Introduction

Paediatric heart transplant has steadily increased in frequency, peaking above 500 paediatric heart transplants in 2023. Reference MacDonald, Norris and Alton1 With increasing incidence, patient and graft survival have also improved, with an overall median patient survival of 22 years in 2019. Reference Williams, Borges and Banh2 However, as patient complexity has also increased, certain common morbidities have been identified. Acute kidney injury in the peritransplant period is common, described in up to 76% of paediatric heart transplant patients. Reference MacDonald, Norris and Alton1–Reference Patel, Heipertz and Joyce3 Longer-term outcomes of acute kidney injury in paediatric heart transplant, especially when severe, are less described. Adult heart transplant patients requiring perioperative renal replacement therapy occur in 10–15% of patients and have poor outcomes, with up to 40% mortality. Reference Cantarovich, Hirsh and Alam4–Reference Odim, Wheat and Laks6 An earlier era review of the united network for organ sharing database (1993–2008) demonstrated increased mortality at 30 days, 1 year, and 10 years (95%, 89%, and 75% for no perioperative renal replacement therapy versus 72%, 45%, and 40% for perioperative renal replacement therapy) in paediatric patients Reference Tang, Du and L’Ecuyer5 . More recent studies have been limited to single-centre data or specific populations like patients with Fontan circulatory failure and have also shown increased mortality with renal replacement therapy, often around 40%. Reference Lipman, Lytrivi and Fernandez7–Reference Ahmed, Dykes and Friedland-Little9

In order to better evaluate the effect of RRT during the transplant hospitalisation, we assessed the Pediatric Health Information System database to describe those who required renal replacement therapy during the heart transplant hospitalisation. The primary aim of this study was to quantify the number of paediatric heart transplant admissions during which renal replacement therapy is utilised in the modern era. Secondary aims included identifying patient characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes associated with renal replacement therapy.

Methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective study utilising de-identified data from the Pediatric Health Information System database, which is an administrative and billing database. Although data are publicly available and deidentified, institutional review board approval was received for this at Texas Children’s Hospital, as this was the institution where the data were retrieved.

Pediatric Health Information System database

Data for this study were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System database. This is an administrative and billing database that contains inpatient, emergency department, ambulatory surgery, and observation data from not-for-profit, tertiary care paediatric hospitals in the United States. Data for this study were available from 46 hospitals that contribute data to Pediatric Health Information System and are affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, KS), a business alliance of children’s hospitals. Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort between Children’s Hospital Association and participating hospitals. For the purposes of external benchmarking, participating hospitals provide discharge/encounter data, including demographics, diagnoses, procedures, and charges. Data are deidentified at the time of data submission, and data are subjected to reliability and validity checks before inclusion in the database.

Data selection and extraction

Data from the Pediatric Health Information System database from 2018 to 2021 were utilised, including these years. This represents the most recent data that are available that utilise international classification of disease (ICD)-10 codes. ICU admissions were identified utilising the ICU flag. CHD was identified utilising ICD-10 codes for various congenital malformations of the heart. Inclusion criteria for admissions utilised in the final analyses were: (1) paediatric admissions under 18 years of age; (2) admission to an ICU; (3) admission with heart transplant; and (4) admission started with the heart transplant, thus the pre-operative length of stay was zero.

The occurrence of heart transplant was determined by querying the data for the following ICD-10 code- 0ZYA0Z0. Specific congenital malformations of the heart were identified using ICD-10 codes. The presence of specific comorbidities, including but not limited to acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, acute hepatic insufficiency, and stroke, was similarly identified. Some comorbidities had a secondary effect of serving as severity of illness measures, such as individual organ dysfunction, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygen, and cardiac arrest. Heart failure was a composite variable consisting of systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction of the left and/or right ventricle. Genetic anomaly was a composite variable consisting of any identified syndrome or genetic aberration that was coded. The timing of when specific morbidities occurred in the admission relative to one another was not available.

Statistical analyses

The admissions found to meet inclusion criteria were divided into two groups: those with and without renal replacement therapy. For these analyses, renal replacement therapy was limited to continuous renal replacement therapy. It is important to note that these admissions could have had heart transplant at any point at the beginning or during the admission; Pediatric Health Information System data do not allow for discrimination of pre- or post-transplant dialysis in most cases. Univariable comparisons were conducted with Mann-Whitney-U tests to compare continuous variables between groups and Fisher’s exact tests to compare descriptive variables between groups. Next, a backward likelihood ratio logistic regression was conducted to model renal replacement therapy. Renal replacement therapy was the dependent variable, while all the variables listed in Table 1, except for mortality, billed charges, and length of stay, were included as independent variables. A renal replacement therapy probably score was then created using the independent variables with significant association using the beta-coefficients from the regression analysis. A receiver operator curve analysis was then conducted to determine the utility of this score in identifying admissions with renal replacement therapy. Finally, a backward likelihood ratio logistic regression was conducted to model mortality in these admissions. Mortality was the dependent variable, while the variables listed in Table 1, except for billed charges and length of stay, were included as independent variables.

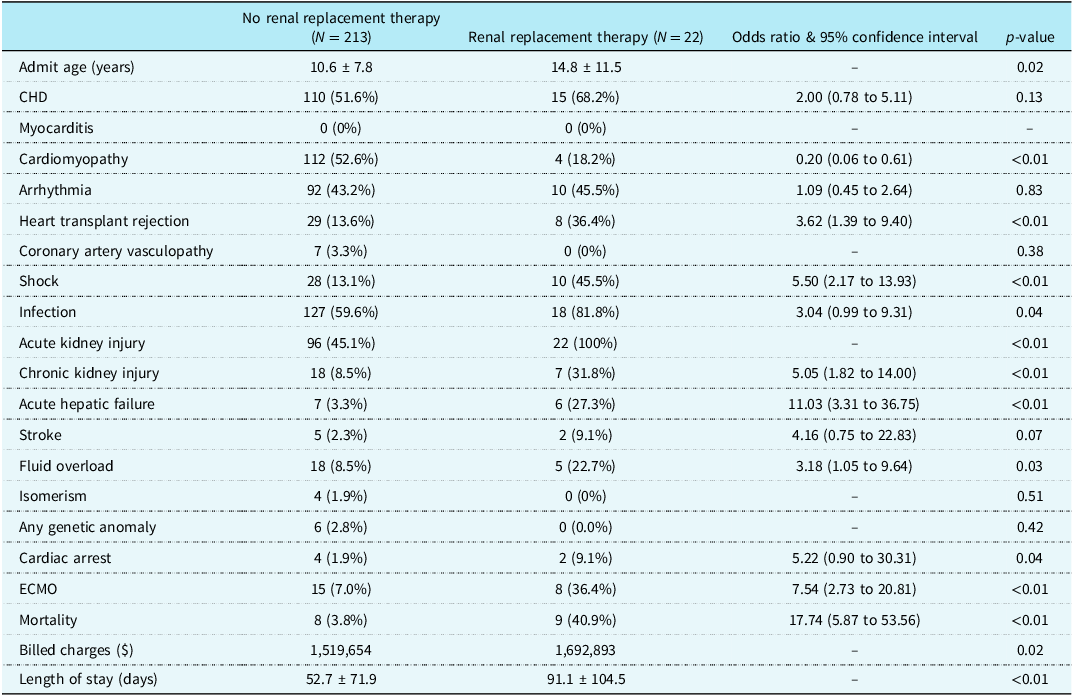

Table 1. Characteristics of those who did and did not receive dialysis during heart transplant admission. This includes only those who had an admission beginning with transplant such that all ICU events occurred after transplant

The above analyses were then repeated but with a subset of admissions in which the pre-heart-transplant length of stay was 0. Phrased differently, these were admissions in which the patient was awaiting transplant outpatient, and the admission of interest began with the transplant. These admissions were identified as then it was certain that renal replacement therapy was utilised after transplant. In the previous group, it could have been utilised before, after, or both in relation to transplant.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 30.0. User-defined syntax was utilised for analyses. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Any use of the word “significant,” “significantly,” or “significance” refers to statistical significance unless explicitly specified otherwise.

Results

Cohort characteristics, all heart transplant admissions

A total of 426,029 paediatric ICU admissions were analysed. Of these total admissions, 1427 were admissions during which there was a heart transplant. Of the 1427 heart transplant admissions, 235 started with transplant. These 235 admissions were ultimately included in the final analyses, as it could be ascertained with certainty that renal replacement therapy occurred after the transplant and not prior to it.

Cohort characteristics

A total of 235 admissions were identified. Of these 235 admissions, 22 (9.3%) had renal replacement therapy utilised. In these admissions, renal replacement therapy was deployed after heart transplant (Table 1). Figure 1 demonstrates the incidence of renal replacement therapy by age in those who underwent a heart transplant.

Figure 1. Bar graph demonstrating the percentage of children in various age groups that required renal replacement therapy after heart transplant.

Admissions during which renal replacement therapy was utilised tended to be older (14.8 years versus 10.6 years, p = 0.02), were less likely to have cardiomyopathy (18.2% versus 52.6%, p < 0.01), more likely to have heart transplant rejection (36.4% versus 13.6%, p < 0.01), more likely to have shock (45.5% versus 13.1%, p < 0.01, more likely to have an infection (81.8% versus 59.6%, p = 0.04), more likely to have acute kidney injury (100% versus 45.1%, p < 0.01), more likely to have chronic kidney injury (31.8% versus 8.5%, p < 0.01), more likely to have acute hepatic failure (27.3% versus 3.3%, p < 0.01), and more likely to have fluid overload (22.7% versus 8.5%, p = 0.03). Admissions during which renal replacement was utilised were more likely to have had extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (36.4% versus 7.0% p < 0.01), were more likely to experience mortality (40.9% versus 2.8%, p < 0.02), had higher billed charges ($1,692,893 versus $1,519,654, p = 0.02), and greater total length of stay (91.1 days versus 52.7 days). Mortality in admissions without renal replacement therapy was 3.8%, and mortality in admissions with renal replacement therapy was 40.9% (Table 1).

Regression to model dialysis

The regression to model renal replacement therapy demonstrated that admissions with renal replacement therapy were more likely to have acute kidney injury, more likely to have acute hepatic failure, and more likely to have shock.

When data from the regression were used to create a renal replacement therapy probability score, the following equation was the result: (acute kidney injury × 31.19) + (acute hepatic failure) + (shock × 1.67). A receiver operator curve analysis of the score had an area under the curve of 0.857 with model quality of 0.79 (good quality). Optimal cutoff for the score was found to be 16.43 (100% sensitivity, 55% specificity).

Regression to model mortality

The regression to model mortality demonstrated that admissions with mortality were more likely to have a genetic anomaly, more likely to have shock, more likely to have heart failure, more likely to utilise extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and more likely to utilise renal replacement therapy.

Discussion

These analyses highlight some important findings regarding renal replacement therapy during paediatric heart transplant admissions. First, up to 9.3% of patients may require renal replacement therapy after a heart transplant. Secondly, there are comorbidities such as acute kidney injury and shock that are associated with the utilisation of renal replacement therapy. Third, renal replacement therapy is associated with increased risk of mortality and renal replacement therapy is associated with greater mortality in heart transplant admissions compared to other paediatric intensive care admissions.

In the current study, 50.2% of paediatric heart transplant admissions had acute kidney injury, while 9.7% were documented to have fluid overload. As prior literature has generally described a higher incidence of acute kidney injury, these are likely underestimates due to under-coding. Reference MacDonald, Norris and Alton1–Reference Patel, Heipertz and Joyce3 Nonetheless, this highlights the high burden of acute kidney injury and fluid overload in the paediatric heart transplant population. Acute kidney injury and the associated impairment in renal clearance as well as fluid overload may both lean to a decision to utilise renal replacement therapy. In the current study, 9.3% of paediatric heart transplant admissions utilised renal replacement therapy, which is similar to previous studies reporting 5–11% incidence.

When to initiate renal replacement therapy still remains unclear and is provider- and institution-dependent. The current study identified comorbidities associated with the utilisation of renal replacement therapy, but it is important to acknowledge that the decision to utilise renal replacement therapy and when to initiate it are user-defined, and these associations do not reflect strict physiologic associations. Once initiated, renal replacement therapy is associated with increased total length of hospitalisation, increased billed charges, and increased mortality. The increased cost is not surprising, as there is an expense for the personnel and equipment required for renal replacement therapy, as well as an expense for associated laboratory monitoring while renal replacement therapy is deployed. The additional length of stay is also not surprising, as children will not be sent home until improvement in the acute kidney injury or fluid overload that initially led to use of renal replacement therapy occurs. The mortality, while not surprising, requires more nuanced interpretation.

There are limited data regarding renal replacement therapy during paediatric heart transplant admissions. These data from the current study along with the other published data can help lend insight into clinical decision-making and future study design. While the data are insightful, they are not without limitations. The data are sourced from an administrative database, which means that it is based on coding. Certain comorbidities may not be coded as stringently as others. For instance, it seems likely that fluid overload is not well documented. Some comorbidities of interest, such as primary graft dysfunction, also do not have a singular, discrete code and may therefore have been under-identified. There is not likely an actual increased risk for renal replacement therapy need for tricuspid atresia or double outlet right ventricle lesions. Rather, when these particular lesions lead to single-ventricle palliation failure, they are often associated with complex anatomy that might contribute to longer or more difficult heart transplants. This might be the actual underlying mechanism for their significance, rather than hypoplastic left heart syndrome or all single-ventricle heart disease. Additionally, the definitions of acute kidney injury and fluid overload were not uniform across centres and were not defined in the dataset. Similarly, acute kidney injury severity was not available in the database. Nonetheless, the data are informative.

Conclusion

Up to 9% of paediatric heart transplant admissions utilise renal replacement therapy. A variety of clinical conditions are associated with increased probability of renal replacement therapy use. Predictive models described demonstrate high sensitivity for the need for renal replacement therapy during heart transplant hospitalisation. There is a high burden of mortality in heart transplant admissions utilising renal replacement therapy, especially with post-transplant dialysis. This is higher than non-transplant paediatric ICU admissions utilising renal replacement therapy. This is an association and not causation. These data can help inform clinical guidance and future clinical studies.