Introduction

What causes political trust? Since at least the 1970s, understanding the causes and correlates of political trust has been a core endeavour of political science (for reviews, see Citrin & Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Carstens, Reference Carstens2023; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Zmerli & Hooghe, Reference Zmerli and Hooghe2011; Zmerli & van der Meer, Reference Zmerli and Meer2017). Despite this substantial scholarly endeavour, there is still little consensus on which factors have the largest, if any, causal effect.

In this paper, we contribute to this debate theoretically by building on a model of trust which positions competence, benevolence and integrity, what we call the ‘CBI’ model (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), as fundamental to driving trust judgements. This model has been widely adopted in fields such as public administration (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995) and the social psychology of candidate evaluations (Bor & Laustsen, Reference Bor and Laustsen2022; Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy and Glick2007; Laustsen & Bor, Reference Laustsen and Bor2017; McGraw, Reference McGraw, Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia2011) and is central to many philosophical debates on trust and trustworthiness (Jones, Reference Jones1996, Reference Jones2012; Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; O'Neill, Reference O'Neill2018), but has rarely been used in empirical studies of political trust (for exceptions, see Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Smidt and Mayer2019; Ouattara et al., Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023).

We contribute empirically to this literature by providing the first cross‐national, experimental study of the relative importance of competence, benevolence and integrity in shaping institutional trust judgements. We provide a causal test of the CBI model by leveraging conjoint experiments in five countries: Britain, Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France. The conjoint design allows us to understand and disentangle the causal effects of these attributes on trust judgements. Most substantially, it provides a benchmark of the relative importance of these trustworthiness features, such that we can say whether one is more important than the other, at least in the context of our experiment. We also go beyond standard practice in conjoint experiments by using relatively recent methods to estimate interaction effects between different attributes (Egami & Imai, Reference Egami and Imai2019) and how respondent characteristics (such as education and ideology) moderate the effects of the attributes (Robinson & Duch, Reference Robinson and Duch2024), shedding light on whether the preferred traits of government vary across the population.

To preview our empirical results, we show that our measure of benevolence – government being perceived as acting in the interest of citizens – is the strongest determinant of trust judgements, and that this is consistent across individuals and nations. Competence and integrity attributes are also important but secondary and have an approximately equal effect. In that respect, our findings are consistent with recent work on which candidate traits are generally preferred (Laustsen & Bor, Reference Laustsen and Bor2017) and the determinants of trustworthiness of hypothetical candidates (Ouattara et al., Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023). However, our study generalises those findings to the political institution of government and a cross‐national context. We also build on recent methodological advances in the analysis of conjoint data and show that benevolence importantly conditions the two other concepts, such that being competent is actually a negative when the government does not work in citizens' interests. Finally, we show that respondent‐level demographics do not importantly moderate the effects of these attributes, except in the case of left‐right ideology.

Our theoretical contribution, as noted, is to develop further the idea that the (perceived) trustworthiness of government consists of at least three distinct dimensions of considerations: their perceived CBI; in doing so, we make the necessary conceptual distinction between trust and trustworthiness with regard to political actors, which has been raised in the philosophical literature (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002; Levi, Reference Levi2022; O'Neill, Reference O'Neill2018). Our empirical contribution is perhaps the most substantial, providing the first experimental test of this model for trust in government, and doing so across five countries and two continents, identifying which aspects of trustworthiness are most consequential for trust judgements and how those aspects interact with each other. By showing which aspects of trustworthiness are (most) relevant, we further the systematic study of alternative explanations of political trust.

Our paper proceeds by defining and conceptually distinguishing trust and trustworthiness and then motivating our theoretical argument that the latter is primarily composed of competence, benevolence and integrity. We then describe how we test this conjecture, including how we operationalise the three concepts. We present our data and results sequentially in two studies: the first conducted in Britain and the second in Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France. We conclude with a discussion on the results and the broader contribution.

Trust and trustworthiness

The concept of ‘political trust’ has been defined broadly as people's basic evaluative and affective orientation to the institutions and actors governing their polity (Citrin & Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Miller, Reference Miller1974); we build on that definition but define it more specifically as the belief that an actor or institution (the object of trust) would produce preferred outcomes even if left unattended (Easton, Reference Easton1975). We also consider trust to be both dispositional and relational. First, it is dispositional in that people can have varying degrees of a general, underlying disposition to trust – regardless of context and the object of trust. In this perspective, the important issue is the subject's own propensity to trust: whether ‘A trusts’ (Uslaner, Reference Uslaner and Uslaner2018, pp. 3–13). This work builds on a long tradition which argues that trust, or a trusting disposition, is at least in part socialised and stable over the lifetime and has less to do with the objects of trust (e.g. Devine & Valgarðsson, Reference Devine and Valgarðsson2024; Easton, Reference Easton1975). In this perspective, relevant explanatory variables are primarily at the level of the subject.

We also consider trust to be relational: while people likely have a general disposition where they generally tend to trust or not to trust, the specifics of the context, domain and object of trust are also likely to shape their trust judgement (varying by person) in each case: ‘A trusts B to do X’ (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002). Whilst this necessitates that trust is partially domain‐specific (you might trust a government on the economy, but not on healthcare provision), we do also contend that people can have a general sense of trust in a particular object, which is based both on their general trust disposition and on a general assessment of that object's trustworthiness, which may be based on a (weighted) average of their trust in that object across all relevant domains. For instance, one may generally trust a government because it is thought to be trustworthy in multiple areas or because it is trustworthy in a domain that one considers very important. Finally, when we talk about ‘political trust’ we are simply talking about trust that is directed at political objects of trust. Here, we take it to refer to attitudes towards the explicitly political branches of the state in most established and developing democracies: parties, elected leaders, parliament and the national government. In this paper, we focus on trust in government: the extent to which our results generalise to other political institutions depends both on how related these political institutions are in people's mind and how dominant the dispositional aspect of trust is for each person, but prior studies suggest that people's trust in different representative institutions is strongly associated (Marien, Reference Marien, Hooghe and Zmerli2011).

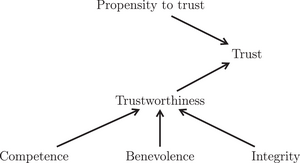

Thus, we believe that trust is based both on people's general propensity to trust and on the (objective and perceived) trustworthiness of the particular object of trust in question. Our focus here is on the role that different aspects of the (perceived) trustworthiness of objects play in shaping people's trust judgements, but we will also explore how these interact with respondent attributes that shape their general propensity to trust. Regardless, we believe that conceptually separating the two (that is, the propensity to trust and trustworthiness) is important for any study of the drivers of trust: this is a distinction widely adopted in the philosophical literature (Hardin, Reference Hardin1996, Reference Hardin2002; Levi and Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; O'Neill, Reference O'Neill2018), but somewhat neglected in the empirical political science literature. Figure 1 presents this conceptual framework, also integrating three dimensions of trustworthiness that we will discuss in the next section: competence, benevolence and integrity.

Figure 1. Propensity to trust and trustworthiness as causes of trust judgements.

Trustworthiness as competence, benevolence and integrity

We theorise that people's perceptions of the trustworthiness of particular objects are primarily shaped by their perception of three types of attributes: the object's CBI. Competence is about whether government (or another object of trust) has the ability to govern in any given policy domain, which is usually but not only signalled through policy outcomes (such as increasing wealth, decreasing unemployment and so on). Given that there are almost limitless domains that a government could claim competence on, and no one can plausibly judge all of these, citizens typically judge competence (i) with respect to a domain that is particularly salient to them or society or (ii) by averaging over a range of considerations of salient domains (Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2017; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). The role of perceived competence in shaping political trust has been the focus of many previous studies, usually but not only measured through (economic) policy performance (van der Meer, Reference Meer2018; van Erkel & van der Meer, Reference Erkel and Meer2016). Moreover, it is central to almost all philosophical or theoretical accounts of trustworthiness (Jones, Reference Jones1996, Reference Jones2012; Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; O'Neill, Reference O'Neill2018).

Benevolence is another attribute central to philosophical accounts of trustworthiness (e.g. Baier, Reference Baier1986). Jones (Reference Jones1996, pp. 6–7) goes as far as to say that ‘the incompetent deserve our trust almost as little as the malicious.’ And benevolence refers to this maliciousness – or lack of it. Specifically, benevolence refers to perceptions of the governments' motivations, that there is a ‘perception of a positive orientation of the trustee towards the trustor’ (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995) and that they want to do good, regardless of other exogenous motivations. Levi and Stoker (Reference Levi and Stoker2000) suggest benevolence is often the only attribute people mean by trustworthiness. Thus, it is central to trustworthiness claims. In the literature on candidate evaluations, this is commonly referred to as warmth rather than benevolence (Laustsen & Bor, Reference Laustsen and Bor2017), but these terms refer to broadly the same dimension of qualities: that the object of trust is perceived to ‘care’ about the subject and want to act in their interest. Some philosophical treatments of trust speak more of ‘motivation’ than of ‘benevolence’ but note that the object of trust is ‘motivated to do’ what they are trusted to do, which is similar to our (and others) definition of benevolence (De Fine Licht & Brülde, Reference De Fine Licht and Brülde2021). The concept has also been used in a study of trust in municipal government (Grimmelikhuijsen & Knies, Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017) and a recent study of trust in politicians (Ouattara et al., Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023), but is still largely overlooked in the empirical political science literature, in particular when it comes to trust in institutions.

Finally, integrity refers to whether the trusted is open, honest and likely to be consistent in their behaviour and is often associated with subscribing to laudable moral convictions. If a government has clear and acceptable principles, sticks to them in its behaviour and is honest, then it would be judged to have integrity. In the political sphere, the importance of integrity has been highlighted both when it comes to the personal integrity of individual politicians in government (e.g., Allen & Birch, Reference Allen and Birch2015; Birch & Allen, Reference Birch and Allen2010; Stoker, Reference Stoker2006) and when it comes to the capacity of institutions to uphold integrity and ethical standards in government functions and procedures (e.g., Grimes, Reference Grimes2006). Previous studies have demonstrated a robust association between (perceptions of) procedural fairness or corruption and political trust (Van de Walle & Migchelbrink, Reference Van de Walle and Migchelbrink2020; van der Meer & Hakhverdian, Reference Meer and Hakhverdian2017), but it has so far rarely been demonstrated experimentally or compared systematically with the role of competence and benevolence (for a recent exception, see Ouattara et al., Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023).

What about the relative importance of these attributes? Given the lack of prior empirical research which we aim to address – that is, testing the relative importance of these attributes in shaping trust judgements – we can only speculate on which of these attributes is most relevant. Our theoretical understanding of political trust and how these judgements are formed provide us with some guidance. We have defined political trust as a belief that the government would produce preferred outcomes even if left unattended. It makes perfect sense, given this definition, that this belief would be shaped by the perception of government's ability to do good (competence), actual willingness to do so (benevolence), and its consistency and honesty in carrying out that intention (integrity). It also makes sense, as Levi and Stoker (Reference Levi and Stoker2000) argue, that a trust object's perceived motivations – benevolence – drive most directly at what we mean by trustworthiness: if someone's intentions are good, we may be more willing to forgive lapses of ability or consistency than vice versa (this also implies a potential conditional relationship between benevolence and other attributes).

This is not, however, without challenge. Some, particularly in the philosophy of trust, contend that it makes no sense to speak of trust in government (or other such organisations and groups): we cannot plausibly know the interests, intentions or ‘positive orientation’ of an institution (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002), nor can we feel legitimately betrayed by an institution (Hawley, Reference Hawley2017) (for a counter‐argument, see Bennett, Reference Bennett2024). Aside from undermining the study of institutional trust generally, this specifically takes aim at benevolence: it makes no sense to talk of ‘government motivations’ or ‘positive orientations’, as people cannot plausibly know these, even if institutions were to hold them. These objections have parallels in the political science literature, much of which builds on the ‘evaluative’ or rational model of trust, in which people evaluate performance (van der Meer & Hakhverdian, Reference Meer and Hakhverdian2017), which lends itself more to competence and integrity evaluations than to perceptions of benevolence. Instead, a ‘social model’ of trust in institutions emphasises the importance of benevolence beliefs, in which people are influenced by the attributions of motives of authorities (Tyler & Degoey, Reference Tyler, Degoey, Kramer and Tyler1996).

All told, the theoretical and philosophical literature offers diverging expectations about the relative importance (if any) of perceptions of CBI for trust judgements. In this study, we set out to empirically test those diverging expectations.

There are few empirical tests of the CBI model as an explanation of political trust. Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies (Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017) provide a cross‐sectional validation of CBI items, using two convenience samples of university students and the population of a municipal government in the Netherlands; similarly, Hamm et al. (Reference Hamm, Smidt and Mayer2019) test the CBI model using an MTurk convenience sample in the United States, asking about the federal government. The closest test to ours is Ouattara et al. (Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023), which presents a factorial experiment randomising traits of trustworthiness, including (but not limited to) competence, benevolence and integrity, in the Netherlands. They find that benevolence is the strongest predictor of trust, followed by integrity and competence (the latter of which they call ‘ability'). There are also some parallels between the concept of benevolence and that of ‘warmth’ in leader and candidate evaluation studies (e.g., Laustsen & Bor, Reference Laustsen and Bor2017), which find that ‘warmth’ is the most important trait in political leaders in the United States.

We add substantially to these empirical contributions. First, we extend the test of the CBI model from politicians to the institution of government. As discussed above, it is not clear whether benevolence attributes should extend beyond personal trust (such as leaders and candidates) to (more) impersonal institutions like government; some would claim that this is implausible. Second, empirically, we extend the study of the CBI model to a cross‐national sample, covering five countries. Third, we explore heterogeneous effects by respondent characteristics and interactions between attributes. Collectively, these deepen our knowledge of, and confidence in, the CBI model's generalisability.

Testing the CBI model of trustworthiness

We test the CBI model through two different forced‐choice, non‐registered conjoint experiments, encompassing five countries from two continents. In the first, we fielded an extensive conjoint in the British Election Study (BES) in May 2020 which we matched with the extensive respondent‐level data (e.g., education and income) in the same wave of the BES. Building on these results, we fielded an updated version of the conjoint in four countries: Croatia (Central Europe), Spain (Southern Europe), Argentina (South America) and France (Western Europe), with fieldwork dates ranging from September to November 2021.Footnote 1 All samples are nationally representative. In total, our sample consists of 11,930 unique individuals with nearly 30,000 separate responses; fieldwork details, including dates, survey company and sample size, are available in Online Appendix A.3.Footnote 2 The forced choice conjoint design is now commonly used for questions such as ours in which the interest is in jointly estimating the (causal) effect of numerous variables which may jointly affect a respondent's judgement.

In all iterations of the survey, the preamble was identical and translated by native speakers (see Online Appendix A for wording). Both asked respondents to choose between two side‐by‐side profiles (‘Government A’ and ‘Government B')Footnote 3 on which government they ‘would tend to trust more’.Footnote 4 The order of attributes and values was randomised between respondents but not within: respondents saw different attribute orders, but this was kept consistent throughout their iterations. This was a way of overcoming order effects whilst reducing respondent effort.

In addition to our measures of CBI which we describe below, we also include measures of tenure length, ideology, policy priority and public approval in all of the choice sets. We do this for a number of reasons. First, these have been shown to be relevant for judging government competence in previous conjoint experiments (Johns & Kölln, Reference Johns and Kölln2020). Second, we wanted to make the choice set more realistic; tenure, ideology, policy priorities and public approval are readily available heuristics to citizens in the real world, and we felt it was important for respondents to have a plausible set of factors to derive their trust judgements.

In our primary results below, our method of analyses is based on marginal means. Marginal means can be equivalent in interpretation to the more common average marginal component effects but do not rely on a base category and also reveal subgroup preferences where relevant (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). In all cases, we cluster our standard errors for each individual, since each individual makes multiple comparisons. We then turn our attention to the interaction of our attributes with each other and with respondent characteristics. For the former, we use Average Marginal Interaction Effects (AMIEs) (Egami and Imai, Reference Egami and Imai2019) and for the latter we explore which respondent‐level characteristics explain the heterogeneity in attribute effects (Robinson & Duch, Reference Robinson and Duch2024).

Operationalising CBI

To test the effect of CBI on trust judgements, we developed a set of indicators for the three concepts, which builds on other efforts to do so in public administration (Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies, Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017). As those authors note, trust measures need to be adapted to their contexts, so we follow their validated measures closely whilst modifying it to apply better to the citizen–government relationship. For competence – the ability of the object of trust to carry out its tasks – our primary measure is simply varying the stated level of ‘competence’ that a government has. In the first study, we include a second measure of competence, stating whether a government ‘carries out its duties poorly’ or ‘well’. To measure benevolence – referring to the motivations of the trusted – we state that the government would usually ‘act in the interests of citizens’, a ‘majority of citizens’, ‘some citizens’ or ‘in its own interests’. Our intention here is to indicate whether the government is motivated by serving the interests and well‐being of its citizens (rather than its own). In the first study, we also measure this by whether the government ‘wants to do its best to serve the country’ or not. Finally, for integrity – which is whether the trusted is open, honest and likely to be consistent in its application – we primarily measure this in terms of transparency. We do so since we believe this addresses the openness and honesty dimension. In the first study, we also measure this using whether the government is ‘corrupt’ or free from corruption; we went to why we exclude this and others for the second set of countries.

Clearly, all of the dimensions that we have highlighted could be measured in a number of ways that emphasise different aspects of the concepts; we do not claim that our study is an exhaustive exploration of the potential drivers of political trust or all sub‐dimensions of the CBI framework. However, our trade‐off is that adding more attributes increases respondent effort, and so we follow previously validated measures of the concepts (Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies, Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017; Hamm et al., Reference Hamm, Smidt and Mayer2019). Where we include two measures of the same concept, they perform almost identically, which suggests to us that we are capturing the same concept.

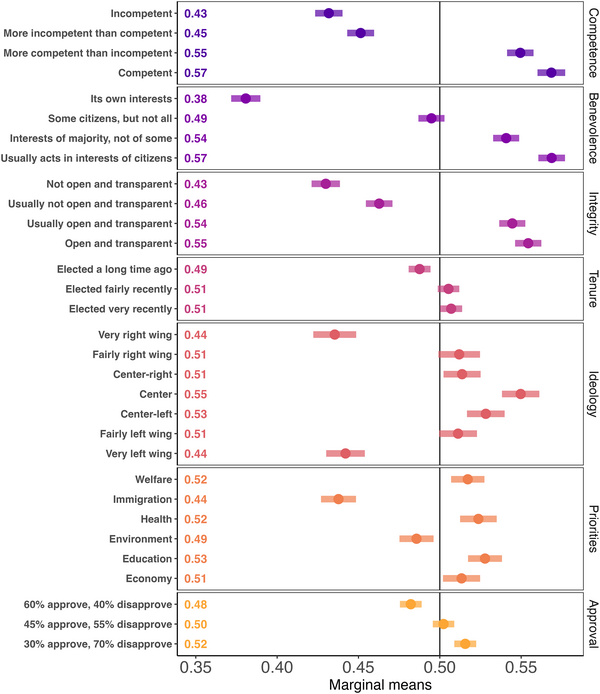

The attributes, levels and study they are used in are presented in Table 1. As implied above, some of the attributes appear in both studies (Competence I, Benevolence I, Integrity I), whilst the others are only in the first study: this is because the effects were essentially identical in the first study, and so we reduced the number of attributes to reduce respondent effort. Regarding corruption levels (integrity I), we considered that we could not be sure what dimension this was tapping. Corruption could well signal a lack of integrity, benevolence or even competence. As such, we excluded it from the larger survey.

Table 1. Attributes and attribute levels

We present our results beginning with the conjoint fielded in Britain then the experiments fielded in Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France, before exploring attribute–attribute and attribute–respondent interactions.

Evidence

Study 1: Evidence from Britain

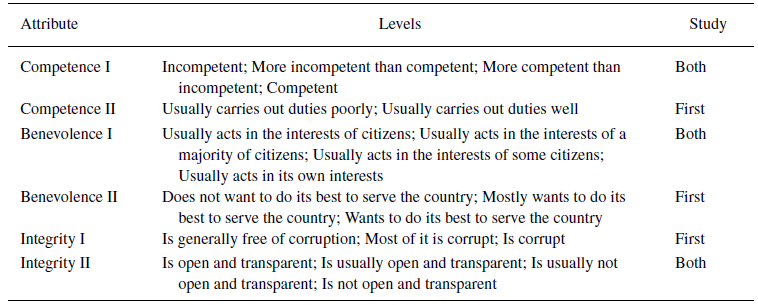

The marginal means from the conjoint are presented in Figure 2. On the right side, the feature labels indicate the overall attribute, with the levels on the left. The plot also includes coefficient labels to provide easy comparison. Of the three concepts of CBI, corruption has by far the largest effect; averaging over all other attributes, a corrupt government has a preferred profile 40 per cent of the time, whilst a government ‘generally free’ has a preferred profile 64 per cent of the time. Benevolence and competence have similar effects; governments that act in their own interests and do not want to do their best to serve the country have marginal means of 0.42, whilst the opposite of the scale have marginal means of 0.55. Incompetent governments have a marginal mean of 0.43, compared to 0.56 for competent governments (competence II is 0.45 compared to 0.55). Of our primary attributes of interest, transparency has the weaker effects, with a 10 per cent‐point difference between those governments not transparent (45 per cent) and those that are transparent (55 per cent).

Figure 2. Marginal means testing the CBI model in Britain. Point estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals visualised.

Three of the four government attributes – tenure, priorities and approval – have relatively small effects on government trustworthiness. Tenure is essentially unrelated, with a small penalty for governments with a long tenure. Likewise, policy priorities have similarly small effects. Government approval has effects similar to transparency (integrity II), ranging from a marginal mean of 46 per cent for governments with 70 per cent disapproval to 54 per cent for a government with 60 per cent approval. Ideological extremism, however, has a rather larger effect, which is consistent with previous evidence (Johns & Kölln, Reference Johns and Kölln2020). Very right‐ or left‐wing governments have a marginal mean of 43 per cent and 47 per cent respectively, whilst centre governments have a marginal mean of 56 per cent (and 53 per cent for centre‐right and centre‐left governments).

Altogether, these results indicate that competence, benevolence and integrity have substantial effects on government trust in Britain; of these, integrity is the most important, followed by benevolence and then competence. These compare favourably to other important government attributes, whilst ideology also influences preferences to a similar magnitude as CBI, perhaps because of its importance in acting as a cue for other attributes like competence (Johns & Kölln, Reference Johns and Kölln2020). As we explore next, respondent ideology does indeed moderate the importance of our attributes, and in particular competence.

Study 2: Evidence from Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France

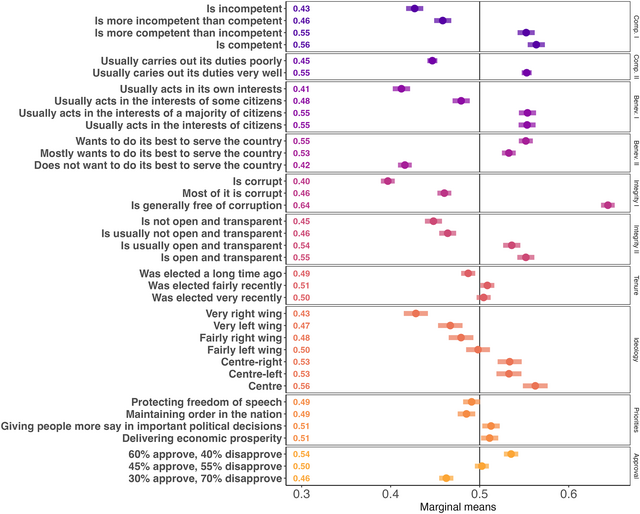

Does the CBI model extend outside of Britain? Do citizens of different countries value different traits of government trustworthiness? We start by presenting the countries – Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France – pooled together in Figure 3, which follows Figure 2. Benevolence has the largest effect on trust out of the three core concepts – governments which are seen as looking after their own interests have a marginal mean of 0.38; those acting in the interests of citizens have a marginal mean of 0.57. Integrity and competence have similar effects. Those governments that are not open and transparent or are incompetent have a marginal mean of 0.43, compared to 0.55 for those that are transparent and 0.57 for those that are competent. Tenure has similarly minimal effects as in Britain, with long‐tenured governments slightly less preferred; government approval also has similar effects. Our slightly adjusted policy priorities do show that a focus on immigration is substantially less preferred, and education more preferred, though others have minimal effects. Finally, our strong results for government ideology, in which extreme governments on right or left are much less preferred, are also replicated to almost an identical marginal means (profiles selected 44 per cent of the time in these countries versus 43 per cent in Britain).

Figure 3. Marginal means testing the CBI model in Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France. Point estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals visualised.

Collectively, what these results show is that benevolence is the strongest predictor, followed by integrity and competence to very similar levels. Government ideology is similarly related to trustworthiness, whilst tenure, approval and to a lesser extent policy priorities, do not largely determine perceived trustworthiness. Unsurprisingly, there are significant country differences (an analysis of variance test indicates significant differences at

![]() $p > 0.001$). We separate the results by country in Figure 4.

$p > 0.001$). We separate the results by country in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Marginal means testing the CBI model in Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France, separated by country. Point estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals visualised.

We find similar results for competence across countries. Argentinian respondents are slightly less likely to reward competence and punish incompetence than the three European countries, and significantly so compared to Croatian respondents. There are substantial differences for benevolence, with Spanish and Croatian respondents preferring governments that look after their own interests substantially less than in Argentina and France. Integrity is viewed similarly across the four countries. There are substantial differences in preferences over ideology. Spanish respondents respond extremely negatively to very right‐wing governments, whilst in Argentina preferences are about even across the ideological spectrum; Argentinian respondents are also the only country sample to dislike rather than prefer ‘fairly left‐wing’ governments. Spanish and French respondents are also more likely to prefer centre governments compared to Croatian or Argentinian respondents, and Spanish respondents prefer centre‐left governments the most.

Altogether, our results indicate that competence, benevolence and integrity are powerfully related to perceived government trustworthiness cross‐nationally and to similar degrees. Integrity and competence are related almost identically in the five countries. Benevolence (specifically a government looking after its own interests) has a larger effect size in Croatia and Spain than in Argentina and France.Footnote 5

Attribute–attribute and respondent–attribute interactions

We turn to exploring heterogeneity in the attribute effects in terms of interactions between the conjoint attributes and how respondent‐level variables moderate the effect heterogeneity of the attributes. We pool our four countries used in Study 2 and exclude Britain due to the different attributes used.

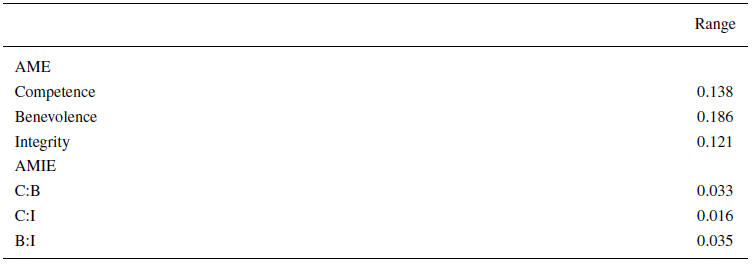

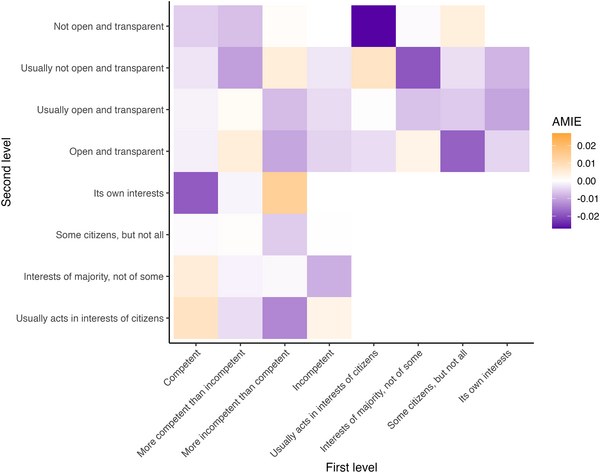

It may be the case that combinations of attributes have a greater combined effect than their independent effects. We are interested here only in our core attributes of CBI. We test for this by estimating AMIEs of all two‐way attribute–attribute interactions and the average marginal effect (AMEs) for each attribute (Egami and Imai, Reference Egami and Imai2019). Following Egami and Imai (Reference Egami and Imai2019), we first screen all interactions for significance; in this case, all our two‐way interactions of the three attributes are significant. To be explicit, this means that {Competence, Benevolence}, {Competence, Integrity}, {Benevolence, Integrity}, all significantly interact. We present the range of AMEs and AMIEs in Table 2. Important to note is that the effect sizes here are not sensitive to the baseline category. What these show, consistent with our previous results, is that benevolence has a larger effect than the other two attributes, with an AME of 4.8 percentage points larger than competence and 6.5 percentage points larger than integrity. Of primary interest are the interactions, which show that the interactions including benevolence have larger effects than the C:I (competence: integrity) interaction. The size of these interactions is not trivial; the AMIE is three percentage points for the two interactions including benevolence, which equates to 6 per cent of the overall effect of benevolence (18.6 percentage points).

Table 2. Range of AMEs and AMIEs of core attributes

We visualise the AMIE of each level interaction in Figure 5, with the orange‐purple spectrum representing positive‐negative AMIEs. We focus on the interaction between benevolence and competence. Here, we find that the interaction between a government ‘acting in its own interests’ and being ‘competent’ is negative: when a government is competent but not working in the interests of citizens, this actually imposes a penalty on trust judgements. This makes sense: citizens penalise a government that is competent but self‐serving. Likewise, we find the symmetrical effect of being competent but benevolent, which is rewarded.

Figure 5. Average marginal interaction effects (AMIEs) of core attributes.

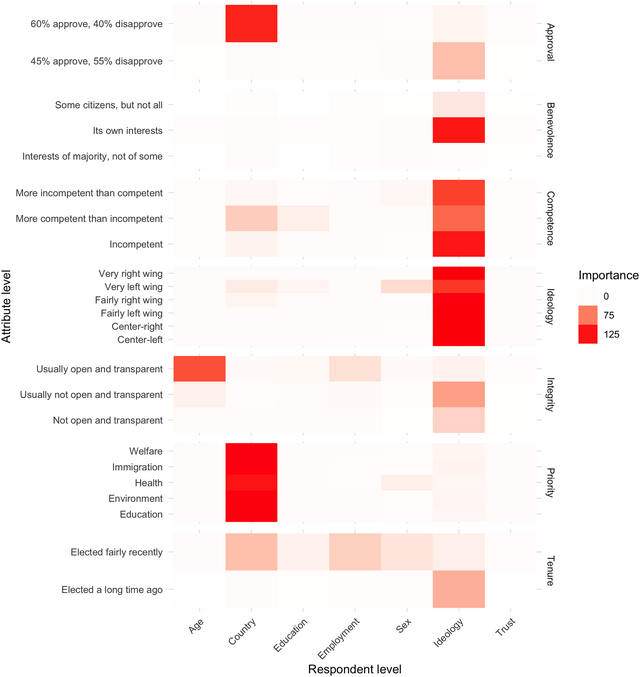

Figure 6. Variable importance matrix from separate random forest models on each attribute‐level for attribute–respondent interactions.

We now turn to exploring respondent–attribute interactions. Specifically, we ask whether respondent‐level variables explain heterogeneity in the effects of our conjoint attributes. Again, we include four countries (excluding Britain) but include all attributes. As Robinson and Duch (Reference Robinson and Duch2024) argue, marginal effects (may) mask substantial variation in the effects of the conjoint attributes. Researchers have typically explored variation in conjoint attribute effects by some partitioning of respondents into binary categories, such as those with or without university education, or over or below a certain age, and comparing some estimates. However, this is not ideal, as this requires us specifying some variables of interest and also creating some cut‐off, amongst other statistical issues (Robinson and Duch, Reference Robinson and Duch2024). Here, we adopt the approach of Robinson and Duch (Reference Robinson and Duch2024) and use Bayesian additive regression trees to estimate a treatment effect for each individual (the individual‐level marginal effect), and then estimate a random forest of variable importance to understand which respondent‐level characteristics predict heterogeneity in the effects of the covariates. (See Robinson and Duch, Reference Robinson and Duch2024, for more details.)

We present these results in Figure 6. Along the X axis are the respondent‐level characteristics we include age, country of fieldwork, education, employment, sex, left‐right ideology and trust; on the Y axis are the conjoint attribute levels. Of all of our individual‐level variables, only ideology is consistently important in explaining the effects of the attributes, most obviously (and strongly) for the ideology of the government but also for the CBI measures. Unsurprisingly, we find that the country of fieldwork is important in determining the effect of issue priorities, but does not play a role in moderating the effect sizes of our core measures of trustworthiness. Aside from ideology, we only find that a respondent's age importantly moderates the effects of integrity, specifically being open and transparent. It may have been expected that people of different educational or employment levels may value different attributes of trustworthiness, but we find little evidence for this in this analysis.

We would like to highlight two conclusions from our exploration of the heterogeneity of the effects of our core attributes. First, we confirm again the potency of the benevolence of governments, with much larger average marginal effects than for the two other concepts, and larger attribute–attribute interactions when benevolence is included. Our visualisation of the AMIEs shows that when a government is not considered benevolent, competence actually imposes a penalty (and an opposite, symmetrical effect for when a government is considered benevolent). Second, we do not find that common individual‐level variables moderate the effects of our core attributes, except for left‐right ideology, which explains heterogeneity in the effect of competence and for one level of benevolence.

Discussion

What are the qualities of governments that lead citizens to trust them? What dimensions of trustworthiness are most important in determining political trust judgements? Despite decades of excellent cross‐national research, experimental investigations of these questions have thus far been lacking. We address this through a framework which posits that competence, benevolence and integrity are fundamental to trustworthiness, building on earlier work in public administration (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), and recent empirical studies of trust in politicians (Ouattara et al., Reference Ouattara, Steenvoorden and Van Der Meer2023) and local government (Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies, Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017). Theoretically, we develop the application of the CBI framework to the political context, highlighting how it speaks to the role of object trustworthiness (as opposed to the truster's propensity to trust) and leads logically from a definition of trust as the belief that the object would produce preferred outcomes even if left untended. Empirically, we fielded conjoint experiments in five distinct countries – Britain, Croatia, Spain, Argentina and France – to test which of these aspects of trustworthiness was most important for shaping trust judgements. The results point to benevolence – perceptions of government motivations – having the largest effect, with competence and integrity about equal and closely behind.

Whilst the patterns are consistent cross‐nationally, we find statistically significant heterogeneity between countries, with benevolence having a substantially larger effect in Spain and Croatia than in France and Argentina. Exploring attribute–attribute interactions, we find some significant interactions, such that a government that is seen as not benevolent but competent is less trusted. Whilst the effect size of these interactions is substantively small, they are not trivial and point to the important conditioning effect of benevolence. Exploring individual‐level heterogeneity, we show that respondents’ left‐right ideology consistently conditions the effect size of our core attributes, particularly the importance of competence, which is less relevant for those on the right of the political spectrum. In terms of other attributes, we find that the left‐right ideology of governments is a strong predictor of trust judgements, with extreme governments penalised more than centrist governments, except in the case of Argentina.

This opens new avenues for research on political trust. Most importantly, it allows us to understand how existing explanatory variables of interest – such as inequality (Goubin & Hooghe, Reference Goubin and Hooghe2020), scandals (Bowler & Karp, Reference Bowler and Karp2004), policy performance (van der Meer, Reference Meer2010; van der Meer & Hakhverdian, Reference Meer and Hakhverdian2017) and public service experience (Kumlin & Haugsgjerd, Reference Kumlin and Haugsgjerd2017) – are most likely to affect the trustworthiness aspect of trust judgements. Our results tentatively suggest that those variables which cause changes in perceived benevolence of governments will have larger effects than those that do not and that this is true cross‐nationally. This indicates that a lack of trust may well reflect less a judgement about whether governments are competent or moral – people might reasonably expect failures on both fronts – and more about whether they are genuinely trying to act in the interests of citizens.

This also helps us understand how to improve trust levels. Given the evidence that trust is important for a variety of outcomes, including vote choice and policy preferences (e.g., Devine, Reference Devine2024), it is generally desirable to have (appropriately) high trust. Existing research has not been well‐equipped to propose solutions. Our framework and results suggest that the most effective way to increase trust might be to enhance the perception (and reality) that governments truly have the best interests of citizens at heart, even if they do not always manage to achieve their objectives (perhaps through lack of competence).

One of the main objectives of our study has been to investigate the relative importance of these three core dimensions of trustworthiness for shaping trust judgements when it comes to the national government. As such, an important limitation is that it is difficult to precisely pinpoint the meaning and multi‐faceted content of each of these dimensions in a survey experiment. The content of the concepts of benevolence and integrity has been much debated in the literature; while we could have simply told our respondents that the hypothetical government ‘has integrity’ (as we did with competence, the most straightforward of the three dimensions) this would have invited the same sort of difficulties of interpretation that we began with: what do respondents think when they read that word? Therefore, we followed previously validated measures (Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies, Reference Grimmelikhuijsen and Knies2017) as closely as was feasible, but we acknowledge that other operationalisations might be valid and some respondents (and readers) might interpret the attributes in different ways. For instance, we believe that the phrasing ‘acting in citizens’ interest’ refers specifically to motivations and that one can act in another's interests either competently or incompetently (and our first study indicated that this attribute had an affect that was identical to the other benevolence attribute), but some respondents may also have been thinking of competence or integrity when reading that attribute. Similarly, we measure integrity as transparency, but the concept also refers to other aspects – such as honesty, impartiality and even moral convictions – that might have resulted in a stronger effect. Future research would do well to include other aspects of these three dimensions than we were able to measure here to further the comparison of their relative importance.

Whilst we have built on a long‐standing model of trust and trustworthiness, we would also like to highlight that there are alternative theoretical accounts which lead to alternative empirical tests. For example, some do not consider ‘benevolence’ or ‘integrity’ relevant to trust and trustworthiness (De Fine Licht & Brülde, Reference De Fine Licht and Brülde2021; Rydén et al., Reference Rydén, De Fine Licht, Rönnerstrand, Harring, Brülde and Jagers2024).Footnote 6 Others do not believe trust can be ‘two‐part’ (i.e., to ‘trust government') but must be ‘three‐part’ (i.e., to ‘trust government to do X') (Baier, Reference Baier1986; Faulkner & Simpson, Reference Faulkner and Simpson2017). It is worth noting again that some do not believe that trust in institutions, as we have studied here, makes sense at all (Hardin, Reference Hardin2002). We have also sidelined political distrust (as distinct from trust) (Bertsou, Reference Bertsou2019) and mistrust (Lenard, Reference Lenard2008). Other examples abound. We make this point to be explicit that the conceptual background of political trust (worthiness) is very rich, and we do not claim to have the final word on it.

Another limitation is that we are working with hypothetical governments. In the real world, individuals will not perceive these government qualities (entirely) objectively. Our intention in this paper has been to test and demonstrate the importance of trust objects’ CBI for trust judgements and to establish benchmark effect sizes, particularly which of these are most important. Future work should understand these dynamics further, whether these results hold up to different operationalisations, and what the importance of other aspects of CBI might be. It should also examine how people develop differing perceptions of these different dimensions of trustworthiness: for example, does economic performance primarily operate through perceptions of competence? Is the link between trust and vote intention primarily due to benevolence perceptions, and how does this vary across contexts and individuals? A step towards this might be to field survey items which measure these three dimensions and study how they are related to potential causes of trust (such as economic performance). In this paper, we have laid the groundwork for this future research agenda.

Data availability statement

Full replication code and data are available from Devine, Daniel (2024), “Replication Data for: ‘The causes of perceived government trustworthiness’, European Journal of Political Research”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KFDG0H, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been presented several times, including at a seminar at King's College London, the European Political Science Association, and the American Political Science Association. We appreciate the feedback from these audiences.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Survey details for four countries

Figure A1: Task effects for the pooled analysis. Note that Task 6 is only in France.

Figure A2: Task effects for the by‐country analysis. Note that Task 6 is only in France.

Figure A3: Profile effects for the pooled analysis

Figure A4: Profile effects for the by‐country analysis

Figure A5: IMCEs of benevolence values over respondent ideology, derived from Bayesian Additive Regression Trees

Figure A6: IMCEs of competence values over respondent ideology, derived from Bayesian Additive Regression Trees

Table A2: Marginal means from Figure 4

Table A3: Marginal means from Figure 3

Table A4: Marginal means from Figure 2