Introduction

In many advanced economies, government debt has steadily increased since the 1970s and the issue has become particularly salient and politicised since the Great Recession. Commencing with the Greek sovereign debt crisis, governments across Europe implemented fiscal consolidation. Under the guise of austerity, they slashed government spending and increased taxes to reduce government debt.Footnote 1 In the absence of a viable ‘growth model’ (Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016), this contributed to a sluggish economic recovery across Europe (Blyth, Reference Blyth2013). It dampened demand, undermined state capacities in crucial areas such as healthcare or education and resulted in considerable political turmoil (Copelovitch et al., Reference Copelovitch, Frieden and Walter2016).

While macroeconomic policies were long considered part of the technocratic realm of ‘quiet politics’ (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011), they have moved into the electoral realm of ‘noisy politics’ over the last decade. The cumulative impact of the financial crisis, the eurozone crisis and the pandemic on Europe's economies has been unprecedented. Public debt has substantially increased, and the politicization of public debt and fiscal consolidation will likely accelerate yet again, once short-term emergency measures to combat the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic are over. Consequently, governments will be confronted with tough fiscal policy choices, further exacerbating political conflict over fiscal policies.

In this context, it is vital to understand citizens' fiscal policy preferences. To what extent do they care about debt? A large body of research finds that government debt is unpopular and fiscal consolidation is broadly in line with public opinion. According to this view, citizens are fiscal conservatives, who dislike government debt and support balanced budgets (e.g., Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2019; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019; Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018, Reference Barnes and Hicks2021b; Brender & Drazen, Reference Brender and Drazen2008; Giger & Nelson, Reference Giger and Nelson2011; Peltzman, Reference Peltzman1992). In contrast, other research suggests that citizens punish governments for implementing fiscal consolidation. According to this view, voters oppose spending cuts and tax increases, which reduce the popularity of governments, harm the re-election chances of incumbents and contribute to the success of populist parties (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Fetzer, Reference Fetzer2019; Galofré-Vilà et al., Reference Galofré-Vilè, Meissner, McKee and Stuckler2021; Hübscher & Sattler, Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021; Jacques & Haffert, Reference Jacques and Haffert2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017). The debate about whether voters are fiscal conservatives is thus ongoing. For example, Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021, p. 488) recently argued that ‘austerity … is actually a popular response to economic crises among the voting public’, while Hübscher et al. (Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021, p. 1759) argued that ‘a large share of voters systematically objects to fiscal consolidation’.

We weigh in on this debate by explicitly studying how much people care about government debt in the face of trade-offs. Trade-offs are ubiquitous in fiscal policy. Governments have to raise taxes or issue debt in exchange for government spending.Footnote 2 Citizens, however, seem to have conflicting preferences: They support higher government spending and lower taxes and thus want ‘something for nothing’ (Sears & Citrin, Reference Sears and Citrin1982) or ‘more for less’ (Welch, Reference Welch1985). In the words of the former German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble: ‘The sum of the wishes is greater than the amount of money available. Always. The majority of people want more government services, fewer taxes and no debt. That cannot be achieved at the same time’.Footnote 3

In this article, we shift from studying citizens' policy positions towards studying their policy priorities. We argue that unidimensional survey questions (e.g., should the government reduce the level of debt?) only capture citizens' unconstrained position net of their importance. However, priorities issue from both position and importance and are pivotal in times of tight budget constraints. To measure fiscal priorities we use data from two separate survey experiments conducted in four European countries (Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom). Unlike previous studies, we directly measure the importance that people attach to government debt in two ways. First, we use a split-sample experiment which alludes respondents to the trade-offs associated with reducing government debt: lower spending or higher taxes. Second, we use a conjoint experiment to measure multidimensional budgetary priorities towards different fiscal policies that are subject to a budget constraint.

While other studies have used conjoint experiments to study the most or least popular composition of austerity packages (tax increases and spending cuts), they do not include debt as a separate attribute and thereby implicitly assume that debt levels are fixed (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021). In contrast, we include debt as a separate attribute, which allows us to explicitly study the relative priority that citizens attribute to public debt compared to other fiscal policies. Most importantly, our approach makes budgetary trade-offs binding and avoids ‘free lunches’ while still measuring citizens' preferences over expansion or retrenchment. It allows us to study people's relative priorities across fiscal policies in the face of multidimensional trade-offs. Therefore, we test whether citizens are willing to decrease government spending or raise taxes to achieve fiscal consolidation.

The results are twofold. First, the split-sample experiment shows that average support for fiscal consolidation is high in an unconstrained setting but plummets when respondents are informed about the associated fiscal trade-offs. Revenue-based consolidation is widely unpopular, but expenditure-based consolidation is also contested. Second, our conjoint survey experiment reveals that fiscal consolidation is not a priority for citizens. The average citizen cares little about government debt compared to government spending and taxation. Although general tax increases are unpopular, respondents support a more progressive tax system to pay for additional government spending. Studies based on unidimensional questions thus overstate citizens' support for austerity and how much they care about public debt, while they underestimate the support for progressive taxes. Moreover, fiscal priorities vary across socioeconomic groups and countries.

Overall, the article makes several contributions. Substantively, we study public priorities towards the core elements of government budgets (spending, taxation and borrowing) holistically, which resolves the long-standing puzzle that public opinion towards fiscal policies is inconsistent. We demonstrate that public debt is not a priority. By committing themselves to austerity, governments prioritised an aim – lowering debt – that the public cares very little about. By refraining from increasing top income taxes, they shied away from popular policies. This mismatch helps to make sense of some of the political turmoil that we observed in Europe in the wake of the Great Recession (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Hutter and Kriesi2020): As mainstream parties adopted austerity, voters turned to alternatives on the far left and far right of the political spectrum (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Fetzer, Reference Fetzer2019; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021; Jacques & Haffert, Reference Jacques and Haffert2021; Talving, Reference Talving2017).

Methodologically, we build on an emerging field of research (e.g., Armingeon & Bürgisser, Reference Armingeon and Bürgisser2021; Bremer & Bürgisser, Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2022; Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Cavaille et al., Reference Cavaille, Chen and van der Straeten2020; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Traber2019, Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021) to show that traditional, unidimensional survey questions consistently overstate support for individual fiscal policies. They do not allow inferences about respondents' fiscal policy priorities. Knowing citizens' priorities is crucial, however, because it helps scholars and policymakers to assess what citizens want if they cannot have their cake and eat it too. It also helps to better understand electoral competition and anticipate the likely consequences of different policies (see also Hanretty et al., Reference Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan2020). To study priorities, we need to use survey instruments that more realistically capture the trade-offs that governments face. We use two different survey instruments, suggesting a novel way to conduct and analyse conjoint experiments that makes budgetary constraints binding.

To make these arguments, we first briefly review the literature on fiscal policy preferences and explain the article's motivation. Second, we develop theoretical expectations about how citizens prioritize different fiscal policies when confronted with trade-offs. Then, we explain the research design in detail before discussing the results from both experiments. The final section concludes with a discussion of the broader implications.

Government debt and public opinion: Do citizens have inconsistent preferences?

In the 1970s, the literature on political business cycles argued that politicians are interested in using macroeconomic policies (including deficit-spending) to engineer a boom before elections (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975). It was believed that citizens support expansionary policies that increase debt, including higher government spending and lower taxation, due to self-interest. Nevertheless, empirical research showed that political business cycles hardly exist (Golden & Poterba, Reference Golden and Poterba1980) and that citizens have conservative fiscal attitudes, opposing large fiscal deficits (e.g., Blinder & Holtz-Eakin, Reference Blinder and Holtz-Eakin1984; Peltzman, Reference Peltzman1992). Attitudes towards austerity vary over time (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2021a), but there is a lot of evidence that people are, on average, averse to government debt (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2021b). They favour balanced budgets (Stix, Reference Stix2013) and fiscal rules (Hayo & Neumeier, Reference Hayo and Neumeier2016), partly because elite cues and media framing make austerity popular (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; Bisgaard & Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018).

Further research even claims that voters support governments' efforts to reduce the public deficit and debt (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2019; Arias & Stasavage, Reference Arias and Stasavage2019; Brender & Drazen, Reference Brender and Drazen2008; Giger & Nelson, Reference Giger and Nelson2011; Kalbhenn & Stracca, Reference Kalbhenn and Stracca2020). Most prominently, Alesina and his co-authors argued that ‘there is no evidence of a systematic electoral penalty or fall in popularity for governments that follow restrained fiscal policies’ (Reference Alesina, Perotti and Tavares1998, p. 198). This supplemented the influential ‘expansionary fiscal contraction’ thesis: Not only can fiscal consolidation have an expansionary economic effect, but voters do not punish such consolidation initiatives, either (also see Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2019).

However, the finding that citizens are fiscal conservatives cannot easily be squared with other research. First, there is a large amount of empirical evidence that government spending in general, and the welfare state in particular, enjoy widespread support among the public (Bremer & Bürgisser, Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2022; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors1997). This omnipresent support for the welfare state also explains why full-frontal attacks on major welfare state programs are difficult (e.g., Brooks & Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2007; Pierson, Reference Pierson1996). Second, other research suggests that the same is true for lower taxes. Although modal respondents may prefer more progressive taxes, they generally support a lower level of taxes (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017; Barnes, Reference Barnes2015).

Taken together, these findings are puzzling: While citizens support higher levels of government spending, they do not want to pay for it through tax increases or debt. As a result, academics have identified inconsistent preferences and a lack of congruence in people's thinking about fiscal programs for a long time (Citrin, Reference Citrin1979; Mueller, Reference Mueller1963; Sears & Citrin, Reference Sears and Citrin1982; Welch, Reference Welch1985). As Wolfgang Schäuble recognized, this creates a dilemma for politicians and political parties that have to square the circle when designing government budgets. As Bell (Reference Bell1976, pp. 226–227) already contended: ‘how much the government shall spend, and for whom, obviously is the major political question of the next decades … [but] the pressure to increase services is not necessarily matched by the mechanisms to pay for them, either a rising debt or rising taxes’.

Yet, public opinion research on fiscal policies tends to assess public opinion on individual policies independent of other fiscal policies. It does not capture the multidimensionality of fiscal policies and ignores that governments face difficult trade-offs (Adolph et al., Reference Adolph, Breunig and Koski2020). In challenging economic times, governments cannot rely on growth to shrink the debt burden. Instead, they have to cut spending or increase taxes. Fiscal consolidation thus carries substantial trade-offs, which are not accounted for in unidimensional survey questions. To measure support for fiscal consolidation we need to directly measure whether voters care about government debt, which is something that even recent, sophisticated studies on fiscal policy preferences do not address. They either exclude debt from the analysis altogether (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Blumenau and Lauderdale2022) or only measure support for features of austerity packages that do not include debt as a separate dimension (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021). Since governments cannot make decisions about debt in isolation from other policies, this does not adequately represent public budgeting and likely overstates public support for fiscal consolidation.

To measure whether voters support fiscal consolidation, we need to move beyond assessing people's position towards individual fiscal policies and move towards explicitly studying people's fiscal policy priorities in multidimensional choice settings. Knowing about people's priorities is important for several reasons (see also Hanretty et al., Reference Hanretty, Lauderdale and Vivyan2020). First, relying on unidimensional position questions to assess what the public wants is not helpful for policymakers. The resulting signals are incoherent since citizens support higher spending, lower taxes and lower debt at the same time. In contrast, studying priorities will provide valuable information to policymakers and scholars alike about which policies citizens deem essential. Second, it allows us to better understand political competition and predict the electoral consequences of different fiscal policies. Voters should only react to different fiscal policies if they also care about them. Third, it enables us to study elite responsiveness to public opinion more carefully. Governments may be equally responsive to all citizens' policy positions, but they could still give more weight to the priorities of high- than low-income people (Bartels, Reference Bartels2016).

Taking trade-offs seriously: From policy positions towards priorities

Average fiscal policy priorities

We assume that most fiscal policies are highly visible and salient (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007) and that the average citizen evaluates fiscal policies in light of their costs and benefits and their temporal proximity (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012). On the one hand, citizens do a cost–benefit analysis of fiscal policies because they care about the benefits they receive from spending and the costs associated with taxation and public debt. On the other hand, citizens add an intertemporal component into their cost–benefit analysis and evaluate whether fiscal policies impact current or future costs and benefits.

In principle, support for lower government debt may be high among the public, but it should drop when citizens face the inherent trade-offs that fiscal consolidations imply (Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Hockley & Harbour, Reference Hockley and Harbour1983). Debt is an abstract concept, and its impact on citizens is less direct than taxes (which they pay regularly) or government spending on public benefits or services (which many receive/use continuously). Compared to other dimensions of fiscal policy, government debt carries little cost for citizens. Only when countries face a sovereign debt crisis, the costs of debt increase and citizens directly feel adverse economic consequences. In all other circumstances, government debt has little influence on the average citizen's income, and they should not strongly care about it.

According to the Ricardian equivalence theorem, public debt can be seen as a form of future taxation. However, we know from the literature on intertemporal trade-offs that citizens are myopic and have high discount rates (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011). When people evaluate government policies, they give less weight to long-term consequences than those that emerge in the short term. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that budgetary decisions that affect current costs and benefits have a larger impact on citizens' priorities than budgetary decisions affecting future costs and benefits. They should not care very much about public debt, especially when governments face low borrowing costs due to low interest rates (Blanchard, Reference Blanchard2019).

Instead, citizens should care more about government spending and taxation. Following Pierson (Reference Pierson1996), we assume that existing forms of government spending create strong electoral constituencies reluctant to accept retrenchment. For example, pensions are the most popular form of social spending in advanced welfare states because many people are retired or expect to retire. Similarly, citizens should be reluctant to increase taxation, which reduces the disposable income of almost all citizens, especially consumption taxes (VAT) and income taxes. The costs and benefits that government spending and taxation have for the average citizen are higher and influence the current income.

We, therefore, expect that government debt is not a priority for the average citizen. Most people care more about protecting their benefits (from government spending) or reducing their costs (from taxation) than lowering government debt. By this, we do not mean to say that people do not care at all about public debt. They indeed seem to support fiscal consolidation when asked about it in isolation. Given the abstract nature of public debt and the uncertainty of how public debt impacts citizens' future costs, however, we assume that citizens prioritise lower taxation and higher government spending over lower public debt. On average, support for fiscal consolidation should decline substantially when the necessary spending and tax trade-offs are explicitly acknowledged.

Furthermore, we assume that citizens react differently to expenditure- than revenue-based consolidation because taxes affect most citizens' disposable income more directly than government spending. A large share of public spending does not directly flow into people's pockets: Infrastructure, education or even healthcare spending influences the median voter's disposable income indirectly and often only in the future. In contrast, tax increases affect the median voter's budget much more directly: They immediately experience a drop in their disposable income. People should care more about the costs from taxation than the benefits of government spending and, therefore, be more opposed to revenue-based consolidation than expenditure-based consolidation.

Yet, revenue- and expenditure-based consolidation can be pursued in different ways. On the expenditure side, we can distinguish between immediate, short-term consumption spending (e.g., public pensions) and investment spending (e.g., education). Unlike consumption spending, the benefits of most investment spending accrue in the future. While almost all citizens benefit from education and pensions at a certain point in their lives, some citizens do not use the full educational offer and leave after mandatory school. On the revenue side, we can distinguish between general income taxes and consumption taxes. Generally, these taxes are a cost and reduce the disposable income, but the specific tax design determines how much the average citizen is affected by them. The average citizen should be reluctant to pay proportionally higher income and consumption taxes in general but be more inclined to prioritize progressive taxation (e.g., top income taxes).

Overall, this implies the following fiscal policy priorities for the average citizen: Taxation should be the highest priority, followed by government spending and then by government debt. Although citizens prefer reducing debt, this has a lower priority than reducing taxes and increasing government spending. More specifically, we expect that citizens attach a high priority to pension spending and top income taxes; a medium priority to general income taxes, consumption taxes and education; and a low priority to government debt.

Heterogeneous fiscal policy priorities

We expect that different socioeconomic groups may have heterogeneous fiscal priorities. Until today, we know very little about what drives priorities, as opposed to positions, but below we will test this in an exploratory fashion. Specifically, we expect people's priorities to differ according to three dimensions: material self-interest, ideology and institutional context.

First, material self-interest likely influences attitudes towards fiscal consolidation (e.g., Meltzer & Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). Income is the best measure of self-interest, as income groups have different cost–benefit calculations. For example, low-income citizens are more likely to benefit from public transfers than high-income citizens, and they should thus be more opposed to expenditure-based consolidation than revenue-based consolidation. In contrast, citizens who do not receive public transfers should react more strongly to tax increases because their disposable income is more directly affected by tax increases than spending cuts.

Moreover, ideology also shapes attitudes towards fiscal policies (e.g., Jacoby, Reference Jacoby1994; Margalit, Reference Margalit2013). Beliefs provide people with information about how the economy works and allow them to assess policies based on principles such as fairness (Limberg, Reference Limberg2019). In general, it is often thought that the left cares less about rising public debt, favouring deficits (Cusack, Reference Cusack1999). Left-wing citizens support government services and benefits and should be more likely to oppose expenditure-based consolidation than voters from the right. Right-wing citizens are more likely to support small governments and free markets, favouring lower taxes. They should be more opposed to revenue-based consolidation than left-wing citizens.

Finally, we know that existing institutions and policies have feedback effects (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012; Gingrich & Ansell, Reference Gingrich and Ansell2012; Pierson, Reference Pierson1996), likely causing people's priorities to vary by institutional context. Therefore, the legacy of previous policies affects the current economic environment and the perceived need for different economic policies. Most importantly, the existing level of public debt could affect fiscal priorities. Even though interest rates on government bonds have recently been relatively low, some countries do face higher borrowing costs: Governments with higher debt usually have to pay higher interest rates and are more likely to face sovereign debt crises. The costs of these crises are substantial, and we thus expect average support for fiscal consolidation to be higher in countries that recently experienced such crises. In these contexts, people are more aware of the costs of debt than elsewhere.

Research design

We use two separate survey experiments to overcome problems associated with conventional surveys while making modest cognitive demands upon respondents. First, we use a split-sample experiment to gauge individuals' priorities for spending- and revenue-based fiscal consolidation. Second, we use a conjoint survey experiment to elicit multidimensional budgetary priorities.Footnote 4 In contrast to related research on austerity (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021), our research design includes debt as a separate dimension in the conjoint survey experiment, which can increase or decrease. We can thus explicitly test whether respondents care about government debt instead of implicitly assuming that they do.

In both experiments, we refrain from using specific levels to keep them cognitively simple and allow comparisons across countries. Our pretest with an opt-in sample from Prolific showed that respondents were cognitively overwhelmed by more complex survey experiments with specific levels and that they preferred a simpler design with more straightforward levels.Footnote 5 We assume that people do not need to know a lot about government budgets to evaluate different alternatives (Hansen, Reference Hansen1998; Sanders, Reference Sanders1988). Governments decide on budgets annually, and budgetary debates are a regular feature of the political discourse familiar to many citizens. Hence, citizens only need to know the rough contours of a policy to decide whether they like it or not.Footnote 6

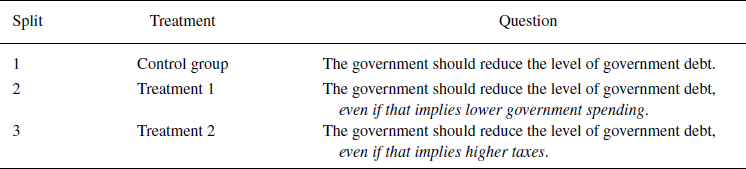

Part 1: Experiment with split-sample questions

The first survey experiment explicitly tests how individuals change their priorities on fiscal consolidation when confronted with two-dimensional trade-offs. We randomly assigned respondents to three different groups, including one control group and two treatment groups.Footnote 7 In each group, respondents evaluated a statement about government debt (see Table 1). We confronted respondents in the treatment groups with different statements that raised awareness of budgetary trade-offs: spending-based fiscal consolidation and revenue-based fiscal consolidation. The control group was presented with a statement that did not mention any trade-offs. Subsequently, respondents evaluated to what extent they agree or disagree with these different statements.

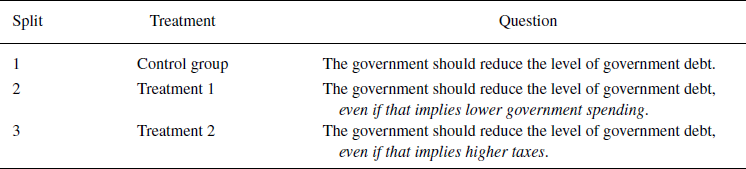

Table 1. Design of the split-sample experiment

To analyse whether support for fiscal consolidation varies across the three groups, we graphically present the predicted mean support for fiscal consolidation for the control and the two treatment groups based on ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. As a robustness test, we also control for several covariates (e.g., age, sex, marital status, education, income, employment status, union membership and partisanship), and we add country-fixed effects (see Online Appendix A for the detailed operationalization of all variables). Moreover, we analyse heterogeneous effects by income, partisanship and country.

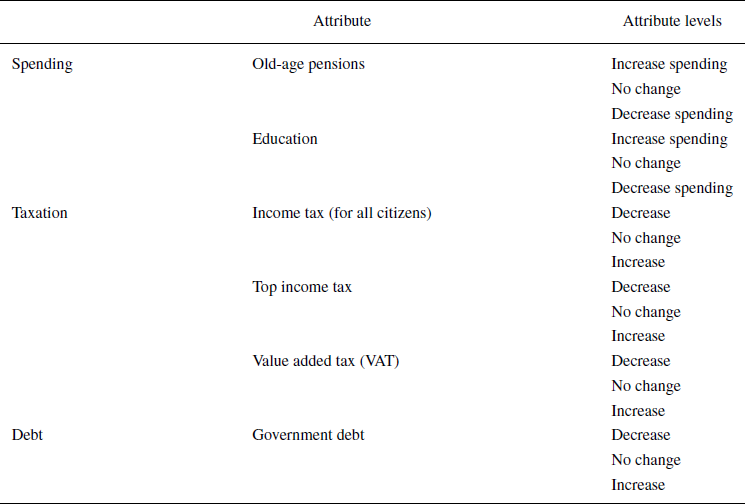

Part 2: Conjoint survey experiment

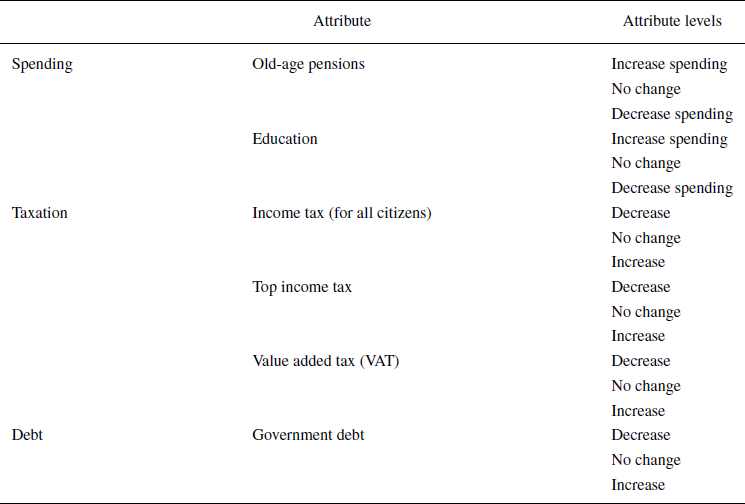

Before confronting respondents with the split-sample experiment introduced above, the survey included a conjoint survey experiment to study public priorities towards fiscal policies in a multidimensional setting. Conjoint survey experiments are useful for this purpose because respondents have to evaluate policy packages rather than individual policies (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Specifically, we asked respondents to evaluate changes to the government budget in a set of choice tasks. They were asked five times to choose (i) between two fiscal packages (choice variable) and (ii) how likely they are to support each of the packages (rating variable). The profiles comprised six attributes corresponding to particular elements of a government budget (see Table 2), and each attribute could take on a set of discrete and predefined levels. Before asking respondents to evaluate the policy packages, we told them to consider the situation of their country, that is, to use their country's debt, spending and tax levels as a reference point.Footnote 8

Table 2. Attributes and levels of the conjoint experiment

The fiscal packages' attributes represent the three dimensions of government budgets: spending, taxation and debt. To reduce complexity and avoid cognitive exhaustion, we limited the number of attributes and levels and selected major spending and taxation items that directly influence citizens' disposable income. The profiles include two highly popular spending items, allowing us to distinguish social investment (education) and social consumption (pension). The profiles further distinguish between three different taxes: income tax, top income tax and value-added tax. These attributes include direct and indirect taxes, they relate to the level of taxes (income tax, VAT) and the progressivity (top income tax), and they are among the politically most visible and salient forms of taxation. Finally, the profiles include debt as a separate dimension that allows governments to raise revenues. There are three levels (increase, decrease, no change) for each attribute, allowing us to test priorities towards different combinations of government spending, taxation and debt.

In a fully randomized setting, there would be a total of 729 combinations. However, to represent the budgetary process accurately and to account for trade-offs, we introduced restrictions to avoid illogical combinations. In reality, taxes and government debt pay for government spending. To ensure external validity, we made budgetary constraints binding and only allowed combinations in which every increase in expenditure or decrease in revenues is matched by a simultaneous decrease in expenditure or increase in revenues. Five hundred eighty-eight combinations were thus excluded, leaving us with 141 possible combinations. However, the likelihood that a certain level appears together with another level is still the same because logical inconsistencies were uniformly deleted. This is due to the fact that each attribute has three symmetrical levels (increase, decrease, no change).

We calculate two main variables of interest from the conjoint experiment. First, we estimate the causal effect of individual attribute levels on the support for the entire fiscal package, compared to the baseline attribute level (status quo) (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). The desirable property of the average marginal component effect (AMCE) is that it incorporates both the position and the importance that individuals assign to each attribute level (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2020) and captures what we conceptually understand as policy priorities. Second, to analyse subgroup differences by income, partisanship and country, we calculate the conditional marginal means for all attribute levels, which measure how favourable respondents are to a given feature of our fiscal packages (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020).Footnote 9

To estimate the AMCEs and marginal means, we use ridge regression. Standard conjoint experiments have dimensions that are independent and fully randomised. Budgetary trade-offs are not independent by design: Changing expenditures or revenues on one attribute requires a change in another attribute. Our experimental design was informed by this target distribution of profiles about which we wanted to make inferences, namely realistic budgetary combinations. Each attribute value depends on the other attributes' values to ensure that the budget is fully balanced. To account for these dependencies, we suggest a novel approach using ridge regression (Hoerl & Kennard, Reference Hoerl and Kennard1970). Ridge regression is a standard regularization method that can be used to address design-based super-collinearity. Horiuchi et al. (Reference Horiuchi, Smith and Yamamoto2018) also used ridge regression for conjoint analysis. To estimate ridge regression, we use the R package glmnet, and we use bootstrapping to calculate non-parametric confidence intervals, which allows us to make inferences about the effect of a changing attribute value, averaging over the distribution of our 141 profiles. The method and rationale are further explained in online Appendix E.

We used a series of tests to check the robustness of our conjoint results. We replicated our conjoint analyses using the rating variable instead of the choice variable (see online Appendix F) and we conducted several standard robustness tests discussed in online Appendix H (carryover effects, profile order effects, screen size, speeding, choice task round). They were designed to check that the standard assumptions of conjoint analysis are satisfied and to probe potential concerns about the validity of the results. The tests indicate that the results shown below are robust.

Sample

Both experiments were included in a survey that we fielded in 2018 in Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. We selected the countries to test whether the overall priorities are similar across different contexts. They represent four major European economies characterised by different variants of capitalism (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001) and growth models (Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016). Given the salience of macroeconomic policies and fiscal adjustment during the European sovereign debt crisis, we included two Southern European countries (Italy and Spain) in the survey along with Germany (a coordinated market economy) and the United Kingdom (a liberal market economy), which both had witnessed fiscal consolidation in post-crisis Europe.Footnote 10

We recruited 1,200 eligible voters in each country from a large online panel provided by Qualtrics. By relying on quota sampling based on age and gender, our sample is representative of all eligible voters on both dimensions. The sample also closely corresponds to the general population in terms of income and partisanship (see online Appendix B for the sampling strategy), except that centre-right voters are slightly underrepresented in Germany and the United Kingdom. We further matched the population's demographic margins in each country as closely as possible using entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012). The results are presented in online Appendix G and yield the same findings. Finally, to ensure our sample's overall quality, we included an attention check and speeding checks. This automatically screened out respondents who paid no attention or sped through the survey.

Results

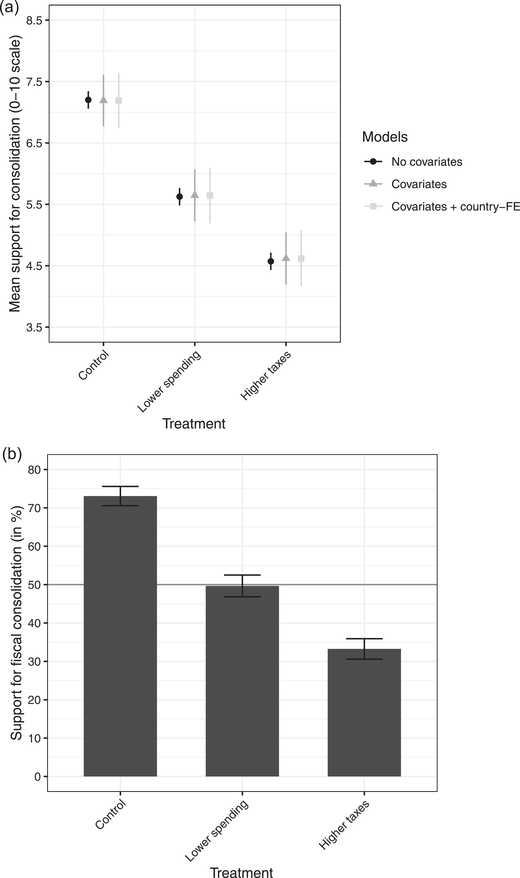

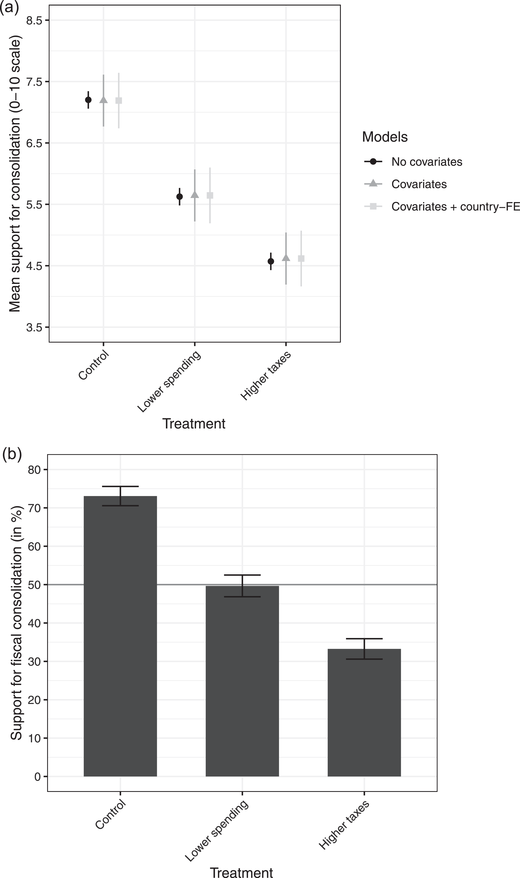

Average support for different types of fiscal consolidation

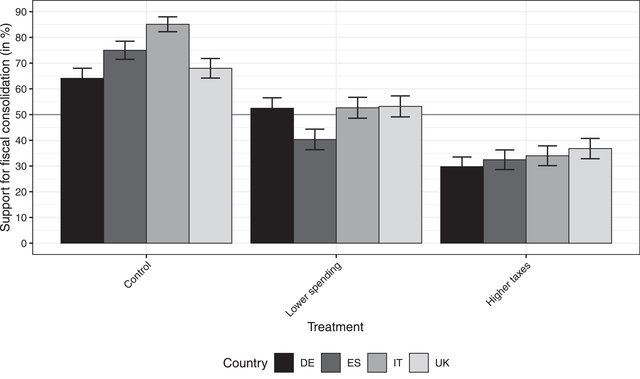

To estimate the impact of the treatments and highlight the importance of budgetary trade-offs, the left panel of Figure 1 shows the mean support and 95 per cent confidence intervals for fiscal consolidation in an unconstrained setting (control group) and the two different trade-off treatments. Our survey confirms the conventional finding that a vast majority of Europe's citizens are fiscal conservatives and, in principle, agree that the government should reduce public debt. In line with our expectation, however, citizens' support for fiscal consolidation is dramatically reduced when confronted with the necessary real-world trade-offs. While the average support for lower government debt in an unconstrained setting is 7.2, this drops to 5.6 when it implies lower government spending. Fiscal consolidation that leads to higher taxes is even less popular, with average support for fiscal consolidation declining to 4.6. These effects are robust to the inclusion of covariates and country-fixed effects.

Figure 1. Predicted average support for fiscal consolidation by treatment, pooled.

Note: Predicted mean support (0–10 scale) and 95% confidence intervals based on OLS regressions with covariates (age, gender, marital status, having children, education, income, labour market status, union membership and partisanship) on the left; share of respondents who support fiscal consolidation on the right.

We dichotomised the dependent variable to estimate the share of people who support lower government debt across the three experimental groups. Since we are interested in support for fiscal consolidation, we use five as the cut-off point, that is, responses from six to ten are counted as agreement, while responses from zero to five are counted as disagreement/neutral. The right panel of Figure 1 shows that a clear majority of 73 per cent of respondents support consolidation in the control group. Support for revenue-based consolidation is a minority position (33 per cent support), while support for expenditure-based fiscal policy is contested (50 per cent support).

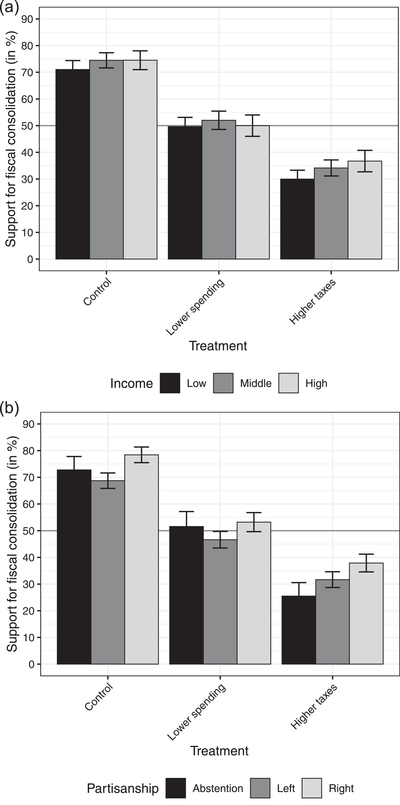

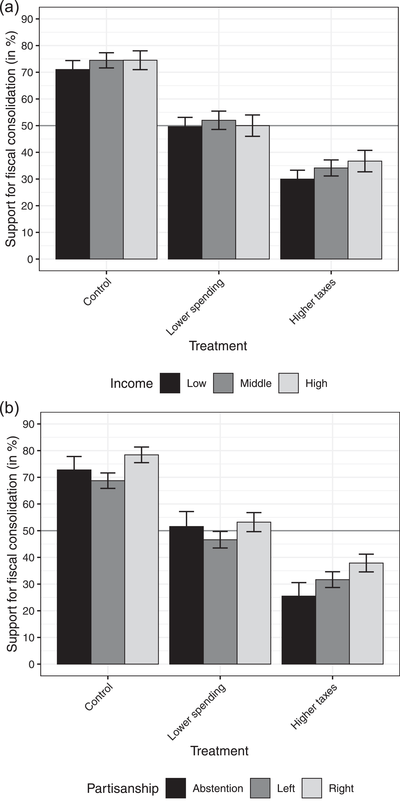

Heterogeneous support for different types of fiscal consolidation

Figure 2 shows the support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off for different income groups and electoral constituencies. In the control group, low-income citizens are slightly less likely to support fiscal consolidation than high-income citizens. The introduction of trade-offs substantially reduces support for fiscal consolidation across all income groups. While differences across income groups turn insignificant for expenditure-based consolidation, support for revenue-based fiscal consolidation remains the highest among high-income respondents. A potential explanation for these small differences is that our very generic descriptions of revenue- or expenditure-based consolidations make it challenging to evaluate the distributive consequences.

Figure 2. Support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and income/partisanship.

Note: Share of respondents who support fiscal consolidation and 95 confidence intervals by trade-off and income (left)/partisanship (right).

In contrast to income, there are more substantial differences between left- and right-wing respondents. There is a substantially and significantly lower share of fiscal conservatives among left-wing than right-wing citizens (68 compared to 78 per cent) in the unconstrained setting. In addition, left-wing voters also more strongly dislike both revenue- and expenditure-based fiscal consolidation than right-wing voters.

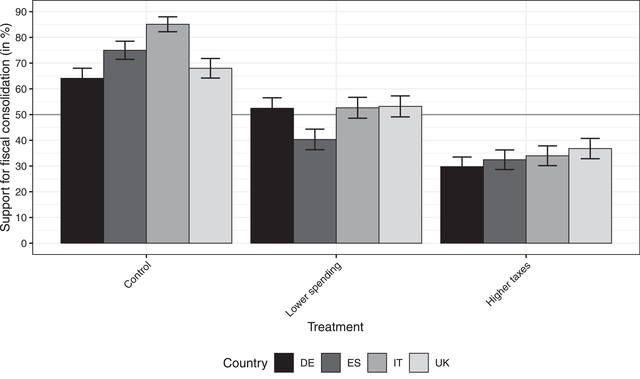

Figure 3 shows that respondents in Italy, where public debt is the highest, are the most fiscally conservative. In Germany, where public debt is the lowest, citizens are the least fiscally conservative.Footnote 11 Contrary to conventional wisdom, citizens in Northwestern Europe are not more debt-averse than in Southern Europe (also see Howarth & Rommerskirchen, Reference Howarth and Rommerskirchen2017). As the average support declines more in Spain and Italy, stark cross-national differences largely disappear in the treatment groups. There are two exceptions: Support for expenditure-based consolidation is significantly lower in Spain than in the other countries, while support for revenue-based consolidation is slightly but still significantly more popular in the United Kingdom compared to Germany. The former could be related to the severity of the eurozone crisis in Spain that resulted in a general increase in support for direct public transfers, making expenditure-based consolidation a clear minority position. The latter could be due to the generally lower tax levels in the United Kingdom, where citizens give the government more leeway to increase taxation than elsewhere.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and country.

Note: Share of respondents who support fiscal consolidation and 95 confidence intervals by trade-off and country.

In sum, support for fiscal consolidation is much lower when respondents are confronted with the inherent fiscal policy trade-offs. This is in stark contrast to Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021), who find a clear majority in favour of fiscal consolidation based on their survey. Even though unconstrained support for fiscal consolidation is relatively high in principle, reducing government debt is not a priority if it implies cutting spending or increasing taxes. While both forms of fiscal consolidation are contested, citizens are more opposed to revenue-based consolidation than expenditure-based consolidation. We find only a few differences across income groups, but partisanship and country differences are larger. Expenditure-based consolidation is particularly contested among left-leaning respondents and in crisis-ridden countries like Spain.

In reality, however, governments rarely pursue either expenditure-based or revenue-based consolidation exclusively. Moreover, it also matters which spending items are cut and which taxes are increased to reduce debt. Governments usually use different policy levers at the same time to achieve their preferred outcome. To tease out the priorities of citizens in a multidimensional setting, we use a conjoint experiment.

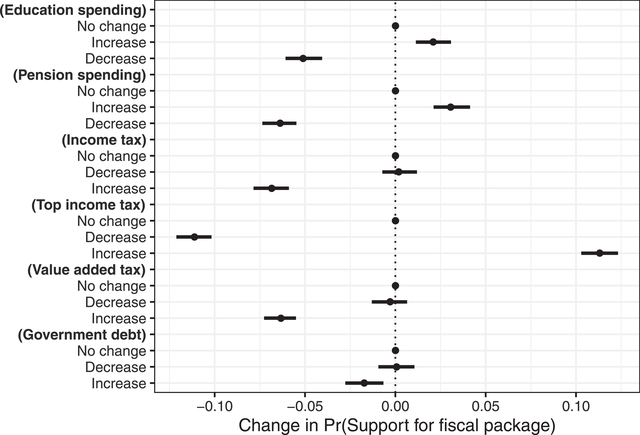

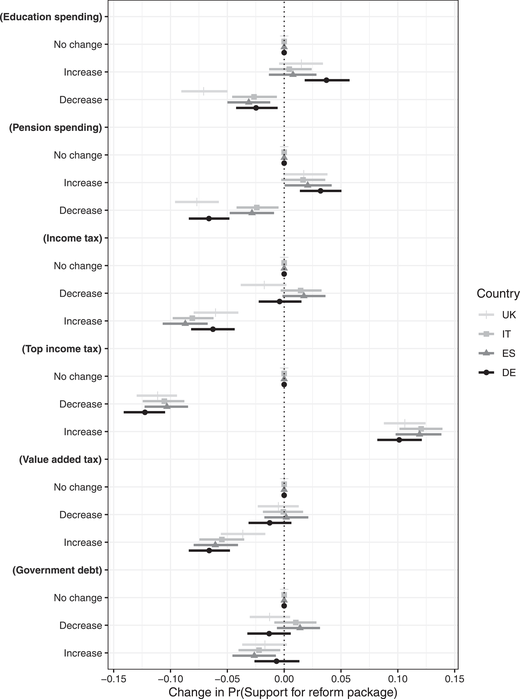

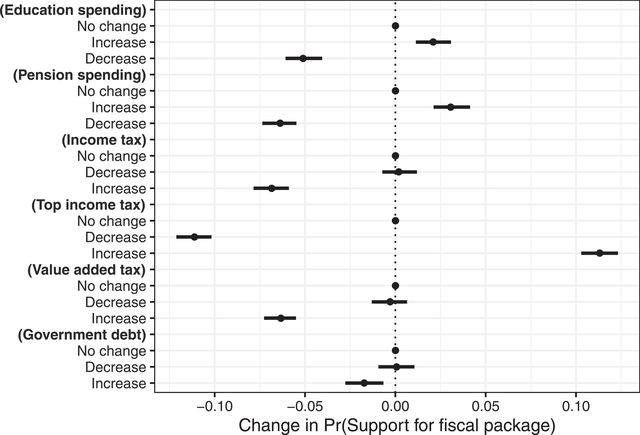

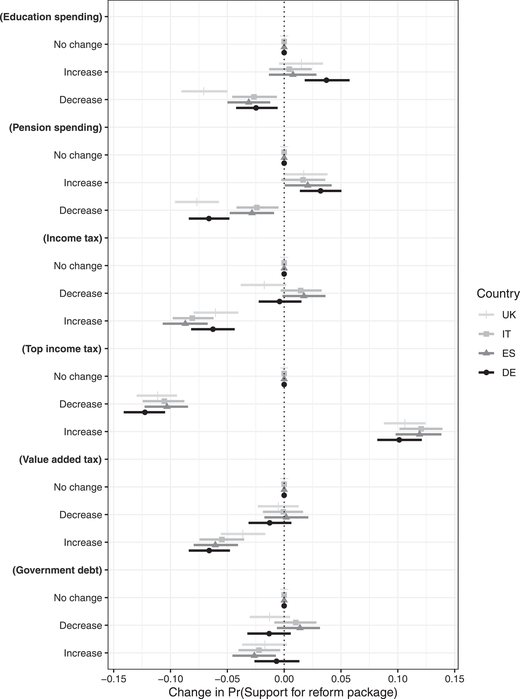

Average fiscal policy priorities

Figure 4 shows the AMCEs of increasing or decreasing spending, taxes or debt relative to the baseline (no change) for each attribute on the probability that a given fiscal package is supported. Given that respondents have to make tough choices when completing the exercise, the figure essentially shows the average citizen's priorities. In line with our previous findings, government debt does not substantially impact the overall support for a fiscal package. Decreasing government debt has no effect, suggesting that respondents are not as fiscally conservative as the existing literature assumes. Increasing government debt reduces the likelihood that individuals support a given fiscal package, but this effect is small (1.7 percentage points relative to the baseline). The marginal means confirm that government debt is not a priority for respondents (see online Appendix F.1): On average, the respondents' probability of choosing a fiscal package is 0.50 with a debt decrease, 0.49 with a debt increase and 0.51 with no change in debt.

Figure 4. AMCEs from conjoint survey experiment, pooled.

Note: Average marginal component effects (AMCEs) of a change in the value of one of our six dimensions on the probability that the respondent chooses the fiscal package.

Second, the results indicate that the average citizen is reluctant to increase general taxes or decrease government spending. Respondents strongly dislike an increase in general income tax and VAT. The former reduces support by 6.8 percentage points, while the latter lowers it by 6.4 percentage points. Similarly, lower pension and education spending also sharply reduce support for a given fiscal package. The effects of such spending cuts are smaller than the effects of general tax increases. In line with the split-sample experiment, citizens are more opposed to revenue-based than expenditure-based consolidation. Generally, respondents are firmly against both forms of fiscal consolidation in a multidimensional setting.

Third, the conjoint survey experiment also reveals the average citizen's priorities about the other side of the coin: spending increases and tax decreases. Increasing pension and education spending have a small, positive effect on support for a given fiscal package. Higher pension spending increases support by 3.1 percentage points, while higher education spending increases support by 2.1 percentage points. Surprisingly, decreasing income tax or VAT does not affect support at all, indicating that lower taxes are not as popular as commonly assumed. Most respondents consider the current level of taxes appropriate (see Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017, for a similar finding for the United States) but strongly support progressive taxes: Raising the top income tax increases support by 11.3 percentage points; reducing it lowers support by 11.1 percentage points (compared to the status quo). Thus, while revenue-based consolidation is generally very unpopular (see split-sample experiment), higher top income taxes are a clear priority. It is a more popular way to raise revenues than either increasing taxes on everyone or increasing government debt.

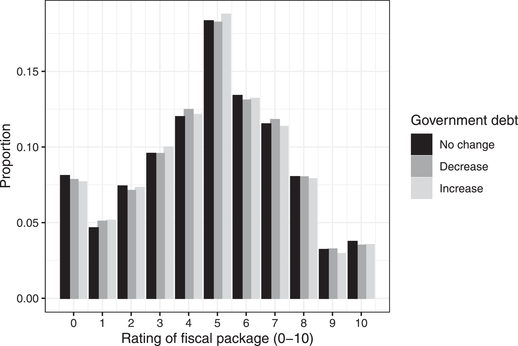

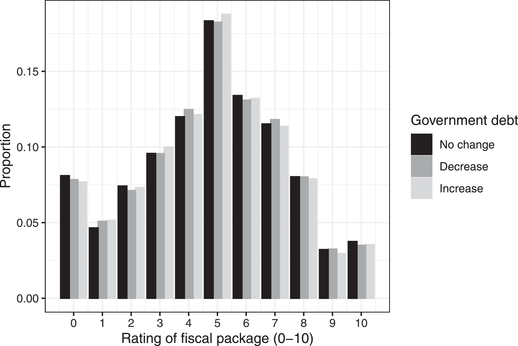

To verify that public debt is not a priority, we exclusively assess the importance respondents assign to this attribute. In addition to the choice-task, we asked respondents to rate each fiscal package on an 11-point Likert scale from zero to ten. This allows us to plot the distribution of the ratings of all conjoint packages by the attribute levels for government debt in Figure 5. The results clearly show that citizens do not attach a high priority to government debt. There are barely any differences visible in how respondents rated the fiscal packages depending on whether public debt stays the same, increases or decreases.Footnote 13 The distribution clearly shows that debt is not a contested issue where many respondents strongly dislike and many strongly support debt. Even at the extreme ends of the distribution, there are hardly any differences in support between the different attribute levels for government debt.

Figure 5. Distribution of the ratings of all fiscal packages by government debt attribute level.

Note: The dependent variable asked respondents to rate each fiscal packages on a scale from 0 to 10.

In sum, the results suggest that government debt is essentially irrelevant for the evaluation of fiscal packages. Decreasing government debt is not a priority for the average citizen, who cares more about protecting the benefits from government spending without having to pay higher taxes (levied on everyone). Instead, it is a high priority for the average respondent to increase top income tax rates to finance additional spending. This latter finding should not be interpreted as evidence for the popularity of revenue-based consolidation more generally, however. Revenue-based consolidation would imply that such tax increases are used to reduce debt and not, as our findings show, to finance additional spending.

Heterogeneous fiscal policy priorities

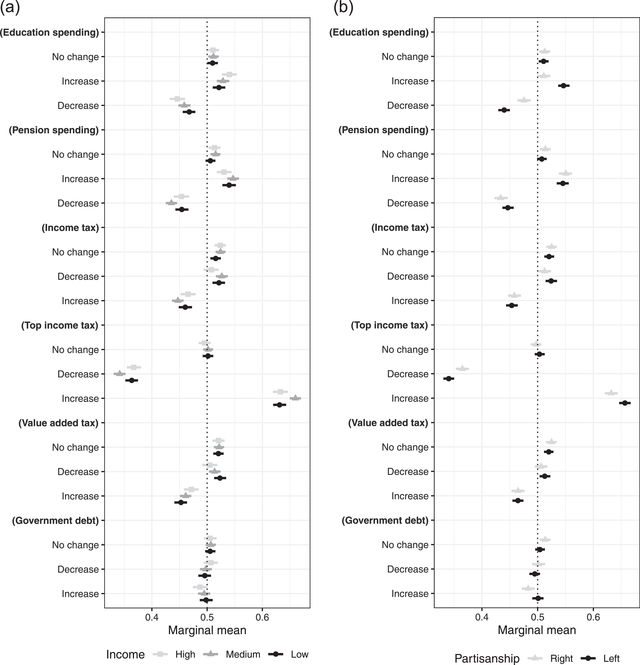

In the last step, we use marginal means plots to elicit subgroup differences. The most striking aspect is that the differences across subgroups are relatively small. The direction of the effects does not change at all, and its magnitude remains remarkably similar. There seems to be a broad consensus about fiscal priorities.

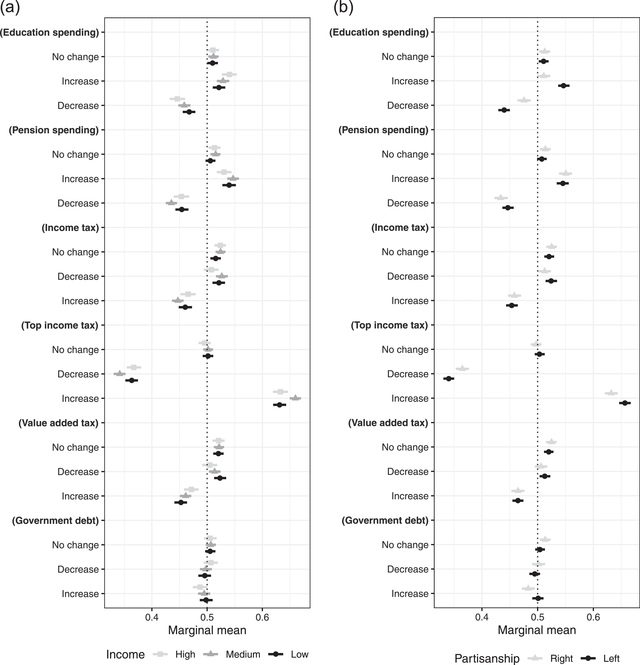

As shown in Figure 6, government debt is not a priority for any income group, but there are a few significant differences concerning spending cuts and tax increases. Education spending is more important for high-income citizens, while pension spending is more important for medium-income respondents. Medium-income citizens are also slightly more supportive of increasing general income taxes and top income taxes than respondents from the other groups. Although this is evidence that the strength of fiscal policy priorities varies by material interest, these differences are relatively small.Footnote 14

Figure 6. Estimated marginal means from conjoint survey experiment by income group and partisanship.

Note: The marginal means measure how favourable respondents are to a given feature of the reform package.

Concerning partisanship, we find that right-wing citizens are slightly more debt-averse than left-wing citizens, that is, they are less likely to support a debt increase and more supportive of the status quo than left-wing respondents. Differences across electoral constituencies are more pronounced for the other two dimensions. First, left-wing respondents are more likely to prioritize education, and this popularity of education spending for the left could explain why left-wing voters react more strongly to spending-based consolidation in the split-sample experiment. Second, left-wing respondents more strongly favour an increase in top income taxes, but it is striking that right-wing respondents also respond positively. If trade-offs are binding, a broad political coalition of citizens prefers raising top income taxes rather than cutting spending or increasing other taxes or debt. Support for pension spending and other forms of taxation are roughly similar for both groups.Footnote 15

Figure 7 shows that the general pattern found above holds across the four countries, with some exceptions where we can detect statistically significant differences. German and British respondents attach a slightly higher priority to education and pension spending than their Italian and Spanish counterparts, whereas Italian and Spanish respondents react more sensitively to government debt. This confirms findings from the split-survey experiment that fiscal consolidation is supported more in countries with higher government debt, indicating that there are likely policy feedback effects at play: In countries with a higher level of public debt (Italy and Spain), citizens presumably perceive it to be a larger risk. They recently experienced the negative costs of a sovereign debt crisis, and, therefore, the costs of debt are more apparent.

Figure 7. Estimated marginal means from the conjoint survey experiment by country.

In stark contrast to most of the unidimensional preference literature, one of the main findings of both our experiments is that subgroup differences become smaller when we introduce salient trade-offs. By studying their priorities as opposed to their unconstrained position, we show that citizens care surprisingly little about government debt.

Conclusion

We presented evidence that the inconsistent fiscal policy preferences that many scholars have identified among the public vanish when we account for the multidimensionality of fiscal policies (Hansen, Reference Hansen1998). Using a split-sample experiment, we showed that support for lowering government debt drops when individuals face the inherent trade-offs. In general, citizens oppose revenue-based consolidation more than expenditure-based consolidation. Left-wing voters react more strongly to expenditure-based consolidation than right-wing voters, but the reverse is not the case for revenue-based consolidation.

The findings from the conjoint survey experiment support our argument that voters do not care as much about debt as they care about government spending and taxation. The public has clear priorities, which are relatively stable across different subgroups. In a multidimensional setting with binding budget constraints, citizens are opposed to spending cuts and general tax increases. They support higher top income taxes to pay for additional spending but do not favour a reduction of debt. On average, voters on the right are more likely to oppose higher debt, which is also the case for people in countries with a recent sovereign debt crisis (Italy and Spain). Overall, however, priorities only vary a little across socioeconomic groups.

The article thus makes important contributions. First, we contribute to the ongoing debate about whether people are fiscal conservatives. Our results show that, in principle, most people agree that high public debt is undesirable and support reducing it (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021). Yet, debt is not a high priority for voters who care more about government spending and taxes. Regular opinion polls that only include unidimensional questions may consistently overstate the support for fiscal consolidation if respondents are not confronted with the real-world trade-offs that such policies entail. Therefore, political scientists should increasingly pay attention to the study of citizens' priorities instead of policy positions.

Second, our findings also help make sense of the political turmoil in Europe in the last decade. As austerity became the predominant response to the economic crisis, political actors prioritised a policy – lowering government debt – that the public cares very little about. Given that government debt is not a priority for voters and that it usually entails trade-offs, reducing it is politically risky (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bremer and Neimanns2021; Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wager2021). It can have high political costs for governments that implement them. This helps to explain the rise of anti-austerity parties, movements and politicians like Syriza, the Indignados or Jeremy Corbyn. As government debt has soared again in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and calls for austerity are growing louder, governments may do well to remember these costs.

Our article, however, also raises several questions for future research. First, our survey instruments were non-political. They did not mention parties, nor did they include rhetorical justifications for different policies. Yet, existing research shows that voters respond to media frames (Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018) and elite cues (Bisgaard & Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018), which can make austerity popular. Parties and politicians can sell policies to voters that they do not prioritize, and they repeatedly did so in response to the Great Recession. This begs the question of whether and how opponents of austerity can use rhetorical devices to make the inherent budgetary trade-offs salient in the eyes of voters.

Second, fiscal policies may not always be salient in the first place. In times of economic crises when macroeconomic policies are politicised, politicians are likely punished for fiscal consolidations, but public opinion may not translate into electoral behaviour when they are not. This raises the question of what determines the salience of fiscal policies and whether politicians can strategically time consolidation initiatives to avoid political backlash (Hübscher & Sattler, Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017). The lack of salience may also explain why governments are able to keep top income taxes low, even though our results show that people support more progressive tax systems when fiscal constraints are binding.

Finally, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, debates about government debt increasingly focus on debt sustainability. Although debt rose dramatically, interest rates on government bonds of most advanced economies remained extremely low. Economists emphasize that this makes high government debt more sustainable (Blanchard, Reference Blanchard2019), but it is unclear whether voters follow arguments about debt sustainability. Future research should further explore the ‘mental models’ that voters have of government debt and fiscal policy in general (Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2021). As calls for fiscal consolidation are growing louder again, it will be crucial to better understand how voters think about rising public debt.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the ERC Project ‘Political Conflict in Europe in the Shadow of the Great Recession’ (Project ID: 338875). This research design has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the European University Institute, Florence. Previous versions of this article were presented at the annual conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, 2018; the International Meeting on Experimental and Behavioral Social Sciences, 2018; the general conference of the European Consortium of Political Research, 2018; the Swiss–German–Austrian Dreiländertagung, 2019; the annual conference of the Council of European Studies, 2019; and the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, 2019. The article was also presented at seminars at the European University Institute, the University of Bern and the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies. We are very grateful for insightful comments and feedback from Despina Alexiadou, Klaus Armingeon, Lucio Baccaro, Dorothee Bohle, Charlotte Cavaille, Julian Erhardt, Lukas Haffert, Evelyne Hübscher, Achim Kemmerling, Hanspeter Kriesi, Erik Neimanns, Jonas Pontusson and Line Rennwald. Three anonymous reviewers and the editors of the EJPR further helped to improve the article. The usual disclaimers apply.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1: Operationalization of variables

Table A.2: Classification of political parties into five groups

Table A.3: Summary statistics

Table A.4: Case selection

Figure A.1: Share of respondents by income decile (left: all countries; right: by country)

Table A.5: Survey vote share versus actual vote share

Table A.6: Balance tests comparing treatment groups with the control group (linear probability models)

Figure A.2: Average support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and income/partisanship

Figure A.3: Average support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and country

Figure A.4: Support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and education/ideology

Figure A.5: Support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and age group

Table A.7: Average treatment effects on support for lower government debt (OLS regressions corresponding to Figure 1 in the main text)

Table A.8: The correlates of support for lower government debt (OLS regressions)

Table A.9: The correlates of support for lower government debt (OLS regressions with additional control variables)

Figure A.7: Estimated marginal means from conjoint survey experiment, pooled.

Figure A.8: Distribution of the ratings of all fiscal packages by changes of all attributes other than debt

Figure A.9: AMCEs from conjoint survey experiment with rating variable, pooled.

Figure A.10: Estimated marginal means from conjoint survey experiment with rating variable, pooled

Figure A.11: Estimated marginal means from the conjoint survey experiment by education

Figure A.12: Estimated marginal means from the conjoint survey experiment by ideology

Figure A.13: Estimated marginal means from the conjoint survey experiment by age

Figure A.14: Weighted average support for fiscal consolidation by treatment

Figure A.15: Weighted average support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and income/partisanship

Figure A.16: Weighted average support for fiscal consolidation by trade-off and country

Figure A.17: Weighted AMCEs from conjoint survey experiment

Figure A.18: Weighted marginal means from conjoint survey experiment by income and party

Figure A.19: Weighted marginal means from conjoint survey experiment by country