1.1 Introduction

Knowledge and understanding of energy are more essential than ever as society seeks to develop effective strategies for a sustainable energy future. The challenge for higher education is that the field of “energy” is inherently interdisciplinary. A successful energy education program must help students acquire knowledge of physical, chemical, geologic, and biologic processes, and knowledge of the economic, political, environmental, and social factors that influence decisions about our energy future. Teaching about energy provides a natural bridge to addressing one of society’s most pressing issues, that is, sustainability and resilience of our Earth system.

Business and political leaders are confronting higher education with a demand for the development of broad, transferable, professional competencies in their graduates such as innovation, creativity, problem-solving, critical-thinking, communication, collaboration, and self-management, among others. These competencies are at the foundation of individual and collective success in the workplace, yet employers report substantial deficiencies in these areas of applied skills and competencies (AAC&U 2019; Hart Research Associates 2018).

There is no “one size fits all” model for an energy curriculum. Each institution needs to build on its own strengths. The purpose of this chapter is to outline a collaborative approach to the development of an interdisciplinary undergraduate energy curriculum that embraces the strengths of and connections among STEM disciplines, social sciences, policy, communications, business, and the arts at your institution. The curriculum needs to include the development of applied skills and knowledge, i.e. competencies, that enable students to successfully perform in professional, educational, and other life contexts.

1.2 CTeAM and Five Key Questions

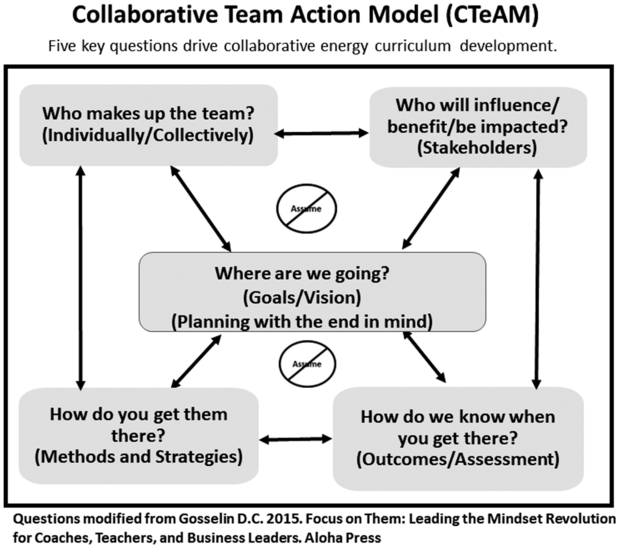

The key components for the collaborative approach are captured by five key questions in the Collaborative Team Action Model (C-TeAM, Figure 1.1). Before moving any further, we need to pause and define a couple of terms. First, collaboration is often used carelessly and interchangeably with two other c-words related to people working together – coordinate and cooperate. Collaboration and teamwork are also often used interchangeably. Although collaboration can be simply defined as two or more people (a team) working together (process) to develop and achieve a shared goal, vision, or purpose, it is a little more complex than just so-called teamwork. For collaboration to truly manifest itself, all participants need to feel a sense of parity with others in the group and the processes that are used need to provide an opportunity for each person to contribute to the creation of the shared goals/vision. Hence, the centrality of addressing the question of “where are we going?” in the CTeAM model. Once the shared goal is defined, the individuals and groups who created it can share control and leadership.

Figure 1.1 Collaborative Team Action Model

Figure 1.1Long description

A flowchart of the Collaborative Team Action Model or C T e A M outlines five key questions that drive collaborative energy curriculum development. These questions include the following. 1. Who makes up the team? Individually or Collectively. 2. Who will influence or benefit or be impacted? Stakeholders. 3. Where are we going? Goals, Vision, and planning with the end in mind. 4. How do you get them there? Methods and strategies. 5. How do we know when we get there? Outcomes or Assessment.

Another important term in the development of an energy curriculum is interdisciplinary. A committee with people from different departments is not necessarily interdisciplinary. Being interdisciplinary requires the intentional connection of the separate perspectives from various disciplines into an integrated framework that promotes boundary-crossing conversations and solutions related to the complexity of energy challenges.

Finding the time, energy, inspiration, and processes to create a new curriculum or new course, or to infuse energy-related concepts into an existing course is a challenge for all educators. Creating new interdisciplinary courses and curriculum involves instructors from a home department and other departments, which adds significant complexity. The idea of creating a whole new curriculum can easily become overwhelming. Fortunately, there are processes and resources that you can access to help you move forward effectively and efficiently. Regardless of the level – a unit, class, or program – at which you want to make the curricular transformation, employing the key C-TeAM questions will help maintain focus. The National Association of Geoscience Teachers’ On the Cutting Edge Professional Development Program, specifically the Traveling Workshop Series, the Science Education Resource Center, and the InTeGrate projectFootnote 1 (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, Egger and Taber2019) provide a range of resources that can help educators navigate the challenges. These resources and programs to which the author has contributed will be featured throughout this chapter.

1.2.1 Where Are We Going? (Planning With the End in Mind)

Planning with the end in mind is much more than choosing a textbook. It is a form of backward design (Wiggins and McTighe, Reference Wiggins and McTighe2013). Backward design brings to the forefront a number of questions: What does our future look like? How does our program fit into the future? How do we prepare our students to work and learn in that future? Addressing these types of questions defines where we want to take our students and the end we have in mind for them. For some faculty, planning with the end in mind focuses on the textbook that they should use. To initiate change in your curriculum whether it be a unit, class, or program, it is important to define what end in mind you have for the students. A family trip metaphor comes to mind: Are we headed to a quiet lake or to Disneyland? Keeping the end in mind focuses our planning energy and talents and creates expectations for the trip’s outcomes – catching a bunch of fish or spending your day in an amusement park.

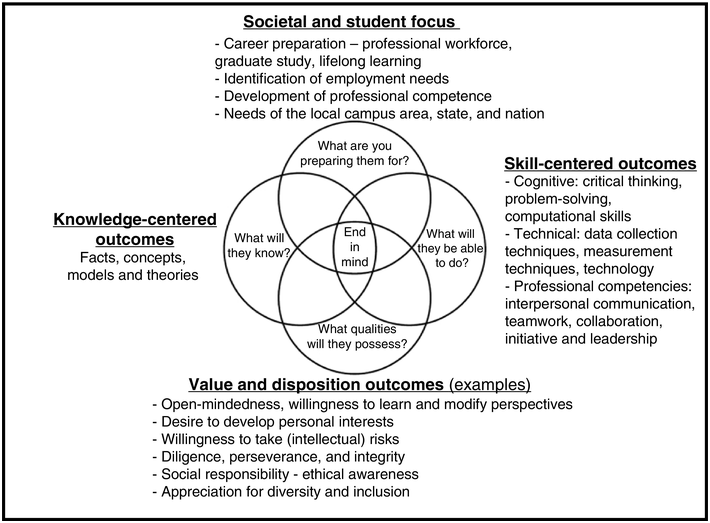

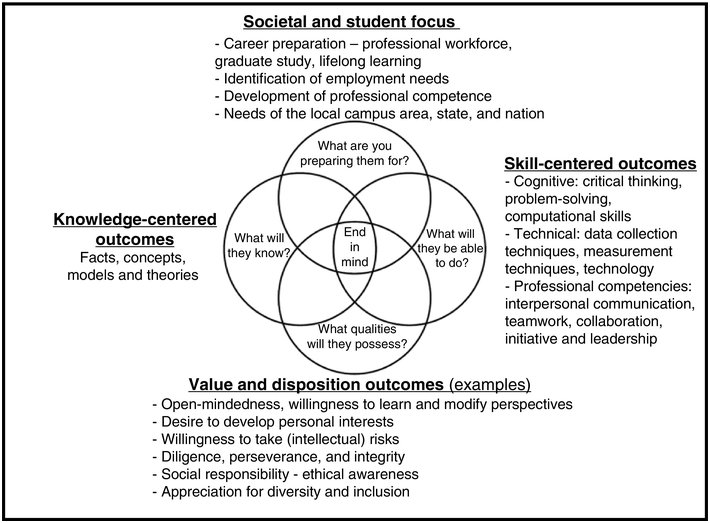

Your end in mind (Figure 1.2) needs to define what the student knows and can do when the specific educational endeavor you are planning is completed. The ends that you have in mind should consider the development of the whole person as a professional. Although you may not realize it, what you are doing in your classroom and throughout your curriculum is contributing to the development of the whole person. That means that you need to think about how you are preparing your students for the workforce, graduate and professional studies, and life-long learning.

Figure 1.2 The end in mind defines what the student knows and is able to do when the specific educational endeavor you are planning is completed. The end in mind is grounded in the needs of society and the student and includes outcomes related to knowledge, skills, and values.

Figure 1.2Long description

The Venn diagram focuses on four key outcome areas, namely, knowledge-centered outcomes like facts, concepts, models, and theories, skill-centered outcomes like cognitive skills like critical thinking, technical skills like data collection, and professional competencies, and value and disposition outcomes such as open-mindedness, social responsibility, and appreciation for diversity. The central, end in mind, question, emphasizes the need to plan with specific goals, including preparing students for professional careers, graduate study, and lifelong learning, while addressing the needs of both students and society.

As part of the development of the whole person, each of us, in the back of our minds, has thoughts and ideas about the types of qualities we want our students to possess. For example, you may want all your students to have an appreciation for the importance of diversity and inclusion. All these academic or personal quality expectations, or learning outcomes, should be articulated for both your student’s and your instructional colleagues’ benefit. Addressing the question of where you want to take the students helps create clarity about what you will be teaching that focuses and prioritizes your efforts. You cannot teach them everything they need to know in an undergraduate curriculum, but you can set them up for a life-long journey of learning.

Thus far, we have referred to the development of the end in mind as if it were being developed by one person. Of course, this is not going to be the case. Developing energy-related education requires a variety of disciplinary “lenses” to understand the complexity of the issues. Bridging disciplines requires recognizing differences in disciplinary cultures, valuing these differences, and respecting the spectrum of expertise and interests, values, and approaches within the group. The intent is to create educational experiences that demonstrate how different perspectives and strengths are beneficial when developing solutions to real-world energy problems.

Identifying the important components of energy education means exploring what a student should know and be able to do – that is, exploring the general characteristics of energy literacy. The United States Department of Energy in 2010 initially published a document entitled Energy Literacy: Essential Principles and Fundamental Concepts for Energy Education (DOE 2017). It outlines the energy concepts that will help individuals and communities make informed energy decisions, if understood and applied. According to this document, an energy-literate person is able to:

assess how much energy they use, for what purpose, and identify the energy sources that meet their needs,

communicate about energy and energy use in meaningful ways to different audiences, and

generate informed energy-use decisions based on knowledge of impacts and consequences.

The challenge, as well as the opportunity, is that concepts related to energy are fundamental to many different types of courses, from anatomy to zoology. Thus, there are many pathways to introduce energy themes using an interdisciplinary approach and involve a wide range of contexts in your curricular planning, depending on the expertise and interest of your instructional team.

An examination of potential topics suggests a wide range of opportunities for interdisciplinary boundary crossing:

Origin and occurrence of fossil fuels: the formation of coal, oil, and natural gas.

Environmental, societal, and health impacts of extraction, transportation, processing, and use of various renewable and non-renewable energy sources.

Power vs. energy, thermodynamics, conservation of energy, conversion loss.

Policy, regulation, markets, incentives, industrial and market structures, and taxation.

Energy grid and complexities of transporting and converting energy into a usable form.

To create a shared vision and goals for your curriculum using energy literacy and emphasizing an interdisciplinary approach as a starting point, you must create a process that allows the participants involved in curriculum development to explore a variety of options and ensure that all voices are heard. There will be struggles with many issues as you develop your learning outcomes. These include, but are not limited to, content in the curriculum, depth vs. breadth in the curriculum, areas of instructor expertise, strengths of supporting academic programs, cocurricular programming, access to local resources, and international research and learning. You will need to use methods and strategies that allow participants to present their viewpoints as well as create opportunities to struggle with the differing viewpoints. The SERC website provides additional methods and strategies.Footnote 2

1.2.2 Who Makes Up the Team? (Individually and Collectively)

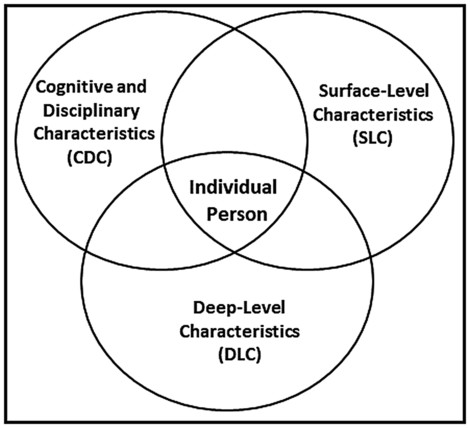

Individual team members are the fundamental building blocks for every team. A key C-TeAM question is: “Who are these individual building blocks and how will we put them together, so they collectively interact and effectively function to develop a shared vision?” The process or series of processes to develop the relationships among the team starts with a basic knowledge of the characteristics that each person brings to the team. There are three general categories of characteristics that you must consider (Figure 1.3):

Cognitive and Disciplinary Characteristics (CDC): disciplinary knowledge, expertise, experiences, and perspectives. These include cognitive processes like thinking, knowing, remembering, judging, and problem-solving.

Surface-Level Characteristics (SLC): demographic, social category, and observable individual differences. These refer to readily detectable attributes such as gender, age, sexual orientation, ethnicity, ability/disability, and cultural traditions.

Deep-Level Characteristics (DLC): task-related, psychological, informational/functional, and underlying attributes. These include less observable deeper-leveled attributes such as values, mindset, attitudes, beliefs, functional expertise, and mental models.

Figure 1.3 The characteristics of individuals who comprise the team are important to learning how to navigate and negotiate differences among team members.

Commonly, team members are selected based on their cognitive and disciplinary characteristics. However, it is the differences in the surface- and deep-level characteristics that will create some of the biggest challenges to blending team members together. Some of these characteristics are easily observable – age, sociocultural background, skill level, and behaviors, to some extent. Other characteristics are not quite as apparent, including what motivates a person, the details of their behavioral style, their mindsets, their values and beliefs, what they know, their strengths, their weaknesses, and their capabilities. The more you can invest in knowing the members of your team in the context of your challenge, the better you can build off their strengths, and the more effectively your group can navigate and negotiate differences among team members. Similarly, knowing yourself, your characteristics, and related tendencies is also critical (Gosselin Reference Gosselin2015). Knowing who you are is the foundation upon which all your relationships are built. Relationships are at the heart of a team because that is where trust is built – without trust you will have a dysfunctional team (Lencioni, Reference Lencioni2002). Gosselin and colleagues (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, Thompson, Pennington and Vincent2020; Gosselin Reference Gosselin2023) provide strategies and considerations concerning the blending of surface- and deep-level characteristics. O’Rourke and colleagues (Reference O’Rourke, Crowley, Laurseb, Robinson, Vasko, Hall, Vogel and Croyle2019) provide a guiding process to explore the cognitive and disciplinary diversity of interdisciplinary teams.

1.2.3 Who will Influence, Benefit, and/or Be Impacted? (Stakeholders)

Your curriculum will influence, benefit and/or impact others at a variety of levels. These others are your stakeholders. To focus on the importance of including input from stakeholders, consider the following metaphor:

You have a pebble in your shoe. No one other than you can know exactly how that pebble feels. Others may have read about pebbles, seen pebbles, or even had a similar experience with a pebble caught in their shoe. However, you are the expert on your situation because you are experiencing it. The same concept applies to any problem or challenge that impacts multiple people. People who directly experience the actual problem have a much different perspective on what needs to be done to resolve the problem than a politician who has only read about the problem in the newspaper or a person who once wrote a college paper on the problem.

This story highlights the fact that different people bring different levels of knowledge and experience to addressing the problem, all with potential value. In the context of curriculum development, engaging stakeholders – faculty, students, staff, administration, curriculum committees, department heads, etc. – provide a clearer picture of the opportunities, challenges, support, assets, and potential pitfalls that may be encountered during the curriculum development process. When stakeholders are given a voice in the process and can contribute to the development effort, they will get a sense of ownership and become supporters of the process instead of obstacles. They will take ownership and do their best to make it work. These conversations strengthen your position and develop social capital by increasing your web of acquaintances, friendships, buy-in, and support from the community. Stakeholder engagement also reduces the opportunities for you to be blindsided by perspectives and concerns you didn’t know about. Creation of a more diverse set of contacts and connections leads to new relationships that can spark new initiatives that would not have come into existence without this process.

The identification and inclusion of stakeholders is part of an emergent process critical to the development of shared goals and vision for any interdisciplinary educational program. Investing time in stakeholder conversations, especially during the early stages of the process, will save you time and energy in the long run. The earlier you initiate the process of engaging with stakeholders, the better.

The two most obvious stakeholder groups that directly impact, affect, and benefit from your curriculum development activities are instructors and students. Students are commonly not included in the development process, but it is critical to understand where the students are and what characteristics they bring into the classroom. Keep the question, “For whom are we developing the curriculum?” at the forefront of your thinking. The answer to this question is not trivial and requires you to invest time learning about the characteristics of your students.

When working with a group of students, have you ever said something like “When I was in school, we did it differently” or “When I got my first job, that wouldn’t fly?” Those statements reflect an inward-looking focus on your experience and your assumptions about your students. Make extra effort to understand the experiences and goals of your students. Be aware that a majority of young adults now consider getting a job as the primary purpose for earning a college degree (Pasquerella Reference Pasquerella2019).

The fact that today’s students focus on career preparation highlights the importance of preparing students for a future world in which students will need to work and live. It also leads us to another set of stakeholders who should be engaged in your process: local and global employers. Employers across different industries for decades have overwhelmingly reiterated the need for employees who can learn continuously and think beyond the boundaries of a specific major. The AAC&U (2018) note that employers seek graduates who:

are creative,

can communicate orally to multiple audiences,

can think critically and analytically,

use ethical judgment and make ethical decisions,

take individual initiative whether working as part of a team or independently.

Fundamentally, we need to keep asking tough questions related to how well higher education is preparing students for our future world.

Beyond faculty, students, and employers, there are additional stakeholders who can have a major impact on your ability to plan and implement new programs. For example, curriculum committee members, department heads, any staff members who work directly with faculty or students, donors, and deans can all influence your work for good or ill. Their motivation might be intellectual, academic, philosophical, or political, but your process and curriculum will benefit from taking their needs into account.

1.2.4 How Do You Get Them There? (Methods and Strategies)

The development of an interdisciplinary energy curriculum needs to use a variety of methods and strategies at a variety of levels. The process or collection of processes needs to create an environment that:

cultivates and nurtures each team member,

values the contributions of each team member,

uses supportive behaviors,

allows others to ask questions as well as admit and learn from their mistakes.

Edmondson and colleagues (e.g., Edmondson Reference Edmondson, West, Tjosvold and Smith2003; Edmondson and Lei Reference Edmondson and Lei2014) characterize this type of environment as “psychologically safe.” Psychological safety provides a member with the feeling that the team environment is a safe place for interpersonal risk-taking, where ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes can be shared without fear of embarrassment, rejection, or punishment. A safe team climate is characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect, and allows team members to feel comfortable being themselves.

A psychologically safe environment helps strengthen relationships and develop trust-building behavior. Increased trust between individuals also increases the level of psychological safety, which, in turn, improves the quality and creativity of the outcome from the group. For many people, discussing the creation of psychological safety may sound “touchy-feely,” but if you fail to cultivate a psychologically safe environment, you will not get the most out of the team members who have been engaged to do important work.

Clark (Reference Clark2020) recognizes four different levels or stages of psychological safety:

Inclusion Safety: members are comfortable being present, feel included, and feel wanted and appreciated.

Learner Safety: members are comfortable learning through asking questions. They can experiment, make (and admit) small mistakes, and ask for help.

Contributor Safety: members contribute their own ideas, without fear of being embarrassed or ridiculed.

Challenger Safety: members question and challenge others’ ideas as well as suggest substantial changes to ideas, plans, or ways of implementing and working.

An important point here is that it takes time for a team to progress through these stages. To create an interdisciplinary energy curriculum, members of the development team need to be able to contribute ideas without fear as well as question the ideas of others. This leads to true innovation. Each time a new member joins the team there is the likelihood that the stage of psychological safety will change.

To help you address these five key questions, several strategies are provided below. Many of these are based on resources available from the National Association of Geoscience Teachers’ Workshop on Cross-Campus Environmental and Sustainability Programs from the Traveling Workshop Series and the InTeGrate project (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, Egger and Taber2019).

Strategies: Planning with the End in Mind

Obviously, the overall goal is to create an interdisciplinary energy curriculum. However, the devil is in defining the details of what will be included in the curriculum. Developing the details for the curriculum starts with asking what you want your students to be able to know, do, and value at the end of your energy education program. A first step toward addressing this question is to access ideas and perspectives from colleagues. A useful exercise to explore the different perspectives on your curriculum team is the “ideal student” exercise developed by Savina and colleagues (Savina et al. Reference Savina, Gross and Danielsonn.d.). This exercise asks instructors to write a recommendation letter for the “ideal student” graduating from the program. In the letter you identify the skills, knowledge, experiences, behaviors, and values that students graduating from your program should gain or understand. To ensure that everyone has a voice, participants share the list of characteristics of their ideal students collectively in small to large groups, depending on numbers. This process provides the framework to develop an explicit set of measurable and assessable program-level learning outcomes.

To further inform the development of and provide additional context for the learning outcomes in your programmatic ecosystem, use a process of review and reflection. This process starts with a review of mission statements, goals, and other strategic documents for the university and relevant departments/programs. Focus especially on documents that relate to interdisciplinary programs. Another level of review should involve reading reports and acquiring information about expectations for energy-literate people (e.g., DOE 2017), as well as the expectations and evolution of higher education (e.g., AAC&U 2019). Using this information, each person writes a reflection that provides their vision for where the program should be in five to ten years given opportunities, challenges, and constraints on institutional resources. The reflection should include specific thoughts as to how the curriculum will contribute to the institution’s priorities, expectations, and values, as well as to the overall expectations for higher education.

For both the ideal student exercise and review-and-reflect activities, small groups should be convened after the individual activity to identify common themes and key ideas. These are then presented to the larger group. The larger group then discusses the various themes and ideas followed by the identification of common elements upon which your shared vision for the learning outcomes will emerge.

Strategies: Individual and Collective Characteristics of the Team

Considering that the development of energy curriculum involves an interdisciplinary group, it is useful to have a process that identifies professional strengths, interests, characteristics, and backgrounds of the people in the group. Explicit exploration of these attributes reduces the assumptions team members make about each other, which helps avoid unintentional interpersonal challenges between participants. In an academic environment, the primary focus is usually on a person’s cognitive and disciplinary characteristics – their disciplinary knowledge, expertise, experiences, and perspectives. These are usually explored by having each person introduce themselves and the department with which they are affiliated. This is a great start, but it is important to explore perspectives, assumptions, and strategies for the generation of knowledge in the different disciplines represented in your interdisciplinary curriculum group.

The Toolbox Dialogue initiative survey (http://tdi.msu.edu/; Eigenbrode et al. Reference Eigenbrode, O’Rourke, Wulfhorst, Althoff, Goldberg, Merrill, Morse, Nielsen-Pincus, Stephens, Winowiecki and Bosque-Perez2007) provides a framework for the exploration of epistemological and philosophical differences that exist among team members related to motivation, communication, methodology, values, reality, and stakeholder participation. Box 1.1 provides an example set of guiding questions modified from the Toolbox Dialogue initiativeFootnote 3 used by Gosselin et al. (Reference Gosselin, Thompson, Pennington and Vincent2020). The Toolbox instrument consists of a set of elements, each comprising a core question and probing statements that concern philosophical aspects of research (Box 1.1). Participants use the Likert-type scale to take a position as a springboard for discussion. A “talking stick” enables equitable participation by allowing only the person holding the stick to speak. Active listening approaches should be used. This conversation provides opportunities for individuals to describe and discuss their perspectives and assumptions regarding disciplinary epistemology. Broadly, the topics covered include participant perceptions of the nature of reality and scientific inquiry, the tension between qualitative and quantitative approaches, the importance and type of communication, and other deeply ingrained ways of thinking that can differ between disciplinary cultures (Eigenbrode et al. Reference Eigenbrode, O’Rourke, Wulfhorst, Althoff, Goldberg, Merrill, Morse, Nielsen-Pincus, Stephens, Winowiecki and Bosque-Perez2007; Looney et al. Reference Looney, Donovan, O’Rourke, Crowley, Eigenbrode, Rotschy, Bosque-Perez, Wulfhorst, O’Rourke, Crowley, Eigenbrode and Wulfhorst2013).

Responses to sub-questions use the following Likert scale:

Disagree___________ Agree

1 2 3 4 5 I don’t know N/A

Motivation**

Core Question: What motivates me to participate in research?

1. Knowledge generated by scientific research is valuable even if it has no application.

2. Good science products are more important to me than major funded projects.

3. Incorporating one’s personal perspective in framing a research question is never valid.

4. Collaborative research should be motivated primarily by grant opportunities.

Communication & Organization

Core Question: How important are communication and organization to successful scientific collaboration?

Methodology**

Core Question: What methods do you employ in your disciplinary research (e.g. experimental, case study, observational, modeling)?

1. Basic and applied research are equally important for science research.

2. Scientific research (applied or basic) must be hypothesis driven.

3. Qualitative science is as credible as quantitative science.

4. The methods I use in my disciplinary research are easily integrated with methods used by researchers in other disciplines.

5. Experimental work conducted in the laboratory is too dependent on context to yield general principles.

6. Modeling, fieldwork, and laboratory research are of equal importance for environmental science research.

Values**

Core Question: Do values negatively influence scientific research?

1. Incorporating one’s personal perspective in framing a research question is never legitimate.

2. Value-neutral scientific research is possible.

3. Scientists should never engage in advocacy.

4. Public outreach detracts from good science.

5. Responsible scientific research requires meeting the productivity goals of your

6. Scientists have a moral obligation to improve society through research.

Reality**

Core Question: Do the products of scientific research more closely reflect the nature of the world or the researchers’ perspective?

1. Scientific research aims to identify facts about a world independent of the investigators.

2. Scientific claims need not represent objective reality to be useful.

3. Models invariably produce a distorted view of objective reality.

4. The subject of my research is a human construction.

The ability to understand surface- and deep-level characteristics of yourself and other members of your team is one of the most challenging tasks that individuals face during their journey to becoming an effective collaborator, teammate, and leader (Gosselin Reference Gosselin2015). These characteristics are fundamental input parameters into any team, and diversity among team members is important for team effectiveness (Marks et al. Reference Marks, Mathieu and Zaccaro2001; Salazar et al. Reference Salazar, Lant, Fiore and Salas2012; Driskell et al. Reference Driskell, Salas and Driskell2018; Mathieu et al. Reference Mathieu, Wolfson and Park2018). These characteristics strongly influence the “what” people do and “why” they do it in a group. A person’s dispositional characteristics include beliefs, feelings, and values (motivational drivers), as well as a person’s actions and reactions (behaviors) (Ajzen Reference Ajzen2005; Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, Thompson, Pennington and Vincent2020). Navigating dispositional distance – the differences in dispositional characteristics among a group of team members – is important to team success (Gosselin et al., Reference Gosselin, Thompson, Pennington and Vincent2020).

There are many instruments that can be used to explore the dispositional characteristics of participants on interdisciplinary teams. Gosselin et al. (Reference Gosselin, Thompson, Pennington and Vincent2020) describe the use of the TriMetrix® assessment tool (TTISI 2012) to explore dispositional characteristics. The TriMetrix® HD assessment tool is a psychometric tool developed by Target Training International Success Insights Ltd. (TTISI). A basic premise behind the use of this tool is that through a deeper knowledge of individual dispositional characteristics, and those of collaborators, relationships, communication and trust will grow (e.g., Lencioni Reference Lencioni2002; Bonnstetter and Suiter Reference Bonnstetter and Suiter2013; Gosselin Reference Gosselin2015). The TriMetrix® instrument assesses the personal attributes of the participants using self-reported dataFootnote 4. Results from this online instrument provide individual and group TriMetrix® reports that provide explicit information about participants’ behavioral characteristics and motivational drivers that are linked to communication styles and approaches.

The following provides some examples of probing questions related to “Who is on the team?” to explore the background and nature of the members of your team.

Where are we going?

Goal: Create an interdisciplinary energy curriculum

How do we know when we get there?

Outcomes:

What will students be able to know and do?

What will student success look like?

What will program success look like?

How will the program look different in five years?

To what extent are students meeting employer needs?

Metrics and Data:

Retention – Major, College

DFW rates

Graduation rate

Number of majors

Alumni survey

Satisfaction data – course and program

Who is on the team?

What training do instructors have related to teaching and learning?

What do faculty know about their students, collectively and individually?

What challenges/barriers do instructors perceive about meeting the goal?

What resources do faculty need to achieve the goal?

How do instructors prefer to communicate – personally or in meetings?

How do instructors manage their time in achieving deadlines?

What do instructors think it means to be a successful student?

What do faculty know about employer expectations?

How do we get there?

What process(es) involve instructors in curriculum development?

What human and financial resources are available to support change?

To what extent do instructors have the ability to implement high-impact education practices?

What systems/programs are available to support teaching?

What tools/infrastructure do programs need to achieve their goal?

What are the institutional challenges/barriers to achieving the goal?

What structures (administrative, power, P&T) create challenges to achieving the goal?

What programs are available to support student success?

Who are the stakeholders?

What are the personal goals of your students?

What does success look like for your students?

What are the characteristics of the students?

✓ Level of preparation and content knowledge

✓ Culture and ethnicity

✓ Dispositional characteristic – behavioral styles motivational drivers

What are your student’s strengths?

What do students need to know about the goal?

What are the challenges and barriers for students to achieving the goal – academically and personally?

What are the personal goals of the student?

What tools do students need to achieve their goals?

Strategies: Stakeholder Analysis

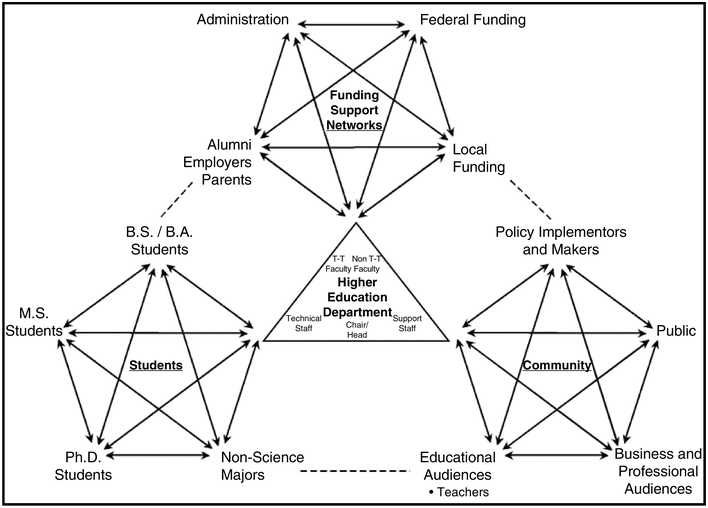

The identification and inclusion of stakeholders is an emergent process that requires time and energy, but that investment will result in a more inclusive, more effective curriculum. Through stakeholder analysis, team members may discover new opportunities for collaboration across campus, with government agencies, and with the community. Use a multilevel approach to stakeholder identification that considers a broad range of relevant higher-education stakeholders (Figure 1.4) and the extent to which they value what you do.

Figure 1.4 Summary of stakeholders in higher education.

Figure 1.4Long description

A diagram depicts the interconnected relationships among various stakeholders in a higher education system. Key elements include B.S., B.A., M.S., and Ph.D. students, T-T, non-T-T faculty, administrative staff, and external stakeholders such as alumni, employers, and community groups. Arrows indicate the influence of federal and local funding, policy makers, and public audiences. The diagram highlights the complex web of relationships between higher education departments, funding networks, and community involvement in shaping academic programs.

Start by brainstorming. Participants should focus on generating, extending, and adding to ideas, reserving criticism for a later stage of the process. By suspending judgment, participants will feel free to generate unusual ideas.

Step 1 starts at the individual level using your current knowledge and experience. Individual brainstorming, just by yourself, is very useful for the start of any new project. Record each potential stakeholder on an individual sticky note. Be creative, because there are no wrong answers, and everything is in play. Think about the people and groups that interact with your program, especially students, from multiple angles, and reflect in particular about which stakeholders value the same things you do.

Step 2 of the process is to collectively organize the stakeholders into stakeholder categories – primary, secondary, and key (Box 1.2).

Primary stakeholders: people or groups who are directly affected, either positively or negatively, by the efforts or the actions of your program, such as students, faculty, and staff. They have a direct stake in the program’s success and stand to gain or lose services, skills, money, goods, social connection, etc. as a direct result of it.

Secondary stakeholders: people or groups who are indirectly affected, either positively or negatively, by the efforts or the actions of your program, such as people in other departments or employers. Their jobs or lives might be affected by the process or results of the effort. Secondary stakeholders are interested in the program’s impact on the community but do not have a direct stake in the program’s success.

Key stakeholders: people in positions that convey influence, such as deans and vice chancellors. Individuals or groups of people who can devise, pass, and enforce policy and procedures that affect your work, such as department heads, or members of curriculum and other university committees. Individuals and groups who may not be affected by or be involved in your program but nonetheless care enough about it that they are willing to work to influence its outcome, such as funders, government officials, heads of businesses, community activists, and other community figures who wield a significant amount of influence.

Start by doing this silently. A potential way to start is to give everyone the opportunity to place their sticky note into a category on a white board or poster paper. Sequentially do this until all sticky notes have been organized. Once everyone has been given the opportunity to participate in the silent categorization, ask each person to silently move sticky notes to other locations if they so desire. Go to an interactive group activity to discuss and negotiate the organization.

Additional stakeholder information can be collected by consulting with organizations that either are or have been involved in similar efforts, or that work with the population or in the area of concern. Secondary data, such as historical records, correspondence files, newspaper articles, and census information can provide information about a local area and its demographic characteristics that might be taken into consideration.

Step 3. At this stage you may need to step back and ask some questions of your stakeholders. Do not guess what stakeholder interests are in your program. Ask them what’s important to them. Explore their concerns. Most stakeholders will tell you how they feel about a potential or ongoing effort, what their concerns are, and what needs to be done or to change to address those concerns. We emphasize questions about students because any educational program must understand where the students are before it can even begin to help them get where they need to go. There may be constraints on the time and resources available for this process, but the more you can invest in knowing your students, the better you can build upon their strengths, and the more effective your curriculum will be.

Circle the people/groups that you feel are most important to your program and the extent to which you feel they support your program. Don’t worry if it gets a little messy. As you move forward, addressing the concerns of your stakeholders will increase the likelihood that it will get through the process of curriculum approval and develop students who can meet the expectations of employers and graduate programs.

Strategies: Program and Curriculum Design

Beginning with the end in mind, and informed by stakeholder analysis, you have identified program-level learning objectives that include the knowledge, skills, and personal attributes (values and dispositions, Figure 1.2) that you want to see in successful graduates. As students progress through the program, be sure that they practice the concepts, skills, strategies, and ways of thinking that will lead them to those outcomes. If you develop a full curriculum, provide opportunities to practice in both courses and in cocurricular activities outside the classroom.

Program-level learning outcomes are not the domain of a single course. They should be integrated into coursework at many levels, and in a variety of contexts so that students interact with them throughout their preprofessional training. Integrating them across your entire program requires scaffolding of learning – an intentional sequencing of instructional activities. Scaffolding involves “…a variety of instructional techniques used to move students progressively toward stronger understanding and, ultimately, greater independence in the learning process… teachers provide successive levels of temporary support that help students reach higher levels of comprehension and skill acquisition that they would not be able to achieve without assistance” (Glossary of Education 2015).

Scaffolding learning sequences in a program begins in introductory courses that prepare students for more rigorous treatment of subject matter and advanced skill development in higher-level classes. The sequencing should follow Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Skills (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Krathwohl, Airasian, Cruikshank, Mayer, Pintrich, Raths and Wittrock2001) in which there is increasing use of higher levels of cognitive skills in higher-level courses. In planning learning sequences, introductory courses provide the foundational concepts and skills that students will further develop and add to as they move through higher levels of instruction and upper-division courses. Lessons learned in lower-division courses are applied to more complex situations at subsequent higher levels of instruction.

Consider applying the “Rule of Threes” throughout your courses and curriculum: if something is worth learning, students need to have at least three solid exposures to that topic. For example, a sequence of learning should provide early exposure to a topic in an introductory course, followed by competence and hopefully mastery of key concepts and skills over the four-year curriculum. Central ideas are emphasized at different levels and from different perspectives. Class activities are part of a larger fabric and not just “busy work” assignments. Instructors in the program cannot focus only on their own classes: they need a full understanding of how their course learning outcomes contribute to the overall program learning outcomes.

To complement the scaffolding of instruction, use high-impact practices (HIPs) to offer students multiple opportunities to develop their skills and abilities (Rhodes Reference Rhodes2019). Examples of HIPs are first-year seminars, common intellectual experiences, learning communities, writing-intensive courses, collaborative projects, undergraduate research, diversity, and global learning, ePortfolios, service and community-based learning, internships, and capstone courses or projects. Students in HIPs also experience diversity through contact with people, thoughts, values, and beliefs different from their own.

HIPs have common features that enhance student learning and achievement. These include:

Students devote significant time and effort to purposeful tasks that connect them to their academic program.

Students interact with faculty, peers, and, often, community members about substantive matters over extended periods of time.

Students connect what they are learning to different settings on and off campus.

For example, the Energy and the Environment course hosted by Penn State University (Alley et al. Reference Alley, Blumsack, Bice, Feineman and Milletn.d.) explores the impact of an increasing population, economic growth, and finite fossil fuel resources on energy supply systems and the climate. In Renewable Energy and Environmental Sustainability, Cuker and colleagues (Reference Cuker, Chambers, Crawford, Gosselin, Egger and Taber J.2019) explore a variety of sustainable energy technologies with emphasis on understanding the fundamental scientific properties underlying each. The course uses hands-on experimentation and learner-centered approaches that minimize the role of lecturing and promote active learning approaches.

Participating in these practices in a coherent, academically challenging curriculum infuses opportunities for active, collaborative experiences that deepen learning and help students interrogate their values and beliefs and how they may be altered, refined, and developed.

1.2.5 How Do We Know When We Get There? (Assessment)

Many academics cringe when they hear the word assessment. However, just like an effective research program requires data collection, academic program administrators must monitor effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. Continuing with the research program analogy, an effective assessment program also requires careful planning, which must consider a variety of metrics and data. These metrics are both directly and indirectly related to the quality of the educational experience at the department/program level.

Assessment data should be both formative and summative. Formative assessment collects information that can be used to improve instruction and student learning while it’s happening and can inform the process of teaching to improve learning. Summative assessments evaluate student learning progress and achievement of the learning outcomes at the conclusion of a specific instructional period – usually at the end of a project, unit, course, semester, program, or school year.

In addition to your curriculum group addressing the questions related to outcomes, additional discussion should focus on these questions:

What do you want/need to know about your program?

What do you need to report to your administration?

What do you want to advertise to prospective students, to your administration, to the energy community, to the larger civic community?

What evidence do you need to answer these questions?

Where are the places in the program to gather this data? Is it already being collected by the program, department, or institution?

Using the information acquired by addressing the five key questions, you can create a program matrix (Savina et al. Reference Savina, Buchwald, Bice and Boardman2001). The program matrix visually illustrates your program learning outcomes, course outcomes, and course activities. Although every course has its own specific student learning outcomes, the matrix approach will help align all your courses with your overall programmatic goals. The matrix provides a framework for program assessment that integrates and identifies opportunities for gathering formative and summative data.

With this approach to curriculum development, instructors reflect on their own and learn about other instructors’ courses and teaching styles. This builds collegiality and contributes to a collaborative environment. Instructors also develop a shared responsibility for students achieving the learning outcomes. Ultimately, student educational experiences are better coordinated, and students feel better supported and prepared (Savina et al., Reference Savina, Buchwald, Bice and Boardman2001; Mook and Savina Reference Mook and Savina2014).

1.3 Conclusion

There are many challenges to creating an interdisciplinary energy curriculum. There is no “one size fits all” model. The C-TeAM collaborative approach provides a framework for an interdisciplinary group to embrace the strengths of and connections among STEM disciplines, social sciences, policy, communications, business, and the arts at their institution. Using a continuum of processes and strategies, curriculum designers can build on a shared vision for learning outcomes and input from stakeholders. This integrated framework promotes the development of boundary-crossing courses and curriculums that can prepare students to address current and future energy challenges.