Introduction

In Estonian politics, the year 2014 was marked by a change in Prime Minister and governing coalition in March. It was followed by fairly quiet European elections in May, and preparations by political parties for the March 2015 parliamentary elections. In terms of issues, the year was dominated by security concerns raised by the conflict in Ukraine and increasing antagonism with Russia, as well as heated debates around the legalisation of same-sex partnerships.

Election report

European Parliament elections, May 2014

Estonia has six seats in the EP. The mandates are allocated in a single nationwide district with open list proportional representation using the d'Hondt formula.

The governing Reform Party (RE) managed to win two seats, despite its shaky support in public opinion polls. In 2009, it had won only one for former Foreign Minister Kristiina Ojuland. While Ojuland was expelled from the party following an internal voting scandal (see Sikk Reference Sikk2014: 115), the party still retained an MEP, as Vilja Savisaar-Toomast, the former wife of Centre Party (KE) leader Edgar Savisaar, had defected to RE. The two RE mandates were won by the former Prime Minister Andrus Ansip and Kaja Kallas, a prominent MP and the daughter of Siim Kallas, the European Commissioner at the time. As Ansip became the Vice-President in the Juncker Commission, he was later substituted by Foreign Minister Urmas Paet.

KE managed to regain a seat, but somewhat surprisingly, Savisaar, the dominant party leader, failed to win most preference votes. Instead, Yana Toom, a vocal defender of Russian speakers’ rights, became the first ethnic Russian MEP for Estonia. KE has long been highly popular among Russian speakers, even though most of its leaders have been ethnic Estonians. It is also seen as Russian-friendly because of its longstanding (if somewhat dormant) cooperation agreement with Putin's United Russia and Savisaar's links to Russian power circles (see Sikk Reference Sikk2011: 963). In March, Savisaar stirred controversy by failing to denounce Russia over Crimea and instead talked about Ukraine's ‘cudgel-wielders’ government’. While other leading members of KE voiced support for Ukraine, they avoided open confrontation with Savisaar. Still, KE's political opponents used the opportunity to hoist a campaign poster depicting Savisaar kissing Putin, modelled on the famous Cold War-era photo of Brezhnev kissing Honecker.

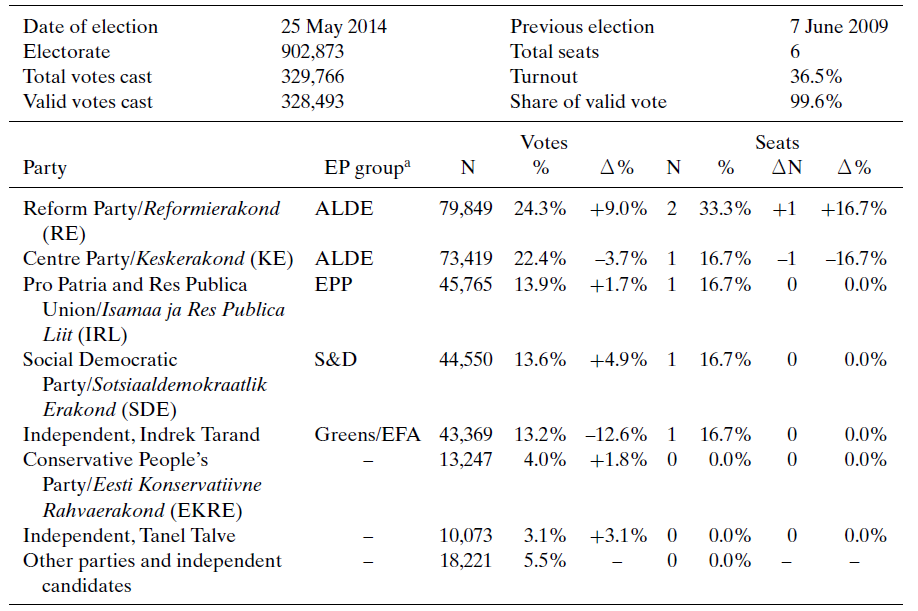

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Estonia in 2014

Note

a For acronyms, see the introductory chapter ‘Political data in 2014’.

Source: National Electoral Committee (2014).

KE's friendlier stance on Russia and attention to ethnic minority concerns was one factor behind the success of Yana Toom. Toom's success over the party leader may also be explained by Savisaar's declaration before the election that he did not intend to take up the seat even if elected. The practice of giving up seats in the EP or local councils has been so widespread among party leaders and cabinet ministers that a special term – ‘decoy ducks’ – has entered political parlance. Remarkably, during the campaign the question of whether candidates actually intended to become MEPs attracted possibly more attention than policy issues. IRL was the only major party to proudly declare itself free of ‘decoy ducks’.

Interestingly, political dinosaurs were dominant among the top candidates of main party lists. Savisaar, Marju Lauristin (Social Democrats, SDE) and Tunne Kelam (Pro Patria and Res Publica Union, IRL) had all been key leaders of independence movements in the late 1980s. Together with Andrus Ansip (RE), they won one-third of the preference votes between them. Outside of the parties, Indrek Tarand, a maverick independent candidate from 2009 (see Pettai Reference Pettai2010: 960) was also re-elected.

Cabinet report

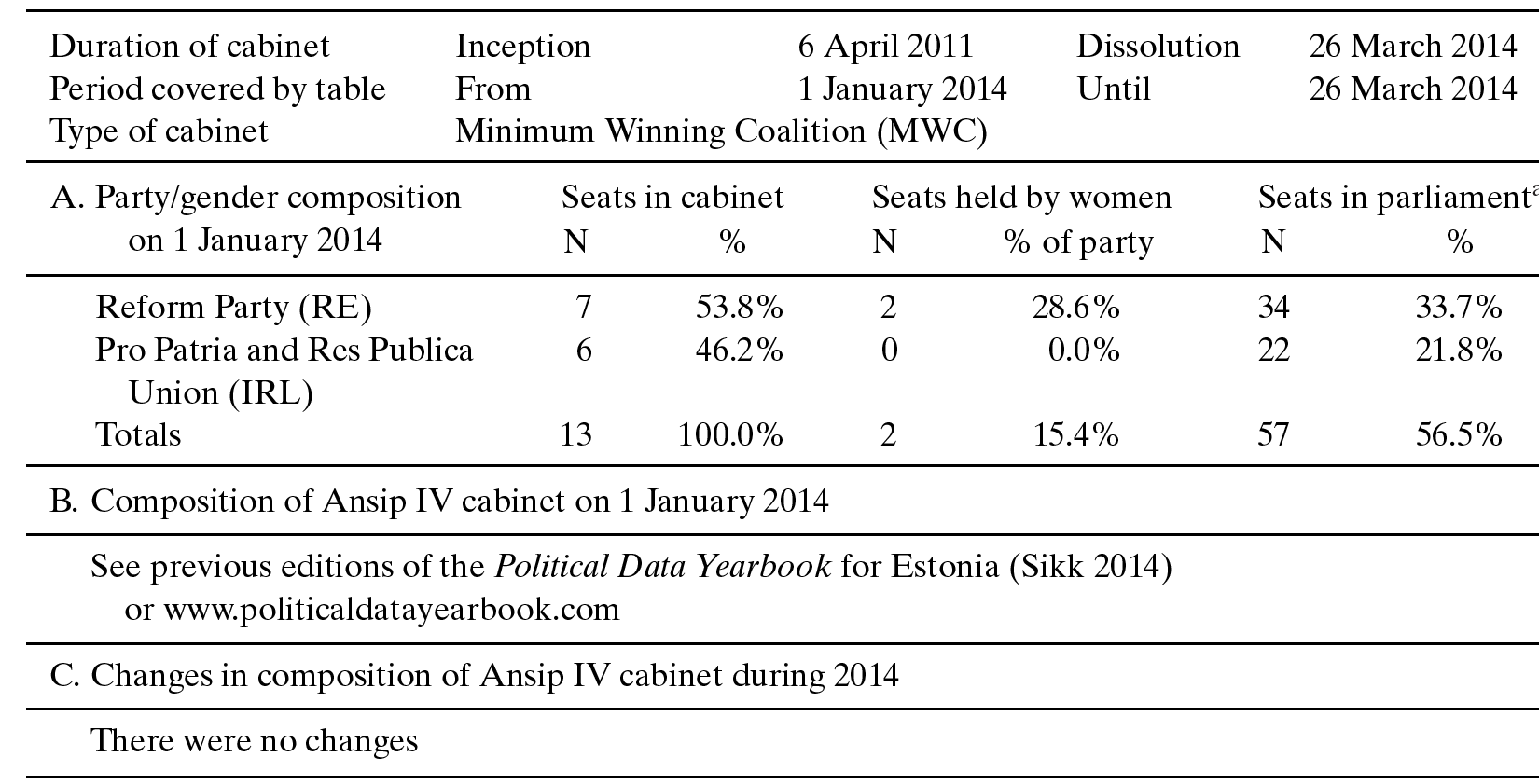

Ansip IV, ending 26 March 2014

In 2013, Andrus Ansip became the longest serving Prime Minister in the EU, having been in office since April 2005. In March, he resigned to give his successor a run-up to the 2015 Riigikogu election and, as became obvious later, to be the nominated for the European Commission.

RE nominated Siim Kallas, the sitting European Commissioner and former Prime Minister as the formateur for a new coalition. Early in the talks, Kallas swapped IRL (RE's erstwhile partner) for SDE for somewhat unclear reasons, as the centre-right IRL overall had a closer match in programmatic terms. During negotiations, Kallas faced accusations regarding letters of guarantee worth over US$100 million he signed as the president of the central bank in 1990s. He initially denied signing the letters that never appeared on the bank's balance sheet, but later admitted that he had foolishly done so. Kallas withdrew from coalition talks because of the mounting pressure that was obstructing talks. RE quickly and somewhat surprisingly nominated Taavi Rõivas, the Minister of Social Affairs, as a new formateur. Rõivas swiftly concluded the talks and at 34 years of age became the youngest Prime Minister in Europe.

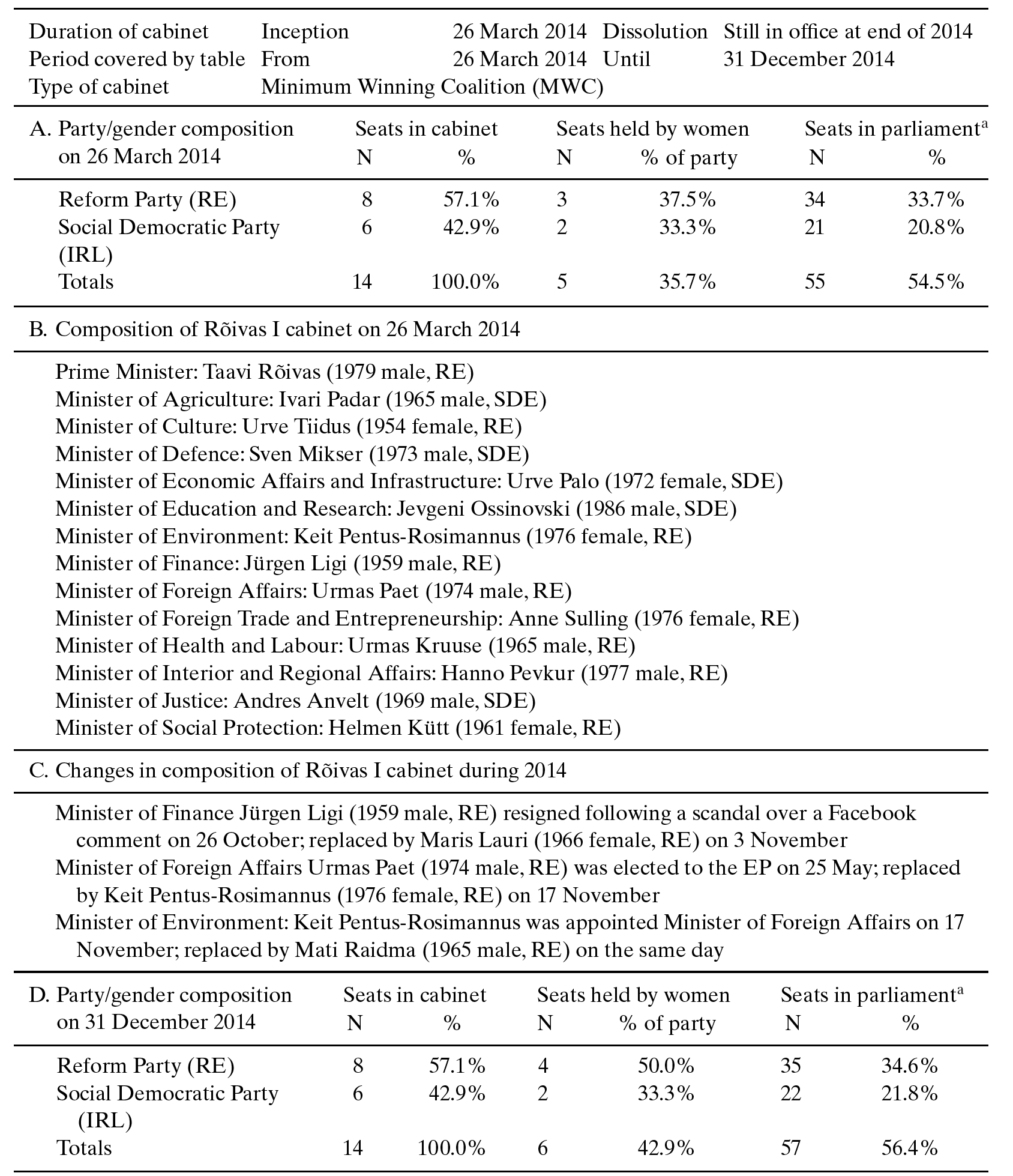

Rõivas I, March–November 2014

The cabinet increased in size as two portfolios were divided between ministers from RE and SDE. The portfolio of Social Affairs was split into Health & Labour and Social Protection; that of Economy and Communications into Economic Affairs & Infrastructure and Foreign Trade & Entrepreneurship. Jevgeni Ossinovski (SDE) became the first ever senior cabinet minister of ethnic Russian background and the first one not representing KE (a non-ethnic Estonian once served as a minister without portfolio for population affairs). Two ministers left the cabinet before the end of the year. Jürgen Ligi, the veteran Finance Minister was forced to resign following a careless comment on social media regarding Ossinovski's ethnic background. Ligi uttered that a ‘son of a migrant’ should refrain from commenting on the impact of the Soviet occupation on the country's development. He was replaced by Maris Lauri (RE), previously nonpartisan economic advisor to the Prime Minister. It was widely speculated that she was parachuted in, as the top contenders for the job were MPs who would have been substituted by Silver Meikar, the whistle-blower at the epicentre of a party funding scandal in 2012 (see Sikk Reference Sikk2013: 62), who had since left the party (ministers cannot be MPs in Estonia). In November, the veteran Foreign Minister Urmas Paet (RE) became an MEP and was replaced by Keit Pentus-Rosimannus (RE), previously the Minister of Environment. She was replaced by Mati Raidma (RE), the head of parliament's defence committee. Paet had vacillated publicly until early November between becoming an MEP and remaining the Foreign Minister (it is common in Estonia for prominent politicians to relinquish their seats, see Election report). Once again, one of the reasons why RE preferred Paet as an MEP was to block Igor Gräzin – a maverick Eurosceptic MP – from becoming a substitute member.

Following the inauguration of the new government and ministerial changes, the share of women in the cabinet increased considerably, to 43 per cent. This stood in stark contrast to the preceding five years when the cabinet had included no more than two female ministers. (However, the progress proved short-lived as the cabinet inaugurated after 2015 election again had only two female ministers).

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Rõivas I in Estonia in 2014

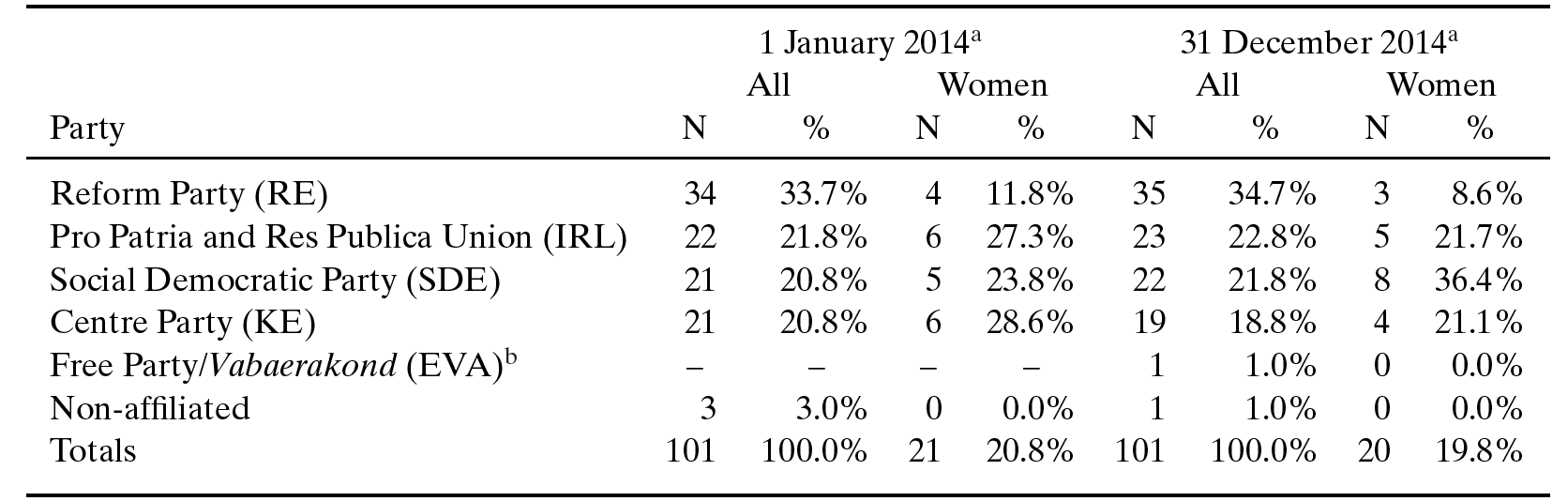

Table 4. Party and gender composition of parliament (Riigikogu) in Estonia in 2014

Notes

a Reflects de facto representation in the parliament; MPs formally cannot change factions.

b A defector from IRL.

Source: Parliament of Estonia (2014).

Parliament report

KE's ranks in the parliament continued to haemorrhage as two MPs left the party for SDE and IRL. It brought the party's number of seats down to 19 from the 26 seats won in the 2011 elections. The number of non-affiliated MPs dropped to just one after a deputy who had left KE in 2013 joined RE and another who had left IRL was elected the leader of the newly formed Estonian Free Party (EVA, see below). Such de facto changes are not reflected in official statistics because MPs can only leave their original party group, but cannot formally change factions.

Institutional changes

In January, the parliament introduced a number of changes to the Political Parties Act. The permanent membership requirement for new parties to be registered was lowered from 1,000 to 500. Public funding for extra-parliamentary parties was increased, but remained significantly lower in proportional terms compared to parliamentary parties. The reforms were originally initiated in 2012 by the People's Assembly (see Sikk Reference Sikk2013: 61–62), but criticised as the progress had been slow and the proposals had been significantly watered down. (For more details on the reforms, see Sikk Reference Sikk2014: 114).

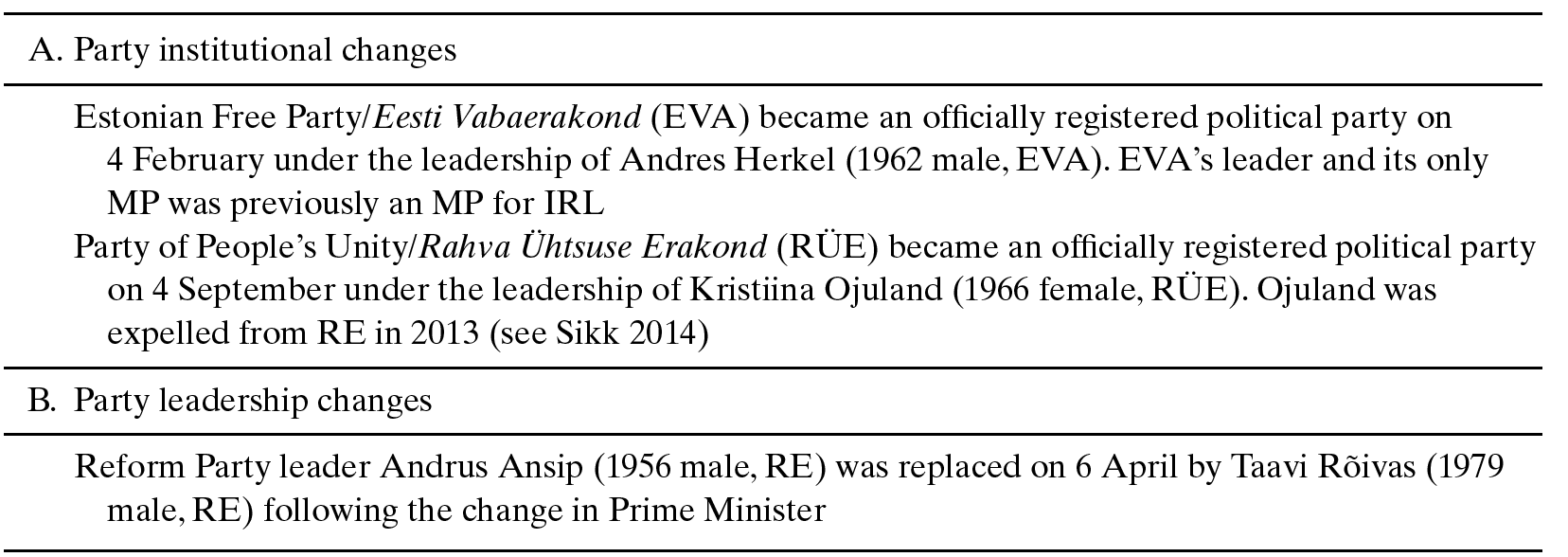

Partly aided by the changes, two new parties were registered in 2014 (see Table 5). The Estonian Free Party (EVA) was largely based on Free Patriotic Citizen, a 2011 non-party splinter from IRL. The Party of People's Unity (RÜE) was set up by Kristiina Ojuland, a former Foreign Minister and MEP expelled from RE in 2013 (see Sikk Reference Sikk2014: 115). EVA, the more organised of the two, was able to gather a significant following (and entered the parliament in 2015). RÜE – essentially a personal political vehicle for Ojuland – suffered from inception from the lack of publicly known faces as well as internal conflicts (and failed entirely in 2015).

At the end of the year, political parties were busy preparing themselves for the March 2015 parliamentary election. In September, IRL announced the former Prime Minister Juhan Parts as its prime ministerial candidate (instead of Urmas Reinsalu, the party leader). In October, prominent KE politicians toyed with the idea of nominating Kadri Simson, the chair of KE's parliamentary group, as their prime ministerial candidate. That might have opened up coalition opportunities, as cooperation with Savisaar has been ruled out by all other major parties, but was also a sign of a sprouting coup. Eventually, KE's board confirmed Savisaar as its prime ministerial candidate.

In October, Eerik Niiles Kross, the deputy leader of IRL and a recent popular mayoral candidate in Tallinn (see Sikk Reference Sikk2014: 112), unexpectedly defected to RE. Kross has been a controversial figure, sought by Russia and barred from entering the United States (for reasons known only to a handful of top politicians). Speculations over his motives abounded and many suspected that he was somehow blackmailed into switching parties. However, Kross's membership and prospective candidacy in parliamentary elections stirred animosity within RE. Much less controversial new recruits to RE included two former commanders-in-chief. At the same time, political parties, in particular IRL and SDE, recruited prominent journalists, five of whom went on to become novice MPs in 2015.

Issues in national politics

The troubled relationship with Russia deteriorated further in the wake of the crisis in Ukraine. In February, the countries signed a border treaty, promising an end to a longstanding stalemate. Yet a year later it still remained to be ratified. In September, tensions escalated as Russian forces abducted an Estonian security service officer on the Estonian side of the border and kept him in custody. In response to the worsening security situation, NATO stepped up its military presence in Estonia, including increased air defence patrols and the deployment of American ground forces. In September, President Obama visited Estonia to reassure the Baltic states of NATO's security guarantees.

Stakes were high in the information war. To counter the anti-Western propaganda of Russian television channels that remained popular among Estonia's Russian-speakers, the establishment of a Baltic or pan-European Russian-language channel was discussed. More tangibly, the opening of a Russian-language television channel in September 2015 was announced by the Estonian Public Broadcasting. Thus far, it had only operated a Russian radio channel and run a very limited number of Russian language programmes on its television channels.

In October, the Estonian parliament legalised same-sex partnerships – the first former Soviet republic to do so. The bill was passed very narrowly (40 votes in favour and 38 against), with nearly all MPs from SDE and most from RE voting in favour, and most KE as well as all IRL deputies being opposed to the bill. The vote in the parliament was preceded by a long and heated public debate, with massive mobilisation of both sides to the argument on the social media and mass demonstrations against same-sex partnerships.