1. Introduction

Throughout his 2024 campaign, President Donald Trump repeatedly raised concerns about increased gender-based violence by Latino immigrants. During the first presidential debate, he claimed that “these killers are coming into our country and they are raping and killing women” (Reference Trump and Biden2024). Years earlier, after the 2016 terrorist attack on an LGBT+ nightclub in Orlando, Florida, Trump employed a similar rhetoric, this time targeting Muslims: “Many principles of Radical Islam are incompatible with Western values and institutions. Radical Islam is anti-women, anti-gay and anti-American” (Reference Trump2016). In this rhetoric liberal values, including gender equality, LGBT+ rights, and individual freedoms, are selectively employed to promote and legitimize exclusionary or illiberal agendas (Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2011; Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017). Thereby, political actors who typically drive gender backlash and anti-feminist agendas appeal to progressive arguments to justify xenophobic ideas, ostensibly to defend liberal (Western) achievements.

Research on this rhetoric has largely focused on how it is used by politicians. Work on femonationalism, that is, the invocation of gender equality and women’s rights to promote anti-immigrant stances (Farris, Reference Farris2017), shows that such rhetoric has become increasingly prevalent over time (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks, Reference Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks2025).Footnote 1 Though initially associated with far-right and anti-gender actors, recent evidence suggests that it is increasingly employed across the political board, presumably to accommodate the rise of right-wing support among citizens (Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks, Reference Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks2025). The existing literature attributes a range of motives to femonationalist speech, ranging from the mobilization of new voters (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Jennings and Ralph-Morrow, Reference Jennings and Ralph-Morrow2020; Doerr, Reference Doerr2021), the deepening of xenophobic sentiments (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Morgan, Reference Morgan2017; Jennings and Ralph-Morrow, Reference Jennings and Ralph-Morrow2020), the justification of social exclusion (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2011; Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Donà, Reference Donà2020), the polishing of radical parties’ image (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017) to the deliberate undermining of progressive, feminist pursuits (Sager and Mulinari, Reference Sager and Mulinari2018).

While existing scholarship anticipates selective liberal rhetoric to meaningfully shape public opinion, empirical evidence on its effects remains scarce. One exception is the study by Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega (Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega2024), who find that increased LGBT+ support among right-wing nativists (Lancaster, Reference Lancaster2020; Spierings, Reference Spierings2021) is often a strategic response to selective liberalism rather than a genuine shift in social attitudes. This “inclusion for the purpose of exclusion” (Hunklinger and Ajanović, Reference Hunklinger and Ajanović2022) highlights the contingent and reactive nature of some progressive achievements. Yet, it remains unclear whether selective liberalism undermines liberal values more broadly. As increasing numbers of voters, including women and young people, gravitate toward illiberal actors (Setzler and Yanus, Reference Setzler and Yanus2018; Petty, Magilligan and Bailey, Reference Petty, Magilligan and Bailey2022), it is crucial to examine whether liberal support is context-dependent and shaped by framing (cf. Graham and Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay, Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022). Given the reach of selective liberal rhetoric across ideological divides, a comprehensive analysis of its effects on citizens with different belief systems is warranted.

This paper is the first to study the effects of femonationalism, as a concrete instance of selective liberal speech, on both nativist and liberal voters’ attitudes,Footnote 2 complementing our knowledge of how effective selective liberalism is as a political tool. The empirical examination is grounded in a new bi-directional theoretical argument on the link between femonationalism and citizens’ policy preferences. It explains how femonationalism conditions (il)liberal preference adaptations depending on citizens’ prior belief systems. Drawing on social psychological theories of social identity (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Moscovici1972; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1986/2004) and cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962; Draycott and Dabbs, Reference Draycott and Dabbs1998), I predict that exposure to this rhetoric induces cognitive dissonance, prompting individuals to update their preferences. However, the exact resolution of this dissonance depends on their relationship to the groups involved. Specifically, prior immigration attitudes function as a regulator of the causal mechanism: Nativist individuals resolve dissonance through outgroup disidentification, leading them to embrace more progressive gender policies (selective liberal preference adaptation). Conversely, pluralist individuals seek to adapt immigrants to the national ingroup by endorsing stricter integration and assimilation policies (selective illiberal preference adaptation).

To test this new theoretical argument, I conducted an original, preregistered survey experiment with 3,118 U.S. citizens.Footnote 3 Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups or to a control group. The treatment conditions exposed respondents to a femonationalist message delivered by elite politicians, systematically varying both the party affiliation of the politician (Republican or Democratic) and the specific threat framing of the message. The threat frame had two conditions: a value threat frame, which depicted immigrants as a threat to gender equality, and a safety threat frame, which presented them as a threat to women’s security. Subsequently, respondents reported their preferences on strict integration policies and on gender policies. General immigration attitudes, the conditional variable, were measured before treatment.

The results provide causal evidence for the two preregistered hypotheses. As predicted, when exposed to a femonationalist message from a Republican politician, anti-immigration respondents increased their support for public education on gender issues, including mandatory instruction on gender equality and sexual consent. Pro-immigration respondents became significantly more supportive of strict integration requirements, such as mandatory integration courses and conditional naturalization, compared to their counterparts in the control group, who generally opposed such measures. Beyond initial expectations, the effect on liberal individuals was not limited to messages by Democratic politicians; femonationalism by a Republican politician produced similarly strong shifts in integration preferences. In line with my preregistered expectations, the political tool of femonationalism proves to be effective in influencing both nativists and liberals.

This study is the first to assess the impact of femonationalist speech on policy preferences and to consider different ideological positions in that relationship. The strength and consistency of the findings demonstrate that femonationalism tangibly shapes policy views and that these effects are not uniform across the citizenry. Thus, the paper makes both a theoretical contribution by explaining these differential effects and an empirical contribution by documenting them for the first time. Crucially, the results reveal that liberal support is contingent and operates through a trade-off logic: citizens balance gender equality concerns against integration policy preferences, a dynamic overlooked when these domains are studied in isolation. This insight advances public opinion research on preference formation and contributes to the literature on political communication, gender and politics, and immigration attitudes by demonstrating how femonationalism effectively bridges these policy domains. Ultimately, these preference shifts suggest that femonationalism contributes to a broader, cumulative process of reshaping public opinion—one in which liberal values are strategically appropriated and gradually redefined over time.

2. Femonationalism and policy preferences

Femonationalism, as coined by Sara Farris Farris (Reference Farris2017), describes the invocation of gender equality and women’s rights to advance anti-immigrant agendas. It represents a specific manifestation of selective liberal rhetoric which describes the broader logic of employing liberal values, including LGBT+ rights and individual freedoms, to justify exclusionary politics (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017). Femonationalist rhetoric is often considered strategic, as it is commonly championed by political actors whose policy records show little commitment, if not opposition, to gender equality (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017). Regardless of the underlying convictions of those who use it, be it genuine or pretextual (Sniderman and Hagendoorn, Reference Sniderman and Hagendoorn2007), it can be understood as a strategy that serves a communicative function in justifying or advancing exclusionism.

Previous research on femonationalism offers important insights into the supply side of the phenomenon, focusing on its defining themes (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Doerr, Reference Doerr2021), the actors who employ it (Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks, Reference Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks2025), and the conditions of its use (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Morgan, Reference Morgan2017). These studies show how women’s and feminist issues have become integral to the migration debates in many (Western) liberal democracies (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2011). While femonationalist themes have historical precedents—such as the sexualization of Black men as threats to white women in Jim Crow America (Farris, Reference Farris2017)—their contemporary deployment has intensified with the growing salience of migration in electoral campaigns (Dennison, Reference Dennison2020; Kustov, Reference Kustov2023). Political actors increasingly employ progressive achievements to justify the exclusion of immigrants deemed incompatible with liberal-democratic values (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Triadafilopoulos, Reference Triadafilopoulos2011; De Lange and Mügge, Reference Lange, Sarah and Mügge2015; Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Farris, Reference Farris2017; Campbell and Erzeel, Reference Campbell and Erzeel2018; Donà, Reference Donà2020). Contemporary femonationalism has mainly been attributed to far-right populist actors, though its prevalence has also been demonstrated among exclusionary feminist organizations (Farris, Reference Farris2017), and increasingly among actors from the political center (Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks, Reference Fernandes, Meguid and Weeks2025). Notably, its rhetorical appeal persists amid increasing backlash on gender issues.

At its core, femonationalist rhetoric, much like the broader migration debate, involves the explicit or implicit description of a threat (Wodak, Reference Wodak2015; Morgan, Reference Morgan2017). The source of this threat is the immigrant Other, an (Ethnic) outgroup that is stereotypically associated with “the patriarchal traditions of ‘immigrant culture”’ (Siim and Skjeie, Reference Siim and Skjeie2008, p.324), such as Muslim or Latino culture. The target of the threat can be twofold. Some femonationalist statements describe a threat to liberal values such as women’s rights and gender equality (here referred to as value-threats). Value threat frames emphasize the cultural otherness of migrants and their presumed backwardness regarding gender roles (Farris, Reference Farris2017; Morgan, Reference Morgan2017). A second common theme in the literature is threat descriptions toward the safety and bodily integrity of women and girls (here called safety-threats).Footnote 4 These statements draw on longstanding notions of migrant women as victims of sexism, gender-based violence, and patriarchal practices (Sager and Mulinari, Reference Sager and Mulinari2018; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Milani, Brömssen and Spehar2024). Safety threat frames, thus, call for the protection of, above all native, women from (non-Western) immigrant men. In summary, central elements of femonationalist rhetoric are the emphasis of Otherness of the immigrant outsider (Doerr, Reference Doerr2021), the incompatibility between immigrant culture and receiving societies (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017), and with that, the distinction between “a single ‘good us’ as opposed to many ‘others”’ (Donà, Reference Donà2020, p.290).

A condition for the use of femonationalist rhetoric is that liberal values, such as progressive gender views, are widely regarded as socially desirable within a given society (Akkerman and Hagelund, Reference Akkerman and Hagelund2007; Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017; Morgan, Reference Morgan2017). Many liberal democracies are “celebrated for their pluralism, liberal social values and progressiveness” (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017, p.117) and liberalism has become a central part of the national self-understanding. In the same way that some autocracies adopt pro-women agendas and language to signal proximity to the West (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022), liberal democracies understand these values as defining characteristics of their societies, especially in distinction to other (often non-Western) nations. As such, liberal values seem to have become nationalized in these contexts, meaning that they are an integral part of the national identity and generally considered to be desirable (Læ gaard, Reference Lægaard2007). It is this nationalization (ibid) of liberal values that allows illiberal and anti-women actors to employ gender equality and women’s rights as a legitimization for xenophobic claims. Thereby, femonationalism becomes a tool for demarcation that attributes liberal values to the national ingroup, while regressive values are associated with the immigrant outgroup (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017).

While the body of literature on the supply side of selective liberalism is growing, its effects on public opinion remain understudied. To date, two studies have investigated its impact causally. Evidence by Lawall (Reference Lawall2023) suggests that femonationalism can indeed reduce the stigma of far-right ideas. The study supports observational evidence that understands femonationalism primarily as a tool to de-stigmatize far-right parties and ideas (Jennings and Ralph-Morrow, Reference Jennings and Ralph-Morrow2020). The second study by Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega (Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega2024) is more concerned with the attitudinal impacts of selective liberal rhetoric. By showing that homonationalism heightens LGBT+ support among individuals with nativist immigration predispositions, they highlight how citizens mirror the selective liberalism of the message in their preferences. When immigration and LGBT+ tolerance are pitted against another, these individuals respond by liberalizing their views on sexual minority groups. This work provides important insights into the responsiveness and conditionality of liberal support among social conservatives, yet it leaves out a majority of citizens who harbor social liberal attitudes. Related work on liberal trade-offs shows that when pressed to choose, liberal citizens, too, respond selectively by compromising those values that benefit others over themselves (Ivarsflaten and Sniderman, Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022). Femonationalist rhetoric does not enforce such a choice, but raises the question whether liberal citizens respond similarly when confronted with inconsistencies between liberal views.

The present study advances this literature in several key ways. While existing work focuses on general attitudinal shifts, as the perceived acceptability of anti-immigrant sentiment (Lawall, Reference Lawall2023), this study examines how femonationalism impacts specific policy preferences. It further provides the first test of how femonationalism affects citizens across the ideological spectrum, demonstrating that pro-immigration citizens respond with illiberal preference shifts that mirror the selective liberalism observed among nativists (Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega, Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and López Ortega2024). Importantly, it extends existing theory and empirical evidence by including other immigrant outgroups beyond Muslims, introducing and testing the conceptual distinction between the two threat dimensions common in femonationalist rhetoric (safety threats versus value threats), and by systematically varying speaker partisanship, recognizing that such messages are embedded in partisan political contexts.

3. A bi-directional theory of femonationalism

To understand the impact of induced value conflicts in the form of femonationalism on citizens’ policy preferences, I propose a novel theoretical argument of selective preference adaptations that is conditional on prior immigration attitudes. The argument suggests that citizens who are opinionated about immigration experience cognitive dissonance when exposed to femonationalist rhetoric, and will consequently amend their preferences on the invoked issues. However, how they resolve the dissonance and which exact preferences are updated depends on their relationship with the involved groups, meaning that prior immigration attitudes act as a regulator for the causal mechanism. While nativists engage in a process of disidentification from the immigrant outgroup and, hence, embrace more progressive gender policies (selective liberal preference adaptation), pluralists strive to adapt immigrants to the national ingroup by adopting stricter demands to integrate and assimilate (selective illiberal preference adaptation). The argument lays out a dynamic causal chain, in that immigration attitudes (understood as a stable attitude following Kustov, Laaker and Reller, Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021) serve as a thermostat. The theory builds on classic work in political psychology, namely, cognitive dissonance theory (CDT; Festinger, Reference Festinger1957, Reference Festinger1962), later integrations of the self-concept into CDT (Aronson, Reference Aronson1968; Harmon-Jones and Mills, Reference Harmon-Jones, Mills and Harmon-Jones2019) and social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Moscovici1972, Reference Tajfel1974, Reference Tajfel2010).

The argument departs from existing literature on sociocultural attitudes that commonly categorizes citizens along two dimensions. Supporters of immigration, open societies, and diversity typically also oppose assimilationist integration policies and favor progressive, environmental, pro-gender, and LGBT+ inclusive policies (this value profile is often summarized under the GAL acronym: Green, Alternative, Libertarian). In contrast, those less tolerant of diversity also tend to favor traditional family structures and oppose progressive gender and sexuality policies (often called TAN: Traditional, Authoritarian, Nationalist). Most people’s values fit into one of these two profiles; their views are sorted along the GAL-TAN continuum (Kitschelt and McGann, Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson, Reference Liesbet, Marks and Wilson2002; Hetherington and Weiler, Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Burns and Gallagher, Reference Burns and Gallagher2010; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2010; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015; Mason, Reference Mason2016; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

When exposed to femonationalism, individuals on both sides of the GAL-TAN continuum are likely to experience cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological disturbance that a person feels when she realizes that two or more of her beliefs, views, or values are inconsistent or conflicting (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957, Reference Festinger1962). Femonationalism introduces such inconsistencies as it disrupts the typical sociocultural value distinction by imposing a conflict between progressive gender and inclusive immigration stances, and raising ambiguities about associated principles such as freedom and autonomy. For those with liberal-pluralistic views, the juxtaposition of immigration and gender achievements induces the incompatibility between cherished values, implying an ideological dilemma. Conversely, for individuals with traditional-nationalistic views, the message presents an outgroup opposition to values that they too oppose or at least disengage from. When opposition to progressive gender values becomes an outgroup marker, nativists either risk association with that group (if they too uphold anti-gender views), or the denial of the ingroup’s distinctiveness (if they remain disengaged from those). Consequently, exposure to femonationalism is likely to introduce a dissonant relationship between prior held beliefs on gender issues and immigration to citizens with different value profiles.

In a state of cognitive dissonance, individuals are incentivized to update their beliefs, that is, to adapt their preferences on the conflicting values (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957, Reference Festinger1962). As individuals constantly strive for consistency in their thoughts and beliefs (ibid), cognitive dissonance manifests as a form of mental discomfort that involves negative feelings such as unease, pressure, or even anxiety. Individuals are, therefore, motivated to leave this state as fast as possible and to resolve the contradiction. Cognitive dissonance theory suggests three approaches to resolve the distress (dissonance reduction): denial, justification, and adaptation (ibid). In response to femonationalism, denial may be feasible to those individuals who are relatively disengaged from gender and immigration issues. The stronger the priors on these themes, however, the more difficult it will be to ignore the internal conflict they induce. Justification is a likely response for those individuals who find a ground to avoid the induced value clash. This could, for example, be the case if the credibility of the source is questioned, that is, when the message comes from an unreliable person or a political adversary. The induced value clash can then be explained and disregarded due to the intentions of the speaker. If no such ground exists, the most likely rational response to femonationalism is the adaptation of the engaged views and preferences. Thereby, intrinsic cognitions or beliefs are updated in order to match other existing convictions, and to be in balance with the individual’s self-perception.

Which preferences are updated, I argue, depends on the relationship to the social group(s) that are engaged in the induced value conflict, and as such, on prior immigration attitudes. As femonationalism associates liberal values with the national ingroup and regressive ones to the immigrant outgroup, the personal relationship to this outgroup is formative in the process of dissonance resolution. It is at this stage that the theoretical argument receives its dynamic element as I suggest that the level of positive or negative sentiment to immigrants informs which preferences are likely to be adjusted and the strength of that response, similar to a (causal) regulator.

People with nationalistic values are likely to resolve the induced tension by adopting more positive gender views as they strive for demarcation from the immigrant outgroup. Underlying this are two processes, namely the negative motivation to disidentify with the immigrant group, and the positive motivation to embrace positive features unique to their own ingroup. Disidentification describes the strive to actively distance oneself, that is to maintain cognitive separation, from disliked groups (Elsbach and Bhattacharya, Reference Elsbach and Bhattacharya2001; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel2010). That entails defining oneself as not sharing the same characteristics and values associated with that outgroup. When opposition to certain values or ideas becomes a marker of the disliked outgroup, individuals risk association with that group if they too uphold similar views. To avoid association, people with a negative relationship to that outgroup will engage in disidentification strategies to retain distance between themselves and that group. For nativists, this means a negative motivation to distance themselves from regressive gender views, even—or especially—if they formerly embraced those.

Further insights from social identity theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1974; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1986/2004) support the expectation that disidentification plays a role in shaping nativists’ policy preferences in favor of gender issues. Social identity theory posits that individuals are motivated to retain a positive self-image and engage in activities to boost the own group’s positive distinctiveness. Femonationalist rhetoric presents liberal gender values as a widely acknowledged and socially recognized achievement of the national ingroup threatened by the disliked immigrant outgroup. This creates incentives to embrace values presented as positive and socially accredited sources of national pride (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2017). Embracing gender values allows nativist individuals to maintain a positive self-image in line with nationalist sentiments—“we are better than them, and our values are inherently good”—while marking a distinction from the disliked outgroup. The alternative would be misaligned with both central SIT principles. Choosing immigration over gender values would require denying the positive ingroup feature highlighted in the message and accepting similarity to immigrants. Consequently, when traditional-nationalistic individuals encounter femonationalism from credible sources (actors they deem trustworthy and hence are receptive to the selective value configuration of the message), they are likely to increase support for liberal gender policies to disidentify from immigrants and restore cognitive alignment.

H1 (disidentification thesis): Exposure to femonationalist speech by a politician from a party that represents a conservative immigration stance makes individuals with anti-immigration attitudes more supportive of gender equality policies.

Conversely, individuals with liberal-pluralistic values resolve the induced tension by updating their demands for immigrants to assimilate into the country’s liberal culture. Central to this argument is the notion that pluralistic individuals will reduce dissonance by adjusting preferences that do not threaten their self-concept. In a later modification to cognitive dissonance theory, Aronson ( Reference Aronson1968); Harmon-Jones and Mills ( Reference Harmon-Jones, Mills and Harmon-Jones2019) introduces the self-concept to dissonance processes, suggesting that individuals generally strive to maintain a consistent and positive sense of the self. As a result, dissonance reduction involves not only aligning conflicting beliefs but also preserving a person’s self-perception and integrity in that process (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962; Beauvois and Joule, Reference Beauvois and Joule1996).

Aronson’s self-concept helps to understand preference adaptations in response to femonationalism among liberal-pluralistic individuals. Generally, liberal individuals could follow two possible pathways to dissonance reduction: compromising their gender egalitarian attitudes or their immigration inclusiveness. However, several considerations suggest that compromising on progressive gender values is the less likely response. Femonationalist rhetoric inherently frames gender equality as a defining feature of the national or liberal community—a core ingroup marker under perceived threat from an outgroup. While liberal-pluralistic individuals typically score low on nationalism, understood as beliefs in national superiority and dominance (Kosterman and Feshbach, Reference Kosterman and Feshbach1989; Schatz, Staub and Lavine, Reference Schatz, Staub and Lavine1999; Huddy and Khatib, Reference Huddy and Khatib2007), femonationalist messages nevertheless assign ingroup membership to a progressive societal community, tapping into forms of group belonging rooted in broader cultural or societal identification such as civic pride (ibid). Gender equality is, thereby, positioned as a shared achievement that defines a progressive “us.” Following the principle of the positive self-image (Aronson, Reference Aronson1968), preserving these positively valued ingroup characteristics becomes paramount to maintaining a benevolent self-concept. Considering the contrary, namely to compromise on gender values, would mean abandoning those very achievements that the message emphasizes as constitutive of the ingroup’s positive identity. This preservation mechanism is further consistent with the principle of ingroup-favorism, as it prioritizes the protection of ingroup members’ (women’s) interests over accommodating outgroup members (Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner and Worchel1979). These predictions find support in related empirical research. Ivarsflaten and Sniderman (Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022) demonstrate that when forced to choose between competing liberal values, liberal citizens are willing to restrict outgroup rights (religious freedom) to protect ingroup (gender) values. Similarly, exposure to femonationalist rhetoric has been shown to increase willingness to accept negative sentiment toward immigrants (Lawall, Reference Lawall2023), suggesting a lack of firm commitment to inclusive immigration views.

Yet why demand integration rather than objecting to immigration altogether? Reducing positive feelings toward immigrants or lowering support for immigration admittance are also improbable responses. First-order immigration attitudes (commonly attitudes on the number of people admitted to a country) are generally stable and resistant to change and, in contexts of high polarization on the issue, immigration attitudes may also inform the individual’s political identity (Kustov, Laaker and Reller, Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021). Again, changes in these preferences and feelings would go against the individual’s sense of being a “good,” genuine person (Aronson, Reference Aronson1968), and potentially challenge her political self-understanding.

Instead, I argue that liberal individuals will likely reduce dissonance by changing second-order immigration preferences, namely preferences on how immigrants should be integrated once admitted. Studies on the relationship between preferences on immigration (entry) and integration (settlement conditions) show that these attitudes are highly interconnected (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Bernat, Bearinger and Resnick2008; Helbling, Reference Helbling2013). To uphold support for one, most people are willing to compromise on the other. Considering the previously mentioned assumption of the positive self-concept and the idea of upholding ingroup distinctiveness, this applies to the case of induced value clashes. When immigrants are perceived as dissonant with ingroup values, enforcing measures that integrate newcomers into the dominant culture and values, outsources the responsibility to change to the outgroup. While stricter integration demands may compromise existing values of pluralism and diversity, it represents a preference adaptation that concerns the rights of the outgroup. This compromise protects ingroup achievements, while at the same time upholding a general positive relationship to the outgroup. Enforcing (positive) ingroup values on the outgroup may, in the end, even be to the outgroup’s benefit. In sum, when experiencing cognitive dissonance as a result of credible femonationalist speech, liberal-pluralistic individuals are likely to compromise their pluralist values and instead demand stricter integration requirements. This happens in an attempt to realign conflicting values, while at the same time upholding a positive self-conception.

H2 (liberal compromise thesis): Exposure to femonationalist speech by a politician from a party that represents an inclusionary immigration stance makes individuals with pro-immigration attitudes more supportive of stricter integration policies.Footnote 5

In sum, this section posits that liberal voters will embrace stricter integration policies in a context where immigration is framed as a problem for gender equality and women’s security. This effect will be stronger if the sender is someone these voters trust, that is, someone who has the same ideological anchoring as the voters. In contrast, nativists will respond more supportive of gender equality policies if they receive femonationalist speech by politicians they can trust in. The effect of femonationalism is, thus, two-fold depending on the prior attitudinal configurations of citizens. In the next section, I present the experimental design to test the two preregistered hypotheses.

4. Case selection

In the U.S. case, contemporary femonationalism is embedded in the broader rightward shift in immigration politics, particularly under Republican leadership. While predominantly championed by Republicans, this logic also serves to justify support for restrictive immigration policies by some Democrats. Prominent examples are those Democratic swing-state Senators who crossed party lines to support the 2025 Laken Riley Act, a deportation law named after a woman murdered by an undocumented immigrant in the previous year (Demirjian, Reference Demirjian2025; U.S. Congress, 2025). The Act, which permits deportation of undocumented immigrants accused, though not convicted, of minor crimes, was commonly discussed and defended referring to violence against women due to immigration (Congressional Record, Vol. 171, No. 13, 2025; Irwin, Reference Irwin2025; Tribune-Review, Reference Tribune-Review2025).

The United States offers a valuable context for testing femonationalist effects, albeit one that differs from European democracies where the phenomenon was first identified and studied. Importantly, it allows examination of whether selective liberal mechanisms extend beyond Muslim outgroups (the primary focus in European contexts) to other immigrant populations such as Latinos. While much existing work and conceptualization focus on anti-Islam sentiment, this case tests whether these mechanisms are more universal and generalizable. We can thus examine not only how this logic travels across national contexts, but also how it can be applied to different outgroups—offering theoretical extension toward a broader understanding of selective liberal politics. The U.S. also presents a challenging test for both outcome variables: American political culture’s emphasis on individual liberty traditionally makes citizens skeptical of mandatory state requirements like integration courses and conditional naturalization (Rothman, Reference Rothman2016) while the rising anti-gender movement (Dietze and Roth, Reference Dietze and Roth2020; Butler, Reference Butler2024) creates potential resistance to gender egalitarian policies. Finding preference adaptations here suggests even stronger effects in contexts where questions of gender and sexuality are less polarized, and where beliefs in personal liberty are less firmly anchored. This is discussed in more detail below.

5. Measuring the effect of femonationalism

To test this theory, a novel, preregistered multifactorial vignette survey experiment was fielded in the United States to a sample of online panel respondents (N = 3,118) in July 2024. Prior to the data collection, a pre-analysis plan was published at the Open Science Framework (OSF) on July 1st, 2024. The plan specifies the two hypotheses, the survey items and index constructions, the estimation procedure, and procedures for data issues as well as exclusion criteria (Appendix 1). The subsequent analysis strictly follows that pre-analysis plan and is complemented by further robustness tests and exploratory analyses. These additional tests do not change the conclusions.

Respondents were recruited via the panel platform Prolific using a quota-based recruitment technique to ensure representativeness with respect to party affiliation and gender (Table A1). As preregistered beforehand, respondents who failed one of two attention checks were excluded from the analysis (Appendix 1). Failed manipulation checks did not serve as a ground for exclusion (with failure rates of 24.2% for MC1 and 6.9 % for MC2, see Tables A9 and A10).

The experimental design seeks to assess whether femonationalism prompts selective endorsement of gender policies and heightened demands for stricter integration. The first outcome variable, gender policy preferences, gauges support for two gender education policies, namely, support levels for school education on women’s rights and equality, and education on sexual consent in public schools. School curricula have historically represented a battleground over liberal advancement in the U.S., and over identity political questions in particular (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2022). Among the most contested topics in recent years are LGBT+ issues—gender identity, sexual orientation, trans and queer rights—but also learning about abortion, and, to a lesser extent, sexuality and sex education (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Bernat, Bearinger and Resnick2008; Polikoff et al., Reference Polikoff, Silver, Rapaport, Saavedra and Garland2022, Reference Polikoff, Fienberg, Silver, Garland, Saavedra and Rapaport2024). The first item assessing gender policy attitudes focuses on the value dimension of gender equality, asking: “Teaching women’s rights and gender equality should be a substantial part of the educational curriculum in American public schools”. The second item to record gender policy attitudes asks “Schools should include mandatory lessons on sexual consent in their curricula”. Spurred by the 2018 #MeToo movement, demands for consent-based sex education, including in pre-college education, are growing in the U.S. (Willis, Jozkowski, and Read, Reference Willis, Kristen and Julia2019; Reiner, Reference Reiner2020); however, the issue remains strongly associated with left-leaning perspectives. In this experimental design, the item on sexual consent speaks in particular to safety-threat-related femonationalist content. Responses to both questions were measured on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “Strongly disagree” to 10 “Strongly agree” allowing for a midpoint option 5 “Neither agree nor disagree.” An index to capture support for gender equality was then calculated by taking the mean of both items, preserving the 0-10 scale. Correlational analysis supports the reliability of the index, with a significant Pearson correlation, ![]() $r = 0.64$, [

$r = 0.64$, [![]() $0.62$,

$0.62$, ![]() $0.66$],

$0.66$], ![]() $p \lt 0.001$, and good internal consistency, Cronbach’s

$p \lt 0.001$, and good internal consistency, Cronbach’s ![]() $\alpha = 0.78$. Both survey items used to measure attitudes toward gender equality were preregistered in advance (Appendix 1, 3).

$\alpha = 0.78$. Both survey items used to measure attitudes toward gender equality were preregistered in advance (Appendix 1, 3).

The second outcome variable, support for strict integration policies, records respondents’ preferences on mandatory language and integration classes for immigrants. The concept is again operationalized as an averaged index of two items. The first question captures the idea of conditional neutralization, linking citizenship eligibility to language acquisition, which dates back to the early 20th century and has remained a subject of debate since (Rothman, Reference Rothman2016). The question records support for the statement: “English language ability should be a prerequisite for becoming U.S. citizen”. The second question asks for agreement with the proposal:“There should be an immigration policy in place that requires new immigrants to take mandatory classes that focus on American societal norms and values and how to integrate into the U.S.” Both items measure public demands for newcomers to prove civic belonging and the implicit (language) and explicit (value courses) engagement with the way of life in the host country, as well as the imposition of adopting the host country’s culture and values. While similar policies are common in Nordic states such as Norway, which emphasize collective welfare and social cohesion (Hagelund, Reference Hagelund2005), voters in the U.S. traditionally value individual and cultural liberties. This makes these questions a particularly compelling test for this study, as American perspectives may not be easily swayed. Response options for both questions were again presented on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 “Strongly disagree” to 10 “Strongly agree” with the midpoint option of 5 “Neither agree nor disagree.” To capture support for stricter integration policies, a combined index was calculated by taking the mean of both questions, again, preserving the 0-10 scale. Correlational analysis demonstrates the robustness of the second outcome index, with a significant Pearson correlation, ![]() $r = 0.60$, [

$r = 0.60$, [![]() $0.58$,

$0.58$, ![]() $0.62$],

$0.62$], ![]() $p \lt 0.001$, and satisfactory internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s

$p \lt 0.001$, and satisfactory internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s ![]() $\alpha = 0.75$. The survey items measuring both outcome variables were encoded as voluntary questions, meaning participants were not forced to express their preferences on any item and, hence, not pressured to select one over the other.

$\alpha = 0.75$. The survey items measuring both outcome variables were encoded as voluntary questions, meaning participants were not forced to express their preferences on any item and, hence, not pressured to select one over the other.

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups or a control group (Table A7 shows balance across treatment groups). Before answering outcome questions, those in the treatment groups read a fictive interview excerpt in which a U.S. senator makes a femonationalist claim. Treatments 1 and 2 featured a Republican politician, while Treatments 3 and 4 featured a politician from the Democratic party. The statements also varied by threat framing: Treatment groups 1 and 3 received a value threat frame (immigrants as a threat to gender equality), while groups 2 and 4 received a safety threat frame (immigrants as a threat to women’s safety; see Figure 1). The fictive vignette design allows systematic variation of both source and threat content without introducing other, uncontrollable differences between treatments. To resemble real-world femonationalist rhetoric, the vignettes were designed as short newspaper interview excerpts, explicitly labeled as such in the preamble. The text consisted of an interviewer’s brief question followed by a longer response from an unnamed, gender-neutral politician whose party affiliation (Republican/Democratic) was stated in both the preamble and the speaker label. The key femonationalist claim is contained in the interview reply by the politician: The statement first acknowledges an immigration-related threat (either a value or safety threat frame), then attributes it to the cultural backgrounds of immigrants, and concludes with a call to action (Figure 2). The vignettes were crafted to reflect typical femonationalist rhetoric without mirroring any specific politician’s or party’s communication style, avoiding activating existing background beliefs and preferences (Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey, Reference Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey2018). To assess comprehension, two Factual Manipulation Checks (FMCs; Kane and Barabas, Reference Kane and Barabas2019) were included. Results show that 93.1% of treated respondents correctly identified the interview topic, and 75.8% recalled the politician’s party affiliation (Tables A9 and A10). These checks suggest that respondents retained the femonationalist message more than the communicator’s partisanship. FMCs were preregistered and used to evaluate treatment perception, but failing them did not lead to exclusion.

Figure 1. Experiment design.

Figure 2. Vignettes.

The theoretical outline posits that the effect of the independent variable, that is, femonationalist speech, on citizens’ policy preferences depends on individuals’ prior attitudes toward immigrants. Anti-immigration respondents will display increased levels of support for gender education policies, while immigration supporters will display higher support levels for stricter integration demands after being exposed to femonationalist speech. Equation 1 formalizes these theoretical expectations. Thereby, the treatment variable is a five-level factor indicating exposure to one of the treatment conditions (1–4, respectively) or to the control condition (0). The immigration attitudes variable represents prior attitudes toward immigrants that condition the effect of the femonationalist treatment. Immigration attitudes were measured prior to treatment as part of a longer feeling thermometer, asking respondents to express their feelings both toward documented immigrants and toward undocumented immigrants. To avoid priming about immigration, the two items are embedded in a list of various individuals and groups. Responses are recorded on a scale from 0 “Dislike a great deal” to 100 “Like a great deal.” General immigration attitudes were indexed by averaging both item scores and included as a continuous predictor in the interaction term.

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1\text{Treatment}_i + \beta_2\text{ImmigrationAttitudes}_i & \\

+ \beta_3\text{Treatment}_i \times \text{ImmmigrationAttitudes}_i + \epsilon_i

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1\text{Treatment}_i + \beta_2\text{ImmigrationAttitudes}_i & \\

+ \beta_3\text{Treatment}_i \times \text{ImmmigrationAttitudes}_i + \epsilon_i

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} The central estimant is the Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE) of the femonationalist treatment on the outcomes for each respondent group, that is the average treatment effect (![]() $\Delta = \mathbb{E}[Y_1] -

\mathbb{E}[Y_0]$) for each subgroup. The estimated CATEs for pro- and anti-immigration respondents are presented in the Appendix Tables A15 and A16. As a robustness test, the model is also run with a set of covariates, including the respondents’ gender (men vs. other), a dummy for being born in the U.S., a dummy for having an immigration background (one or both parents born abroad vs both parents born in the U.S.), ethnicity (white vs. other), age by cohort, residence (larger city, or, suburb to a larger city vs. other) and education levels (highest obtained degree). Covariates were included as a robustness test. The subsequent analysis follows the preregistered analysis plan strictly, including the alternative model specifications and the inclusion of covariates. All analyses were conducted using R 4.4.0 (R Core Team, Reference R Core Team2024).

$\Delta = \mathbb{E}[Y_1] -

\mathbb{E}[Y_0]$) for each subgroup. The estimated CATEs for pro- and anti-immigration respondents are presented in the Appendix Tables A15 and A16. As a robustness test, the model is also run with a set of covariates, including the respondents’ gender (men vs. other), a dummy for being born in the U.S., a dummy for having an immigration background (one or both parents born abroad vs both parents born in the U.S.), ethnicity (white vs. other), age by cohort, residence (larger city, or, suburb to a larger city vs. other) and education levels (highest obtained degree). Covariates were included as a robustness test. The subsequent analysis follows the preregistered analysis plan strictly, including the alternative model specifications and the inclusion of covariates. All analyses were conducted using R 4.4.0 (R Core Team, Reference R Core Team2024).

6. Results

Selective support for gender policies (H1): Does femonationalist speech mobilize social liberal gender preferences among voters with conservative immigration views? Figure 3 presents the observed effect of femonationalist messages by a Republican politician on gender education policy preferences across all levels of immigration attitudes. Lower scores on the x-axis correspond to adverse views toward immigrants, while higher levels reflect more supportive (liberal) views. The upper panels plot the estimated regression slopes for treatment group 1, that is, respondents who received a message describing immigrants as threatening to gender equality (upper left plot), and for treatment group 2 who received a safety threat framing (upper right plot). The two lower panels present the Conditional Average Treatment Effects (CATEs) across the full range of prior immigration attitudes. The blue control group line in the upper plots confirms the expectation that more liberal views on immigration correspond to higher levels of support for gender education in schools. Support levels among respondents with positive immigration views are high both in the control and in the treated groups. Among nativist respondents, this differs. Those exposed to either treatment condition (T1 or T2) and with negative immigration attitudes display significantly higher support levels for gender education compared to their counterparts in the control group. This difference is slightly larger for the group that saw a safety threat message (T2) than for those who receive a value threat treatment (T1). The CATE between treatment and control is stronger with more adverse attitudes toward immigrants: an individual with an immigration attitude score of 10 is likely to score .83 (T1) and 1.05 (T2) points higher in gender education support after exposure to a femonationalist argument, while individuals with an immigration attitude level of 25 score .68 (T1) and .84 (T2) points higher on average. These results provide causal evidence for the first hypothesis that femonationalist speech by a Republican politician significantly increases support for liberal gender education policies among individuals with negative immigration attitudes (H1). The assumption of linearity of the interaction term was confirmed by additional diagnostic tests, meaning that the effects change at a constant rate with prior immigration attitudes (Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu, Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Yiqing2019, Figures A1 and A2).

Figure 3. Conditional average treatment effect on support for gender policies (N=3118). The x-axis represents pre-treatment attitudes toward immigrants, where lower values reflect more negative attitudes and higher values reflect more positive attitudes. The figure is based on the full-sample interaction specification (Model 2 in Table A11).

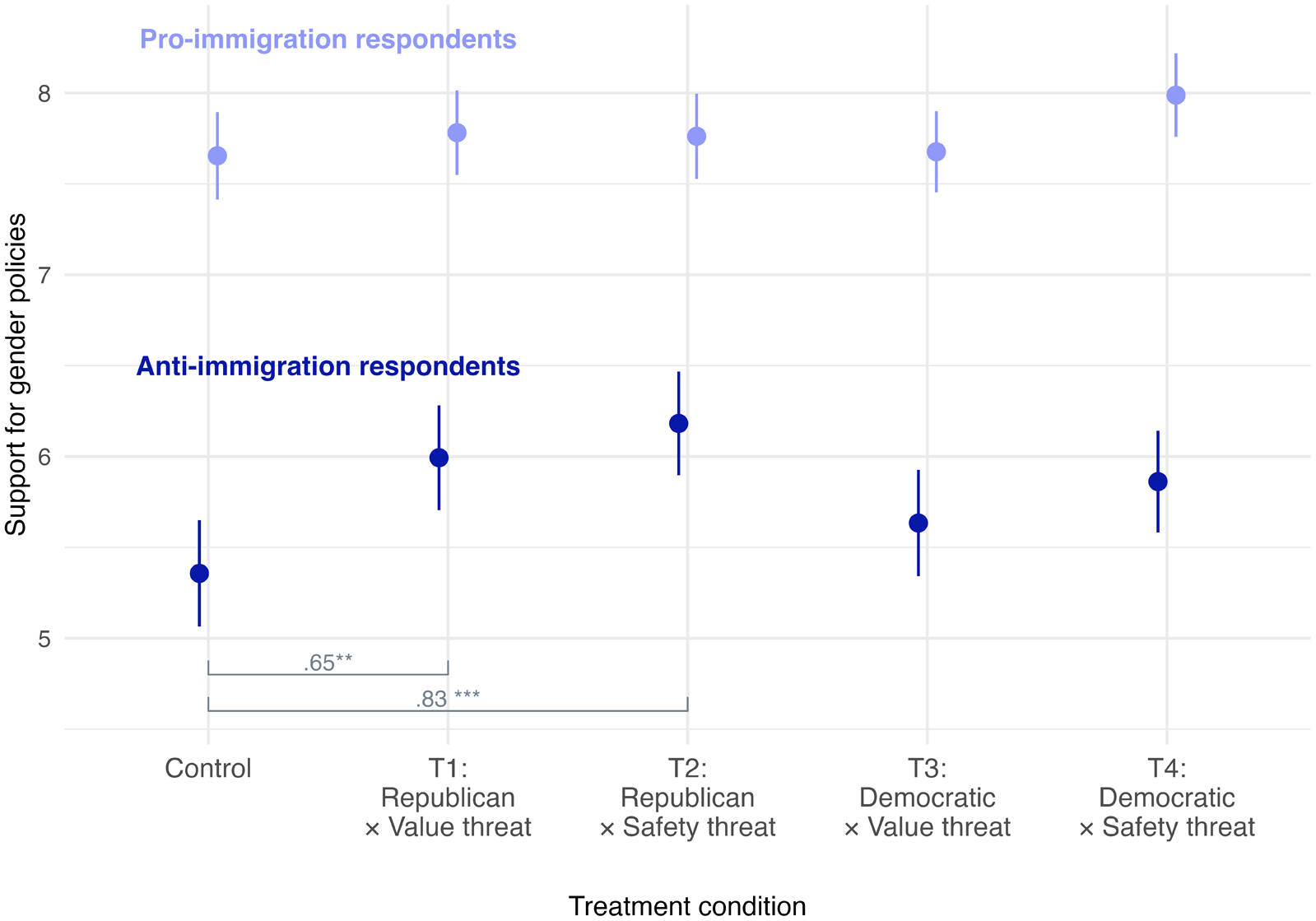

In Figure 4, the hypothesized disidentification thesis (H1) is presented in more detail by stratifying the sample into pro- and anti-immigration respondents. The graph plots the mean support levels for gender education policies (0-10 on the y-axis) for all four treatment conditions (T1-T4) and the control group (control) for a dichotomous stratified sample relational to prior immigration attitudes. The mean estimates are based on the full-sample interaction specification (Model 2 in Table A11). For a complete report of all differences in means see Table A15. Among immigration supporters (upper points), support for gender inclusive education is overall higher with only a small increase for those who were exposed to a safety-based femonationalist claim by a Democratic politician (T4), scoring .331 points higher (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .1$) than the control baseline. Beyond that, the treatments do not impact gender support levels within this group. Among anti-immigration respondents, all treated groups display higher support levels compared to the control group. The baseline mean of the control group is estimated at 5.36. Compared to that, immigration opponents who received a femonationalist claim by a Republican politician become significantly more inclined to favor gender education. For those who read a message describing immigrants as a threat to gender values this difference is .65 (

$\mathrm{p} \lt .1$) than the control baseline. Beyond that, the treatments do not impact gender support levels within this group. Among anti-immigration respondents, all treated groups display higher support levels compared to the control group. The baseline mean of the control group is estimated at 5.36. Compared to that, immigration opponents who received a femonationalist claim by a Republican politician become significantly more inclined to favor gender education. For those who read a message describing immigrants as a threat to gender values this difference is .65 (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .05$) points (T1), while those receiving a safety-threat description increase their support levels by .83 (

$\mathrm{p} \lt .05$) points (T1), while those receiving a safety-threat description increase their support levels by .83 (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .01$) points (T2). Messages by Democratic politicians do not show such strong effects on nativists: only treatment condition 4, that is the interview with a Democratic politician problematizing safety concerns, has a small impact with a .44 point increase (

$\mathrm{p} \lt .01$) points (T2). Messages by Democratic politicians do not show such strong effects on nativists: only treatment condition 4, that is the interview with a Democratic politician problematizing safety concerns, has a small impact with a .44 point increase (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .1$). This suggests that the receptiveness to femonationalist speech for people with averse immigration views is greater if the message comes from a like-minded source. We cannot, however, rule out that femonationalist messages from more liberal sources impact this group as well: the coefficients of the Democratic treatments are slightly smaller in magnitude (.35 and .44) but point in the same direction as those of the Republican treatment conditions. Further, the difference in means between the Democratic and Republican treatments is not in itself statistically significant, besides for a weak difference (

$\mathrm{p} \lt .1$). This suggests that the receptiveness to femonationalist speech for people with averse immigration views is greater if the message comes from a like-minded source. We cannot, however, rule out that femonationalist messages from more liberal sources impact this group as well: the coefficients of the Democratic treatments are slightly smaller in magnitude (.35 and .44) but point in the same direction as those of the Republican treatment conditions. Further, the difference in means between the Democratic and Republican treatments is not in itself statistically significant, besides for a weak difference (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .1$) between T3 and T2. This difference between the safety message by a Republican with the strongest CATE (T2 at .83) and the value-based Democratic message with the weakest CATE (T3 at .35), is likely attributable to the size of the coefficients (Table A15).

$\mathrm{p} \lt .1$) between T3 and T2. This difference between the safety message by a Republican with the strongest CATE (T2 at .83) and the value-based Democratic message with the weakest CATE (T3 at .35), is likely attributable to the size of the coefficients (Table A15).

Figure 4. Mean support levels for gender policies (N=3118).

Compromising integration attitudes (H2): The second part of the analysis shifts focus toward those respondents who hold positive views toward immigrants. In line with the second hypothesis (H2), this section assesses whether femonationalist speech mobilizes illiberal integration preferences among voters with inclusive immigration views. Figure 5 summarizes the effects of femonationalist speech by a Democratic politician on integration preferences across all prior immigration attitudes. The top left panel depicts the estimated slopes for control and treatment group 3, those exposed to a description of immigrants as a threat to gender values. On the right is the respective plot for treatment group 4 who received a safety-threat message by a Democratic politician. Values on the y-axis reflect the scores on the combined measure for integration demands (0–10) with lower values indicating disagreement to assimilationist policies, and higher values reflecting approval. The lower panels show the predicted CATEs of the two treatments across all levels of immigration attitudes. A negative control slope in the upper panels confirms that more liberal immigration views are associated with more inclusive stances on integration, dropping below a value of 4 (on a scale between 0 and 10) for the highest 20 percent. On the flip side, nativist views are correlated with demands to integrate, scoring up to 10 for those feeling most negative about immigrants. Among nativists, receiving treatment shows little to no difference, possibly due to ceiling effects, except for a negative CATE for T1 among the lowest quartile (immigration attitude scores ![]() $ \lt 25$). A slight increase in support levels can be observed among nativists in the second treatment group, that is the safety threat condition. The difference in trends between treatment and control increases with higher immigration values. Those who received a femonationalist statement by a Democratic politician and share positive views toward immigrants deviate significantly from immigration advocates in the control group. This effect is slightly stronger for messages with a safety threat framing (T4) compared to value threat frames (T3), whilst this difference between treatment conditions is not significant (Table A16). An individual with an immigration score of 90 is likely to score .81 (T3) and .98 (T4) points higher in integration demands if exposed to a femonationalist claim. Notably, individuals with immigration views between 67 and 75 (T3) and 67 and 78 (T4) are likely to express approval for the suggested integration demands (

$ \lt 25$). A slight increase in support levels can be observed among nativists in the second treatment group, that is the safety threat condition. The difference in trends between treatment and control increases with higher immigration values. Those who received a femonationalist statement by a Democratic politician and share positive views toward immigrants deviate significantly from immigration advocates in the control group. This effect is slightly stronger for messages with a safety threat framing (T4) compared to value threat frames (T3), whilst this difference between treatment conditions is not significant (Table A16). An individual with an immigration score of 90 is likely to score .81 (T3) and .98 (T4) points higher in integration demands if exposed to a femonationalist claim. Notably, individuals with immigration views between 67 and 75 (T3) and 67 and 78 (T4) are likely to express approval for the suggested integration demands (![]() $ \gt 5$) after exposure to a femonationalist message, while their counterparts in the control group are more likely to express disapproval (

$ \gt 5$) after exposure to a femonationalist message, while their counterparts in the control group are more likely to express disapproval (![]() $ \lt 5$). Consistent with theoretical expectations, these results confirm that immigration supporters become significantly more supportive of assimilationist integration policies when exposed to femonationalist speech by Democratic politicians, providing causal evidence for H2. Again, these effects are not conditioned by the assumption of linearity of the interaction term (Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu, Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Yiqing2019, Figures A1 and A2).

$ \lt 5$). Consistent with theoretical expectations, these results confirm that immigration supporters become significantly more supportive of assimilationist integration policies when exposed to femonationalist speech by Democratic politicians, providing causal evidence for H2. Again, these effects are not conditioned by the assumption of linearity of the interaction term (Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu, Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Yiqing2019, Figures A1 and A2).

Figure 5. Conditional average treatment effects on support for stricter integration policies (N=3118). The x-axis represents pre-treatment attitudes toward immigrants with lower values representing negative attitudes toward immigrants and higher numbers representing positive attitudes toward immigrants. The figure is based on the full-sample interaction specification (Model 2 in Table A12).

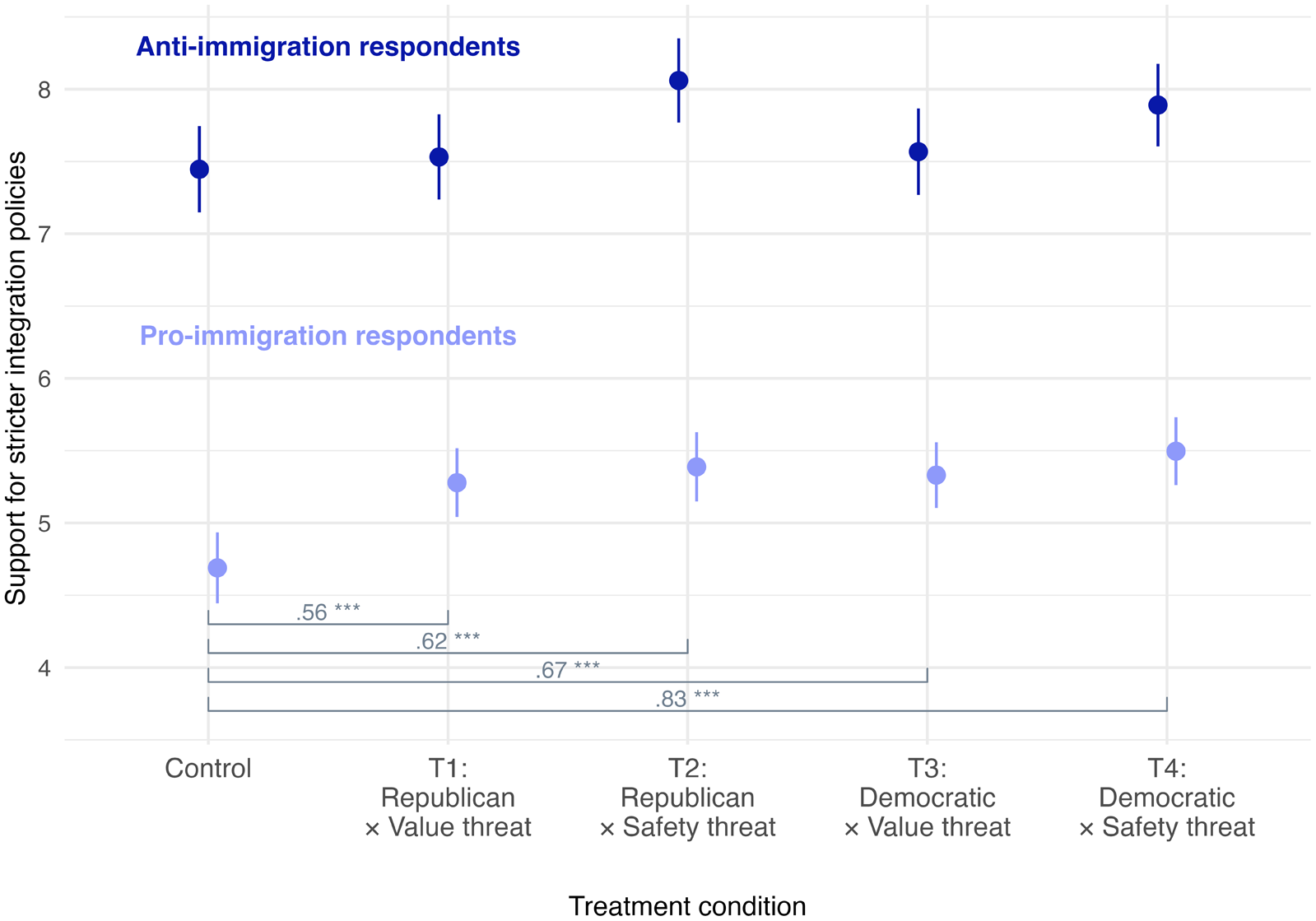

Figure 6 presents a streamlined test of the liberal compromise mechanism by aggregating estimations of the CATE on the group level. The plot depicts mean support levels for stricter integration policies (0-10) among anti-immigration respondents (top) and pro-immigration respondents (bottom). The estimates are based on the full interaction model (Model 2, Table A12). The comparison in means provides further support for H2. Among immigration supporters, both T1 (CATE=.67) and T2 (CATE=.83) have a strong, significant effect on integration preferences (![]() $\mathrm{p} \lt .01$). The baseline mean of the control group is estimated at 4.69, suggesting disapproval of these policies (below the mid-point of 5). On average, this means that immigration supporters are more likely to approve of conditional naturalization and mandatory integration courses after exposure to a femonationalist message (

$\mathrm{p} \lt .01$). The baseline mean of the control group is estimated at 4.69, suggesting disapproval of these policies (below the mid-point of 5). On average, this means that immigration supporters are more likely to approve of conditional naturalization and mandatory integration courses after exposure to a femonationalist message (![]() $ \gt 5$ on a scale from 0 strongly disagree to 10 strongly agree), while they are more likely to disapprove of such measures if they see no such message (

$ \gt 5$ on a scale from 0 strongly disagree to 10 strongly agree), while they are more likely to disapprove of such measures if they see no such message (![]() $ \lt 5$). The effect is substantively larger for immigration proponents exposed to a safety threat description than for those exposed to the value-based claim (Table A16). Unlike expected, the effect of femonationalism on integration preferences among pro-immigration respondents is independent of the communicator’s party affiliation: there are strong effects across all four treatments, including those interview excerpts with a Democratic senator (T3 and T4) and those with a Republican (T1 and T2) (all p

$ \lt 5$). The effect is substantively larger for immigration proponents exposed to a safety threat description than for those exposed to the value-based claim (Table A16). Unlike expected, the effect of femonationalism on integration preferences among pro-immigration respondents is independent of the communicator’s party affiliation: there are strong effects across all four treatments, including those interview excerpts with a Democratic senator (T3 and T4) and those with a Republican (T1 and T2) (all p ![]() $ \lt .01$). Here, again, the CATE of the safety threat treatment is slightly higher (CATE=.62) than of the value threat one (CATE=.56). Compared to pro-immigration respondents, nativist respondents score high on assimilationist integration demands regardless of the treatment condition, or whether they received no treatment. Only the safety threat argument by a Republican (T2) leads to a significant difference between treatment and control among nativists (Table A16). Overall, these findings offer strong support for H2. Not only that, the analysis also shows that femonationalism raises support for stricter integration policies among pro-immigration individuals regardless of the sender’s partisanship, even when endorsed by Republican politicians.

$ \lt .01$). Here, again, the CATE of the safety threat treatment is slightly higher (CATE=.62) than of the value threat one (CATE=.56). Compared to pro-immigration respondents, nativist respondents score high on assimilationist integration demands regardless of the treatment condition, or whether they received no treatment. Only the safety threat argument by a Republican (T2) leads to a significant difference between treatment and control among nativists (Table A16). Overall, these findings offer strong support for H2. Not only that, the analysis also shows that femonationalism raises support for stricter integration policies among pro-immigration individuals regardless of the sender’s partisanship, even when endorsed by Republican politicians.

Figure 6. Mean support levels for stricter integration demands (N=3118).

Heterogeneous effects: This section introduces an additional exploratory analysis to examine gender-based variation in selective (il)liberal preferences adaptations. Therefore, a third interaction term is included in the model, enabling the estimation of group-specific predictions by gender (Tables A17 and A18). The results, visualized in Figure 7, present a parsimonious test of the role respondents’ gender plays in the relationship by stratifying the sample according to prior immigration attitudes (dichotomous) and two gender groups—men and respondents who identify as women or other genders. The figure is organized vertically by immigration attitude, with nativists on the left and immigration supporters on the right. The upper panels illustrate differences in means for support for gender policies, while the lower panels display support for stricter integration policies. Relevant to H1 is the upper left panel, which reveals overall similar trends between nativist men and respondents identifying as women or other. Men in the baseline control group show lower support for gender policies compared to women and others in the control group. When treated with a message by a Republican politician, men are significantly more supportive of gender policies than the control baseline (T1: ![]() $\beta = 1.26$ and T2:

$\beta = 1.26$ and T2: ![]() $\beta = 1.06$, both at

$\beta = 1.06$, both at ![]() $p \lt 0.01$). The effect of treatment conditions 1 and 2 on women and others is also positive, however, not significant (

$p \lt 0.01$). The effect of treatment conditions 1 and 2 on women and others is also positive, however, not significant (![]() $p \lt 0.1$ for T2). Treatment condition 4 (a safety threat message by a Democratic politician) yields the strongest effect on nativist women and others (

$p \lt 0.1$ for T2). Treatment condition 4 (a safety threat message by a Democratic politician) yields the strongest effect on nativist women and others (![]() $\beta = 0.81$,

$\beta = 0.81$, ![]() $p \lt 0.05$). These findings indicate that nativist men seem responsive to the message source: the effects are strongest for messages by a Republican politician. Nativist women, on the other hand, seem sensitive to the threat framing. They display weak preference shifts when receiving a safety-threat message by a Republican, and moderate adaptations for safety-threat messages by a Democrat.

$p \lt 0.05$). These findings indicate that nativist men seem responsive to the message source: the effects are strongest for messages by a Republican politician. Nativist women, on the other hand, seem sensitive to the threat framing. They display weak preference shifts when receiving a safety-threat message by a Republican, and moderate adaptations for safety-threat messages by a Democrat.

Figure 7. Mean support levels by gender for gender policies (top) and strict integration policies (bottom) (N=3118).

Relating to H2, the lower right panel illustrates how liberal men respond to the treatment compared to women and others. Baseline support for integration demands is higher among men than the rest of the sample, with the control group scoring 0.5 points higher on average. This pattern holds across all treatment groups, with women and others being generally less supportive of conditional naturalization and mandatory integration courses for immigrants than men. Nonetheless, both groups exhibit strongly significant treatment effects (Appendix Table 18, p.17). The estimated mean effect sizes for women and others indicate that this group responds strongly to all four treatment conditions, while showing slightly stronger responses to safety-threat frames than to value-threat frames. Men respond strongly to both threat framings, but are sensitive to the communicators’ partisanship. The estimated CATEs for men are largest for messages by Democratic politicians (T3: ![]() $\beta = 0.76$ and T4:

$\beta = 0.76$ and T4: ![]() $\beta = 0.88$, both at

$\beta = 0.88$, both at ![]() $p \lt 0.01$). These findings support the notion that, regardless of gender, individuals with positive views on immigration are inclined to endorse stricter integration policies when exposed to femonationalist rhetoric by a liberal source (H2). Responses to Republican politicians are mostly driven by liberal women and other genders.

$p \lt 0.01$). These findings support the notion that, regardless of gender, individuals with positive views on immigration are inclined to endorse stricter integration policies when exposed to femonationalist rhetoric by a liberal source (H2). Responses to Republican politicians are mostly driven by liberal women and other genders.

Robustness: To assess the robustness of H1 and H2, I conducted sensitivity tests, including a multiverse analysis varying model specifications and covariate inclusion (Tables A11 and A12). Results remained stable across models with all preregistered covariates and strengthened when adding party affiliation as an additional covariate. The main analysis was also replicated using partisanship as an alternative sample split, yielding consistent and stronger effects. Additionally, a placebo test confirmed no treatment effect on corporate tax policy preferences, except for a weak, non-robust effect for T1 among anti-immigration respondents (Table A14).

The results indicate that individuals infer stereotypes about prominent immigrant outgroups when exposed to femonationalism, despite the use of the generic term “immigrants.” A manipulation check confirms this: Over half of the 2,520 treated respondents associated the message with Muslims (N=1,249) or Latinos (N=1,148), while few mentioned other groups (Table A8).Footnote 6

To explore whether respondents associated different threat frames with specific immigrant groups, I examined which immigrant groups respondents mentioned when asked what came to mind while reading the treatment. Of those assigned to safety-threat conditions, 40.5% mentioned Muslims compared to 58.6% in value-threat conditions. For Latinos, the pattern reversed: 49.0% in safety-threat groups mentioned Latinos compared to 42.1% in value-threat conditions (Table A8). Chi-square tests confirm these differences are highly significant for both Muslims (![]() $\chi^2 = 81.81$,

$\chi^2 = 81.81$, ![]() $p \lt .001$) and Latinos (

$p \lt .001$) and Latinos (![]() $\chi^2 = 11.81$,

$\chi^2 = 11.81$, ![]() $p \lt .001$). These findings reveal that U.S. respondents associate value threats more strongly with Muslims and safety threats more strongly with Latinos, aligning with research showing that Latino immigrants are narratively framed as perpetrators of violent crime against White women (Smilan-Goldstein, Reference Smilan-Goldstein2024) while opposition to Muslim Americans stems from Orientalist notions about Islam as incompatible with American values (Lajevardi and Oskooii, Reference Lajevardi and Oskooii2018; Oskooii, Dana and Barreto, Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2021). However, substantial proportions mentioned both groups across conditions, suggesting that while these associations are patterned, they are not exclusive.

$p \lt .001$). These findings reveal that U.S. respondents associate value threats more strongly with Muslims and safety threats more strongly with Latinos, aligning with research showing that Latino immigrants are narratively framed as perpetrators of violent crime against White women (Smilan-Goldstein, Reference Smilan-Goldstein2024) while opposition to Muslim Americans stems from Orientalist notions about Islam as incompatible with American values (Lajevardi and Oskooii, Reference Lajevardi and Oskooii2018; Oskooii, Dana and Barreto, Reference Oskooii, Dana and Barreto2021). However, substantial proportions mentioned both groups across conditions, suggesting that while these associations are patterned, they are not exclusive.

7. Discussion

Aiming to understand how the promotion of selective liberalism by elite politicians impacts voters’ policy preferences, this article assesses whether femonationalist speech mobilizes American citizens in defense of progressive achievements—either by embracing liberal gender policies, or by supporting stricter, diversity-limiting integration policies. The experiment provides causal evidence for such effects conditional on voters’ prior attitudes toward immigrants. The findings reveal significant preference adaptations among nativist and progressive citizens, and provide support for the two preregistered hypotheses (H1 and H2).

It is long established that voters who harbor negative predispositions toward immigrants and support exclusionary ideas and policies also tend to endorse conservative values on other social and cultural issues, including gender (Hetherington and Weiler, Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). If these culturally illiberal voters embrace pro-women or gender sensitive stances, it is often motivated by benevolent sexism (Barreto and Doyle, Reference Barreto and Doyle2022) and fit into the framework of traditional views on family and gender roles. While this holds true, the empirical findings presented here provide evidence for another motivation for conservatives to embrace more progressive stances on gender issues: the desire to distance themselves from an (ethnic) outgroup that challenges these values. The findings demonstrate that nativist citizens can be swayed to strategically liberalize their stance on gender education when exposed to elite statements presenting immigrants as a threat either to the safety and liberty of women (safety threat) or to gender equality more broadly (value threat). This selective liberalism is likely a function of negative effect against the immigrant outgroup and the nationalization of liberal values (Læ gaard, Reference Lægaard2007) (progressive values as American values) vis-a-vis the immigrant outgroup that is perceived to represent illiberal values. The urge to disassociate themselves from the disliked group, and the narrative of danger to the status quo, activates selective support for gender issues even if it is precisely those issues, like educating on women’s rights, sex education on consent, that are often not promoted and sometimes even challenged by conservative forces. This effect is strong and substantive for messages by Republican politicians, that is, those elite actors who themselves represent more conservative views. For femonationalist speech by liberal, Democratic actors the results are mixed. This could suggest that the disidentification mechanism is conditional on the individual’s receptiveness to the message in the first place.

This, however, tells only half the story. The majority of voters in the U.S. harbor inclusive attitudes toward immigration, support diversity, and hold more liberal, progressive views on issues of gender and sexuality (Welzel, Reference Welzel2013; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2018). How do these voters respond to elite femonationalism? In this paper, it has been demonstrated that when confronted with an induced clash between gender achievements and immigration, voters with positive immigration attitudes strive to protect liberal achievements by supporting stricter demands for integration. When confronted with the claim that immigrants pose a threat either to gender equality or women’s safety, pro-immigration citizens move from disapproving of such policies to joining intolerant citizens in their demand for assimilationist integration measures. Without intervention, this group opposes policy proposals that require new immigrants to take mandatory classes on American societal norms and values that effectively enforce cultural and social adaptation. The same applies to reforms that make English language proficiency a prerequisite for citizenship, an idea often criticized for introducing linguistic and cultural barriers to obtaining rights and benefits. For those committed to diversity, multi-ethnicity, and inclusive tolerance, pivoting their stance to support these proposals marks a stark and substantive shift away from pluralistic values. This is especially striking in the U.S. context, which has long cultivated an awareness of multi-ethnicity, minority inclusion, and diversity. This selective illiberal preference adaptation in response to femonationalist claims can be understood as an attempt to resolve the cognitive dissonance introduced by the politician’s statement: When confronted with a conflict between two cherished liberal values that one would otherwise support independently, an individual is under pressure to reconcile these values. Beyond expectations, there is no source attribution effect for selective illiberal responses; individuals with inclusive immigration attitudes display a strong and significant response to femonationalist statements, regardless of the politician’s party affiliation. Given the highly polarized climate in the U.S., this finding is striking and suggests that citizens primarily react to the message content, that is the juxtaposition of liberal values, and not to party cues.