Maya quarries were sites of resource extraction as well as sites of labor, collaboration, and personal relationships. As Mary E. Clarke and Rachel Gill (this issue) note, the people conducting construction activities typically factor into archaeological study as “invisible persons,” if at all. When they are included, we often rely on general terms like “laborer” instead of specialist terms, many of which Clarke and Gill illuminate. Here, we will use the term “laborer” since we highlight collective groups of specialists and non-specialists, for which we lack specific Mayan terms. Despite that constraint, we find that the various non-academic/public audiences for archaeology are interested in these laborers. Who were they? Why did they labor? We focus on ways in which investigations of quarry and other construction laborers can be made accessible to public audiences. Further, we consider how interpretation for the public, in turn, nourishes the production of scientific knowledge.

To study construction and labor, we employ architectural energetics, a methodology used to quantify built forms. The outputs, while hypothetical, can clarify scale, give an estimated measure of resource use, and aid in sociopolitical interpretation. Detailed tables efficiently present energetics data for scholarly comparison. The public audiences for archaeology rarely find these banal charts of tedious data engaging and stimulating. We gravitate towards public education and relevance because we have each experienced the ways in which archaeological information is twisted and/or ignored. Television shows, movies, and even conversations with local collaborators demonstrate that we archaeologists need to do a better job communicating our findings to the public. We have found that expressing energetic results in narrative formats can aid in combating misinformation and building public awareness of ancient histories.

Following important precedents in archaeological narrative, this study offers two cases of how quantitative methodologies can intersect with storytelling. The first concerns quarrying and transporting limestone at Early Classic Naachtun, Guatemala (Figure 1), and the animated story called “Sous les jupes des pyramides mayas”, illustrated by Astrid Amadieu and published on the Past and Curious YouTube channel (2019). The second case focuses on extracting sascab (powdered limestone) at Late Classic Xunantunich, Belize (Figure 1), and a written narrative called “Sak's Story.”

Figure 1. Map of the Maya area locating major sites including Naachtun and Xunantunich. Map by Jean François Cuenot.

Stories in Archaeology

There have been many dialogues about the rationales for and effectiveness of public outreach in archaeology (e.g., Castaneda and Matthews Reference Castaneda and Matthews2008; Kaeser Reference Kaeser2016; Little Reference Little2002; Merriman Reference Merriman2004; Moshenska Reference Moshenska2017, Richardson and Almansa-Sanchez Reference Richardson and Almansa-Sanchez2015; Skeates et al. Reference Skeates, McDavid and Carman2012; in Maya scholarship: Breglia Reference Breglia, Jameson and Baugher2007; Seligson and Farah Reference Seligson and Farah2018). Government-funded and/or mandated archaeology often requires archaeologists to engage with public audiences (the ultimate funders of government work) (Praetzellis Reference Praetzellis and Smith2014:5136). Previous versions and recent updates to the Society for American Archaeology's “Principles of Archaeological Ethics” include “Public Education and Outreach,” and emphasize various facets of public engagement and accountability (2024; see also Childs et al. Reference Childs, Douglass, Miller, Rakita, Scheinsohn and Yellowhorn2018). Equivalents by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France (Comité d’Éthique du CNRS 2017:16–17) reflect similar ethics. Yet, researchers may not necessarily feel the need to engage with the public. Despite the above ideals, outreach activities are strongly undervalued in career advancement and tenure compared to scholarly publishing (e.g., Jensen and Croissant Reference Jensen and Croissant2007:2,6; Mickel Reference Mickel2011:82–83). This paradox makes many question the sustainability of the discipline and how to ensure that the public benefit of archaeology does not go unnoticed and defunded (Ellenberger and Richardson Reference Ellenberger and Richardson2018; Moshenska and Burtenshaw Reference Moshenska and Burtenshaw2010; Newman and West Reference Newman and West2014).

One long-established facet of public engagement is storytelling. In fact, narrative plays a role in all interpretation and in most forms of archaeological writing (Mickel Reference Mickel2015; Praetzellis Reference Praetzellis1998; van Helden and Witcher Reference van Helden, Witcher, edited by van Helden and Witcher2019). To consider where that storytelling is more intentionally developed, Praetzellis (Reference Praetzellis and Smith2014:5136) traces the transitions from modernist/processual to postmodern/post-processual trends that wrestled with the metanarratives of cultural evolution as a marker of the burgeoning of narrative forms (alongside turning from elite-centric research). Allison Mickel (Reference Mickel2011:29–34) defines several categories of archaeological stories. Those most relevant here are her “imagined stories,” such as James Deetz's (Reference Deetz1996) In Small Things Forgotten and Janet Spector's (Reference Spector1993) What This Awl Means, as distinct from stories centering archaeologists as protagonists, such as Kent Flannery's (Reference Flannery1982) “The Golden Marshalltown” (Mickel Reference Mickel2011). Inspired by the traditions of indigenous oral storytelling, Spector's story, for example, presents context, association, use, and deposition but turns away from academic stoicism and actively engages emotion (Mickel Reference Mickel2011, Reference Mickel2012). Public audiences respond to this approach and recognize the impact of archaeology in their understanding of history and culture (Praetzellis Reference Praetzellis and Smith2014:5136).

For the purposes of this article, we center examples relevant to the ancient Maya. Public audiences are certainly aware of fantasy stories like the “Indiana Jones” franchise and Mel Gibson's “Apocalypto.” Are these the sorts of stories the public should connect with the Maya and the ancient past? While they may build interest, many scholars argue that such stories ultimately harm the perception of cultural histories, identities, and the discipline itself (Mickel Reference Mickel2011:17–18; Seligson and Farah Reference Seligson and Farah2018 on “Indiana Jones” and Cojti Ren Reference Cojti Ren and Nicholas2010; Hansen Reference Hansen, Chacon and Mendoza2012; Lovgren Reference Lovgren2006; Weismantel and Robin Reference Weismantel and Robin2006 on “Apocalypto”). In particular, the stereotypical representation of ancient Maya communities affects people who identify as Maya today (Castaneda Reference Castaneda2004; Cojti Ren Reference Cojti Ren and Nicholas2010).

Some stories have been published to educate and combat negative stereotypes. For example, in 2019 graduate students of the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne launched the Past and Curious project for public audiences (Beaulieu et al. Reference Beaulieu, Debels, Jean and Rueff2021). Past and Curious offers archaeology-related professional-quality animated videos on YouTube. All stories are proposed by advanced doctoral students or post-doctoral researchers, based on their research in various global contexts, including the Maya world. Stories and scientific content are peer-reviewed and all video descriptions include bibliographies.

Past and Curious videos have been successful on YouTube, reaching an average of 7,600 views. This viewership appears to derive from teachers and schoolchildren in France, since many of the most viewed episodes relate to the history curriculum of French “sixth grade” (11/12 years). This may have been particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic when online resources were so useful. Some researchers argue that no public demand originally exists to justify public outreach for archaeology, but that, instead, the archaeologists themselves have created and stimulated the demand (Jurdant Reference Jurdant2006; Kaeser Reference Kaeser2016). Reflection upon the recent impact of resources like those from Past and Curious may help us reconsider what the public expects or needs from archaeologists.

Stories produced by Mesoamericanists often derive from investment in and collaboration with local and descendant communities. For example, Mélanie Forné published comics for Guatemalan audiences, including Ix Tz'unun in the Prensa Libre (Prensa Libre Reference Libre2013) and the trilingual Le Voyage de Santiago/El Viaje de Santiago/Lix be laj Y'ak (Forné Reference Forné2018). Richard Leventhal's collaborative community project in Tihosuco, Mexico, produced comic books about the Caste War period (Morgan and Leventhal Reference Morgan and Leventhal2020). While archaeologists facilitated publication, community members chose story topics and developed imagery. Fajina Archaeology Outreach produced a trilingual children's storybook called To the Mountain! in 2015 (Figure 2). Fajina was a public outreach project focused on the local communities of western Belize and a collaboration between indigenous and non-indigenous archaeologists. After initial print and open access online publication, Fajina collaborated with teachers and schoolchildren of San Antonio village, Belize, to develop an audiobook of the story. This collaboration with native Yucatec speakers helped inform future projects and the value of archaeological storytelling among Maya descendant communities. More recently, Edith Dominguez, Santino Rivero, and Pedro Rafael Mena (Reference Dominguez, Rivero and Mena2021) created the time-traveling zine called Teotihuacan: Un viaje magico in collaboration with the Tlajinga Teotihuacan Archaeology Project.

Figure 2. Cover of To the Mountain! Produced by Fajina Archaeology Outreach. https://fajina.wordpress.com/tothemountain/

Public education is the primary goal of these stories. Many of these previous examples and those discussed below combat the false, fantasy narratives of “Indiana Jones” and “Ancient Aliens.” They carefully consider the humans, not aliens, who built Maya monuments. While the “ancient astronaut” theories may seem harmless entertainment at first glance, they nourish a racist vision of ancient societies and their descendants, unbelieving that actual people of the past were able to achieve monumentality without intervention. Storytelling is one way to combat such misinformation, benefiting local and descendant communities moving forward.

Storytelling can also benefit scholars as a breeding ground for research ideas and insights (van Helden and Witcher Reference van Helden, Witcher, edited by van Helden and Witcher2019). As Praetzellis (Reference Praetzellis1998:1) notes, storytelling requires “archaeological imagination” to present evidence and invent informed context for that evidence. There are knowns and unknowns in all archaeological inquiry, including storytelling. The very act of attempting to build a holistic picture of the past, so much so that you can develop an engaging and illustrated story about it, is a form of creative research (Mickel Reference Mickel2011:50). The “texture” (pardon the pun) that the storyteller offers to archaeological data may illuminate previously unconsidered research questions or demonstrate an uninterrogated misunderstanding. For example, Richard Hansen (Reference Hansen, Chacon and Mendoza2012) describes how actually building a Maya pyramid for the film “Apocalypto” impacted his thinking about architectural lime requirements. Both case studies below, founded in the data-driven methodology of architectural energetics, are examples of these (admittedly unexpected) outcomes of our storytelling experience. This taught us that storytelling sits at the intersection of a mutually beneficial relationship fulfilling needs for both the public and scholars.

Architectural Energetics

Architectural energetics is a well-established quantitative approach to ancient construction applicable to any context (Abrams and McCurdy Reference Abrams, McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019). The methodology analyzes evidence of construction activities to quantify the scale of building according to “costs,” such as material and/or labor costs (Abrams Reference Abrams1994). Thus, it is a framework primarily focused on the economics of building. When applied to Maya architecture, interpretations usually focus on political economy (McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016:30–33), to elucidate “labor investment” (Abrams Reference Abrams1994).

Labor investment refers to the quantifiable projection of construction time and labor populations. Sources of data include architectural measurements, construction phasing, resource availability, and work rates (Abrams and McCurdy Reference Abrams, McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019: Table 1.1). Results are typically presented in estimates of person-days (p-d) or person-hours (p-h). Within the Maya context, these projections are often applied as evidence for labor control by the sociopolitical elite and often hinge on interpretive frameworks of labor tribute systems and conspicuous consumption (e.g., Hansen Reference Hansen, Matheny, Janetski and Nielsen2013; Trigger Reference Trigger1990). In our studies of Naachtun and Xunantunich, we applied energetic analysis to address sociopolitical questions about Classic period Maya communities, inclusive of elites and non-elites, aligning with the trajectory of energetics research in Old World contexts (e.g. Brysbaert Reference Brysbaert2015, Brysbaert et al. Reference Brysbaert, Klinkenberg, Gracia-M and Vikatou2018; DeLaine Reference DeLaine1997; Turner Reference Turner2020).

Person-day estimates are fundamentally hypothetical. Further analyses compound uncertainty and potential errors. While we must understand this inevitable issue, it should not keep us from pursuing the possibilities that such analyses can offer about ancient labor systems. Asking who laborers were, what they did, and why they did it can illuminate previously uninvestigated aspects of Maya society and history. Examinations of such questions outside ancient Maya contexts take advantage of construction ledgers and bureaucratic documents, whereas our studies involve more projection and “archaeological imagination.” Below, we review our energetic results and how such results can be “translated” into stories that go beyond the numbers and in turn, how such stories feed scientific investigation.

Creating Stories

Unfortunately, there is no manual for writing archaeological stories (yet). Storytelling is a reflective act (Praetzellis Reference Praetzellis and Smith2014:5136); thus, to build our stories, we asked ourselves a series of questions. Below, we briefly outline the question-focused methodology by which we both assessed the quantitative outcomes of energetics, considered their value for public audiences, and created “imagined stories” of historic fact and informed “texture.”

The first and potentially most important question is: Who is the audience? There are two major archaeological publics/stakeholders that we considered: 1) local and/or descendant communities with heritage ties to and various interests in specific archaeological sites; and 2) the public local to the archaeologist's and/or funder's institutional setting (i.e. taxpayers who support initiatives to fund research beyond their local community). In Europe, these publics may be the same. In most regions, descendant communities are distinct from or form a small portion of the funding public. Outreach to taxpayers often targets not the actual tax-paying citizen but their children, the younger generations starting to consider the historical and global contexts of their local contemporary life. Stories geared towards children are one of the most accessible means by which archaeological knowledge can be shared, since adults can also benefit from them. Both our stories feature young protagonists and focus on the point of view of young people. Adults may also be a target audience if the content is not suitable for younger audiences or if deeper intellectual engagement is a goal of the storytelling project.

Considerations of audience immediately implicate questions of existing knowledge. Descendant communities often have existing knowledge about cultural contexts and awareness of, if not literacy in, archaeologically relevant languages. Thus, stories meant for them may not require as much background or setup. Stories for the funding public often require significant context and the use of a language that may not be historically or culturally relevant to the archaeological location, although language awareness/acquisition can be facilitated through multilingual projects.

Most importantly, storytellers must reflect upon their positionality relative to the audience (Mickel Reference Mickel2011:68–74). What power dynamics and/or historical inequalities factor into that relationship? What potentials for harm or conflicts of interest may be present? What does the audience seek from storytellers? In the case of some descendant communities, for example, archaeologists who do not share community membership or valued identities may not be welcomed as storytellers. This has been the experience of Iyaxel Cojti Ren (Reference Cojti Ren and Nicholas2010), a young university-trained archaeologist of Maya descent. She has been “ignored or discounted” as a source of cultural information by “Mayan leaders and spiritual guides who refuse to recognize any authority who speaks about the past except those who have traditionally done so…” (Cojti Ren Reference Cojti Ren and Nicholas2010:90).

Storytellers who originate from and/or relate to colonial contexts, either of the past or continuing, must rigorously consider the nature of their relationship with local and descendant communities. As Richard Leventhal and others have found, the most effective outreach engagements result from asking descendant communities what they want to see, who they want to undertake that work, and how such work should unfold (Morgan and Leventhal Reference Morgan and Leventhal2020). It is worth also considering whether non-descendant voices should be involved at all in telling stories, or offering public information, about communities from which they do not originate. These debates go beyond the scope of this paper but certainly implicate the stories presented herein and the subjectivities of both authors. We respectfully acknowledge that our positionalities may be problematic, with respect to the stories we have created, even in ways that we do not yet recognize.

As considerations of audience and positionality unfold, the question of narrative format will also arise. Today, choices abound: print text, digital text (accessible online or not), audio recording (e.g. audiobooks, podcasts, etc.), video (documentary, live-action, animated, etc.), and/or any of the above offered through social media (e.g. Instagram stories). In our experience, video appeals more to younger audiences whereas written formats are appreciated more among adults. Podcasts and social media are an increasingly popular way to reach millennials and related generations.

One of the most important questions, and the one that is often the easiest to arrive at, is about content: What is missing/lacking in public awareness? This is the question that typically motivates an archaeologist to become a storyteller, to fill those gaps, determined via consultation with stakeholders, in engaging and educationally impactful ways. As examples, our stories focus on construction because our interactions with Guatemalan and Belizean communities indicated that the topic was a familiar one, especially with kids, since most have at least one relative involved in the construction industry. These relatives often have to travel for their jobs, living apart from the family for long periods. These situations resonated with our investigations of ancient Maya construction labor. We found that new understandings of the past could be forged through relevance to contemporary life among local and global publics.

With respect to the ancient Maya construction context and energetics results, our content priorities included: 1) the scale of the laboring population (with our results demonstrating such scales are often overblown when just estimated off the cuff); 2) who in Maya society constituted the labor force and why they were part of it; and 3) the nature of architectural construction as conducted by the Maya (through a sequence of processes, each dependent on the stage before it and independent of any “mysterious” external factors). The lack of understanding of these topics is seen across both descendant communities and funding publics; thus our stories, each targeting a different primary demographic, converged into similar territory.

Another important question revolves around the balance of evidence and imagined context, what Mickel (Reference Mickel2011:34) represents as a contrast of authenticity and invention. This is one of the most subjective facets of storytelling, dependent on archaeological expertise, the nature of data available, and judgment. Below, we discuss some examples of how this balance evolved in our stories and how attempting to weight our stories more on the side of authenticity led to new considerations and impacted our research.

Lastly, an important question to consider is: at what point in the research process should storytelling start? The obvious answer is after all the research has been finalized. However, as all archaeologists know, research is never “done.” There is always more to investigate, more analysis to undertake, questions that remain unanswered. We must consider when the public should benefit from our work. Is it only after its “done?” In our experience, our stories developed prior to any endpoint (i.e., the submission of our dissertations). They were part of our process and informed the path our research took. Below, we explore our case studies in detail and where this reflective methodology impacted our work most.

Naachtun and “Sous les jupes”

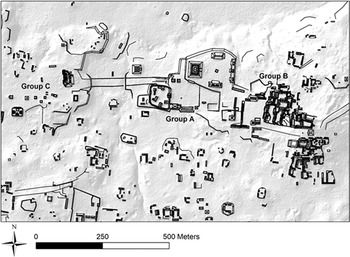

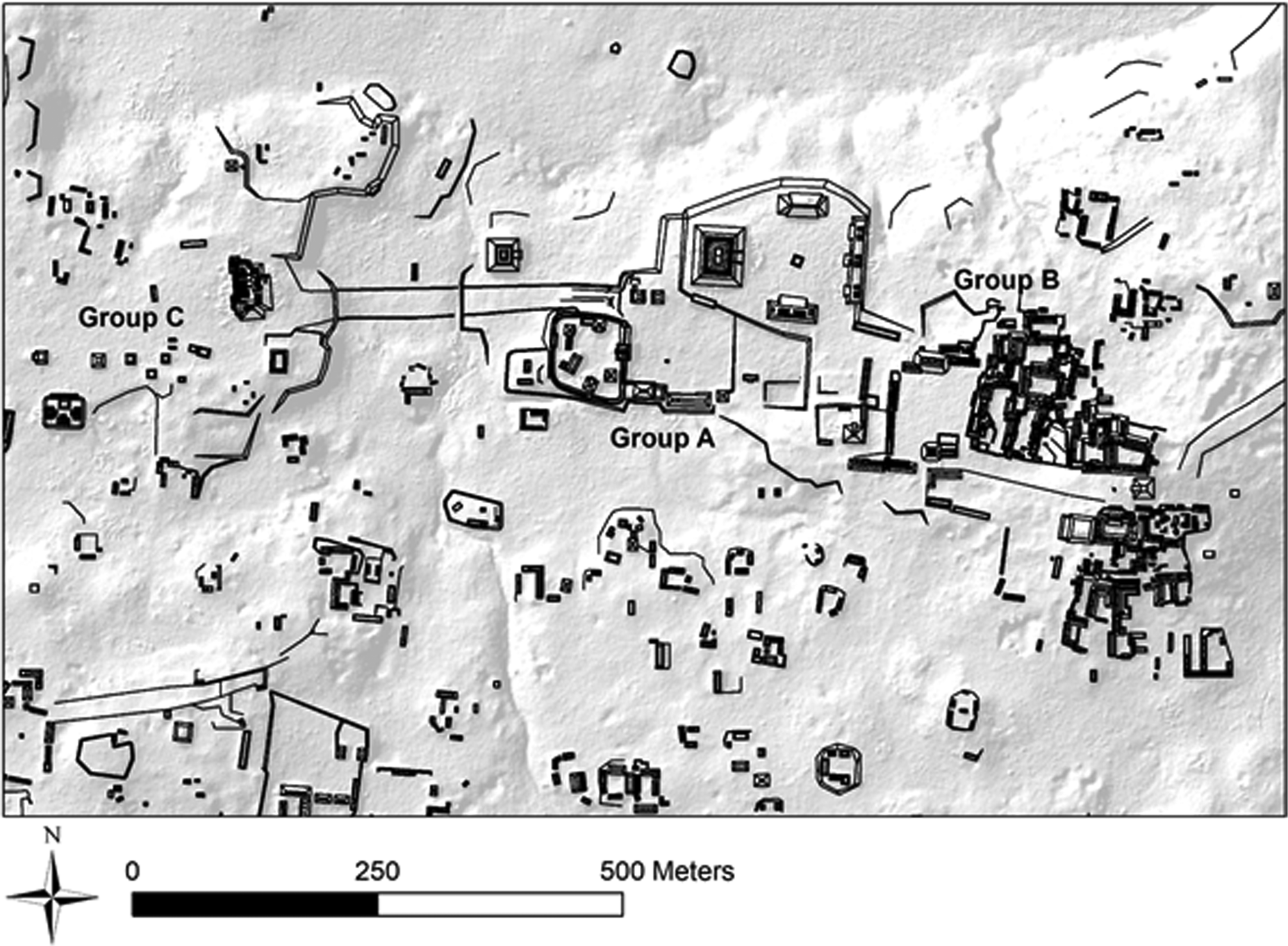

Hiquet (Reference Hiquet2020; Hiquet et al. Reference Hiquet, Nondédéo, Nimatuj, Michelet, Gladys and Zacarías Capistrán2023) estimated construction costs of public architecture at the Classic period major center of Naachtun, north of Petén. Groups A and C of the epicenter (Figure 3) were built during the Early Classic period and are mainly composed of monumental public architecture, including an E Group and a triadic complex. Group B dates to the Late and Terminal Classic. It is mainly residential, with many vaulted houses, including royal palaces.

Figure 3. Map of Naachtun. Map by Julien Hiquet and Naachtun Archaeological Project.

The energetic approach was used to analyze the clear apex of monumental construction during the Early Classic period at Naachtun. Architectural detail of each construction stage is still poorly known for most buildings at Naachtun. Given that constraint, Hiquet's study analyzed the overarching cost of each building (comprising all stages). Hiquet compared this comprehensive labor demand to local population size to assess the process of urbanization, in terms of both top-down demand and bottom-up interests.

This research inspired “Sous les jupes des pyramides mayas” on Past and Curious (2019). The story centers on a young boy called 3-rain, living during the Early Classic period at Naachtun and participating in his first public construction campaign. 3-rain is accompanied by his uncle, 12-flint, a veteran of construction at Naachtun. 12-flint explains that he and 3-rain's grandfather helped build earlier stages of the pyramid 3-rain will help enlarge (Figure 4). 3-rain and his uncle also meet the latter's daughter, carrying water for the mixing of mortars (Figure 5). Hiquet decided to represent most of the workers as men, according to ethnohistorical and ethnographic data (Abrams Reference Abrams1994;Redfield and Villa Rojas Reference Redfield and Rojas1934; Ternaux-Compans Reference Ternaux-Compans1839) but did not exclude women. Cultural prohibitions may have governed a gendered division of labor for some activities (e.g., lime burning [Magaloni Kerpel Reference Kerpel and Isabel1996; Redfield and Villa Rojas Reference Redfield and Rojas1934; Schreiner Reference Schreiner, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2003]; for a wider cultural analysis, see Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2008:8) but likely did not mean women were excluded from construction tasks entirely. Overall, 3-rain's story reflects known Maya construction technologies, labor population sizes during the Early Classic, and relationships among laborers. Hiquet's Naachtun investigations led to and were impacted by creating this narrative.

Figure 4. 3-rain and 12-flint arrive at the building site in “Sous les jupes des pyramides mayas.” Courtesy of Past and Curious. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-KDcg25nbg

Figure 5. Stone transportation scene in “Sous les jupes des pyramides mayas.” Courtesy of Past and Curious. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-KDcg25nbg

At Naachtun, monumental construction and a high density of residences created a high demand on limestone resources. Naachtun lies on a hilly karstic landscape overlooking a bajo (wetland). Limestone is present almost everywhere and many outcrops would have been visible or accessible under a thin soil mantle; thus, extraction occurred in situ. A lidar survey of 135 km2 centered on Naachtun and its hinterland enabled us to identify 9,594 visible prehispanic quarries (Figure 6), with a density of over 70 quarries per km2 or 90 per km2 if bajos are excluded. This doesn't account for the quarries that were filled and covered by plastered floors and other buildings.

Figure 6. Localization of quarries around the epicenter of Naachtun. Map by Julien Hiquet and Naachtun Archaeological Project.

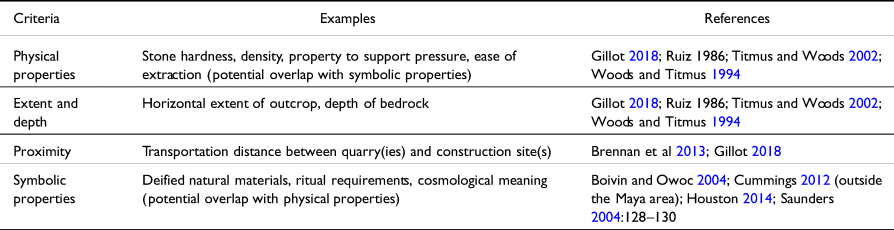

Hiquet's study focuses on the quarries exploited for monumental public construction and the transportation of extracted materials. Transportation is often considered the costliest task in other calculations (Abrams Reference Abrams1987:487–499, 1994:45, 1998; Murakami Reference Murakami2010; Udy Reference Udy1959:25; Webster and Kirker Reference Webster and Kirker1995:Tables 3 and 5), and is the task for which the participation of unspecialized corvee laborers is least in question (compared to quarrying or lime production that demand special knowledge, for which the degree of specialization is still discussed [Abrams Reference Abrams1987:490–492; Clarke and Gill, this issue; Russel and Dahlin Reference Russel and Dahlin2007; Seligson et al. Reference Seligson, Negrón, Ciau and Bey2017; Woods and Titmus Reference Woods, Titmus, Laporte and Escobedo1994:307]). Of the many criteria that can explain the choice of a quarry (some of which are listed in Table 1), transportation cost may be the easiest to assess in actual conditions.

Table 1 Some of the criteria likely influential in the choice of quarry location for facing stones.

Some Maya quarries stand out for the quality of their material, but the abundance of limestone regionally likely made the choice of remote quarries inconvenient and rare. An extreme case would be the strangely isolated (and undated) quarry reported by Beekman (Reference Beekman1992) in the Usumacinta drainage, located 5 km away from the nearest site. Cases of even longer distances (dozens of kilometers or more) are known elsewhere (e.g., Olmec region: Hazell Reference Hazell2011; Hazell and Brodie Reference Hazell and Brodie2012; Welsh bluestones moved to Stonehenge: Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Bevins, Ixer, Pollard, Richards, Welham, Chan, Edinborough, Hamilton, Macphail, Schlee, Schwenninger, Simmons and Smith2015), but they have not been reported for Maya architecture, only for freestanding monuments (Brennan et al. Reference Brennan, King, Shaw, Walling and Valdez2013). Archaeologists, especially working in Lowland contexts, often record close proximity between quarries and construction sites, so much so that quarries sit at the foot of a pyramid. On this basis, it is logical to think that the Maya extracted construction materials from quarries as close as possible to a building site, as illustrated in “Sous les jupes” (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Simplified illustration of a limestone quarry, highlighting the types of tools and practices commonly seen in Maya quarries. A painting of unknown origin depicting a heavily populated Maya construction site, with quarrying occurring in close proximity to the construction site, was used as inspiration by the illustrator. Courtesy of Past and Curious. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-KDcg25nbg

The development of the quarrying scene led Hiquet to recognize that the spatial layout of some sites complicated the task of quarriers. Of course, in many cases quarriers exploited limestone removed during leveling and site preparation. Nevertheless, as most buildings were constructed without foundations upon plastered plazas, the direct spatial exploitation of bedrock in city centers rapidly reduced as buildings and plazas occupied more space over time. By choice or constraint, the Maya sometimes had to extract materials from distant quarries. How did these factors impact construction time and labor cost?

To explore these questions and the impact of quarry location and labor, Hiquet first considered the triadic complex of Naachtun (Figure 8). Its platform is 4 m high, 45 m long, and 35 m wide. The three temples reached a height of about 10 m overall. While it was a main politico-ritual focus of Classic period activity at Naachtun (Hiquet, Reference Barrientos, Nondédéo, Michelet, Begel and Garrido2018; Nondédéo et al., Reference Nondédéo, Lacadena, Garay, Kettunen, López, Kupprat, Lorenzo, Cosme and Ponce de León2018; Šprajc Reference Šprajc2021), the triadic complex is relatively small.

Figure 8. The triadic complex of Naachtun and its adjacent quarries. Map by Julien Hiquet and Naachtun Archaeological Project.

Hiquet considered that most of the blocks for the walls and fills were carried by workers via tumpline (as in Figure 5). Transportation costs were calculated with the widely accepted formula used by Aaberg and Bonsignore (Reference Aaberg, Bonsignore, Graham and Heizer1975) and Abrams (Reference Abrams1994). Nevertheless, heavy cornice and doorjamb blocks as well as large amorphous blocks in the platform fills were probably transported upon stretchers. For those collaborative transport needs, the experimental measures provided by Titmus and Woods (Reference Titmus, Woods, Laporte, Escobedo and Arroyo2002:199) were used.

Hiquet (Reference Hiquet2020) estimates the whole energetic cost of this triadic complex as between 75,000 and 80,000 p-d. Transportation costs in Hiquet's analysis did not significantly exceed other costs, unlike other energetic studies. For example, the well-known analyses of monumental construction at Copan, Honduras (e.g., Abrams Reference Abrams1994:18; Webster and Kirker Reference Webster and Kirker1995:370) incorporate transportation costs from a remote Late Classic quarry (600 m from the epicenter) and relatively low use of lime-based materials. These factors resulted in comparatively high transportation costs. At Naachtun, Gillot and Michelet (Reference Barrientos, Nondédéo, Michelet, Hiquet and Garrido2016:451) identified clear traces of limestone extraction close to the east side of the Complex (Figure 8), suggesting the builders probably chose to minimize transport costs. The quarry was not excavated so we do not know its exact surface nor volume. Nevertheless, the surface currently visible measures approximately 1,800 m2.

The total volume of stone required to construct the whole triadic complex amounts to approximately 2,100 m3, with 1,500 m3 of fill and 600 m3 of facing stones. With an average distance of transport of 100 m, transport of those stones represents 1,300 p-d (less than 2 percent of the total cost). Sixty-five laborers could have carried the required amount of stone in approximately 20 days. Construction of the triadic complex at Naachtun is an important case study to challenge the previous assumptions that transportation would have always been the largest cost in Maya monumental construction. Including earth, sascab, and water, the total transportation cost is 9,252 p-d, approximately 12 percent of the total cost, well below the percentages obtained by Webster and Kirker's (Reference Webster and Kirker1995) simulations, for example. The choice to depict 3-rain working in a quarry directly adjacent to the construction site with transporters in close proximity to him in “Sous les jupes” derives directly from these findings and is a simplified way of challenging stark illustrations of shackled slaves trekking limestone blocks through the jungle over years and years.

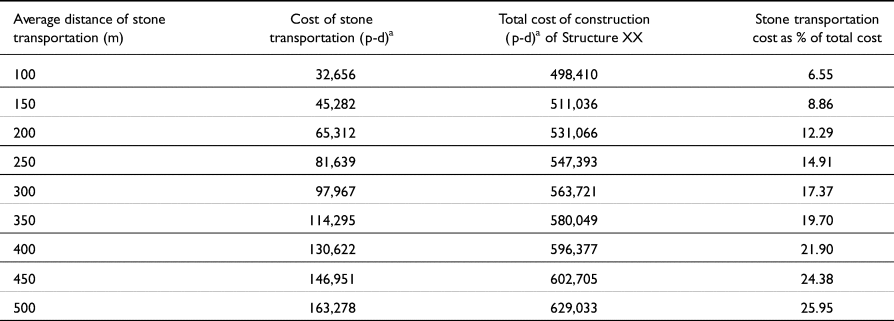

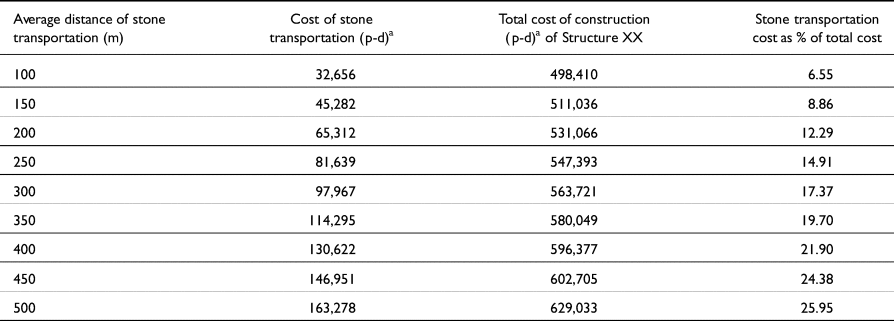

Hiquet also considered the energetic cost of Structure XX, Naachtun's main pyramid in the E Group (Figure 9). Compared to the triadic complex, Structure XX required much more stone extraction. For the last stage of its construction, Hiquet estimates that almost 25,000 m3 of stones were used (23,000 for the fill, 2,000 for the facing). This stage was built on top of existing plazas, which prevented the extraction of material in the immediate vicinity (see Figure 9). Thus, the quarry(ies) supplying stone for Structure XX would have been farther afield than those for the triadic complex and must have been very ample extraction sites, probably thousands of square meters. These constraints and the configuration of the terrain probably necessitated carrying stones over hundreds of meters. The data presented in Table 2 consider how the transportation cost and total construction cost of Structure XX increase as the average distance for stone transportation increases at Naachtun.

Figure 9. Layout of Structure XX at Naachtun. Dashed areas represent already existing plazas, causeways, and swamps unsuitable to extract materials for the construction of the last stage of Structure XX. Map by Julien Hiquet and Naachtun Archaeological Project.

Table 2 Increase in construction cost of Structure XX according to increase in distance of stone transportation, assuming 25,000 m3 of stone transported

Hiquet's study demonstrates that the spatial development of Maya cities obliged builders to seek material farther and farther away from construction sites, occasioning higher costs of transportation over time. It is possible that the stones used in the last construction stages of Group A of Naachtun were quarried in the sector north of Group B, where numerous quarries, sometimes very large, are still seen now (Figure 6). Later, during the Late Classic, the builders of Group B had to satisfy a high demand for veneer stones for vaulted palaces and pyramidal basements. This high demand coupled with centuries of extraction might explain the presence of an area approximately 300 m south of Group B, where a lidar survey revealed many quarries, clearly disproportionate to the scant associated residences (framed area in Figure 6). This area may have met the high stone demand for the construction of Groups A and B, after more proximate quarries were exhausted. This hypothesis remains to be tested.

Stone extraction from existing buildings is possible as well. At Naachtun, Early Classic structures XIII, XIX, XXII, XXIII and La Perdida of Group A (Figure 9), built between the third and fourth centuries a.d., were mined for stone. The date of their dismantling and the people responsible for it are more difficult to assess, but some insights may be drawn. Both La Perdida and Structure XXIII covered important funerary chambers, maybe of royal level (both looted). In those cases, the removal of stones may have been a symbolic gesture of dynastic rupture. This is congruent with the political shifts felt by Naachtun, located between Calakmul and Tikal and implicated in the oscillating sphere of influence between them (Nondédéo et al Reference Nondédéo, Sion, García-Gallo, Cases, Hiquet, Okoshi, Chase, Nondédéo and Charlotte Arnauld2021). The symbolic properties of stone (see Table 1) may be quite relevant here; however, those dismantlings also spared time and energy for stone extraction and to some extent transportation.

Investigations of (likely) non-specialized transport labor, and questions from publics interested in archaeological knowledge, challenge us to ask who the quarriers and transporters were, within the larger context of ancient Maya society, for stories like “Sous les jupes.” Many previous scholars have asked whether inhabitants of the urban core participated in public labor, or whether their supposed social status spared them from physical tasks (see Abrams Reference Abrams1994:96–108; McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016:30–50). To Hiquet (Reference Hiquet2020), the participation of hinterland populations is likely, but the mobilization of urban dwellers shouldn't be discarded, especially during the Early Classic period, when many Central Lowland hinterland communities were deserted in favor of urban cores (Adams and Valdez Reference Adams and Valdez2003:26; Ford Reference Ford1986:62–64; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019:139). At Naachtun, architectural and material data suggest that all social levels dwelt around the epicenter, with a population around 1,050 people circa a.d. 300 (Hiquet Reference Hiquet2024). Another clue for possible urban participants may be found in the funerary record of Naachtun. Most bodies, from all periods, even those placed in favored locations under houses, showed osteological evidence of stresses related to the frequent and repetitive carrying of heavy loads with a tumpline (Barrientos Reference Barrientos, Nondédéo, Hiquet, Michelet, Sion and Garrido2014, Reference Barrientos, Nondédéo, Michelet, Hiquet and Garrido2016, Reference Barrientos, Nondédéo, Michelet, Begel and Garrido2018; Goudiaby personal communication 2019). This evidence falls short of demonstrating that construction activities caused those stresses, but it indicates that even persons of a relatively high social status, living close to the royal court, were not exempted from physical tasks. In fact, Soustelle (Reference Soustelle1933:168–169) reports that middle-range elites among the 20th century Lacandon Maya (admittedly a social system distinct from the ancient Maya) participated in communal labor, and even derived their legitimacy from their superior participation. Given this, it is important to consider the status of 3-rain and 12-flint and thus what their participation in public construction meant to them.

Overall, stone extraction and transportation are highlighted in “Sous les jupes” to offer archaeological knowledge to European public audiences, particularly youths, knowledge that is relevant to the outreach programs of CNRS and is in a digestible and engaging format. The first content intention of this video is to tackle pseudo-archaeological claims about ancient monumentality, such as esoteric worldwide alignments, forgotten supernatural technologies, or alien intervention, by illustrating that almost every step of the construction process is known. The narrative demonstrates that blocks were neither too heavy nor manipulated with extravagant technologies unavailable to the Maya, despite the absence of beasts of burden and wheels. Hiquet's energetic study, focused on quarrying and transportation costs, offers clear data to prove that relatively small numbers of Maya people, over a relatively short period of time, could complete such tasks independently.

The video format of this project was offered to Hiquet through the established Past and Curious project and certainly served the archaeological data very well. Despite the story being offered in an animated style akin to idealized and romanticized fiction on TV, Hiquet wanted to avoid romanticizing archaeology for the sake of attracting and maintaining the public's interest or indulging personal fantasies about the job (Kaeser Reference Kaeser2008), instead highlighting accurate information about Guatemalan culture and history to build awareness in Europe. In sum, rightly or wrongly, Hiquet designed “Sous les jupes” to be purposely dense and technical, almost boring. The surprise appearance of the monkey at minute 0:57 (Figure 4) or the beauty of the sunset at 3:50 are, nevertheless, offered to compensate for this and keep the interest of young viewers. Furthermore, in previous experiences with public engagement in France, such as during European Archaeology Days, Hiquet recognized the importance of older generations, such as grandparents, in introducing children to the educational potentials of archaeological outreach. The generational relationship of 3-rain and 12-flint in “Sous les jupes” attempts to reflect the relationships within the primary viewership Hiquet expected. Upon reflection, Hiquet also recognizes that this generational approach likely impacts descendant community audiences as well.

When first developing “Sous les jupes,” Hiquet had no expectation that the process would build research potentials and offer insights for future investigation. Hiquet learned that the creativity of narration or illustration can allow for concealing problematic (or debated) aspects, such as the nature of prehispanic Mayan commoner names for example (see Kalyuta Reference Kalyuta2016; Mathews Reference Mathews1990). Further, he found that storytelling often requires more detail, not less. For example, the Past and Curious illustrators Hiquet worked with asked questions like: Did the stone transporters wear shoes or other protections? To address this very interesting question, Hiquet considered historic sources like the 16th Century Azcatitlan codex that depicts stone carriers (building the main temple of Tlatelolco) wearing nothing but a loincloth (Barlow Reference Barlow1949). Classic period mural paintings at Calakmul vividly represent a man carrying a heavy water jar with his feet only protected by thin sandals, and barefoot women (see Carrasco Vargas and Cordeiro Baqueiro 2012). Hiquet had to determine which source to follow: the more task-specific or the more contextually precise one? In other instances, Hiquet considered what degree of anachronism is acceptable in the background of the story. For example, 3-rain plays in front of a vaulted house at the beginning of “Sous les jupes,” which would have been a rare dwelling type during the 4th century c.e., but offered a sense of status to his family situation that Hiquet explored as part of his consideration of laborers’ origins. These questions offer new pathways for more specific research avenues regarding construction laborers and their personal experiences.

Reflecting upon the specific audience of European children and their older relatives, Hiquet finds that “Sous les jupes” could be improved by engaging with another type of dataset: the osteological data relevant to urban dwellers of Naachtun discussed above. Since schoolchildren often find skeletons so interesting, there is great potential to narrativize that carrying heavy stones, or other loads, with a tumpline could incur physical stresses like articulations and back pain evidenced in burial data. These correlations could lead to new directions in research, fueled by public interest, that cross-pollinate architectural energetics analytics with bioarchaeological data. In such ways, classic academic research and public outreach can feed each other mutually while demonstrating the similarity of modern viewers to past peoples.

Xunantunich and “Sak's Story”

Like Hiquet, McCurdy (Reference McCurdy2016, Reference McCurdy, McCurdy and Abrams2019) analyzed long-term monumental construction activity at the El Castillo acropolis of Xunantunich, Belize (Figure 10). Beyond prioritizing elites and political economy, p-d estimates can also be a starting point for considering laborers as agentive people in communities and collaborative work, thereby challenging labor-control arguments. This point of view was the inspiration for “Sak's Story,” a narrative about a young man around 14 years old, who, like 3-rain, takes on a new role in monumental construction.

Figure 10. Map of Xunantunich site core, showing the location of El Castillo. Map by Bernadette Cap and the Mopan Valley Preclassic Project.

The first version of “Sak's Story” appeared in McCurdy's (Reference McCurdy2016) dissertation in a section about exploring alternative research outcomes, an unexpected development from her community outreach experiences in western Belize (see McCurdy et al. Reference McCurdy, Friedel, Yaeger, Favreau and Patalano2017). McCurdy's experience as part of Fajina Archaeology Outreach in publishing To the Mountain! (see above) illuminated local and descendant community interest in storytelling that reflected accurate archaeological knowledge. That project did not target academics, other than seeking their help in spreading the word among communities farther afield in Belize. In McCurdy's dissertation, she briefly explored the value of storytelling as a research outcome, focused in that instance on other academics as the audience. Through word of mouth, a small collection of local community members and Maya descendants read “Sak's Story.” They helped McCurdy realize that the story was not visible enough to other stakeholders and did not communicate effectively to non-academics. After its original publication, McCurdy reconsidered the story and how it could best communicate the underrepresented aspects of ancient Maya construction (and our knowledge about it) to local and descendant communities. Excerpts of the revised version of “Sak's Story” are included below. It is important to note that McCurdy's story already reflects reconsideration and revision, while Hiquet's animated video remains in its original form.

“Sak's Story” is set at and around Xunantunich, a mid-level polity built on a hilltop of the Upper Belize River Valley (LeCount and Yaeger Reference LeCount, Yaeger, LeCount and Yaeger2010). Xunantunich rulers, like those of Naachtun, formed relationships with larger powers, including nearby Caracol (Belize), Naranjo (Guatemala), and, through them, Tikal (Guatemala) and Calakmul (Mexico) (Helmke and Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2013; LeCount and Yaeger Reference LeCount, Yaeger, LeCount and Yaeger2010). Xunantunich elites strove to demonstrate their political and social power through building campaigns, ritualized warfare, and carefully curated imagery. Building projects often focused on the El Castillo acropolis as the primary ritual and royal complex (Leventhal Reference Leventhal, LeCount and Yaeger2010; McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016:337–384). El Castillo's architectural history can be segmented over nine phases, which McCurdy virtually reconstructed to begin energetic analyses (McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016:365–407, 2019:Figure 10.3; see Figure 12). Figure 11 compares the “labor investment” over time at El Castillo. This diachronic picture of labor can be used to center Xunantunich rulers and what they were able to accomplish through their labor control of local populations.

Figure 11. Comparative totals of person-day estimates for nine construction phases of El Castillo, Xunantunich, Belize.

What about those local populations from which laborers were drawn? In “Sak's Story,” Sak lives in a farming community near Xunantunich, many of which have been explored archaeologically (e.g. Robin Reference Robin2012, Reference Robin2013 at Chan; Yaeger Reference Yaeger, Canuto and Yaeger2000 at San Lorenzo). “Sak's Story” describes the journey Sak would have taken from Chan to Xunantunich, focused on his view of the witz (‘sacred mountain’ [Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Schele and Parker1993; Stuart Reference Stuart1997]):

Sak's trek from his family's farm to the witz was long and started early. Eventually, the sun greeted him as he navigated farming terraces, warming his face when he reached the river. The canoe found the opposite shore easily. The uphill climb to his quarry position was not so easy, even with the paved sacbe beneath his feet. Happily, he found a companion for his climb, a friend from a nearby farm also assigned to the quarry.

Within the energetic analysis of El Castillo, Sak is one hypothetical datapoint among many in typical p-d estimates. Additional analytical procedures can target smaller scales and potentially illuminate the contributions of individual laborers. To attempt this, McCurdy projected multiple scenarios for seasonal construction scheduling for all nine phases, accounting for agricultural activities and seasonal rains (see Murakami Reference Murakami2015). For example, take El Castillo's Late Classic Mid Samal (a.k.a. Period 2b, ca. a.d. 625–650) when the acropolis started resembling the shape we recognize today (Figure 12). One labor-scheduling projection indicates that construction could have been completed over 10 seasons, with early seasons focused on the major substructural terraces and the final four seasons focused on the summit temple, known as Structure A-6-3rd.

Figure 12. Virtual reconstruction of Late Classic Samal Period 2b of El Castillo at Xunantunich, Belize, with Structure A-6-3rd at the summit. By Leah McCurdy.

Continuing with the most reasonable scheduling scenarios, McCurdy applied fine-grained labor analysis for separate tasks during each season. For example, the construction of the temple superstructure in season 10 would have required 26 separate processes, visualized in Figure 13. The sequence of tasks is crucial to this analysis, to consider how labor would have been organized. Limestone needs to be quarried before it can be cut into regular stone and coursed into walls. Sascab needs to be collected and limestone needs to be burned into lime before mortars and renders can be mixed. Cobbles also need to be collected before wall core materials can be inserted as masons build walls. All materials from the quarry and forest sites need to be transported to the building site itself and/or to nearby preparation areas, such as the location where ornamental carving would take place. Once all stone was extracted and transported, labor requirements slowly reduced.

Figure 13. Excerpt of a chart detailing the task-scheduled building sequence and labor estimates per day for Season 10 of Late Classic Mid Samal (Period 2b) of El Castillo. Full chart of 5 winals (20-day periods) offered in supplementary materials. Refer to McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016 for discussion about different supervision projection options in the full chart.

At most, 234 laborers would have been needed on site to accomplish the tasks required early in season 10 (Figure 13). This compartmentalized analysis indicates that the largest labor crews would concentrate on stone extraction and transport. For example, the labor crew extracting limestone likely comprised 50–60 people at most while only three people would have extracted sascab. This is where Sak fits into these projections. Sak's journey to the witz and work at the quarry would occur at the beginning of the construction sequence.

It is important to note that McCurdy's maximum on-site labor estimate seems low when compared to Hiquet's estimates above. Our estimates are working at different levels of analysis and at different time scales. Hiquet projects estimates across the entire construction timeline, combining labor for all building seasons and across each season. With detailed architectural data, McCurdy (Reference McCurdy2016) found that projecting building project length and projecting labor within each season, as well as task scheduling, resulted in significantly reduced labor estimates. The implications of this reduction for “labor-control” arguments are discussed in McCurdy's dissertation (2016).

The activities described above took place at the quarry just east of El Castillo. “Sak's Story” explores a scene of the early days at this quarry, incorporating direct results of energetic analysis:

The quarry was nestled in the witz, a huge bowl of bedrock. As Sak surveyed the scene, he recognized some faces but saw many strangers, too. By his count, there were over 50 people working there plus all the transporters taking material to the construction site just up the hill. As he watched them work for a moment, he realized they weren't working individually but in teams. Sak and his friend spotted a young man at the edge of the quarry speaking with a seated older man who seemed quite important.

Labor analysis can be extended to supervision and collaboration (Abrams and Bolland Reference Abrams and Bolland1999; DeLaine Reference DeLaine1997; Smailes Reference Smailes2011). The number of supervisors required to effectively manage a large workforce can be estimated in several ways (see McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016:511–527) such as G. A. Johnson's (Reference Johnson, Renfrew, Rowlands and Segraves1982) model of “scalar stress” whereby the maximum effective workgroup contains eight people, including an embedded supervisor. Supervision projections usually produce modest sizes of supervisory labor, enough to realistically project oversight of workgroups located in distant sites and communication across areas. Informed by scalar stress, McCurdy employed a model of embedded supervisors, mobile managers of multiple workgroups, and a few masters overseeing large scopes of work (see Figure 13). As an example, the early components of construction for Structure A-6-3rd's temple are simulated in a labor distribution and supervision diagram (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Labor distribution and relationships projected for Day 2 of Season 10 of Late Classic Mid Samal Period 2b at El Castillo. This projection follows the hypothesis that lime burning would occur at the quarry site and powdered lime would be transported to the building site for production of mortar and plaster. Alternatively, lime burning may have occurred at building sites using wood from recently cleared forest.

Each node in Figure 14 is a laborer projected within a context of workgroups and the supervisory hierarchy. For example, Sak is one of the two laborer nodes connected to a supervisor, making up the small team of sascab collectors. In “Sak's Story,” Sak and his friend meet their supervisor and manager.

They learned this important man was the quarry manager, in charge of all work crews, and he was just about to assign a crew to sascab extraction. Sak and his friend informed him that they both had experience collecting sascab from a fine source near their farms. The manager asked if they knew the special prayers of gratitude to the gods of the earth. They nodded and he seemed pleased. He instructed them to follow their new supervisor to a prime area for sascab extraction. Their new supervisor appeared to be quite friendly with the other workers, joking with stonemasons and lime burners as they traversed the quarry. The boys learned that this was his third building season.

Figure 14 abstractly diagrams major locations including the quarry itself, forest extraction sites, on-site preparation areas, and transportation routes between them. McCurdy projects that each location would need a manager in charge of communication across workgroups (who may be spread out) and other work areas. Figure 14 attempts to visualize which contemporaneous workgroups would be most distant and/or proximate. This projection helps us consider how lively, perhaps even crowded, a single quarry would have been. “Sak's Story” considers these possibilities:

Their team worked in an elevated spot most of the day, with a view of the stone cutting teams creating grids across the quarry. Sak had never experienced such entertaining work. All day long, the stone cutters would harmonize into songs about the ancient witz mountain and the new witz temple they all built together. As the smoke curls rose from the lime heaps, Sak could make out the chants and prayers seeking success for each burn. Sak and his friend joined their supervisor for lunch in the stone cutting area. Sak heard more jokes on that first day than he had heard in his whole life! After lunch, they chatted with the two women transporting the sascab from the quarry to the building site, after learning that they were distant cousins of Sak's friend.

Each of these workgroups, and the interactions among them, can be a site of analysis. It is easy to conceptualize workgroups as homogenous: strong, silent young men hauling stones for hours. However, given population constraints, necessary scheduling of agricultural labor, and the longevity of such projects, this cannot have been the case. The heterogeneity within workgroups likely would have included differences in age, skill level, motivation, and even gender. Like in “Sous les jupes,” women feature in “Sak's Story” as transporters. Women, and children younger than 3-rain and Sak, may have participated in other activities as well.

McCurdy considers workgroups as social networks. Applying social network analysis, we can consider the number of potential relationships present within and among workgroups. Do workers share familial connections? Were they all strangers on day one, eventually building new relationships? How do power disparities in worker–supervisor or supervisor–manager relationships relate to broader social dynamics? Social network analysis also offers means to consider the “flows” or exchanges (Ofem et al. Reference Ofem, Floyd, Borgatti, Caulkins and Jordan2013) that occur among collaborators. These flows may be material (such as sharing tools or lunch) but may also be intellectual (sharing skills or ritual knowledge). For example, supervisors would provide instructions to workers and progress reports to managers. If archaeological excavation crews today are any indication, flows could also include jokes, gossip, existential arguments, or ghost stories. These intangible and phenomenological aspects of the work add value, especially as we attempt to engage members of the public about history. Such aspects were relatively sparse in the original version of “Sak's Story.” Local and descendant readers, including those with experience working on archaeological excavation crews, helped McCurdy realize the value of exploring these facets in more detail, to benefit the storytelling and potential insights into ancient labor dynamics.

Another dimension of value derives from ideology and social perception. What would engaging in resource extraction and building mean to these laborers? As noted above, the symbolic properties of stone (see Table 1) may have played a significant role in the personal value attributed to construction. “Sak's Story” considers how sascab may have been valued specifically:

Unexpectedly, they found a pocket of special orange sascab. A good omen! They were delighted. Their supervisor stopped immediately to offer thanks. The manager provided the newest baskets for collecting this special sascab and told the boys that the shamans will use this sascab in their rituals to sanctify the new witz.

We can also ask how a local community member would view their place in the construction project. What value would the whole construction project hold in their view of the community and of themselves? To consider these questions, “Sak's Story” includes several references to the ritual or spiritual components of the building process. Anthropological analogy suggests that permissive rites would have been undertaken to ensure beneficence from divine forces that oversee the forests and stone outcrops (see; Hansen Reference Hansen2000: 119; Schreiner Reference Schreiner, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2003; Thompson Reference Thompson1963:139). Archaeologists have considered whether these ideological dimensions impacted work at quarries (Clarke and Gill, this issue, after Houston Reference Houston2014). While these are some of the most difficult pieces of the building puzzle to reconstruct archaeologically, we should not ignore their value to ancient Maya laborers like Sak and to descendant communities. The very notion of sacredness of the witz probably motivated careful attention and reverence.

As the day wound down and the manager stopped work, Sak wondered what camp would be like. If all the stories and laughter today were any indication, he was looking forward to it! As they made their way down the hill to the campsite, they encountered the transporter women again, making their way to their own secluded campsite. The older of the two women joked that the men's campsite can get a bit rowdy and she didn't want to hear that Sak and her cousin got up to any trouble at camp this evening. Before they parted, the woman lowered her voice and reminded Sak of why he was there: “The witz is sacred. Our work here is sacred.”

These may have been some of the most compelling reasons to labor. Political associations with divine leaders were another dimension of the complex puzzle of laborer motivations. Relationships with other laborers and the dynamics of group collaboration probably also motivated many people to contribute to building. How much force or control was exerted on these people by sociopolitical elites can be debated (see discussion in McCurdy Reference McCurdy2016). Most scholars who apply energetics to Maya architecture tend towards high degrees of control. Sak's story offers an alternative perspective, that could have been true simultaneously, about a person with personal and spiritual reasons to participate (see also Becquelin et al. Reference Becquelin, Breton and Gervais2001:207). Narratives about hypothetical people like Sak and 3-rain allow us to imagine these phenomenological and psychological elements of the past for the benefit of the public and scholarship. The version of “Sak's Story” offered here is so much better than the original for the elevation of these aspects, encouraged through collaboration with members of the local and descendant communities. Like Hiquet, McCurdy found that research and public engagement are beneficially entangled, especially when storytelling is a prominent component of archaeological outcomes.

Conclusions

This paper sits at the intersection of several modes of inquiry and archaeological topics. As part of this special edition of Ancient Mesoamerica, we have offered insights from our research on ancient Maya quarries and the place of quarrying within construction processes using the methodology of architectural energetics. Our results are relevant within the spectrum of research on ancient Maya architecture, political economy, and social life. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, we have found that our results and their implications are relevant to the public, especially in redressing overly inflated projections of ancient Maya labor, challenging misinformation about Maya culture, and considering the value of historical information to distinct audiences.

We seriously ask ourselves: will people outside academia read this paper and the others in this issue? We may reach a hundred archaeologists (if we are lucky; see Hamilton Reference Hamilton1990 for insights on this topic). “Sous les jupes” and “Sak's Story” can reach so many more. In fact, “Sous les jupes” already has; it has over 5,090 views as of March 2025. This difference in reach helps us reflect upon who knows what and how much about ancient Maya quarries. Why might ancient quarries be interesting to people outside academia? How can we make this information accessible to them? We reflect upon the ways in which we share our work. We have found that offering narrativized encapsulations of our energetics analysis of Maya monuments can inform multiple publics about archaeologically accurate evidence tying awe-inspiring history to real life.

We have foregrounded labor and laborers both because these facets of Maya history have been understudied in the past and because these are the subject of the many questions we receive from the public about our work. Our varied experiences in archaeological public engagement have taught us that members of the public often ask different, or differently nuanced, questions than we do. Those questions are important, should be investigated, and we should report our findings in ways that are meaningful to public audiences.

We accept that “Sous les jupes” and “Sak's Story” (and the research that informs them) are not perfect. Our reflections upon our experiences as archaeological storytellers include many ways we can do better. We both plan to prioritize the narrative outcome (and the audiences of this outcome) over the academic one. Specifically, this means that both of us will more carefully consider narrative formats in the future, as they relate to our specific intended audiences and the value of certain media among distinct age groups.

This prioritization has already had implications in our respective careers, given the structures and expectations of our discipline mentioned above. We learned that storytelling takes time and different ways of thinking/writing than our archaeological training taught us (though they are more related than we realized, as Mickel [Reference Mickel2011] and van Helden and Witcher [Reference van Helden, Witcher, edited by van Helden and Witcher2019] suggest). We learned to embrace our imaginations while allowing the scholarly part of our brains to critically assess where our imaginations took us. We don't see this as a weakness of our scholarship. We see it as a strength.

Reflective questions centered on stories, public outreach, and our responsibilities cannot be ignored, even if public outreach continues to be devalued in university tenure and the profession of archaeology. Archaeologists, whether they like to think of it or not, are public-facing scholars. Knowledge about history and culture, even if narrowly focused on quarries of the Lowland Maya region, is public knowledge.

Acknowledgments

The Naachtun Archaeological Project (2010–2022) is funded by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, the CNRS, the Foundation Pacunam, the Perenco Company, and the Fondation Simone et Cino del Duca. It forms part of UMR8096 ArchAm and CEMCA activities, undertaken with the permission of the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala. McCurdy's study was undertaken as part of the Mopan Valley Preclassic Project, under Dr. M. Kathryn Brown, and with the permission of the Belize National Institute of Culture and History. We thank all project members, especially the Guatemalan and Belizean men and women for their contributions. We also thank the issue editors and anonymous reviewers for their careful comments and insights. Lastly, we are grateful to the issue editors for their resilence.