Introduction

Charitable giving involves voluntarily donating money, goods, or time and resources to help individuals or organisations dedicated to social causes (Schervish & Havens, Reference Schervish and Havens1997). Individual contributions are vital in supporting non-profit organisations, fostering community involvement, and addressing societal challenges (Kumi, Reference Kumi2022; List, Reference List2011). Motivations for giving, however, vary based on countries, socio-economic contexts, and individual characteristics. Despite the acknowledged importance of understanding these motivations, comprehensive studies regarding individual giving behaviour in Africa and Ghana are lacking (Alagidede & Moyo, Reference Alagidede and Moyo2020; Kumi, Reference Kumi2019; Schwier et al., Reference Schwier, Holland, Andrian and Hayi-Charters2021). To this extent, and even as countries experience economic growth, there is limited systematic evidence regarding giving practices on the continent (Çarkoğlu et al., Reference Çarkoğlu, Aytaç and Campbell2017, p. 41). Using primary data from adult Ghanaians, this study investigates and explains individual charitable giving among Ghanaians, using the Self Determination Theory (SDT) as the analytical framework. The study used a mixed-method approach to uncover the factors influencing charitable giving and answered the question, “What motivates individual charitable giving among Ghanaians?”.

This study fills gaps in the existing literature by providing authentic insights and theoretical explanations into individuals’ giving intentions. The findings contribute to theoretical knowledge by supporting the universality of SDT as a motivational theory and demonstrating that giving behaviours occur in the right socio-cultural environment. (Chirkov et al., Reference Chirkov, Ryan, Kim and Kaplan2003). The results also offer practical suggestions to promote philanthropy and charitable contributions in Ghana and within the African context.

Study Context

Charitable giving in Ghana, influenced by a blend of cultural, social, economic, religious and historical factors are, rooted in the African traditions of solidarity, reciprocity, and mutual aid that occurs among family, friends and neighbours (Aidoo, Reference Aidoo2012; Atibil, Reference Atibil and Obadare2014; Hanson, Reference Hanson2005; Kyei, Reference Kyei2000; Wilkinson-Maposa et al., Reference Wilkinson-Maposa, Fowler, Oliver-Evans and Mulenga2005). In African communities, concepts like the Southern African “ubuntu” (humanity and interconnectedness) and Eastern Africa “Harambee” (let us pull together) emphasise communal support and nurturing a sense of obligation and expectations of reciprocal action to provide financial and material assistance within extended families and communities (Mottiar & Ngcoya, Reference Mottiar and Ngcoya2016). Philanthropic practices include wealthy individuals or High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNWI) who give to others and support community projects (Mahomed et al., Reference Mahomed, Julien and Samuels2014; Nedbank, 2019).

With a population of approximately 31 million, Ghana has a rich tapestry of cultural diversity and a history marked by colonialism, independence, economic struggles, and democratic growth (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], 2019). The nation comprises three major ethnic groups, with Akan, Mole-Dagbani, and Ewe communities constituting over 77% of the population (GSS, 2021a). Females account for 50.7% of the population, and about 42% of Ghanaians are married. Ghana consists of 16 regions, with Greater Accra being the most populous, followed by Ashanti, Eastern, and Central regions. The majority of the population (94%) adheres to various religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Indigenous African beliefs (GSS, 2021b). The country’s economy is diverse and driven by agriculture, mining (particularly gold), petroleum exports, and services, making Ghana economically stable in West Africa (World Bank, 2022). However, Ghana grapples with challenges such as income inequality, unemployment, healthcare disparities, educational gaps, and poverty, compelling individuals, and communities to engage in charitable giving to address local needs (Jeong, Reference Jeong1997).

Charitable giving runs deep within Ghanaian societies and includes diverse individuals, self-help groups, and community organisations such as “nnoboa” (cooperatives) and “asafo” (fighting companies or traditional men’s associations). Extended families also serve as vital safety nets, offering economic and emotional support (Fowler & Mati, Reference Fowler and Mati2019; Owusu & Baidoo, Reference Owusu and Baidoo2021). Cultural norms and unwritten rules strongly influence giving, with non-compliance met with punitive measures (Berry, Reference Berry1995, p. 115; Dzor & White, Reference Dzor and White2019, p. 229). Individuals thus develop a strong group identity, aligning with community values (Schervish & Havens, Reference Schervish and Havens1997). Additionally, cultural, and religious beliefs emphasise communal responsibility for others’ well-being (Kumi, Reference Kumi2019). Giving in Ghana is characterised by trust, informality, and directness, primarily benefiting the extended family, friends, or individuals with personal connections, especially if they share ethnic backgrounds or localities (Moyo & Ramsamy, Reference Moyo and Ramsamy2014). Wealthy individuals donate through institutions, supporting community initiatives, volunteering, and helping neighbours, which foster community bonds and trust (Kumi, Reference Kumi2019; Wilkinson-Maposa et al., Reference Wilkinson-Maposa, Fowler, Oliver-Evans and Mulenga2005).

This study’s theory-based approach to individual giving helped explain and predict Ghanaian generousity and holds significant academic and practical importance. The Self Determination Theory (SDT) framework transcends cultural and geographical boundaries, making the results applicable across various African cultures. The SDT’s flexibility in embracing other academic disciplines allows for interdisciplinary collaboration, providing a holistic understanding of giving behaviour. Also, the methodology offers a validated approach rich in context to explore complex questions about giving motivations. Finally, the study’s results are valuable to fundraising practitioners, governments, NGOs, local communities, and religious institutions, who motivate individual involvement in prosocial activities. Understanding the factors influencing giving behaviour in the Ghanaian context is crucial for these practical applications.

The study focused on Ghanaian individuals aged 18 and above who reside in Ghana and abroad. It did not include institutional and corporate donors, allowing for an in-depth analysis of personal and environmental factors influencing individual charitable giving. Accordingly, the specific objective of this study was to identify and explain the demographic, socio-economic and behavioural factors that determine the individual’s likelihood to give cash, gifts, or volunteer time to help others. This narrowed scope provided valuable insights that might not be apparent in a broader study encompassing different and varied donor types.

Theoretical Explanation of Giving Behaviours

The literature on giving differentiates between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. Extrinsic motivation arises from external outcomes, while intrinsic motivation derives from internal fulfilment (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985; Legault, Reference Legault2016). Various economics, sociology, and psychology studies have explored and tried to explain motivations (Sargeant & Woodliffe, Reference Sargeant, Woodliffe and Wymer2007; Smith & McSweeney, Reference Smith and McSweeney2007). Economic theories argue that charitable giving is rational human behaviour of expecting tangible and intangible rewards and compares with exchanges or transactions occurring while purchasing goods and services (Chang, Reference Chang2014). Philanthropy in this context involves donors seeking external rewards while benefiting recipients (Banerjee & Manoj, Reference Banerjee and Manoj2017; Konrath & Handy, Reference Konrath and Handy2018). Sociological theories suggest that normative and regulated contexts influence giving behaviour (Allison, 1992; Margolis, 1982). Social theories, therefore, emphasise the importance of belonging and conformity to social norms and values that define communal living (Aina & Moyo, Reference Aina and Moyo2013; Banerjee & Manoj, Reference Banerjee and Manoj2017; Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a; Schervish & Havens, Reference Schervish and Havens1997; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner2004). On the other hand, psychological theories focus on intrinsic motivations, emphasising satisfaction, self-esteem, and emotions (Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2004). They explain that behaviours, like altruism, originate from moral beliefs and values, reflecting empathy, compassion, selflessness, and justice (Andreoni, Reference Andreoni1990; Davis, Reference Davis1994; Kerr et al., Reference Kerr, Godfrey-Smith and Feldman2004). Altruism, for example, is categorised as ‘pure’ (others’ interest), describing deliberate, intentional, and volitional acts focused on benefiting others (Aknin et al., Reference Aknin, Barrington-Leigh, Dunn, Helliwell, Burns, Biswas-Diener and Norton2013) and “impure”, or “warm glow” (self-interest) driven by the personal and egoistic tendencies for the emotional reward of generosity (Andreoni & Harbaugh, Reference Andreoni and Harbaugh2008).

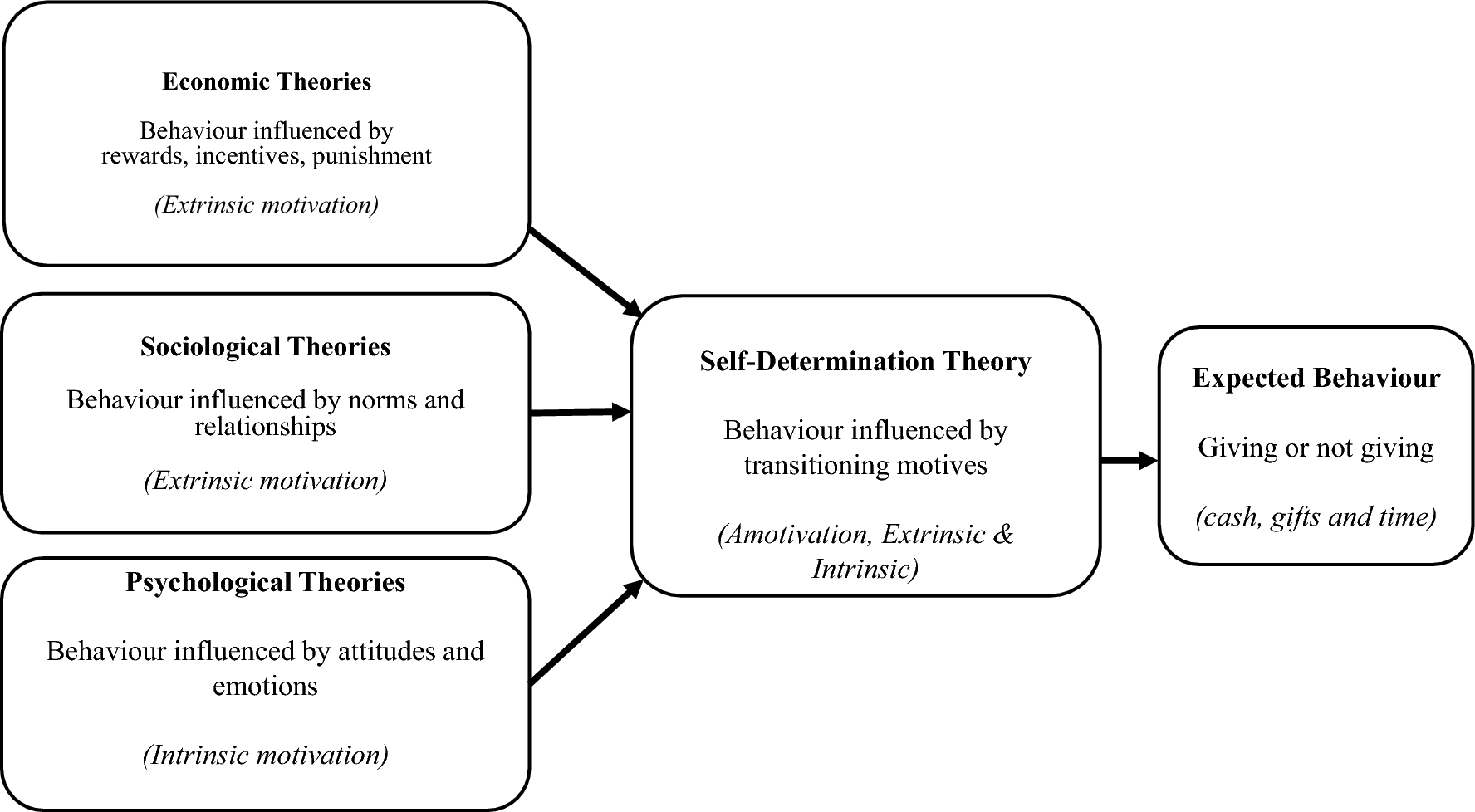

The different economic, sociological, and psychological theories do not entirely explain human generousity because giving actions are a complex mix of internal dispositions and external environmental factors. Thus, this study used the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to explore the extrinsic, intrinsic, and combined motivations underlying individuals giving or not giving money, gifts, and time to support others in a Ghanaian context. Figure 1 shows the relationship and the expected giving behaviour between the economic, sociological, and psychological theories and the SDT.

Fig. 1 Theoretical perspectives of motivation to give

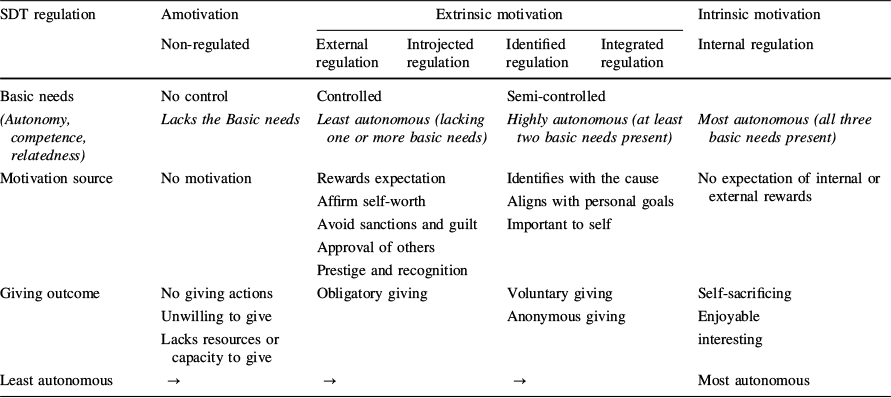

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) expands on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, incorporating nuanced aspects from economic, sociological, and psychological perspectives (Scott Rigby et al., Reference Scott Rigby, Deci, Patrick and Ryan1992). Within SDT, amotivation denotes a complete lack of motivation. Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2000) outline a continuum of internalisation in which extrinsic motivation can become autonomous. Behaviour regulation ranges from amotivation (unregulated), marked by a lack of interest or intention to donate, to intrinsic motivation (self-regulated and voluntary), characterised by self-sacrificing, voluntary, and pleasurable giving. Extrinsic motivation includes four regulatory types: External (rewards, punishments, and social norms), Introjected (internal pressures like guilt, self-esteem, prestige, and recognition), Identified (recognising the value of the giving and aligning with the cause), and Integrated (assimilating behaviour into identity).

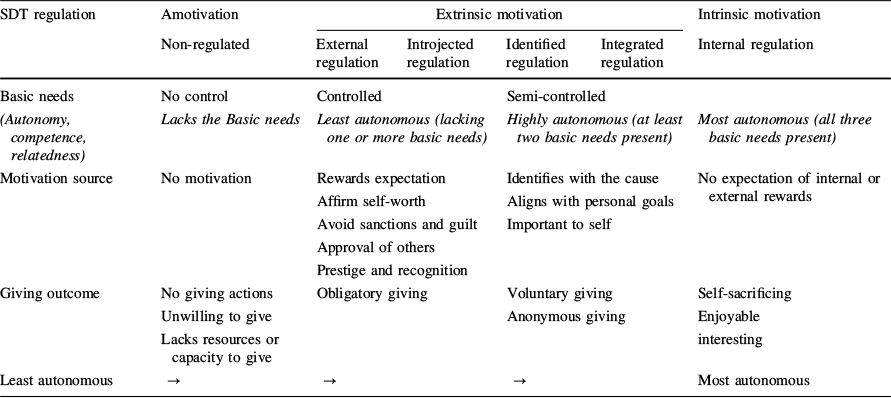

Table 1 illustrates the transition towards autonomy or self-determination and the satisfaction or frustration of three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy (self-initiated decisions without coercion), competence (ability and resources for change), and relatedness (social belonging). The different motivation types, shaped by these three fundamental needs, are an integral part of the Self-Determination Theory framework and explain how more autonomous forms of motivation nurture positive donation outcomes (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000).

Table 1 SDT continuum of regulated behaviours and giving outcomes

SDT regulation |

Amotivation |

Extrinsic motivation |

Intrinsic motivation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-regulated |

External regulation |

Introjected regulation |

Identified regulation |

Integrated regulation |

Internal regulation |

|

Basic needs |

No control |

Controlled |

Semi-controlled |

|||

(Autonomy, competence, relatedness) |

Lacks the Basic needs |

Least autonomous (lacking one or more basic needs) |

Highly autonomous (at least two basic needs present) |

Most autonomous (all three basic needs present) |

||

Motivation source |

No motivation |

Rewards expectation Affirm self-worth Avoid sanctions and guilt Approval of others Prestige and recognition |

Identifies with the cause Aligns with personal goals Important to self |

No expectation of internal or external rewards |

||

Giving outcome |

No giving actions Unwilling to give Lacks resources or capacity to give |

Obligatory giving |

Voluntary giving Anonymous giving |

Self-sacrificing Enjoyable interesting |

||

Least autonomous |

→ |

→ |

→ |

Most autonomous |

||

The continuum of relative autonomy in SDT depicts motivation types, regulations and the corresponding levels of control and autonomy linked to each type, perceived sources, and the resulting outcome of giving. Adapted from Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan2009)

Individual Determinants of Giving Behaviours

The different theoretical explanations classify a complex mix of extrinsic, intrinsic and transition motivations driving individual philanthropic and charitable behaviour (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2007; Hoge, Reference Hoge and Yang1994; Rooney et al., Reference Rooney, Mesch, Chin and Steinberg2005; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Sen et al., Reference Sen, Chatterjee, Nayak and Mahakud2020). Extrinsic factors, which are demographic, social, and environmental determinants, include age (Halfpenny, Reference Halfpenny1999; Pharoah & Tanner, Reference Pharoah and Tanner1997), gender (Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Rooney, Chin and Steinberg2002; Rooney et al., Reference Rooney, Mesch, Chin and Steinberg2005), ethnicity (Jackson, Reference Jackson2001), income (Yen, Reference Yen2002), and employment (Pharoah & Tanner, Reference Pharoah and Tanner1997). For example, older individuals often contribute more due to increased disposable income, growing religiousness, independence, and awareness of others’ needs (Carman, Reference Carman2003; Lee & Chang, Reference Lee and Chang2008; Pharoah & Tanner, Reference Pharoah and Tanner1997), while gender disparities reveal that women tend to give more often whereas men donate larger amounts (Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011). Social factors include marital status (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2007), parental or family background (Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Klay and Douglass2001) and religion (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang and Tax2003; Hoge, Reference Hoge and Yang1994; Rooney et al., Reference Rooney, Mesch, Chin and Steinberg2005), while external environmental influences are the national, cultural and economic contexts shaping individual giving decisions (Mainardes et al., Reference Mainardes, Laurett, Degasperi and Lasso2017).

Intrinsic motivators like empathy, egoism and trust are the psychographic attitudes (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2007) and behaviours (Sen et al., Reference Sen, Chatterjee, Nayak and Mahakud2017) influencing helping behaviours (Lee & Chang, Reference Lee and Chang2007; Sargeant, 1999). Batson et al. (Reference Batson, O’Quin, Fultz, Vanderplas and Isen1983) suggest that personal distress fosters egoistic motives, while empathy leads to altruistic motives. Individuals with greater empathic concerns often exhibit generousity to enhance positive feelings or reduce negative ones (Batson, 1991; Verhaert & Van den Poel, Reference Verhaert and Van den Poel2011). Trust, integral to giving, involves vulnerability based on anticipating tangible or intangible reciprocal action. Trust denotes one party’s willingness to be susceptible, expecting the other party to fulfil a crucial action, promise or commitment (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995). The trust-giving relationship can have positive outcomes that lead to committed giving or negative outcomes, resulting in a reluctance to give (Treiblmaier & Pollach, Reference Treiblmaier and Pollach2008; Yang & Northcott, Reference Yang and Northcott2019).

Transitioning from extrinsic to intrinsic motivations are religious beliefs significantly influencing an individual’s charitable behaviour (Brooks, Reference Brooks2004; Park, Reference Park2021). “Extrinsic religiousness” describes obligatory practices like tithing in Christianity or zakat in Islam, where individuals must donate a portion of their earnings to religious institutions. “Intrinsic religiousness” involves voluntary, compassionate giving inspired by religious beliefs, such as almsgiving and freewill offerings. Religion also holds communal and social influence, prompting individuals to donate within their environmental context (Bekkers & Schuyt, Reference Bekkers and Schuyt2008; Septianto et al., Reference Septianto, Tjiptono, Paramita and Chiew2021). Religious beliefs thus impact giving behaviour through obligatory traditions (extrinsic) or voluntarily motivated actions (intrinsic).

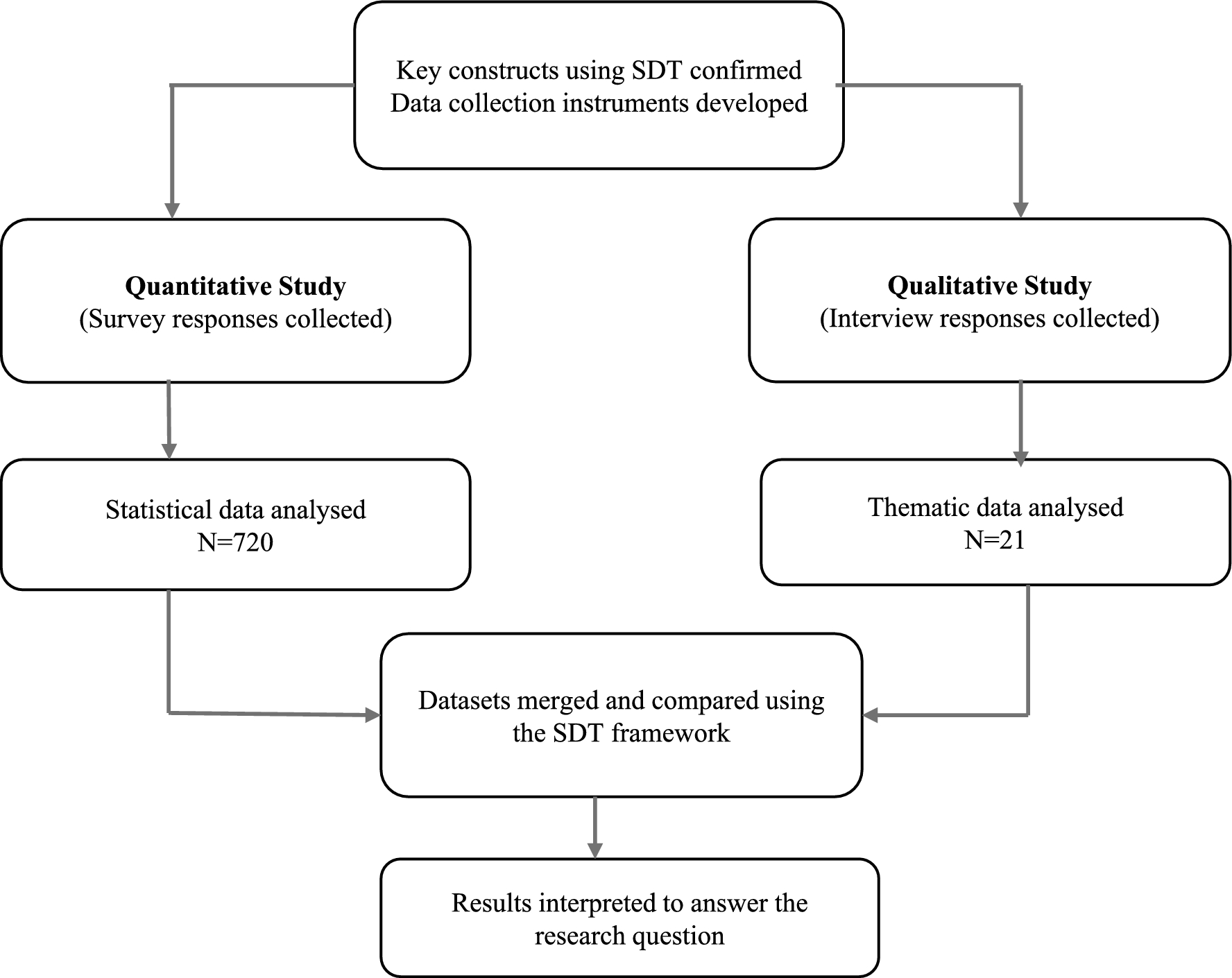

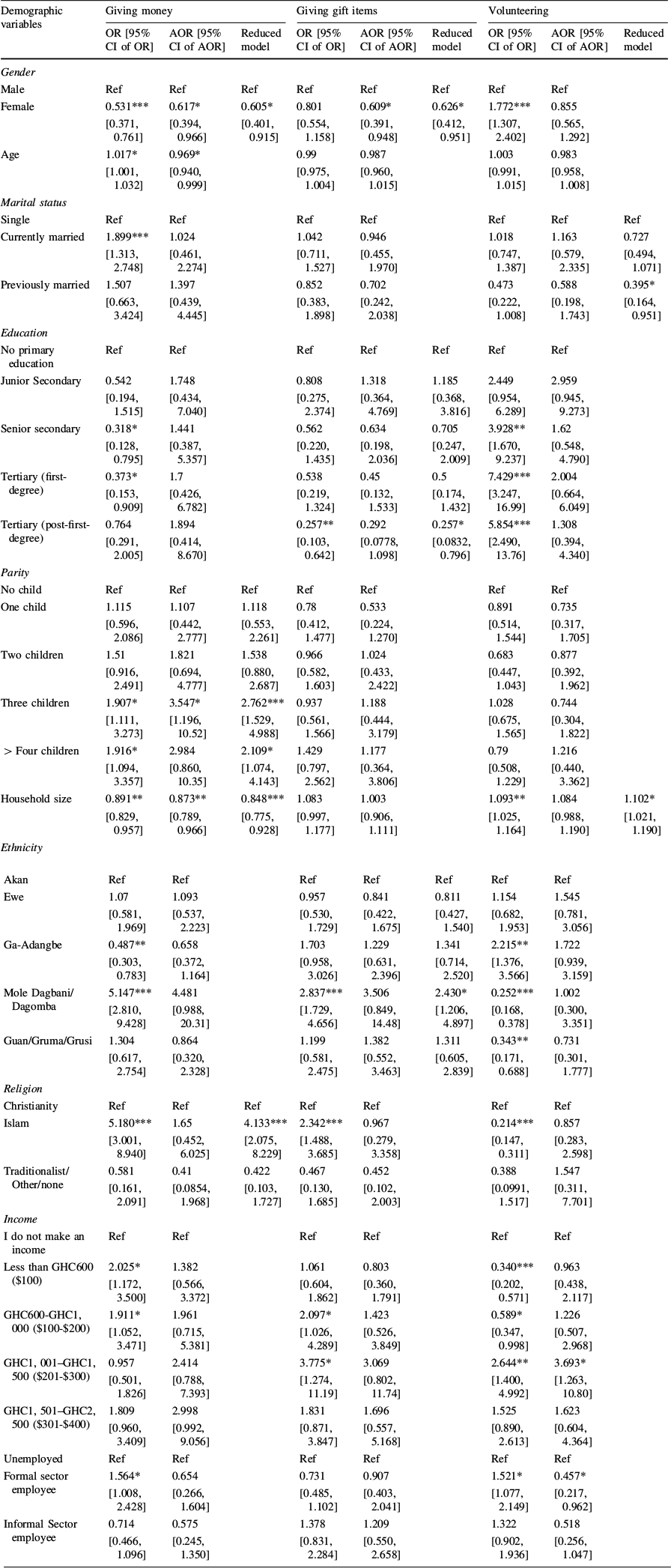

Research Design and Data

This study used a mixed-method convergent approach (Fig. 2), which involved collecting and analysing qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously from adult Ghanaians. Data from each method analysed separately were subsequently integrated for comparison, facilitating the interpretation needed to address the research questions.

Fig. 2 Convergent parallel mixed method study design.

Data Sources and Analysis

Survey and interview instruments were developed concurrently and aligned with self-determination theory (SDT) principles. These instruments clarified the study objectives, incorporating a screening question and details on independent variables like age, gender, income, ethnicity, and family size. A five-point Likert Scale facilitated quantifying and analysing the dependent variable, attitudes, and behaviours regarding giving practices among the sampled population.

The survey questionnaires randomly distributed online (through emails and social media) and through face-to-face interactions occurred between March and June 2021. A diverse sample of 720 individuals from Ghana and abroad responded to the questionnaires, ensuring diverse representation across the demographic, socio-economic, and geographic dispersion of Ghanaians.

Using binary logistic regression analysis illustrated in the model below helped determine how specific independent variables predicted charitable giving behaviour among Ghanaians. It also helped to provide insights into the direction and magnitude of each variable’s impact on the likelihood of charitable giving.

where:

P(Y = 1) represents the probability of charitable giving.

Β 0 is the intercept term.

Β 1, β 2, β 3, β 4 are the coefficients associated with the independent variables.

X 1, X 2, X 3, X 4 represent the independent demographic and behavioural variables such as gender, household size, financial constraints, and trust.

The regression analysis data were transformed into narratives, facilitating the integration and interpretation of findings, and establishing connections between qualitative and quantitative data. The quantitative analysis highlighted the significant influence of gender, household size, financial constraints, and trust on giving behaviours. The extensive random distribution of the questionnaires ensured a representative sample, allowing the extrapolation of study findings to a broader context. This rigorous approach bolstered the credibility and applicability of the study’s findings, providing valuable insights into determining charitable giving among Ghanaians.

Qualitative interviews, conducted simultaneously with the surveys, used purposive and convenient sampling methods, selecting participants from readily accessible individual Ghanaians, including family and friends, willing to participate in face-to-face or virtual interviews. The non-random sample of twenty-one participants was determined through saturation, indicating that additional respondents were unlikely to provide any new insights (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Each interview lasted between 30 and 40 min and was recorded, transcribed, and analysed using the “Open Code” software. Systematically analysing data, breaking them into categories, and identifying themes or patterns resulted in five key themes and fifteen sub-themes. Refining these themes to align with the data supported by relevant quotes provided insights into the giving behaviours.

Analysing the integrated quantitative data and qualitative narratives helped answer the research question. This triangulation approach of quantifying and comparing the results facilitated validating and strengthening the results from both study components, minimising potential biases, and enhancing overall credibility.

Sample Characteristics

For quantitative and qualitative studies, the research surveyed 741 Ghanaians aged 18 to 77, with an average age of 36 (SD, 12) and a male majority of 61%. A significant portion of respondents (60%) had tertiary education, while 8% had primary education or lacked formal education. Approximately 61% were employed in the public and private sectors or were self-employed, while others were unemployed or students. Notably, 22% did not disclose or had no income, and 19% fell into the lowest income brackets, earning less than GHC1000 ($100) monthly. Most (37%) had no children, whereas 35% had three or more. About 67% identified as Christians, 31% as Muslims, and a minority (1.4%) as traditionalists or had no religious affiliation. The Akan ethnic group were the majority (38%), followed by the Mole Dagbani/Dagombas, at 31% of the respondents. Over the past year, almost 90% of participants recalled helping others through cash donations, gifts, or volunteering to support individuals and organisations, and 9.7% indicated that they were hesitant to give. Gift items were the most common (81.2%), followed closely by cash donations (79.9%). Religion emerged as the primary motivation for giving by all interviewees, and a significant portion (60%) indicated occasional anonymous giving practices.

Results and Interpretation

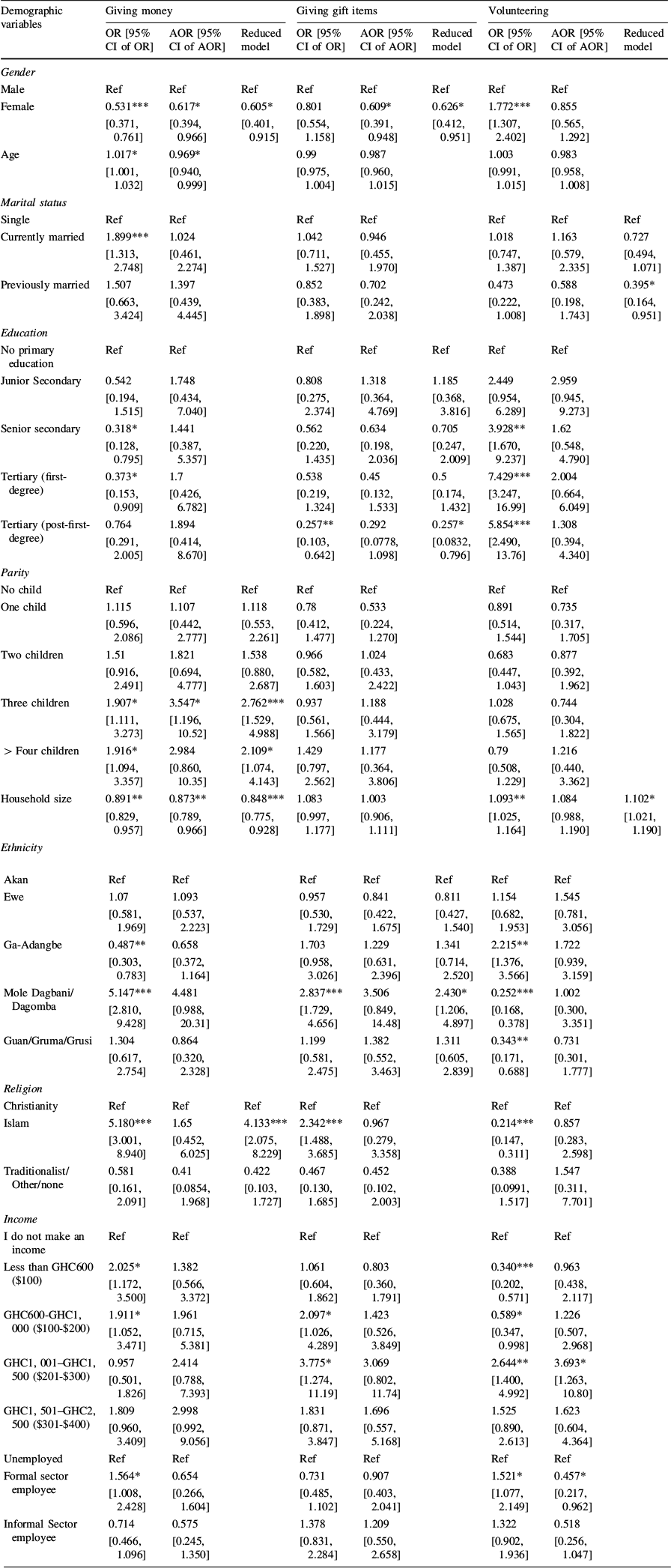

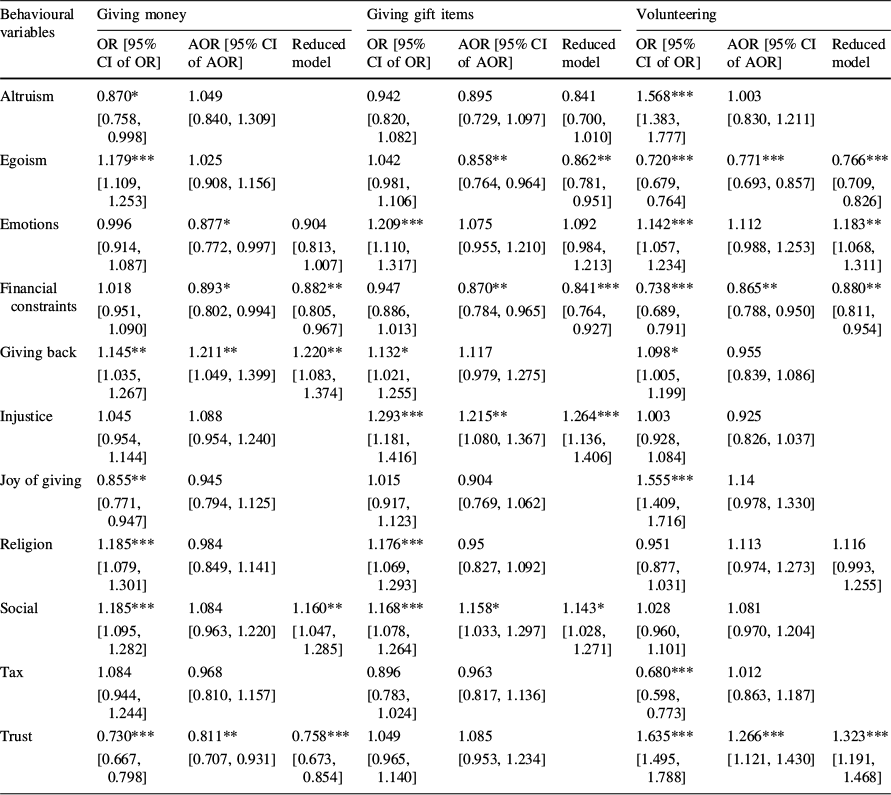

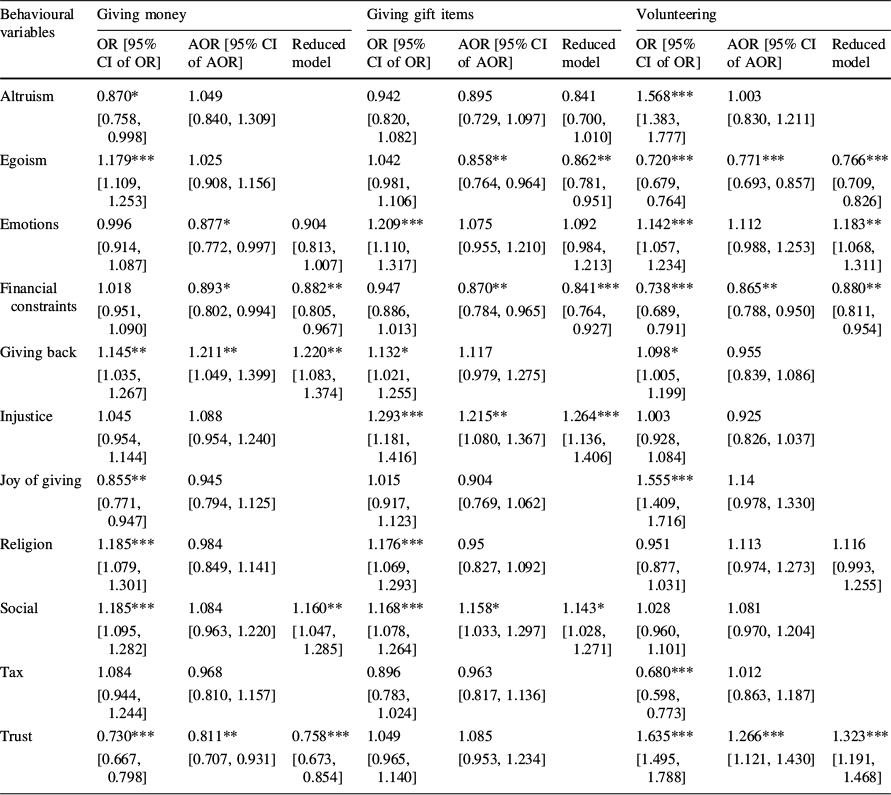

Tables 2 and 3 show the bivariable analysis examining the relationship between demographic factors and behaviours influencing monetary donations, gifts, and volunteering among Ghanaians. The odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR), along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), illustrate the probability of an event happening in comparison to a reference category (Szumilas, Reference Szumilas2010). The results, analysed within the optimal multivariable model, facilitated the identification of significant demographic and behavioural predictors influencing giving behaviours. The statistical significance, denoted by *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, and ***p < 0.01, signifies the probability of the observed outcomes being due to chance (Bhandari, Reference Bhandari2021).

Table 2 Demographic correlates of preferences for giving money, gifts and volunteering time

Demographic variables |

Giving money |

Giving gift items |

Volunteering |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

|

Gender |

|||||||||

Male |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

|

Female |

0.531*** |

0.617* |

0.605* |

0.801 |

0.609* |

0.626* |

1.772*** |

0.855 |

|

[0.371, 0.761] |

[0.394, 0.966] |

[0.401, 0.915] |

[0.554, 1.158] |

[0.391, 0.948] |

[0.412, 0.951] |

[1.307, 2.402] |

[0.565, 1.292] |

||

Age |

1.017* |

0.969* |

0.99 |

0.987 |

1.003 |

0.983 |

|||

[1.001, 1.032] |

[0.940, 0.999] |

[0.975, 1.004] |

[0.960, 1.015] |

[0.991, 1.015] |

[0.958, 1.008] |

||||

Marital status |

|||||||||

Single |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||

Currently married |

1.899*** |

1.024 |

1.042 |

0.946 |

1.018 |

1.163 |

0.727 |

||

[1.313, 2.748] |

[0.461, 2.274] |

[0.711, 1.527] |

[0.455, 1.970] |

[0.747, 1.387] |

[0.579, 2.335] |

[0.494, 1.071] |

|||

Previously married |

1.507 |

1.397 |

0.852 |

0.702 |

0.473 |

0.588 |

0.395* |

||

[0.663, 3.424] |

[0.439, 4.445] |

[0.383, 1.898] |

[0.242, 2.038] |

[0.222, 1.008] |

[0.198, 1.743] |

[0.164, 0.951] |

|||

Education |

|||||||||

No primary education |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||

Junior Secondary |

0.542 |

1.748 |

0.808 |

1.318 |

1.185 |

2.449 |

2.959 |

||

[0.194, 1.515] |

[0.434, 7.040] |

[0.275, 2.374] |

[0.364, 4.769] |

[0.368, 3.816] |

[0.954, 6.289] |

[0.945, 9.273] |

|||

Senior secondary |

0.318* |

1.441 |

0.562 |

0.634 |

0.705 |

3.928** |

1.62 |

||

[0.128, 0.795] |

[0.387, 5.357] |

[0.220, 1.435] |

[0.198, 2.036] |

[0.247, 2.009] |

[1.670, 9.237] |

[0.548, 4.790] |

|||

Tertiary (first-degree) |

0.373* |

1.7 |

0.538 |

0.45 |

0.5 |

7.429*** |

2.004 |

||

[0.153, 0.909] |

[0.426, 6.782] |

[0.219, 1.324] |

[0.132, 1.533] |

[0.174, 1.432] |

[3.247, 16.99] |

[0.664, 6.049] |

|||

Tertiary (post-first-degree) |

0.764 |

1.894 |

0.257** |

0.292 |

0.257* |

5.854*** |

1.308 |

||

[0.291, 2.005] |

[0.414, 8.670] |

[0.103, 0.642] |

[0.0778, 1.098] |

[0.0832, 0.796] |

[2.490, 13.76] |

[0.394, 4.340] |

|||

Parity |

|||||||||

No child |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||

One child |

1.115 |

1.107 |

1.118 |

0.78 |

0.533 |

0.891 |

0.735 |

||

[0.596, 2.086] |

[0.442, 2.777] |

[0.553, 2.261] |

[0.412, 1.477] |

[0.224, 1.270] |

[0.514, 1.544] |

[0.317, 1.705] |

|||

Two children |

1.51 |

1.821 |

1.538 |

0.966 |

1.024 |

0.683 |

0.877 |

||

[0.916, 2.491] |

[0.694, 4.777] |

[0.880, 2.687] |

[0.582, 1.603] |

[0.433, 2.422] |

[0.447, 1.043] |

[0.392, 1.962] |

|||

Three children |

1.907* |

3.547* |

2.762*** |

0.937 |

1.188 |

1.028 |

0.744 |

||

[1.111, 3.273] |

[1.196, 10.52] |

[1.529, 4.988] |

[0.561, 1.566] |

[0.444, 3.179] |

[0.675, 1.565] |

[0.304, 1.822] |

|||

> Four children |

1.916* |

2.984 |

2.109* |

1.429 |

1.177 |

0.79 |

1.216 |

||

[1.094, 3.357] |

[0.860, 10.35] |

[1.074, 4.143] |

[0.797, 2.562] |

[0.364, 3.806] |

[0.508, 1.229] |

[0.440, 3.362] |

|||

Household size |

0.891** |

0.873** |

0.848*** |

1.083 |

1.003 |

1.093** |

1.084 |

1.102* |

|

[0.829, 0.957] |

[0.789, 0.966] |

[0.775, 0.928] |

[0.997, 1.177] |

[0.906, 1.111] |

[1.025, 1.164] |

[0.988, 1.190] |

[1.021, 1.190] |

||

Ethnicity |

|||||||||

Akan |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||

Ewe |

1.07 |

1.093 |

0.957 |

0.841 |

0.811 |

1.154 |

1.545 |

||

[0.581, 1.969] |

[0.537, 2.223] |

[0.530, 1.729] |

[0.422, 1.675] |

[0.427, 1.540] |

[0.682, 1.953] |

[0.781, 3.056] |

|||

Ga-Adangbe |

0.487** |

0.658 |

1.703 |

1.229 |

1.341 |

2.215** |

1.722 |

||

[0.303, 0.783] |

[0.372, 1.164] |

[0.958, 3.026] |

[0.631, 2.396] |

[0.714, 2.520] |

[1.376, 3.566] |

[0.939, 3.159] |

|||

Mole Dagbani/Dagomba |

5.147*** |

4.481 |

2.837*** |

3.506 |

2.430* |

0.252*** |

1.002 |

||

[2.810, 9.428] |

[0.988, 20.31] |

[1.729, 4.656] |

[0.849, 14.48] |

[1.206, 4.897] |

[0.168, 0.378] |

[0.300, 3.351] |

|||

Guan/Gruma/Grusi |

1.304 |

0.864 |

1.199 |

1.382 |

1.311 |

0.343** |

0.731 |

||

[0.617, 2.754] |

[0.320, 2.328] |

[0.581, 2.475] |

[0.552, 3.463] |

[0.605, 2.839] |

[0.171, 0.688] |

[0.301, 1.777] |

|||

Religion |

|||||||||

Christianity |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

||

Islam |

5.180*** |

1.65 |

4.133*** |

2.342*** |

0.967 |

0.214*** |

0.857 |

||

[3.001, 8.940] |

[0.452, 6.025] |

[2.075, 8.229] |

[1.488, 3.685] |

[0.279, 3.358] |

[0.147, 0.311] |

[0.283, 2.598] |

|||

Traditionalist/Other/none |

0.581 |

0.41 |

0.422 |

0.467 |

0.452 |

0.388 |

1.547 |

||

[0.161, 2.091] |

[0.0854, 1.968] |

[0.103, 1.727] |

[0.130, 1.685] |

[0.102, 2.003] |

[0.0991, 1.517] |

[0.311, 7.701] |

|||

Income |

|||||||||

I do not make an income |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

|||

Less than GHC600 ($100) |

2.025* |

1.382 |

1.061 |

0.803 |

0.340*** |

0.963 |

|||

[1.172, 3.500] |

[0.566, 3.372] |

[0.604, 1.862] |

[0.360, 1.791] |

[0.202, 0.571] |

[0.438, 2.117] |

||||

GHC600-GHC1, 000 ($100-$200) |

1.911* |

1.961 |

2.097* |

1.423 |

0.589* |

1.226 |

|||

[1.052, 3.471] |

[0.715, 5.381] |

[1.026, 4.289] |

[0.526, 3.849] |

[0.347, 0.998] |

[0.507, 2.968] |

||||

GHC1, 001–GHC1, 500 ($201-$300) |

0.957 |

2.414 |

3.775* |

3.069 |

2.644** |

3.693* |

|||

[0.501, 1.826] |

[0.788, 7.393] |

[1.274, 11.19] |

[0.802, 11.74] |

[1.400, 4.992] |

[1.263, 10.80] |

||||

GHC1, 501–GHC2, 500 ($301-$400) |

1.809 |

2.998 |

1.831 |

1.696 |

1.525 |

1.623 |

|||

[0.960, 3.409] |

[0.992, 9.056] |

[0.871, 3.847] |

[0.557, 5.168] |

[0.890, 2.613] |

[0.604, 4.364] |

||||

Unemployed |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

Ref |

|||

Formal sector employee |

1.564* |

0.654 |

0.731 |

0.907 |

1.521* |

0.457* |

|||

[1.008, 2.428] |

[0.266, 1.604] |

[0.485, 1.102] |

[0.403, 2.041] |

[1.077, 2.149] |

[0.217, 0.962] |

||||

Informal Sector employee |

0.714 |

0.575 |

1.378 |

1.209 |

1.322 |

0.518 |

|||

[0.466, 1.096] |

[0.245, 1.350] |

[0.831, 2.284] |

[0.550, 2.658] |

[0.902, 1.936] |

[0.256, 1.047] |

||||

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Table 3 Behavioural correlates of preferences for giving money, gifts and volunteering time

Behavioural variables |

Giving money |

Giving gift items |

Volunteering |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

OR [95% CI of OR] |

AOR [95% CI of AOR] |

Reduced model |

|

Altruism |

0.870* |

1.049 |

0.942 |

0.895 |

0.841 |

1.568*** |

1.003 |

||

[0.758, 0.998] |

[0.840, 1.309] |

[0.820, 1.082] |

[0.729, 1.097] |

[0.700, 1.010] |

[1.383, 1.777] |

[0.830, 1.211] |

|||

Egoism |

1.179*** |

1.025 |

1.042 |

0.858** |

0.862** |

0.720*** |

0.771*** |

0.766*** |

|

[1.109, 1.253] |

[0.908, 1.156] |

[0.981, 1.106] |

[0.764, 0.964] |

[0.781, 0.951] |

[0.679, 0.764] |

[0.693, 0.857] |

[0.709, 0.826] |

||

Emotions |

0.996 |

0.877* |

0.904 |

1.209*** |

1.075 |

1.092 |

1.142*** |

1.112 |

1.183** |

[0.914, 1.087] |

[0.772, 0.997] |

[0.813, 1.007] |

[1.110, 1.317] |

[0.955, 1.210] |

[0.984, 1.213] |

[1.057, 1.234] |

[0.988, 1.253] |

[1.068, 1.311] |

|

Financial constraints |

1.018 |

0.893* |

0.882** |

0.947 |

0.870** |

0.841*** |

0.738*** |

0.865** |

0.880** |

[0.951, 1.090] |

[0.802, 0.994] |

[0.805, 0.967] |

[0.886, 1.013] |

[0.784, 0.965] |

[0.764, 0.927] |

[0.689, 0.791] |

[0.788, 0.950] |

[0.811, 0.954] |

|

Giving back |

1.145** |

1.211** |

1.220** |

1.132* |

1.117 |

1.098* |

0.955 |

||

[1.035, 1.267] |

[1.049, 1.399] |

[1.083, 1.374] |

[1.021, 1.255] |

[0.979, 1.275] |

[1.005, 1.199] |

[0.839, 1.086] |

|||

Injustice |

1.045 |

1.088 |

1.293*** |

1.215** |

1.264*** |

1.003 |

0.925 |

||

[0.954, 1.144] |

[0.954, 1.240] |

[1.181, 1.416] |

[1.080, 1.367] |

[1.136, 1.406] |

[0.928, 1.084] |

[0.826, 1.037] |

|||

Joy of giving |

0.855** |

0.945 |

1.015 |

0.904 |

1.555*** |

1.14 |

|||

[0.771, 0.947] |

[0.794, 1.125] |

[0.917, 1.123] |

[0.769, 1.062] |

[1.409, 1.716] |

[0.978, 1.330] |

||||

Religion |

1.185*** |

0.984 |

1.176*** |

0.95 |

0.951 |

1.113 |

1.116 |

||

[1.079, 1.301] |

[0.849, 1.141] |

[1.069, 1.293] |

[0.827, 1.092] |

[0.877, 1.031] |

[0.974, 1.273] |

[0.993, 1.255] |

|||

Social |

1.185*** |

1.084 |

1.160** |

1.168*** |

1.158* |

1.143* |

1.028 |

1.081 |

|

[1.095, 1.282] |

[0.963, 1.220] |

[1.047, 1.285] |

[1.078, 1.264] |

[1.033, 1.297] |

[1.028, 1.271] |

[0.960, 1.101] |

[0.970, 1.204] |

||

Tax |

1.084 |

0.968 |

0.896 |

0.963 |

0.680*** |

1.012 |

|||

[0.944, 1.244] |

[0.810, 1.157] |

[0.783, 1.024] |

[0.817, 1.136] |

[0.598, 0.773] |

[0.863, 1.187] |

||||

Trust |

0.730*** |

0.811** |

0.758*** |

1.049 |

1.085 |

1.635*** |

1.266*** |

1.323*** |

|

[0.667, 0.798] |

[0.707, 0.931] |

[0.673, 0.854] |

[0.965, 1.140] |

[0.953, 1.234] |

[1.495, 1.788] |

[1.121, 1.430] |

[1.191, 1.468] |

||

Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Survey Results

The analysis from Table 2 provides valuable insights into the nuanced demographic factors influencing giving money, gifts, and volunteering. Key observations include:

1. Gender Differences: Females exhibit significantly lower odds (AOR, 0.617) of giving money and gifts (AOR, 0.609).

2. Family Size Impact: Having more than three children increases the odds of giving money, while larger household sizes decrease the odds of giving.

3. Religious Influence: Muslims are 1.65 times more likely to give money compared to Christians.

4. Educational Attainment: Higher education levels (senior secondary, tertiary degrees) are associated with decreased odds of giving gifts (AOR, 0.119).

5. Ethnic Disparities: Various ethnic groups show variations in the odds of giving gifts, with Mole Dagbani/Dagomba and Ga-Adangbe ethnic groups having higher odds than Akans.

6. Marital Status Impact: Married individuals have significantly lower odds of volunteering time than single individuals.

7. Household Size and Volunteering: Smaller households exhibit significantly higher odds (AOR, 1.102) of volunteering time.

Table 3 provides insights into the behavioural preferences for giving. Individuals with higher emotional involvement and those facing financial constraints have significantly lower odds of giving money (AOR, 0.877 and 0.0893, respectively). However, the desire to give back and social norms significantly increase the likelihood of giving money. On the other hand, trust has a complex relationship with giving money, initially decreasing the odds by a factor of 0.811 (AOR).

Regarding gift giving, egoistic tendencies and financial constraints reduce the likelihood (0.858, AOR and O.870, AOR, respectively). Meanwhile, perceptions of injustice, social norms, and trust enhance the probability of gift-giving. Moreover, emotions, religious beliefs, and trust positively influence the propensity for volunteering.

The analysis presented in Tables 2 and 3 underscores the multifaceted nature of behavioural factors shaping philanthropic and charitable choices. Gender, household size, financial constraints, and trust emerged as pivotal influencers across different forms of giving. Financial constraints emerged as the predominant behavioural factor influencing all three giving types. Additionally, egoism, societal expectations, and trust influence at least two giving types.

Interview Results

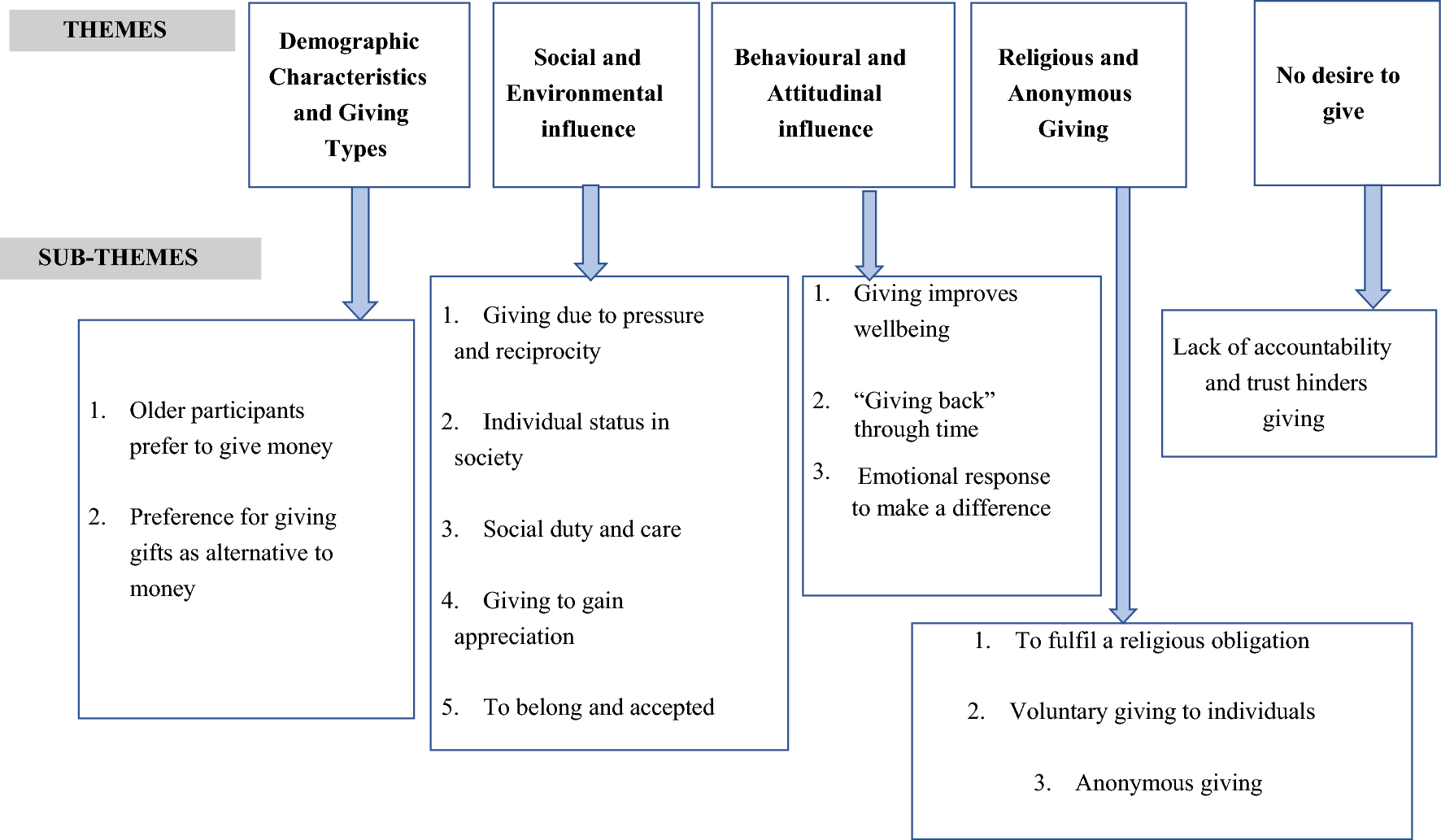

After coding and classifying the qualitative data, primary and sub-themes aligned with the theoretical approach and giving types emerged. The five themes were (1) Demographic characteristics and giving types, (2) Social and environmental influence, (3) Behavioural and attitudinal influence on giving, (4) Religious and anonymous giving and (5) No desire to give (amotivation). Figure 3 illustrates the primary and sub-themes.

Fig. 3 Themes and sub-themes from interview responses

Demographic and Social Influence on Giving Types

The qualitative study revealed that age and societal norms function as external motivations, significantly influencing the giving of cash, gifts, and time to support others and organisations among Ghanaians. As evidenced by participants aged forty and above, giving cash was easier and more convenient than giving gifts or dedicating time. For example, a 49-year-old lawyer indicated her inclination towards giving cash, stating that:

“…because that is what I can easily and readily give. I am busy most of the time doing so many things”.

Similarly, a 67-year-old physician specialist remarked, “It is usually money and then followed by gifts. I tend to be jealous of my time”.

Conversely, a 27-year-old female participant articulated that,

“Time would come first, and then cash, not so much with gifts. I prefer to give my time to people if they ask for time or help to do something”.

The interviews also revealed that social norms like reciprocity, status, duty, mutual obligation, belonging, appreciation and avoiding group sanctions influence individuals’ generosity. For instance, reciprocity involves giving with the expectation of receiving something in return, as a 55-year-old male educator illustrates.

“I hope that one day, if I get into something like that, and I genuinely require help, I will also find help from those who can help without begging”.

These external social norms and cultural expectations define and reinforce giving behaviour across different demographic groups.

Behavioural Response and Religious Influence on Giving Behaviour

Behavioural and attitudinal influencing factors aligned with the individual’s values and goals enhance psychological well-being and promote positive emotions like happiness, fulfilment, relief, honour, or appreciation. For example, in the following quote, a 49-year-old lawyer emphasised the importance of acknowledgement and gratitude when giving to organisations.

“When I give to an organisation, I expect that they will acknowledge receipt and say thank you”.

A 21-year-old female highlighted the satisfaction of helping others in need.

“It feels good to know you can help someone when they need you”.

One older participant, 63 years old, highlighted altruistic motives such as sympathy, compassion, pity, and a desire to contribute to the community, and the significant impact of assisting those in need.

“It is about the individual in need and the potential to make a difference in their life”.

Religious and anonymous giving emerged as strong motivators that combine external and internal motives. A 63-year-old male participant cited religious duty and personal salvation as driving forces behind philanthropy.

“What influences me is not just philanthropy but a Christian duty, that if God blesses one, he must also be a blessing to others”.

Anonymous giving was associated with altruism and personal satisfaction, as expressed by a 32-year-old trader who emphasised the private nature of giving as a matter between oneself and a supreme being.

“I give because of God … it is between me and God, not others. If you do that [referring to non-anonymous giving], you do not get blessed”.

No Motivation to Give

The results show instances where individuals refrain from giving due to factors such as limited resources, scepticism about the impact of their donation, or distrust of the recipient, is reflected in the statement of a 45-year-old unemployed male:

“If I donate and perceive misuse of the contribution, I may hesitate to do so in the future”.

Overall, the analysed narratives suggest that demographic and social factors such as age, norms, religion, and reciprocity influence extrinsic motives. In contrast, behavioural characteristics like satisfaction, happiness, relief, anonymous giving, and trust stemming from emotional and internal sources influence intrinsic motives.

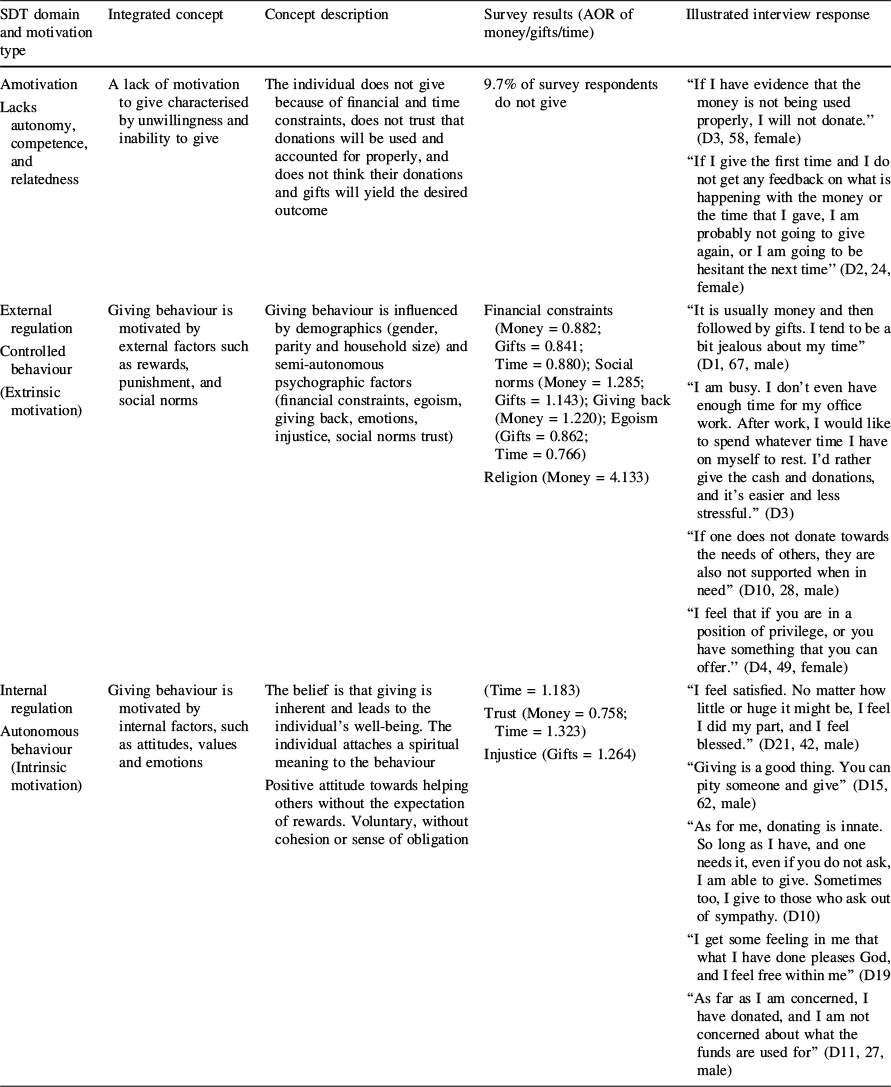

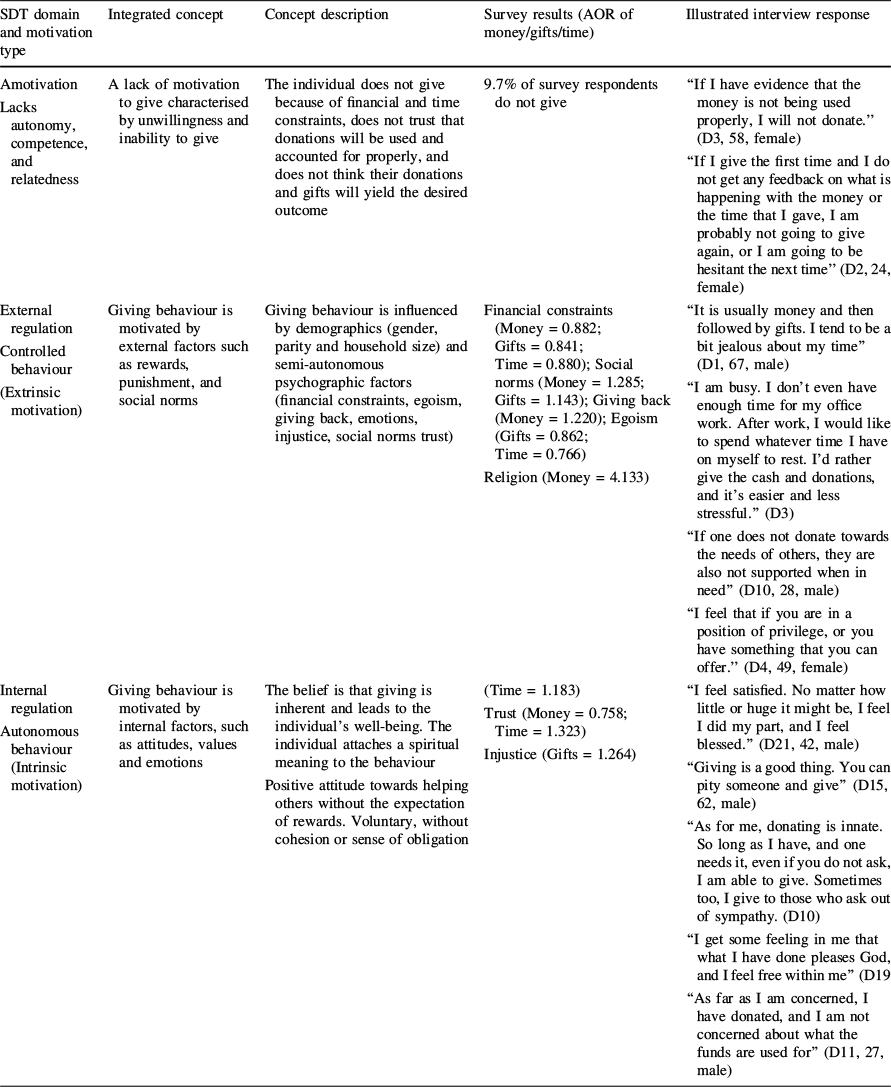

Integrated Qualitative and Quantitative Results

Table 4 synthesises the SDT domains and regulations informing the integration of quantitative and qualitative results. The three SDT motivation types—Amotivation—(unwillingness and inability to give), External Regulation (rewards, punishment, and norms), and Internal Regulation (attitudes, values, and emotions)—formed the theoretical bases for integration. The survey results identified demographic and behavioural influencing factors, while the interview results reinforced the quantitative data by providing narratives and explanations for the different giving motives. Integrating the qualitative narratives with quantitative data confirmed gender, age, and household size as the significant extrinsic demographic factors, and social norms, financial constraints, egoism, and emotions as the behavioural factors. Religion (obligatory and voluntary) and trust (positive and negative) have dual influencing roles. Using the SDT approach to integrate the findings in this study provided a comprehensive explanation of the individuals’ motivations for giving and how they can transition from extrinsic to internal motives such as personal commitment and values.

Table 4 Integration of survey and interview findings, informed by the SDT regulations

SDT domain and motivation type |

Integrated concept |

Concept description |

Survey results (AOR of money/gifts/time) |

Illustrated interview response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Amotivation Lacks autonomy, competence, and relatedness |

A lack of motivation to give characterised by unwillingness and inability to give |

The individual does not give because of financial and time constraints, does not trust that donations will be used and accounted for properly, and does not think their donations and gifts will yield the desired outcome |

9.7% of survey respondents do not give |

“If I have evidence that the money is not being used properly, I will not donate.” (D3, 58, female) “If I give the first time and I do not get any feedback on what is happening with the money or the time that I gave, I am probably not going to give again, or I am going to be hesitant the next time” (D2, 24, female) |

External regulation Controlled behaviour (Extrinsic motivation) |

Giving behaviour is motivated by external factors such as rewards, punishment, and social norms |

Giving behaviour is influenced by demographics (gender, parity and household size) and semi-autonomous psychographic factors (financial constraints, egoism, giving back, emotions, injustice, social norms trust) |

Financial constraints (Money = 0.882; Gifts = 0.841; Time = 0.880); Social norms (Money = 1.285; Gifts = 1.143); Giving back (Money = 1.220); Egoism (Gifts = 0.862; Time = 0.766) Religion (Money = 4.133) |

“It is usually money and then followed by gifts. I tend to be a bit jealous about my time” (D1, 67, male) “I am busy. I don’t even have enough time for my office work. After work, I would like to spend whatever time I have on myself to rest. I’d rather give the cash and donations, and it’s easier and less stressful.” (D3) “If one does not donate towards the needs of others, they are also not supported when in need” (D10, 28, male) “I feel that if you are in a position of privilege, or you have something that you can offer.” (D4, 49, female) |

Internal regulation Autonomous behaviour (Intrinsic motivation) |

Giving behaviour is motivated by internal factors, such as attitudes, values and emotions |

The belief is that giving is inherent and leads to the individual’s well-being. The individual attaches a spiritual meaning to the behaviour Positive attitude towards helping others without the expectation of rewards. Voluntary, without cohesion or sense of obligation |

(Time = 1.183) Trust (Money = 0.758; Time = 1.323) Injustice (Gifts = 1.264) |

“I feel satisfied. No matter how little or huge it might be, I feel I did my part, and I feel blessed.” (D21, 42, male) “Giving is a good thing. You can pity someone and give” (D15, 62, male) “As for me, donating is innate. So long as I have, and one needs it, even if you do not ask, I am able to give. Sometimes too, I give to those who ask out of sympathy. (D10) “I get some feeling in me that what I have done pleases God, and I feel free within me” (D19 “As far as I am concerned, I have donated, and I am not concerned about what the funds are used for” (D11, 27, male) |

Discussion of Results

Consistent with previous research, this study on Ghanaian giving behaviour reveals the influence of extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. External demographic and socio-economic factors, such as gender, age, household size, financial constraints and social norms, influence giving behaviour by imposing societal expectations that define and reinforce giving behaviour (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a; Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011). Internal behavioural and attitudinal factors like egoism, emotions, and trust appeal to the individual’s psychological needs and values (Andreoni, Reference Andreoni1990; Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2004). Notably, religious, and anonymous giving blend intrinsic and extrinsic motives.

Specifically, the results that females are less likely to give money and gifts are consistent with earlier research by DellaVigna et al. (Reference DellaVigna, List, Malmendier and Rao2013). The literature also shows significant gender differences and sometimes contradictory results (Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011) because several factors such as income disparities (Rooney et al., Reference Rooney, Mesch, Chin and Steinberg2005) and the display of spontaneity and empathy by females in their giving practices explain these differences (Charitable, Reference Charitable2017). On the other hand, men might engage in charitable giving to compete and flaunt their wealth through substantial donations (Connor, Reference Connor2015). These gender-related expectations and motives significantly shape giving behaviours, highlighting the evolving landscape of gender roles influenced by Africa’s social, cultural, and economic environment (Caprariello & Reis, Reference Caprariello and Reis2021; Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011; Olonade et al., Reference Olonade, Oyibode, Idowu, George, Iwelumor, Ozoya and Adetunde2021).

Additionally, age influences charitable giving preferences, with older participants preferring cash donations while younger individuals are inclined to volunteer. This result aligns with prior research attributing generational differences in attitudes towards giving and community involvement (Moschis, Reference Moschis1992). Older generations have greater financial autonomy and decision-making power, and younger individuals gain experience and see the immediate impact of their actions. In African and Ghanaian contexts, the ethos of giving and supporting others transcends age boundaries, reflecting a cultural norm of mutual aid (Schwier et al., Reference Schwier, Holland, Andrian and Hayi-Charters2021; Wilkinson & Fowler, Reference Wilkinson and Fowler2013).

This study observed that as household sizes increase, individuals are less likely to donate money but more willing to volunteer time, a trend consistent with Carter and Marx’s (Reference Carter and Marx2007) research on African American households, where a rise in the number of individuals in a household negatively impacts donations to neighbourhood and community organisations. The decline in monetary contributions within the African context may be due to individuals prioritising household and family expenses and social obligations, especially if the additional household members contribute to an increased size but are unemployed (Chang, Reference Chang2005; Yao, Reference Yao2015).

Existing literature on social norms and charitable giving emphasises the introjected behaviours of social norms and egoistic tendencies (Glazer & Konrad, Reference Glazer and Konrad1996). Underlying these behaviours is the principle of reciprocity, social obligation, and conformity to community values (Andreoni, Reference Andreoni1990; Levi-Strauss, Reference Levi-Strauss1971, pp. 53–67). Consistent with similar findings, the outcomes align with a strong community influence and counter obligation on the giver and receiver to reciprocate one’s generosity within the “community of participation” (Levi-Strauss, Reference Levi-Strauss1971, pp. 53–67; Wolff, 1950).

“Giving back” embodies an inherent altruistic inclination characterised by reciprocity, interpersonal connections, and national identity (Brayboy et al., Reference Brayboy, Fann, Castagno and Solyom2012). In this study, individuals desiring to contribute to their community demonstrate autonomy and self-determination, acknowledging their privileged position and civic responsibilities (Salis Reyes, Reference Salis Reyes2019). They perceive “giving back” as an attribute that brings personal fulfilment and experiences a dualism of control and autonomy. While considering themselves privileged, they also recognise associated responsibilities (Reyes & Nicole, Reference Salis Reyes2019).

This study revealed the integrated impact of religion on giving behaviours. The findings indicating that Muslims exhibit a higher propensity to donate money compared to Christians are consistent with previous research, suggesting that within Islam, solicitation mechanisms effectively stimulate contributions (Austin, Reference Austin2013; Hoge & Yang, Reference Hoge and Yang1994; Smith, Reference Smith2017; Zaleski et al., Reference Zaleski, Zech and Hoge1994). In a country where over 90% of the population adhere to a religious faith (GSS, 2021b), religion significantly influences charitable giving by providing a moral and ethical framework, promoting altruism and empathy, institutionalising giving practices, nurturing community cohesion, and offering the promise of spiritual rewards. These influences collectively mould the charitable behaviours of individuals and communities, making religion a formidable force in philanthropy across cultures and societies.

As internalised and intrinsic responses, emotions encompass a spectrum of reactions to giving, including empathy, gratitude, happiness, altruistic joy, satisfaction, a sense of connection, and hope. When individuals develop an emotional connection to a cause, they are more inclined to contribute financial resources, time, or other support to address that cause or change an undesirable situation. The results of this study show that emotions play a significant role in motivating individuals to volunteer their time for the welfare of others and their community. For instance, participants’ emotions such as sympathy, pity and empathic concern signify altruistic (other-oriented) motivation to help others in distress (Piliavin et al., Reference Piliavin Dovidio, Gaeitner and Clark1981). Similarly, emotions such as happiness, excitement, satisfaction, relief, and fulfilment are from acts of generosity. These findings corroborate prior research associating volunteering with enhanced life satisfaction and reduced depression (Aknin et al., Reference Aknin, Norton, Dunn and Whillans2019; Piliavin et al., Reference Piliavin Dovidio, Gaeitner and Clark1981). This sense of well-being and positive self-perception is particularly evident when individuals experience all three basic psychological needs: a sense of autonomy and free choice, an opportunity to connect with the recipient, and the belief that their generosity can make a meaningful difference in the recipient’s life (Aknin et al., Reference Aknin, Barrington-Leigh, Dunn, Helliwell, Burns, Biswas-Diener and Norton2013).

Trust is an intrinsic motivating factor driven by self-awareness, personal values, and life goals. Individuals who give based on trust prioritise helping others as a moral imperative (Uslaner, Reference Uslaner2002). They give voluntarily and without external coercion for rewards or internal feelings of guilt or fear. Their confidence in the efficient use of their donations and contributions by the recipient stems from deeply internalised trust and a well-established reputation. In this study, participants indicated a willingness to donate without questioning the specific allocation of their donations, suggesting that a high level of trust is likely to cultivate sustained support for an organisation or a cause. In Ghana, people donate to organisations perceived as financially transparent and accountable, capable of efficiently using individual donated resources towards their intended objectives (Kumi, Reference Kumi2017).

Finally, this study identified individuals who hesitate to help others with money, gifts, or time. The intent and decision not to give is dependent on the individual’s financial and time constraints, existing or perceived trust relationship in the situation of need and the credibility or accountability of the recipient (Havens et al., Reference Havens, O’Herlihy and Schervish2006; Sargeant & Lee, Reference Sargeant and Lee2004; Wiepking & Breeze, Reference Wiepking and Breeze2012). This finding is consistent with the theoretical assumption of amotivation in the SDT, where the absence of motivation to give is associated with deficiencies in one or more of the three basic human needs: competence, autonomy, and belonging (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985; Seligman, Reference Seligman1975),

Conclusions

The study’s findings highlight the intricate dynamics influencing giving behaviour, where external and internal factors intersect. While social norms and egoistic motives may motivate charitable behaviour, they may also be tempered by individual characteristics such as age, gender, and household size, which vary significantly across demographic groups and contexts. This underscores the importance of comprehensively understanding charitable actions. While the motivation to give is not unique, finding the right combination of controlled and autonomous motivations in an environment that fosters trust, emotional connection, and a sense of personal identification with the cause or organisation can result in sustained and increased giving. Thus, further investigation into giving behaviours across Africa is imperative to inform effective community development and philanthropic strategies.

This study also shows that individual giving behaviour can be transitional, influenced by factors ranging from lack of motivation to intrinsic drives and responsive to social and environmental cues. This suggests the need for further studies building on the theoretical limitations of this research and the broad application and possibilities within the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to explore and deepen the understanding of giving behaviours in the African context.

This study enriches the literature on individual philanthropy by identifying key determinants of giving behavior in Ghana. It emphasises the need for broader African research to inform strategic philanthropic endeavours and community advancement initiatives.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. This article is part of a PhD research which was partially funded by the University of Witwatersrand.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no potential conflict of interest.