Women tend to be severely underrepresented in legislative bodies around the globe; as of today, only 25.1 per cent of all members of national parliaments are women (Inter‐Parliamentary Union 2020). Gender quotas are an affirmative action policy, designed to address this deficit of representation. In particular, legislated candidate quota laws require that the pool of candidates fielded by any political party be gender‐balanced. This way, an attempt is made to guarantee that a stipulated minimum proportion of candidates be women. Is this solution effective? Does it facilitate a rise in women's descriptive (numeric) political representation to the levels that would not have been reached in the absence of quotas? In this article, we emphasise that such questions do not lend themselves easily to a systematic examination. Between‐country comparisons – that is, comparisons between countries that have installed quotas and those that have not – are prone to selection bias, all too often encountered by students of comparative politics; countries relying on gender quotas might differ systematically from those that do not resort to introducing such a solution. Within‐country studies, comparing female descriptive representation in pre‐quota and post‐quota periods, have also come under criticism. While gender balance in elected bodies often improves following the installation of quotas, it might have been the case already before quota introduction (Górecki & Kukołowicz Reference Górecki and Kukołowicz2014: 66). The observed enhancement of women's descriptive representation might thus be due to certain inherent trends rather than due to quotas. Consequently, even the relatively refined attempts to study the impact of quotas from a longitudinal perspective (Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010; Paxton & Hughes Reference Paxton and Hughes2015) suffer from the lack of an adequate control group to which the countries introducing quotas could be compared.

In this paper, we attempt to address the aforementioned difficulties in establishing causality with respect to the impact of legislated candidate quotas under preferential voting rules. More precisely, we focus on open‐list proportional representation (PR) systems. We argue that such systems constitute a critical, unobvious case for the assessment of the effectiveness of quotas. In systems with preferential voting, electors have the right to disturb the order of candidates on the lists put forward by parties. This may put women in a favourable position because they may capitalise on identity politics, seeking personal votes based on gender (Valdini Reference Valdini2012: 742). However, stereotypes held by the electorate, often unfavourable to women candidates (e.g., Huddy & Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), may find its expression in voter choice and thereby hamper the rise in women's representation. (For a recent general account of gender stereotyping in the context of decision‐making positions, see Shurchkov & van Geen Reference Shurchkov and Geen2019.)

We evaluate the effectiveness of legislated candidate quotas in three European democracies electing their national parliaments by means of variants of open‐list PR rule. These are Belgium, Greece and Poland. We, first, quantitatively examine the impact of quota laws on women's descriptive representation. In order to establish causality in a valid manner, we employ the generalised synthetic control method (Xu Reference Xu2017). We then qualitatively interpret the findings, with reference to scholarly literature on the three countries’ broadly conceived political landscapes. The results we obtain vary substantially between the three settings. Overall, they suggest that the impact of legislated candidate quotas under preferential voting systems is rather limited. Such effects can be strong, but only as long as additional contextual factors operate, facilitating a smooth translation of quota laws into parliamentary seats occupied by women. Based on our results and the extant literature, we argue that a number of such critical factors were present in Belgium, a country constituting a ‘success story’ when it comes to enhancing women's descriptive representation. Candidate quotas introduced in more adverse settings, such as Poland or Greece, have way weaker effects.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section discusses the existing evidence with respect to the impact of legislated candidate quotas in preferential voting systems. The third section focuses on the broadly conceived methodological aspect of our study. The fourth section presents the results of the generalised synthetic control analyses of quota effects in Belgium, Greece and Poland. The fifth section is devoted to a qualitative interpretation of our quantitative findings. The last section concludes the article.

Contentious effects of legislated candidate quotas in preferential voting systems

Preferential voting systems, especially open‐list PR, tend to pose a challenge to students of the effects of quotas on female descriptive political representation. Those rules offer voters the opportunity of both supporting their favourite party and selecting a specific candidate or candidates based on their personal attributes and traits. Such a spectrum of choice is inexistent under the most widely used alternative rule, namely closed‐list PR. Once the latter is applied, a gender quota, as long as it is accompanied by a requirement that female candidates are represented among those featuring in high list positions (placement mandates), brings an inevitable, purely ‘mechanical’ increase in the proportion of women holding elected office (e.g., Corrêa & Chaves Reference Corrêa and Chaves2020). Under PR with preferential voting, ‘cultivating a personal vote’ (Carey & Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995) is crucial. Thus, being ranked high does not automatically guarantee winning elected office, and being ranked low does not always lead to an electoral loss. In fact, there are good reasons to argue that the typically high correlations between candidates’ list rankings and the numbers of preferential votes are largely spurious; some of the studies focusing on random or quasi‐random candidate order indicate that in high‐salience, high‐information elections to national parliaments, the impact of list position on a candidate's electoral success is weak (Ortega Villodres Reference Ortega Villodres2003; Lutz Reference Lutz2010, but see Corrêa & Chaves Reference Corrêa and Chaves2020 for an inventive non‐experimental comparison suggesting a somewhat stronger effect).Footnote 1 This makes legislated quota effects sensitive to numerous contextual factors, far beyond the mere ‘mechanics’ of quota regulations.

Jones and Navia (Reference Jones and Navia1999) were perhaps the first to express scepticism with respect to the effectiveness of legislated candidate quotas under preferential voting PR rules. Their analyses of Chilean municipal elections indicated that quota effects under open‐list PR did not compare to those observed in closed‐list systems. Largely similar conclusions have been drawn by Gray (Reference Gray2003) in her comparative study of Argentina and Chile. Both the aforementioned studies emphasise the lack of adequate resources to run an effective personal campaign as the core factor contributing to the relatively weak effects of legislated quotas under open‐list PR. The scepticism has been further fuelled by the somewhat spectacular failure of legislated candidate quotas in Brazil, a case depicted in, among others, Miguel's (Reference Miguel2008) study. In Miguel's view, the chief factor behind that lack of success was an unfortunate construction of the quota law itself; the regulations effectively allowed a party not to include a legally stipulated proportion of women on a list without violating the quota. Nonetheless, as Gray (Reference Gray2017) argues, the 2009 amendment of the Brazilian quota law brought little change to the picture sketched by Miguel. This is because of factors such as poor enforcement of quotas and party‐level fragmentation of the Brazilian Congress. Furthermore, limitations of legislated quotas were observed also in Indonesia (Hillman Reference Hillman2018) and Poland (Millard Reference Millard2014; Gendźwiłł & Żółtak Reference Gendźwiłł and Żółtak2020, but see Jankowski & Marcinkiewicz Reference Jankowski and Marcinkiewicz2019).

Notwithstanding the above, evidence suggesting promising effects of quotas under PR with preferential voting has also appeared. For example, Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2003) and Gray (Reference Gray2017: 367–368) point to the experience of Peru where a favourable mixture of contextual circumstances, including the concentration of a pro‐female electorate in Lima, have apparently contributed to a very substantial increase in the proportion of women in the national parliament. Importantly, that effect was observed at the time when the Peruvian legislated quota was not yet accompanied by a placement mandate (Gray Reference Gray2017: 359). Claims that candidate quotas can be effective in preferential voting systems is reinforced by evidence from Belgium where quota effects seem to have been as impressive as in Peru (Weeks Reference Weeks2016). Furthermore, influential comparative cross‐country studies (Jones Reference Jones2009; Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010; Paxton & Hughes Reference Paxton and Hughes2015) have largely corroborated the hypothesis that, more often than not, legal quotas should exert at least some positive impact on women's descriptive political representation under preferential voting rules. Of course, such effects are typically weaker than the ones observed in some other electoral systems, especially closed‐list PR (Schwindt‐Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2009). But it is precisely this uncertainty, introduced by voters’ ability to disturb party ballots, that makes studying quotas in preferential voting systems an endeavour worth undertaking. It is so not only due to the fact that the evidence amassed thus far is mixed, but also because there are few analyses establishing causal effects of quotas under open‐list PR in a methodologically compelling manner. Valuable exceptions here are studies of local elections in Italy (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014, Reference Baltrunaite, Casarico, Profeta and Savio2019) and Sweden (Besley et al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017, studying party quotas). Evidence from the former country (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014) shows strong effects of legislated quotas despite the absence of placement mandate provisions. Unfortunately, the fact that the focus of nearly all such work is on local politics poses problems with generalizations; stereotypes held by voters tend to hamper women's chances of winning nation‐level electoral contests, but not necessarily so if a local office is at stake (e.g., Huddy & Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). Methodologically rigorous studies focusing on national parliamentary elections should thus fill an important gap in the extant literature.

Methods, cases, data and variables

Methods

In this study, we set out to evaluate the impact of quotas on women's descriptive representation, going beyond the purely correlational modes of inference. In order to enhance the validity of our causal inferences, we apply the generalised synthetic control (GSC) method (Xu Reference Xu2017), one of the most recent steps in the development of synthetic control methodology (Abadie et al. Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010). The methodology facilitates the comparative study of various events or interventions. It rests on the idea that a weighted sum of a set of control units would typically constitute the best control case, resembling the pre‐treatment trajectory of the studied outcome observed for the treated entity. The method seems to be a compelling tool for the analysis of electoral effects. Xu (Reference Xu2017) himself illustrated its features with an analysis of the effects of election‐day registration on voter turnout in the United States (see Pierzgalski et al. Reference Pierzgalski, Górecki and Stępień2020, for another application in the area of electoral studies). In this contest, it is worth mentioning that GSC is a less assumption‐dependent generalization of difference‐in‐differences quasi‐experimental design (Xu Reference Xu2017: 58). The latter was implemented by some existing studies of quota effects in local elections held under open‐list PR (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014; Besley et al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017). Moreover, unlike with another quasi‐experimental technique, regression discontinuity design (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Casarico, Profeta and Savio2019; Bagues & Campa Reference Bagues and Campa2021), GSC is applicable to national parliamentary elections. This is because it does not rest on the presence of heterogeneous electoral rules applying to the same level of government.

To the best of our knowledge, the only effort so far to implement synthetic control methodology for the purpose of the evaluation of the effects of legislated candidate quotas is Weeks’ (Reference Weeks2016: 88–91) study. She implemented the ‘classic’ version of the method (Abadie et al. Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010) and the sole preferential voting setting that she analysed was Belgium. The results she obtained point to a strong positive impact of quotas in that country, the effect of quota law on female descriptive representation exceeding 20 percentage points (henceforward pp). This is explained by the extraordinary strength of the Belgian quota law (Weeks Reference Weeks2016: 90–91). However, we argue that Weeks’ analysis overlooks a potentially important confounder, namely the reform of electoral districts, implemented in 2003 (Meier Reference Meier and Tremblay2008). The reform resulted in a substantial increase in the average party magnitude, a crucial predictor of women's electoral success (Matland Reference Matland1993). We thus conduct our own analysis for Belgium, controlling for a proxy for party magnitude and relying on the more flexible GSC method. We further implement that method to extend our knowledge of quota effects by means of an analysis of two other open‐list PR settings: Greece and Poland.

Cases

Of the three countries that we focus on, Belgium was the first to introduce legislated candidate quotas. The respective law was passed in 1994 but the first national parliament election that followed, held in 1995, was exempt from quota regulations. They thus took effect during the subsequent election, held in 1999. The law required that candidates of any gender did not constitute more than two‐thirds of all candidates featuring on any district‐level party list. The enforcement mechanism accompanying this requirement has been very strong, the electoral authorities being unqualifiedly obliged to refuse registration of a list that does not fulfil the quota. In 2002, the quota size was raised to the level of 50%. In addition, placement mandates were introduced, maintaining that candidates of the same gender could not occupy the top two positions on any list. During the first election following the quota amendment, held in 2003, placement mandates were less strict, however: one of the top three candidates had to be of each gender. The 2002 amendment of the quota law took its full effect starting from the election held in 2007 (Meier Reference Meier, Ballington and Binda2005: 54).

Greece introduced its candidate quota regulations in 2008 and they took effect during the national parliamentary election held a year later. The 2008 law required that at least one‐third of every party's nationwide candidate pool be of each gender (the quota size was raised to 40% starting from 2019). No placement mandates are included in those regulations. At the same time, the Supreme Court is obliged to decline registration of a party's ballot if the quota is not met (Verge Reference Verge2013: 448; Anagnostou Reference Anagnostou, Lépinard and Marín2018: 176). The fact that the quota applies nationwide rather than to each district‐level party list is a factor that potentially curbs the impact of quotas. Under such arrangements, parties may be tempted to place women disproportionately in districts where a party itself is weak, as it once used to be done in Mexico (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2016).Footnote 2

Finally, Poland introduced its legislated candidate quota arrangements in January of 2011 and the law was first applied to the national parliamentary election held in October that same year. The quota size is equal to 35% and it applies to every district‐level party list. No provisions regarding the placement of candidates within lists have been included in the law. As with Belgium and Greece, quota enforcement mechanisms are very strong; a party list not abiding by the quota is simply declined registration by electoral authorities (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2015).

We study the evolution of the proportions of women in the lower chambers of the Belgian and Polish parliaments as well as in the single‐house parliament of Greece. Due to data availability limitations, we focus on the 27‐year period between 1993 and 2019. In our effort to find an appropriate control group, we identify the European states whose lower (or single) houses of parliament meet three criteria. First, they must be elected by means of a proportional formula (with one exception, see below). Second, the electoral formula has to allow preferential voting for a candidate or candidates from a district‐level pool fielded by parties. Third, legal candidate quotas must not have been installed. The following 17 countries fulfil all these three conditions: Austria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, San Marino, Slovakia, Sweden and Switzerland. Partial unavailability of data forced us to exclude San Marino from the control group.

Nearly all the aforementioned control states use a variant of open‐list PR. The only exception is Malta, implementing the single‐transferable‐vote rule, often classified as semi‐proportional. In a way, we are forced to have Malta among the control group. Otherwise, it would be impossible for us to obtain valid and reliable estimates for Greece. The latter country, with its low level of female descriptive representation, especially at the beginning of the analysed period, is an outlier among European preferential voting democracies. This is unfortunate as the inability of explaining outlying cases in a valid and reliable manner is the most fundamental limitation of synthetic control methodology, regardless of the exact algorithm used (Xu Reference Xu2017: 72). The inclusion of Malta, a country whose parliament sees an even lower proportion of female members than that of Greece, greatly improves the validity of our estimates. Fortunately, the electoral system of Malta offers virtually unrestricted opportunities to cast preferential votes for candidates. We also note that Sweden implemented preferential voting starting from 1998. We thus include this country in the analyses for Greece and Poland, but not for Belgium which held its first post‐quota election in 1999. That said, we emphasise that our main analyses are followed by sensitivity tests, aimed at evaluating the consequences of inclusion (exclusion) of Malta and Sweden in (from) the analysis.

Data and variables

The dependent variable in our study is the proportion of women (in per cent) in a lower (or single) chamber of a country's national parliament. The annual figures on women's parliamentary representation were taken from the Inter‐Parliamentary Union's PARLINE database (Inter‐Parliamentary Union 2020).Footnote 3 Notwithstanding the fact that control variables are not necessary to perform a GSC analysis, the inclusion of appropriate controls improves model fit and thereby the validity of estimates (Xu Reference Xu2017). We thus rely on a number of such predictors. First, we take into account the aforementioned proxy for party magnitude, controlling for a ratio of average district magnitude to the effective number of electoral parties, both extracted from the updated version of Bormann and Golder's (Reference Bormann and Golder2013) database of electoral systems. We also account for a country's overall level of development. To that end, we rely on the Human Development Index (HDI), compiled by the United Nations (United Nations 2019).Footnote 4 In addition, we rely on data on governance quality, compiled by the World Bank (2019b). We aim to account for the fact that the extent of democratic rights and civil liberties tends to positively affect female representation (Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010). We thus control for the voice and accountability index, capturing ‘perceptions of the extent to which a country's citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media’, and the rule of law index, capturing ‘perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence’. To take into account the conjectures that at times of political instability and onsets of violence women are less likely to be supported by voters (Lawless Reference Lawless2004), we also include the political stability and absence of violence indicator, measuring ‘perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism’ (World Bank 2019b). Another predictor of women's political representation, emphasised by the extant literature, is the extent of women's paid labour activity (Stockemer & Byrne Reference Stockemer and Byrne2011). We thus control for women's share in a country's workforce and female unemployment rate, based on data from the World Bank (2019a). We take further three variables from the same source: a country's population, its proportion of rural population and per capita gross domestic product (GDP). Furthermore, we control for a variable indicating to what extent parties in a respective country rely on their own voluntary gender quotas for national parliament candidates, including, for each parliamentary term, the proportions of seats won by parties that have installed such internal regulations. The respective variable was calculated on the basis of Lépinard and Rubio‐Marín (Reference Lépinard, Rubio‐Marín, Lépinard and Marín2018: 13–21) and IDEA's (2020) data on gender quotas. Also, because most significant changes to female parliamentary representation tend to occur during election years, we control for the number of elections held in a country in the period starting in 1993, that is, the first year covered by our analysis, and ending in a given election year. In the end, the existing literature points to the prevalence of corruption as a predictor negatively correlated with women's descriptive political representation (Stockemer Reference Stockemer2011). However, as Esarey and Schwindt‐Bayer (Reference Esarey and Schwindt‐Bayer2019) demonstrate, the relationship between the two variables is endogenous, taking the form of a causality loop. Because controlling for an endogenous covariate leads to biased estimates, we refrain from controlling for corruption levels in our analysis.

Results

Trends and overview of estimation results

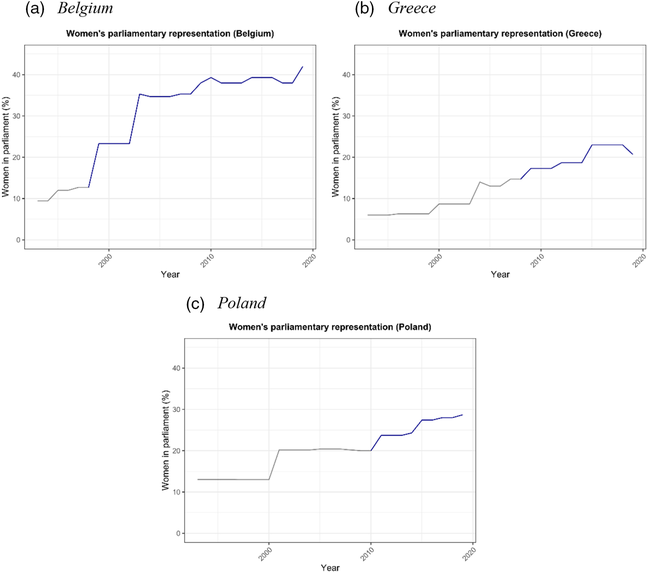

Figure 1 presents the evolution of the proportion of women in the parliaments of Belgium, Greece and Poland over the 1993–2019 period. In 1993, the proportions of women in the parliaments of Belgium, Greece and Poland were equal to 9.4, 6.0 and 13.0 per cent, respectively. The implementation of quotas in Belgium in 1999 is accompanied by a sharp increase in that proportion. This is followed by a comparable increase in 2003. In 2019, there were 42% of women among Belgian MPs. The corresponding trends for Greece and Poland are way flatter, including the post‐quota developments. The 2019 figures are equal to 20.7% for the former country and 28.7% for the latter one, respectively. A summary of GSC estimation results for all the three countries is presented in Table 1. Below, we discuss the results case by case.

Figure 1. Trends in women's descriptive parliamentary representation (1993–2019). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

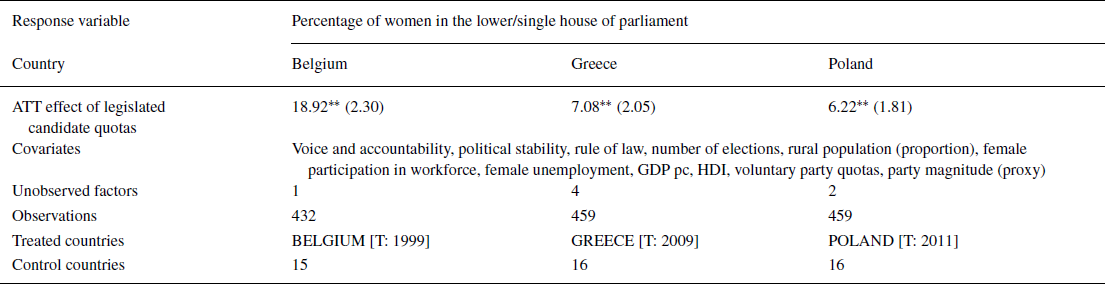

Table 1. Overview of GSC estimates

** p < 0.01; note: main entries are ATT effects and the numbers in round brackets are standard errors.

Belgium

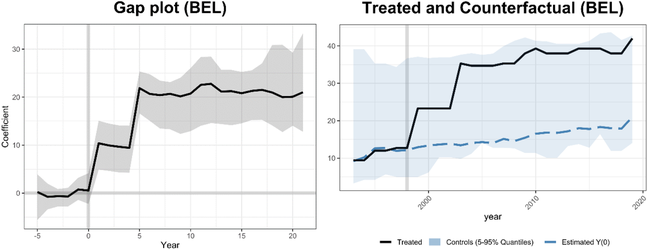

The results we obtain for Belgium seem unequivocal. The average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) over the 1999–2019 period equals 18.92 pp and is highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). This means that, following the introduction of quotas, the proportion of women in the lower chamber of the Belgian parliament is, on average, 18.92 pp greater than for the synthetic control unit (counterfactual). The result is remarkably similar to that obtained by Weeks (Reference Weeks2016: 91), albeit it must be remembered that the two analyses differ with respect to the control cases, timespan and the estimation method. In Figure 2, the left panel shows the gap between Belgium and its synthetic control, while the right one presents the temporal evolution for both the units. A number of conclusions can be drawn based on the two plots. First, we notice that during the pre‐quota period (1993–1998) the differences between Belgium and its counterfactual are minor, all below 1 pp. As the gap plot demonstrates, they are also statistically insignificant (p > 0.05), the accompanying 95 per cent CIs encompassing zero. This is reassuring and boosts our confidence in the comparability of the two units.

Figure 2. GSC analysis: Belgium. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Despite the initial lack of placement mandates, the quota implemented for the 1999 election has an instant effect, the difference between Belgium and the synthetic control unit, in favour of Belgium, exceeding 10 pp that year. The effect is highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). Between 1999 and 2002, we see the gap being subject to only minor fluctuations. In 2003, however, it rose to about 22 pp. Curiously, the increase occurs in advance of the full implementation of the strengthened quota requirements. A plausible explanation to this rests on the fact that the full quota provisions, scheduled to be binding in 2007, were met by two‐thirds of all major parties’ lists already in 2003.Footnote 5 Accordingly, the lack of an additional effect in 2007 reflects the fact that the surplus associated with a strengthened quota law was largely ‘consumed’ in 2003. In fact, from 2004 onwards we see a mostly lateral trend with respect to the gap in female descriptive representation between the Belgian House of Representatives and its synthetic counterfactual. Finally, we note that, in 2003, a substantial effect of the strengthened quota occurred despite the simultaneous doubling of party magnitude. The results thus resemble those obtained by Weeks (Reference Weeks2016). Also, in the light of these results, Meier's (Reference Meier and Tremblay2008) claim that the observed effect of the strengthened legal quota was just a disguised effect of party magnitude seems unsubstantiated. This is reinforced by additional analyses for which we exclude the latter variable and obtain effects of quotas largely similar to those presented here (Supporting Information Appendix Figure A1).

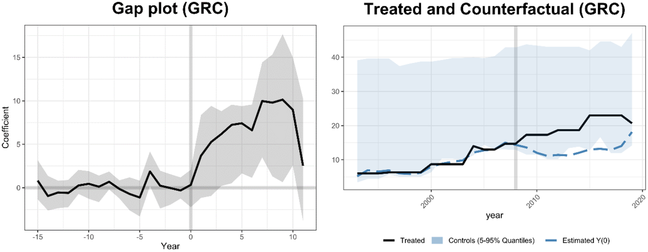

Greece

For Greece, the ATT effect of legislated candidate quotas over the 2009–2019 period is equal to 7.08 pp (p < 0.01). The evolution of the effect is depicted graphically in Figure 3. The pre‐treatment match between the two compared units is very good. The positive effect of quota arrangements occurs directly following the implementation of the law, that is, at the 2009 election. However, despite the gap in favour of Greece reaching the value of about 3.68 pp, it is statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). It becomes significant in 2011 when it reaches the value of about 6.19 pp. However, we notice that, at that moment, the gap between Greece and its counterfactual increases because of a decline in female descriptive political representation that affects the latter unit. This is driven largely by a decrease in female parliamentary representation in a number of countries from the control group, most notably Cyprus, Estonia, Iceland and Slovakia, in the years 2011–2012.

Figure 3. GSC analysis: Greece. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The aforementioned drop in the proportion of women for Greece's counterfactual turns out not to be lasting. Nonetheless, the good performance of the left‐wing SYRIZA during the 2012 election (Dinas & Rori Reference Dinas and Rori2013) and its victory three years later (Rori Reference Rori2016) appear to have caused the gap between Greece and its counterfactual to persist and even increase to the level of about 10 pp. However, the most recent election, held in 2019, marks a decline of the effect of quotas in spite of quota size having been raised to the level of 40 per cent. The counterfactual synthetic control unit tends to close the gap between itself and Greece. The difference, in favour of Greece, still exceeds 2 pp, but it is no longer statistically significant (p > 0.05). Of course, the ‘culprit’ behind those events is the electoral victory of the liberal‐conservative New Democracy (ND) and the accompanying shrinkage of the parliamentary representation of SYRIZA; the share of women among the MPs from the former party is equal to 14.5 per cent and the corresponding proportion for the latter one is nearly twice as large (Lefkofridi & Chatzopoulou Reference Lefkofridi and Chatzopoulou2019). It turns out, therefore, that the effects of quotas in Greece are fragile and highly sensitive to the partisan composition of its parliament. Last but not least, female descriptive representation for Greece's non‐quota counterpart improves towards the end of the analysed period. A plausible explanation to this phenomenon is a ‘demonstration effect’ (Gray Reference Gray2003: 62); the respective societies seem to step up to the plate, gradually closing the women's descriptive representation gap even without legal quotas.

Poland

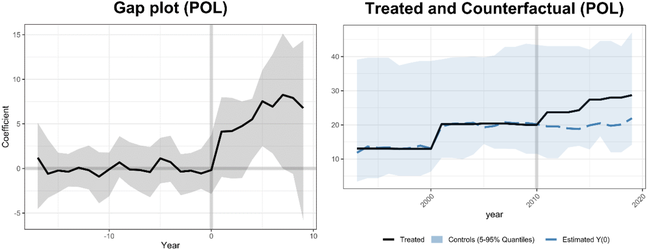

The respective ATT effect for Poland over the 2011–2019 period equals 6.22 pp (p < 0.01). Trends presented in Figure 4 indicate that the pre‐treatment fit between Poland and its synthetic counterfactual is nearly perfect. In 2011, the year the Polish quota law was first implemented, Poland turned out to be 4.14 pp ahead of its counterfactual as regards women's descriptive parliamentary representation. This gap gradually increases to reach the level of approximately 5.51 pp and turns statistically significant (p < 0.01) by 2014. Of course, this is largely due to an increase, by about 4 pp, in the proportion of women in the Polish parliament. Partly, however, it results from a slight decline in female descriptive representation for some countries in the control group and thereby for the synthetic control unit (see right panel). Following the 2015 Poland's election and an associated 3.3 pp increase in the proportion of women in the country's parliament, the treatment effect approaches the level of 8 pp. Curiously, this occurs despite the fact that the 2015 election was won by the socially conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party (Markowski Reference Markowski2016).Footnote 6 Later, the treatment effect drops below 7 pp (in 2016) and again rises (in 2017). The most recent election to the Polish parliament, held in 2019, sees the gap between Poland and its counterfactual having again dropped below 7 pp and become statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). The fact that the gap is still non‐negligible and, at the same time, statistically insignificant stems from the increasing heterogeneity affecting the control group; some of the non‐quota countries (e.g., Latvia) have recently surpassed Poland, some (e.g., Slovakia) are still far behind. Overall, non‐quota countries seem to be closing the gap, albeit it is much less striking here than it was for Greece.

Figure 4. GSC analysis: Poland. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Model diagnostics and robustness checks

In order to boost confidence in our results, we conduct a number of tests. First, it is necessary to check if our results are driven by undesirable extrapolations (Xu Reference Xu2017: 72). This can be examined by looking at band plots in Figures 2–4. The shaded areas represent 5 to 95 per cent quantile bands of the treated and control outcomes, plotted as a reference for checking whether the imputed values are within reasonable intervals and making sure that the estimated counterfactuals do not result from severe extrapolations. The band plots suggest that the estimates for Belgium and Poland are based exclusively on desirable interpolations rather than extrapolations. The results for Greece are somewhat ‘on the verge’ but these are not plagued by severe extrapolations either. An additional robustness test, presented in the Supporting Information Appendix (Figure A3), for which we excluded Malta, indicates that without the latter country extrapolations are more severe. At the same time, substantive results are stable between the two specifications.

Furthermore, models excluding Malta and Sweden (Supporting Information Appendix Figures A2–A4) demonstrate that our results are robust to the exclusion (inclusion) of those two countries. Finally, we also conduct three placebo tests for which we replace a quota country with a non‐quota one. In Supporting Information Appendix Figures A5‐A7, respectively, we replace Belgium with Austria, Greece with Cyprus and, finally, Poland with Slovakia. None of these tests has reproduced the original results. Our findings thus appear to be genuine rather than artefactual.

Discussion

The results presented above point to between‐country heterogeneity of quota effects. The impact of legislated candidate quotas on women's descriptive political representation in Greece and Poland has been limited, while the corresponding effect in Belgium seems to have been truly impressive. Not only did the last country manage to increase the proportion of women MPs from 12 per cent in 1995 (the last pre‐quota election) to over 35 per cent in 2003 but, since then, it has also continued to be far ahead of its synthetic control unit. Why do we observe such heterogeneity? The simplest answer to the question points to the parameters of quotas themselves (Schwindt‐Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2009). The current Belgian quota is simply the most stringent one with respect to both quota size and the presence of placement mandates. Nonetheless, we argue that the design of quota laws is not the sole determinant of the between‐country variation that we observe. Below, we discuss a mixture of other factors which, we believe, contributed to it.

Political culture and elite commitment to the idea of quotas

The core advantage of Belgium over the two other countries is the consociational character of the Belgian polity. This implies the need for adequate representation of various relevant factions of the society, especially ethnolinguistic groups (Meier Reference Meier2012: 372). Consequently, such a setup of the state is accompanied by an ideational milieu that facilitates voicing of the demands for proper representation of further groups, including women.

Notwithstanding the culture of consociationalism, Belgium entered the decade of the 1990s with a proportion of women in its House of Representatives, elected in 1991, being below 10 per cent (Meier Reference Meier and Tremblay2008: 141) and, in fact, slightly lower than for the first Polish parliament of the post‐communist era, elected that same year (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2017: 332). At the same time, the 1991 Belgian ‘Black Sunday election’, marked by a relative success of the radical right Flemish Bloc, forced the establishment parties to treat the issue of gender equality in politics seriously. A ‘window of opportunity’ thus opened for voicing the need for enhancement of women's political representation. These arguments were framed in terms of consociationalism, which greatly magnified their appeal, leaving their opponents with little room for a credible response (Meier Reference Meier2012: 374–375). This apparently resulted in a true commitment to the idea of legislated quotas (and later full parity) on part of significant factions of the political elite. The successful attempt to introduce legislated candidate quotas for elections to the Belgian House of Representatives, having occurred in 1994, was supported by major parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum, including Dutch‐ and French‐speaking Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, as well as the government they then formed. The informal leaders of the pro‐quota coalition were two ministers, one of them male (socialist Louis Tobback) (Meier Reference Meier2012: 364). Moreover, a mutual contagion effect was observed, with parties trying to outbid the state institutions by setting more ambitious voluntary measures, aimed at an improvement of women's descriptive parliamentary representation (Meier Reference Meier2004).

Elite commitment to the idea of implementing measures such as quotas in the unitary states of Greece and Poland has been visibly weaker. Unlike their Belgian counterparts, Greek and Polish political parties were reluctant to introduce their own voluntary gender quotas on party lists in the period preceding the introduction of legal quotas. None of the Greek parties had such measures in place, albeit both the ‘old’ establishment parties, PASOK and ND, applied quotas for party organs (Verge Reference Verge2013: 446). Of major Polish parties, only the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), the landslide winner at the 2001 national election, had its internal gender quota of 30 per cent, applying to all district‐level candidates’ lists (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2015: 683). Likewise, the processes of introducing legislated quotas for national parliament elections in the two countries were marked by elite scepticism, indifference and, at times, hostility. Both the Greek and the Polish legislated candidate quotas have been an outcome of a bottom‐up pressure by women's associations (Anagnostou Reference Anagnostou, Lépinard and Marín2018; Śledzińska‐Simon Reference Śledzińska‐Simon, Lépinard and Marín2018). In Poland, the successful attempt to introduce quotas was coordinated by the Congress of Women, an extra‐parliamentary association assembling female activists from different sides of the ideological spectrum. That attempt had actually been the fifth one since the collapse of state socialism, all the previous (unsuccessful) ones having been initiated by female MPs (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2015: 684–689). In both the countries, the strongest opponents of quota laws were on the right‐of‐centre side of the ideological spectrum (e.g., Dubrow Reference Dubrow2011), the right‐wing Greek and Polish parties not following in the footsteps of Belgian Christian Democrats. The then second largest Polish party, the conservative PiS, voted against the quota law (Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2015: 689). The Greek centre‐right ND eventually supported quotas but, as a ruling party at that time, they enforced a passage of the regulations in a diluted form (see above).

Post‐quota elite commitment and nuances of campaign spending

Smulders et al. (Reference Smulders, Put and Maddens2019: 56) notice that the literal effect of the 1994 Belgian quota law was just to legally sanction the status quo as regards the proportions of women on parties’ lists. And yet, the first election held under the regime of legislated quotas saw an 11.3 pp increase in the proportion of female MPs. Meier (Reference Meier and Tremblay2008: 146) argues that this effect was in no way ‘intrinsic’; the quota seemed to have worked because parties engaged in a sort of competition, trying to outperform rivals in terms of commitment to an enhancement of female descriptive representation. In particular, the initial post‐quota election saw a substantial increase in the proportion of women among the candidates featuring at ‘realistic’ ballot positions (Put & Maddens Reference Put and Maddens2013; Smulders et al. Reference Smulders, Put and Maddens2019: 50). ‘Realistic’ positions are defined as the N+1 top slots on a party's list, N being equal to the number of seats won by the party during the previous election (Smulders et al. Reference Smulders, Put and Maddens2019: 47). Being ranked as ‘realistic’ has important implications for a candidate's campaigning potential because Belgian electoral law allows ‘realistic’ candidates to spend even 10 times more money than others are permitted to. This has an enormous impact on an ‘average’ women candidate's personal vote‐seeking abilities, especially in situations in which female challengers attempt to overcome obstacles stemming from incumbency advantage, enjoyed predominantly by men (Schwindt‐Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2005). Consequently, Smulders et al.’s (Reference Smulders, Put and Maddens2019) analysis indicates that, because of that legal nuance concerning caps on campaign expenditures, the aforementioned quota‐driven parties’ tendency to put women higher on candidates’ lists had a virtually instant positive effect on female candidates’ relative electoral chances.Footnote 7

Regarding the link between opportunities for campaign financing and candidates’ ability to build a personal reputation, a direct systematic comparison of the respective processes occurring in Belgium to those in Poland and Greece is impossible. For example, in Poland, all campaign expenditures have to go through central party budgets and thus figures on spending by individual candidates are not even reported (Górecki & Kukołowicz Reference Górecki and Kukołowicz2014: 71). Anyway, for major parties, the decisions on supporting individual candidates tend to be highly centralised, patronage‐based and dependent on discretionary decisions by party leadership (Szczerbiak Reference Szczerbiak2006; Sokołowski Reference Sokołowski2012). Although the correlation between list placement and female candidates’ electoral success seems to be very high, the strength of the quota‐driven tendency to put women higher on lists varies substantially between parties; parties on the left and the liberal ones tend be relatively generous to female candidates, placing them towards the top of lists more often than it is done by parties on the right (Jankowski & Marcinkiewicz Reference Jankowski and Marcinkiewicz2019). Unlike for Belgium, there is thus no universal contagion effect, nor is there any legal mechanism in place that would accelerate change triggered by such an effect. The Greek mode of campaign financing largely resembles the Polish one (Vernardakis Reference Vernardakis2012). Accordingly, Lisi and Santana‐Pereira (Reference Lisi and Santana‐Pereira2014) find that Greek female candidates’ potential to launch personal campaigns is, on average, substantially weaker than it is for male candidates. Perhaps the differential access to financial resources is used by some Greek (and Polish) parties as a means of resistance against quotas (Krook Reference Krook2016), although, due to the unavailability of adequate data, an evaluation of the extent of this phenomenon is beyond our reach.

Period effects: Global financial crisis and compositional changes

Another crucial aspect of our analyses is the fact that both Greece and Poland started to implement legislated candidate quotas in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, just at the time when the consequences of that breakdown became perceptible to the broader public. This may have suppressed the effects of quotas because at times of security threats, be it caused by violence (Lawless Reference Lawless2004) or economic downturns (Lei & Bodenhausen Reference Lei and Bodenhausen2018), voters tend to be less willing to support female candidates. While in our analysis we control for both a political stability measure and a country's per capita GDP, we acknowledge that the scale of the 2007–2008 crisis and its repercussions were broad enough for some effects to still operate uncontrolled. At the same time, there are good reasons to believe that such effects might have strengthened, rather than suppressed, the apparent quota effects. The reason why it might have been the case for Poland is the fact that the country was coping with the crisis extremely effectively, not having experienced negative GDP growth (Duszczyk Reference Duszczyk2014). Simultaneously, the severe economic difficulties experienced by countries with similar levels of female descriptive political representation, including the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia and Slovakia, were a likely factor contributing to the slight lowering of the outcome for the synthetic control unit and thereby artificially boosting (overestimating) the observed quota effect for Poland.

Greece was obviously one of the countries that suffered most from the global financial crisis but that this suppressed the quota effect is rather doubtful. The first election held under the quota regime saw an increase in the proportion of elected female MPs to 17.3 per cent, from 16.0 per cent at the preceding election. Simultaneously, Greece's counterfactual suffered from a substantial decline in female descriptive representation (see Figure 3 above). Subsequently, growth in female descriptive representation in Greece was fuelled by the expansion of SYRIZA, starting from the 2012 elections. The party's electoral successes were refreshing because its candidate selection processes were guided by the rules of internal party democracy (Kakepaki Reference Kakepaki, Coller, Cordero Garcia and Jaime Castillo2018), thus being radically different from the centralised, patronage‐based and patriarchal routines of the ‘old’ establishment parties (Kapotas Reference Kapotas2010: 36). SYRIZA has always practised internal party democracy but the crisis‐driven substantial growth of its share of parliamentary seats, culminating in 2015, had an effect on the entire Greek political scene. As a result, the ‘crisis cohort’ of MPs was atypical, one aspect of this phenomenon being a larger proportion of women (Kakepaki Reference Kakepaki, Coller, Cordero Garcia and Jaime Castillo2018). Just like with Poland, therefore, the crisis is likely to have actually boosted the apparent effect of quotas in Greece rather than having suppressed it.

Because left‐wing and liberal parties are, on average, more ‘women‐friendly’ than the right‐wing ones, period effects also operate in the form of changes to the ideological composition of parliaments, occurring at election times. Here, again, Belgium enjoys an advantage over Greece and Poland. Due to female MPs being evenly distributed across major parties (Devroe & Wauters Reference Devroe and Wauters2018), the country is fairly immune to such fluctuations. By contrast, the victory of ND at the 2019 Greek election was associated with a decline in female descriptive representation, even despite the increase in quota size from one‐third to 40% (Lefkofridi & Chatzopoulou Reference Lefkofridi and Chatzopoulou2019). In Poland, the 2019 election saw a landslide victory of the conservative PiS, with just 23.8% of female MPs. In addition, 15 seats were won by the radical right Confederation, all of them by male candidates. This has blocked a further increase in female descriptive representation. However, its substantial decrease has been avoided due to the ‘rebirth’ of the left, with its impressive 42.9 per cent of women MPs (Druciarek et al. Reference Druciarek, Przybysz and Przybysz2019: 15). These examples illustrate the sensitivity of women's descriptive representation in Poland and Greece to basic democratic phenomena, such as party‐level electoral volatility.

Values and voter choice

One should also remember that political representation in Poland and Greece may still be strongly affected by voters’ sticking to religion‐induced conservatism and traditionalism, with its ideational division between the ‘male’ public sphere and the ‘female’ private one. Roman Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity prevail in the former country and the latter one, respectively. These religious traditions, typically considered unfavourable to the cause of women's presence in politics (Verge Reference Verge2013: 439), are interwoven with the vivid nationalist traditions of both the countries (Mavrogordatos Reference Mavrogordatos2003; Śledzińska‐Simon Reference Śledzińska‐Simon, Lépinard and Marín2018: 245). (Of course, historically Belgium is a Roman Catholic country just like Poland, but the progress of secularisation has gone very far there; Billiet et al. Reference Billiet, Maddens and Frognier2006)

While evidence with respect to values upheld by citizens of the three countries analysed here is scattered, it is nonetheless suggestive and intriguing. Curiously, Kossowska and van Hiel's (Reference Kossowska and Hiel1999) comparative study of Poland and Belgium indicates that towards the end of the twentieth century citizens of the former country were no more conservative than those of the latter one. Piurko et al.’s (Reference Piurko, Schwartz and Davidov2011) study, based on the European Social Survey large‐sample data collected in 2002 and 2003, nonetheless demonstrates that there is a different political meaning of Belgian conservatism as opposed to that in Greece and Poland. In Belgium, right‐leaning correlates with such aspects of conservatism as desire for security and conformity, but not with upholding traditional values. The last tends to characterise right‐leaning Greeks and Poles (Piurko et al. Reference Piurko, Schwartz and Davidov2011: 551). Furthermore, Caprara et al. (Reference Caprara, Vecchione, Schwartz, Schoen, Bain, Silvester and Baslevent2018) recent comparative study of 16 countries, including Greece and Poland (but not Belgium), points to the relatively high importance of religion from the viewpoint of both Greeks and Poles. At the same time, in both the countries religiosity is accompanied by right‐leaning and, simultaneously, upholding traditional values (Caprara et al. Reference Caprara, Vecchione, Schwartz, Schoen, Bain, Silvester and Baslevent2018: 528–529). All this indicates that voters’ (conservative) preferences may have partially contributed to the weaker quota effects in Greece and Poland.

Conclusion

In this study, we make what we believe is an important empirical contribution to the literature on the effects of legislated candidate quotas on female descriptive representation. We capitalise on the rapid developments in the area of synthetic control methodology (Abadie et al. Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010; Xu Reference Xu2017) and rigorously study the causal impact of such quotas in national parliamentary elections held under preferential voting PR rules; to date, comparably rigorous evidence, encompassing studies of both open‐ and closed‐list PR, has been offered mainly with respect to local elections (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014, Reference Baltrunaite, Casarico, Profeta and Savio2019; Besley et al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017; Bagues & Campa Reference Bagues and Campa2021; albeit see Weeks Reference Weeks2016). Our results fit into the general picture outlined by previous studies of the effects of legislated candidate quotas in preferential voting systems. Most importantly, we demonstrate that such effects are heterogeneous and context‐dependent. The clear‐cut divergence that we observe between Belgium and the other two countries that we study, Greece and Poland, resembles the observations made by Gray (Reference Gray2017) in the course of her qualitative comparison of Brazil and Peru. Interestingly, both our work (see also Weeks Reference Weeks2016) and that of Gray also demonstrate that, under preferential voting rules, strong positive effects of legislated quotas can occur even in the absence of placement mandates. This is a distinctive characteristic of preferential voting systems, observed in the context of Italian local elections (Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014), too. Moreover, our analysis of the broadly conceived context that affects national parliamentary elections in Belgium, Greece and Poland points to factors relevant also beyond the three countries. For example, we argue that legal regulations concerning campaign expenditures are one of the sources of Greece's and Poland's disadvantage in the process of enhancing female descriptive representation. This echoes Hillman's (Reference Hillman2018) observations on the limits to the effectiveness of legal candidate quotas in Indonesia.

Notwithstanding the above, our findings stand somewhat in contrast to certain relevant work, especially Baltrunaite et al.’s (Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014, Reference Baltrunaite, Casarico, Profeta and Savio2019) studies of Italian local elections, demonstrating unequivocally strong effects of candidate quotas. Our account is necessarily more nuanced due to the cross‐country heterogeneity that we observe. Perhaps the source of it lies in the fundamental difference in the way voters perceive female candidates contesting national elections as opposed to local ones (e.g., Huddy & Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). In the national electoral arena, contested by high‐profile (mostly male) politicians, ‘cultivating a personal vote’ (Carey & Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995) may be an exacting task for female challengers. Favourable contextual conditions, such as political elite commitment to the cause of gender equality or secularised electorate (see above), mitigate the effects of the obstacles on the way to female candidates’ electoral success. Such conditions have accompanied quota regulations in Belgium. In Greece and Poland, women's activism, an indispensable trigger of pro‐quota campaigns (Krook Reference Krook2007), does not seem to have been coupled with additional factors facilitating and accelerating quota‐driven change. All in all, further methodologically rigorous studies of these issues are necessary and we hope that the current one will contribute to such future efforts.

Funding

This research was founded by Narodowe Centrum Nauki, PL (grant number 2018/29/B/HS6/00719, awarded to Maciej A. Górecki).

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the seminar of the Centre for Research on Prejudice (Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw) and at various conferences. We are grateful to the participants of all those events for their helpful comments. We also thank four anonymous referees from this journal for their observations on a later draft.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure A1. GSC analysis: Belgium (excluding APM (party magnitude))

Figure A2. GSC analysis: Belgium (excluding Malta)

Figure A3. GSC analysis: Greece (excluding Malta and Sweden)

Figure A4. GSC analysis: Poland (excluding Malta and Sweden)

Figure A5. GSC placebo analysis: Austria

Figure A6. GSC placebo analysis: Cyprus

Figure A7. GSC placebo analysis: Slovakia

Supplementary Materials