Introduction

Support for the far right has dramatically increased in the last twenty years in many countries around the world, and many factors have been said to contribute to this recent success (for a review, see Golder Reference Golder2016).Footnote 1 Recently, much of the discussion has revolved around the question of backlash, the notion that far-right success is a reaction to perceptions of economic and social change. Backlash is therefore a two-step process. First, societies experience some form of change, which can either be long-term shifts in the distribution of economic and social power (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024; Baccini and Weymouth Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021) or specific policies and events, such as austerity (Hübscher et al. Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2023), refugee arrivals (Dinas et al. Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019), the expansion of minority rights (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2014), or climate change mitigation policies (Colantone et al. Reference Colantone, Di Lonardo, Margalit and Percoco2024). Such long-term developments and short-term shocks, it is argued, create and exacerbate economic and, in particular, cultural conflicts that lead some voters to turn to parties on the far right in an effort to preserve the status quo (Betz Reference Betz1993; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), as a kind of ‘counter-revolution’ (Ignazi Reference Ignazi1992).Footnote 2

Instead of narrowing our interest to a specific policy or broadening out to examine economic and social changes that span decades, we focus on the control of political power and its effect on far-right success. Does the electoral success of the far right depend on which parties are in power? Does the far right gain more electorally when the left governs or when the right does? Despite the extensive public and scholarly debate around the potential for backlash, we still lack convincing empirical evidence that causally connects the increasing success of far-right parties to the power and influence of the parties in government (Rathgeb and Busemeyer Reference Rathgeb and Busemeyer2022). We know that the policy positions of mainstream parties matter for far-right success (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012; Meguid Reference Meguid2005; Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2019; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017) and that welfare state generosity can shape who votes for the radical right (Swank and Betz Reference Swank and Betz2003; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2019, Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022); however, there is to our knowledge no study of the effect of government ideology on far-right backlash. In this paper, we therefore seek to provide causal evidence on the impact that the partisan make-up of governments has on support for the far right.

Given existing research, we expect there to be greater behavioral backlash towards the far right under left-wing governments, and we argue that there are three possible mechanisms for this effect, based on attitudinal change, salience change, and strategic voting. First, ideological realignment: the implementation of left-wing policies may prompt conservative voters to react by shifting further to the right and adopting more radical political positions. This reaction can be understood as a defensive response to perceived ideological shifts in governance, reinforcing polarization and strengthening support for right-wing movements (Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019). Second, issue salience: left-wing governments and their policy agendas can increase the prominence of issues where the far right holds a comparative advantage over the mainstream right. These issues are often non-economic and culturally charged, such as immigration, national identity, or law and order. By elevating the public’s attention to such topics, left-wing policy making may create favorable conditions for far-right parties to mobilize support (Dahlström and Sundell Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012; Dennison Reference Dennison2020; Meguid Reference Meguid2005). Third, compensatory voting: the introduction of left-wing policies moves the status quo leftward, potentially leading even moderately conservative voters to seek more extreme right-wing alternatives as a strategic response. This compensatory behavior arises as voters attempt to counterbalance policy shifts and restore the ideological equilibrium closer to their preferences. In this context, the appeal of far-right parties may increase, as they present themselves as the most effective force to push back against perceived leftward drift (Bargsted and Kedar Reference Bargsted and Kedar2009; Kedar Reference Kedar2005).

In the first empirical part of our paper, we establish whether far-right electoral success differs depending on the partisan make-up of the preceding government. To do so, we first descriptively show the correlation between the ideological position of the incumbent and the subsequent electoral performance of the far right since 1945. We use the ParlGov database (Döring et al. Reference Döring, Huber, Manow, Hesse and Quaas2023) to provide comparative evidence across countries over time of the relationship between who is in government at time t and election results of the far right at time t + 1. This analysis shows clear and consistent evidence that the far right gains electorally when the government is to the left ideologically. However, this descriptive analysis does not allow us to make strong causal claims as methodological limitations apply; for instance, reversed causality (the formation of governments may be endogenous to the threat of a growing far right) or unobserved heterogeneity (certain contexts, such as long-term value shifts, may make left governments and stronger far-right parties more likely at the same time).

To lend credibility to our identification of the effect of government ideology on far-right success, we turn to a unique setting that allows us to estimate robust causal effects. Specifically, we examine how the ideology of local governments in Spain affects national vote shares in 2019, testing whether left-wing local mayors lead to a greater electoral success for Vox, a (then) new far-right party. In Spain, local governments have extensive competencies and also take stances on ‘cultural’ issues, for instance by organizing local festivities or raising flags in front of the town hall building. Spain constitutes a particularly suitable case for our study: not only do local authorities wield significant policy-making powers, but Spain also exemplifies broader trends in advanced democracies, namely increasing party system fragmentation, rising political polarization, and the emergence of electorally competitive far-right parties, with Vox providing a paradigmatic example. To make plausible causal inferences, we use data from close races where the likelihood of left-wing mayors (and thus policies) discontinuously changes when the main conservative party wins/loses elections by a narrow margin. Through a regression-discontinuity approach, we show that Vox support increased by approximately 4–5 percentage points (≈1 standard deviation) when the left held the mayoralty in the municipality. This provides quasi-experimental evidence that exposure to left governments and policies at the local level raises support for the far right at the national level.

While this analysis provides strong evidence for a far-right electoral boost under left-wing governments, it leaves us with little understanding of what it is about the left being in government that drives this pattern. To examine this, we conducted an original survey in Spain to delve into the mechanisms underlying the relationship between the ideological slant of the incumbent government and the likelihood of voting for the far right. We ran this survey using a unique and original sample, confined to respondents living in municipalities that are close to the regression discontinuity design (RDD) cutoff in the aggregate-level study of Spanish election results. This sampling strategy allows us to provide causally robust, micro-level evidence on the mechanisms through which the main effect takes place. Our results point to ideological realignment: voters display more right-wing attitudes on key relevant issues when the left is in power locally. We find no consistent evidence that issue salience or compensational voting matter in our case.

Our overall findings are clear: the ideological composition of the preceding government has an impact on far-right electoral success. Specifically, far-right parties benefit electorally when the left governs, as shown in our descriptive cross-national evidence and our RDD analysis of Spanish municipalities. Our unique individual-level survey indicates that this effect is mainly because some voters move to the right when the left governs. Studying this question tells us in which contexts the far right tends to benefit.

Four aspects related to our paper deserve to be highlighted here. First, our question is not answered by reference to standard thermostatic models of politics (Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995), where policy change in one direction leads to public demands for adaptation and reform in the opposing direction. Instead, we focus specifically on far-right parties, that is, on radical actors that pose a threat to democratic stability, and ask when and why these parties are more likely to experience electoral gains, pointing to three potential mechanisms: ideological realignment, issue salience, and compensational voting. Second, our ambition is to provide broad, generalizable insights into the conditions that are more conducive to far-right success, so we acknowledge that parties govern under very different circumstances and arrangements, and the policies they implement may also diverge for reasons beyond their ideological leanings. Third, while our theoretical focus is on the political consequences of left-wing incumbency, our estimated effects are necessarily relative to a counterfactual of a non-left-wing government. As a result, the findings may reflect a heightened reaction to left-wing governments, but also comparatively lower far-right support under mainstream right incumbents. Finally, our research question does not allow us to assign blame for far-right success to either the mainstream left or the mainstream right. The reason for far-right electoral gains during left-wing governments may, for instance, also lie in the ineffectual or radicalizing reactions of the mainstream right.

In the conclusion, we reflect on further work that needs to be done to shed more light on the connection between governments’ ideology and the success of the far right as well as on the mechanisms that underlie this link. We also discuss what our results mean for explanations of the rise of far-right parties, and for what mainstream actors can do to prevent such developments.

Government Partisanship and Far-Right Success

In recent elections, many advanced democracies have seen a significant increase in support for the far right (Valentim Reference Valentim2021). In the last ten years, countries as diverse as Germany, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden have seen a stable, large far-right party emerge, while these parties have governed in countries such as Austria, Finland, Hungary, and Italy. These developments reflect a substantial shift in the patterns of party competition. Consequently, far-right party success has been a core concern of political science research in the past decades. Theories of its rise span the range of social scientific approaches, with the emergence of the far right linked to factors ranging from deeper social and economic transformations on the one hand to short-term political tactics on the other (Golder Reference Golder2016).

Our starting point in this paper is the phenomenon known as backlash, a process in which societal events or developments prompt certain voters to shift their political preferences and gravitate towards more radical parties. This dynamic often manifests as increased support for far-right parties and their anti-immigrant, nativist, and authoritarian stances.Footnote 3

A key strand of research studies how changing voter preferences result in far-right success. Some authors take a long-term perspective on this process of attitudinal change. For instance, Ignazi (Reference Ignazi1992) and Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) focus on the gradual, value-based changes in many societies that lead voters to shift their support to the far right. Other works focus more on longer-term economic and socio-structural change and how this affects voting behavior (Anelli et al. Reference Anelli, Colantone and Stanig2021; Baccini and Weymouth Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018).

Other research, more related to our own, implies that the actions taken by governments can impact the subsequent popularity of far-right parties. So, our research is most closely aligned with work that examines the short-term effects of particular events and policies on far-right success. The thermostatic model of politics thus posits that voters react to government policies, shifting away from the current direction of travel (Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995). If public policy changes, voters’ relative preferences tend to shift away from that change (Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). Other work focuses on how government policies lead to far-right success. These policies can be economic, such as austerity (Hübscher et al. Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2023), welfare state generosity (Vlandas and Halikiopoulou Reference Vlandas and Halikiopoulou2022), or climate change mitigation (Colantone et al. Reference Colantone, Di Lonardo, Margalit and Percoco2024), but they can also relate to cultural matters such as minority rights or gender equality (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024; Bustikova Reference Bustikova2014). Yet such reactions to policy change are by no means universal: not every societal change is met by an equivalent reaction in the opposite direction (Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Kustov Reference Kustov2023).

Overall, we follow this strand of research by asking how governments differ in their impact on far-right success. Yet, our perspective is broader, as we ask whether the ideological composition of a government, that is, whether it is situated on the left or the right, is more likely to lead to far-right electoral success. It is important to reiterate here that our aim is to identify the contexts in which the far right flourishes. An important aspect of this is that, when the left governs, the right is in opposition and vice versa. So, for instance, if the far right achieves greater electoral success when the left governs, then this might also be due to the ineffectual nature of the mainstream right in opposition or its greater willingness, when out of power, to accommodate the far right.Footnote 4

While our approach focuses on the effects of governments, there is also related research that looks at how the broader party system influences the rise of the far right. For example, party system convergence may lead to party system polarization (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012; Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2019). The argument is that mainstream parties sometimes end up taking similar positions on key issues, ranging from welfare state reform and budgetary politics to immigration and European integration. In this context, radical alternatives become attractive to voters who do not share these centrist positions. When it comes to policy convergence, particular emphasis is placed on mainstream left parties, who are seen as having moved more towards the positions of the mainstream right than vice versa, especially on topics such as working-class representation and austerity (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012; Hübscher et al. Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2023). When the left governs, they may often have to make painful compromises. Research on austerity suggests that voters dissatisfied with converged policy proposals by mainstream parties may often reach for a radical alternative, either in a desire to affect specific policy outcomes or simply to register broader dissatisfaction with political elites (Hübscher et al. Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2023).

Relatedly, recent research goes beyond a one-dimensional Downsian framework to explain far-right success. Two-dimensional conceptions may capture more accurately the dynamics of party competition and voting behavior. While a one-dimensional conception of party competition means that radical left parties should benefit from perceived mainstream party convergence, a two-dimensional approach implies that some voters, especially left-authoritarians with left-wing economic but authoritarian cultural views, may also defect to the far right (Gidron Reference Gidron2022; Lefkofridi et al. Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014). Moreover, since the seminal work of Meguid (Reference Meguid2005), it has been clear that far-right success also results from the political strategies of competing parties on the left and right. A simple Downsian model would predict that far-right vote shares would go down if other parties move towards that party – especially those proximate to the far-right party. This straightforward prediction has inspired significant research. However, on balance, the evidence does not seem to provide evidence in favor of this prediction (Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Cohen and Wagner2022; Abou-Chadi et al. Reference Abou-Chadi, Mitteregger and Mudde2021; Valentim et al. Reference Valentim, Dinas and Ziblatt2025), even if there are also contrary findings in Spoon and Klüver (Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) and Hjorth and Larsen (Reference Hjorth and Larsen2022). The work of Meguid (Reference Meguid2005) provides an explanation for why accommodation may fail to reduce far-right success, as such strategies may only serve to heighten the salience of issues owned by the far right, especially if the left also takes an adversarial stance.

Indeed, it has also been suggested that far-right parties may be legitimized and strengthened on purpose by some competitors, perhaps resulting from strategic miscalculation. In Meguid (Reference Meguid2005), left parties strategically empower radical-right parties to undermine their right-wing competitors. Conversely, Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2017) presents an alternative viewpoint, by which the other right-wing parties are the ones that have more impact on radical parties’ success. His argument is that the accommodative behavior of right-wing politicians was crucial in determining the fate of authoritarian right-wing movements in Europe’s pre-World War II democracies.

Overall, there is work showing that government policies, party systems, and party strategies matter for far-right success. To date, this work has examined the effects of specific policies, the developments within party systems, and the behavior of individual parties. In this paper, we instead focus on the ideological make-up of governments and examine whether the far right does better when the left or the right are in power and implements their preferred policies. We suggest that exposure to left-wing governments can create backlash, in that far-right parties benefit in subsequent elections. As past research shows, the reasons for this may not be a simple one-dimensional thermostatic reaction to left-wing governments and their policies. We now turn to describing more specifically the ways in which contexts in which the left governs may be propitious for far-right success.

Potential Mechanisms Underlying Backlash Effects

We consider three mechanisms to be the most plausible in underlying potential backlash effects: ideological realignment, issue salience, and compensation. Importantly, only the first involves actual attitudinal change among voters, while the second and third imply shifts in issue prioritization and strategic considerations, respectively.

The primary and most salient mechanism of backlash is ideological realignment, wherein the ideological positions of certain voters shift in response to the policies implemented by left-wing governments. Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) provide empirical evidence of a backlash effect, demonstrating that voter polarization intensifies when the far right experiences electoral success. This effect is partly attributable to left-leaning individuals radicalizing in reaction to the gains made by far-right parties.

With regard to the electoral success of the far right, existing research suggests that such outcomes may emerge as an ideological response to broader societal transformations and political events. These may be long-term changes, such as in Ignazi (Reference Ignazi1992) and Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), or short-term reactions, such as in Bustikova (Reference Bustikova2014). More broadly, policies enacted by left-wing governments could contribute to increased ideological and issue-based polarization within the electorate. As a consequence, some right-leaning voters may become more inclined towards radical positions, perceiving the far right as a more compelling alternative to the moderate positions of traditional right-wing parties. This process of ideological polarization, driven by left-wing governance, ultimately fosters conditions that facilitate electoral gains for far-right movements. Conversely, under a mainstream-right government, ideological reactions should theoretically undermine the far-right’s electoral prospects, as right-wing voters would be less incentivized to seek more radical alternatives.

A second possible mechanism relates to issue salience. Far-right parties benefit when topics relating to the so-called ‘second’ dimension become central to party competition, be it due to external events or conscious party strategies (Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023; Margalit Reference Margalit2019; Meguid Reference Meguid2005). Again, this mechanism points to periods of left governments as the more likely context for far-right success. During periods of left-wing governments, the public agenda may increasingly center around second-dimension cultural issues, as these administrations often face structural and institutional constraints that limit their ability to implement expansive economic policies (Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019). Moreover, left-wing parties often have an agenda that focuses on reforms, often controversial, on areas such as gender equality and LGBTQ+ issues, among others (Hildebrandt Reference Hildebrandt2016). Implementing change will likely increase the salience of these policy areas, more so than maintaining the status quo. The increased salience of second-dimension issues may also come from right-wing parties, who could react to being out of government by trying new tactics, perhaps shifting attention to new issues (Hobolt and De Vries Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015). We argue that if the issue agenda systematically moves towards cultural issues when the left governs, this could favor far-right over mainstream-right parties (Bustikova Reference Bustikova2014), as the former hold more popular positions on these topics than their ideological counterparts. Importantly, here the backlash is expressed electorally through far-right success, but voter preferences themselves have not become radicalized.

A final potential mechanism refers to the possibility that voters react to left-wing governments following a logic of compensational voting. Left-wing governments and the policies they implement are likely to make voters perceive the status quo as moving to the left (Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995). In response to these perceptions, voters may search for a way to move the status quo closer to their own ideal point. The compensational model of vote choice suggests that, in response to this shift in the status quo, some citizens may re-calibrate their vote, opting for the far right as a more effective means of moving the status quo closer to their own position, even if the far right is more extreme than they themselves are (Bargsted and Kedar Reference Bargsted and Kedar2009; Kedar Reference Kedar2005). In essence, this mechanism underscores how shifts in the political equilibrium, induced by left-wing governments, can lead to strategic choices on the part of voters that mimic the effect of an ideological reaction. As in the second mechanism, the left-wing governments thus do not necessarily lead to a change in terms of voters’ policy preferences, but there is nevertheless a shift towards more radical actors in terms of vote choice.

Overall, the tenure of a government applying left-wing policies can have three important effects: voters move to the right on key issues; voters see cultural topics as more salient; and voters perceive the far right as a strategic choice to change the status quo. Put simply, left-wing governments might generate reactions among voters from which far-right parties benefit – a backlash. We now turn to examining, empirically, when far-right parties experience greater electoral success.

Comparative Evidence

We first study the effect of the ideological position of the government on support for the far right using comparative evidence across countries over time. To do so, we use ParlGov data (Döring et al. Reference Döring, Huber, Manow, Hesse and Quaas2023) from all EU countries and most OECD democracies (thirty-seven countries), from 1945 to 2021.Footnote 5 To measure support for the far right, we use ParlGov’s classification of parties into eight party family categories: Communist/Socialist, Green/Ecologist, Social democracy, Liberal, Christian democracy, Agrarian, Conservative, and right wing (Döring Reference Döring2016).Footnote 6 For each of the 710 democratic elections in the dataset (specifically national and European parliamentary contests), we add up the vote shares of nationalist, fascist, and radical-right populist parties.Footnote 7 This is our outcome variable.

To measure the ideological position of the previous government, we calculate the average left–right score of all the parties that were members of the government immediately preceding elections, weighted by their seat share contribution to the cabinet. We take the left–right position for each party from a time-invariant unweighted average of left–right scores from party expert surveys on a 0–10 scale compiled by ParlGov (Döring et al. Reference Döring, Huber, Manow, Hesse and Quaas2023).Footnote 8

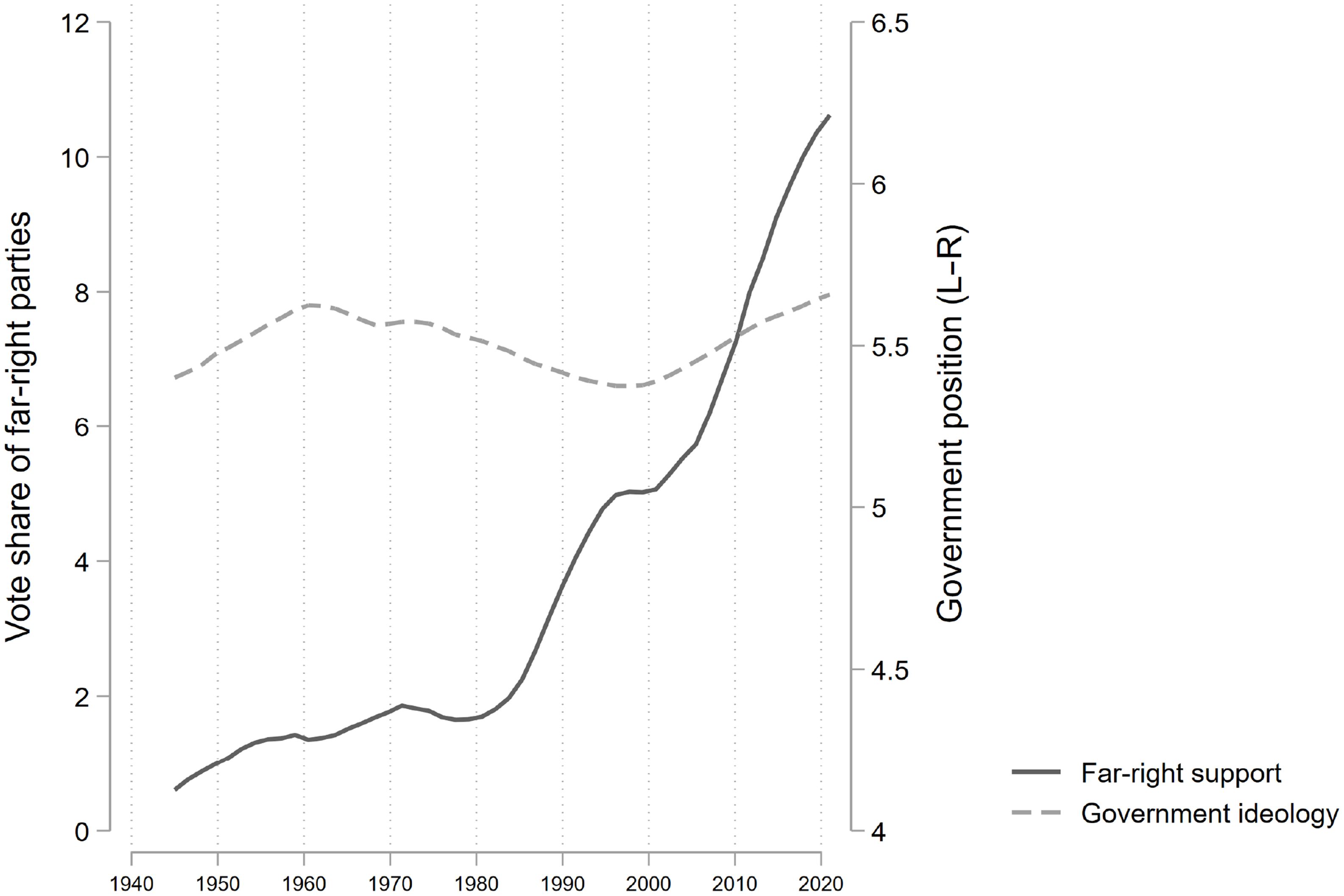

In Figure 1 we show the evolution of far-right election results and government ideology from 1945 until 2021, employing the measures described above. For this plot, we chose to include all available data for each year, so the countries included vary over time, and thus the averages presented necessarily hide a lot of heterogeneity across countries. Nevertheless, the plot shows that the pattern in support for the far right is clear: low and largely stable from the 1940s to the 1980s, and surging since then up to more than 10 per cent of the total votes. The ideological position of governments has also changed over time. On average, while relatively stable, governments shifted to the left in the 1940s and 1990s and moved rightward between the 1950s and 1970s, as well as since the 2000s.

Figure 1. Evolution of far-right support and government ideology over time.

Note: Far-right support is calculated as the sum of vote shares of all far-right parties in each election and government. Government ideology is measured as the average left–right position of all cabinet parties in the government in power when elections were held, weighted by seat share. Values are averages of all the available elections for each year.

To further study the connection between government ideology and support for the far right, we estimate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models of the following form:

In this model FRSupport t, i is the sum of the percentage of votes obtained by far-right parties in election t and country i, FRSupport t − 1, i is the lagged dependent variable, and PrevGov(L−R) t − 1, i is the seat-share weighted average left–right position of the parties that were members of the cabinet in power when election t was held in country i. In some specifications, we also include a vector of year fixed effects λ t and country fixed effects γ i to account for any remaining heterogeneity over time and across countries that might affect the relationship between the ideological position of the government and the election results of the far right. We hence take advantage of variation over time within each country, net of potential country time-invariant and other temporal-specific confounders. Finally, u t, i refers to the error term.

We exclude caretaker governments from all the analyses and run the models in different samples: a full sample containing all countries and years, and restricted samples only considering (i) parliamentary democracies and (ii) West European countries.

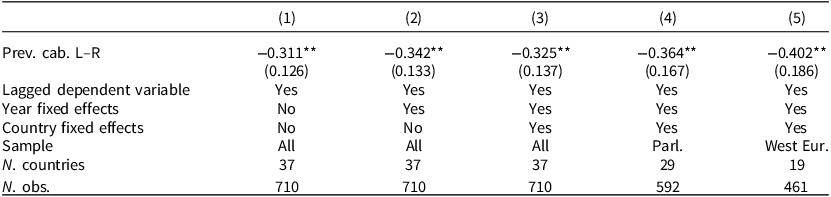

Table 1 summarizes the results from our analyses. The effect of left–right position is consistent across specifications, with right-leaning governments leading to a lower vote share for the far right in the next election. Support for the far right, therefore, seems to increase under left-leaning governments.Footnote 9

Table 1. Effect of previous cabinet ideology on far-right support (comparative evidence)

Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Note: OLS regression estimates. The outcome variable is the percentage of votes obtained by far-right parties. The key independent variable Prev. cab. L–R measures the position of the cabinet immediately preceding the election in a 0 to 10 left–right scale. Complete regression estimates in Appendix Table D1.

The magnitude of the association between the vote share of far-right parties and the ideological position of the previous government is illustrated in Figure 2. The predicted electoral support for the far right when a right-wing government was in power (positioned at 7 in a 0–10 left–right scale) is less than 4 per cent, but this share is around 1.5 percentage points higher if elections were held under a left-wing incumbent government (positioned at 3). The magnitude of the effect is remarkably consistent whether we focus on the full sample, parliamentary democracies, or West European countries.

Figure 2. Predicted far-right support after left-wing v. right-wing government (comparative evidence).

Note: Estimates from models 3, 4, and 5 in Table 1.

These results suggest that contexts where the left is in power are fertile ground for far-right parties, which fare better in elections under a left-wing government than under a right-wing one. However, even if the fixed effects by country and year included in our estimations account for some potential confounders of this effect, there could still be heterogeneity between contexts where the left or the right is more likely to govern, and this might at the same time have an impact on the electoral prospects of the far right. We therefore take the above results as descriptive evidence suggestive of a relationship between left-wing governments and far-right success, across a large number of democracies over time. In the next section, we aim to obtain a well-identified estimation of this effect, moving to the local politics of Spain as a testbed.

RDD Evidence from Spain

To enhance the credibility of our estimates of the causal effect of left-wing governments on support for the far right, we now concentrate our analysis in the case of Spain in the late 2010s, which provides an excellent testbed for our research question. This was a period of electoral flux in Spain, as Ciudadanos and Podemos had broken through in the early 2010s, in the aftermath of the economic and financial crisis. However, Vox’s success was a sea change in Spanish democracy: no Spanish far-right party had achieved any significant electoral success until late 2018, when the party obtained 11 per cent of the vote in the regional elections of Andalusia. Support for Vox then quickly surged countrywide, at a time when the main Spanish center-left party, PSOE, had recently taken over the central government through a vote of no confidence, thanks to the support of a myriad of progressive, regional, and pro-independence parties. This case thus provides a great opportunity to test the backlash hypothesis in a context where an electorally successful far-right party was emerging, in a country that had long been considered exceptional in its lack of a competitive radical right contender.

More specifically, we focus on the Spanish local level. The local political context in Spain offers three unique characteristics that are advantageous for our research design: electoral rules that create strong discontinuities in the probability of governing based on narrow differences in vote share; local governments with strong competencies that create tangible ideological differences; and, in 2019, an emerging far-right party, Vox, which had had virtually no representation before. Also, by focusing on the formation of local governments within a single country, we achieve two important objectives: (1) obtaining a substantial number of observations that provide adequate statistical power, and (2) effectively controlling for various potential confounding factors – such as institutional and cultural influences – that could affect the government formation process (Laver et al. Reference Laver, Rallings and Thrasher1987).

The first reason why Spain’s local governments provide a great testbed lies in their unique electoral system, in which narrow differences in vote shares between the two largest parties create large differences in the probability of leading the local government. Spain operates under a strongly decentralized political system with three tiers of government: national, regional, and local. Citizens elect local councils every four years in over 8,000 municipalities for a fixed term, employing a closed party list proportional representation (PR) system.Footnote 10 The PR system frequently generates situations where no single party holds an absolute majority of seats in the council. This triggers a negotiation period among the represented parties to elect the mayor, akin to the government formation process in traditional parliamentary democracies where the government requires the confidence of the majority of the parliament. Then, an investiture vote takes place, invariably, twenty days after the election. Importantly, if no candidate receives an absolute majority of favorable votes, the leader of the party that obtained the highest number of popular votes becomes the mayor, without the need for further support from other parties and even when they will rule in a minority. Once the mayor is elected, she appoints the rest of the government, which can include members from the mayor’s party or other parties.

This means that the Spanish local electoral system favors the party that receives the highest number of votes in forming the government. In our identification strategy, we leverage this unique feature and focus on close elections in which the main right-wing party in Spain, the Partido Popular (PP), narrowly either won or lost. To instrument our treatment variable – the presence of a left-wing mayor – we employ the margin of victory or defeat for the PP.Footnote 11 Consequently, our key comparison is between municipalities where the PP barely lost (increasing the likelihood of a left-wing mayor) and municipalities where the PP barely won (reducing the likelihood of a left-wing mayor).Footnote 12

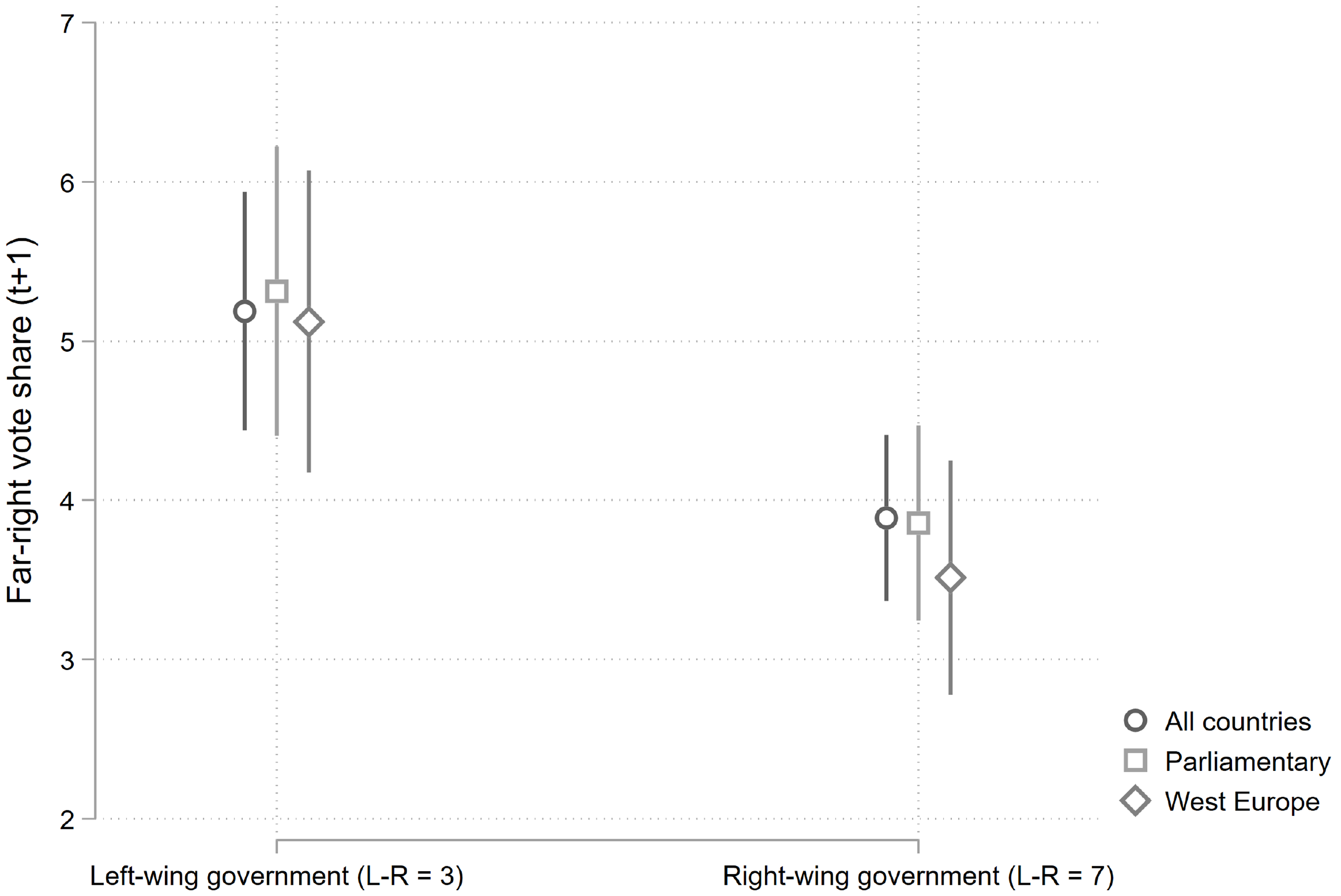

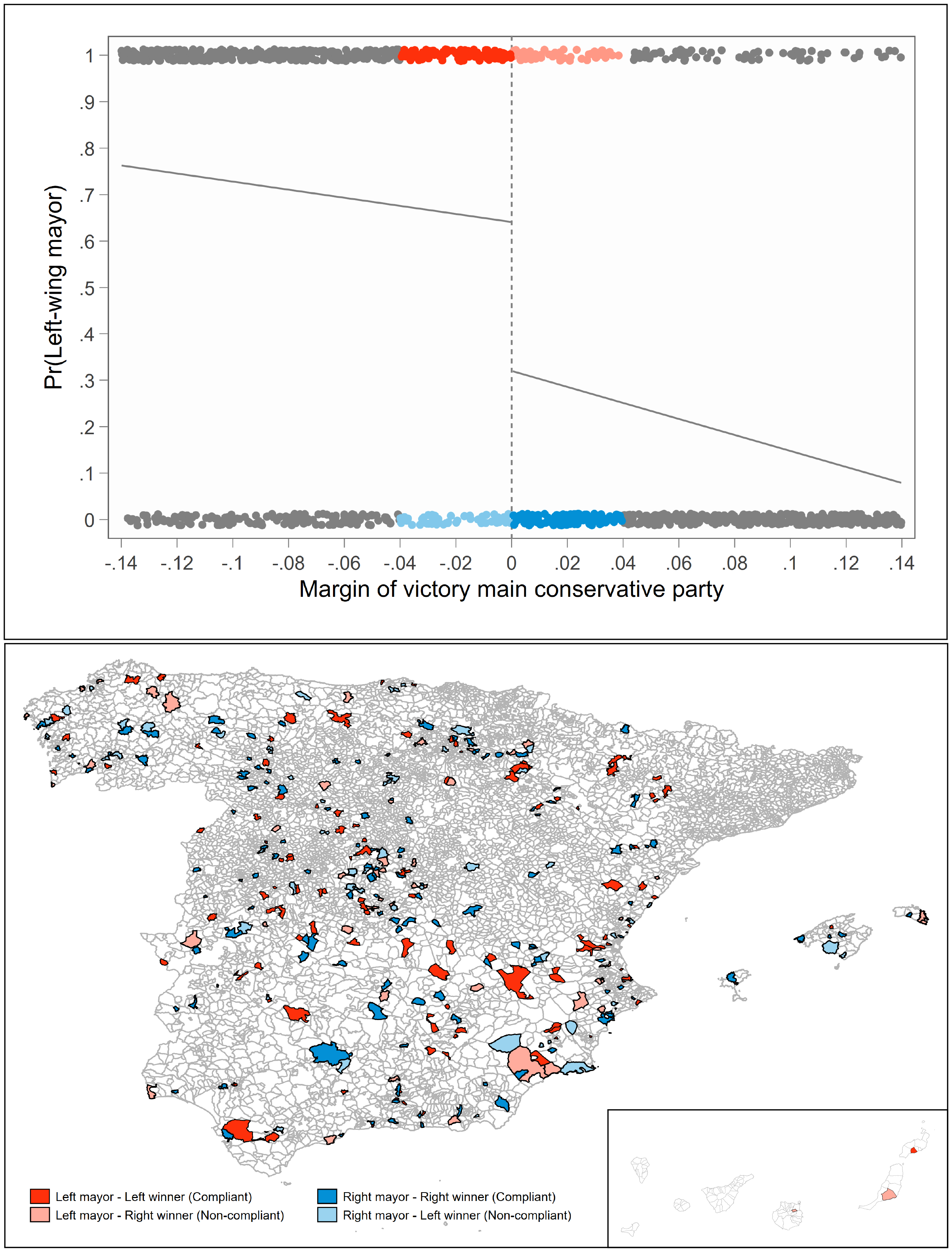

Figure 3 shows the first stage of this fuzzy RDD approach for the 2015 local elections. This plot confirms the strength of the instrument: there is a 32 percentage-point change in the likelihood of having a left mayor for the 2015–19 term, significant at p < 0.001. Covariate balance around the cutoff and manipulation tests uphold the continuity assumption behind our RDD approach (see Appendix B.1).

Figure 3. First stage (instrument strength).

Note: The outcome variable takes value ‘1’ when the 2015–19 mayor belongs to a left-wing party and ‘0’ otherwise. The forcing variable is the margin of victory of the mainstream right party (PP) in the 2015 local elections. Local linear regression estimates use a uniform kernel.

Second, the decentralized nature of the Spanish political system means that local governments have extensive powers and competences, with the major budgetary items corresponding to responsibilities on environmental services, urban planning, transport, and welfare and social services. They can also provide other services in areas such as education, culture, gender equality, housing, health, and environmental protection (Solé-Ollé Reference Solé-Ollé2006). Moreover, the influence of local governments is not just in local service provision: they are responsible for the organization of local festivities that, in the context of Spain, are very significant and even have electoral consequences (Guinjoan and Rodon Reference Guinjoan and Rodon2021), as well as other highly visible actions, such as (not) showing certain banners or flags in front of the town hall building. Hence, (1) Spanish local governments are relevant, salient, and well-known by citizens (as suggested by an average turnout rate above 70 per cent in local elections and the amount of media attention they receive); and (2) they can and do make programmatic economic and cultural policies that can be easily identified as left wing. Examples of these may include bike lanes, recycling schemes, feminist cultural events, rainbow flags, or ‘welcome refugees’ banners, among many others.

The fact that local governments in Spain have extensive powers means that ideological differences in the parties heading the local government result in ideologically distinct policies that are consequential for citizens’ lives. In some sense, they can make left-wing or right-wing policies very visible in a citizen’s daily interactions. Citizens will be exposed to these different policies, with a potential impact on their political preferences and voting behavior above and beyond local elections.

Finally, the Spanish case provides a suitable electoral setting to measure the impact of government ideology on far-right support. Specifically, we examine support for Vox at the local level in the 2019 general elections. These were the first nationwide elections in which the party emerged as a viable contender. The first general election that year took place in April, after the entire local-level term starting in May 2015 had elapsed, but shortly before new local elections were held in May 2019. In the April 2019 elections, Vox received 10.3 per cent of the nationwide vote, compared to 0.2 per cent in both 2015 and 2016. The timing of these elections provides a unique opportunity to measure the countrywide level of support for the far right at the municipal level towards the end of the term of the local government, after the policy record of incumbent local government was set. At the same time, the measurement of far-right support using this strategy is not contaminated by local political dynamics such as the decision of the far right to run or merge with other party lists in some municipalities but not in others, decisions that could be endogenous to the incumbent local government. No other election year provides such a methodologically convenient context.Footnote 13

We focus on the national election because Vox only ran in approximately 10 per cent of the municipalities in the local elections held in May 2019. This was likely due to the party’s limited organizational structure and territorial presence at that time. Hence, an alternative empirical approach, focusing on Vox’s electoral success in the municipal elections, is not feasible for our study. Instead, we use Vox’s level of support in the 2019 general elections, measured at the local level, as an indicator of far-right support. Importantly, data for all Spanish municipalities are available for this election, allowing for a comprehensive analysis. Note also that this methodological choice does not imply that voters use general elections to hold local governments accountable. Instead, we contend that different local incumbents expose citizens to truly different policies that may affect their general political orientations, which we measure for all municipalities and with the best available data. In any case, the use of local governments as our treatment should provide, if anything, a conservative estimate of the effect we are interested in.

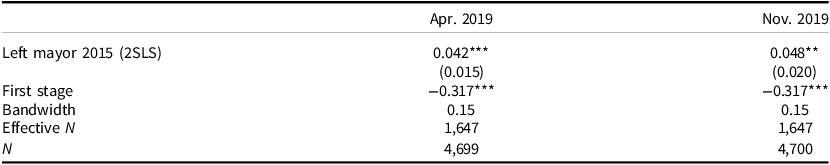

Turning to the results of our analyses, Table 2 provides evidence of the main effect we are interested in. We see that support for Vox is between 4 and 5 percentage points higher in absolute terms in municipalities with a left-wing mayor (instrumented with a narrow defeat by the PP). This is a very strong effect: as much as one standard deviation of Vox’s share of votes across municipalities (recall that the national vote share of Vox in these elections was 10.3 per cent in April and 15.1 in November). The effect is therefore both substantially and statistically significant.Footnote 14

Table 2. Effect of left-wing mayor (2015–19) on support for Vox (2019)

Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Note: The outcome variable is Vox’s share of votes in the general elections of 2019. The forcing variable is the margin of victory of the mainstream right party (PP) in the 2015 local elections. The treatment takes value ‘1’ when the 2015–19 mayor belongs to a left-wing party and ‘0’ otherwise. Local linear regression estimates use a uniform kernel. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. 2SLS: two-stage least squares.

Complementary tests offered in the appendix confirm the robustness of the key finding. The result does not depend on the size of the bandwidth or the choice of weights for observations (Appendices B.2 and B.3, respectively). In addition, as shown in Appendix B.4, falsification tests corroborate that prior far-right support is not affected by government formation processes that occurred later. Finally, Appendix B.5 further shows that the main effect is driven by mainstream left and right incumbents, rather than by more extreme local governments.

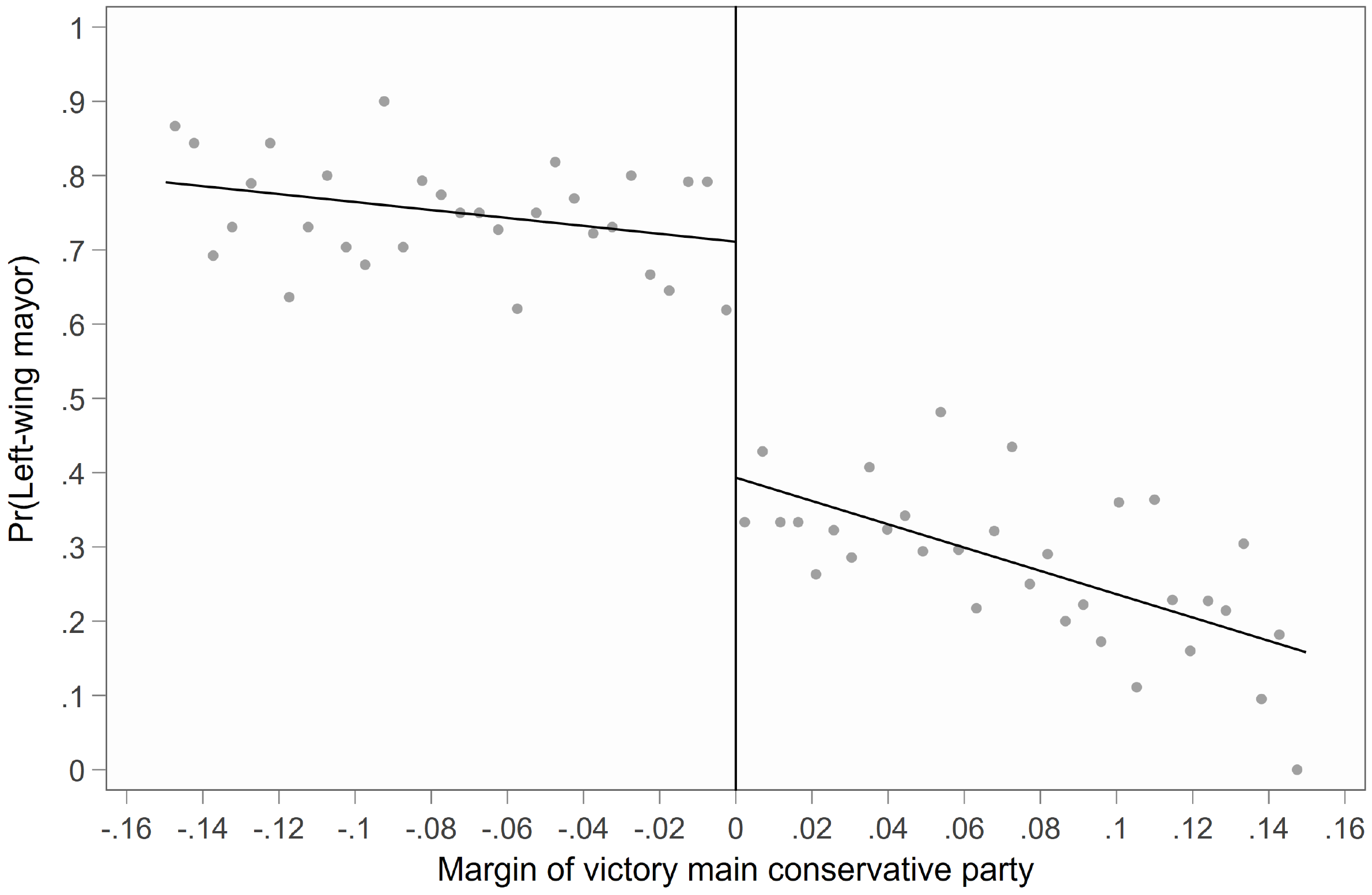

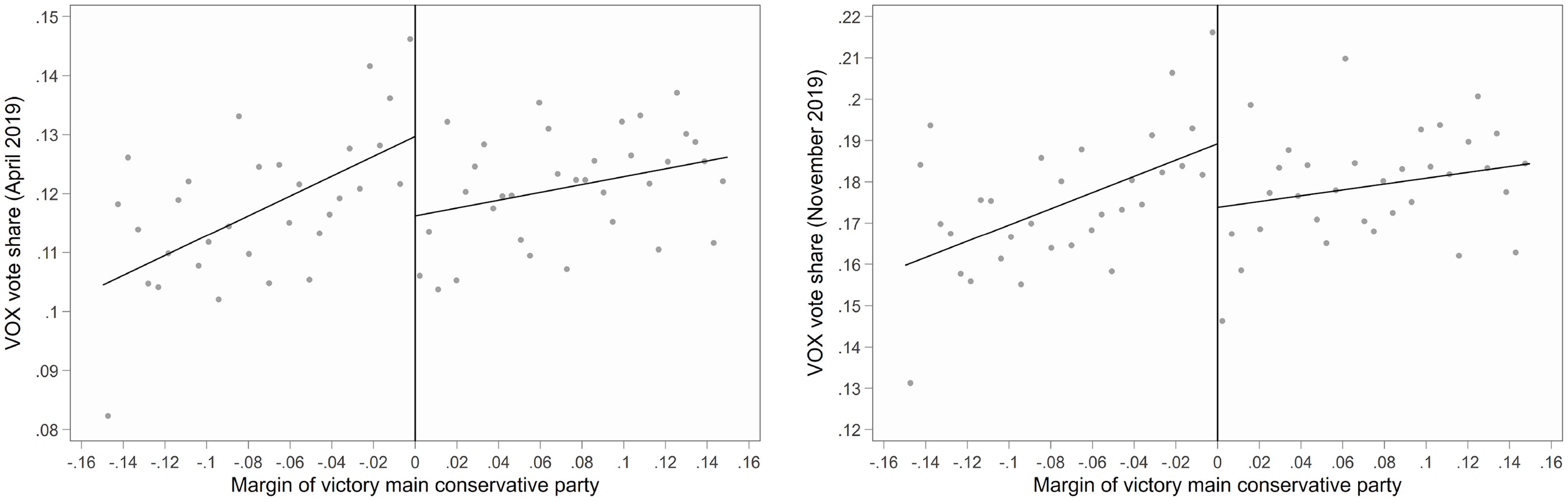

Further evidence of this effect can be seen in Figure 4, which shows the results of the reduced form of the instrumental variable approach (equivalent to a sharp RDD). The direct effect of a tight loss of the main conservative party is around 1.5 percentage points, both in April 2019, when Vox obtained 10 per cent of the votes nationwide (left plot), and in November 2019, when support for Vox increased to around 15 per cent.

Figure 4. Reduced-form (sharp regression discontinuity design).

Note: The outcome variable is Vox’s share of votes in the general elections of 2019. The forcing variable is the margin of victory of the mainstream right party (PP) in the 2015 local elections. Local linear regression estimates use a uniform kernel.

Interestingly, we find no systematic effect on the vote shares of other parties or on voter turnout, making it difficult to determine whether the main effect is driven by voters switching parties or by the (de)mobilization of certain groups of voters (see Appendix B.6). In the appendix, we also more explicitly examine whether backlash occurs symmetrically for the far left. Appendix B.7 shows that support for Podemos in the 2019 elections increases following the tenure of a right-wing mayor, though the effect is not statistically significant and remains much smaller than the backlash towards the far right that we analyze in this paper. Additionally, Appendices B.8 and B.9 show that the effect of left-wing mayors on far-right support does not differ meaningfully across municipalities of different sizes or levels of fiscal performance.

Lastly, we also explore the possibility that (part of) the main effect is driven by an overall reaction of voters in response to the mere fact that a left-wing mayor has assumed office, irrespective of the specific actions, projects, or initiatives undertaken by the government during its term. Appendix B.10 shows the results of the same fuzzy RDD, but this time employing the results of the May 2019 local elections – and subsequent government formation process – that took place shortly before the (repeated) general election in November 2019. The results suggest that voters do not exhibit an immediate response to the identity of the governing party that reached office just five months prior. Backlash, therefore, does not seem to occur automatically. Voters need some time to see the policies implemented by the local government for the backlash reaction to unleash.

Individual-Level Evidence

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the effect identified in the preceding sections, we supplement our findings with a third empirical approach: a pre-registered individual-level analysis of survey data.Footnote 15

Specifically, we conducted a survey in Spain to examine the relationship between exposure to left-wing governments and political attitudes. The survey was administered between 10 May and 24 May, just prior to the municipal elections held across Spain on 28 May, marking the conclusion of the 2019–23 local electoral term. This timing enables us to assess how exposure to a left-wing municipal government over the preceding four years influences various dimensions of the backlash introduced in our theoretical framework just before the election.

In particular, we test whether the partisan affiliation of the incumbent mayor in a respondent’s municipality is associated with their: (a) ideological positions on key issues (ideological realignment hypothesis), (b) perceptions of the salience of specific issues (issue salience hypothesis), and (c) beliefs regarding the status quo and the perceived utility of extreme alternatives for effecting change (compensational voting hypothesis).

To mitigate potential confounding factors in the relationship between local government composition and residents’ attitudes towards the far right, our sampling strategy follows the RDD approach outlined in the previous section. We surveyed respondents residing in municipalities that, within a small bandwidth, are situated just to the left or right of our RDD cutoff – this time based on the 2019 local elections. Specifically, we employ a margin of victory for the PP of ±4 percentage points, ensuring that we have a good number of municipalities that are also highly comparable in both observable and unobservable characteristics.Footnote 16 Figure 5 identifies the sampled municipalities, with those governed by left-wing mayors depicted in red and those with right-wing mayors in blue. Darker shades indicate compliant municipalities – that is, left-wing governments where the PP lost and right-wing governments where the PP won – whereas lighter shades represent non-compliant municipalities, where left-wing mayors emerged despite a PP victory and vice versa. The map reveals that these municipalities are widely distributed across Spain.Footnote 17 Overall, over two-thirds of our observations originate from compliant municipalities.

Figure 5. Regression discontinuity design (RDD) based sample.

In the survey, we incorporate a range of variables to examine the mechanisms through which backlash may occur. The first mechanism explores whether left-wing governments can provoke an ideological reaction. To assess this, we utilize six survey items that measure political positions on a ten-point scale. These items are divided into two categories: three pertain to economic stances along the left–right spectrum, while the remaining three focus on cultural issues.

On the economic dimension, we gauge respondents’ agreement with the following three statements: ‘The government should increase spending to enhance public services, even if it results in a budget deficit’; ‘Unemployment benefits should be reduced to incentivize job seekers to find employment’; and ‘Government regulations on companies should be decreased to stimulate economic activity’. All statements are recoded such that higher values reflect positions that are traditionally more right-wing. We sum the responses to the three questions to create a variable ranging from 0 to 30.

Similarly, on the cultural dimension, we create a cultural right–left variable by combining the responses to three statements relevant in the Spanish context: ‘Policies related to historical memory only serve to divide the Spanish people’; ‘At times, feminism has pushed too far in its pursuit of gender equality’; and ‘The government should implement more stringent measures to combat climate change’. Again, these statements are recoded so that higher values indicate a more right-wing stance.

We aggregate the scores from the economic and cultural dimensions to create an overarching measure of pro-right ideological positions. This composite measure offers a comprehensive evaluation of respondents’ right-wing ideology over issues that are relevant in the Spanish political agenda.

Second, the ideology of the party in government might affect how important citizens think different issues are, rather than shifting their ideological positions. To capture such issue salience, we ask respondents about the importance of a battery of issues using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘not important at all’ (1) to ‘very important’ (5). We create two variables: left issues salience captures the perceived importance of issues considered to be typically owned by the left in Spain (climate change, feminism, and historical memory), while right issues salience captures the perceived salience of three issues owned by the right (immigration, security, and Spanish unity); economic issues are not clearly owned by either the left or right, so the salience measure effectively focuses on cultural issues. Both variables are the sum of the salience attributed to each of the three corresponding items.

The third mechanism refers to whether backlash might come from voters using a more compensational logic when voting. This means that they would be more likely to vote for a far-right party to compensate for the fact that the status quo has moved to the left. We capture this with two variables. First, we asked respondents whether they agree with the statement that local politics in their municipality has become more radical. Second, we asked whether respondents believe that, in politics, it is necessary to be moderate to achieve what one wants. The responses to both statements range from ‘totally disagree’ (1) to ‘totally agree’ (5).

Having operationalized these three dimensions of backlash, we run three sets of models. In all specifications, the main independent variable is whether the local incumbent is a left-wing mayor. We instrument this treatment using whether the Partido Popular (PP) was the party with the largest vote share in the 2019 local elections, consistent with our main analyses using an RDD in the previous section.Footnote 18

For each dependent variable, the first model includes only the left-wing mayor treatment. In the second model, we add basic sociodemographic covariates: gender, age, and level of education. Our third and preferred specification includes additional controls: political interest,Footnote 19 political knowledge,Footnote 20 and vote recall in the previous 2019 general elections. As some of these variables could be considered post-treatment, we include them only in the final model to show that our results are robust to their inclusion.

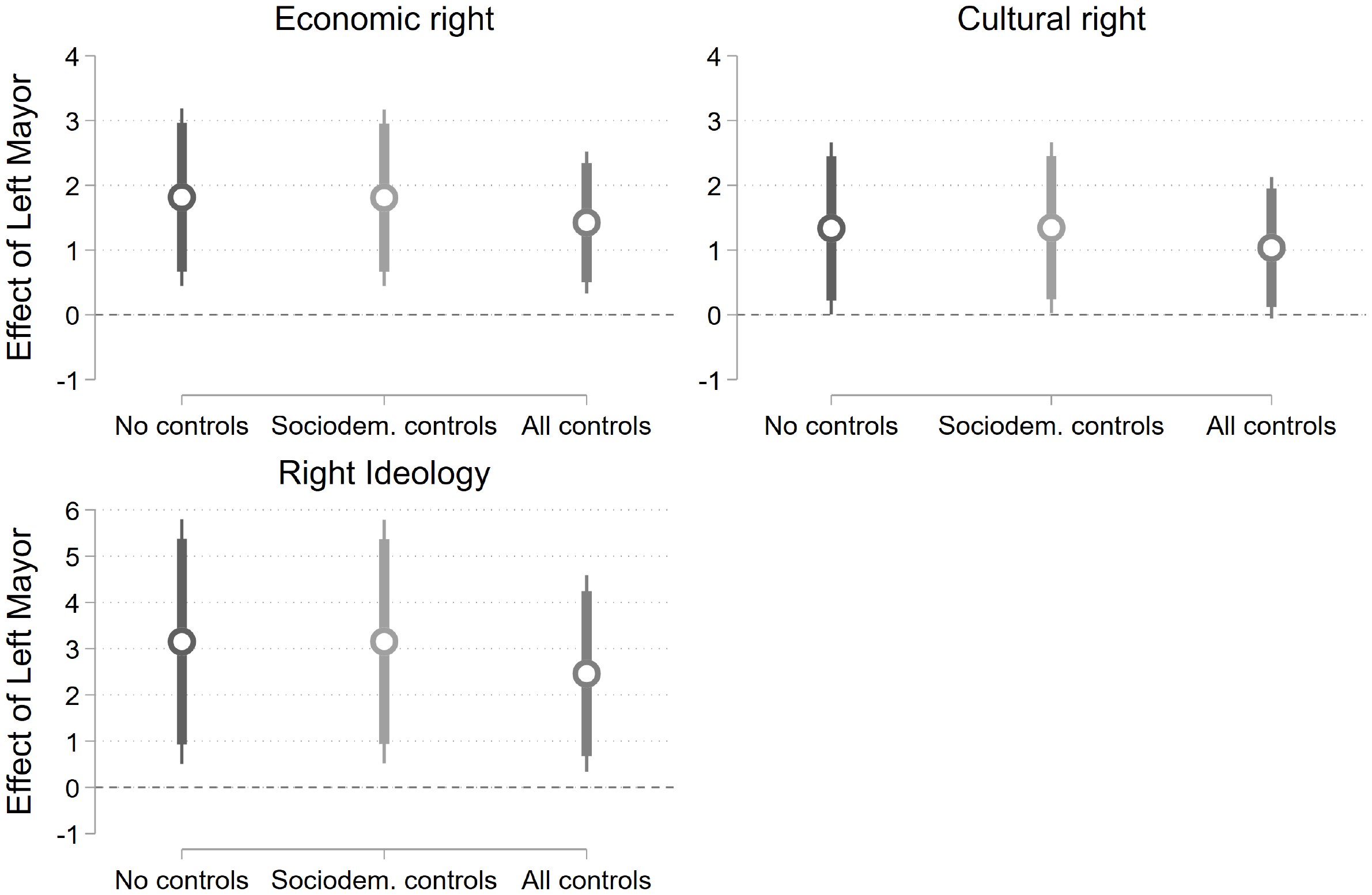

Results on ideological realignment are shown in Figure 6. We find systematic and robust evidence in favor of the first mechanism. Voters’ positions on the issues that divide the Spanish right and left shift towards the right in municipalities where there has been a left-wing mayor during the last four years. The effects are consistent across specifications both for economic and cultural issues as well as for the combined additive scale.

Figure 6. Ideological realignment.

Note: The outcome variable in the upper-left plot measures left–right positions over three economic issues (0–10 scale each). The outcome variable in the upper-right plot measures left–right positions over three cultural issues (0–10 scale each). The outcome variable in the bottom plot is an additive scale of economic and cultural issues. In all models, the independent variable is the presence of a left-wing mayor in the respondent’s municipality, instrumented with a narrow election victory/defeat of the main conservative party. Bars denote 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals. Complete regression estimates are in Appendix Table D2.

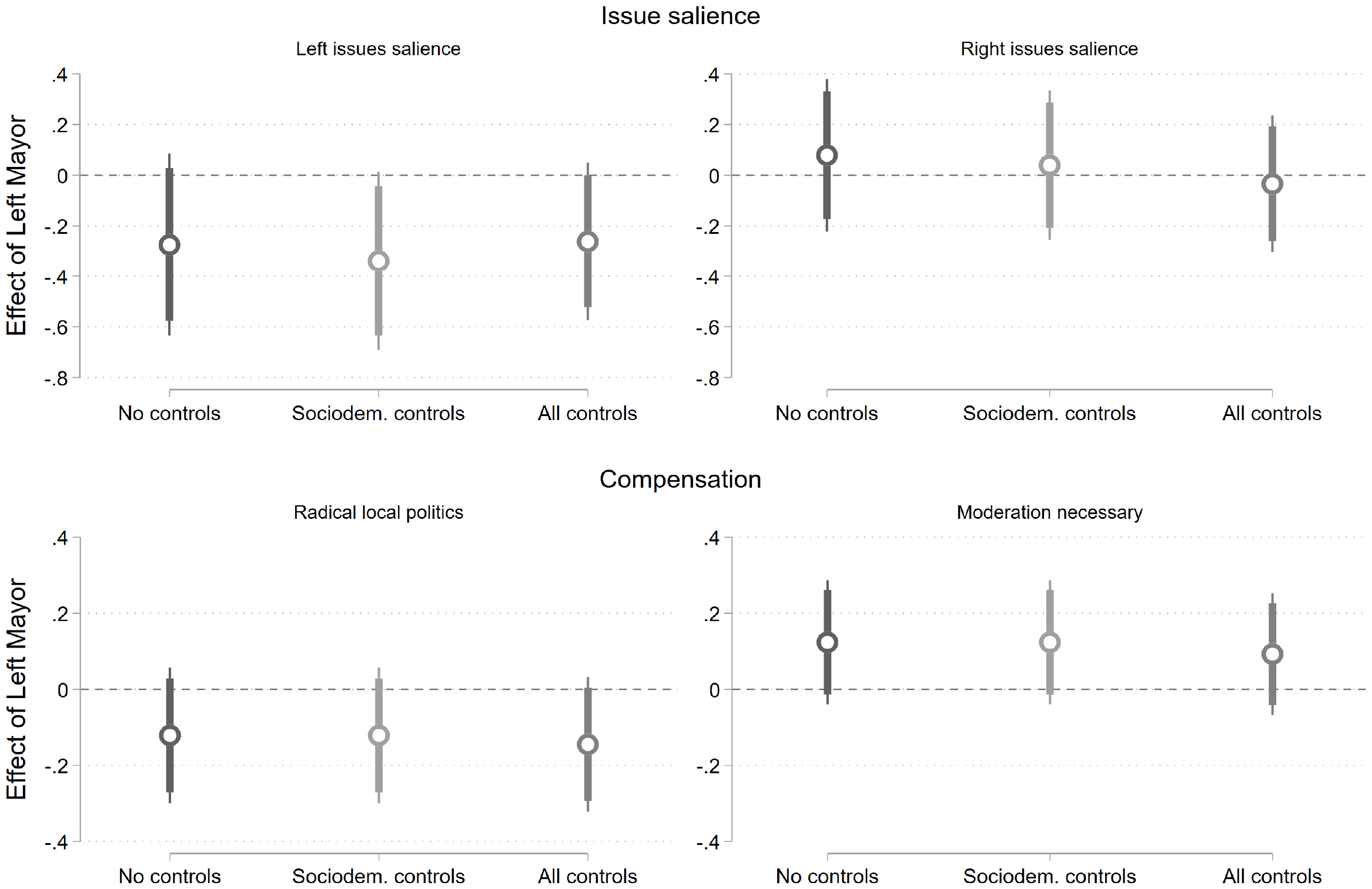

In contrast, Figure 7 shows limited empirical support for the remaining two mechanisms. Among the issue salience models, we find results approaching significance only in the models of left-issue salience. However, the effect goes in the opposite direction: left-wing local governments do not increase the salience of potentially backlash-inducing issues. Furthermore, when examining the salience of right-wing issues, we find no significant effects. In other words, we do not observe backlash in the sense of citizens assigning greater importance to issues on which the right traditionally holds a comparative advantage.

Figure 7. Issue salience and compensational voting.

Note: The outcome variable in the first two plots refers to how important respondents perceive three issues owned by the Spanish left (climate change, feminism, and historical memory) or right (immigration, security, and Spanish unity) to be. Each issue is scaled from 0 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). The outcome variables on the below plots are the degree of agreement with the statements that local politics in their municipality has become more radical or that in politics it is necessary to be moderate to achieve what one wants (1–5 scales). In all models, the key explanatory variable is the presence of a left-wing mayor in the respondent’s municipality. Bars denote 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals. Complete regression estimates in Appendix Tables D3 and D4.

The lower panel of Figure 7 shows that evidence for the compensation mechanism is also lacking. The coefficients are not significant and have inconsistent signs. While the effect of left-wing governments at the local level in the models that capture perceptions of radical local politics is negative, the coefficients of the perceptions that moderation is necessary to achieve things in politics are positive. In both cases, the coefficients do not reach conventional significance levels. Altogether, these models yield null findings, as citizens in municipalities with a close-margin left-wing mayor do not significantly differ in terms of the issues they see as important or their compensational motivations.Footnote 21

Overall, the individual-level data indicate that local left-wing governments in Spain generated an ideological realignment: on average, voters shift to the right in their position over some issues. This can, at least partially, explain the emergence and consolidation of the far-right option in Spain.Footnote 22

Conclusion

Our results provide support for the thesis that left-wing governments and policies lead to a backlash towards far-right parties. This is the finding of our large-n descriptive analysis that shows the correlation of far-right vote share and the ideology of the preceding government: the subsequent vote share of the far right is greater if the incumbent government is on the left. The same result is obtained in our RDD analysis of Spanish municipalities: those municipalities where the PP narrowly lost in 2015 witnessed a significantly greater Vox vote share in the 2019 national elections. Spain represents a particularly suitable case for this analysis, as local governments enjoy extensive competencies and also exemplify broader trends in advanced democracies, such as increasing fragmentation, rising polarization, and the emergence of electorally competitive far-right parties, with Vox as a paradigmatic example.

We also sought to explain why this pattern occurs, using a unique individual-level survey of Spanish voters in close-election Spanish municipalities. This complementary evidence allows us to validate the findings from the RDD design. The survey results suggest that when the Left governs, voters may undergo an ideological realignment and become more right-wing in their policy preferences. Other mechanisms of backlash, such as issue salience and compensational voting, found less support in this analysis.

Overall, this paper provides strong evidence for a backlash theory of radical party success. Far-right parties benefit more when the Left governs than when the Right does. In our study, this pattern emerges because of rightward ideological shifts among the electorate. Of course, other mechanisms – issue salience and compensation – may apply in other contexts. Future research should provide additional evidence on these mechanisms from other settings to generate a fuller account of why the far right benefits more when the Left governs. For instance, if backlash is created by perceptions of policy change in the electorate, future research should try to test whether actual policy change is a precondition for these effects, or whether mere perceptions of change suffice. Moreover, our results do not point clearly to either economic or cultural issues as the main driver of far-right success when the left governs.

For future research, while our comparative evidence suggests the backlash pattern may extend beyond Spain, it also remains important to examine how these dynamics vary across different party systems and whether the far-right challenger is a new or established political force. It would also be valuable to explore further whether a symmetrical backlash exists, wherein right-wing governments inadvertently contribute to the rise of radical-left movements. In our Spanish data, we found indicative, but weak, evidence of a shift towards the far left under right-wing incumbents. Examining in more detail and across contexts whether similar ideological shifts and electoral backlash occur in response to conservative governments could provide deeper insights into the broader dynamics of political polarization. Likewise, a more systematic investigation into the role of mainstream right parties – as both potential competitors or enablers of the far right – could clarify whether far-right gains stem more from a reaction to left-wing rule or from dynamics within the broader right-wing block.

In relation to this, our study raises the question of whether far-right parties’ success is the result of mainstream elite behavior and, relatedly, what can be done to prevent such backlash. We find a clear link between left-wing governments and far-right success. However, it would be a mistake to infer from this that the behavior of left-wing actors causes far-right surges. Indeed, this pattern could also be due to how other right-wing parties, finding themselves in opposition, react to electoral loss and diminished political relevance. While ideological realignment could be the result of a reaction to left-wing policy making, this shift could also be fostered by the rhetoric of mainstream right actors. This also means that far-right success may not be an inevitable consequence of left-wing governments, but that mainstream actors – on both sides of the political aisle – could do something to weaken this reaction among the electorate. This question deserves further attention in future work.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101208.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RI7FB7.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented in the EPSA Annual Meeting 2023, the University of Barcelona, and the University of Zurich. We thank participants, as well as Tarik Abou-Chadi, Daniel Bischof, Sandra León, Jordi Muñoz, Lluís Orriols, and Vicente Valentim for their generous comments. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used solely to improve language clarity and style. No AI tools were employed for data analysis, interpretation, or substantive content generation. The authors reviewed and take full responsibility for all content.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work and approved the final submitted draft.

Financial support

This work was supported by MICIU/AEI (AFG, grant number PID2020-120228RB-I00; IJ, grant number CNS2023-145677) and the European Research Council (MW, grant number 101044069).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

Ethical considerations are discussed in Appendix E of the supplementary materials.