Introduction

Mobile sports betting is a new and growing phenomenon in the US (Reyes Reference Reyes2024), and everything that could make someone more likely to gamble accurately describes a soldier (high-stress levels, isolation and boredom, financial incentives, psychological behaviors, etc). In dayrooms, barracks, bars, and homes around the world, soldiers are watching, and recently in greater numbers, streaming sporting events. During these hours of enjoyment, advertisers attempt to influence soldiers’ behavior on what to consume. The list includes beverage companies (Coca Cola, Pepsi, Gatorade, and Powerade), apparel lines (Adidas and Nike), car manufacturers (Toyota and Ford), and, of course, the alcoholic beverage and spirits industry (Bud Light, Michelob, and Budweiser) (Beren, Reference Beren2024). Recently, however, a new entrant to the sports advertising space has emerged: gambling, which encourages consumption of something that could possibly have significant negative effects on soldiers.

Gambling-related ads have come to dominate live sports broadcasts, with sports fans encountering gambling messages as often as three times a minute (McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2025). This exposure has helped fuel the rise of mobile sports betting, transforming the landscape of gambling, making sports betting more accessible than ever. And while this presents opportunities for entertainment and potential profit, it also poses significant threats to the financial well-being of military personnel and ultimately unit readiness. Former Secretary of Defense Austin asserted that service member and family economic security is a priority when he stated that “[o]ur people and our readiness remain inextricably linked” (2021). This report explores new findings and early research about the rise of mobile sport betting and the risks it poses for soldiers, including the potential to exacerbate financial instability, addiction, and broader mental health challenges.

This is a relevant topic for academic research, but also for personal finance education and for policy; it is critically important that those who serve the country stay financially secure and mentally healthy. In addition to overviewing the evidence on mobile sport betting, we will provide suggestions on how financial education, policy, and programs could help mitigate and prevent future problems.

The rise of mobile sports betting

In 2018, the Supreme Court repealed the ban on sports betting, leading to 38 states and Washington D.C. to legalize some form of sports gambling. Of these 38 states, 30 allow mobile sports betting. Many of these states are home to some of the Army’s largest posts, including Fort Bragg (NC), Fort Campbell (KY), Fort Carson (CO), Fort Riley (KS), and Fort Drum (NY).

With the legalization and rapid proliferation of mobile sports betting applications, millions of Americans, including military personnel, have access to online wagering platforms at any time of day. From DraftKings, FanDuel, BetMGM, Fanatics, ESPN Bet, and others, these companies inundate soldiers with easy ways to place bets. This accessibility can lead to problematic gambling behaviors, especially among vulnerable populations like soldiers who may experience stress, deployment-related challenges, and financial pressures.

This proliferation has resulted in the average number of users growing dramatically in a short period of time. For example, in 2023, DraftKings reported 3.5 million average monthly users, up from 1.5 million at the end of 2022, while FanDuel reported 2.5 million average monthly users during the same period (Gambling Addiction Hotlines, 2024). While it is difficult to determine the exact number of soldiers in the reported users, a recent St. Bonaventure/Siena Research survey estimates that almost 1 in 5 Americans have an online sports betting account (2024). Assuming the force is the representative of the American public, this could mean nearly 100,000 of the 461,000 active-duty soldiers could have accounts, not to mention a similar number for the Army National Guard and Army Reserves, whose numbers total 500,000 in service.

The large Army posts mentioned above are also heavily populated with young, enlisted soldiers, with 71% of enlisted soldiers between the ages of 18-30. According to the website www.mobilebettingsite.com, which helps users find the best mobile betting app, about 14% of their respondents’ ages 18 to 29 state that they bet on sports. Of the same respondents, 20% of males state that they participate in sports betting, compared to just 7% of females. This is an important finding given that the Army enlisted population is 83% male (“Best Betting Apps For Your Phone 2024 | Mobile Betting Site” 2021).

Unfortunately, this is even a lower bound to the number of soldiers participating in this activity. A 2021 CivicScience survey found that 53% of Americans aged 21 to 29 bet on sports online, greatly increasing the numbers estimated above (Brode Reference Brode2021). There is little reason to think that the forces in this category are radically different from their civilian peers. Their participation in this activity is just another threat to the well-being of those who serve.

Vulnerable population

A reason to focus on soldiers is that they are a risk-seeking population, engaging in high-risk activities, and seeking challenges to benefit the Army mission (Arif et al. Reference Arif, Hoopsick, Lynn Homish and Homish2024). Research on the value of statistical life (VSL), the willingness to trade-off wealth and mortality risk, shows soldiers require less compensation to take risk than their U.S. civilian counterparts (Greenberg et al., n.d., Reference Greenberg2021). This translates to soldiers willing to pay less to reduce their chance of dying in a given year, effectively quantifying a higher risk threshold (Robinson, Reference Robinsonn.d., 2021)Footnote 1 . In other words, soldiers are more tolerant of risk, a feature that may make them more susceptible to gambling online (van der Maas and Nower 2021).

Moreover, soldiers, especially the young ones and those in lower ranks or with limited financial education, may face financial instability. This instability can make them more susceptible to gambling as a means of quick financial gain. In addition, soldiers may be drawn to sports betting during their off-duty hours or when deployed, as a way to relieve stress or pass the time. The combination of financial stress and the availability of easy betting options can make them particularly vulnerable. In addition, unlike a casino, mobile apps allow people to wager money directly from their bank accounts, and even more riskily, from personal credit cards. Finally, research has shown that soldiers can be prone to adverse peer effects, given the close-quarters lifestyle both on- and off-duty (Murphy, Reference Murphy2019), and so, a unit could be at risk from having just one influential prolific sports bettor within its ranks.

Although the legal gambling age is 18, addictive gambling disorder can be developed in younger, pre-enlisting persons. There has been a growing trend of teens gambling on websites using video games. For example, in “skin gambling,” teens exchanged virtual items on a game called Counter-Strike for on-site currency and placed bets (“‘It Ruined a Lot of Years of My Life.’ Teens and Young Adults Are Hooked on a Different Kind of Gambling.,” n.d.). Thus, over time, the Army is more likely to enlist young soldiers who may be already addicted to gambling, or at least, experienced gambling activities.

Gaming has become so prevalent that even affect work hours. Aguiar, Bils, Charles and Hurst (Reference Aguiar, Bils, Charles and Hurst.2017) documented that younger men, ages 21 to 30, exhibited a larger decline in work hours than older men or women. According to their estimates, innovations to gaming/recreational computing since 2004 explain on the order of half the increase in leisure for younger men. We cannot afford not to address this risk to soldiers’ personal economic security.

Mobile sports betting threat

Although there has not been a lot of research yet on the numbers of soldiers that gamble using mobile sports betting apps, with 81% of men considering themselves sports fans and 31% considering themselves avid fans (“New Siena/St. Bonaventure Survey Reveals: 70% of Americans Say They Are Sports Fans, Nearly Half Engage Daily or Several Times Every Week – Siena College Research Institute,” n.d.), the numbers are likely to be sizeable.Footnote 2 Young soldiers are being deluged with mobile sports betting advertisements, with over 20% of broadcast time during live events including references to sports gambling and 90% of gambling logos or references appearing on playing surfaces or rink-side area (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2025). With exposure so great, problems are likely to follow.

The National Council on Problem Gambling conservatively estimates that 4% of military personnel meet the criteria for moderate to severe gambling problems, which is twice the national average (Means Reference Means2022). A different study found that 4.2% of veterans indicated at-risk or probable pathological gambling post-deployment (Whiting et al. Reference Whiting, Potenza, Park, McKee, Mazure and Hoff2016). To further compound this threat, experts on problem gambling point out that particular aspects of online gambling can be more addictive than traditional gambling due to its easy accessibility and convenience (Health Reference Health2024). This may be due to gamblers viewing sports betting as less risky, given the availability of player statistics and team performance data. In contrast, the stock market is often seen as more complex and harder to analyze for the average person, making sports betting appear more accessible and less intimidating.

Before the advent of mobile sports betting, soldiers would largely be limited to gambling unless they were off post and off duty. Now, a soldier can place a bet in the motor pool, on the rifle range, or even before morning physical training with just a few taps on the phone. And despite having a Department of Defense (DoD) Memorandum governing the use of non-government owned mobile devices, it is hard to regulate the use, unlike a physical location in which a commander can place as off-limits. To use an analogy with health, we have a de facto new drug, but without any controls to mitigate its effects, and also without a study of its potential side effects.

Mobile apps allow for real-time in-game betting and continuous engagement, which can lead to impulsive decisions. Recent research on frequent sports bettors aimed to measure the impact of two biases, overoptimism about financial returns and self-control problems, on the demand for sports betting, supporting the threat of impulsive decision making (Brown et al. 2025). The authors assert that bettors may have self-control problems in that more is bet in the moment than would have likely been bet if they had chosen in advance. This is compounded by the fact that most sports bets are placed on mobile devices rather than in brick-and-mortar sportsbooks.

In addition, with a large number of betting options, soldiers do not have to bet only on the outcome of an event but can make bets “inside” the game. Gamblers can bet on the next home run, the next touchdown, the next goal, or the next out. These possibilities and the speed and frequency with which they occur can compound the threat of gambling and the possibility that it becomes an addiction. Moreover, the high payoff odds on multi-leg parlays can attract the losing gambler who makes a last desperate bet to “get back to even.” Not surprisingly, individuals in high-stress environments may be more susceptible to making rash financial choices that jeopardize their financial stability (Wright Reference Wright2024).

Costs of unchecked behavior

Recent work finds that the increase in sports betting does not displace other gambling activity or entertainment-related consumption, but it does significantly reduce households’ savings allocations (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Balthrop, Johnson, Kotter and Pisciotta2024). Thus, not only are soldiers already at inherent risk of not saving and establishing personal economic security, but mobile sports betting may represent a looming threat to their financial well-being.

Findings suggest that for every dollar spent on sports betting, there is a reduction of two dollars in “investment behavior” (Finance and Herron Reference Finance and Herron2024). These additional dollars are routinely spent on supportive expenses, like purchasing streaming services and/or a night out at bars. The cumulative effect of sport betting can be devastating to a soldier’s financial health, leading, for example, to reducing contributions to the individual thrift savings plans (TSP).

The reason for such negative effects is that the TSP provides an employer match, which is a significant benefit to a soldier’s retirement plan. It is also the strategy the Army has advocated for soldiers, who also receive mandatory financial education about their pension. However, as Baker et al. note (2024), the endorphin rush from mobile sports betting in the short term could outweigh the benefits from the match or growth of personal TSP contributions, which will be experienced in the future.

One additional reason to be concerned about sports betting is the intersection of gambling addiction and mental health issues. Soldiers experiencing PTSD, anxiety, or depression may turn to mobile sports betting as a coping mechanism (Etuk et al. Reference Etuk, Shirk, Grubbs and Kraus2020). This can create a vicious cycle where financial troubles further exacerbate mental health issues, leading to a decline in overall well-being. Research has shown that many comorbidities are associated with gambling disorders among veterans, such as substance, alcohol, and nicotine use (abuse) (Etuk, 2020). In addition, military personnel have shown higher rates of gambling disorders due to factors such as being young, male, prone to risk taking, suffering from depression and PTSD, and experiencing deployment stress (Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Whitty and Leslie2021).

The structure of mobile sports betting can foster addictive behaviors, especially among vulnerable populations. The instant gratification of winning and the thrill of betting can lead to a cycle of chasing losses, ultimately resulting in significant financial losses. Since military members and veterans have an elevated risk of gambling disorder (Van Der Maas, 2020), mobile sports betting can be even a greater threat since it can be accessed by soldiers any time of the day, anywhere they are.

For years, the Army has implemented numerous screening mechanisms and education programs to care for soldiers and family members afflicted by PTSD, substance abuse, addiction, and depression. However, only recently, through the National Defense Authorization Act of 2019 (NDAA) have provisions been required to screen for gambling addiction (NDAA 2019). It is unclear the degree to which programs have been implemented to detect gambling among soldiers. The intent of screening is to mitigate the detriments to readiness that behavioral issues pose, like problem gambling. There is no question that problem gambling can also affect readiness, and therefore efforts should be made to prevent, detect, and or mitigate. Fortunately, there are screening tools in the civilian sector that the Army could adopt, to include: The Gambling Disorder Identification Test, the Lie-Bet Tool, the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen, and the Problem Gambling Severity Index (The Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling, n.d.). In addition, prevention and mitigation can be important, and we turn, next, to these important topics.

Mitigation and prevention

What can the Army do to mitigate this threat? When faced with undesirable outcomes from an off-post location (a casino, for example), a commander could simply restrict those locations by making them off-limits. However, as mentioned earlier, online and mobile sports betting can occur whenever and wherever a soldier is located; all that is needed is a smartphone. This presents the commander with unique challenges. It is hard, if not impossible to outlaw a mobile device. The smartphone has become a wallet, an ID, and a password vault. In many developing countries, phones are considered the fifth necessity, in addition to food, clothes, shelter, and education (Gupta Reference Gupta2011). In the absence of control, education becomes critically important.

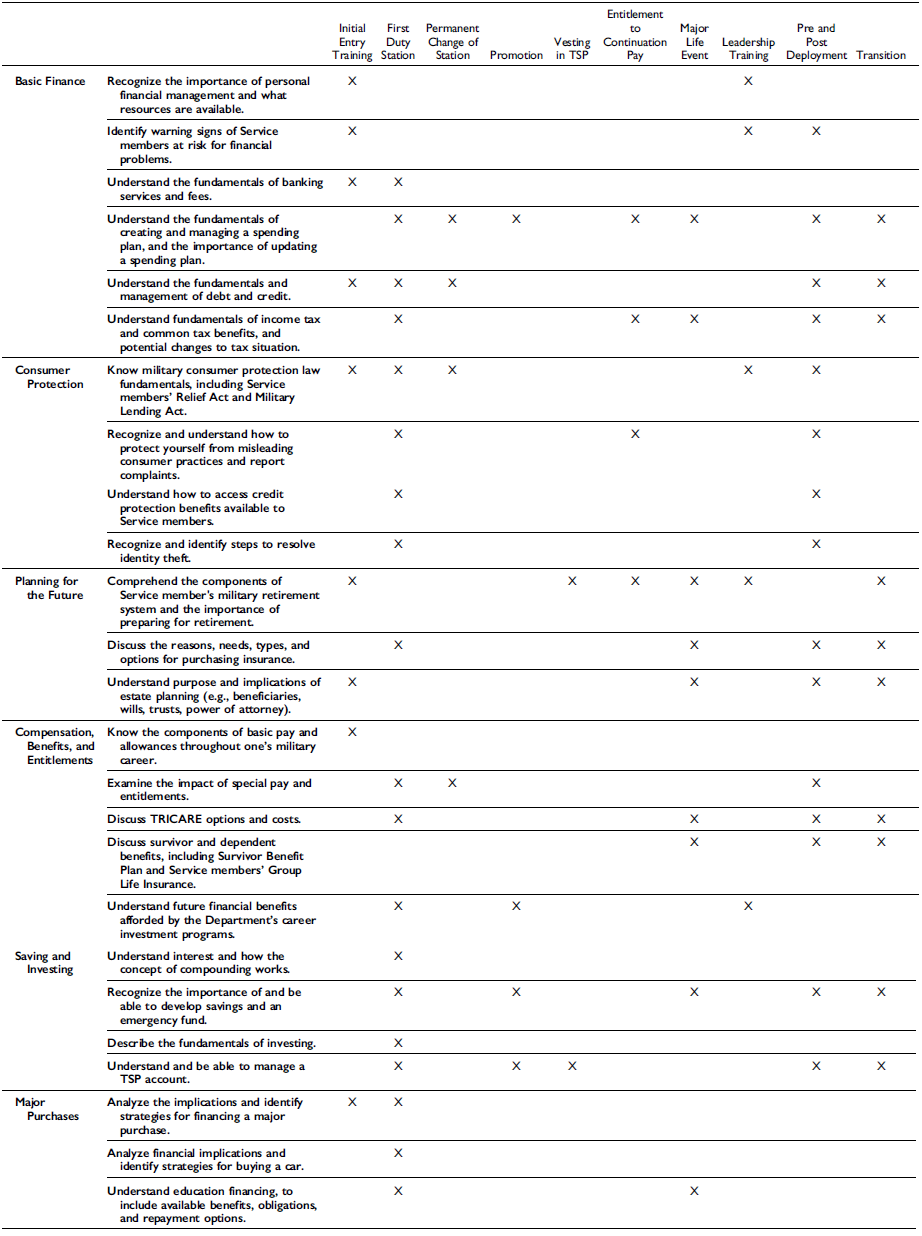

Education is essential to aid and protect soldiers. Military programs can prioritize education about the risks associated with mobile sports betting, while workshops and resources can help soldiers understand the potential for addiction and the importance of responsible gambling. Currently, financial readiness education mandated in the Army does not directly address gambling, let alone mobile sports betting, despite its considerable threat (see Table 1 at the end of the paper).

Figure 1. Figure from www.vegasinsider.com. Army installations with large soldier populations added by authors.

Table 1. Financial readiness CMT TLOs

Engaging existing mental and behavioral health providers can be key. Developing robust support systems, including access to counseling and financial advice, can help soldiers manage their gambling behaviors. Confidential helplines and peer support groups can provide essential resources for those struggling with gambling issues. Many models can be found in the civilian sector.

In addition, the Army can consider policies that restrict access to mobile betting apps during deployments or in high-stress environments, where soldiers can become even more vulnerable. Collaborating with gambling companies to promote responsible gambling features within apps may also be a good intervention. Sports betting companies have the data that can assist in this effort, but they may not view this intervention as in their best interest. However, it may be better to prevent problems than facing future legislation or regulation that places limitations on activities.

Finally, in-depth and targeted research on the mobile sports betting effects on soldiers is a key to understanding and addressing the problem. Carter and Skimmyhorn (Reference Carter and Skimmyhorn2017), for instance, report on this type of investigation, but in the context of state regulations on payday lending. In future work, we hope to conduct research into the prevalence and impacts of mobile sport betting on soldiers, their families, and Army units, recognizing the leisure value that sports betting has and the effects of a restrictive ban. Through our personal economic security lens, we will also aim to identify potential solutions for safeguarding the mental health, financial stability, and overall well-being of soldiers and family members, while also ensuring the readiness and effectiveness of the military force.

Conclusion

Soldiers love sports. From playing to watching, and with greater ease now, gambling on it. Although mobile sports betting has entertainment value, it can also pose a significant threat to the financial well-being of soldiers when it turns into impulsive gambling behaviors and addiction. Early research suggests that it is important to safeguard the financial well-being of our soldiers and overall Army readiness with proactive measures – including education and support systems. Addressing this issue early on can help ensure that soldiers are equipped to manage the challenges posed by a rapidly evolving gambling landscape. In today’s mobile, always-on world, it is essential that personal economic security training is not ignored. Further attention and research must be undertaken to measure the impact on Army readiness and soldier well-being. And while it may be easier to identify a problem drinker than a problem gambler, the threat is real and cannot be ignored. We must start the dialog now.

Funding statement

This research was also made possible by the USAA Education Foundation.