Introduction

The growing interdependence between finance and technology has become a key development in contemporary capitalism, necessitating a deeper engagement with tech actors in financial research within the social sciences (Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, Bassens and Van Meeteren2018; Gruin, Reference Gruin2019; Langley and Leyshon, Reference Langley and Leyshon2021). This issue is further complicated by the political sensitivity of finance, given its central role in resource allocation and its entanglement with modern nation-states (Lai, Reference Lai2023). Earlier studies have proposed the concept of the FinTech-State triangle to analyse how states mediate the relationships between financial and technological capital domestically, emphasising the importance of their interaction within the dynamics of contemporary capitalism (Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, van Meeteren and Bassens2020).

Recently, the intensifying geopolitical tensions on the world stage have called for a deeper exploration of these debates, as the interaction between finance, technology, and state actors unfolds not only within the territory of individual nation-state but also – if not more so – through the complex topologies of global financial (GFNs) and global digital technology networks (GDTNs) (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024; Zook and Grote, Reference Zook and Grote2025). The former emphasises the networks of financial and business services that connect leading financial centres and offshore jurisdictions (Coe et al., Reference Coe, Lai and Wójcik2014), whereas the latter captures the infrastructural power of tech firms that enable financial and production activities while extracting rents from their control over digital platforms (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024). In this context, specific tensions are seen to be emerging between territorial-state-centred geopolitics and the networked technology and financial actors. At the very forefront, how these tensions are intermediated and governed, warrants scholarly attention.

Building on these debates, we argue that the emerging field of cloud finance has become a frontier arena for analysing the geopolitics of the conjunction between GDTNs and GFNs. Here cloud finance refers to the increasing reliance of financial institutions on cloud computing services provided by technology companies to improve efficiency and drive platformisation transformation, which is seen as a prominent area to observe the growing intersection between finance and technology (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024). More importantly, since financial institutions such as banks are considered strategic actors for credit allocation and controllers of crucial financial data in various countries, the cross-border outsourcing involved in cloud finance naturally carries a high degree of geopolitical sensitivity. This characteristic makes cloud finance a crucial lens for examining the critical geopolitics emerging in the era of platform finance.

Currently, the technological spheres supporting cloud computing services for financial institutions are characterised by a bipolar structure, co-dominated by the United States (US) and China, while other regions, such as the European Union (EU), are becoming increasingly dependent on these external providers (Lehdonvirta, 2025). In response, major polities have started to implement regulatory measures aimed at driving favourable changes. Countries with technological hegemony, like the US, which have long been criticised for weaponizing global interdependencies to extend their geopolitical influence (Farrell and Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2023), appear to have further strengthened this approach with the growth of cloud finance. This situation has raised significant concerns regarding data security, financial stability, and cybersecurity in regions with external dependencies in cloud finance, leading to calls for regulatory reforms to address these challenges. While there is a flourishing literature on Big Tech (Birch and Cochrane, Reference Birch and Cochrane2021; Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, Adriaans, Klinge and Fernandez2021) and growing attention to issues of digital sovereignty in European political science and international relations (Falkner et al., Reference Falkner, Heidebrecht, Obendiek and Seidl2024), how geopolitical dynamics are embodied in the regulation of finance as it becomes tech is far more limited.

This article presents a relational comparison between the US, the EU, and China, focusing on their current practice in mobilising data, competition, financial, and cybersecurity regulation to navigate the increasingly conflict-riven space of infrastructural geopolitics of cloud finance (De Goede and Westermeier, Reference de Goede and Westermeier2022). It contributes conceptually by introducing a triad of cloud hegemony (US), subordination (EU), and insulation (China) to understand regulatory divergence. Empirically, it assembles dispersed regulatory and policy materials across jurisdictions. Analytically, it traces how regulation unfolds across the infrastructural, data, and financial layers of the cloud finance stack. Here, the stack refers to the layered architecture of digital infrastructures, platforms, and data flows that enable cloud-based financial services (Bratton, Reference Bratton2016). While acknowledging the relevance of private-sector actors such as global technology firms and financial institutions (James and Quaglia, Reference James and Quaglia2025), as well as the competitive as well as cooperative relations among them, the analysis focuses on state and regulatory perspectives. This reflects both the article’s conceptual orientation and the nature of the source materials.

Through this analysis, we show how – as finance becomes tech – it is drawn into wider regulatory stand-offs between leading states warring for technological supremacy. The current regulation of finance as tech hence also originates in novel regulatory fields that together shape how cloud finance is governed albeit in spatially and thematically utterly fragmented ways. At a time of mounting global tensions, and without international coordination or standardisation, this leaves the informal archipelagic territory (Sassen, Reference Sassen2013; van Meeteren and Bassens, Reference Van Meeteren and Bassens2016) dominated by leading American – and to a much lesser extent Chinese – cloud service providers (CSPs) subject to Realpolitik. The current layout of global infrastructure and market dominance of American CSPs reinforce US global cloud hegemony, while China has largely secured cloud insulation, protecting sovereignty domestically and cautiously expanding internationally. The fate of the EU, despite strategic attempts to regain technological sovereignty, has not materialised in the realm of cloud finance, producing enduring cloud subordination. Current geopolitical developments bear little indication of any betterment in this regard.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. The next section discusses the evolving interrelations between finance, technology, and geopolitics from a global view, aiming to develop a conceptual framework for understanding the geopolitics of contemporary cloud finance. The third section outlines the methodology used for the empirical investigation. Drawing on a comprehensive collection of public documents and reports, the fourth section critically evaluates the current regulatory practices of the US, the EU, and China in their financial cloud market, and explores how these practices align with their respective developmental contexts. The fifth section discusses the implications of these regulatory efforts on financial sovereignty. The final section concludes.

Finance, technology, and geopolitics

Embedded finance, finance embedded

The special issue problematises the observation that finance is becoming tech, capturing how financial institutions mobilise digital technology to embed services in the daily lives of clients (Lai and Langley, Reference Lai and Langley2024; Santos, Reference Santos2024; Tan, Reference Tan2021). However, what may feel seamless at the customer end requires access to a well-functioning stack of digital infrastructures (data centres, fibre optics, internet exchange points, etc.), digital platforms and technologies (cloud services, banking-as-a-service platforms, application programming interfaces), and personal (financial) data flows (Bratton, Reference Bratton2016). Cloud services can be considered crucial in vertically integrating the various layers of the stack for financial institutions since they offer the latter a flexible way to hyperscale business while providing the necessary tools to roll out platform models (Narayan, Reference Narayan2022; Hon and Millard, Reference Hon and Millard2018). While financial institutions used to host data on their own on-premises servers, most now rely on a hybrid system of private servers and public cloud (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024). Embedded finance (Langley, Reference Langley2006), it could be argued, is not only about embeddedness in the lives of people, but also about the embeddedness of financial services in a global network of digital infrastructures, technologies, and data flows.

Recent conceptual developments have aimed to capture the growing embeddedness of finance in GDTNs (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024) and of the economy more generally (Zook and Grote, Reference Zook and Grote2025). Witnessing the relative lack of attention to digital technology in current macro-frameworks such as GPNs and GFNs, GDTNs intend to analyse how technology firms take on intermediary roles within GFNs and GPNs. In a highly concentrated industry, that intermediary position grants tech firms the opportunity to extract rents from the ownership and control of the core infrastructure of platform capitalism (Van Dijck et al., Reference Van Dijck, Poell and De Waal2018). While much of the initial regulatory concern was about the growing inroads of large technology companies in financial service provision like payments, a more systemic issue is the emerging operational risk of finance’s infrastructural dependence on Big Tech’s cloud stack, as any downtime spurred by technical faults can immediately cripple business and, consequently, threaten financial stability. Such became evident in the Summer of 2024 when a Microsoft Azure outage disrupted services for Airlines, Media, Health, and several global banks like JP Morgan and UBS as well as infomediary Bloomberg (FT, 2024).

But operational resilience is but one dimension of a much wider set of potential implications of finance’s infrastructural dependence on a limited group of CSPs. Other key issues involve the lack of market competition producing vendor lock-in typical for digital markets, cybersecurity concerns pertaining to the location and protection of servers, and data protection and privacy in terms of who can access and reuse data (James and Quaglia, Reference James and Quaglia2024). While these concerns are serious enough when viewed through a ‘market’ lens, things get more complicated when appreciating the spatial tensions between Amoore’s (Reference Amoore2018) Cloud I and Cloud II geographies. These, respectively, denote the scattered yet interconnected physical geographies of cloud infrastructure and the seamless algorithmic-analytical realities it is producing. At its core sits the contradiction between a material logic of actual infrastructures and the topological relations as experienced when accessing and mobilising the cloud. When approached through a wider political economy lens, the more fundamental contradiction between the archipelagic geographies of the cloud and the Westphalian-territorial-state system moves into focus, with implications for how we read financial cloud sovereignty.

Sovereign states, sovereign finance

The tension between archipelagic cloud geographies and the Westphalian geography of its regulation and governance by states recalls such tensions in the regulation of global capital more generally. The advent of the global economy was very much seen as a matter of how previously national state containers were ‘leaking’ (Taylor, Reference Taylor1994). Meanwhile, the global economy, as Sassen (Reference Sassen2013) argues, produces new forms of territory that deborder the legal territoriality enshrined in sovereign state power. The global financial system could not exist without its backing by sovereign states. The ‘global’ financial system is anchored in a hierarchy of international money and credit ultimately backed by the Federal Reserve and the unconditional mutual support through swap lines with other leading central banks (Mehrling, Reference Mehrling2017). Bilateral and multilateral deals as well as international agreements like the General Agreement on Trade in Services of the World Trade Organization have produced a networked space allowing finance to operate across borders. Meanwhile, through its operations global finance, produces an archipelagic geography of interconnected islands through chains credit and debt (van Meeteren and Bassens, 2018).

Finance derives its sovereignty from a state which delegates sovereignty to corporations (Barkan, Reference Barkan2013). The relation between finance and the state is an intimate one since the monopoly on credit creation is effectively delegated to the former. Ironically, the state itself becomes dependent on credit extended by sovereign finance, with implications for how financial markets impose discipline on ‘sovereign’ states. Yet, the state – remember the 2007–2009 North Atlantic Crisis – has felt obliged to bail out too big to fail banks as otherwise strategic state functions like monetary and credit systems would grind to a halt. In this sense, finance has always been a special sector from a perspective of state sovereignty. Not controlling finance implies dependence and, potentially, subordination to foreign financial institutions that may feel the urge to pull out capital with dire effects (Alami et al., 2023). Vice versa, controlling foreign credit channels has historically been to the advantage of host states, even though the Eurozone crisis has illustrated that host states of disproportionately large banking sectors may get into trouble when the question of providing state backing arises (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, van Meeteren, Derudder and Witlox2013).

The growing intersections between finance and digital technology amid platform finance has, however, muddled the relationship between finance and the state, adding a third strategic sector to the equation. Earlier research deploying the notion of the FinTech-State triangle has illustrated how the state is arbitrating the domestic relation between finance and technology fractions of capital (Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, van Meeteren and Bassens2020). In Belgium, the state nudges finance to collaborate with an emergent FinTech class. In the EU more widely, in absence of home-grown tech champions, an agenda of technological sovereignty has emerged seeking to curtail American tech ‘gatekeepers’ (Bassens and Hendrikse, Reference Bassens and Hendrikse2022). In India, a technocultural nationalist discourse has supported strategies to decouple from American tech whilst mobilising domestic tech firms rather than financial institutions in authoritarian state building (Jain and Gabor, Reference Jain and Gabor2020). In China, large Techfins and information and communications technology (ICT) companies have a close relation with the state, as they and a host of FinTechs are mobilised in merging Finance and Tech in a wider shift towards algorithmic state control (Gruin, Reference Gruin2019). In the US, Big Tech success was built on decades of state investment (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2013) and is more than ever the realm of much state investment and support amid the race for Artificial Intelligence (AI). Further, the wide (financial) support by Silicon Valley for the inauguration of the second Trump administration may not bode well for future efforts to curtail oligopolistic Big Tech power (Birch and Cochrane, Reference Birch and Cochrane2021).

Financial sovereignty amid platform finance

While the matter of how strategic interests of states, finance and tech are being coupled domestically has received some scholarly attention, there has been less focus on how the growing dependence of finance on tech infrastructure is a source of geopolitical tension between states. Previously sovereign finance has now become reliant on this the tech fraction of capital, which moreover also increasingly enjoys state backing. But, while the geographies of finance are sticky and uneven anchored in a tightly integrated network of international financial and offshore centres (Haberly and Wójcik, Reference Haberly and Wójcik2022), the geographies of corporate control in the realm of Big Tech are concentred to a much bigger extent. The global cloud market is dominated by three American CSPs (Amazon, Microsoft and Google) all but for the Chinese market where Techfins like Alibaba, Tencent, and ICT firms like Huawei share a monopoly. This produces a bipolar cloud world, which grants crucial spoke states hosting both US and Chinese data centres substantial agency to not align singularly with one or the other bloc. In finance, Bassens et al. (Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024) further illustrated the dependence of banks around the globe on American GDTNs, while also illustrating the balkanisation of such networks. What hence emerges is an American technological sphere of influence covering most of the world including Europe and then a much more modest Chinese realm with only limited overlaps. The Chinese sphere of influence appears to be mostly concerned with fending off American inroads into domestic markets, even though initiatives like the Digital Silk Road also involve the geographical expansion of data centres, fibre-optics, and 5G infrastructure, but in a far more piecemeal manner than the Americans (Hussain et al., Reference Hussain, Hussain, Khan and Imran2024).

According to Schulze and Voelsen (Reference Schulze, Voelsen, Lippert and Perthes2020, 30), the nature of digital products and services as a combination of software and hardware is such that no single state or company has absolute control. In such a context, influence depends on centrality in GDTNs, granting actors and firms more or less power. We argue that the object of geopolitical contest between states is securing control over the cloud finance stack, including digital infrastructure, technology, and data. Amid platform finance, maintaining, securing, and expanding sovereign finance implies controlling the interface between financial institutions and CSPs. This boils down to three interdependent yet distinct layers of the stack, each with its own type of sovereignty and corresponding geopolitical ramifications.

First, infrastructural sovereignty captures the degree of state control over finance’s critical digital infrastructure. This includes not only physical components such as data centres, fibre optic cables, internet exchange points, and the energy systems required to operate them (Chow et al., Reference Chow, Lai, Liu and Seah2024), but also core financial infrastructures such as secure messaging networks, payment and settlement systems, and central counterparties (Genito, Reference Genito2019; De Goede, 2021; Nölke, Reference Nölke2024). For example, SWIFT, a key global financial messaging infrastructure, is still owned and run by banks themselves, yet has become embroiled in infrastructural geopolitics (De Goede and Westermeier, Reference de Goede and Westermeier2022) and has faced pressures to reinvent itself as a platform (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Dörry and Derudder2024). In reality, controlling the ‘chokepoints’ of global digital infrastructure enables the US to weaponize global financial data flows against adversaries and mobilise them to the benefit of allies (Farrel and Newman, 2019). The global outlay of cloud infrastructure is, as such, a crucial infrastructural layer for the global financial system.

Second, technological sovereignty refers to the degree of state control over the development and innovation of financial technology. As the literature on FinTech has illustrated (Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, van Meeteren and Bassens2020; Pažitka et al., 2024), many states as well as financial centres have adopted developmentalist approaches to grow and support ‘open banking’ ecosystems to foster the development of platforms, applications, and application programming interfaces that form the core of cloud finance, thereby intending to increase the centrality of the state in global networks of FinTech innovation and investment. Centrality in FinTech ecosystems also spills over into market centrality in the provision of Banking-as-a-service solutions in financial institutions (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024), implying that technological sovereignty is not only about strategic autonomy in terms of technology, but also opposition to market dependence on foreign enterprises.

Third, data sovereignty raises questions about the extent to which states can control where financial data are stored, who handles data, who has access and under what conditions, the degree to which principles of safety and privacy are guaranteed for citizens and key institutions, and equally, the circumstances under which financial data can be accessed when it is deemed in the interest of the state (e.g. for anti-money laundering and fraud prevention, cybersecurity, homeland security, financial sanctions). There are differences in how China, Europe, and the US regulate the cloud in general, and how these distinct digital empires vary in their extraterritorial reach (Bradford, Reference Bradford2023).

Contemporary geopolitics at the intersections of finance and technology hence revolves around complex and interrelated struggles for state control over digital infrastructure, technology and data, and we argue these tensions are particularly salient to scrutinise in the realm of cloud finance.

Methodology

Witnessing mounting geopolitical tensions across the cloud finance stack, the objective of the article is to understand the geopolitically informed developments in the regulation of Big Tech cloud usage in financial services. Taking a cue from Langley and Leyshon (Reference Langley and Leyshon2023), who study the FinTech regulation in the UK and China, we consider regulation an empirical entry-point into how states position themselves amid the evolving landscape of platform finance. We focus on regulation because it most clearly articulates questions of sovereignty, security, and competition, making it a crucial lens on the geopolitics of cloud finance. In this article, however, the empirical focus is shifted specifically to the cloud regulation, in order to capture the multilayered structure of the cloud finance stack and extend the focus more globally. Given the Chinese-American bipolar structure of contemporary technological spheres of influence (Lehdonvirta et al., Reference Lehdonvirta, Wú and Hawkins2025), our attention is drawn to regulatory developments in China and the US, but we extend the frame of analysis to the EU since, as a core financial market, this bloc has been prolific in advancing regulation in this regard.

To date, existing views on financial cloud regulation are, alas, fragmented. As James and Quaglia (Reference James and Quaglia2024) explain for the EU, Big Tech regulation is a multidimensional field ranging across regulatory domains of data protection, market competition, financial stability, and cybersecurity. These authors demonstrate that these regulatory fields have become entangled yet remain siloed in terms of discourse and practice. And while we see studies of digital regulation across core markets (Bradford, Reference Bradford2023), these lack a specific focus on finance. Meanwhile, informative studies on platform finance regulation (Langley and Leyshon, Reference Langley and Leyshon2023) tend to focus on one particular layer of the cloud finance stack (i.e. FinTech), while the crucial interdependence with infrastructure and data needs further attention. Finally, and importantly, the question of geopolitical strife within the cloud finance stack warrants a relational view of regulatory developments in these core markets since regulation responds to geopolitical manoeuvres elsewhere.

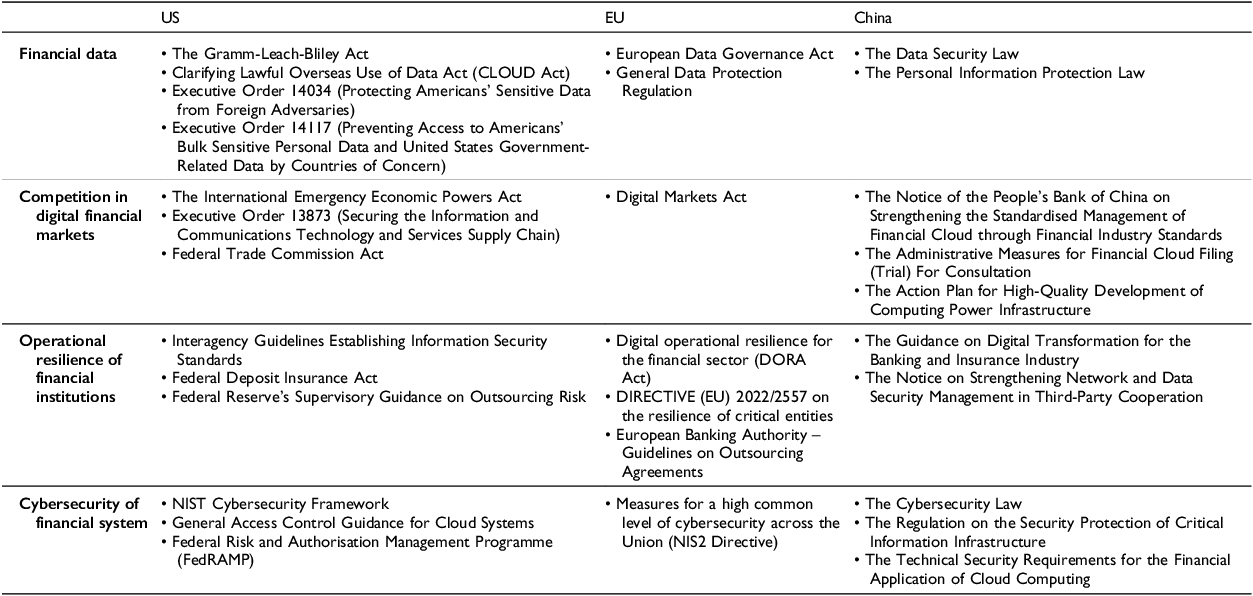

Our analysis focuses on regulatory developments across the cloud finance stack. In this rapidly moving field that matured over the past decade, much of the attention goes to recent legislation and regulation, yet we also include key pre-and post-crisis pieces where relevant. This results in a trail of salient regulation spanning the early 2000s to present. We collected official regulatory and legislative documents, directives, and industry standards pertaining to privacy and data protection, competition in digital markets, operational resilience, and cybersecurity for each bloc (see Table 1). Our focus on cross-border flows of personal financial data reflects their direct connection to state sovereignty and privacy concerns, with the corresponding regulatory frameworks shaping how transnational corporate actors share data.

Table 1. Key regulatory and legislative documents in cloud finance in the US, the EU, and China. Source: Authors’ compilation.

The above documents were closely read in terms of how regulation addressed the (supra)state’s positionality in and control over the different layers of the cloud finance stack. Our analysis concentrated on identifying and examining instances in regulatory documents that reference the dynamics underlying control over infrastructure, cloud and fintech markets, and data flows, access, encryption, and security, and their implications for financial institutions. We also triangulated these documents with media articles, official communications, coverage of court cases/rulings, parliamentary/congressional discussions, and reports on bilateral and multilateral diplomacy, to capture the broader relational context of regulatory developments. While primarily relying on these sources, we remained attentive to the strategic deployment of concepts such as sovereignty, dependency, and hegemony in regulatory discourse, treating them not as neutral descriptors but as part of the political work enacted through regulation. The methodology allowed to understand the vertical connections across the different layers of the cloud finance stack per bloc as well as the domestic versus extraterritorial interests for each layer.

Regulating cloud finance in the age of infrastructural geopolitics

Before entering into a substantive analysis of the regulatory practices governing financial cloud services in the US, the EU, and China, it is essential to first outline the landscape of their respective financial cloud markets. The US currently leads the global financial cloud industry, with three major US-based CSPs holding dominant market shares both domestically and internationally (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024). Consequently, these same providers exert significant control over the EU’s financial cloud market, raising concerns about the region’s heavy reliance on a highly concentrated group of external CSPs. By contrast, China’s cloud computing sector has developed through a mix of private technology companies and state-owned telecommunications enterprises, creating a competitive market that sufficiently meets domestic financial institutions’ needs with minimal reliance on foreign cloud services.

Against this backdrop, regulatory approaches to financial cloud services in these regions emerge from distinct starting points and reflect differing geopolitical priorities. The remainder of this section provides a comparative analysis of regulatory practices in the US, the EU, and China across four key dimensions: data protection, market competition, financial sector regulation, and cybersecurity.

Data protection

In the US, the federal government adopts a relatively flexible regulatory approach to the protection of financial data, advocating for the free flow of data between institutions and across borders based on agreements. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, enacted in 1999, explicitly outlines the responsibility of financial institutions to safeguard customer data. However, it does not prohibit these institutions from sharing information with third parties, such as CSPs, as long as they provide adequate disclosure to users and obtain their consent. In the era of platform finance, this legislative philosophy has persisted, further facilitating the shift of large volumes of financial data from traditional financial institutions to CSPs. The financial data managed by CSPs is also permitted to flow beyond US borders. Under the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act passed in 2018, foreign governments are, in principle, allowed to request access to US financial data held by American CSPs for judicial purposes, provided they have established bilateral agreements with the US.

While these bilateral agreements appear to grant reciprocal data access rights between the US and its allies, in practice, such rights are typically granted only to countries that are asymmetrically dependent on US CSPs. While the core objective of the CLOUD Act is to enable US judicial authorities to easily access foreign data stored by American CSPs, the reciprocal access granted to foreign governments through bilateral agreements functions more as a compensatory arrangement. Due to this asymmetrical dependency, rather than mutual reliance, the US government maintains de facto control over the bidirectional cross-border flow of data. Countries like China, which do not rely on US CSPs, are labelled as ‘countries of concern’ or ‘foreign adversaries’, prohibiting them from accessing US financial data. The US Executive Order 14034 of ‘Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data From Foreign Adversaries’ explicitly restricts the transfer of sensitive data, including financial data, to ‘foreign adversaries’ such as China. Similarly, Executive Order 14117 of ‘Preventing Access to Americans’ Bulk Sensitive Personal Data and United States Government-Related Data by Countries of Concern’ mandates the prohibition or limitation of access to sensitive US personal data and government-related data by entities from a flexible list of ‘countries of concern’.

In contrast to the US approach, which emphasises data flow within a select geopolitical framework, the EU enforces a more structured and restrictive regulatory regime under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Enacted in 2016, the GDPR sets out detailed requirements for various institutions regarding the collection, storage, and management of personal data within the EU. While GDPR allows financial data transfers to non-EU countries, such transfers are contingent upon the recipient country ensuring an adequate level of data protection. The EU evaluates adequacy based on several criteria, including the rule of law, respect for human rights, and the presence of independent supervisory authorities. Based on these assessments, the EU has granted adequacy status to several countries and regions – including Andorra, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and, more recently, the US – allowing financial data to be transferred securely.

For jurisdictions beyond this limited geographical scope, financial data transfers must rely on bilateral agreements or mechanisms such as standard contractual clauses, both of which must comply with GDPR requirements. Companies that violate GDPR regulations by illegally acquiring or processing EU data face substantial financial penalties, with fines reaching up to 2–4% of their global annual turnover. This stringent approach has positioned the GDPR as a global benchmark for data privacy protection, influencing regulatory practices worldwide. A notable example of the GDPR’s impact is the Schrems II ruling, in which the Court of Justice of the EU invalidated the EU-US Privacy Shield, citing its non-compliance with GDPR and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. This decision prompted renewed negotiations between the EU and the US, ultimately leading to the 2023 EU-US Data Privacy Framework, which imposes stricter limitations on US intelligence agencies’ access to EU citizens’ data and establishes a redress mechanism enabling EU citizens to file complaints and request data deletion. Nevertheless, the Schrems II case underscores the persistent challenges in GDPR implementation. Despite mitigation measures such as standard contractual clauses and encryption, the effectiveness of these safeguards remains uncertain. Factors such as fluctuating EU-US relations and the EU’s relatively limited technological capabilities compared to the US continue to complicate data protection efforts, often framed in regulatory discourse as challenges to its ‘sovereignty’.

China, by contrast, adopts a highly restrictive approach to financial data regulation, centred on stringent data localisation requirements. Nearly all cross-border financial data transfers are subject to rigorous state oversight through an administrative approval system. Two key laws, which are the Data Security Law (数据安全法) and the Personal Information Protection Law (个人信息保护法), provide the legal foundation for this approach. The Data Security Law explicitly prohibits any organisation or individual within China from providing domestically stored data to foreign judicial or law enforcement authorities without prior approval from Chinese regulators. Meanwhile, the Personal Information Protection Law imposes strict controls on the cross-border transfer of personal data, requiring personal information processors to obtain certification or establish contractual agreements with overseas recipients in accordance with standard contractual clauses set by Chinese regulatory authorities.

In practice, financial institutions and their partner CSPs must undergo a national security assessment before transferring financial data abroad if they handle large-scale personal or sensitive financial information. Given these requirements, it is challenging for major financial institutions or CSPs operating in China to transfer financial data overseas without state approval. This regulatory approach reflects China’s broader strategy of data sovereignty, which aims to safeguard national security while reducing dependence on foreign CSPs. Here, sovereignty is not only a policy goal but also a discursive instrument that frames the legitimacy of regulatory control.

Market competition

In the US, regulatory influence in financial cloud markets primarily focuses on limiting the market presence of CSPs from geopolitical competitors. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act grants the US President broad authority to impose economic sanctions on foreign entities deemed threats to national security. This authority has been exercised through Executive Order 13873, ‘Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain’, signed by President Trump in 2019, which empowers the US Department of Commerce to restrict foreign CSPs operating as ICT providers if they are considered risks to US national security, critical infrastructure, or the digital economy. Under these provisions, Huawei, a leading Chinese CSP, was placed on the Entity List, effectively prohibiting US companies from engaging in commercial transactions with it without government approval. Other Chinese CSPs have similarly faced the threat of sanctions, further reinforcing an environment that makes it nearly impossible for them to compete in the US market (Shepardson, Reference Shepardson2023).

While the US has aggressively excluded foreign CSPs, its regulatory stance on domestic CSP monopolies has been more restrained. Given the de facto monopolistic position of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, whose services dominate the CSP market, regulatory concerns have emerged, particularly regarding the challenges financial institutions face in negotiating contracts with these dominant providers. For instance, the US Treasury has acknowledged that ‘even the largest financial institutions reported difficulties in negotiating contracts’ (US Department of the Treasury, 2023, p.59). However, effective regulatory intervention remains largely absent. In 2024, US District Judge Amit Mehta ruled against Google for monopolistic practices. Yet, antitrust enforcement in the US has historically faced significant obstacles. The lack of stringent enforcement has perpetuated vendor lock-in, further entrenching the dominance of a few CSPs despite ongoing regulatory scrutiny.

Unlike the US, where restrictions are primarily imposed on foreign competitors, the EU has taken a more proactive approach to regulating CSP market dominance through competition law. The Digital Markets Act identifies a small number of dominant CSPs as ‘gatekeepers’ and closely monitors their activities for anti-competitive behaviour. This ex-ante regulatory framework aims to prevent CSPs from leveraging their market position to suppress competition. However, the effectiveness of the Digital Markets Act in dismantling the financial cloud oligopoly remains limited. Despite its preventive measures, EU-based financial institutions still have few viable alternatives to US hyperscale CSPs. In this context, the most they can do is adopt a multi-cloud strategy – engaging multiple public cloud providers – to reduce dependency and mitigate the risks of vendor lock-in.

In contrast to the US and the EU, the regulatory approach of China focuses on establishing high entry barriers for competition in its domestic financial cloud market, using strict compliance requirements to regulate CSP participation. The 2020 Notice on Strengthening the Standardised Management of Financial Cloud through Financial Industry Standards (中国人民银行关于发布金融行业标准强化金融云规范管理的通知) issued by the People’s Bank of China explicitly outlines the market entry thresholds for CSPs. Under this framework, CSPs must file for approval with Chinese regulatory authorities, effectively excluding any CSPs that fail to meet these requirements from market competition.

Industry analysts note that the filing process imposes demanding financial and operational requirements on CSPs (e.g. Zhang, Reference Zhang2021). Applicants must not only demonstrate that cloud computing is their core business, but also meet specific financial thresholds. Additionally, CSPs are required to submit a comprehensive set of regulatory documents, including but not limited to operating licenses, cybersecurity review certificates, cybersecurity grade certificates, and financial industry data centre inspection reports. These complex and time-consuming compliance requirements prolong the entry process and create significant barriers for CSPs in China’s financial cloud market. For foreign CSPs, these regulatory hurdles present an even greater challenge, making market entry exceptionally difficult.

Beyond enforcing entry restrictions, Chinese regulators have also attempted to coordinate competition among domestic CSPs. A key example of this state-led approach is the 2023 Action Plan for High-Quality Development of Computing Power Infrastructure (算力基础设施高质量发展行动计划), which promotes interconnectivity among CSPs to enhance the efficiency of cloud services. The plan calls for ‘promoting the integration of computing power resources via cloud services’ and ‘fully leveraging the flexible scheduling advantages of cloud computing’ (p. 5). This reflects the Chinese state’s role in shaping competition within the financial cloud sector for advancing broader national industry development objectives.

Financial sector regulation

In the US, financial sector regulation reflects an activity-based approach, whereby the regulatory focus lies not on the institutional form of financial actors, but on the specific activities they perform. In the context of cloud-based financial services, this approach is primarily implemented through guidance documents that clarify how existing regulatory requirements apply to cloud-related activities. Rather than imposing rigid compliance mandates, US regulatory agencies issue interpretive guidelines that explain how broader financial regulations apply to cloud infrastructure. For example, the Interagency Guidelines Establishing Information Security Standards set out due diligence expectations for financial institutions to ensure they can effectively monitor risks and maintain business continuity in the event of disruptions. When subcontracting services to technology providers such as CSPs, financial institutions are expected to establish contractual arrangements that clearly delineate responsibilities for managing potential disruptions, including cybersecurity threats and physical damage. This regulatory framework places the onus on firms engaged in financial activities to conduct internal risk assessments, adhere to industry standards, and maintain appropriate oversight mechanisms to ensure that their use of cloud infrastructure does not introduce undue risk to the financial system.

Under this activity-based regulatory framework, financial institutions enjoy significant autonomy in risk management. Nevertheless, federal authorities retain the power to intervene when failures occur. Under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, the US government can conduct audits, oversee operations, and impose regulatory measures through independent federal agencies. However, these regulatory interventions are selective and punitive, typically occurring after risks materialise rather than as a proactive measure. As a result, US financial institutions are granted considerable operational flexibility in structuring their risk assessment and resilience strategies. This shifts the burden of responsibility onto institutions themselves, reinforcing a market-driven approach to risk management.

A similar regulatory philosophy informs financial sector oversight in the EU, where responsibility for assessing risks associated with financial cloud service outsourcing arrangements also falls primarily on financial institutions. However, unlike the US, the EU has increasingly combined activity-based regulation with an entity-based logic. As James and Quaglia (Reference James and Quaglia2025) observe, this shift marks a departure from the EU’s earlier focus on regulating specific financial activities towards imposing structural obligations on the regulated entities themselves. In the financial domain, the key legislative framework is the 2022 Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which governs the outsourcing arrangements of financial institutions to ICT firms. Similar to the US approach, DORA requires financial institutions to report cyber threats and vulnerabilities, conduct resilience testing, and manage ICT third-party risks. Unlike the US approach, however, DORA establishes a more structured oversight mechanism by mandating reporting obligations and resilience testing, while also allowing regulatory intervention when necessary. As stated in its official rationale, DORA aims to ‘[strike] a fair balance between the imperative of preserving contractual freedom and that of guaranteeing financial stability’, as ‘it is not considered appropriate to set out rules on strict caps and limits to ICT third-party exposures’ (p. 15). In practice, this gives regulatory authorities the power to suspend the use of Big Tech providers if major issues arise.

China, by contrast, adopts a more explicitly entity-based regulatory approach to financial institutions. In formal terms, Chinese regulators also issue guidance documents that identify potential risks and set compliance expectations in detail. For example, the 2022 Guidance on Digital Transformation for the Banking and Insurance Industry (中国银保监会办公厅关于银行业保险业数字化转型的指导意见) requires financial institutions to ‘adhere to the principle of independent control over critical technologies, develop independent R&D capabilities for key platforms, components, and information infrastructure that significantly impact business operations, reduce external dependencies, and avoid single points of reliance’ (Article 21). Similarly, the 2023 Notice on Strengthening Network and Data Security Management in Third-Party Cooperation (关于加强第三方合作中网络和数据安全管理的通知) mandates that banks and insurance institutions strengthen the oversight of outsourced services, ensuring that external data sharing follows the principles of ‘business necessity’ and ‘minimum access’ while prioritising local deployment of systems and data.

While China’s regulatory instruments may resemble those of the US and EU in form, their content and authority reflect a distinct institutional logic. A key difference lies in the structure of China’s financial system. Unlike in the US and the EU, where financial institutions primarily operate as market-driven entities, China’s largest financial institutions, such as Bank of China and China Construction Bank, are state-owned and led by senior bureaucrats within the party-state system. Their performance is thus evaluated not only by commercial outcomes but also by alignment with national policy priorities. This structural difference suggests that although China also favours guiding documents over rigid compliance frameworks, these guidelines may carry greater implicit authority over financial institutions.

Cybersecurity

The US primarily enhances the cybersecurity standards of CSPs serving financial institutions by issuing national guidelines for the domestic market. Key advisory standards include the General Access Control Guidance for Cloud Systems (NIST SP 800-210) and the Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organisations (NIST SP 800-53), both published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2020. These guidelines assist CSPs in designing more robust systems for data protection and attack resilience to enhance security within cloud environments. Compared with formal legislation, such advisory guidelines can be updated more rapidly in response to emerging cybersecurity challenges. However, this approach also places substantial reliance on self-regulation by major technology firms, since compliance is largely left to the discretion of CSPs themselves.

Unlike the US, the EU has established a regulatory framework that embeds cybersecurity requirements into binding legal obligations. The NIS2 Directive and related regulations extend the regulatory scope of financial cloud services to include CSPs, data centre service providers, and other critical infrastructure operators. These entities must implement effective cybersecurity risk management measures to ensure the availability, integrity, and confidentiality of their services. In the event of a major security incident,Footnote 1 CSPs are required to report the breach immediately and take corrective action. Moreover, the NIS2 Directive introduces a cross-border regulatory framework, stipulating that CSPs and other key technology providers should be regulated by the member state in which they have their main establishment. For CSPs operating across multiple jurisdictions, regulatory authorities are expected to coordinate oversight efforts to ensure compliance with EU cybersecurity requirements. To further reinforce security standards, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity is developing a cybersecurity certification scheme for cloud services, which will set minimum security requirements for CSPs operating within the EU. However, despite these efforts, concerns remain regarding the resilience of the EU’s financial system against external technological penetration. In the past foreign agencies, such as the US’s National Security Agency (NSA), have been found to access financial data whilst disregarding national laws (Farrell and Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2023), suggesting that the presence of US CSPs within the GDPR adequacy framework may, in fact, create a significant cybersecurity loophole.

China’s approach to strengthening financial sector cybersecurity differs from both the US and EU models by placing a stronger emphasis on regulatory intervention in key CSP operations. The 2016 Cybersecurity Law introduced the concept of ‘critical information infrastructure which refers to infrastructure whose compromise – whether through damage, functional disruption, or data breaches – could severely harm national security, economic stability, or public interests, particularly in key sectors such as finance. Under this legal framework, CSPs must comply with a comprehensive set of security requirements, including data classification and grading, risk assessments, data localisation, cross-border transfer scrutiny, and the implementation of technical security measures. In addition, CSPs designated as critical infrastructure providers are subject to regular or ad hoc regulatory inspections to ensure strict compliance with cybersecurity mandates. As a result, CSPs serving major financial institutions, such as large state-owned banks, operate under close supervision and direct oversight by national regulatory agencies.

Weighing sovereignty across the cloud finance stack

US: Near hegemonic sovereignty across the cloud stack

The US leverages its powerful infrastructural sovereignty and technological sovereignty to support its data sovereignty and achieve cloud hegemony on a global scale. While the strength of the US stems from its robust technological innovation capabilities, the US is increasingly focused on undermining the technological capabilities of emerging competitors like China – and the threat posed by the international expansion of these capabilities – to consolidate its infrastructural and technological sovereignty. At the same time, the US is also using direct and decisive regulatory measures to prevent its de facto data sovereignty from being infringed upon by geopolitical competitors. The implication is that, both domestic and internationally, US financial institutions have little choice but to depend on a domestic oligopoly of CSPs, reinforcing Wall Street’s dependence on Silicon Valley hyperscalers and the welding together of US-led GFNs and GDTNs. US banks have become less sovereign due to their reliance on Big Tech, yet Big Tech does remain crucially dependent on Wall Street as swaying financial markets remains key to winning the global race for cloud supremacy, especially amid rapid AI developments. What is more, an external shock, such as the one caused by DeepSeek, may upset share prices of American Tech firms, even though in this particular case American CSPs quickly recovered (Waters, Reference Waters2025).

In terms of defending and expanding its technological sphere of influence, US regulation enables the free flow of data across a list of trusted nations, yet the underpinning agreements are de facto skewed towards US interests, allowing it to access financial data where needed. US Big Tech firms have largely embraced their role in extending American technological influence, with executives regularly testifying to Congress about the strategic importance of maintaining US leadership against Chinese competitors (Zuckerberg Reference Zuckerberg2020; Smith Reference Smith2025). The current worldwide rollout of privately owned cloud infrastructure by Big Tech can be mobilized as data sinks in the AI development race or be weaponised as happened previously with international payment infrastructure (Farrell and Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2023). The CLOUD Act supports the ever-deeper reach of the US state into the lives of non-US citizens (Debouzy, 2021), and there is little reason to think this would not also apply to cloud finance platforms unless bilateral agreements stipulate otherwise (and are respected). Domestically, the fact that unelected Tech moguls like Musk, who wields advanced AI tools, are leading unofficial government departments with full access to personal (financial) data suggests that effectively there are limited barriers to the extent to which Tech can access personal data (Miller, Reference Miller2025), which in turn can be accessed by the US state if needed. The degree to which cloud dependence for US financial institutions can also be weaponised against citizens is an open question, but if so, the road towards state surveillance lies wide open.

EU: Deepening cloud subordination

In the EU evidence on cloud banking regulation suggest that ‘cloud subordination’ may better capture the current EU condition. With the Digital Markets Act still to prove effective in breaking up the Big Tech monopolies, the EU appears to have no other choice than to push the responsibility to the level of banks via digital operational resilience rules. In this context, banks are not limiting dependence on US hyperscalers yet simply make use of multiple CSPs. This may guarantee operational resilience, yet by no means represents an increase in the bloc’s financial cloud stack sovereignty. Almost completely dependent on Big Tech CSPs, the EU has made significant regulatory efforts to enhance its data sovereignty, which functions less as an achieved condition than as a normative ambition articulated in policy discourse (Aka Reference Aka2025; Teevan and Pouyé Reference Teevan and Pouyé2024). However, owing to its lack of infrastructural sovereignty and technological sovereignty, it faces asymmetric dependence on the US. This dependency makes the maintenance of its data sovereignty fragile. The Schrems II court case painfully illustrated the limits to GDPR enforcement vis-à-vis the US. Although the US-EU Data Protection Framework nominally addresses these limits, its implementation depends on the goodwill of both powers. The uncertainty induced by the transfer of power following the Biden administration raises questions about whether the agreement will be respected. While encryption requirements are in place following cybersecurity regulation, the Data Protection Authority of North-Rhine Westphalia judged that encryption does not suffice in the face of cryptanalytic and quantum computing efforts of the NSA.Footnote 2

The 2024 Draghi report (Draghi, Reference Draghi2024, p. 34) offers a candid summary of the EU’s predicament: ‘It is too late for the EU to try and develop systematic challengers to the major US cloud providers: the investment needs involved are too large and would divert resources away from sectors and companies where the EU’s innovative prospects are better’. The Draghi report (Ibid.) recognises the need to guarantee ‘sovereign cloud’ solutions: ‘To achieve this goal, the report recommends adopting EU-wide data security policies for collaboration between EU and non-EU cloud providers, allowing access to US hyperscalers’ latest cloud technologies while preserving encryption, security, and ring-fenced services for trusted EU providers’. The problem with Draghi’s middle ground vision, however, is that it relies heavily on the EU’s leverage in controlling access to the EU market to enforce adoption of its regulations. Furthermore, Big Tech firms have strategically positioned themselves as partners in European digital sovereignty efforts while simultaneously framing sovereignty concerns as protectionist measures that ultimately harm European consumers and businesses. In this standoff, cloud subordination weakens the EU’s position significantly and draws cloud finance regulation into wider emerging diplomatic tensions between the US and the EU.

The case of AI regulation is telling in this regard. Although the EU adopted the AI Act in August 2024 to regulate high-risk cases, including credit scoring, it has been under significant pressure since the change of power in the White House. At the AI Action Summit in Paris in February 2025, the US and the UK refused to sign a declaration for safer and more inclusive AI despite it being endorsed by 60 states, including China and India. Although US Vice-President Vance indicated willingness to collaborate, ultimately, he maintained the Trump administration’s position that ‘the most powerful AI systems are built in the US, with American-designed and manufactured chips’ (Abboud and Heikkilä, Reference Abboud and Heikkilä2025). The lack of US commitment fundamentally undercuts the EU’s credibility in effectively regulating the Big Tech–dominated field. More disturbingly, the synchronisation with other high-level discussions about military spending and the Russian-Ukraine war suggests that Big Tech regulation is part of a wider quid pro quo position of the US towards the EU.

With the US having dropped the idealist veil covering its real politics, the EU finds itself increasingly geopolitically isolated. In such a context, the dependence on US CSPs across the financial cloud stack may prove another unilateral liability. The situation may have proven different in pre-Brexit times when London was still an EU-enclosed space of dependence in the technological layer, with London trumping New York as the most dynamic FinTech centre (Bassens et al., Reference Bassens, Pažitka and Hendrikse2024). Moreover, the operational importance of London as a space for American financial institutions could have given the EU significant leverage in US negotiations. Post-Brexit, the loss of London and the modest growth of Paris and Frankfurt in its wake have left the EU empty-handed in terms of leverage in GFNs. The desire to undo cloud subordination gave rise to a European Cloud Certification scheme, but it was stifled by diverging member state preferences and institutional conflicts (Rone, Reference Rone2024). Meanwhile, sovereign cloud initiatives such as the French-German Gaia-X which could also be a safe haven for European financial institutions, had issues getting off the ground and, more interestingly, the alliance ended up including American Big Techs as well as Chinese Techfins (Goujard and Cerulus, Reference Goujard and Cerulus2021).

China: Cloud insulation

In China, the Chinese state appears to have invested significant regulatory attention at every layer of the financial sovereignty stack, ensuring that its infrastructural, technological, and data sovereignties mutually reinforce each other. Specifically, this means that China closely supervises the digital infrastructure that domestic financial institutions depend on, making it a priority area for regulatory oversight. By exercising full regulatory control over its territory, China has strengthened ties between the state, domestic financial institutions, and local CSPs, making it challenging for foreign players to participate in the game. As a result, China has been able to forcefully defend its financial sovereignty, but it has done so by effectively choosing the path of cloud insulation. In a broader sense, this reflects the consistent realist stance taken by China in its geopolitical strategies. For example, from this standpoint, the Chinese state has long pursued a national plan to establish an indigenous innovation strategy (Sun and Cao, Reference Sun and Cao2021). This emphasis on self-reliance has helped shape China’s financial cloud market into a large, unified domestic market, creating the conditions for a nationally integrated, centrally directed regulatory framework that is free from the external pressures associated with interjurisdictional coordination.

However, if we consider the flip side, China’s forceful defence of financial sovereignty may precisely stem from its disadvantaged position in global competition with the US. In this regard, the research by Lehdonvirta et al. (Reference Lehdonvirta, Wú and Hawkins2025) sheds light on the recent dynamics of the competition between the two countries in the global financial cloud market. Beyond occupying their respective domestic markets and succeeding in specific Middle Eastern markets, China’s CSPs seem to have a competitive edge in Southeast Asia and Latin America, while the US dominates the financial cloud markets in North America, Europe, and Oceania, essentially all high-income countries. This core-periphery structure in the global economy, with a clear division of primary financial CSPs, may point to deeper geopolitical realities. In the current cloud finance sector, China seems to be adopting a defensive stance resisting US hegemonic sovereignty, rather than standing as an equal competitor in the rivalry between major powers. Despite the ambitious Digital Silk Road initiatives raised by China, scholars remain sceptical as to whether it truly has a coordinated national effort to advance this geopolitical agenda in practice (Cheng and Zeng, Reference Cheng and Zeng2024; Oreglia and Zheng, Reference Oreglia and Zheng2025). To make matters worse, some even caution that, considering the controversies surrounding digital authoritarianism (Gruin, Reference Gruin2019), geopolitical discourse embodied in the Digital Silk Road may undermine the international expansion opportunities for Chinese companies (Cheng and Zeng, Reference Cheng and Zeng2024).

Considering President Trump’s second term and the US’s seemingly growing tendency towards geoeconomic and geopolitical decoupling (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Fang and Guo2024), along with the increasing competitive pressure in the domestic market that is pushing China’s CSPs to expand internationally (Olcott et al., Reference Olcott, Liu and McMorrow2023), their future global expansion remains something to keep a close eye on. In a recent high-level private business symposium, the leaders of China’s CSP market leaders – Alibaba, Huawei, and Tencent – were reassured by President Xi, who encouraged them to ‘show their talent’ in the current era (Davidson, Reference Davidson2025). The CEO of DeepSeek, who had previously garnered significant attention as a representative of the fast-growing Chinese AI industry, was also invited and attended this symposium. Commentators interpreted this as a statement by the Chinese state to boost the morale of the private sector, especially technological national champions, in the context of the deepening US-China strategic competition, to align them more closely with the national agenda (Chen and Yang, Reference Chen and Yang2025). This stands in contrast to the previous, harsher regulatory crackdown on tech companies like Alibaba, possibly signalling a closer partnership between China’s CSPs and the state in the near future, which could bring new dynamics to the global financial cloud competition.

Conclusion

This article has studied how three leading macro-blocs – the US, the EU, and China – are mobilising data, competition, financial, and cybersecurity regulation to navigate the increasingly conflict-riven terrain of infrastructural geopolitics (De Goede and Westermeier, Reference de Goede and Westermeier2022) in cloud finance. While the literature on digital sovereignty is flourishing in political sciences and international relations (Falkner et al., Reference Falkner, Heidebrecht, Obendiek and Seidl2024), the focus on the geopolitics of finance as it becomes tech has, to date, received comparatively little attention within the interdisciplinary field interested in the intersections of finance and society. Alas, growing geopolitical tensions on the world stage are now drawing finance into these wider discussions about various forms of sovereignty, which we approached across the different layers of the cloud finance stack: infrastructural, technological, and data sovereignty.

First, our analysis of regulatory developments in the three blocs indicates that there is currently no such thing as an integrated framework of cloud finance in any of these regions. What constitutes cloud finance regulation is in fact a stitched-together set of regulations that do not seem to interact much. This may be because of the tightly interwoven nature of tech and finance under platform capitalism, while in practice regulation is typically organised along sectoral lines. This is most forcefully the case in the US; it also holds true in the EU (cf. James and Quaglia, Reference James and Quaglia2024); and even in China, where regulation appears to be more consistent, an integrated framework is non-existent. In all regions, this situation creates interesting contradictions between regulation on operational resilience and cybersecurity and regulations that work on competition and market structure. In general, financial institutions are held accountable for the former, but without any effective framework or will to break Big Tech or Techfin monopolies, such demands remain fragmented and have only limited structural impact. Financial sovereignty, under these conditions, is hard to maintain, especially in the EU where cloud dependence has introduced geopolitical liabilities. In the US and China, financial sovereignty is more of a domestic affair, where the state can mediate between the interests of tech and finance capital (Hendrikse et al., Reference Hendrikse, van Meeteren and Bassens2020). A key implication is that striving for sovereignty in the top layers of the cloud finance stack is an impossible endeavour if the infrastructural and technological layer is beyond control.

Second, despite the fragmented nature of financial cloud stack regulation, even these fragments are vehicles for geopolitical manoeuvring within GDTNs and the commensurate state-related technological spheres of influence. Here we found that in the US, the state’s regulatory powers are mobilised to defend domestic cloud finance oligopolies, while data regulation allows Big Tech cloud infrastructures to be weaponise abroad, cementing American hegemony across the financial cloud stack in large parts of the world. This includes the EU, which, after the loss of London post-Brexit and with wars at its borders, appears forced to accept financial cloud subordination to maintain amicable transatlantic relations. Financial cloud sovereignty, despite all the rhetoric, is thus an ever more distant dream. China has managed to mobilise ‘red tape’ in terms of operational resilience and strict data localisation laws to effectively protect domestic cloud sovereignty across the stack. However, results from expanding its cloud sphere of influence abroad, have been more limited, with both US and EU regulation blocking data transfers to China and effectively denying access to domestic cloud finance markets. Here the expansion has mostly been linked to the Digital Silk Road initiative, yet realities fall short of strategic rhetoric. For subordinated states – that is, nearly all states but the US and China – the politics of non-alignment or multiple alignment in the financial cloud may emerge as a salient strategy (Lehdonvirta et al., Reference Lehdonvirta, Wú and Hawkins2025).

Third, the bipolar segmentation of GDTNS sketched above illustrates how the cloud as an archipelagic space made up of interconnected data centres (van Meeteren and Bassens, Reference Van Meeteren and Bassens2016) forms what Sassen (Reference Sassen2013) would describe as a connected yet spatially disjointed territory. Rather than seeing a Brussels effect (Bradford, Reference Bradford2021), with EU rules and values being exported, the EU is de facto a subordinated vassal in US cloud territory despite its cloud finance rules. That does not exclude the export of EU cloud finance ‘values’ to non-core areas of the global economy, but in effect, the cloud stack remains mostly controlled from Silicon Valley with US state backing. While the global financial system depends just as much on an archipelagic territory anchored in bilateral and multilateral agreements, that system’s governance – however fragmented, flawed and incomplete – at least has international standard-setting bodies, macro-prudential regulatory bodies, and close ties with central banks to coordinate between states. To date, such international coordination is very limited in the realm of cloud finance, apart from the recurrent warnings issued by organisations like Bank for International Settlements (Carstens et al., 2023) and the Financial Stability Board (2019) about the systemic financial risk posed by too-big-to-fail Big Tech. Whether the financial stability argument is powerful enough for Big Finance to convince states to rein in Big Tech and regain its unchallenged sovereign status remains to be seen.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was funded by the Research Foundation Flanders, Grant Number G078824N. Earlier versions were presented at the 2nd FinGeo Global Conference at National University of Singapore and the 7th Global Conference on Economic Geography at Clark University. We thank participants for their questions and comments. We are also grateful to Editor Carola Westermeier, Editor-in-Chief Amin Samman, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. All claims and omissions remain our responsibility.