Introduction

Food waste contributes to resource inefficiencies, greenhouse gas emissions, and economic losses throughout the supply chain (FAO 2013). Reducing food waste is a critical challenge, particularly for fresh produce such as apples, which are highly perishable and susceptible to spoilage due to enzymatic browning (Buzby and Hyman Reference Buzby and Hyman2012). Food waste reduction technologies, such as gene editing and all-natural fruit sprays, have recently gained attention as potential solutions. For example, gene editing alters the genetic expression of apples to delay browning (Waltz Reference Waltz2016), while all-natural fruit sprays create a protective coating to slow ripening without genetic modification (Mialon et al. Reference Mialon, Swinburn, Wate, Tukana, Sacks and Snowdon2021).

Despite the potential of food waste-reducing technologies, consumer acceptance remains uncertain and highly dependent on perceptions of biotechnology, food safety, and sustainability (Lusk et al. Reference Lusk, Roosen and Bieberstein2014). Public attitudes toward gene editing vary, with concerns about health risks, ethical considerations, cultural worldview, the reason for using gene editing, and regulatory transparency influencing adoption (Kemper et al. Reference Kemper, Popp, Nayga and Kerr2018; McFadden et al. Reference McFadden, Anderton, Davidson and Bernard2021; Muringai, Fan, and Goddard Reference Muringai, Fan and Goddard2020; Shew et al. Reference Shew, Nalley, Snell, Nayga and Dixon2018). Conversely, all-natural spray coatings may appeal to consumers seeking minimally processed food but may also raise questions about efficacy and labeling requirements (Colson et al. Reference Colson, Huffman and Rousu2011). Recent research highlights the role of consumer segmentation in food waste reduction, showing that preferences for food waste technologies are shaped by demographic and behavioral characteristics (Dsouza et al. Reference Dsouza, Fang and Kemper2023).

Given these challenges, understanding consumer preferences for food waste-reducing technologies is essential for informing industry adoption strategies, regulatory policies, and targeted marketing efforts. The objective of this study was to examine consumer preferences for delayed-ripening apples using gene editing and all-natural fruit sprays. While all-natural sprays offer an alternative to gene editing, consumer demand for these technologies has not been extensively studied. Understanding the differences in acceptance between the two technologies is essential for promoting the adoption of waste-reducing technologies. Specifically, this research aims to 1) assess consumer preference for gene-edited apples versus spray-treated apples, 2) estimate willingness to pay (WTP) for each technology to determine price sensitivity and consumer acceptance, 3) identify consumer segments to understand attitudinal, demographic, and behavioral factors influencing adoption, and 4) evaluate the role of food waste reduction in shaping consumer decision-making.

To complete the study objectives, we employ a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to evaluate consumer preferences and provide empirical evidence for WTP for 1) gene-edited apples, 2) spray-coated apples, treated with an all-natural spray, and 3) an untreated apple that did not include a food waste-reducing technology. Additionally, we use Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to identify distinct consumer profiles based on preferences for biotechnology and natural food preservation and examine the heterogeneity of market demand. By examining consumer acceptance of food waste-reducing technologies, this study provides actionable information for producers, retailers, and policy makers seeking to enhance food sustainability while addressing consumer concerns related to biotechnology and natural preservation methods. Our results highlight that, in general, consumers are willing to pay a premium for gene-edited and spray-coated apples over conventional apples that are untreated. However, we also show that the degree to which consumers are willing to pay this premium depends on whether they are concerned about food waste.

Background

Reducing food waste is a growing priority for consumers, policy makers, and industry stakeholders due to its environmental, economic, and social consequences. Apples, in particular, are highly susceptible to enzymatic browning, leading to significant spoilage and loss throughout the supply chain (Buzby and Hyman Reference Buzby and Hyman2012). The Arctic Apple is an example of an apple developed through gene editing using RNA interference (RNAi) technology, specifically targeting polyphenol oxidase (PPO) genes to prevent browning. Applying technology like RNAi highlights the significance of the Arctic Apple as a successful case of modifying fruit traits without introducing foreign DNA (Martín-Valmaseda et al. Reference Martín-Valmaseda, Devin, Ortuño-Hernández, Pérez-Caselles, Mahdavi, Bujdosó and Alburquerque2023).

While several technologies have been developed to mitigate food waste, consumer acceptance of these innovations remains a key determinant of market success. The acceptance of gene-edited foods is influenced by public perception of biotechnology, emphasizing the importance of consumer awareness and understanding of gene-editing technologies to improve acceptance (Jacobson et al. Reference Jacobson, Bondarchuk, Nguyen, Canada, McCord, Artlip and Klocko2023). Similar patterns emerge from the work of Krasovskaia et al. (Reference Krasovskaia, Rickard, Ellison, McFadden and Wilson2024), who found that consumer purchase likelihood is notably lower for foods with gene-edited ingredients, regardless of whether claims emphasized health or environmental benefits. These results reinforce the idea that wariness toward gene editing persists due to limited consumer understanding and misinformation. Labeling transparency and targeted consumer education are, therefore, essential for improving trust and acceptance of gene-edited food products. This study examines consumer preferences for delayed ripening gene-edited apples and spray-coated apples, contributing to the growing body of research on food waste reduction and biotechnology acceptance.

Consumers value freshness, appearance, and extended shelf life when purchasing fresh produce, particularly apples (Wakeling and Macfie Reference Wakeling and Macfie1995). Technologies that delay ripening can help reduce waste by maintaining visual appeal and reducing spoilage, potentially leading to higher consumer WTP for apples with enhanced shelf life (Dsouza et al. Reference Dsouza, Fang and Kemper2023). Previous studies suggest that consumers generally support food technologies that provide tangible benefits, such as reduced waste and increased convenience (Lusk et al. Reference Lusk, Roosen and Bieberstein2014). However, acceptance varies based on perceived naturalness, safety concerns, and labeling transparency (Muringai et al. Reference Muringai, Fan and Goddard2020). Understanding how these factors influence consumer decision-making is essential for promoting the adoption of these innovations.

Gene-editing techniques offer a precise and targeted approach to enhancing food characteristics, including browning reduction in apples (Waltz Reference Waltz2016). Unlike traditional genetic modification, gene editing does not introduce foreign DNA, a distinction that may influence consumer acceptance (Shew et al. 2018). Research on consumer attitudes toward gene editing in food is mixed – some consumers recognize its benefits for sustainability and food security, while others remain skeptical due to concerns about regulation, ethics, and long-term safety (Muringai et al. Reference Muringai, Fan and Goddard2020). Studies suggest that trust in regulatory bodies, science communication, and transparent labeling are crucial factors in increasing consumer confidence in gene-edited foods (Colson et al. Reference Colson, Huffman and Rousu2011). Given these dynamics, further research is needed to assess consumer segmentation and identify potential adopters of gene-edited apples.

Natural food preservation techniques, such as spray-coated fruit, have gained interest as a non-genetic solution to extending shelf life and reducing waste. Unlike gene-edited alternatives, these sprays do not alter an apple’s genetic makeup, which may appeal to consumers who prefer “clean-label” products (Mialon et al. 2021). Prior studies suggest that consumers are more willing to accept “natural” food technologies, particularly those marketed as organic, minimally processed, or free from synthetic additives (Lusk et al. Reference Lusk, Roosen and Bieberstein2014). However, acceptance depends on perceived effectiveness, labeling clarity, and potential impact on taste and texture (Colson et al. Reference Colson, Huffman and Rousu2011). Wilson and Miao (Reference Wilson and Miao2025) show that consumers’ preferences for food safety and waste reduction are significantly shaped by their risk preferences, and that labeling clarity plays a key role in driving choices for perishable products. Their findings support the need for accurate labeling of preservation technologies like spray-coating to build consumer confidence. Broeckling and McFadden (Reference Broeckling and McFadden2024) highlight that public sentiment toward food technology is not only shaped by the presence of biotechnology but also by how the technology is labeled and framed, which has direct implications for how all-natural and gene-edited claims are communicated to consumers. While spray-coating offers an alternative to gene-edited fruit, consumer demand for these technologies has not been extensively studied, highlighting the need for further research.

Despite the availability of food waste reduction technologies, gaps remain in understanding consumer trade-offs between gene-edited and spray-coated apples. This study provides empirical evidence on the WTP for delayed-ripening technologies in apples, using latent class segmentation to identify distinct consumer profiles based on preferences for biotechnology and natural food preservation. The findings will inform industry adoption strategies, regulatory policies, and marketing approaches aimed at reducing food waste while aligning with consumer values.

Data and methods

The survey was administered online in April 2024 through Qualtrics Panels. Qualtrics recruited U.S. participants using quota sampling to provide a socio-demographically balanced sample of primary household grocery shoppers. Quotas were applied to education (U.S. general population, 65% no college degree, 35% four-year degree or higher) and gender (primary household shoppers, 60% female, 40% male), based on national benchmarks for food shoppers. Screening questions ensured that respondents were age 18 or older and had consumed apples within the past 30 days. A total of 413 qualified responses were collected for this project. The study received IRB approval from the University of Arkansas (IRB #2404536397). The full survey instrument, including informed consent, attribute descriptions, and choice tasks, is provided in Appendix A.

The sample was broadly similar to the U.S. adult population across several demographic indicators, but because our target population was primary household shoppers, important differences were observed. While the sample overrepresents individuals with higher education, other characteristics such as gender, age, and income fall within typical national distributions. For example, the national median household income was approximately $74,580 in 2022 (U.S. Census Bureau 2023b). Women in our sample (40%) also align with national patterns in educational attainment, with 39.0% of women aged 25 and older having completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 36.2% of men (U.S. Census Bureau 2023a). In our sample, 38% of respondents reported having at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 35.7% of U.S. adults aged 25 and over in 2022 (U.S. Census Bureau 2023a). Our LCA results also confirmed that these demographic factors were not significant in our model.

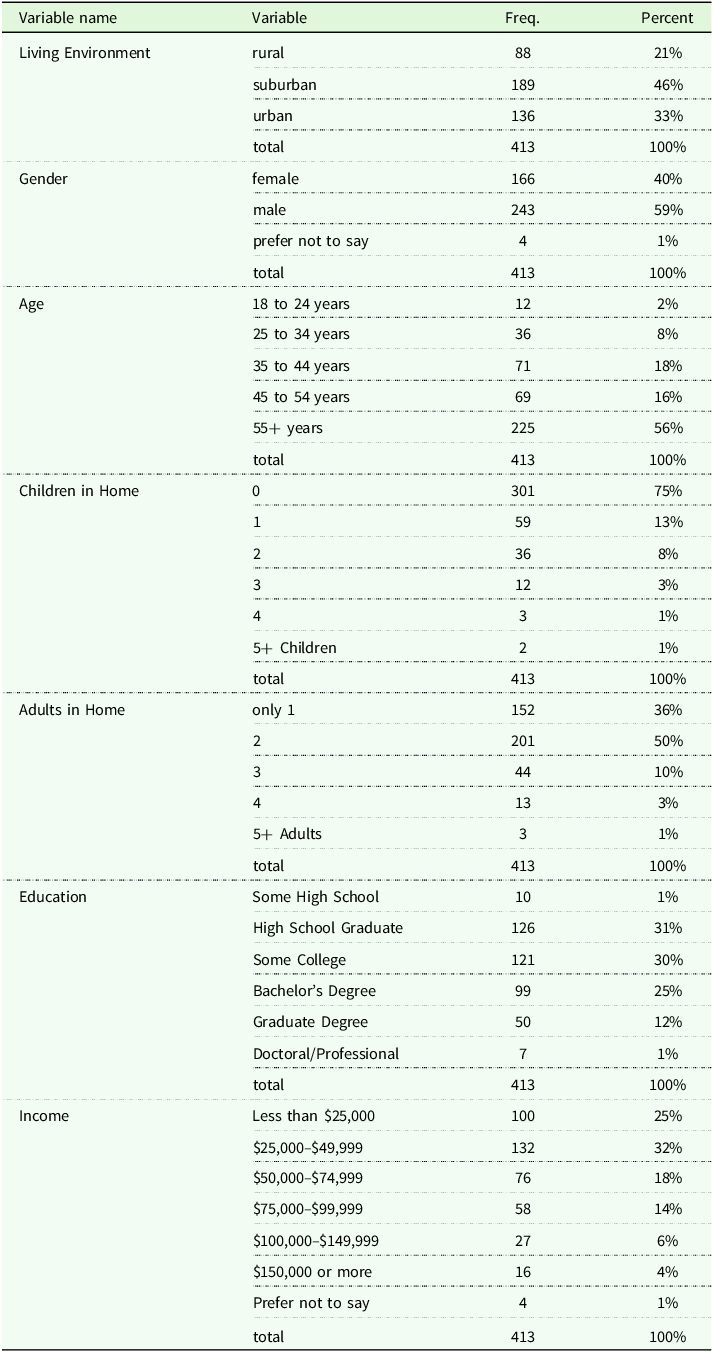

The online DCE was used to assess consumer preferences for food waste-reducing technologies. The survey collected demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral data, as well as responses to choice scenarios evaluating WTP for apples treated with one of three technologies: 1) Gene-Edited (apples designed to reduce browning), 2) Spray-Coated (an all-natural edible coating to delay ripening and spoilage) and 3) Untreated (control group, untreated apples). The sample was recruited using Qualtrics’ online consumer panel, ensuring diversity in geographic region, age, gender, income, and education levels. All 413 responses were used in the choice experiment and WTP estimation. However, because we did not force respondents to answer all follow-up survey questions, only 400 valid responses were used for the post-DCE analyses. Data were cleaned to remove incomplete surveys and those failing quality checks. Table 1 summarized our sample.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Note: Participants were recruited using quota sampling to approximate the U.S. population of primary grocery shoppers across key demographic characteristics. Additional details and national comparisons are provided in the main text.

Choice experiment and econometric methods

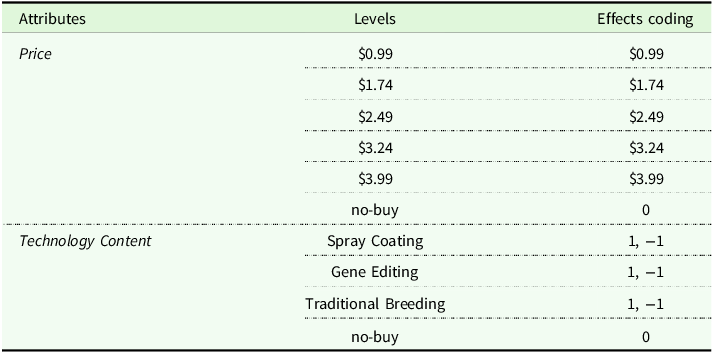

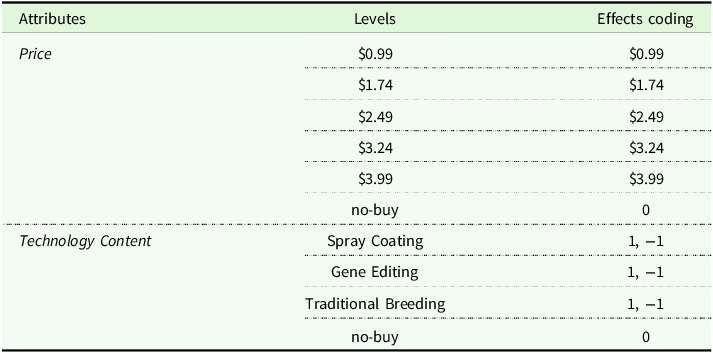

The DCE framework was employed to estimate consumer WTP for each food waste reduction technology. Respondents were presented with a series of choice tasks, each containing three apple options that varied by: 1) Technology used (Gene-Edited, Spray-Coated, or Untreated), and Price per pound ($1.99, $2.49, $2.99, or $3.49). Apple prices were obtained from the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service’s My Market News portal, retail prices reports (USDA 2025) and selected to represent a range on typical apple prices consumers would experience in retail settings. The choice experiment used an orthogonal and balanced design without blocking. Respondents completed nine choice tasks, selecting their preferred option in each scenario. Respondents evaluated all nice choice tasks in the design, with paired comparison presented randomly to control for order effects. The attributes and levels used in the DCE are summarized in Table 2 and an example choice task is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Attributes and levels in choice experiment

Note: effects coding of categorical variables involves entering a “1” when the attribute level is present in the design, a “−1” when the level is not present, and a “0” when the no-buy option is selected. The choice experiment employed an orthogonal and balanced design without blocking. Each respondent evaluated all nine choice tasks, with paired comparisons and alternative positions randomized to control for order effects.

Figure 1. Example choice task, cheap talk script, and instructions.

Note: Respondents were first shown a cheap talk script, then a brief prompt before beginning the choice experiment. Cheap Talk Script: Studies show that people tend to act differently when they face hypothetical decisions. In other words, they say one thing in a lab setting and do something different in a real-world setting. For example, some people would say they would choose an item in a hypothetical situation, but when faced with non-hypothetical or real choices (e.g., in a supermarket), they will not actually choose the item that they said they would choose. We want you to behave the way you would if you had to choose between products in a retail store. Prompt: Imagine you are shopping for apples, and you can select from two apples below. Other than the price and the technology used to reduce browning (gene-editing or all-natural spray), the apples are identical in every other way.

Consumer preferences for food waste-reducing technologies were analyzed using a Generalized Mixed Logit (GMXL) model in WTP space, implemented in NLOGIT 6. This modeling framework offers several advantages over traditional preference-space models, particularly in capturing heterogeneity in consumer valuation. By directly modeling WTP, the GMXL approach provides more precise estimates of how much consumers are willing to pay for each technology (Rose and Masiero Reference Rose and Masiero2010). The model accounts for individual differences by incorporating random coefficients, allowing for greater flexibility in capturing preference heterogeneity (Hole and Kolstad Reference Hole and Kolstad2011). Additionally, correlated random parameters were included to enhance model robustness in evaluating trade-offs between attributes. To ensure accurate estimation of categorical variables, effects coding was applied, facilitating the interpretation of relative WTP values. The final model specification treated technology choice as a random parameter, while price was fixed, following best practices in WTP estimation. This data is summarized in Table 3. Our utility function, first provided in preferences space:

where i is the individual respondent, j refers to three options available in the choice set, and t refers to the choice task. The alternative-specific constant (NONE) is effects-coded, taking the value 1 for the no-buy option and -1 otherwise. PRICE is treated as a continuous variable represented by the five experimentally designed price levels ($0.99, $1.74, $2.49, $3.24, and $3.99). The non-price attributes of spray-coated (SPRAY), gene-edited (EDIT), and untreated (UNTREAT) are effects-coded variables taking the value 1 if the technology is present and the value of −1 if in the absence of the technology, and 0 for the no-buy option. Finally, ϵijt is an unobserved random term that is distributed following an extreme value type I (Gumbel) distribution, i.i.d. over alternatives, and independent of α and β.

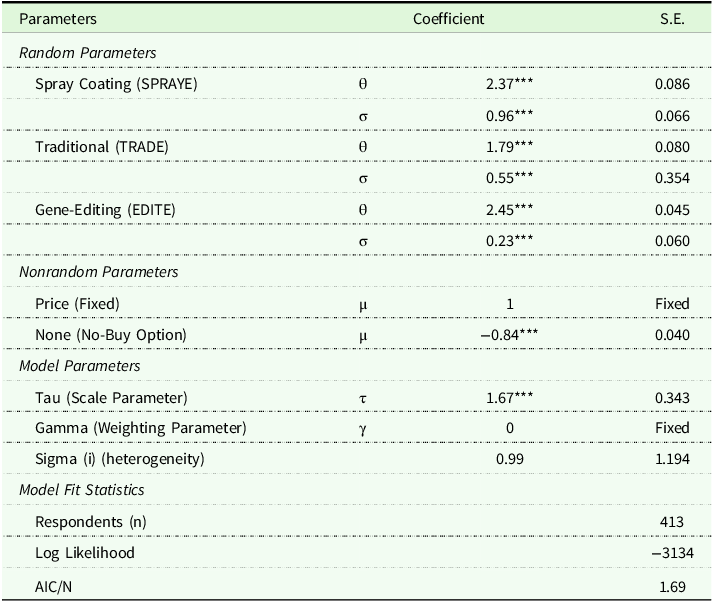

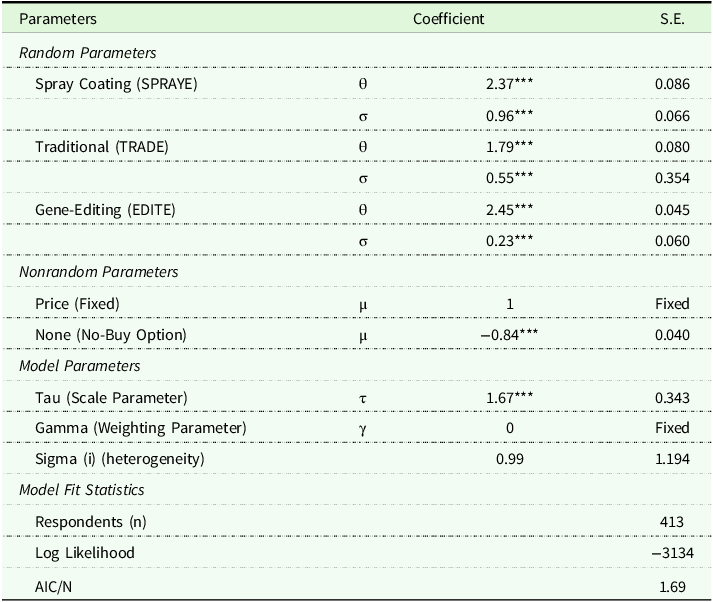

Table 3. Willingness to pay space model results

Note: *,**, and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5, and 1 percent levels. Estimates obtained from WTP space model in NLOGIT 6. The model includes random parameters for technology choice and a fixed price coefficient. The use of Halton sequences was applied for efficient simulation, and the model accounts for preference heterogeneity through correlated random parameters.

Next, we relaxed the assumption of fixed price coefficients and specified our utility in WTP Space (Scarpa et al. Reference Scarpa, Thiene and Train2008; Thiene and Scarpa Reference Thiene and Scarpa2009) to allow the price to be random. Preference space utility (equation 1) can be written in WTP Space as follows (Greene Reference Greene2012):

The parameters for the non-price attributes (θi = βi/ α) represent individual-specific WTP estimates modeled as random coefficients following a multivariate normal distribution. Equation (2) was estimated with correlated errors and 1,000 Halton draws were used to provide a more accurate simulation for the random parameters (Train Reference Train2009). With this new utility specification, the estimates are directly considered the willingness to pay values.

To further examine differences in consumer preferences, a LCA was conducted, using estimated WTP values and demographic characteristics to identify distinct consumer segments. Model selection was guided by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), ensuring an optimal balance between model fit and complexity. Entropy scores were also assessed to evaluate classification quality, with higher entropy values indicating clearer segmentation. In addition to statistical fit measures, the segmentation structure was evaluated for its economic and behavioral interpretability to ensure meaningful differentiation among consumer groups. Based on these criteria, a three-segment solution was selected, revealing significant variation in consumer preferences for gene-edited and all-natural food waste reduction technologies.

The LCA framework assumes that individuals belong to latent classes C and that within each class (segment), responses follow a unique parameter distribution. The probability that an individual i belongs to class c is given by:

where λc is the class-specific intercept determining the probability of class membership. For each latent class c, the probability of observing choice j from choice set t follows the multinomial logit model:

$$P\left( {{Y_{ijt}} = 1\;|\;{C_i} = c} \right) = {{exp\left( {U_{{ijtc}}} \right)} \over {\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^J e xp\left( {U_{{ijtc}}} \right)}}$$

$$P\left( {{Y_{ijt}} = 1\;|\;{C_i} = c} \right) = {{exp\left( {U_{{ijtc}}} \right)} \over {\sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^J e xp\left( {U_{{ijtc}}} \right)}}$$

where Uijtc is the utility of individual i choosing alternative j in scenario t, given membership in class c.

Statistical analysis

A series of statistical tests were conducted to compare WTP estimates and demographic characteristics across the identified consumer segments. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences in mean WTP values among the three segments. To further explore pairwise differences, post-hoc Bonferroni and Scheffe tests were applied, identifying which segments exhibited statistically distinct WTP patterns. Additionally, chi-square tests were used to assess differences in categorical demographic variables, while t-tests were performed to compare continuous variables across segments. All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata 18 and NLOGIT 6.

Results

This section presents the findings from the WTP Space model and LCA, examining consumer preferences and segmentation for food waste reduction technologies. The WTP estimates provide insights into consumer valuation of gene-edited and spray-coated apples, while the LCA reveals distinct consumer segments with varying levels of adoption and concern for food waste. Additionally, ANOVA and post-hoc statistical tests assess the significance of differences across segments, highlighting key demographic and behavioral factors influencing preferences. The results inform targeted marketing strategies and policy interventions to enhance adoption of food waste-reducing technologies.

Willingness to pay for food waste reduction technologies

The WTP Space model provided estimates for consumer preferences for gene-edited, spray-coated, and untreated apples. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that consumers exhibited the highest WTP for gene-edited apples ($2.45/lb, p < 0.001, 95% CI: $2.36 - $2.54), followed by spray-coated apples ($2.37/lb, p < 0.001, 95% CI: $2.20 - $2.53), with the lowest WTP observed for untreated apples ($1.73/lb, p < 0.001, 95% CI: $1.63 - $1.94). The significant standard deviations of the WTP distributions suggest heterogeneity in consumer preferences, for spray-coated apples (SD = 0.96, p < 0.001), untreated apples (SD = 0.55, p < 0.001), and gene-edited apples (SD = 0.23, p < 0.001). Next, a LCA is performed to investigate further the heterogeneity in consumer preferences.

Consumer segmentation: latent class analysis findings

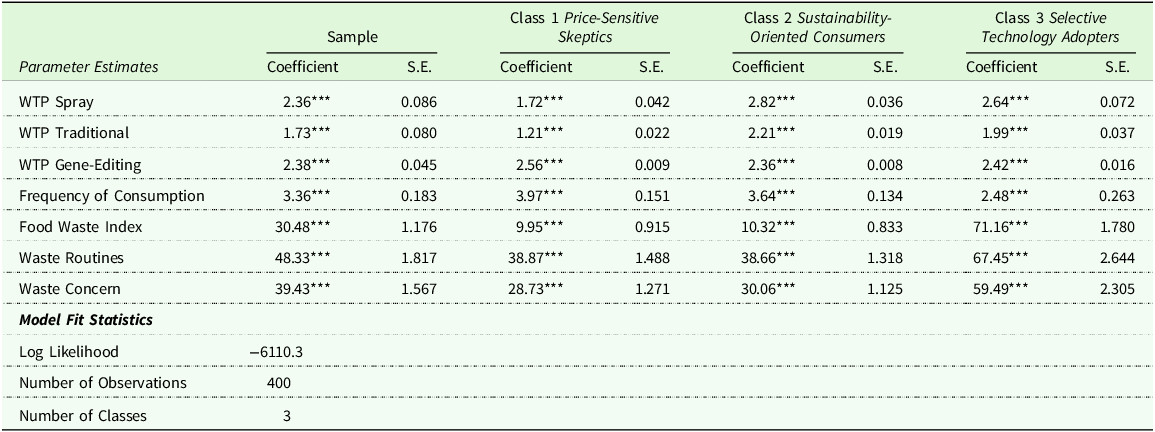

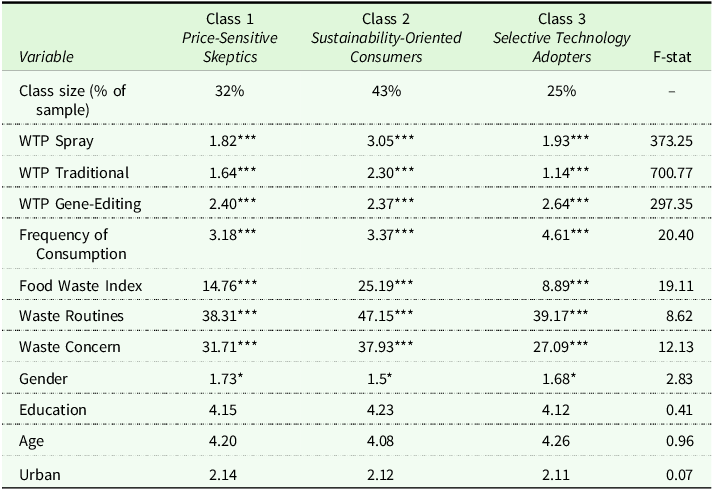

LCA identified a three-segment solution, highlighting the heterogeneity in consumer preferences for food waste-reducing technologies. AIC and entropy scores supported the selection of three segments, which indicated a statistically valid and interpretable segmentation. The consumer segments revealed distinct WTP patterns and demographic characteristics:

Segment 1 (Price-Sensitive Skeptics, 32% of sample): Consumers in this segment exhibited the lowest WTP for all technologies, with an average WTP for spray-coated apples at $1.82/lb and for untreated apples at $1.64/lb. They also had the lowest concern for food waste (31.7%) and moderate waste reduction routines (38.3%). This segment tended to be older and more price-sensitive, with an average education level of 4.15, indicating that, on average, respondents in this segment had completed vocational or technical college, with some having attained a bachelor’s degree, based on a 7-point scale where 1 = elementary school and 7 = doctorate or PhD. Gender composition skewed toward males (1.73, where 1 = female, 2 = male).

Segment 2 (Sustainability-Oriented Consumers, 43% of sample): This group had the highest WTP for both spray-coated apples ($3.05/lb) and untreated apples ($2.30/lb), aligning with higher food waste concern (37.9%) and waste reduction routines (47.2%). Their frequency of apple consumption (3.37 times per week) was near the sample average. Demographically, this segment had the highest education level (4.23), suggesting a greater awareness of sustainability issues.

Segment 3 (Selective Technology Adopters, 25% of sample): Consumers in this group exhibited the highest WTP for gene-edited apples ($2.64/lb) and were the most frequent apple consumers (4.61 times per week). While their WTP for spray-coated apples ($1.93/lb) was moderate, they preferred gene-edited apples, overall. This group had the lowest concern for food waste (27.1%) but still engaged in waste reduction behaviors at a moderate level (39.2%).

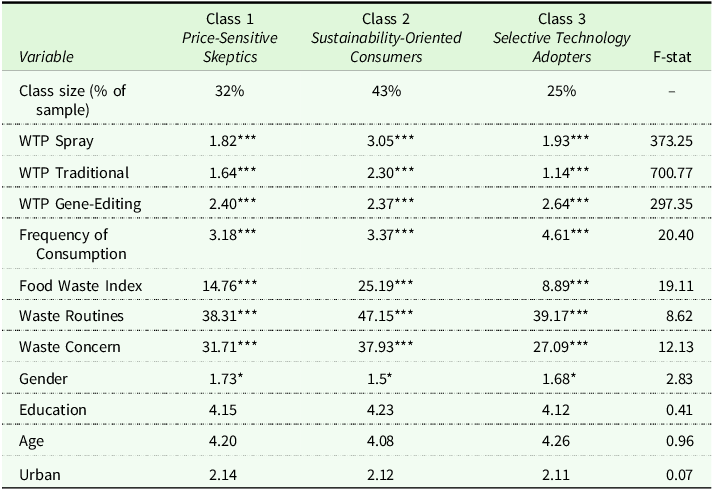

The ANOVA results confirmed significant differences in WTP across the three consumer segments (F = 375.58, p < 0.001 for spray-coated apples; F = 708.44, p < 0.001 for untreated apples; F = 299.53, p < 0.001 for gene-edited apples). Post-hoc Bonferroni and Scheffe tests identified significant pairwise differences, with Segment 2 Sustainability-Oriented Consumers exhibiting the highest WTP across all technologies, while Segment 3 Selective Technology Adopters displayed the strongest preference for gene-edited apples. Chi-square tests confirmed statistically significant differences among segments in terms of education (χ2 = 6.51, p < 0.05), age (χ² = 0.26, p = 0.881), and food waste concern (χ² = 25.12, p < 0.001). This data is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Latent class analysis results

Note: *,**, and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5, and 1 percent levels. LCA was conducted using a generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) approach with three latent segments (C = 3) to identify consumer segments based on willingness-to-pay (WTP) for food waste reduction technologies. Model selection was guided by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and entropy scores to ensure an optimal balance between model fit and interpretability. Each segment was characterized based on estimated mean values for WTP, food waste concern, and consumption behaviors. The final model exhibited convergence stability with a log-likelihood of −6110.3 based on 400 observations after excluding incomplete responses that lacked food waste concern (fw_i) data.

Statistical analysis of segment differences

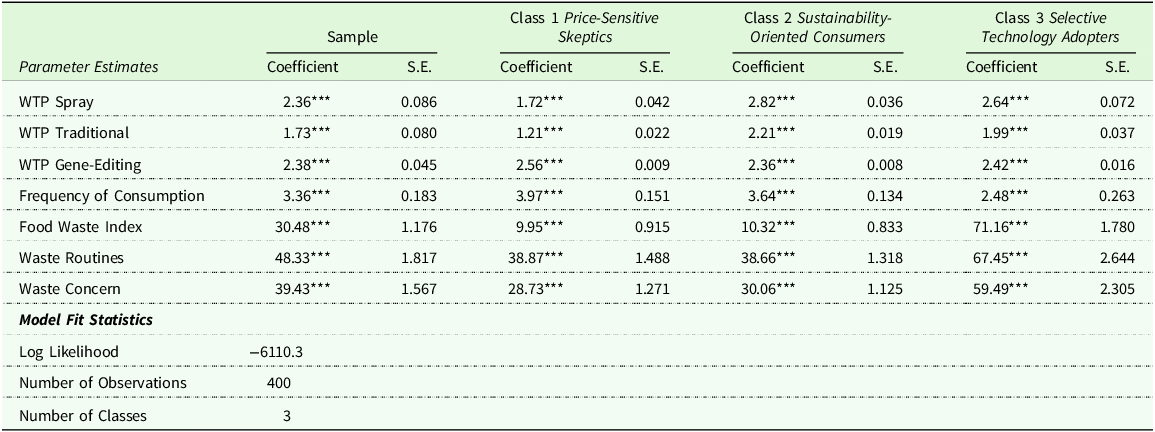

Coefficients reported in Table 4 in the previous section reflect model-estimated conditional means from the LCA. For the results in this section, as reported in Table 5, values represent empirical means based on observed responses grouped by most likely segment membership. Differences between results in Tables 4 and 5 arise due to individual-level variation and the probabilistic nature of segment assignment in the LCA model. To determine whether the differences in WTP and behavioral measures were statistically significant across consumer segments, one-way ANOVA tests were conducted. Results of these tests are summarized in Table 5. WTP for spray-coated apples was significantly different across segments (F = 373.25, p < 0.001). Post-hoc Bonferroni and Scheffe tests confirmed that Segment 2 had significantly higher WTP than both Segments 1 and 3 (p < 0.001). WTP for untreated apples was also significantly different (F = 700.77, p < 0.001), with Segment 2 showing the highest WTP (p < 0.001). WTP for gene-edited apples showed significant differences across segments (F = 297.35, p < 0.001). Segment 3 had the highest WTP, significantly greater than Segments 1 and 2 (p < 0.001). This data is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Latent class segment mean results

Note: *,**, and *** indicate significance at the 10, 5, and 1 percent levels. The segment mean results were derived from a LCA model using Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) in Stata. The LCA model categorized respondents into three distinct segments based on their WTP for different food waste-reducing technologies (spray coating, traditional breeding, and gene editing), frequency of consumption, and food waste-related behaviors. To test for significant differences across the segments, we conducted Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for each variable, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni and Scheffé tests where appropriate. The F-statistic and corresponding p-values indicate whether mean differences between segments are statistically significant. Bartlett’s test for equal variances was performed to verify homogeneity assumptions.

Frequency of consumption (F = 20.40, p < 0.001) was highest in Segment 3, reinforcing the idea that frequent consumers may be more open to innovation. Food waste concern (F = 12.13, p < 0.001) and waste reduction routines (F = 8.62, p < 0.001) were significantly different, with Segment 2 demonstrating the strongest concern and most proactive behaviors. Education and age differences were not significant, indicating that preference segmentation is primarily driven by attitudes and consumption behaviors rather than demographic characteristics. These statistical tests confirm that consumer segmentation is meaningful and reflects distinct preferences, attitudes, and behaviors toward food waste reduction technologies.

Implications for technology adoption

The segmentation results highlight that consumer adoption of food waste-reducing technologies is not uniform. Sustainability-oriented consumers (Segment 2) exhibit strong support for both gene-edited and spray-coated apples, making them the most likely early adopters. Price-sensitive skeptics (Segment 1), who exhibit the lowest WTP for all apples in the experiment, may require price-based incentives, subsidies, or discount programs to encourage adoption. Finally, selective technology adopters (Segment 3) demonstrate a clear preference for gene-edited apples, suggesting that targeted educational campaigns emphasizing the scientific basis and safety of gene-edited apples could potentially increase its acceptance, though this would require validation through future intervention studies.

Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to understanding consumer preferences for food waste-reducing technologies, particularly gene-edited and spray-coated apples. The results from the WTP Space model indicate that consumers, on average, assign the highest WTP to gene-edited apples, followed by spray-coated apples, with untreated apples having the lowest WTP. This suggests a general acceptance of technological interventions aimed at reducing food waste, albeit with differences in valuation. LCA revealed three distinct consumer segments that vary in their valuation and behavioral attitudes toward food waste reduction. Price-Sensitive Skeptics (Segment 1) exhibited the lowest WTP for all technologies and demonstrated lower concern for food waste. Sustainability-Oriented Consumers (Segment 2) showed the highest WTP across all technologies, with the strongest food waste concerns and waste reduction behaviors. Selective Technology Adopters (Segment 3) were unique in their preference for gene-edited apples over the other two options, while maintaining moderate engagement in waste reduction behaviors.

The willingness-to-pay (WTP) estimates observed in this study – $1.23/lb for gene-edited apples and $0.86/lb for spray-coated apples among Segment 3 consumers – are consistent with price premiums seen in the fresh produce market for apple innovations and shelf-life extending technologies. For example, Honeycrisp apples regularly sell at a premium of $0.90–$1.00/lb over baseline varieties such as Gala or Fuji (U.S. Apple Association 2022). Similarly, edible coatings like Apeel are known to yield retail price premiums of 10–20%, particularly in avocados and citrus. Dsouza et al. (Reference Dsouza, Fang and Kemper2023) report substantial WTP for Apeel-coated bananas and tomatoes due to their perceived sustainability and quality benefits. Supporting studies demonstrate that natural coatings enhance shelf life and microbial stability (Rashid et al. Reference Rashid, Ahmed, Ferheen, Mehmood, Liaqat, Ghoneim and Rahman2023; Saba et al. Reference Saba, Darvishi, Zarei and Sogvar2023), while consumer preferences for natural, health-promoting attributes significantly boost acceptance of such technologies (Rombach et al. Reference Rombach, Dean and Baird2022). These preferences are especially pronounced among younger and environmentally engaged consumers (Giammona et al. Reference Giammona, Pitarresi, Palumbo, Maraldi, Scarponi and Rizzo2018). Taken together, our WTP findings fall within a plausible and market-relevant range, reinforcing the value of food waste-reducing innovations that align with consumer priorities for quality, health, and sustainability.

These findings differ from many previous studies that have reported consumer skepticism toward gene-edited or genetically modified foods, often resulting in discounted WTP (Paudel et al. Reference Paudel, Kolady, Just and Sluis2023; Uddin et al. Reference Uddin, Gallardo, Rickard, Alston and Sambucci2022). However, emerging evidence suggests that acceptance of gene-edited foods may increase when the perceived benefits are clearly communicated – particularly those related to health, sustainability, or quality improvements (Krasovskaia et al. Reference Krasovskaia, Rickard, Ellison, McFadden and Wilson2024; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Gallardo, Canales, Atucha, Zalapa and Iorizzo2024). In our study, Segment 3 consumers showed a distinct preference for gene-edited apples, which may reflect a broader willingness to adopt food technologies aligned with societal values such as waste reduction and health. Prior work indicates that trust in food systems, attitudes toward technology, and consumer neophobia significantly shape such preferences (Farid et al. Reference Farid, Cao, Lim, Arato and Kodama2020; McFadden et al. Reference McFadden, Anderton, Davidson and Bernard2021; Vásquez et al. Reference Vásquez, Hesseln and Smyth2022). These results reinforce the importance of tailored communication strategies that emphasize the specific advantages of gene-editing – such as reduced spoilage or nutritional enhancement – while addressing concerns about safety and transparency. Conversely, the relatively lower valuation of spray-coated apples suggests that this technology may lack similar salience in the eyes of consumers, underscoring the need for improved outreach regarding its efficacy and natural composition.

The significant differences in WTP across segments suggest that pricing strategies, marketing communications, and policy interventions may need to be tailored to different consumer segments. Price-sensitive consumers may require financial incentives or subsidies to adopt food waste-reducing technologies, while sustainability-driven consumers may respond best to messaging emphasizing environmental benefits. However, our findings point in these general directions and such interventions remain hypotheses to be tested in future research. The findings also highlight that demographic factors such as education and income were not the primary determinants of segmentation, reinforcing the importance of behavioral and attitudinal drivers in food technology adoption.

Conclusion

This study examined consumer preferences for food waste reduction technologies, specifically gene-edited and spray-coated apples, using discrete choice methods. The results demonstrate that consumer preferences are not homogeneous but vary significantly across distinct market segments. Consumers exhibited the highest WTP for gene-edited apples, followed by spray-coated apples, with untreated apples receiving the lowest valuation. The LCA identified three consumer segments: Price-Sensitive Skeptics, who had the lowest WTP and were least engaged in food waste reduction behaviors; Sustainability-Oriented Consumers, who demonstrated the highest WTP and strongest environmental concerns; and Selective Technology Adopters, who favored gene-edited apples over other options. These findings reinforce the importance of tailoring marketing strategies and policy interventions to align with the preferences and values of different consumer groups. Our results align with prior findings emphasizing the importance of consumer awareness and understanding of gene editing technologies and the need for educational efforts to improve acceptance (Jacobson et al. Reference Jacobson, Bondarchuk, Nguyen, Canada, McCord, Artlip and Klocko2023).

Understanding nuanced consumer concerns surrounding gene editing in food production enhances acceptance. Through a market segmentation analysis, researchers can segment consumer attitudes to identify those who may reject gene-edited products based on a range of factors, allowing stakeholders to tailor educational and outreach efforts to address these specific fears (Uddin et al. Reference Uddin, Gallardo, Rickard, Alston and Sambucci2022). Our results suggest that the successful adoption of food waste-reducing technologies requires targeted engagement strategies. Sustainability messaging may be most effective for environmentally conscious consumers, while price-based incentives or subsidies may be necessary to encourage adoption among more cost-sensitive segments. Additionally, education on the safety and benefits of gene editing could increase acceptance, particularly among consumers who show skepticism toward emerging food technologies.

Future research should explore how factors such as trust in food innovations, regulatory perceptions, and ethical considerations shape consumer acceptance of food waste-reducing technologies. Expanding this analysis to additional food products and broader demographic groups could further refine strategies for increasing adoption and maximizing the impact of food waste reduction efforts. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that stated preference methods, including DCEs, are susceptible to hypothetical bias due to the absence of real economic consequences (Kemper et al. Reference Kemper, Popp and Nayga2020). While our research employed “cheap talk” (Figure 1) in an attempt to mitigate this bias, without a “real” baseline for comparison, we cannot know the true effectiveness of our bias mitigation efforts. Future work could benefit from a real choice experimental treatment to enhance behavioral validity. Additionally, while our sample is adequate for latent class modeling, its modest size suggests that findings should be interpreted with caution when generalizing to broader populations. By addressing these limitations and leveraging insights from consumer research, food producers, policy makers, and retailers can develop more effective strategies to promote sustainable food technologies, ultimately contributing to reduced food waste and improved environmental outcomes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/age.2025.10019

Data availability statement

The survey and choice experiment data used in this study were collected by the authors and will be made available as supplementary information digitally hosted by ARER. No proprietary or restricted-access data were used.

Funding statement

This research was supported by a Qualtrics Research Award, University of Arkansas Honors College, award no. 019439.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

AI contribution statement

AI tools, including ChatGPT, were used to assist with minor tasks such as formatting references and proofreading portions of the manuscript. All data analysis, interpretation, and substantive writing were conducted by the authors.