Introduction

Across Western countries, civil society organizations are increasingly recognized as central to supporting social inclusion, particularly for marginalized groups (Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021; Reference Holstein, Qvist and HenriksenHolstein et al., 2023). Policy initiatives addressing social exclusion often frame volunteering as a tool for personal development and workforce training. Within this framework, volunteering is closely aligned with reemployment strategies, emphasizing its role as an instrument for labor market reintegration (Reference Kamerāde and PaineKamerāde & Paine, 2014). In Denmark, this expectation has shaped welfare policies for decades, with policymakers relying on voluntary organizations to facilitate pathways into employment for individuals at society's margins (Reference Holstein, Qvist and HenriksenHolstein et al., 2023; Reference Henriksen, Qvist and HolsteinHenriksen et al., 2023, Frederiksen et al., Reference Frederiksen, Henriksen and Grubb2021). The logic is that voluntary organizations offer lower entry barriers than private companies yet still organize productive activities that generate real social value—unlike some subsidized public sector job training initiatives (Reference Hansen and NielsenHansen & Nielsen, 2021).

Consequently, volunteering is increasingly institutionalized as a mechanism to equip marginalized groups with skills, networks, and experiences that could enhance their employability. However, while existing research have extensively examined the individual antecedents and consequences of volunteering, large-scale studies of labor market inclusion through volunteering often yield inconclusive or contradictory results (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2008; Reference Spera, Ghertner, Nerino and DiTommasoSpera et al., 2015; Reference Paine, McKay and MoroPaine et al., 2013; Reference Mao and NormandMao & Normand, 2022; Reference Handy and GreenspanHandy & Greenspan, 2009; Reference Cattacin and DomenigCattacin & Domenig, 2014; Reference Qvist and MunkQvist & Munk, 2018; Reference Peterie, Ramia, Marston and PatulnyPeterie et al., 2019; Reference Holstein and QvistHolstein & Qvist, 2025). One reason may be the focus on quantifiable outcomes—such as employment rates or earnings—which tend to overlook less tangible yet equally significant forms of value, including self-efficacy, self-worth, and social belonging. These dimensions are particularly relevant for individuals whose biographies and resources do not align with dominant labor market norms. Moreover, this focus often sidelines attention to the everyday organizational processes through which inclusion is actually experienced—especially by those facing long-term unemployment and intersecting forms of vulnerability (Reference Shachar, von Essen and HustinxShachar et al., 2019; Reference WilsonWilson, 2012). A smaller body of qualitative research has explored how volunteering supports labor market inclusion by providing informal learning opportunities (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2008; Reference Nichols and RalstonNichols & Ralston, 2011), fostering social capital (Reference Cattacin and DomenigCattacin & Domenig, 2014; Reference Handy and GreenspanHandy & Greenspan, 2009), and offering structure and meaning to those navigating exclusion (Reference Baines and HardillBaines & Hardill, 2008; Reference Farrell and BryantFarrell & Bryant, 2009; Reference CohenCohen, 2009). While these studies contribute valuable insight into the micro-processes of labor market inclusion through volunteering, they often remain tied to a logic of capital conversion. That is, they adopt a transactional model in which volunteering is valuable primarily because it enables individuals to accumulate resources—skills, networks, habits—that can later be exchanged for labor market advantage. This perspective struggles to explain cases where volunteering fosters social inclusion without accumulation of convertible resources or resulting in measurable employment gains. Consequently, while the role of voluntary organizations in promoting labor market inclusion is widely acknowledged, the specific processes through which volunteering supports this process for marginalized individuals remain underexplored.

This study addresses this gap by introducing the concept of valorization, a framework for understanding how voluntary social welfare (VSW) organizations specifically serving vulnerable, marginalized individuals affirm participants’ worth beyond their employability. Valorization thus provides an alternative to dominant models that frame social inclusion primarily as a form of “capital conversion” through volunteering. The study identifies three interrelated processes through which valorization unfolds: 1) the discovery of previously unrecognized skills, 2) the reinforcement of self-efficacy through organizational validation, and 3) the internalization of new narratives of worth. These phases emerge from the dialectical interplay between volunteers and organizational settings. That is, valorization is not automatic but co-constructed through interaction within these contexts. While this study broadly investigates social inclusion, it focuses on labor market inclusion as a dominant and policy-relevant form—reflecting how employability often functions as a proxy for inclusion in both policy and research (Reference LevitasLevitas, 2006; Reference Nichols and RalstonNichols & Ralston, 2011).

Theoretically inspired by Martha Nussbaum's conceptualization of combined capabilities (2011), the study offers an alternative to dominant approaches that interpret volunteering primarily through the lens of employability and frame capital conversion as the central mechanism linking it to labor market inclusion. Instead, it foregrounds how informal skills and competencies—such as empathy, patience or preparing homecooked meals—can be surfaced, affirmed, and given social value within VSW organizations, even when they do not translate directly into labor market outcomes. The study analyzes biographically inspired interviews with 13 volunteers, who are long-term unemployed while also facing other intersecting forms of vulnerability, and three organizational leaders to explore how valorization unfolds within the everyday practices of VSW organizations. The guiding research question is: How do voluntary social welfare organizations foster social inclusion by valorizing the informal resources of marginalized volunteers, and how is this experienced by the volunteers?

In what follows, I first unpack state-of-the-art research on the link between volunteering and paid work among vulnerable, marginalized individuals, presenting an analytical approach sensitive to the interplay between the lived experiences of the volunteers and the enabling settings of the VSW organizations. Second, the empirical cases and applied methods are presented. Third, I analyze the valorization process as it unfolds in practice. Finally, I discuss how the findings broaden our understanding of social inclusion in voluntary settings—beyond the narrow lens of employability.

Social Inclusion Through Volunteering

This study examines how marginalized individuals experience social inclusion through volunteering in voluntary social welfare (VSW) organizations. Existing scholarships tend to frame this topic within two dominant and often competing discourses. The first, which I refer to as the instrumentalist discourse, conceptualizes volunteering primarily as a means to an end—namely, as a steppingstone to employment and labor market integration. The second, which I term the intrinsic discourse, emphasizes the social, emotional, and relational value of volunteering, highlighting how it fosters a sense of belonging, safety, and personal growth. Below, I review the contributions and limitations of each, identify key gaps, and introduce an analytical framework attuned to the dialectical processes of valorization through which experiences of inclusion are co-constructed within VSW organizations.

The Instrumental Discourse: Volunteering as a Pathway to Employment

Within the instrumentalist discourse, volunteering is framed as a tool to enhance employability, particularly through two mechanisms: human capital and social capital acquisition. First, the human capital approach suggests that volunteering helps individuals develop transferable skills and work-related experiences that improve their labor market prospects (Reference BourdieuBourdieu, 2011; Reference ColemanColeman, 1988; Reference PutnamPutnam, 2000; Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2008; Reference Day and DevlinDay & Devlin, 1998; Reference Qvist and MunkQvist & Munk, 2018; Reference Petrovski, Dencker-Larsen and HolmPetrovski et al., 2017; Reference Holstein and QvistHolstein & Qvist, 2025). Second, the social capital approach emphasizes how volunteering facilitates access to networks and opportunities through new or “weak” ties (Reference GranovetterGranovetter, 1973; Reference Handy and GreenspanHandy & Greenspan, 2009; Reference LinLin, 1999). Empirical studies show that voluntary organizations often foster such interactions, potentially increasing access to job-related information and support (Reference McPherson and Smith-LovinMcPherson & Smith-Lovin, 1982; Reference Ruiter and De GraafRuiter & De Graaf, 2009; Reference Cattacin and DomenigCattacin & Domenig, 2014; Reference Peterie, Ramia, Marston and PatulnyPeterie et al., 2019; Reference DederichsDederichs, 2024). While this literature underscores the instrumental value of volunteering, they also raise critical questions about whether its primary function is to facilitate labor market integration—or whether this framing overlooks the broader social and personal significance of volunteering for marginalized individuals, especially those whose life circumstances limit their access to capital accumulation or conversion.

The Intrinsic Discourse: Volunteering as an end in itself

In contrast, the intrinsic discourse emphasizes the intrinsic value of volunteering. From this perspective, volunteering constitutes an important form of civic participation, offering marginalized individuals emotional and social support independent of employment outcomes (Reference Baines and HardillBaines & Hardill, 2008; Reference CohenCohen, 2009; Reference Hall and WiltonHall & Wilton, 2011). Two primary arguments characterize this discourse. First, volunteering serves as a protective environment where individuals gain stability and purpose despite structural barriers, such as prolonged unemployment or health-related constraints (Reference Baines and HardillBaines & Hardill, 2008; Reference Hall and WiltonHall & Wilton, 2011). Second, participation in voluntary organizations fosters social integration, empowerment, and an enhanced sense of belonging through interpersonal recognition and strengthened community ties (Reference CohenCohen, 2009; Reference Nichols and RalstonNichols & Ralston, 2011).

Although these studies highlight the intrinsic meaningfulness of volunteering, few studies systematically examine how everyday organizational practices cultivate and sustain these benefits. Relatedly, the volunteer-management literature—while advancing evidence-based practices such as role clarity, onboarding, supportive supervision, recognition, peer integration, and flexible task design—largely centers generic volunteer populations and managerial endpoints (retention, satisfaction, role identity) (Einolf, Reference Einolf2018; Reference Piatak and SowaPiatak & Sowa, 2024; Reference Studer and Von SchnurbeinStuder & von Schnurbein, 2013). Consequently, empirically grounded guidance is limited on how to adapt these practices for structurally vulnerable volunteers—such as the long-term unemployed—beyond extrapolations from a generic volunteer profile (see Krasniqi, Reference Krasniqi2024). Thus, the intrinsic discourse identifies positive outcomes without fully unpacking the relational processes through which inclusion emerges.

Asset-Based and Strength-Based Perspectives

A related perspective emerges from asset-based approaches in volunteer research and strengths-based approaches in social work, both of which emphasize recognizing and mobilizing marginalized individuals’ existing competencies rather than focusing on their deficits (Reference Benenson and StaggBenenson and Stagg, 2016; Reference SaleebeySaleebey, 2012; Reference GutierrezGutiérrez, 1995; Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Jefferies, Qtaishat, Dajani and KumarPanter-Brick et al., 2024). However, despite offering an important corrective, asset-based approaches remain closely tied to a logic of capital accumulation and employability. The approach tends to frame volunteering primarily as a means of activating resources—such as skills, motivation, or networks—that can be converted into labor market outcomes (Reference Benenson and StaggBenenson & Stagg, 2016). Consequently, this perspective struggles to explain cases where volunteering fosters social inclusion without accumulation of convertible resources or resulting in measurable employment gains.

While strengths-based empowerment in social work affirms individuals’ existing resources, it typically unfolds in structured, professionally guided interventions. In contrast, the VSW organizations in this study foster empowerment informally—through everyday interactions, peer support, and shared narratives of worth. Here, empowerment emerges organically, suggesting that inclusion in voluntary contexts differs from goal-oriented social work practices.

Addressing the Gaps: A Relational Framework of Valorization

Based on this review, three research gaps emerge. First, the instrumental discourse's focus on measurable economic outcomes—such as skills and employability—often overlooks the non-material value of volunteering, especially for those unable to convert acquired resources into formal employment. Second, while the intrinsic discourse highlights benefits like stability, empowerment, and belonging, it seldom unpacks the relational and organizational processes that cultivate these outcomes. Third, although asset-based approaches offer a strengths-based perspective, they remain tied to a logic of capital accumulation, providing limited explanations for inclusion without measurable employment outcomes.

This study addresses these gaps by introducing the concept of valorization—the recognition and affirmation of informal, biographically rooted competencies within enabling organizational environments. It explores inclusion not as a fixed outcome, but as a dynamic, relational transformation.

The framework draws on Martha Nussbaum's concept of combined capabilities from the capability approach (Reference NussbaumNussbaum, 2011; Reference SenSen, 1980). This perspective shifts the analytical focus from what individuals have—such as formal qualifications or networks—to what they are effectively able to do and be within supportive environments. A key concept is “combined capabilities,” which emerge when internal traits (e.g., empathy, patience, care) interact with enabling institutional structures. From this view, the value of volunteering does not hinge on whether it leads to employment, but on whether it expands real opportunities for agency, self-respect, and meaningful participation in social life. Thus, VSW organizations may foster inclusion by creating spaces that allow these capabilities to emerge and flourish. Within the specific settings of the VSW organizations value is given to what is often dismissed as irrelevant, reframing “deficits” as meaningful forms of social contribution. In doing so, they enable the process of valorization through the recognition and affirmation of informal competencies that are typically invisible or devalued in formal institutional contexts.

This framework offers a conceptual lens for understanding how social inclusion emerges not through capital accumulation but through the valorization of informal, existing competencies. This theoretical grounding enables the study to trace how such overlooked skills are discovered, affirmed, and internalized through interactions within supportive organizational environments. I define this process as valorization: the ongoing recognition and validation of competencies that are often invisible or undervalued in conventional institutional settings. The process involves three interrelated phases: (1) discovery of previously unrecognized skills, (2) organizational validation of these competencies, and (3) internalization of new narratives of self-worth. Through tracing these everyday interactions, this study moves beyond instrumentalist models focused on capital accumulation and employability, offering instead a detailed understanding of how inclusion unfold through the process of valorization—the dialectic interplay between individual agency and organizational context. By highlighting these dynamics, the study contributes significantly to volunteer research, demonstrating precisely how inclusion is cultivated in voluntary organizational settings. A central finding is that valorization does not emerge from volunteering per se, but from the specific institutional and relational conditions that VSW organizations provide. It is through the interactions between volunteers and organizational actors—such as staff and leaders—that previously unrecognized competencies are discovered, validated, and internalized. These interactions are not incidental but are enabled by the organizational culture and structure, which afford space for trust, informality, and relational engagement. Central to this process is the development of self-efficacy—defined as the belief in one's own ability to act meaningfully in the world (Bandura, Reference Bandura2000).

Methods and Empirical Material

This study draws on qualitative life course interviews with 13 socially marginalized individuals volunteering in three Danish voluntary social welfare (VSW) organizations. The aim was to explore how these individuals experience volunteering while navigating multiple and intersecting forms of vulnerability. To contextualize these experiences, semi-structured interviews were also conducted with three organizational leaders to illuminate the organizational settings in which volunteering took place.

Voluntary Social Work Organizations in Denmark

The study focuses on three voluntary social welfare (VSW) organizations operating in Denmark. These organizations work within hybrid welfare spaces where the roles of volunteers and service users often overlap. Although their ethos loosely aligns with Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD)—which promotes community-led change through structured facilitation and asset mapping (Haines, Reference Haines2014; Reference Midtgård and AgdalMidtgård & Agdal, 2022)—the organizations in this study differ in important ways. They are not community-initiated nor professionally driven but foster empowerment through informal participation, relational trust, and the recognition of individuals’ biographical strengths (Reference HainesHaines, 2014).

All three organizations serve socially marginalized individuals and include a mix of traditional volunteers and user-volunteers (those who both receive services and contribute). One organization collaborates with a municipal job center to offer volunteering and skills development in a social café setting, while the other two function as volunteer-driven social enterprises primarily aimed at engaging non-Western immigrant women.

Sampling Strategy

The central sampling criterion was that organizations actively used volunteering as a method for engaging individuals at the margins of the labor market. Crucially, participation in all selected organizations was voluntary rather than mandated—a distinction that significantly shapes the experience of volunteering (Reference Kampen and TonkensKampen and Tonkens, 2019).

Organizations were identified through a combination of previous research (Reference Grubb, Holstein, Qvist and HenriksenGrubb et al., 2022) and expert guidance from the Danish Institute for Voluntary Effort. A purposeful sampling strategy was used to select organizations offering volunteer opportunities to individuals facing multiple forms of social exclusion. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with leaders from each of the three organizations to provide insight into the organizational context—specifically, how volunteering was structured, how participants were recruited and supported.

Vulnerable Marginalized Volunteers

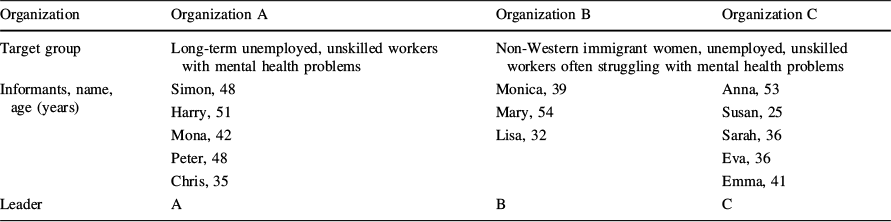

13 informants were recruited through VSW organization leaders and participated in life course interviews. Vulnerability was the primary selection criterion, with labor market exclusion as a shared condition among participants. That is, while all participants were unemployed, many also faced challenges such as low income, social isolation, or limited networks, reinforcing their marginalized status. The study adopts a multidimensional understanding of marginalization and vulnerability (Reference Benjaminsen, Bom, Fynbo, Grønfeldt, Espersen and RamsbølBenjaminsen et al., 2019; Reference LevitasLevitas, 2006), viewing social exclusion as a lack of resources, rights, and opportunities for participation in key arenas—economic, social, cultural, and political. The interviews were biographically inspired, focusing on life histories, pathways into volunteering, aspirations, and organizational experiences (Table 1).

Table 1 Overview of the study sample

Organization |

Organization A |

Organization B |

Organization C |

|---|---|---|---|

Target group |

Long-term unemployed, unskilled workers with mental health problems |

Non-Western immigrant women, unemployed, unskilled workers often struggling with mental health problems |

|

Informants, name, age (years) |

Simon, 48 |

Monica, 39 |

Anna, 53 |

Harry, 51 |

Mary, 54 |

Susan, 25 |

|

Mona, 42 |

Lisa, 32 |

Sarah, 36 |

|

Peter, 48 |

Eva, 36 |

||

Chris, 35 |

Emma, 41 |

||

Leader |

A |

B |

C |

As with any small-scale, qualitative study, there are limitations to the generalizability of my findings. The study draws on a select number of organizational settings and a specific group of marginalized volunteers. While these cases provide rich insights into how valorization occurs when conditions are favorable, they do not capture the full diversity of organizational practices or volunteer experiences across the sector. Rather than making statistical generalizations, the aim is to offer analytical generalizations that enhance our conceptual understanding of the dialectic processes of valorization that foster inclusion in specific organizational settings.

Analytical Strategy

My analytical strategy begins by exploring how VSW organizations cultivate inclusion for individuals on the margins of society, and how this is experienced by the volunteers. Consequently, the analysis centers on the processes through which social inclusion emerge through everyday interactions within these organizational settings.

In the first part of the analysis, I trace how informal, biographically rooted competencies—such as caregiving, patience, or resilience—are discovered and surfaced in organizational contexts. I then show how these competencies are validated through organizational practices, such as trust-building, task delegation, and moral affirmation. Lastly, I examine how volunteers internalize new narratives of self-worth through their continued participation and recognition within the organization.

The analysis conceptualizes this three-part process—discovery, validation, internalization—as a process of valorization, unfolding not through capital conversion or structured interventions, but through informal, dialectic, and interactional dynamics. By attending this dialectic process, the analysis offers a process-oriented account of how VSW organizations function as enabling settings that support social inclusion beyond labor market reintegration.

Analysis

This study explores how voluntary social welfare (VSW) organizations enable social inclusion for marginalized individuals by recognizing and affirming often overlooked informal, biographically rooted competencies. The analysis identifies a three-phase process of valorization: (1) discovery of previously unrecognized skills, (2) reinforcement of self-efficacy through organizational validation, and (3) internalization of new narratives of worth.

The aim of the analysis is twofold. First, it seeks to demonstrate how VSW organizations do more than facilitate the accumulation and conversion of human and social capital—they create environments that foster alternative forms of social inclusion, where participants gain confidence and a renewed sense of self-efficacy. Second, it aims to unpack the process through which valorization unfolds, shaping volunteers’ perceptions of their own value and capabilities.

Discovering Previously Unrecognized Skills

In the first phase of the valorization process, volunteers begin to recognize informal competencies they previously regarded as irrelevant or merely personal. These biographically rooted competencies—such as being a good listener, cooking family meals, or personal resilience—are not newly acquired through volunteering, but capacities that were always present, though unacknowledged or undervalued in dominant institutional contexts. This discovery is sparked through interaction. More specifically, the volunteers in this study do not identify their resources in isolation; rather, they are surfaced through organizational practices—such as being asked to take responsibility, receiving positive feedback, or being treated as capable. This dialectical process—between self-perception and external recognition—is key to how the volunteers begin to see themselves a new. VSW organizations act as enabling environments offering the setting for such recognition to occur.

Several volunteers described how their self-perception was shaped by unemployment before joining the organization. They internalized their labor market failure as personal deficiency, leading to a diminished sense of self-worth. They often spoke of themselves through deficit narratives, internalizing the labor market's judgment that only credentials and productivity define value. This perspective meant that everyday abilities, while deeply ingrained in their lives, were not recognized as “skills.”

This sentiment was echoed by Peter (48), for whom unemployment eroded his once-positive self-image: “I used to be so proactive… but now I just felt lazy and as if I could not get anything done.”

Peter's reflection illustrates how unemployment led study participants to define themselves primarily in terms of what they lacked, rather than in terms of their abilities or strengths. Peter's experience illustrates a broader pattern of how formal economic failure can eclipse informal competencies. The VSW organization's role was to disrupt this narrative and provide an alternative framework for valuing his capabilities, a key first step in the valorization process.

This dynamic was echoed in Monica's case. Her cooking skills, learned informally from her mother, had always been part of her life but were invisible to her as resources. Only when an organizational leader identified these as valuable and entrusted her with responsibility in the kitchen did she begin to see them as meaningful: “[…] it was them who figured out what I was good at. Without them, I couldn't have figured it out myself. So, I looked at myself and said, ‘It's true, I have no education and no former employment. But I can cook—I learned that from my mother’”(Monica). Likewise, Simon's lived experience with depression and anxiety, once seen as a source of stigma, was reframed as a resource for supporting others in distress. His ability to empathize and build trust became a sought-after capacity in the organization. Harry, meanwhile, discovered that his intuitive patience and ability to approach marginalized individuals—traits developed over a lifetime—were not just personal quirks but crucial to the functioning of the café.

Taken together, these cases show how VSW organizations can serve as spaces where previously unrecognized, biographically rooted skills are not only identified but meaningfully valued.

Taken together, these cases show how the discovery of previously unrecognized skills is not a solitary act of reflection but a relational process. Monica's cooking, Simon's lived experience with mental illness, and Harry's intuitive care all became recognized contributions—despite holding little currency in the formal labor market. By affirming competencies beyond formal qualifications, these organizations challenge dominant narratives that equate value with productivity or credentials. Crucially, such recognition is not a one-off moment, but a process sustained through everyday interactions. The organizations in this study served as spaces where previously unrecognized, biographically rooted skills were not only identified but meaningfully valued.

Theoretically, this phase demonstrates the importance of recognition as a precondition for social inclusion. The valorization process begins not with the acquisition of new human capital but with the reframing of existing, biographically rooted capacities. VSW organizations function as enabling environments where informal skills become visible, affirmed, and valued. This illustrates the dialectical mechanism central to valorization: volunteers begin to see themselves anew through the recognition of others, a crucial first step in developing new narratives of worth.

Reinforcing Self-Efficacy Through Organizational Validation

The second phase of the valorization process builds on the initial discovery of informal competencies and involves their organizational reinforcement through trust, responsibility, and meaningful participation. This reinforcement fosters a growing sense of self-efficacy—a belief in one's ability to act meaningfully and autonomously in the world (Reference BanduraBandura, 2000). This process is not driven by the acquisition of new capital, but by the organizational validation of informal, often biographically rooted, skills. Thus, the organizational context plays a pivotal role not only by acknowledging volunteers’ competencies but by validating them through trust and responsibility.

Across the material, study participants described how gradually increasing responsibility transformed fragile recognition into robust confidence. They were given structured yet low-risk tasks, encouraged to try new things, and reassured that mistakes were acceptable. Crucially, self-efficacy is not simply conferred by organizations, nor does it arise solely from internal motivation. It is co-produced through repeated exchanges in which volunteers are not only seen but also relied upon. Leaders emphasized that what mattered was not credentials but participation, presence, and care. As one put it: “When people feel needed—when others see them as capable—they gradually start to feel that they matter again” (Leader C).

Volunteers’ accounts confirmed this mechanism. Being entrusted with tasks, treated as capable, and recognized as contributors, enables volunteers to reframe their self-understanding. The organizational narrative—valuing informal, relational, and biographical skills—offered an alternative to dominant labor market discourses. Sarah (36) reflected: “They don't look at your education or background. They told me, ‘You're really good with people—you listen, you're calm.’ That gave me confidence.” Her story exemplifies how organizational narratives redefined informal traits as competencies, countering deficit discourses. Similarly, Mary emphasized how being entrusted with responsibility, despite lacking qualifications, transformed her self-understanding. Eva described how repeated practice in a supportive setting made her confident enough to speak in public—something she had previously avoided. Monica's story further exemplifies this. Initially unsure of her value, she was repeatedly affirmed for her cooking abilities—skills learned from her mother and previously regarded as mundane. Here she reflects on how her leader's recognition transformed how she viewed herself: “It's all about how others see you. Our old leader found some things in me that I had never thought about myself. She saw that I was good at certain things, like cooking with spices […] Without them, I wouldn't have figured out that I was good at many things” (Monica).

Rather than interpreting this as a form of human capital development, it is more accurately understood as a transformation in Monica's perception of herself and her worth. This reframing of everyday skills as meaningful contributions allowed Monica to see herself as capable and valuable, challenging the assumption that only formally acquired qualifications have worth. Her sense of purpose and capabilities grew, not because she gained new skills, but because her existing ones were recognized and nourished. Thus, the organization successfully crafted messages about how worth is perceived within the organization, not as determined by formal resources but as informal skills accumulated throughout life. This reframing did not emerge in isolation; it was nurtured through daily interactions with peers and staff. The organization affirmed that what counts as competence need not be certified or market-oriented. Further, the organizational leaders framed their role as cultivating these shifts by actively encouraging volunteers to take initiative: “What you water, grows,” explained one (Leader B), underscoring how attentiveness and trust could nurture latent abilities. Rather than demanding performance against external benchmarks, VSW organizations created contexts where informal, relational skills could be exercised, validated, and reinforced. These stories illustrate how the reinforcement of self-efficacy depends not only on praise, but on being entrusted with responsibility and inclusion in meaningful roles. As leader C noted:

“It's not about whether you can produce something, but about how you can contribute positively to another person's life and create dignity there.” (Leader C).

This ethos contrasts with dominant market or welfare institutions, where value is often tied to productivity. Instead, VSW organizations articulate worth as grounded in care, trust, and participation.

Thus, the valorization process identified here does not follow the theoretical logic of capital accumulation and conversion. Instead, it aligns with a capabilities-based understanding of inclusion, where the co-production of self-efficacy is made possible through affirming organizational structures (Reference NussbaumNussbaum, 2011). More specifically, it aligns with Nussbaum's concept of combined capabilities: internal traits such as empathy or resilience become genuine capabilities only when organizational contexts provide the trust and space to exercise them. VSW organizations in this study do not function merely as training sites, but as enabling environments where individuals come to see themselves—and be seen by others—as capable, worthy, and socially valuable. Consequently, the role of the VSW organizations in this study is not necessarily to prepare marginalized volunteers for external success but to create spaces in which they can rediscover their sense of self and begin to imagine new trajectories on their own term. This phase shows how recognition becomes reinforcement: organizational validation stabilizes newly discovered competencies by embedding them in daily practice and trusted responsibility. The mechanism is relational and iterative—volunteers feel capable not only because they are praised, but because they are entrusted, succeed, and are affirmed.

Internalizing New Narratives of Worth

The final phase of the valorization process is the internalization of new narratives of worth. This refers to how volunteers gradually adopt the organization's affirming views as part of their self-understanding—not just as external labels, but as deeply held beliefs about who they are and what they can do. What begins as recognition from others evolves into a transformed self-concept: volunteers come to think, feel, and act as capable and valued community members.

This shift unfolded gradually, through repeated experiences of being seen, trusted, and relied upon. Emma (41), after years of isolation and a disability pension, described how volunteering changed her self-perception: she realized she was “good with people and could help others”—insights that gave her the confidence to engage more fully in social life.

Monicas story illustrate this gradual adoption of the organizations affirming views: “If you look at me before, and if you look at me now, I'm not the same. Before, I was just cooking for my family. Now I cook for 100 people. I've learned I can do it, that I'm good at this. It's like I've become someone else—more proud, more confident. It's part of me now”. (Monica).

She reflects on how her informal competencies become a part of her self-concept—not just something she has, but something she is. Thus, through recognition and repeated affirmation, informal competencies are transformed into internalized narratives of value. Importantly, this unfolds through repeated affirmations across time. The study participants share stories of how the narratives offered to them, over time, settle into how they speak about themselves, their past, and their futures.

These examples show how biographically rooted competencies, once overlooked, became integrated into participants’ identities as valued qualities.

Eva's account demonstrates the culmination of this process. She explained: “As a volunteer I am like the link between immigrant women and their kids in my neighborhood and the social workers [….] I can talk to them in Arabic, and they really need someone to trust. [Leader C] says I'm like a fish in the water—I establish contact and trust so easily. She says I'm so good at connecting with these women […] And I know now that this is just my dream job.” Here, Eva not only received recognition but began to inhabit the organizational narrative, making it central to her identity and aspirations.

Organizational leaders actively shaped the internalization process by articulating and modeling alternative definitions of competence. As one explained: “We help people realize that they have resources in themselves—not necessarily formal qualifications, but things that really matter here. Like being good with people, being inclusive. That's what we value—and they begin to value it, too” (Leader B). This shows how leaders’ framing of competence was not only offered but reinforced in daily practice and ultimately taken up by volunteers as part of their own narratives of worth.

The internalization of new narratives of worth emerges as a transformative and deeply relational process that reshapes volunteers’ self-perception and identity. As demonstrated through the accounts of Emma, Monica, and Eva, this transformation involves a dialectical interplay between external recognition and internal acceptance. Through volunteering, the study participants began to reconfigure their understanding of their own resources. Rather than internalizing dominant narratives that tie value to credentials, employment history, or productivity, they encountered alternative narratives that validated who they were and what they had to offer. These narratives of worth were not imposed from above but co-produced through recognition, trust, and participation. Nor did these narratives remain abstract or peripheral; they became foundational, deeply integrated into volunteers’ sense of self, enabling them to project meaningful futures grounded in newfound self-efficacy. Thus, internalization marks the culmination of a broader process wherein organizational recognition intersects with personal development, illustrating how social inclusion in VSW settings is cultivated through the conscious valorization of lived experience. Figure 1 is a visual representation of the valorization process.

Fig. 1 The valorization process

Taken together, the three phases of valorization—discovery, reinforcement, and internalization—show how VSW organizations foster social inclusion not by creating new forms of capital, but by surfacing, affirming, and embedding informal, biographically rooted competencies. The process is deeply relational and dialectical: volunteers recognize themselves through the recognition of others, gain confidence through organizational validation, and ultimately internalize new narratives of worth. In contrast to deficit-oriented labor market models, this analysis highlights how alternative organizational settings can cultivate empowerment by expanding what counts as valuable and who counts as capable.

Discussion

The concept of valorization offers an alternative to dominant inclusion models that focus on volunteering as a tool for labor market reintegration (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2008; Reference Day and DevlinDay & Devlin, 1998; Reference GranovetterGranovetter, 1973; Reference Handy and GreenspanHandy & Greenspan, 2009; Reference Ruiter and De GraafRuiter & De Graaf, 2009; Reference Cattacin and DomenigCattacin & Domenig, 2014; Reference Peterie, Ramia, Marston and PatulnyPeterie et al., 2019; Reference DederichsDederichs, 2024), potentially overlooking less tangible but equally important forms of value (Reference LamontLamont, 2018). Rather than treating volunteering as a vehicle for capital accumulation (Reference ColemanColeman, 1988; Reference PutnamPutnam, 2000), this study emphasizes how informal attributes—such as empathy, care, or lived experience with vulnerability—can be surfaced and legitimized through everyday interactions within VSW organizations. Crucially, inclusion does not emerge automatically through participation, but through structured informality, trust, and recognition embedded in organizational practice.

The study contributes to the literature by moving beyond frameworks that interpret volunteering primarily to enhance employability (Reference Musick and WilsonMusick & Wilson, 2008; Reference Day and DevlinDay & Devlin, 1998; Reference GranovetterGranovetter, 1973; Reference Handy and GreenspanHandy & Greenspan, 2009; Reference Ruiter and De GraafRuiter & De Graaf, 2009; Reference Cattacin and DomenigCattacin & Domenig, 2014; Reference Peterie, Ramia, Marston and PatulnyPeterie et al., 2019; Reference DederichsDederichs, 2024). Inspired by Nussbaum's (Reference Nussbaum2011) combined capabilities it offers a processual account of how inclusion emerge through activation of internal personal traits—such as care and empathy—through enabling organizational conditions. Together, this perspective illuminates how marginalized individuals can develop new self-understandings and self-efficacy through their participation in VSW organizations.

Importantly, the empirical material shows that such transformative processes are not innate to volunteering itself, but contingent upon the relational and institutional environment in which volunteering takes place. The organizations included in this study were selected for their explicit commitment to inclusive and empowering practices. As such, the study does not claim that all volunteering leads to enhanced self-efficacy or social inclusion—as a small-scale qualitative study based on a limited number of cases, this research is not suited for statistical generalization. Rather, the case logic supports analytical generalization by specifying the organizational and interpersonal mechanisms that enable inclusion—insights that help explain why large-scale studies often yield inconclusive or contradictory finding as they typically assess inclusion through traditional economic indicators like employment rates or income (Reference Spera, Ghertner, Nerino and DiTommasoSpera et al., 2015; Reference Paine, McKay and MoroPaine et al., 2013; Reference Mao and NormandMao & Normand, 2022; Reference Holstein and QvistHolstein & Qvist, 2025). This may overlook more experiential forms of inclusion—such as the development of self-efficacy, self-worth, and social belonging. Future research could explore the conditions under which such processes are likely to emerge, exploring whether the model of valorization applies across different organizational settings, target groups, or welfare regimes.

The insights of this study carry implications for policy. Contemporary welfare policies often assume that volunteering serves as a steppingstone to employment for marginalized groups and promotes it as a cost-effective tool for labor market integration (Reference Kamerāde and PaineKamerāde and Paine, 2014; Reference Paine, McKay and MoroPaine et al., 2013; Reference Espersen, Fridberg, Andreasen and BrændgaardEspersen et al., 2021). While volunteering may support such pathways, this study suggests that its value extends beyond what traditional indicators typically measure. The benefits of volunteering for marginalized individuals—such as increased self-worth and recognition of informal competencies—are not easily captured through conventional metrics like employment status or earnings. This does not mean the benefits are absent, but rather that we may have used tools that are not suited to measuring the full range of inclusion outcomes. Further, the inclusion potential of volunteering lies not solely in volunteering itself, but in the capacity of organizations to create spaces where individuals are seen, heard, and valued. Realizing this potential requires intentional design, relational sensitivity, and a sustained commitment to inclusion on the volunteer's own terms—conditions that cannot be taken for granted across the voluntary sector.

Conclusion

Drawing on interviews with volunteers and organizational leaders, this study has introduced the concept of valorization to theorize how voluntary social welfare organizations foster social inclusion for marginalized individuals—not through the accumulation of formal capital, but through the recognition and affirmation of informal, biographically rooted competencies. By analyzing the dialectical interplay between volunteers and enabling organizational settings, the study demonstrates that inclusion is not a static outcome of participation, but a relational process that unfolds through three interrelated phases: 1) the discovery of previously unrecognized skills, 2) the organizational reinforcement of self-efficacy, and 3) the internalization of new narratives of worth.

The study has shown that inclusion is co-constructed in specific organizational contexts that affirm value not based on economic utility, but on human significance. This process unfolds through trust-based relationships with responsibilities. These dynamics reconfigure how marginalized individuals understand their own worth, offering forms of recognition that are rarely available in formal labor markets or welfare institutions.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the members of the research group CASTOR for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aalborg University.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.