Introduction

Conscription is one of the most powerful instruments of the state. It has shaped the composition of armies, influenced the outcomes of wars, and determined the fate of nations (Black Reference Black2007). Some citizens view conscription as a means of contributing to society, but others also see it as an immense burden. Indeed, conscription is among the most intrusive government policies, coercing young men into military service for an extended period of time. In times of war, as seen in the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict, conscription becomes a draconian measure, forcing citizens into battle, often under the threat of severe punishment for desertion.

Universal conscription emerged with the levée en masse in France around 1798 and spread across European nations throughout the 18th and 19th centuries (Black Reference Black2007, 186). In the United States, conscription (commonly referred to as the draft) has historically been used primarily during wartime. Although most European countries gradually abolished universal conscription in the 1990s and 2000s (Bove, Leo, and Giani Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024), it remains far from obsolete. In Ukraine’s war for survival, conscription is an existential necessity, while for Russia, it is a prerequisite for sustaining its full-scale invasion. Given these developments, conscription is likely to remain a topic of debate in Europe, even beyond the war.

Beyond its military purpose, conscription has historically served another crucial function, namely reinforcing the concept of citizenship. Since its inception, it has been closely tied to civic obligations: citizenship entails not only rights but also duties, including the responsibility to defend the state with your own body. When France introduced mandatory military service in the late 18th century, it was accompanied by the right to vote (Paret Reference Paret1992, 64), reinforcing the notion of civic loyalty to the state (1992, 73). Conscription may, also in modern times, instill a sense of responsibility and belonging to the state. Similar ideas inspired Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933 (Paige Reference Paige1985) and Macron’s Service national universel, introduced in 2021, decades after France abolished conscription in 1997. Macron argued that the program would allow citizens to connect and engage with their fellow countrymen and be a means of fostering ‘republican cohesion’ (Le Monde 2017).

A substantial literature examines the effects of voluntary military service, exposure to warfare, and wartime conscription on outcomes such as political attitudes, political participation, and forms of prosocial behavior (see, for instance, Braender and Andersen Reference Braender and Andersen2013; Grossman, Manekin, and Miodownik Reference Grossman, Manekin and Miodownik2015). However, peacetime conscription such as the programs currently considered in many European countries is different, and its effects cannot be assumed to be the same as voluntary military service or wartime conscription.

Empirical studies of peacetime conscription are typically based on comparisons of European cohorts with and without exposure to conscription and the conscription systems in Argentina and France. Choulis, Bakaki, and Böhmelt (Reference Choulis, Bakaki and Böhmelt2021) find that countries with conscription tend to have higher support for the military. Bove, Leo, and Giani (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) find across multiple European countries that cohorts exposed to conscription had less institutional trust than cohorts after conscription was abolished. Survey experiments and studies of the Argentinian conscription system suggest that conscription can affect public support for war, development of a ‘military mind-set’, increase turnout, and intensify sexist attitudes (Horowitz and Levendusky Reference Horowitz and Levendusky2011; Fize and Louis-Sidois Reference Fize and Louis-Sidois2020; Navajas, Gabriela, and Lópezand López Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022; Gibbons and Rossi Reference Gibbons and Martín2022). Some of these studies suggest that conscription policies may impose a civic penalty, in opposition to the classic idea that conscription will promote support of the state and its institutions.

The civic effects of conscription constitute important questions for countries that consider reintroducing universal conscription. Reintroducing or reforming conscription is currently on the table in countries such as Germany, Latvia, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands, and it is likely that other countries will follow. This raises a critical question: Will reintroducing universal conscription come at a civic cost? And if so, in what ways? Given its potential impact on citizens’ societal views, understanding the broader implications of conscription is essential.

To understand the societal implications of reintroducing conscription, we are interested in the individual-level, long-term effects of being conscripted on a broad set of civic outcomes. Our study aims to estimate the effects of being conscripted on outcomes such as national attachment, democratic participation, and political attitudes. If conscription produces lasting negative consequences, relying on conscription when designing the future territorial defense will constitute a dilemma for policymakers.

To investigate this, we use Denmark’s universal conscription system, which has been based on a randomized conscription lottery for able-bodied young men since 1849. We use individual-level register data on lottery results, combined with a survey of a sample of the participants in the conscription lottery. To observe the long-term effects, we survey lottery participants 15 years after their time as conscripts. To circumvent self-selection bias in the estimation, we examine the effects of being conscripted or not via the lottery (intention-to-treat analysis).

We find that conscription has no individual-level effects on national attachment, trust, and willingness to contribute to society. Among the broad range of civic outcomes, we find only positive effects on political interest, a small negative effect on one measure of authoritarian attitudes, and slight fluctuations in party support. In general, our results suggest that conscription has limited effects, and that universal conscription will not impose major civic costs on societies; nor will it substantially generate the positive effects expected by the civic arguments for conscription.

Conscription and civic outcomes

Being conscripted can be a transformative experience. For those who comply with the requirement to complete the service, it typically involves relocating to another part of the country, living in barracks at a military base, serving with fellow conscripts from different parts of the country and with very different socioeconomic backgrounds. Basic military training consists of activities such as physical training, classroom teaching, combat training, and deployment to military exercises. Recruits enrolled in the army, navy, and air force learn to operate weapons and study combat strategy. They experience discipline and comradeship and are taught that this is essential to military effectiveness and ultimately to their own and their peers’ survival. All this happens over an extended period, often between six months and a year, somewhat secluded from the rest of society, wearing a uniform with rank insignia, unit patches, and the national flag. The conscripts who do not comply with the service call-up can face sanctions in the form of fines, imprisonment, or other service requirements if they are not able to document a change in their health status that exempts them from service.

Universal conscription exposes a large share of the young adult male (and occasionally female) population to this massive intervention. As mentioned in the introduction, the historical purpose of universal conscription was not only military (although, of course, security and defense were vitally important and are the driving forces behind its reintroduction today) but also to affect civic outcomes. When conscription was introduced in France at the end of the 18th century, it helped build ‘awareness of the national community’ (Paret Reference Paret1992, 45) and was a channel ‘through which ideas, feelings, and energies flow to give substance to the new concept of the state and eventually to nationalism’ (1992, 73). This is tied to the French idea of républicanisme, which sees patriotism as a precondition for citizens to commit to defend the republic, and the requirement to defend the republic serves as a reminder of the value of their citizenship (Mouritsen Reference Mouritsen, Hakan and Lithman2005, 143–44).

After conscription was introduced during the French Revolution, it gradually spread to most of Europe. In 2000, 24 of 28 surveyed European countries had conscription, and conscripts typically made up most of the active-duty force (Jehn and Selden Reference Jehn and Selden2008, 94). Over the last 20 years, conscription has been abolished in most European countries (Bove, Leo and Giani Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024, 719) but is making a comeback due to the Russo-Ukrainian war. Germany, Latvia, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands have already reintroduced, expanded, or reactivated conscription or are considering doing so.

In this context, the question of the civic effects of peacetime conscription is important. We can learn some answers from the literature on the civic effects of wartime draft, and from the literature on the effects of voluntary military service. However, wartime draft is fundamentally different from peacetime conscription, as the latter does not imply that conscripts are exposed to war, and voluntary military service is different, because conscripts are coerced to serve, while volunteers are not. We begin by reviewing key studies of wartime draft and voluntary service and then proceed to discuss the potential civic effects of peacetime conscription.

The literature on wartime draft and exposure to combat shows mixed effects. Studies of the wartime draft in the U.S. show that service leads to decreased earnings (Angrist Reference Angrist1990) and has no effects on political attitudes (Green, Davenport, and Hanson Reference Green, Davenport and Hanson2019). It also increases turnout in elections (Cebula and Mixon Reference Cebula and Mixon2010), volunteering (Nesbit and Reingold Reference Nesbit and Reingold2011), and antiwar and liberal attitudes (Erikson and Stoker Reference Erikson and Stoker2011). Studies of combat experience in Israel show an association with less support for negotiation and compromise (Grossman, Manekin, and Miodownik Reference Grossman, Manekin and Miodownik2015), and deployment to Afghanistan by the Danish Army is linked to lower compassion but a higher commitment to public interest (Braender and Andersen Reference Braender and Andersen2013).

Overall, the studies show that wartime draft and combat experience affect civic outcomes, but not in a uniform way. Combat experience is, of course, very different from being conscripted in peacetime. This implies that the results cannot be readily transferred to the effects of conscription. However, the studies show that military service can have effects on a wide range of aspects of individuals’ views on politics and society, suggesting that peacetime conscription could potentially affect a broad range of outcomes.

Another related question is how voluntary military service in peacetime affects civic outcomes. Studies in this literature typically apply before-and-after comparisons of outcomes for soldiers or compare soldiers with other citizens. Military service seems to affect authoritarianism. In a classic study, Campbell and McCormack (Reference Campbell and McCormack1957) show that US pilot cadets scored lower on authoritarianism after one year of military training. Similarly, Roghmann and Sodeur (Reference Roghmann and Sodeur1972) find that military service in West Germany reduced authoritarianism. Another study of West Germany suggests that military service leads to higher democratic awareness (Lippert, Schneider, and Zoll Reference Lippert, Schneider and Zoll1978). Studies of France (Fize and Louis-Sidois Reference Fize and Louis-Sidois2020) and the U.S. (Teigen Reference Teigen2006; Leal and Teigen Reference Leal and Teigen2018) show that military service leads to higher turnout at elections, and Wilson and Ruger (Reference Wilson and Ruger2021) find an association between military service in the U.S. and political participation in organizations. Again, this literature shows that military experience can affect a wide range of civic outcomes.

We now turn to the studies of peacetime conscription. Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) make use of the fact that conscription was abolished in several European countries after the end of World War II, especially in the last 20 years. They argue that abolishing conscription is a national-level policy that is as good as random at the individual level. By comparing cohorts just before and just after conscription was abolished, they estimate the effect of conscription. Moreover, they argue that conscription can have equivocal effects on trust in institutions. On the one hand, conscription may transmit national values from the top to the conscripts, and the interaction among conscripts may create bonds across social and geographic groups, and both factors may increase institutional trust. On the other hand, military service may instill critical attitudes toward civil society and align conscripts with the military’s organizational interests, which may reduce institutional trust (Bove et al., Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024, 718). They show that abolishing conscription increases the overall institutional trust by 0.026 standard deviations among men but not among women, further strengthening the evidence of a causal effect of conscription.

This is an important finding. Given this result, reintroducing conscription could affect a key civic outcome. Furthermore, studies of the Argentinian conscription system show that conscripts are more likely to develop a military mindset (Navajas, Gabriela and López Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022), hold more sexist attitudes (Gibbons and Rossi Reference Gibbons and Martín2022), and become more involved in crime (Galiani, Rossi and Schargrodsky Reference Galiani, Rossi and Schargrodsky2011), but they also develop a stronger national identity and social integration (Ronconi and Ramos-Toro Reference Ronconi and Ramos-Toro2023) and are more supportive of the military (Choulis, Bakaki and Böhmelt Reference Choulis, Bakaki and Böhmelt2021). A study of the Danish conscription lottery finds that conscription reduces crime (Albaek, Leth-Petersen, le Maire et al. Reference Albaek, Leth-Petersen, le Maire and Tranaes2017). Conscription has also been linked to political outcomes. Horowitz and Levendusky (Reference Horowitz and Levendusky2011) show in a U.S. survey experiment that information about peacetime conscription decreases support for war, and Weiss (Reference Weiss2022) finds in a study of European countries that cohorts exposed to conscription display lower partisan affective polarization.

However, given the literature on wartime draft, combat experience, and military service, it is likely that conscription also affects other outcomes. Our aim is to study the effects of peacetime conscription on a broad range of civic outcomes.

We use the literature discussed above to identify the most relevant outcomes. Based on the classic French republican argument, we focus on three standard measures of collective values: national attachment, prosocial motivation, and collective orientation. We have strong evidence from Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) that conscription affects institutional trust. In addition to institutional trust, we include a measure for social trust.Footnote 1 Based on the literature on wartime draft and exposure to war, we include political attitudes, political interest, and authoritarian values.

In the next section, we introduce the Danish conscription lottery and how we use it to link data on conscription lottery outcomes with individual-level survey data on civic outcomes.

Empirical design

The Danish conscription lottery

Studying the causal effects of military conscription places heavy demands on the identification strategy. Estimates obtained by simply comparing individuals from countries that do and countries that do not use conscription for military service are very likely to be biased due to endogeneity. A vast number of unobservable factors related to national culture, history, political structure, and general policies will affect both a country’s conscription policy and our dependent variables. Furthermore, a country’s conscription policy is likely affected by our dependent variables. Nor is it a solution to compare individuals conscripted into military service with individuals who are not fit for service or refuse to comply with the conscription. Effect estimates from such comparisons are unreliable due to obvious selection biases.

We use the lottery design to address the endogeneity challenges to study effects of individual-level conscription. This design exploits the fact that in some instances, conscription into military service is decided by a random draw among the individuals who qualify for service. Typically, the lottery is used as a fair way to determine conscription when more citizens qualify for military service than are needed by the state. In effect, this creates a randomized experiment with comparable treatment and control groups. This design is used in studies on how conscription of US citizens to fight in the Vietnam War affected their lives, such as lifetime earnings (Angrist Reference Angrist1990) and political attitudes (Erikson and Stoker Reference Erikson and Stoker2011). Other studies have used the Argentinian conscription lottery, which ran until 1994, to examine the effects of conscription on crime (Galiani, Rossi, and Schargrodsky Reference Galiani, Rossi and Schargrodsky2011), sexist attitudes (Gibbons and Rossi Reference Gibbons and Martín2022), as well as personality and beliefs (Navajas, Gabriela, and López Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022).

Specifically, we reap the advantages of the Danish conscription lottery, which has been running since 1849, to estimate the effects of conscription on peacetime military service.Footnote 2 The lottery randomly places men who are deemed fit for military service in a group that is conscripted for military service (our treatment group) or a group that is not (our control group). The Danish constitution requires that all physically and mentally fit men must contribute to defending the country. Consequently, all male citizens must complete a medical evaluation and an IQ-assessment shortly after they turn 18. On average, 55.1 % of the men were deemed fit for service in the medical evaluations (1993–2005) covered by our data. Those who are fit for military service enter the conscription lottery and draw a random number. Men whose number is below a certain cut-off point will be conscripted for military service, and men drawing numbers above the cut-off are not conscripted. The lottery is divided into periods of six months (January–June and July–December), so all men called to medical evaluation during a period participate in the same lottery draw. The cut-off is set at the end of each period by the military authorities, depending on how many are needed for service in coming years. Women can volunteer for military service but are not conscripted and therefore not included in our analysis.

Men who are fit for service but not conscripted can volunteer for military service regardless of their lottery number. Another issue is that some of the conscripted did not complete the service because they chose conscientious objector service, were deemed unfit at a later point, became ill, were exempted for other reasons, or refused to do any kind of service (which entails imprisonment or forced community service). However, we circumvent such selection bias in the estimations by studying the effects of being conscripted through the lottery, which is the intention-to-treat effect of conscription. Accordingly, we use the conscription lottery to assign men to our treatment and control groups rather than whether they did service or not.

Table 1 shows the different types of military service the conscripts can end up doing. The table is divided into conscripts who comply with the requirement to serve and non-compliers. Allocation of conscripts to the different types of service is based on the allocation of conscripted men from the survey we use in our analysis (as detailed below, they participated in the conscription lottery in the first half of 2000). Most of the conscripts serve in the army.

Table 1. Type of service done by conscripts

Note: Numbers are based on conscripts from a survey of men who participated in the conscription lottery in the first half of 2000 (data used in analysis).

Service length differs for the specific subdivisions and functions within subdivisions. For example, in the navy, most are deployed to service at sea with a long service length. However, some perform a part of their service on land, which is sometimes of shorter duration. Length of service for conscientious objectors usually equals the nominated service length for compliers. Table 1 shows the average service length among the conscripted men from the survey we use in our analysis, categorized into the different types of services.

The training provides the conscripts enrolled in the army, navy, and air force with basic military skills, such as handling weapons, organization, and combat activities. Those enrolled in the civil defense and rescue services learn basic emergency and disaster rescue, and physical training. They perform services like assisting in cases of flooding, accidents, and fire. All enrolled conscripts live in barracks and discipline is a central element of the training (Bingley, Lyk-Jensen, and Rosdahl Reference Bingley, Lyk-Jensen and Rosdahl2022).

Study subjects

The set of subjects in our study consists of 1101 men deemed fit for service who participated in a survey designed to measure our dependent variables related to the republican argument (national identity, prosocial motivation, and collective versus individual orientation), trust (institutional and social), political interest, and political preferences (party choice and specific attitudes). To measure long-term effects, we focus on the conscription lottery in the year 2000 and measure civic outcomes 15 years later, in 2015. Using the lottery in 2000 is also beneficial for methodological reasons. From around 2005 onwards, fewer men are conscripted to military service based on the lottery. From this time, the state lowered the number of men it needed for service substantially in favor of volunteers. Furthermore, using the lottery in 2000 allows us to study conscription at a time when about half of the participants in the lottery are conscripted, while the other half is not. This provides the best conditions for generating equally sized treatment and control groups.

For these reasons, we sampled survey respondents among the men deemed fit for military service who participated in the January-June lottery in 2000. The survey was administered in spring 2015. We randomly sampled survey participants until at least 1100 had answered the survey in order to obtain a minimum detectable standardized effect size of 0.15. This provides our survey data with statistical power equivalent to Cáceres-Delpiano, Moragas, Facchini et al. (Reference Cáceres-Delpiano, Moragas, Facchini and González2021), whose study of long-term conscription effects in Spain includes 1093 individuals, and Navajas, Gabriela, and López (Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022), who use a survey of 1133 people to study long-term effects of conscription in Argentina. The power analysis is detailed in the online Appendix.

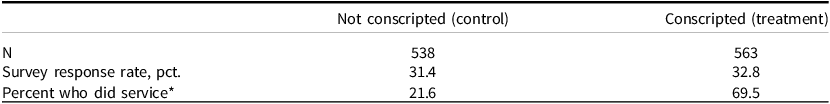

The survey was conducted through phone interviews since this was the best way to reach and obtain responses from the lottery participants. It was conducted as a general examination of societal conditions, and neither respondents nor interviewers were primed with information about conscription. All questions related to conscription, including the respondent’s own conscription status, were placed at the end of the survey. The response rate was 31.4 % in the control group and 32.8 % in the treatment group (the difference is not significant, p = 0.36). Table 2 shows an overview of the study subjects. In total, 21.6 % of the men who were not conscripted enrolled voluntarily. A total of 69.5 % of the conscripted men completed the service.

Table 2. Study subjects from survey by lottery conscription status

* Conscientious objector service not included in the pct. who did service. Total N = 1101.

Table A1 in the online Appendix shows that the group of conscripted men (treatment) and the group of men not conscripted (control) are highly balanced when we compare them on background variables (not affected by treatment) in the form of their medical assessment, IQ test, parents’ education, and parents’ country of origin. Table A2 in the online Appendix shows a comparison of the 1,101 men participating in the survey with the remaining 7,125 participants of the January–June 2000 lottery on the background variables (medical assessment, IQ test, parents’ education, and parents’ country of origin). The survey sample is generally a good representation of the participants of the January–June 2000 lottery. As we typically see, there is an overrepresentation of individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. We can observe a slightly higher number of individuals whose mother has a short-cycle higher education and a higher proportion with IQ scores on the higher end of the scale. While these differences are statistically significant, they are substantively quite small and are not considered to substantially bias the estimates (e.g., due to heterogeneous effects). There are no differences in the father’s educational level or the physical medical tests.

Measures

We measure national attachment on a scale of four items, which are similar to a subset of the items used by Huddy and Khatib (Reference Huddy and Khatib2007). The wording of the items was slightly modified to capture national attachment in the context of our study. We apply items that cover aspects of national identity and patriotism. The wording of all measurement items and factor analyses of the scales are displayed in the online Appendix. The items for national attachment can be found in Table A3. A factor analysis shows that the four items of national attachment load well on one dimension, and the scale has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.74.

The individual’s prosocial motivation has been measured extensively over the past thirty years. We apply a scale of four items (see online Appendix, Table A4) inspired by Perry’s (Reference Perry1996) work on measuring prosocial motivation as an individual’s commitment to the public interest and willingness to self-sacrifice to serve society. Thus, we follow in the footsteps of the vast body of research employing items identical to or inspired by Perry (Reference Perry1996) to measure prosocial motivation (Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Reference Ritz, Brewer and Neumann2016). These items have also been widely applied, in different translated versions, in the Danish context (Andersen, Heinesen, and Holm Pedersen Reference Andersen, Heinesen and Holm Pedersen2014). The four items we use cover aspects of the individual’s general sense of civic duty, commitment to serving society, and self-sacrifice for the common good. Our factor analysis supports the notion that the four items measure the same underlying dimension. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.80.

We measure the individual’s collective orientation (versus individual orientation) on a ‘society works best’ scale consisting of four items (see Table A5). Each item asks the respondents to choose between two opposite statements about whether society works best if people have a collective mindset or an individualistic mindset. The items thus capture the trade-off between perceiving people as a part of a collective or group and perceiving people as autonomous individuals. The factor loadings of the four items as well as Cronbach’s alpha for the scale (0.48) are on the low side, yet high enough that they make sense to calculate the scale. The factor analysis supports the claim of one dimension.

Institutional trust has been measured in various ways. Here we follow the widely applied approach that asks respondents to indicate their trust in different state institutions and combine the answers to form an index of institutional trust (see, e.g., Bove et al. Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024). We measure trust in three core institutions: the parliament, the police, and the military. Trust in the parliament and the police are included in numerous studies on institutional trust (Sønderskov and Dinesen Reference Sønderskov and Thisted Dinesen2016), and we include the military due to our study’s focus on conscription for military service. Respondents indicate their trust in the parliament/the police/the military on an 11-point scale ranging from ‘0: No trust at all’ to ‘10: Trust completely’. A factor analysis (Table A6, online Appendix) and Cronbach’s alpha (0.71) support the approach of measuring institutional trust on a one-dimensional scale. In the analysis, we also examine trust in the parliament, the police, and the military separately to check if there are different effects for each of the institutions.

Social trust is measured by a three-item scale that has been extensively applied and validated in various contexts, including Reeskens and Hooghe (Reference Reeskens and Hooghe2008) and Dinesen and Sønderskov (Reference Dinesen and Mannemar Sønderskov2015). The item wording as well as the scale’s factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha (0.73) are presented in Table A7 of the online Appendix.

To measure political interest, we ask the respondents to state whether they are ‘very interested in politics, somewhat interested, only a little, or not at all interested in politics’. This item has been used as a solid measure of political interest for the past fifty years in the recurring Danish election surveys (Stubager, Hansen, Lewis-Beck et al. Reference Stubager, Hansen, Lewis-Beck and Richard2021). The respondents’ party choice is measured by asking which party they would vote for if there were a parliamentary election tomorrow. We also include three items to measure authoritarian attitudes related to child-rearing, immigration, and criminal punishment (item wording displayed in the online Appendix, Table A8). The item on child-rearing is from Feldman (Reference Feldman2003), and the items on immigration and criminal punishment are well tested by the Danish election surveys (Stubager, Hansen, Lewis-Beck et al. Reference Stubager, Hansen, Lewis-Beck and Richard2021).

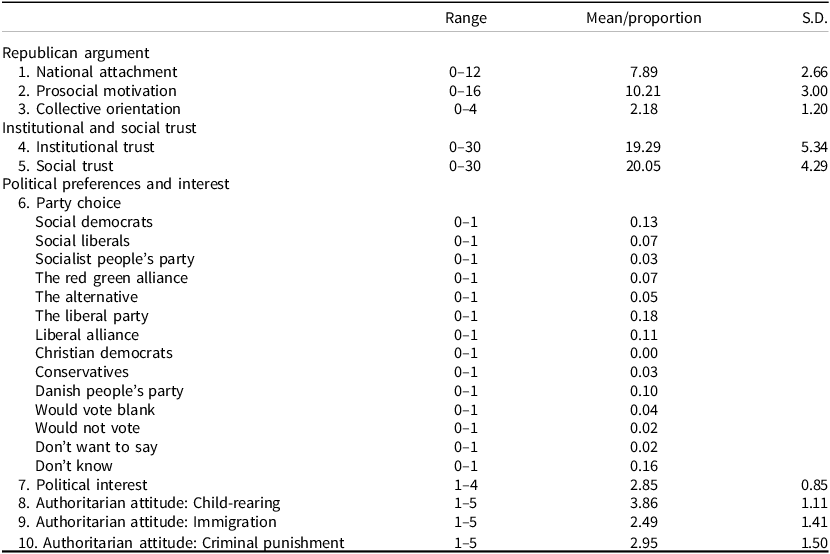

Table 3 provides an overview of all 10 outcome variables. Except for party choice, all outcome variables have continuous scales with the ranges shown in Table 3. Table 3 shows the mean (unstandardized) and standard deviation (S.D.) for each of the nine continuous outcome variables. For the categorical outcome variable (party choice), Table 3 shows the proportion of subjects in each category. We have standardized the continuous outcome variables in the analysis to simplify interpretation of the effect sizes. This means that the effect should be interpreted in terms of standard deviations of the distribution of the given dependent variable. For example, an effect size of 1 of conscription on political interest would imply that conscription increases political interest by an amount equivalent to 1 standard deviation on the political interest scale.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of outcome variables: Scale range, (unstandardized) means/proportions, and standard deviations (S.D.)

Note: Mean is shown for continuous outcome variables and proportions for categorical outcome variables. S.D = standard deviation.

Model specifications

To estimate the effects of conscription on the outcome variables (see Table 3), we use a simple regression model:

where

![]() ${y_i}$

is the value on the given dependent variable for individual i. CONSCRIPTION

i

is our treatment variable and takes the value 1 if individual i was conscripted and 0 if not.

${y_i}$

is the value on the given dependent variable for individual i. CONSCRIPTION

i

is our treatment variable and takes the value 1 if individual i was conscripted and 0 if not.

![]() $\beta $

provides the estimate of the conscription effect. In robustness analyses, we also estimate a model including covariates:

$\beta $

provides the estimate of the conscription effect. In robustness analyses, we also estimate a model including covariates:

where COVARIATES i is a vector of covariates representing the experimental subjects’ medical assessments (including IQ assessment), mother’s education, father’s education, mother’s ethnic origin, and father’s ethnic origin. We estimate all models using linear regression.

We present the results from the above-mentioned model [1] in figures, but all results are shown in table form in Tables A9–A12 in the online Appendix. These tables also display the robustness analyses where covariates are included. Inclusion of covariates does not change the conclusions. For comparison, we show the association between parents’ education level and the given dependent variable underneath each conscription effect in the result figures. We choose parents’ education level as a comparable predictor as this is usually found to be substantially associated with several of our outcome variables such as political interest, institutional and social trust, and authoritarian attitudes. For simplicity in the visual presentation of the results, we use a variable that combines mother’s and father’s education (and not separate variables for mother’s and father’s education as in A2, A9–A12). The variable takes the value of 1 if both parents have higher education and 0 if not. The result figures also include a gray area indicating effect sizes below the calculated minimum detectable effect size (cf., the power calculation).

In cases where the intention-to-treat analysis of the conscription (see equation [1] above) shows significant effects, we add an analysis that focuses on the specific effect of serving, that is, complying with the conscription call and completing the service. We do this by analyzing the local average treatment effect (LATE) using the two-stage least squares approach (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009, 113–217). The online Appendix includes the LATE results in Table A14, and a discussion of the assumptions of the LATE interpretation.

Results

Figure 1 shows the effect of conscription on the individual’s national attachment, prosocial motivation, collective orientation, and the two measures of trust. The x-axis in Figure 1 shows the size of the conscription effect measured in standard deviations on the outcome variables. The gray area in Figure 1 indicates effect sizes below the calculated minimum detectable effect size (cf., the power calculation).

Figure 1. Effects of conscription on national attachment, prosocial motivation, collective orientation, and trust.

Note: 95 % confidence intervals. Standardized outcome variables. The gray area indicates effect sizes below the calculated minimum detectable effect size (cf., the power calculation).

For all outcome variables in Figure 1, the standardized effect size of conscription is below 0.1 and statistically insignificant at the 0.05-level. For national attachment, prosocial motivation, and collective orientation, the parameter estimates are negative but statistically insignificant. In contrast, the association between parents’ education and national attachment is statistically significant. The standardized size of the association is −0.22, which means that men whose parents both have higher education degrees, on average, score 0.22 standard deviations lower on national attachment than men who do not have two parents with higher education degrees. The estimate for social trust is very close to zero. For comparison, parent education has a positive, statistically significant, and quite large effect on social trust. We infer from this that conscription has no, or very limited, effects on these outcomes. Figure 1 also shows our estimate for institutional trust. We know from Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) that conscription is associated with lower institutional trust. Our results are consistent with this, as we observe a negative parameter estimate. Our estimate is not statistically significant.Footnote 3 This is not surprising, given that our study is not designed to capture effect sizes below −0.15 standard deviation. Based on this, we cannot, of course, conclude that conscription does not affect institutional trust. However, we find no evidence of a strong effect of conscription on institutional trust. This is also the case when we examine trust in each of the institutions separately (the parliament, the military, and the police; see Table A10 in the online Appendix).

As the factor loadings and Cronbach’s Alpha of the collective versus individual orientation scale are on the low side (see the Measures section above), we conduct an additional analysis using the individual items for collective orientation as outcome variables. This is reported in Table A13 in the online Appendix. For three of the four collective orientation items (nos. 1, 2, and 4), we see no effect of conscription, as is the case when using the scale as outcome variable (see Figure 1). For collective orientation item 3, we observe a −0.08 effect (p < 0.01) of conscription. This means that the share agreeing that ‘society works best when there are significant rules in place to prevent disorder in the community’ (in contrast to ‘society works best when there isn’t excessive regulation and control over individuals within the society’) decreases from 69 pct. in the non-conscription group to 61 pct. in the conscription group. We return to this in the discussion.

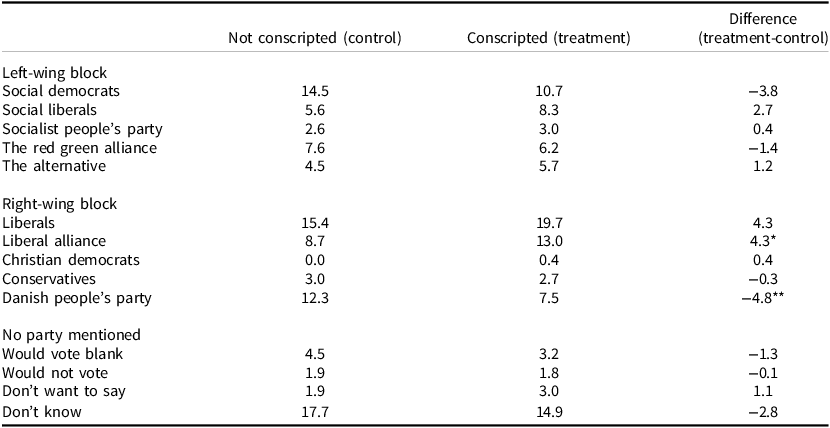

In the second part of our analysis, we turn our attention to the effects on political preferences and interests. The effect of conscription on party choice is shown in Table 4, which displays the percentages in the conscripted and non-conscripted groups, respectively, who would vote for each of the ten parties running for parliament in the 2015 election. The parties are usually divided into a left-wing block that supports a government led by the Social Democrats and a right-wing block that supports a government led by the Liberal Party. This was also the case in the 2015 election, and we list the parties in Table 4 according to this block division.

Table 4. Party choice for non-conscripted and conscripted experimental subjects (%)

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N = 1101.

First, we cannot conclude that conscription moves votes from one block to the other. The gains and losses from conscription for the parties in the left-wing block more or less cancel each other out. This is confirmed by an analysis using the blocks as dependent variable (not shown in Table 4). Here, the difference between the left-leaning block in the non-conscripted group and the conscripted group is 0.8 percentage points and not statistically significant (p = 0.77). We estimate that the right-wing block is 3.8 percentage points larger in the conscripted group compared to the non-conscripted group. This would suggest that conscription moves votes from the ‘no party mentioned’ categories to the right-wing block. However, the difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.21).

Second, when we examine the parties within each block, we observe differences between the conscripted and non-conscripted groups. Most notably, conscription has a statistically significant, positive effect on the percentage voting for the Liberal Alliance and a negative effect for the Danish People’s Party. We should note that the differences are not significant at the 0.05-level if we use a Bonferroni correction to consider that we test a hypothesis for each party. The Liberal Alliance focuses on individual freedom in terms of shrinking the state, lower taxes, and individual choice. The party is one of the clearest advocates of making military service a free choice for each person. In contrast, the Danish People’s Party seeks to promote traditional values, a national focus, and anti-immigration policies. The party is a very strong and outspoken supporter of forced conscription.

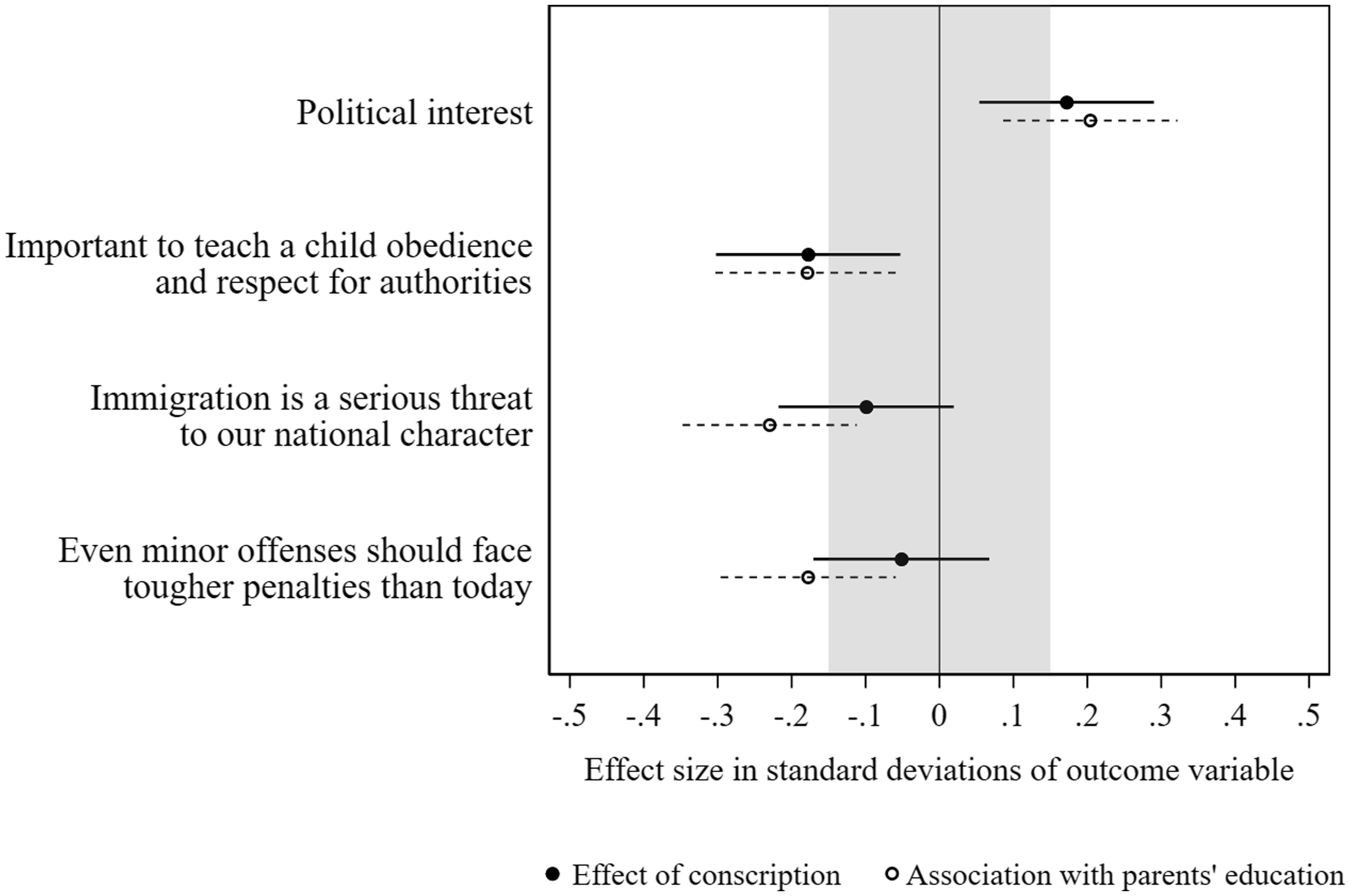

Figure 2 shows the effects of conscription on political interest and authoritarian attitudes related to child-rearing, immigration, and criminal punishment. Focusing first on political interest, the top part of Figure 2 shows that conscription has a substantial and statistically significant effect (p = 0.004) on political interest. The effect has a p-value of 0.04 if we apply a Bonferroni correction for testing 10 outcome variables. The effect size is 0.17 on the standardized variable measuring political interest. Thus, drawing a low lottery number that entails conscription leads, on average, to a 0.17 standard deviation increase in political interest compared to those drawing a non-conscription number. This suggests that conscription has a substantial positive effect on the individual’s political interest. That this is not a small or trivial effect size is evident from the fact that it is nearly as large as the association between parental education and political interest, which is 0.20. We estimate the LATE effect to be 0.38 (see Table A14 in the online Appendix). Thus, given that the assumptions for the LATE interpretation hold (see discussion in the online Appendix), we estimate that completing the service increases political interest by 0.38 standard deviations. We return to the effect on political interest in the discussion.

Figure 2. Effects of conscription on authoritarian attitudes related to child rearing, immigration, and criminal punishment.

Note: 95 % confidence intervals. Standardized outcome variables. The gray area indicates effect sizes below the calculated minimum detectable effect size (cf., the power calculation).

Turning to the analyses of authoritarian attitudes, note that a high value on the outcome variables indicates a more authoritarian attitude (i.e., children should be obedient, opposition to immigration, and harsher penalties for crime). The estimates show that, if anything, conscription tends to lower individuals’ authoritarian attitudes on the three specific issues. This differs from Navajas, Gabriela, and López (Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022) results in a study of conscription in Argentina. As we return to the discussion, this may reflect differences between conscription and military service in Denmark and Argentina. Our most notable result is that conscription has a negative effect on the degree to which one considers it important to teach children obedience and respect for authorities. The effect size is −0.18, which means that being assigned to the conscription group leads to a 0.18 standard deviation decrease in authoritarian values on child rearing. The effect is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.005 (the estimated effect has a p-value of 0.053 if we correct for multiple hypothesis testing). The effect is comparable in magnitude to the association between parents’ level of education and authoritarian values on child rearing. Our LATE calculation in the online Appendix’s Table A14 shows that serving leads to a 0.40 standard deviation decrease in authoritarian values on child rearing. The estimates for an effect on perceiving immigration as a serious threat and tougher criminal punishment are also negative but statistically insignificant at the 0.05-level (the p-values are 0.10 and 0.40, respectively).

Discussion

Following the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, military spending was reduced in many Western countries, and conscription was abolished or scaled back in most of Europe. Territorial defense was seen as less relevant, and armies were reduced and reformed to be able to handle conflicts on a smaller scale and abroad. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, this is now changing. Spending on defense is increasing, and conscription is being reintroduced or considered all over Europe.

Conscription can be traced back to the end of the 18th century in France where it was introduced for the obvious military reasons and to foster loyalty to the state. The logic that conscription in peacetime can affect the minds of citizens by increasing loyalty or a sense of belonging to society is also reflected in modern thoughts on conscription and universal service.

Empirical studies of wartime drafts have shown that military service affects civic outcomes such as political attitudes and political participation. However, these results do not tell us much about the effects of peacetime conscription. Being drafted in times of war and potentially being exposed to combat is very different from receiving military training and serving for six months to a year.

Although peacetime conscription is less dramatic than being drafted during war, conscription is still one of the most intrusive burdens democratic states place on an individual citizen. Although many see conscription as a meaningful way to contribute to society, it forces selected, typically based on a lottery, young men to spend an extended period in barracks with peers recruited from different parts of society while being exposed to military training and values. This intensive treatment may well affect recruits.

Using the Danish conscription lottery, we estimate the causal effects on the individual level of being conscripted on three sets of civic outcomes. Based on the classic French idea of républicanisme, we study national attachment, prosocial motivation, and collective orientation. Based on the arguments of Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024), we also include measures of institutional and social trust. Based on the literature on wartime drafts, we study political outcomes such as party choice, political interest, and authoritarian attitudes on specific issues such as child-rearing, immigration, and criminal punishment.

Like Navajas, Gabriela, and López (Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022) study of the Argentinian conscription lottery, we are interested in the long-term effects of conscription in order to understand whether reintroducing it will cause a permanent change in societies. To understand the lasting effects of conscription, the data for all civic outcomes were measured 15 years after conscription. We find limited effects on almost every outcome. Regarding institutional trust, we find a negative but statistically insignificant effect of conscription. Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) find that institutional trust increases for cohorts after the conscription was abolished in European countries. We see these results as consistent, as our study has less power than Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024). Bove et al. (Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024) find an effect of 0.026 standard deviations. Our study was designed to detect effect sizes of at least 0.15.

We do see a tendency towards higher political interest among conscripted men. This result is a bit surprising, given that we generally see limited effects on civic outcomes. The question is why conscription affects political interest. We cannot give a definitive answer, but we note that the mechanism is not that conscription in Denmark affects prosocial motivation, authoritarianism, or political attitudes to left- or right-wing blocs. We offer two possible explanations. First, being conscripted may spark interest in the political system that requires you to serve. This is consistent with the observation that conscripted men are more likely to vote for the Liberal Alliance, which is critical of the conscription lottery and less for the Danish People’s Party, which is a vocal supporter of conscription. Second, the result may have a parallel in Leal and Teigen’s (Reference Leal and Teigen2018) finding that military service is associated with more political participation. They argue that this could reflect an education effect, as the tendency is stronger for veterans with relatively low levels of education. This may also be the case here, as military service in Denmark has educational components that could affect political interest.

In contrast to Navajas, Gabriela, and López (Reference Navajas, Gabriela, López, Martín and Antonia2022) study of conscription in Argentina, we do not find that conscription generates authoritarian attitudes. If anything, we, in the Danish case, find that conscription reduces authoritarian values. A similar effect has been found for military service (Roghmann and Sodeur Reference Roghmann and Sodeur1972). In our case, we see a negative effect on authoritarian attitudes related to child-rearing. We also find a negative effect on one of the collective orientation items (‘society works best when there are significant rules in place to prevent disorder in the community’). Since the item emphasizes rules to prevent disorder, it bears some resemblance to aspects of authoritarian values. This is likely to reflect that conscription systems are different in Denmark and Argentina.

We also see some small fluctuations between parties that favor and oppose conscription. However, on all other measures, effects are statistically insignificant and close to zero. It is entirely possible that conscription impacts civic outcomes during service and for a period afterward, but in the long run, these effects nearly disappear.

It is also possible that more intrusive, comprehensive, or prolonged military service would have stronger effects. However, Danish military service is comparable to that of other NATO countries; the duration in Denmark, averaging nine months, is similar to abolished conscription systems in Europe and aligns with what is currently being considered in countries exploring reintroducing conscription. As such, the results are relevant to most other European countries. They are, of course, less relevant to countries with longer periods of service (Israel, for example, with military service for three years, or South Korea with at least 1½ years), or countries with conscripts in war. Future research could focus on civic outcomes in such systems. Another important avenue for future research is the effects of conscription on citizens in general. We have focused on individual-level effects for conscripts, but it is also possible that conscription can affect cohorts affected by conscription (as shown by Bove et al. Reference Bove, Leo and Giani2024), and also citizens that are not directly affected.

It is important to remember that we study the effects of being conscripted. Conscription is a strong predictor of doing the service, but it is not a one-to-one determinant of military service since some do not comply with the conscription call-up and some who are not conscripted volunteer to do the service. Therefore, it is relevant to discuss which subjects are appropriate to assign to the treatment and control groups, respectively. In accordance with the intention-to-treat principle, we use the random assignment from the conscription lottery to allocate men to either the treatment or the control group. A simple comparison between men who have served and those who have not would severely bias the results due to selection effects. However, to examine the effects of having completed the service, we estimate LATE effects using the lottery as an instrument for doing the service (see the online Appendix, Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009). LATE estimation is based on a number of assumptions, most of which are considered to hold in our case. However, the assumption that the effect of conscription as determined by lottery draw works exclusively through doing service (exclusion restriction) is open to debate.

Finally, we focused on the conscription lottery in the year 2000, partly in order to study long-term civic effects, and partly because this lottery offered a strong design with about half of the participants in the lottery conscripted. As we have argued in this paper, conditions have changed, and the relevance of conscription has increased. It is a question for future research whether this change in how conscription is seen has implications for its civic effects. Another consequence of the long-term perspective is that our respondents may have experienced combat missions during their military career. Danish military has participated in many international missions in the period between the lottery and the survey. So, although the lottery is peacetime conscription, which has never assigned conscripts to such missions, it is possible that respondents have been affected by later events in their military career.

We conclude that the classic idea that conscription nurtures civic outcomes has little relevance for conscription. However, we can also conclude that conscription has no clear negative effects, and that decision-makers should not expect that reintroducing conscription will have substantial, long-lasting civic costs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100510

Data availability statement

A part of our data consists of register data on individuals in Denmark, which is made available for research by Statistics Denmark. This allows us to include unique, detailed data on socioeconomic background and conscription status at the individual level. We are not allowed to extract data on individuals from Statistics Denmark (the data is analyzed on their servers through a research access point). This means that we cannot make data available in a public data repository. A more detailed description of the access and rules of register data in Denmark can be seen at: https://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice/Dataadgang. If you wish to contact Statistics Denmark about our data, our project number is 704511.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Major Enrico Schou, former head of the Conscription Section, and the Danish Ministry of Defence Personnel Agency for access to and assistance with the conscription lottery data in 2014 and information about how the Danish conscription system works. We would also like to thank Lotte B. Andersen, Morten Brænder, Per Mouritsen, Kim M. Sønderskov, Emily C. Bech, and the anonymous reviewers for their very valuable comments and suggestions regarding our study and previous versions of the manuscript.

Funding statement

The project is funded by a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

The study involves research on human subjects as we use registry and survey data on men who participated in the Danish conscription lottery. The study has been reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency/Aarhus University (case number: 2527) and Aarhus University’s Research Ethics Committee (BSS-2024-197-A). Use of registry data on human subjects where consent cannot be obtained is based on § 10 of the Data Protection Act, pursuant to Article 6(1)(e) and/or Article 9(2)(j).