13.1 Introduction

The extent to which democracy is able to secure itself against its enemies is a topic of heated debate today. To illustrate, we could mention recent discussions on the advisability of banning the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) in Germany, as well as the decision, in January 2024, of the German Federal Constitutional Court to deny public funds and tax breaks legally available to German parties to a far-right party – Die Heimat, formerly known as the NPD.Footnote 1 In other contexts, attempts have been made to ban extremist parties such as the Hellenes in Greece.Footnote 2 These discussions, however, are not new. In the 1930s, Hans Kelsen argued against restraining political competition to protect democratic systems – in other words, against the idea of ‘militant democracy’.Footnote 3

Kelsen’s antagonistic relationship with ‘militant democracy’ is well established in the literature and is not a matter of controversy.Footnote 4 Karl Loewenstein pioneered militant democracy in 1935, and it is indisputable that Kelsen challenged this paradigm.Footnote 5 Kelsen, to be sure, never uses the expression ‘militant democracy’, even though it had been circulating since at least the second half of the 1930s. Nevertheless, even without explicitly mentioning the concept, he clearly manifested his opposition to democratic governments attempting to assert themselves against the will of the majority in any way. The debate on appropriateness and legitimacy precedes the emergence of the term. Theories of militant democracy avant la lettre, such as that of George van den Bergh,Footnote 6 were available even before ‘militant democracy’ became a term of art.

Considering the political events he went through, Kelsen’s opposition to regulating democratic competition was astonishingly consistent and unaffected by even the most tragic events: the rise of fascism in Europe and the persecution of Jews, from which he personally suffered. The widespread conviction in the 1930s that ‘democracy may be structurally weak’Footnote 7 did not shake Kelsen’s conviction that we must not interfere in democratic processes, even to safeguard democracies against their most resolute enemies. After the collapse of the Weimar Republic, a large number of political thinkers arrived at a consensus ‘on the fundamental principle underlying the theory and practice of militant democracy: Democracies have a right to limit fundamental rights of free expression and participation – albeit with various qualifications and caveats – for reasons of self-preservation’.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, Kelsen’s resistance to militant democracy was not weakened or qualified by this consensus.Footnote 9 His resistance to militant democracy was consistently reiterated in The Essence and Value of Democracy,Footnote 10 ‘Verteidigung der Demokratie’,Footnote 11 General Theory of Law and State,Footnote 12 ‘Absolutism and Relativism in Philosophy and Politics’,Footnote 13 ‘What is Justice?’,Footnote 14 and ‘Foundations of Democracy’.Footnote 15

Although Kelsen’s opposition to ‘militant democracy’ appears indisputable, I would like to examine his position for two reasons, each of which justifies a specific section in this paper. In Section 13.2, I attempt to deeply and systematically anchor Kelsen’s opposition to militant democracy in his theory of democracy, intending to explain why his opposition was so surprisingly immune to, first, the defeat of democracies – as painfully observed in the 1930s – and, second, the shared convictions of many of his contemporaries that such vulnerability legitimised the decision to stop ‘anti-democratic parties from abusing the democratic process to gain the political power to realise anti-democratic goals’.Footnote 16 I argue that Kelsen’s main reasons for rejecting militant democracy were intrinsically linked to the foundations of his democratic theory: first, relativism, excluding the regulation of political competition;Footnote 17 second, the primacy of majority rule, in which democracy was conceived of as government by and not for the people;Footnote 18 third, the hypervalorisation of political compromise, which KelsenFootnote 19 presented as closely compatible with relativism and capable of protecting minorities from immoderate political options; and fourth, a minimal conception of deliberation, according to which every political position must have ‘the opportunity to express itself and to compete openly for the affections of the populace’. If Kelsen had abided by the principle of militant democracy, he would have had to invalidate the main foundations of his democratic theory. I argue this explains his inflexibility regarding militant democracy.

In Section 13.3, I examine the contemporary reception of Kelsen regarding his reluctance to allow interference with political competition. Political theorists broadly agree that Kelsen’s neutral model of liberal democracy, which prohibits democrats from interfering with democracy even if it is the only option left to save the system from its demise, ‘has virtually no supporters [left] today’.Footnote 20 This assertion, eloquently expressed by Capoccia,Footnote 21 can be qualified by showing that since the beginning of the 2000s, the opposition to militant democracy has gained some support, most obviously from empirical studies underlining that the costs of militant forms of democracy outweigh the benefits of counteracting extremist, radical-right or antisystem parties.Footnote 22 It is also true, however, that very few political theorists fully support Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy. In this section, I specifically evaluate the affiliation between Kelsen and Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman,Footnote 23 two of those rare political theorists who have explicitly endorsed Kelsen’s resistance to militant democracy. Even when, on isolated occasions, Kelsen inspires opposition to militant democracy, his arguments are not taken up in their entirety. Relativism, which plays a crucial role in his refusal to limit political competition, has disappeared from contemporary arguments.

In sum, in Section 13.2, I identify and assess the doctrinal pillars of Kelsen’s surprisingly consistent opposition to militant democracy, despite his awareness of vulnerabilities inherent to democracy. I also look for blind spots in the main premises that underpin his rejection of militant democracy. In Section 13.3, in turn, I first re-evaluate the widespread opinion that Kelsen has no contemporary supporters of his rejection of militant democracy. Second, I discuss the lines of consistency – inconsistency between Kelsen and a new generation of authors sharing doubts about militant democracy. Through these analyses, this chapter provides a fresh perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of Kelsen’s perspective on militant democracy and evaluates his influence on contemporary literature on the topic.

13.2 The Four Pillars of the Kelsenian Rejection of Militant Democracy

In the first section of this paper, I systematise Kelsen’s main reasons backing his case against militant democracy. Before delving in, I must present a clear definition of militant democracy. According to Pfersmann,Footnote 24 ‘militant democracy is a political and legal structure aimed at preserving democracy against those who want to overturn it from within or those who openly want to destroy it from outside by utilising democratic institutions as well as support within the population’.Footnote 25 This definition focuses on what militant democracy aims at: democratic self-defence. Examining how we would enable our democracy to protect itself, most theorists to date have assumed that militant democracy presupposes illiberal measures, such as legal restrictions on the rights of expression and political participation of groups and associations that are perceived as a threat to a given democratic regime.Footnote 26 Minority voices considering what measures to use in support of militant democracy have either preferred the educational dimensionFootnote 27 to repressive techniques or proposed a combination of these two options.Footnote 28 CapocciaFootnote 29 noted that militant democracies have historically sought to be both repressive in the short term and educational in the long term.

Kelsen’s consistent rejection of militant democracy – even if he does not use this term – is puzzling, considering that his position does not emerge from a naïve, Panglossian perspective of politics or from a political context that could give the illusion that democracy is resistant enough to survive antidemocratic forces. On the contrary, Kelsen’s position was forged at a time that called explicitly into question the solidity of democratic regimes, notably in the high political turbulence of the new Weimar Republic, with its tragic outcome of falling to the Third Reich, which persecuted him due to his Jewish origins.Footnote 30 As PfersmannFootnote 31 shows, the experience of the 1930s strengthened three convictions: that democratic claims and attitudes are fragile, that legal transitions from democratic to nondemocratic governments are smooth, and that the enemies of democracy will not hesitate to undermine it by any means whatsoever. Interestingly, there is no real controversy among scholars (at least in the 1930s) over the fragility and vulnerability of democracies. Kelsen shares this pessimism and does not argue that democracies are especially resilient when they face antidemocratic movements:

[Democracy] is the form of government that defends itself the least against its adversaries. It seems condemned to the tragic fate of having to feed its worst enemy at its own breast. If it is to be true to itself, it has to tolerate even a movement targeting the destruction of democracy, and grant it the same development opportunity as to any other conviction. Therefore, we see the bizarre spectacle of democracy, by its very own means, abolishing itself of a people demanding the rights taken away that it had given itself because someone has succeeded in having these people believe its own right to be its greatest evil. In the face of such a situation, one wishes to believe in Rousseau’s pessimistic words: Such a perfect form of government would be too good for humans, only a people of gods would be able to govern itself democratically in the long run.Footnote 32

Kelsen’s aversion to militant democracy arises at a different level, namely, the legitimate responses we can offer to the vulnerability of our democracies. Given the fragility of democracy, the controversy revolves around how far we can go to protect democracies from succumbing. Under such an interrogation, two paradigms have emerged, which are unequally represented. On the one hand, supporters of militant democracy, represented by the major pioneering figure of Loewenstein,Footnote 33 argued that ‘democracy cannot be blamed if it learns from its ruthless enemy and applies in time a modicum of the coercion that autocracy will not hesitate to apply against democracy’. In 1932, SchmittFootnote 34 evoked the contours of a ‘new theory’ with an ‘opinion held by many current public law scholars that there must be some boundary to constitutional amendment’. Loewenstein is rightly presented by Schmitt as a supporter of this ‘new type of theory’. Given Schmitt’s proven commitments to Nazism, it may seem highly counterintuitive today that he was one of the Weimar jurists who emphasised that ‘value neutrality’ could lead to ‘the point of system suicide’.Footnote 35 Coming from the opposite position, Kelsen is a major representative of supporters of the neutral model of liberal democracy, which argues that ‘all political positions should be given equal rights of expression and participation’Footnote 36 and claims more generally that protecting democracies cannot justify an antidemocratic exclusion of certain political voices. Such a perspective remains minoritarian. Both models – as described above – correspond to the two models that have prevailed since the end of the Second World War: the American and the German models. In the so-called American model, ‘the state provides for as much freedom as possible. This means that all ideas are accepted in the democratic ‘marketplace of ideas’, whether they are democratic or not’.Footnote 37 The German model, called the streitbare or wehrhafte Demokratie,Footnote 38

is based on the legal system in post-war Germany, which has largely been influenced by the Weimar legally and the Allie[s’] (and German elite’s) distrust of the German population. As in the American model, anti-democratic actions are severely punished. But the German state has also explicitly defined the fundamental principles of the free democratic order, and prohibits not only actions, but also ideas that are opposed to these principles.Footnote 39

In 1932, perceiving acutely the Achilles’ heel of democracy’s extreme vulnerability, Kelsen described a dilemma which could be solved only by deciding between the pros and cons of militant democracy: ‘In the face of this situationFootnote 40 also arises the question of whether one should not refrain from providing a theoretical defence of democracy’. Without any ambiguity, KelsenFootnote 41 answers this question in his essay ‘Verteidigung der Demokratie’: ‘A democracy that asserts itself against the will of the majority, possibly by violent means, has stopped being a democracy’. He remains unwavering in his view even after 1945.

Kelsen’s persistence, consistency and even obstinacy in rejecting militant democracy – even when history has shown the risks of such neutrality – can be explained by the danger that militant democracy poses to the very foundations of Kelsenian democratic theory. However, the doctrinal sources of his rejection of militant democracy are poorly documented and systematised in the literature. In the following, I locate and explore the four pillars of Kelsen’s opposition to militant democracy, which are intimately connected to four (strongly interrelated) cardinal aspects of his democratic theory: relativism, the pre-eminence of majority rule (derived from proceduralismFootnote 42), the decisive place of political compromises between the majority and minority as a natural, mechanical way to regulate ‘excesses’ of political discourses, and a minimal conception of deliberation (less elaborated in the literature).

First and fundamentally, Kelsen connects his rejection of militant democracy to relativism. Following Lars Vinx, Kelsen’s conception of relativism consists of a general philosophical worldview that places the fallibilityFootnote 43 of judgements, both of value and of fact, at its core.Footnote 44 This fallibility implies, for Kelsen, a duty to ‘value everyone’s political will equally’ and to give ‘equal regard to each political belief and opinion’ in the democratic context.Footnote 45 Later, KelsenFootnote 46 affirms that ‘the moral principle underlying a relativistic theory of value, or deductible from it, is the principle of tolerance’. Moreover, he states that ‘tolerance, minority rights, freedom of speech, and freedom of thought’ are characteristic of democracy and antagonistic to belief in absolute values.Footnote 47 However, KelsenFootnote 48 makes clear that such tolerance limits itself to opinions only, according to the American model mentioned earlier:

It will be self-evident that a relativistic world-outlook engenders no right to absolute tolerance; it enjoins tolerance only within the framework of a positive legal order, which guarantees peace among its subjects, in that it forbids them any use of force, but does not restrict the peaceful expression of their opinions.

Kelsen’s tolerance is not for use ‘in fine weather only’: he reaffirmed the value of tolerance when democracy ‘is obliged to defend itself against anti-democratic intrigues’.Footnote 49 Even in such conditions, democracy has to reaffirm its specific attribute (i.e., tolerance) to distinguish it from autocratic regimes: ‘We are entitled to repudiate autocracy, and to be proud of our democratic form of government, only so long as we preserve this distinction. Democracy cannot defend itself by abandoning its own nature’.Footnote 50

Although Kelsen is fully aware of the difficulty in distinguishing between opinions and acts, he does not offer solutions to demarcate them:

It may be hard in the process to draw a clear dividing line between the dissemination of certain ideas and the preparation of a revolutionary coup. But the possibility of preserving democracy depends on the possibility of finding such a dividing line. It may also be true that such line drawing itself contains a certain danger. But it is the nature and pride of democracy to take this danger upon itself; if it cannot endure such danger, it is not worthy of defence.Footnote 51

Limiting relativism to actions presupposes a clear distinction between actions and opinions (or discourses), since no serious scholar would endorse a relativist assessment of actions. This distinction, however, is not without difficulty. Following Schauer,Footnote 52 I consider the distinction between speech and action to be untenable, especially if, as Emerson mistakenly claims,Footnote 53 ‘expression is […] conceived [of] as doing less injury to other social goals than action. It generally has less immediate consequences, is less irremediable in its impact’. This distinction between the verbal and the physical has been challenged even in contemporary debates about hate speech.Footnote 54 Given that Kelsen’s adherence to relativism relies heavily on the distinction between speech and action, if the sphere of action cannot be clearly defined, then the principle of relativism is at least debatable.

Secondly, as mentioned above, if there is, according to Kelsen’s relativism, no possibility of discovering absolute values or the ‘absolute good’,Footnote 55 then when the population is confronted with several political choices, a democratic system can only let the majority decide:Footnote 56

If […] it is recognised that only relative values are accessible to human knowledge and human will, then it is justifiable to enforce a social order against reluctant individuals only if this order is in harmony with the greatest possible number of equal individuals, that is to say, with the will of the majority.Footnote 57

Kelsen’s procedural approach, which is considered the polar opposite of militant democracy,Footnote 58 is embodied in the democratic context as majority rule, whatever the consequences of the majority decision might be.Footnote 59 Consequently, the social order must be determined as often as possible by the will of the majority, and as seldom as possible by contradicting it:

The idea underlying the principle of majority is that the social order shall be in concordance with as many subjects as possible, and in discordance with as few as possible. Since political freedom means agreement between the individual will and the collective will expressed in the social order, it is the principle of simple majority which secures the highest degree of political freedom that is possible within society.Footnote 60

Interestingly, the citizen incompetence that Kelsen lucidly envisages does not moderate his support for the supremacy of majority rule. This position stresses, once again, his non-naïve defence of majority rule, which is most conducive to the right to self-determination:

To legislate, and that means to determine the contents of a social order, not according to what objectively is the best for the individuals subject to this order, but according to what these individuals, or their majority, rightly or wrongly believe to be their best – this consequence of the democratic principles of freedom and equality is justifiable only if there is no absolute answer to the question as to what is the best, if there is no such a thing as an absolute good. To let a majority of ignorant men decide instead of reserving the decision to the only one who, in virtue of his divine origin, or inspiration, has the exclusive knowledge of the absolute good – this is not the most absurd method if it is believed that such knowledge is impossible and that, consequently, no single individual has the right to enforce his will upon the others. That value judgments have only relative validity, one of the basic principles of philosophical relativism, implies that opposite value judgments are neither logically nor morally impossible. It is one of the fundamental principles of democracy that everybody has to respect the political opinion of everybody else, since all are equal and free.Footnote 61

Kelsen’s defence of majority rule is not buttressed by the Rousseauist conviction that the majority is right and the minority is wrong, much less that the losing voter is expected to change his or her mind. Kelsen’s relativism implies scepticism of the correctness of the majoritarian choice. Building on that scepticism, minority groups ‘must have a chance to express their opinion freely and must have a full opportunity of becoming the majority’.Footnote 62

However, this approach ignores how the democratic game does not guarantee an alternation in power between majorities and minorities,Footnote 63 especially when there are ‘structural majorities’ or persistent minorities. The problem of representation for persistent minorities may have been obscured or downplayed by the highly optimistic expectation that today’s losers can expect to be tomorrow’s winners.Footnote 64 Indeed, we should not mask the reality that some groups have no hope of returning to power or winning by referendum because of their structural characteristics as minorities. These groups can then be considered as suffering from political inequality, ‘if political equality is not to be strictly procedural, but linked to outcomes and justifications for them’.Footnote 65 As we shall see in the following section, Kelsen’s solution to political inequality is based on a conception of majoritarian decision-making that naturally includes minority voices by way of compromise. While this solution is consistent with Kelsen’s procedural view of democracy and offers a normatively satisfactory response to political inequality, it raises questions of plausibility that we will address in the next section.

The two aforementioned pillars supporting Kelsen’s opposition to militant democracy – relativism and majority rule (derived from proceduralism and rooted in relativism) – are not fully intelligible if they are not related to a third element, which is compromise, taking up a central place in Kelsen’s conception of democratic decision-making. Compromises are an integral part of the democratic relativistic constellation.Footnote 66 As KelsenFootnote 67 points out, ‘there is nothing more characteristic of the relativistic worldview than the tendency to seek a balance between two opposing standpoints’. Given that there is no access to political truths, compromise appears to be a reasonable, sensible way to define political will because it does not exclude minorities – which cannot be proven wrong – from its makeup. Compromise appears to be the ultimate – perhaps the only – safeguard, consistent with his legal positivism, against excessive options that might threaten minorities. It should also be noted that compromises are already part of the Kelsenian understanding of majority rule, incorporating the necessary protection of minorities:Footnote 68

The rule of the majority, which is so characteristic of democracy, distinguishes itself from all other forms of rule in that it not only by its very nature presupposes, but actually recognises and protects – by way of basic rights and freedoms and the principle of proportionality – an opposition, i.e., the minority. The stronger the minority, however, the more the politics in a democracy become politics of compromise. Similarly, there is nothing more characteristic of the relativistic worldview than the tendency to seek a balance between two opposing standpoints, neither of which can be itself be adopted fully, without reservation, and in complete negation of the other.Footnote 69

However, Kelsen might be too optimistic regarding the natural tendency of the majority party to institute self-restraints. In other words, it overestimates the inclination to compromise. In Kelsen’s account, the majority never excludes the minority from the formation of the will of the state out of fear of endangering the democratic process. For him, self-restraint and compromise almost naturally accompany the application of majority rule, without Kelsen truly explaining why.Footnote 70 In the interwar period, Hermann Heller had already expressed a less optimistic view when he emphasised the need to ensure that democracies contained integration mechanisms. In this sense, HellerFootnote 71 suggested that relations between majorities and minorities were not necessarily inclined towards moderation but instead could sink into violent power relations. Moreover, if the minority has no realistic prospect of ever ending up in power, especially if its minority status includes structural characteristics linked to religion or language, then the majority certainly has fewer incentives to include the minority’s preferences.

Furthermore, compromise might not be able to regulate every political conflict. According to Golding,Footnote 72 ‘the compromisable conflict situation is one in which there is a partial coincidence of interests and which, therefore, contains the seeds of competition and cooperation’. Mutual concessions are feasible only if a ‘coincidence of interests or values’ exists because each party has to ‘gain something from a compromise’.Footnote 73 In addition, as Schumpeter conveys, if compromises are related to contradictory and ultimate values, then they are tendentially more difficult to realise because the differences can be irreducible.Footnote 74 Kelsen clearly underestimates the conflictual situations in which the protagonists have neither latitude nor interface for compromise.

Fourth, and this is less documented in the literature, Kelsen’s reluctance to protect popular self-government from the peopleFootnote 75 also builds on a conception of political debate whereby every political conviction must have ‘the opportunity to express itself and to compete openly for the affections of the populace’.Footnote 76 At first glance, such a perspective has some proximity to the Schumpeterian democratic method, underlining the necessity of a pluralist competition of leaders (political actors) for votes.Footnote 77 However, for Kelsen, this element of competition contains a minimal deliberative feature that Schumpeter ignores. For Kelsen,Footnote 78 competing for votes accompanies a ‘dialectical process in both the popular assembly and parliament, which is based on speech and counterspeech’. This pluralist exchange of arguments ‘paves the way for the creation of norms’.Footnote 79 Such a minimal deliberative element also emerges in the General Theory of Law and State, where a ‘running discussion between majority and minority’Footnote 80 characterises democracy.

Kelsen’s conception of public debate has nothing to do with the paradigm of the ‘free market of opinion’, according to which a ‘true belief can be recognised and strengthened only by its constant exposure to error in the free market of opinion’.Footnote 81 Indeed, the minimal deliberative element present in Kelsen’s conception of public debate does not aim at the truth or even an approximation of it. We might therefore ask why Kelsen introduced this minimal deliberative component if democracy is reduced to a fair procedure of majority rule – a view that Estlund labelled ‘fair proceduralism’.Footnote 82 If it was only a matter of a guarantee of free and equal access to the vote, why did Kelsen add the minimal deliberative component in the form of a ‘running discussion between majority and minority’?Footnote 83 It seems that Kelsen is discreetly moving towards what EstlundFootnote 84 eventually called a ‘fair deliberative proceduralism’, where ‘citizens ought to have an equal or at least fair chance to enter their arguments and reasons into the discussion prior to voting’. How is this minimal element of deliberation compatible with Kelsen’s definition of self-determination, which seems to be limited to the will of the majority?

I suggest two answers to this puzzle. The ‘running discussion’ between citizens and representatives that Kelsen mentions is, first, related more to a condition of expressing ‘political emotions’, which is considered an indispensable ingredient in democracies, than to open rational deliberation. In The Essence and Value of Democracy,Footnote 85 Kelsen indeed adds that

the mechanics of democratic institutions are directly aimed at raising the political emotions of the masses to the level of social consciousness, so that they can dissipate. Conversely, the social equilibrium in an autocracy rests on the repression of these political emotions into a sphere, which may be compared to the subconscious on the individual psychological level.

Kelsen and Loewenstein conceive of emotions very differently in a democratic context. Kelsen gave a special, albeit discreet, place to emotions in the stability of democratic regimes. While emotions are repressed in dictatorial regimes,Footnote 86 democratic regimes allow them to circulate. From the opposite perspective, Loewenstein argued that democracy did not develop naturally or effectively in the realm of the emotions and therefore could not combat dictatorships on this terrain: ‘One method of overcoming fascist emotionalism would certainly be to counterbalance or outdo it with similar emotional devices. Obviously, the democratic state cannot undertake this undertaking’.Footnote 87 Second, discussion is valued in Kelsenian democratic theory because it facilitates the creation of compromises: ‘Free discussion between majority and minority is essential to democracy because this is a way to create an atmosphere favorable to compromise between majority and minority’.Footnote 88

This element of deliberation renews our understanding of the Kelsenian principle of self-determination, which here seems to go beyond the simple expression of the will of the majority. The deliberative component serves, on the one hand, to oil the gears of the relations between minorities and majorities. As early as 1929, Kelsen offered a definition of majority rule that included minority preferences.Footnote 89 The exchange of arguments also served this objective. On the other hand, the deliberative element is a vehicle for the expression of political emotions, to which Kelsen gives a significant, if discreet, place in his democratic theory.

In this section, I have systematised the main reasons why Kelsen rejects militant democracy. As previously shown, these reasons are intrinsically linked to the foundations of his democracy theory: relativism, excluding the regulation of political competition; deriving from the first foundation, the primacy of the majority rule favouring government by the people and excluding government for the people;Footnote 90 Kelsen’s hypervalorisation of political compromise, which he presents as highly compatible with relativismFootnote 91 and able to protect minorities from immoderate political options; and last, a minimal conception of deliberation according to which every political position must have ‘the opportunity to express itself and to compete openly for the affections of the populace’.Footnote 92

As previously noted, these four pillars of Kelsen’s objections to militant democracy – or at least three of them – have fractures. Among the most serious is the conceptual fuzziness surrounding the distinction between actions and opinions, which could undermine the ability to restrict relativism to political opinions. Indeed, when opinions are hostile to freedom, they can lead to punishable acts. Second, the procedural choice of majority rule for deciding collective issues conceals the fact that minorities and majorities do not always alternate power in a democratic context and the fact that minorities might be excluded in the long run in the determination of the collective will. Third, the majority’s self-restraint and their natural inclination for compromise are overestimated in some contexts. Fourth, I believe that the minimal deliberative element does not constitute an Achilles heel of Kelsenian thought. It renews and enriches our understanding of the principle of self-determination, which is also oriented to its capacity to integrate minority voices.

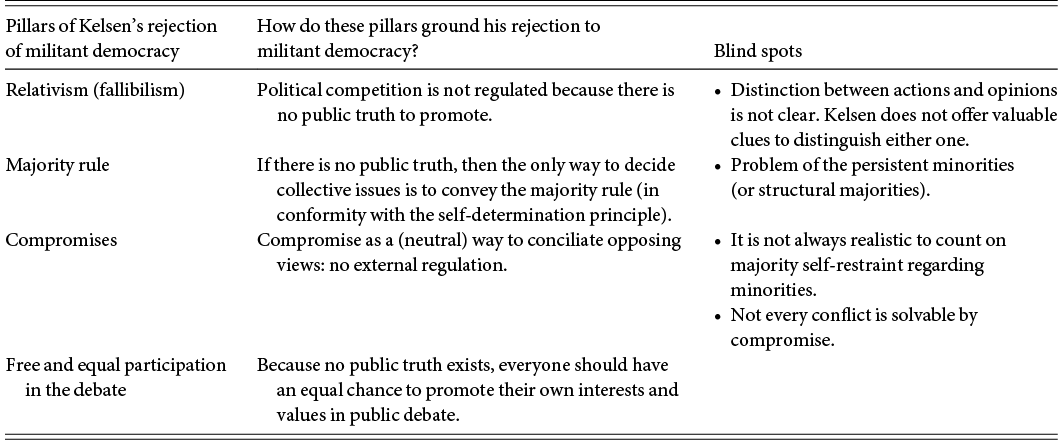

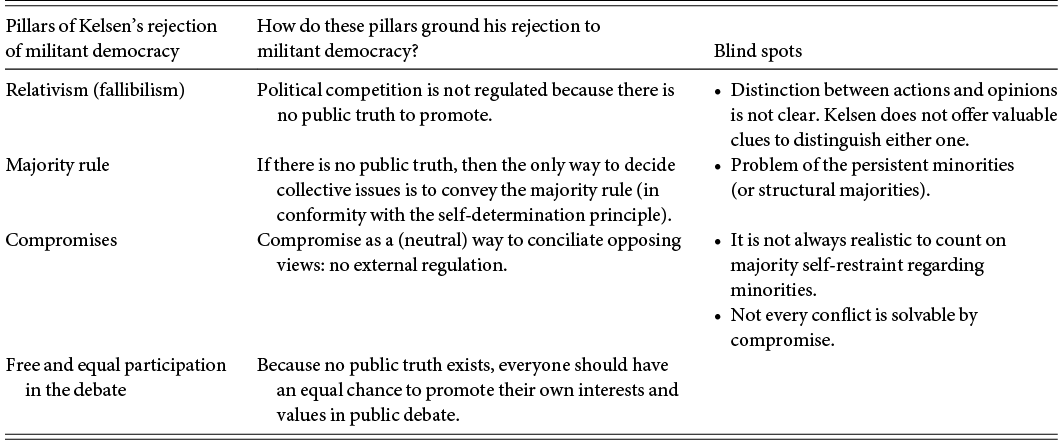

Table 13.1 lists and summarises what I call the four pillars of Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy. In addition, the table lists the unresolved issues linked to these four pillars, which could undermine the foundations of Kelsen’s refusal of militant democracy.

Table 13.1Long description

Table titled The four pillars of Kelsen’s critique of militant democracy outlining four elements: relativism, majority rule, compromises, and free and equal participation. Middle column explains how each pillar supports Kelsen's critique through stress on absence of public truth, reliance on majority decisions, neutral conciliation, and equal access to debate. Right column lists blind spots including unclear action-opinion line, persistent minority issues, unrealistic expectations about majority restraint, and conflicts not resolvable through compromise.

13.3 Kelsen’s Sparse Legacy

In this second section, I reassess the assumption that Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy does not have any supporters today. Indeed, the idea that Kelsen has practically no current ‘supporters’ is widespread:

In this recent literature, consensus has emerged on the fundamental principle underlying the theory and practice of militant democracy: Democracies have a right (some say a duty […])Footnote 93 to limit fundamental rights of free expression and participation – albeit with various qualifications and caveats – for reasons of self-preservation. Gustav Radbruch’s and Hans Kelsen’s value-neutral model of pluralist democracy,Footnote 94 according to which all political positions should be given equal rights of expression and participation – and that according to many (including Loewenstein) doomed the Weimar Republic – has virtually no supporters today.Footnote 95

By contrast, the Kelsenian value-neutral model does indeed have a few adherents today. Here, I focus in greater depth on political theorists who have endorsed Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy. Among this scant group, Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 96 followed Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy for three main reasons. Kelsen did not express these grounds in the same terms as these authors do, and for at least one of these grounds, their reasoning exceeds Kelsen’s theoretical arguments.

First, Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 97 consider – with some Kelsenian nuance – that the principle of self-determination (i.e., that which characterises a democratic regime) necessarily entails political risk for our democracies:

If democracy is to be understood as a form of government based on the principle of freedom as collective self-government, this suggests that it must inevitably be willing to assume a certain measure of political risk […]. Of course, this does not mean that all democratic orders are equally risky, or that there is nothing democracy can do to make itself more secure. But at the very least, the medicine must not be more dangerous than the infirmity. Militant democracy fails this test.

On that point, Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman echo Kelsen’s position. Indeed, for the Austrian jurist, even when democracy goes through turbulence, the temptation to resort to nondemocratic methods must be resisted to preserve democratic institutions:

Popular sovereignty cannot subsist against the people. And it should not even attempt to, that is, whoever supports democracy must not get entangled in the disastrous contradiction of resorting to dictatorship to save democracy. One has to remain faithful to one’s flag, even when the ship is sinking; and while reaching the bottom, keep the hope that the idea of liberty is indestructible and that the lower it has sunk, the more passionately it will resurrect.Footnote 98

Taking this political risk implies a guarantee, a ‘right to do wrong’Footnote 99 and the right to ‘seek morally suspect ends’.Footnote 100 If this ‘right to do wrong’ is not guaranteed, then the principle of self-determination is somehow called into question.

The Kelsenian corpus most directly inspires this argument. Accepting such a political risk here is related, according to Kelsen, to the primacy of the self-determination principle (defining democracy itself), which considers any interventions in the democratic game as proceeding from autocratic methods and therefore incompatible with democratic principles. Admittedly, this argument is very robust and the most difficult to challenge. Jan-Werner Müller argues that the angle from which Kelsen rejects militant democracy – which Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 101 endorse – is convincing and should inspire the camp of ‘sceptics about the very idea of militant democracy’,Footnote 102 to which Müller himself does not belong:

Here the thought is that the very attempt to defend democracy will damage democracy: Governments will fight their enemies until they become like their enemies; they might think that they have held on to democracy, but they actually destroyed it in the process of securing it (which was essentially Kelsen’s core objection to anything resembling militant democracy). This seems more like a genuine paradox. Skeptics about the very idea of militant democracy might be well advised to start their critique right here, at the most fundamental level, just as Kelsen did. They might say that challenges to democracy would in almost all cases resolve themselves through the regular political process; if they do not, then no special political and legal measures will be able to stop a slide into authoritarianism. Hence any attempts to defend the supposed substance of democracy are likely to be counterproductive.Footnote 103

This first line of argument, which adheres to the sanctity of the principle of self-determination, maintains that no ‘militant democracy’ measure can be justified by the continuity and viability of our democracies. Such a perspective closes the door to consequentialist perspectives that focus on the benefits and costs of militant democracy. Indeed, Kelsen never argued against militant democracy by considering the impact of such measures on democratic institutions or their vitality.Footnote 104

Second, Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 105 point out that drawing a dividing line between enemies and friends of democracy – to exclude the former – coincides with ‘an irreducible element of arbitrariness’. Ultimately, how should one settle the boundaries between enemies and friends of democracy? According to Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman,Footnote 106 such a ‘decision over the boundaries of the political community itself cannot coherently be taken by democratic procedures and therefore cannot be subsumed under any prior norm’. The argument according to which militant democracy would necessarily imply arbitrariness in designating ostracised groups is not explicitly present in Kelsen’s argumentation but is indeed close to his ‘relativist’ statement. If ‘only relative values are accessible to human knowledge and human will’,Footnote 107 then consequently, an incontestable method that is able to delineate accepted and ostracised voices or groups does not exist. Nonmajoritarian choices imposed on the collective imply a certain degree of arbitrariness. Therefore, Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 108 follow Kelsen’s line here, although the notion of relativism does not emerge in their article. I assume that the reference to ‘relativism’ is possibly taboo – or at least very difficult to handle – for those currently tending to reject militant democracy. Indeed, relativism became highly unpopular after 1945. Le BouëdecFootnote 109 describes the quasi-consensus that emerged after the Second World War about the negative impact of relativism on the stability of our democracies:

If there is one idea that has gained consensus in the post-war period, it is that the absolute ‘neutrality’ of the Weimar Constitution and its inability to defend itself against its enemies led to its ‘suicide’. Relativism appears to be the philosophical basis for a formalistic, not normative, conception of democracy, which leads to the constitution being placed entirely at the disposal of the majority. Together with Hans Kelsen, Radbruch was considered the main representative of this relativism. Under Weimar, he had affirmed (like the Austrian jurist) that relativism was the presupposition of the democratic idea, explaining that the spirit of the constitution was summed up in the formal principles of majority decision-making and tolerance.

In 1934, Radbruch, unlike Kelsen, changed his position slightly but significantly. He affirmed that ‘a democratic state should certainly tolerate every opinion, but not the ones that claim to be absolute and the ones that do not respect the rules of the democratic game’.Footnote 110 Thirty years later, Kurt Sontheimer, in his Habilitation thesis, Antidemokratisches Denken in der Weimarer Republik [Antidemocratic Thinking in the Weimar Republic],Footnote 111 held relativism responsible for bringing about the capitulation of German democracy.Footnote 112

I challenge Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman’sFootnote 113 idea that a ‘decision over the boundaries of the political community itself […] cannot coherently be taken by democratic procedures and therefore cannot be subsumed under any prior norm’. In fact, democratic procedures can help to define the limits of what is legitimate in a democratic public debate. For example, in the February 2020 Swiss referendum, the majority of voters came out in favour of extending current antiracism legislation that would make it illegal to discriminate against people based on their sexual orientation.Footnote 114 This outcome proves that democratic procedures are capable of drawing a line between acceptable discourses compatible with a democratic worldview and nonacceptable ones and of excluding voices that diffuse such messages.

Third, according to Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman, militant democracy could actually be used against its main goal (i.e., protecting democracy) to exclude political actors who do not threaten democracy but who are only political rivals on the path of empowered political groups. Thus, militant democracy would

provide a means for those empowered to make the relevant decisions to arbitrarily exclude an indeterminately expansive range of political competitors from the democratic game, thereby restricting the democratic nature of the regime and therefore effectively ‘doing the work of the enemies of democracy for them’.Footnote 115

This type of objection – consequentialist in nature – must be taken seriously. We can never rule out the concept of ‘militant democracy’ being used for purposes other than protecting our democratic institutions. Ultimately, there is a trade-off between two distinct risks. On the one hand, in a context of nonregulation (hostile to militant democracy), there are parties that exploit their situation to promote nondemocratic goals; on the other hand, in a context where the militant democracy principle is accepted, groups exploit their position to arbitrarily exclude those political groups challenging hegemonic groups. Given how the principle of militant democracy has been used and the fact that its targets have been diverse and not always fully justified, there are reasons to believe that its use could be arbitrary. Notably, extreme right-wing parties have not been the only targets of militant democracy. Far-left parties have also been targeted. In this respect, the Berufsverbot, as implemented in West Germany, which allows for the professional disqualification of civil servants with affinities for the extreme left,Footnote 116 is an example of a variant use of militant democracy that is not unambiguously about protecting democratic institutions. Although the authors are not this explicit, we could mobilise here the reflections of Malkopoulou and NormanFootnote 117 and Stahl and Popp-Madsen,Footnote 118 who denounce the inherently elitist and undemocratic character of theories of militant democracy for showing a certain distrust of citizen participation. In this regard, Stahl and Popp-MadsenFootnote 119 propose a ‘popular model’ of democratic self-defence based on ‘republican and socialist imaginaries’. Ultimately, the safeguarding of democracy is a question of arbitrating between two very real risks: that of giving in to anti-democratic movements without resistance and that of providing groups with instruments of militant democracy whose use is contrary to its objectives. This balancing act explains the ambivalence surrounding the principle of militant democracy. The arbitration between these risks, consequentialist in nature, is not addressed by Kelsen, who emphasises the principled incompatibilities between self-determination and militant democracy: there is no a priori democratic justification for excluding voices or parties, regardless of the consequences of compliance with this principle.

Except for Invernizzi Accetti and Zuckerman,Footnote 120 it is not easy to find contemporary authors who have endorsed Kelsen’s perspective on militant democracy. Malkopoulou and NormanFootnote 121 have attempted to thicken Kelsen’s affiliation because the Austrian jurist was also a source of inspiration for Rosenblum, who would have added

a post-Kelsenian twist to the liberal-democratic paradigm by arguing that political inclusion will temper extremism and gradually socialise its proponents into democrats, as they are increasingly prompted to play according to the rules of the democratic game. Participating in regulated rivalry will force once radical political actors to become more moderate. The core idea is that ‘electoral political competition, like any strong institutional practice, is formative’.Footnote 122

This formative aspect, which, according to Rosenblum,Footnote 123 goes with a certain ‘faith in politics’, is also presupposed by several scholars in the empirical literature, such as Van Spanje and Van der Brug.Footnote 124 The latter have highlighted the impact of inclusion on excluded parties. Including extremist parties would better promote the ‘democratic spirit’ than banning or ostracising them.

However, to what extent does the formative moderating effect – which goes hand in hand with the integration of antisystem political parties – belong to a Kelsenian legacy? In my opinion, the Austrian jurist does not address such a pedagogical aspect. Kelsen would probably be sceptical of what RosenblumFootnote 125 calls ‘democratic acculturation’. The element of moderation works for Kelsen essentially through compromises, as demonstrated above. In his works, Kelsen argues that regular political processes must resolve political divergences and conflicts of interest (possibly of values) and that compromises occupy a significant place among these ‘natural’ processes. The naturalness of compromises or the ‘tendency towards compromise’Footnote 126 in democracies, as Kelsen assumes, does not include a formative aspect among political rivals. Notably, belief in the naturalness of democratic compromises or the ‘tendency towards compromise’Footnote 127 among democracies is no less optimistic than the pedagogical aspect that Rosenblum assumed and exposed earlier.

13.4 Conclusion

Kelsen’s indictment of the principle of militant democracy is rarely used, not because he rejects it outright but because his arguments are unique in two respects. If Kelsen has few followers, it is first because he developed his rejection of militant democracy exclusively on the basis of its principles and not in relation to its democratic implications. The principle of militant democracy is assessed in terms of its (in)compatibility with the principle of self-determination. Such a perspective appears only in the minority in contemporary literature. Since the early 2000s, there has been a burgeoning body of work examining the desirability of militant democracy in terms of its consequences or costs. In particular, a key question is focused on the extent to which the exclusion of anti-establishment or extremist parties is appropriate in light of its consequences for the radicalisation of political profiles and their democratic acculturation.Footnote 128 Such a perspective – assessing the costs and benefits of militant democracy – is by no means Kelsenian. Among the few contemporary authors who have advocated a principled rejection of militant democracy, Invernizzi Accetti and ZuckermanFootnote 129 have been discussed at length in this chapter. Their argument partially overlaps with the Kelsenian position, particularly on the points of friction between the principle of self-determination and the restriction of political competition. Malkopoulou and NormanFootnote 130 also look to Kelsen’s principled position to support their rejection of militant democracy as elitist.Footnote 131 In their view, the liberal model of militant democracy demonstrates a ‘deep-seated mistrust of the people’s ability to govern themselves’.Footnote 132

Second, Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy is ultimately based on the principle of relativism, which is still a very little-used perspective in this debate. The authors who express serious doubts about militant democracy do not use this concept. Since the Second World War, relativism has been associated with a formalist conception of democracy that offers no resistance to democratic suicide. Moreover, the difficulties of drawing a clear line between discourse and action (to confine relativism to the former) may ultimately support the rejection of relativism as a normative basis for undermining militant democracy. However, despite the fractures in the pillars upholding Kelsen’s rejection of militant democracy, I believe that he must continue to be mobilised in current debates: Kelsen raises an essential question, namely, that of the limits of what our democracies can undertake to protect themselves without denaturing themselves.