1. Introduction

While populism has dominated the political landscapes of many old democracies in Europe and the Americas for decades, East Asia’s new democracies have been considered relatively insulated from populist politics (Hellmann, Reference Hellmann, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Stiguy2017; Lind, Reference Lind2018; Hieda et al., Reference Hieda, Zenkyo and Nishikawa2021; Hur, Reference Hur2022; Steel and Kohama, Reference Steel and Kohama2022; Jou, Reference Jou and Mosler2023; Mosler, Reference Mosler and Mosler2023; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Krumbein and Mosler2025). Although a small number of East Asian politicians have been labelled as populists, they rarely fit the ideational definition of populism politicians without any controversies (Hellmann, Reference Hellmann, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Stiguy2017; Mosler, Reference Mosler and Mosler2023; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Krumbein and Mosler2025).

Recent developments in Korean politics, however, suggest a departure from this pattern. The 2022 presidential election campaign was marked by intense debates over populism.Footnote 1 The two major presidential candidates accused each other of being populists while simultaneously employing rhetoric that revealed their own populist tendencies, as this paper will demonstrate. This surge in populism is echoed by recent academic studies showing that populist attitudes, measured using survey items developed for European cases (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016), influence political behaviours and support for certain policies or institutions among Korean voters (Ha, Reference Ha2018; Do, Reference Do2021a, Reference Do2021b; Han and Shim, Reference Han and Shim2021; Jung and Do, Reference Jung and Do2021; Hur, Reference Hur2022; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Oh and Cho2022; Jang and Chang, Reference Jang and Chang2022; Park, Reference Park2022; Song and Kim, Reference Song and Kim2023).

Despite the emerging prominence of populism in Korean politics, existing literature has insufficiently analysed how populism gained traction in a political context previously considered resistant to it. Moreover, the impact of populist mobilisation on vote choice in the 2022 presidential election has yet to be fully explored. To address these gaps, this paper investigates the rise of populism in Korean elections by examining three key questions: Under what conditions was populist rhetoric effectively mobilised suddenly around 2022? To what extent did the two major candidates employ populist messages? And how did citizens with stronger populist attitudes align themselves with specific candidates?

Our central argument is that even in a political context where strong populism has not historically been prominent, populism can influence elections under certain conditions. First, an economic crisis at the national level or economic difficulties at the individual level can foster dissatisfaction with the political status quo. Then, a politician may leverage populist rhetoric, blaming unresponsive and self-serving political elites for these economic hardships. This blame is typically framed as collusion among corrupt elites rather than a mere policy failure, thereby deepening public doubt about democratic governance by traditional elites. Finally, this rhetoric resonates with voters who already have populist leanings, and they, in turn, support the populist politician at the polls.

To support our argument, we employed mixed-methods research design. First, we analysed all 172 campaign speeches delivered by the two candidates, Yoon Suk-yeol and Lee Jae-myung, evaluating their degree of populism in each speech using Hawkins’ holistic grading method. This allowed us to assess which candidates conveyed a more populist message during the campaign. Second, we conducted quantitative analysis examining the association between populist attitudes and vote choice, using two online public opinion surveys administered before the campaign and after the election. The empirical results revealed that while there was initially no correlation between populist attitudes and candidate support, Yoon expressed more populist messages than Lee during the campaign, and voters with populist attitudes ultimately showed a higher likelihood of voting for Yoon over Lee.

This study aims to contribute to the literature on populism in new democracies. While the extant research has focused primarily on populism in established democracies, little is known about populism in new democracies where no strong history of populism mobilisation has existed (Hellmann, Reference Hellmann, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Stiguy2017; Mosler, Reference Mosler and Mosler2023; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Krumbein and Mosler2025). Research remains limited on whether populist attitudes affect voting behaviour and under what conditions populism demand emerges in these countries and influences elections.

In the context of Korean politics, this paper offers novel insights into elite mobilisation of populism through campaign speeches. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate populism rhetoric in Korean presidential campaign speeches. While our analysis is limited to official campaign speeches and does not encompass all forms of verbal communications from candidates, we believe that these official campaign speeches, representing highly coordinated and essential messages, offer sufficient insight to assess the mobilisation of populism rhetoric.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 defines populism, summarises its key components, and proposes three conditions for the activation of populist voting, based primarily on literature from Europe and the Americas. Section 3 presents theoretical arguments as to how the three conditions were met during the 2022 Korean presidential election. Section 4 explains our holistic grading method and presents an analysis of the candidates’ presidential campaign speeches, used to measure the extent of their populist mobilisation. Section 5 presents the empirical effects of voters’ populist attitudes on their vote choices, an analysis based on data from two public opinion surveys, one conducted before the election and one after. The conclusion in Section 6 discusses the implications of our findings.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definitions of populism

Existing studies have defined populism in various ways – as an ideology, a style of public discourse, a political strategy, or a social movement. To reduce conceptual ambiguity, we adopt the widely cited ideational definition proposed by Mudde and Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017: 6): ‘a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, the pure people versus the corrupt elite, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people’. This ideational definition of populism incorporates three core components of populism: people-centrism, anti-elitism, and anti-pluralism.

First, people-centrism posits a moral dichotomy between the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’. The people are portrayed as innocent, hard-working, and morally upright, while the corrupt elite are seen as self-serving and disconnected from the pure people. From this perspective, the general will of the pure people is expressed as a unified and morally superior voice, and the pure people are assumed to be a homogenous group.

Second, the romanticised notion of the pure people is accompanied by a strong disdain for an allegedly corrupt elite. Populists perceive the establishment as untrustworthy, using its power to serve its own interests (Barr, Reference Barr2009; Müller, Reference Müller2016). Consequently, for populists, the ultimate goal of politics is to implement and execute the general will of the people without going through any intermediaries, including elites, experts, or representative bodies. For them, the representative democratic system is designed to serve the interests of the corrupt elite and politicians, rather than the pure people (Donovan and Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2006).

This hatred of the elite leads to the third component: a Manichean worldview that sees the world as divided into good and evil, a view that ultimately entails anti-pluralism. In this dichotomous worldview of the pure people versus the corrupt establishment, the elite are portrayed as evil entities to be eradicated. Thus, populists ‘consistently and continuously deny the very legitimacy of their opponents’ (Müller, Reference Müller2015: 86), because those who oppose the morally pure people are regarded merely as enemies of the people. This Manichean worldview is exemplified in Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s well-known rhetorical question: ‘We are the people—who are you?’ Hence, Müller argues that populists are ‘always anti-pluralist’, not merely anti-elitist (Müller, Reference Müller2016: 3).

Based on this conceptualisation, we define populist attitudes as the individual-level endorsement of people-centrism, anti-elitism, and anti-pluralism. This leads to our research question: under which conditions do populist attitudes translate into votes for populist politicians?

2.2. Activation of populist voting

In light of the electoral successes of well-known populists such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, the National Rally in France, and SYRIZA in Greece, recent studies have increasingly examined the association between populist attitudes and voting behaviour in various countries such as Canada (Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2021), Germany (Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Hirsch, Schurmann and Veit2020), Greece (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020), the Netherlands (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014), Portugal (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, Reference Santana-Pereira and Cancela2020), Spain (Marcos-Marne et al., Reference Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and O’Flynn2024), and nine European countries (Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). A general consensus emerging from these studies is that populist attitudes do not always translate into voting for populist candidates or parties. Even when a significant portion of the electorate holds populist views such as people-centrism, anti-elitism, and anti-pluralism, these attitudes do not necessarily lead to electoral success for populists. As Hawkins and his coauthors note, ‘populism as a set of political attitudes must be activated’ to be connected to specific attitudes or behaviours (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Read, Pauwels, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 276).

The existing literature proposes three interrelated conditions that help activate latent populist attitudes and convert them into voting behaviour: (1) economic hardship, (2) political dissatisfaction, and (3) the emergence of a populist figure.

The first condition, economic hardship, is one of the most widely discussed conditions that may bring latent populist attitudes to the fore. Since Betz (Reference Betz1994) argued that the so-called ‘losers of globalization’ tend to support populist parties, numerous studies have examined how globalisation-induced economic hardships have contributed to the rise of radical right populism in Europe (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1994; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Carreras et al., Reference Carreras, Carreras and Bowler2019). Consistent with this idea, support for Donald Trump in the United States and support for Brexit in the United Kingdom largely came from the white working class living in economically declining areas and experiencing insecurity (Carreras et al., Reference Carreras, Carreras and Bowler2019). Though nationwide economic crises may not be directly related to globalisation, these have also led to sudden surges in populist support, as occurred following the 2012 economic crisis in Greece, where both the left-wing populist party SYRIZA and the right-wing populist party ANEL gained popularity.

The second condition is political dissatisfaction with established parties or politicians, particularly when they have failed to address economic difficulties. Voters’ disappointment and anger often create fertile ground for populist appeals. This dissatisfaction may not always be directed solely at the ruling party. When voters feel inadequately represented and view all mainstream parties as unresponsive to their hardships, those with latent populist attitudes may become more receptive to the populist narrative that mainstream politicians serve only the corrupt elite and ignore ordinary, hard-working people like themselves. As such dissatisfaction deepens, disappointment and anger may escalate into broader distrust of the political system and democratic governance itself under the existing elite. In this sense, populism begins as a response to the failure of traditional parties (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014; Roberts, Reference Roberts2015) and ultimately manifests as a symptom of the failure of democratic governance (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Read, Pauwels, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 272).

While the first two conditions foster populist demand, they alone do not guarantee the electoral success of populist actors. The final condition is the emergenceFootnote 2 of a populist figure, such as Chávez or Trump, who can channel public discontent and mobilise support (Weylan, Reference Weyland2001, Reference Weyland, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Barr, Reference Barr2009). Weyland emphasises the importance of populist leaders and their political strategies, defining populism as ‘a political strategy through which a personalistic leader who seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers’ (Weyland, Reference Weyland2001: 14). For him, the emergence and persistence of populist politics depends on whether and to what extent ‘the rhetorically empowered people follow a leader who claims to act on their behalf’ (Weyland, Reference Weyland, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 54). The role of populist actors, their rhetoric, and their strategic choices are thus central to explaining how populist appeals are ultimately converted into electoral victories.

The emergence of a populist figure is most evident through the mobilisation of populist discourse. Research on the supply side of populist politics has examined populist communication strategies across various platforms: public speeches (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020), party manifestos (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2011; Rooudijn and Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2011; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, De Lange and Van Der Brug2014; Munucci and Weber, Reference Munucci and Weber2017; Rooduijn and Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017), and campaign messages (Munucci and Weber, Reference Munucci and Weber2017; Bernhard and Kriesi, Reference Bernhard and Kriesi2019). Despite some variations, these studies consistently show that populist discourse and mobilisation messages follow recognisable patterns. First, to stimulate political dissatisfaction, populist politicians denounce mainstream parties as part of a corrupt, self-serving establishment. Beyond this, they seek to convert economic grievances into broader political discontent by suggesting the existing democratic system has been captured by a corrupt elite. In doing so, populists do not reject democracy as an abstract principle; rather, they implicitly depict representative democracy as corrupt, ineffective, and ultimately failed, while presenting themselves as uniquely able to represent the innocent people (Donovan and Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2006; Müller, Reference Müller2016).

Second, when it comes to the policy dimensions of populist rhetoric, there are important variations. Because populism is ideologically thin-centred, the substantive policy contents of populist messages vary according to the politician’s ideological orientation. Both radical left-wing and radical right-wing populist parties mobilise around economic grievances, while radical right parties additionally stress cultural and ethno-nationalist conflicts (March and Mudde, Reference March and Mudde2005; March, Reference March2007; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bornshier, Reference Bornschier2010; Bonikowski and Gidron, Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016; Bernhard and Kriesi, Reference Bernhard and Kriesi2019). Moreover, opposition parties and political challengers typically express stronger populist sentiments than incumbents (Bonikowski and Gidron, Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016), since populist mobilisation is inherently an attack on the existing political system. Nevertheless, populist incumbents such as Donald Trump and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have also used populist rhetoric to portray their political opponents as part of a deep-rooted establishment determined to obstruct their agenda (Müller, Reference Müller2016).

In sum, the existing literature on populist politics, largely based on Western democracies, argues that underlying populist attitudes among voters do not necessarily translate into voting for populists. Rather, conditions such as economic hardship, political dissatisfaction, and the mobilisation efforts of populist figures are key factors that trigger a populist sway in elections.

3. Theoretical arguments

Surprisingly, research on populism and voting behaviours in Korea remains limited. Recent studies have analysed who holds populist attitudes (Ha, Reference Ha2018; Do, Reference Do2021a; Han and Shim, Reference Han and Shim2021; Jung and Do, Reference Jung and Do2021; Park, Reference Park2022; Song and Kim, Reference Song and Kim2023) and how populist attitudes influence outcomes such as political participation (Do, Reference Do2021b), preferences for institutions (Hur, Reference Hur2022; Hwang et al., Reference Hwang, Oh and Cho2022), and affective polarisation (Jang and Chang, Reference Jang and Chang2022). However, there is limited understanding of whether populist attitudes correlate with voting behaviours.

This paper argues that the 2022 presidential race in South Korea satisfied the three conditions for populist activation: economic difficulty, public discontent, and the rise of a populist candidate. First, several economic issues began to arise in 2020. The spread of COVID-19 hamstrung the South Korean economy. Despite the Moon administration’s efforts to control the pandemic, COVID-19 eventually spread to Seoul in August 2020, forcing the administration to implement stricter social distancing measures. While these measures hurt small business owners and self-employed workers, they did not immediately translate into public discontent with the Moon administration. According to a weekly Gallup Korea report, President Moon’s average approval rating in 2020 remained higher than that of his predecessors during their fourth years in office (Gallup Korea, 2020: 3).

Public discontent with the Moon administration began to grow when it announced a series of strict policies aimed at regulating the real estate market. One measure, introduced in July 2020, was an increase in property taxes for those who owned more than one home. The following month, the Moon administration, in cooperation with the Minjoo party, introduced the right to request a lease renewal and imposed a cap on rent increases to stabilise the lease and rental markets. Contrary to the administration’s expectations, however, the supply constraints and reduced transaction volumes drove housing prices even higher, severely undermining public trust in the administration (Chang and Yun, Reference Chang and Yun2022). In a survey conducted in mid-December 2020, 20% of respondents who evaluated Moon negatively identified housing policy as the reason, whereas only 7% mentioned economic hardships (Gallup Korea, 2020: 9). Facing housing market instability, renters reported pessimistic views of housing price stability and fear of missing out on home ownership. A new expression, younggul (putting one’s heart and soul into a home purchase), was coined to describe the behaviour of young renters, mostly in their 30s, who took out the largest loans they could to buy a house before prices rose even higher. Owners of single houses also expressed concern about the overheated housing market, which increased their tax burden and limited their mobility (Kang and Park, Reference Kang and Park2023).

The second condition, political discontent, began to become salient following the housing market surge, which eroded the perceived integrity of the ruling political elites. While President Moon’s overall approval rating did not drop dramatically, public opinion toward his economic and housing market policies grew increasingly critical (Chang and Yun, Reference Chang and Yun2022). Then, in 2021, a state-owned enterprise, the Korea Land Housing (LH) Corporation, was embroiled in a major scandal. Its employees used insider information to invest in areas slated for development with public funds, illegally reaping enormous profits (Korea JoonAng Daily, 2021). This scandal further undermined public trust in the Moon administration’s commitment to curbing speculation in the housing market. Consequently, Moon’s approval rating fell to a low of 29% in April 2021, when an investigation into the breach of trust allegations against LH was launched (Gallup Korea, 2022). Since then, polls have repeatedly indicated that dissatisfaction with Moon’s housing market policies motivated votes against him (Gallup Korea, 2021, 2022).

Hawkins and colleagues (Reference Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020) have emphasised that dissatisfaction with democratic governance is not driven by policy failures themselves, but by belief in the role of ‘intentional elite collusion’ in such failures. Amid housing market instability, scandals related to LH’s breach of trust and a presidential spokesman’s alleged real estate speculation emerged.Footnote 3 Regardless of the facts of the scandals, they would have led discontented citizens to believe that governmental elites were hypocritical or at least irresponsible. This aligns with the logic of mediated retrospective economic voting, whereby citizens punish incumbents only when responsibility for economic failure can clearly be attributed to them (Park et al., Reference Park, Frantzeskakis and Shin2019). Given this circumstance, we argue that economic grievances – particularly those arising from dissatisfaction with housing market policy failures – can readily be mobilised by populist candidates as a means to stimulate political dissatisfaction with the current system.

The final condition was met with the emergence of two arguably populist politicians, Lee Jae-myung and Yoon Suk-yeol. The international press used expressions such as ‘maverick’, ‘outsider’, and ‘anti-establishment figure’ when describing both Lee and Yoon (Mo, Reference Mo2022).Footnote 4 Lee, the liberal Minjoo party candidate, had long been considered a political outsider (Chae Reference Chae2019; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Krumbein and Mosler2025). Before becoming a professional politician, he was a lawyer with no connections to other human rights lawyers or democratisation movement activists, groups who make up the Korean liberal mainstream. He was mayor of Sungnam City from 2010 to 2018 and governor of Gyeonggi province from 2018 to 2021, but he had disagreements with then-President Moon and other mainstream members of the party. His opponents inside and outside the party criticised his famous campaign pledge of a universal basic income as an irresponsible populist tactic to buy votes, but he openly asserted that he would implement populist policies if they would help ordinary people.Footnote 5

Yoon, the candidate of the conservative party (the People Power Party, PPP hereafter), was new to politics. He served as a prosecutor for 27 years and was appointed Prosecutor General by President Moon, serving from 2019 to 2021. However, he confronted then-President Moon about reforms to the prosecutor system, which increased Yoon’s popularity among conservative voters. Despite his lack of a political career or experience, his image from fighting the Moon government led him to victory in the PPP primary.

Adding these three conditions together, we argue that the 2022 presidential race created a political environment in which voters’ latent populist attitudes could be activated. Economic hardship stemming from the housing policy failures, coupled with widespread beliefs in elite collusion, made economic grievances highly politicised. In such contexts, candidates who positioned themselves outside the traditional political establishment were able to mobilise these sentiments effectively by framing housing market failures as evidence of elite irresponsibility and corruption.

These dynamics should be understood within a longer historical trajectory. Since the post-International Monetary Fund restructuring period, real estate taxation, and housing-related grievances have formed a persistent axis of socio-economic discontent in South Korea, most prominently during and after the Roh Moo-hyun administration. This longstanding pattern of asset-based inequality, policy volatility, and declining trust in housing governance provided fertile ground for populist reframing. Against this backdrop, populist appeals that depicted housing market failures as products of elite collusion were likely to resonate especially strongly among citizens with pre-existing populist predispositions. In this sense, the 2022 presidential election is not an isolated or sudden instance of populism, but rather the culmination of sustained and accumulated socio-economic grievances.

Comparative studies in Europe and Latin America consistently show that individuals with populist attitudes do not automatically support populist candidates. As Hawkins and colleagues (Reference Hawkins, Read, Pauwels, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017) argue, these attitudes must be activated by particular socio-economic and political conditions. Yet, as discussed in Sections 2 and 3, Korean populism research has paid limited attention to which politicians articulate populist messages and how these messages connect to voters’ electoral choices. This study, therefore, examines whether populist attitudes correlate with vote choice under conditions that are theoretically conducive to populist activation.

H1: Populist voting emerges when the three conditions for populist activation are met: economic hardship, widespread public discontent, and the emergence of a populist contender. In presidential elections characterised by these conditions, citizens holding latent populist attitudes are more likely to support candidates who advance populist political messages.

Our theoretical expectations assert the moderating effects of two conditions that activated populist attitudes in South Korea: economic dissatisfaction and political dissatisfaction. The effects of populist attitudes on voting should be stronger among those who are economically disadvantaged and politically dissatisfied, because those conditions render populist rhetoric more plausible and persuasive. Considering the rising importance of anti-elitist sentiments in conservative discourse and the salience of housing-related economic losses in evaluating incumbent presidents in Korean politics, those economic and political conditions serve as conduits through which populist attitudes are translated into populist voting behaviours. Financial losses stemming from the recent housing market surge are widely interpreted not simply as policy failures but as outcomes of elite mismanagement or collusion, making populist economic frames particularly plausible for affected individuals. Similarly, political dissatisfaction does not activate populist attitudes on its own; its effect becomes more pronounced when voters encounter candidates who explicitly frame their campaigns in anti-elitist, anti-establishment terms – as was the case in the 2022 presidential race.

In contrast, populist rhetoric would be less persuasive among those who benefited from the housing market surge or those who are content with contemporary politics and existing representative institutions, even if they hold latent populist attitudes. Some recent works have supported these expectations. For example, Park (Reference Park2022) has argued that the economically insecure class holds stronger populist attitudes, and Song and Kim (Reference Song and Kim2023) have shown that those who expressed less satisfaction with Korean politics were more likely to hold populist attitudes. Thus, we hypothesise the moderating effects of economic and political conditions as follows.

H2 (Moderating Effects of an Economic Condition):

The positive association between citizens’ populist attitudes and support for a populist candidate will be more salient among those who report economic losses from the recent housing market surge.

H3 (Moderating Effects of a Political Condition):

The positive association between citizens’ populist attitudes and support for a populist candidate will be more salient among those who are politically dissatisfied with the current democratic system.

4. Qualitative analysis: populist messages in campaign speech

4.1. Qualitative research design: holistic grading

This paper uses a mixed-methods design: qualitative methods to evaluate the politicians’ populist rhetoric and quantitative methods to analyse vote choices. First, qualitative methods rely on a holistic assessment of the content of campaign speeches. As populism has a thin-centred ideology, attentive analysis of both the literal content and the tone and style of political speech is needed. The same words, phrases, and sentences may convey different meanings if spoken by different individuals in different contexts. Thus, researchers studying populist rhetoric from elites must interpret ‘a broad, latent set of meanings in a text’ and scrutinise ‘broader, more complex patterns of meaning’ (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009: 1049–1050).

Holistic grading is the most suitable technique that can address the apparent rise of populism in the 2022 elections.Footnote 6 Holistic grading, developed by educators for pedagogical assessment, asks coders to make a comprehensive judgement on the overall qualities of a text and assign a single grade based on a rubric with ‘anchor’ texts (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2009: 1049). The anchor texts provide the coder with grading criteria they can use to judge other individual texts.

For a qualitative analysis, we collected all 172 public speeches made during the official campaign period for the 20th presidential election, from February 15, 2022, to March 8, 2022. Yoon made 91 speeches during the period, while Lee made 81. We checked the date and location of the speeches using the official website of both parties’ electoral headquarters. We watched all speeches recorded on their official YouTube channels and transcribed the contents using Clova note. All coders double-checked to ensure the transcripts were accurate. We did not include televised presidential debates, radio, or TV political advertisements, because these dialogues were too brief to convey coherent ideas and, thus, unsuitable for holistic grading.

An anchor text is Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2009)’s holistic grading rubric, as outlined in Table A1 in the appendix. The grading rubric captures key components of populism, including people-centrism (Elements 3 and 5), anti-elitism (Elements 5 and 6), the Manichaean world view (Elements 1, 4, 5 and 6), and the portrayal of a messianic leader (Element 2). In Element 4, the ‘evil’ is identified by the Korean political context, such as extreme pro-North Korean communists (‘Jongbuk Jwapa’, ‘Jusapa’ in Korean),Footnote 7 fortune tellers, and warmongers of using ‘North Wind’.Footnote 8

The grading scale ranges from 2 to 0: a score of 2 indicates a speech that is populist, satisfying more than 4 elements in Table A1; a score of 1 indicates a speech with populist elements that may be inconsistently applied, having at least 2 elements in Table A1; and a score of 0 indicates a speech with few, if any, populist elements.

All four coders independently graded each speech. To ensure consistency, they engaged in regular communication to maintain a shared understanding and application of the coding rubric. Some variations in grading were observed across coders. Table A2 in the appendix presents the mean values and standard deviations of each coder’s scores. Coder A consistently assigned the highest scores, while Coder D was the most conservative in judging a speech to be populist and assigned the lowest scores. Coders B and C demonstrated grading patterns that were relatively similar to each other. We do not view the variation in coding as a problem, as it was systematic rather than random – all four coders consistently rated Yoon’s speeches as more populistic than Lee’s.

The inter-coder reliability among the four coders, measured using Krippendorff’s alpha, was low (0.294). As a robustness check, we recalculated the alpha after excluding Coder D, whose evaluations diverged from the others the most. The revised alpha increased to 0.675, approaching the threshold commonly considered acceptable in qualitative coding studies. For transparency, we report the results using both the average scores of all four coders and the averages of the three more consistent coders.

4.2. Results of the presidential speech analysis

We have argued that both Lee and Yoon have the potential to be perceived as populist politicians. In this section, we present the results of our qualitative analysis, exploring the extent to which the two candidates employed diverse rhetoric and personalised narratives to evoke populist sentiments among the public, using rhetorical emphasis on people-centrism, anti-elitism, and a Manichaean worldview.

Figure 1 presents the mean holistic populism scores across all 172 campaign speeches. Panel (A) displays the results based on the average scores of all four coders. Yoon’s speeches received a mean score of 1.120 (SD = 0.270), while Lee’s received a mean score of 0.201 (SD = 0.238). Panel (B) presents the results based on the three-coder average. Yoon’s speeches scored 1.432 (SD = 0.349), whereas Lee’s averaged 0.267 (SD = 0.318). Although the absolute scores slightly differ, both graphs reveal the same pattern: Yoon delivered more populistic speeches than Lee throughout the campaign period.

Figure 1. Hawkins’ populism scores for Yoon and Lee.

Yoon consistently employed populist elements in his speeches, with his populistic rhetoric becoming slightly stronger as the race progressed. He primarily relied on anti-elitism, accusing liberal politicians, including Lee, of being corrupt and incompetent establishments. Yoon also portrayed himself as a messianic figure, called upon by the people to enter politics and challenge the establishment – a common strategy used by populists.

In contrast, Lee relied less on populist rhetoric during his official campaign, except in late February, when he vigorously defended himself against allegations related to a real estate development scandal. Lee’s relative restraint may seem puzzling, given that he had frequently employed populist themes such as people-centrism and anti-elitism prior to his nomination. While our analysis of his speeches cannot provide the precise reasons for his shift from populist messaging to more restrained rhetoric, we speculate that, as the candidate of the incumbent ruling party, he may have believed that anti-elite messaging would be less effective or even contradictory. Alternatively, pressure from the Minjoo Party’s mainstream leadership may have encouraged him to adopt a more moderate tone.

The following are examples of candidates’ speeches and their holistic grades, which may elucidate the grading scheme.Footnote 9 The following two statements both were scored 1 (mixed). They have strong populist elements moderated by non-populist elements. Yoon asked,

Dear beloved citizens of Busan, have the past five years under the Minjoo Party government been satisfactory for you? Do you think we should let them govern for another five years? They have destroyed the Republic of Korea and ruined the lives of our common people. What did they say when they came here? Instead of revitalizing Busan, they said Busan is dull and boring. Do you think Busan is boring? My heart races when I get off at Busan Station. How exciting and wonderful is Busan? Should we experience this ungrateful government one more time? Can we watch the Republic of Korea, which you have protected and nurtured, continue to be torn down by a corrupt and incompetent political force?

(Yoon Suk-yeol, Busan, February 15, 2022)

In the first part of this speech, Yoon argued that another five-year presidency under a Democratic President would ‘tear down’ the entire country because Lee and his political aides were ‘corrupt’ and ‘incompetent’. This is typical populist rhetoric in which ‘the evil minority is or was recently in charge and subverted the system to its own interests, against those of the good majority or the people’ (Table A1, Populist Elements #5). Yoon, coming from outside politics, claimed he was morally compelled to stand up for the people. This is also typical populist rhetoric, portraying the populist leader as a messianic figure.

However, the populist elements are tempered by the second part of the speech. In the part, he elaborated on his development strategies for Busan, aimed at attracting private investment. This part is non-populist because they discuss policy issues without taking a dogmatic stance. Thus, this statement is scored 1 (mixed), as it maintains a balance between populist and pluralist elements.

In the next mixed statement, Lee began by describing the 2022 presidential election as a ‘crucial’ choice between good and evil.

The choice on March 9 is not between Lee Jae-myung and Yoon Seok-yeol. The choice on March 9 is about you, your future, and the future of your children. It is about whether the future of South Korea will progress or regress, move forward or backward, become a battleground of political retribution or a hopeful society where growth and fair opportunities are shared among the people. You make this crucial decision. But I believe in you. I believe in the people. I believe in collective intelligence, public sentiment, and the will of the heavens. That is why I have come this far. Although I had nothing, you saw the small achievements of Lee Jae-myung and brought me here. Can I trust you? On March 10, two worlds will open. Two doors will open: one leading to a hopeful future in the same world, and the other leading to a past filled with retribution. The choice between these two doors is yours. Even if you are not present here, if you tell the nation about Lee Jae-myung’s capabilities, achievements, and trustworthiness in fulfilling his promises, the door to hope will open. This is the city of comics and culture, right? Congressman Won Hye-young, whom I personally respect, accomplished a lot when he was the mayor here. Isn’t that true? You know that I supported many comic projects as governor, right? It seems you don’t know well. Culture is indeed very important. Kim Gu once said he wanted to create a nation with an endlessly high level of culture. A cultural powerhouse does not cost money or generate carbon emissions … I will make Bucheon a cultural city where all citizens can live without worrying about jobs, a city of cultural content, and repay you with certainty. I trust you, and now I will move on to another place. Thank you.

(Lee Jae-myung, Bucheon, February 22, 2022)

If Yoon is elected president, Lee argues, South Korea will become ‘a battleground of political retribution’ that wastes the country’s potential and sensible citizens of South Korea should not sacrifice their children’s future by picking Yoon as president. These expressions fall into the category of populist rhetoric in the sense that ‘there can be nothing in between, no fence-sitting, no shades of grey’ (Table A1, Populist Elements #1). Additionally, Lee emphasises ‘the will of the people’, which he assumes is equivalent to ‘the will of the heavens’. By stating that he has strong faith in both, Lee implies that he is the legitimate representative of the people, a common trope in populist rhetoric.

Later in the speech, however, Lee concentrates on the unique characteristics of Bucheon, a city famous for its support of the culture industry, and stops using bellicose language. Lee explains his approach to Bucheon’s local economic issues without going into detail. This statement is also graded 1 because it contains a mix of populist and pluralist elements.

The last excerpt is a speech by Yoon, graded 2 (populist). Interestingly, no speeches by Lee received a grade of 2.

Citizens of Changwon, it is a pleasure to meet you in front of Masan Station. Isn’t Masan the sacred ground of our country’s democratization and the place that has dramatically changed the history of South Korea? Why are you supporting and encouraging me with your phone lights at this hour? It’s because, over the past five years, you have seen enough of the corrupt, incompetent, and arrogant government that disrespects its people, and you want to change it. You have endured well over these five years. You even supported the government during local and general elections, hoping they would do well. But now, our people have lost all hope.

This outdated group of ideologues cannot be entrusted with our future, and that has been proven. That’s why I always talk about fairness and common sense. The fundamental principles of state administration adopted by all free, advanced countries worldwide are common sense: liberal democracy and a market economy, where every citizen is treated fairly. We all now understand that our country must operate on these principles to have hope. Isn’t it time to rid our country of outdated ideological politics? These politicians, who gather in factions, sharing high-ranking public positions among themselves, colluding with connected businesses, and ignoring the people who are the true owners of this country, can they reform politics? Can they bring about political change? Political change must come through a change in government! Will normal people gather under the banner of corrupt and incompetent individuals?

Look over there. In Seongnam, with a population of one million, Kim Man-bae’s gang entered a city development project with 3.5 billion won and took away 850 billion won. They are now in prison, but the money keeps coming in as apartments continue to be sold. Is this Lee Jae-myung’s greatest achievement since Dangun? No, it’s the greatest corruption since Dangun. What is the party that nominates the ringleader of this corruption as their presidential candidate? For the past five years, the people supported this party, and they did nothing but divide the people, practice double standards, monopolize committee chairmanships, pass bills in the middle of the night, and commit all sorts of misdeeds. Now, ten days before the presidential election, they talk about constitutional amendments and political reform. You won’t be fooled by their sweet talk, right?

Citizens of Changwon, political change means ousting and replacing these corrupt and incompetent politicians from the Minjoo Party. There are good and honorable people in the Minjoo Party. However, those who have ruined the past five years of the Moon Jae-in administration have now flocked to Lee Jae-myung and are leading his Minjoo Party. If you give overwhelming support to me and the People Power Party, we will cooperate with the honorable politicians in the Minjoo Party to achieve national unity and economic development.

(Yoon Suk-yeol, Changwon, March 3, 2022)

The excerpt is populist. It primarily depicts the presidential election as a choice between right and wrong (Table A1, Populist Elements #1). Yoon continuously highlights that there is no place in Korean politics for Lee and ‘this outdated group of ideologues’. According to Yoon, Lee and the Minjoo Party do not believe in liberal democracy or the market economy, ‘the fundamental principles of state administration adopted by all free, advanced countries worldwide’. Yoon uses a conspiratorial tone, describing the opposition as blind seekers of economic interest (Table A1, Populist Elements #4). Yoon also displays a lack of respect for an important political institution, the Korean National Assembly, where the Minjoo Party holds a majority (Table A1, Populist Elements #6). Using incendiary rhetoric, Yoon argues that to revive the country, people should ‘give overwhelming support to’ him and the PPP.

Overall, the degree to which the two candidates evoked populist sentiments among the public varied during the campaign period. Lee was less reliant on populist rhetoric than Yoon. Thus, based on these findings, we update the main hypothesis as follows:

H1-1: Citizens with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to have supported Yoon, who supplied more populist political messages than Lee did.

The following section analyses whether the populist rhetoric employed by each of the two presidential candidates influenced individual vote choices, and more precisely whether citizens with populist attitudes voted for Yoon more than for Lee, as H1-1 predicts.

5. Quantitative analysis: populist attitudes and voting

5.1. Data and measurement

For the quantitative analysis, we used online panel surveys conducted before and after the 2022 presidential election. The pre-election survey was conducted from November 16 to November 18, 2021, before the official campaign started. Using a structured online questionnaire, we collected responses from a total of 1800 male and female adults (aged 18 or older), randomly sampled following the population composition in terms of gender, age, and region. The response rate was 46.9% (3836 contacts, 1800 completed surveys), with a margin of error of ±2.3 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. The post-election survey was conducted immediately following the presidential election, from March 12 to March 16, 2022. Out of the 1800 respondents to the initial survey, 1058 completed the post-election survey and were included in the sample. Note that despite the panel structure of the survey data, our empirical model applies a logistic multivariate regression, not a panel regression, because populist attitudes are assessed only in the pre-election survey, under the assumption that they would not change over the four months between the pre- and post-election surveys.Footnote 10

The dependent variable is respondents’ voting intention or choice. In the pre-election survey, Vote Intention for Yoon (Lee) is coded 1 if the survey respondent expressed an intention to vote for Yoon (Lee), and 0 otherwise, including ‘undecided’ or ‘don’t know’ answers. In the post-election survey, Vote Choice for Yoon (Lee) is coded 1 if the survey respondent answered that they voted for Yoon (Lee), and 0 otherwise, including ‘didn’t vote’ or ‘don’t know’ answers.

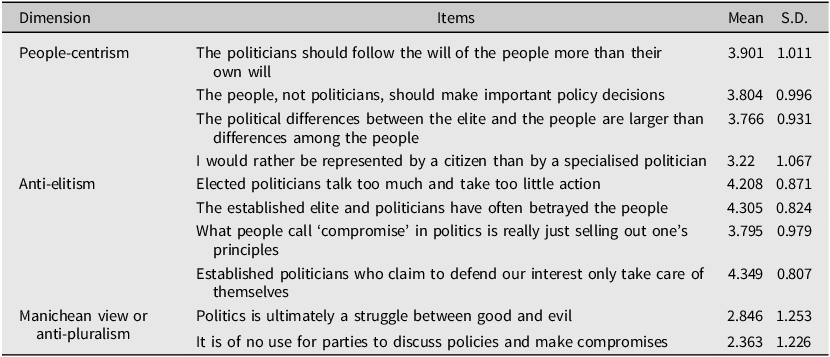

The independent variable, populist attitudes, is measured using ten items shown in Table 1. Eight come from previous research (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016), and capture aspects of people-centrism (items 1–4) and anti-elite sentiments (items 5–8). We added two more items to assess potential Manichean worldview and anti-pluralist tendencies, believing that Akkerman’s eight items do not fully capture these aspects of populism. The populist attitude scale is calculated according to IRT (Item Response Theory), a mathematical model that describes the non-linear relationship between a latent variable and an individual’s responses to a survey question (Ellis, Reference Ellis1989). Van Hauwaert et al. (Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo2020) recommend IRT methods because populist attitudes are latent variables whose components are not always linear. IRT is known to outperform other methods in capturing the effect of an underlying latent construct on variables, especially when individual responses to a particular survey question are given on ordinal scales (Ellis, Reference Ellis1989; Bartholomew and Knott, Reference Bartholomew and Knott1999).

Table 1. Items measuring populist attitudes

Note: All items are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

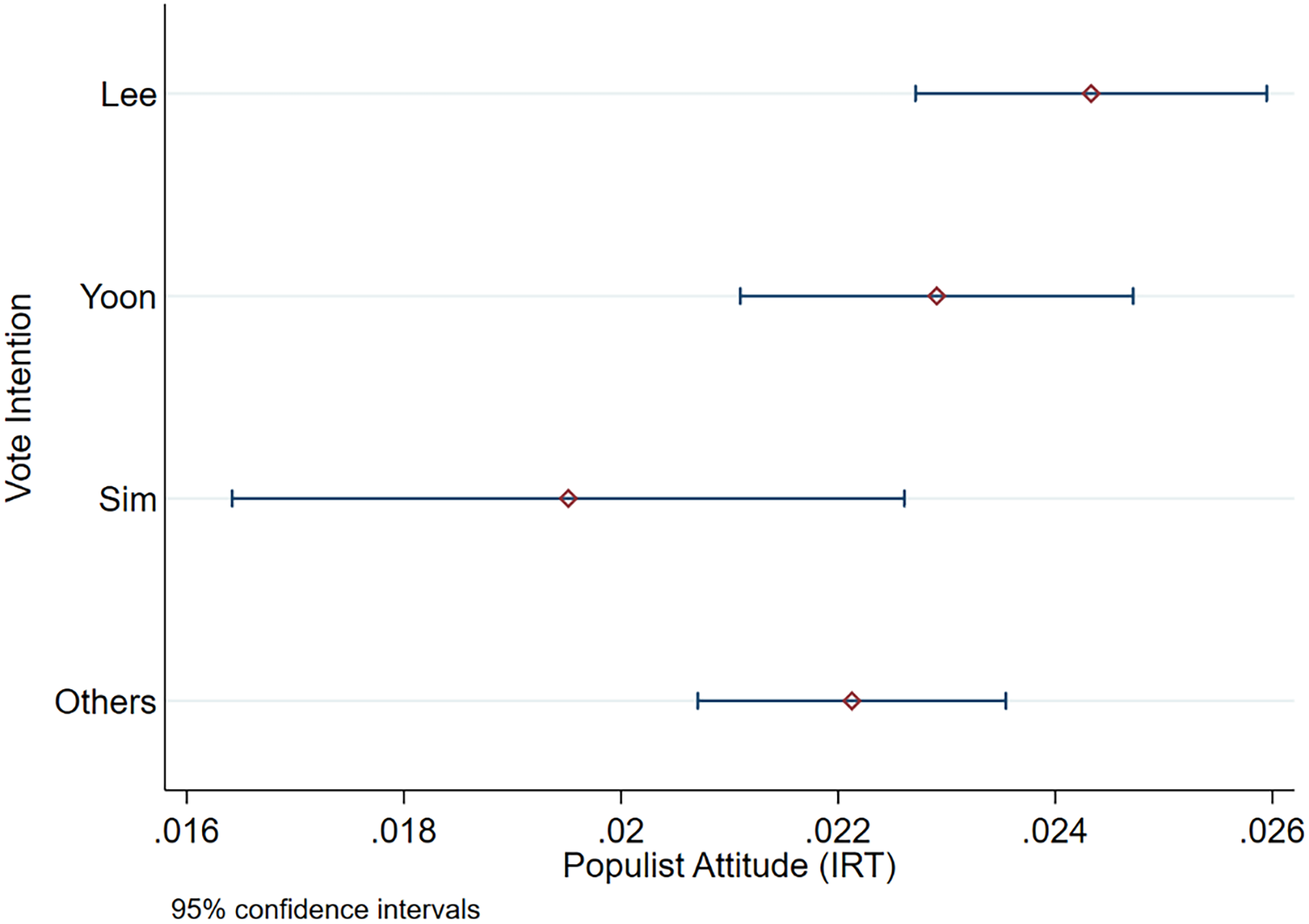

Figure 2 displays the mean values of populist attitudes by voting intention in the pre-election survey. The mean score for Yoon supporters is 0.023 (SD = 0.020), while the mean for Lee supporters is 0.024 (SD = 0.019). The difference is not statistically significant, suggesting that populist attitudes were not solely concentrated among Yoon supporters or any other supporter group before the campaign.Footnote 11

Figure 2. Mean values of populist attitudes (IRT) by vote intention.

We include variables to capture the effects of economic and political conditions, such as the housing market policy failure and dissatisfaction with the current democracy. Housing market effect is measured by respondents’ evaluation of the extent to which their household finances were influenced by recent changes in housing prices. We use an item measured on a 5-point Likert scale, in which responses included ‘made a huge profit’ (coded 1), ‘made a small profit’ (coded 2), ‘no influence’ (coded 3), ‘suffered a small loss’ (coded 4), and ‘suffered a huge loss’ (coded 5). The dissatisfaction with democracy item asked respondents to express their level of satisfaction with the current democracy in Korea on an 11-point scale, with a higher score indicating greater dissatisfaction.

The model includes control variables for factors that could influence voting choices, such as party identification, self-reported ideology, policy preference, approval rating of the then-incumbent president, political interest, and demographic features. Party identification is measured using dummy variables for support of each political party (the Minjoo Party, the PPP, other parties, or none). Second, self-reported political ideology is measured on an 11-point scale, ranging from most liberal (0 points) to most conservative (10 points). Third, to control for voter policy preferences, respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with a total of seven policy itemsFootnote 12 on an 11-point scale, with a higher score indicating greater alignment with the policy direction advocated by conservative party candidates. Fourth, respondents’ approval ratings of President Moon Jae-in’s job performance were assessed on an 11-point scale ranging from ‘very poor’ (0 points) to ‘very good’ (10 points). Fifth, the model includes respondents’ level of political interest, measured using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not interested at all’ to ‘very interested’.

Finally, demographic variables included household income (measured on a 10-point scale with response options ranging from less than 1 million won to over 9 million won, segmented into 100,000-won units), educational level (measured on a 5-point scale, with less than junior high school education scored as 1, high school education as 2, vocational college education as 3, undergraduate education as 4, and postgraduate education or higher as 5), gender (with males coded 1 on the dummy variable), and five dummy variables for age (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, or 60s and up). Fixed effects for regions were included to control for regional characteristics that could affect the dependent variable. As the sample allocation by region has issues of dependence among respondents in the same region and high independence across different regions, cluster-robust standard errors at the province-level were used to address this issue. Table A3 in the online appendix displays summary statistics for all variables used in the analysis.

5.2. Empirical results

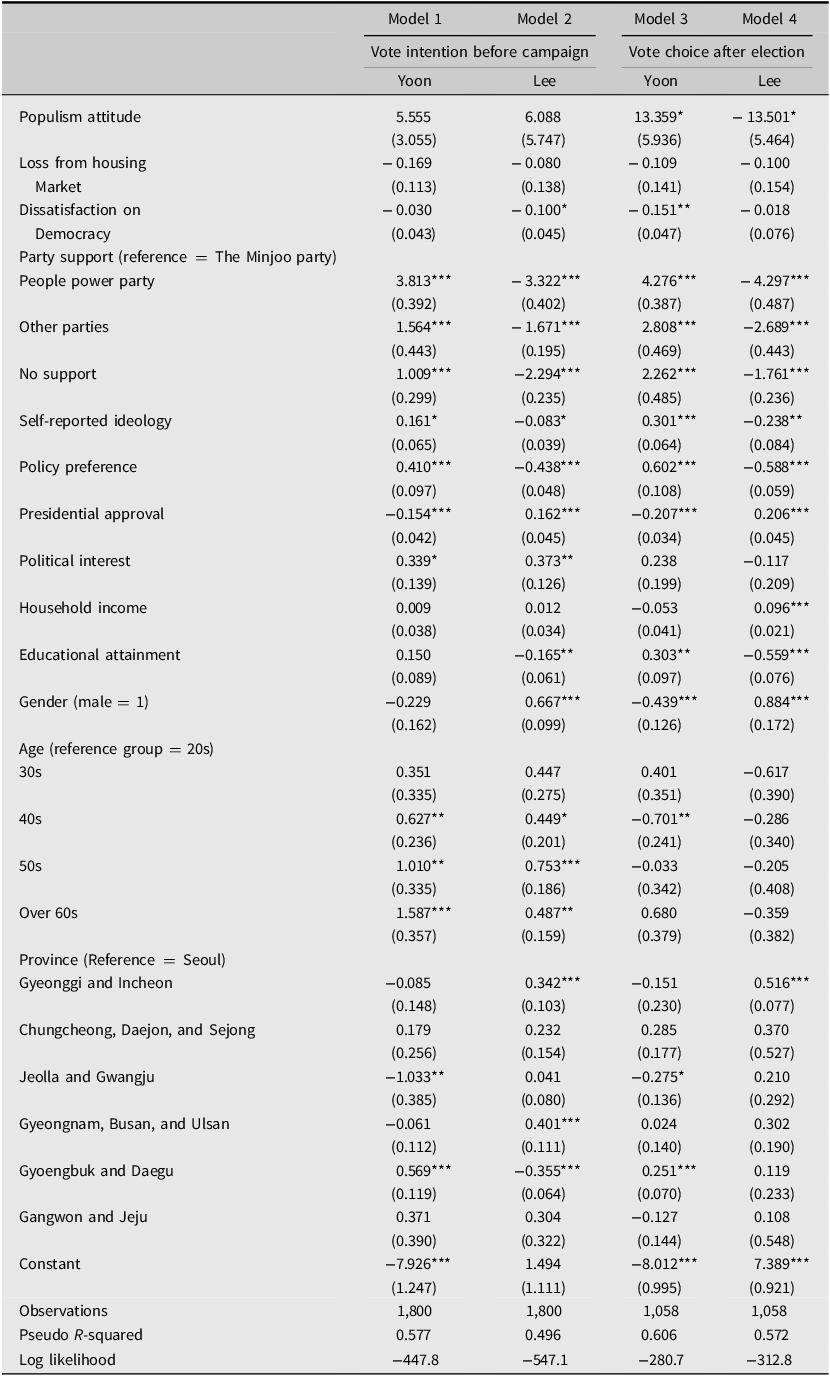

Table 2 displays the empirical analysis of testing hypotheses. As shown in Models 1 and 2, populist attitudes have no statistically significant association with respondents’ voting intentions before the campaign. However, as Models 3 and 4 show, those with stronger populist attitudes were more likely to vote for Yoon and less likely to vote for Lee on election day. We infer that the varying effects of populist attitudes before and after the campaign are due to the different levels of populist mobilisation from the two candidates. Given the perception that both Lee and Yoon have the image of a populist, it would be unclear for voters with populism attitudes to identify who is closer to them. As the holistic grading of the two candidates’ campaign speeches shows, however, Yoon expressed stronger populist rhetoric than Lee did after the official campaign started. The empirical results from Models 3 and 4 imply that Yoon’s populist signalling resonated among those with strong populist attitudes.Footnote 13

Table 2. Populist attitudes and votes in the 2022 presidential election

Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors are clustered at the province level.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Among the control variables, partisan factors such as party identification, political ideology, policy preferences, and approval of the president were strongly correlated with both voting intentions and final vote choice. Those who supported the PPP, held conservative ideology and policy preferences, and evaluated then-incumbent President Moon negatively were more likely to vote for Yoon. Conversely, those who supported the Minjoo Party, held liberal ideology and policy preferences, and evaluated then-incumbent President Moon positively were more likely to vote for Lee. These results indicate strong effects of partisanship and ideological positions on voting. However, even after accounting for these partisan and ideological effects, populist attitudes still exerted a significant influence on voting behaviour in the 2022 presidential election. The effects of gender and education are also evident in both surveys: women and the less educated were more likely to support Lee than Yoon.

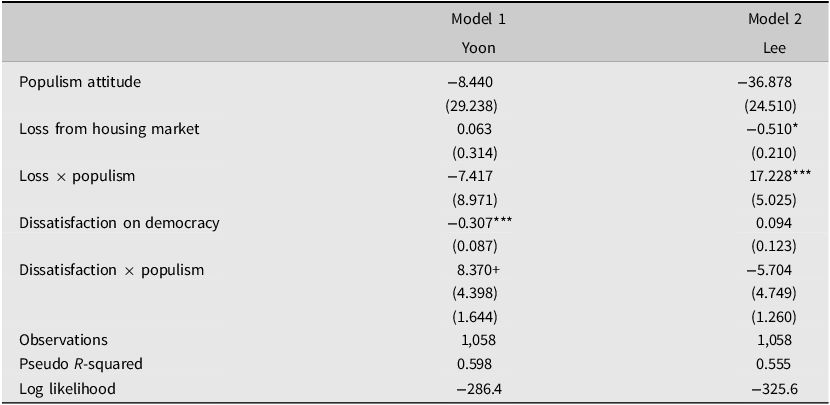

Our additional hypotheses argue that the effect of populist attitudes on vote choice is stronger among those negatively affected by the rising housing market and those who were dissatisfied with democracy (Hypotheses 2 and 3). The models in Table 3 display the reduced results of the empirical analysis of these hypotheses. Note that we analysed only the post-election survey because populist attitudes influenced vote choice after the campaign, as shown in Models 3 and 4 of Table 2.

Table 3. Moderating effects of economic and political conditions (reduced form)

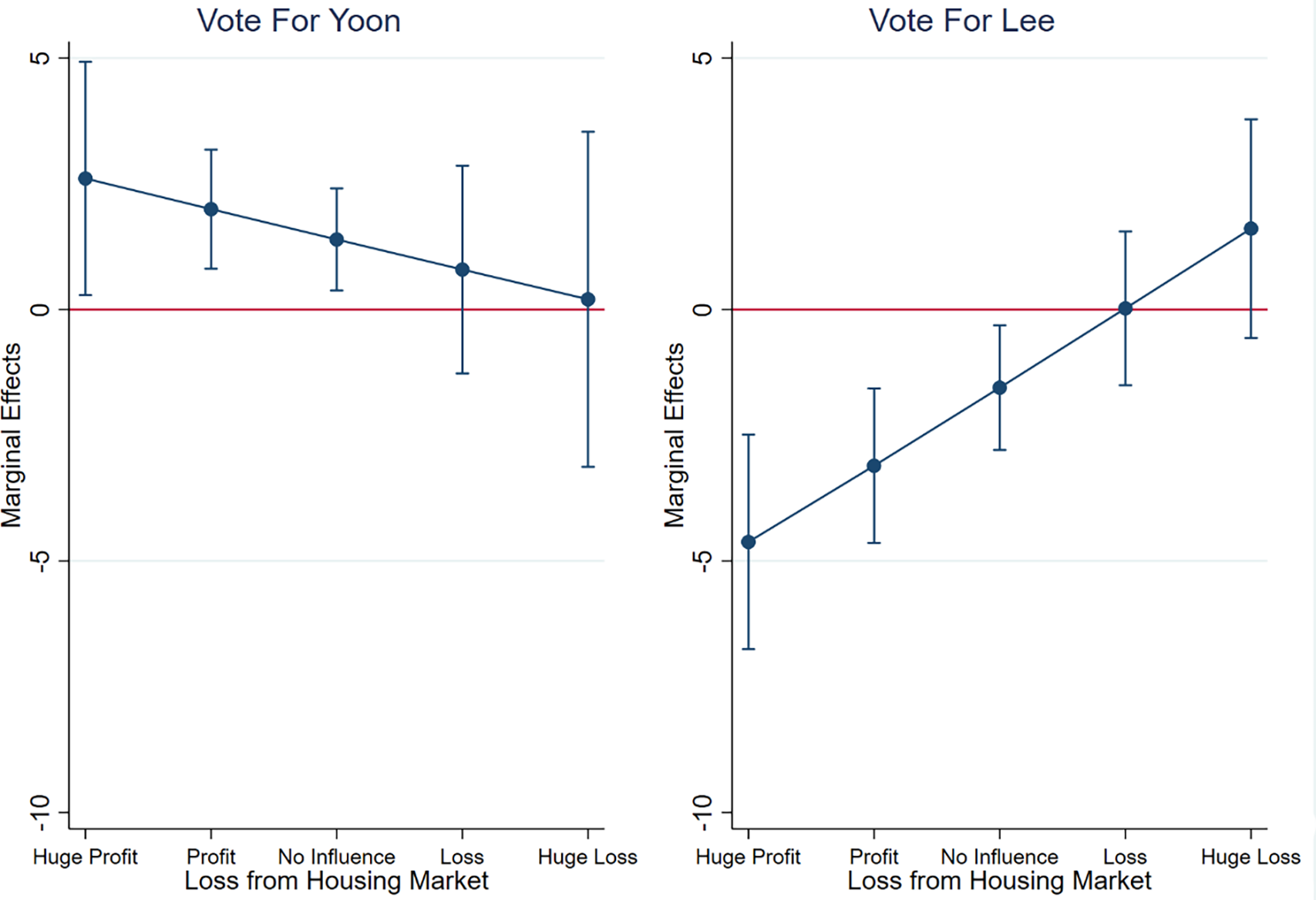

Table 3 includes two models that display the two interaction effects on votes for Yoon and Lee, respectively. For easier interpretation of the results, Figures 3 and 4 display the marginal effects of the two moderating variables on the effects of populist attitudes on votes for Yoon (Model 1 of Table 3) and Lee (Model 2 of Table 3), respectively.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of housing market loss on vote choice.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of dissatisfaction with democracy on vote choice.

Figure 3 displays the marginal effects of a loss in the housing market on the association between populist attitudes and voting. In the left panel, those who held stronger populist attitudes overall were more likely to vote for Yoon. However, the marginal effects of populist attitudes were positively associated with votes for Yoon only among respondents who profited or were unaffected by the housing market surge. When respondents reported a loss in the housing market, the effects of populist attitudes on voting for Yoon were smaller and statistically insignificant.

The right panel of Figure 3 displays the marginal effects of populist attitudes on votes for Lee, moderated by financial outcomes from the housing market. Overall, those who held stronger populist attitudes were less likely to vote for Lee. For voters who suffered a loss in the housing market, the effect of populist attitudes on their vote choice became statistically insignificant. However, among those who profited from the housing market or were unaffected, the negative effect of populist attitudes on voting for Lee became stronger and more significant.

The findings in Figure 3 are contradictory to H2 and the conventional theory of retrospective economic voting, especially given that Lee was the incumbent party’s candidate. According to the theory, personal economic gains should increase support for the incumbent, even among populist voters who might otherwise be critical. Yet, our results reveal the opposite: populist voters who benefited from the housing surge were the most likely to vote against Lee. While this counterintuitive outcome is complex, we conjecture that the key lies in the issue of attribution. Although these voters profited from the housing market surge, they may not have attributed this benefit to government action. Alternatively, drawing on Kang and Park (Reference Kang and Park2023), who show that both homeowners and renters feel dissatisfied when housing market prices surge, populist voters may have been frustrated with housing market instability despite their own temporary gains, and thus punished the incumbent party candidate more severely.

Figure 4 displays the marginal effects of dissatisfaction with democracy on the association between populist attitudes and voting behaviour. Both the right and left figures show that when respondents were satisfied with the current democracy, the effects of populist attitudes on voting for either Yoon or Lee were not statistically distinguishable. However, for those who were dissatisfied with democracy, as their dissatisfaction increased, the marginal effects of their populist attitudes on their support for Yoon increased. That is, populist voters supported Yoon to the extent that they were discontent with the current democracy. This result supports H3.

Regarding voting for Lee, as shown on the right side of Figure 4, the marginal effects of dissatisfaction with democracy on the association between populist attitudes and votes for Lee were not statistically significant, except when the level of satisfaction was neutral. Voters with populist attitudes were less likely to support Lee only when they did not have a strong opinion as to their satisfaction level with the democracy.

6. Conclusion

The relative inattention to East Asian populism in the comparative politics literature presents significant challenges to research on populist practices in the region (especially Klein et al., Reference Klein, Krumbein and Mosler2025). Although it is important for researchers to maintain conceptual rigour as they investigate various forms of Asian populism, many have paid little, if any, attention to conceptual generalisation and theoretical coherence in examining these phenomena. Indeed, many studies in this field have highlighted emerging populist politicians in the region and their innovative mobilising skills within country-specific contexts without discussing the relevance of these findings to the broader literature on populism. Some previous studies of Korean populist politicians have suffered from this flaw, which we attempt to address in this article.

After examining the populist rhetoric of the two candidates in the 2022 presidential election and the effects of populist attitudes on voting behaviour, we argue that even in a political context where populism has not historically been a prominent force, it can nevertheless influence elections when certain economic and political conditions are met. More concretely, we employed holistic grading – a qualitative method – to assess which candidate relied more heavily on populist rhetoric during the campaign period, thereby minimising any potential researcher bias in adjudicating who counts as ‘more populist’ in the Korean political context. In addition, we analysed pre- and post-election surveys using IRT methods and found that respondents’ populist attitudes become systematically associated with their voting choices only in the post-election context.

However, we acknowledge that our study has certain limitations, which we hope to address in future research. First, we cannot compare our findings with research on previous Korean presidential elections where non-populist candidates competed, as no individual-level survey data measuring respondents’ populist attitudes prior to the 2022 presidential election are available. In addition, with the observational data we collected, we cannot assess the extent to which respondents actually heard or were exposed to the populist discourse in presidential candidates’ speeches. We assumed that all voters were equally exposed to the candidates’ speeches, which might not be true given voters’ varying levels of media consumption or exposure to particular media environments. Second, our study focused solely on the candidates’ official campaign speeches, thereby excluding their remarks in televised debates or other media contexts such as conversations on radio programmes. As a result, any populist rhetoric expressed in those interactions was inevitably omitted from the analysis.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study promotes a broader understanding of populism in South Korea and in East Asian countries in general. Our research implies that no country is free from populist influence, even those that have not experienced populist politics before. When key conditions such as economic difficulties, political dissatisfaction, and economic grievances against the political establishment hold, underlying populist attitudes can suddenly be activated. Once politicians who mobilise these sentiments emerge on the national political stage, such as Kamiya Sohei from Japan’s Sanseitō Party (Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2025), citizens with populist attitudes will vote for them.

Second, our holistic grading analysis of the speeches of the two presidential candidates illustrates the need for a more systematic examination of Asian politicians’ populist messages in order to identify populist figures according to the widely accepted ideational definition and to compare them with populist politicians in other democracies. East Asian countries are missing from the large datasets on populist politicians, such as the Global Populism Database (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Aguilar, Jenne, Kocijan, Kaltwasser and Castanho Silva2019), produced through holistic grading of political speeches, and PopuList 3.0 (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou, Froio, van Kessel, de Lange, Mudde and Taggart2023), a database of populist parties based on surveys of experts. We believe our study can serve as a useful starting point for advancing a more systematic and comparable source of information on populist politicians in Korea and East Asia more broadly.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109925100200

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Haemin Yu and Jiyeong Bae for their excellent research assistance.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Incheon National University Research Grant in 2024.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.