Introduction

The 1 November 2022 elections and government formation, on 15 December 2022, imply that the beginning of 2023 was not only the beginning of that year but also a new election and government period. However, mostly this has just been business as usual anyway.

Cabinet report

The government of Mette Frederiksen II took office on 15 December 2022, six weeks after the 1 November 2022 elections. The government was still in office by the 31 December 2023. It is an uncommon type of government in a Danish context (Kosiara-Pedersen & Kurrild-Klitgaard Reference Kosiara-Pedersen, Kurrild-Klitgaard and Lisi2019), mostly due to it including parties from both the centre-left bloc and the centre-right bloc, but also due to its minimal winning majority. There are 179 seats in the Danish Parliament, whereby 90 is the key number of seats necessary for a majority. At the time of formation, the three governing parties had 89 seats out of the 175 elected in ‘mainland’ Denmark. The government was furthermore supported by three of the four North Atlantic seats, two of which are elected in Greenland and two on the Faroe Islands. When two of the Moderates’ MPs left the party in 2023 and became independents (see below), the majority behind the government was reduced to 90, which is the absolute minimum for a majority.

Jakob Ellemann-Jensen, Vice-Prime Minister and Defence Minister, took illness leave between 21 February and 1 August, during which Troels Lund Poulsen took on the defence minister role. The vice-chair of the Liberal party, Stephanie Lose, until then chair of the regional council (regional level ‘mayor’) in Southern Denmark, stepped in as Minister for the Economy (Poulsen's former portfolio). When Ellemann-Jensen returned at the beginning of August, Poulsen returned to the Economy and Lose to the regional council. However, on 23 August, Ellemann-Jensen and Poulsen swapped ministries, leaving the Defence to Troels Lund Poulsen and the Economy to Ellemann-Jensen. On 23 October, Jakob Ellemann-Jensen left both his ministerial office and the parliament. In the meantime, Troels Lund Poulsen managed both ministerial duties, but on 23 November, there was a minor change in government composition among Liberal ministers. First, MP Morten Dahlin replaced Louise Schack Elholm as Minister for Rural Areas, Church Minister and Minister for Nordic Cooperation. Second, Stephanie Lose, chair of the regional parliament in the region of Southern Denmark, was recruited from outside the parliament but within the Liberal party (currently the party's vice-chair). Lose is very popular with the hinterland and was, again, appointed as Minister for the Economy. A third new minister was recruited from outside politics: Mia Wagner, a high-profiled business entrepreneur, known by the public from her role in ‘The Lions’ Den’ (a TV show), was appointed Minister for Digitalisation and Minister for Equality, replacing Marie Bjerre. Unfortunately, Wagner went on sickness leave already on 1 December due to a heart issue, and by 7 December, she had stepped down. Marie Bjerre was then reappointed as Minister for Digitalisation and Minister for Equality.

Information about Cabinet composition and changes is reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Frederiksen II in Denmark in 2023

Notes: 1. Stephanie Lose was formally appointed ‘minister without portfolio in order to handle the business of the Ministry of the Economy’ from 9 March to 31 July 2023.

2. The share of seats in Parliament includes the four North Atlantic MPs elected in Greenland and Faroe Islands, totalling 179 seats.

Sources: Folketinget (2024a, 2024c); Koogi (Reference Koogi2023); Statsministeriet (2022).

Parliament report

The trends of a large number of exits, defections, and new parties in Parliament in the 2019–2022 period continued after the 2022 elections (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023a), and to some extent into 2023, with no new parties but party change and an increased number of independents as well as exits from politics.

Due to the prospect of Lars Boje Mathiesen acquiring the chairmanship of the New Right, MP Mikkel Bjørn swapped the New Right with the Danish People's Party on 24 January. Also, Mette Thiese, a former MP for the New Right, joined the Danish People's Party on 6 February 2023. Mette Thiese had left the New Right immediately after the election due to turbulence on the election night but had remained in the parliament as an independent (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023a).

By the end of 2023, there were four independents in the parliament (Folketinget 2024b). Despite having recently become party leader (see Political Party Report), Lars Boje Mathiesen was excluded from the New Right on 10 March 2023, leaving the party group below the threshold for financial group support and substantially reducing its party group income. Mathiesen chose to become an independent. MP Theresa Scavenius, elected in 2022, left The Alternative on 18 September due to disagreements within the parliamentary group and also became an independent.

Two MPs from the Moderates, a newly formed centre-party chaired by former PM and Liberal chair, Lars Løkke Rasmussen (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023b), became independents in 2023. Jon Stephensen, a 63-year-old man, had sent inappropriate messages to a 19-year-old woman party colleague, saying that she was ‘beautiful with the hottest body’. He first went on leave but then decided to leave the party and return to the Parliament as an independent on 18 August. He made an agreement with the government, getting committee posts in exchange for his supporting the government (Alstrup Reference Alstrup2023). Another MP from the Moderates, Mike Villa Fonseca (male, 1995), was expelled from the party on 17 November due to a relationship with a 15-year-old. The party rules state, that participation in sexual activities with children (persons under 18 years) is not permitted (Moderates 2022). The party's code of conduct does not state whether they regulate only life in the party and political world or whether they also cover the private life of elected representatives, candidates and party members. However, they were interpreted by the party leadership to cover also the private world, where a relationship with a 15-year-old is not illegal. Furthermore, it is intriguing to see the difference in how the two cases of misconduct within the Moderates were handled since Stephensen's text message could also be said to violate the Moderates’ rules on sexual harassment but, rather than being expelled, he was initially invited to take a leave of absence.

In addition to these party changes, some MPs stepped down and left their seat to a party colleague. Sofie Carsten Nielsen, former chair of the Social Liberals, who stepped down due to the poor results at the 2022 election, left the parliament on 1 May 2023 and was replaced by Stinus Lindgreen, a scientist, who was very active and vocal when he sat in the parliament during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Democratic Mette Gjerskov, former minister (2011–2013) and MP since 2005, died on 12 June, and her seat was replaced in Parliament on 13 June by Tanja Larsson. One of the younger Social Democrats with the prospects of a bright future in the party, Kasper Sand Kjær (born 1989), MP since 2019, left Parliament on 2 November to do something else after 20 years in politics from the student council at his elementary school to the parliament. He was replaced by Gunvor Wibroe. When Liberal chair Jakob Ellemann-Jensen also left politics (see Political Party Report), he was replaced by Heidi Bank on 24 October.

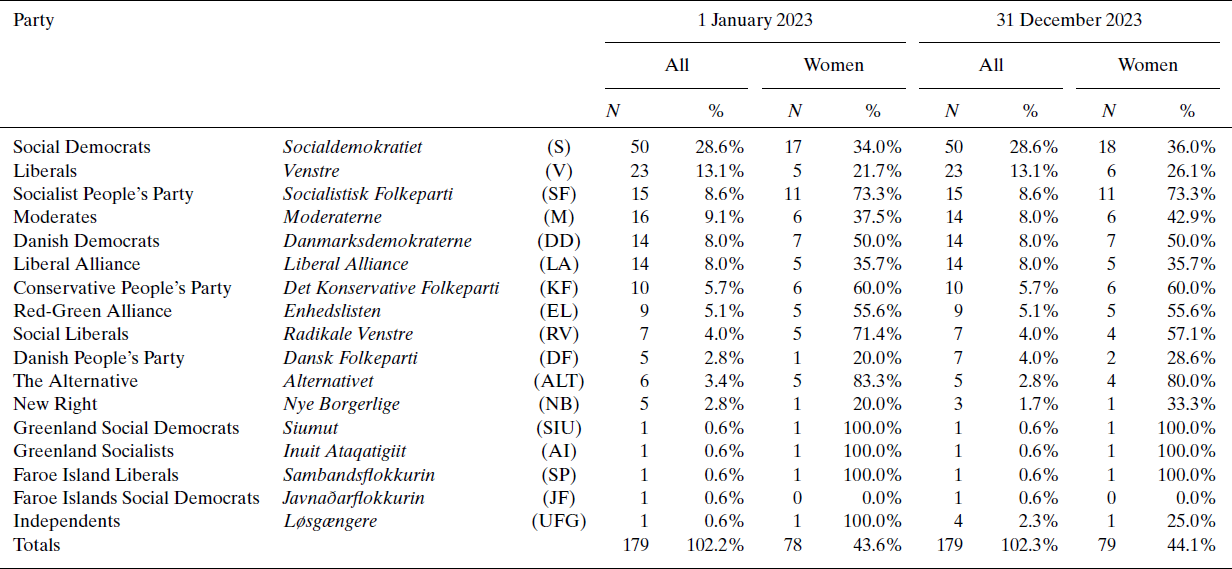

Information about party and gender composition of the Parliament is reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Folketinget) in Denmark in 2023

Political party report

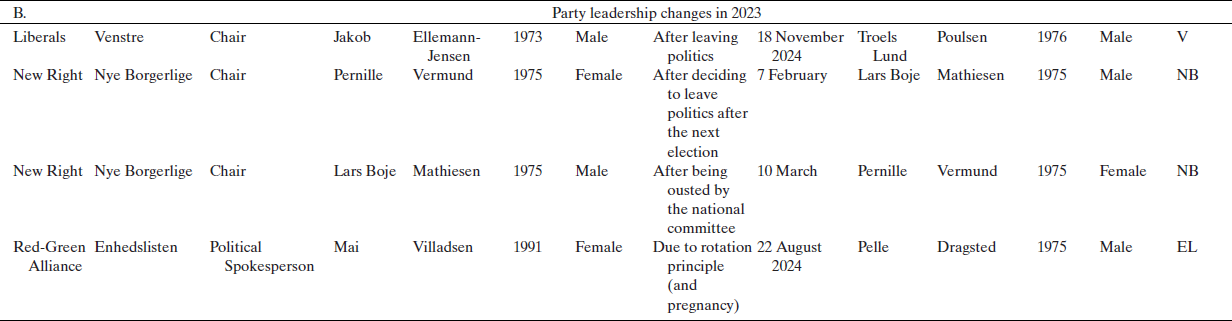

Due to Jakob Ellemann-Jensen leaving politics on 23 October, the Liberals needed to elect a new party chair. Troels Lund Poulsen was the only candidate, and he was elected at the annual meeting on 18 November. Stephanie Lose continued as vice-chair.

In the New Right, Pernille Vermund, who formed the party with Peter Seier Christensen back in 2015 and has had chaired it since then announced she wanted to leave politics after the next election and stepped down as party chair on 10 January. Lars Boje Mathiesen was elected chair on an extraordinary annual meeting on 7 February. However, on 10 March, the national committee ousted him from the chairmanship and expelled him from the party due to disagreements on whether campaign money was his own as well as the payment he expected as chair (Holst & Andersen Reference Holst and Andersen2023). Pernille Vermund reclaimed the party chair position after this.

At the annual summer meeting in August, the Red-Green Alliance parliamentary group appointed a new political spokesperson, which is the closest equivalent role to party leader in this party. Pelle Dragsted replaced Mai Villadsen, who was pregnant but who also needed to be replaced prior to the next election, as she due to the rotation rules within the party could not stand for parliamentary election again. Dragsted is the fourth political spokesperson since Schmidt Nielsen was selected in 2009. He is the first man and a strong ideologue.

More than 150 parties are currently approved by the Ministry of the Interior/Domestic Affairs and, hence, may begin collecting the signatures necessary to be eligible to stand for election (1/175th of the votes cast at the most recent election). Of the 46 party parties approved in 2023, one (Stabilt Demokrati) was created by Jørn Jønke Nielsen, who was formerly part of the biker gang ‘Hells Angels’ and convicted of both violence and murder (Hansen Reference Hansen2023).

Information about changes in political parties is reported in Table 3.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Denmark in 2023

Sources: Enhedslisten (2023); Folketinget (2024c); Ritzau (2023a); Tørnqvist (Reference Tørnqvist2023).

Institutional change report

No changes to the constitution, basic institutional framework, electoral law or other major changes to the rules of the game occurred in 2023.

Issues in national politics

By the end of 2023, the government had been in office for a year. Expectations were high due to its branding as a ‘reform’ and ‘action’ government in line with its status as an ‘across-the-centre’ majority government. But the government did not do more than any other government, and the government parties’ electoral support, based on opinion polls, is now drastically reduced, from half the voters to around a third (Eller & Tofte Reference Eller and Rønn Tofte2023).

The government started off the year by announcing the abolishment of a national holiday, St Bededag, which is the fourth Friday after Easter. This unpopular decision was confirmed in March, after which the government launched a major reform of the university policies, in particular cutting down student stipends as well as in particular halving some of the two-year MA degrees. The cost-of-living crisis is present but not severe within the Danish welfare state. No extraordinary measures were taken in 2023. Major issues, such as climate initiatives, in particular a carbon tax on agriculture and the reform of the health care sector, were postponed beyond the first year of the government.

Due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, defence and security rose on the political agenda in 2022 impacting both the referendum on Denmark's opt-out of EU defence on 1 June 2022 and the broad coalition of parties agreeing on increasing public spending on defence to 2 per cent of Denmark's GDP (Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023a), and in 2023, the discussion was mostly about the implementation of the expansion of the defence budget. The Israel–Palestine war ignited the always smouldering debate on the region, in particular on who was willing to distance themselves from Hamas’ terrorist attack and acknowledge the civil victims on both sides. In October, PM Mette Frederiksen laid flowers for the Jewish victims only, but in December, she laid them for all (Ritzau 2023b).

On 27 October, the Supreme Court decided that the cases against the former chief of the Defence Intelligence Service, FE (Forsvarets Efterretningstjeneste), Lars Findsen and former Defence Minister Claus Hjort-Frederiksen, both charged for divulging secrets of importance to state security (see Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2023a), could not be held behind closed doors. Hence, the cases were dismissed by the state attorney, unwilling to put out classified information. The Justice Minister established a commission on 1 October to investigate the dismissal of FE staff.

On New Year's Eve, Danes gather in front of the television at 18:00, possibly with canapés and a drink, to listen to Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II's New Year speech. Much to the surprise of everybody, Her Majesty announced, that she would step down on 14 January, which is 52 years after she took over the throne from her father. Denmark is a constitutional monarchy, where the formal head of state, the Danish monarch, retains only ceremonial functions. A few parties include Republicans, in particular the left-wing Red-Green Alliance (whose MPs do not enter the parliament until after everybody is seated, so as to avoid rising for the entry of the monarch at the annual opening of the Parliament) and the Social Liberals, but the status of the monarchy is not questioned politically.