Management Implications

Our study provides important insights into control strategies for Bromus inermis (smooth bromegrass). Previous studies suggested that defoliation in the elongation stage would provide maximum reduction in outgrowth and persistence. Instead, we found that defoliating B. inermis twice in the vegetative stage minimized the number of tillers and rhizomes produced over the season or remaining alive into the fall compared with undefoliated B. inermis tillers or those defoliated in the reproductive stage (R). Therefore, managers wishing to reduce B. inermis abundance should avoid defoliation during the reproductive stage (R) and instead try to increase defoliation opportunities in the vegetative stage (V2). However, B. inermis has a large amount of meristematic potential available for future productivity regardless of defoliation treatment, which is a concern for control efforts, as axillary bud dynamics are closely tied to aboveground tiller dynamics. This large meristematic potential suggests multiple years of defoliation may be needed to reduce the abundance of B. inermis on these pastures.

We looked at the impact of defoliation timing on a single tiller and did not include the potential impacts on daughter tillers produced via rhizome. An earlier study found that nearly 50% of new tillers may occur from rhizomes, which may indicate that treatment impacts on a single tiller could differ from the effect of a treatment on a population of tillers. Also, because of the destructive harvest for evaluation of axillary buds, different parent tillers were defoliated each year. Repeated application of a particular defoliation treatment over time may change the persistence of B. inermis. Other variables affecting treatment response were not studied, including selective herbivory, plant community composition, or other factors. Even so, this field-based study provides needed information for designing future grazing studies looking at the effect of defoliation timing on B. inermis.

Introduction

Smooth bromegrass (Bromus inermis Leyss.) is an introduced, perennial, cool-season invasive grass that was planted to stabilize cultivated soils in the western United States (Vogel and Werner, Reference Vogel and Werner2004). Bromus inermis is often used for pasture in the midwestern and north-central United States because of its ability to survive drought, excellent winter hardiness, and good yield potential (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Moore, Moser, Moser, Buxton and Casler1996). Over time, B. inermis escaped and invaded native grasslands in the northern Great Plains. A study of U.S. Fish and Wildlife refuges in the northern Great Plains found that B. inermis made up to 45% to 49% of the vegetation (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Flanders-Wanner, Shaffer, Murphy and Gregg2009). The consequences of this invasion include negative impacts to soil and hydrological properties, the population dynamics of native arthropods, and native grass abundance (Palit and De Keyser Reference Palit and De Keyser2022). These impacts highlight the negative effect that B. inermis invasion has on native rangelands in the Northern Great Plains (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Shaffer and Flanders2020).

Multiple efforts have been made to develop control strategies for B. inermis. A review of the impacts of B. inermis invasion suggested that both mowing and grazing could weaken B. inermis plants (Salesman and Jessica Reference Salesman and Jessica2011). A single defoliation of B. inermis in the vegetative stage reduced the total tillers per plant in a greenhouse study (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022). Mowing and raking reduced the abundance of B. inermis on idle native prairies in North Dakota (Hendrickson and Lund Reference Hendrickson and Lund2010). In Kansas, Harmoney (Reference Harmoney2007) found that grazing reduced B. inermis on upland soils, while in North Dakota, early-season grazing (mid-May) of native rangelands reduced B. inermis abundance (Hendrickson et al. Reference Hendrickson, Kronberg and Scholljegerdes2020). Heavy grazing by horses for 2 consecutive years reduced B. inermis biomass compared with untreated controls (Stacy et al. Reference Stacy, Perryman, Stahl and Smith2005).

Despite the potential impact of defoliation as a tool to control B. inermis, there have been differing reports regarding how the timing of defoliation impacts B. inermis persistence. Eastin et al. (Reference Eastin, Teel and Langston1964) and Lawrence and Ashford (Reference Lawrence and Ashford1969) reported that defoliating B. inermis in early growth stages reduced yield. However, for controlling B. inermis through burning (Willson and Stubbendieck Reference Willson and Stubbendieck2000) or grazing (C Dixon, personal communication), the 5-leaf stage corresponding with the early elongation stage (Preister et al. Reference Preister, Kobiela, Dixon and Dekeyser2019) has been suggested as the critical phenological stage. Biligetu and Coulman (Reference Biligetu and Coulman2010) indicated that defoliating B. inermis in the vegetative stage resulted in a 14% increase in tiller numbers, but defoliating in the stem elongation stage reduced tiller numbers by 51%. Yield of B. inermis was also reduced when it was grazed by horses in the elongation stage (Stacy et al. Reference Stacy, Perryman, Stahl and Smith2005).

One of the problems with controlling B. inermis is its competitiveness (Palit and De Keyser Reference Palit and De Keyser2022). Like many clonal grasses, B. inermis often relies on vegetative growth to increase tiller density (Palit and De Keyser Reference Palit and De Keyser2022). Vegetative growth originates from axillary buds, which are the source of up to 99% of the new shoots emerging in grasslands (Benson and Hartnett Reference Benson and Hartnett2006). Growth from axillary buds provides an efficient mechanism for perennial grasses to persist or sustain their populations, even during periods of disturbance (Ott et al. Reference Ott, Butler, Rong and Xu2017, Reference Ott, Klimešová and Hartnett2019). Bromus inermis had more axillary buds per tiller and initiated more buds than western wheatgrass [Pascopyrum smithii (Rydb.) Á. Löve] (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2024), which may enhance its competitive ability. However, in both warm-season (Mullahey et al. Reference Mullahey, Waller and Moser1991) and cool-season grasses (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Busso, Montani, Burgos, Flemmer and Toribio1997), defoliation at specific growth stages impacted axillary bud numbers and activity. Bam et al. (Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022) found that a single defoliation of P. smithii in the vegetative stage increased bud dormancy.

Overall, the literature suggests (1) grazing or defoliation has the potential to reduce B. inermis abundance and (2) defoliation at certain growth stages may maximize this effect. If defoliation affects the number or outgrowth of axillary buds, it could provide an indication of the future effectiveness of the defoliation treatment. Therefore, we implemented a study to determine how defoliation of B. inermis by grazing or mowing should be timed to minimize its persistence. We defoliated individual B. inermis tillers in a field setting at different growth stages to determine the number of axillary buds and outgrowth. We hypothesized that defoliation in the culm elongation stage would result in a reduction of both outgrowth and axillary buds.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

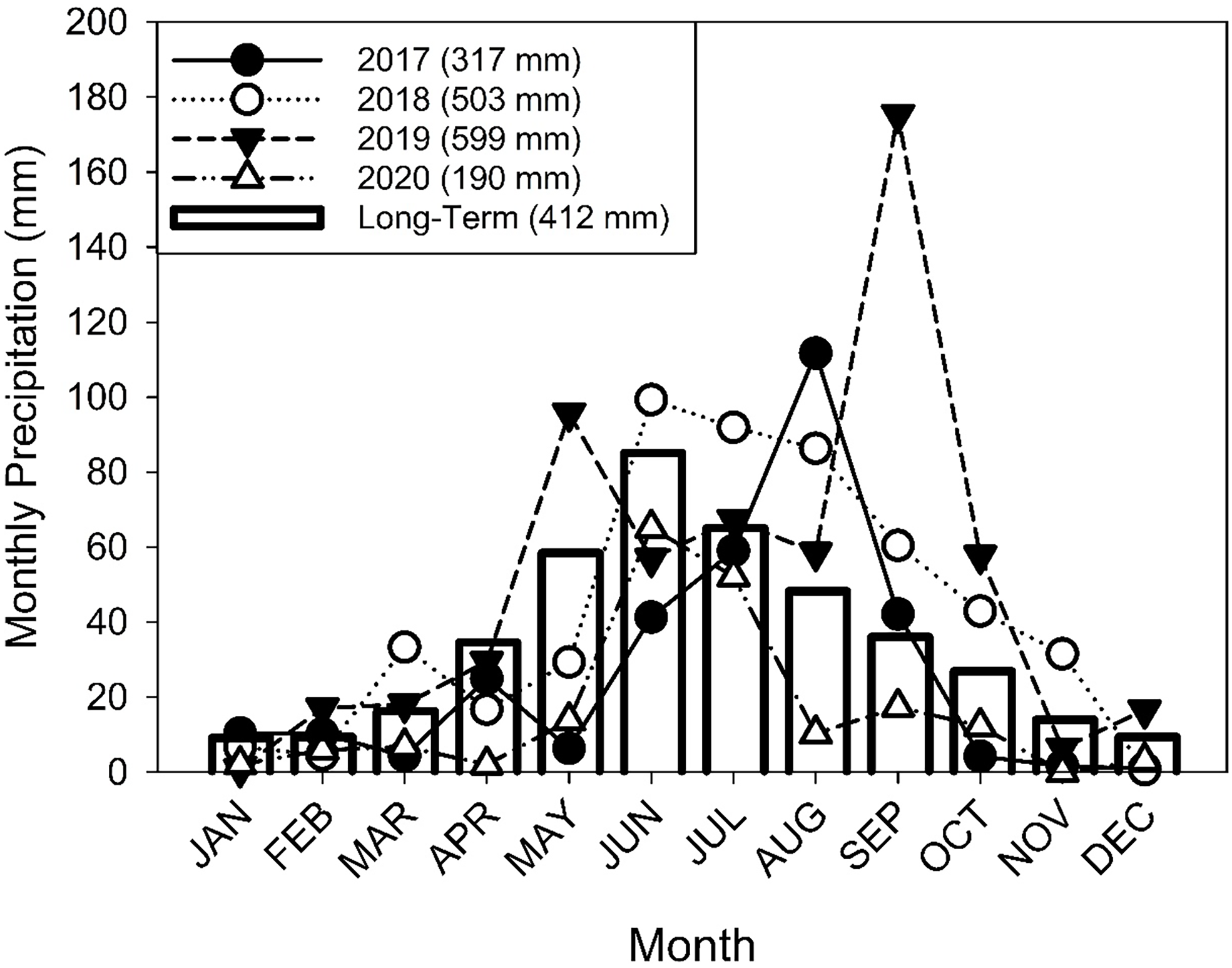

The study was initiated in May 2018 at the USDA-ARS Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory (NGPRL) located near Mandan, ND, USA (46.767085°N, 100.909112°W). The study sites were located on loamy ecological sites (Sedivec and Printz Reference Sedivec and Printz2012) on Temvik-Wilton soils (fine-silty, mixed superactive, frigid Typic and Pachic Haplustolls) (Liebig et al. Reference Liebig, Gross, Kronberg, Hanson, Frank and Phillips2006). Precipitation in both 2017 and 2020 was less than the long-term average (1913 to 2023), whereas the precipitation for 2018 and 2019 was greater than the long-term average (Figure 1). The precipitation received in September 2019 was the second highest on record for the month.

Figure 1. Average monthly precipitation at the Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory (NGPRL) for 2017–2020 and the long-term (1913–2020) average. Precipitation from April to October was gathered from a North Dakota Automated Weather Network station (NDAWN). Precipitation for the remaining months and the long-term average were taken from a U.S. Weather Service station located 5 km north of the study site.

The study took place within three sites that had not been grazed since 1981. Each site was a 40 by 25 m exclosure, fenced with a three-wire barbed wire fence, preventing livestock from grazing but potentially allowing some wildlife grazing (deer and small mammals). All study sites were located within 0.4 km of each other.

A previous study on the pastures in which the study sites were located found the surrounding pasture was dominated by Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) and B. inermis, but with the native grasses P. smithii, purple threeawn (Aristida purpurea Nutt.), and needleandthread [Nassella viridula (Trin.) Barkworth] also being present (Hendrickson et al. Reference Hendrickson, Kronberg and Scholljegerdes2020). Those authors reported more than 20 different forb species, with field pussytoes (Antennaria neglecta Greene) being the most abundant, and western snowberry (Symphoricarpos occidentalis Hook.) and leadplant (Amorpha canescens Pursh) in lesser amounts. Visual evaluation of the study sites indicated greater B. inermis abundance within the exclosed study sites than in the surrounding pastures.

Tiller emergence in B. inermis starts in the early spring (Otfinowski et al. Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007), and tillers begin to elongate and flower in summer (Lamp Reference Lamp1952; Otfinowski et al. Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007). Tiller emergence can begin again after anthesis, but these tillers often do not elongate (Lamp Reference Lamp1952) until the following spring (Lamp Reference Lamp1952; Otfinowski et al. Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007). Most tillers that elevate their apices in the fall do not survive the winter (Otfinowski et al. Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007).

Field Procedures

In the spring (May) of 2018, 2019, and 2020, each study site had 50 B. inermis tillers randomly assigned to 5 different defoliation treatments (10 tillers per treatment). Tillers were at least 1 m apart from each other. Spacing was based on Otfinowski et al. (Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007), who found B. inermis rhizomes may expand up to 83 cm into adjacent native prairie over two growing seasons. The tillers were defoliated by clipping at a height of 5 cm. Defoliation treatments were implemented by defoliating 10 tillers at either (1) once in the vegetative stage (V1); (2) twice in the vegetative stage (V2); (3) once in the elongation stage (E); (4) once in the reproductive stage (R), and (5) an undefoliated control (C) for a total of 50 tillers plot-1 year-1. Colored wires were placed at the base of each tiller to determine the defoliation treatment and assist in relocating the tiller in the fall. Bromus inermis is rhizomatous, and only the tiller marked by the wire was defoliated during the clipping treatment.

The 50 B. inermis plants per site were destructively harvested in the fall (October to November) after senescence. Tillers were located using the colored wires placed on them in the spring and marked at the base with nail polish for further identification. A 5-cm-diameter area was excavated around the marked tiller to a depth of approximately 3.5 cm. Excess dirt was removed if possible, and the tiller was placed in a ziplock bag (Ziploc®) with a moist paper towel, then stored at 4 C until processed. Each tiller was processed within 10 d of harvesting.

Laboratory Procedures

During processing, tillers were washed, and leaves were removed until only the crown remained. Because each phytomer has the potential to form an axillary bud, phytomers that were above the soil surface were excluded from processing. In addition, the rhizomatous nature of B. inermis can make it difficult to differentiate between rhizome and crown. Examination of the tillers showed a lengthening of the internode near the base of the plant on the rhizome. Therefore, we chose this lengthening as the point to differentiate between rhizome and crown.

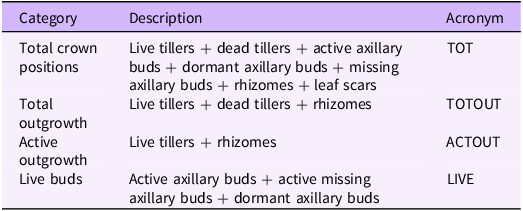

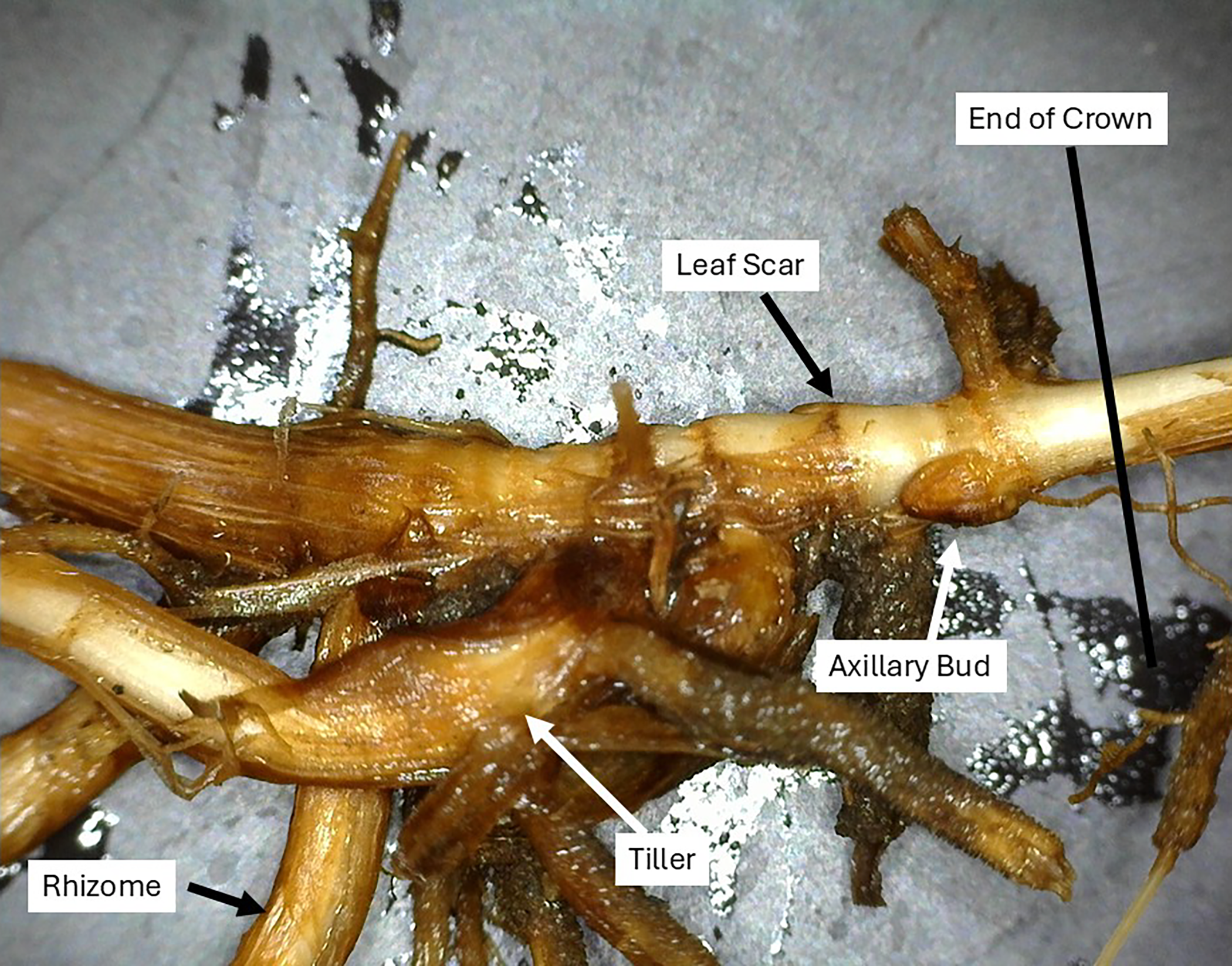

Crowns were examined under a binocular microscope, and crown positions (i.e., either outgrowth or potential bud location) were classified into categories. Categories included (1) live tillers, (2) dead tillers, (3) axillary buds, (4) missing buds, (5) rhizomes, and (6) leaf scars (Table 1; Figure 2). Leaf scars are crown positions where the existence of leaf attachment suggests that an axillary bud exists but there is no evidence of a bud (Figure 2). A bud was considered to have transitioned into a tiller or rhizome (Figure 2) when either portion could be identified as having emerged from the soil surface or there was visual evidence of leaf formation. Missing buds were crown positions where there was evidence of a bud, but it was removed during processing. We considered the point where the crown separated from the rhizome as the spot where the node lengthened below the crown.

Table 1. Category, description and acronym of each grouping of axillary buds and outgrowth used in analyses.

Figure 2. A crown base showing an axillary bud, leaf scar, tiller, rhizome, and the point where the crown was separated from the rhizome (end of crown).

Crowns that had axillary buds and/or missing buds were placed into vials with a (1g L-1) solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride for 24 h at 20 C. Vials were wrapped in aluminum foil and placed in a cabinet. After 24 h, axillary buds and/or missing buds were examined for a red stain indicating activity. If no red stain was present, tillers were placed in a (2.5g L-1) solution of Evans Blue for 20 min. A deep blue stain indicated the axillary bud was dead. If buds were not stained with either red or blue, they were considered dormant (Busso et al. Reference Busso, Mueller and Richards1989; Hendrickson and Briske Reference Hendrickson and Briske1997).

After crowns were processed and activity was evaluated, crown positions were grouped into categories. These categories were used to further understand B. inermis responses to defoliation. For a list of categories and their descriptions and acronyms, see Table 1.

Data Analysis

The experiment was a randomized complete block design that was blocked by site. Each treatment was replicated 10 times in each block each year. Because each tiller within a site had a treatment randomly assigned to it, each tiller was considered an experimental unit. Data were analyzed using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS® 9.4 (SAS/STAT 15.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) with the fixed effects of year and treatment and their interactions. Because the response variables were primary count data, the model used a Poisson distribution to evaluate the error terms. In 2019 and 2020, but not in 2018, we also evaluated the mortality of the defoliated parent tillers marked during the treatment phase. To evaluate the mortality of the defoliated marked tillers in 2019 and 2020, the number of dead marked tillers was divided by the total marked tillers within each defoliation treatment in each block. Because there were two mutually exclusive outcomes (the tiller was either live or dead), data were modeled using a binomial distribution with the GLIMMIX procedure. Least-squares mean differences were determined using the LSMEANS option with the Tukey-Kramer adjustment at an α = 0.10 unless otherwise noted.

Most of the parent tillers (77%) did not have any dead buds, so we did not further analyze the effect of treatment or year on dead buds. Although most parent tillers did not have dormant axillary buds, we combined both active and dormant axillary buds into a live bud category, as both had the ability to produce new outgrowth. The number of live buds per tiller was assessed for overdispersion of the response, and two processes were determined to be in effect. For the live bud response, when the bud was not present, the only outcome possible was a zero, and when the bud was present, the response was a count process of total number of buds present. Thus, a zero-inflated model was determined as the most robust approach here. The live bud response was analyzed using the GENMOD procedure in SAS® 9.4. The two parts of this zero-inflated model are a binary model, which is a logit distribution to model which of the two processes the zero outcome is associated with (i.e., the probability of having buds or not having buds) and a count model, in this case a negative binomial model, to model the count process (which only exists in the presence of buds).

Results and Discussion

Bromus inermis is one of the major invasive grasses on rangelands in the Northern Great Plains, and available control options are few. We rejected our null hypothesis that defoliating B. inermis in the culm elongation stage would reduce the number of axillary buds and total outgrowth (tillers and rhizomes). We found when parent tillers were defoliated in the elongation stage, the number of tillers and rhizomes produced by the parent tiller was similar to the number produced by the undefoliated controls. Instead, defoliating twice in the vegetative stage was the most promising strategy to reduce the amount of outgrowth produced per tiller. Defoliating B. inermis in the reproductive stage was the least effective treatment and resulted in the highest number of crown positions, total number of tillers and rhizomes produced over the growing season, and number of tillers and rhizomes remaining active at harvest.

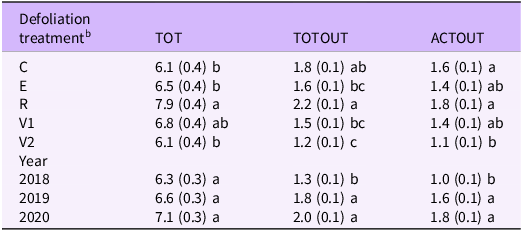

The growth stage when the parent tiller was defoliated affected the number of crown positions (F(4, 438) = 2.63; P = 0.034), the number of tillers and rhizomes produced by a defoliated tiller (F(4, 438) = 6.70; P ≤0.0001), and the number of tillers and rhizomes still viable at the end of the growing season (F(4, 438) = 4.02; P = 0.0033) (Table 2). Year impacted the number of tillers and rhizomes produced by a defoliated tiller (F(2, 438) = 9.13; P = 0.0001) and the number of rhizomes and tillers still viable at the end of the growing season (F(2, 438) = 13.34; P = <0.0001), but not the total number of crown positions (F(2, 438) = 1.39; P = 0.2509). However, there was not a year by growth stage interaction when defoliated for number of crown positions (F(8, 438) = 0.83; P = 0.5793), the number of tillers and rhizomes produced by the defoliated tiller (F(8, 438) = 0.96; P = 0.4651), or the number of tillers and rhizomes still alive at the end of the growing season (F(8, 438) = 0.68; P = 0.7073).

Table 2. Mean number of positions for total crown positions (TOT), total number of crown positions with tillers or rhizomes (TOTOUT), and total number of crown positions with live tillers or rhizomes (ACTOUT) for different defoliation times and years a .

a Standard errors of the means are in parentheses next to means. Means with different letters within a column indicate differences between treatment or years at P ≤ 0.10.

b Defoliation treatments were (1) undefoliated or control tillers (C), (2) tillers defoliated in the elongation stage (E), (3) tillers defoliated in the reproductive stage (R), (4) tillers defoliated once in the vegetative stage (V1), and (5) tillers defoliated twice in the vegetative stage (V2).

In a greenhouse study, Bam et al. (Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022) found that a single defoliation in the vegetative stage produced a minor but significant reduction in whole-plant tiller and rhizome numbers in B. inermis and P. smithii. In our field study, a single defoliation of the parent tiller in the vegetative stage (V1) produced a slight and insignificant reduction in the total number of tillers and rhizomes produced by the parent tiller (TOTOUT) or those tillers and rhizomes that remained active in the fall (ACTOUT) (Table 2). However, defoliating the parent tiller twice in the vegetative stage (V2) did reduce the number of tillers and rhizomes produced (TOTOUT and ACTOUT) compared with the undefoliated control (Table 2). Bromus inermis generally has two tiller cohorts during the growing season (Lamp Reference Lamp1952), although Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Moser, Moore and Redfearn1998) reported three periods in eastern Nebraska. They also reported that depending on the year, B. inermis tiller populations could be primarily vegetative until mid- to late May. The population structure of B. inermis early in the growing season may provide opportunities to apply the V2 treatment. The V2 treatment may mimic the more intensive defoliation by sheep, cattle, or mowing that has been previously been reported to reduce tiller density in B. inermis (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Dhar and Naeth2024).

The 5-leaf stage (Willson and Stubbendieck Reference Willson and Stubbendieck2000) has previously been suggested as the optimum time to apply management treatments such as burning or grazing. As Preister et al. (Reference Preister, Kobiela, Dixon and Dekeyser2019) noted, the 5-leaf stage is well correlated with the early elongation stage in B. inermis. However, our results did not support using this stage as a management guide. We found that defoliating the parent tiller in the elongation stage did not reduce either the total number of tillers and rhizomes produced per tiller or the number remaining active in the fall, compared with the undefoliated controls (Table 2). Willson and Stubbendieck (Reference Willson and Stubbendieck2000) developed their recommendations from studies in areas with greater precipitation (eastern Nebraska and western Minnesota), which may explain the different responses in our two studies. They also highlighted the importance of species composition (i.e., having enough desired species) to achieving desired results from control measures.

As previously indicated, our field study found defoliating the tiller twice in the vegetative stage (V2) was the most promising defoliation treatment for limiting outgrowth on B. inermis tillers (Table 2), because compared with the undefoliated controls, defoliation at this stage reduced the number of tillers and rhizomes produced over the entire season (TOTOUT) and the number of tillers and rhizomes remaining active into the fall (ACTOUT). In contrast, defoliating the parent tiller in the reproductive stage (R) resulted in an increase in the total number of crown position (TOT) compared with most other treatments, except the V1 treatment, and greater total outgrowth (TOTOUT) and greater active outgrowth (ACTOUT) than the V2 defoliation treatment. Paulsen and Smith (Reference Paulsen and Smith1969) also noted an increase in tillers per B. inermis stem grown in vitro after the plant initiated reproductive development, but Biligetu and Coulman (Reference Biligetu and Coulman2010) reported lower tiller densities when B. inermis was defoliated after elongation. However, they did not defoliate tillers at growth stages later than stem elongation. Tiller emergence in B. inermis tends to occur in the spring and after anthesis (Lamp Reference Lamp1952). While defoliation of the parent tillers in the reproductive (R) stage occurred before anthesis, it may have been close enough to anthesis to not affect outgrowth.

The increased outgrowth when the parent tillers were defoliated at the reproductive stage suggests that apical dominance may be regulating outgrowth in these grasses (Kebrom Reference Kebrom2017). However, the mechanisms regulating apical dominance are complex, and research focus has recently switched from apical dominance being regulated by auxin to regulation by novel classes of plant hormones and sugars (Beveridge et al. Reference Beveridge, Rameau and Wijerathna-Yapa2023). Regardless of the mechanism, our data suggest that management strategies focusing on reducing the B. inermis outgrowth should avoid defoliating B. inermis in the reproductive stage.

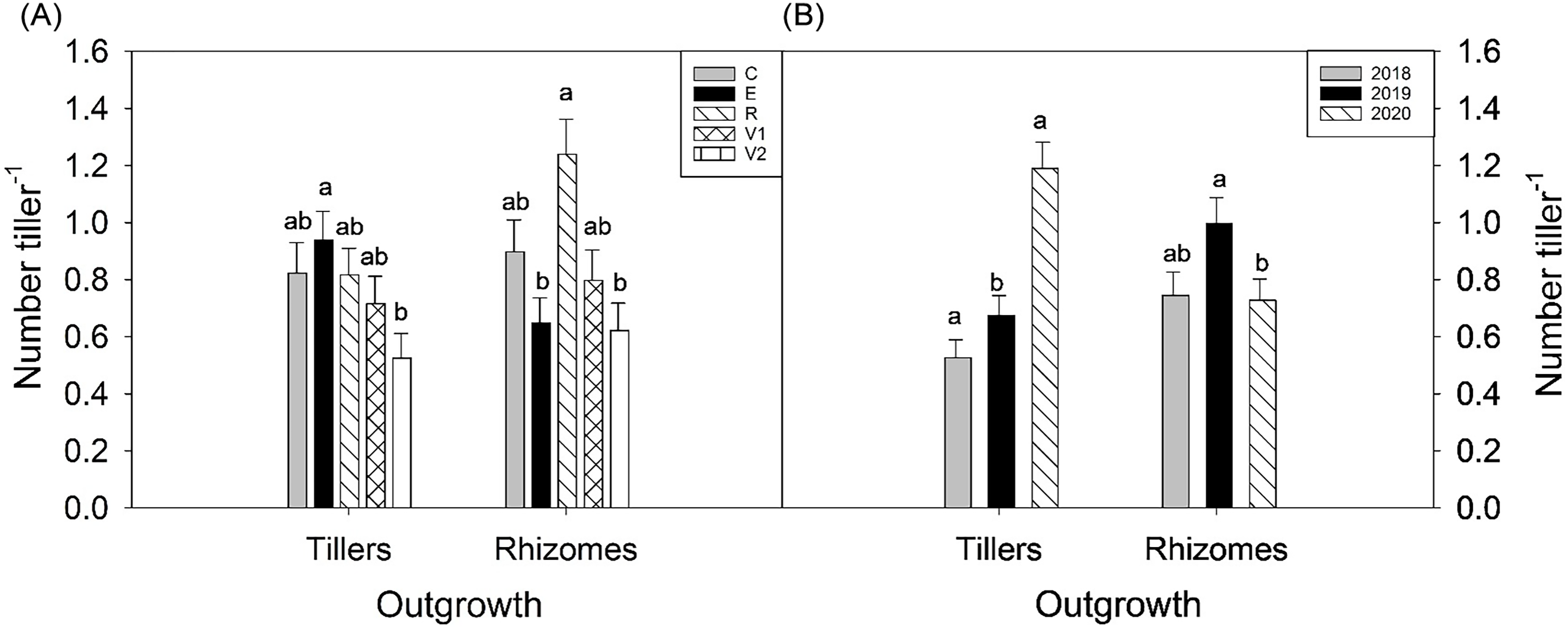

When tillers were defoliated in the reproductive stage, they also had more rhizomes per tiller than if they were defoliated in the elongation stage (P = 0.0011) or twice in the vegetative stage (P = 0.0019) (Figure 3A). Defoliating parent tillers twice in the vegetative stage also resulted in fewer tillers per tiller than when parent tillers were defoliated in the elongation stage (P = 0.0273; Figure 3A). Changes in the numbers of tillers and rhizomes can indicate a change in belowground growth strategy from a “phalanx’ strategy with tightly grouped tillers to a “guerilla” strategy with more widely spaced stems (Lovett-Doust Reference Lovett-Doust1981). The increase of rhizomes when B. inermis is defoliated during the reproductive stage may help it spread and invade new areas (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2024).

Figure 3. The number of tillers and rhizomes produced per tiller by (A) defoliation treatment and (B) by year. Defoliation treatments were (1) undefoliated controls (C), (2) defoliated in the elongation stage (E), (3) defoliated in the reproductive stage (R), (4) defoliated once in the vegetative stage (V1), and (5) defoliated twice in the vegetative stage (V2).

There were differences between years in the number of tillers and rhizomes produced by an individual tiller (Figure 3B). We found that the wettest year (2019) maximized the number of rhizomes, but the driest year (2020) had the greatest number of tillers per parent tiller. There may be several factors leading to the increase of tillers versus rhizomes in 2020. The autumn of 2019, especially September, was very wet, and the increased precipitation may have increased tiller emergence the following spring. Eastin et al. (Reference Eastin, Teel and Langston1964) had reported that tillering in B. inermis ceased by the elongation phase, and the increased soil moisture the previous autumn and into the spring may have benefited tillers more than rhizomes. New tillers that emerged in 2020 may have developed the previous autumn (Lamp Reference Lamp1952), but rhizomes are not initiated until plants are older, such as the 4-leaf stage (Otfinowski et al. Reference Otfinowski, Kenkel and Catling2007).

The distribution of precipitation may have also affected the number of tillers and rhizomes. While both 2018 and 2019 had similar amounts of annual precipitation (Figure 1), the distribution was different, with 2018 having greater precipitation in June, July, and August, but 2019 had greater precipitation in May and September. In a greenhouse study, Bam et al. (Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022) found that an intermediate watering regime (every 8 d) produced more rhizomes on B. inermis than an infrequent watering (every 16 d). Therefore, changes in precipitation frequency may have affected the numerical distribution of tillers and rhizomes.

Total and active outgrowth per tiller was also affected by year. Total and active outgrowth (Table 2) were both lower in 2018 than in 2019 and 2020. This was unexpected, as 2020 had the lowest precipitation of any of the 3 sampling years (Figure 1). However, tying outgrowth to precipitation has been difficult in cool-season grasses. Mitchell et al. (Reference Mitchell, Moser, Moore and Redfearn1998) suggested that increased tiller numbers in intermediate wheatgrass [Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey] was due to increased precipitation, but changes in early-season tiller numbers between years for B. inermis was driven by temperature. Hendrickson and Berdahl (Reference Hendrickson and Berdahl2002) found tiller numbers were not impacted by water stress in T. intermedium or Russian wildrye [Psathyrostachys juncea (Fisch.) Nevski]. For our study, precipitation during the previous year may have affected tiller outgrowth as has been reported for warm-season grasses (Hendrickson et al. Reference Hendrickson, Moser and Reece2000). Therefore, the lower outgrowth per tiller in 2018 may reflect lower precipitation in 2017, and the higher outgrowth in 2020 could be a result of increased precipitation in the fall of 2019 (Figure 1). In 2020, tillers more than rhizomes contributed to increased outgrowth (Figure 3B). Bam et al. (Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022) found that outgrowth can be affected by decreased precipitation frequency. In their greenhouse study, B. inermis plants watered less frequently produced fewer total tillers and rhizomes than plants watered more frequency, despite all treatments receiving the same amount of water.

One other possibility with the different moisture distributions between years is a change in the age of the tiller population. For example, precipitation in the fall of 2019 followed by a dry summer in 2020 may have resulted in a majority of the tiller population for 2020 being initiated in the fall of 2019 (see Lamp Reference Lamp1952). Whereas in 2018, the dry 2017 followed by a more normal 2018 may have resulted in tillers being initiated in the spring of 2018. The tiller population in 2020 would have been “older” with potentially more time to produce outgrowth than the “younger” tiller population in 2018.

The number of tillers and rhizomes per tiller that remained alive at harvest (ACTOUT) can give insight into whether the population of B. inermis tillers is increasing or decreasing similar to a tiller replacement ratio (Briske and Hendrickson Reference Briske and Hendrickson1998; Olson and Richards Reference Olson and Richards1988). There were differences in ACTOUT between defoliation treatments and between years (Table 2). ACTOUT responded similarly to parent tiller defoliation treatments as TOTOUT, with the greatest number of tillers or rhizomes still alive at the end of the growing season occurring when B. inermis was defoliated in the reproductive stage (Table 2). The lowest value of ACTOUT was 1.1 when the tillers were defoliated twice in the vegetative stage (V2). A tiller replacement ratio >1 suggests that a population is growing (Hendrickson et al. Reference Hendrickson, Berdahl, Liebig and Karn2005). Because ACTOUT was >1 for all treatments, this suggests that none of the defoliation treatments were sufficient to reduce the population of B. inermis (Table 2).

Our study focused on the outgrowth from a single tiller. However, under certain conditions, B. inermis may produce nearly half of new tillers from the nodes and tips of rhizomes (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2024). If the new tillers arising from rhizomes are not defoliated or are defoliated at a different time than the original tiller, it could affect the affect the abundance of B. inermis on a per unit area basis. The age of axillary buds can also affect outgrowth. Generally, younger buds located at the distal end of the crown are more likely to produce outgrowth (Hendrickson and Briske Reference Hendrickson and Briske1997). In our study, axillary buds located on rhizomes or new tillers may be younger and more likely to grow out than axillary buds on the original defoliated tiller. Because we focused on the outgrowth from a single tiller, we did not measure the impact of defoliation on these younger axillary buds.

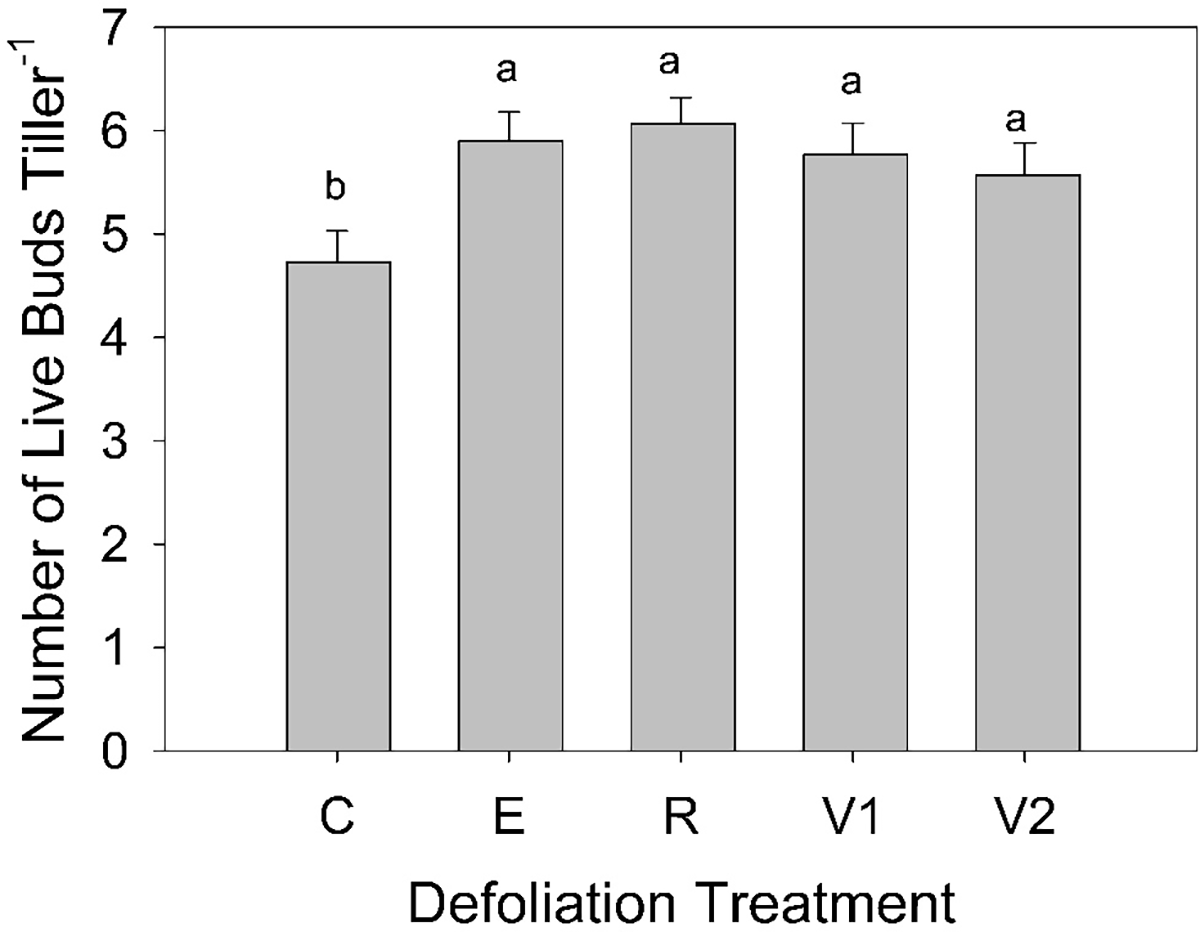

The number of axillary buds or bud banks is an important mechanism regulating population dynamics in perennial grasses (Ott et al. Reference Ott, Klimešová and Hartnett2019). A majority of our tillers did not have dormant axillary buds (66%), and we did not see clear trends in the impact of defoliation treatment or year. Therefore, we combined active buds and dormant buds into a category called “live buds,” as both could potentially produce outgrowth. After the categories were combined, approximately 13% of the parent tillers did not have any active or dormant buds. This was generally caused when a crown position did not form an axillary bud but other indicators (i.e., leaf scars) suggesting the potential for forming an axillary bud (Hendrickson and Briske Reference Hendrickson and Briske1997). Overdispersion of the tillers without any active or dormant buds revealed that analysis of these data was most appropriate with a zero-inflated model. The probability that a parent tiller would not have any live buds was not affected by defoliation treatment (P ≤ 0.05). However, the undefoliated controls (C) had fewer live buds than did any of the defoliation treatments (Figure 4).

Mullahey et al. (Reference Mullahey, Waller and Moser1991) found defoliation at different time periods reduced bud densities in two warm-season perennial grass species, and Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Busso, Montani, Burgos, Flemmer and Toribio1997) found that defoliating two cool-season tussock grasses after the elongation stage reduced active axillary buds. However, an evaluation of clipping frequency on crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum (L.) Gaertn.] and hybrid bromegrass (Bromus inermis × Bromus riparius Rehmann) identified no differences in axillary bud number based on defoliation frequency (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Mactaggart, Wang, Chibbar, Li and Biligetu2022). In a greenhouse study, a single defoliation of B. inermis increased axillary bud dormancy (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2022). While we did not see trends in dormant axillary buds, we found fewer active and dormant buds on our undefoliated controls compared with the defoliated tillers. Undefoliated tillers had fewer crown positions but more outgrowth resulting in fewer live axillary buds per tiller (Figure 4). Because axillary buds are the basis for future population growth (Murphy and Briske Reference Murphy and Briske1992; Ott et al. Reference Ott, Klimešová and Hartnett2019), knowing there are fewer live axillary buds per tiller on the undefoliated tillers may provide opportunities for future burning or grazing scenarios. However, even the undefoliated control tillers had an average of 4.7 axillary buds per tiller (Figure 4), which still provides more than adequate meristematic potential for future growth.

Figure 4. The number of live axillary buds (active + dormant) per tiller for each defoliation treatment. Defoliation treatments were (1) undefoliated controls (C), (2) defoliated in the elongation stage (E), (3) defoliated in the reproductive stage (R), (4) defoliated once in the vegetative stage (V1), and (5) defoliated twice in the vegetative stage (V2).

In 2019 and 2020, we also evaluated the direct mortality of the parent tillers when defoliated at different growth stages. Defoliation at different growth stages did impact the survivorship of the parent tiller (P = 0.0002). Individual tiller mortality ranged from 99 ± 2% for tillers defoliated in the R stage to 15 ± 5% for the undefoliated tillers in the C treatment. Tillers defoliated in the R stage (99 ± 2%) and E stage (99 ± 4%) had similar mortalities, but their mortalities were greater than for tillers defoliated in the V2 stage (75 ± 6%). Mortality for tillers defoliated in the R, E, and V2 stages was also different than for tillers defoliated in the V1 stage (22 ± 6%) and undefoliated tillers in the C treatment (15 ± 5%).

Greater mortality for tillers defoliated at later growth stages is unsurprising considering that the shoot apex was elevated and removed with the defoliation. Removal of this apex causes the tiller to die (Nelson and Moore Reference Nelson, Moore, Moore, Collins, Nelson and Redfearn2020), which explains the nearly 100% tiller mortality when defoliated in the elongation or reproductive stage. However, although parent tillers had greater mortality when defoliated at later growth stages, they also had greater outgrowth. Outgrowth that remained alive until the end of the growing season (ACTOUT) averaged 1.8 for parent tillers defoliated in the reproductive stage and 1.4 for tillers defoliated in the elongation stage (Table 2). This suggests that every tiller that died after being defoliated in the reproductive or elongation stage was not only replaced but had additional outgrowth (0.8 and 0.4 outgrowth per tiller for reproductive and elongation, respectively) that remained alive until the end of the growing season.

The objective of this study was to determine how defoliating B. inermis at different growth stages would affect outgrowth and number of axillary buds on the crown. We did focus on defoliating single tillers at each growth stage and assessed the outgrowth arising from those single tillers. This may have affected our results in that (1) B. inermis populations are made up of a wide variety of morphological growth stages (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Moser, Moore and Redfearn1998); (2) many new tillers are initiated by rhizomes (Bam et al. Reference Bam, Ott, Butler and Xu2024); and (3) selective herbivory (Schmitz Reference Schmitz2008) and other factors (Willson and Stubbendieck Reference Willson and Stubbendieck2000) can affect treatment responses.

Even so, this study provides valuable baseline information needed to further research into controlling B. inermis. In semiarid regions, more emphasis should be placed on defoliating B. inermis in the vegetative stage rather than at later growth stages. Our data also suggest that because of B. inermis’s meristematic potential (i.e., outgrowth and axillary buds), its population can continue to increase even after defoliation treatment. This suggests that multiple defoliation events over several years may be necessary to reduce its abundance. Additional demographic research into the number and timing of defoliations could provide further insights into controlling B. inermis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge A. Hintz, J. Hanson, A. Schiwal, J. Morrissette, C. Kobilansky, and J. Feld for help with data collection and tiller dissection. The USDA prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by USDA of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.