A. Introduction

“Vidya dadati vinayam” is an ancient Sanskrit phrase meaning knowledge leads to happiness.

India is an important piece in the global climate puzzle. It houses close to twenty percent of the world’s population, 2.4% of the world’s land area, 7%–8% of all recorded species, including over 45,000 species of plants and 91,000 species of animals.Footnote 1 Over 650 million Indian people depend on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture and forestry for their livelihood. The minimum and maximum temperatures are projected to increase by two to four degrees Celsius during the 2050s in the northern part of the country and by over four degrees Celsius in the southern part of the country.Footnote 2 A significant responsibility of the fate of India—as indeed the fate of the planet—rests on how the Indian Judiciary deals with the increasing climate change related cases. It has, in the past, deemed it necessary to fill the vacuum of law through well-thought-out decisions, forcing the Legislature to act.Footnote 3

The recent global trend in climate change litigation, in cases discussed below, cannot be seen solely from the point of view of plaintiffs and defendants. Litigation such as the one in Urgenda Foundation v. The Netherlands Footnote 4 leads to sensitization of governments, citizens, and the private sector alike towards the threats of climate change, often beyond the result of the particular case. In doing so, such strategic climate litigation creates awareness and knowledge capital in terms of causal nexus among actions and their environmental consequences, with the aim of producing policy or social change with respect to the issue.Footnote 5 The defining features of strategic litigation, as opposed to traditional litigation, aim to advance legal change with an effect applicable beyond a single case and extend over many available legal dispute resolution instances.Footnote 6

Such litigation has ripple effects across national boundaries due to the global interests involved, often building on each other.Footnote 7 For example, building on Urgenda, the NGO Milieudefensie successfully launched a lawsuit against Royal Dutch Shell in the Dutch courts. The court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to reduce its global carbon emissions from its 2019 levels by forty-five percent by 2030.Footnote 8 The objective of such litigation is to create awareness, encouraging public debate, or sparking policy change.Footnote 9 The framework of how information travels across borders has changed as the digital world expands and the global societies amalgamate into one network of socially connected peers throughout the globe. From such discourse, either on the substance or outcome of litigation, knowledge transpires through borders, both human and state, culminating into climate action. Vidya Dadati Vinayam.

This article tracks the progress of the Indian judicial system through the history of environmental litigation. It explores the role played by judicial activism in shaping principles of environmental law that were not legislated upon specifically. In doing so, it also delves into the aspects that led the Judiciary to be active. The National Green Tribunal of India serves as an example of this modus, which is substantially covered hereunder. In addition, the judicial principles inculcated within the domestic legal systems have leaned on international legal principles of environmental law and benefitted from the expansion of the concepts of ‘standing.’ Finally, this article further discusses some important cases that shed light on the changing dynamics of climate litigation in India, finally discussing the not-ideal outcome of the youth led climate litigation, up till now.

B. The Indian Context: Impetus Through Judicial Activism

Various factors have helped litigations across the globe reaching a climate-favorable goal, none larger than those of the present international climate change regime, under the Paris Climate Agreement,Footnote 10 implementing Nationally Determined Contributions and mandatory updating.Footnote 11 Climate litigation has also benefitted from a better equipped judiciary to handle specific environmental cases, with environmental law being seen as a discipline that requires specialization and uniformity, both at bar and the bench.Footnote 12

India, in this sense has been treading a path of empathy towards citizenry at large, and activism towards legal issues discountenanced by the Legislature, by the Judiciary, for long. The country has a long history of public interest litigation which has included landmark climate change litigation cases.Footnote 13 It has more relaxed standing rules—such as the public interest litigation dealt with below—and the Judiciary is a dynamic, interventionist actor which can grant itself a continuing mandate to monitor the implementation of their decisions.Footnote 14

“Of course, new legislation is the best solution, but when lawmakers take for too long for social patience to suffer, as in this very case of prison reform, courts have to make-do with interpretation and carve on wood and sculpt on stone ready at hand and not wait for far away marble architecture” opined Justice Krishna Iyer of the Supreme Court of India in 1978.Footnote 15 The need for an activist judiciary thus emanated from social wants.Footnote 16 The shift to address social wants of the populace would only be actualized by addressing wants of all the citizens of the country. In India’s case, this was close to half a billion citizens in 1970. This posed a challenge—how does a judicial system address the wants of all when a part of the denizens were devoid of fair access to justice? The answer necessitated judicial creativity, which came in the form of a shift from the traditional meaning of locus standi to include public interest litigation, making the judicial process more accessible, participatory, and democratic. The traditional paradigm of judicial process meant private law adjudication was replaced by a new paradigm that was polycentric and even legislative. While under the traditional paradigm, a judicial decision was binding on the parties—res judicata—and was binding in personam, the judicial decision under public interest litigation bound not only the parties to the litigation but all those similarly situated.Footnote 17

The Public Interest Litigation thus paved the way for the Courts to address a multitude of social wants, often accentuated by lack of political will to act on certain issues, or delay in the political economy to take substantive measures on those. The Indian Judiciary, through creative pronouncements,Footnote 18 took a more activist approach towards redressal of issues placed before it.Footnote 19

Specifically in relation to environment, the Indian Judiciary has been empathetic towards environment, and visionary in its employment of legal principles, both domestic and international, detailed below, to serve the cause of environmental justice. For instance, it declared the right to healthy environment as a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution,Footnote 20 directed several private sector organizations to take necessary measures to protect the environment and reduce the pollution,Footnote 21 and ruled against direct and indirect harm caused by pollution to monuments, heritage buildings, and rivers.Footnote 22 In fact, the Supreme Court of India, in Intellectuals Forum, Tirupathi v. State of A.P. & Others, (2006) 3 SCC 549, while referring to the importance of sustainable development, and rights of the future generations, held as follows:

The world has reached a level of growth in the 21st century as never before envisaged. While the crisis of economic growth is still on, the key question which often arises and the courts are asked to adjudicate upon is whether economic growth can supersede the concern for environmental protection and whether sustainable development which can be achieved only by way of protecting the environment and conserving the natural resources for the benefit of humanity and future generations could be ignored in the garb of economic growth or compelling human necessity. The growth and development process are terms without any content, without an inkling as to the substance of their end results. This inevitably leads us to the conception of growth and development, which sustains from one generation to the next in order to secure “our common future.” In pursuit of development, focus has to be on sustainability of development, and policies towards that end have to be earnestly formulated and sincerely observed. As Prof. Weiss puts it, “conservation, however, always takes a back seat in times of economic stress.” It is now an accepted social principle that all human beings have a fundamental right to a healthy environment, commensurate with their wellbeing, coupled with a corresponding duty of ensuring that resources are conserved and preserved in such a way that present and future generations are aware of them equally.

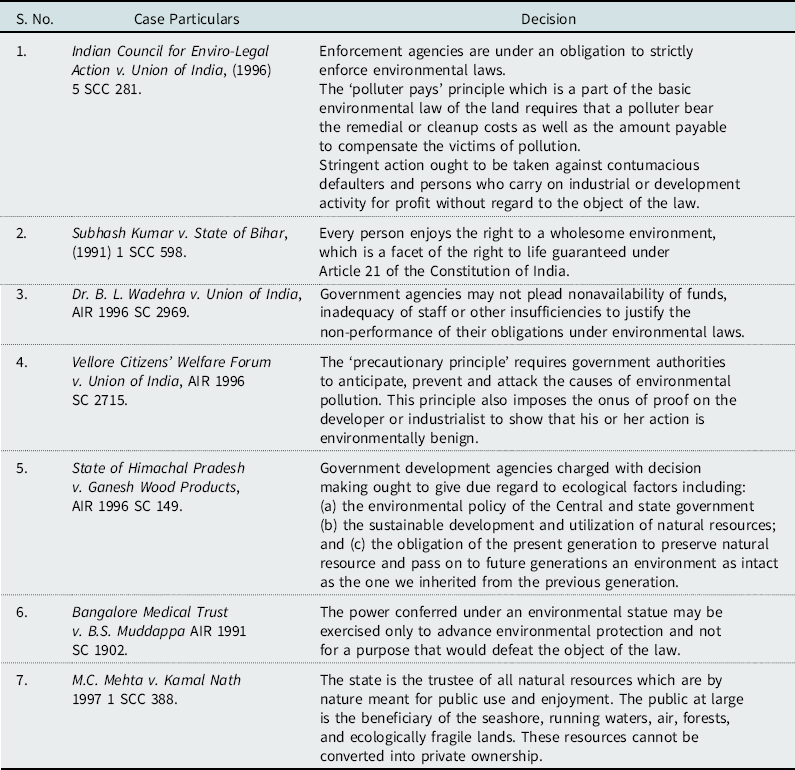

Over the years, the Supreme Court of India has further expanded the scope of various principles of environmental law, some of which are detailed in the table below:

I. Contextualizing the Indian Judicial System

Judicial activism, especially in the case of environmental laws, cannot be on account of an individual reason, or the changing times alone. India serves as an example of culmination of different factors and actors, such as a comprehensive constitution, separation of powers amongst the Legislature, Executive and the Judiciary, faith of the population in democratic institutions, innovative judges and the rule of law, a dedicated environmental judicial system in the form of the National Green Tribunal (the Green Tribunal), coming together to catalyze activism by the Judiciary.

The Supreme Court has been designated as the guardian of the fundamental rights of the citizens and while playing that role, the Supreme Court often indulges in legitimate judicial legislation and judicial governance, together termed as judicial activism. The skeletal concept of Separation of Powers thus lends itself the flesh and blood through the necessary checks and balances required for upkeeping citizens’ rights, and indeed the Indian polity. Article 50 of the Indian Constitution, in no uncertain terms, mandates the separation of the Judiciary from the Executive. Separation of powers is an essential bedrock of any democracy, saving absolute power from being vested in a particular function or functionary in the governance system. India has benefitted from a strong constitution that has earmarked, through specific articles, the specific roles which each branch of the Government has to play in the working of the Indian state. This includes Article 13 of the Constitution of India which implicitly bestows the Supreme Court of India with the power to test each legislative action on the cornerstone of Fundamental Rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution of the country. One such fundamental right, as detailed above, is the right of every citizen to a clean and decent environment. Under Article 32 violation of a citizen’s fundamental rights can be redressed directly by the Supreme Court. Furthermore, Article 142 of the Constitution allows the Supreme Court to pass any order necessary for doing complete justice in any cause or matter pending before it.Footnote 23

Separation of powers, in itself, would hardly serve the purpose of the citizens’ rights, and social wants, if not for the strong democratic institutions India has been granted through the Constitution. Parliamentary democracy, bicameral legislature, a strong executive, and effective elections have all played a part in the strength derived by the democratic structure. India’s existing institutions like the Parliament, various Government departments and their manifestations at the municipal, state and federal level, independent regulators, Supreme Court and High Courts, and legal systems have all evolved in the spirit of the Constitution. At the center of such strong democratic institutions is the need to create access and information for participatory citizenship while maintaining trust in the functioning of the state. Similarly, each of the institutions acts as a custodian of constitutional and democratic values that prevents concentration of power with a specific arm of the Government while providing continuity and stability to democratic functioning.

In India’s specific case, one could argue that the Judiciary was constrained to step into the realm of activism, and indeed judicial governance and legislation, due to the political situation leading into the early 1970s. It was the lack of strength, at that time, of the democratic institutions detailed above, that lead the fabric of democracy to wither, with state-imposed emergency tarnishing the spirit of constitutionalism. In fact, it was during this strangling emergency that a five-judge bench of the court decided by a four to one majority that habeas corpus rights had been entirely suspended by the emergency and that even a mala fide detention order could not be challenged before the courts.Footnote 24 The infamy of the decision and the awakening in the aftermath of the emergency breathed new life in the Judiciary. The rise in the judicial power and intervention followed the reconfiguration of Indian political life in the reverberations of the Emergency of 1975–77. Almost four decades later, the Indian Judiciary has transformed itself into a catalyst of social change, often catering to the international standards set, specifically within enviro-legal developments, detailed below.

II. Role of the National Green Tribunal

During the 1970s, few specialized Environmental Courts and Tribunals were established across Europe. By 2016, the number of Environmental Courts and Tribunals increased over one thousand two hundred across the world.Footnote 25 While the viability of having green courts with dedicated environmental jurisdiction separate from the general judicial system was being contemplated the world over, the parliament of India passed the National Green Tribunal Act of 2010 (NGT Act).Footnote 26

The green tribunal is set up “for the effective and expeditious disposal of cases relating to environmental protection and conservation of forests and other natural resources.”Footnote 27 The benches of the green tribunal comprise not only of judges but also of expert members to provide legal and scientific analysis to issues that arise before it. Over the past decade of its running, the green tribunal has successfully brought environmental concerns of the Indian citizens front and center in the judicial and legal fraternity. Despite challenges in relation to its limited jurisdiction, powers of execution, and statutory limitation,Footnote 28 the green tribunal has succeeded in reducing the procedural complexities in relation to legal issues relating to environment while delivering exceptional environmental jurisprudence, often taking from, and building on international environmental law principles.

C. The Road to Climate Change Litigation

I. Employment of International Environmental Law

Indian Judicial decisions have long used international law and decisions as having persuasive value. Public trust doctrine, the polluter pays principle, precautionary principle and intergenerational equity have all been formed a part of the law of the land through consistent decisions of the Supreme Court strengthening the environmental legal framework of the country. The green tribunal has, in recent years, taken the mantle of further expanding this jurisprudence by assimilating novel concepts of international environmental law in domestic jurisprudence. Case in point being the Judgment of the green tribunal in the matter of Society for Protection of Environment & Biodiversity v. Union of India,Footnote 29 where a federal government notification exempting building and construction projects up to 150,000 square meters from the purview of environmental law was in challenge. The applicant prayed that the notification issued by the Indian Ministry for Environment, Forests and Climate Change dated December 9, 2016, be quashed and set aside on the ground that it diluted and rendered otiose the substantive provisions of Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006 and even that of Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, the umbrella environmental legislation of India. The provisions of the notification, if implemented, it was suggested, would potentially destroy the environment and ecology due to unregulated building and construction activities and would have disastrous effects on environment, causing irreversible damage to the environment. It was also submitted by the applicant that the notification, if given effect to as framed, would result in wiping out the effect of environmental laws in force and hence would not be in consonance with the doctrine of non-regression.

Importantly, the doctrine of non-regression does not form part of Indian law. None of the enactments, especially within the environmental law domain, authorize or mandate, the courts to apply the doctrine of non-regression in its decisions. The doctrine, under international law, is founded on the idea that environmental law should not be modified to the detriment of environmental protection. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), “the principle of non-regression is an international law principle … requiring that norms which have already been adopted by states not be revised if this implies going backward on the subject of standards of protection.”Footnote 30

In the context of International environmental law, “States, sub-national entities, and regional integration organisations shall not allow or pursue actions that have the net effect of diminishing the legal protection of the environment or of access to environmental justice.”Footnote 31

This principle, according to the pleadings submitted before the green tribunal in the case, needed to be brought into play because today’s environmental law is facing a number of threats such as deregulation, a movement to simplify and at the same time diminish, environmental legislation perceived as too complex and an economic climate which favors development at the expense of protection of environment.

Upon a detailed analysis of the facts and laws, the green tribunal finally stayed the notification till conditions, specifically in relation to consents anent the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution), Act, 1974 and Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution), Act, 1981, were fulfilled. It relied upon the doctrine of severability to declare some of the provisions of the notification as ultra-vires or ineffective while holding the other part of the notification as legally sound and sustainable. In doing so, interestingly, the judgment also stated the following:

[S]ome other provisions of the same Notification ex facie suffer from legal infirmities and are incapable of being implemented in accordance with the scheme of federal structure under the Constitution of India. Out of them, some provisions are directly opposed to the Principle of Non-regression as they considerably dilute the existing environmental laws and standards to the prejudice of the environment.

This observation of the green tribunal lends insight into the recent application of principles of international law within the Indian environmental jurisprudence.

II. Expansion of Access to Environmental Justice

Beyond the creativity in application of international law principles, the green tribunal, unlike the Constitutional Courts, the Supreme Court and the High Courts, is a creature of a Statute. It is thus limited by the provisions of its parent act, for example the NGT Act. This poses an inherent dichotomy vis-à-vis access to the green tribunal. While the Supreme Court and the High Courts of India have the luxury of expanded scope of standi under the Public Interest Litigation, the green tribunal, not being a Constitutional Court, does not. Section 14 of the NGT Act states: “the Tribunal shall have the jurisdiction over all civil cases where a substantial question relating to environment (including enforcement of any legal right relating to environment), is involved and such question arises out of the implementation of the enactments specified in Schedule I.”Footnote 32 The enactments in Schedule I include: Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1974; the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Cess Act 1977; the Forests (Conservation) Act 1980; the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1981; the Environment (Protection) Act 1986; the Public Liability Insurance Act 1981; and the Biological Diversity Act 2002. Similarly, Section 16 of the NGT Act lists instances of Government orders against which an aggrieved person can move the green tribunal.

In Samir Mehta v. Union of India,Footnote 33 in paragraphs 31 and 32, the green tribunal on the question of who could approach it, decided as follows:

An “aggrieved person” is to be given a liberal interpretation … it is an inclusive but not exhaustive definition and includes an individual, even a juridical person in any form. Environment is not a subject which is person oriented but is society centric. The impact of environment is normally felt by a larger section of the society. Whenever environment is diluted or eroded the results are not person specific. There could be cases where a person had not suffered personal injury or may not be even aggrieved personally because he may be staying at some distance from the place of occurrence or where the environmental disaster has occurred and/or the places of accident. To say that he could not bring an action, in the larger public interest and for the protection of the environment, ecology and for restitution or for remedial measures that should be taken, would be an argument without substance. At best, the person has to show that he is directly or indirectly concerned with adverse environmental impacts. The construction that will help in achieving the cause of the Act should be accepted and not the one which would result in deprivation of rights created under the statute.

Similarly, in Samata v. Union of India,Footnote 34 the green tribunal relaxed the concept of locus standi to allow a wider base of people to approach it with regard to environmental concerns. It was found that in the relevant provisions the term ‘aggrieved persons’ would include not just any person who is likely to be affected, but also an association of persons likely to be affected by such an order and functioning in the field of environment.

Despite such expanded paradigm of access and the wide connotation to the term “person aggrieved,” in recent times, the scope of access to approach the green tribunal has been seen to be diminishing.Footnote 35

D. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

India presents itself as a curious case in the development of climate change litigation. On the one hand, the country is replete with instances of large strides towards development of environmental jurisprudence, which through the doctrine of precedents, becomes the law of the land. On the other hand, as is discussed below, the specific and most prominence instance of youth-led climate litigation was met with an unsuccessful mandate in the court.

I. Innovation in Climate Change Jurisprudence

The latter half of Section 14 of the NGT Act, referred above, which states that the issues over which the green tribunal can exercise jurisdiction must arise “out of the implementation of” limited enactments poses a bigger adjudicatory challenge.

Noticeably, India does not have a specific legislation on climate change. While several laws address different aspects of climate change, in particular, causes and impacts, and thus provide potential hooks for climate litigation, there is no comprehensive legislation on climate change in India.Footnote 36

It does have a National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) adopted on June 30, 2008 in addition to India’s Intended Nationally Determined Commitments (INDC) submitted to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in October 2, 2015. The NAPCC has an essentially domestic focus. The INDC is a statement of intent on Climate Change action announced in the run up to the Paris Climate Change summit held in December the same year.Footnote 37

However, due to the non-enforceability of the two, the citizenry substantively does not have a specific legal provision to resort to for agitation for their rights against climate change. In Gaurav Kumar Bansal v. Union of India & Others,Footnote 38 the applicant prayed for steps to be undertaken to implement the National Action Plan on Climate Change, and that State governments should finalize and implement the State Action Plans and be restrained from violating them.

This being the case, the judiciary is constrained to innovate dicta that falls within the legal provisions of environmental law, to deal with the challenges that causation and consequences of climate change pose. In its final order, the green tribunal did not directly rule on its jurisdiction over the implementation of the NAPCC but held that in future, specific cases regarding violation of the NAPCC, its impact, or consequences could be filed before it, further adding to the confusion. Additionally, the tribunal directed states that had yet to draft their state action plans in accordance with the NAPCC to prepare them and get them approved expeditiously by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.Footnote 39

In Court on Its Own Motion v. State of Himachal Pradesh and Others, Footnote 40 the Green Tribunal was faced with the challenge of dealing with the impacts of climate change on the glacier of Rohtang Pass in the Himalayas, facing serious pollution issues and with the passage of time, being degraded environmentally, ecologically, and aesthetically.Footnote 41 The challenge, however, remained that no law in India regulates climate change, or its adaptation and mitigation. In the face of this challenge, the green tribunal realized an innovative approach to tackle the issues of glacial pollution—and recession—through various indicators of air pollution laws which, in fact, were within the ambit of its jurisdiction. The Tribunal noticed as follows:

The impacts of vehicular pollution would seriously affect the ambient air quality due to the emission of high carbon content, Black Carbon, nitrogen oxide (NOx) and Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM). All these are polluting the clean and healthy air in that area. Vehicular pollution also adversely affects the glacier, effects of which are evident in blackening of snow, melting of glacier and other ecological disturbances in the glacier. The diesel, commercial and transport vehicles, which are over-loaded and even other vehicles—public and private—including two-wheelers which go to the glacier or pass through the glacier en route to further destinations, are damaging the glacier.

Subsequently, the green tribunal directed the state government to adopt measures that include contribution on the polluter pays principle, effectively banning the plying of heavy vehicles in the region and charging a fee from other private and public vehicles. The amount so collected is to be used for prevention and control of pollution, development of ecologically friendly market at Marhi, restoring the vegetative cover and afforestation.

The above case is an example of how the Indian Judiciary has been able to tackle climate change issues, such as glacial recession, through the established environmental law principles. Still, petitions seeking direct intervention of the green tribunal, or the Supreme Court, have not always been as successful.

Carbon footprint, being one of the core principles of climate change, was peripherally argued before the Supreme Court of India in Tanaji Balasaheb Gambhire v. Union of India.Footnote 42 The applicant sought directions against M/s. Goel Ganga Developers India Private Limited, who were alleged to have illegally constructed a commercial and residential complex. The Court of Original Jurisdiction ruled in favor of the applicant and in review, after calculating the damages in terms of carbon footprint as amounting to INR 190 crores, approximately USD twenty million, developers were directed to pay Rs. 190 crores or five percent of the total cost of the project, whichever is more.

On appeal, with regard to the question of assessment on damages on basis of carbon footprint, the Supreme Court of India observed that the courts cannot introduce a new concept of assessing and levying damages unless expert evidence in this behalf is led or there is some well-established principle. It added that this evidence, carbon footprint, is used to compensate and impose damages on nations but the court cannot apply the method while imposing damages on persons who violate Environment Clearance, and this method is not part of any law, rule, or executive instructions. This way the Court, while rejecting the inflation of damages on account of carbon footprint, left the door ajar for it to be a consideration in future cases through scientifically led evidence.

II. Youth-Led Climate Litigation

In 2015, young plaintiffs in the United States of America, represented by the non-profit law firm Our Children’s Trust filed a constitutional climate lawsuit, Juliana v. United States,Footnote 43 in which they alleged that the American government’s actions have caused climate change, violating their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property, breaching the public trust doctrine. Similarly, in September 2020, Global Legal Action Network filed the first ever climate change case to be brought before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) on behalf of six young people from Portugal against 33 member states of the Council of Europe.Footnote 44

India saw a similar youth led litigation come to the NGT. In 2017, a nine-year-old, Ridhima Pandey, moved the green tribunal raising serious concerns regarding the actions and inaction of the government on the issues of climate change, on similar lines as the arguments raised in the Juliana case.Footnote 45 She submitted that she was directly affected by the adverse impacts of climate change and rising global temperatures. Taking recourse to the intergenerational equity-based argument, it was also suggested that the children of today and the future will disproportionately suffer from the dangers and catastrophic impacts of climate change. Ridhima pointed to the failure of the Government of India to address the adverse impacts of climate change under the existing framework of environmental law and jurisprudence.

Her petition, as one of the main points of agitation, pointed towards the NAPCC as not being target oriented, stating that the plan was simply a list of proposed activities lacking time-bound goals with regard to emissions reduction and any scientific investigation as its basis.

In January 2019, the Green Tribunal disposed of Ridhima’s Petition by observing that there was no reason to presume that the Paris Agreement and other international protocols are not reflected in the policies of the Government of India, or are not taken into consideration in granting environment clearances; therefore, there was no need for the green tribunal to pass any further directions on this issue. She has now appealed against the decision of the Green Tribunal and the case is currently sub-judice before the Supreme Court of India.

E. The Future of Climate Litigation in India

There has also been an evident trend in the rise of such cases globally. Because the first decision in the Urgenda case was issued in 2015, individuals and communities have initiated proceedings against states seeking to achieve similar rulings in Ireland, France, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, the U.S., Canada, Peru, South Korea, and India.Footnote 46 These cases have sought to compel governments to accelerate their efforts to implement emissions reduction targets;Footnote 47 demonstrate that national GHG emissions goals are insufficiently ambitious or not being pursued at all;Footnote 48 connect harms suffered by vulnerable communities to emitters responsible for a share of global temperature increases;Footnote 49 bring global climate change concerns to bear on local action;Footnote 50 and either force adaptation action or recover damages that result from others’ failures to adapt.Footnote 51

It is noteworthy that the Paris Agreement on Climate Change under Article 12 establishes that “[p]arties shall cooperate in taking measures, as appropriate, to enhance climate change education, training, public awareness, public participation, and public access to information, recognizing the importance of these steps with respect to enhancing actions under this Agreement.” Specifically, the process of climate change litigation, both in India, and globally, has been able to succeed on each of these counts listed under Article 12 of the Paris Agreement—it has strengthened climate awareness and education, both among the youth and elderly through the media attention that such cases have garnered, generating curiosity in the populace, and further increasing access to information and participation/litigation.Footnote 52

Public awareness, it has been observed, anent the impact of human activities on climate change and the impact of climate change itself on the existence of all living things is increasing, and that these impacts also affect social relations within the societyFootnote 53 requiring legal regulation. This gives rise to a reasonable question about the formation of the concept of climate change law.Footnote 54 Along with this, doubts are expressed about the specifics of legal regulation of climate change and its qualitative difference from the regulation of environmental protection. Such discussions about the need to recognize climate change law as an independent branch of law at the doctrinal level, which stimulate initiatives to develop climate change legislation and potentially litigation, reflect the growing public awareness of these issues.

F. Conclusion

The constant dicta of various courts in India within the environmental domain stands on the shoulders of various constitutional factors that have helped the judicial system realize a creative and active role through innovative jurisprudence. In the past, as in the case of Vishaka, such constant jurisprudence in favor of recognizing rights not transcribed by the Legislature has encouraged specific laws on the subjects eventually.

On one hand, the environmental rights, including those against pollution, have been recognized as fundamental rights of the citizens, under the constitution. On the other hand, strictly in relation to climate change, concepts such as calculating the carbon footprint of an illegal construction to calculating damages have been rejected for want of scientific evidence. The next decade of such jurisprudence would dictate where the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide, set to become the most populous, would stand on dedicated climate rights of future generations.