Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis worldwide, with radiographic findings of variable cartilage destruction, loss of joint space, osteophyte formation, and cyst formation, which contribute to the development of pain and stiffness over time. Reference Glyn-Jones, Palmer and Agricola1 The Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study found that OA accounted for 14.9 million incident cases, 303.1 million prevalent cases, and 9.6 million years lived with disability in 2017. Reference Westbury, Fuggle and Pereira2 In a large cohort study from Canada of adults over the age of 20, the average age of diagnosis for OA (any joint) was 50 years, with 30.4% diagnosed before the age of 45. Reference Wilfong, Badley and Perruccio3 The main modifiable risks for the development of OA are obesity and joint injury. Reference Allen, Thoma and Golightly4 Aetiology is multifactorial, with increasing age being the main risk factor to both onset and severity. Reference Weiss and Jurmain5

Despite the association between increasing age and the development of OA, there is evidence that early life also contributes. In a study of 444 older adults who were born, and continue to live, in Hertfordshire, lower birth weights were associated with increased likelihood of hip osteophytes after adjustment for confounders; similarly, lower weight gain at one year was associated with increased burden of knee osteophytes in the lateral compartment. Reference Clynes, Parsons and Edwards6

Although the association between early life and the development of radiographic OA is established, Reference Clynes, Parsons and Edwards6 the association between early life and the development of symptomatic OA is less explored. Given the implications for loss of independence with symptomatic OA in older adults, Reference Araujo, Castro, Daltro and Matos7 we considered this question among individuals with baseline radiographic knee OA in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, a population-based cohort of community-dwelling older people, and examined early life factors and baseline participant characteristics in relation to risk of knee pain at a subsequent follow-up stage.

Methods

The Hertfordshire Cohort Study

The HCS comprises 1579 men and 1418 women who were born in Hertfordshire (UK) from 1931 to 1939 and who still lived there in 1998–2004. Information on their early life was recorded in birth ledgers, including birth weight and weight at one year of age. In 1998–2004, they completed a home interview and attended a clinic for a detailed assessment of their health. More detailed information about this study has been published previously. Reference Syddall, Sayer and Dennison8,Reference Syddall, Simmonds and Carter9

In total, 966 participants from East Hertfordshire underwent a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan at baseline. In 2004, 642/966 were recruited to a musculoskeletal follow-up study. In 2011, 591 were invited to participate in an additional follow-up study; 443 agreed to participate. A flow diagram of the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the study. The analysis sample comprised individuals with baseline radiographic knee OA (K&L score = 2) who had information on WOMAC pain at follow-up and had no history of knee replacements according to information at both baseline (1998–2004) and follow-up (2011).

HCS had ethical approval from the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Local Research Ethics Committee at baseline and the 2011 follow-up had ethical approval from the East and North Hertfordshire Ethical Committees. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration (as amended) or comparable standards. Participants gave written informed consent to participate and for their health records to be accessed in future.

Ascertainment of early life characteristics

As previously reported, birth weights of HCS participants were recorded in ledgers by midwives. Reference Syddall, Sayer and Dennison8 Health visitors took the weight of the babies at one year of age; these measurements were originally recorded in imperial units (pounds and ounces) and were later converted into kilograms. Conditional infant weight gain (CIWG) was derived separately for males and females, as previously described. Reference Syddall, Sayer and Simmonds10 This is a measure of infant growth which is independent of birth weight. During the home interview (1998–2004) participants were asked at what age they left full-time education.

Ascertainment of characteristics at baseline (1998–2004)

During home interviews (1998–2004), participants’ smoking status (never smoker, previous smoker, or current smoker), weekly alcohol consumption, and physical activity levels Reference Dallosso, Morgan and Bassey11 were collected though clinician-administered questionnaires. Participants also filled out a food-frequency questionnaire; principal component analysis was applied to these data to obtain a prudent diet score where healthier diets were indicated by higher scores. Reference Robinson, Syddall and Jameson12 Participants’ most recent or current full-time job for men and unmarried women (and the husband’s job for married women) was used to determine occupational social class. These jobs were then grouped according to the 1990 OPCS Standard Occupational Classification (SOC90) unit group for occupation. 13 Information on housing tenure (owned/mortgaged or rented/other) was also ascertained. Information was recorded on all over the counter and prescription medications that participants were currently taking; these were categorised according to the British National Formulary. The number of systems medicated was used as a marker of morbidity level.

At the baseline clinic, height was measured (Harpenden pocket stadiometer, Chasmors Ltd, London, UK) in addition to weight (SECA floor scale, Chasmors Ltd, London, UK), and these were used to derive body mass index (BMI). The subset from East Hertfordshire had radiographs of both knees (standing antero-posterior and lateral). Joints were then graded based on the Kellgren and Lawrence (K&L) grading system. Reference Kellgren and Lawrence14 The maximum score over both regions and both knees was used as the K&L score for each participant; individuals with radiographic knee OA were regarded as those with a K&L score ≥ 2.

Ascertainment of characteristics at follow-up (2011)

At the 2011 home visit, questionnaires were administered by clinicians which included ascertainment of knee pain via the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale. Reference Bellamy, Buchanan and Goldsmith15 Information on all over-the-counter and prescription medications that participants were currently taking were recorded in the same way as at baseline; information on whether participants were taking medications for pain was also ascertained at this time point. After the 2011 home visit, knee radiographs were taken at a local hospital. Knee osteophyte score was calculated as the maximum osteophyte score across the left and right sides of the following sites: tibiofemoral lateral, tibiofemoral medial, and patellofemoral.

Statistical methods

Participant characteristics were described using summary statistics. Logistic regression models were used to examine each of the following baseline characteristics separately in relation to risk of knee pain at the 2011 follow-up: female sex; age; birth weight; weight at one year; CIWG; height; weight; BMI; ever smoked (yes vs no); alcohol intake; physical activity; prudent diet score; left school before age 15 (yes/no); manual social class (yes/no); housing tenure (own/mortgaged property versus not); and number of systems medicated. Models were initially adjusted for sex and follow-up time, then additionally adjusted for knee osteophyte score, and then further adjusted for use of painkillers at follow-up. To enable the comparison of effect sizes, continuous variables were standardised, so they had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Men and women were pooled to increase statistical power. Stata, release 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to conduct all statistical analysis. The analysis sample comprised individuals with baseline radiographic knee OA (K&L score ≥ 2) who had information on WOMAC pain at follow-up and had no history of knee replacements according to information at both baseline (1998–2004) and follow-up (2011) (Figure 1).

Results

Participant characteristics

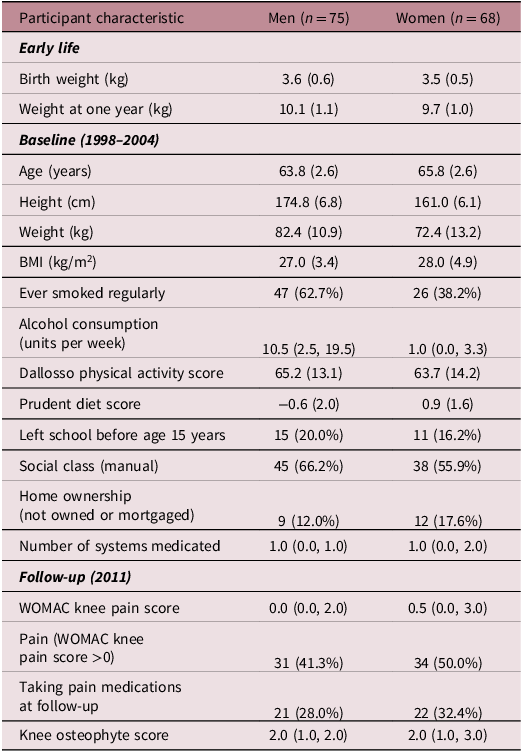

Participant characteristics in early life, at baseline (1998–2004), and at follow-up (2011) are illustrated in Table 1. Mean (SD) age at baseline was 63.8 (2.6) among men and 65.8 (2.6) among women; mean (SD) values were greater among men than women for birth weight (3.6 (0.6) kg vs 3.5 (0.5)) and weight at one year (10.1 (1.1) kg vs 9.7 (1.0)). Overall, 41.3% of men and 50.0% of women had knee pain (WOMAC pain score >0) at follow-up.

Table 1. Participant characteristics of the analysis sample

WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Knee osteophyte score: maximum osteophyte score across the left and right sides of the following sites: tibiofemoral lateral, tibiofemoral medial, and patellofemoral.

Association between participant characteristics and knee pain at follow-up (2011)

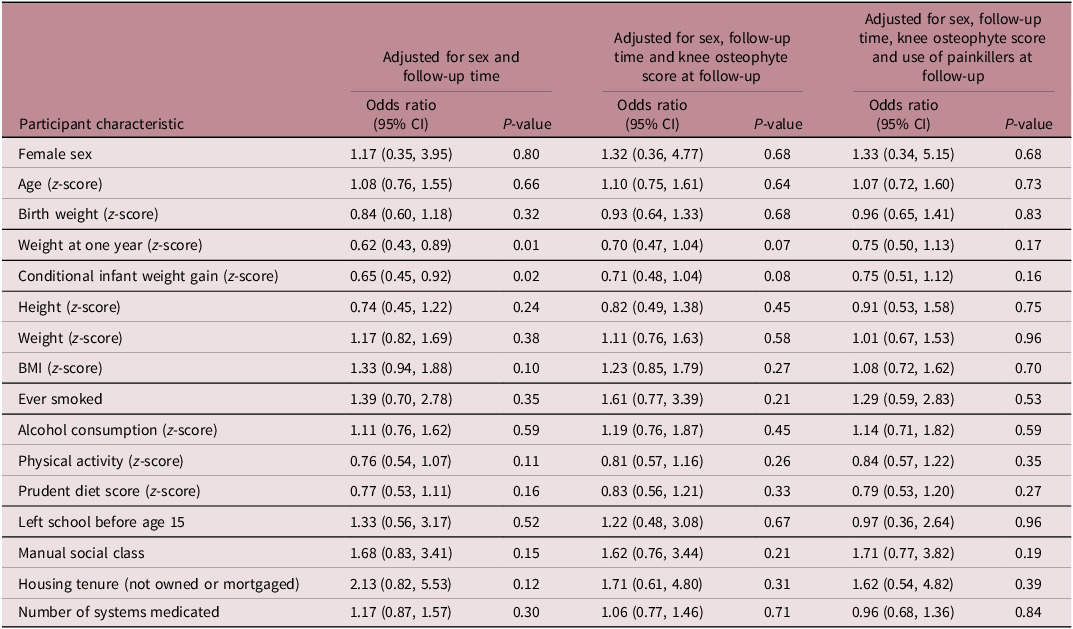

Odds ratios for knee pain (WOMAC pain score >0) at follow-up according to various participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. Greater weight at one year and greater CIWG gain were each related to reduced risk of knee pain at follow-up after adjustment for sex and follow-up time; for example odds ratios (95% CI) for knee pain per standard deviation increase in weight at one year and CIWG were 0.62 (0.43, 0.89) (p = 0.01) and 0.65 (0.45, 0.92) (p = 0.02) respectively. When additionally adjusted for knee osteophyte score, associations were attenuated for both weight at one year (0.70 (0.47, 1.04), p = 0.07) and CIWG (0.71 (0.48, 1.04), p = 0.08). These associations were further attenuated after additional adjustment for use of painkillers at follow-up (p > 0.15 for both associations). No associations were observed for any of the other participant characteristics.

Table 2. Odds ratios for knee pain (WOMAC pain score >0) at follow-up (2011) according to participant characteristics in early life and at HCS baseline (1998–2004)

Associations between infant weight and knee pain at follow-up can also be demonstrated by examining mean (SD) values for weight at one year (kg) according to presence versus absence of knee pain at follow-up. These values were 9.8 (1.2) versus 10.3 (1.1) among men, and 9.5 (1.0) vs 9.9 (1.0) among women (data not shown).

Discussion

Among Hertfordshire Cohort Study participants with baseline radiographic knee OA, greater weight gain in infancy was protective against knee pain at follow-up; this association was attenuated after adjustment for knee osteophyte score. These findings are aligned with previous results of early life factors being associated with development of radiographic changes but also demonstrate an association between early life factors and the symptom of pain in OA.

The relationship between radiographic evidence of OA and the experience of symptoms is complex. Duncan et al found that more severe pain, measured on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) scale (a validated measure of pain and disability suggestive of OA), and longer lasting pain were both associated with more severe radiographic changes of OA. Reference Clynes, Parsons and Edwards6 However, age also contributed with older people more likely to have definitive OA than the younger people included in the study with similar WOMAC scores. Reference Duncan, Peat, Thomas, Hay, McCall and Croft16 Radiographic changes of OA only become visible some years after the onset of the disease process, Reference Glyn-Jones, Palmer and Agricola1 but pain and associated loss of function are also individual experiences and are composed of both psychological and physical components which cannot accurately be assessed by radiograph. Reference Cubukcu, Sarsan and Alkan17 Our findings suggest that early life factors feed into this relationship.

Although the reason for this is not clear, it is possible that early factors ‘set up’ neuropathic pain. We have previously demonstrated that genetic variation at the neurokinin 1 receptor gene (TACR1) was associated with pain in individuals with radiographic knee OA in this cohort. Reference Warner, Walsh and Laslett18 Given that we are aware of gene – early life interactions for both the VDR Reference Arden, Syddall and Javaid19 and GH genes, Reference Dennison, Syddall and Jameson20 it is possible that similar relationships are also relevant in the aetiology of knee pain, for example with the TACR1 gene. Vitamin D levels have been associated with knee pain in the Hertfordshire Cohort; in previous work both birth weight and polymorphisms in the VDR gene were associated with the presence of lumbar spine osteophytes and a significant interaction was observed between these 2 factors in men. Reference Jordan, Syddall, Dennison, Cooper and Arden21

Quadriceps strength is an important factor in the maintenance of function and pain management in clinical knee OA, and resistance training to maintain muscle health is a key element of management. Reference Liu, Yin and Li22 Previous work in this cohort has shown relationships between early growth and balance in later life, Reference Martin, Syddall, Dennison, Cooper and Sayer23 and several studies have shown positive relationships between early growth and adult grip strength, a commonly used surrogate for muscle mass. Reference Dodds, Denison and Ntani24 Although our sample was too small to consider these relationships adequately, this is an important area to consider in future work in larger cohorts.

The associations between growth in early life and knee pain were attenuated by adjustment for the presence of osteophytes on X-ray. Although OA was traditionally considered a degenerative joint condition, it is now recognised that is a heterogenous condition with many active pathological processes. Reference Tang, Zhang and Oo25 Osteophyte formation is one of the diagnostic criteria for radiographic OA and is thought to represent a proxy for cartilage loss, an important element of OA development. Reference Markhardt, Li and Kijowski26 They form in the periosteum at the junction between cartilage and bone, when chondrogenic cells ossify to become a chondro-osteophyte before eventually forming an osteophyte. Reference Markhardt, Li and Kijowski26 It is thought they can be linked to pain through periosteal stretching, or perhaps because of their association with cartilage degradation. Reference Markhardt, Li and Kijowski26

This study has several strengths, for example, HCS was conducted by well-trained fieldworkers who implemented rigorous phenotyping protocols. Use of a CIWG measure that is independent of birth weight enables the partitioning of the effect of birth weight and the effect of growth after birth. However, our study does have limitations. First, a healthy participant effect has been observed in HCS, and attrition across follow-up waves may have exacerbated this effect and resulted in possible bias if the analysis sample was not representative of the wider population. However, the baseline HCS was found to be broadly comparable to the Health Survey for England, which is nationally representative. Reference Syddall, Sayer and Dennison8 Second, the sample size of the study was small, given the number of exposures considered. This may have reduced the statistical power to detect true associations and increased the possibility that some observed associations were due to chance. However, our findings are biologically plausible and consistent with previous studies. Finally, WOMAC scores were only available for each person, rather than for each knee.

The findings from this study suggest that early life factors may play a role in the development of symptomatic OA in later life. This highlights the need for further research into the mechanisms by which early life growth impacts joint health and pain.

Acknowledgements

We thank the men and women who have participated in the Hertfordshire studies, the Hertfordshire General Practitioners, and all the nurses and doctors who have conducted HCS fieldwork over many years.

Financial support

FKW is an NIHR academic clinic fellow. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Competing interests

NRF reports speaker fees for UCB, Viatris and Amgen, and travel bursaries from Pfizer and Eli Lilly.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and have been approved by the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire Local Research Ethics Committee at baseline and the 2011 follow-up had ethical approval from the East and North Hertfordshire Ethical Committees.