Introduction

Imitation is ubiquitous in humans. It has been argued to be a fundamentally important capacity for human culture (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello1999) and a developmental basis for language and cognitive skills (Barr & Hayne, Reference Barr and Hayne2000; Carpenter, Nagell & Tomasello, Reference Carpenter, Nagell and Tomasello1998; Charman, Baron-Cohen, Swettenham, Baird, Cox & Drew, Reference Charman, Baron-Cohen, Swettenham, Baird, Cox and Drew2000), representing a powerful learning mechanism for human beings, whether infants or adults. The present study expands on previous research on imitative abilities and investigates the role played by different types of imitation skills (language-based multimodal imitation vs. object-based imitation) that have thus far rarely been assessed together. It also contributes to the literature on the imitation abilities of young preschoolers, an age group in whom important linguistic and social developmental advances take place and which has hitherto not been actively studied in the field of imitation abilities. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the relationship between different types of imitation is investigated in relation to linguistic and pragmatic skills in preschool children.

We will start by briefly reviewing the previous literature on the relationship between imitative behaviors and language and sociopragmatic abilities, making the case that language-based imitation should be assessed from a socially relevant multimodal perspective. Imitation skills, understood as the ability to intentionally replicate others’ behaviors or actions, play a fundamental role in the development of language and how it is used in social contexts (i.e., social communication). Numerous empirical and longitudinal studies have shown that spontaneous imitative behaviors which naturally occur in language interactions during the first and second year of life (specifically between 9 and 24 months), as well as elicited imitation behaviors, are key for language production and comprehension (Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni & Volterra, Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979; see Hanika & Boyer, Reference Hanika and Boyer2019 for a review), the acquisition of vocabulary (e.g., Bates et al., Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Nagell and Tomasello1998; Masur & Eichorst, Reference Masur and Eichorst2002; Snow, Reference Snow, Speidel and Nelson1989), and social communication behaviors such as interactive actions like requesting or greeting (e.g., Dohmen, Bishop, Chiat & Roy, Reference Dohmen, Bishop, Chiat and Roy2016; Heimann, Strid, Smith, Tjus, Ulvund & Meltzoff, Reference Heimann, Strid, Smith, Tjus, Ulvund and Meltzoff2006). In relation to language production and comprehension skills, Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979) performed a correlational study with 9- to 13-month-old infants and reported a strong link between vocal imitation (i.e., imitation of sounds and words) and language production and comprehension at this stage of development. Hanika and Boyer (Reference Hanika and Boyer2019) demonstrated that motor imitation behaviors (like clapping hands or pushing a toy car across a table) in infants between 15 and 18 months have a unique relationship to language comprehension skills. In relation to the acquisition of vocabulary, in a study with children from 9 through 15 months, Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Nagell and Tomasello1998) observed a positive relationship between the age when infants began to imitate arbitrary actions involving physical objects (e.g., hitting the side of a box or patting the top of a box with one hand) and the age when they began to use referential language (i.e., words used to refer to specific actions or objects). Masur and Eichorst (Reference Masur and Eichorst2002) showed that infants that imitated more novel words at 13 months had larger lexicons at 17 months and 21 months, demonstrating that a higher frequency in the imitation of novel words at 13 months predicted infants’ later lexical development. Snow (Reference Snow, Speidel and Nelson1989) concluded that vocal and gestural imitation abilities at 14 months were significantly correlated with language skills (i.e., the number of verbs produced or total productive vocabulary) at 20 months. As for the relationship with sociopragmatic skills, Dohmen et al. (Reference Dohmen, Bishop, Chiat and Roy2016) carried out a longitudinal study with 29 2-year-old German-speaking children identified as late talkers, who were followed up at 4 years of age. The results showed that while early language skills at 2 years were significantly associated with later language outcomes, imitative behaviors made a significant contribution to the prediction of the social communication outcome two years later. Clinically, Dohmen et al.’s study demonstrated that body movement imitation measures have the potential to improve the identification of preschoolers who are at risk of later social communication and language problems. Focusing on non-typically developing populations, the study by Wray, Saunders, McGuire, Cousins and Norbury (Reference Wray, Saunders, McGuire, Cousins and Norbury2017) revealed that children with language impairment (LI) showed weaknesses in gesture accuracy imitation patterns (i.e., imitation skills in a gesture elicitation task) in comparison to typically developing peers. Additionally, the ability to imitate both words and simple syntactic structures has been shown to be associated with language development in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010).

Importantly, the spontaneous or elicited imitative behaviors analyzed in the above-mentioned developmental studies encompass both language-based imitation, which includes several language components (e.g., speech vocalizations, body actions, facial expressions, and vocabulary), and object-based imitation (e.g., imitative patterns involving actions on objects observed through play-based activities comprising free-play, book sharing, constructive play, or symbolic play). To our knowledge, only a handful of studies have explicitly compared the relevance of language-based and object-based imitation skills, suggesting that the former have stronger links to language abilities than object-based imitation skills (see Stone, Ousley & Littleford, Reference Stone, Ousley and Littleford1997; Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010; Masur & Ritz, Reference Masur and Ritz1984; Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse & Wehner, Reference Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse and Wehner2003). Stone, Ousley and Littleford’s (Reference Stone, Ousley and Littleford1997) study suggested that the imitation of socially relevant body movements and the imitation of actions with objects represented independent dimensions which are not equally related to patterns of language use and language development. In their results, while the imitation of body movements was concurrently and predictively associated with expressive language skills, the imitation of actions on objects was associated with play skills. Masur and Ritz (Reference Masur and Ritz1984) found that 10- to 16-month-old infants more accurately imitated communicative gestures such as waving or pointing than hand and arm movements with no communicative significance, such as opening and closing of the fist or raising an arm. A similar pattern was reported by Rogers et al. (Reference Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse and Wehner2003) with regard to facial imitation (e.g., extending the tongue and wiggling it to both sides or making a noisy kiss), with more imitations of facial expressions which were strongly linked to interpersonal social engagement. These findings support the idea that the social function of gestures might be strongly modulating infants’ imitation patterns in a more significant fashion than non-social imitation behaviors. Finally, Ingersoll and Lalonde (Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010) analyzed the beneficial role of gesture imitation tasks over object-based imitation tasks in language therapy settings with older children with ASD and found that gesture imitation tasks had a stronger impact.

Despite the important contributions made by the abovementioned studies, it is noteworthy that none of them incorporated an integrative multimodal view of language-based imitation which includes the gestural, prosodic, and verbal/lexical components. The present study aims to fill in this gap by analyzing the relationship between multimodal language-based imitation (understood as the integration between gestural, prosodic, and verbal/lexical content dimensions) and object-based imitation in a later stage of development (namely, the early preschool years). Although imitative learning behaviors tend to dwindle spontaneously from about 2 years of age, as the child moves into the preschooler stage, imitation continues to be a key component of social communication that promotes shared experiences and social play (Nielsen & Blank, Reference Nielsen and Blank2011). It is thus relevant to ask whether young preschoolers’ abilities to accurately perform the multimodal imitation of socially relevant events are positively correlated with language and sociopragmatic skills. We believe that this is an important developmental period to focus on, because it is when children are delving right into the complex areas of language. When they enter school, they are expected to have certain school readiness skills such as sociopragmatic abilities and basic narration skills, and these skills have been demonstrated to be predictive of important aspects of language and academic development (e.g., Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Nagell and Tomasello1998; Carpenter, Tomasello & Striano, Reference Carpenter, Tomasello and Striano2005; Dickinson & McCabe, Reference Dickinson, McCabe and Kavanagh1991; Dickinson & McCabe, Reference Dickinson and McCabe2001; Hedberg & Westby, Reference Hedberg and Westby1993; Paris & Paris, Reference Paris and Paris2003; Striano, Stahl & Cleveland, Reference Striano, Stahl and Cleveland2009). In this period, narrative and sociopragmatic skills are thus key in furthering our knowledge about the acquisition of the intersection between social cognition and language (see Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, Reference Norbury, Gemmell and Paul2014). Summarizing, as previous studies have focused on the relevance of imitation behaviors in early infancy and on children with language disorders, further research is still needed to fully understand the role of socially relevant imitation patterns at the preschool stage.

The main hypothesis underlying this investigation is that language-based imitation abilities (crucially regarded as the integration of three separate and complementary dimensions) will be related to both complex language measures (i.e., narration skills) and sociopragmatic measures in preschoolers. Several arguments support our proposal that it is crucial to investigate imitation from an integrated multimodal perspective. For a long time, language has been studied primarily as a unichannel phenomenon (i.e., only taking verbal cues into account), skirting over the fact that language is used, learned, and has evolved through face-to-face interactions (Enfield & Levinson, Reference Enfield and Levinson2006). However, numerous studies have provided evidence that speech and gesture are processed similarly in terms of semantic and temporal integration (e.g., Özyürek, Willems, Kita & Hagoort, Reference Özyürek, Willems, Kita and Hagoort2007; Peeters, Snijders, Hagoort & Özyürek, Reference Peeters, Snijders, Hagoort and Özyürek2017). Furthermore, there is evidence that prosodic information from visual and vocal channels is processed similarly by the brain (e.g., Biau, Morís-Fernández, Holle, Avila & Soto-Faraco, Reference Biau, Morís Fernández, Holle, Avila and Soto-Faraco2016), and developmental research shows that prosody and gesture develop together in an intricate relationship (see Esteve-Gibert & Guellaï, Reference Esteve-Gibert and Guellaï2018; Hübscher & Prieto, Reference Hübscher and Prieto2019, for a review). All in all, the parallel development of multimodal cues (prosody, gesture, and verbal content) and their fine alignment with speech demonstrate the need to assess the value of these multimodal cues together.

Moreover, the hypothesis that narrative and sociopragmatic abilities in preschool children are related to multimodal imitation abilities is supported by findings showing that gestures and prosody play a predictor and precursor role in children’s language development (e.g., Carvalho, Dautriche, Millotte & Christophe, Reference Carvalho, Dautriche, Millotte, Christophe, Prieto and Esteve-Gibert2018; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Iverson and Goldin-Meadow2005) and specifically also in children’s narrative development (Demir, Levine & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Demir, Levine and Goldin-Meadow2015; Stites & Özçaliskan, Reference Stites and Özçaliskan2017; Vilà-Giménez, Igualada & Prieto, Reference Vilà-Giménez, Igualada and Prieto2019; Vilà-Giménez & Prieto, Reference Vilà-Giménez and Prieto2018), as well as by findings showing that multimodal features of language precede and predict children’s sociopragmatic development (see Hübscher & Prieto, Reference Hübscher and Prieto2019 for a detailed review). All in all, given the important role played by prosodic and gesture patterns in language acquisition, we hypothesize that the ability to imitate socially-relevant multimodal cues (and their internal dimensions, i.e., prosody, gesture, and verbal content) must be linked to language and sociopragmatic skills.

The goal of the current study is thus twofold. First, it examines whether multimodal imitation abilities are related to narrative and sociopragmatic abilities in typically developing preschool children aged between 3 and 4. Though previous research has shown that different types of early imitation abilities, such as vocal or gestural imitation, are closely related to later language and sociopragmatic measures, it is unclear whether this relationship still holds in the preschool stage, a period of development where complex pragmatic and language abilities are still being acquired. In this study, two measures involving social and language skills will be used – namely, a sociopragmatic test and a narrative task. The sociopragmatic test applied here, the Audiovisual Pragmatic Test (APT, Pronina, Hübscher, Vilà-Giménez & Prieto, Reference Pronina, Hübscher, Vilà-Giménez and Prieto2019), focuses on children’s ability to use language in context and produce socially appropriate responses in a given interactional situation. In turn, narratives are widely recognized to be a solid and ecologically valid measure of preschool children’s language abilities (Demir, Fisher, Goldin-Meadow & Levine, Reference Demir, Fisher, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2014; Demir, Levine & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Demir, Levine and Goldin-Meadow2010; Demir et al., Reference Demir, Levine and Goldin-Meadow2015). In the narrative task, the child is asked to understand the main points of a simple story as well as its temporal and causal structure, and produce a coherent discourse. In this manner, both the sociopragmatic test and the narrative task assess real-world language use and social communication skills in children. Second, crucially, in order to assess the relevance of language imitation skills as opposed to object-oriented imitation, the present study will use a standard object-based imitation task which assesses children’s imitation of actions on objects. In this regard, we hypothesize that object-based imitation will have a weaker relationship with language measures such as sociopragmatic and narrative measures than language-based imitation, as has been observed in previous research.

Methodology

Participants

A total of 46 typically developing Catalan-speaking children (16 boys and 15 girls, M age = 46.48 months, SD = 3.4 months; range 41–52 months) attending one of two public schools in a middle-class neighborhood in Barcelona (Escola Antoni Brusi and Escola Bogatell) were initially enrolled in the experiment. Due to linguistic exclusion criteria and other methodological and technical issues, a total of 15 children had to be excluded (see below).

First, as the language to be used in the three experimental tasks was Catalan, an initial screening measure was carried out to ensure that all participating children had sufficient mastery of the language. Despite the fact that the main language of instruction in schools in Catalonia is Catalan, the degree of Catalan–Spanish bilingualism in the population of Barcelona is not uniform (according to municipal government statistics, in 2018 only 77.4% of inhabitants reported that they could speak Catalan, although 95.6% could understand it). Therefore, an individual language dominance measure was elicited for each child. This measure consisted of an expressive vocabulary test taken from the ELI (L’avaluació del llenguatge infantil), a standard test that measures the Catalan language skills of children aged 6 and under (Saborit Mallol, Julián Marzá & Navarro Lizandra, Reference Saborit Mallol, Julián Marzá and Navarro Lizandra2005). This expressive vocabulary test is a picture-naming task consisting of 30 pictures of common objects. For each correct naming, participants receive 1 point, with the maximum score being 30. The total score for each child is then normalized to a percentage scale. A score of 20% was set as the minimum required for inclusion in this study (M vocabulary score = 35.19, SD = 8.06, ranging from 20 to 53, calculated on 31 participants included in the study). Six children failed to achieve this minimum, thus reducing the number of participants in the experiment to 40. Further, data from nine children had to be excluded due to their lack of collaboration in the narrative task (N = 4), technical errors in the video-recording procedure (N = 2), or experimental errors due to the experimenter providing incorrect prompts during the multimodal imitation task (N = 3). Thus data from a total of 31 children were included in the study.

Materials

The materials for the study consisted of four tasks – namely, the Renfrew Bus Story Test, the Audiovisual Pragmatic Test, the Multimodal Imitation Task, and the Object-Based Imitation Task. Materials are available in the Open Science Framework repository (anonymized link, https://osf.io/jkmtd/?view_only=ca9467a16c9d4e37960c0c679ee57a5a). As mentioned above, the main purpose of conducting the four tasks was to assess the potential correlations among the four types of abilities in the preschool years.

Renfrew Bus Story Test

In order to assess narrative abilities, the Renfrew Bus Story Test (Renfrew, Reference Renfrew1997) was translated into Catalan. The Renfrew Bus Story Test is one of the most widely used standardized tests for eliciting story retelling in preschool and young school-aged children (Westerveld & Vidler, Reference Westerveld and Vidler2015). It has been shown to be a comprehensive way of measuring children’s narrative abilities, even at the preschool stage, when children are still not capable of retelling a story based on wordless cartoons, as it requires them to use their current semantic and syntactic abilities, as well as their knowledge of the typical structure of a story (Bishop & Edmundson, Reference Bishop and Edmundson1987; Westerveld & Vidler, Reference Westerveld and Vidler2015). The basic materials used for the Renfrew Bus Story Test as employed here comprised the story of the Renfrew bus in Catalan, ordered as a series of events, a set of color pictures illustrating each event, and a soft toy. The story itself centers around a bus that decides to escape from its owner in order to explore the world around it. Unfortunately, the bus does not know how to use its brakes so it ends up driving into a lake. When the driver finds the bus, he decides to help it. In the test procedure, first, the tester tells the story using the set of pictures to illustrate. The soft toy – hitherto out of sight – is then introduced, and the testee is asked to retell the story to the toy with the pictures now used as prompts.

Audiovisual Pragmatic Test

The Audiovisual Pragmatic Test (APT, Pronina et al., Reference Pronina, Hübscher, Vilà-Giménez and Prieto2019) was used to assess sociopragmatic abilities. The APT is based on various pragmatic tests which have been used in the past to assess pragmatic abilities in children, including the Test of Pragmatic Language (TOPL-2) (Phelps-Terasaki & Phelps-Gunn, Reference Phelps-Terasaki and Phelps-Gunn2007), the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–5 (CELF-5) instrument (Wiig, Semel & Secord, Reference Wiig, Semel and Secord2013), and the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language–2 (CASL–2) tool (Carrow-Woolfolk, Reference Carrow-Woolfolk2017). Additionally, the APT uses some specific contexts included in Discourse Completion Task (DCT) questionnaires that are intended to elicit prosodic patterns in adult speakers of Catalan (Prieto & Rigau, Reference Prieto, Rigau, Payrató and Cots2011). The APT has been successfully used in previous research with three- to four-year-old children to elicit pragmatically correct responses (Pronina et al., Reference Pronina, Hübscher, Vilà-Giménez and Prieto2019). In this test, participants are asked to respond as naturally as possible to spoken descriptions of everyday social contexts illustrated in pictures (see Figure 1). The social appropriateness of the child’s response in a given context was evaluated and given a score from 0 to 2 (see Coding for details on scoring and examples of children’s answers). The basic materials used for the Audiovisual Pragmatic Test include a set of 35 such descriptions with accompanying illustrations.

Figure 1. Example of an item from the APT

Note. Example of an item from the APT, which consists of the description in Catalan (English translation provided) of an everyday social context and the accompanying illustration. In this case, the item is intended to elicit a farewell.

Multimodal Imitation Task

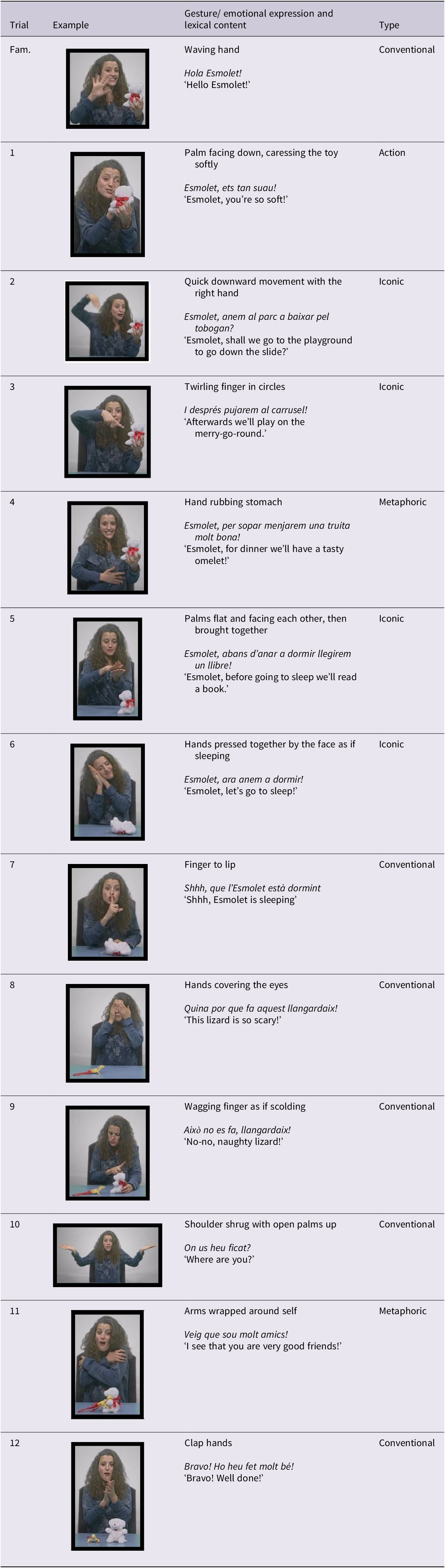

In order to assess the children’s ability to imitate pragmatic situations multimodally, a specific task for typically developing Catalan-speaking children was created by adapting some examples used in Ingersoll’s Reciprocal Imitation Training (RIT), which has been used in several studies to improve the social communication skills of children and teenagers with ASD (Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2008b, Reference Ingersoll2012; Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010). The RIT is a naturalistic behavioral intervention designed to teach spontaneous imitation to young children with ASD by means of play interactions with a partner. The basic materials for the Multimodal Imitation Task used here consisted of 12 items (see Table 1 below). They were created on the basis of examples coming from the RIT, as they combine different types of gestures with verbal labels, allowing us to simultaneously test gesture imitation, prosody imitation, and lexical imitation and thus gain a broader picture of children’s gesture imitation abilities. As the RIT was designed for children with ASD and the present study was carried out with typically developing children, the version used here included gestures with different levels of difficulty and verbal labels which were adjusted to the participants in this study. Before the experiment, all the gesture-verbal label pairs to be potentially included in the task were piloted with four 3- to 4-year-old children to test their difficulty and make sure that they were properly adapted to the children’s abilities. The selection of the items to be included in the task was made on the basis of how readily the children in the pilot test were able to perform the appropriate gestures and verbal labels.

Table 1. Set of items comprising the Multimodal Imitation Task

Note. Familiarization example and 12 video-recorded prompts included in the Multimodal Imitation Task, temporally organized as a sequence of conversational prompts.

The 12 target items plus a familiarization item were designed to be used as prompts in the Multimodal Imitation Task, and they were grouped temporally so that they would form a sequence of conversational messages directed either at a teddy bear called Esmolet or at the camera. The 12 utterances consisted of exclamatives (expressing affective meanings and greetings), questions (yes-no and wh-questions) or imperatives, mostly either directed at or referring to the bear, and each accompanied by the appropriate intonation and gestures. The 12 items can be seen in Table 1. Gestures were classified into conventional, iconic, or metaphoric gestures (see Cartmill, Demir & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Cartmill, Demir, Goldin-Meadow and Hoff2012). After the familiarization item an action was also included as the first target item, in order to initiate the story.

A small teddy bear and a toy lizard were used for the Multimodal Imitation Task (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Objects used for the Multimodal Imitation Task

Note. Teddy bear and toy lizard used for the Multimodal Imitation Task.

A Catalan-speaking female actor was video-recorded with a professional camera in a recording studio at Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona as she reproduced the 12 items following the instructions given by the first author of the study. In the video each item was separated from the next by a 7-second pause so that the children would be able to imitate one item at a time.

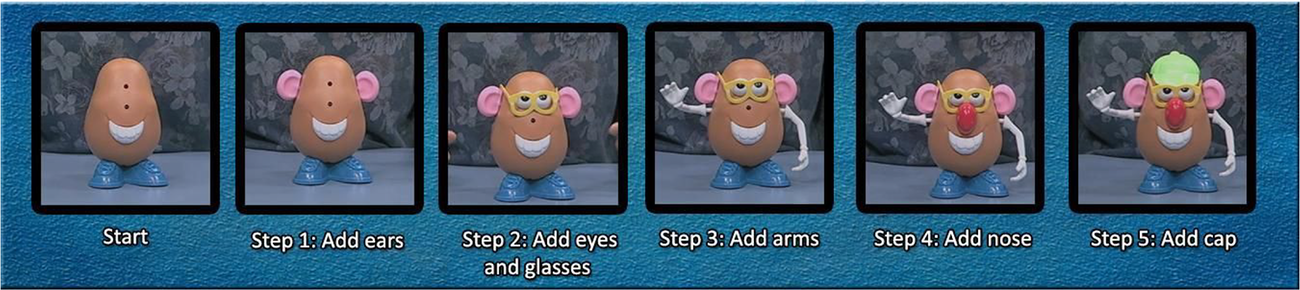

Object-Based Imitation Task

The design of the Object-Based Imitation Task was based on the animal task used in Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016). The task stimulus consisted of a particular sequence of five actions (Action 1 followed by Action 2, followed by Action 3, and so on) to be performed on a Mr. Potato Head®, using its body and parts (ears, eyes with glasses, arms, nose, and cap), and which the children being tested were asked to imitate. The toy shoes and toy mouth were already attached to the potato-shaped body.

It is important to note that there are two important differences between the original task as applied in Subiaul et al. (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016) and the task created for this study, which were mainly motivated by the fact that in this study the younger children were 3;6 years of age, whereas the younger children in Subiaul et al. (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016) were 2;6 years of age. First, whereas in Subiaul et al. (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016) a rabbit and a monkey mounted on a wooden base were used, a Mr. Potato Head® – a more complex toy – was used here. Second, whereas Subiaul et al.’s (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016) task consists of a three-action sequence, our version of the task consisted of a somewhat more demanding five-action sequence in order to adapt the difficulty of the task to the age of the participants.

A video demonstration of the sequence was recorded. In the video, a Catalan-speaking female actor (with only the hands showing) assembled the Mr. Potato Head® three times.

Procedure

The children were assessed individually by the first author of the present study and one additional research assistant. The four tasks were carried out in a quiet room at the participating schools and all the sessions were videotaped. In the room there was a table and two chairs, one for the participant and one for the experimenter (see Figure 4). On the table there was a tablet computer, where the color illustrations for the Renfrew Bus Story Test and the APT were shown, as well as the video for the Multimodal Imitation Task and Object-Based Imitation Task. The experimenter kept the set of toys needed for the tests hidden in a bag until they were needed (see Materials section). Regarding the order of presentation, the narrative task (Renfrew Bus Story Test) was administered first, followed by the sociopragmatic task (Audiovisual Pragmatic Test), the Multimodal Imitation Task, and the Object-Based Imitation Task.

Renfrew Bus Story Test

Each child was first asked to listen to the experimenter’s lively narration of the Renfrew Bus Story while looking at a sequence of color illustrations corresponding to the situations happening in the story (the tablet computer was simultaneously operated by the experimenter). After the experimenter explained the story and the children listened to it, the experimenter took the soft toy out of the bag and asked the child to retell it to the soft toy, using the same illustrations on the computer as a prompt. If the children did not mention all of the actions occurring in the story, the experimenter asked them if they wanted to add anything else. The experimenter stopped the task when the children informed the experimenter that they had finished, or when the children did not say anything within 10–15 seconds after the experimenter had asked them whether they wanted to add anything else.

Audiovisual Pragmatic Test

Using a lively and child-directed style, the experimenter described one by one a set of 35 items related to a social situation while the children looked at the corresponding illustrations on the screen. Two familiarization trials were introduced before the actual test started. After each item was presented, the experimenter asked the children to respond as if they were involved in the situation. Because in this type of test it is very important that the participant feels comfortable, on the occasions where a child experienced difficulties or needed further context to understand the situation, the experimenter would resort to using the names of people familiar to the child, such as a friend, parent, or teacher. If the child showed restlessness or explicitly asked to stop the task, the test was discontinued.

Multimodal Imitation Task

The Multimodal Imitation Task involved first watching a brief video with instructions and an introduction to Esmolet the teddy bear, which was given to the child right before the first familiarization trial. The video playback was then paused while the experimenter repeated the instructions in person, and this was followed by a familiarization trial to make sure the child understood that they were supposed to imitate what they saw modeled in each video clip. The imitation task proper then began. The child was asked to view a continuous sequence of 12 videos as described above, each video separated from the next by a 7-second pause. After the child watched two repetitions of each trial, the experimenter first imitated the gestures, intonation, and lexical content as in the video and then encouraged the child to do the same, saying Ara tu! ‘Now it’s your turn!’. Then the child proceeded to imitate the behaviors performed by the experimenter, which had previously been depicted in the video clip, using Esmolet the bear and the toy lizard him/herself as appropriate (see Table 1 in the Materials section). After piloting the materials with four children, it was decided to have the adult first model what was to be imitated in this manner because, as has been noted previously by several authors (e.g., Dickerson, Gerhardstein, Zack & Barr, Reference Dickerson, Gerhardstein, Zack and Barr2013; Flynn & Whiten, Reference Flynn and Whiten2008), children perform poorer on gestural imitation tasks when actions are presented only in video format, a phenomenon that can be explained by the lack of social contingency inherent in a video.

Object-Based Imitation Task

The Object-Based Imitation Task involved first giving the instructions for the task and introducing the Mr. Potato Head®, and then watching a video with three demonstrations of the sequence of actions to be performed (see Figure 3). After the first demonstration, the video was paused and the experimenter repeated the instructions to make sure that the children understood that they were supposed to imitate what they saw modeled in the video and that they had to repeat the actions in the same order. The video was paused again before the third and last demonstration while the experimenter reminded the children that this would be the last demonstration before they had to imitate the pattern. Verbal cues such as Mira això! ‘Look at this!’, Oi que és divertit? ‘Isn’t this fun?’ and Una última vegada! ‘One last time!’ were used in the video before each demonstration and also before each action in the sequence to capture the attention of the children. After the children watched the three demonstrations, the experimenter handed the torso and other body parts of Mr. Potato Head® to the children and encouraged them to imitate the sequence shown in the video by saying Ara et toca a tu! ‘Now it’s your turn!’

Figure 3. Five-action sequence used in the Object-Based Imitation Task

Note. Five-action sequence to be performed by children on the Mr. Potato Head®.

Figure 4. Stills taken from video-recordings of the experimenter and children carrying out the tasks

Note. In the top left panel, the experimenter and a child carrying out the Renfrew Bus Story Test. In the top right panel, the experimenter and a child carrying out the Audiovisual Pragmatic Test. In the bottom left panel, the experimenter and a child carrying out the Multimodal Imitation Task. In the bottom right panel, the experimenter and a child carrying out the Object-Based Imitation Task.

Coding

The performance of the remaining 31 children in the Renfrew Bus Story Test, the APT, the Multimodal Imitation Task and the Object-Based Imitation Task was coded by the first author of this paper and one research assistant.

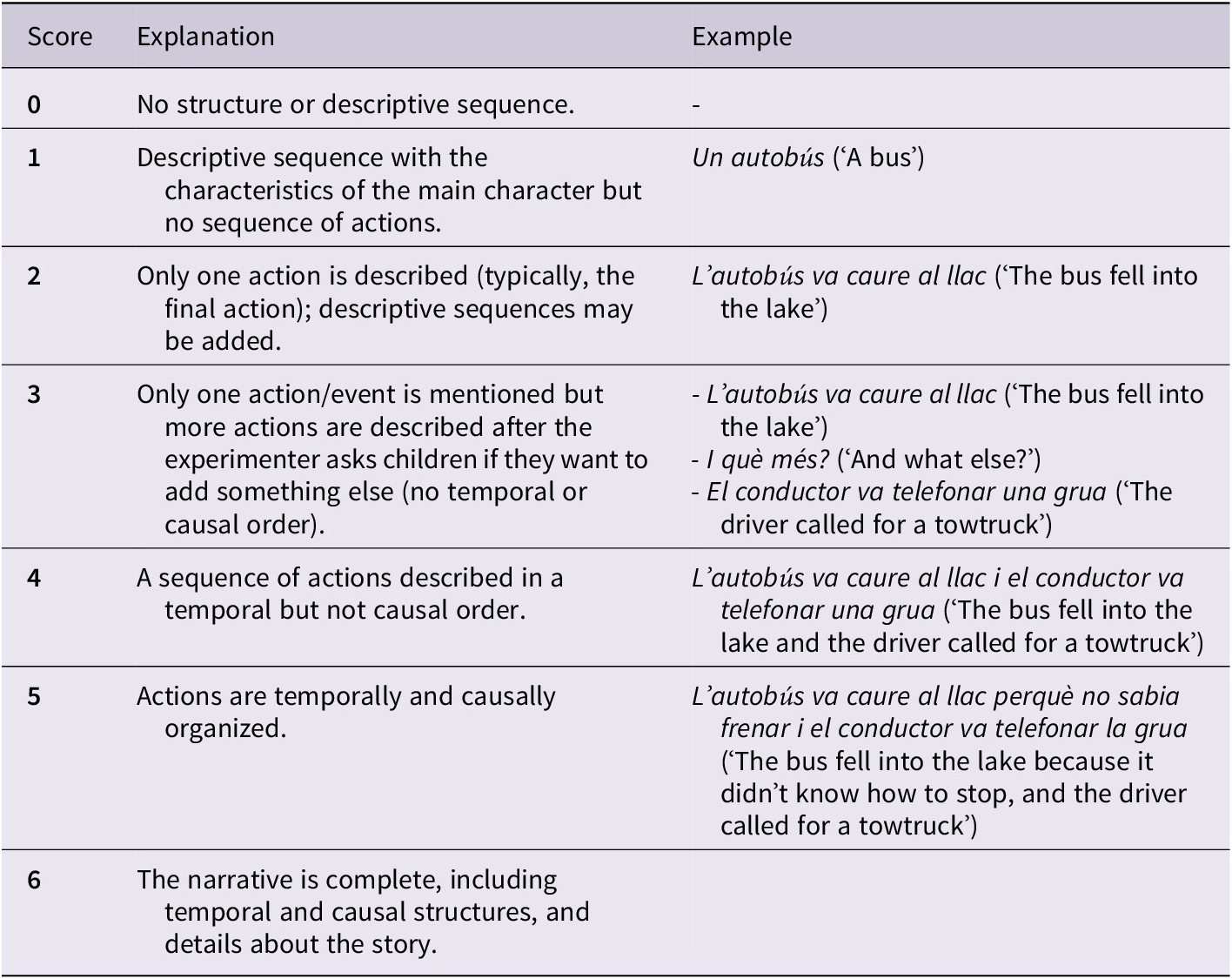

Renfrew Bus Story Test

Following previous studies on the assessment of narrative abilities (Demir et al., Reference Demir, Fisher, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2014; Vilà-Giménez et al., Reference Vilà-Giménez, Igualada and Prieto2019), the children’s narrative abilities were assessed in terms of narrative structure scores. Narrative structure was coded using an adaptation of the coding system employed by Vilà-Giménez et al. (Reference Vilà-Giménez, Igualada and Prieto2019). A score ranging from 0 to 6 was given to each child (see Table 2 below).

Table 2. Scoring system for narrative structure

Note. Scoring system used for coding narrative structure.

Audiovisual Pragmatic Test

Sociopragmatic abilities were assessed in terms of the pragmatic appropriateness of responses. Each response in the APT was given a pragmatic score ranging from 0 to 2. The score was based on the evaluator’s perception of the social appropriateness of the child’s response. A high-quality pragmatic response was rated as 2, meaning that the child was able to react to a given scenario in a socially appropriate way and show social involvement. For example, if in a scenario where the child was prompted to ask a family member for a piece of cake, the child said something like Can I have a piece?, the answer was given a score of 2. If in a scenario where the child was prompted to refuse a piece of cake, they said something like No, thank you, I don’t want any or Thank you for asking but I’m too full, the answer was given a score of 2. A score of 1 was recorded if the child gave a socially acceptable but not ideal answer. Depending on the scenario, this might mean that the child’s answer was too direct, or that the child said too little or too much. For instance, in the context of asking for a piece of cake, if the child uttered a sentence like Give me or I want some, the answer was given a score of 1 since the child had managed to express a requesting speech act but in a rather imperative manner without any mitigating device, which was not entirely appropriate. By the same token, if in refusing the piece of cake, the child simply said No, the answer was also given a score of 1 since the child had managed to express refusal but showed a lack of social adjustment. Finally, a score of 0 was recorded if the child either did not give any response, gave an unrelated response, or gave a response that was pragmatically inappropriate (that is, socially unacceptable). For example, if in refusing the piece of cake, the child said I want more cake, the answer was scored as 0 since the child had clearly not understood the situation. Similarly, if in response to the item where the child was prompted to express concern for a friend who had just tripped and fallen down, the child simply said You fell in a blunt way, with no expression of concern, this answer was scored 0. Highly appropriate answers to this item like Are you OK? or Do you need help? were coded as 2. The score obtained for each of the items was added up to produce an overall pragmatic appropriateness score for each of the participants. The maximum score possible was 70 (35 items × 2 points per item).

Multimodal Imitation Task

As noted, in this task the child was encouraged to imitate everything the actor did, including gesture, prosody, and lexical content. Since it was conceivable that the child would fail to reproduce one or more of these elements, these three components were evaluated separately. Thus, for each of the 12 videos, a separate score from 0–2 was given for gesture, prosody, and lexical imitation, yielding a possible maximum of 6 points per video. A score of 0 points was given if the child either did not imitate the component altogether or did something completely at variance from the model. A score of 1 was given if the child reproduced the modeled gesture, prosody, or lexical content only partially. For gesture or prosody, this meant that the gesture or prosodic pattern produced by the child was similar but not identical to the model. In the case of lexical content, this meant that the child produced only part of the target utterance. Finally, a score of 2 points was given when the child accurately reproduced the gesture, prosodic pattern, or lexical content exactly as displayed in the video. In order to assess how similar children’s gestures were to the model input, the experimenter took into account not only the position of the hands (i.e., if the children’s hands were placed in the same position as the experimenter’s hand) and their form (i.e., if the shape of the children’s hands was the same as the experimenter’s), but also hand movements (i.e., if children were performing the same movements as the experimenter). As for prosody, the intonational pattern was the main feature used to decide how similar the children’s imitation was to the experimenter’s prosody. The scores obtained for each component were added up to produce an overall imitation score per child (multimodal imitation score).

Object-Based Imitation Task

Following Subiaul et al. (Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016), in order to be awarded a point, children had to reproduce each step in the same order as it was produced by the female actor in the video. They were awarded 1 point if they imitated two consecutive actions in the correct order. For example, if children imitated Action 1 followed by Action 2, they were awarded 1 point; if they imitated Action 2 followed by Action 3, they were awarded 1 point; if they imitated Action 3 followed by Action 4, they were awarded 1 point, and if they imitated Action 4 followed by Action 5, they were awarded 1 point. Therefore, the maximum score was 4. However, if they imitated Action 1 followed by Action 3 they were not awarded any points, as they had not reproduced the first part of the sequence in the same order as in the video. If they imitated Action 1 followed by Action 2 but instead of imitating Action 3 next they imitated Action 4, then they were awarded just 1 point, as the first part of the sequence was correctly imitated but the second was not.

Inter-Rater Reliability

Inter-rater reliability between three coders was tested for narrative structure coding, pragmatic coding, and gesture/prosody imitation coding. It was felt to be unnecessary to check inter-rater reliability in the lexical content and object-based imitation coding because previous research has reported a high level of agreement between coders when coding verbal/lexical imitation (Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010) and object-based imitation (Kim, Óturai, Király & Knopf, Reference Kim, Óturai, Király and Knopf2015; Subiaul et al., Reference Subiaul, Zimmermann, Renner, Schilder and Barr2016). However, when coding narrative structure (Demir et al., Reference Demir, Fisher, Goldin-Meadow and Levine2014, Reference Demir, Levine and Goldin-Meadow2015; Vilà-Giménez et al., Reference Vilà-Giménez, Igualada and Prieto2019), social communication behaviors (Ingersoll & Schreibman, Reference Ingersoll and Schreibman2006), gesture imitation (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Óturai, Király and Knopf2015), and imitation of intonation contours (Loeb & Allen, Reference Loeb and Allen1993), agreement scores were significantly lower compared to lexical and object-based imitation results.

After a training session lasting roughly three hours (30 minutes for narratives, 2 hours for pragmatics, 30 minutes for gesture/prosody imitation), the three coders rated 20% of the data for the four above-mentioned tasks. Since the number of raters was three, Fleiss multi-rater kappa was used to calculate inter-rater reliability. For narrative structure coding, the results of the test showed an overall agreement of 71% and a Fleiss’ kappa of .72, indicating considerable agreement among the coders. As for the pragmatic scores, an overall agreement of 77% and a Fleiss’ kappa of .77 was obtained, showing a high agreement among the coders. Overall agreement for the gesture imitation coding was 76% with a Fleiss’ kappa of .76, indicating similarly a high level of inter-rater reliability. Overall agreement for the prosody imitation coding was 57% with a Fleiss’ kappa of .53, indicating only moderate agreement among coders. The lower inter-rater reliability scores obtained for prosody imitation (as compared to narrative structure, gesture imitation, and pragmatic scores) may have been due to the low volume used by children combined with background noise, which could have affected the interpretation of children’s utterances and the assessment of prosodic features.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses revealed that the object-based imitation scores were not normally distributed, as tested by the Shapiro-Wilk W-test, showing significant positive skew, even after log transformation. Therefore, the variable was transformed into a categorical variable defined by two groups (low (< 50) vs. high (≥ 50) performance).

The relationship between the children’s narrative and sociopragmatic skills and the two types of imitation (multimodal imitation and object-based imitation) was investigated in two different ways. First, correlations were checked for in exploratory fashion by means of Pearson’s tests for correlations between continuous variables and point-biserial correlation tests between continuous and categorical variables. Partial correlations were also conducted to evaluate the relationship between the variables without the influence of age. Second, the relative role of different imitation skills in predicting language abilities (narrative and sociopragmatic) was explored by means of multiple regression modeling. Two separate models were run in which narrative abilities and sociopragmatic abilities were separately included as dependent variables while the two imitation skills and age (in months) were entered as predictors. All continuous predictors were standardized before running the analysis. In all regression models, collinearity across predictors was checked. The condition number k for the multimodal imitation component scores, i.e., gesture, prosodic, and lexical components, and composite multimodal imitation score (an average of the three component scores of the multimodal imitation task) indicated harmful collinearity (Baayen, Reference Baayen2008). Therefore, the three multimodal imitation component scores were omitted from the final model and only a composite multimodal imitation score was used. An analysis of collinearity between the remaining predictors (composite multimodal imitation score, object-based imitation score, and age) showed that these predictors were not correlated with the others: the condition number k was 1.76, far below the threshold of 30 (Baayen, Reference Baayen2008), so all predictors were included in the regression. All statistical analyses were performed with R, version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019). The dataset is available in the Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/jkmtd/?view_only=4c594af98d83478e918ea45decd98eef).

Results

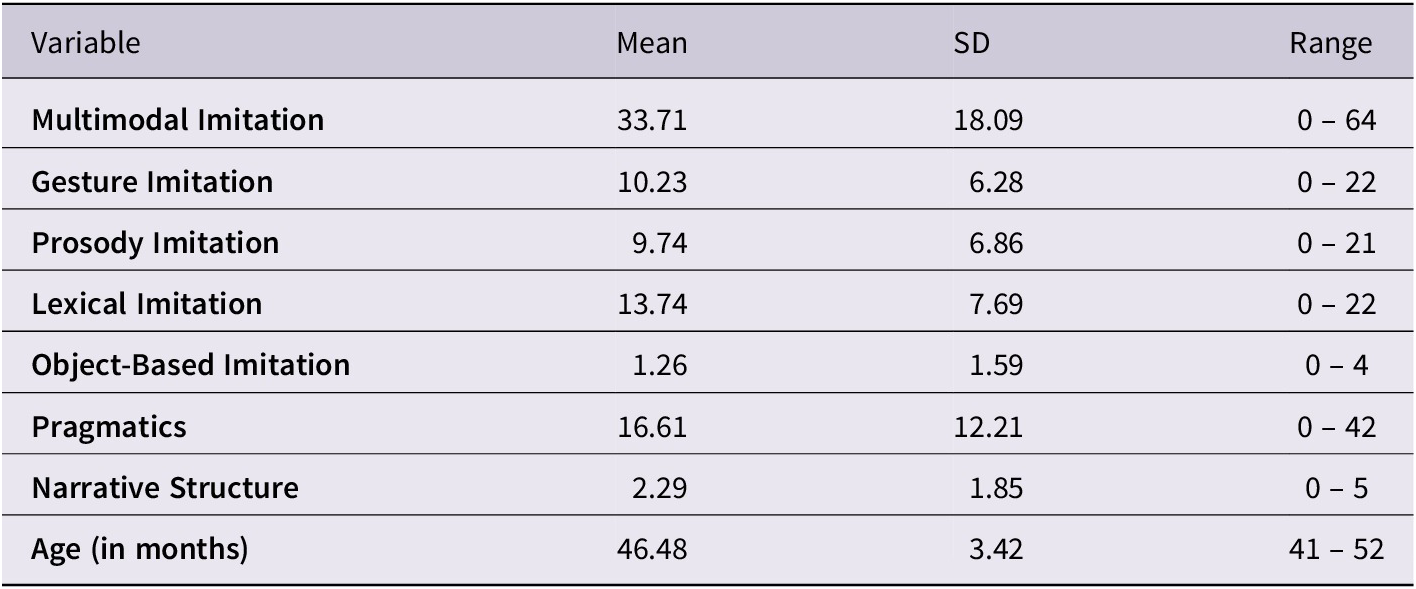

Descriptive statistics for all measures are reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for all measures

Note. The first column reports the name of the variable. The second and the third column report the mean and the SD of participants. The fourth column reports the range of scores.

The required sample size was determined post hoc using G*Power Version 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner & Lang, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009). We calculated post-hoc achieved power for the two linear multiple regression analyses that were performed and used inputs of .05 for alpha, 31 for total sample size, and 2 for the number of predictors. According to Cohen (Reference Cohen1988), .8 is a widely acceptable level of power, and both analyses yielded a sufficient level of power. In the case of the multiple regression analysis predicting pragmatic ability, the level of power was .999, and in the case of the multiple regression analysis predicting narrative skills, the level of power was .799.

In this section, we describe the results for multimodal imitation and its link with both narrative and sociopragmatic measures (with and without the effect of age), followed by the results regarding the relationship between object-based imitation and both narrative and sociopragmatic measures (with and without the effect of age). Then the role of the two types of imitation and age in predicting the narrative and pragmatic competences is described.

Multimodal Imitation

Correlations Between Different Components of Multimodal Imitation

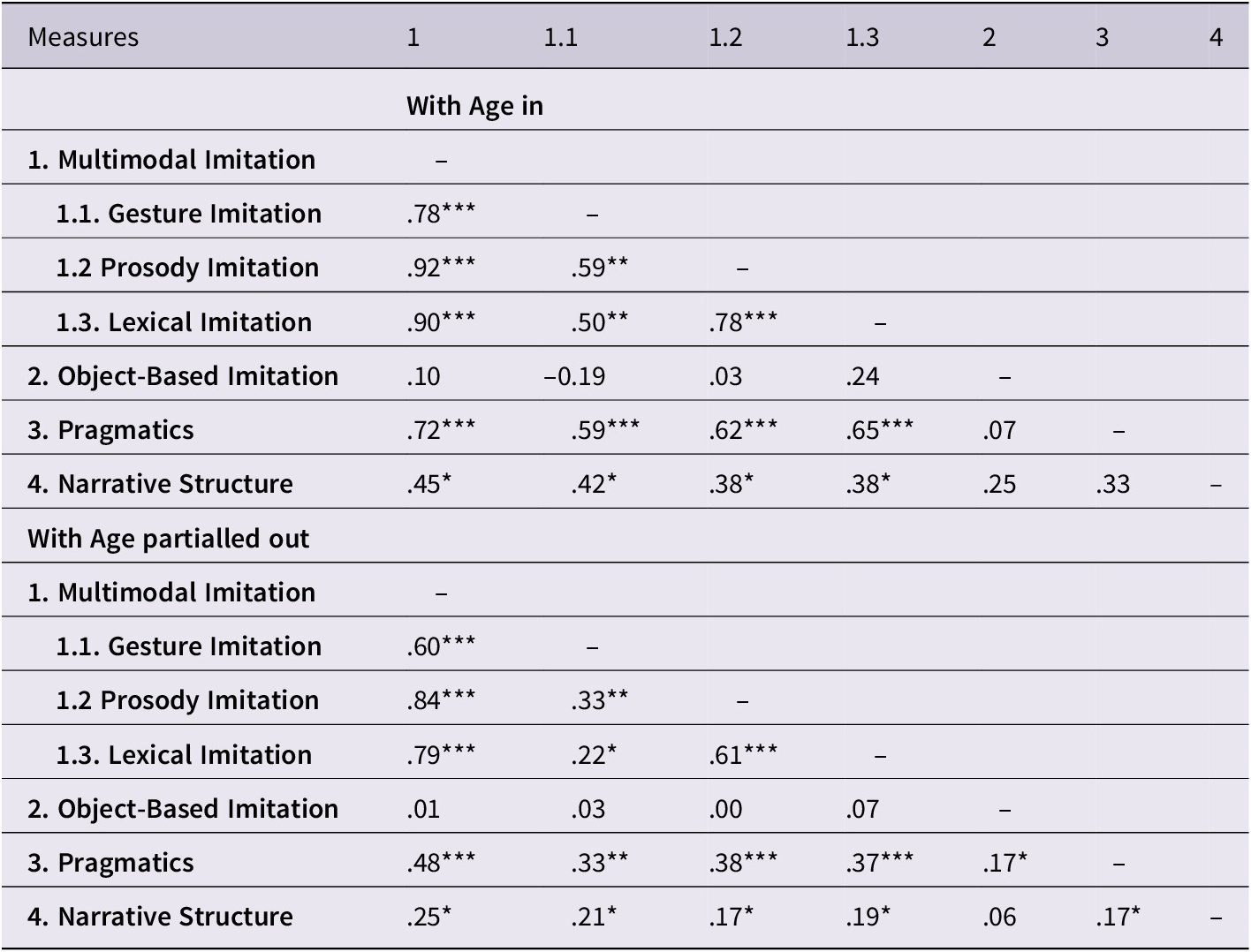

The Pearson bivariate correlation analysis found that the three components of the multimodal imitation score (gesture imitation, prosody imitation, and lexical imitation) were significantly correlated among themselves (see Table 4). Gesture imitation scores and prosody imitation scores were positively correlated and highly significant statistically, with a correlation coefficient of r(29) = .59, p < .001. This shows that children who imitated the target gestures more accurately also imitated the prosodic patterns more accurately, and vice versa. A moderate positive correlation was also found between gesture imitation and lexical imitation that was statistically significant, with a correlation coefficient of r(29) = .50, p = .004. In regards to the relationship between prosody imitation and lexical imitation scores, the statistical analysis showed that they were highly and positively correlated, with a correlation coefficient of r(29) = .78, p < .001.

Table 4. Correlations between all measures with and without language partialled out

Note. Correlations and partial correlations between narrative structure scores and gesture imitation scores, prosody imitation scores, lexical imitation scores, multimodal imitation scores, object-based imitation scores, and age. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Correlations with Narrative and Sociopragmatic Skills

The Pearson bivariate correlation analysis revealed a positive relationship between multimodal imitation scores and both narrative structure scores and sociopragmatic scores. As for the narratives, the correlation coefficient was r(29) = .45, p = .011. Therefore, children with better multimodal imitation abilities also produced a better narrative structure and vice versa. Moreover, all three components of multimodal imitation (gesture, prosody, and lexical content imitation) were also found to be significantly correlated with children’s narrative scores (see Table 4).

Regarding the relationship between multimodal imitation and sociopragmatic abilities, the Pearson bivariate correlation analysis found that multimodal imitation scores and sociopragmatic scores were highly and significantly correlated, with a correlation coefficient of r(29) = .72, p < .001. Therefore, children with better multimodal imitation abilities produced more pragmatically appropriate responses and vice versa. Additionally, all three components of multimodal imitation were also found to significantly correlate with children’s sociopragmatic scores (see Table 4).

These relationships retain significance even after age effect has been partialled out of the correlations (all ps < .03).

Object-Based Imitation

Correlations with Narrative and Sociopragmatic Skills

Correlations between object-based imitation and both narrative and pragmatic abilities were also examined (see Table 4). However, no significant correlations emerged (all ps > .07). Partialling out the effect of age did not change the pattern of results (all ps > .2).

Predicting Pragmatic Skills

Multiple Regressions

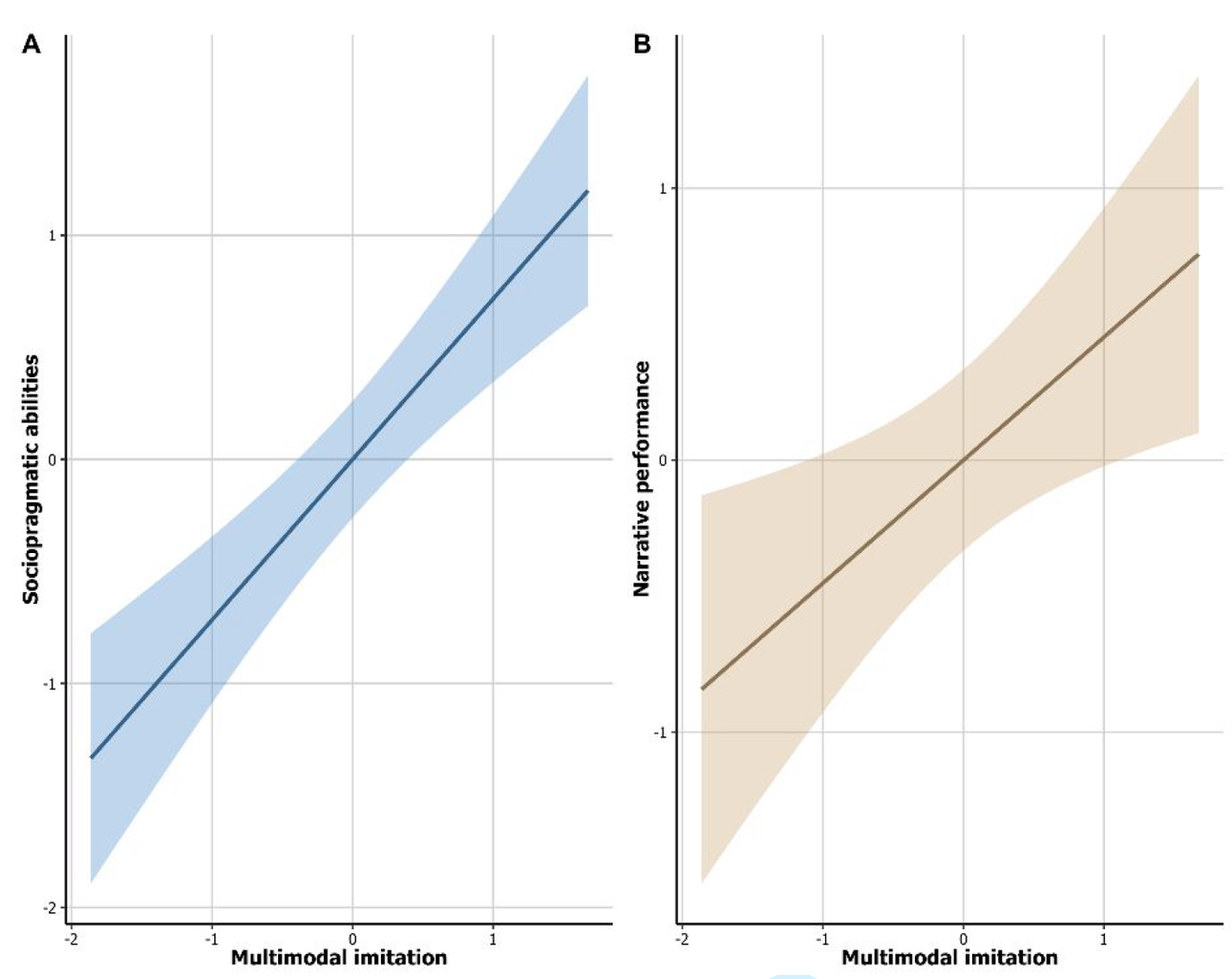

The multiple regression analysis investigated possible predictors of children’s pragmatic skills. The model included the two imitation scores (multimodal imitation and object-based imitation) and age as independent variables and pragmatic ability as a dependent variable. The three factors together explained 57% of the variance (R2 = .57, F(3,27) = 12.1, p < .001). However, only multimodal imitation turned out to be a significant predictor of pragmatic skills (β = 11.37, p < .001) while the other variables were not significantly predictive: β = 4.39, p = .063 for age, and β = 4.39, p = .751 for object-based imitation score. This model indicates that as multimodal imitation scores increase, the predicted pragmatic ability score increases.

An additional analysis assessing the relationship between the three different types of gesture imitation scores (iconic, metaphoric, and conventional) and their relationship with pragmatic abilities confirmed that all three types of gestures in the multimodal imitation composite score were predictors of pragmatic abilities (βs = .66 – .69, p < .001).

Predicting Narrative Skills

Multiple Regressions

In the multiple regression analysis investigating predictors of narrative ability, the two imitation scores (multimodal imitation and object-based imitation) and age were set as independent variables and narrative score as a dependent variable. This model had an explained variance of 31% (R2 = .31, F(3,27) = 4.03, p = .017). Multimodal imitation was the only significant predictor (β = 11.83, p = .006). Both object-based imitation (β = 12.09, p = .168) and age (β = –5.61, p = .163) were not predictive of narratives. The model shows that as multimodal imitation scores increase, the predicted narrative ability score increases too (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Relationship between Sociopragmatic Abilities, Narrative Performance, and Multimodal Imitation

Note. Results of the multiple regression analysis of the relationship between sociopragmatic abilities, narrative performance, and multimodal imitation.

An additional analysis of the influence of the imitation accuracy of the different kinds of gestures showed that iconic and conventional gestures were predictive of narrative scores (β = .43, p = .016 for iconic gestures; β = .47, p = .008 for conventional gestures), while metaphoric gestures were not (β = .25, p = .017).

Discussion and Conclusions

The main goal of the present study was to examine the relationship between narrative performance, sociopragmatic abilities, and multimodal imitation abilities (as opposed to object-based imitation abilities) in typically developing children between 3 and 4 years of age. The results of the two regression analyses showed that while multimodal imitation abilities (i.e., the ability to simultaneously imitate gestures, prosody, and lexical content) are predictive of narrative and sociopragmatic skills, this is not the case for object-based imitation abilities. Our results thus show clear evidence that multimodal imitation abilities continue to be related to language skills at later stages of development – namely, during the preschool years. The present findings broaden the results of previous studies reporting early positive associations between different types of linguistic imitation and language development (e.g., Bates et al., Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979; Snow, Reference Snow, Speidel and Nelson1989; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Nagell and Tomasello1998; Masur & Eichorst, Reference Masur and Eichorst2002; Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Tomasello and Striano2005) and social communication behaviors in earlier stages of development (e.g., Hanika & Boyer, Reference Hanika and Boyer2019; Heimann et al., Reference Heimann, Strid, Smith, Tjus, Ulvund and Meltzoff2006).

It is important to note that the relationship found between sociopragmatic abilities and multimodal imitation abilities is stronger than the one found between narrative performance and multimodal imitation. These results support the idea that typically developing children use the social function of imitation to learn more complex social communication skills in infancy and early childhood (Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2008b) and strengthen the view that the social function of imitation is also relevant as children grow up and are able to produce more complex language. Similarly, previous research on children with ASD has shown that imitation deficits and impairments in social communication skills are related to each other (see Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2008b for a review) and that it is more difficult for these children to imitate social behaviors (Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2008a).

While multimodal imitation correlated with both language measures (i.e., narrative performance and sociopragmatic abilities), object-based imitation did not correlate with either of them. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the relationship between language and sociopragmatic skills in preschool children is compared to both object-based imitation abilities and multimodal imitation abilities. The results clearly show that short-term memory abilities related to imitation of temporal/spatial sequencing of common actions on objects are not related to language, while short-term memory abilities of contextually-relevant multimodal imitation patterns are. This finding supports the idea that the ability to imitate the social significance of multimodal input is a key indicator of linguistic and pragmatic development in young preschoolers. Moreover, the asymmetric findings regarding the difference between the two types of imitation tasks reinforce previous results with younger children indicating that multimodal imitation behaviors in typically developing children aged between 9 and 20 months have stronger links to language and social communication abilities than imitation tasks involving objects (see Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010; Masur & Ritz Reference Masur and Ritz1984; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse and Wehner2003). Crucially, Ingersoll and Lalonde (Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010) corroborated the beneficial role of gesture imitation tasks over object-based imitation tasks in language therapy settings with older children with ASD.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first one to have jointly assessed gesture, prosody, and lexical imitation patterns, showing how the different components involved in multimodal imitation (i.e., prosodic, gestural, and lexical) are closely related not only among themselves but also with narrative and sociopragmatic abilities. All in all, in our view, the results of this study expand and complement the results of previous investigations by highlighting the fact that the strong relationship between gesture, prosody, and speech is not only present in adult speech and in development, but is also present in imitation tasks in young preschoolers. Moreover, this result strengthens the validity of the argument presented in previous research according to which prosody and gesture can be regarded as sister systems due to their close relationship in development at the temporal, semantic, and pragmatic levels (see Hübscher & Prieto, Reference Hübscher and Prieto2019, for a review).

In sum, our results reinforce the view that multimodal imitation abilities are key for language learning and social communication also during the preschool years. Focusing on children with language impairment, Wray et al. (Reference Wray, Saunders, McGuire, Cousins and Norbury2017)’s study reported that 4- to 5-year-old children with LI showed weaknesses in gesture accuracy (gesture imitation and gesture elicitation) in comparison to their typically developing peers, while no differences in gesture rate were reported. It is thus not surprising that training in multimodal abilities (and their integrated components) can be successfully used in language therapy contexts to trigger greater gains in the rate of language use and to enhance children’s social communication skills. One of the best examples of this type of training is Ingersoll’s Reciprocal Imitation Training, a naturalistic behavioral intervention designed for teaching spontaneous imitation to young children with ASD by means of play interactions with a play partner (Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2008b; see Ingersoll & Lalonde, Reference Ingersoll and Lalonde2010; Ingersoll & Schreibman, Reference Ingersoll and Schreibman2006). Verbal imitation is used in this approach in combination with object-based and gesture imitation. More recent treatments have used role-play, a form of imitation integrated into a pragmatic context, to improve pragmatic skills in children with language learning disabilities (Abdoola, Flack & Karrim, Reference Abdoola, Flack and Karrim2017). Some interventions like melodic-based communication therapy or melodic intonation therapy have focused specifically on verbal and vocal imitation. Melodic-based communication therapy has been shown to be effective for improving expressive vocabulary, verbal imitative abilities, and even pragmatics in children with ASD (Sandiford, Mainess & Daher, Reference Sandiford, Mainess and Daher2013). Also a widely used treatment, melodic intonation therapy is based on the use of musical elements of speech. This technique has been applied for language rehabilitation and the improvement of verbal expression in aphasic patients (Norton, Zipse, Marchina & Schlaug, Reference Norton, Zipse, Marchina and Schlaug2009) and in children with ASD (Miller & Toca, Reference Miller and Toca1979). All things considered, the success of these treatments shows the importance of imitation for enhancing language learning and social communication skills.

Therefore, the results of the present investigation complement previous research with infants and children with ASD and indicate that the relationship between multimodal imitation, language, and social communication is relevant also in typically developing preschool children. Future studies could go in the direction of developing multimodal imitation training paradigms that combine socially relevant gesture, prosody, and verbal imitation for typically developing preschool children, as they can be useful tools to facilitate the language acquisition process. Also, more attention should be paid to assessing the role that natural interactive patterns of social multimodal imitation play in preschoolers’ language development. In short, it seems clear that the different components of multimodal imitation are tightly linked to each other and jointly form a communicative system that is closely related to children’s language and sociocommunicative development.

All in all, the fact that socially relevant multimodal imitation patterns are significantly associated with sociopragmatic abilities and narrative performance in young preschoolers in the present study highlights the need within the language development field to take more seriously the relevance of multimodal imitation capacities during children’ development. Importantly, the findings in this paper advocate for a broader conceptualization of language-based imitation behaviors that systematically integrates socially relevant prosodic, gestural, and lexical linguistic patterns.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the schools Escola Brusi and Escola Bogatell, where the experiment was conducted. Our grateful thanks are also extended to the children that participated in the present work and their families. We also thank Ainhoa David for her assistance in administrating the tests, Anna Massanas for her willingness to participate in the recording of the audio-visual stimuli for this research project, and the audio-visual technicians at Universitat Pompeu Fabra for helping us record the audio-visual stimuli. Additionally, we owe our gratitude to Jelena Grofulovic, Ingrid Vilà-Giménez, and Júlia Florit for helping us conduct the inter-rater reliability for the present project. We are also indebted to Gemma Boleda and Alfonso Igualada for their helpful and inspiring comments. This study benefited from funding awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (PGC2018-097007-B-100 “Multimodal Language Learning (MLL): Prosodic and Gestural Integration in Pragmatic and Phonological Development”) and by the Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 SGR_971) to the Prosodic Studies Group. Iris Hübscher was supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship by the URPP Language and Space (University of Zurich) during the preparation of this work. Mariia Pronina also acknowledges an FI grant from the Generalitat de Catalunya (ref. 2019FI_B1 00120).

Authors Note

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.