Social network analysis has been applied to social problems in various fields, such as criminology, politics, and public health, for approximately 40 years (Azad & Devi, Reference Azad and Devi2020; Christakis & Fowler, Reference Christakis and Fowler2007; Valente, Reference Valente2010). It also has high relevance to the third sector and the need for people’s altruism for welfare in civil society (Martin et al., Reference Lee and Brudney2019; Plickert et al., Reference Pekkanen, Tsujinaka and Yamamoto2007). The volunteering literature shows that social networks, a significant source of connection among people, create the sort of value that social capital produces (Putnam, Reference Prouteau and Wolff1995, Reference Putnam2001) and that being asked by friends and others affects the experience of volunteering (Freeman, Reference Freeman1997; Independent Sector, Reference Rotolo, Wilson and Hughes2002). Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between a person’s social networks and likelihood of volunteering (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Forbes & Zampelli, Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014; Glanville et al., Reference Glanville, Paxton and Wang2016; Herzog & Yang, Reference Herzog and Yang2018; Lee & Brudney, Reference Lee and Brudney2012; Paik & Navarre-Jackson, Reference Okada, Ishida and Nakajima2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mook and Handy2017; Wilson & Son, Reference Wilson and Son2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhao, Zhang and Liu2018), although several studies have reported the opposite effect (McAdam & Paulsen, Reference Matsunaga1993; Wilson & Janoski, Reference Wilson and Janoski1995).

Regarding the interface with social networks, there are extensions from associational to personal networks. Participation with associational ties constitutes a traditional social network (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Forbes & Zampelli, Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014). On the other hand, as Paik and Navarre-Jackson (Reference Okada, Ishida and Nakajima2011) found, only network respondents gain personally. Nesbit (Reference McAdam and Paulsen2012) defined volunteering by family members as significant places of socialization that represent extended personal social networks. Glanville et al. (Reference Glanville, Paxton and Wang2016) explored region-based and individual-based social ties. Certainly, some authors have challenged the classification of social networks (Kawachi et al., Reference Kambayashi and Kato1997; Putnam, Reference Putnam2001; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mook and Handy2017). However, there is almost no consistency regarding networks except for associational ties. The literature has not resolved two aspects: first, the concept of “social networks” concerning volunteering; second, it remains unclear what kinds of social networks, with a particular focus on personal as well as associational social networks, nudge volunteering. This background suggests a need to analyze social networks in greater detail in a setting featuring a variety of social networks.

To fill the above two gaps, this study explores the correlation between organizational and personal social networks and volunteering based on unique Japanese data with various social network variables. This article is organized as follows: First, the author reviews the literature on social networks and volunteering and develops hypotheses on the Japanese case. The author then describes the dataset and methodology and conducts a descriptive analysis. Finally, after explaining the estimation results of the correlations between social networks and volunteering, the author presents and discusses the study’s implications and limitations.

Literature Review

Association Between Social Networks and Volunteering

Prior research has shown a positive correlation between social interaction with others and volunteering participation (Herzog & Yang, Reference Herzog and Yang2018; Nesbit, Reference McAdam and Paulsen2012; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Smith, Reference Smith2016; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997; Wilson & Son, Reference Wilson and Son2018). The social network concept has been broadened into formal participation in certain associations and other social networks. For instance, Brown and Ferris (Reference Brown and Ferris2007) stressed the importance of social capital, measured by an individual’s wealth of associational ties, in strengthening the nonprofit sector, categorizing an “individual’s trust and faith in others” and “civic institutions” as forms of norm-based social capital and one’s “involvement in formal groups,” “community leadership,” and “protest politics” as forms of network-based social capital. Forbes and Zampelli (Reference Forbes and Zampelli2014) used two variables to represent social networks, in addition to trust variables, and examine social capital: formal group involvement and informal social networks. More formal group involvement and informal social networks thus increase the likelihood and level of volunteering. Glanville et al. (Reference Glanville, Paxton and Wang2016) considered “trust,” “social ties,” and “children in household” elements of social capital, particularly “social ties,” measured at the individual and regional levels, given that social capital at the regional level—lower than the country level—reflects the nature of social relations within the locality and thereby affects individual generosity. Hence, individual-level social ties positively correlate with volunteering, while regional-level social ties do not. Paik and Navarre-Jackson (Reference Okada, Ishida and Nakajima2011) consider “the number (diversity) of personal networks” an informal social tie indicator and conclude the percentage of individuals volunteering increases with social tie diversity.

Furthermore, social networks have been clearly categorized into formal or informal networks. Lee and Brudney (Reference Lee and Brudney2012) asserted that formal social networks are defined by, e.g., “church membership” or “membership in secular organizations” and that individual social relations such as “being employed,” “having children,” “being married,” and “being a homeowner” are forms of informal social networks, although they are not explicitly defined as such. Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Mook and Handy2017) consider formal social networks as the communities and associations that a person belongs to and participates in and the frequency that people interact with friends and their communities in their daily lives as an indicator of informal social networks.

The above studies indicate the following: First, informal social networks are recognized as a unified concept, while formal social networks tend to be defined in fixed terms, as participation in some formal religious or secular group or association. Second, there are a variety of indicators representing informal social networks, representing the accumulation of people’s social interaction in their daily lives. Variables that refer to being settled in a residence or directly refer to the number of social interactions are considered indicators of informal social networks.

Association Between Social Networks and Volunteering in Japan

Japan is a country where people have various social networks across multiple layers of their daily lives, such as their workplaces, schools, and neighborhoods. Each social network also has additional formal and informal communities. For example, unions' de facto power is expressed within Japanese firms' workplaces (Kambayashi & Kato, Reference Ishida and Okuyama2020). Schools often have “Bukatsudo,” extracurricular school clubs for students in addition to their school curricula (Blackwood & Friedman, Reference Blackwood and Friedman2015; Cave, Reference Cave2004). In people’s daily lives, neighborhood associations have subordinate circles, such as a “local women’s group” or “children’s group,” often related to more specific local associations, such as a “fire department” or “social welfare council” (Pekkanen et al., Reference Pekkanen, Tsujinaka, Coulmas, Conrad, Schad-Seifert and Vogt2014). These organizations are more open to community members than churches in Western countries. They also address issues and events related to social welfare and disaster prevention activities, such as disaster drills, through the spirit of mutual aid. Thus, various communities tend to have implicit/explicit ideas, such as obligations to people.

Volunteer activities did not suddenly appear following the Hanshin Awaji Earthquake in 1995; they first appeared before World War II. Milestones in volunteering appeared via Christian organizations, such as the Salvation Army in the Meiji Era and the rescue activities in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 in the Taisho Era (Imada, Reference Imada, Vinken, Nishimura, White and Deguchi2010). Nevertheless, it remains unclear what kinds of social networks have influenced volunteering in Japan.

Formal Social Networks in Japan

Neighborhood associations have provided public and administrative services such as arranging waste management and seasonal events with local people across Japan since World War II (Pekkanen, Reference Paik and Navarre-Jackson2006; Pekkanen et al., Reference Pekkanen, Tsujinaka, Coulmas, Conrad, Schad-Seifert and Vogt2014; Tiefenbach & Holdgrün, Reference Tiefenbach and Holdgrün2015). Although several studies have noted a decrease in neighborhood associations during the last 20 years and a gap in the participation rate between urban and rural areas (Nishide & Yamauchi, Reference Nesbit2005; Pekkanen & Tsujinaka, Reference Pekkanen2008), these associations continue to exist as face-to-face, traditional community organizations (Haddad, Reference Haddad2004; Ishida & Okuyama, 2015). Every neighborhood association tends to conduct extensive lobbying activities, such as consulting with senior officials in local government and petitioning the local assembly (Pekkanen et al., Reference Pekkanen, Tsujinaka, Coulmas, Conrad, Schad-Seifert and Vogt2014). They therefore represent a form of formal social network suited to the Japanese context.

In addition to their participation in neighborhood associations, Japanese people’s organizational memberships are noteworthy. Japanese people tend to have many group affiliations and to be highly engaged in in-group cooperation (Taniguchi, Reference Taniguchi2013; Taniguchi & Marshall, Reference Taniguchi and Marshall2014). Matsunaga (Reference Martin, Greiling and Leibetseder2007) captured this tradition with “affiliations with consumers’ cooperatives,” “citizens’ movement groups,” “religious groups,” and “sports clubs.” Therefore, “enrollment in a membership association” belongs to the formal social network category in Japan.

Thus, the author hypothesizes the following:

H1

Attending neighborhood association meetings is positively correlated with volunteering probability.

H2

Enrollment in a membership association is positively correlated with volunteering probability.

Informal Social Networks in Japan

There are positive associations between the years lived in the same place and volunteering opportunities (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007; Glanville et al., Reference Glanville, Paxton and Wang2016; Rotolo et al., Reference Putnam and Helliwell2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mook and Handy2017), as the years lived in the same place is a significant indicator of social interaction depth. Specifically, approximately 28% of males and 34% of females have lived in the same place for more than 20 years (Statistics Bureau & Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2010).

Interaction with friends can affect prosocial behavior (Prouteau & Wolff, Reference Plickert, Côté and Wellman2008; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1999). This idea has been proven in Japan. Moreover, Hommerich (Reference Hommerich2015) has shown that social trust is positively correlated with civic engagement, which is negatively correlated with a feeling of disconnectedness from society. Accordingly, there is likely an association between interaction with friends and volunteering.

Thus, the author hypothesizes the following:

H3

The years lived in the same place are positively correlated with volunteering probability.

H4

The frequency of meals with friends is positively correlated with volunteering probability.

Methods

Data

The Japan General Social Survey (JGSS), whose data are collected by Osaka University of Commerce, is a nationwide cross-sectional dataset that captures the daily behavior and life attitudes of males and females 20–89 years of age in Japan. The design of the questionnaire is based on the General Social Survey in the USA. It employs two-stage stratified random sampling by region and population size of cities/districts. The age and gender distribution of the sample is similar to that of the population. The highest age group (60–69 years old: approximately 21.0%) in this study resembles that (60–69 years old: approximately 17.5%) in the 2010 Census (ICPSR, 2015; Statistics Bureau & Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2010), and the gender ratio (women: 53.5%) is also similar to that (women: 51.3%) in the 2010 Census (ICPSR, 2016; Statistics Bureau & Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2010). Therefore, this study has prevented the sample selection issue.

This study uses data from the 2010 JGSS and 2012 JGSS because they are the most recent surveys with information on volunteering and include types thereof. They also contain information on social networks, such as “frequency of attending meetings of neighborhood associations,” “enrollment in a membership association,” “frequency of meals with friends,” and “years lived in the same place.” The valid sample size resulted in 3,938 observations: 2,034 observations in 2010 and 1,904 observations in 2012 (ICPSR, 2015). The response rates were 45.2% (2034 of 4500) in 2010 and 42.3% (1904 of 4500) in 2012 (ICPSR, 2016). The margin of error is 2.0% at the 99% confidence level.

This study uses a binary logistic regression model in STATA/SE 16.1. The dependent variables are binary to measure whether the respondents participated in volunteering in the last 12 months, with 1 being yes and 0 no.

Variables

Dependent Variables

There are six dependent variables including five types of volunteering: “volunteering for town improvement,” “volunteering for the protection of nature and the environment,” “volunteering for safety,” “volunteering for sports, culture, art and research,” “volunteering for children,” and “any volunteering.” “Any volunteering” is a variable representing volunteer activities in at least one of the above five volunteering categories. While the 2010 JGSS and 2012 JGSS do not clearly distinguish between formal and informal volunteering, in this dataset, volunteering plainly refers to an altruistic investment of time, excluding activities driven by neighborhood associations.

Volunteering for town improvement is a variable representing volunteer activity for community development, such as cleaning up streets, parks, and other places; planting flowers on the street; and revitalizing towns and other areas. Volunteering for the protection of nature and the environment is a variable reflecting volunteer activity to protect nature and the environment, such as protecting forests and green spaces, recycling activities, and reducing waste. Volunteering for safety is a variable representing volunteer activity for safety, such as security patrols, disaster prevention, and traffic safety campaigns. Volunteering for sports, culture, arts, and research is a variable representing volunteer activity for sports, culture, arts, and research, such as coaching sports, spreading education and culture, and sharing knowledge and skills. Volunteering for children is a variable reflecting volunteer activity for children, such as organizing and caring for local children, providing childcare support, and offering telephone consultation to bullied children.

Independent Variables

In this study, social networks are divided into formal and informal social networks. In the formal social network category, the frequency of attending neighborhood association meetings is measured with a single item assessing the frequency of participation in activities associated with neighborhood associations and/or a self-governing body. The responses range from 1 (= almost every week) to 6 (= never). Enrollment in a membership association is a binary variable reflecting enrollment in a political association, trade association, social service group, citizen movement, religious group, hobby group, or cooperative society (1 = yes; 0 = no). Regarding informal social networks, the years lived in the same place is measured with a single item assessing the number of years a person has lived there. Responses are given on a scale from 1 (= since I was born) to 8 (= for 30 years or more). The frequency of meals with friends is measured with a single item assessing the frequency of seeing and dining with friends. Responses are given on a scale from 1 (= more than several times a week) to 6 (= never).

The control variables include human capital, such as education; socioeconomic status, such as work status and annual income; and demographic status, such as age, sex, marriage, size of hometown, type of residence, and year. Details on the control variables are presented in Table 1.

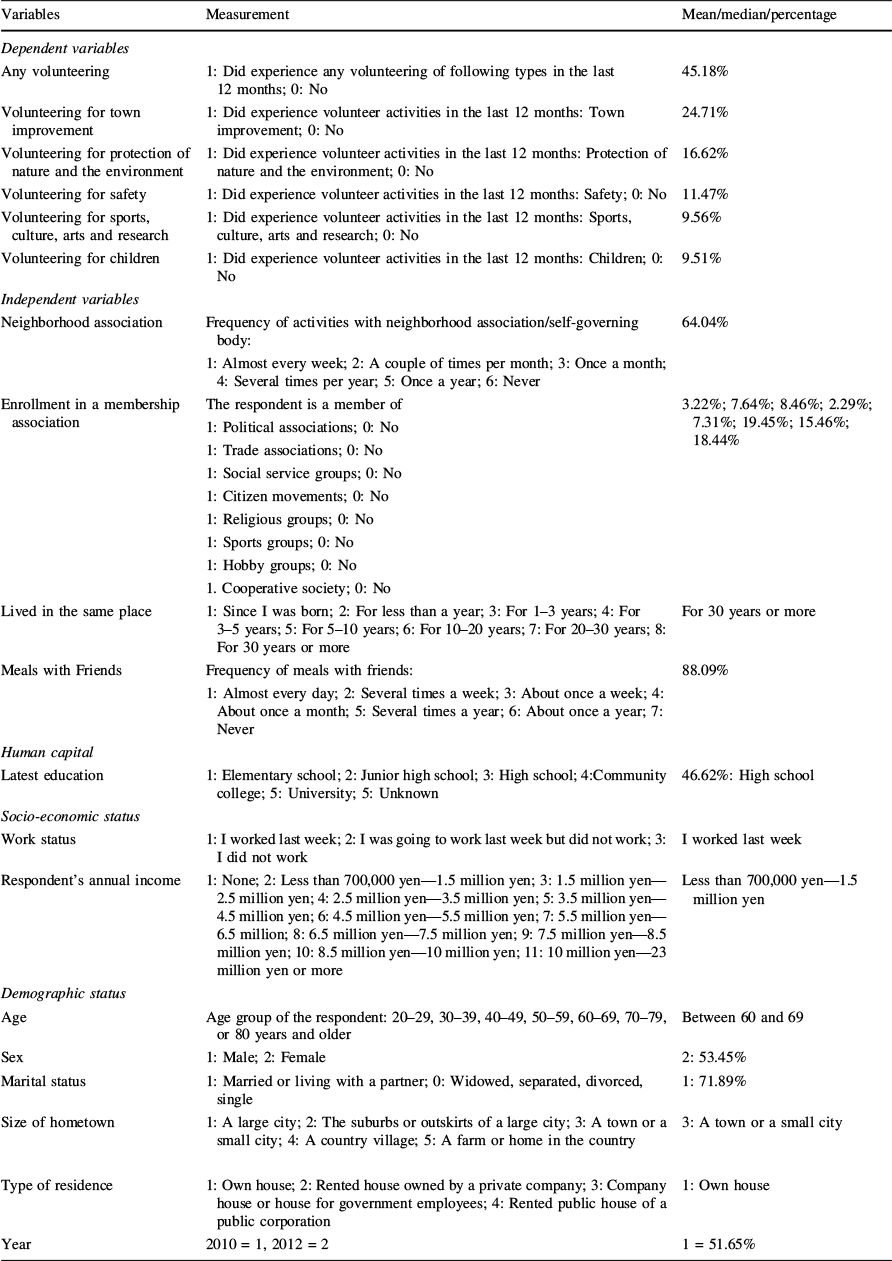

Table 1 Variable measurements and descriptive statistics (N = 3,938)

Variables |

Measurement |

Mean/median/percentage |

|---|---|---|

Dependent variables |

||

Any volunteering |

1: Did experience any volunteering of following types in the last 12 months; 0: No |

45.18% |

Volunteering for town improvement |

1: Did experience volunteer activities in the last 12 months: Town improvement; 0: No |

24.71% |

Volunteering for protection of nature and the environment |

1: Did experience volunteer activities in the last 12 months: Protection of nature and the environment; 0: No |

16.62% |

Volunteering for safety |

1: Did experience volunteer activities in the last 12 months: Safety; 0: No |

11.47% |

Volunteering for sports, culture, arts and research |

1: Did experience volunteer activities in the last 12 months: Sports, culture, arts and research; 0: No |

9.56% |

Volunteering for children |

1: Did experience volunteer activities in the last 12 months: Children; 0: No |

9.51% |

Independent variables |

||

Neighborhood association |

Frequency of activities with neighborhood association/self-governing body: 1: Almost every week; 2: A couple of times per month; 3: Once a month; 4: Several times per year; 5: Once a year; 6: Never |

64.04% |

Enrollment in a membership association |

The respondent is a member of 1: Political associations; 0: No 1: Trade associations; 0: No 1: Social service groups; 0: No 1: Citizen movements; 0: No 1: Religious groups; 0: No 1: Sports groups; 0: No 1: Hobby groups; 0: No 1. Cooperative society; 0: No |

3.22%; 7.64%; 8.46%; 2.29%; 7.31%; 19.45%; 15.46%; 18.44% |

Lived in the same place |

1: Since I was born; 2: For less than a year; 3: For 1–3 years; 4: For 3–5 years; 5: For 5–10 years; 6: For 10–20 years; 7: For 20–30 years; 8: For 30 years or more |

For 30 years or more |

Meals with Friends |

Frequency of meals with friends: 1: Almost every day; 2: Several times a week; 3: About once a week; 4: About once a month; 5: Several times a year; 6: About once a year; 7: Never |

88.09% |

Human capital |

||

Latest education |

1: Elementary school; 2: Junior high school; 3: High school; 4:Community college; 5: University; 5: Unknown |

46.62%: High school |

Socio-economic status |

||

Work status |

1: I worked last week; 2: I was going to work last week but did not work; 3: I did not work |

I worked last week |

Respondent's annual income |

1: None; 2: Less than 700,000 yen—1.5 million yen; 3: 1.5 million yen—2.5 million yen; 4: 2.5 million yen—3.5 million yen; 5: 3.5 million yen—4.5 million yen; 6: 4.5 million yen—5.5 million yen; 7: 5.5 million yen—6.5 million; 8: 6.5 million yen—7.5 million yen; 9: 7.5 million yen—8.5 million yen; 10: 8.5 million yen—10 million yen; 11: 10 million yen—23 million yen or more |

Less than 700,000 yen—1.5 million yen |

Demographic status |

||

Age |

Age group of the respondent: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, or 80 years and older |

Between 60 and 69 |

Sex |

1: Male; 2: Female |

2: 53.45% |

Marital status |

1: Married or living with a partner; 0: Widowed, separated, divorced, single |

1: 71.89% |

Size of hometown |

1: A large city; 2: The suburbs or outskirts of a large city; 3: A town or a small city; 4: A country village; 5: A farm or home in the country |

3: A town or a small city |

Type of residence |

1: Own house; 2: Rented house owned by a private company; 3: Company house or house for government employees; 4: Rented public house of a public corporation |

1: Own house |

Year |

2010 = 1, 2012 = 2 |

1 = 51.65% |

Findings

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the focal variables. Approximately 45% of the respondents in the 2010 and 2012 JGSS had performed at least one type of volunteer activity for an organization in the last 12 months. The percentage of volunteering in the survey was higher than that in the 2011 Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities (26.3%) (Statistics Bureau & Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2011). This measurement gap occurred because of a difference in survey design related to the question about “volunteering” between surveys. In Questionnaire A in the 2011 Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities, respondents were asked whether they had volunteered in the last 12 months because volunteering is considered one of the people’s main activities in their free time after primary and secondary activities. The minimum answer was “one to four days.” Short-term volunteering of less than one day was not counted by either survey. Nor did the 2010 or 2012 JGSS inquire about the setting or time constraints; they simply asked respondents whether they had volunteered in the last 12 months, regardless of intensity.

Regarding the details for each type of volunteering, 24.7% of the respondents had volunteered to improve their town in the last 12 months; 16.6% to protect nature and the environment; 11.5% for safety; 9.6% for sports, culture, arts, and research; and 9.5% for children.

Regarding formal social networks, 64.0% of the respondents had attended neighborhood association meetings, but 36.0% had not. Among the former, the largest portion (33.1%) had attended several times that year. Regarding participation in membership associations as another form of formal network, the largest portion of the respondents belonged to sports groups and clubs (19.5%), the second largest to cooperative associations (18.4%), and the third largest to hobby groups (15.5%). Citizen movements (2.3%) represented the smallest portion, political associations (3.2%) the second smallest, and religious groups (7.3%) the third smallest.

Regarding informal social networks, the largest portion (41.2%) of the respondents had lived in the same place for 30 years or more. A total of 76.8% of the respondents had been living in the same place for more than 10 years. Concerning the final informal social network indicator, 88.1% of the respondents had eaten meals with friends, while 11.9% had not. Among the respondents who had, the largest portion (32.0%) had eaten with friends several times that year.

Regarding human capital, 46.6% of the respondents had a high school education. Regarding socioeconomic status, 63.5% had not worked within the previous week. The median income of the respondents was less than 700,000–1.5 million yen. Regarding demographic status, the median age of the respondents was between 60 and 69, and 46.6% were males. A total of 71.9% of the respondents were married or had a partner. Finally, 43.1% lived in a town or a small city, while 79.9% of the respondents owned their own home.

Estimation Results

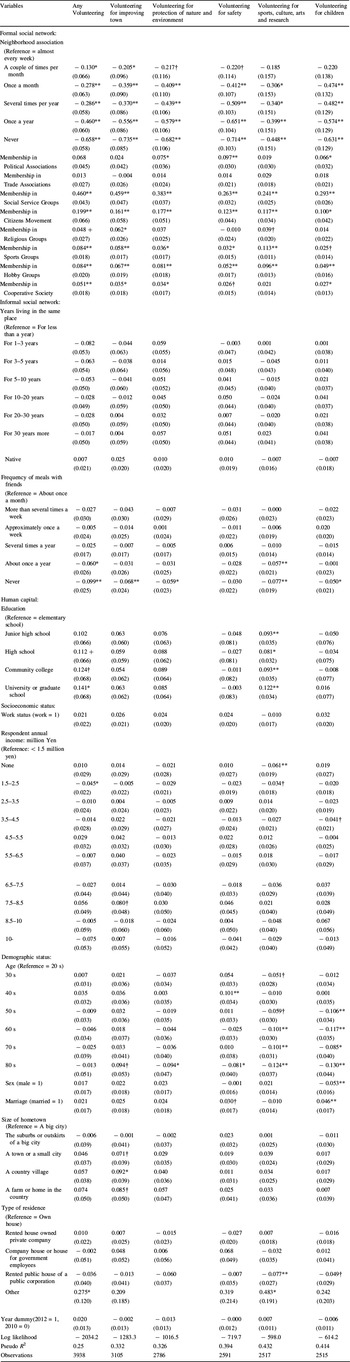

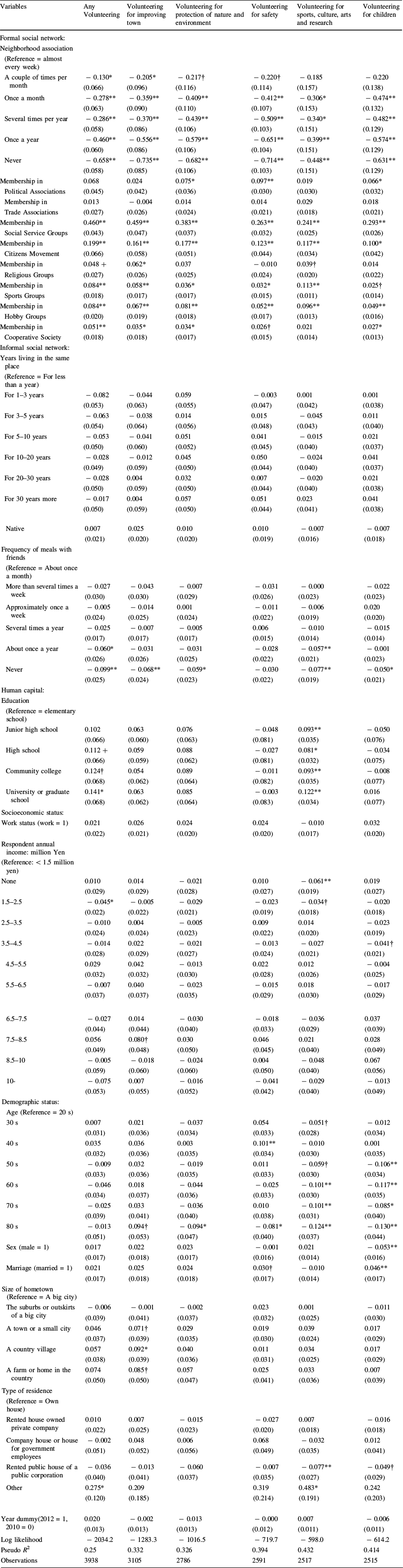

Table 2 presents each independent variable's marginal effects (dy/dx) because this study concerns the effect of an incremental change in X on the change in Y’s probability being 1. Regarding the dependent variables, namely, any volunteering and the five kinds thereof, the reference group of each estimation comprises those who did not volunteer. Notably, the sample size differs across the estimations, as this is a comparison between those who did not volunteer and those who engaged in one type of volunteering.

Table 2 Logistic regression results and marginal effects

Variables |

Any Volunteering |

Volunteering for improving town |

Volunteering for protection of nature and environment |

Volunteering for safety |

Volunteering for sports, culture, arts and research |

Volunteering for children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Formal social network: |

||||||

Neighborhood association (Reference = almost every week) |

||||||

A couple of times per month |

− 0.130* |

− 0.205* |

− 0.217† |

− 0.220† |

− 0.185 |

− 0.220 |

(0.066) |

(0.096) |

(0.116) |

(0.114) |

(0.157) |

(0.138) |

|

Once a month |

− 0.278** |

− 0.359** |

− 0.409** |

− 0.412** |

− 0.306* |

− 0.474** |

(0.063) |

(0.090) |

(0.110) |

(0.107) |

(0.153) |

(0.132) |

|

Several times per year |

− 0.286** |

− 0.370** |

− 0.439** |

− 0.509** |

− 0.340* |

− 0.482** |

(0.058) |

(0.086) |

(0.106) |

(0.103) |

(0.151) |

(0.129) |

|

Once a year |

− 0.460** |

− 0.556** |

− 0.579** |

− 0.651** |

− 0.399** |

− 0.574** |

(0.060) |

(0.086) |

(0.106) |

(0.104) |

(0.151) |

(0.129) |

|

Never |

− 0.658** |

− 0.735** |

− 0.682** |

− 0.714** |

− 0.448** |

− 0.631** |

(0.058) |

(0.085) |

(0.106) |

(0.103) |

(0.151) |

(0.129) |

|

Membership in Political Associations |

0.068 |

0.024 |

0.075* |

0.097** |

0.019 |

0.066* |

(0.045) |

(0.042) |

(0.036) |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

(0.032) |

|

Membership in Trade Associations |

0.013 |

− 0.004 |

0.014 |

0.014 |

0.029 |

0.018 |

(0.027) |

(0.026) |

(0.024) |

(0.021) |

(0.018) |

(0.021) |

|

Membership in Social Service Groups |

0.460** |

0.459** |

0.383** |

0.263** |

0.241** |

0.293** |

(0.043) |

(0.047) |

(0.037) |

(0.032) |

(0.025) |

(0.026) |

|

Membership in Citizens Movement |

0.199** |

0.161** |

0.177** |

0.123** |

0.117** |

0.100* |

(0.066) |

(0.058) |

(0.051) |

(0.044) |

(0.034) |

(0.042) |

|

Membership in Religious Groups |

0.048 + |

0.062* |

0.037 |

− 0.010 |

0.039† |

0.014 |

(0.027) |

(0.026) |

(0.025) |

(0.024) |

(0.020) |

(0.022) |

|

Membership in Sports Groups |

0.084** |

0.058** |

0.036* |

0.032* |

0.113** |

0.025† |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

(0.017) |

(0.015) |

(0.011) |

(0.014) |

|

Membership in Hobby Groups |

0.084** |

0.067** |

0.081** |

0.052** |

0.096** |

0.049** |

(0.020) |

(0.019) |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

(0.013) |

(0.016) |

|

Membership in Cooperative Society |

0.051** |

0.035* |

0.034* |

0.026† |

0.021 |

0.027* |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

(0.015) |

(0.014) |

(0.013) |

|

Informal social network: Years living in the same place (Reference = For less than a year) |

||||||

For 1–3 years |

− 0.082 |

− 0.044 |

0.059 |

− 0.003 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

(0.053) |

(0.063) |

(0.055) |

(0.047) |

(0.042) |

(0.038) |

|

For 3–5 years |

− 0.063 |

− 0.038 |

0.014 |

0.015 |

− 0.045 |

0.011 |

(0.054) |

(0.064) |

(0.056) |

(0.048) |

(0.043) |

(0.040) |

|

For 5–10 years |

− 0.053 |

− 0.041 |

0.051 |

0.041 |

− 0.015 |

0.021 |

(0.050) |

(0.060) |

(0.052) |

(0.045) |

(0.040) |

(0.037) |

|

For 10–20 years |

− 0.028 |

− 0.012 |

0.045 |

0.050 |

− 0.024 |

0.041 |

(0.049) |

(0.059) |

(0.050) |

(0.044) |

(0.040) |

(0.037) |

|

For 20–30 years |

− 0.028 |

0.004 |

0.032 |

0.007 |

− 0.020 |

0.021 |

(0.050) |

(0.059) |

(0.050) |

(0.044) |

(0.040) |

(0.038) |

|

For 30 years more |

− 0.017 |

0.004 |

0.057 |

0.051 |

0.023 |

0.041 |

(0.050) |

(0.059) |

(0.050) |

(0.044) |

(0.041) |

(0.038) |

|

Native |

0.007 |

0.025 |

0.010 |

0.010 |

− 0.007 |

− 0.007 |

(0.021) |

(0.020) |

(0.020) |

(0.019) |

(0.016) |

(0.018) |

|

Frequency of meals with friends (Reference = About once a month) |

||||||

More than several times a week |

− 0.027 |

− 0.043 |

− 0.007 |

− 0.031 |

− 0.000 |

− 0.022 |

(0.030) |

(0.030) |

(0.029) |

(0.026) |

(0.023) |

(0.023) |

|

Approximately once a week |

− 0.005 |

− 0.014 |

0.001 |

− 0.011 |

− 0.006 |

0.020 |

(0.024) |

(0.025) |

(0.024) |

(0.022) |

(0.019) |

(0.020) |

|

Several times a year |

− 0.025 |

− 0.007 |

− 0.005 |

0.006 |

− 0.010 |

− 0.015 |

(0.017) |

(0.017) |

(0.017) |

(0.015) |

(0.014) |

(0.014) |

|

About once a year |

− 0.060* |

− 0.031 |

− 0.031 |

− 0.028 |

− 0.057** |

− 0.001 |

(0.026) |

(0.026) |

(0.025) |

(0.022) |

(0.021) |

(0.023) |

|

Never |

− 0.099** |

− 0.068** |

− 0.059* |

− 0.030 |

− 0.077** |

− 0.050* |

(0.025) |

(0.024) |

(0.023) |

(0.022) |

(0.019) |

(0.021) |

|

Human capital: Education (Reference = elementary school) |

||||||

Junior high school |

0.102 |

0.063 |

0.076 |

− 0.048 |

0.093** |

− 0.050 |

(0.066) |

(0.060) |

(0.063) |

(0.081) |

(0.035) |

(0.076) |

|

High school |

0.112 + |

0.059 |

0.088 |

− 0.027 |

0.081* |

− 0.034 |

(0.066) |

(0.059) |

(0.062) |

(0.081) |

(0.032) |

(0.075) |

|

Community college |

0.124† |

0.054 |

0.089 |

− 0.011 |

0.093** |

− 0.008 |

(0.068) |

(0.062) |

(0.064) |

(0.082) |

(0.035) |

(0.077) |

|

University or graduate school |

0.141* |

0.063 |

0.085 |

− 0.003 |

0.122** |

0.016 |

(0.068) |

(0.062) |

(0.064) |

(0.083) |

(0.034) |

(0.077) |

|

Socioeconomic status: |

||||||

Work status (work = 1) |

0.021 |

0.026 |

0.024 |

0.024 |

− 0.010 |

0.032 |

(0.022) |

(0.021) |

(0.020) |

(0.020) |

(0.017) |

(0.020) |

|

Respondent annual income: million Yen (Reference: < 1.5 million yen) |

||||||

None |

0.010 |

0.014 |

− 0.021 |

0.010 |

− 0.061** |

0.019 |

(0.029) |

(0.029) |

(0.028) |

(0.027) |

(0.019) |

(0.027) |

|

1.5–2.5 |

− 0.045* |

− 0.005 |

− 0.029 |

− 0.023 |

− 0.034† |

− 0.020 |

(0.022) |

(0.022) |

(0.021) |

(0.019) |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

|

2.5–3.5 |

− 0.010 |

0.004 |

− 0.005 |

0.009 |

0.014 |

− 0.023 |

(0.024) |

(0.024) |

(0.023) |

(0.022) |

(0.020) |

(0.019) |

|

3.5–4.5 |

− 0.014 |

0.022 |

− 0.021 |

− 0.013 |

− 0.027 |

− 0.041† |

(0.028) |

(0.029) |

(0.027) |

(0.024) |

(0.021) |

(0.021) |

|

4.5–5.5 |

0.029 |

0.042 |

− 0.013 |

0.022 |

0.012 |

− 0.004 |

(0.032) |

(0.032) |

(0.030) |

(0.028) |

(0.026) |

(0.025) |

|

5.5–6.5 |

− 0.007 |

0.040 |

− 0.023 |

− 0.015 |

0.018 |

− 0.017 |

(0.037) |

(0.037) |

(0.035) |

(0.029) |

(0.030) |

(0.029) |

|

6.5–7.5 |

− 0.027 |

0.014 |

− 0.030 |

− 0.018 |

− 0.036 |

0.037 |

(0.044) |

(0.044) |

(0.040) |

(0.033) |

(0.029) |

(0.039) |

|

7.5–8.5 |

0.056 |

0.080† |

0.030 |

0.046 |

0.021 |

0.028 |

(0.049) |

(0.048) |

(0.050) |

(0.045) |

(0.040) |

(0.049) |

|

8.5–10 |

− 0.005 |

− 0.018 |

− 0.024 |

0.004 |

− 0.048 |

0.067 |

(0.059) |

(0.060) |

(0.060) |

(0.050) |

(0.040) |

(0.056) |

|

10- |

− 0.075 |

0.007 |

− 0.016 |

− 0.041 |

− 0.029 |

− 0.013 |

(0.053) |

(0.055) |

(0.052) |

(0.042) |

(0.040) |

(0.049) |

|

Demographic status: Age (Reference = 20 s) |

||||||

30 s |

0.007 |

0.021 |

− 0.037 |

0.054 |

− 0.051† |

− 0.012 |

(0.031) |

(0.036) |

(0.034) |

(0.033) |

(0.028) |

(0.034) |

|

40 s |

0.035 |

0.036 |

0.003 |

0.101** |

− 0.010 |

0.001 |

(0.032) |

(0.036) |

(0.035) |

(0.034) |

(0.030) |

(0.035) |

|

50 s |

− 0.009 |

0.032 |

− 0.019 |

0.011 |

− 0.059† |

− 0.106** |

(0.033) |

(0.036) |

(0.035) |

(0.033) |

(0.030) |

(0.034) |

|

60 s |

− 0.046 |

0.018 |

− 0.044 |

− 0.025 |

− 0.101** |

− 0.117** |

(0.034) |

(0.037) |

(0.036) |

(0.033) |

(0.030) |

(0.035) |

|

70 s |

− 0.025 |

0.033 |

− 0.036 |

0.010 |

− 0.101** |

− 0.085* |

(0.039) |

(0.041) |

(0.040) |

(0.038) |

(0.031) |

(0.040) |

|

80 s |

− 0.013 |

0.094† |

− 0.094* |

− 0.081* |

− 0.124** |

− 0.130** |

(0.051) |

(0.053) |

(0.047) |

(0.040) |

(0.037) |

(0.044) |

|

Sex (male = 1) |

0.017 |

0.022 |

0.023 |

− 0.001 |

0.021 |

− 0.053** |

(0.017) |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

(0.016) |

(0.014) |

(0.016) |

|

Marriage (married = 1) |

0.021 |

0.025 |

0.024 |

0.030† |

− 0.010 |

0.046** |

(0.017) |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

(0.017) |

(0.014) |

(0.017) |

|

Size of hometown (Reference = A big city) |

||||||

The suburbs or outskirts of a big city |

− 0.006 |

− 0.001 |

− 0.002 |

0.023 |

0.001 |

− 0.011 |

(0.039) |

(0.041) |

(0.037) |

(0.032) |

(0.025) |

(0.030) |

|

A town or a small city |

0.046 |

0.071† |

0.029 |

0.019 |

0.039 |

0.017 |

(0.037) |

(0.039) |

(0.035) |

(0.030) |

(0.024) |

(0.029) |

|

A country village |

0.057 |

0.092* |

0.040 |

0.011 |

0.034 |

0.017 |

(0.038) |

(0.039) |

(0.036) |

(0.031) |

(0.025) |

(0.029) |

|

A farm or home in the country |

0.074 |

0.085† |

0.057 |

0.025 |

0.033 |

0.007 |

(0.050) |

(0.050) |

(0.047) |

(0.041) |

(0.036) |

(0.039) |

|

Type of residence (Reference = Own house) |

||||||

Rented house owned private company |

0.010 |

0.007 |

− 0.015 |

− 0.027 |

0.007 |

− 0.016 |

(0.022) |

(0.025) |

(0.023) |

(0.020) |

(0.018) |

(0.018) |

|

Company house or house for government employees |

− 0.002 |

0.048 |

0.006 |

0.068 |

− 0.032 |

0.012 |

(0.051) |

(0.052) |

(0.056) |

(0.049) |

(0.035) |

(0.041) |

|

Rented public house of a public corporation |

− 0.036 |

− 0.013 |

− 0.060 |

− 0.007 |

− 0.077** |

− 0.049† |

(0.040) |

(0.041) |

(0.037) |

(0.035) |

(0.027) |

(0.029) |

|

Other |

0.275* |

0.209 |

0.319 |

0.483* |

0.242 |

|

(0.120) |

(0.185) |

(0.214) |

(0.191) |

(0.203) |

||

Year dummy(2012 = 1, 2010 = 0) |

0.020 |

− 0.002 |

− 0.013 |

− 0.000 |

0.007 |

− 0.006 |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.013) |

(0.012) |

(0.011) |

(0.011) |

|

Log likelihood |

− 2034.2 |

− 1283.3 |

− 1016.5 |

− 719.7 |

− 598.0 |

− 614.2 |

Pseudo R 2 |

0.25 |

0.332 |

0.326 |

0.394 |

0.432 |

0.414 |

Observations |

3938 |

3105 |

2786 |

2591 |

2517 |

2515 |

Standard errors in parentheses

**p < 0.01

*p < 0.05

†p < 0.1

Any volunteering explains approximately 25% of the variance in the likelihood of doing volunteer work. Regarding formal social networks, the effect of attending neighborhood association meetings on the likelihood of any volunteering approaches significance. Attendance thus increases volunteering likelihood. The probability of any volunteering decreases by approximately 13.0 percentage points (a couple of times per month), 27.8 percentage points (once a month), 28.6 percentage points (several times a year), 46.0 percentage points (once a year), and 65.8 percentage points (none) for the respondents compared to their counterparts (almost every day) (p < 0.05). These results therefore support Hypothesis 1.

Regarding enrollment in membership associations, another formal social network, membership in social service groups, citizen movements, sports groups, hobby groups, and cooperative societies are significant for engaging in any volunteering. The exception is membership in political groups or trade associations. Hence, these results fundamentally support Hypothesis 2.

However, an informal social network indicator, the years lived in the same place, does not affect any volunteering, even controlling for human capital, including education; socioeconomic status, including work status, income, and type of residence; and demographic status, including marriage, age, gender, size of hometown, and year. These findings thus do not support Hypothesis 3.

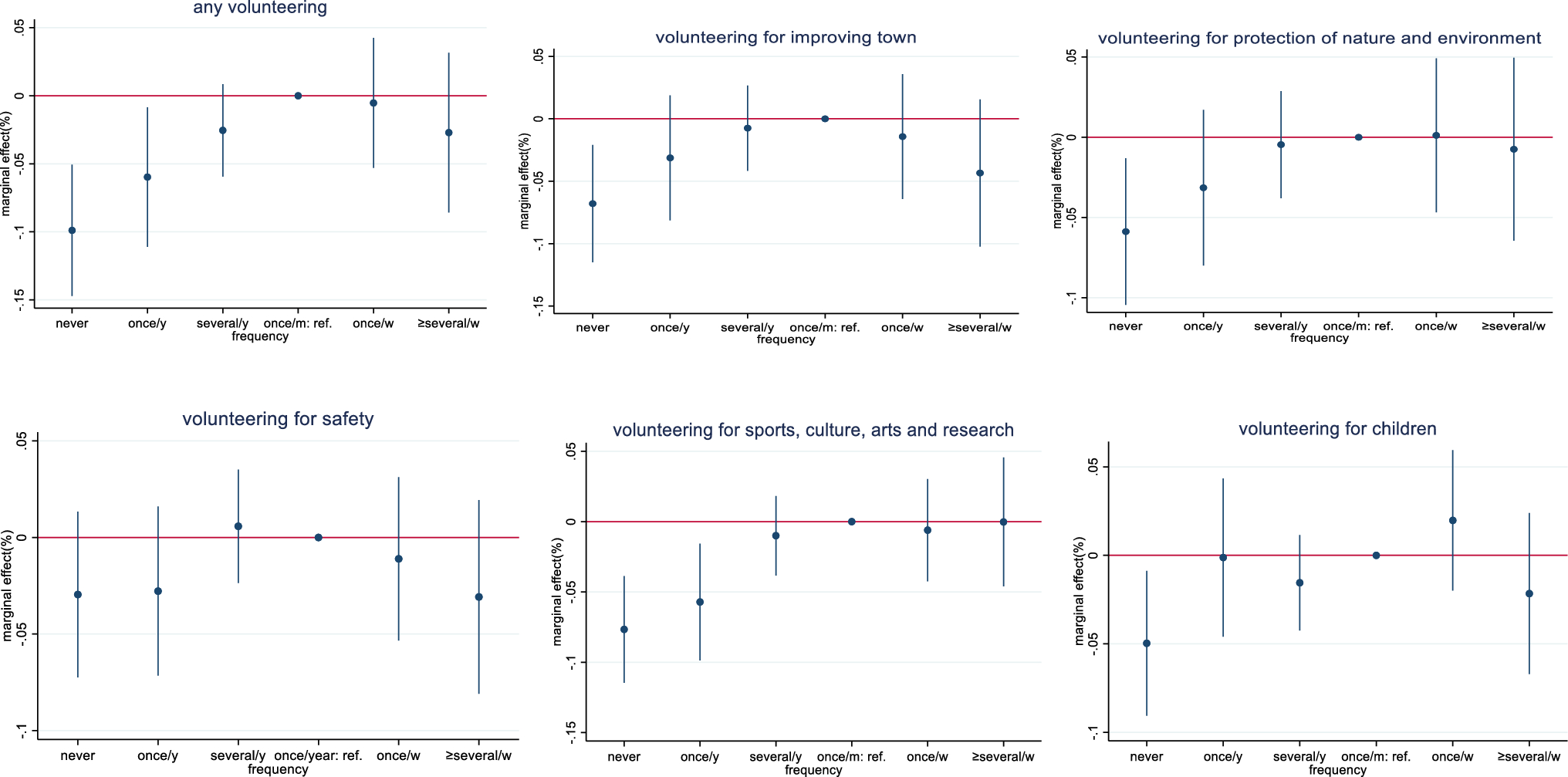

Regarding another informal social network, the frequency of meals with friends parameter impacts volunteering likelihood. The probability of any volunteering decreases by approximately 9.9 percentage points (never) and 6.0 percentage points (approximately once a year) for the respondents compared to their counterparts (approximately once a month) (p < 0.05). However, the probability of any volunteering does not affect the respondents (several times a year, approximately once a week, and more than several times a week) more than their counterparts (approximately once a month) (p < 0.05). This finding therefore partially supports Hypothesis 4 and is different from the fact that more frequent face-to-face interaction with friends increases volunteering, as clarified by Taniguchi (Reference Taniguchi2010).

Additional findings regarding the factors most likely to influence any volunteering and the types thereof are as follows: Regarding education as human capital, graduation from university or graduate school is significant for any volunteering, consistent with resource theory, which indicates that education enhances opportunities for volunteering because educated people generally recognize social problems better, have more empathy for others, and organize more meetings (Einolf & Chambré, Reference Einolf and Chambré2011; Gesthuizen & Scheepers, Reference Gesthuizen and Scheepers2012; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Van den Brink and Groot2009; Putnam, Reference Prouteau and Wolff1995). Regarding socioeconomic status, work status is nonsignificant for any volunteering. Income is nonsignificant for any volunteering; nevertheless, respondents with an income of 1.5–2.5 million JPY were 4.5 percentage points less likely to do any volunteering than those earning under 1.5 million yen (p < 0.05). Previous research has shown that the effect of income is not linear (Lee & Brudney, 2009), and this study supports this observation.

Regarding demographic characteristics, age is not significant for any volunteering. Younger generations usually volunteer more than older generations because they have more leisure time. However, this survey lacks variables such as “employment status” or “family status.” Men are also less likely to volunteer for children than women, while having a partner has no significant effect on any volunteering. Finally, the year dummy (2010 = 0, 2012 = 1) is not significantly related to any volunteering or any of the five volunteer activities between 2010 and 2012.

Discussion and Implications

Contributing to research on social networks and volunteering, this study has affirmed that two formal types of social networks relate to engagement in volunteering and led to a novel finding that one type of informal social network is associated with volunteering. Below, the author interprets these results while revealing unique facets of Japanese people’s lives.

First, neighborhood associations are associated with “any volunteering,” specifically affecting the likelihood of “volunteering for improving towns” and “volunteering for safety.” This could be attributed to the effects of the series of earthquakes experienced in Japan. Japan relied on citizen initiative during the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995 (Nishide & Yamauchi, Reference Nesbit2005). After this earthquake, a series of natural disasters occurred, including the Niigata Prefecture earthquakes in 2004 and 2007 and the Iwate and Miyagi Prefecture earthquakes in 2008. The power of the community has certainly become useful in emergencies in Japan. Specifically, volunteer work for town improvement and safety addresses urgent needs in refugees’ daily lives when a natural disaster occurs. The strength of the community, through neighborhoods, proved effective when the government harnessed the power of local communities following the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 (Okada et al., Reference Nishide and Yamauchi2017). This development is similar to the increase in the rate of local-based volunteering after September 11, 2001, in the USA (Gazley & Brudney, Reference Gazley and Brudney2005). This series of natural disasters has emphasized the need for community, leading to altruistic behaviors within each community through neighborhood associations.

Moreover, a membership association is correlated with participation in volunteering. The volunteer work of Japanese people tends to be related to their daily lives. For instance, among the four types of membership association linked with volunteering, volunteering for town improvement occurs among participants who belong to associations and engage in activities with local people. Networking and collaboration with neighbors and their community is necessary to accomplish their mission. As Taniguchi and Kaufman (Reference Taniguchi and Kaufman2014) noted, Japanese people volunteer to maintain harmony in their communities. However, Japanese people may not be used to volunteering related to their jobs and industries or involving advocacy activities. Specifically, enrollment in political or trade associations, which engage with serious issues and strengthen networking among people with related interests, only enhances volunteering for “Volunteering for protection of nature and environment” and “Volunteering for safety.” In European countries, however, there is a positive association between civic participation and political engagement, based on longstanding research on socialization effects (school of democracy) and self-selection effects (pools of democracy) (Van der Meer and Van Ingen, Reference Van Ingen and van der Meer2009; van Ingen & van der Meer, Reference Van Ingen and van der Meer2016). Regarding Japanese political associations, interest groups influence policies in Japan (Tsujinaka & Pekkanen, Reference Tsujinaka and Pekkanen2007). However, interest groups tend to be narrowly focused on one policy area and agency, entailing the fragmentation and compartmentalization of the Japanese political system (Campbell, Reference Campbell1989). Regarding Japanese trade associations by industry, their purpose is to discuss current and future issues and take initiatives to develop their industry (Kikkawa et al., Reference Kawachi, Kennedy, Lochner and Prothrow-Stith2014). However, their role in policy making is usually limited (Campbell, Reference Campbell1989).

In Western countries, people who live in the same place longer typically volunteer due to their feeling of community attachment (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Mook and Handy2017). Japanese people tend to have different attitudes toward their setting. In external relationships, as people have a collectivist culture (Hagen & Choe, Reference Hagen and Choe1998), they monitor each other within a group (Yamagishi et al., Reference Yamagishi, Cook and Watabe1998). In closer relationships, they prefer “mutual profitable exchange” with neighbors, friends, or others (Coleman, Reference Coleman1990). Thus, informal social interactions within living areas lead to trust among friends and neighbors but not necessarily more personal outward interactions, including altruism.

Regarding the correlation between the frequency of meals with friends and volunteering, the ideas of Freeman (Reference Freeman1997) and Independent Sector (Reference Rotolo, Wilson and Hughes2002) apply to Asian as well as Western countries. The probability of volunteering among those who never have meals with friends decreases more than those who sometimes have meals with friends.

Moreover, there is a notable increase in this indicator, whose marginal effects are illustrated in Fig. 1. Based on the transition of confidence intervals, the greater number of meals with friends than the reference (approximately once a month) does not increase volunteering probability. This could also mean that the estimation point of approximately once a week and more than several times a week falls after the reference (approximately once a month). This therefore indicates that weak friendships could sufficiently drive volunteering but that strong friendships are not needed to create opportunities to volunteer. Japanese people maintain social relations with mutual assurance based on the nature thereof, hence the prominence of networks of committed relations, rather than based on mutual trust via a belief in human benevolence and in conservativeness when selecting long-term relationships with loyal partners rather than relationships with new partners (Yamagishi & Yamagishi, Reference Yamagishi and Yamagishi1994). Moreover, the average level of general trust, trust in others in general, is higher among Americans than among the Japanese (Yamagishi et al., Reference Yamagishi, Cook and Watabe1998). These characteristics not only support prior studies showing that social networks are not always significant for volunteering (McAdam & Paulsen, Reference Matsunaga1993; Wilson, Reference Wilson2000; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow2002) but also reveal a novel finding: The effect of “weak” ties, whereby Japanese people with a high frequency of meals with friends prioritize harmony with friends but do not always share new and personal information, such as volunteering with friends.

Fig. 1 Marginal effects of the frequency of meals with friends

This study has two policy implications. First, the author encourages those needing volunteers to strengthen the relationships among members of neighborhood associations. That is, neighborhood associations positively correlate with volunteering but living in the same place does not. This is key to including newcomers, such as foreigners or people who have recently moved in, and thereby improving public awareness of the need for and significance of community activities among all residents equally within the same community. Second, regarding friendship, as an informal social network, the results show that having friendships is significant for volunteering, regardless of frequency. The government has promoted policy regarding social isolation since the 2000s, reducing isolated situations and improving the lives of elderly people in superaging Japan (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Reference Kikkawa, Hirano, Itagaki and Okubo2000). Accordingly, this policy could be adjusted according to the above findings, i.e., by expanding the target age, implying more support for truancy, withdrawal, suicide, care givers, the working poor, homeless persons, and disabled individuals. Such adjustments would naturally increase the possibilities for volunteering among the population.

Conclusion

Recent studies have begun to assess volunteering through social network analysis, but they have left room for analyzing what kinds of social networks nudge volunteering. This study has revealed that involvement in neighborhood associations and membership associations, as formal social networks, and the frequency of meals with friends, indicative of informal social networks, are associated with volunteering. A novel finding is therefore that friendships are effective for volunteering, which could be stimulated via more opportunities for information sharing in more friendly situations.

This study should be interpreted with some caution. First, this research used cross-sectional data; future research could employ a longitudinal design to strengthen the association between social networks and volunteering. Second, this study did not include job or household variables; future research could focus more closely on demographic and socioeconomic status, which may affect formal and informal social networks. Third, this study did not include the number of hours spent volunteering; future research could attempt to estimate the intensity of volunteering. Fourth, future research should incorporate qualitative analysis to deepen the association between friendship and volunteering.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Beth Gazley and Prof. Carolyn Cordery for their constructive advice and suggestions. The author is also thankful for Dr. Naoto Yamauchi, Prof. Yu Ishida, Prof. Aya Okada, participants at the poster session at ARNOVA’s 47th annual conference, and all members of the Social Sector Workshop for their fruitful comments and advice. The author would also like to thank the journal editors and reviewers for their support and insightful comments that has made this paper possible. The views and opinions expressed by the author in this publication are provided in her personal capacity and are her sole responsibility.

Author Contributions

MK helped in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, resources, supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K01550.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest were present at the time of writing. This paper adheres to and complies with COPE policies and guidelines.