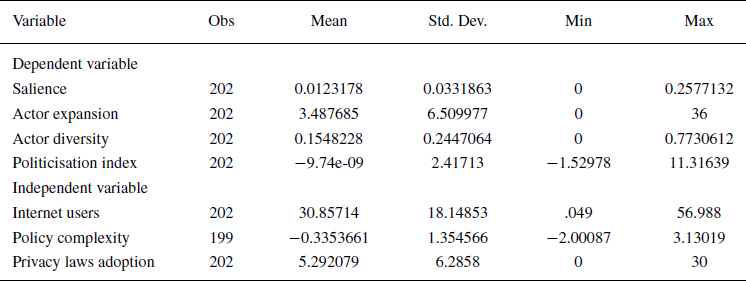

As it may be inaccurate to attribute a political outcome to any one cause, other variables are included in the analysis, thereby providing a sense of the relative explanatory power of focusing events. Summary statistics of the variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary statistics

One potential explanation for the politicisation of internet privacy regulation may lie in the increase of the internet's users worldwide (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Fenton and Freedman2012). Indeed, the more individuals using the internet, the more data protection and internet privacy rules should become a subject of intense public discussions. I thus include the percentage of the world population using the internet for each year between 1990 and 2019. Data for this variable are retrieved from the World Bank indicator.Footnote 7

Another important trend that needs to be accounted for is the adoption of national and supranational data protection laws around the world. Legislative changes may indeed impact the incentives of certain actors to become active in debates over global and technical internet privacy rules, expanding the scope of conflict. I thus include a variable that is a count of countries adopting data privacy laws for each year between 1990 and 2019. Data for this variable are retrieved and compiled from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.Footnote 8

At the policy level, politicisation may be affected by the type of policy established by the regulatory agencies, specifically the degree of policy complexity. Complexity refers to the degree to which an issue is difficult to understand and analyse (Klüver, Reference Klüver2011, p. 487). Less complex policies are more likely to be politicised as expertise is not required to discuss them, and thereby, more actors and diverse interests are able to enter public debates. I measure policy complexity relying on two indicators: the number of words and the type token ratios (TTRs) for each internet privacy policy. Regarding the number of words, the assumption is that the fewer words, the less complex the policy is (Klüver, Reference Klüver2011, p. 494). The TTR also allows to determine the linguistic complexity of a text by assessing how rich a text is in terms of words used. Consequently, the higher the TTR, the higher the lexical complexity is. I calculate the TTRs for each of the policies selected.Footnote 9 In order to combine the number of words and the TTRs in a single measure, I conduct a principal component factor analysis, and I use factor scores to assess policy complexity. Results of the principal component analysis can be found in the online Appendix (see Table A5).

Furthermore, the institutional context within which policies are decided can also affect the visibility of those policies and the type of actors involved in debates. Therefore, I control for the agencies’ year of creation.

Analysis

In this section, I first present descriptive results before testing the impact of focusing events on politicisation.

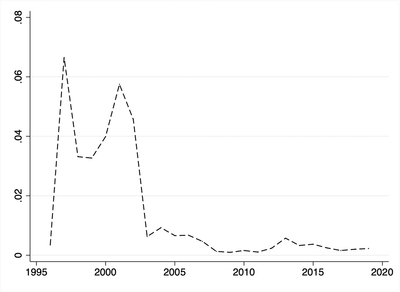

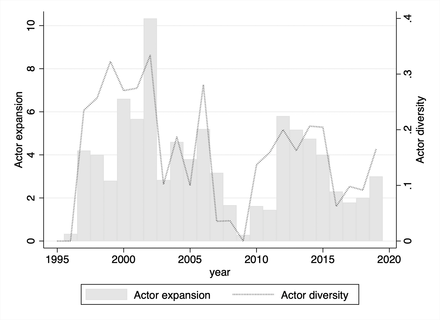

To begin with issue salience, Figure 2 shows that the policies developed by ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C, do not, overall, make the news. Specifically, articles covering each of the privacy policies represent, on average, less than 0.08 per cent of all articles published worldwide. This seems to contradict the findings of recent studies on internet privacy regulation (Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019; Rossi, Reference Rossi2016). However, these recent studies examine the salience of privacy issues related to consumer concerns in general and legislations like the EU GDPR. The internet privacy policies examined here are relatively technical; it may be that they can rarely lend themselves to common public interest, making it hard for them to attract media attention (Beyers &Kerremans, Reference Beyers and Kerremans2007). Still, ‘surge moments’ can be identified in 2001, and slightly in 2013. It should be noted that the policies’ salience is higher when it is primarily observed among specialised media sources, in particular in 2013. This is found in the online Appendix (see Figure A1). Figure 2 also shows a surge in 1997, but this could be explained by the fact that very few media sources are recorded by Factiva from 1990 to 1999, making the percentage of articles covering internet policies during this time period. Regarding the configuration of actors, data confirm that technology companies, in particular Microsoft and Cisco Systems, tend to dominate debates largely. This is no surprise given the central role played by technology companies in implementing the privacy rules in computer settings and programs. When technology companies are joined by companies operating in communication services, like Alphabet (i.e., the parent company of Google), they represent together between 75 per cent and 95 per cent of the actors involved in debates. However, this dominance tends to decrease as the range of actors engaged and the interests represented in debates increase during the last decade, as shown in Figure 3. Specifically, state actors (the EU in particular) seem to engage increasingly in debates over the internet about the privacy rules established by technical bodies. Additionally, new actors appear to express their views, such as civil society organisations (e.g., Privacy International, Consumer Watchdog), and companies which do not directly operate in the design and installation of computer hardware components (e.g., eBay, Amazon, Atari). This suggests that the global internet privacy rules are not only in the interest of technology actors but also they have far‐reaching implications for a broader range of actors as well as the economic sectors, leading thereby to potential intra‐business conflicts.

Figure 2. Salience (mean) by year.

Figure 3. Actor expansion and actor diversity (mean) by year.

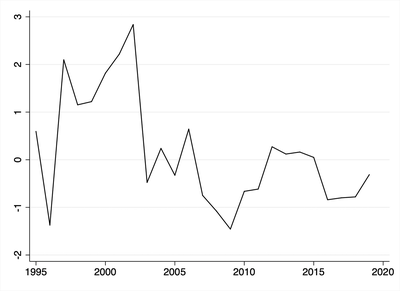

Consistent with these findings, distinctive ‘politicising moments’ can be identified in Figure 4. There is a lack of a benchmark establishing where the threshold of ‘highly politicised’ stands, but a series of events seems to reveal a pattern in the politicisation of internet privacy regulation. Table A6 in the online Appendix provides details on the values of the politicisation index after each focusing event.

Figure 4. Politicisation index (mean) by year.

I then test the effect of focusing events on politicisation. The online Appendix contains additional robustness analyses in which I use a different measure of politicisation (see Table A7) as well as different post‐event periods (see Table A8). It should be kept in mind that issue salience, actor expansion and actor diversity can be mutually reinforced. As salience increases, the number and diversity of actors in conflict increase as well. At the same time, the increase in the range of actors can also increase the visibility of the issue at stake. However, this paper has aimed at testing the direct effect of focusing events on politicisation.

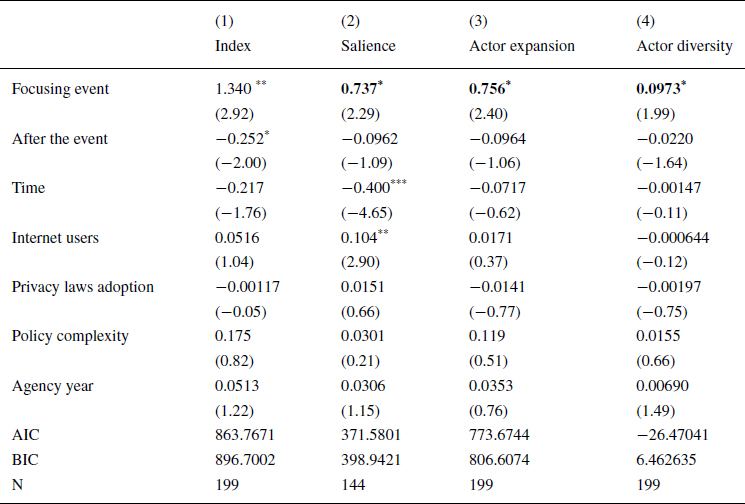

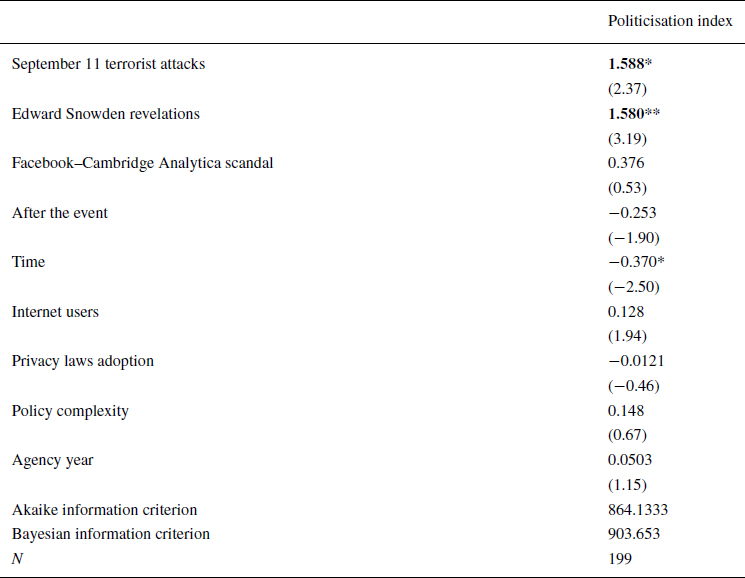

Table 4 presents the results of the multilevel analysis. The rationale for using multilevel modelling is to consider the hierarchical structure of the data, that is, politicisation (level 1) is nested within policies (level 2). Ignoring the clustering of the data may indeed result in deflated standard errors. I thus use a mixed model with random intercepts at the policy level. Because policies are nested within agencies (level 3), I could have added a higher level, but this appeared to be insignificant. I test the effect of focusing events on politicisation (model 1) and its components, that is, issue salience (model 2), actor expansion (model 3) and actor diversity (model 4). Because the dependent variables are continuous in models 1, 2 and 4, I estimate models using multilevel linear regression. Data for issue salience are log‐transformed to normalise the distribution. In model 3, I estimate a model using multilevel negative binomial regression since actor expansion is a count variable.

Table 4. Impact of focusing events on politicisation

Note: t statistics are in parentheses

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.0,

*** p < 0.001.

The results indicate that the presence of a focusing event has a statistically significant and positive effect on the politicisation index with a p‐value of <0.01. More precisely, they suggest that when a focusing event occurs, the mean of the politicisation index is increased by 1.3. The regression results, furthermore, indicate that the presence of a focusing event significantly increases each component of politicisation. The effect is particularly large on actor expansion. However, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), which assess the relative fit of the models, indicate a better fit with model 2 (i.e., Issue salience) and even more so with model 4 (i.e., Actor diversity). Models with smaller AIC and BIC should be preferred over models with larger AIC and BIC (Gelman & Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2006). After the event also shows a statistically significant effect on the Politicisation index with a p‐value of <0.05. The effect is negative, indicating that the more years that pass since a focusing event, the less politicised the privacy rules become, as expected. However, this variable does not reach statistical significance in models 2–4. The additional control variables do not show a statistically significant effect on politicisation, except for time and internet users in model 2. It is rather surprising that the impact of privacy laws adoption is not statistically significant (and negative on actor expansion and actor diversity). One would expect many countries’ adoption of privacy laws as well as the enactment of key regulations like the GDPR to bring data protection and internet privacy issues into the public eye, expanding the scope of conflict beyond the legislative arena. As it may take some time for privacy laws to affect politicisation in technical venues, an additional model with lagged values is provided in the online Appendix (see Table A9). However, the variable still does not reach statistical significance. This result suggests that technical and specialised policy areas tend to remain relatively isolated from the legislative arena, which may limit democratic participation and deliberation.

Focusing events, however, seem to contribute to politicisation. Evidence from the news articles collected can shed some further light on the impact of focusing events on the scope of conflict within ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C. Security and privacy increasingly appeared as ‘major issues’ in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks (Tedeschi, Reference Tedeschi2002) and Edward Snowden revelations (Cookson, Reference Cookson2013; Tummarello, Reference Tummarello2013). Specifically, the debates were structured around the question of the level of privacy required in the face of security issues, with state actors primarily arguing that internet privacy can and should be limited for security reasons. In this context, and to prevent state interferences, the development of internet privacy standards was particularly welcome by civil society and companies operating in various sectors (Musthaler, Reference Musthaler2001). But the revelations in 2013 that intelligence agencies (particularly the US National Security Agency and the UK Government Communications Headquarters) had compromised protocol security to access personal information added new lines of conflict. Technology and communication companies strongly increased their support for privacy standards that limit government interferences (Cookson, Reference Cookson2013). Civil society organisations increasingly engaged in debates over internet privacy regulation and appeared to stand with technology and communication companies against governments’ ‘snooping programmes’ (Cookson, Reference Cookson2013, para. 1). Claiming that ‘the hacking programs being undertaken by GCHQ are the modern equivalent of the government entering your house’ (Claburn, Reference Claburn2014, para. 3), they promoted the development of internet standards that make communications more secure (Appelbaum et al., Reference Appelbaum, Gibson, Grothoff, Müller‐Maguhn, Poitras, Sontheimer and Stöcker2014). But the role of technology and communication companies in enabling state surveillance through their data collection practices was also largely denunciated by the public (Lee, Reference Lee2013; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2013). This critical stance can also be observed after 2018 and the revelations that personal information was illegally used for political purposes. This focusing event primarily increased consumers’ concerns over the ‘convenience’ (Joseph, Reference Joseph2019, para. 17) of the services offered by communication platforms like Facebook, which ‘comes at a cost’ (Joseph, Reference Joseph2019, para. 18). This led privacy advocates, state actors and companies operating in various sectors to promote a more robust regulatory approach over data protection and internet privacy.

I now turn to the analysis of each event's impact on politicisation. Because the nature of the events varies (in particular the September 11 terrorist attacks compared to the Edward Snowden and Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandals) and because the events can entail variation in the substance of debates over privacy regulation, testing the impact of each event may reveal interesting findings. Again, I perform an additional multilevel regression analysis with the politicisation index as the dependent variable. Different from the previous model, each focusing event is included as an independent variable. Similar to the previous model, each event is operationalised as a dichotomous variable that equals 0 in the years preceding a focusing event and 1 in the following years. The same control variables are also included in the analysis. The regression results presented in Table 5 provide support regarding the impact of the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Edward Snowden revelations specifically. They suggest that each of these events has a significant effect on the politicisation index, with a p‐value of <0.05 for the former and <0.01 for the latter. The significance of the Edward Snowden revelations for the politicisation of internet privacy regulation within technical settings is consistent with existing research that highlights the event's political implications (Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020; Culpepper & Thelen, Reference Culpepper and Thelen2020; Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019). The Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal, however, does not reach statistical significance. One potential explanation for this result might be that fewer data are available to assess the effect of this recent event on politicisation.

Table 5. Impact of each focusing event on politicisation

Note: t statistics are in parentheses.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.0, ***p < 0.001.

Taken together, the descriptive and regression results suggest that, although the privacy policies established by seemingly technical bodies, remain, on average, an area of ‘quiet politics’ (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2010), focusing events contribute to expanding the scope of conflict, including actors beyond the internet expert community.

Conclusion

This paper examines the effect of focusing events on politicisation in technical arenas of global rule‐making. Taking global data protection and internet privacy rules established by ICANN, IETF, IEEE and W3C as my case, I used a systematic analysis of news media coverage worldwide over a 20‐year period, resulting in an ordinal dataset of 2,100 news articles. Before discussing the implications of the findings, I first underline two limitations. First, and perhaps most important, the present paper examines the media coverage of an issue on a global scale, but politicisation might then vary within national contexts due to structural factors or national political actors. Second, politicisation is examined using media coverage analysis, but political conflict can also occur under the radar of media coverage (Zürn, Reference Zürn2016, p. 168).

This paper has, nevertheless, important implications for research on politicisation. It extends the predominantly European governance‐centred literature on politicisation and provides empirical evidence supporting the impact of focusing events on politicisation in technical arenas. A central finding presented in this analysis is that focusing events extend the range of actors engaged in debates over seemingly technical policies. Building on this finding, future empirical research could examine how the process of politicisation affects the policies produced as well as the agencies that produce them. As EU studies have shown, politicisation is the necessary but not sufficient condition for political structuring, understood as the establishment of a permanent structure of political opposition between different actors (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016, p. 43). A complete picture of politicisation in technical arenas would also consider the role of government representatives and their positions in public debates. Building on my dataset, this could be assessed using a systematic analysis of the news articles’ content.

Finally, the paper has important implications for research on internet governance. Specifically, it points out the degree of attention accorded to global internet privacy rules determined by internet regulatory agencies as well as the configuration of actors engaged in such an issue, allowing to obtain a sense of the policy environment in which internet regulators operate at the global level. Despite their so‐called apolitical nature, the internet privacy policies determined by global public–private agencies are not self‐evident. They may reflect battles for the pre‐eminence of one solution over another rather than consensus over the best solution to a problem understood in a technical sense. They serve multiple functions (from the protection of human rights and national security to the development of markets) and focusing events, such as the global surveillance revelations made by Edward Snowden in 2013, expose political and economic tensions, leading to intense discussions and controversies. Given the internet agencies’ multi‐stakeholder model, where anyone wishing to participate can formally do so, the various interests expressing their concerns in public debates should also be involved in the decision‐making processes. Existing research on internet governance, however, suggests that corporate interests still dominate these decision‐making processes (e.g., Christou et al., Reference Christou, Harcourt and Simpson2020), questioning the agencies’ legitimacy and apparent responsiveness. More analysis that systemically explains and tests the conditions under which we are likely to see different levels of bias in the participation of substantive interests in internet governance is a fruitful way forward.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2020 ECPR General Conference. I would like to thank discussants and panel participants for their helpful suggestions as well as the editors and the anonymous reviewers.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. Details on the focusing events

Table A2. Media coverage of each focusing event

Table A3. Examples of media sources

Table A4. Details on the use of Factiva

Table A5. Principal‐component factor analysis (number of words and TTR)

Table A6. Details on the values of politicisation

Table A7. Robustness check 1 (multilevel analysis using a different measure of politicisation)

Table A8. Robustness check 2 (multilevel analysis using different time‐periods)

Table A9. Multilevel analysis with lagged Privacy laws adoption

Figure A1. Alternative measure of salience (mean)