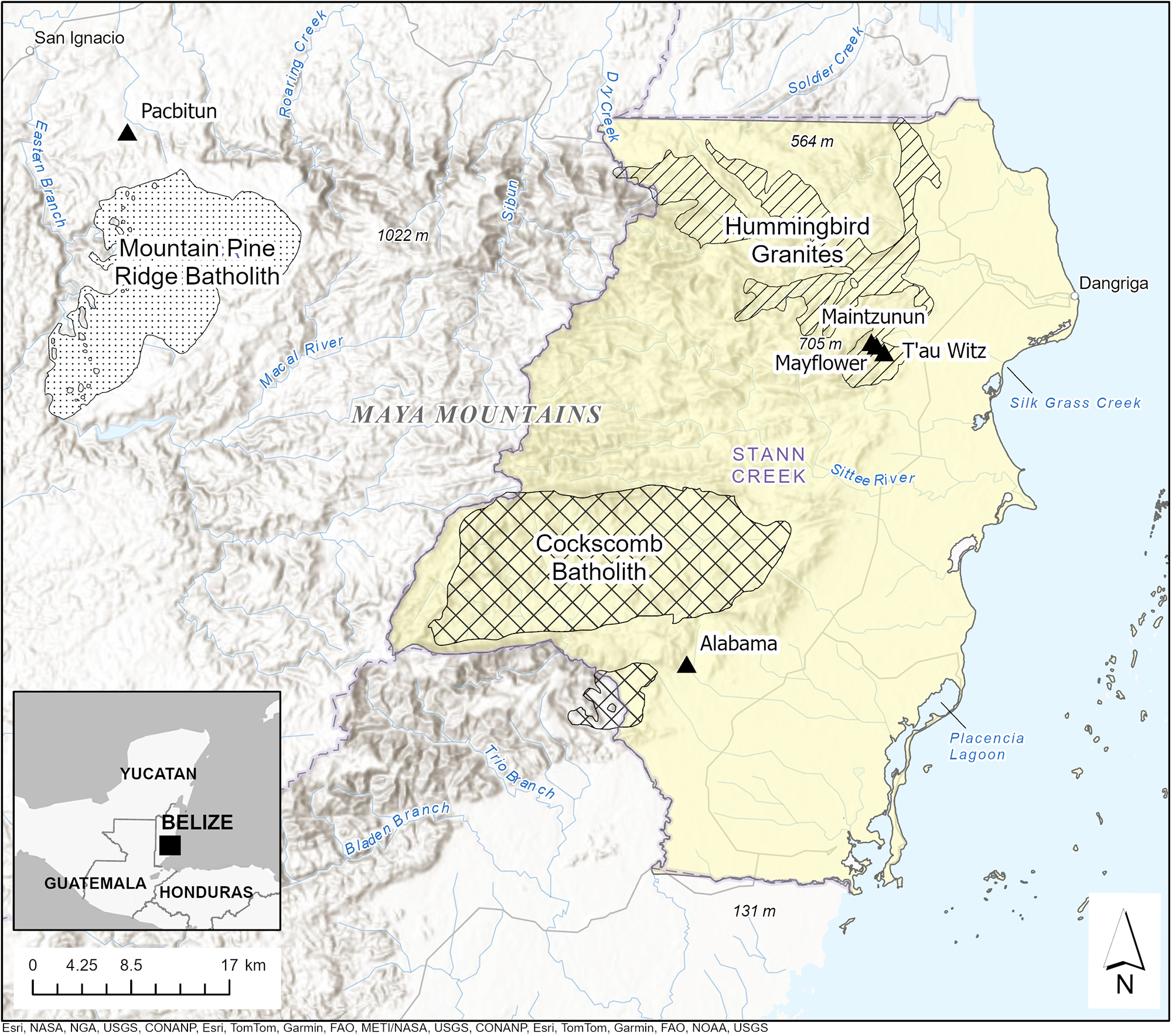

When the editors asked me to provide a retrospective on ground stone studies, my reaction was that I was not sure I had much of substance to add. Ground stone studies have proceeded at a rapid pace since Webster Shipley and I first experimented with sourcing granite manos that had been recovered in Guatemala at the sites of Ceibal (then, Seibal) and Uaxactun (Shipley and Graham Reference Graham1987). Aside from strongly encouraging studies of ground stone at the sites I was excavating, my own research headed in other directions. My interest in ground stone, however, never diminished. I was delighted at Terry Powis’s invitation to visit the granite workshops at Pacbitun, and pleased to meet John Spenard in Belmopan recently, where I learned about his workshop discoveries in the Maya Mountains (see Figure 1 for a map of sites mentioned in the text). Tawny Tibbits has sampled ground stone at Lamanai; her research (Tibbits Reference Tibbits2016) demonstrates that non-destructive portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) carried out in the field can accurately characterize the geochemistry of granites and their products. Her work constitutes a breakthrough not only in ground stone research but in pioneering methods that significantly advance studies of short- and long-distance trade and exchange.

Figure 1. Map of sites mentioned in the text.

I have followed Meaghan Peuramaki-Brown and Shawn Morton’s excavations at Alabama closely; Alabama was included in my survey of sites in the Stann Creek District from 1975 to 1977 (Graham Reference Graham1994:132). I carried out no excavations there but was pleased when I heard that Meaghan and Shawn had begun work at the site. Excavation in the Stann Creek District is challenging because the acidic soils discourage preservation of pottery, especially the fine ceramics tempered with calcite. Dating is more difficult than in areas where the soil parent material is limestone (Graham Reference Graham1994:345–346). Yet, based on the geology of the Stann Creek District and its resources—granites, clays, clay minerals, and tree crops such as cacao that prefer acid soils—as well as Alabama’s proximity to Placencia Lagoon and the opportunities for access to multiple coastal way stations along the Placencia spit, I remain convinced that Alabama had a far wider reach in the Maya world than might be assumed from its relatively small size. Reminded of these personal connections, I thought that perhaps, as an old granite fan, I could hazard to comment on the history of granite and ground stone research.

Granite backstory

In the late 1970s, Webster Shipley—who was surveying the granite batholiths—gave me the idea that granites could be sourced. I was staying at Government House at Augustine in the Mountain Pine Ridge. At the time, Shipley was part of a group of geologists carrying out exploration of the Maya Mountains for the Anschutz Mining Corporation based in Colorado. The individuals in the group were enrolled in a degree program at the Colorado School of Mines (CSM) in Golden, and their reports, including Shipley’s (Reference Shipley1978), were deposited in the CSM library. Based on the success of our petrographic analysis of the manos from Ceibal and Uaxactun (Shipley and Graham Reference Graham1987), Shipley and I planned to “mine” the other reports of the group to re-locate and sample materials that we knew could potentially have been utilized by the pre-Columbian Maya. In addition to potential raw materials for manos and metates, materials included slate, albite, copper, and gold. I was also following through on what I had proposed in my 1987 American Antiquity article (Graham Reference Graham1987), which is that we archaeologists need to focus on identifying local resources before we aim to excavate Maya sites. Unfortunately, our grant application to National Geographic failed. Shipley and his fellow CSM students dispersed and the opportunity to build on their results sadly passed.

Much later, when I moved to London and joined the staff of the Institute of Archaeology at University College London, one of my graduate students, Marc Abramiuk, carried out Ph.D. field research on settlements and sources of ground stone in the Bladen catchment area (Abramiuk Reference Abramiuk2005; Abramiuk and Meurer Reference Abramiuk and Meurer2006). Sometime later, I attempted to purchase from CSM all the Anschutz Mining reports covering the Maya Mountains but found that the reports had been discarded during a library move. The reports were, however, deposited in Belize in the Geology Department, now the Petroleum and Geology Department, and are worth examining by anyone interested in Maya Mountains resources.

A foundation for ground stone sourcing

One implication of the early work by Shipley and me was that pinpointing sources of granite used in ground stone tool (GST) manufacture was possible. We were able to show, through petrographic analysis, that granite used in the manufacture of manos recovered at the sites of Ceibal and Uaxactun matched granitic intrusions in Belize, where three granite batholiths are known (Shipley Reference Shipley1978). At the time, granitic intrusions in Guatemala were not characterized (although see Laporte Reference Laporte and Sanders1996). As I note above, Tibbits (Reference Tibbits2016) and her colleagues (Tibbits et al. Reference Tibbits, Peuramaki-Brown, Burg, Tibbits and Harrison-Buck2023) have since revolutionized the ease with which granite can be characterized through XRF and pXRF. Another implication of our early work, and a driving force behind the research described in this Compact Section, is that sourcing GST is important in hypothesizing the nature and direction of routes of trade and exchange involving the eastern lowlands, and beyond.

New horizons

The ground stone studies in this Compact Section show how research on GST has expanded. Not only is sourcing being refined, but long-awaited attention is being given to mining and production locales, as well as to production processes. Rocks such as limestone and basalt (and the Bladen volcanics in Belize [Abramiuk and Meurer Reference Abramiuk and Meurer2006]) were used in the manufacture of manos and metates, but granite manos and metates were the most common, at least throughout the southern lowlands, and are represented in settlements far beyond their sources.

In the introductory article in this section, Brouwer Burg, Spenard, and Tibbits observe that GST analysis has suffered some neglect in the Belize region. Manos and metates do not carry the cachet of jade, yet in many ways they have the potential to provide information on trade and exchange that jade cannot (see Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Aspinall, Feather, Hazelden, Gazard, Agrell, Earle and Ericson1977). There are at least two reasons. One is that the raw material of manos and metates can, we now know, be sourced to a specific location among a range of possibilities in the landscape. Another is that everyone, elite and non-elite families, used manos and metates. They were essential—foundational, as described in the introduction—and their demand would not likely have disappeared if regimes changed or people shifted location. Even with the introduction of the tortilla/comal in the Terminal Classic–Early Postclassic, maize needed to be ground. In fact, one could argue that the production locale and distribution of manos and metates provide primary keys to an understanding of trade and exchange routes in the Maya area.

In the introduction, the authors expand on the socioeconomic dimensions of GST. Importance lies not only in the material and its source but also in how the GST were made and where they were made. Locating sources is one thing but the actual manufacture of tools is another. When did manufacture and use take place? The authors discuss the provisioning of markets to distribute GST, and they present good evidence for the existence of an organized system of market-based exchange. They also consider direct exchange either between individuals or via itinerant peddlers. In the case of direct exchange, distance may not have been an impediment because the exchange would have been driven by social rather than strictly commercial considerations.

Relating the batholith to the settlement where the GST are found seems roughly, but not always, linked to proximity. At one time I promoted a downstream model for the Stann Creek District (Graham Reference Graham1994), as well as the likelihood that the ubiquitous granite boulders in rivers and streams were probably exploited in addition to the actual batholith. Regarding waterborne transport, however, the west-to-east rivers that drain the foothills of the Maya Mountains in Stann Creek are numerous, but not all are navigable by canoe. Tumpline transport to the coast was probably common. Although metates seem like a heavy load for humans to carry, a Google Image search of tumplines in use by the Maya in recent times shows that heavy loads (stacks of Coca Cola crates, furniture, even seated individuals) are not unusual. Drennan (Reference Drennan1984) examines transport costs in Mesoamerica and reports that loads range from 20 to 50 kg, and that an individual could carry such weights for 35 km. David Pendergast (personal communication 2001) was told by his Altun Ha foreman from Succotz that a grand piano was once carried via tumpline by a team of men from southern Belize to highland Guatemala!

The industrial-scale granite extraction and ground stone tool crafting described by Spenard and colleagues comprise a huge leap forward in envisioning the important role of GST in Maya life. Small- and large-scale quarries existed, which suggests that production knowledge—that is, how to make a mano or metate—may not always have been restricted to a limited number of specialists. Distinguishing the implements used to make GST is a critical step enabling us to identify such implements in occupational or other assemblages. Tool identification and the production process were also a focus of the work at Pacbitun, reported in this section by King and Powis. Terraced work areas were dedicated to the production of GST. Sand was a product of the working of granite. At some of the sites in Stann Creek, such as Mayflower and Maintzunun along Silk Grass Creek, sand formed a floor component, as did weathered granite (Graham Reference Graham1994:80–110, Figure 3.9), which suggests that more than stone tools could be marketed as a result of GST manufacture. Although pottery preservation is said to have been poor in the western periphery of Pacbitun, indications are that the industrial workshops date to the Late Classic, and possibly a bit later based on some of the ceramics. This dating is consistent with the Late to Terminal Classic dating of Mayflower and Maintzunun.

Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues report that the Alabama site core developed during the Late to Terminal Classic, a time span characteristic of several sites along rivers and creeks east of the Maya Mountains. Inhabitants exploited the Cockscomb batholith, although via secondary sources. Massive slabs used as stelae and altars are reported, a phenomenon seen at other Stann Creek sites such as Mayflower, Maintzunun, and T’au Witz (Graham Reference Graham1994). Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues observe that there is little evidence in the Late to Terminal Classic periods for Cockscomb materials moving beyond the Stann Creek District, although this does not mean that GST were not produced and moved earlier. At Marco Gonzalez on Ambergris Caye, we have evidence for industrial salt production (brine hearths, special-purpose ceramics) in the Late Classic but not earlier or later (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Macphail, Turner, Crowther, Stegemann, Arroyo-Kalin, Duncan, Whittet, Rosique and Austin2017). This does not mean that the islanders stopped producing salt—salt was probably a critical export throughout Maya history. Evidence seems to be accumulating, however, like the evidence for GST production described in this Compact Section, for a major change in Maya economy in the Late Classic period that set conditions for intensive production that had not existed earlier or later.

The article by Schneider continues to pave the way for GST studies that I had not even imagined back in 1987. What more can we learn about the GST craft? Was it largely part-time, or did the attention devoted to GST fluctuate? Could households complete the production from preforms? Replicative experiments are important—should they be considered by more researchers? Were workshop locations associated with specific characteristics in a batholith? Can we hypothesize routes of transport? What made some types of stone preferable?

Where do we go from here?

Late Classic commerce

One result of the research reported in this Compact Section that stands out is that the granite workshops identified so far are predominantly Late Classic. Does this mean that GST were not made earlier? Obviously not, but why have earlier workshops not been found? I note above that we have a similar predicament on Ambergris Caye, where salt production is in evidence for the Late Classic at a scale that is above what one would expect for households and almost certainly entailed export to the mainland. People processed salt earlier and later, but the evidence for intensive processing points to the Late Classic (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Macphail, Turner, Crowther, Stegemann, Arroyo-Kalin, Duncan, Whittet, Rosique and Austin2017). Sometime toward the end of the Late Classic, intensive processing halted and attention focused (as in earlier periods) on coastal trade in various materials such as pottery and obsidian.

The attention given to intensive production of GST in the Late Classic may be indicative of a societal change that made it advantageous to specialize in various kinds of production. Production increases may reflect economic shifts that resulted from the fall of Teotihuacan (ca. a.d. 600), with lowland communities presented with commercial opportunities they either had not had or had not envisaged earlier. The expansion of salt production along the Belize coast and cayes in the Late Classic is an example. The hypothesis that commercial opportunities arose in the Late Classic that had not presented themselves earlier is worth testing by investigating changes in specialized production of other items such as ceramics, obsidian, or jade (e.g., Andrieu et al. Reference Andrieu, Rodas and Luin2014), which may in turn help make sense of the so-called Maya collapse, or at least the change to a Postclassic economy (Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, Torres, Foorné, Barrientos and Wolf2014:210). Thus, the manufacture, exchange, and trade in GST become critical in addressing the nature of the economy of the Late Classic and the role of Late Classic dynasts in creating conditions in which GST workshops flourished. Such conditions do not necessarily imply top-down control, with all decision-making attributable to a ruler or to elites. As I argued in an earlier publication, there is a way to control without controlling (Graham Reference Graham, Foias and Emery2012). A king—flush with the results of newly acquired wealth through marriage or conquest—might want to make sure his expanding household had ready access to manos and metates. Rulers and subordinate rulers would be keen on expanding marketplaces in their towns or cities—in Garraty’s terms (Reference Garraty, Garraty and Stark2010:6), a scalar increase in market participation. This might mean taxing the markets, but an increased presence of marketplaces encourages both local and widespread provisioning at all levels. As manos and metates are cross-class necessities, we might expect that an increase in markets or expansion of marketplaces would encourage production and distribution (via trade and exchange routes) of GST wherever the raw materials occur.

As Abramiuk (Reference Abramiuk2009) has argued for the Annexation period in Hawaii (a.d. 1650 to 1820), when chiefs were beginning to increase the resources which they wished to access, it was in chiefs’ best interest to “increase the rate of commoner resource extraction (production), the rate at which these resources [were] transferred from the commoners to the elite, and the total amount of material resources to which the chief [had] access, and this is precisely what happened” (2009:89). We could hypothesize that those investing in granite GST production did so, as argued by Abramiuk for Hawaii, because it was in their best interest.

Granite products

Granite working can result not only in GST but in products used in construction, such as facing stones but also sand and gravel. Limestone is not present in most of the Stann Creek District, so making lime plaster for floors or walls requires importing material from afar or finding a substitute. Common at Maintzunun and Mayflower were floors made of gravel (decomposed granite), sand or clay, or combinations of these. Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues mention stelae and altars of granite, monuments that also occurred at Mayflower, T’au Witz and Maintzunun (Graham Reference Graham1994). It is almost as if settlers were mimicking what occurred at sites where limestone was abundant. At Kendal and the Silk Grass Creek sites, there is evidence that, in the absence of limestone, a white clay—naturally restricted but at least available—was used to cover the clay daub of a perishable building or the facing stones of a platform (1994:12, 80, 114–130, 323). Some sites may have been the result of Late Classic population expansion, as proposed by Peuramaki-Brown and colleagues, although this is not the case with Pacbitun, which has a deep history.

Granite products of critical importance are clay and clay minerals, which result from natural weathering of granites, although one wonders if they could also be manufacturing by-products. The rivers and streams that drain the eastern foothills of the Maya Mountains have extensive and deep clay deposits (Lefond and Roghani Reference Lefond and Roghani1976), which include minerals used by the Maya to make slips and paints. Some clays can be refined to produce the kinds of slips that respond to burnishing, but also the kinds, such as kaolinite, that can be used in the production of polychromes, which are not burnished but produce a gloss (Graham Reference Graham1994:139–140). A study of a particular drainage area might yield information on the mining of a particular kind of clay, or the local abundance of a particular mineral.

Production

Learning about the kinds of tools used to produce manos and metates (Spenard and colleagues; King and Powis, both this section) got me thinking about whether the odd-shaped granite pieces found at various sites could be tools. At Marco Gonzalez we find chunks of granite and other rocks from the Maya Mountains. I do not recollect that any resemble loaves or half-loaves, but a closer look is warranted. It is hard to explain why the Maya would transport chunks of rock that do not conform to standardized shapes. On the other hand, Schneider (this section) citing Hayden (Reference Hayden and Hayden1987) notes that rough tool shapes could be transported from quarry sources to domestic environments for finishing. Could our rocks represent metate or mano preforms that were brought to the island as raw material and finished at Marco Gonzalez?

Heirlooms

My last thought has to do with the life of manos and metates. Schneider (this section) emphasizes the importance of visiting modern Maya households to discover the extent to which manos or metates are heirlooms. If they are handed down, how many generations would it take before they wear out? Hayden’s (Reference Hayden and Hayden1987) research on modern metate manufacturing in Guatemala found that metates could last 30 years. My husband and I use cast iron cookware. Several pieces can be traced back to our grandmothers or our great-grandmothers, and we will pass them on to our sons. We archaeologists do not normally think of an object we recover being three or four generations old, yet a metate has this potential. Such length of use cannot be matched by chert tools. Pottery can bridge generations, although pottery is more fragile than ground stone. Along with the data from house mound surveys, we might be able to estimate the number of metates expected to be used over the years by households at a given location. Once a mano or metate disintegrates, however, the resulting gravel or debris may well have had another household use.

Maya economy

Ground stone tools, their manufacture and distribution, provide information of key importance in distinguishing directions of trade. Although trade routes surely involved a range of materials and objects, focusing on stone that can be sourced gives us a jump in proposing actual routes of trade (see also Wanyerka Reference Wanyerka2005). Such trade and exchange of objects also involved information exchange (Abramiuk Reference Abramiuk2005) and can almost certainly inform research on market development (Garraty Reference Garraty, Garraty and Stark2010:26–30). Once thought of as the humblest of objects, ground stone tools may turn out to provide key insight into Maya economy.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to the Belize Institute of Archaeology for supporting my research in Belize for so many years. Those who helped and supported the Stann Creek Project are numerous and acknowledged in Graham Reference Graham1994. Gordon Willey was kind enough to give me permission to sample the manos in the Peabody in the late 1970s. I remain forever thankful to the Colorado School of Mines researchers for sharing their knowledge. I also thank reviewers for their helpful comments. I could not accommodate all suggestions but they have pointed me in new directions.