Introduction

Although Austria's democratic institutions are stable (e.g., Freedom House 2025), citizen satisfaction with how democracy functions remains persistently low. According to the Eurobarometer survey from autumn 2024, only 60 per cent of Austrians reported being at least somewhat satisfied with the way democracy works in their country.Footnote 1 This marked a further decline, compared to the spring wave (−3 percentage points), even though satisfaction remains slightly above the equally declining EU average of 55 per cent (European Commission 2024).

This low level of citizen satisfaction with democracy is remarkable since it has persisted for three years. Historically, satisfaction levels have fluctuated between 60 and 80 per cent since the start of Eurobarometer measurements in Austria, but the continuous decline since 2022 represents an unprecedented development. Furthermore, while elections often boost public sentiment by enhancing feelings of political participation (e.g., Banducci & Karp Reference Banducci and Karp2003, Blais & Gélineau Reference Blais and Gélineau2007), this effect failed to materialize in the latest national vote. Consequently, satisfaction now approaches the historic low seen in 2015, when only 57 per cent of respondents expressed satisfaction in the aftermath of the refugee crisis.

The seemingly paradoxical situation—where expert evaluations consistently rate the quality of Austrian democracy highly, yet citizens express clear dissatisfaction—can likely be explained by the use of different evaluative criteria. Expert-based international indices tend to focus on input factors, such as stable political institutions and the separation of powers. Citizens, by contrast, are more inclined to assess democracy through output-related factors, most notably their personal economic circumstances (Reference Konrath, Praprotnik, Barlai, Griessler, Herbers, Hainzl, Bos and FilzmaierKonrath & Praprotnik, forthcoming). Austria's economic situation has deteriorated, with the country experiencing a second consecutive year of recession and a rising unemployment rate. High prices remained a central issue in Austrian national politics, driven in part by ongoing international instability. At the same time, migration and asylum gained prominence, while climate and environmental concerns declined in salience among voters (ISA/Foresight 2024a, 2024b).

In this political context, the European Parliament elections were held in June, followed by the national parliamentary election in September and two state elections in Vorarlberg and Styria in October and November, respectively. The Freedom Party of Austria/Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) benefited significantly in all elections, while the Austrian People's Party/Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) experienced a notable loss in electoral support. As a result, the FPÖ secured more mandates at all political levels and entered both the Vorarlberg and Styrian state governments, with the FPÖ assuming the position of the state governor in Styria. Despite emerging as the leading party in the national elections, the FPÖ was not part of the first round of coalition talks, and the ÖVP started negotiations with the Social Democratic Party of Austria/Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) and NEOS-The New Austria and Liberal Forum/NEOS-Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS). The election results will be discussed in the subsequent section. The remainder of this report will present the executive and legislative landscape, the party system, institutional changes, and the most prominent issues in Austrian politics.

Election report

The year 2024 may aptly be described as a super-election year. Austria held elections for the European Parliament, the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat), and the regional parliaments of Vorarlberg and Styria, in that chronological order.

European parliamentary elections

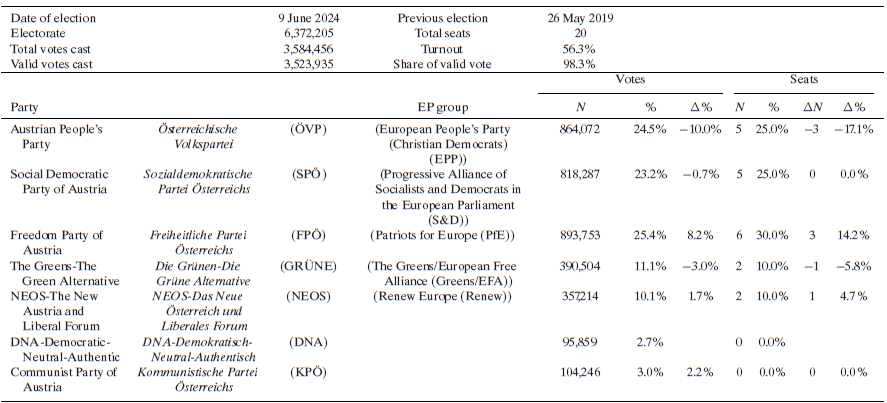

The outcome of the European Parliament election in Austria can only be fully understood through the lens of national political dynamics, as voters often base their EU-level choices on domestic considerations (ISA/Foresight 2024c). Due to the national snap election in 2019, both the EP and national elections were held in the same year (Jenny Reference Jenny2020). While in 2019 the ÖVP led in the polls and at the ballot box, by 2024, the situation had shifted in favor of the FPÖ. The initial rally-round-the-flag effect observed during the COVID-19 crisis, which had benefited the ÖVP–the Greens (GRÜNE) government, had dissipated. Russia's war against Ukraine, combined with a steep rise in prices in Austria, further fueled public dissatisfaction. In the run-up to the EP election, approximately 50 per cent of the electorate viewed developments at the EU level negatively (ISA/Foresight 2024c). Pre-election polls indicated a close race between the three main parties, with the FPÖ projected to finish first (e.g., Der Standard 2024a). These projections materialized on Election Day (Table 1).

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Austria in 2024

Notes:

1. The following parties used different party labels on the ballot paper: FPÖ: Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ)–Die Freiheitlichen, NEOS: NEOS-Das neue Europa. KPÖ: Kommunistische Partei Österreichs–KPÖ Plus.

2. The total number of seats allocated to Austria increased by two, compared to the 2019 election: One seat was added following Brexit, and another was allocated after the 2024 election. The change in seats (∆N and ∆%) is calculated using the immediate pre-election distribution in 2024 as the baseline.

3. DNA-Democratic-Neutral-Authentic campaigned for the first time.

Source: Bundesministerium für Inneres (2024a).

The FPÖ narrowly secured first place with 25.4 per cent of the vote, followed by the ÖVP with 24.5 per cent. The SPÖ came third, achieving 23.2 per cent. The GRÜNE received approximately 10 per cent of the vote, losing around three percentage points. The Green election campaign was disrupted by allegations against their lead candidate, Lena Schilling, including accusations of dishonesty—primarily related to her private life—and speculation that she might consider switching to The Left group in the European Parliament after the election. Given these allegations (and the party's clumsy handling of them), as well as the low popularity of the ÖVP-Green government at the national level, the electoral losses can still be considered manageable. Both extraparliamentary parties—DNA–Democratic–Neutral–Authentic/DNA–Demokratisch–Neutral–Authentisch (DNA) and the Communist Party of Austria/Kommunistische Partei Österreichs—failed to win a seat in the European Parliament.

Parliamentary election

As in the case of the European Parliament election, the National Council election was held amid widespread dissatisfaction and political unease. A clear majority of the population viewed the country's development over the past five years negatively, with nearly 60 per cent of respondents expressing this sentiment. This is almost double the proportion recorded ahead of the 2019 election. Only one in ten citizens reported a positive perception of national progress (ISA/Foresight 2024d). Evaluations of the ÖVP-GRÜNE federal government's performance reflected this general discontent.

Alongside asylum and migration, which were already a contentious issue before the European elections, the most intensely debated topics were rising prices and the state of the healthcare system. The severe flooding that affected Vienna and Lower Austria just two weeks before the election did not emerge as a dominant electoral issue (ISA/Foresight 2024d). One possible explanation is that, unlike the German floods in 2002, which led to a notable increase in the ruling party's vote share (Bechtel & Hainmueller Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011), the Austrian flood occurred too close to the election. There was not enough time to deliver financial assistance to affected citizens, so public opinion was less likely to be influenced.

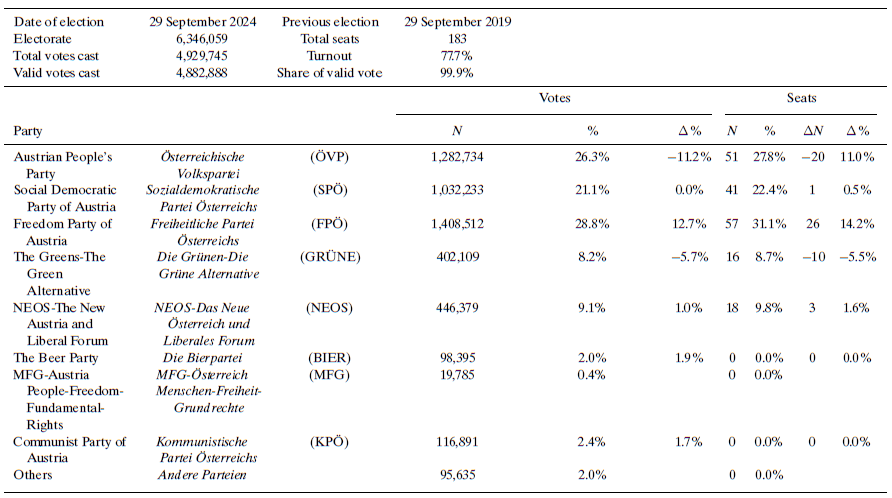

For the first time, the FPÖ emerged as the leading party in a national election, securing 29 per cent of the vote—an increase of nearly 13 percentage points (see Table 2). In contrast, the ÖVP suffered significant losses, dropping over 11 points to 26 per cent. The SPÖ garnered 21 per cent of the vote, maintaining a result roughly in line with its 2019 performance. The GRÜNE experienced a notable decline, losing almost 6 percentage points and falling to 8 per cent, while the NEOS registered a modest gain of 1 percentage point, reaching 9 per cent.

Table 2. Elections to the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2024

Notes:

1. MFG-Austria People-Freedom-Fundamental-Rights campaigned for the first time.

2. Others: Die Gelben (BGE), Liste Madeleine Petrovic (LMP), Liste GAZA–Stimmen gegen den Völkermord (GAZA), Keine von denen (KEINE).

Source: Bundesministerium für Inneres (2024b).

The FPÖ placing first in a general election for the first time prompted President Alexander Van der Bellen, former leader of the GRÜNE, to break with a previously stable tradition. Although not regulated by the constitution, it has been customary for the President to grant the mandate to form a government to the top candidate of the strongest party. Van der Bellen, however, chose to invite the leading figures of all parties to individual discussions. Subsequently, he issued a statement announcing that he would grant the mandate to form a government to the ÖVP, as both the ÖVP and the SPÖ had reiterated their refusal to form a coalition with the FPÖ under Herbert Kickl. Following this decision, the ÖVP initiated coalition negotiations with the SPÖ and the NEOS. These negotiations turned out to be challenging due to stark differences—between the ÖVP and the SPÖ on economic policy and between the ÖVP and the NEOS on societal issues. While it initially appeared that the parties might reach an agreement by the end of 2024, the NEOS withdrew from the negotiations a few days into the new year, followed shortly thereafter by the SPÖ. Although the parties offered differing explanations for the breakdown of talks, the deteriorating economic situation likely played a crucial role.

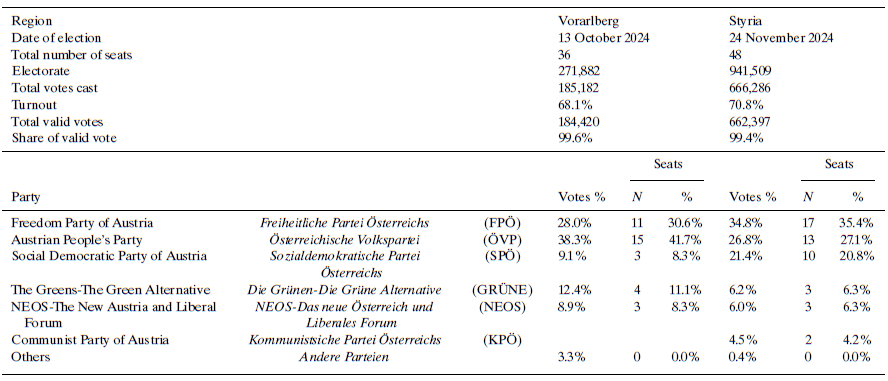

Regional elections

Regional parliaments were elected in Vorarlberg and Styria (see Table 3). At the time of the elections, Vorarlberg was governed by an ÖVP-GRÜNE coalition and Styria by an ÖVP-SPÖ coalition. The FPÖ, which campaigned as opposition, achieved remarkable victories, securing 28 per cent (+14 percentage points) in Vorarlberg and 35 per cent (+17 percentage points) in Styria. At the same time, the ÖVP suffered significant losses, obtaining 38 per cent (−5 percentage points) in Vorarlberg and 27 per cent (−9 percentage points) in Styria. Voter flow analyses confirm that a large share of former ÖVP voters shifted to the FPÖ (ISA/Foresight 2024a, 2024b)—reinforcing the well-established pattern of party competition at the national level, in which gains for one typically come at the expense of the other.Footnote 2 Furthermore, the GRÜNE lost support in both regions, despite being in government in one and opposition in the other. This shift reflects a changing public agenda, where asylum and immigration gained prominence over, though did not displace, climate concerns (ISA/Foresight 2024a, 2024b). Following the elections, the leading party in each state formed a coalition with the second-strongest party, resulting in the previously seen ÖVP–FPÖ coalition in Vorarlberg and a completely new FPÖ–ÖVP coalition in Styria, where the FPÖ was, for the first time, able to appoint the state Governor.

Table 3. Results of regional (Vorarlberg, Styria) elections in Austria in 2024

Notes:

1. Different party labels used on the ballot paper in Vorarlberg: ÖVP: Landeshauptmann Markus Wallner–Vorarlberger Volkspartei, GRÜNE: Die Grünen–Grüne Alternative Vorarlberg, FPÖ: Liste Christof Bitschi–Vorarlberger Freiheitliche, SPÖ: Mario Leiter–SPÖ Vorarlberg. NEOS: NEOS–Das Neue Vorarlberg.

2. Different party labels used on the ballot paper in Styria: ÖVP: Steirische Volkspartei Christopher Drexler, SPÖ: Steirische Sozialdemokratie –Anton Lang, NEOS: NEOS- Die Reformkraft für deine neue Steiermark.

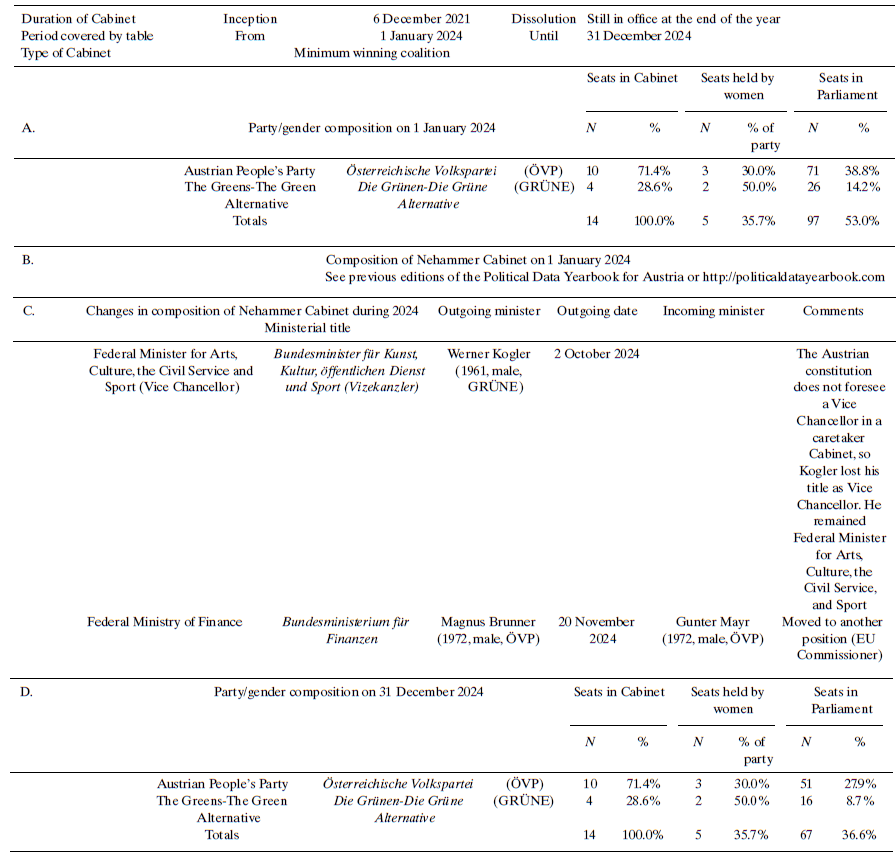

Cabinet report

There were only minimal changes in the personnel composition of the Nehammer Cabinet (see Table 4). In May, Florian Tursky (ÖVP) resigned as Junior Minister for Digitalisation and Telecommunications, having been selected as the top candidate for the local election in Innsbruck, the capital of the federal state of Tyrol. His portfolio was assumed by Claudia Plakolm (ÖVP), Junior Minister for Youth and Civil Service as the nationwide vote was only a few months away. Following the election, as is customary, the Cabinet submitted its resignation to the President, who in turn requested that it remain in office until a new government could be formed. The Cabinet continued as a caretaker government. As the Austrian constitution does not formally recognize the position of Vice-Chancellor, Werner Kogler (GRÜNE) no longer held the title and continued in his role as Federal Minister for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service, and Sport. Furthermore, Junior Minister for Arts and Culture, Andrea Mayer (GRÜNE), did not remain in office after the election, and her position remained vacant. In November, Magnus Brunner stepped down as Federal Minister of Finance following his appointment as EU Commissioner for Migration. He was succeeded by Gunter Mayr (both ÖVP). The ÖVP-GRÜNE caretaker government was still in office by the end of 2024 due to the ongoing coalition negotiations.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Nehammer in Austria in 2024

Notes:

1. National elections were held on 29 September 2024. After the election, the Nehammer Cabinet lost its majority in Parliament. It remained in office as a caretaker government until the new Stocker Cabinet was sworn in on 3 March 2025.

2. There were some changes among the junior ministers as well. On 1 May 2024, Florian Tursky (ÖVP) resigned as Junior Minister for Digitalisation and Telecommunications. Junior Minister for Youth and Civil service, Claudia Plakolm (ÖVP), took over his responsibilities. Junior Minister for Art and Culture, Andrea Mayer (GRÜNE), did not remain in office during the caretaker government that began on 2 October 2024.

Source: Parlament Österreich (2025a).

Parliament report

In 2024, the National Council convened 34 plenary sessions and held 152 committee meetings. A total of 140 legislative decisions were made. There was one objection from the second, considerably weaker chamber—the Federal Council—and in one instance, the Council did not issue a decision, thereby delaying the legislative process (Parlamentsdirektion 2024).

National elections were held on 24 September 2024 (see section Parliamentary Election), and the constitutional session of the newly elected National Council took place on 24 October 2024. Following the FPÖ’s historic victory—securing first place for the first time—an intense debate emerged over whether Parliament should adhere to the convention of electing a member of the strongest party as President of the National Council. In the secret ballot, the FPÖ candidate secured a majority, although especially the GRÜNE had expressed strong opposition to his election.

Two committees of inquiry were conducted during the year. The COVID-19 Financing Agency (COFAG) Committee of Inquiry (15 December 2023–3 July 2024), jointly initiated by the SPÖ and the FPÖ, examined the allocation practices of the COFAG, focusing in particular on potential preferential treatment of wealthy individuals with ties to the ÖVP through political donations. The inquiry covered the period from late 2017 to the end of 2023 (Parlamentskorrespondenz 2024a). The Red-Blue Power Abuse Committee of Inquiry (15 December 2023–3 July 2024), initiated by the ÖVP, investigated the SPÖ–FPÖ coalition governments from 2007 to early 2020, focusing on whether public funds had been lawfully used in ministries controlled by these parties (Parlamentskorrespondenz 2024b). While the specific allegations could not be conclusively confirmed, the final reports by the procedural judge reiterated criticisms of COFAG itself and recommended reforms to the Federal Archives Act and the Federal Procurement Act. In the end, the parties appeared to (also) strategically use their minority powers to initiate committees of inquiry. The naming of the committee and references to the committee work, as well as the fact that the ÖVP quickly submitted a request for a further inquiry after it became evident that the SPÖ and FPÖ would initiate one targeting the ÖVP, suggest a connection to both the European Parliament and national elections held that year.

The Austrian Parliament implemented a range of measures to combat antisemitism and raise awareness of its dangers. For example, it took part in the international #WeRemember campaign of the World Jewish Congress and illuminated the Parliament building for five days. An exhibition on the danger antisemitism poses to democracy was expanded to include a module on Jewish life. A new workshop on antisemitism targeting ninth-grade students was introduced as part of the Parliament's civic education program for young people. The Austrian Parliament hosted the first international conference on antisemitism with the aim of establishing a transnational parliamentary alliance, concluding with a declaration calling for intensified efforts to combat antisemitism and explicitly support Jewish life in Europe (Parlamentsdirektion 2024: 82–89).

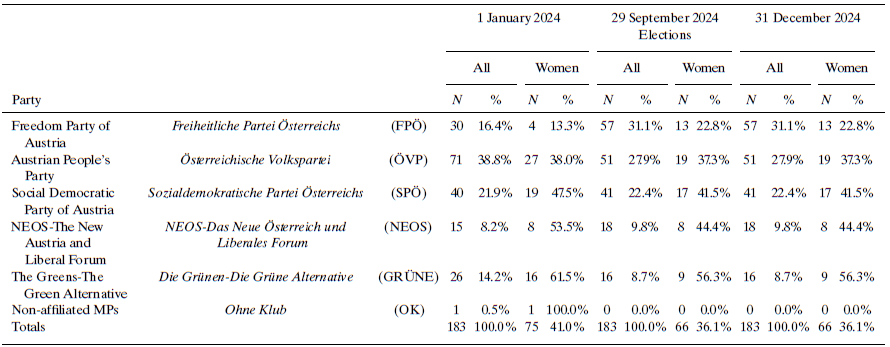

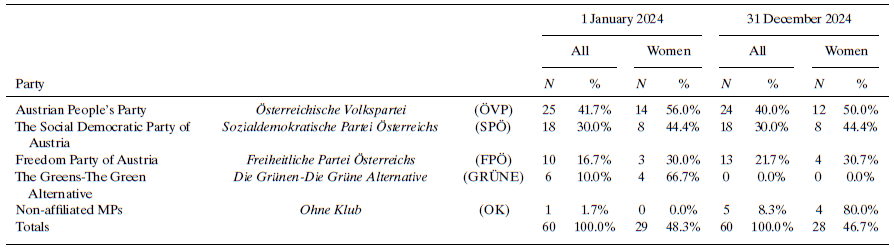

Tables 5 and 6 provide an overview of the Austrian Parliament's composition in 2023.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2024

Source: Parlament Österreich (2025b).

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Bundesrat) in Austria in 2024

Note: Following the partial renewal of the Federal Council after the Styrian state election in December 2024, the GRÜNE now hold only four seats and have therefore lost their parliamentary group status. Together with one NEOS member, they are classified as non-affiliated as of 31 December 2024.

Source: Parlament Österreich (2025c).

Political party report

There were no major changes within the key parties of the Austrian party system. The internal power struggle within the SPÖ had been resolved by the end of the previous year, with Andreas Babler becoming party leader (Praprotnik Reference Praprotnik2024). While Hans-Peter Doskozil, the defeated leadership candidate and then state Governor of Burgenland, continued to voice criticism, his remarks had no considerable impact on the stability of the party leadership. All relevant parties focused on the elections, particularly the general election, and party leadership remained stable even after the vote.Footnote 3 No party splits occurred nor did any new parties enter Parliament.

Institutional change report

Having reached an agreement by the end of the previous year, the government parties ÖVP and GRÜNE, together with the SPÖ, voted on the Freedom of Information Act in January 2024. This vote marked the abolition of official secrecy, which had been enshrined in Article 20 of the Federal Constitutional Law since 1925, leaving Austria as the last European state to retain such a policy (Parlamentskorrespondenz 2024b). No agreement could be reached in response to the verdict of the Austrian Constitutional Court, as government influence over the public broadcaster ORF—particularly in the nomination of members to its supervisory bodies—remains too strong.

Issues in national politics

Due to the intense electoral calendar, public discourse was dominated by the election campaigns. The final section begins by identifying issues that were present across all elections, before turning to those that were particularly prominent in the run-up to the European Parliament election in June and the national election in September. It then addresses the most severe ÖVP-GRÜNE government crisis of the year, centered on climate protection, and concludes by examining the impact of this dispute on the coalition talks at the end of 2024.

Election surveys indicate that immigration was among the most pressing issues across all electoral levels (ISA/Foresight 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d). At the same time, environmental and climate issues declined in priority or were at least overshadowed by other topics. The FPÖ campaigned against what it characterized as overly lenient asylum and migration policies. The ÖVP similarly promoted a tough stance on asylum and migration, aiming to prevent further voter losses to the FPÖ, particularly in light of its coalition with the GRÜNE.

In the run-up to the European Parliament elections, the topics of security and war were also intensely debated among the public. Despite this, parties largely refrained from addressing Austria's position as a neutral state. The only exception was NEOS, which argued in its election program that Austria's neutrality had already effectively changed due to EU membership, and advocated for the establishment of a European army. Nonetheless, the ÖVP–GRÜNE government adopted a new national security strategy in the autumn, replacing the outdated 2013 version. Unlike its predecessor, the updated strategy no longer referred to Russia as a partner but explicitly condemned Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine and identified it as a threat to global security (Republic of Austria 2024).

For the national elections, rising prices and healthcare emerged as additional key concerns. The national elections, in particular, illustrate that one explanation for the FPÖ’s success lies in its ability to present a program that voters struggling with rising costs found trustworthy. The Austrian case exemplifies what Halikiopoulou and Vlandas (Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020) have tested in a comparative study on far-right party success in Europe. They convincingly argue that while cultural concerns over immigration may drive far-right support, in numerical terms, right-wing parties benefit especially from economic concerns linked to immigration.

In government with the ÖVP, and likely anticipating that the GRÜNE would lose their position after the election, Minister Leonore Gewessler (GRÜNE) took the opportunity to vote in favor of the EU Nature Restoration Law in the Council of the European Union, thereby securing the majority needed for its adoption. The ÖVP accused Gewessler of deliberately violating the law and the constitution, primarily arguing that a binding statement from the provincial governments remained in effect (a position the GRÜNE rejected, citing recent statements from two SPÖ-led regional governments as grounds for no longer considering it binding, see e.g., Der Standard 2024b). However, the ÖVP refrained from ending the coalition so close to the election. It justified its decision not to dissolve the coalition by arguing that such a move would plunge the political system into instability just months ahead of the scheduled autumn elections. They warned that ending the coalition would trigger the so-called free play of forces in Parliament, potentially resulting in the passage of costly and uncoordinated legislation. What the party did not publicly acknowledge was that such a scenario would also have meant diminished control for the ÖVP over parliamentary proceedings and increased pressure from the FPÖ, which would have had more room to push through populist proposals and further dominate the political agenda. Although the ÖVP publicly announced legal consequences in response to Gewessler's vote, these ultimately had no practical effect. At the national level, a criminal complaint for abuse of office was filed but dismissed, while at the European level, the threatened action for annulment at the Court of Justice of the European Union was never submitted. While this dispute became the most prominent political controversy of the year, it had no notable effect on parliamentary cooperation and remained largely symbolic in its impact on policymaking. After the election, however, when the ÖVP—like all other parties—refused to work with the FPÖ and was tasked with forming a government, it chose to negotiate with the SPÖ and NEOS, explicitly excluding the GRÜNE as a potential coalition partner. A brief glance ahead at the developments of 2025 indicates that, even after the initial coalition negotiations failed, the GRÜNE was not reconsidered as a potential partner. Instead, the ÖVP entered negotiations with the FPÖ; when these also failed, it returned to the negotiating table and ultimately concluded successful coalition talks with the SPÖ and NEOS, resulting in the formation of an ÖVP–SPÖ–NEOS government.