Introduction

In spoken communication, second language (L2) learners often face challenges in achieving native-like fluency. Those with lower proficiency, constrained by limited language exposure, tend to produce fragmented speech marked by frequent pauses (Pawley & Syder, Reference Pawley, Syder, Richards and Schmidt1983; Wray, Reference Wray2002). This challenge may arise from obstacles in storing large, chunked phrases or sentences in long-term memory (Arnon & Christiansen, Reference Arnon and Christiansen2017; Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Kato, Baese-Berk and Vaughn2024). In contrast, adult first language (L1) speakers typically demonstrate fluent speech, supported by extensive language experience. Real-time speech fluency is constrained by the limited capacity of working memory, estimated as 7 ± 2 items (Miller, Reference Miller1956) or 4 ± 1 chunks (Cowan, Reference Cowan2001). However, L1 speakers can surpass these limitations by relying on the storage and retrieval of large chunks. This chunking ability, which involves combining smaller language elements into larger, meaningful units, is fundamental to fluent speech production. Taking L1 speakers as a baseline, the present study investigates key differences in chunking ability between L2 learners and L1 speakers, and examines how L2 learners develop native-like chunking ability through increased proficiency or repeated practice.

The theory of chunking by Baddeley’s working memory model

The original model of working memory by Baddeley and Hitch (Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Bower1974) consisted of the following three components: a central executive acting as an attentional control system, a phonological loop that holds auditory or verbal information, and a visuo-spatial sketchpad associated with visual or spatial information. Later, Baddeley (Reference Baddeley2000) added the episodic buffer, as a temporary storage of chunks, to his earlier three-component working memory model, providing an interface between working memory and long-term memory. Within this framework, evaluating the occurrence of the chunking process requires considering the involvement of attention. A fundamental question arises about whether the chunking process itself or the retrieval of chunked units from the buffer during immediate memory requires attentional resources governed by the central executive (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley2000, Reference Baddeley2007, Reference Baddeley, Wen, Mota and McNeill2015).

To address this question, Baddeley and colleagues conducted a series of empirical studies in the auditory or verbal domains. Participants performed immediate recall tasks in which they recalled auditorily presented unrelated words or meaningful sentences while simultaneously engaging in a demanding secondary task, such as back counting, intended to disrupt the central executive and phonological loop components of working memory. Results demonstrated enhanced recall for meaningful sentences over unrelated word lists (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018; Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009), as well as for coherent stories over sequences of unrelated sentences (Jefferies et al., Reference Jefferies, Ralph and Baddeley2004). These findings suggest that chunking reduces working memory load by enabling multiple elements to be encoded and retrieved as a single unit, thus enhancing recall performance even under dual-task conditions. For instance, when recalling a sentence like Planets travel around the sun in a recall task, syntactic and semantic support from long-term memory enables individual words to be bound together into a meaningful chunk. In sum, it is well established that meaningful phrases or sentences are processed as unitary chunks by L1 speakers, requiring minimal attentional resources (e.g., Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018; Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009; Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2009; Isbilen et al., Reference Isbilen, McCauley and Christiansen2022).

Moreover, the model suggests that retrieving chunked sentences from the episodic buffer during recall requires attentional resources, as the buffer is controlled by the central executive system. The buffer is believed to have a capacity of three to five unrelated chunks (Cowan, Reference Cowan2001), indicating that divided attention caused by concurrent tasks could reduce this capacity. However, due to the lack of direct measurements on the number of chunks retained in immediate memory, Baddeley and colleagues have not been able to empirically validate this hypothesis.

Finally, several studies have shown that individual differences in working memory capacity can predict sentence recall performance (Acha et al., Reference Acha, Agirregoikoa, Barreto and Arranz2021), listening comprehension (Satori, Reference Satori2021), and overall language proficiency (Linck et al., Reference Linck, Osthus, Koeth and Bunting2014). Nonetheless, it remains unknown whether learners with higher working memory capacity are able to retain more chunks in the episodic buffer in both L1 and L2 learning contexts.

Chunking in L2 speech production

When examining L2 learners, a critical question arises as to whether they process phrases or sentences as unitary chunks or instead rely on multiple, smaller chunks. According to the Unified Competition Model proposed by MacWhinney (Reference MacWhinney, Robinson and Ellis2008, Reference MacWhinney, Hickmann and Kail2017), L2 learners tend to over-analyze utterances grammatically or semantically into smaller segments. However, this risk factor for fluency can be mitigated by the process of chunking, one of the protective factors during L2 learning, which fosters proceduralization and reduces demands on attentional resources during speech production. Many studies have demonstrated that low-proficiency L2 learners often fail to acquire sufficiently large chunks (Arnon & Christiansen, Reference Arnon and Christiansen2017; McCauley & Christiansen, Reference McCauley and Christiansen2017; Pawley & Syder, Reference Pawley, Syder, Richards and Schmidt1983). As proficiency increases, the binding of individual words gradually becomes proceduralized, requiring fewer attentional resources and enhancing fluency (Morgan-Short et al., Reference Morgan-Short, Sanz, Steinhauer and Ullman2010). Although these studies suggest that chunking contributes to improved fluency, empirical research on the role of attentional resources in L2 learning within Baddeley’s working memory framework remains limited, leaving the mechanisms of working memory and long-term memory in L2 chunking insufficiently understood (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley, Wen, Mota and McNeill2015, Reference Baddeley2017).

Methodologically, Declerck and Kormos (Reference Declerck and Kormos2012) as well as Albarqi and Tavakoli (Reference Albarqi and Tavakoli2023) employed single- and dual-task paradigms to explore how attention disruption from concurrent tasks impacts L2 speech production. Their findings indicate that such disruptions significantly impair both accuracy and fluency in L2 performance. However, neither study explicitly examined how attentional demands interact with chunking processes, thereby limiting our understanding of the chunking mechanisms underlying L2 fluency.

Repeated practice has been identified as a driving force in investigating the development of chunking over time (Ellis, Reference Ellis2017; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Hickmann and Kail2017). Frequent repetition strengthens associations between individual words, which eventually consolidate into proceduralized chunks stored in long-term memory. Notably, Ellis and Sinclair (Reference Ellis and Sinclair1996) found that rehearsing second language utterances, compared to silent reading or articulatory suppression, significantly improved both accuracy and fluency. However, their studies did not explicitly examine the concept of chunking. Future research should first define what constitutes a chunk (Gilchrist, Reference Gilchrist2015) and then investigate whether repeated practice influences the storage or retrieval of chunks in immediate memory.

Multi-word expressions in L1 and L2 processing

Sentences used in previous studies enable the chunking of individual words through syntactic and semantic integration (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018; Ellis & Sinclair, Reference Ellis and Sinclair1996; Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2009). However, the associations between words in sentences are often relatively loose. In contrast, multi-word expressions (MWEs) show significantly higher frequency and mutual information (MI), indicating stronger associations among their constituent words. This formulaic nature of MWEs (Wray, Reference Wray2002) offers a distinct advantage for more effective chunking.

Current research on MWEs primarily investigates whether they have a processing advantage over non-formulaic counterparts (e.g., “to tell the truth,” vs. “to tell the price”) in both L1 and L2 processing (Yi & Zhong, Reference Yi and Zhong2024; Zheng et al.,Reference Zheng, Bowles and Packard2022). This advantage has been consistently demonstrated across various tasks and measures, with MWEs eliciting faster responses in plausibility judgment tasks compared to non-MWEs (e.g., N. Jiang & Nekrasova, Reference Jiang and Nekrasova2007). Additionally, MWEs are associated with shorter fixation times in eye-tracking studies (e.g., S. Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jiang and Siyanova-Chanturia2020; Yi et al., Reference Yi, Lu and Ma2017) and reduced articulation times in speech production (Bannard & Matthews, Reference Bannard and Matthews2008). Numerous studies have also emphasized the important role of MWE frequency in both L1 and L2 comprehension and production (Supasiraprapa, Reference Supasiraprapa2019). Together, these findings on the processing advantage of MWEs could be attributed to their nature as pre-fabricated, memorized units that are stored and retrieved holistically, rather than being assembled word by word. However, what remains underexplored is how this advantage relates to the theory of chunking, particularly the role of attentional resources and how MWE formulaicity influences chunking ability during speech production in both L1 and L2 speakers.

The present study

Using L1 speakers as a baseline, this study investigates the chunking ability of L2 learners of Chinese in processing MWEs and further examines how language proficiency and repeated practice through training contribute to enhanced chunking. Two experiments were conducted using immediate recall under both single-task and dual-task conditions. Recall performance was assessed using two measures: chunk size, which reflects chunking ability by capturing the binding between an MWE’s constituents, and the number of chunks recalled, which reflects the retrieval of chunks from working memory.

Experiment 1 investigates whether divided attention affects the chunking of MWEs in both L2 learners and L1 speakers. We predict that divided attention induced by dual tasks will reduce the number of chunks recalled in immediate memory across both groups. However, we expect that it will not disrupt the formation of unitary chunks for MWEs in L1 speakers, who are assumed to store MWEs as holistic chunks in long-term memory. In contrast, due to more limited language exposure, L2 learners may be more vulnerable to attentional disruption, resulting in fragmented representations of MWEs. Thus, we hypothesize that L1 speakers will recall MWEs as unitary chunks, whereas L2 learners will tend to recall them as multiple, smaller chunks. Furthermore, we examine whether chunk size and the number of chunks correlate with individual differences in language proficiency and working memory capacity. Specifically, we expect chunk size to correlate with language proficiency but not working memory capacity, and the number of chunks to correlate with working memory capacity but not language proficiency. Experiment 2 explores whether repeated practice with MWEs facilitates chunking ability by L2 learners. We predict that repeated practice will lead to improved recall of larger chunks, rather than increasing the total number of chunks recalled.

Experiment 1

Methods

Participants

Thirty-two L2 learners of Chinese (17 males, 15 females) and 32 Chinese L1 speakers (15 males, 17 females) took part in this experiment. All participants were undergraduate or graduate students, aged between 18 and 33, with L2 learners averaging 22.2 years and L1 speakers averaging 23.6 years. All participants had normal hearing and either normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The L2 learners were native English speakers who began learning Chinese as a second language after the age of 16. They were enrolled in a Chinese language learning program at the Beijing Language and Culture University or Peking University, with an average exposure of 32 months to the Chinese language. The authors confirm that all procedures adhered to the ethical standards set by the Ethics Committee of Language Acquisition and Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at the Beijing Language and Culture University regarding human experimentation and aligned with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Participants in the experiments provided signed consent forms and were compensated for their involvement.

Materials

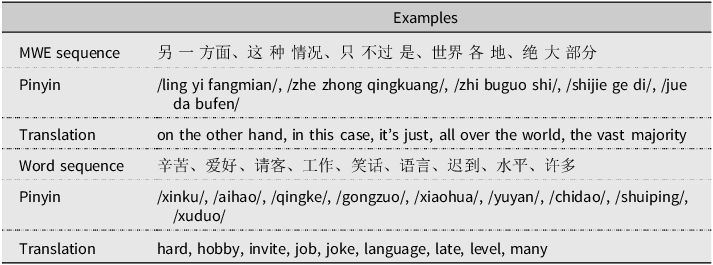

Two types of sequences were used in the experiment (see Table 1 for examples): one consisting of five unrelated MWEs (hereafter, MWE sequence) and the other consisting of nine unrelated words (hereafter, word sequences). The full list of materials can be found in Table S1 and Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials. Following previous research, the number of MWEs (Cowan, Reference Cowan2001) or unrelated words (Miller, Reference Miller1956; Simon, Reference Simon1974) in each sequence was determined based on the maximum span of immediate recall: the “magic number 4 ± 1 for chunks” and the “magic number 7 ± 2” for single words. This approach aimed to ensure that the L1 group could recall most of the content in each sequence, thus minimizing ceiling or floor effects and keeping recall within an optimal range. We selected three-word MWEs containing four syllables, as such MWEs have been identified as fundamental building blocks in both L1 and L2 learning (Arnon & Christiansen, Reference Arnon and Christiansen2017). To control for potential confounding variables, we ensured that each MWE contained the same number of words. The MWEs were sourced from Chinese language textbooks, language proficiency test syllabus (e.g., New HSK Chinese Proficiency Test Syllabus 6), and academic publications (e.g., Hsu, Reference Hsu2016).

Table 1. Examples of MWE sequence and word sequence used in experiment 1

Note. Pinyin indicates the phonetic transcription of the Chinese words. Words within MWEs are separated by spaces. MWE = multi-word expression.

The MWEs comprise a total of 153 distinct words, primarily categorized as Level 4 or 5 according to the New HSK Chinese Proficiency Test Syllabus 6 Confucius Institute Headquarters (2009) with Level 4 words representing 88.2% of the total. To assess participants’ familiarity with these words, we utilized the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale (VKS) adapted from Wesche and Paribakht (Reference Wesche and Paribakht1996). The VKS spans four levels: 1 = I don’t remember having seen this word before; 2 = I have seen this word before, but I don’t know what it means; 3 = I have seen this word before, and I think it means… (Chinese synonym or English translation); 4 = I know this word, and it means… (Chinese synonym or English translation). L2 learners completed the VKS in paper-and-pencil format several days before the experiment. If participants marked level 3 or 4 but provided an incorrect meaning, they received a score of 2. The cumulative scores for all words were summed and converted to percentages. The results showed an average score of 87.9% (SD = 8.8%), reflecting a robust grasp of these words among L2 learners. Based upon this, our study aims to explore the chunking ability of L2 learners in assembling these familiar words into coherent phrases.

To facilitate chunking, we selected MWEs that appeared more than three times per million words and had an MI threshold exceeding threeFootnote 1 (e.g., Wei & Li, Reference Wei and Li2013). The meanings of all MWEs could be transparently derived from the meanings of their constituent words. The transparency of MWEs was assessed by four linguistic experts on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = transparent, 6 = opaque) based on their linguistic expertise and intuitive language sense. Only MWEs that received an average score below three were included in the experiment, ensuring that the focus remained on the chunking process involving semantically transparent word combinations, avoiding any interference from metaphorical or opaque meanings (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Niu, Taft and Carreiras2023).

A total of 120 MWEs were selected for the experiment, all of which adhered to the criteria outlined above for frequency, MI, and transparency. These MWEs were randomly assigned to 24 sequences, each containing five MWEs. The 24 sequences were further randomized into three sets, with each set comprising eight sequences. To prevent repetition of words within a set, adjustments were made by exchanging MWEs between sets as needed. For instance, if “世界第一” (/shijie di yi/, “world first”) and “世界各地” (/shijie ge di/, “all over the world”) appeared within the same set, “世界各地” would be reassigned to another set. Importantly, no semantic or syntactic associations were present between consecutive MWEs within each sequence. One-way ANOVA results showed no significant differences in MWE frequency across the three sets, F(2,119) = 0.027, p = .974, or MI, F(2,119) = 0.323, p = .724. The average frequency for the three sets was 20.9, 21.2, and 22.4 per million words, and the average MI was 4.1, 4.0, and 3.8, respectively.

Regarding the word sequences, a total of 108 disyllabic words were selected from Level 4 of the New HSK Chinese Proficiency Test Syllabus 6, excluding those used in the MWE sequences. This ensured that the word sequences and MWE sequences were distinct, avoiding interference during recall. The words were then randomly assigned to 12 sequences, each containing nine words. These sequences were further grouped into three sets, with four sequences per set. To prevent potential semantic and syntactic associations between adjacent words within a sequence, the word order was carefully adjusted. The VKS results showed an average score of 91.6% (SD = 9.4%), indicating participants are very familiar with these words. One-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in word frequency across the three sets, F(2,107) = 0.222, p = .801. The average frequency for the sets was 317, 261, and 310 per million words, respectively.

The auditory stimuli were generated through the following steps. Initially, a male native Chinese speaker pronounced each word in the MWE sequence or each syllable in word sequences, with the pronunciations recorded using Praat 6.0.18 (https://www.praat.org). Subsequently, the individually recorded words or syllables were sequentially arranged to create the final stimuli. This method avoided potential cues from intonation and co-articulation between adjacent words or syllables in continuous speech. MWE sequences, each consisting of 15 words, were delivered at a pace of one word per second, resulting in a total duration of 15 seconds per sequence. Word sequences, containing 18 syllables, were presented at a rate of one syllable every 0.75 seconds, with each sequence lasting 13.5 seconds. We ensured that both sequence types were created to be approximately equal in duration.

Procedure

Participants were seated in front of a laptop in a quiet laboratory and conducted the experiment using E-prime 2.0. The experiment employed an immediate serial recall task, widely recognized as a reliable measure of the chunking process (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley, Wen, Mota and McNeill2015; Culbertson et al., Reference Culbertson, Andersen and Christiansen2020). Participants first completed MWE sequences, followed by the word sequences. Each trial began with a beep, signaling the start of the sequence, followed by the audio presentation. A second beep marked the end of the sequence, after which participants were required to recall what they heard in serial order. Before beginning the trials, participants received instructions about the nature of the sequences. For MWE sequences, they were informed that every three consecutive words they heard could be assembled into a coherent phrase. For word sequences, participants were told that every two consecutive syllables could combine to form a disyllabic word. Given that the sequence length exceeds the typical capacity of working memory, this explicit instruction was intended to encourage both L1 speakers and L2 learners to rely on long-term memory during encoding, facilitating the chunking of individual elements into larger, meaningful units, particularly under conditions of high cognitive load. Participants were given 15 seconds to provide oral responses for MWE sequences and 13.5 seconds for word sequences. If they completed their recall before the time expired, they could press the spacebar to proceed to the next sequence. The entire experimental process was recorded using Praat.

During each auditory presentation phase that preceded the recall, either a single-task or a dual-task condition was administered. In the single-task condition, participants listened to the audio without additional tasks or distractions. In the dual-task condition, participants concurrently performed a back-counting task while listening to the audio. This task began with a random two-digit number greater than 30 displayed on the screen one second before the audio began. Participants were instructed to count backward aloud by threes (e.g., 82, 79, 76…) at a pace of one number every two seconds until the audio ended. They were asked to maintain a moderate speaking volume that would not interfere with their ability to hear the audio. An experimenter monitored their counting to ensure consistent pacing. Chinese L1 speakers completed the counting task in Chinese, whereas L2 learners of Chinese performed it in English. The back-counting task is designed to impose a significant cognitive load by disrupting both the phonological loop and the central executive more than simpler articulatory suppression tasks, such as just repeating a single number word continuously. The single- and dual-task paradigm has been validated in previous studies as a reliable method for assessing attentional resource consumption and proceduralization processes (e.g., Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009; Jefferies et al., Reference Jefferies, Ralph and Baddeley2004).

The three sets of MWE sequences and three sets of word sequences, as described in the materials, were utilized for the single-task and dual-task conditions, along with a delayed-task condition, which was designed for a separate study. The sets were counterbalanced across participants using a Latin square design, with each set serving as a single block. Within each block, sequences were presented randomly. Participants completed one block under the single-task condition and another block under the dual-task condition. The total experiment lasted approximately 12 minutes.

In addition, listening and speaking proficiency were assessed using the global scale outlined in The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment Council of Europe (2001). This scale (see the scale in the Supplementary Materials) classifies proficiency into six levels: A1 (lowest), A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2 (highest). Based on the proficiency descriptions for each level, L2 learners self-assessed their abilities in listening, spoken interaction, and spoken production separately. These levels were then converted into a six-point scale for analysis. The three scores were averaged, yielding a mean of 2.906 (SD = 0.963).

Finally, participants’ working memory capacity was assessed using an adapted version of the word span task introduced by Salthouse and Babcock (Reference Salthouse and Babcock1991). This task has shown a strong correlation with L2 learning outcomes (e.g., Linck et al., Reference Linck, Osthus, Koeth and Bunting2014). Both L1 speakers and L2 learners were tested in their respective L1 to ensure familiarity with the test words, thereby providing a reliable index of their working memory capacity. All test words, in Chinese or English, were disyllabic and matched for frequency (Chinese: 125 occurrences per million words according to the BCC; English: 113 occurrences per million words according to the Corpus of Contemporary American English, COCA, https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/). The task included six types of random word sequences, ranging from four-word to nine-word sequences, with each type containing three sequences. Words were presented auditorily at a rate of one word per second. Participants were required to repeat the words in the correct order within the same duration as the sequence presentation (e.g., four seconds for a four-word sequence). Correct recall of all words in the exact order was marked as correct for a specific sequence. The experiment began with four-word sequences and continued until participants failed to correctly recall at least two of the three sequences for a specific sequence type. Working memory capacity was determined by the maximum number of words correctly recalled before termination. The results indicated an average working memory capacity of 5.00 words (SD = 0.57) for L1 speakers and 5.39 words (SD = 1.04) for L2 learners.

Statistical analysis

Following the methodology outlined by Gilchrist et al. (Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2008) and Gilchrist et al. (Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2009), two measurements were employed: item completion and item access. Here, the term “item” refers to either an MWE or a word.

For MWE sequences, item completion is defined as the proportion of words recalled in correct serial order within a given MWE, provided that at least one content word (i.e., noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, number, and measure word) was recalled. For example, if a participant recalled two words (e.g., “绝” and “大,” “the vast”) of a three-word MWE (e.g., “绝大部分,” “the vast majority”), the MWE completion would be calculated as 1/3 + 1/3 = 0.667. For disyllabic words, recalling only one syllable is counted as half of the one-third score assigned to the entire word. This approach ensures a granular assessment of MWE completion, capturing instances where participants access part of a word but fail to retrieve it entirely. For word sequences, item completion is the proportion of syllables recalled in serial order within a disyllabic word, provided that at least one syllable was recalled. If none of the internal words or syllables within an MWE or a word are recalled, they are excluded from the calculation of item completion, ensuring that MWE completion accurately reflects the size of the recalled chunk. When evaluating order, only the sequence of words or syllables within each MWE or word is considered. For instance, if an MWE like ABC is recalled as AB, BC, or AC, these are regarded as correctly ordered and recorded as two words recalled. Conversely, if it was recalled as CB, BA, or CA, or interrupted as ADB, these are considered incorrectly ordered, and only one word is recorded as recalled. Additionally, when a word is replaced with a semantically related word (e.g., “the vast majority” recalled as “the large majority, 很大多数”), it was deemed correct as it reflects equivalent chunking ability during the recall process.

For MWE sequences, item access refers to the proportion of MWEs in which at least one content word was accessed within a sequence, out of the total number of MWEs presented (i.e., five MWEs). For example, in an MWE sequence like “另一方面、这种情况、只不过是、世界各地、绝大部分” (“on the other hand, in this case, it’s just, all over the world, the vast majority”), if participants recall two full MWEs, such as “这种情况” and “绝大部分”, and one content word, “世界” (“world”), the MWE access would be calculated as 3/5 = 0.600. While we acknowledge that recalling a single content word is not equivalent to recalling a full three-word phrase, measuring the number of MWEs accessed per sequence assumes that both a complete MWE and a content word from it can be considered part of the same chunk in working memory (Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2008, Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2009). Recalling a specific content word from a given MWE implies a certain level of access to an individual chunk in memory. Although these two cases are not identical, prior research has empirically treated both as valid indicators of accessing a specific chunk in memory. For word sequences, item access is defined as the proportion of words in which at least one syllable was accessed within a sequence, out of the total number of words presented (i.e., nine words).

Overall, item completion assesses the internal association strength between the constituents of an item, which indirectly reflects chunk size (Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2008, Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2009). This approach helps address the challenge of precisely defining chunks. Additionally, item access quantifies the number of chunks recalled, serving as an indicator of working memory capacity. Analyzing both item completion and item access together offers a more comprehensive understanding of recall performance, as it addresses both chunk size and the number of chunks separately.

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22). Two separate repeated-measures by-participant ANOVAs (F1) were conducted,Footnote 2 using item completion and item access as dependent variables within a 2 (Speaker: L1 speakers, L2 learners) × 2 (Item: MWEs, words) × 2 (Task: single, dual) design. Both dependent variables were logarithmically transformed before running the ANOVAs, with the original values being reported in the text. Additionally, by-item ANOVAs (F2) were conducted. Since the patterns observed in the F2 results were analogous to those of the F1 results, the F2 findings are included in the Supplementary Materials. We reported significant main effects, two-way, and three-way interactions. For significant three-way interactions, simple main effects of Task were further reported for both MWE and word sequences, as well as for L1 speakers and L2 learners. A post hoc power analysis, with a significance level (α) set at .05, revealed that all significant main effects, three-way interactions, and simple main effects had a statistical power exceeding .999, except for the three-way interaction concerning item access (1–β = .531). This indicates that the sample size for the experiment is satisfactory.

Additionally, we conducted Pearson correlation analyses to examine the relationships between listening and speaking proficiency or working memory capacity and MWE completion or MWE access during immediate recall for both L1 speakers and L2 learners. Prior to the analysis, all measurements were logarithmically transformed.

Results

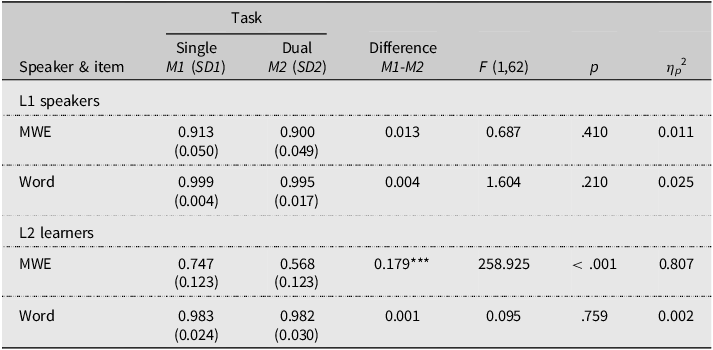

Item completion

The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Speaker, F(1,62) = 115.921, p < .001, η p 2 = .652, Item, F(1,62) = 249.320, p < .001, η p 2 = .801, and Task, F(1,62) = 145.185, p < .001, η p 2 = .701. More notably, a significant three-way interaction among Speaker, Item, and Task was found, F(1,62) = 112.970, p < .001, η p 2 = .646. Further analysis of the simple main effects of Task for both Speakers and Items is summarized in Table 2. For L1 speakers, no significant task effect was observed for either MWE sequences or word sequences, suggesting that dual tasks did not interfere with the MWE completion or word completion. Conversely, for L2 learners, a significant task effect was observed for MWE sequences, indicating that L2 learners performed worse in MWE completion under the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition. The η p 2 value of 0.807 for this task effect is categorized as very large based on Cohen (Reference Cohen1988)’s guidelines. However, for disyllabic words in word sequences under the dual-task condition, both L1 speakers and L2 learners exhibited full word recall, showing no significant difference in word completion compared to the single-task condition.

Table 2. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), and ANOVA statistics of the MWE completion and word completion under the single task and dual tasks for L1 speakers and L2 learners

Note. MWE = multi-word expression. *** indicates p < .001.

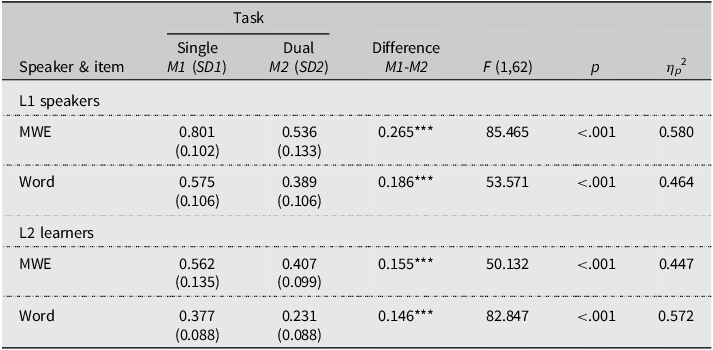

Item access

The uneven MWE completion among L2 learners poses challenges in establishing a reliable method for measuring MWE access. However, the absence of significant correlations between measures of MWE completion and MWE access suggests these measures are independent (all rs < 0.10, ps > .05), allowing both to be treated as valid dependent variables. The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Speaker, F(1,62) = 60.635, p < .001, η p 2 = .494, Item, F(1,62) = 182.619, p < .001, η p 2 = .747, and Task, F(1,62) = 234.853, p < .001, η p 2 = .791. More importantly, a significant three-way interaction was found across Speaker, Item, and Task, F(1,31) = 4.279, p = .043, η p 2 = .065. Further analysis of the simple main effects of Task for Speakers and Items is presented in Table 3. For both L1 speakers and L2 learners, all task effects for access in MWE and word sequences were significant. Specifically, both groups of speakers recalled more items for MWE sequences and word sequences during the single-task condition compared to the dual-task condition.

Table 3. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), and ANOVA statistics of the MWE access and word access under the single task and dual tasks for L1speakers and L2 learners

Note. MWE = multi-word expression. *** indicates p <.001.

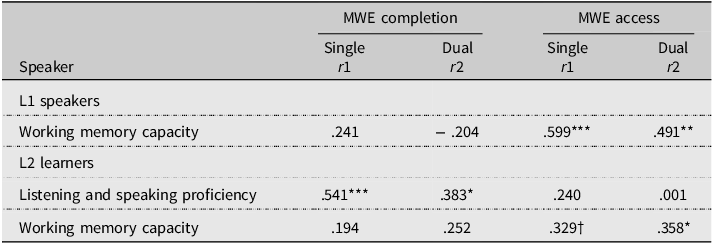

Correlation analysis

For L2 learners, Pearson correlation analysis showed that MWE completion was significantly associated with listening and speaking proficiency under both single-task and dual-task conditions (see Table 4). Conversely, no significant correlation was observed between MWE completion and working memory capacity for either L2 learners or L1 speakers. In contrast, MWE access under both single-task and dual-task conditions correlated significantly with working memory capacity for both L2 learners and L1 speakers. However, no significant correlation was observed between MWE access and listening and speaking proficiency for L2 learners.

Table 4. Correlation coefficients (r) between MWE completion/access and listening and speaking proficiency/working memory capacity under the single task and dual tasks for L1 speakers and L2 learners

Note. MWE = multi-word expression. *** indicates p < .001, ** indicates p < .01, * indicates p < .05, † indicates p < .1. Bold numbers indicate significance or marginally significance.

Discussion

For L1 speakers, no difference was observed in MWE completion between the single-task and dual-task conditions, suggesting that divided attention induced by dual tasks did not disrupt their ability to bind three constituent words into a complete and meaningful MWE. Consistent with previous findings (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018; Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009; Jefferies et al., Reference Jefferies, Ralph and Baddeley2004), our results indicate that the process of within-phrase chunking does not demand attentional resources during recall for L1 speakers. This is because three-word MWEs are stored as unitary chunks in the long-term memory of L1 speakers, rendering them resistant to interference from divided attention. The facilitation of within-phrase chunking is attributed to the semantic and syntactic associations inherent in meaningful phrases (Isbilen et al., Reference Isbilen, McCauley and Christiansen2022). Moreover, the formulaic nature of MWEs, characterized by their high frequency and MI values, further supports this facilitation. Consequently, the high formulaicity contributes to a notably higher MWE completion rate under the single-task condition in our study (91.3%) compared to sentence completion rates reported in prior studies involving adult L1 speakers: 81% for four four-word sentences and 71% for four nine-word sentences (Gilchrist et al., Reference Gilchrist, Cowan and Naveh-Benjamin2008), and approximately 70% for 15-word sentences (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018).

MWE completion for L2 learners was significantly compromised under the dual-task condition compared to the single-task condition. Unlike L1 speakers, whose MWE completion remains unaffected, the divided attention imposed by dual tasks disrupts the L2 learners’ ability to bind individual components into a complete MWE. This typically led to incomplete recalls of MWEs. For example, L2 learners might recall only a fragment like “大部分” (the majority) instead of the full MWE “绝大部分” (the vast majority). Under the single-task condition, where attentional resources are not divided, L2 learners tended to encode individual words separately (e.g., “绝, vast” and “大部分, the majority”) and then consciously combine these words to form a complete MWE. This suggests that MWEs have not yet been consolidated as unitary chunks in L2 learners’ long-term memory. Instead, these MWEs are stored as two or more smaller chunks, and binding these small chunks into a complete MWE requires attentional resources.

For both L1 speakers and L2 learners, no task effect was observed in word completion, a pattern that also appeared in MWE completion for L1 speakers. Prior research consistently shows that single words are inherently processed as individual chunks (Simon, Reference Simon1974). These findings suggest that, similar to disyllabic words, MWEs are processed as unitary chunks by L1 speakers. In contrast, the presence of a task effect in MWE completion for L2 learners, but not in word completion, indicates that L2 learners struggle to process MWEs as unitary chunks, unlike single words, which are inherently treated as such during processing.

Furthermore, engaging in dual tasks reduced the number of accessed MWEs per MWE sequence or the number of accessed words per word sequence during recall for both L1 speakers and L2 learners. Considering item access as an indirect measure for the number of chunks, this suggests that divided attention decreases the number of recalled chunks. These findings align with Baddeley’s working memory model, which underscores the role of attention in retrieving chunks from the episodic buffer. Taken together, while disrupted attention hinders L1 speakers from recalling a greater number of chunks, it does not affect the size of the chunks themselves.

Finally, the correlation analysis demonstrates that as language proficiency increases, L2 learners are better able to complete full MWEs, suggesting that they develop greater capability for storing larger chunks in long-term memory. Consequently, proficient speakers can directly recall these larger chunks from immediate memory, making them more resistant to attentional disruptions. As noted earlier, working memory maintains a constant capacity measured in the number of chunks, and individual differences in working memory capacity play a key role in determining how many chunks can be recalled. However, working memory does not affect chunking ability itself (Pulido, Reference Pulido2021; Pulido & López-Beltrán, 2023).

Experiment 1 showed that L2 learners had greater difficulty processing MWEs as unitary chunks compared to L1 speakers and demonstrated that proficiency positively influenced chunk formation. Unlike the self-assessed proficiency used in Experiment 1, Experiment 2 involved three training sessions with repeated practice of target MWEs, aiming to investigate how L2 learners improve their chunking ability and move closer to native-like performance.

Experiment 2

Methods

Participants

Twenty L2 learners of Chinese (9 males, 11 females) from Experiment 1 voluntarily participated in Experiment 2. Their ages ranged from 19 to 33, with an average age of 22.8 years. On average, participants had been learning Chinese for 31 months. All other details remained consistent with Experiment 1.

Materials

This experiment used the same materials (MWEs) as those in Experiment 1.

Procedure

This experiment consisted of four sessions administered using E-prime 2.0 over a ten-day period, with intervals of one to three days between sessions. The first session included an initial test, identical to that used in Experiment 1, assessing immediate recall with both single and dual tasks for MWE sequences. This test aimed to evaluate L2 learners’ initial performance in MWE completion and access. Following the First Test, the first training session was administered. The second and third sessions followed a similar structure, each starting with a test and followed by a training session. The fourth session consisted solely of a test, with no subsequent training. All four tests were consistent, differing only in the randomized presentation order of the MWE sequences.

The training items were identical to the test items, comprising 120 MWEs. The training employed a repetition task with two steps for each MWE. In the first step, participants listened to a recording of the three constituent words of an MWE, each word lasting one second and presented without prosodic information. Concurrently, the corresponding Chinese characters, the Pinyin for phonetic transcription, and English translations were displayed on the screen in Songti font, size 96, with spaces separating the three words. After listening, participants were asked to repeat what they had heard within two seconds. In the second step, participants listened to a naturally pronounced recording of the same MWE, lasting 1.5 seconds, while the visual display showed the same information as in the first step but without spaces. Following the audio, they were asked to repeat the entire MWE within two seconds. The recordings were pronounced by a male native Chinese speaker. Each training session lasts approximately seven minutes.

Results

Correlation analyses between the first and the fourth test demonstrated robust test–retest reliability across all measures of MWE completion and MWE access (all rs > 0.55, ps < .05). Additionally, two repeated-measures by-participant ANOVAs (F1) were performed to analyze MWE completion or access, within Task (single, dual) and Session (first, second, third, fourth) as within-factors. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied in cases where Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity was not satisfied. The statistical power for all significant main effects and simple main effects exceeded .900, suggesting a satisfactory sample size for this experiment. By-item F2 results are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

MWE completion. The results of ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Task, F(1,19) = 77.852, p < .001, η p 2 = .804, and Session, F(3,57) = 66.846, p < .001, η p 2 = .779. More importantly, there was a significant two-way interaction between Task and Session, F(3,57) = 52.695, p < .001, η p 2 = .735. Simple main effects showed that task effects were all significant across all four test sessions (see the means and ANOVA statistics in Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials). As illustrated in Figure 1A, dual tasks consistently disrupted MWE completion compared to the single task. Furthermore, using the difference in MWE completion between single and dual tasks as the dependent variable, paired sample t-tests with Bonferroni correction were performed between consecutive test sessions. Results showed a significant difference between the first Test and second Test, t(19) = 7.339, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.641, no significant difference between the second and third tests, t(19) = 1.902, p = .072, and a significant difference between the third and fourth tests, t(19) = 2.600, p = .018, Cohen’s d = 0.582. These results suggest that with successive practice sessions, the performance gap between single and dual tasks diminished over time.

Figure 1. MWE completion (A) and MWE access (B) under the single task and dual tasks across four tests for L2 learners.

Note. MWE = multi-word expression.

MWE access. The ANOVA results revealed significant main effects of Task, F(1,19) = 67.897, p < .001, η p 2 = .781, and Session, F(3,57) = 5.841, p = .001, η p 2 = .235. In addition, the two-way interaction between Task and Session was not significant, F(3,57) = 1.774, p = .162. As illustrated in Figure 1B, the differences in the number of MWEs accessed in recall between single task and dual tasks remained at a constant level across the four test sessions (see the means and ANOVA statistics in Table S4 of the Supplementary Materials). These findings suggest that repeated practice did not exert an influence on the task effect concerning the number of MWEs recalled by L2 learners.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 revealed a significant interaction between Task and Session in MWE completion, but not in MWE access. This interaction effect indicated a progressive improvement in MWE completion across the four tests, particularly under the dual-task condition. In other words, the findings highlight the critical role of repeated practice in helping L2 learners resist the disruption caused by a concurrent task.

In the initial test sessions, L2 learners likely stored an MWE, such as “绝大部分, the vast majority,” as two separate chunks (“vast” and “the majority”) in long-term memory. This suggests that L2 learners are required to encode the smaller chunks individually and subsequently combine them based on semantic and syntactic relationships when processing the MWE. This combination process consumed attentional resources from the central executive of the working memory system. With repeated exposure to the MWEs, L2 learners could gradually rely on semantic and syntactic associations to bind the smaller units into a cohesive larger unit, eventually formulating a single chunk. Once this binding was established, it no longer required attentional resources, making it more resistant to disruption by dual tasks. It is noteworthy that, after three training sessions, MWE completion under the dual-task condition approached the performance levels observed in the single-task condition. However, a significant difference between the two tasks still persisted, indicating that L2 learners had not yet fully internalized native-like chunks that could be processed as single, unitary representations.

Another possible explanation for the improved recall of MWEs is a general enhancement in memory for the testing materials. Repeated exposure may not only promote chunking but also strengthen memory for individual word lists. However, such memory improvements would be expected to occur similarly across both the single- and dual-task conditions. By comparing performance between these conditions, this potential confound is effectively controlled. Furthermore, while MWE completion showed a steady increase across consecutive test sessions, no such improvement was observed in MWE access. This divergence suggests that repeated practice primarily facilitates the growth of chunk size over time, rather than significantly enhancing general memory for individual words within the MWEs.

Moreover, divided attention consistently reduced the number of MWEs accessed during recall across all test sessions. This reduction remained constant throughout the four sessions, indicating a persistent and uniform effect of divided attention on the number of chunks retrieved from the episodic buffer in working memory.

In summary, consistent with the correlation results from Experiment 1, our findings suggest that repeated practice facilitates the growth of chunk size, while the number of chunks maintained in working memory remained unchanged. Similar to the effect of language proficiency, repeated practice enabled L2 learners to improve their chunking ability, moving closer to the native-like processing of complete MWEs as unitary chunks.

General discussion

This study examined the chunking ability in processing MWEs among L2 learners of Chinese and Chinese L1 speakers. In Experiment 1, participants from both groups performed an immediate recall task for MWEs and single words under single-task and dual-task conditions. The results showed that L1 speakers could accurately recall complete MWEs even under divided attention, whereas L2 speakers’ performance was disrupted by the dual-task condition. In addition, divided attention reduced the number of accessed MWEs in both groups. Correlation analysis revealed that language proficiency was associated with the formation of larger chunks, whereas working memory capacity correlated with the number of chunks accessed during recall. In Experiment 2, L2 learners showed a gradual narrowing of the performance gap between single-task and dual-task conditions in MWE completion across three training sessions, suggesting that repeated practice promoted the development of larger chunks over time.

L1–L2 differences in chunking ability for MWEs

In Experiment 1, the divided attention caused by dual tasks did not impair the completion of MWEs for L1 speakers, demonstrating that MWEs were processed as unitary chunks. Specifically, once an MWE is established as a unitary chunk, the combination of its constituent words no longer requires attentional resources. This finding aligns with the theory of chunking proposed by Baddeley and colleagues (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Hitch and Baddeley2018; Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009). Moreover, adult L1 speakers, benefiting from extensive language exposure, had already stored these MWEs in long-term memory. During recall, when the 15-word sequence exceeded the typical capacity of working memory, L1 speakers had to rely on stored linguistic knowledge, retrieving MWEs as unitary chunks from long-term memory. This highlights the role of chunking in bridging working memory and long-term memory (Isbilen et al., Reference Isbilen, McCauley, Kidd and Christiansen2020). This interaction mechanism enabled L1 speakers to resist interference from divided attention during recall. Finally, these findings are also compatible with the chunk-and-pass model (Christiansen & Chater, Reference Christiansen and Chater2016; McCauley & Christiansen, Reference McCauley and Christiansen2019), which posits that individual words must be rapidly chunked into larger units (e.g., MWEs) to overcome the “Now-or-Never bottleneck” imposed by the transient nature of speech and the limits of memory capacity in spoken production.

While L1 speakers generally store MWEs as single chunks, L2 learners tend to process them as multiple smaller chunks, reflecting fundamental distinctions in chunking ability between the two groups due to the differences in language experience. This finding is consistent with the Unified Competition Model, which posits that less proficient learners are prone to over-analyze utterances by breaking them into smaller fragments rather than processing them holistically (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Robinson and Ellis2008, Reference MacWhinney, Hickmann and Kail2017). The increased attentional demands experienced by L2 learners reflect a chunking disability, imposing a heavy cognitive load that leads to the retrieval of smaller, fragmented chunks instead of larger, unitary ones. This fragmentation of MWEs in speech production often manifests as disfluencies, hesitations, or pauses, posing a significant risk factor for reduced fluency in L2 learners.

Diverging from studies that primarily examine the processing advantage of MWEs through reaction time, eye-tracking patterns, or production measures (Pulido, Reference Pulido2021; Yi & Zhong, Reference Yi and Zhong2024), this study adopts a novel approach by examining this advantage from a chunking perspective. Our findings support the view that MWEs, rather than individual words (Pinker, Reference Pinker1991), function as the fundamental building blocks in language processing (Arnon & Christiansen, Reference Arnon and Christiansen2017; Taguchi, Reference Taguchi2008). Furthermore, our study provides both conceptual and methodological clarification regarding the differentiation between MWEs and chunks, two terms often used interchangeably in previous research (Wray, Reference Wray2002). Specifically, we argue that chunks should be defined based on the consumption of attentional resources, such that an MWE may be processed as either a unitary chunk or as multiple chunks, depending on the characteristics of MWEs and the speakers’ proficiency.

Chunk formation during L2 learning

The findings from the correlation analysis in Experiment 1 and the training effects observed in Experiment 2 collectively indicate that language proficiency and repeated practice facilitate a gradual increase in chunk size for L2 learners. Extended exposure to the target language enables the binding of small chunks into large ones (Ellis, Reference Ellis1996; Ellis & Sinclair, Reference Ellis and Sinclair1996), a process central to language acquisition (Christiansen & Chater, Reference Christiansen and Chater2016). This binding mechanism is governed by the central executive and phonological loop components of the working memory system (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley2000). Specifically, the central executive allocates attentional resources, while the phonological loop strengthens and consolidates associations among smaller chunks through rehearsal. Empirical studies have supported the phonological loop’s role in enhancing language learning outcomes (Acha et al., Reference Acha, Agirregoikoa, Barreto and Arranz2021; Linck et al., Reference Linck, Osthus, Koeth and Bunting2014). Over time, repeated binding leads to the formation of larger chunks stored in long-term memory, which reduces the attentional demands during chunking. However, the initial formation of large chunks places significant demands on attentional resources, which are taxed throughout the earlier associative processes. This progression in chunking can also be interpreted as an associative frequency effect (Ellis, Reference Ellis2017; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Hickmann and Kail2017). In addition, as L2 learners gain experience, chunking as a key protective factor in L2 learning gradually reduces the demands on attentional resources during speech production. In other words, the binding of individual words becomes increasingly proceduralized, thereby enhancing fluency (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney, Hickmann and Kail2017; Morgan-Short et al., Reference Morgan-Short, Sanz, Steinhauer and Ullman2010).

In addition, chunk size may serve as a reliable indicator of L2 language proficiency, as chunking ability is largely shaped by prior linguistic experience. This is consistent with evidence that chunking ability facilitates online sentence processing (McCauley et al., Reference McCauley, Isbilen, Christiansen, Gunzelmann, Howes, Tenbrink and Davelaar2017; Pulido, Reference Pulido2021; Pulido & López-Beltrán, 2023). In our study, chunking ability was assessed by evaluating the extent to which each MWE in a sequence was recalled, rather than simply measuring the total number of words recalled per sequence as used by Isbilen et al. (Reference Isbilen, McCauley, Kidd and Christiansen2020) and McCauley et al. (Reference McCauley, Isbilen, Christiansen, Gunzelmann, Howes, Tenbrink and Davelaar2017). This MWE completion approach provides a more precise reflection of chunking ability, since the latter measure can be influenced by both long-term memory and working memory capacity, with working memory not being directly linked to language proficiency.

Working memory capacity measured as the number of chunks

Experiment 1 demonstrated that divided attention reduced the number of chunks available for immediate recall, and Experiment 2 confirmed the consistency of this effect across four test sessions. Additionally, a positive correlation was identified between working memory capacity and the number of chunks accessed in immediate recall. These findings provide empirical support for Baddeley’s conceptualization of the episodic buffer within working memory as a capacity-limited storage system for temporary chunks (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley2000; Baddeley et al., Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Allen2009). Specifically, retrieving chunks from this buffer requires attentional resources. Both L1 speakers and L2 learners with greater working memory capacities can retain more chunks in the buffer during immediate memory, even under attentional disruptions. This finding is in line with Satori (Reference Satori2021), who demonstrated that higher working memory capacity benefits L2 listening comprehension, particularly when the task demands require significant attentional resources. This effect is pronounced among lower-proficient learners due to their reliance on less proceduralized language skills.

Conclusion

This study addresses a gap in the literature by investigating chunking ability in L2 learners compared to L1 speakers. Unlike L1 speakers, who store numerous large chunks in long-term memory, L2 learners tend to store fewer and smaller chunks. This fundamental difference helps explain why achieving native-like fluency in speech production is often challenging for L2 learners. As learners accumulate more language exposure, they gradually bind smaller chunks into large ones through rehearsal practice. This process allows L2 learners to retrieve MWEs as unitary chunks from long-term memory during speech production, leading to more fluent speech. This process also frees up working memory capacity, enabling learners to engage in higher-level language functions such as prosody, pragmatics, or discourse.

Three limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the uneven MWE completion among L2 learners posed challenges for developing a valid method to measure MWE access. However, the lack of correlation between MWE completion and MWE access suggests that these measures are independent of each other (all rs < 0.10, ps > .05), allowing both to be treated as valid dependent variables. Second, the self-reporting proficiency measure may not fully capture individuals’ overall comprehension and production skills. To improve reliability, future research should consider incorporating standardized L2 proficiency assessments. Third, future studies could explore whether the structural type of MWEs (e.g., full standalone sentences, dependent clauses) influences chunking ability in L2 learners, and whether such effects vary across languages with different word orders or morphosyntactic characteristics (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Tang and Privitera2024).

Replication package

All experimental materials, analysis code, and data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NXEJ0Z.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716425100441

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Beijing Language and Culture University (25ZX04). The authors thank Alan Baddeley, Lynne Reder and Michael Ullman for their comments on the design of the study. We also thank the Basque Center on Cognition, Brain and Language for providing support with data analysis during my postdoctoral period. We also thank Shiyi Lu and Gaoqi Rao for their help with corpus data, as well as Sichang Gao, Fei Gao, and Yuanyuan Huang for their help with data collection.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.