Introduction

On March 10th, 2020, Guatemala’s Ambassador to the UN notified the UN Secretary General that Guatemala declared a national state of emergency due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Guatemala planned to restrict the freedom of assembly, freedom of demonstration, and the freedom of movement. Through this derogation notification, Guatemala alerted the UN to its intent to violate fundamental rights protected by core human rights treaties that it had ratified. Generally, treaty noncompliance is condemned by the UN and its treaty bodies. However, Guatemala’s notification of rights violations was actually required by the treaty it was planning to violate. Article 4, paragraph 3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) requires member states to submit a derogation informing the UN of the inability to comply with human rights obligations during emergencies. In doing so, Guatemala was the first of many states to derogate from human rights law during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers have found that states that derogate do increase their likelihood of imposing rights restrictions such as freedom of movement and freedom of assembly showing that the rights derogators do follow through with the stated plans of select rights restrictions during crisis (Chaudhry, Comstock and Heiss Reference Chaudhry, Comstock and Heiss2024).

Increasingly, international relations and legal scholars have studied the legal nuances surrounding human rights treaty commitments (von Stein Reference von Stein2018; Comstock Reference Comstock2021). Following commitment, states can legally adjust, or qualify their commitment (Neumayer Reference Neumayer2007). Derogations are one legal means for states to adjust their commitment after ratification. Other legal actions drawing recent scholarly attention include objections and reservations (Eldrege and Shannon Reference Eldredge and Shannon2021; Zvobgo, Sandholtz and Mulesky Reference Zvobgo, Sandholtz and Mulesky2020). A state’s ability to temporarily suspend legal obligations is determined by treaty design decisions made during negotiations and drafting (Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal1998; Galbraith Reference Galbraith2013). Some international law allows for the relaxation of legal obligations during times of domestic emergencies. This is of particular importance for human rights law as “human rights are often the first casualties of a crisis” (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011: 673). Research findings support this concern, indicating that derogations can be associated with worsening human rights practices (Keith and Poe Reference Keith and Poe2004; Richards and Clay Reference Richards and Clay2010; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2013; Comstock Reference Comstock2019) and the potential erosion of democracy (Lührmann and Rooney Reference Lührmann and Rooney2021). Derogations and international human rights law have drawn recent attention during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Helfer Reference Helfer2021; Lebret Reference Lebret2020). The focus has centered on the legality of derogations and arguments pertaining to when, how, and to what extent states should make use of derogations during emergencies. Additionally, human rights scholars have examined whether issuing derogations impacted rights outcomes (Chaudhry, Comstock and Heiss Reference Chaudhry, Comstock and Heiss2024) and whether democratic backsliding states were more likely to abuse derogations during the pandemic (Comstock, Heiss and Chaudhry Reference Comstock, Heiss and Chaudhry2025).

What we do not know fully is what explains when and why states issued derogations to international human rights law during the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, when did states see the pandemic as an international crisis warranting derogation from human rights obligations? As Helfer (Reference Helfer2021) notes, states have had ‘sharply divergent responses’ to international human rights law derogation even when they are parties to the same international law and confronting similar threats (21). The COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique case to study for derogations given the global scope of the crisis. Prior human rights treaty derogation studies concentrated on natural disasters, civil or interstate wars and/or other domestic political turmoil as motivating circumstances for human rights treaty derogations (Keith and Poe Reference Keith and Poe2004; Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2013). Public health research studying disease outbreaks and other health emergencies does not tend to analyze derogations rather focusing on separate travel and trade restrictions (e.g., Worsnop Reference Worsnop2017).

This article investigates the determinants of human rights treaty derogations during COVID-19. I argue that states looked to global signals of COVID-19 pandemic severity when deciding to derogate. Given the unique scale and spread of the pandemic, states were influenced by global responses to the emergency as they formed assessments of potential domestic risks. WHO legitimacy, issue framing and information provision through its formal responses shaped the narrative of the pandemic as a high-risk situation requiring global collaboration. This positioned the WHO as the legitimate source of authority and guidance during the pandemic. WHO framing shaped how states defined crisis, shifting their risk assessment from the domestic to global level. The more attention that the WHO placed on the pandemic and communications it issued about it, the more severe states believed it to be. States then looked to their toolboxes of how to mitigate spread and issued derogations when strategies impeded human rights obligations. The WHO issued 73 statements about COVID-19 by the time Guatemala derogated on March 10th, compounding the information and severity signaled about the virus. While earlier studies of derogation emphasized domestic variation in explaining derogation submission, I highlight the importance of international level factors in shaping derogation behavior. To test this argument, I study the determinants of UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) derogations and examine country-day data from January 2020 to February 2021 including national and international crisis measures as possible explanations. Introducing a novel data collection of formal WHO responses during the pandemic, I find that the more the WHO responded to and issued advice about the pandemic, the more likely states were to submit ICCPR derogations. This finding supports the argument that international measures, and the WHO response in particular, informed state derogation responses during the pandemic. The derogations acted as a means to mitigate the domestic spread of the virus and were used as a tool when states received signals and information provision from the WHO that the virus was a serious public health emergency. Domestic factors such as rights recognition, prior derogation behavior, and legal tradition all also helped to explain COVID-19 derogation behavior.

The main contributions of this study are threefold. First, this research extends the examination of human rights treaty derogations to the COVID-19 pandemic. So far, there has not been a systematic, empirical analysis of COVID-era derogation submissions, nor an assessment of how global public health emergencies situate within derogation behavior. Second, this study builds our understanding of how international organizations and international crisis measures matter as states assess domestic level emergencies. There has been much discourse about the credibility and legitimacy of international and domestic institutions during the pandemic. This study addresses how governments responded to messaging from the predominant global institution on public health during a crisis. More broadly, it contributes to our understanding of when states draw on flexibility measures within international law, and how, specifically states respond legally to a global emergency. Third, the study introduces accessible WHO COVID-19 public response data the author collected, which may be useful for future studies of the WHO pandemic actions.

The article begins with an overview of treaty derogations and ICCPR derogation trends. The next section introduces the argument about WHO legitimacy, issue framing and information provision through formal guidance during the pandemic. Then, I briefly review existing literature on derogations, drawing testable hypotheses from past studies applied to the COVID-19 pandemic. After describing the quantitative analysis and variables used in the study, I discuss the results of country-day level data during the COVID-19 pandemic. I find strong support for the argument that global crisis measures were significant for ICCPR derogations while domestic crisis measures generally were not. I find that the more that the WHO issued formal responses and statements, the more likely states were to derogate. While other domestic level factors such as prior derogation behavior mattered, the domestic crisis-related measures generally did not. I conclude by situating the findings within existing work and calling for a broader study of the role of international measures during crises.

Derogations and international law

Derogations are a type of treaty provision that allow states to selectively remove treaty obligations during domestic emergencies. They have been described as ‘escape clauses’ as well as a ‘technique of accommodation’ (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011; Higgins Reference Higgins1976). A treaty must include a specific derogation clause and states must have ratified the treaty to submit derogations. The ICCPR, the American Convention on Human Rights, the Arab Charter of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms allow states to derogate during emergencies. In doing so, international and regional human rights law places the interpretations of emergencies at the domestic level (Criddle Reference Criddle2014: 8). Domestic regime type has been found to matter with derogations found to be made most frequently by democracies (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011). “They enable democratic governments to signal to domestic audiences that rights suspensions are necessary, temporary, and lawful” (Helfer Reference Helfer, Dunoff and Pollack2012: 189). However, states must formally justify derogations and the international level remains involved. The Human Rights Committee (HRC) does read, interpret and monitor derogations submitted to the ICCPR (McGoldrick Reference McGoldrick2004: 380).

Allowing derogations is one way to incorporate flexibility into international legal design. Flexibility measures are generally understood to increase treaty participation through ratification (Schabas Reference Schabas1996; Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal1998). Reservations famously were allowed with the Genocide Convention to increase participation in an important legal area (Klabbers Reference Klabbers and Ziemele2004). The benefits of flexibility measures are documented across other treaty issue areas as well (Kucik and Reinhardt Reference Kucik and Reinhardt2008). However, as Helfer (Reference Helfer, Dunoff and Pollack2012) cautions, flexibility mechanisms’ use can diverge from what the treaty designers had intended (190). Differing from reservations, derogations are time limited. Additionally, states are expected to justify the suspension of treaty obligations and require an emergency for application. States submitted over 1500 derogations to the UN’s multilateral treaties over the past 75 years,Footnote 1 although there has been great variation in the justifications and details submitted (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011; Helfer Reference Helfer2021). While some states submit detailed, multipage explanations about the type of emergency, specific subnational locations impacted and the time duration of the derogation, other states submit a sentence or two only notifying the UN that a derogation has been submitted.

Though states have been allowed to submit derogations to applicable treaties for decades, the frequency of state usage has changed over time. Hollis (Reference Hollis and Hollis2014) writes that derogations have become a more regular feature of treaty-making, particularly in human rights and economic treaties (731). Despite several analytical studies and a range of commentaries, there remains a need “to consider when and how states actually exercise the formal and informal flexibility mechanisms available to them” (Helfer Reference Helfer, Dunoff and Pollack2012: 191).

Derogations in design: including derogations in the ICCPR

The ICCPR is the primary international human rights treaty that allows derogation submission. During treaty development workshops held between 1947 and 1952, ICCPR negotiators debated the inclusion of an article that allowed derogation use. The United Kingdom introduced the proposal. The flexibility discussion first centered on concerns about state ability to meet treaty obligations during times of war (United Nations 2003: 817) and acknowledged that natural disasters “almost always justified a State derogating from some, at least, of the rights in the covenant” (Bossuyt Reference Bossuyt1987: 86). Opposition arguments, notably from the United States and the Netherlands, preferred general limitation clauses over more specified derogations. However, negotiators worried that if derogations were not allowed, states would suspend obligations to the entire treaty during wartime without formal notice.Footnote 2 France argued derogation clauses should not be limited to wartime. Its representative noted there “were cases when States could be in extraordinary peril or in a state of crisis, not in time of war, when such derogations were essential.”Footnote 3 Numerous states expressed concern that if the wartime requirement was removed, it would be extremely difficult to define and regulate what constituted a ‘public emergency’ (United Nations 2003: 818) sufficient for derogating from human rights. A final compromise in 1952 included that the emergency must ‘threaten the life of the nation’ and included a formal submission process informing all states that were party to the treaty.Footnote 4 Justification requirements were included “since the use of emergency powers had often been abused in the past, a mere notification would not be enough. The derogating State should also furnish the reason by which it was actuated” (Bossuyt Reference Bossuyt1987: 97). Thus, the scope of when derogation could occur was expanded but the process was more focused.

The final version included in ICCPR Article 4 details the derogation process:

In time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed, the States Parties to the present Covenant may take measures derogating from their obligations under the present Covenant to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not inconsistent with their other obligations under international law and do not involve discrimination solely on the ground of race, colour, sex, language, religion or social origin.

While the ICCPR includes the flexibility mechanism of derogations, the treaty goes on to clarify that some rights are non-derogable, meaning that there is no recognized justification for violating some human rights. Article 4(1) stipulates that derogation must be ‘to the extent strictly required’. HRC General Comment 29 (2001) reinforces that the more modern interpretation also is that derogations must be limited to what is strictly required by the emergency. The General Comment also specified additional limits to derogations. “The fact that some of the provisions of the Covenant have been listed in Article 4 (2), as not being subject to derogation does not mean that other articles in the Covenant may be subjected to derogations at will, even where a threat to the life of the nation exists” (HRC 29 2001: 3). The General Comment and the ICCPR text itself make clear that although derogations give legal flexibility to states during emergency, they are not intended to be a blanket authorization of rights violations.

During the ICCPR negotiations, public health crises were not specifically discussed as applicable emergencies.Footnote 5 However, states have cited public health reasons for submitting derogations. In 2006, Georgia submitted a derogation citing H5N1 virus (Avian Flu) as the justification for limiting freedom of movement, property rights and general constitutional provisions.Footnote 6 The HRC did not challenge this justification (Sommario Reference Sommario, Gestri and Venturini2012:328). Georgia’s derogation and interpretation of emergency were rare, however, with no other states referencing the Avian Flu for derogation justification during that outbreak.

Derogations in use: ICCPR derogation trends, 1966–2020

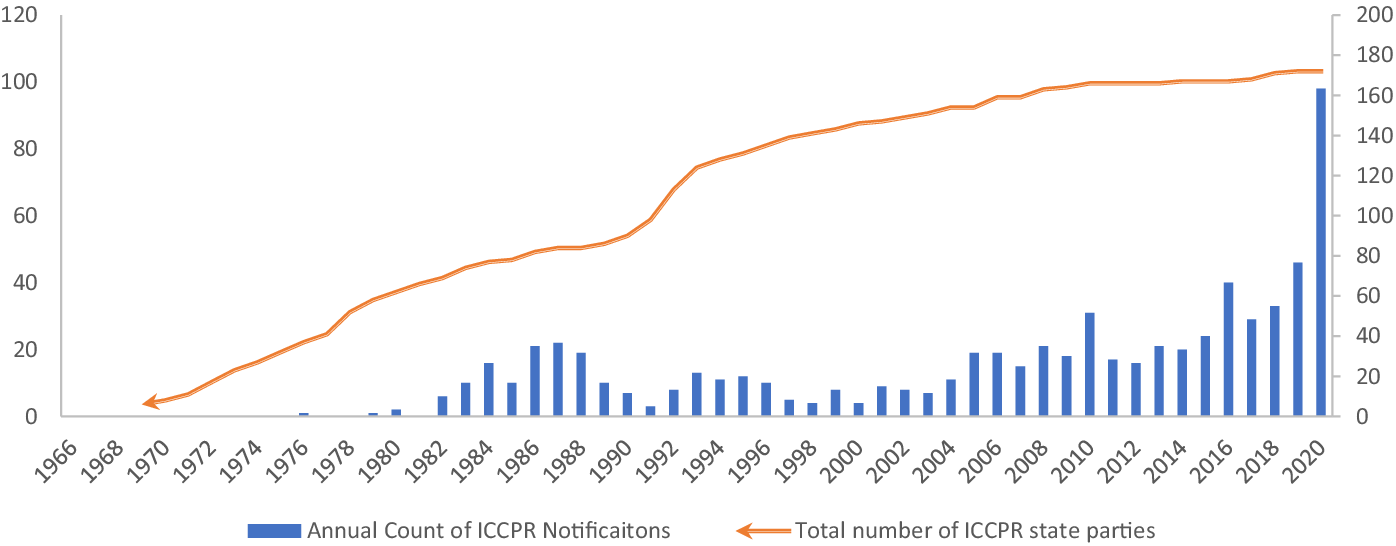

The first documented derogation submitted to the ICCPR did not occur until the treaty’s entry into force in 1976, 10 years after it opened for signature in 1966. Chile submitted the first ICCPR derogation in 1976 citing a domestic political siege “attempting to overthrow the established government” as justification. Since then, states submitted an increasing number of derogations to the ICCPR over time, indicating a growing trend to do so, as seen in Figure 1. While there were spikes during the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, since the mid-2000s, there has been a consistent increase in annual derogations submitted to the ICCPR. The highest number of derogations submitted in a single year was in 2020, more than twice those submitted in 2019, indicating a spike during COVID-19.

Figure 1. Total annual ICCPR derogations and total ICCPR state parties, 1966–2020.

Derogations during COVID-19: states and trends

As existing research indicates, most states do not end up submitting derogations during times of crises (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011). The same has been the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. Out of 173 states legally bound to the ICCPR and eligible to submit derogations, only about 20 states, or approximately 12%, derogated during the time analyzed in this study. However, we do see that some states that had never derogated from the ICCPR in its 70+ year history did so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 lists the states that derogated prepandemic and those that derogated during the pandemic. While there are a lot of commonalities, it is not a perfect overlap. This suggests that factors in addition to prior derogations may also explain COVID-19 derogations. It is important to understand when states use legal flexibility measures like derogations during times of crises to help understand when and why states view it as legally acceptable to violate human rights. It should be noted that, as in prior periods of derogation study, there is a clear regional trend in Central and South America of high frequency of derogations submitted. One possible explanation is a strong regional focus on human rights in Latin America (e.g. Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014: Sikkink Reference Sikkink1993). Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Farriss (Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011) noted this trend and Peru’s derogation behavior. Peru requires in its national constitution that derogations must be updated every 60 days, which encourages new derogation submissions (702). Won (Reference Won2025) noted that a large number of South American countries derogated through the regional American Convention on Human Rights.

Table 1. States issuing ICCPR derogations before and during COVID-19

There was variation in how and to what extent states recognized COVID-19 as a legal emergency. States could decide to declare a national level emergency and/or declare it internationally through actions like derogations. Won(Reference Won2025) descriptively discussed the domestic constitutional emergency provisions of states. The study revealed that a high percentage of states that derogated cited constitutional emergency provisions and the author posited that these states may have equated derogations as an extension of their domestic procedures. Neither Won(Reference Won2025) nor this study provide in-depth analysis into domestic level decision-making related to national level emergency procedures during the pandemic, but this could be a valuable route for future research to examine how state governments understood derogations as situating with domestic constitutional provisions.

Argument: WHO legitimacy, information provision and issue framing

Existing explanations of derogating from international human rights treaties have not incorporated the framing of emergencies or the legitimacy of international organizations.Footnote 7 I argue that both are important for understanding the human rights treaty derogation during COVID-19. At the onset of the pandemic, there was a lack of clarity about the risks and long-term health outcomes related to the virus. These factors contributed to the increased importance of global issue framing. While states assessed the crisis and its risk to domestic populations, they looked to international expertise for guidance. The WHO framed the crisis as one of heightened importance and drew on its international legitimacy to disseminate information and advice to member states. States used WHO guidance to make calculated assessments of the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. The WHO information and guidance shaped whether and when states perceived the COVID-19 pandemic as a sufficient risk to warrant derogations intendent to mitigate its spread. Issue framing and guidance spread from the WHO to other international organizations, heads of state and into derogation justifications.

This section builds the argument of the role of the WHO in treaty derogations by discussing the historic background and leadership of the WHO in global health governance, detailing issue framing during COVID-19 and providing examples of the guidance and examples of heads of states and other leaders adopting WHO frames and deferring to their guidance. Embedded within this argument is a comparison of past pandemics when the WHO has recommended different guidance, resulting in a far reduced state propensity to derogate during them. To be clear, this paper does not argue that domestic level factors have no bearing on COVID-19 derogations, but that during this emergency, international factors uniquely mattered in ways they typically have not for derogations.

WHO history and leadership in global health governance

Since its creation in 1948, the WHO has been at the forefront of global health governance (Davies Reference Davies2008), establishing its institutional legitimacy in the area. In international relations, legitimacy is the “normative belief by an actor that a rule or an institution ought to be obeyed” (Hurd Reference Hurd1999: 381). The WHO drew on its legitimacy from the beginning of the pandemic, bringing with it the perception that its advice ought to be followed. “As the leader in global health-setting standards and policy options and in providing technical support across its 194 member states, the WHO shapes the public health response globally” (Wong and Wong Reference Wong and Wong2020). The WHO’s institutional legitimacy allowed it to shape perceptions of norms and guidance as ‘appropriate’ (Hurd Reference Hurd1999: 387).

While the WHO had not yet been created during the 1918 pandemic, one of the organization’s first activities in 1948 was the creation of a global influenza surveillance network, now known as the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). In 1950, an Expert Committee on Influenza was established at the WHO with the goal of advising member states, coordinating surveillance and forecasting epidemics (Kitler, Gavinio, and Lavanchy Reference Kitler, Gavinio and Lavanchy2002: 5). These institutional steps established the WHO as the leading coordinator around global outbreaks. In pandemics that followed, the WHO understood its role to “continuously provides information to health authorities, the media, and general public about … recommendations” including “informing national health authorities” and “developing proposals to help guide national policy makers” (WHO 1999: 8). It did so during the 1957–1958 H2N2, the 1968 H3N2, 2009 H1N1 and other more recent outbreaks.Footnote 8

Across these pandemics and outbreaks, the WHO has generally guided recommendations, distributed scientific studies and directed states. As Abbott and Snidal (Reference Abbott and Snidal1998) argue, international organizations centralize collective activities and offer administrative functions such as information provision and formalized processes. The WHO acted as a centralizing organization prior to and during the pandemic through its information distribution. In 2005, the International Health Regulations (IHR) increased authority to the WHO during disease outbreaks, namely empowering the WHO to make “real-time recommendations to states about how to respond in a given outbreak” (Worsnop Reference Worsnop2017: 375). Generally, the WHO has taken a conservative approach concerning travel restriction recommendations. Most, but not all, states followed the WHO guidance against general travel restrictions. During these times, we see that very few, if any, states submitted derogations to the ICCPR. Table 2 compares WHO recommendations and derogation activity across notable pandemics since the 1950s.

Table 2. WHO travel restriction recommendations and state derogations, 1957–2020*

* WHO recommendation information comes from the WHO website as well as PR Saunders-Hastings, D Krewski, ‘Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission’ (2016) 5 (4) Pathogens 66. https://doi.org/10.10.3390/pathogens5040066 and Y Trotter, Jr., FL Dunn, RH Drachman, DA Henderson, M Pizzi and AD Langmuir, ‘Asian Influenza in the United States, 1957–1958’ (1959) 70 (1) American Journal of Epidemiology, 34–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120063.

† Made between January 2020 and February 2021.

The WHO has consistently erred against recommending travel bans and barriers, opting for lesser advisory guidelines. On March 15, 2003, the WHO issued travel advice that was against a travel ban but offered guidance for individuals with SARS symptoms not to travel.Footnote 9 On April 2, 2003, the WHO recommended the general travel advise that non-essential travel be postponed and on May 23, 2003, the WHO removed that recommendation.Footnote 10 During the 2009 H1N1 spread, the WHO recommended against travel barriers and restrictions to stop the spread of disease. Most states followed the WHO recommendations regarding travel restrictions, although some democracies with weak infrastructure (Worsnop Reference Worsnop2017) or nationalistic governments (Worsnop Reference Worsnop2025) went against guidelines imposing restrictions In the year surrounding the onset of H1N1, only one ICCPR derogation was issued citing the virus and a public health emergency.Footnote 11 Guatemala issued a derogation citing H1N1 and a public health emergency on 20 May 2009.Footnote 12 There was no reference to WHO guidance during that pandemic. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the WHO declared West Africa a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and recommended that exit screenings be conducted at airports and land crossings (Rhymer and Speare Reference Rhymer and Speare2017). The WHO did not recommend banning travel (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Brown, Alvardo-Famy, Bair-Brake, Benenson, Chen and Demma2016). While states submitted 44 ICCPR derogations between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2015, none of them cited the Ebola virus or public health emergencies. The derogations pertained to natural disasters and domestic political turmoil.

WHO information provision, issue framing, and credibility during COVID-19

Though most governments’ credibility was questioned during the pandemic, the WHO received mostly positive assessments.Footnote 13 This can be attributed, at least in part, to the perceptions of WHO institutional legitimacy concerning global health emergencies. Despite noted missteps, political controversy and the threat of US withdrawal, the WHO maintained mostly supportive public assessments. Most citizens do not hold consistent and well-developed attitudes toward international organizations (Dellmuth Reference Dellmuth2016); when they do, they differ from elites (Dellmuth et al. Reference Dellmuth, Scholte, Tallberg and Verhaegen2021), and elite and media communication influence individual level attitudes. Elites are more likely to communicate support for international organizational legitimacy during political events that threaten international security (Schmidtke Reference Schmidtke2019). The COVID-19 pandemic threatened states’ public in a way that may have triggered similar support and legitimizing during the crisis. Trust in the WHO mattered in shaping public health decisions during the pandemic even for those critical of it (Bayram and Shields Reference Bayram and Shields2021). Polarized domestic politics during a crisis can actually increase the chances the governments adopt policy recommendations from international organizations. Fang and Stone (Reference Fang and Stone2012) argue that this dynamic is what enabled WHO information being distributed during the SARS health crisis during 2002–2003.

Positioned as the legitimate authority on global health, the WHO was able ‘set the stage’ and frame the COVID-19 pandemic. Issue framing is an important concept in political science. Issue frames are “alternative definitions, constructions, or depictions of a policy problem” (Nelson and Oxley Reference Nelson and Oxley1999: 1041). How issues are framed, or viewed and understood, has significant effects on public opinion, policy decisions and allocation of resources. Issue framing is important for targeted campaigns and political communication more broadly. Leaders and organizations use frames as ‘organizing themes’ and as a ‘focal lens that sensitizes the public to specific elements” (Mintz and Redd Reference Mintz and Redd2003: 195). Issue framing has impacted a broad range of international areas spanning from international trade (Hiscox Reference Hiscox2006), sexual violence (Crawford Reference Crawford2013) and human rights issues in and outside of the UN (Charnysh, Llyod and Simmons Reference Charnysh, Llyod and Simmons2015). International organization statements frame issue areas and can influence public opinion during crises because of the legitimacy and expertise that IOs convey (Chapman Reference Chapman2009). The WHO framed the COVID-19 pandemic as one of heightened importance and of global interconnectedness.

The WHO framed the COVID-19 pandemic through information provision. One of the three primary objectives of the WHO has been categorized as providing the global community information about diseases, outbreaks, prevention and other global health trends (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2002). Although during some stages of its existence, the WHO was described as “where good ideas go to die” (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2002: 1108), since then there has been a concerted effort to minimize corruption and maximize efficiency. The WHO provided information to government officials, heads of state and the general public through private meetings, press briefings, conferences and reports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the reports, information and data the WHO provided on the COVID-19 pandemic, it framed the pandemic as a global crisis that needed global responses.

On January 30, 2020, the WHO formally declared that the coronavirus outbreak had reached the highest level of global health alarm, a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).Footnote 14 Upon releasing the PHEIC designation, the WHO Emergency Committee called for the “need for global solidarity” and “a global coordinated effort to enhance preparedness in other regions of the world.”Footnote 15 Both learning from experience delaying the PHEIC designation for the 2018 Ebola outbreak and recognizing the extreme speed at which COVID-19 spread, the Emergency Committee declared COVID-19 a PHEIC on the second day of meetings. This compared with a year’s delay with Ebola (Durrheim, Gostin and Moodley Reference Durrheim, Gostin and Moodley2020). The speed of the designation signaled a high stakes emergency, which the WHO Director-General made clear.

…I am declaring a public health emergency of international concern over the global outbreak of novel coronavirus. The main reason for this declaration is not because of what is happening in China, but because of what is happening in other countries… the only way we will defeat this outbreak is for all countries to work together in a spirit of solidarity and cooperation. We are all in this together, and we can only stop it together.Footnote 16

The statement makes clear that the emergency was one of great severity, it had spread, and that international cooperation was needed. On the same day, the WHO organized a member-state briefing. The Director-General emphasized the WHO role of providing guidance and information.

We are also increasing our communications capacity to counter the spread of rumours and misinformation, and ensure all people receive the accurate, reliable information they need to protect themselves and their families.Footnote 17

The WHO recommended against general bans of international travel during COVID-19 beginning in January 2020. In February 2020, the WHO relaxed its language and recommended quarantine for travelers. By the end of February 2020, the WHO acknowledged:

However, in certain circumstances, measures that restrict the movement of people may prove temporarily useful… Travel measures that significantly interfere with international traffic may only be justified at the beginning of an outbreak, as they may allow countries to gain time, even if only a few days, to rapidly implement effective preparedness measures. Such restrictions must be based on a careful risk assessment, be proportionate to the public health risk, be short in duration, and be reconsidered regularly as the situation evolves.Footnote 18

Although not exhaustive, we see during the pandemics identified in the last 70 years in Table 2 that states seem to respond to the guidance of the WHO when it comes to travel restriction recommendations. When the WHO did not recommend general travel restrictions, states did not derogate citing a public health emergency. When the WHO acknowledged that travel restrictions and quarantines could be prudent during COVID-19, we see states derogating citing a public health emergency as they restrict assembly and movement of their peoples. The WHO did not specifically address domestic travel restrictions, although it did discuss cities and subnational areas of heightened COVID-19 outbreak activity in its recommendations. The framing of COVID-19 severity paired with a change in approach to travel restrictions coincided with a change in state derogation behavior during COVID-19 compared with prior global pandemics.

WHO responses: a look at the guidance and information

The WHO actively served the role of providing information and guidance during the pandemic, issuing almost 300 public responses including specific guidance, recommendations and reports from January 2020 to February 2021. The responses continued to frame the pandemic as a global, interconnected one of high risk.

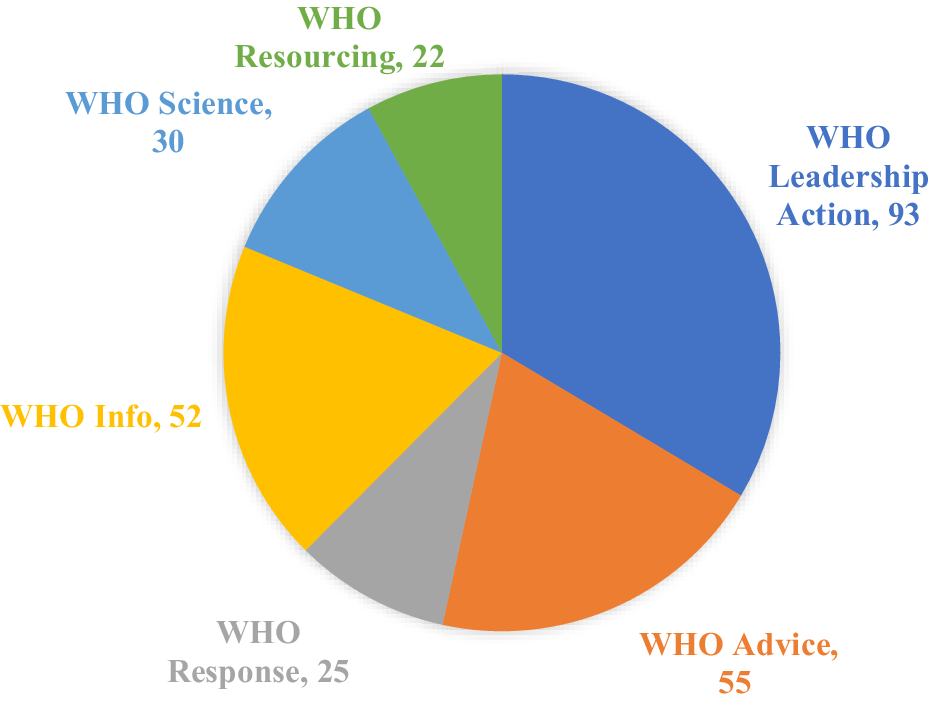

The WHO categorized its written responses into six types: resourcing, science, information, leadership action, response and advice. For the purposes of this paper, I total them together. Figure 2 depicts the breakdown of WHO response by type. Leadership Actions comprised the largest amount followed by advice and information. In the Appendix, find illustrative examples of what brief releases entailed for each response type. Typically, the responses had links to longer press releases and any scientific reports or guideline reports referenced. Each response communicates different aspects of scientific research, practical guidance for the public, funding sources and programs or WHO actions related to COVID-19. The formal responses convey action taken and knowledge gained about COVID-19. Received by states and their leaders during a time of global health crisis, these responses shaped and guided assessments of risk.

Figure 2. WHO responses by category, January 2020–February 2021.

The WHO’s empirical data on COVID-19 was presented in a publicly accessible WHO COVID-19 Dashboard website. The release and updating of this data on case counts and death counts across the global provided information and communicated the level of the crisis to the general public, policy makers, and news outlets during the pandemic. Additionally, the WHO provided publicly released data on COVID-19 case and death counts which was used by major outlets like the New York Times to report global COVID-19 information.

Global responses to WHO during COVID-19

The UN, of which the WHO is a part, acknowledged WHO authority and adopted its framing of the interconnected and global scope of COVID-19. In his first statement on COVID-19 on March 13, 2020, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres stated that “No country can do it alone. More than ever, governments must cooperate.” Guterres repeatedly emphasized in early speeches the connectedness, shared responsibility and global scale of the pandemic. “A pandemic drives home the essential interconnectedness of our human family. Preventing the further spread of COVID-19 is a shared responsibility for us all.”Footnote 19 Addressing the G-20 during an emergency virtual summit on March 23, 2020, Guterres framed COVID-19 as a “global health crisis (that) spreads human suffering.” He clarified that the pandemic was not like the banking crisis or prior crises but required “a response like none before… (that would) demonstrate solidarity with the world’s people, especially the most vulnerable.” Guterres deferred to the authority of the WHO and advised the G-20 to be “guided by the World Health Organization.”Footnote 20 This framing drew from and reinforced the WHO’s assessment of COVID-19 and buttressed the WHO’s international legitimacy.

World leaders acknowledged WHO authority and echoed severity and global framing. China’s President Xi Jinping stated

We should enhance solidarity and get through this together. We should follow the guidance of science, give full play to the leading role of the World Health Organization, and launch a joint international response … Any attempt of politicizing the issue, or stigmatization, must be rejected.Footnote 21

German Chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel expressed her support for the WHO and coordination between Germany and the WHO on a new research hub.

The current Covid-19 pandemic has taught us that we can only fight pandemics and epidemics together. The new WHO Hub will be a global platform for pandemic prevention, bringing together various governmental, academic and private sector institutions. I am delighted that WHO chose Berlin as its location and invite partners from all around the world to contribute to the WHO hub.Footnote 22

Most leaders who criticized some ‘early missteps’ of the WHO during COVID-19 worked to expand and stabilize the WHO funding and to strengthen international cooperation around the WHO and pandemic responses.Footnote 23 Other leaders explicitly criticized the WHO and China, although these leaders were in the minority.Footnote 24 When the WHO was under scrutiny, there was no other clear global public health leader to step in and offer consistent alternative information and guidance. Strikingly, perceived international organization problems can actually increase the trust of developing and transitional states (Torgler Reference Torgler2008). The WHO’s institutional legitimacy was ‘sticky’, embedding norms, expectations and authority even in times of critique (Cornell and Davis Reference Cornell and Davis1996).

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson articulated this support in his comments to the United Nations on September 26, 2020, situating the WHO as not perfect, yet the global face of global public health.

And so the UK supports the efforts of the World Health Organisation and of my friend, Tedros, to explore the aetiology of the disease, because however great the need for reform, the WHO, the World Health Organization, is still the one body that marshals humanity against the legions of disease. That is why we in the UK – global Britain – are one of the biggest global funders of that organisation, contributing £340 million over the next 4 years, that’s an increase of 30%.Footnote 25

Further recognition of the WHO came through a call for an international pandemic treaty. On March 30, 2021, 27 world leaders came together and recognized “The COVID-19 pandemic (a)s the biggest challenge to the global community since the 1940s”Footnote 26 They call for a global pandemic to be “rooted in the constitution of the World Health Organization” to strengthen a multilateral response to future pandemics as no state can overcome a pandemic alone.

Global leaders’ response to the WHO during COVID-19 has been one acknowledging error yet still recognizing WHO legitimacy while looking to it as the global authority on public health. From this position, the response and direction of the WHO was important in signaling the severity of the pandemic. This framing and deference to WHO expertise extended to derogations states submitted. States specifically referenced the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO and its guidance in the derogation justifications. In a natural experiment of public confidence in the WHO before and after the COVID-19 pandemic across 40 countries, Guo et cal. (2022) found that overall confidence in the WHO increased from 29.10% before the pandemic to 75.5% after the pandemic.Footnote 27 Guatemala, the first state to derogate during COVID-19, for example, explicitly drew on WHO emergency framing when derogating, writing it was important, “in light of the announcement by the World Health Organization of the coronavirus epidemic (COVID-19) as a public health emergency of international concern.”Footnote 28 This specifically drew on the risk category the WHO assigned the virus to, as part of Guatemala’s calculation for needing to restrict rights of assembly and movement.

Hypotheses

From the recognized legitimacy of the WHO and the continued adoption of its crisis frames, I expect that WHO activity and framing influenced derogation behavior as states assessed pandemic risk levels and the global scale of the crisis. Resultant of the WHO framing of a global, interconnected crisis, I expect that states respond to global health measures of the COVID-19 pandemic.

H1: The more the WHO communicated about the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic through its global cases and death data publications, the more likely a state will be to derogate.

H2: The more attention the WHO brings to the COVID-19 crisis, the more likely a state will be to derogate.

H2a: The more the WHO framed the COVID-19 pandemic as a crisis requiring action, the more likely a state will be to derogate.

H3: The more confidence states had in the WHO, the more likely they would be to derogate.

Alternative derogation explanations applied to the COVID-19 era

Extant empirical studies of derogations focus primarily on domestic level emergencies (e.g., civil conflict or natural disasters) and domestic factors (regime type, former treaty behavior). International explanations are generally seen as bilateral punitive relationships (e.g., foreign aid). However, legal scholarship has long considered the applicability, legality and use of derogations (Green Reference Green1978; Mangan Reference Mangan1988). Political science includes derogations within a broader framework of treaty flexibility, although focused more often on reservations (e.g., Neumayer Reference Neumayer2007; Simmons Reference Simmons2009; McKibben and Western Reference McKibben and Western2020; Zvobgo, Sandholtz and Mulesky Reference Zvobgo, Sandholtz and Mulesky2020). This section draws on both derogation-specific well as broader human rights law research to generate testable hypotheses about derogation during COVID-19.

Most studies of international law find that regime type is an important indicator of human rights law participation. Democracies tend to engage more with human rights law than nondemocracies through commitment (e.g., Hathaway Reference Hathaway2007; Cole Reference Cole2009; Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Hill and Watson Reference Hill and Anne Watson2019; Krommendijk Reference Krommendijk2015) as well as flexibility measures (Neumayer Reference Neumayer2007; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Research specific to derogations also finds that democracies, especially those with strong rule of law, are more likely to derogate (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011). The expectation is that states with strong democratic institutions need to convince domestic audiences of the legality and legitimacy of suspending rights during emergencies. Derogations serve as a credible signal and buy leaders time during crises (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011: 681). Less democratic regimes are not expected to need the legal coverage derogations offer (683). Simmons (Reference Simmons2009) finds that to be the case with reservations as well. This argument does not draw expectations about why some strong democracies may be more likely to derogate than others, why some democracies never derogate or has it been extended to global crises.

H4: The more democratic a state is, the more likely it will be to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

States that are embedded in the international human rights regime from past legal behavior may be more likely to participate via derogations. Past human rights treaty ratifications explain future ratification behavior (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). The same has been found to hold true for derogations. States that derogate are more likely to do so again (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011). Richardson and Devine (Reference Richardson and Devine2020) write that states that do not derogate are ignoring procedure or international human rights law altogether, suggesting a disengagement with the legal mechanisms and expectations.

H5: If a state derogated previously, then it will be more likely to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Socialization arguments draw expectations that both regional (Simmons Reference Simmons2009) and global legal behavior (Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2005; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005) shape human rights treaty ratification. This could also be the case with human rights derogations during COVID-19. A socialization-driven argument would expect that as more states in a region or at the global level derogate, the norm becomes more established increasing other states’ likelihood of derogating during COVID-19.

H6: If more states in a state’s region (or globally) derogate during COVID-19, then a state will be more likely to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another expectation is that derogating reflects the severity of a state’s domestic emergency. Treaty drafters anticipated states would draw on derogations only during times of extreme domestic emergency. It is unclear from existing research if crisis severity can explain derogation behavior. However, research finds “Only a small number of treaty members that experience emergencies actually derogate – approximately 20 percent of eligible states in our sample” (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss, Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011: 695).

H7: If a state experiences an increase in domestic COVID-19 cases, then it will be more likely to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A state-control-driven explanation for derogations is that they are a rational state response to growing unrest about how the state is handling COVID-19. Following domestic emergencies, states are more likely to suppress opposition mobilization (Wood and Wright Reference Wood and Wright2016). During the COVID-19 pandemic, states confronted growing opposition to public-health policies. Derogations could be a calculated move to control government opposition.

H8: The more COVID-19 related unrest a state experiences, the more likely it will be to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research methods and data

I use a country-day unit of analysis to examine derogations, which allows the study of the rapid onset and unfolding of the pandemic. Analysis begins on January 3, 2020, when the WHO began systematically collecting COVID-19 case data, through February 18, 2021. This period covers 413 country-days in the onset of the pandemic across 190 countries resulting in approximately 70,000 observations for analysis. This study focuses on ICCPR derogations. A foundational international human rights treaty, the ICCPR “is the only universal of the three international human rights treaties with derogation provisions” (Neumayer Reference Neumayer2013: 4). Other treaties that do allow derogations are regional agreements that limit what states are able to submit derogations and do not hold a consistent policy of notifying other states of the actions (Neumayer Reference Neumayer2013: 4 ftnt).

I adopt the strategy of replicating the main structures of the formative political science study explaining derogations (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011. The authors use a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) Model to model the likelihood of the occurrence of derogation, clustered by country. GEE provides a “conservative yet efficient and unbiased estimate” (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011: 690; Zorn Reference Zorn2001). Instead of including polynomials or splines for past derogations, I include a dichotomous variable of past derogation behavior, which is discussed in more detail below. I include the most up-to-date data in the models given the current nature of COVID-19. If data is not available for the country-day level, I use the most recent year for data. For example, population, GDP and rights-related measures are from 2019 calculations. To test H3 and the potential relationship state views the WHO might have on derogation, I will use descriptive data. To the author’s knowledge, there was not a cross-national time series survey of confidence in the WHO during the pandemic that would vary on the daily, weekly or monthly frequency.

Dependent variable: ICCPR derogations

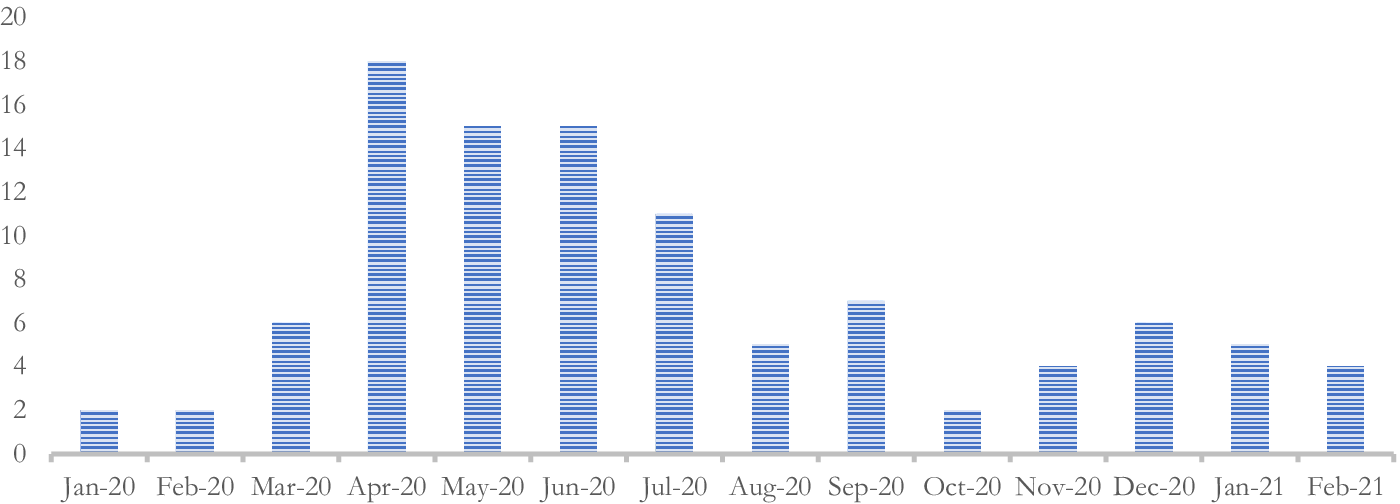

This paper introduces data on COVID-19 ICCPR derogations. The variable is coded as 1 on the date that the derogations were entered into the UN system and 0 for all other days. ICCPR derogation data comes from the United Nations Treaty Collection. Between January 2020 and February 2021, 102 derogations were issued by 23 states. Figure 3 depicts monthly totals. Although states can formally declare states of emergency without submitting derogations to international law, this study, like the earlier Neumayer (Reference Neumayer2013) and Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss (Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011) is concerned with explaining the timing of when states opt to use the legal tool of derogations to note that their domestic states of emergency have reached a point at which human rights obligations can no longer be met.

Figure 3. Monthly COVID-19 derogations January 2020–February 2021.

Independent variables

WHO responses

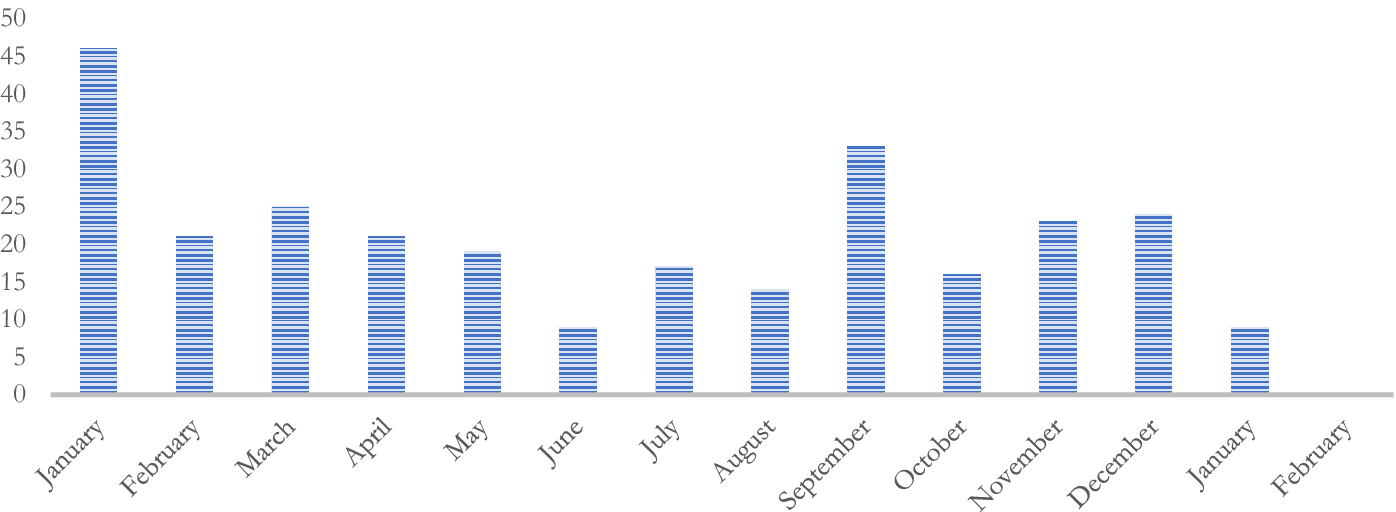

I include a novel measure of WHO Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. This variable is an original measure of how many public responses a day the WHO issued related to the COVID-19 pandemic. During the period of analysis, the WHO issued 277 responses. Figure 4 plots the WHO Responses by month. These responses include official reports, statements, guidance, declarations, scientific guidelines and published response plans. All these materials are publicly available through the WHO website and were produced during the pandemic with the intent of public dissemination and guidance. The author collected data from the WHO website to create this measure. The maximum WHO responses per day was 5, the minimum was 0 and the mean was .67 responses per day. Example responses are provided in the Appendix. A second variable of WHO Responses Cumulative is included to test the impact of all the WHO advice to see if there is a cumulative effect on derogations.

Figure 4. Monthly totals of WHO responses during COVID-19.

COVID-19 data

I include six COVID-19 related variables with data coming from the WHO. COVID-19 data tests whether the level of health concern communicated by the WHO via the release of empirical COVID-19 data contributed to states using the pandemic as a health emergency for a derogation. WHO data collection began January 3, 2020, and extended until February 18, 2021. The variables National COVID Cases and National COVID Deaths are count measures, in 1000s, of how many new cases or deaths are reported each day. National COVID Cases Cumulative and National COVID Deaths Cumulative are running counts, in 1000s, that total the national-level cases and national-level deaths as of that date. Global COVID Cases Cumulative is a running cumulative total, in 1000s, of all reported global cases. Global COVID Deaths Cumulative is a running count, in 1000s, of all reported global deaths.

Additional derogation variables

Past Derogators is a dichotomous variable that codes states that derogated from ICCPR obligations prior to the COVID-19 pandemic as 1 and all others as 0. Past derogating behavior during prior national-level emergencies may explain state propensity to derogate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thirty-seven states derogated from the ICCPR 554 times between 1966 and 2019 (list included in Table 1). The second two variables measure regional and global derogations during COVID-19 to test whether other states’ behavior influenced a state’s decision to derogate. Total Global COVID-19 Derogations is a running count of all derogations made to the ICCPR starting with January 2020. Total Regional COVID-19 Derogations is a regional level running count of all derogations made to the ICCPR starting with January 2020. WHO regions are used to classify states into regions. The WHO organizes states into six regions: Africa Region, Region for the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean Region, European Region, South-East Asia Region and Western Pacific Region.

Protest variables

I include two protest variables using data from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Global Protest Tracker database. Data is based on reported protests in local and national news sources. Protests is a count variable of how many antigovernment protests occurred that day in a state. During the period of analysis, there were 73 unique antigovernment protests reported. Although this measure is unlikely to capture all protest activity, those reported in local and national news outlets indicate that the state government was likely aware of the protests. COVID-19 Protests is a dichotomous variable indicating whether antigovernment protests were COVID-19 motivated. Almost half of the protests reported specifically were motivated by COVID-19 (30 of the 73 protests).

Democracy, rights and law

The 2019 Freedom House Civil Liberties and Political Rights measures for each state are included. These measures will test whether the rights practices in a state leading up to the pandemic influenced state derogation during the pandemic. Each measure is a rating of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of freedom and 7 the lowest level of freedom. Political Rights include fairness of elections, political participation and independent functioning of the government. Civil Liberties include freedom of expression and belief, freedom of assembly, rule of law and individual rights (Freedom House 2020).

The Rule of Law index from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) database measures the extent to which, in 2019, national level laws are transparent, independent, predictable, impartial and equally enforced along with to what extent government officials comply with the laws (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Krusell, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Olin, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Staton, Sundtröm, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2018: 232). The index ranges from 0–1 with 0 indicating a low level of rule of law and 1 a high level. Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss (Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011) argued that states with domestic courts that had oversight over the executive were more likely to derogate (675), making the Rule of Law measure well-suited to test this aspect of their argument.

A dichotomous measure of state-level legal tradition Civil Law is included, as a state’s legal tradition can influence participation in international human rights law. These are dichotomous measures of state-level legal tradition from Mitchell, Ring and Spellman (Reference Mitchell, Ring and Spellman2013).

Control variables

GDP and Population are included to control for state size and economic capacity. Both figures are from the World Bank Data and are 2019 numbers. GDP is in millions of US dollars and Population is in thousands of people. Models with logged measures are included in the Appendix. Both control variables have been included in prior studies of derogations to account for capacity, which may impact on a state’s ability to devote resources to legal teams, and so forth, which would focus on derogations (e.g. Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011).

Results

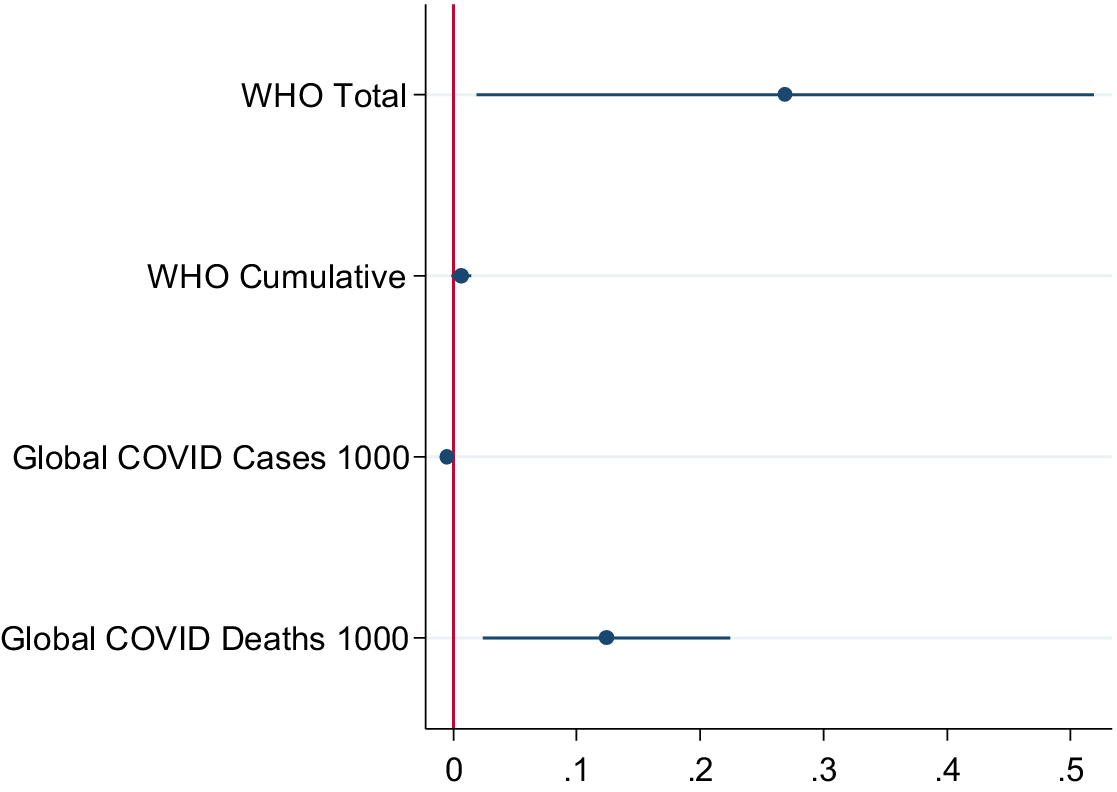

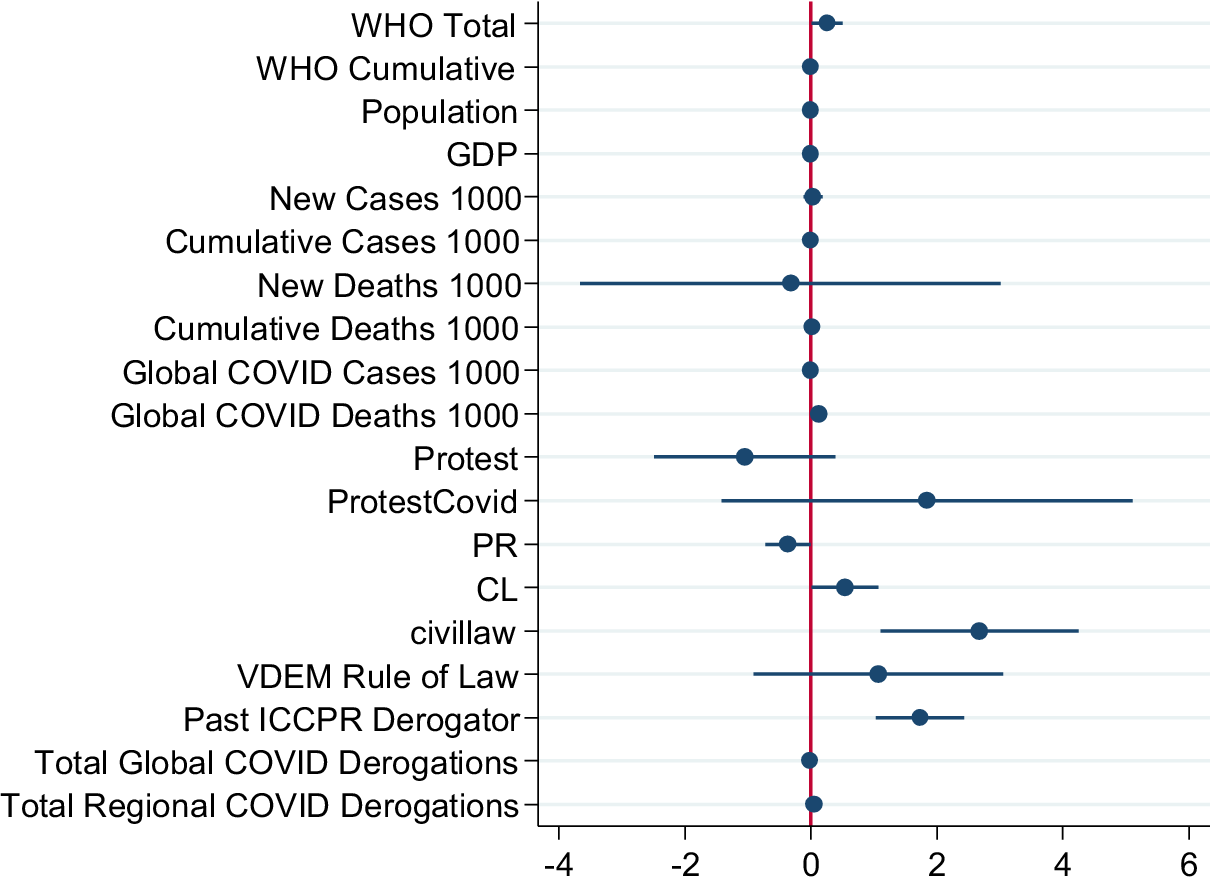

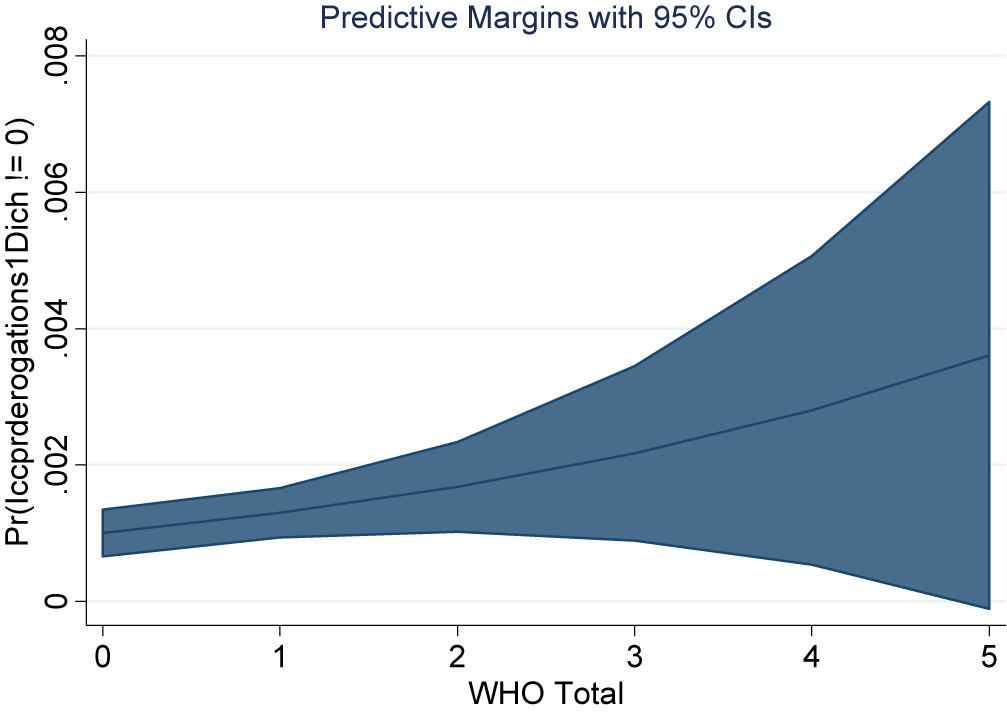

The results from Table 3 indicate strong support for the argument advanced here – that states looked to global measures and guidance of the pandemic severity when deciding to derogate from the ICCPR. Model 1 begins with global crisis measures, Model 2 separates out categories of WHO response actions, Model 3 includes the controls of GDP and populations, Model 4 includes domestic-level crisis measures, Model 5 includes measures of rights, democracy and law and Model 6 includes other derogation measures to complete the full model. Figures 5 and 6 plot the coefficients from Models 1 and 6 graphically displaying the results. Figure 7 plots the predictive margins of ICCPR derogation by WHO Response Total depicting the increased, although more varied, likelihood of derogating with more WHO responses.

Table 3. Global crisis measures and ICCPR derogation January 2020–February 2021

Note: Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .10.

Models run on Stata 14.2.

Figure 5. Plotted coefficients from model 1.

Figure 6. Plotted coefficients from model 6.

Figure 7. Predictive margins of ICCPR derogation by WHO response total.

Throughout each model, the global crisis measures were significant and positive determinants of ICCPR derogations. WHO responses and global COVID-19 deaths were positive and significant indicators of a state’s likelihood to derogate during the pandemic. When the WHO issued a Response, then the chances of a state derogating the ICCPR increased by about 30%. The WHO Cumulative Responses had a significant, but smaller impact on derogating. It is of note that the WHO Advice response, which provided specific guidance to states about COVID-19 behavior and policy, was the most impactful when actions were separated in Model 2. The significance did not remain in the models with additional variables, although they were robust when versions of Model 2 were run without the control variables of Regional COVID Derogations and Global COVID Derogations as well as versions run without the Global COVID Cases and Deaths variables. The finding that WHO Advice can influence states derogation behavior is indicative of the Advice actions drawing on specific learned behavior and information. For example, February 14, 2020’s WHO Advice Action read: “Based on lessons learned from the H1N1 and Ebola outbreaks, WHO finalised guidelines for organizers of mass gatherings, in light of COVID-19.” With every 1000 additional global deaths from COVID-19 each day, a state’s likelihood of derogating from the ICCPR increased by about 12%. This suggests that states were reacting strongest to the in-the-moment guidance and information released by the WHO and responding to the global severity of deaths when assessing domestic risks. Interestingly, global cases had a negative relationship with state derogation. This may indicate that states were especially receptive to death measures as a definitive measure of crisis. This also may be the case because, especially early in the pandemic, there was uncertainty about what factors increased the likelihood of death outcomes from COVID-19 infections.

Across the models, none of the domestic crisis measures were significant. New National COVID Cases, Cumulative National Deaths and Protest variables were all positive but did not reach the threshold of statistical significance in any model. This indicates that derogations were not likely shaped by domestic political unrest and were not significantly influenced by domestic COVID-19 cases or death rates. This study cannot speak on other domestic political relationships with derogations during the pandemic such as whether states used derogations to strategically repress groups during the pandemic.Footnote 29

The strongest predictors of COVID-19 derogations were past derogation behavior and legal tradition. If a state had derogated to the ICCPR before the pandemic, then it was about twice as likely to derogate during the pandemic. However, not all prior derogators did so during this period, and states that never derogated before did so during the pandemic. The significance of regional derogation totals and Civil Law Tradition point to the preponderance of states in Latin America to derogate. Most states in the region follow the civil law tradition and it was the region with the most clustering of derogations during COVID-19. These results support established findings in derogation and human rights law research (Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss Reference Hafner-Burton, Helfer and Fariss2011; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). However, these measures do not explain when during the pandemic a state decided to derogate; rather they explain an increased proclivity of these states to derogation behavior.

As expected from previous studies, rights and democracy measures were important indicators of derogation behavior. The Freedom House rights measures indicated that type of right mattered for derogations. The more the repressions of Civil Liberties a state had in the year prior to COVID-19, the more likely it was to derogate. The more the repression of Political Rights, the less likely a state was to derogate. Looking at the composition of these measures may help explain these divergent relationships. Civil Liberties includes freedom of assembly, which had been restricted during many national declarations of emergencies during COVID-19. The less recognition of these rights prior to COVID-19 may make states more willing to quickly rescind those rights in a time of emergency. Rule of Law was positive across all models, although did not reach the threshold of statistical significance. These findings indicate that democratic states still have some higher proclivity to submit derogations than nondemocracies. However, during COVID-19, a range of states derogated, suggesting that there is more to understanding derogation choices than democratic institutions alone.

Unlike previous emergencies, during the COVID-19 pandemic states looked to global signals of crisis when deciding to derogate from the ICCPR. The results indicate that states are expanding the scope and level they take into consideration when derogating from international law. States may see global emergencies unfolding and pre-emptively derogate from international law to protect the domestic population from COVID-19 spread. This lends support for the argument presented in this study. The framing of COVID-19 as a heightened crisis that was global and interconnected may have prompted states to look at the broader international level when assessing when to derogate from the ICCPR. Doing so at that point placed derogation as a preventative measure to avoid a global crisis coming home to the domestic level. This may explain why, for the most part, rising COVID-19 cases and deaths at home did not increase the likelihood of derogations. However, global COVID-19 deaths, seen as a manifestation of the severity and scope of the pandemic, may have motivated states to take the pandemic seriously and try to avoid the death toll at home.

To test H3, I draw on data from Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hu, Yuan, Zwng and Yang2022) who tracked a World Values Survey Question on public confidence in the World Health Organization during the early part of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Data was available across 40 countries. Of those 40 countries, nine submitted COVID-19 related derogations to the ICCPR.Footnote 30 While this is not a perfect test of the relationship between perceptions of legitimacy and derogation behavior, it can provide some insight into any trends. What I found is that there was not a clear correlation between a country’s confidence level in the WHO and the issuance of derogations. Guatemala had one of the lowest levels of confidence in the WHO (35%) although issued the highest number of derogations (18) in this sample. Countries with midlevel confidence like Romania, Chile, and Ecuador (50%–62%) all derogated as well as some countries with high levels of confidence in the WHO like Kyrgyzstan (73%) and Ethiopia (77%). Although this descriptive examination is not a causal test, we can see from this sample that confidence in the WHO alone did not explain derogation behavior. Further studies looking more closely at measures of trust, confidence and legitimacy would be very interesting and, very likely, insightful into derogation and international legal behavior during the pandemic.

Robustness checks

I undertook several additional tests of the robustness of the findings. Alternative model specifications were run (1) using COVID-19 case and death per capita variables to test the proportional influence of pandemic impacts, (2) lagging the WHO Responses Total variable to ensure that the causal direction was accurately being captured, (3) logging the population and GDP variables, (4) interacting WHO Responses Total with the Civil Liberties and Political Rights variables and (5) interacting WHO Responses Total with Rule of Law. These specifications did not change the results. Results were consistent with models presented in Table 1 and are included in the Appendix. Global measures of crisis remained important in explaining derogations, while domestic measures of crisis were not.

Conclusion

This article offered a detailed empirical study of state derogation from international human rights law during the COVID-19 pandemic. It extends prior derogation research specifically to the COVID-19 pandemic and a health crisis. Doing so builds our understanding of human rights treaty engagement and opting out of rights obligations. It also contributes to the growing legal dialog around the use and nature of derogations during the pandemic. The finding that states responded to WHO during the pandemic may shape how legal scholars view the appropriateness of derogations. I argued that WHO global level emergency framing and its institutional legitimacy were important for states when assessing domestic level risk and the need to derogate from the ICCPR. This was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. While some expected state institutional characteristics mattered for derogation such as prior derogation behavior, legal tradition and rights recognition, the timing was shaped by global emergency measures. COVID-19 was unique in that global factors shaped state derogation behavior in ways that had not been documented with past derogation behavior.

The findings have several implications for the broader study of derogations, emergencies, international institutions and international human rights law. First, international institutional signaling was most important in state decision-making to derogate from human rights treaty obligations. Despite criticisms and missteps taken by the WHO during the pandemic, leaders and governments appeared to generally take as credible signals the messaging that the WHO sent. Earlier derogation studies did not operationalize interconnectedness or scope of crisis when assessing emergencies and derogation. A reexamination of past derogations may benefit from including measures of whether disease outbreaks, conflicts or other crises extended beyond borders. The number of states involved in a conflict or affected by a natural disaster may broaden the perceived crisis and shape states’ likelihood to derogate. Second, the WHO played an important role in framing the crisis and disseminating information during the crisis. Studying how key international actors framed crises, along with their legitimacy, may be fruitful avenues for future research concerning states of emergency, derogations and human rights. The findings in this study speak directly to behavior and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, but we can draw questions from these findings to see how pandemic behavior might replicate or diverge during a future crisis or noncrisis time.

Data availability statement

The generated during and/or analyzed during the current study will be made available upon publication in the Harvard Dataverse.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Appendix

WHO Response Action Examples

Leadership

A WHO leadership action from 21 February 2020 communicated the appointment of six high-level experts for studying COVID-19. The statement included:

The WHO Director-General appointed six special envoys on COVID-19, to provide strategic advice and high-level political advocacy and engagement in different parts of the world:

-

• Professor Dr Maha El Rabbat, former Minister of Health of Egypt

-

• Dr David Nabarro, former special adviser to the United Nations Secretary-General on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Climate Change

-

• Dr John Nkengasong, Director of the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

-

• Dr Mirta Roses, former Director of the WHO Region of the Americas

-

• Dr Shin Young-soo, former Regional Director of the WHO Region of the Western Pacific

-

• Professor Samba Sow, Director-General of the Center for Vaccine Development in Mali.

Advice

The WHO issued an Advice statement on 7 March 2020. The advice was a specific set of guidelines and the announcement read: “WHO issued a consolidated package of existing guidance covering the preparedness, readiness and response actions for four different transmission scenarios: no cases, sporadic cases, clusters of cases and community transmission.”

Information

An Information statement was issued on 29 June 2020 announcing a conference on COVID-19 research. “WHO’s first infodemiology conference began, as part of the organization’s work on new evidence-based measures and practices to prevent, detect and respond to mis- and disinformation.”

Science

The WHO issued a Science statement on 15 May 2020 including a research brief pertaining to children and COVID-19. “WHO released a Scientific Brief on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19.”

Resource

On 30 September 2020, the WHO issued a Resource statement reading, “The UN and partners welcomed nearly US$1 billion in new financing for the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, from governments, private sector, civil society and international organizations.”

Response

The WHO issued a Response statement on 1 October 2020, which related that the, “WHO published a call for expressions of interest for manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines – to apply for approval for prequalification and/or Emergency Use Listing.”

Robustness check models

Several alternative models were run to test the robustness of the paper: (1) lagging the WHO Responses Total variable to ensure that the causal direction was accurately being captured, (2) using COVID-19 case and death per capita variables to test the proportional impact of pandemic impacts, (3) logging the population and GDP variables (4) interacting WHO Responses Total with the Civil Liberties and Political Rights variables and (5) interacting WHO Responses Total with Rule of Law.

1. Lagged WHO Responses Total.

Global Crisis Measures and ICCPR Derogation January 2020–February 2021

Note: Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .10.

Models run on Stata 14.2.

2) Using COVID-19 case and death per capita variables to test the proportional impact of pandemic impacts.

Global Crisis Measures and ICCPR Derogation January 2020–February 2021

Note: Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .10.

Models run on Stata 14.2.

3) Logging the population and GDP variables.

Global Crisis Measures and ICCPR Derogation January 2020–February 2021

Note: Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .10.

Models run on Stata 14.2.

4) Interacting WHO Responses Total with Civil Liberties and Political Rights.

5. Interacting WHO Responses Total with Rule of Law.

Note in the model that Rule of Law is converted to a dichotomous variable to run as an interaction term. Rule of Law here = 1 if .50 or greater and 0 if less than .50 on the continuous measure.

Global Crisis Measures and ICCPR Derogation January 2020–February 2021

Note: Robust Standard Errors in Parentheses *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .10.

Models run on Stata 14.2.

WHO Legitimacy Examination

The following are approximate measures of public confidence in the WHO as drawn from the World Values Survey and visualized in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hu, Yuan, Zwng and Yang2022, figure 2). Derogation counts from this paper.