1 Introduction

The Bronze Age Aegean provides us with nearly 2,000 years of textile history. Evidence of this history has long been found in various forms of material culture, since the early days of Aegean prehistoric research (e.g., Evans Reference Evans1902, 55–58, Fig. 28, 102, Fig. 59; Paribeni Reference Paribeni1908). Through the iconography of clothed human figures in the art of the second millennium BCE, a focus on garments and costume soon became possible. Archaeology of the early twentieth century was concerned with the distinction of Bronze Age ‘ethnic’ identities, and costume seemed an obvious basis for such categorizations (Myres Reference Myres1950; Zora Reference Zora1956). Since this early scholarship paid less attention to issues of production and craftsmanship, the study of cloth and textile craft fell behind the early focus on dress.Footnote 1

From the mid twentieth century onwards, archaeology shifted towards a new paradigm, integrating the study of gender, economy, and technology. This had an impact on the study of Aegean Bronze Age textiles. Craftsmanship, gender and society became important research parameters. In Aegean prehistory, the study of dress iconography began to integrate a technological perspective, discussing the materials and techniques likely employed to manufacture the garments depicted in Aegean Bronze Age art (Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sapouna-Sakellaraki1971). These trends received a boost from the first, synthetic study of Aegean prehistoric textile tools (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith1975), prompting attention to their systematic recording and collection. Moreover, textiles and textile production, seen as paradigmatic of a gendered division of labour, became analytical units in gender archaeology and a central theme in studies on female agency in history (Gero and Conkey Reference Gero and Conkey1991). The monumental work of E. W. Barber (Reference Barber1991), a milestone in the study of Aegean Bronze Age textiles, wove together all research traditions in a multifaceted and detailed treatment that transcended the geographic and chronological boundaries of the third and second millennia BCE Aegean. The social aspect of textile production was examined in the emblematic book by I. Tzachili (Reference Tzachili1997) through the case study of the Late Bronze Age (LBA) settlement of Akrotiri on Thera, within a gender archaeology perspective. Moreover, the emergence of experimental methodologies aiming at garment reconstruction (Jones Reference Jones1998) paved the way for a more grounded understanding of Aegean Bronze Age dress.

Over the past twenty years, research on Aegean Bronze Age textiles has seen remarkable growth. Scholarship has been influenced especially by the Centre for Textile Research (CTR), University of Copenhagen, which has led the methodological advances in the study of textile tools from a functional perspective (Andersson Strand et al. Reference Andersson Strand, Mannering, Nosch, Ulanowska, Grömer, Berghe and Öhrman2022). As a result, many scholars have taken up studies of textile technology, contributing to an unprecedented accumulation and synthesis of data. Besides a fresh look on second-millennium-BCE dress, this approach allowed for insights into the craft of the third millennium BCE, a historical context largely left out of discussions on Bronze Age textiles in earlier scholarship, given the limited iconographic evidence of dress and a total lack of documentary testimonies from the Early Bronze Age (EBA). Another recent development is the emphasis put on the technological analysis of excavated textiles and textile imprints. Although the Aegean region is not favourable to the preservation of organic materials in archaeological deposits, it is increasingly observed that textiles can survive in special taphonomic environments. New and old textile finds are being (re)examined by a new generation of textile scholars specializing in archaeometric techniques. Their results provide a wealth of information on textile craft.

In this Element, an overview of Aegean Bronze Age textiles and textile craft is presented that prioritizes the research of the past twenty years, integrating older finds and reports when necessary. Thus, the focus is on the advances made through the study and analysis of textile tools and excavated textiles and textile imprints of the Early, Middle, and Late Bronze Ages (Table 1, Table 2). The datasets of textile tools are large and ever-expanding, so that a choice of the most well-studied cases or those providing exceptional insight, proved unavoidable (Map 1). This choice renders this Element a frame of reference rather than an exhaustive treatment of the subject. The main insights resulting from the rich body of work on textile and dress iconography will be briefly addressed in Section 2.2.1, with references to seminal, relevant scholarly works. Where deemed necessary, issues of cloth iconography will be raised within the discussions on textile technology.

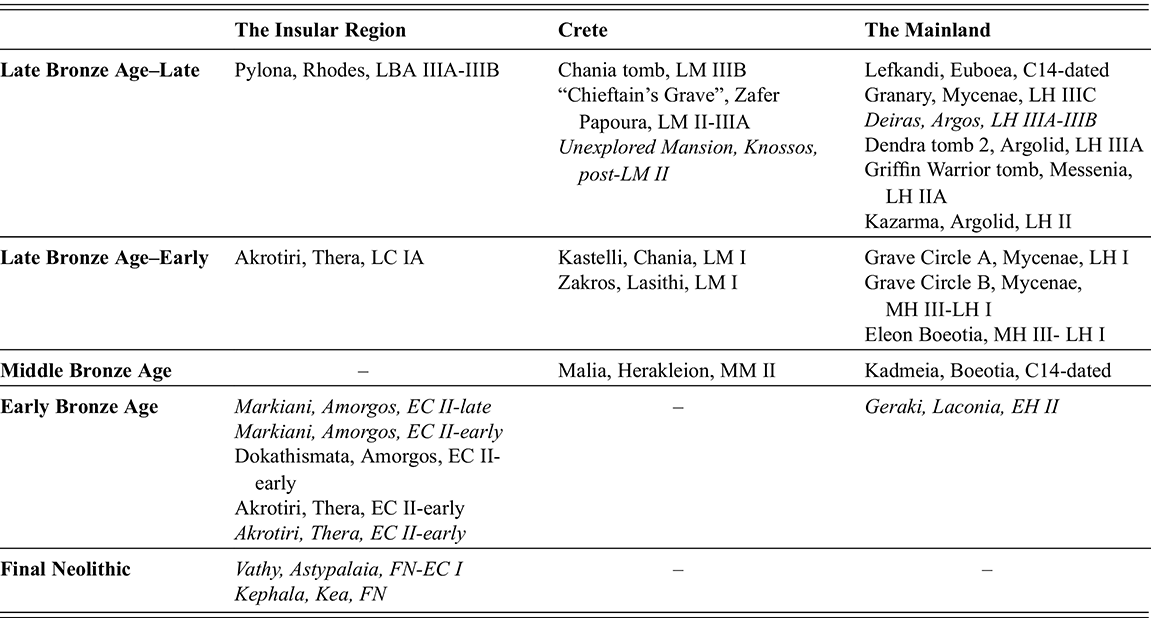

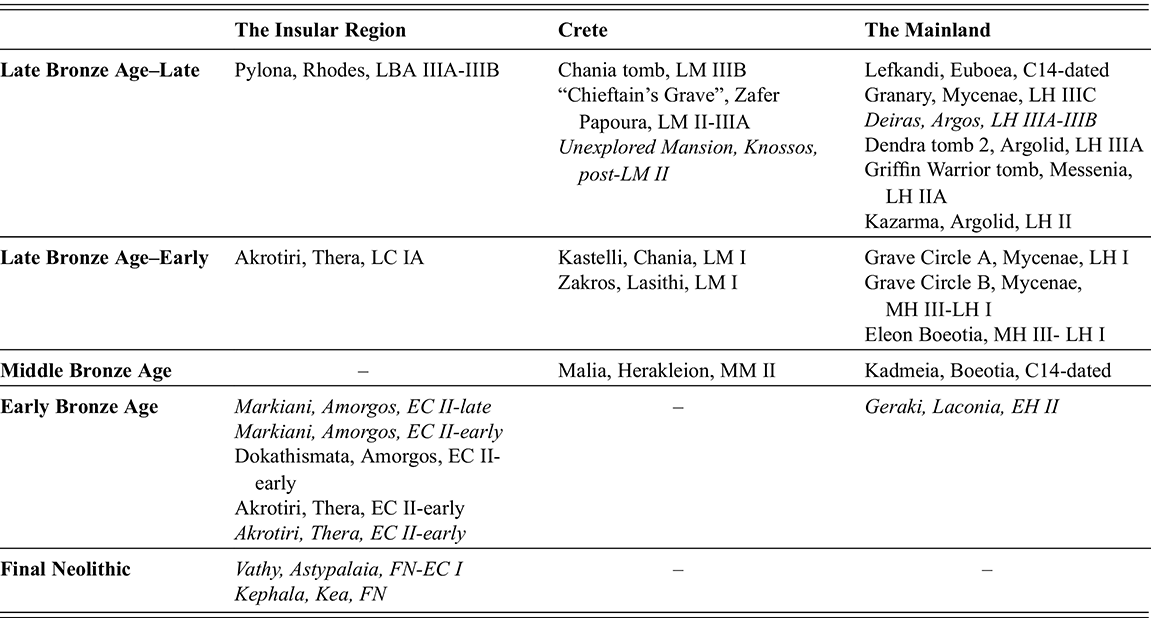

Table 1Long description

The table includes horizontal registers of textiles published to this date from Aegean archaeological sites on the Greek mainland, on the large island of Crete and on smaller islands of the Aegean archipelago, that are mentioned in the book. The earliest are two textile imprints dating from the period just before the beginning of the Bronze Age, called the Final Neolithic, and both were found on Greek small islands, Kea and Astypalaia respectively. The latest in date mentioned on the table is the garment and the rest of the textile corpus from Lefkandi, a site on the large island of Euboea, which was most probably a heirloom Mycenaean textile deposited in an Iron Age tumulus burial. In between the Final Neolithic and the Lefkandi corpus, are included textiles and textile imprints dating to the Early, the Middle and the Late Bronze Age.

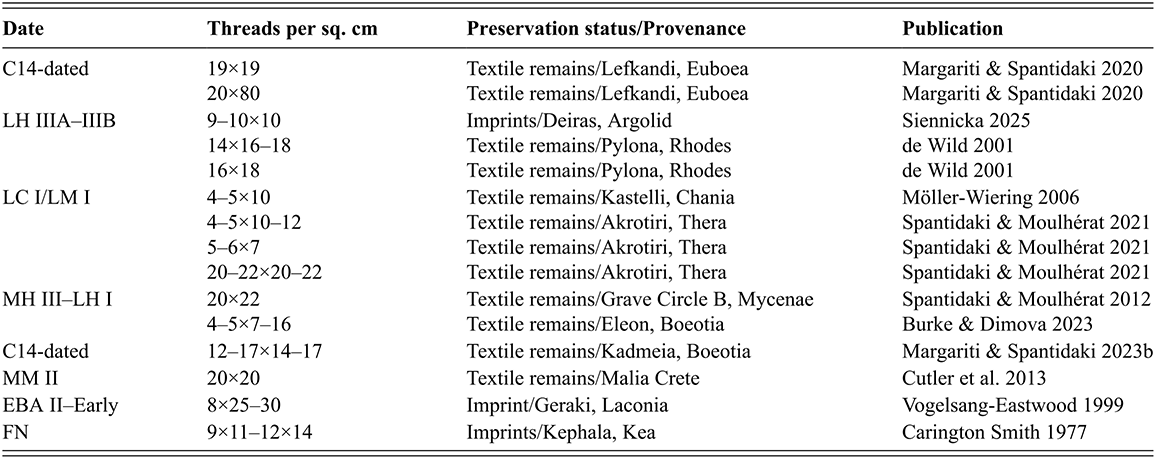

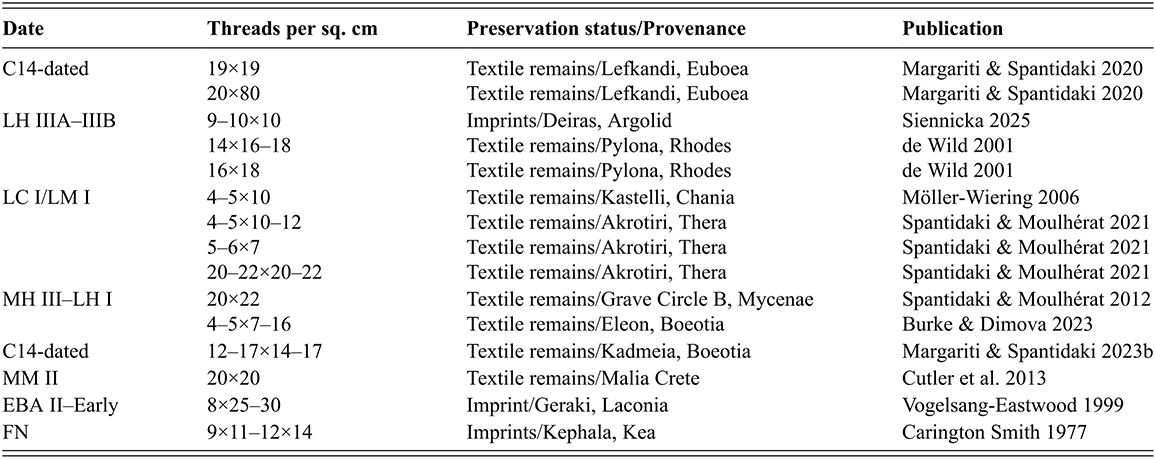

Table 2Long description

The table presents the textiles' thread counts per square cm., that have been published in the archaeological literature of the Bronze Age Aegean thus far. This count describes how many warp threads and how many weft threads occupy one square cm. of each textile. The table is organized chronologically with the earliest specimens on the bottom and the latest on top. The table showcases that as early as the Final Neolithic textles had thread counts of 12 threads versus 14 threads per square cm. It also shows that some very fine textiles had 20 threads versus 20 threads per square sm. The most densely packed thread system mentioned in the table is found in a textile from Lefkandi, Euboea, dated to the end of the Late Bronze Age, with 20 threads versus 80 threads per square cm. For each textile in the table, a bibliographical reference is also provided to indicate its original publication by scholars who studied these textiles and textile imprints.

Map 1 Place names and sites mentioned in the text.

2 Background to Aegean Textiles Research

2.1 Textile Craft: Basic Operations and Definitions

Textile production in a pre-industrial technological frame entails a long and time-consuming operational sequence. Its basic stages include the procurement of fibres harvested from plant and/or animal sources, followed by untangling, cleaning and washing the fibres; manufacturing and dying thread (or yarn); fabricating cloth through weaving or other techniques; adding finishing details such as decorative elements during or after weaving; and/or tailoring (Andersson Strand 2015). However, the archaeological visibility of any of these stages depends on the material residues of the manufacturing processes. In the frame of Aegean prehistory, the textile works most frequently represented in the archaeological record are manufacturing thread and weaving cloth, through the recovery of textile tools such as spindle whorls and loomweights.

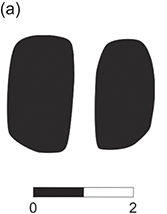

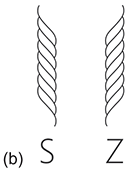

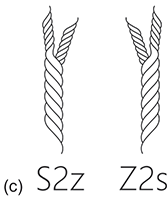

A spindle whorl is an accessory to the spindle, a thin rod, used in the process of twisting fibres into thread, or for plying single threads into thicker ones. It has a simple function but its handling requires skill: the spinner draws a few fibres from a mass of raw material that is fixed on a distaff, attaches these to the tip of the rod, and twirls the spindle while continuously drawing some more fibres. As the rod rotates, the fibres are spun into thread, while the spinner continues ‘feeding’ the spindle, drafting more material from the distaff. The whorl, which has a circular shape, is fixed on the rod through its central perforation and with its weight reinforces the rotation of the spindle (Barber Reference Barber1991, 56–59) (Figure 1a). The spinner stops once in a while to reel the spun thread onto the spindle, and then continues drafting fibres and twirling the spindle. This is called draft-spinning (Barber Reference Barber1991, 41–51). Ethnographic documentation indicates that there exist various technical gestures for handling the spindle in draft-spinning (Vakirtzi et al. Reference Vakirtzi, Papayanni and Mantzourani2022, 175–181). Different gestures may result in distinct primary twist direction, which is conventionally defined with the letters z or s, in accordance with the central slant of these two letters (Figure 1b). E. Barber suggested that a general correlation among direction of primary twist, spinning gesture (suspended or supported spindle), choice of spindle (low or high whorl) and fibre type can be made: z-twist has been associated with suspended, low-whorl spindles and wool, while flax is correlated to high-whorl spindles rolled on the spinners’ thighs (Barber Reference Barber1991, 65–68). However, the more ancient textile analysis progresses, accumulating fresh data, the more Barber’s proposed correlation deserves re-evaluation. The combination of two z -twist threads into a secondary, plied one, manifests a secondary S-twist and is ascribed as S2z. Similarly, two primary s-twist threads plied together will result in a Z2s structure (Skals et al. Reference Skals, Möller-Wiering, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 62) (Figure 1c). A different technique of thread manufacture has been observed in excavated textiles, called splicing. Splicing entails joining individual fibres of plant origin, either continuously along their length or end to end, and then twisting them at their joints (or splices). Spliced threads are then twisted to create a stronger, plied thread, using the spindle (Barber Reference Barber1991, 47, Fig. 2.9; Gleba and Harris Reference Gleba and Harris2019). Depending on the method of manufacture, the threads manifest certain structural features. Spun threads have continuous twists all along their length. Spliced threads demonstrate minimal to no twist, but the joints between fibres may sometimes be distinguished. Because both techniques require the use of the spindle, it is difficult to ascribe ancient whorls straightforwardly to either, although in general splicing is associated with heavier rather than lighter spindle whorls (see Section 2.2.2).

a Spindle with whorl.

Figure 1aLong description

The spindle was made of a thin wooden rod and a round, centrally pierced weight made of clay, stone or bone, called a spindle whorl. Through its central perforation, the whorl was fixed on the rod’s distal end.

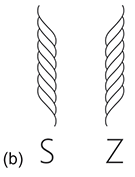

Figure 1b Single s- and z-twist threads.

Figure 1c Double S2z and Z2s threads.

Cloth can be produced with various techniques, such as plaiting, twining or felting (Emery Reference Emery1966), but in this Element the focus will be on weaving. This operation, at its most basic version, consists of interlacing two different thread systems – one passive and one active – at a right angle to each other. The threads of one system must be taut, while the threads of the other system are passed over and under them. These are called warps and wefts, respectively. Cross-culturally, several solutions were invented to keep the warp threads taut. These solutions correspond to different loom types. Two of the most well-known ones, the horizontal ground loom and the vertical loom, were certainly in use in the prehistoric Eastern Mediterranean and in the Near East (Barber Reference Barber1991, 81–90). The vertical loom had two basic varieties, the two-beam and the warp-weighted variety, the latter being our main interest in this Element, since it is the only type of loom securely identified from the Bronze Age Aegean, through the recovery of loomweights. We gain glimpses to their function through archaic and classical art (Barber Reference Barber1991, 110–113): these looms were constructed by two vertical supporting beams and an upper horizontal one, where the warp threads were tied to, or were let hanging from a ‘starting border’, a narrow strip of cloth. The lower ends of the warp threads were tied to loomweights that kept them taut so that weavers could pass in the weft threads, as vase paintings indicate (Supplementary Figure 1) (available to access at www.cambridge.org/Vakirtzi). They were also equipped with one or more wooden sticks or bars, called shed and heddle bars, to facilitate the mechanical opening of the warp threads and the faster passing of the weft (Barber 1991, Fig. 3.28). However, the exact structure of the Bronze Age Aegean warp-weighted loom is unknown. Nonetheless, it has been suggested that certain signs of the Linear A script such as AB54 (Figure 2) must have been inspired by the warp-weighted loom (Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010, 351).

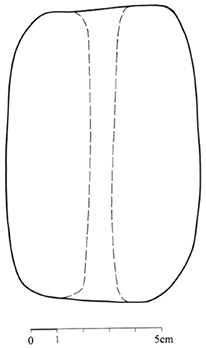

Figure 2 Schematic drawing of the Linear A sign AB 54.

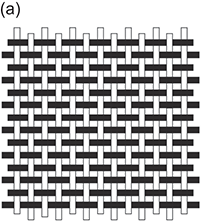

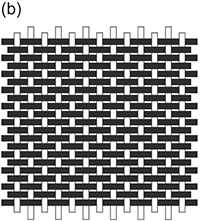

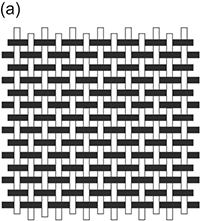

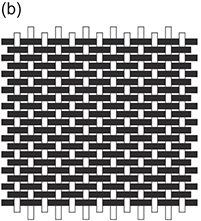

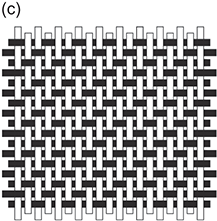

Warp-weighted looms can be used to create several different kinds of fabric structures (or weaves).Footnote 2 In the simplest weave, one thread system passes over and under the threads of the other system. This is called plain or tabby. It may have several variations. In the variety of ‘balanced’ plain weave, the warps and the wefts have approximately the same count per square centimetre (sq. cm) (Figure 3a). When the threads of the warp system are considerably more than those of the weft system, and vice versa, then the weave is ‘faced’, described as warp faced or weft faced, respectively (Figure 3b). A more complex configuration is the diagonal weave, or ‘twill’, where the weft passes alternately over a number of warps and then under a different number of warps (Figure 3c). More sophisticated weaves combine the plain (or tabby) structure with supplementary or floating warp or weft threads inserted by the weaver by hand in the basic (or ‘ground’) fabric, or thread-looping techniques, to create decorative patterns. Tapestry is a more complex structure, developed primarily for creating coloured patterns by inserting discontinuous weft threads of different colours in the weave, following a predetermined design, and is, by definition, a weft-faced type of textile (Emery Reference Emery1966, 78; Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood, Nicholson and Shaw2000, 278). Tapestries from the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean have been found in Egypt (Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood, Nicholson and Shaw2000; Spinazzi-Lucchesi Reference Spinazzi-Lucchesi2018), where they are associated to the emergence of the artistic representation of the two-beam loom, and in Syria (Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, Appendix B, with references). Moreover, tapestry is presumably implied by some textile terms found in the Old Assyrian records of Kanesh dating to the nineteenth century BCE (Smith Reference Smith, Nosch, Koefoed and Strand2013, 162, with references). All types of weaves can be further elaborated by fringes, tassels, embroideries and other techniques (Barber Reference Barber1991, 126–144, 166–174).

Figure 3a Plain (tabby), balanced weave.

Figure 3b Plain (tabby) weft-faced weave.

Figure 3c Twill (diagonal) 2/1 weave.

2.2 Sources of Textile Evidence from the Bronze Age Aegean and Methodologies of Research

2.2.1 Cloth Representations

The depiction of clothed human figures in Aegean Bronze Age art is one of the most important sources of textile iconography, thus the discourse on textiles is often conflated with the discourse on dress. For half of the period under discussion, specifically the EBA or the third millennium BCE, the iconographic record related to cloth is limited. The representation of the human body in the art of this period is mostly rendered in three-dimensional figurines modelled either in clay or in stone and less frequently in bone or metal (Marangou Reference Marangou1992). Regardless of region, material, or stylistic tradition, scholars have observed that EBA figurines rarely incorporate iconographic details that can be informative on clothing and textiles (Marangou Reference Marangou1992, 189–190; Mina Reference Mina2008, 87).

The naturalistic marble Cycladic figurines and their Cycladicizing counterparts, dating from the EBA II onwards, mostly give the impression of the naked human body. Exceptions include figures with sculpted hats or narrow cross-bands worn on the torso to carry weapons such as daggers (Mina Reference Mina2008, 87). However, these bands could have well been manufactured from leather and are not certain to represent textiles. A few clay figurines from this period often bear painted or incised motifs that have been interpreted as clothing items like caps, belts and bands worn around the waist or the hips, as well as cross-bands over the chest (Mina Reference Mina2008, 87). Examples include figurines from Lerna with painted cross-bands on the torso, areas hatched with parallel lines or belts on the waist (Banks Reference Banks1967, 643, Pl. 20; Marangou Reference Marangou1992, 190, Fig. 81) and from Thermi on the island of Lesbos, in the East Aegean, dated from the Third town onwards (Philaniotou Reference Philaniotou, Marthari, Renfrew and Boyd2019, 146). Some of the Thermi figurines bear incised motifs that have been interpreted as dress items (Figure 4), such as a fringed string tied in a knot behind the neck, cross-bands on the chest and a hip-long garment with fringes hanging from its hem on the waist and hips, with punctured dots that were suggested to depict embroidery (Lamb Reference Lamb1928–1929/1929–1930, 31–32, Pl. VIII). In Crete, a class of anthropomorphic clay vessels dating from the Early Minoan (EM) II to the Middle Minoan (MM) IA includes examples that bear painted motifs (Figure 5). Such vessels with painted hatched triangles or rectangles, or elaborate horizontal and vertical bands, are published from the EM settlement of Myrtos (Warren Reference Warren1972, Plates 69–70), from Koumasa, Mochlos, Malia (Warren Reference Warren and Rizza1973, with references) and Phourni-Archanes (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki1997, 540–541). These anthropomorphic vessels have been considered as representations of female deities wearing elaborate dress (Warren Reference Warren and Rizza1973). However, Jones (Reference Jones2015, 13–22) rejects the interpretation of the painted motifs as garment depictions, arguing that they are typical, decorative patterns on EM non-anthropomorphic pottery.

Figure 4 Clay female figurine, from Thermi, Lesbos.

Figure 5 Clay anthropomorphic rhyton, from Malia, Crete.

Other artistic media with presumed dress iconography from the transitional period between the third and second millennia BCE include some Cretan figurines made of bone, stone, and metal, as well as figures carved on Cretan seals. Two figurines made of hippopotamus ivory and another made of marble, found in the Hagios Charalambos cave in the Lasithi area, East Crete, and attributed to the EM III-MM IA period, have body shapes that lack a clear distinction of the legs and have thus been considered as clothed in cloaks or long dresses (Ferrence Reference Ferrence, Stampolides and Sotirakopoulou2017). A metal anthropomorphic figurine from Archanes, dating to the end of the Prepalatial or the beginning of the Protopalatial period, was cast in a shape that suggests a foot-length garment (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki1997, 527). It was interpreted as a male ‘wearing female dress’ by the excavators (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki1997, 527) but was considered as a female wearing a bell-shaped skirt by Stefani (Reference Stefani2013, 47–54). Some representations of clothing are also encountered on figurines and seals found in funerary contexts from the Tholos Tombs of Mesara, like the ivory female figurine from Platanos, with a long skirt bordered by parallel bands on the hem (Stefani Reference Stefani2013, 49), and the ivory seal from Archanes depicting a female figure with a long dress and a high collar, known as the ‘Medicis Collar’ (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki1997, 675–676).

In the course of the Middle Bronze Age, the representation of human clothing found new expression in Cretan art. The anthropomorphic clay figurines found in large quantities in peak sanctuaries render both female and male dress: long, bell-shaped or pleated skirts with wide belts tied in elaborate knots and various types of hats for women (Stefani Reference Stefani2013, 55–79), as well as various types of loincloths and belts for men (Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sapouna-Sakellaraki1971, 7–29; Rehak Reference Rehak1996, 42–43). The details of patterned cloth did not escape the attention of figurine makers: the painted bands on the garments of female figurines from Petsofas (Supplementary Figure 2) is one such case, probably corresponding to colour-patterning. Such patterning has been suggested to be the result of either weaving with supplementary weft techniques or of sewing narrow bands on the hems of skirts (Stefani Reference Stefani2013, 60).

While these developments in representational art were underway on Crete, human imagery was rare in the Middle Bronze Age art of the Greek Mainland and in the rest of the insular Aegean (Tzonou-Herbst Reference Tzonou-Herbst and Cline2012, 215). Pictorial art is largely lacking from the Middle Helladic (MH) material culture (Blakolmer Reference Blakolmer, Philippa-Touchais, Touchais, Voutsaki and Wright2010), rendering the clothing of this period archaeologically invisible. In the insular region, human representation is rare, schematic and mostly confined to vase painting. For example, at Akrotiri, Thera, the human figure as a theme in vase painting of the early second millennium BCE (Doumas Reference Doumas and Vlachopoulos2018) provides few clues to dress of the Middle Cycladic (MC) period. A few anthropomorphic figures depicted on local pottery sherds are rendered in hourglass shape (Nikolakopoulou Reference Nikolakopoulou2019, 276, Fig. 3.2), indicating, at best, knee-length garments (kilts?) (Figure 6). Slightly later, but still in the MC period and locally produced, is an exceptional bichrome jug with a ‘pouring scene’, depicting two males dressed in ‘Minoan cloth’ (Nikolakopoulou Reference Nikolakopoulou2019, Vol. I, 282, Fig. 3.8, Vol. II, 230).

Figure 6 Pottery sherd with painted schematic male figures, from Akrotiri, Thera (Doumas Reference Doumas and Vlachopoulos2018, 31, Fig. 4 c).

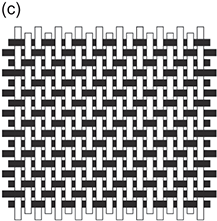

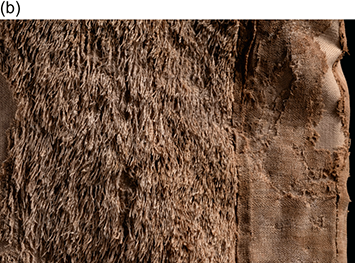

The artistic landscape changed radically in the period marked by the emergence of the New Palaces on Crete, towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age, in the MM III phase. Along with the art of wall-painting, eventually adopted in the Cyclades and the mainland, a rich iconography of clothing emerged, and one that now represented elaborately patterned, multicoloured textiles. Moreover, anthropomorphic figurines crafted in metal, ivory, stone or clay, and developments in glyptic, enrich the sources of cloth iconography. These artistic representations showcase a wide range of garments, including various types of skirts (bell-shaped, flounced, fringed, pleated, with horizontal bands), as well as pants, loincloths, kilts, mantles, long robes with diagonal bands, tight bodices with narrow hem-bands and tassels, aprons, belts and hats (Figures 7–8, Supplementary Figures 3–4). Among these are also items such as knots, scarves and cloaks or garments that are depicted either independently of human figures or as being carried by them, presumably with a symbolic or cult significance (Figure 9, Supplementary Figure 5). Given the identification of the narrated themes or episodes, these dresses and individual cloth items have been characterized as prestige, ritual or sacred (Crowley Reference Crowley, Nosch and Laffineur2012; Boloti Reference Boloti, Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014; Jones Reference Jones2015; Blakolmer Reference Blakolmer, Pavúk, Klontza-Jaklová and Harding2018). Colours, ornamental styles, decorative techniques, embroidery, tailoring and sewing, as well as regional fashions, have been identified in the dress imagery of the LBA (Barber Reference Barber1991, 312–357; Stefani Reference Stefani2013). Research has suggested a distinction between ‘Minoan’ and ‘Mycenaean’ garments, based on this corpus of representations. For example, characteristic types of ‘Minoan’ female dress include the ‘fleece’ or ‘animal-hide’ skirt; the ‘bell-shaped skirt’ and the ‘flounced’ skirt combined with the tight bodice; and several types of pants and headdresses, most of which appear to be richly patterned (Stefani Reference Stefani2013). ‘Mycenaean’ female dress, in contrast, is represented by an ‘all covering chemise’ of less elaborate decoration (Barber Reference Barber1991, 315) or a ‘long robe’ with bands on the hem, and often with a vertical band as well (Boloti Reference Boloti, Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014). Nonetheless, a degree of influence and hybridization between the two cloth-culture spheres has been acknowledged, best expressed in the multi-figured scene painted on the LM III sarcophagus of Ayia Triada, Crete: the types of garments worn by female and male actors within the same ritual episode include both Cretan and mainland elements (Burke Reference Burke2005; Boloti Reference Boloti, Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014).

Figure 7 Girl with patterned flounced skirt and bodice, covering her figure with a crocus-coloured, red-dotted, transparent, long veil. Detail from ‘The Adorants’ Fresco, Xeste 3, from Akrotiri, Thera.

Figure 7Long description

The painting depicts a girl wearing elaborate clothing. Her whole body is covered with a yellowish, transparent veil decorated with small red dots. Beneath the veil, she wears a long skirt with flounces and a tight chemise called a “bodice”.

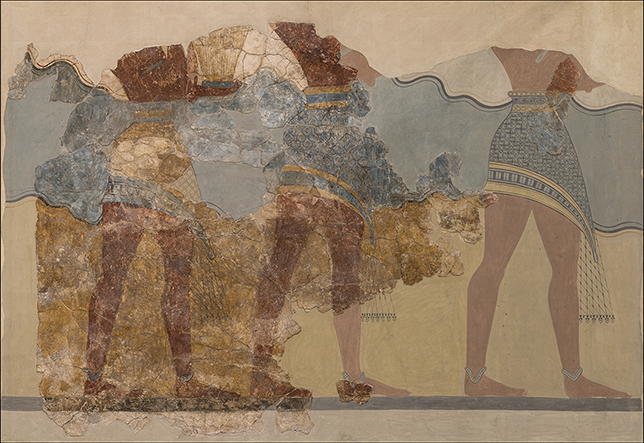

Figure 8 Male figures in procession, wearing colourful, patterned kilts. Detail from the ‘Procession Fresco’, from Knossos, Crete (inv. nr. T3 ©Archaeological Museum of Heraklion/ODAP/Hellenic Ministry of Culture).

Figure 8Long description

The painting depicts the lower bodies of three men walking in procession. All three are depicted wearing thigh-length garments called kilts, made of colourful, patterned fabrics, bordered by coloured, textile bands near the hems.

Figure 9 Faience replica of a dress composed by a long skirt decorated with crocuses, a double belt and a tight bodice, from the Temple Repositories, Knossos, Crete.

Figure 9Long description

The object resembles a garment consisting of a long, bell-shaped skirt and a tight, short-sleeved chemise known as “bodice”. The skirt is decorated with painted crocus flowers. The garment also includes a double belt on the waist.

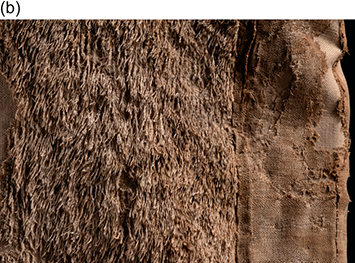

Textile patterns as depicted in LBA dress iconography have received a special focus from scholars. A variety of elaborate and detailed floral and geometric motifs, and in a few cases figurative ones, too (Barber Reference Barber1991, 317–321) appear to have been embellishing the textiles that were tailored into female and male garments. Some of these patterns are not exclusive in the depiction of dress. Wall-painting and vase painting share in this rich repertoire of motifs as well (e.g., Betancourt Reference Betancourt, Gillis and Nosch2007; Hatzaki Reference Hatzaki and Vlachopoulos2018). Careful observation of the iconographic details of these garments and textiles supports theories on the artistic conventions employed to render different cloth textures. Cases in point are the ‘transparent’ dress items and the ‘fleece’ or ‘animal-hide’ skirts. Transparent textiles are identified when the contours of a garment contain the depiction of other items of clothing, or of the arms and legs of human figures, suggesting visibility beneath the cloth (Stefani Reference Stefani2013, 109–110). The ‘fleece’ or ‘animal-hide’ skirt, first attested in ceramic vase painting of Protopalatial Phaistos, recurring in Neopalatial seals and last represented on the Ayia Triada sarcophagus mentioned earlier (Stefani Reference Stefani2013, 104–107), conveys a ‘woolly’ impression. This was suggested to reflect weft-looping (Tzachili Reference Tzachili1997, 242–243), a technique which involves loosely twining supplementary wefts around the warps in a way that leaves small loops hanging on the surface of the woven cloth. This technique survives on actual cloth fragments found in Middle Kingdom Egypt (Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood, Nicholson and Shaw2000, 276).

Besides human dress, LBA iconography informs us on the use of products such as sailcloth, strings, ropes, and nets for captivating animals (e.g., Doumas Reference Doumas1992, Papageorgiou Reference Papageorgiou, Doumas and Devetzi2021, Betancourt Reference Betancourt, Gillis and Nosch2007). These fibre-based artefacts are created with the same manufacturing principles and materials that are also used for weaving cloth for garments. Thus, their study adds important layers of information for a broader understanding of textile crafts (Vakirtzi et al. Reference Vakirtzi, Georma, Karnava, Ulanowska and Siennicka2018).

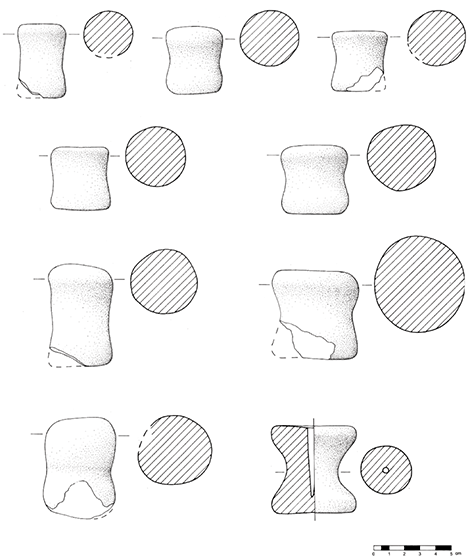

2.2.2 Textile Tools and Production Facilities

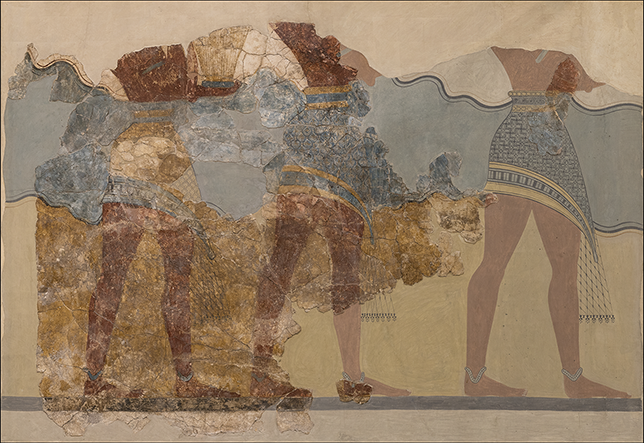

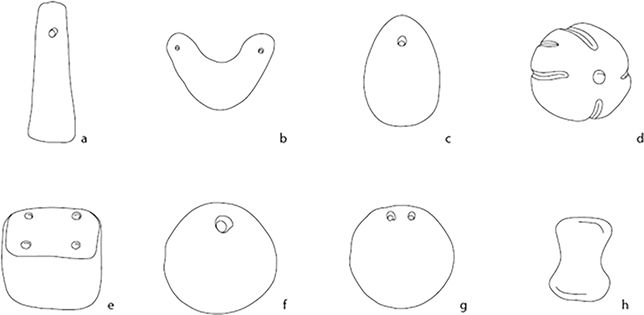

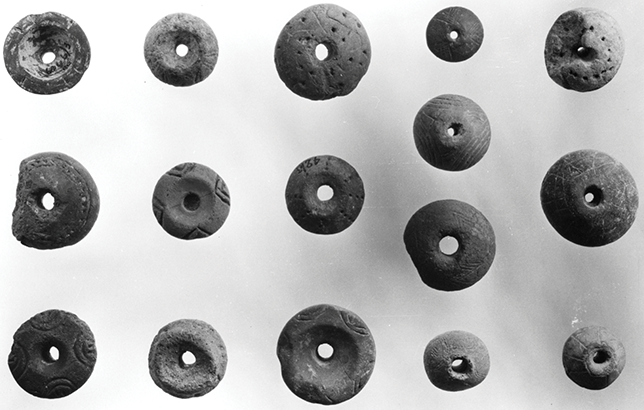

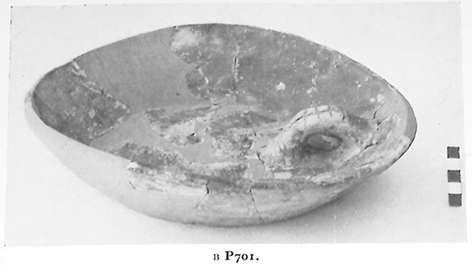

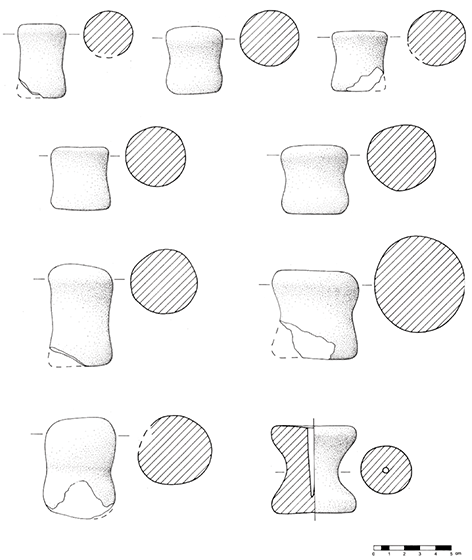

The most frequently occurring tools in Aegean Bronze Age archaeological deposits are the remains of spindles and warp-weighted looms, namely spindle whorls and loomweights (Barber Reference Barber1991; Tzachili Reference Tzachili1997). Other textile implements found in Bronze Age sites include needles made of bone or metal, spinning bowls, that is, a type of clay bowl used for plying thread, pointy bone tools usually identified as pin beaters and pierced spools which have been interpreted as reels possibly related to warping. Throughout the Bronze Age, spindle whorls and loomweights were manufactured in a variety of shapes and sizes (Figures 10–11) and with materials such as clay, stone, or bone. Established tool typologies (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith1975; Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015) facilitate the identification of these objects in the field, but certain types of ambiguous objects are more difficult to identify as implements related to textile craft (Barber Reference Barber1991, 91–93).

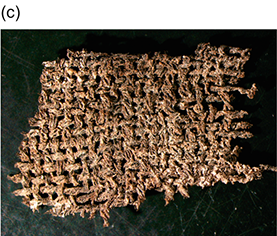

Figure 10 Basic spindle whorl types from Bronze Age Aegean sites. From left to right, upper row: biconical, conical, spherical. Lower row: hemispherical, cylindrical, discoid.

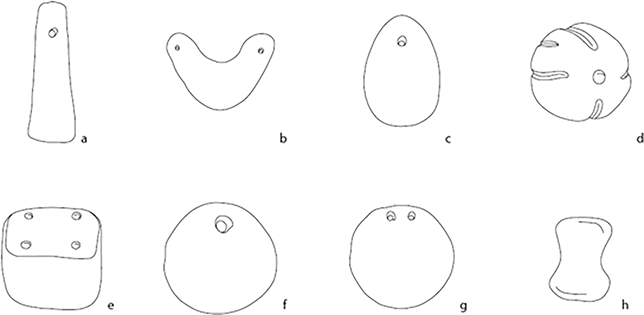

Figure 11 Basic loomweight types from Bronze Age Aegean sites. Upper row: (a) pyramidal, (b) crescent-shaped, (c) piriform, (d) spherical, (e) cuboid, (f) round discoid with one perforation, (g) round discoid with two perforations, (h) spool-shaped

Figure 11Long description

Based on the loomweight form, these types are the a)pyramidal b) the crescent-shaped c) the piriform d) the spherical e) the cuboid f) the round discoid with one perforation g) the round discoid with two perforations and the spool-shaped.

Textile tools lend themselves to an array of analytical approaches. The most widely applied are distribution, typological, and functional analysis. Recently, the potential of clay provenance studies applied in textile tools analysis has been highlighted (Gorogianni et al. Reference Gorogianni, Cutler, Fitzsimons, Stampolidis, Maner and Kopanias2015; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi and Nikolakopoulou2019), which is especially promising in demonstrating the ‘mobility’ of textile craftspeople (Cutler Reference Cutler2021, 258). Another important aspect of textile tools study calls for collaboration with Aegean specialists in administration technologies, including stamping, marking and writing, because in certain cases Aegean Bronze Age textile tools bear traces of these practices on their surfaces (e.g., Vlasaki and Hallager Reference Vlasaki, Hallager, Poursat and Müller1995; Burke Reference Burke and Mountjoy2003; Tzachili Reference Tzachili and Doumas2007a; Burke Reference Burke2010, 57; Evely Reference Evely, Knappett, Cunningham and Palaikastro2012; Militello Reference Militello, Breniquet and Michel2014b, 276; Cutler Reference Cutler and Tsipopoulou2016b, 178; Karnava Reference Karnava2018, 162, 166; Karnava Reference Karnava and Nikolakopoulou2019, 502, with references; Tzigounaki and Karnava Reference Tzigounaki, Karnava, Stampolidis and Giannopoulou2020, 324; Siennicka Reference Siennicka, Quillien and Sarri2020; Cutler Reference Cutler2021, 145, 238). These practices are not yet well understood in terms of the relation between textile craft and the use of administration technology or the extent of Bronze Age ‘literacy’.

Distribution analysis permits the interpretation of the spatial configuration of tools found in archaeological deposits. On a first level, it aims to distinguish between secondary deposits such as backfills, destruction debris, or building materials where textile tools often end up after being broken and disposed of, and primary deposits implying use spaces, intentional deposition related to funerary customs or other special behavioural patterns (see Section 3.4). On a second level, when textile tools are found in primary deposition in use spaces, their distribution patterns may reveal the organization and scale of production. Distribution analysis may also allow the distinction between loomweights in storage and loomweights fallen from a set-up loom (see Section 3.4.3).

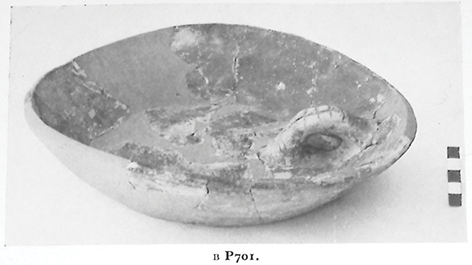

Typological analysis, a conventional archaeological methodology, has enabled the distinction between different manufacturing choices with regard to the shape and size of spindle whorls and loomweights. The first comprehensive survey of Aegean prehistoric textile tools, conducted by J. Carington Smith (Reference Carington Smith1975), led to the development of a detailed typology that remains a point of reference to this day. The attribution of textile tools to distinct types permits the comparison of different assemblages, ultimately allowing to discern patterns of continuity and changes in the habits of tool manufacture at the site level. Typological classification is also the basis of identifying regional interactions or influences among distinct communities of textile craftspeople, after mapping the various types of tools in geographical space. An example of this approach can be seen in the suggestion that the hollow (‘scodelletta’) spindle whorl type indicates the mobility of craftspeople over large spans of space and time (Barber Reference Barber1991, 299–310, see Section 3.1.1).

Functional analysis aims at interpreting the functional potential of textile tools. It is a method developed at the CTR aiming to correlate the tool shape and size with its intended function to produce specific results. In the case of loomweights, it is based on weaving experiments that demonstrated that the tools’ thickness and weight are important functional attributes (Mårtensson et al. Reference Mårtensson, Nosch and Andersson Strand2009). They influence the loom setup, that is, how densely-spaced the warp threads are, and also the types of threads (fine, medium, coarse) and how many threads can be attached to each loomweight (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 89–92). Thus, when archaeologists record the weight and thickness of loomweights found in archaeological deposits, they provide data that is essential to suggest potential loom setups, and eventually fabric types that could have been produced with a given yarn quality (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 95–97). The CTR team applied functional analysis to a large sample of Aegean Bronze Age loomweights and suggested that the metrological variation of textile tools reflects not simply preferences in loomweight design, but most probably corresponding preferences in different cloth types (Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 362–371). For example, it was demonstrated that when producing plain (tabby) weaves, thick loomweights are optimal for weaving ‘open’ fabrics, that is, cloth with loosely distanced warp threads, whereas thin loomweights are optimal for denser cloth (Andersson Strand Reference Andersson Strand, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015b, 143). Nevertheless, this method has its limits in reconstructing the end-product. The weave structure and the overall appearance of the finished fabric are not defined only by warp threads. Among other factors, the arrangement of weft threads also plays an important role in the final appearance of cloth, determining if the weave is balanced or not. For example, open weaves can be filled in by multiple counts of wefts, creating weft-faced fabrics. An important result of the research conducted by the CTR team is the suggestion that despite the wide range of loomweight types of the Bronze Age Aegean, several overlap in a functional sense. This means that although they have a different shape, some loomweights can yield similar results. The loomweight types that are clearly distinct from a functional perspective and would thus have been used for the production of different types of textiles are the spherical, the pyramidal, and the discoid (Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 371). Based on this assessment, it can be suggested that, although the warp-weighted loom technology was shared by craft communities in different regions of the Bronze Age Aegean, the cloth produced by these communities may have been considerably different from one place to the other. For example, when comparing weaving with pyramidal loomweights at EBA Sitagroi, northern Greece (Elster Reference Elster, Elster and Renfrew2003), to weaving with discoid loomweights at EBA Myrtos, southern Crete (Warren Reference Warren1972), it can be argued that, although both of these communities used the warp-weighted loom technology, their sense of textiles must have been very different, when considering the different functional potential that pyramidal and discoid loomweights have.

In the case of spindle whorls, scholars have been debating what constitutes the most crucial functional attributes that determine their effect on the spinning or plying process, and ultimately on the quality of the produced thread (Vakirtzi et al. Reference Vakirtzi, Papayanni and Mantzourani2022, 181–184). Nonetheless, there is general consensus that their weight is an approximate indication of the quality of fibres and the thread thickness (Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 359–362). In this rationale, significantly different spindle whorls, in terms of their weight, would be used to manufacture significantly different thread types. Fine yarns generally require well-processed, fine fibres to be spun with a spindle equipped with a light whorl. The manufacture of thick, single threads or plied ones requires using a heavier whorl. Spinning experiments conducted by the CTR have confirmed that the weight of the whorl can be indicative of the thickness of the thread, but it cannot be diagnostic of the fibre source, that is, the plant or animal species (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015). It has also been suggested that the whorl’s diameter affects the speed of rotation of the spindle, and therefore influences how loosely or densely spun the thread will be (Barber Reference Barber1991, 53; Olofsson Reference Olofsson, Strand and Nosch2015, 33; Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 87). Thus, for a functional analysis of spindle whorls, the first step requires recording the metric data of these tools, especially the weight and diameter values (Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, passim). By projecting these on a weight-diameter scatterplot, it is possible to demonstrate the frequencies of whorls of different sizes in the sample of tools under study, and to compare patterns of thread production in general, qualitative terms (e.g., Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, passim; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020).

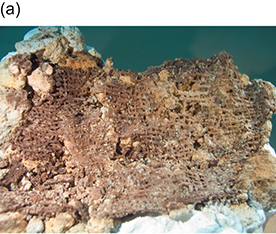

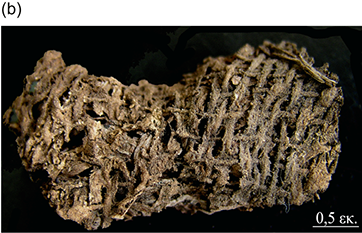

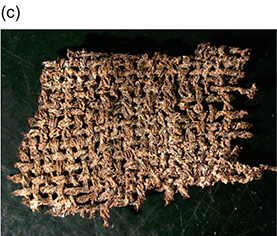

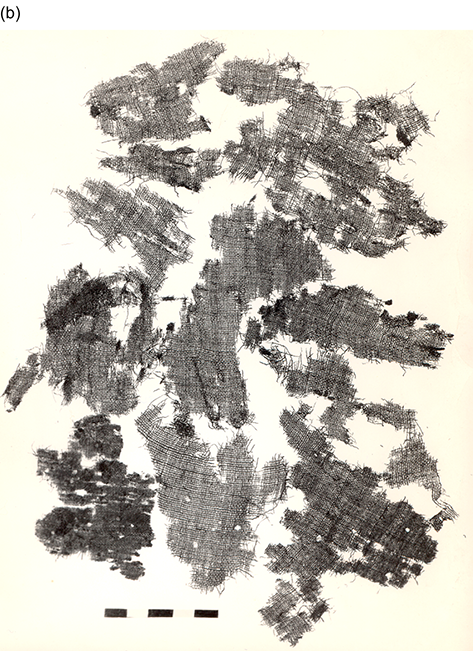

2.2.3 Excavated Textiles and Textile Imprints

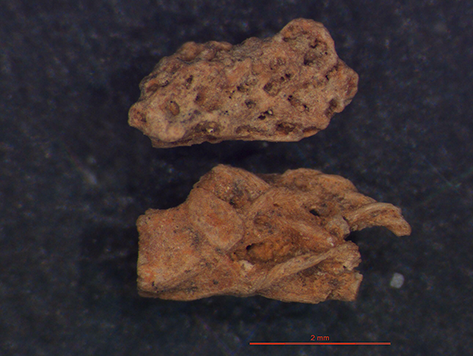

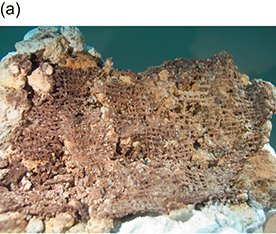

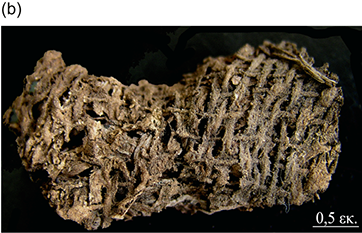

Textiles are repositories of a wealth of information on textile craft, ranging from fibre economy to textile technology, to styles and fashion. Depending on the degree of preservation of excavated textiles, the diagnosis of fibre type, thread-making technology, weave structure or pigments, may be possible, using an array of analytical instruments and physicochemical techniques (Margariti et al. Reference Margariti, Lukesova and Gomes2024). In the Aegean region textiles have survived in archaeological deposits usually following carbonization, mineralization, or calcification (Spantidaki and Margariti Reference Spantidaki and Margariti2017, 51). These are three distinct chemical processes, each triggered by specific pre-depositional or post-depositional conditions. Each of these processes alters the original chemical composition, appearance, and tactile effect of the textiles but at the same time prevents the activity of bacteria that cause the degradation of organic matter.

Excavated textiles can be observed using simple magnifying lenses or optical microscopy to determine the type of weave and to record the density of warp and weft threads in terms of thread count per sq. cm. Special features can also be recognized under low magnification, like the use of supplementary threads for decoration (e.g., embroidery, knotting) or reinforcement of the ground weave (e.g., in hems or selvedges) and even weaving mistakes (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith and Coleman1977). The compilation of such information can help identify techniques of weaving and distinguish patterns of preferred weave types, when plotting a large statistical sample in space and time (e.g., Gleba Reference Gleba2017). In the case of the Aegean region (including Mainland Greece), almost all extant textiles and textile imprints dating to the Bronze Age demonstrate plain (tabby) weave, in several variations (Spantidaki and Moulhérat Reference Spantidaki, Moulhérat, Gleba and Mannering2012; Spantidaki and Moulhérat Reference Spantidaki, Moulhérat, Doumas and Devetzi2021).

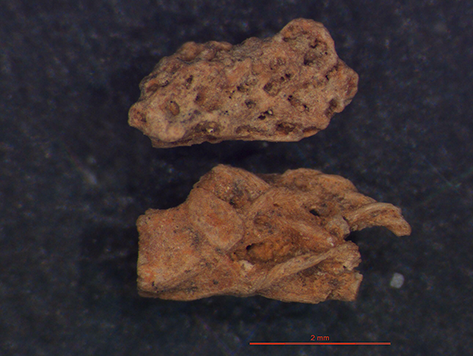

Thread-making technology can be deduced by observing threads or their imprints under high magnification. Spinning can be securely identified as the manufacturing technique when twists are observed all along the length of a thread. In contrast, when minimal twist is present, it is more probable that the technique of splicing had been used (Gleba and Harris Reference Gleba and Harris2019), even if the splices (the joints between individual fibres) are difficult to trace. In the case of spun threads, microscopic observation facilitates the examination of thread structure (single or double/plied) and technical details such as the direction of twist or the twist angle. Average thread diameter and spin direction of thread groups are important when attempting to discern between potentially different textiles found tangled together in an archaeological deposit. However, it should be kept in mind that all measurements taken from archaeological threads and fibres should be interpreted with caution, since experiments have shown that the original dimensions of threads can be distorted following carbonization, mineralization or other processes taking place after the deposition of textiles in the soil (Margariti Reference Margariti2020).

Fibre identification can be attempted with the SEM and Optical microscopes, each type providing certain advantages and constraints for ancient textile analysis (Lukesova and Holst Reference Lukesova and Holst2024). Details of fibre anatomy in mineralized and carbonized textile fragments can be observed under large magnification achieved with the SEM, provided that diagnostic anatomical features have been preserved. At the most basic level, analysis aims to distinguish between cellulosic and proteinaceous fibres, that is, those of plant and animal origin respectively. This is possible due to the distinct anatomical features exhibited by each of these two fibre categories (Rast-Eicher Reference Rast-Eicher2016, 11–42): in general, plant fibres are characterized by nodes along their length, while the surface of animal fibres is configured as small, pointy scales. To specify further the animal or plant species that had been sourced for their fibres, it is necessary to identify further morphological details, or to collect metric data that help distinguish among potential sources, based on a comparison of the archaeological fibres with those in reference collections (Rast-Eicher Reference Rast-Eicher2016). Physicochemical methods for fibre identification include various techniques. Among those, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Microspectroscopy, aiming at the definition of the chemical composition of the textile fragments, has been applied on Aegean material; however, the method is not suitable for carbonized textile fragments (Spantidaki and Margariti Reference Spantidaki and Margariti2017, 52). Recently, proteomics analysis has gained momentum in textile archaeology, as a new method of identifying animal textile fibres (Solazzo Reference Solazzo2019; Andersson Strand et al. Reference Andersson Strand, Mannering, Nosch, Ulanowska, Grömer, Berghe and Öhrman2022, 23). Studies aiming at textile fibre identification based on these advanced methods promise significant breakthroughs in our knowledge of prehistoric fibre economies.

Extant textiles are also potential sources of information on textile dyes when textile fragments preserve traces of colour. Dyes can be detected and chemically defined with spectrophotometric analytical techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid-Chromatography (HPLC) (Vanden Berghe Reference Vanden Berghe, Banck-Burgess and Nübold2013). Moreover, being organic materials, excavated textiles can be radiocarbon-dated (Margariti et al. Reference Margariti, Sava, Sava, Boudin and Nosch2023a).

Another source of information on textile craft is provided by the imprints of woven or plaited cloth and threads or strings, depending on the quality of the impression. They occur on clay (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith and Coleman1977; Vakirtzi et al. Reference Vakirtzi, Georma, Karnava, Ulanowska and Siennicka2018; Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska, Bustamante-Álvarez, López and Ávila2020), soil (Unruh Reference Unruh, Gillis and Nosch2007; Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos2024, 667–674, Figs. 11–12), plaster (Egan Reference Egan, Lepinski and McFadden2015; Vakirtzi et al. Reference Vakirtzi, Georma, Karnava, Ulanowska and Siennicka2018), and fine metal foil (Konstantinidi-Syvridi Reference Konstantinidi-Syvridi, Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014, 148–151, Fig. 6.15–6.17). They are created either with intentional pressure on a malleable, plastic surface, or by chance, retaining negative impressions of the original thread and cloth structures. Textile imprints analysis can yield information on thread and weave structures but they are not optimal for investigating fibre sources, since the microscopic diagnostic features of fibre anatomy will not leave any impression on clay, plaster, or soil. Nonetheless, the experimental creation and documentation of imprints of threads and strings made of various raw materials have the potential to facilitate the identification of fibres in archaeological imprints, after comparison with the experimental ones (Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska, Bustamante-Álvarez, López and Ávila2020). In considering textile imprints in this Element, only woven structures will be discussed, the imprints of threads and strings being too numerous to present here. A thorough documentation of thread and string imprints on clay sealings of the Bronze Age Aegean can be found in the database that resulted from the research project ‘Textiles and Seals’ directed by A. Ulanowska (https://textileseals.uw.edu.pl/database-description/).

2.2.4 Bioarchaeological Remains of Resources Related to Textile Raw Materials

Indirect evidence for the use of textile raw materials, such as fibres and dyes, may derive from bioarchaeological research. Zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical studies targeting, among other things, the analysis of faunal remains such as ovicaprid bones, and seeds or other parts of plants respectively, may produce results indicative of husbandry and agricultural regimes compatible with wool harvesting, flax cultivation, or other strategies for fibre collection. The detection of flax seeds in Bronze Age contexts (Valamoti Reference Valamoti2011) supports the hypothesis of flax cultivation, one of its probable uses having been for textile production. Sheep and goat bones are commonly found in faunal assemblages, potentially indicating wool production (Halstead and Isaakidou Reference Halstead, Isaakidou, Wilkinson, Sherratt and Bennet2011, 67–68). The moth cocoon of an insect that produces wild silk, found in an urban context in the Late Cycladic (LC) settlement of Akrotiri, Thera, has prompted a discussion on the possible use of wild silk as textile fibre (Panagiotakopulu et al. Reference Panagiotakopulu, Buckland and Day1997). Pina shells found in several Bronze Age sites indicate the possible exploitation of sea silk (Burke Reference Burke, Nosch and Laffineur2012; Soriga and Carannante Reference Soriga, Carannante, Enegren and Meo2017). Heaps of Hexaplex trunculus (murex) shells point to the production of purple dye (Ruscillo Reference Ruscillo and Mayer2005), known to have been used in textile production.

2.2.5 Textual Sources

The corpus of Mycenaean documents written in the Linear B script, spanning a period of about 200 years, is an important source of information on textile economy and craft. These texts are records of the ‘palatial’ administration of economic resources, raw materials, people, and finished products, and they reflect several aspects of textile production as it was run and supervised by the central authorities of the Mycenaean centres of the southern Greek Mainland and Crete (Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007). A high level of craftsmanship and specialization is conveyed in the documents, indicated by professional designations related to textile production. Among these are the spinner (a-ra-ka-te-ja), the weaver (i-te-ja), and the seamstress (ra-pi-ti-ra), while other terms, usually in the feminine, are more obscure in their meaning (Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010). Moreover, the Linear B texts collectively refer to several different, more or less standardized types of textiles or garments (Nosch Reference Nosch, Carlier, de Lamberterie and Egetmeyer2012; Nosch Reference Nosch, Breniquet and Michel2014), some of which are described with reference to their colour. A large group of the tablets found at Knossos record the complete cycle of wool production and processing, from the management of sheep (Rougemont Reference Rougemont, Breniquet and Michel2014) to the allocation of the raw material to textile workers and the delivery of finished items (Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007, 52–53; Nosch Reference Nosch, Breniquet and Michel2014). Apart from wool, the only other type of textile fibre identified in the Linear B terminology is flax, in the designation of cloth items as ri-ta, linen (Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010, 344).

The Linear B texts are the earliest, secure testimony from the Aegean region for a gendered division of textile labour. Women and girls enlisted in the palatial workforce of cloth production outnumber references on men who were most probably involved in the finishing stage of the operational sequence (Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007, 55). The status of these women is not clear, and was probably not homogeneous from one place to the other. At best, however, they were semi-dependent from the central administrations, since the texts testify that they received rations of food from the palatial authorities. The tablets of Pylos hint at the possibility that some of the female workers were captives of war (Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007, 56). The picture emerging from the Mycenaean texts on the organization and specialization of the palatial textile industries should not be considered necessarily representative for non-palatial contexts of production, or for the total chronological span of the Bronze Age.

2.2.6 Experimental Methodologies in Aegean Textiles Research

Experimentation as a research methodology for understanding ancient textile craft has a long tradition in northern Europe, especially in Scandinavia (Olofsson Reference Olofsson, Strand and Nosch2015, 25–29, with references). Experimental methods target two main research themes: first, the reconstruction of ancient textile technologies (e.g., Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Andersson Strand and Nosch2015; Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska2016, 325–327; Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a; Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018b) and second, the reconstruction of garments and other textile items depicted in art iconography or found as textile remains (Jones Reference Jones2015).

Specialists in Aegean Bronze Age textiles have often included craft experiments and related reconstructions in their studies (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith, Macdonald and Wilkie1992, 675, 694, Plates 11.1–11.11; Barber Reference Barber, Shaw and Chapin2016, 205), however systematic employment of the experimental methodology in research projects has so far been pursued at the University of Copenhagen (research project ‘Tools and Textiles-Texts and Contexts’ at CTR) and at the University of Warsaw. Besides testing the function of spindle whorls and discoid loomweights (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 77–78), the CTR experiments included weaving on a warp-weighted loom with the use of copies of crescent-shaped loomweights (Wisti-Lassen Reference Wisti-Lassen, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015) and copies of unpierced clay spools found at Chania, Crete, used as loomweights (Olofsson et al. Reference Olofsson, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Strand and Nosch2015, 92–95).

A series of systematic experiments with copies of possible textile tools was carried out at the University of Warsaw. One of those targeted exploring the potential loomweight function of unpierced clay spools (Siennicka and Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska2016). The working hypothesis of the experiment was that, depending on their size, these objects were multi-purpose within the frame of textile craft (bobbins for thread, tablet-weaving weights, loomweights, shuttles, reels used in the warping of the horizontal ground loom, implements for other cloth-producing techniques such as plaiting). Another experiment at the University of Warsaw focused on weaving with the use of the rigid heddle, a simple device for interlacing warp and weft, not identified so far among the material remains of textile tools recovered from the Bronze Age Aegean (but see Nosch and Ulanowska Reference Nosch, Ulanowska, Boyes, Steele and Astoreca2021, 92–94, for the interpretation of a sign of the Cretan Hieroglyphic script as a rigid heddle referent). Moreover, the manufacture of clay loomweights similar to those of the Aegean Bronze Age was carried out, as well as weaving on a warp-weighted loom (Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska2016).

The patterned, often multicoloured, and occasionally figured textiles of the garments depicted on the wall-painting and glyptic art of the second millennium BCE have been the focus of extended discussion on textile motifs and manufacturing techniques (Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sapouna-Sakellaraki1971, 153–195; Barber Reference Barber1991, 311–382; Tzachili Reference Tzachili1997; Jones Reference Jones2015; Shaw and Chapin Reference Shaw, Chapin, Shaw and Chapin2016; Peterson Murray Reference Peterson Murray, Shaw and Chapin2016; Sarri Reference Sarri, Mannering, Nosch and Drewsen2024). Experimental weaving has been employed to recreate textile patterns similar to those represented in Aegean Bronze Age art and to explore alternative hypotheses on the techniques, the tools and the skill required for pattern-weaving (e.g., Barber Reference Barber1991, 325–326; Spantidaki Reference Spantidaki, Alfaro and Karali2008; Ulanowska Reference Ulanowska, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a).

Experimental reconstruction of complete dresses is exemplified in the work of Bernice Jones (Reference Jones2015, with references). In her work, Jones stresses the importance of observing details on the artistic representation of dress, to understand the design and the sartorial choices that would have ultimately shaped the various types of Aegean garments.

3 Weaving the Threads of Aegean Bronze Age Textile Histories

This section weaves together the results of studies on textile tools, production facilities, and excavated textiles of the Bronze Age Aegean. It is structured around a basic chronological framework, following the conventional division into the Early, Middle, and Late Bronze Age – the latter further subdivided into an early and a late phase. Within each chronological period, the material is organized geographically into three main regions: Crete, the (remainder of the) insular region, and the Greek Mainland. Each regional section is then divided into two parts, according to the main categories of archaeological evidence: (a) textile tools and production facilities, and (b) excavated textiles and imprints. This regional and categorical structure is not rigidly repeated within every chronological section. Instead, the narrative flows from one region or category to another, guided by content-based considerations – such as the availability of evidence and the extent to which earlier discussions inform subsequent ones. For instance, the Early Bronze Age section begins with the insular region, where the earliest imprints of Aegean woven textiles were testified in Final Neolithic to Early Cycladic I contexts on the islands of Kea and Astypalaia respectively. The Middle Bronze Age section, however, begins with Crete because its textile-related archaeological record provides the background to understand the textile craft of the second millennium BCE in the Aegean region as a whole.

3.1 The Early Bronze Age

3.1.1 The Insular Region

Excavated Textiles and Imprints

By the beginning of the EBA, finely woven textiles were used in the Aegean region. Evidence for this exists in the form of a few textile imprints, like those on the soil that was filling the clay vessel used for an infant inhumation, found at Vathy, Astypalaia (Vlachopoulos Reference Vlachopoulos2024, 667–674, Figs. 11–12), and in the walls of pottery sherds found at Kephala on Kea, presumably created during the manufacture of the respective pots (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith and Coleman1977), dated as early as the Final Neolithic period. It is clear, therefore, that the textile craft practiced at the dawn of the third millennium BCE did not emerge in a vacuum but was drawing from the achievements and traditions of centuries-old technologies.

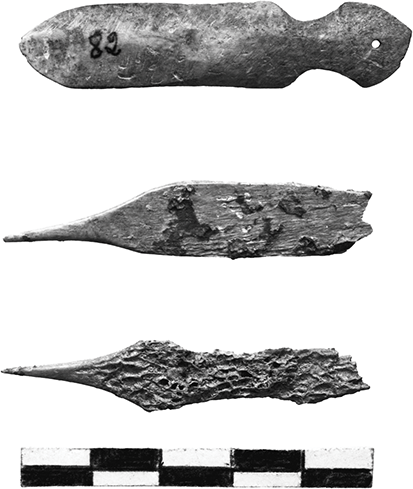

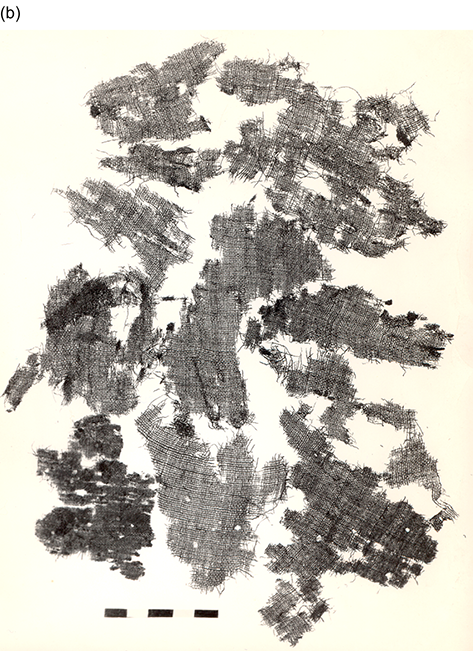

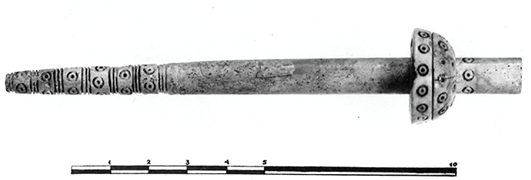

Several centuries of cloth production intervene between the Kea imprints and the next direct textile evidence from the insular Aegean (Table 1, Table 2). At the Early Cycladic (EC) II cemetery of Dokathismata, on the island of Amorgos, one of the graves included a bronze dagger (Figure 12) that preserved the mineralized fragment of a textile on its surface (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018, 182). The fragment appears to have belonged to a finely woven cloth. Although described as linen in the literature (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018, 182; Barber Reference Barber1991, 174, n.12), no fibre analysis for this textile has been published to date.

Figure 12 Bronze dagger with mineralized textile fragment from Dokathismata, Amorgos, Cyclades.

More evidence of cloth from EC Amorgos, in the form of textile imprints, emerged from the excavation of Markiani, a settlement on a rocky slope that was founded in the early third millennium BCE (Marangou et al. Reference Marangou, Renfrew, Doumas and Gavalas2006). Three pottery sherds from the site manifest imprints of woven structures that were identified as cloth (Renfrew Reference Renfrew, Housley, Manning, Marangou, Renfrew and Gavalas2006, 199, Fig. 8.18, Plate 45). All three show plain weaves. The contexts of these sherds were dated to Markiani phases III and IV (EC II early and late phases respectively) (Renfrew et al. Reference Renfrew, Housley, Manning, Marangou, Renfrew and Gavalas2006).

Another case of woven cloth impressed on a malleable surface derives from Akrotiri, Thera. A cylinder of reddish-orange pigment was found in an EC context and thus quite probably dates from the third millennium BCE (Birtacha et al. Reference Birtacha, Sotiropoulou, Perdikatsis, Apostolaki, Doumas and Devetzi2021). Its surface preserves the imprint of a woven structure and a rectangular stamp impression. The cloth imprint reflects plain weave and is described as ‘fine and coarse’ so at least two qualities of fabric are attested (Birtacha et al. Reference Birtacha, Sotiropoulou, Perdikatsis, Apostolaki, Doumas and Devetzi2021, Fig. 2). Another example from Akrotiri derives from a special context known as the ‘Sacrificial Complex’, found along with a concentration of EC artefacts (Doumas Reference Doumas, Brodie, Doole, Gavalas and Renfrew2008, 165–166) and thus considered as an EC assemblage. This is a metal tool that has preserved the fragment of a cloth in mineralized state on its surface (Papadima Reference Papadima2005, 81). Moreover, remains of a textile were traced on a metal pin dated to the EC period (Michaelidis and Angelidis Reference Michaelidis and Angelidis2006, 69).

Textile Tools and Production Facilities

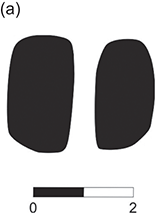

Textile tools dated to the beginning of the EBA are documented at the site of Poliochni on Lemnos. Large numbers of clay, well-shaped, often burnished but undecorated, biconical, and conical spindle whorls were found in deposits of the Blue period (Bernabò Brea Reference Bernabò Brea1964, 155) corresponding to the EB I horizon. The excavator also reported cylindrical, clay objects with one longitudinal perforation from the same period which, if interpreted as loomweights, may indicate the use of the warp-weighted loom (Bernabò Brea Reference Bernabò Brea1964, 658). Such cylindrical clay objects were also found at a contemporary site on the island of Thasos, in the north Aegean. A small settlement radiocarbon-dated to the early EBA was excavated at the bay of Ayios Ioannis, on the southeast coast of the island (Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Palli, Vakirtzi, Psathi, Dietz, Mavridis, Tankosić and Takaoğlu2018, 361–363). Nine perforated cylinders, manufactured in large sizes and weighing between 500 and 1000 gr, were found and have been identified as loomweights (Figure 13). Their thickness, ranging between 6 and 9 cm, likely suggests very open or weft-faced weaves, while their weight requires thick threads. The over thirty spindle whorls found at the site confirm local production of medium to thick threads: shaped predominantly in the discoid-lentoid type, the majority of the whorls weigh between 30 and 60 gr (Papadopoulos et al. Reference Papadopoulos, Palli, Vakirtzi, Psathi, Dietz, Mavridis, Tankosić and Takaoğlu2018, 361–363; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a). If Carington Smith was right in suggesting that cylindrical loomweights would have been used in sets of eight to ten (1975, 219), then the assemblage of Ayios Ioannis likely corresponds to a more or less complete weaving set for one loom.

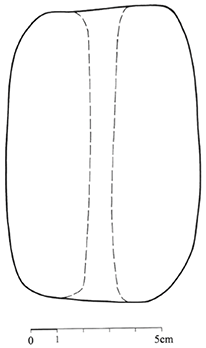

Figure 13 Cylindrical loomweight with one perforation from Ayios Ioannis, Thasos.

In the Cyclades, textile craft of the EC I period is documented through conical spindle whorls that are reported from the EC I sites of Avyssos and Pyrgos on the island of Paros (Rambach Reference Rambach2000, 196–197). At the settlement of Skarkos on the island of Ios, a few contexts attributed to the EC I period (Marthari Reference Marthari, Marthari, Renfrew and Boyd2017; Maniatis et al. Reference Maniatis, Marthari and Polymeris2023) yielded c. twenty clay spindle whorls that are noteworthy for their typological homogeneity. These are predominantly low conical spindle whorls, while just a few are discoid (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020). More than half of the overall whorl assemblage includes heavy tools, reaching up to 70 gr, indicating spinning (or plying) thick thread, as in EB I Thasos (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020).

During the EB II period, spindle whorls were manufactured and used in settlements spanning from the north Aegean (Skala Sotiros, Thasos), to the Eastern Aegean islands (Poliochni and Koukonisi on Lemnos, Emporio on Chios, Thermi on Lesbos) to the south (Heraion on Samos) clearly indicating the importance of yarn production in the respective communities (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020, with references). In the Cyclades, thread spinning or plying is attested in settlements including Ayia Irini on Kea (Wilson Reference Wilson1999), Markiani on Amorgos (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018) Dhaskalio (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Renfrew, Philianotou, Brodie, Gavalas and Boyd2013) and Skarkos on Ios where the spindle whorl assemblage now includes biconical and cylindrical types of whorls in addition to the low conical type of the preceding period (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a).

The spindle whorl assemblages of Ayia Irini, Markiani, and Skarkos demonstrate that thread production was not particularly standardized, as suggested by the range of whorl sizes comprising each assemblage. However, they all include tools that are lighter than 20 gr while the heaviest ones have a less pronounced representation (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi2015; Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020). This indicates a subtle shift in comparison to the EC/EB I period, with finer rather than coarse thread production at the core of the yarn industries. Among the smallest spindle whorls are those weighing up to 15 gr, found at Skala Sotiros on Thasos, Heraion on Samos, Ayia Irini on Keos, and Koukonisi on Lemnos (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020).

Another aspect of thread manufacture in EBA insular societies is highlighted by the fact that tools have sometimes been found in graves (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi2018b). It is noteworthy that some very small, clay whorls weighing between 3 and 10 gr were deposited as burial offerings in a grave at the EC cemetery of Aplomata on Naxos (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi2018b; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020). Tools of this size class can be used to produce extremely thin woollen and linen threads that can be then woven into cloth, as the CTR spinning experiments performed with wool and flax show (Möller-Wiering Reference Möller-Wiering, Strand and Nosch2015, 103–109). Metal needles that are part of the EC material culture, and were also deposited in tombs as burial offerings (Doumas Reference Doumas1977, 60; Rambach Reference Rambach2000, 172–173), occasionally in the same tomb with spindle whorls (Rambach Reference Rambach2000, Tafel 63), indicate sewing or embroidery. The smallest and lightest EBA whorls imply careful preparation of the fibres before the spinning stage, a process that requires a considerable amount of time (Andersson Strand 2015). Could the custom of depositing textile tools in graves provide insights to the gender of the islanders who spun thread and sewed? Unfortunately, preserved skeletal remains from the EBA Aegean are minimal. This does not allow us to reach any conclusions on the biological sex, let alone the gender of the people who were buried with spindles and whorls (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi2018b).

Distribution patterns of textile tools in the insular settlements indicate household production. Spinning toolkits that can be ascribed to a single household or production area usually include whorls of considerably different sizes, indicating a tendency to address the need for at least two distinct qualities of thread. Such a nuanced picture is provided by the excavator of the prehistoric settlement at the Heraion on the island of Samos, dated in the late third millennium BCE (Milojčić Reference Milojčić1961). In one case, a group of five spindle whorls was traced in the east part of the ‘Großes Haus’, and in a second case, a group of six spindle whorls was found in a clay vessel in the ‘Magazine’ building (Milojčić Reference Milojčić1961, 23–24, 51). When a sample of these tools was studied, it became clear that each of these small concentrations included spindle whorls of significantly different sizes, from very small to large (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a, 192) (Supplementary Figure 6). A preliminary distribution study of the tools found at Skarkos on Ios reveals a similar picture (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018a, 193).

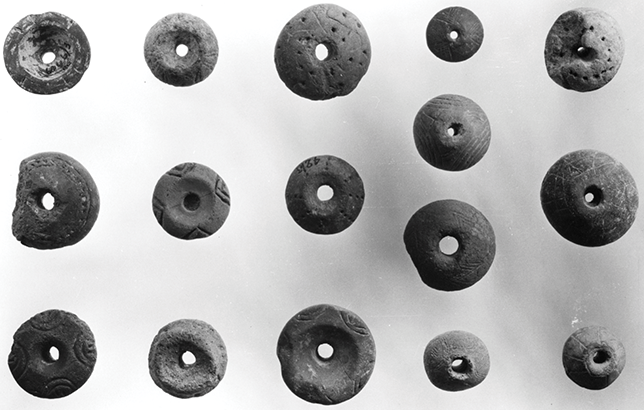

During the EB II period, a spindle whorl type with a hollow top (a concave configuration around the central perforation also known as ‘scodelletta’), often decorated with incised, geometric motifs, was used in the northeastern Aegean islands of Lemnos (Figure 14), Lesbos and Chios (Barber Reference Barber1991, 306–307; Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020). Examples of this type of whorl were also found in the Cyclades, at Dhaskalio and Markiani (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018), and in EC II cemeteries on Syros (Chalandriani) and Naxos (Aplomata) (Vakirtzi Reference Vakirtzi, Schier and Pollock2020). To date, however, no such whorls have been found at Skarkos on Ios, while they are rather rare in the EC II–III deposits of Ayia Irini on Kea (Wilson Reference Wilson1999). Barber (Reference Barber1991) surveyed parallels of this type of tool found in earlier sites, from central Asia and Anatolia, and in later sites in northern Italy and as far as Switzerland. She distinguished a gradual, centuries-long westward diffusion of the ‘scodelletta’ spindle whorl type, which she attributed to population mobility (Barber Reference Barber1991, 299–310).

Figure 14 Spindle whorls of the decorated, ‘scodelletta’ type from Poliochni, Lemnos.

Weaving on the warp-weighted loom in the EBA Aegean is indicated at a few insular sites of the northeast Aegean. One of those is Poliochni on Lemnos, where cylindrical weights are reported from the horizon of the Green and Red towns (EB II early) (Bernabò Brea Reference Bernabò Brea1964, 658, Pl. CLXVII: 9). Another one is Thermi on Lesbos, where discoid loomweights have been found (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith1975, 237). At Ayia Irini on Kea, in the Cyclades, weaving with the technology of the warp-weighted loom is also demonstrated through the recovery of clay loomweights (Wilson Reference Wilson1999, 160) that have been described as ‘Anatolian type’ tools (Davis Reference Davis, Hagg and Marinatos1984, 162). Stone weights of similar shape and size found in the same location, indeed in the same deposits (Davis Reference Davis, Hagg and Marinatos1984, 154–155), were probably also used as loomweights. It is possible that three similar stone weights found at the EC II-late site of Panormos on Naxos (Devetzi Reference Devetzi and Angelopoulou2014, 338–340), had had a loomweight use as well. These finds indicate the possible use of the warp-weighted loom in the Cyclades during the third millennium BCE, perhaps using stone loomweights. However, the most exhaustively excavated EC settlements to date, namely Markiani on Amorgos, Dhaskalio near Keros and Skarkos on Ios, did not yield either clay or stone loomweights of this type or any other identifiable type (Gavalas Reference Gavalas, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018; Marthari Reference Marthari, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018, 189–192). It is possible that in these settlements either warp-weighted looms were operated with weights made of perishable materials that have not survived in the archaeological deposits; or that loom types other than the warp-weighted were used, like the horizontal ground looms or other weaving devices.

The anatolianizing element identified in the loomweight types of Ayia Irini, Kea, and in the hollow, incised whorls of several insular settlements, with clear parallels in Anatolian sites (most notably in Troy, Balfanz Reference Balfanz1995) have long been highlighted (Carington Smith Reference Carington Smith1975; Davis Reference Davis, Hagg and Marinatos1984, 162; Barber Reference Barber1991). These types of textile tools suggest the integration of textile craftspeople in the regional networks that flourished in the Aegean from the EB II period onwards, and the nodal position of the insular communities in the trajectories that brought people into contact. Finished products of the loom would also have circulated from one place to another, at least as items of clothing worn by travellers. Textile craft, textile tools, and cloth items should therefore be viewed as significant elements of the EBA ‘International Spirit’ that was fostered by the insular Aegean communities in the third millennium BCE (Renfrew Reference Renfrew2017 [Reference Renfrew1972]).

3.1.2 The Mainland

Excavated Textile Imprints

A small, clay sealing found at Geraki, Laconia, in the southern Peloponnese, preserves the imprint of finely woven cloth (Weingarten Reference Weingarten and Müller2000). The context is dated to the EH IIB period, a time of increased connectivity in the Aegean. The imprint demonstrates a plain, faced weave structure (Table 2). Vogelsang-Eastwood (Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood1999) identified a possible selvedge and perhaps the starting border of the cloth, a feature indicating weaving on a warp-weighted loom. She also highlighted a structure identified as the interlacing of warps and wefts in one location, where ‘the crossing of several threads in both systems 1 and 2’ were observed (Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood1999, 372–373, Fig. 21). This find indicates the use of fine textiles in activities such as the sealing practices that resulted in the creation of the Geraki imprint (Weingarten Reference Weingarten and Müller2000). The sealings of Geraki were most probably created within the Peloponnese, and perhaps even at the site itself (Weingarten et al. Reference Weingarten, Crowel, Prent and Vogelsang-Eastwood1999, 368–370), so the cloth too was available in the location where the sealing process took place. Nonetheless, it is unknown where, or by whom, this finely woven textile was produced.

Textile Tools and Production Facilities

Textile craft in the EBA across the Greek Mainland is documented by spindle whorls and loomweights found at various sites. This material, first surveyed by Carington Smith (Reference Carington Smith1975, 196–260, passim), confirms that thread manufacture with spindle and whorl and weaving on the warp-weighted loom were widespread textile technologies. Their morphometric variability indicates diverse production targets, relating to both thread qualities and cloth types, observed across different sites as well as within each site. The general impression is one of accentuated regionality. Within this technological mosaic, Carington Smith has emphasized the hemispherical whorl and the cylindrical loomweight as the most commonly found tool types in the region (Smith Reference Carington Smith1975, 219). Besides these, the pyramidal and the spherical loomweight types also occur, while other types are rare (Smith Reference Carington Smith1975, 237–260).