1.1 Graphene Band Structure

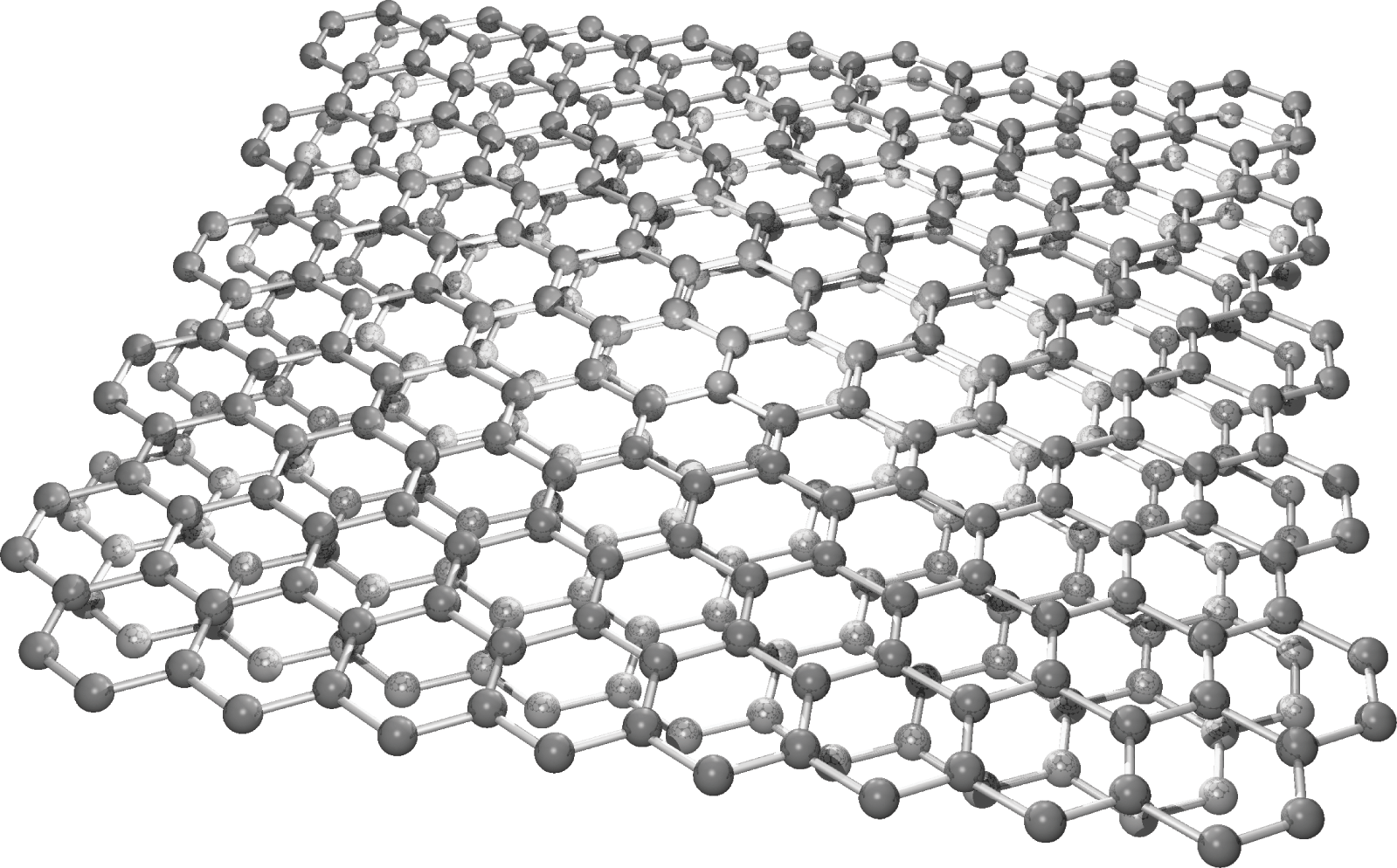

Graphene is a two-dimensional structure of carbon atoms. Single-layer graphene consists of only one layer of carbon atoms. A carbon atom has six electrons occupying the 1s2, 2s2, 2px, and 2py atomic orbitals. When carbon atoms are brought together, one electron from the 2s orbital is promoted to the 2pz orbital for the formation of hybrid orbitals. In diamonds, the 2s, 2px, 2py, and 2pz orbitals are mixed to form four sp3 hybrid orbitals for each carbon atom; therefore, each carbon atom is joined with four neighbors by overlapping their sp3 hybrid orbitals. In graphite, instead of four sp3 hybrid orbitals, three sp2 hybrid orbitals are formed through mixing of the 2s, 2px, and 2py orbitals, while the fourth orbital remains as 2pz. Overlapping sp2 hybrid orbitals from two adjacent atoms creates a strong σ covalent bond (C‒C bond); these in-plane σ bonds connect each carbon atom to three neighbors. The remaining 2pz orbitals of these carbon atoms form π bonds, which are responsible for binding carbon layers together in graphite. Because π bonds are much weaker than σ bonds, graphite has a low shear strength so that its carbon layers can be easily detached. For monolayer graphene, these nearly free π electrons are responsible for most of its experimentally observed electronic and optical properties. Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that π electrons from different carbon atoms do not occupy the same state, the large number of closely packed carbon atoms in graphene causes degenerate energy levels to split into continuously distributed nondegenerate levels of allowed energy states, forming energy bands.

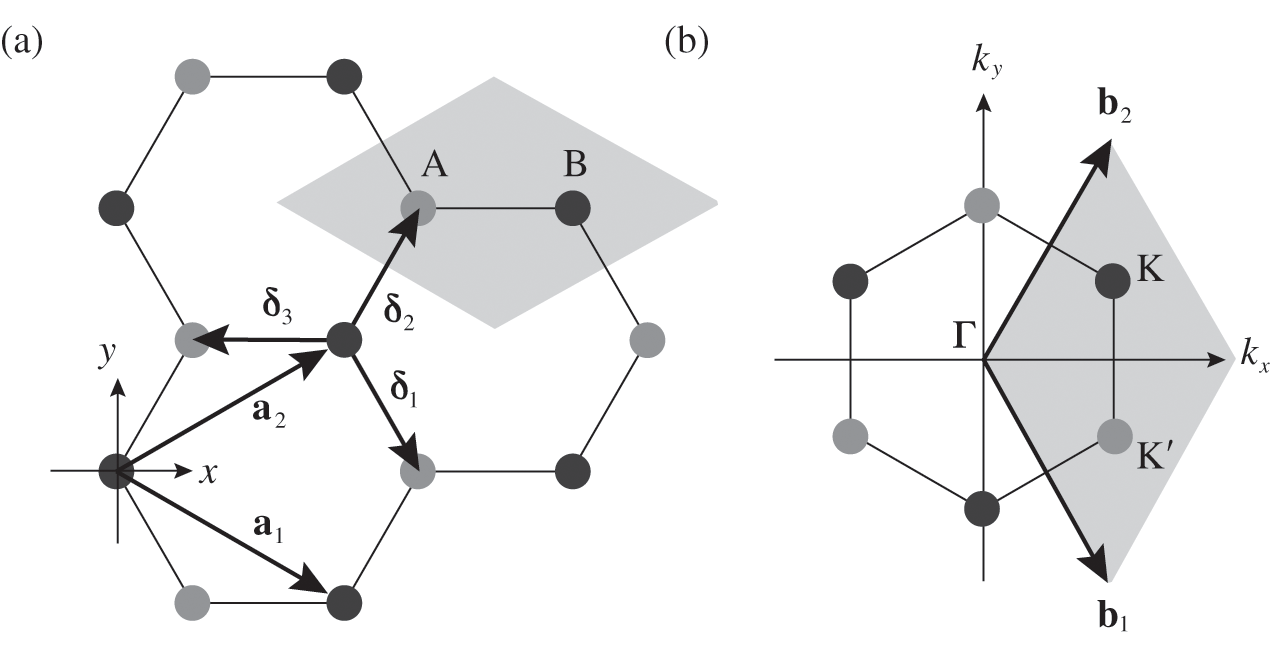

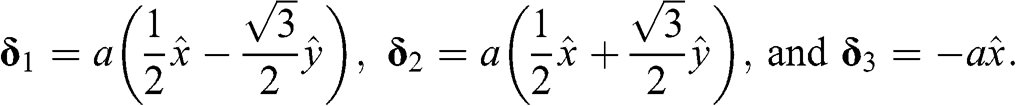

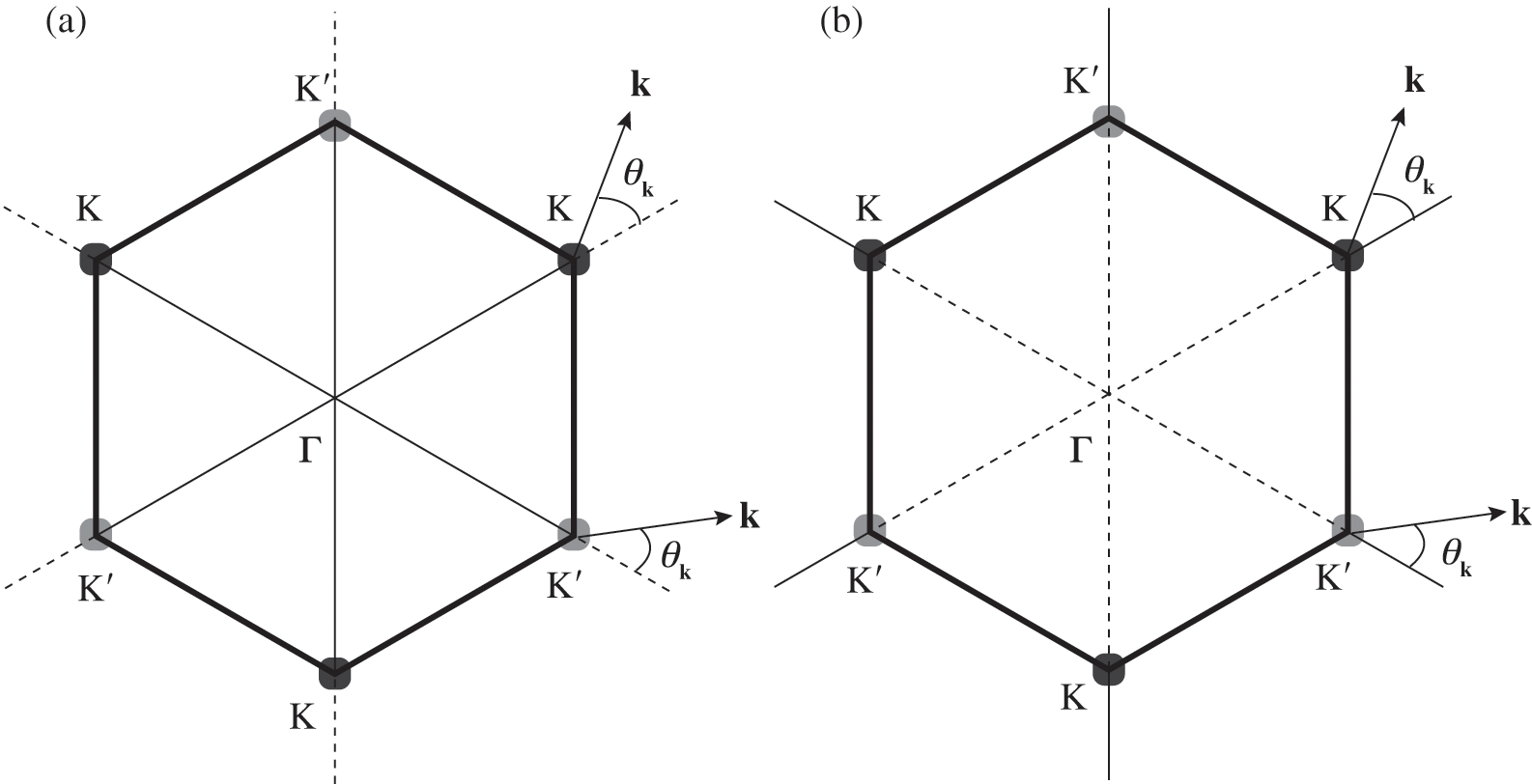

The real-space two-dimensional honeycomb lattice of graphene is shown in Figure 1.1(a). The distance between two neighboring carbon atoms in graphene is

The primitive lattice vectors are

(1.2)

(1.2)

Therefore, the lattice constant is

(1.3)

(1.3)

The area Ap of a primitive unit cell can be obtained as

(1.4)

(1.4)

where ![]() is the unit vector that points in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the two-dimensional graphene lattice. We also find that the vectors connecting adjacent carbon atoms are

is the unit vector that points in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the two-dimensional graphene lattice. We also find that the vectors connecting adjacent carbon atoms are

(1.5)

(1.5)

as shown in Figure 1.1(a).

Figure 1.1 (a) Real-space honeycomb graphene lattice. The lattice consists of two overlapping Bravais sublattices, A (gray dots) and B (black dots). The primitive unit cell is drawn as a shaded area. ![]() and

and ![]() are the primitive lattice vectors.

are the primitive lattice vectors. ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are vectors pointing from a B atom to its nearest A atoms. (b) Brillouin zone of graphene drawn as a shaded area.

are vectors pointing from a B atom to its nearest A atoms. (b) Brillouin zone of graphene drawn as a shaded area. ![]() and

and ![]() are the primitive vectors of the reciprocal lattice. Dirac points

are the primitive vectors of the reciprocal lattice. Dirac points ![]() (black dots) and

(black dots) and ![]() (gray dots) are marked.

(gray dots) are marked.

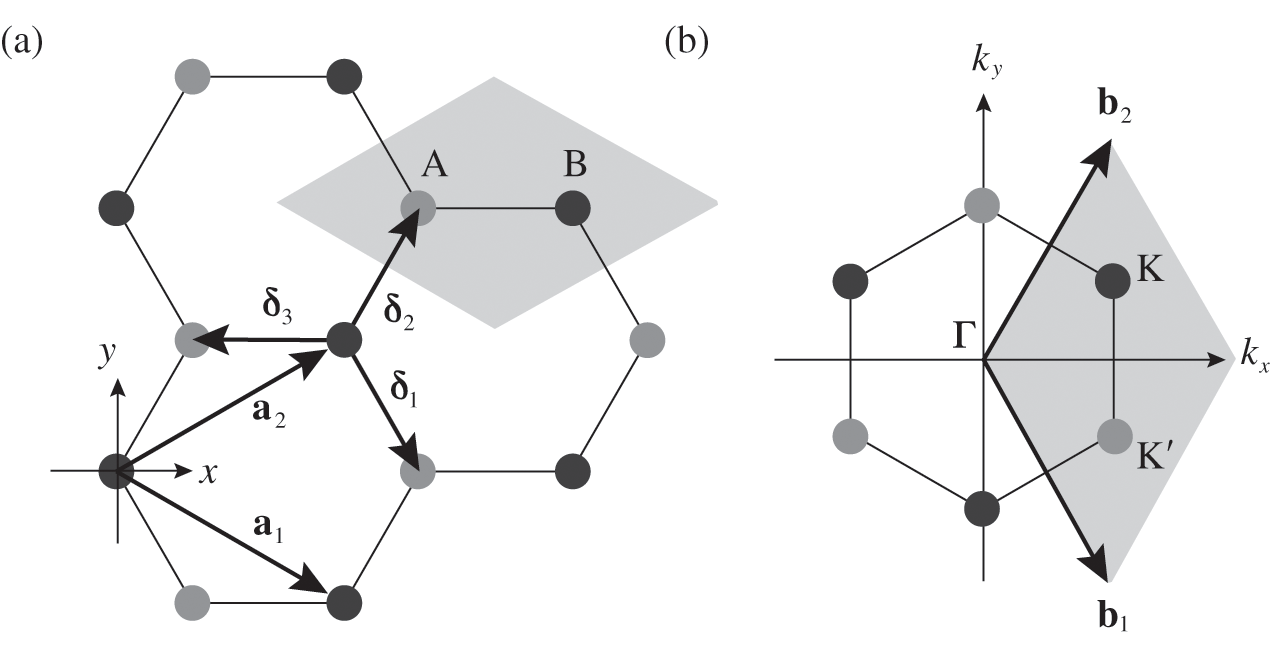

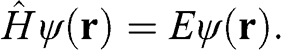

The corresponding Brillouin zone of the lattice in Figure 1.1(a) is shown in Figure 1.1(b). The primitive vectors of the reciprocal lattice are

(1.6)

(1.6)

We can also find the vector ![]() that is perpendicular to the plane of the two-dimensional reciprocal lattice. Therefore,

that is perpendicular to the plane of the two-dimensional reciprocal lattice. Therefore,

where ![]() is the Kronecker delta function:

is the Kronecker delta function: ![]() if

if ![]() , and

, and ![]() if

if ![]() .

.

The honeycomb lattice of graphene is not a Bravais lattice because the locations of all carbon atoms cannot be generated by the translation

where m and n are integers. The lattice structure of graphene consists of two overlapping Bravais sublattices A and B, and thus a primitive unit cell contains two carbon atoms, as shown in Figure 1.1(a). All of the carbon atoms on the same sublattice, but not those on the two different sublattices, are connected by the vector ![]() .

.

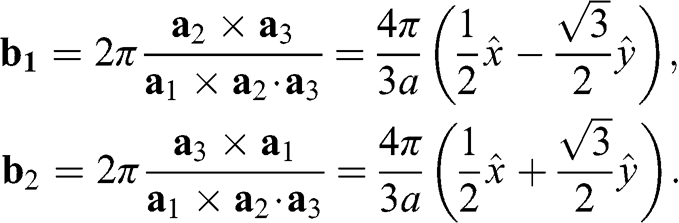

The electronic band structure of graphene can be obtained by using the tight-binding model. We start from a tight-binding Hamiltonian ![]() for the Schrödinger equation:

for the Schrödinger equation:

(1.9)

(1.9)

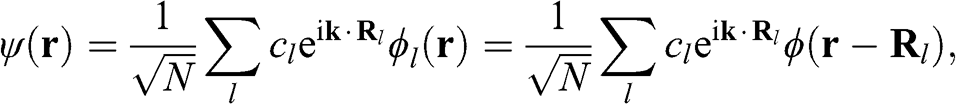

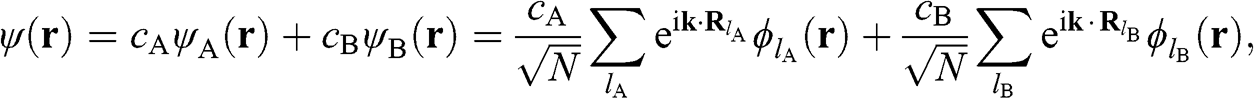

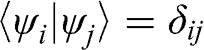

The wave function ![]() is given by the linear superposition of orbital functions

is given by the linear superposition of orbital functions ![]() :

:

(1.10)

(1.10)

where N is the number of unit cells, ![]() is the ground state of the

is the ground state of the ![]() electron of an isolated carbon atom that is located at

electron of an isolated carbon atom that is located at ![]() , and the index l runs over all carbon atom points on the graphene lattice. Equation (1.10) is of the Bloch form because

, and the index l runs over all carbon atom points on the graphene lattice. Equation (1.10) is of the Bloch form because ![]() , where

, where ![]() or 2. From the symmetry point of view, all atoms on sublattice A are geometrically identical; in other words, the surrounding is the same when viewing the graphene lattice from any atom on sublattice A. The same can be said for all atoms on sublattice B. No difference can be seen when viewing the graphene lattice from different atoms on the same sublattice. However, the atoms on sublattice A are not geometrically identical to those on sublattice B. By comparing the scenery in a certain direction, it is possible to tell the difference between viewing the graphene lattice from one atom on sublattice A and viewing it from one on sublattice B. Therefore, the wave function in (1.10) has only two independent coefficients for

or 2. From the symmetry point of view, all atoms on sublattice A are geometrically identical; in other words, the surrounding is the same when viewing the graphene lattice from any atom on sublattice A. The same can be said for all atoms on sublattice B. No difference can be seen when viewing the graphene lattice from different atoms on the same sublattice. However, the atoms on sublattice A are not geometrically identical to those on sublattice B. By comparing the scenery in a certain direction, it is possible to tell the difference between viewing the graphene lattice from one atom on sublattice A and viewing it from one on sublattice B. Therefore, the wave function in (1.10) has only two independent coefficients for ![]() :

: ![]() and

and ![]() , which respectively represent the amplitudes of the wave functions at carbon sites on sublattices A and B. Thus, (1.10) can be rewritten as a linear superposition of two Bloch functions

, which respectively represent the amplitudes of the wave functions at carbon sites on sublattices A and B. Thus, (1.10) can be rewritten as a linear superposition of two Bloch functions ![]() and

and ![]() that are respectively wave functions for sublattices A and B:

that are respectively wave functions for sublattices A and B:

(1.11)

(1.11)

where ![]() and

and ![]() run over all of the carbon atoms on sublattices A and B, respectively. The wave functions

run over all of the carbon atoms on sublattices A and B, respectively. The wave functions ![]() and

and ![]() are normalized, and the overlap of

are normalized, and the overlap of ![]() and

and ![]() is negligible [Reference Reich, Maultzsch, Thomsen and Ordejón1], so that

is negligible [Reference Reich, Maultzsch, Thomsen and Ordejón1], so that  . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() and

and ![]() form the basis for the graphene wave functions.

form the basis for the graphene wave functions.

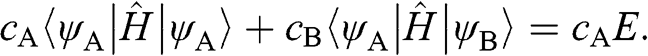

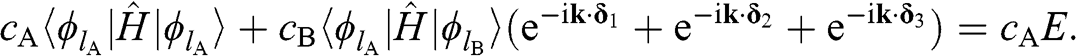

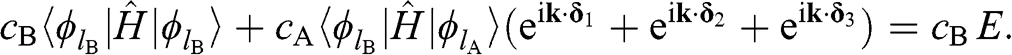

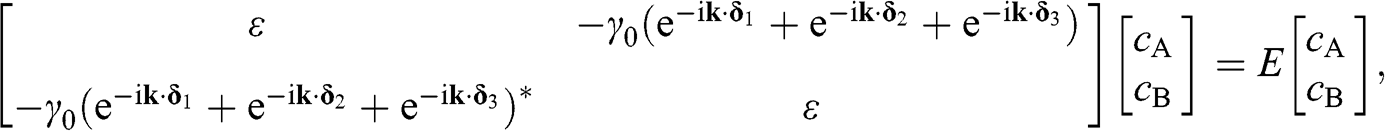

By multiplying both sides of (1.9) by ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

(1.12)

(1.12)

In (1.12), all of the interactions among A atoms and those between A atoms and B atoms are considered. However, it is very difficult to solve for the eigenenergy from (1.12) where all interactions are accounted for. To avoid such difficulty, (1.12) is simplified by taking the approximation of considering only the self-interaction of each carbon atom at a lattice point and the interactions of the atom with its three nearest neighbors; all long-range interactions are assumed to be much weaker than these interactions and are thus ignored. Within this approximation, (1.12) takes the simple form:

(1.13)

(1.13)

By multiplying both sides of (1.11) by ![]() and taking the same approximation, we have

and taking the same approximation, we have

(1.14)

(1.14)

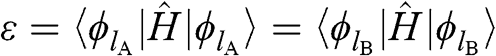

Equations (1.13) and (1.14) can be expressed in a matrix form for the eigenenergy equation of the system:

(1.15)

(1.15)

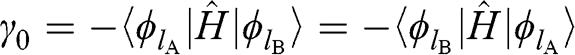

where

(1.16)

(1.16)

is the self-interaction energy, and

(1.17)

(1.17)

is the nearest-neighbor hopping energy in graphene. The nearest-neighbor hopping energy ![]() is experimentally measured to have a value of

is experimentally measured to have a value of ![]() [Reference Peres2–Reference Abergel, Apalkov, Berashevich, Ziegler and Chakraborty4], which is the same as that found for graphite.

[Reference Peres2–Reference Abergel, Apalkov, Berashevich, Ziegler and Chakraborty4], which is the same as that found for graphite.

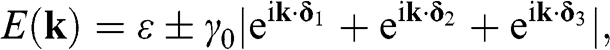

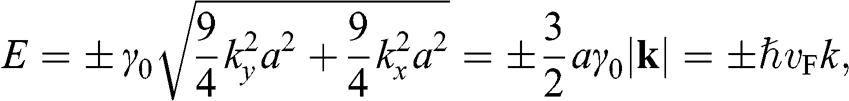

The nontrivial eigenvalues of (1.15) yield two eigenenergies:

(1.18)

(1.18)

where the plus sign is for the conduction band, which has higher energy, and the minus sign is for the valence band, which has lower energy. The conduction band and the valence band described by (1.18) are also called the ![]() band and the

band and the ![]() band, respectively. Equation (1.18) can be written in another form that is frequently seen in the literature [Reference Wallace5,Reference Castro Neto, Guinea, Peres, Novoselov and Geim6]:

band, respectively. Equation (1.18) can be written in another form that is frequently seen in the literature [Reference Wallace5,Reference Castro Neto, Guinea, Peres, Novoselov and Geim6]:

(1.19)

(1.19)

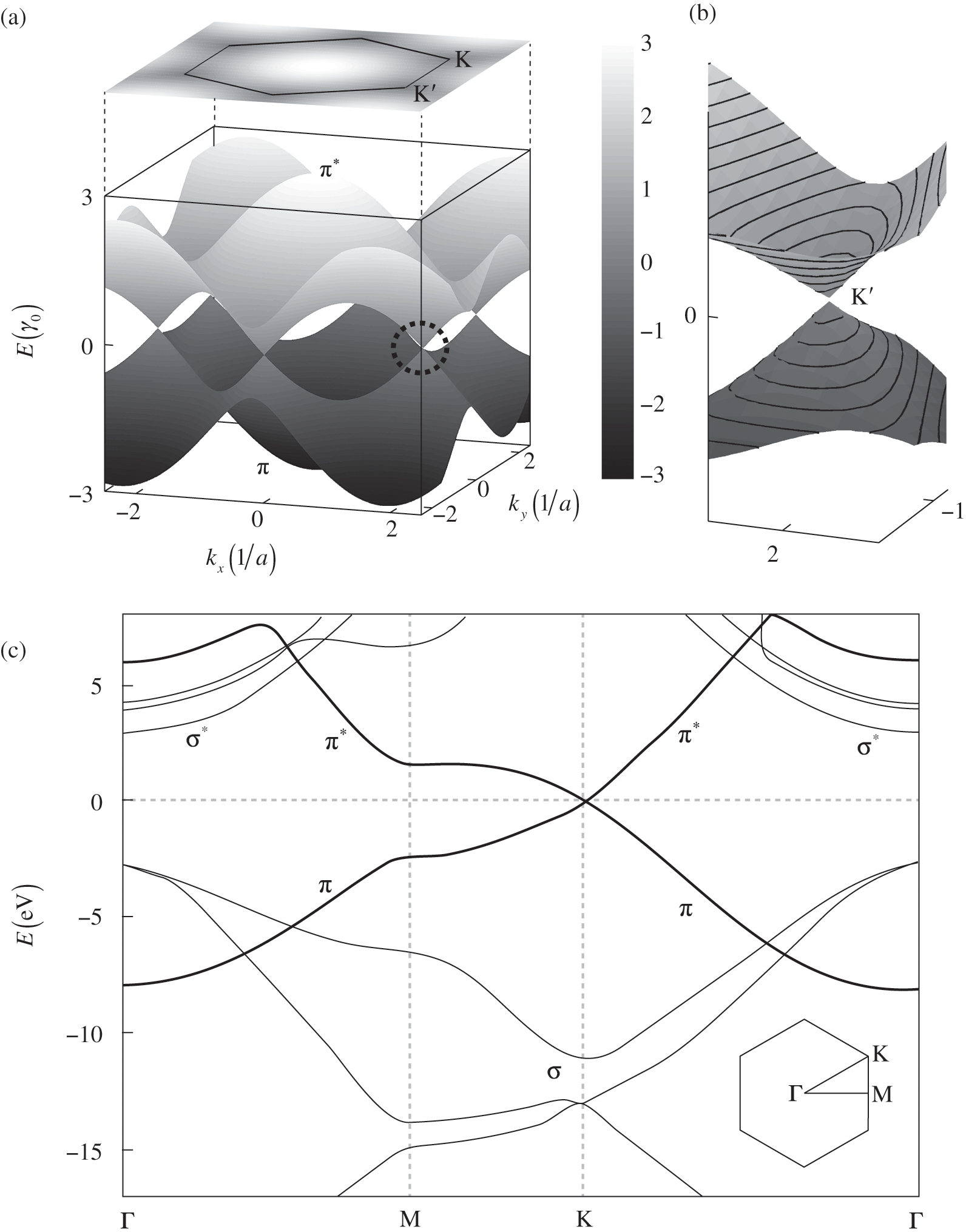

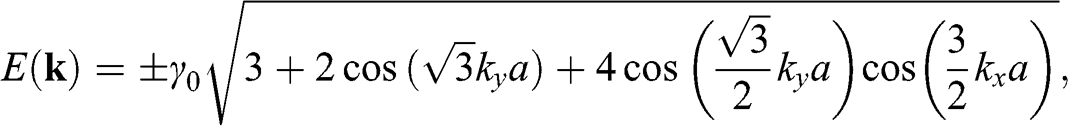

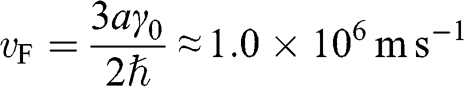

The energy band structure described by (1.19) is plotted in Figure 1.2(a). At the Г point (![]() ), we find the eigenenergies

), we find the eigenenergies ![]() from (1.19), which are associated with the eigenstates

from (1.19), which are associated with the eigenstates  , respectively. The eigenenergy

, respectively. The eigenenergy ![]() for the valence band is associated with symmetric bonding orbitals such that the amplitudes

for the valence band is associated with symmetric bonding orbitals such that the amplitudes ![]() and

and ![]() of the wave functions for sublattices A and B have the same sign. By contrast, the eigenenergy

of the wave functions for sublattices A and B have the same sign. By contrast, the eigenenergy ![]() for the conduction band is associated with antibonding orbitals such that the amplitudes

for the conduction band is associated with antibonding orbitals such that the amplitudes ![]() and

and ![]() of the wave functions for sublattices A and B have opposite signs. An eigenstate of graphene is not necessarily bonding or antibonding, however; most eigenstates are a mixture of both bonding and antibonding orbitals. As we shall see in the following, only along a specific set of directions can the eigenstates be described by purely bonding or antibonding orbitals. The conduction band (

of the wave functions for sublattices A and B have opposite signs. An eigenstate of graphene is not necessarily bonding or antibonding, however; most eigenstates are a mixture of both bonding and antibonding orbitals. As we shall see in the following, only along a specific set of directions can the eigenstates be described by purely bonding or antibonding orbitals. The conduction band (![]() band) and the valence band (

band) and the valence band (![]() band) are symmetric with respect to the

band) are symmetric with respect to the ![]() plane, as shown in Figure 1.2(a). Note that the long-range interactions of carbon atoms beyond the nearest neighbors are ignored in the above analysis. When these long-range interactions are accounted for, we find that the

plane, as shown in Figure 1.2(a). Note that the long-range interactions of carbon atoms beyond the nearest neighbors are ignored in the above analysis. When these long-range interactions are accounted for, we find that the ![]() and

and ![]() bands are actually not symmetric to each other, as seen in Figure 1.2(c), where we also show the

bands are actually not symmetric to each other, as seen in Figure 1.2(c), where we also show the ![]() and

and ![]() bands contributed by the

bands contributed by the ![]() bonds.

bonds.

Figure 1.2 (a) Band structure of graphene plotted using (1.19) while setting the self-interaction energy to be ![]() . The top surface of a higher energy is the conduction band (

. The top surface of a higher energy is the conduction band (![]() band), and the bottom surface of a lower energy is the valence band (

band), and the bottom surface of a lower energy is the valence band (![]() band). The conduction band is projected onto a two-dimensional plane on the top. The circled region near the Dirac point

band). The conduction band is projected onto a two-dimensional plane on the top. The circled region near the Dirac point ![]() is enlarged in (b). (c) Full band structure of graphene. The thick curves are the

is enlarged in (b). (c) Full band structure of graphene. The thick curves are the ![]() and

and ![]() bands, and the thin curves are the

bands, and the thin curves are the ![]() and

and ![]() bands [Reference Sedelnikova, Bulusheva and Okotrub7].

bands [Reference Sedelnikova, Bulusheva and Okotrub7].

As can be seen in Figure 1.2(a), the conduction band touches the valence band at ![]() . The self-interaction energy

. The self-interaction energy ![]() can be taken as the reference level by setting it to be 0 for simplicity so that an electron in a state on the conduction band has a positive energy and that in a state on the valence band has a negative energy. Then, (1.19) can be simplified as

can be taken as the reference level by setting it to be 0 for simplicity so that an electron in a state on the conduction band has a positive energy and that in a state on the valence band has a negative energy. Then, (1.19) can be simplified as

(1.20)

(1.20)

where the plus sign represents the conduction band and the minus sign represents the valence band. The points at ![]() are called the Dirac points; the vicinities of these points are referred to as the valleys, where the graphene band structure can be described by the relativistic Dirac equation, which is further discussed in the following section. Corresponding to the two distinct sublattices A and B in the real space, there are two distinct groups of Dirac points

are called the Dirac points; the vicinities of these points are referred to as the valleys, where the graphene band structure can be described by the relativistic Dirac equation, which is further discussed in the following section. Corresponding to the two distinct sublattices A and B in the real space, there are two distinct groups of Dirac points ![]() and

and ![]() in the k space. Inside the Brillouin zone drawn in Figure 1.1(b), two Dirac points can be found at the k-space locations represented by the reciprocal space vectors:

in the k space. Inside the Brillouin zone drawn in Figure 1.1(b), two Dirac points can be found at the k-space locations represented by the reciprocal space vectors:

(1.21)

(1.21)

Another popular choice of the k-space locations of ![]() and

and ![]() in the literature is to select the

in the literature is to select the ![]() and

and ![]() points on the ky axis so that they are mirror symmetric with respect to the kx axis; the physics and the results obtained in the following are unchanged by this alternative selection. It can be easily shown using (1.20) that

points on the ky axis so that they are mirror symmetric with respect to the kx axis; the physics and the results obtained in the following are unchanged by this alternative selection. It can be easily shown using (1.20) that ![]() at these Dirac points.

at these Dirac points.

For perfectly intrinsic graphene, the chemical potential, i.e., the Fermi level, is located at the energy level of the Dirac points, ![]() , so that the valence band is completely filled and the conduction band is completely empty. As most physics and carrier transitions happen at energy levels around the chemical potential, we shall rewrite (1.20) by shifting the origin of the k space to one of the Dirac points and assume a small k to simplify (1.20). Substituting

, so that the valence band is completely filled and the conduction band is completely empty. As most physics and carrier transitions happen at energy levels around the chemical potential, we shall rewrite (1.20) by shifting the origin of the k space to one of the Dirac points and assume a small k to simplify (1.20). Substituting ![]() in (1.20) with

in (1.20) with ![]() or

or ![]() , we obtain, for

, we obtain, for ![]() in the vicinity of a Dirac point,

in the vicinity of a Dirac point,

(1.22)

(1.22)

where ![]() is the reduced Planck’s constant and

is the reduced Planck’s constant and

(1.23)

(1.23)

is the Fermi velocity in graphene, the physical meaning of which will become clear in Section 1.5. Equation (1.22) indicates that there is a region in the k space around each Dirac point where the carrier energy is linearly proportional to the wave number measured with respect to the given Dirac point. This region is called the Dirac cone, as shown in the insert in Figure 1.2(b). Because (1.22) can also be derived from the massless Dirac equation, electrons on the Dirac cone are also called Dirac electrons.

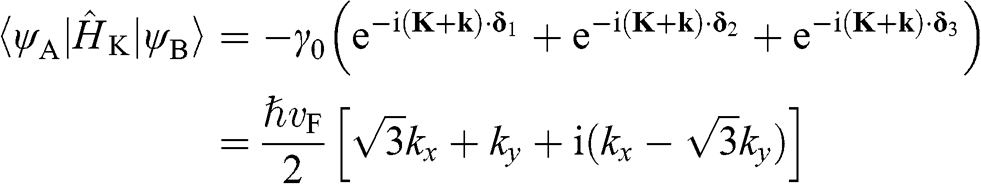

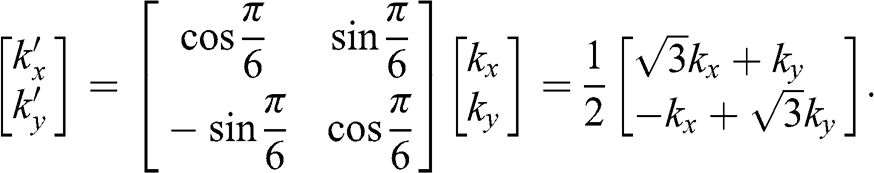

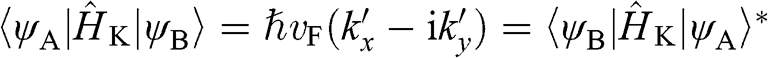

The Hamiltonian around the ![]() point is obtained in the same way as (1.22) is obtained. By substituting

point is obtained in the same way as (1.22) is obtained. By substituting ![]() with

with ![]() in (1.15) to set the origin of the k space at the

in (1.15) to set the origin of the k space at the ![]() point, the off-diagonal matrix elements for

point, the off-diagonal matrix elements for ![]() become

become

(1.24)

(1.24)

and

(1.25)

(1.25)

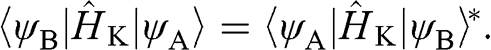

The coefficients of ![]() and

and ![]() can be simplified by rotating both the

can be simplified by rotating both the ![]() and

and ![]() coordinate axes counterclockwise by 30 degrees through the unitary transformation

coordinate axes counterclockwise by 30 degrees through the unitary transformation

(1.26)

(1.26)

Using (1.26), we obtain the relation  from (1.24) and (1.25). By dropping the prime symbols,

from (1.24) and (1.25). By dropping the prime symbols, ![]() and

and  , to simplify the notation, the Hamiltonian near the

, to simplify the notation, the Hamiltonian near the ![]() point for

point for ![]() can be expressed as

can be expressed as

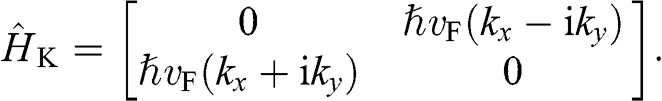

(1.27)

(1.27)

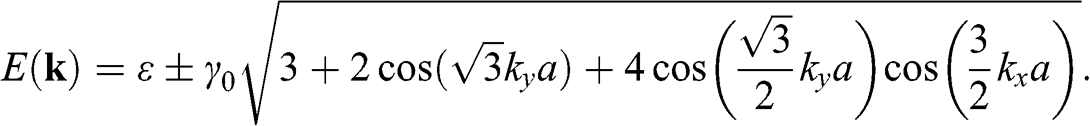

The corresponding eigenfunctions are

(1.28)

(1.28)

where the ![]() signs correspond to the signs of the eigenenergies given in (1.22), and

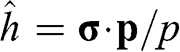

signs correspond to the signs of the eigenenergies given in (1.22), and ![]() is the polar angle measured between

is the polar angle measured between ![]() and the rotated

and the rotated ![]() axis as shown in Figure 1.3(a) for the

axis as shown in Figure 1.3(a) for the ![]() point.

point.

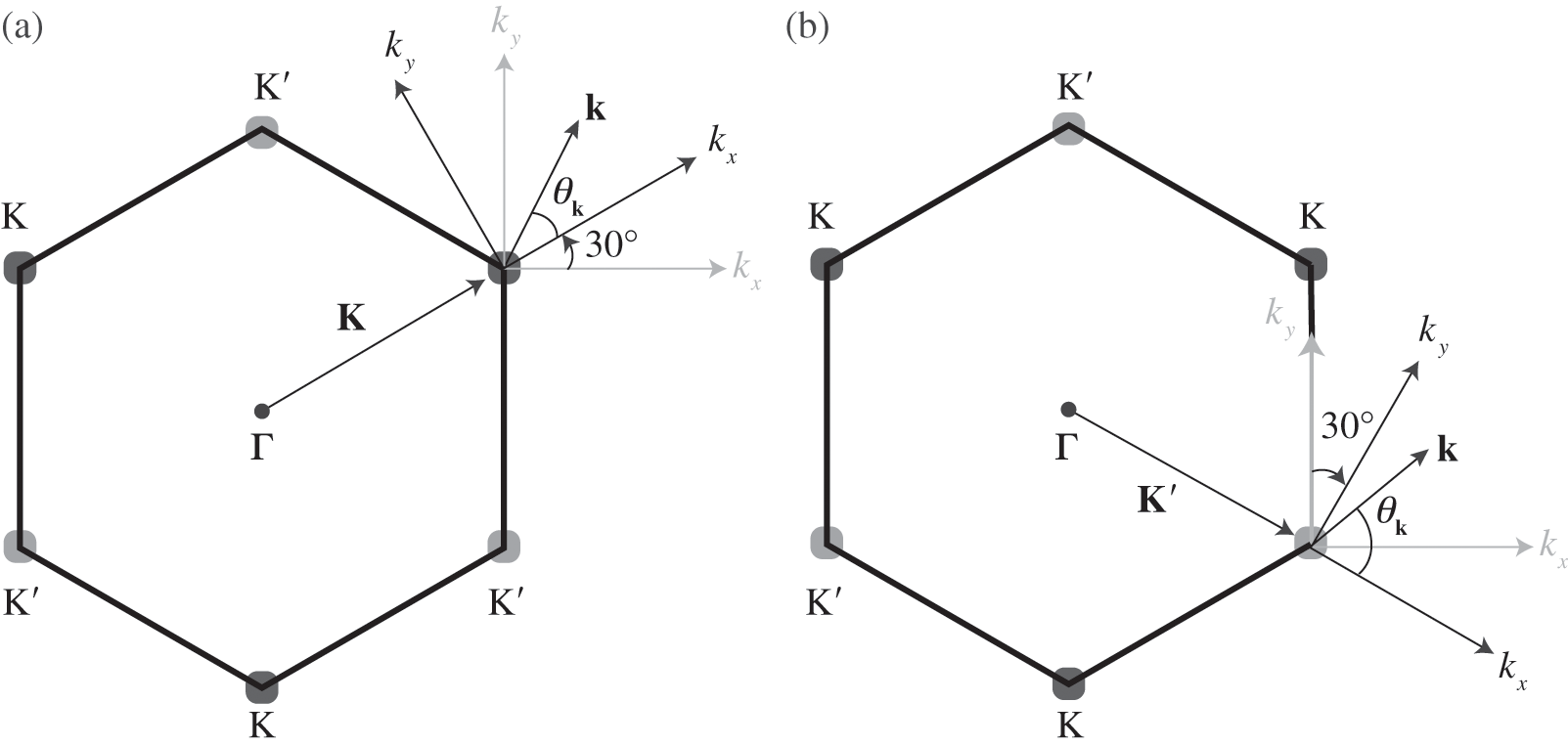

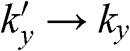

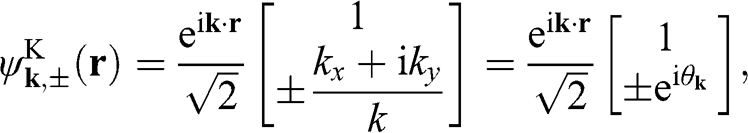

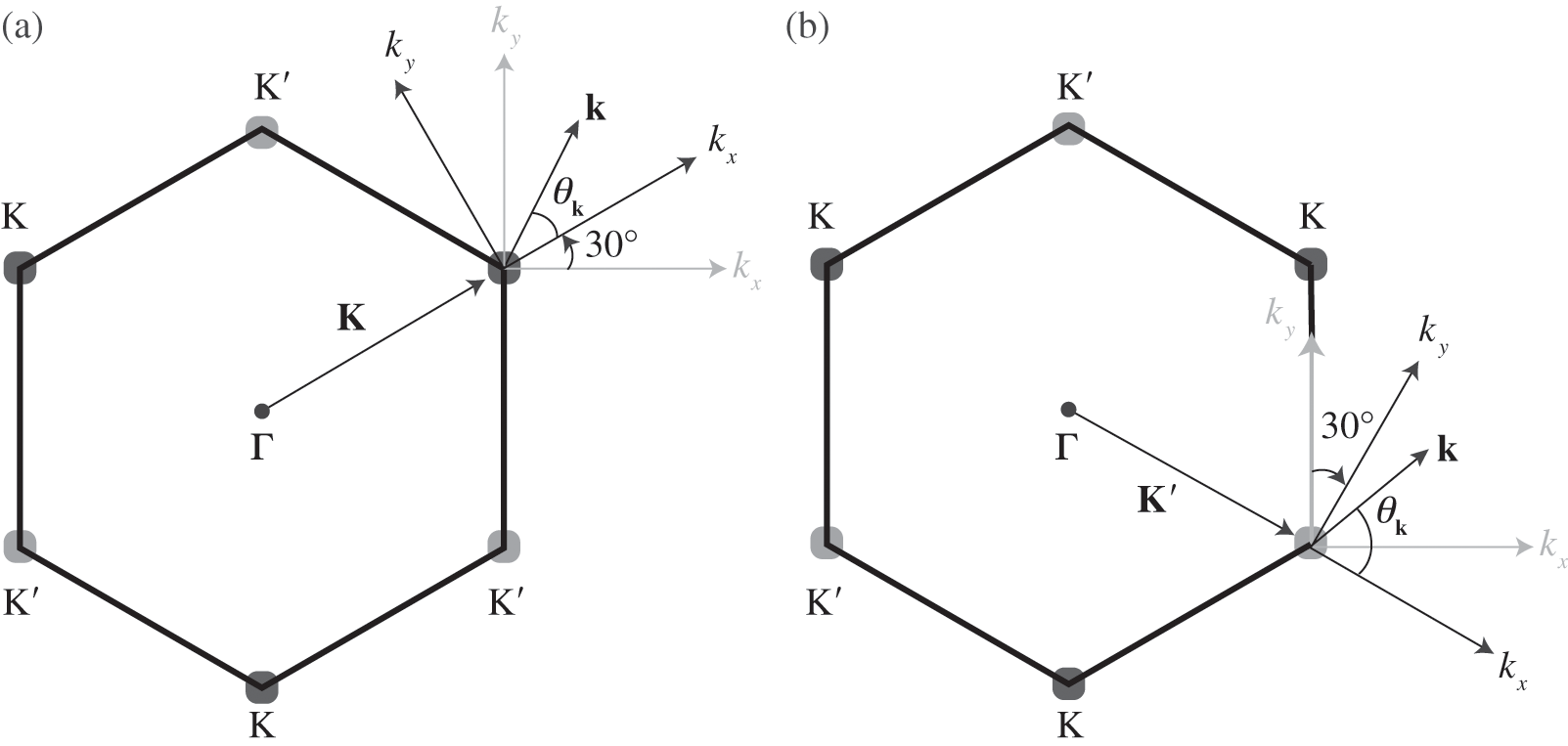

Figure 1.3 Wave vector ![]() near (a) the

near (a) the ![]() point, and (b) the

point, and (b) the ![]() point. The Hamiltonian near the

point. The Hamiltonian near the ![]() or

or ![]() point is obtained by rotating the coordinate from the gray axes to the black axes. The angle

point is obtained by rotating the coordinate from the gray axes to the black axes. The angle ![]() is measured with respect to the rotated

is measured with respect to the rotated ![]() axis.

axis.

Similarly, the Hamiltonian near the ![]() point is obtained by substituting

point is obtained by substituting ![]() with

with ![]() in (1.15) and taking the unitary transformation by rotating the axes 30 degrees clockwise; the result for

in (1.15) and taking the unitary transformation by rotating the axes 30 degrees clockwise; the result for ![]() is

is

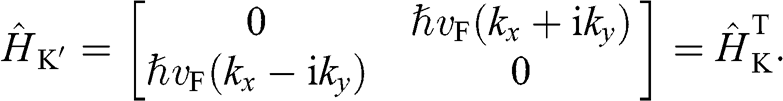

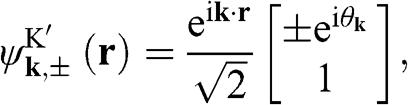

(1.29)

(1.29)

The eigenfunctions are

(1.30)

(1.30)

where the ![]() signs correspond to the signs of the eigenenergies given in (1.22), and

signs correspond to the signs of the eigenenergies given in (1.22), and ![]() is the polar angle measured between

is the polar angle measured between ![]() and the rotated

and the rotated ![]() axis at the

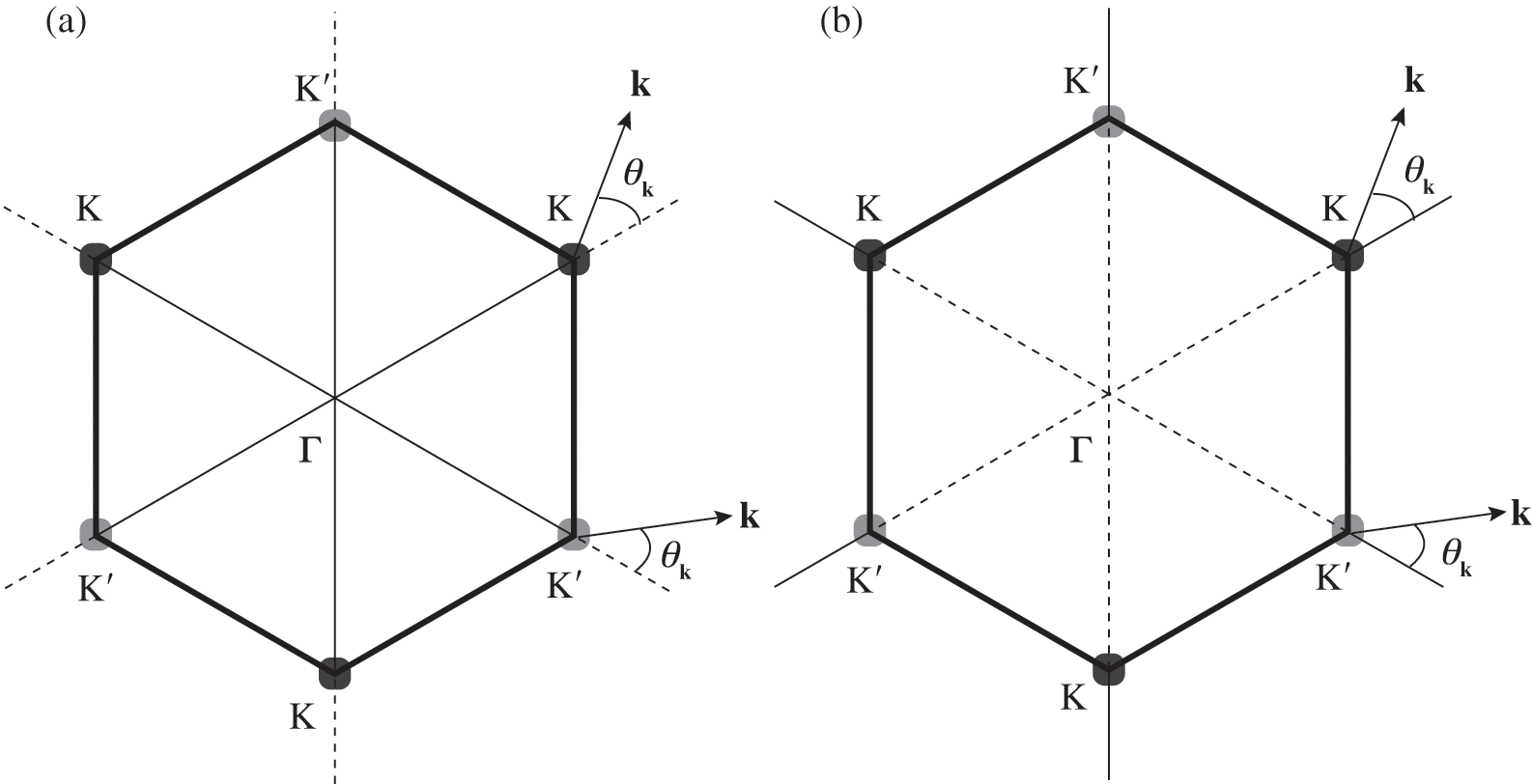

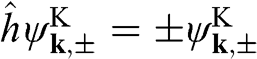

axis at the ![]() point, as shown in Figure 1.3(b). From (1.28) and (1.30), it is clear that for the conduction band, the eigenstate is antibonding at

point, as shown in Figure 1.3(b). From (1.28) and (1.30), it is clear that for the conduction band, the eigenstate is antibonding at ![]() and bonding at

and bonding at ![]() , as shown in Figure 1.4(a). By contrast, the eigenstate is bonding at

, as shown in Figure 1.4(a). By contrast, the eigenstate is bonding at ![]() and antibonding at

and antibonding at ![]() for the valence band, as shown in Figure 1.4(b).

for the valence band, as shown in Figure 1.4(b).

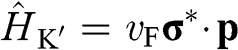

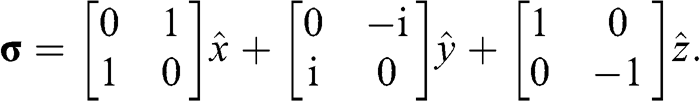

Equations (1.27) and (1.29) are often written as

for an electron near a ![]() point and as

point and as

(1.32)

(1.32)

for an electron near a ![]() point, where

point, where ![]() and

and ![]() is the Pauli vector:

is the Pauli vector:

(1.33)

(1.33)

Note that ![]() with

with ![]() for the

for the ![]() electrons in monolayer graphene because they only move through the graphene lattice on the xy plane of a monolayer graphene sheet.

electrons in monolayer graphene because they only move through the graphene lattice on the xy plane of a monolayer graphene sheet.

Figure 1.4 Antibonding (solid thin lines) and bonding (dotted lines) states in (a) the conduction band and (b) the valence band.

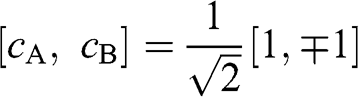

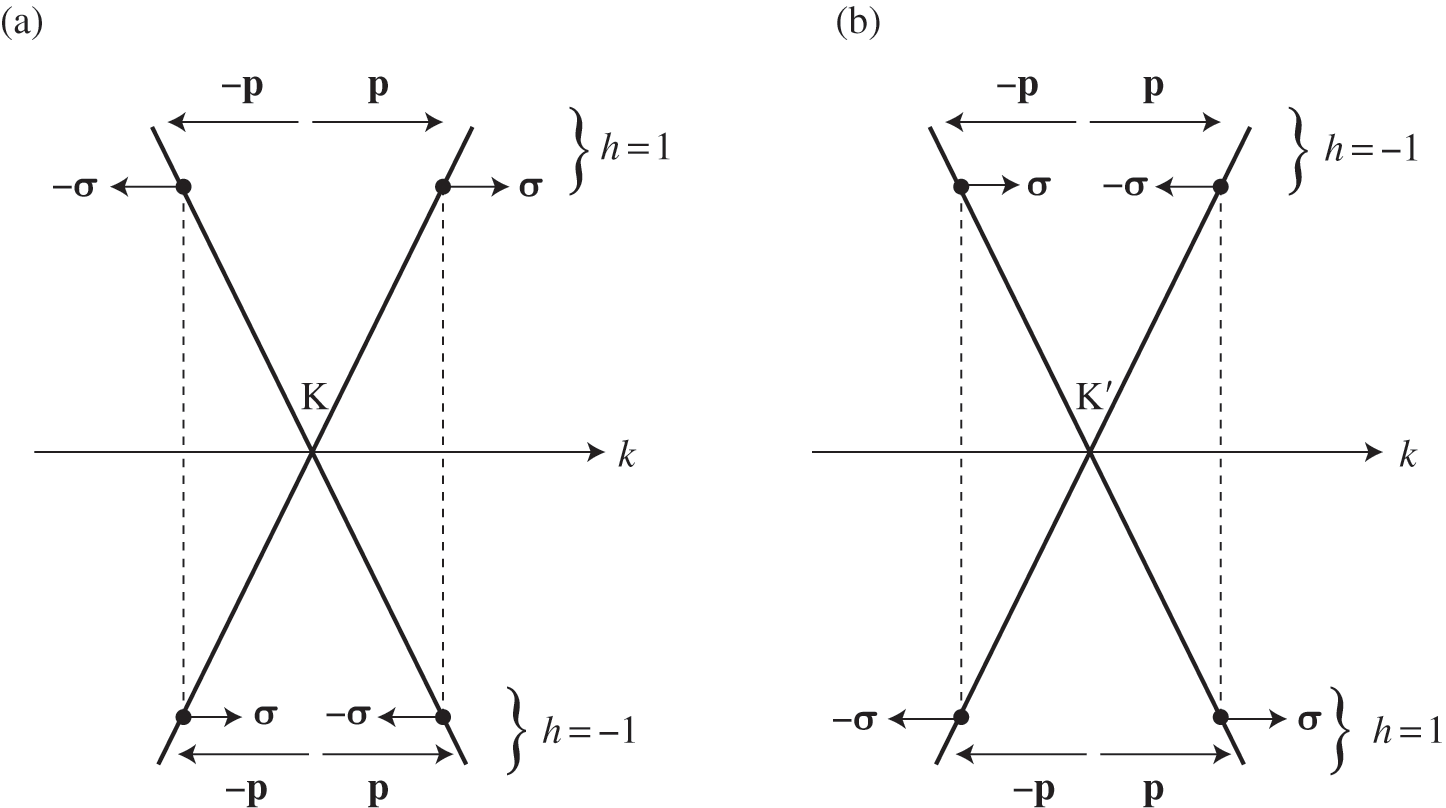

In fact, the Hamiltonian of graphene near a ![]() or

or ![]() point has the form identical to that of a spin one-half particle in a magnetic field; its eigenfunctions are two-component spinors, as seen in (1.28) and (1.30). In the case of graphene,

point has the form identical to that of a spin one-half particle in a magnetic field; its eigenfunctions are two-component spinors, as seen in (1.28) and (1.30). In the case of graphene, ![]() does not really represent an electronic spin, but a pseudospin that indicates the sublattice on which the electron is located. We can define a helicity operator

does not really represent an electronic spin, but a pseudospin that indicates the sublattice on which the electron is located. We can define a helicity operator  to find the projection of the momentum along the pseudospin direction; then it can be shown that

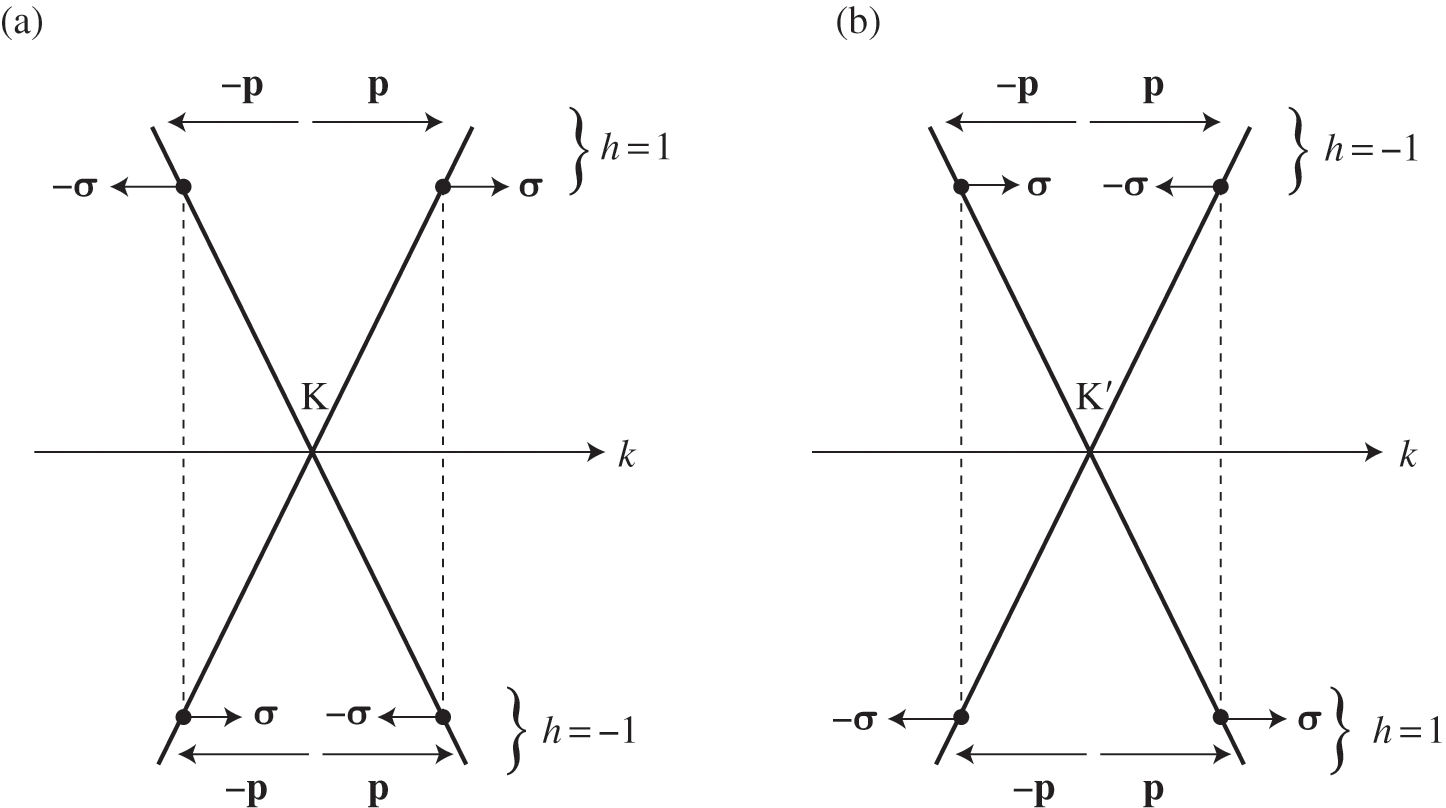

to find the projection of the momentum along the pseudospin direction; then it can be shown that  . The positive sign gives positive helicity, meaning that the momentum of an electron on the conduction band is parallel to the pseudospin, whereas the negative sign gives negative helicity, meaning that the momentum of an electron on the valence band is antiparallel to the pseudospin. The relation among the helicity, the carrier momentum, and the pseudospin are shown in Figure 1.5. Because of the conservation of pseudospin, a right-moving electron on the conduction band cannot be scattered into a left-moving electron on the conduction band or into a right-moving electron on the valence band. Such scattering requires the pseudospin to be flipped from

. The positive sign gives positive helicity, meaning that the momentum of an electron on the conduction band is parallel to the pseudospin, whereas the negative sign gives negative helicity, meaning that the momentum of an electron on the valence band is antiparallel to the pseudospin. The relation among the helicity, the carrier momentum, and the pseudospin are shown in Figure 1.5. Because of the conservation of pseudospin, a right-moving electron on the conduction band cannot be scattered into a left-moving electron on the conduction band or into a right-moving electron on the valence band. Such scattering requires the pseudospin to be flipped from ![]() to

to ![]() for an electron near the K point, or flipped from

for an electron near the K point, or flipped from ![]() to

to ![]() for an electron near the

for an electron near the ![]() point, neither of which is allowed. Similarly, scattering of a left-moving electron on the conduction band into a right-moving electron on the conduction band or into a left-moving electron on the valence band is also forbidden. Nevertheless, such scattering events can happen when there exists a short-range potential that acts differently on sublattices A and B, thus breaking the symmetry between the two sublattices.

point, neither of which is allowed. Similarly, scattering of a left-moving electron on the conduction band into a right-moving electron on the conduction band or into a left-moving electron on the valence band is also forbidden. Nevertheless, such scattering events can happen when there exists a short-range potential that acts differently on sublattices A and B, thus breaking the symmetry between the two sublattices.

Figure 1.5 Helicity h, pseudospin ![]() , and momentum

, and momentum ![]() of an electron near (a) the

of an electron near (a) the ![]() point, and (b) the

point, and (b) the ![]() point. The directions of

point. The directions of ![]() and

and ![]() are shown. In the case of a hole, the direction of momentum is reversed. Due to the conservation of pseudospin, an electron or a hole cannot be scattered into an electron or a hole of a different pseudospin.

are shown. In the case of a hole, the direction of momentum is reversed. Due to the conservation of pseudospin, an electron or a hole cannot be scattered into an electron or a hole of a different pseudospin.

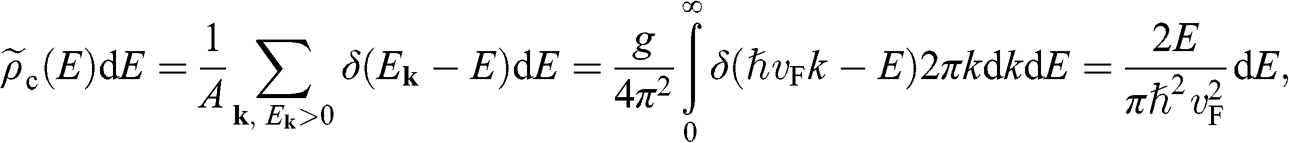

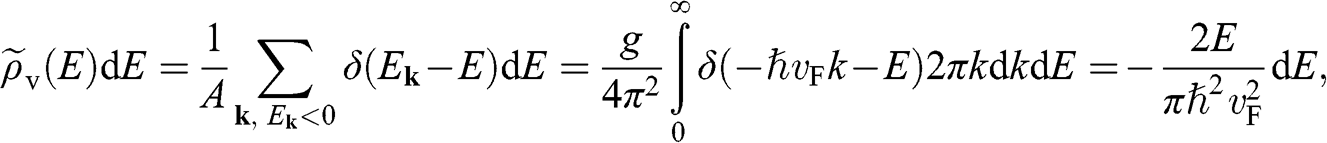

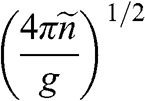

1.2 Density of States and Carrier Concentration

With the band structure near the Dirac point described by (1.22), the density of electron states of graphene in the energy range between ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() near the conduction band edge is

near the conduction band edge is

(1.34)

(1.34)

and that for ![]() near the valence band edge is

near the valence band edge is

(1.35)

(1.35)

where ![]() is the area of the graphene sheet and

is the area of the graphene sheet and ![]() is the total degeneracy due to the spin degeneracy and the valley degeneracy (two valleys

is the total degeneracy due to the spin degeneracy and the valley degeneracy (two valleys ![]() and

and ![]() in one Brillouin zone). Because of the symmetry between the conduction band and the valence band with respect to the Dirac point,

in one Brillouin zone). Because of the symmetry between the conduction band and the valence band with respect to the Dirac point, ![]() for the same absolute value

for the same absolute value ![]() of energy.

of energy.

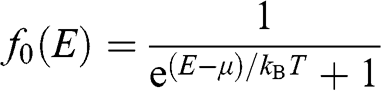

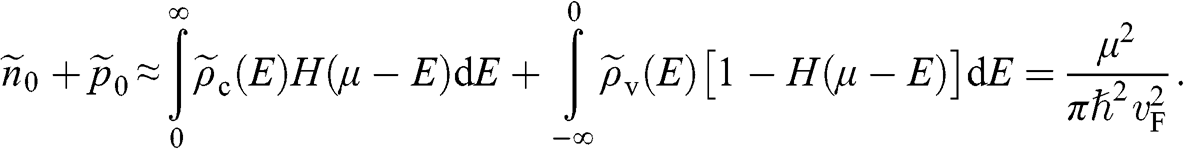

From (1.34) and (1.35), the surface concentrations of electrons and holes of a graphene sheet are, respectively,

(1.36)

(1.36)

where

(1.37)

(1.37)

is the equilibrium Fermi–Dirac distribution function for a chemical potential ![]() at a temperature T, and

at a temperature T, and ![]() is the Boltzmann constant. The probability of finding an electron in a state at the energy level E is

is the Boltzmann constant. The probability of finding an electron in a state at the energy level E is ![]() , and the probability of finding a hole in a state at the energy level E is

, and the probability of finding a hole in a state at the energy level E is ![]() . When the condition

. When the condition ![]() is satisfied,

is satisfied, ![]() is approximately a Heaviside step function

is approximately a Heaviside step function ![]() , which has a value of 1 for

, which has a value of 1 for ![]() and 0 for

and 0 for ![]() . Therefore, for

. Therefore, for ![]() ,

,

(1.38)

(1.38)

In this book, we use a tilde for a 2D quantity to clearly distinguish it from its 3D counterpart in order to avoid confusion. Therefore, the surface electron density ![]() , the surface hole density

, the surface hole density ![]() , and the densities of states

, and the densities of states ![]() and

and ![]() of graphene are all numbers per unit area in the unit of

of graphene are all numbers per unit area in the unit of ![]() , or

, or ![]() ; whereas their 3D counterparts,

; whereas their 3D counterparts, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , are all numbers per unit volume in the unit of

, are all numbers per unit volume in the unit of ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

1.3 Fermi Energy, Chemical Potential, and Fermi Level

Here we clarify the terminologies and notations that are sometimes swapped or not clear in some books and literature: the Fermi energy ![]() , the chemical potential

, the chemical potential ![]() , and the Fermi level. The Fermi energy

, and the Fermi level. The Fermi energy ![]() is defined as the energy difference between the highest energy level and the lowest energy level that are occupied by electrons at the absolute zero temperature,

is defined as the energy difference between the highest energy level and the lowest energy level that are occupied by electrons at the absolute zero temperature, ![]() . Therefore, the Fermi energy is defined only at

. Therefore, the Fermi energy is defined only at ![]() ; it is theoretically defined but experimentally cannot be exactly measured because the absolute temperature can never truly reach zero. For a metal, the Fermi energy is usually taken to be the kinetic energy of the electron that occupies the highest energy level at

; it is theoretically defined but experimentally cannot be exactly measured because the absolute temperature can never truly reach zero. For a metal, the Fermi energy is usually taken to be the kinetic energy of the electron that occupies the highest energy level at ![]() ; therefore, it is always positive. For graphene, we take the Fermi energy to be the total energy of the electron that occupies the highest energy level at

; therefore, it is always positive. For graphene, we take the Fermi energy to be the total energy of the electron that occupies the highest energy level at ![]() , which can be either positive or negative, or zero, if the reference point of zero energy is defined at the Dirac point, as seen below. By contrast, the chemical potential is meaningful at any temperature because it is a statistical reference for the total energy, including the potential energy and the kinetic energy, of a particle in a system in thermal equilibrium. In solid-state physics, the chemical potential

, which can be either positive or negative, or zero, if the reference point of zero energy is defined at the Dirac point, as seen below. By contrast, the chemical potential is meaningful at any temperature because it is a statistical reference for the total energy, including the potential energy and the kinetic energy, of a particle in a system in thermal equilibrium. In solid-state physics, the chemical potential ![]() usually refers to the change of free energy when an additional electron is added to a system. The effect of

usually refers to the change of free energy when an additional electron is added to a system. The effect of ![]() is best observed in the Fermi–Dirac distribution

is best observed in the Fermi–Dirac distribution ![]() , where one can see that at zero temperature, the minimum energy required to add an additional electron is

, where one can see that at zero temperature, the minimum energy required to add an additional electron is ![]() because below it electronic states are all occupied. In the electronic devices context, the term Fermi level usually refers to the chemical potential

because below it electronic states are all occupied. In the electronic devices context, the term Fermi level usually refers to the chemical potential ![]() . However, in semiconductor physics, the Fermi level is usually denoted by the symbol

. However, in semiconductor physics, the Fermi level is usually denoted by the symbol ![]() though it refers to the chemical potential

though it refers to the chemical potential ![]() . To avoid confusion with the Fermi energy, in this book we use the symbol

. To avoid confusion with the Fermi energy, in this book we use the symbol ![]() to represent only the Fermi energy while using the symbol

to represent only the Fermi energy while using the symbol ![]() to represent the chemical potential and the Fermi level.

to represent the chemical potential and the Fermi level.

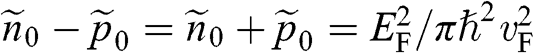

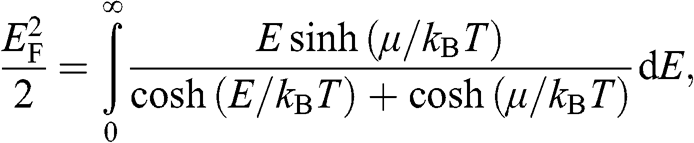

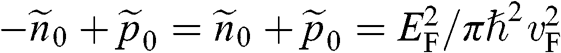

From the above discussions, we see that ![]() is a function of temperature:

is a function of temperature: ![]() . In the case when

. In the case when ![]() lies within the conduction band,

lies within the conduction band, ![]() is positive and can be found from the definition

is positive and can be found from the definition ![]() at zero temperature. In the case when

at zero temperature. In the case when ![]() lies within the valence band, we define

lies within the valence band, we define ![]() to be negative using the definition

to be negative using the definition ![]() at zero temperature. The temperature dependence of

at zero temperature. The temperature dependence of ![]() of graphene can be found by recognizing the fact that each additional thermally excited electron always comes with the creation of a hole to result in an electron–hole pair. Therefore, for a given piece of graphene, the difference between the electron concentration and the hole concentration,

of graphene can be found by recognizing the fact that each additional thermally excited electron always comes with the creation of a hole to result in an electron–hole pair. Therefore, for a given piece of graphene, the difference between the electron concentration and the hole concentration, ![]() , is a conserved quantity that is independent of temperature. In the case when

, is a conserved quantity that is independent of temperature. In the case when ![]() at zero temperature so that the chemical potential lies within the conduction band, we have

at zero temperature so that the chemical potential lies within the conduction band, we have ![]() and

and  from (1.38). Therefore we can relate

from (1.38). Therefore we can relate ![]() and

and ![]() by combining (1.36) and (1.38) to write

by combining (1.36) and (1.38) to write

(1.39)

(1.39)

which can be written in a compact form:

(1.40)

(1.40)

from which ![]() can be numerically obtained. In the case when

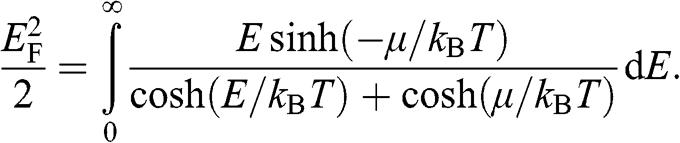

can be numerically obtained. In the case when ![]() lies within the valence band so that

lies within the valence band so that ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() and

and  from (1.38). Then, following a procedure similar to the above, we obtain

from (1.38). Then, following a procedure similar to the above, we obtain

(1.41)

(1.41)

When ![]() , the integrals for both (1.40) and (1.41) approach

, the integrals for both (1.40) and (1.41) approach ![]() , and we have

, and we have ![]() .

.

1.4 Temperature Dependence of Carrier Concentration

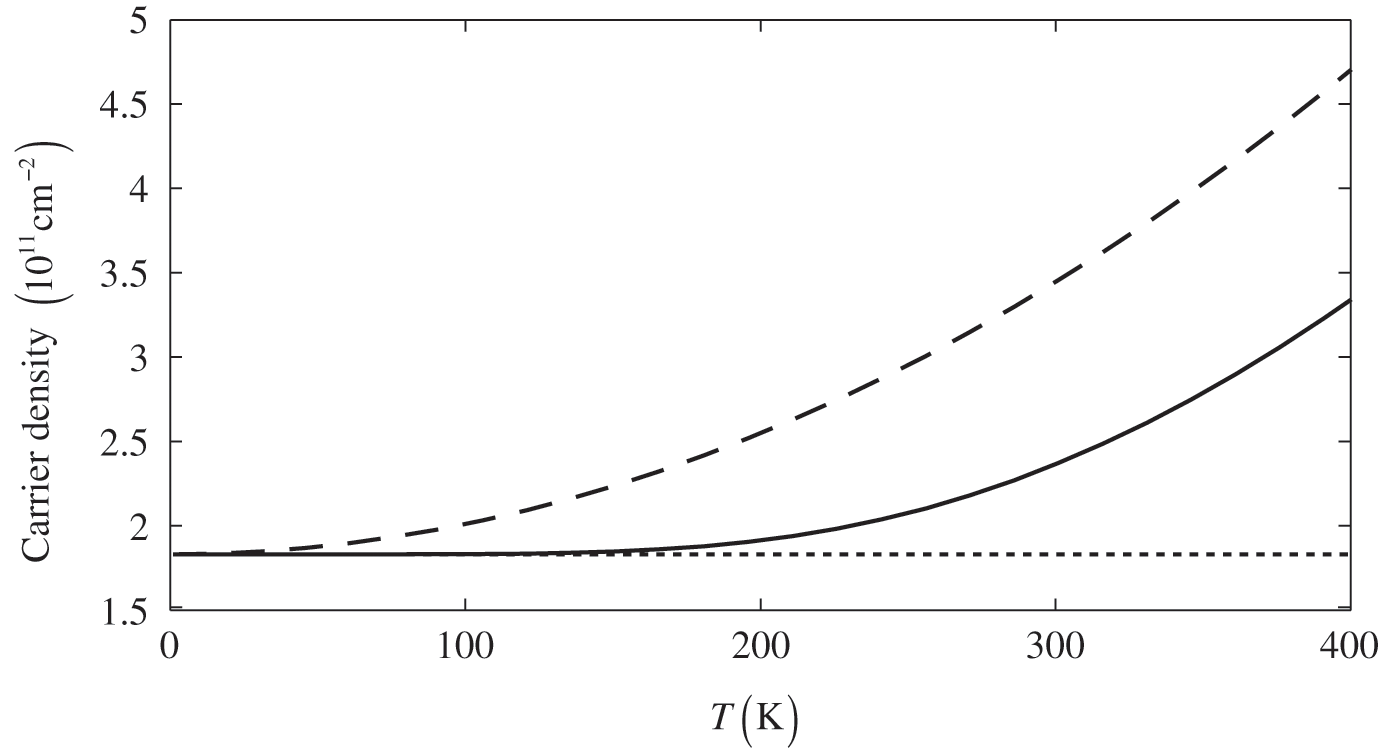

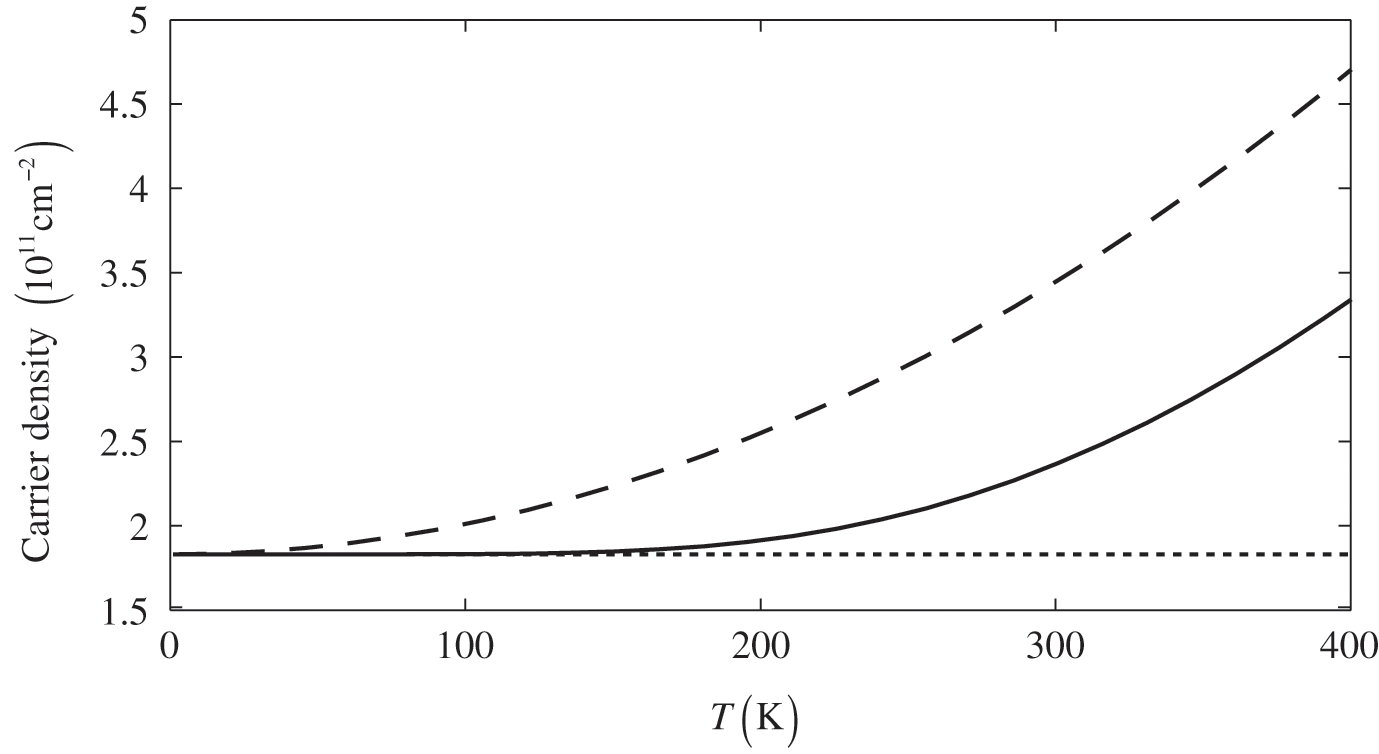

The dependence of the free carrier concentration ![]() of graphene on temperature is shown in Figure 1.6 for

of graphene on temperature is shown in Figure 1.6 for ![]() . The characteristics obtained under two different approximations are compared to the exact temperature dependence of the carrier concentration obtained without approximations. The dotted line is the low-temperature approximation given by (1.38), and the dashed curve is obtained from (1.36) by assuming

. The characteristics obtained under two different approximations are compared to the exact temperature dependence of the carrier concentration obtained without approximations. The dotted line is the low-temperature approximation given by (1.38), and the dashed curve is obtained from (1.36) by assuming ![]() independent of temperature. The solid curve is the exact result calculated from (1.36), with

independent of temperature. The solid curve is the exact result calculated from (1.36), with ![]() varying with temperature obtained from (1.40). As can be seen, the dotted line is accurate only when the temperature is low, and the dashed curve overestimates the carrier concentration. In general, a higher temperature leads to a higher carrier concentration because of thermally excited electron–hole pairs.

varying with temperature obtained from (1.40). As can be seen, the dotted line is accurate only when the temperature is low, and the dashed curve overestimates the carrier concentration. In general, a higher temperature leads to a higher carrier concentration because of thermally excited electron–hole pairs.

Figure 1.6 Carrier concentration for ![]() as a function of temperature calculated under different assumptions. The dotted line and the dashed curve are obtained under the low-temperature approximation and the constant

as a function of temperature calculated under different assumptions. The dotted line and the dashed curve are obtained under the low-temperature approximation and the constant ![]() approximation, respectively, while the solid curve is the exact result.

approximation, respectively, while the solid curve is the exact result.

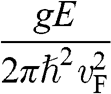

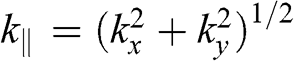

1.5 Carrier Velocity and Effective Mass

In the preceding sections, we regard a charge carrier in graphene as a wave that has a momentum of ![]() and an energy of

and an energy of ![]() . In this section, we treat the wave packet as a particle that has a velocity equal to the group velocity of its wave packet. For an isotropic two-dimensional material such as graphene, the phase velocity

. In this section, we treat the wave packet as a particle that has a velocity equal to the group velocity of its wave packet. For an isotropic two-dimensional material such as graphene, the phase velocity ![]() and the group velocity

and the group velocity ![]() of an electron that has a momentum of

of an electron that has a momentum of ![]() and an energy of

and an energy of ![]() are, respectively,

are, respectively,

(1.42)

(1.42)

For an electron in graphene near a Dirac point, the carrier energy is linearly proportional to the momentum: ![]() ; thus, we find that

; thus, we find that  , independent of the electron energy. The same conclusion applies to a hole in graphene near a Dirac point. Therefore, the parameter

, independent of the electron energy. The same conclusion applies to a hole in graphene near a Dirac point. Therefore, the parameter ![]() represents both the group velocity and the phase velocity of a carrier in graphene. The parameter

represents both the group velocity and the phase velocity of a carrier in graphene. The parameter ![]() also represents the Fermi velocity because a carrier that has a kinetic energy equal to the Fermi energy also moves at a group velocity of

also represents the Fermi velocity because a carrier that has a kinetic energy equal to the Fermi energy also moves at a group velocity of ![]() in the vicinity of a Dirac point. This result is distinctively different from the energy-dependent group velocity

in the vicinity of a Dirac point. This result is distinctively different from the energy-dependent group velocity  of a carrier in an ordinary material, where

of a carrier in an ordinary material, where ![]() is the effective mass of an electron in the conduction band of the material or that of a hole in the valence band.

is the effective mass of an electron in the conduction band of the material or that of a hole in the valence band.

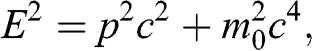

The linear energy–momentum relation of the carriers in graphene resembles the relativistic Dirac equation. Unlike the Schrödinger equation, the Dirac equation accounts for special relativity through the relativistic energy–momentum relation:

(1.43)

(1.43)

where ![]() is the particle momentum,

is the particle momentum, ![]() is the rest mass of the particle, and c is the speed of light. If we compare the energy–momentum relation given in (1.22) for a carrier in graphene with the relativistic energy–momentum relation given in (1.43), we find that a carrier in graphene has an effective speed of

is the rest mass of the particle, and c is the speed of light. If we compare the energy–momentum relation given in (1.22) for a carrier in graphene with the relativistic energy–momentum relation given in (1.43), we find that a carrier in graphene has an effective speed of ![]() and a zero effective rest mass of

and a zero effective rest mass of ![]() . Therefore, the carriers in graphene are often called massless Dirac fermions.

. Therefore, the carriers in graphene are often called massless Dirac fermions.

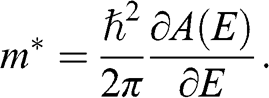

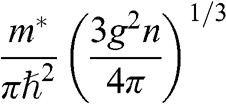

In contrast to the effective rest mass, an effective mass associated with the acceleration of a carrier in graphene under the influence of an external force can be defined. For example, when a carrier in graphene is accelerated by an external magnetic field, the carrier follows a circular orbit dictated by Maxwell’s equations. If the area enclosed by the orbit is ![]() , the cyclotron effective mass is defined as [Reference Castro Neto, Guinea, Peres, Novoselov and Geim6,Reference Miller, Kubista and Rutter8,Reference Novoselov, Geim and Morozov9]

, the cyclotron effective mass is defined as [Reference Castro Neto, Guinea, Peres, Novoselov and Geim6,Reference Miller, Kubista and Rutter8,Reference Novoselov, Geim and Morozov9]

(1.44)

(1.44)

With ![]() and

and  , we obtain

, we obtain

(1.45)

(1.45)

Therefore, the cyclotron effective mass is energy dependent, and (1.45) manifests the mass–energy equivalence from special relativity, namely, ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

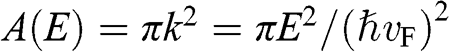

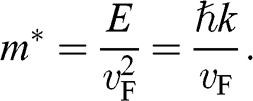

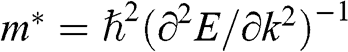

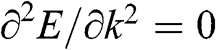

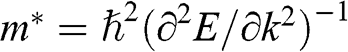

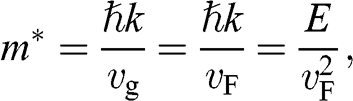

In solid-state physics, the effective mass of a charge carrier is often calculated as  because the energy of a carrier is quadratically dependent on its momentum near a conduction band minimum or a valence band maximum of an ordinary three-dimensional solid-state material. However, in the case of graphene, this relation is invalid because it gives a mathematically divergent result due to the fact that

because the energy of a carrier is quadratically dependent on its momentum near a conduction band minimum or a valence band maximum of an ordinary three-dimensional solid-state material. However, in the case of graphene, this relation is invalid because it gives a mathematically divergent result due to the fact that  for a carrier in graphene. The reason is that the energy of a carrier in graphene near a Dirac point varies with its momentum not quadratically but linearly:

for a carrier in graphene. The reason is that the energy of a carrier in graphene near a Dirac point varies with its momentum not quadratically but linearly: ![]() from (1.22). Thus the assumption of a constant effective mass given by

from (1.22). Thus the assumption of a constant effective mass given by  is not valid for a carrier in graphene. Instead,

is not valid for a carrier in graphene. Instead, ![]() for a carrier in graphene can be calculated using the momentum relation

for a carrier in graphene can be calculated using the momentum relation ![]() so that

so that

(1.46)

(1.46)

which gives a result that is consistent with (1.45). This relation yields ![]() at the Dirac point where

at the Dirac point where ![]() ; this result is also conceptually consistent with the zero effective rest mass for a carrier in graphene discussed above.

; this result is also conceptually consistent with the zero effective rest mass for a carrier in graphene discussed above.

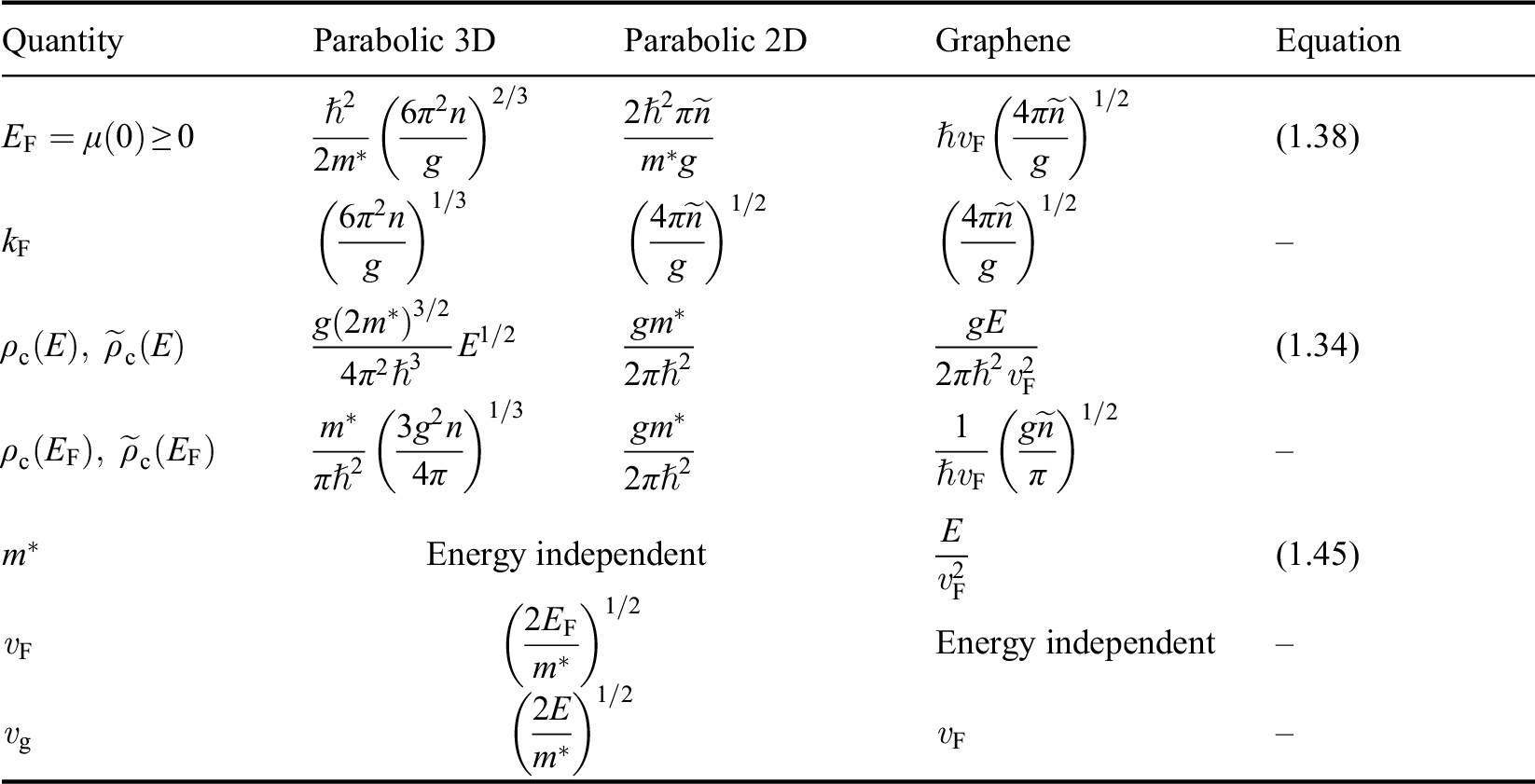

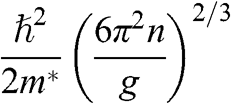

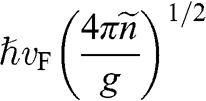

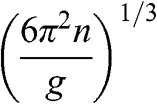

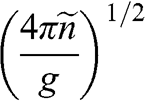

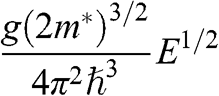

The comparison of parabolic 2D/3D systems and monolayer graphene for various physical quantities is presented in Table 1.1.

| Quantity | Parabolic 3D | Parabolic 2D | Graphene | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| (1.38) | |

|

|

| – | |

|

|

| (1.34) | |

|

|

| – | |

| Energy independent | (1.45) | |||

| Energy independent | – | ||

| – | |||

a: In this table, the parameters of an electron in a conduction band are listed; those of a hole in a valence band can be similarly expressed. ![]() is the energy of the electron measured with respect to the conduction band edge, by setting

is the energy of the electron measured with respect to the conduction band edge, by setting ![]() for the conduction band minimum of a parabolic system and

for the conduction band minimum of a parabolic system and ![]() for graphene.

for graphene. ![]() is the electron density of a 3D system and

is the electron density of a 3D system and ![]() is the electron density of a 2D system including graphene, in the limit that

is the electron density of a 2D system including graphene, in the limit that ![]() .

. ![]() is the total degeneracy including spin degeneracy.

is the total degeneracy including spin degeneracy.

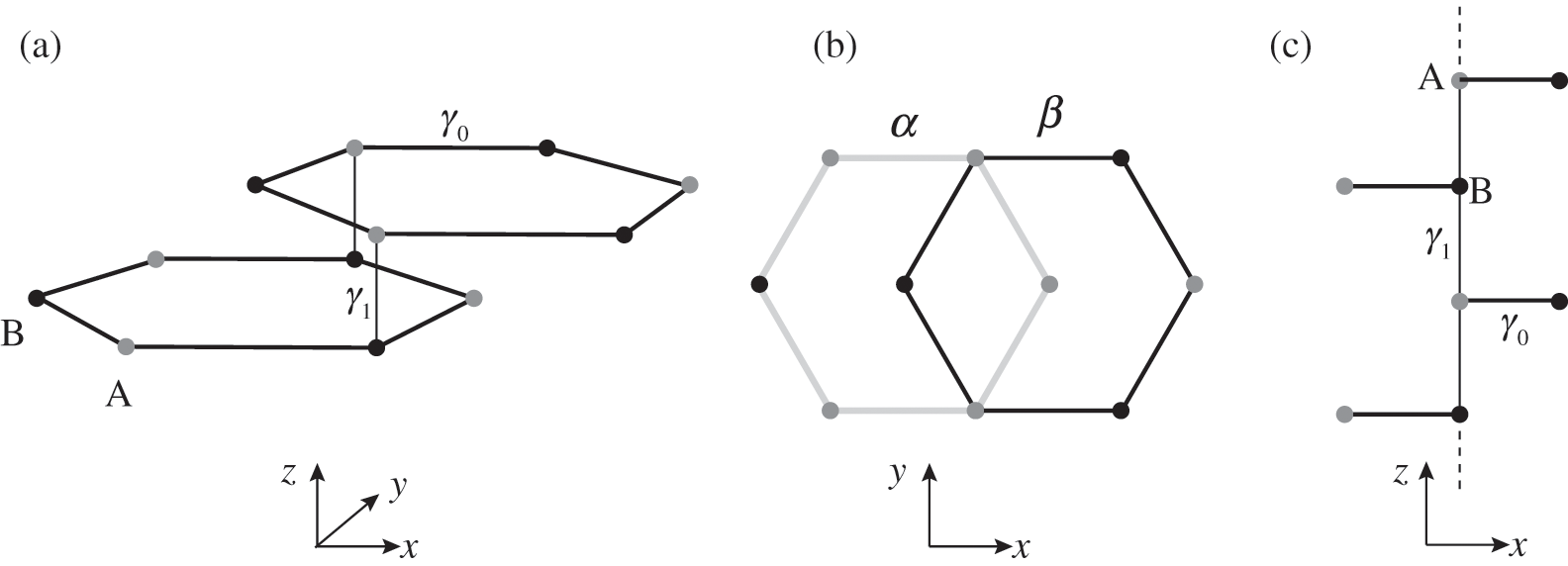

1.6 Band Structure of Multilayer Graphene

When multiple layers of graphene are brought together to form a sheet of multilayer graphene, the interlayer interaction can fundamentally change the band structure. In this section, the band structures of AA and AB (Bernal) stacking orders are derived. Other possible stacking arrangements are discussed at the end.

1.6.1 AB Stacking Order

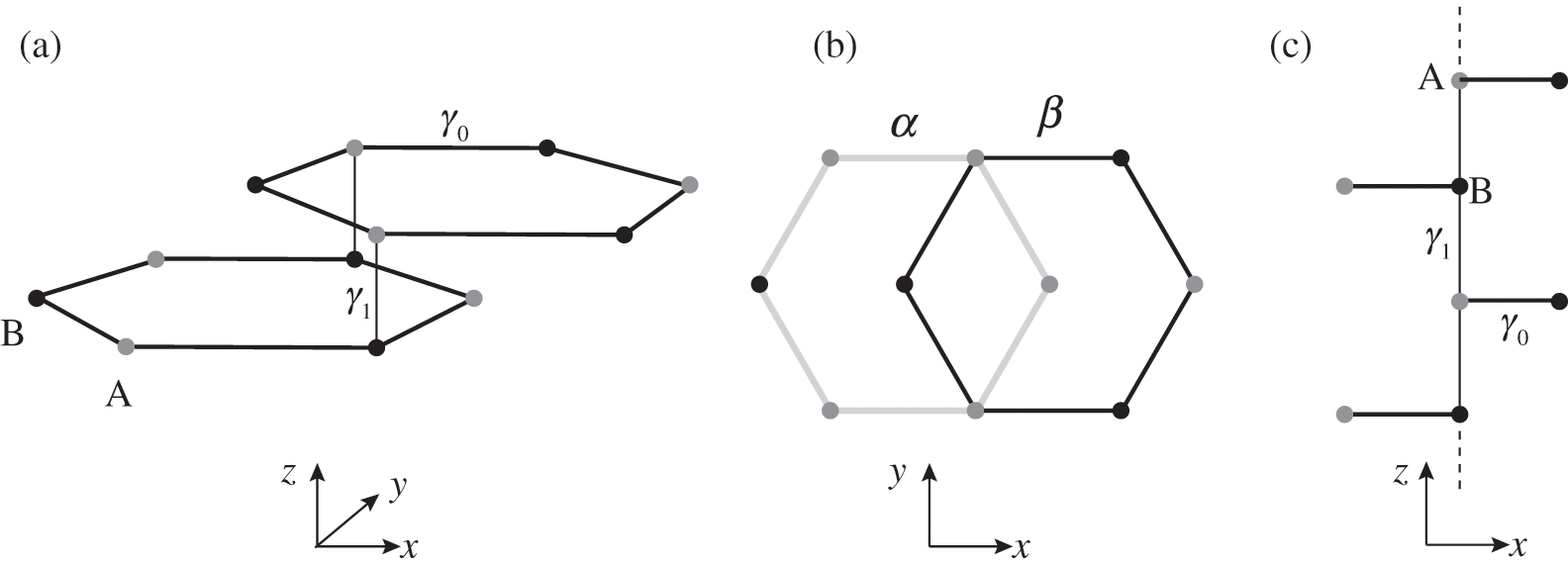

In AB-stacked multilayer graphene, the arrangement of layers follows the αβαβ … order. Figure 1.7 illustrates the AB stacking by showing one set of α and β layers. Nearest-neighbor intralayer and interlayer interactions are considered, as shown in Figure 1.7(a); high-order interactions beyond nearest neighbors are neglected for simplicity. The intralayer interaction energy is ![]() , defined in (1.17), whereas the interlayer interaction energy is characterized by a different off-diagonal parameter

, defined in (1.17), whereas the interlayer interaction energy is characterized by a different off-diagonal parameter ![]() in the Hamiltonian. The top layer (β layer) is shifted relative to the bottom layer (α layer) by one C–C distance, as shown in Figure 1.7(b).

in the Hamiltonian. The top layer (β layer) is shifted relative to the bottom layer (α layer) by one C–C distance, as shown in Figure 1.7(b).

Figure 1.7 (a) Intralayer (![]() ) and interlayer (

) and interlayer (![]() ) interactions of AB-stacked multilayer graphene showing one set of α and β layers. (b) Top view of (a), showing the overlap between α (bottom) and β (top) layers. (c) Side view of (a). A chain of alternating A and B carbon atoms connected through interlayer interactions of energy

) interactions of AB-stacked multilayer graphene showing one set of α and β layers. (b) Top view of (a), showing the overlap between α (bottom) and β (top) layers. (c) Side view of (a). A chain of alternating A and B carbon atoms connected through interlayer interactions of energy ![]() along the z direction is shown.

along the z direction is shown.

The band structure of N-layer AB-stacked multilayer graphene can be obtained in a manner similar to the derivation of the band structure of monolayer graphene. As shown in (1.27), after proper transformation the Hamiltonian at the ![]() point for intralayer interactions can be expressed in terms of the energy parameters

point for intralayer interactions can be expressed in terms of the energy parameters ![]() with

with ![]() . Therefore, the tight-binding Hamiltonian at the

. Therefore, the tight-binding Hamiltonian at the ![]() point for AB-stacked multilayer graphene can be expressed in a form similar to (1.27) as [Reference Min and MacDonald10]

point for AB-stacked multilayer graphene can be expressed in a form similar to (1.27) as [Reference Min and MacDonald10]

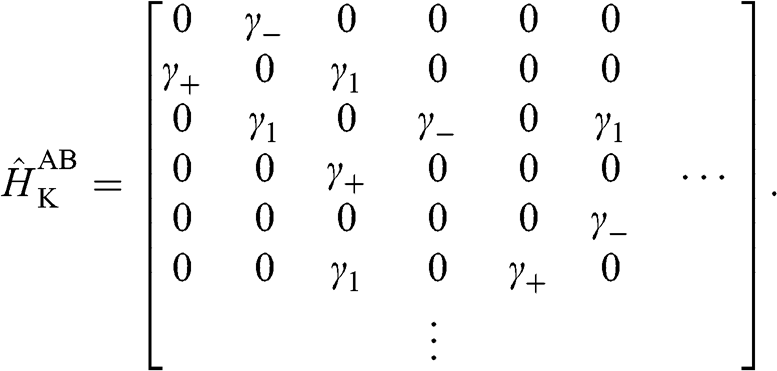

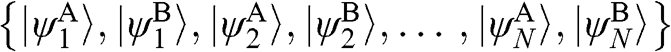

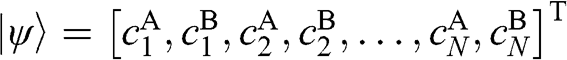

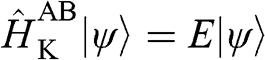

(1.47)

(1.47)

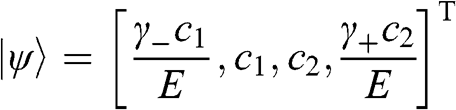

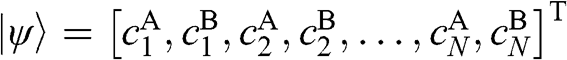

In (1.47), the basis is taken to be  , with the eigenvector

, with the eigenvector  , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() correspond to the sublattice A or B of layer n. By applying the eigenvalue equation

correspond to the sublattice A or B of layer n. By applying the eigenvalue equation  , we find from (1.47) the following coupled difference equations,

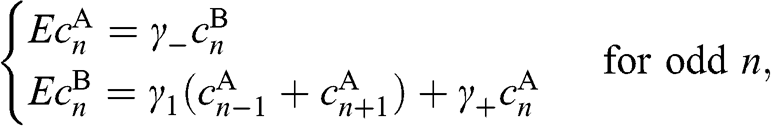

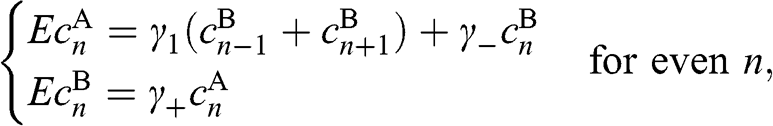

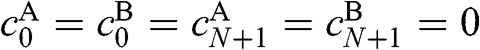

, we find from (1.47) the following coupled difference equations,

(1.48)

(1.48)

(1.49)

(1.49)

where ![]() and

and  .

.

We first check if ![]() is a nontrivial solution for the coupled equations of (1.48) and (1.49). For

is a nontrivial solution for the coupled equations of (1.48) and (1.49). For ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() for odd n and

for odd n and ![]() for even n. If we assume nonzero

for even n. If we assume nonzero ![]() and

and ![]() , we obtain from (1.48) and (1.49) a trivial solution with all c coefficients being zero. However, if we assume

, we obtain from (1.48) and (1.49) a trivial solution with all c coefficients being zero. However, if we assume ![]() , we have rows in (1.47) that are identically zero; thus,

, we have rows in (1.47) that are identically zero; thus, ![]() for even n and

for even n and ![]() for odd n are decoupled and can assume any value. Other coefficients can be either zero or nonzero, determined by (1.48) and (1.49) and the number of layers. Therefore,

for odd n are decoupled and can assume any value. Other coefficients can be either zero or nonzero, determined by (1.48) and (1.49) and the number of layers. Therefore,

represents a nontrivial solution for the coupled equations of (1.48) and (1.49).

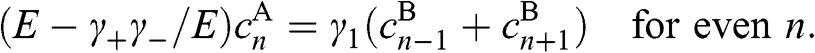

For ![]() , we can simplify (1.48) and (1.49) as

, we can simplify (1.48) and (1.49) as

(1.51)

(1.51)

(1.52)

(1.52)

Then, by defining ![]() for odd n and

for odd n and ![]() for even n, the coupled equations of (1.51) and (1.52) can be expressed in a single simplified form:

for even n, the coupled equations of (1.51) and (1.52) can be expressed in a single simplified form:

where ![]() . Thus we have transformed the original problem expressed in the coupled equations of (1.48) and (1.49) into a chain of N atoms with eigenenergy

. Thus we have transformed the original problem expressed in the coupled equations of (1.48) and (1.49) into a chain of N atoms with eigenenergy ![]() while considering only the nearest-neighbor interactions characterized by the interlayer interaction energy

while considering only the nearest-neighbor interactions characterized by the interlayer interaction energy ![]() , as shown in Figure 1.7(c). With the constraint that

, as shown in Figure 1.7(c). With the constraint that ![]() , we find the solutions of (1.53) as

, we find the solutions of (1.53) as

(1.54)

(1.54)

where ![]() . Therefore, we find N eigenvectors for N-layer graphene. By plugging (1.54) back into (1.53), we find the eigenenergies:

. Therefore, we find N eigenvectors for N-layer graphene. By plugging (1.54) back into (1.53), we find the eigenenergies:

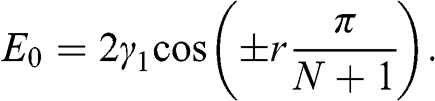

(1.55)

(1.55)

To gain more physical insight for (1.55), we can regard N-layer graphene as a Fabry–Pérot cavity in which an electromagnetic wave is confined in the direction perpendicular to the multilayer graphene surface, which is taken to be the z direction [Reference Mak, Sfeir, Misewich and Heinz11]. The boundary condition ![]() implies that the wave function vanishes at

implies that the wave function vanishes at ![]() and

and ![]() beyond the first and

beyond the first and ![]() layers. The distance between the locations of

layers. The distance between the locations of ![]() and

and ![]() layers is

layers is ![]() ; therefore, the effective length of the Fabry–Pérot cavity is

; therefore, the effective length of the Fabry–Pérot cavity is ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the distance between two neighboring graphene layers in AB stacking. A standing wave can form within the multilayer graphene structure with two opposite wave vectors of equal magnitude in the z direction:

is the distance between two neighboring graphene layers in AB stacking. A standing wave can form within the multilayer graphene structure with two opposite wave vectors of equal magnitude in the z direction:

(1.56)

(1.56)

Therefore, as the thickness of the multilayer graphene increases with the number N of layers, the number of the allowed values of quantized ![]() also increases. By using (1.56), we can rewrite (1.55) as

also increases. By using (1.56), we can rewrite (1.55) as

which gives the eigenenergy of N interacting carbon atoms with ![]() being the wave number along the direction normal to the graphene surface. Indeed, if the in-plane wave numbers have zero values so that

being the wave number along the direction normal to the graphene surface. Indeed, if the in-plane wave numbers have zero values so that ![]() and

and ![]() , the original problem represented by (1.48) is tantamount to the chain of carbon atoms along the z direction shown in Figure 1.7(c). The eigenenergy is simply

, the original problem represented by (1.48) is tantamount to the chain of carbon atoms along the z direction shown in Figure 1.7(c). The eigenenergy is simply ![]() because

because ![]() in the relation

in the relation ![]() .

.

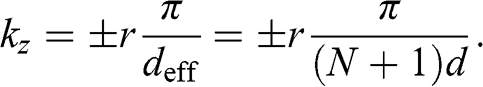

When ![]() and

and ![]() are not both zero so that

are not both zero so that ![]() and

and ![]() , the eigenenergy E can be found from the relation

, the eigenenergy E can be found from the relation ![]() , which gives

, which gives

(1.58)

(1.58)

where  is the in-plane wave number, in contrast to the out-of-plane wave number

is the in-plane wave number, in contrast to the out-of-plane wave number ![]() . In the limit that

. In the limit that ![]() , (1.58) has two small-

, (1.58) has two small-![]() solutions:

solutions:

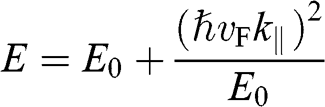

(1.59)

(1.59)

and

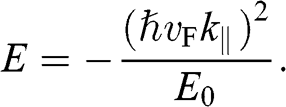

(1.60)

(1.60)

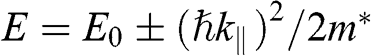

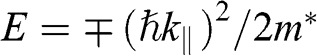

Note that in both (1.59) and (1.60), ![]() varies quadratically, not linearly, with

varies quadratically, not linearly, with ![]() . By defining the effective mass for these quadratic bands as

. By defining the effective mass for these quadratic bands as ![]() , the first solution (1.59) has the form of

, the first solution (1.59) has the form of  , and the second solution (1.60) has the form of

, and the second solution (1.60) has the form of  , where the upper signs are taken when

, where the upper signs are taken when ![]() and the lower signs are taken when

and the lower signs are taken when ![]() . Accordingly, the energy bands given by (1.59) and (1.60) are called massive bands, in contrast to the massless Dirac bands of monolayer graphene.

. Accordingly, the energy bands given by (1.59) and (1.60) are called massive bands, in contrast to the massless Dirac bands of monolayer graphene.

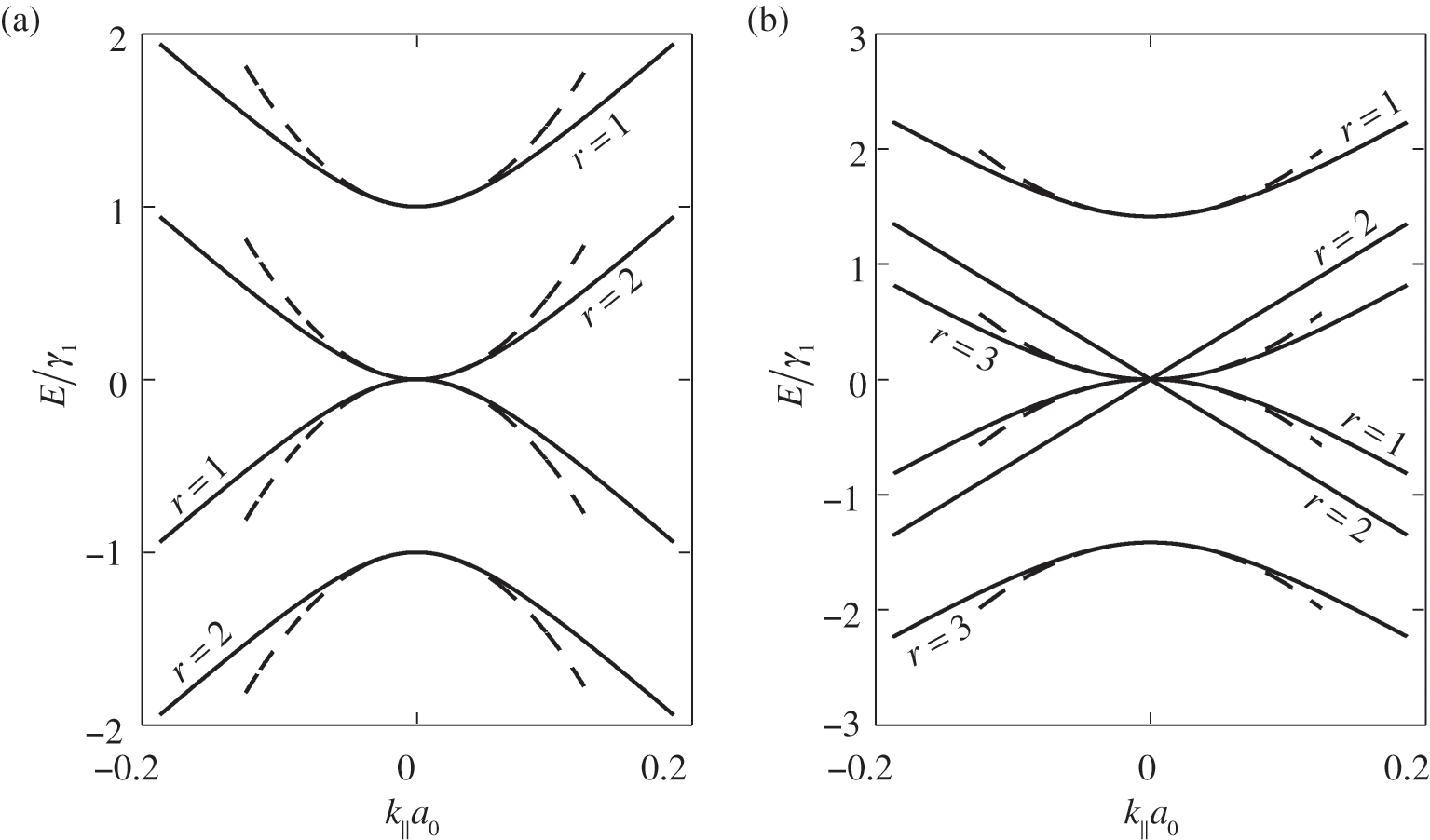

For even N, there are N different values of ![]() given by (1.55). Therefore, (1.59) and (1.60) respectively give N energy bands and thus together a total of 2N massive energy bands. Because half of

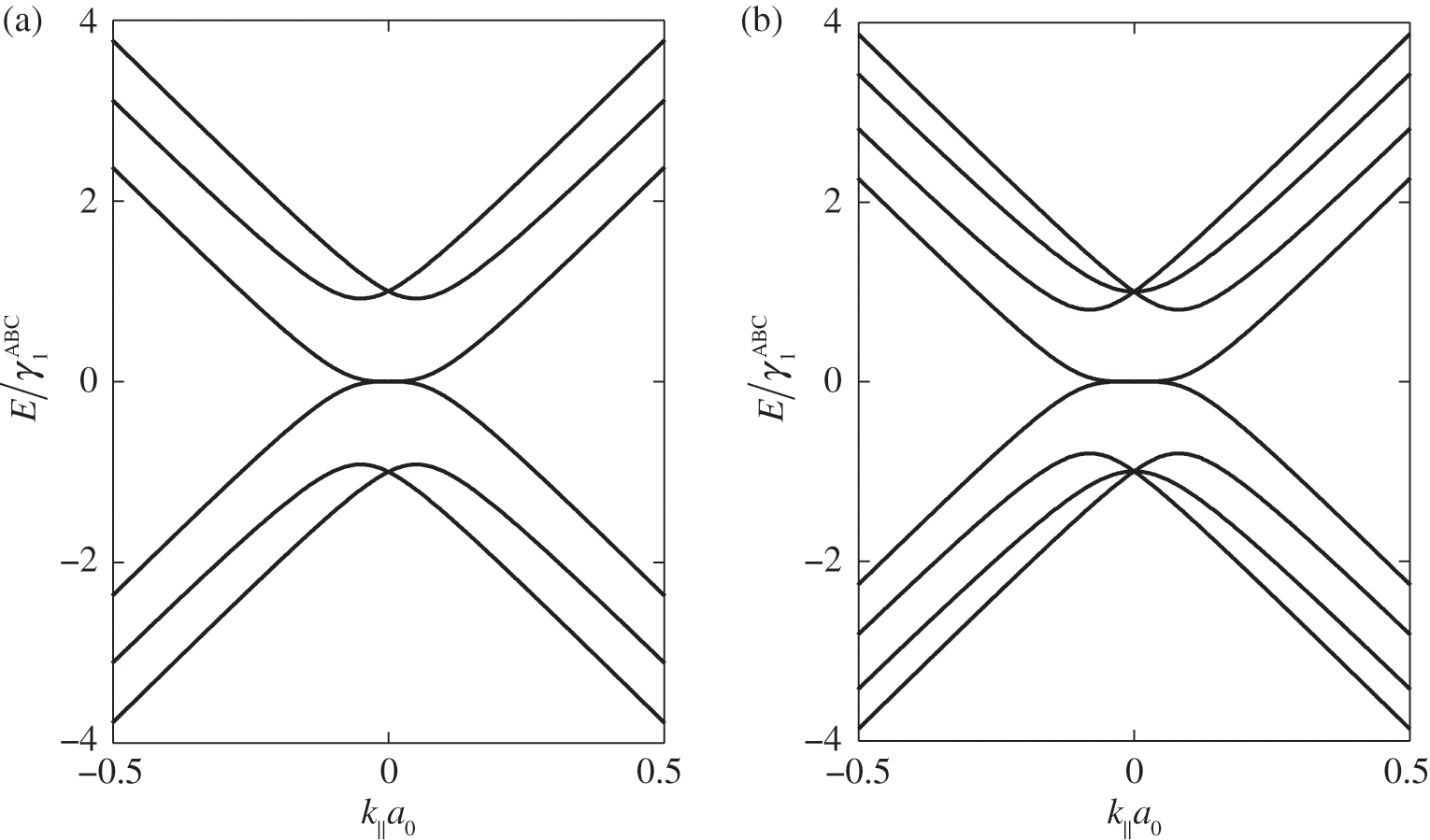

given by (1.55). Therefore, (1.59) and (1.60) respectively give N energy bands and thus together a total of 2N massive energy bands. Because half of ![]() values are positive and the other half are negative, there are N conduction bands and N valence bands. As an example, the band structure of AB-stacked bilayer graphene (

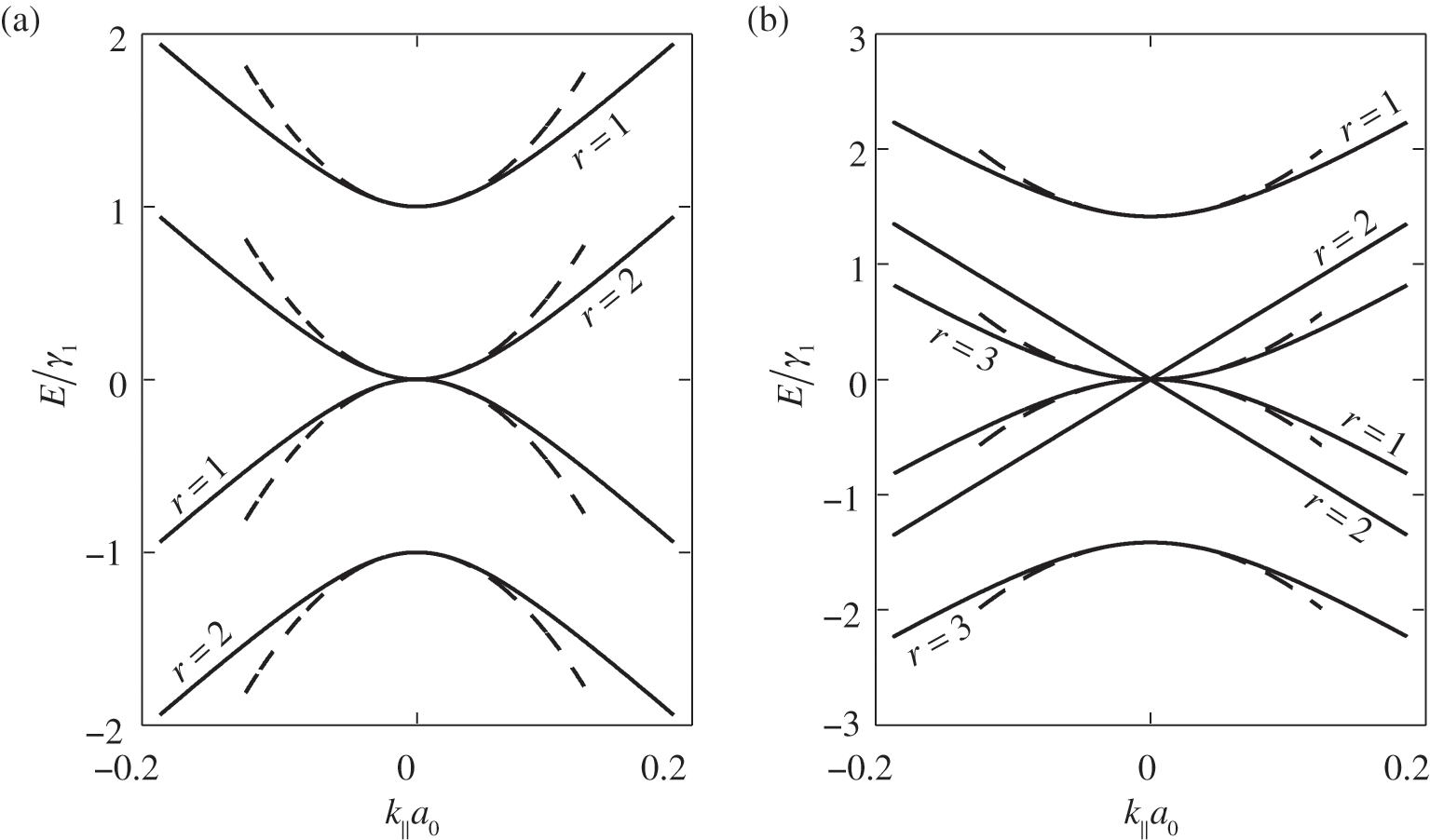

values are positive and the other half are negative, there are N conduction bands and N valence bands. As an example, the band structure of AB-stacked bilayer graphene (![]() ) is shown in Figure 1.8(a), where the solid curves are obtained from (1.58) without approximation and the dashed curves are obtained from (1.59) and (1.60) under the small-

) is shown in Figure 1.8(a), where the solid curves are obtained from (1.58) without approximation and the dashed curves are obtained from (1.59) and (1.60) under the small-![]() approximation, using

approximation, using ![]() and

and ![]() obtained from experiments [Reference Abergel, Apalkov, Berashevich, Ziegler and Chakraborty4]. As can be seen, there are two bands for each value of r (marked next to the curves), and there are a total of

obtained from experiments [Reference Abergel, Apalkov, Berashevich, Ziegler and Chakraborty4]. As can be seen, there are two bands for each value of r (marked next to the curves), and there are a total of ![]() bands for the bilayer system, all of which are massive bands. The effective mass in the small-

bands for the bilayer system, all of which are massive bands. The effective mass in the small-![]() limit is

limit is ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the rest mass of a free electron. The eigenvectors can be obtained accordingly from (1.54) for

is the rest mass of a free electron. The eigenvectors can be obtained accordingly from (1.54) for ![]() and

and ![]() , which in turn give

, which in turn give ![]() and

and ![]() from (1.48):

from (1.48):  , where the eigenenergy E is given in (1.58).

, where the eigenenergy E is given in (1.58).

For odd N, we can always find a value of r such that ![]() given by (1.57), for which (1.58) gives the linear bands

given by (1.57), for which (1.58) gives the linear bands ![]() . Therefore, there are

. Therefore, there are ![]() massive conduction and valence bands described by (1.59) and (1.60), and two linear bands defining one massless Dirac cone given by

massive conduction and valence bands described by (1.59) and (1.60), and two linear bands defining one massless Dirac cone given by ![]() . As an example, the band structure of AB-stacked trilayer of

. As an example, the band structure of AB-stacked trilayer of ![]() is shown in Figure 1.8(b), where six bands can be seen; four are massive bands and two are massless linear Dirac bands.

is shown in Figure 1.8(b), where six bands can be seen; four are massive bands and two are massless linear Dirac bands.

From the above discussions, N-layer AB-stacked graphene has ![]() bands. For even N, all

bands. For even N, all ![]() bands are massive bands. For odd N, there are

bands are massive bands. For odd N, there are ![]() massive bands plus two massless linear Dirac bands.

massive bands plus two massless linear Dirac bands.

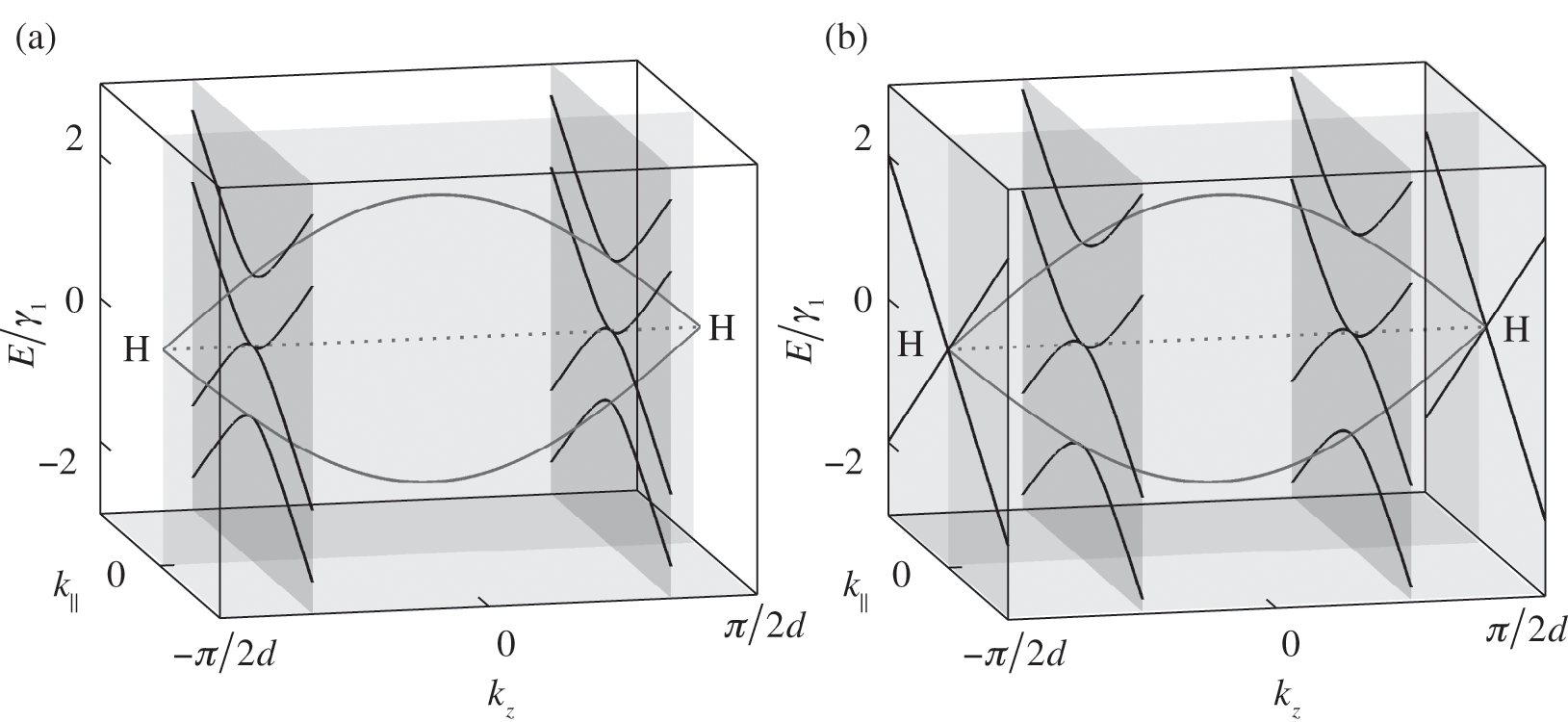

The band structure of natural graphite follows the AB stacking order; it can be obtained from (1.56) and (1.57) by taking the limit that ![]() in (1.54). In this limit,

in (1.54). In this limit, ![]() is no longer discrete but forms a continuous spectrum. In a reduced Brillouin zone scheme,

is no longer discrete but forms a continuous spectrum. In a reduced Brillouin zone scheme, ![]() spans from

spans from ![]() to

to ![]() , where the H point is located, as shown in Figure 1.9 [Reference Slonczewski and Weiss12]. At

, where the H point is located, as shown in Figure 1.9 [Reference Slonczewski and Weiss12]. At ![]() , there are three energy bands: one energy band for

, there are three energy bands: one energy band for ![]() given by (1.50), and two energy bands for

given by (1.50), and two energy bands for ![]() given by (1.57) with

given by (1.57) with ![]() for a conduction band and

for a conduction band and ![]() for a valence band, as shown in Figure 1.9. By using (1.58), one can map out the band structure of graphite as a function of

for a valence band, as shown in Figure 1.9. By using (1.58), one can map out the band structure of graphite as a function of ![]() at different values of

at different values of ![]() . The band structures of bilayer and trilayer graphene are shown in Figure 1.8. For bilayer graphene, two bands at

. The band structures of bilayer and trilayer graphene are shown in Figure 1.8. For bilayer graphene, two bands at ![]() , respectively, in the reduced zone scheme are shown in Figure 1.9(a). For trilayer graphene, the massive bands at

, respectively, in the reduced zone scheme are shown in Figure 1.9(a). For trilayer graphene, the massive bands at ![]() and the massless Dirac bands at

and the massless Dirac bands at ![]() are also plotted, as shown in Figure 1.9(b). Note that the mirrored band structure does not represent double degeneracy because the positive and negative values of

are also plotted, as shown in Figure 1.9(b). Note that the mirrored band structure does not represent double degeneracy because the positive and negative values of ![]() do not represent two independent eigenstates but represent two counter-propagating waves that form the standing wave in multilayer graphene. As can be seen from (1.54) and (1.56), for any solution of

do not represent two independent eigenstates but represent two counter-propagating waves that form the standing wave in multilayer graphene. As can be seen from (1.54) and (1.56), for any solution of ![]() , the values of

, the values of ![]() obtained using the positive and negative values of

obtained using the positive and negative values of ![]() only differ by a negative sign. Therefore, both sets of the coefficients

only differ by a negative sign. Therefore, both sets of the coefficients ![]() obtained from the positive and negative values of

obtained from the positive and negative values of ![]() give the same eigenstate

give the same eigenstate ![]() . The truly independent states are the standing waves of different wave numbers represented by different values of

. The truly independent states are the standing waves of different wave numbers represented by different values of ![]() .

.

Figure 1.9 Band structures of AB-stacked (a) bilayer graphene and (b) trilayer graphene, obtained by cutting the band structure of graphite at certain ![]() values.

values.

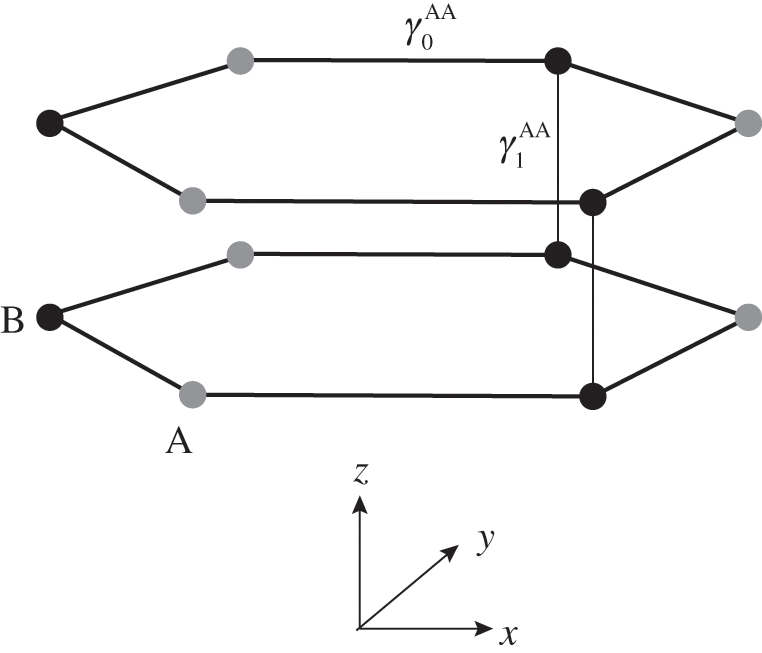

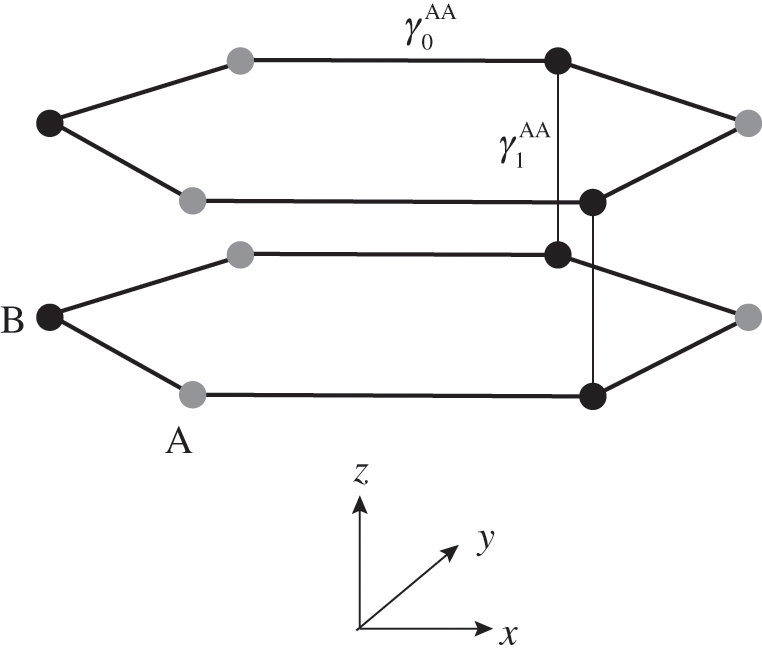

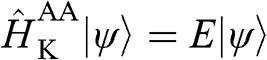

1.6.2 AA Stacking Order

In the AA stacking order, the sublattice A of the upper layer is directly above the sublattice A of the lower layer, and the sublattice B of the upper layer is also directly above the sublattice B of the lower layer, as shown in Figure 1.10. Nearest-neighbor intralayer and interlayer interactions are considered. The intralayer interaction energy ![]() and the interlayer interaction energy

and the interlayer interaction energy ![]() of AA-stacked multilayer graphene are not generally the same as

of AA-stacked multilayer graphene are not generally the same as ![]() and

and ![]() of AB-stacked multilayer graphene.

of AB-stacked multilayer graphene.

Figure 1.10 Atomic structure of AA-stacked bilayer graphene.

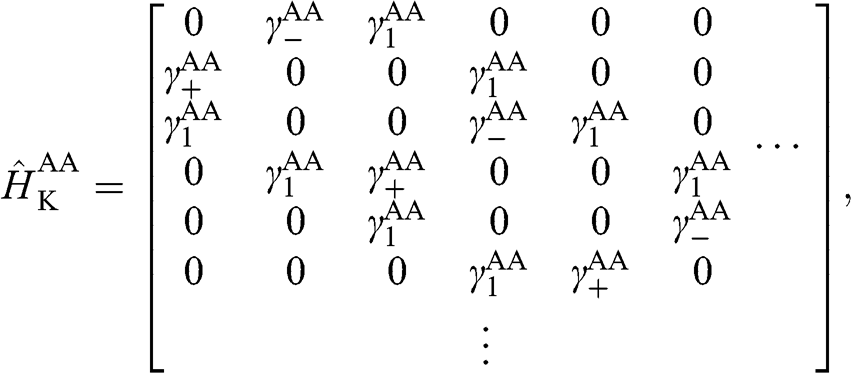

The tight-binding Hamiltonian at the ![]() point for AA-stacked multilayer graphene is constructed as [Reference Min and MacDonald10]

point for AA-stacked multilayer graphene is constructed as [Reference Min and MacDonald10]

(1.61)

(1.61)

where ![]() with

with ![]() . The basis for

. The basis for  is again taken to be

is again taken to be ![]() , with the eigenvector

, with the eigenvector  , both of which have the same form as those for

, both of which have the same form as those for  of (1.47). By applying the eigenvalue equation

of (1.47). By applying the eigenvalue equation  , we find from (1.61) the following difference equations:

, we find from (1.61) the following difference equations:

(1.62)

(1.62)

(1.63)

(1.63)

where ![]() and

and  .

.

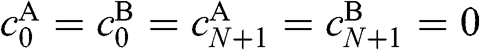

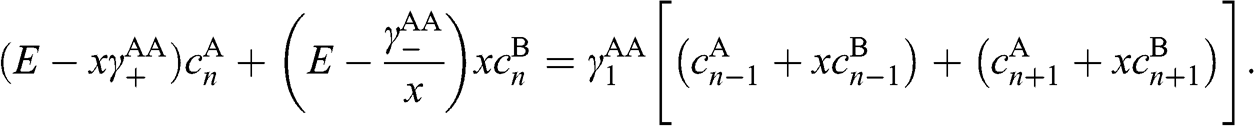

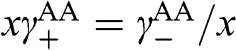

Now we want to transform (1.62) and (1.63) into a form similar to that of (1.53), whose solutions are already known. To do so, we first multiply (1.63) by an unknown variable x that gives us the freedom to adjust the coefficient. We then add (1.62) to (1.63). With some arrangements followed by collecting terms of the same n index, we get

(1.64)

(1.64)

If  , which can be satisfied by taking

, which can be satisfied by taking  , (1.64) can be simplified:

, (1.64) can be simplified:

(1.65)

(1.65)

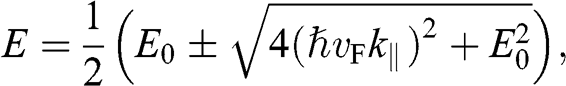

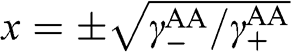

where ![]() . Equation (1.65) has the form of (1.53); therefore, we obtain the eigenenergies:

. Equation (1.65) has the form of (1.53); therefore, we obtain the eigenenergies:

(1.66)

(1.66)

where the identity  is used,

is used, ![]() is given by (1.56) with

is given by (1.56) with ![]() replaced by

replaced by ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the distance between two AA-stacked graphene layers [Reference Lobato and Partoens13,Reference Lee, Lee and Ahn14]. Different from the bands of AB-stacked multilayer graphene, the energy bands of AA-stacked graphene given in (1.66) are all massless linear bands. These linear bands form Dirac cones of shifted energies.

is the distance between two AA-stacked graphene layers [Reference Lobato and Partoens13,Reference Lee, Lee and Ahn14]. Different from the bands of AB-stacked multilayer graphene, the energy bands of AA-stacked graphene given in (1.66) are all massless linear bands. These linear bands form Dirac cones of shifted energies.

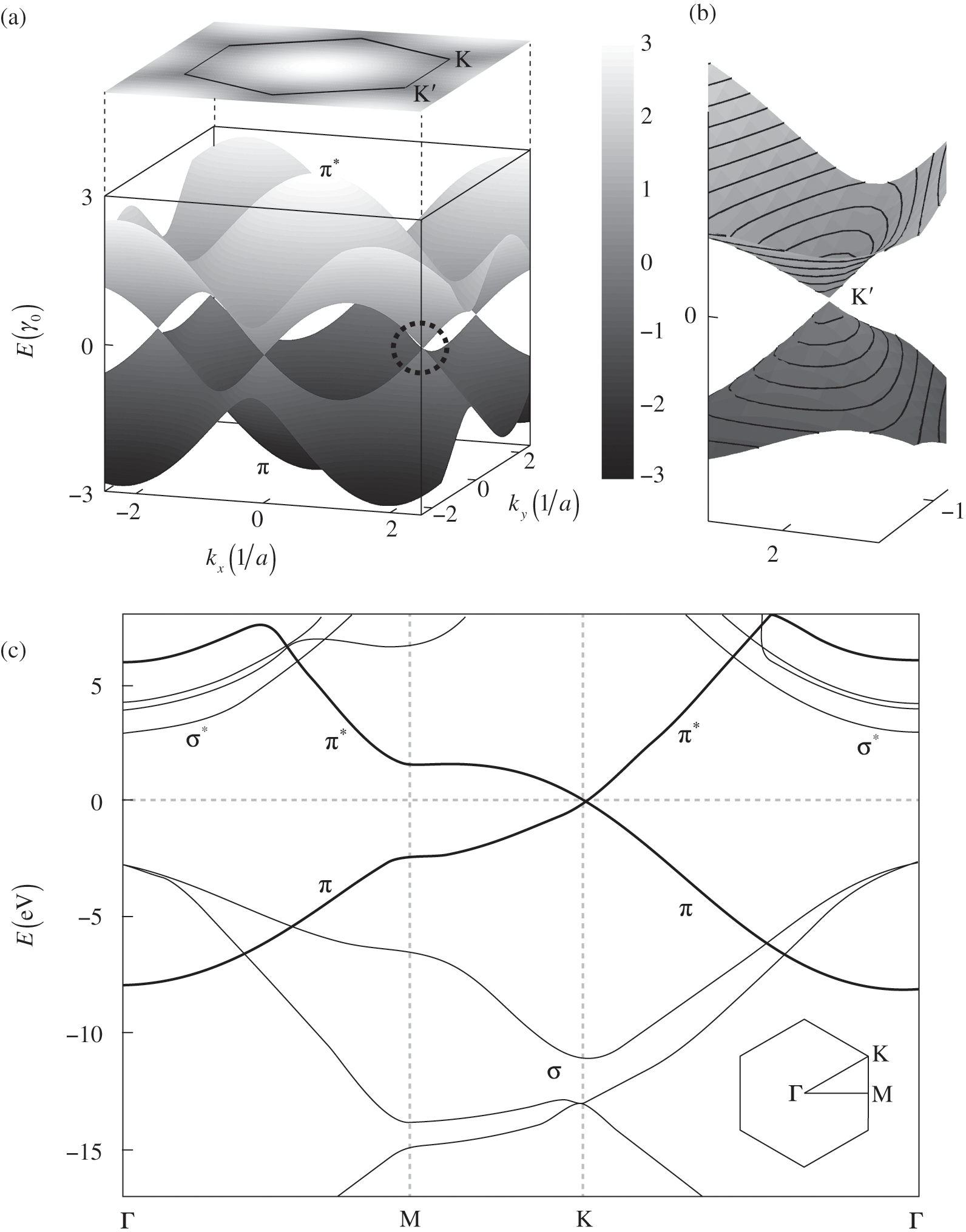

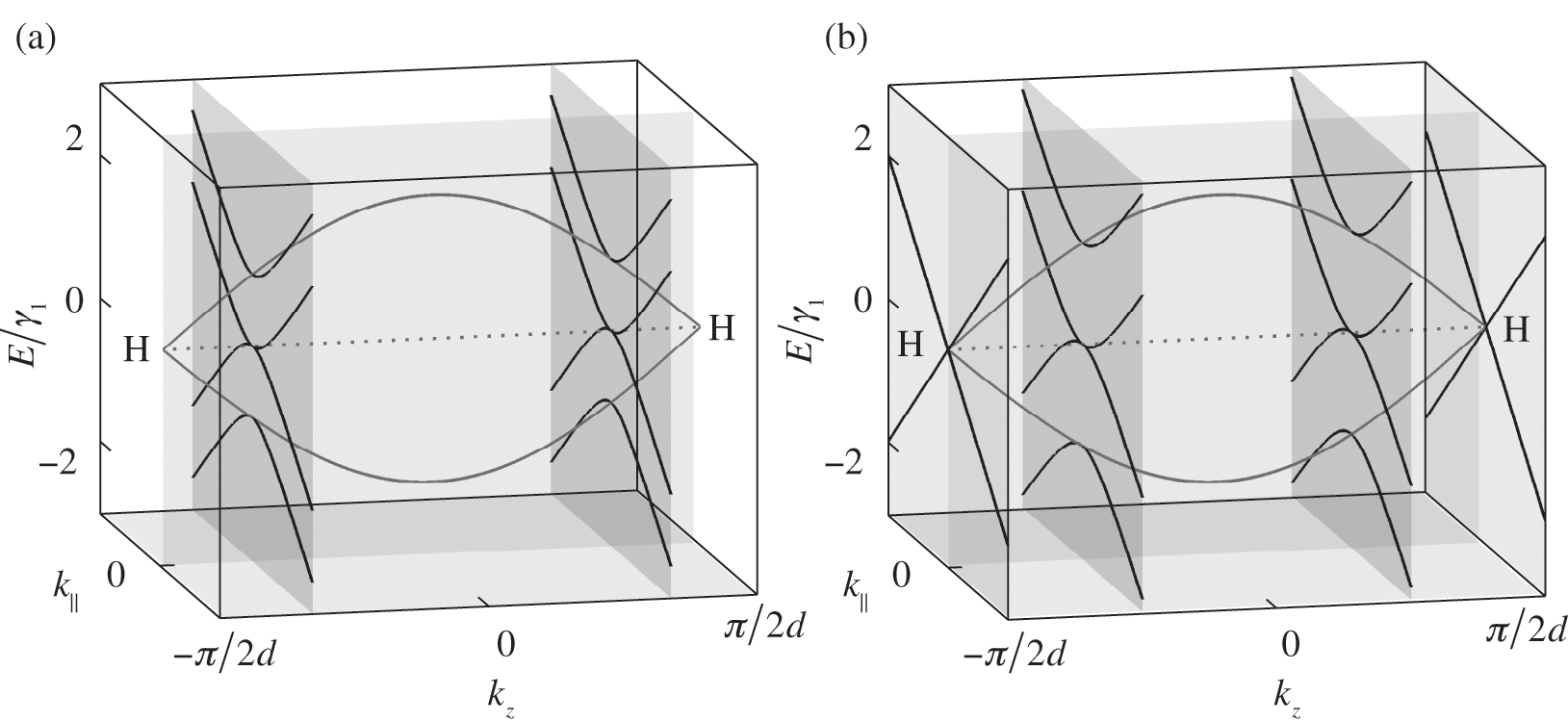

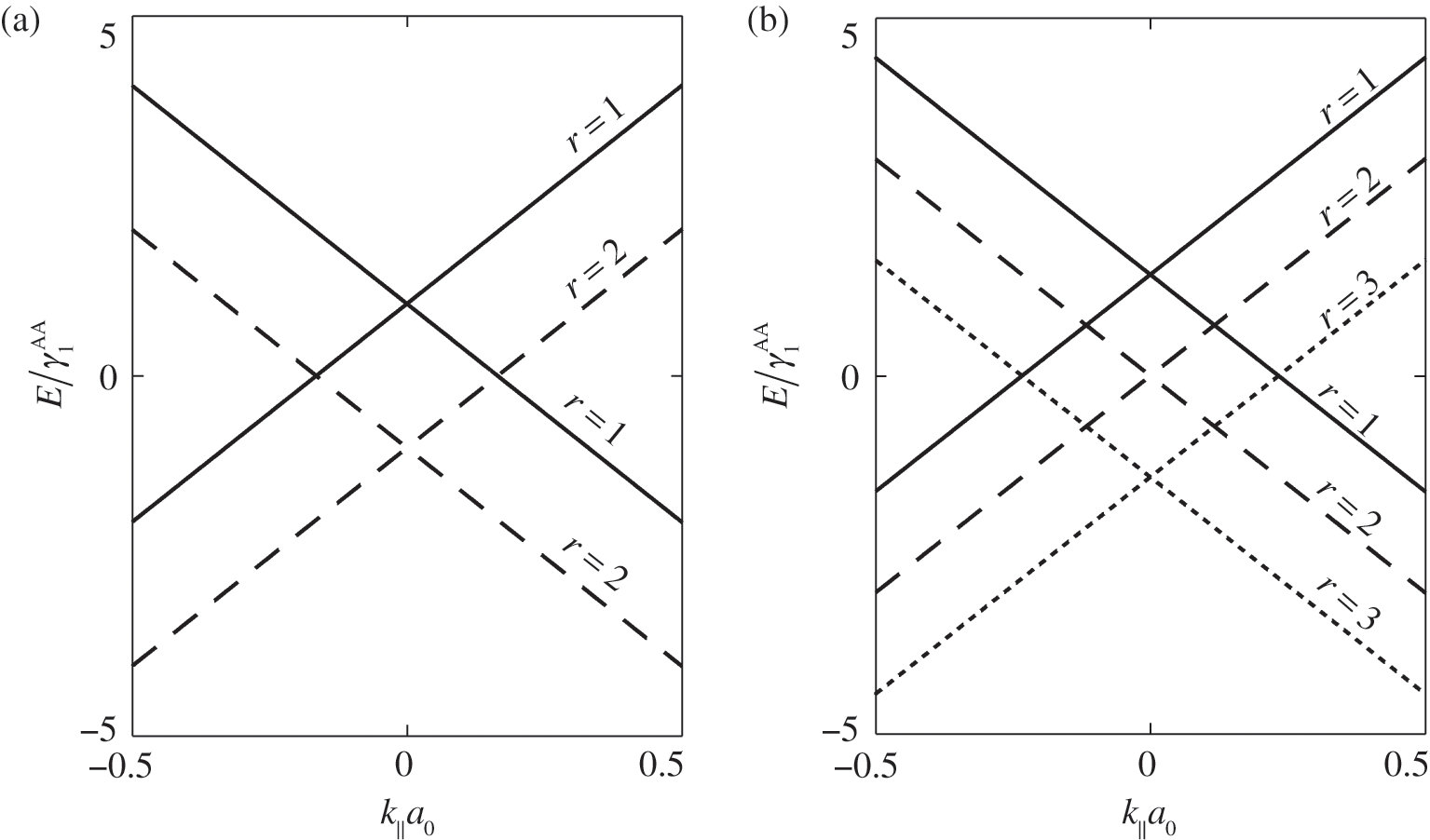

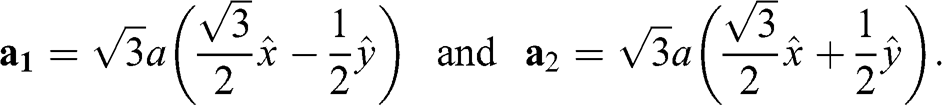

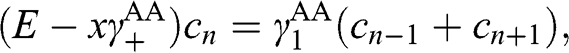

As examples, the band structures of AA-stacked bilayer graphene (![]() ) and trilayer graphene (

) and trilayer graphene (![]() ) are shown in Figures 1.11(a) and (b), respectively, using

) are shown in Figures 1.11(a) and (b), respectively, using ![]() and

and ![]() [Reference Lobato and Partoens13,Reference Lin, Liu and Shi15]. As can be seen, there are two bands for each value of r (marked next to the curves) and a total of

[Reference Lobato and Partoens13,Reference Lin, Liu and Shi15]. As can be seen, there are two bands for each value of r (marked next to the curves) and a total of ![]() bands for the system. The shift of the Dirac point for each band is determined by the second term in (1.66). Note that each Dirac cone of a given r value has its unique

bands for the system. The shift of the Dirac point for each band is determined by the second term in (1.66). Note that each Dirac cone of a given r value has its unique ![]() value. Therefore, unless an out-of-plane momentum is provided, carrier transitions between two different Dirac cones are forbidden.

value. Therefore, unless an out-of-plane momentum is provided, carrier transitions between two different Dirac cones are forbidden.

Figure 1.11 Band structures of AA-stacked (a) bilayer graphene and (b) trilayer graphene.

1.6.3 Misorientation and Other Stacking Orders

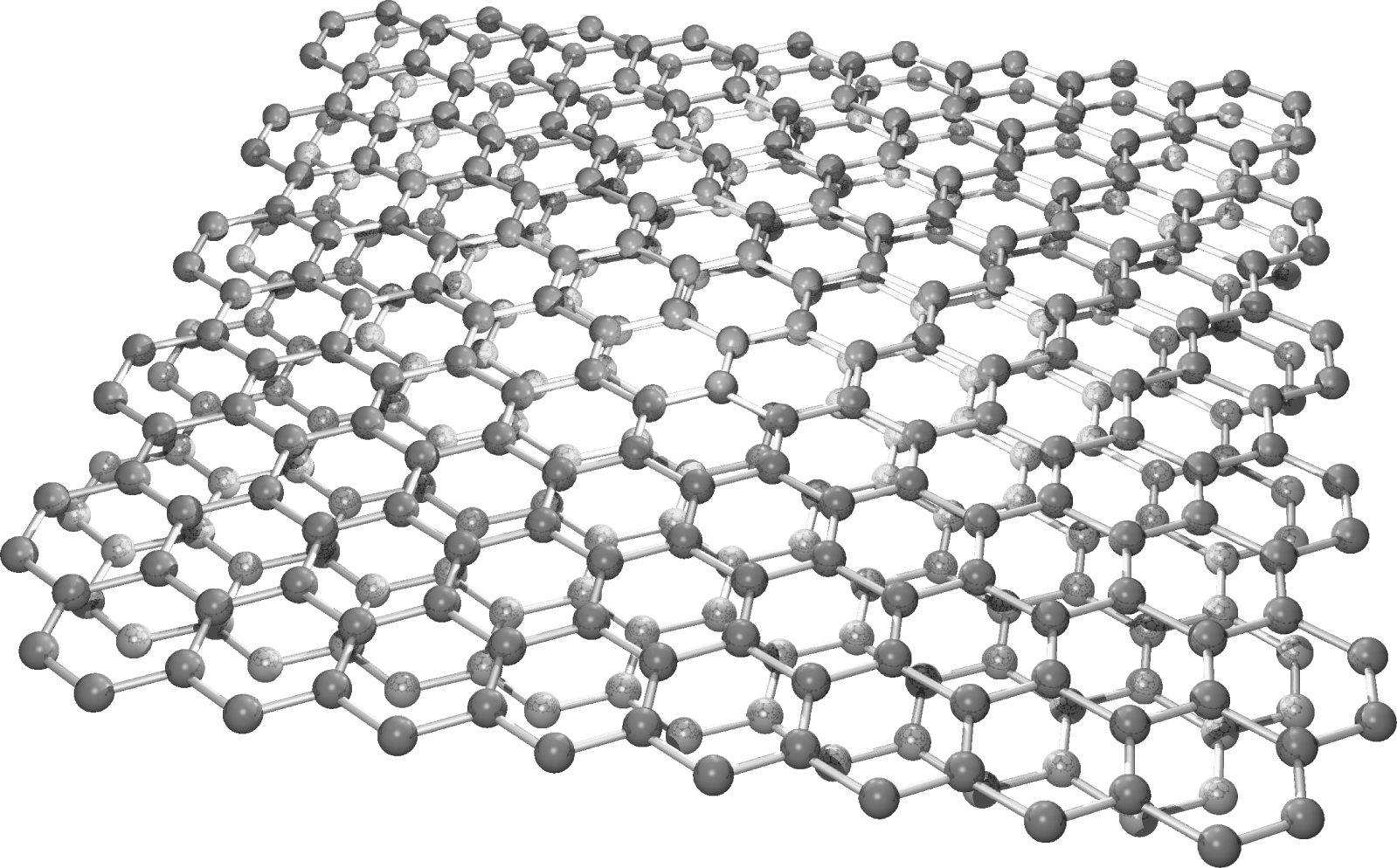

For chemically deposited multilayer graphene, misorientation might happen among graphene layers [Reference Lin, Liu and Shi15,Reference Mele16]. When the relative rotation is small, large areas of locally AA-stacked and AB-stacked regions are formed, as shown in Figure 1.12 for misoriented bilayer graphene. In such a case, each of these regions can be locally treated as AA or AB stacking if the mean free path of the carriers is much smaller than the physical size of the region. Otherwise, one must identify the unit cell of the misoriented multilayer system and numerically calculate the band structure. It is found that while the energy band is still linear around the K point, the Fermi velocity is greatly reduced and therefore localization of electrons is possible in misoriented multilayer graphene [Reference Trambly de Laissardière, Mayou and Magaud17].

Figure 1.12 Misoriented bilayer graphene with locally AA-stacked and AB-stacked regions.

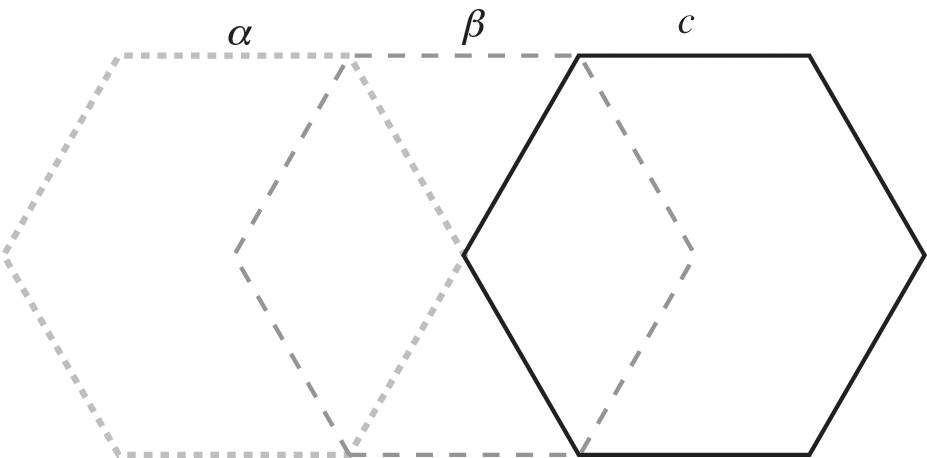

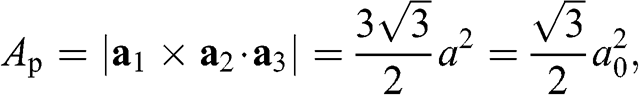

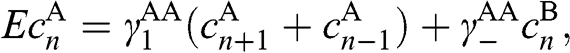

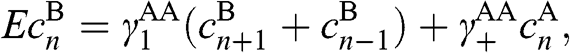

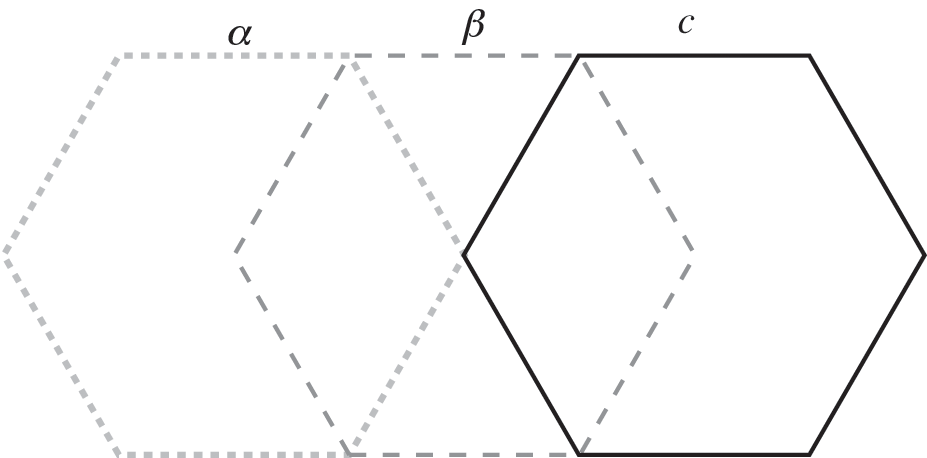

When the number of layers increases, the number of different possible stacking arrangements also increases. For example, in ABC-stacked multilayer graphene, there is a continuous, constant shift from one layer to the next, as shown in Figure 1.13.

Figure 1.13 ABC stacking of multilayer graphene formed by three distinct relative positions of graphene layers, labeled α, β, and c, each successively displaced by one carbon‒carbon distance.

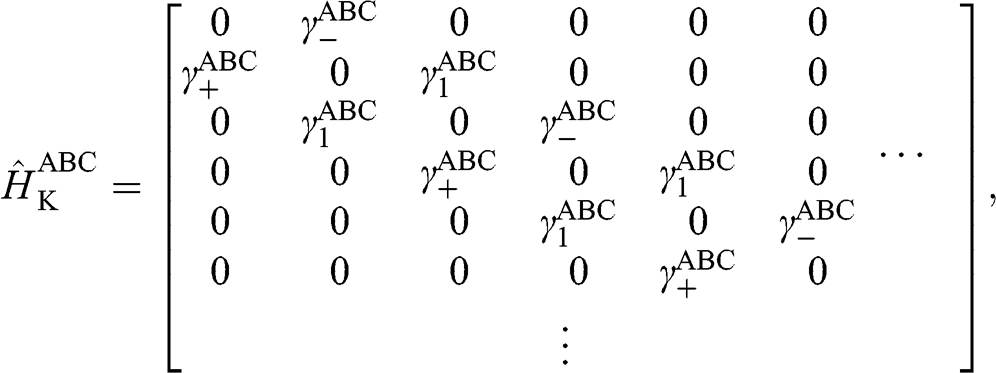

The Hamiltonian of ABC-stacked graphene is given as

(1.67)

(1.67)

where ![]() with

with ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the interlayer interaction energy. Again,

is the interlayer interaction energy. Again, ![]() is not generally equal to

is not generally equal to ![]() or

or ![]() , and

, and ![]() is not generally equal to

is not generally equal to ![]() or

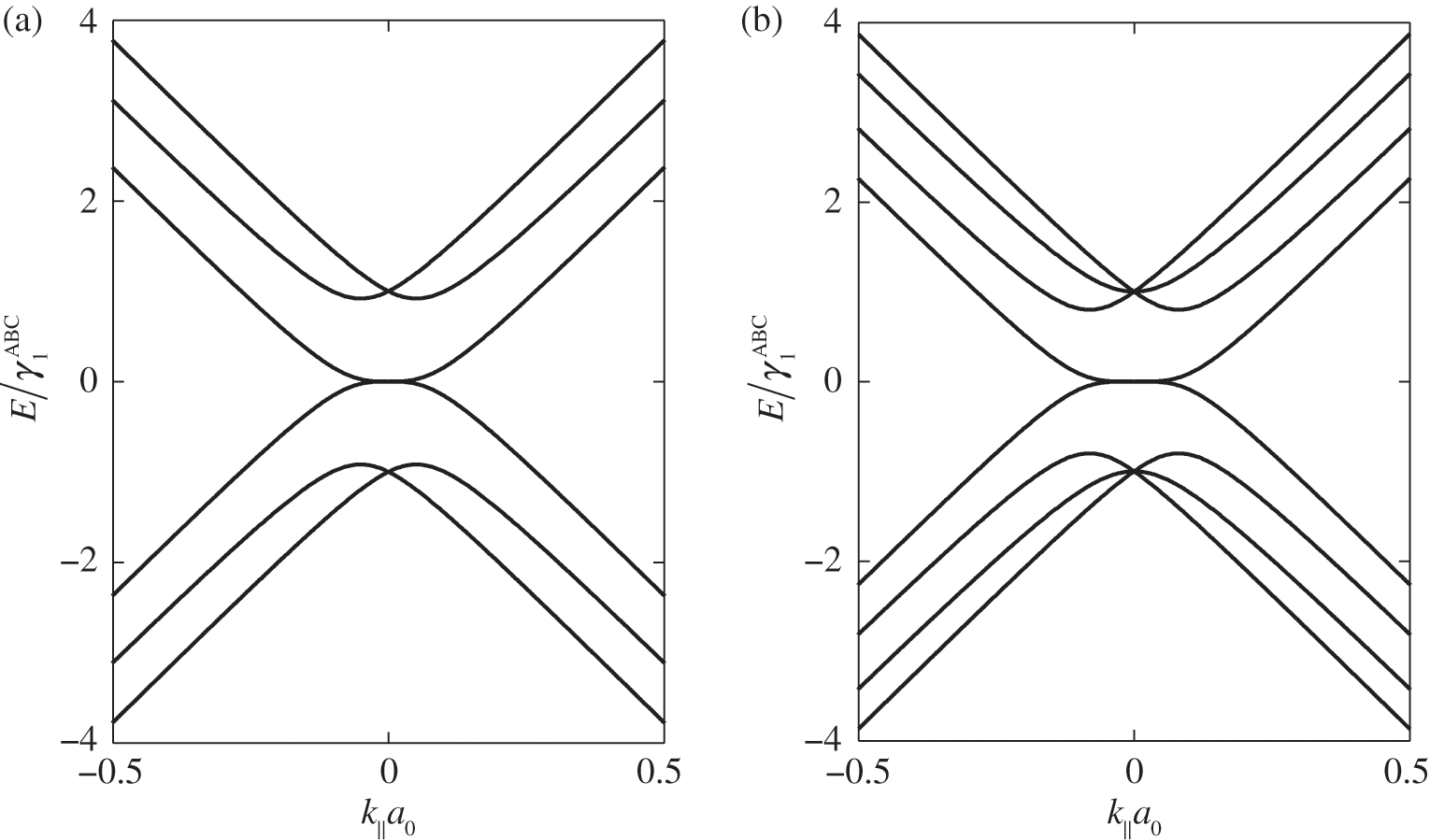

or ![]() [Reference Zhang, Sahu, Min and MacDonald18]. Simple as it might seem for the Hamiltonian shown in (1.67), there do not exist simple difference equations as those obtained for AB- and AA-stacked multilayer graphene [Reference Min and MacDonald10]. Instead, the eigenenergies of (1.67) are numerically obtained for the ABC trilayer and four-layer graphene, as shown in Figure 1.14. As can be seen, regardless of the number of layers, there are always two bands that touch at the K point. The other energy bands are shifted in energy and momentum in different manners but overlap at

[Reference Zhang, Sahu, Min and MacDonald18]. Simple as it might seem for the Hamiltonian shown in (1.67), there do not exist simple difference equations as those obtained for AB- and AA-stacked multilayer graphene [Reference Min and MacDonald10]. Instead, the eigenenergies of (1.67) are numerically obtained for the ABC trilayer and four-layer graphene, as shown in Figure 1.14. As can be seen, regardless of the number of layers, there are always two bands that touch at the K point. The other energy bands are shifted in energy and momentum in different manners but overlap at ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Figure 1.14 Band structures of ABC-stacked (a) trilayer graphene and (b) four-layer graphene.