Introduction

In the discipline of political science, there is overwhelming evidence that male scholars submit and publish more work than female scholars do (eg., Bosco, Verney, and Bermúdez Reference Bosco, Verney and Bermúdez2023; Breuning, Gross, Feinberg et al., Reference Breuning, Gross, Feinberg, Martinez, Sharma and Ishiyama2018; Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Sokhey2019; Grossman Reference Grossman2020; König and Ropers Reference König and Ropers2018; Samuels and Teele Reference Samuels and Teele2021; Saraceno Reference Saraceno2020; Stockemer, Blair, and Rashkova Reference Stockemer, Blair and Rashkova2020; Stockemer and Sawyer Reference Stockemer and Sawyer2025; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017; Verney and Bosco Reference Verney and Bosco2022). If we randomly select an article in a peer-reviewed political science journal, there is roughly a two-to-one chance that this article is male authored (Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020; Verney and Bosco Reference Verney and Bosco2022). When the percentage of female articles in journals is compared with specific measures of women’s presence in the discipline of political science (eg., through membership in political science associations such as the American Political Science Association or the International Political Science Association), women appear to be individually underrepresented in publishing compared with their presence in the discipline (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), even if these gaps seem to have narrowed recently (Reidy and Stockemer Reference Reidy and Stockemer2024).

In this article we ask: What can journals do to reduce the gender gap in publishing? We hypothesize that one relatively easy ‘fix’ is the nomination of a higher number of female editorial board members. Editorial board members are spokespersons for a journal, they codetermine its direction and new initiatives, and they are important personalities to whom members of the discipline look up to (Hames Reference Hames2001). We believe that, if more women serve on editorial boards, they may serve as role models for other females, can advocate for proactive measures to attract women to submit articles, and can directly promote journals among other female scholars (Nahai Reference Nahai2021). We also believe that attention to ensuring editorial board parity between men and women can foster attentiveness to ensuring more equitable publishing between genders.Footnote 1 Yet, we also test for an intervening variable, as the percentage of female editorial board members is not independent of the percentage of female editors. Rather, female editors might have a higher likelihood of nominating female editorial board members. Thus, we test the relationship between the percentage of women on editorial boards and the percentage of female authors, as well as the interactive effect between the two variables on the share of female authors, using a sample of 120 political science journals (see Appendix). Through quantitative analysis, we find that the percentage of female editorial board members of a journal is associated with the percentage of female authors. We also find that this effect is not independent of the percentage of female editors.

Literature review

Studies looking at the gender gap in research are currently made up of two unrelated literatures. The first and larger literature has two foci. First, it empirically describes the state of gender equality in the discipline of political science. There is strong evidence that the publication world is tilted toward men. Depending on the journal and the subfield, roughly two-thirds of the authors are men (Bosco, Verney, and Bermúdez Reference Bosco, Verney and Bermúdez2023; Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020; Grossman Reference Grossman2020; Stockemer and Sawyer Reference Stockemer and Sawyer2025; Zigerell Reference Zigerell2015). Second, the literature explains the large and persistent gender gap in favor of men. Across the literature, there are several arguments for the lower rate of publications authored by women in political science. These include women’s overrepresentation in qualitative research (Brown, Horiuchi, Htun et al., Reference Brown, Horiuchi, Htun and Samuels2020; Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), which is currently less popular within the discipline; women benefitting less from co-authorship, women being more risk-averse, women accepting lower outcomes when publishing or submitting (Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020; Grossman Reference Grossman2020; Mayer and Rathmann Reference Mayer and Rathmann2018); and women having less time for research because of the academic–domestic work load (Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020). As a result, despite slightly higher article acceptance rates among women, female authors submit fewer articles than male authors, which directly leads to lower female publication rates (Bettecken, Klöckner, Kurch et al., Reference Bettecken, Klöckner, Kurch and Schneider2022; Closa, Moury, Novakova et al., Reference Closa, Moury, Novakova, Qvortrup and Ribeiro2020; Saraceno Reference Saraceno2020; Stockemer, Blair, and Rashkova Reference Stockemer, Blair and Rashkova2020).

There is a second, albeit smaller, literature that looks at women’s presence on journals’ editorial boards. This research mainly focuses on the hard sciences and starts with the premise that editorial board members are ‘leading scientists who have obtained scientific recognition within the scientific community’ (Mauleón, Hillán, Moreno et al., Reference Mauleón, Hillán, Moreno, Gomez and Bordons2013: 87). From this premise, the literature then deducts that the prestige of editorial board membership is an important signifier of women’s representation and consideration in research (Metz and Harzing Reference Metz and Harzing2012: 293). Most of the existing empirical studies focus on the number of women versus men on editorial boards (eg., Amrein, Langmann, Fahrleitner-Pammer et al., Reference Amrein, Langmann, Fahrleitner-Pammer, Pieber and Zollner-Schwetz2011; Hamidi, Rezaei-Pandari, Fakheran et al., Reference Hamidi, Rezaei-Pandari, Fakheran and Furst2022; Morton and Sonnad Reference Morton and Sonnad2007; Shah, Shumway, Sarvis et al., Reference Shah, Shumway, Sarvis, Sena, Voice, Mumtaz and Sheikh2022). The conclusion this literature reaches is that male scholars are overrepresented on these boards. Goyanes, de-Marcos, Demeter et al., (Reference Goyanes, de-Marcos, Demeter, Toth and Jorda2022) nicely summarize this finding, illustrating that across various disciplines, the prototypical editorial board member is ‘a male scholar from an elite American university who participates in many different journals’ (18) (see also Mauleón, Hillán, Moreno et al., Reference Mauleón, Hillán, Moreno, Gomez and Bordons2013). Some studies within this literature report a positive relationship between the percentage of women on editorial boards and the percentage of female authors. For example, Amrein, Langmann, Fahrleitner-Pammer et al., (Reference Amrein, Langmann, Fahrleitner-Pammer, Pieber and Zollner-Schwetz2011) argue that, ‘if more women are nominated to serve on editorial boards, they will be a visible sign of continuing progress and serve as important role models for young women contemplating a career in academic medicine’ (378). In another study, Metz, Harzing, and Zyphur (Reference Metz, Harzing and Zyphur2016) suggest that ‘one by-product of having higher levels of gender equality in editorial boards might be more submissions from a wider section of the academic community and increased readership’ (720) (see also Metz and Harzing Reference Metz and Harzing2012). Finally, Dai, Li, Ren et al., (Reference Dai, Li, Ren and Bu2022) argue that ‘gender imparity on editorial boards is partially to blame for the paucity of women on the authorship and leadership positions’ (4).

In this article, we aim to establish the link between women’s presence on editorial boards and their presence in political science journals. We hypothesize that a higher presence of female editorial board members triggers a higher share of female authors. As potential mechanisms, we suggest that there might be a direct relationship between women on editorial boards, who serve as spokespersons of the journal and can propel the journal’s quality through its editorial choices. More indirectly, gender-balanced editorial boards might suggest greater attentiveness to gender parity as well as send a signal to authors that the journal values gender equality and supports female authors. In addition, we believe that the percentage of female editorial board members is not independent of the gender composition of the editors of a journal. Frequently, editors are the ones who nominate editorial board members. In the words of Stegmaier, Palmer, and Van Assendelft (Reference Stegmaier, Palmer and Van Assendelft2011), it seems likely that, on average, male editors will reach out to more men, and female editors will reach out to more women to fill editorial positions. It is also the editors who are mainly responsible for designing editorial strategies. If it is their strategy to promote gender equality, it should also be their strategy to balance the editorial board. Hence, the percentage of editorial board members should depend on the composition and strategies of editors.

From a practical perspective, we believe that testing the link between women’s representation on journal editorial boards, their interactive relationship with the percentage of female editors, and their presence as authors should be of interest to national and international political science associations. Many association journals nominate balanced editorial teams and have created gender-balanced editorial boards (eg., the editorial board of the International Political Science Review, the flagship journal of International Political Science Association, consists of 57% female scholars as of 2025). It will be interesting to see whether these initiatives might also have the potential to increase the number of authors in a journal.

Data and methods

To test the relationship between the percentage of female editorial board members, the percentage of female editors, and the percentage of female authors published in that journal, we use data from the International Political Science Abstracts, Footnote 2 which compiles abstracts of articles from major political science journals across the field of political science. The Abstracts provides a complete list of articles from 120 political science journals and selects thousands of articles from multidisciplinary journals related to political science. For this article, we used the 120 journals with all articles as the baseline. The Abstract’s editorial office compiles the gender for all authors in a separate database.Footnote 3 We used the data from 2022 to compile the percentage of female authors by journal. We calculate this number by dividing the number of female authors in 2022 by the number of male authors. The independent variable is the percentage of female editorial board members per journal. We hand-collected this variable from each journal’s editorial board listing. In some cases where we could not clearly identify from the name whether the editorial board member was a man or a woman, we tried to find a picture of the person to identify the sex. To do so, we first tried to locate the personal website of the authors and looked at the picture displayed there. In the few instances where such websites were not available or did not display a picture, we tried to locate the Google Scholar page of the respective scholar. If this was not available either (which brought our missing data down to a handful of cases), we engaged in a broader Google search. Recent literature has used a similar procedure to identify the sex of editorial board members (Hamidi, Rezaei-Pandari, Fakheran et al., Reference Hamidi, Rezaei-Pandari, Fakheran and Furst2022; Shah, Shumway, Sarvis et al., Reference Shah, Shumway, Sarvis, Sena, Voice, Mumtaz and Sheikh2022). Our moderating variable is the percentage of female editors (hand-coded from journal websites) for each of these 120 journals.

To display/test for the link between the percentage of female editorial board members and the percentage of female editors, as well as the moderating relationship between female editors and board members, we use four types of analyses. First, we display some univariate statistics on the distribution of female editorial board members, female editors, and female authors. Second, we graph the relationship between the percentage of female editorial board members, female editors, and female authors. Third, we test the link between indicators and female authorship with a multiple regression analysis (ie., ordinary least square [OLS] regression). Fourth, we add an interaction term between the percentage of female editors and editorial board members to the equation.

In the multivariate analyses, we control for several predictors which could also influence the percentage of female authors in a journal. One of these variables is authorship type (ie., the percentage of single-authored articles). Because of women’s potential underrepresentation in co-authored and multiauthored articles (Samuels Reference Samuels2018; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), we expect women to be more highly represented in journals with more single-authored articles. To control for the possibility that women are underrepresented in top-tier journals, we add a categorical coding for journal ranking using the tier 1, 2, 3, and 4 classifications in the Clarivate Citation Index.Footnote 4 In addition, we distinguish between five subfields (ie., generalist political science journals, international relations, comparative politics, political theory, and others) and expect women to be the least highly represented in male-dominant subfields such as political theory (Bryson Reference Bryson2016). Finally, we control for the country the journal is published in (distinguishing three categories, the USA, the UK, and other countries).

Results

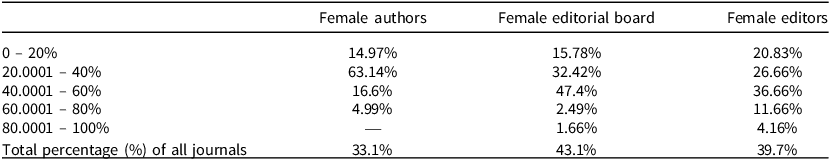

As presented in Table 1, there is some wide variation in our three variables of interest in our sample of 120 studies. Our dependent variable, female authorship, which averages 33% in our sample, ranges from less than 10% female authors for journals such as Politics, Religion & Ideology or History of Political Thought to 65% or above for journals such as Politics & Gender as well as the International Feminist Journal of Politics. When it comes to our independent variable, female editorial board membership, the average percentage of female editorial board members is 43%. Interestingly, the range is over 90% (with some journals such as the Journal of Chinese Governance having zero female editorial board members, whereas others have 90% or above female representation (ie., the two abovementioned gender journals Politics & Gender and the International Feminist Journal of Politics). For our last variable of interest, the percentage of editors, we find all female teams as well as all male teams and mixed teams. The average percentage of female editors in the dataset is approximately 40%.

Table 1. The percentage of female authors, editors, and editorial board members

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the percentage of female editorial board members and female editors and the percentage of female authors, respectively. The first graph displays a rather strong positive relationship between the percentage of female editorial board members in a journal and the percentage of female authors in that journal. The fitted line in graph 1 predicts that a 1-point increase in the percentage of female editorial board members triggers a nearly 0.5-point increase in the number of female authors. If we look at the second indicator, the percentage of female editors and its relationship with female authorship, we find a much weaker association. The fitted line in graph 2 only predicts a roughly 0.35-point increase in the percentage of female authors for every 1 point the percentage of editors increases. As expected, we also find that the percentage of female editorial board members is not independent from the percentage of female editors. In fact, the Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.52 (p < 0.000), which displays a relatively strong covariation.

Figure 1. The link between female editorial board membership/female editorship and female authorship.

Figure 2 graphically shows the association between the percentage of female editorial board members and the percentage of female authors based on different percentages of female editors (0 – 19.99% in the first graph, 20 – 39.99% in the second graph, 40 – 59.99%, 60 – 79.99%, and 80 – 100%). The five graphs display that the association between female editorial board members and female authors is strongest for 80 – 100% female editors and weakest for 0 – 19.99% female editors. Hence, Figure 2 shows that the percentage of female editors and the percentage of female authors are not independent of each other.

Figure 2. The link between female editorial board membership and female authorship for journals with less than 20% female editors, 20 – 40% female editors, 40 – 60% female editors, 60 – 80 % female editors, and over 80% female editors.

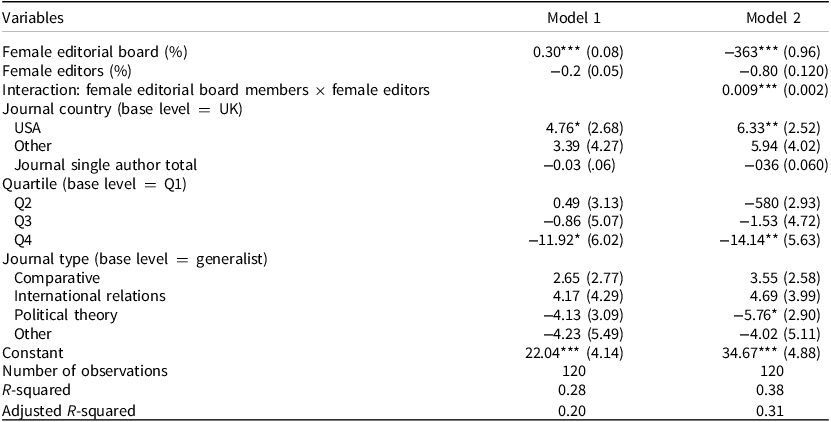

The multiple regression model in Table 2 confirms this moderating relationship. If we add both variables – the percentage of female editorial board members and the percentage of female editors – Model 1 displays a statistically significant and positive influence on the percentage of female authors of the former variable and no statistically significant effect of the latter one. However, if we include the interaction term between the two variables, we get a statistically significant interaction (Model 2). Figure 3 graphically shows this interaction. Confirming Figure 2, the graph illustrates that the percentage of female editorial board membership becomes more relevant the higher the share of female editors. When it comes to the control variables, we only find two marginally significant control variables. It seems from Table 1 that the percentage of female authors is slightly higher in US-based journals and that women publish less in the least prestigious journals (ie., quartile [Q] 4 journals). This latter finding indirectly confirms the thesis that articles authored by women are potentially of higher quality (Stockemer, Blair, and Rashkova Reference Stockemer, Blair and Rashkova2020; Tudor and Yashar Reference Tudor and Yashar2018).

Table 2. OLS regression model measuring the effect of various independent variables on the percentage of female authors in political science journals

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Significance: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Figure 3. The interactive link between female editorship and female editorial board membership on female authorship in a journal.

Discussion and conclusions

According to Goyanes, de-Marcos, Demeter et al., (Reference Goyanes, de-Marcos, Demeter, Toth and Jorda2022: 18), editorial boards are elite clubs. Joining such a club is a sign of recognition and allows diverse members to help shape the future of a discipline. Among others, editorial board members might have a say on the types of articles a journal publishes, the preferred methodological perspectives, and the favored theoretical approaches. Therefore, female editorial board members may be able to prioritize certain methodologies (ie., qualitative methods) and approaches (eg., feminism) that are favored by women scholars. They may also push for gender-friendly policies, such as a requirement to submit gender-balanced special issue proposals. In addition, female editorial board members may serve as role models for other women. A potential author might be encouraged to submit if she sees more women publishing in the journal (Stegmaier, Palmer, and Van Assendelft Reference Stegmaier, Palmer and Van Assendelft2011). More directly, more female scholars on a board could also encourage other women to submit.

Yet, the percentage of female editorial board members is not independent of the percentage of female editors. Rather, a high share of female editors seems to be an important condition for the nomination of female editorial board members (ie., the correlation between these two indicators is above 0.5). Hence, it seems that not only do female editors foster the nomination of female editorial board members but they also work in tandem with the (female) editorial board to potentially render journals more women friendly or at least demonstrate attentiveness to gender parity within their journal more broadly. Therefore, the policy recommendation that emanates from this article is to nominate more women to editorial boards, as well as editorial positions. We still live in a (publishing) world tilted toward men. Men submit more articles and they see more articles in print. More women in editorial roles, as editors and editorial board members, can reduce this dominance and could potentially contribute to a more equal gendered playing field.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request.

Funding statement

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Canada.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and informed consent statements

None.

Appendix I. Table showing the percentage of female authors, female editors, and female editorial board members for each journal in the sample