Introduction

The last few decades have witnessed increasing interest in volunteerismFootnote 1 in retooling citizenship,Footnote 2 civic renewal and societal revitalisation (Polidano, Harris & Zhao, Reference Polidano, Harris and Zhao2009; Allum, Reference Allum2012). This interest is informed, in part, by normative assumptions about volunteerism and its relationship to civil society,Footnote 3 citizenship, and social cohesion (Obadare, Reference Obadare2011). For a dominant school of thought, volunteerism is said to be positively correlated with progressive values that promote participation in wider socio-political and governance processes, as well as in promoting socially equitable socioeconomic and political outcomes, through enhancement of social capitalFootnote 4 and social cohesion (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; CIVICUS, IAVE & UNV, 2009).

Within this line of thought, voluntary associations are hailed as the hallowed ‘training schools’ that impart and foster civic attitudes and values consistent with progressive citizenship, as well as enhance opportunities for citizens’ socio-political engagement (Fung & Wright, Reference Fung and Wright2003; Cohen & Rogers, Reference Cohen and Rogers1995; De Tocqueville, 1835; Reference De Tocqueville1990). Such good citizenship values and attitudes include trust in government and other citizens, political and social tolerance, satisfaction with democratic processes, attention to public good, habits of cooperation, respect for others and rule of law, willingness to participate in public life, self-confidence and citizens’ belief in their ability to influence political affairs (Brehm & Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997). Such values, it is argued, are the ties that bind citizens to one another, and ensure powerful norms of generalised reciprocity and cooperation, and by extension, social cohesion, as citizens take active roles in their community, behaving morally, and compromising to accommodate even those that are different from themselves (Brehm & Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000).

Sceptics however, charge that this is only a partial story on the role of volunteerism in the production of citizenship values. Specifically, Staeheli et al., (Reference Staeheli, Marshall and Maynard2016: 377) argue that citizenship is complex and is “given form, meaning, and power, through the transactions and circulations that constitute it” (see also Obadare, Reference Obadare2011; Warburton & Smith, Reference Warburton and Smith2003; Milligan & Fyfe, Reference Milligan and Fyfe2005 for similar arguments). Of additional relevance here, is state’s role in framing and determining the space and scope for civil society, citizens’ freedoms and allowable volunteerism activities. For example, volunteerism in contexts that do not allow citizens’ free expression will not lead to positive outcomes. Indeed, as Obadare (Reference Obadare2011) reminds us, history is replete with evidence of groups like the Ku Klux Klan who rely on volunteer membership to propagate their hate. There is, therefore, a dark side to volunteerism (Smith, Reference Smith2008). As such, unless the underlying complexity of volunteerisms’ anchorage in the nature of circulations in existing social organisations is fully comprehended, its positive ideals cannot be fully realised, even with the best of intentions (Obadare, Reference Obadare2011).

Notwithstanding existing scepticism, actors within the citizenship industry,Footnote 5 have championed volunteerism without asking critical questions about the kind of benefits likely to accrue in different environments (Obadare, Reference Obadare2011: 6). Fiji has not been left behind in this pursuit. In this regard, Fiji government established Fiji Volunteer Services (FVS) under the National Employment Centre (NEC) Decree of 2009 to tap into volunteerism in tackling national and regional development challenges (Fiji Sun, 2014). This is in addition to the National Youth Service and the Duke of Edinburgh Programs which specifically target youth volunteers (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012). Following suit, other organisations including Fiji Council of Social Services (FCOSS), Vodafone-ATH Foundation, and a variety of political parties, sports associations, religious organisations and even traditional leadership authorities, actively engage youth volunteers in a broad range of activities aimed at enabling Fijian youth to contribute to the development of their communities, foster participation, civic engagement and active citizenship, while also developing their own skills (Fiji Sun, 2014).

The Problem

Existing studies of Fijian youth participation concentrate in analysing the nature of opportunity structures, spaces/avenues, forms and processes, and their meanings and importance for young people and society (Carling, Reference Carling2009; Craney, Reference Craney2022; Mati & Johnson, Reference Mati and Johnson2016; Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012, Reference Vakaoti2013, Reference Vakaoti2017). These studies conclude that while Fijian youth show willingness to be ‘active citizens’, their levels of participation especially in political affairs are low, and that sometimes, opportunities are inadequate, exploitative (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012, Reference Vakaoti2013, Reference Vakaoti2017), and tokenistic (Carling, Reference Carling2009; Craney, Reference Craney2022).

Nonetheless, a couple of knowledge gaps exist, first, due to limitations arising from low or lack of Indo-Fijian participants in these studies (Mati & Johnson, Reference Mati and Johnson2016; Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2013, Reference Vakaoti2017). In addition, existing studies have not explored questions of how diversity and inclusion (or otherwise) intersecting with existing avenues/types of organisations for youth participation shapes resulting citizenship values. This is a significant gap considering a 2007 nation-wide study which argued that Fiji is historically characterised by inter-ethnic tensions; political instability and violence; an intractable lack of trust across different ethnicities, genders and generations; a general under-representation and low levels of participation (including through volunteering) of the youth, the poor, ethnic minorities, and the less literate members of society in civil society organisations (CSOs); and weak involvement of civil society in non-partisan political action (Khan, Shah & Siwatibau, Reference Khan, Shah and Siwatibau2007: 9). The same report indicated that “even when people of different social groupings are well represented in CSOs, membership is usually segregated” along ethnic, gender, and generational parameters (Khan, Shah & Siwatibau, Reference Khan, Shah and Siwatibau2007: 30). This is partly an enduring legacy of colonial state’s policy of racially segregated development. The same report noted that “while membership is more inclusive, leadership appears to be skewed towards better educated and well-off urban males” with young people largely underrepresented (Khan, Shah & Siwatibau, Reference Khan, Shah and Siwatibau2007: 30). Subsequently, Mati and Johnson (Reference Mati and Johnson2016) note the lack of ethnic diversity in youth participation, even beyond CSOs, emanates from the fact that youth organisations are formed along ethnic or religious identities, and existing opportunities reproduce historic inequalities.

This scenario raises an important question. Specifically, considering these historically segregated CSOs are the institutional and affective agencies imparting citizenship values, what citizenship value subjectivities are bred through volunteerism and other forms of participation in these organisations? This paper sheds light on this question by demonstrating the effect of the nature of existing youth volunteerism opportunities on citizenship values. In doing so, it untangles the ways in which existing forms and practices of associational life shape habits of citizenship with a view to inject a much-needed clarity on the complexities, possibilities, and limitations of volunteerism in fostering civic attitudes and values consistent with progressive citizenship and social cohesion. The paper contributes to understanding this under-researched area and hopefully provide some impetus for research that can inform designs of youth volunteering and participation programmes to ensure progressive citizenship values. The main contribution is that the impact of youth volunteering in building of citizenship values reflects the strength of their diversity and inclusion in participation in the broader Fijian social and civic institutions.

Methodology

The study utilised convergent parallel mixed method approach due to its strengths in integrating qualitative and quantitative philosophical and theoretical thrusts. This enabled the study to contextualise the understandings, multi-level perspectives, and cultural influences and their effects on existing youth volunteering programmes, while also allowing for a quantitative assessment of “magnitude and frequency of constructs” (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Klassen, Plano, Smith and Meissner2011: 4).

The study involved two concurrent surveys and in-depth interviews. One survey was of CSOs in the Fijian youth citizenship industry which sought data on practices and perceptions of impacts on youth citizenship formation. The second survey was of youth participants engaged in volunteering as well as other forms of participation to capture their experiences and perceptions of impacts. Besides gathering demographic information, both survey instruments used checkbox and a limited number of open-ended questions adapted from the CIVICUS Civil Society Index (Mati et al., Reference Mati, Anheier, Hölscher, Fioramonti, List, Holland, Katz, Schall-Emden, Silva and Stares2008) to capture data of interest to the study. The in-depth interviews were conducted with select youth and leaders of civil society organisations in the youth citizenship industry with a view to capturing deeper nuances on the nature of practices and effects of volunteerism and civil society in shaping youth citizenship.

Utilising multi-stage sampling, study participants were drawn from five major urban centres—Suva, Lami, Nausori, Nadi, Lautoka, and Labasa. Rural geographies were deliberately excluded because they are majorly inhabited by single ethnic formations. In addition, young Fijians in urban centres are “less bound by cultural expectations” than those in rural geographies (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2017: 700), suggesting that urban youth offered a better sample for testing patterns of integration or lack thereof, and its effect the nature of resulting citizenship values from volunteerism. Even then, the exclusion of many urban centres (Sigatoka, Ba, Savusavu, Pacific Harbour) purely due to resource limitations, means that the current findings must be read contextually.

Convenience sampling (purposive) was employed in recruiting participants while ensuring a fair ethnic (i.e. I-Taukei, Indo-Fijian, Chinese-Fijian, Mixed (part) and others), and religious (Christian, Hindu, and Muslims) representation. This was informed by 2007 census data which indicated the proportion of I-Taukei and Indo-Fijians to be 56.8 and 37.5% respectively.Footnote 6 Purposive sampling also ensured various categories of youth participation activities (i.e. membership in organisations, volunteering -physical, online and hybrid, as well as donation of money) were captured. Aware that a researcher is as important as the data collection tool in qualitative approaches, the research team included I-Taukei, Indo-Fijians, Chinese Fijians, Mixed youth (post-graduate students at the University of the South Pacific) to assist in researching their own peers and communities.

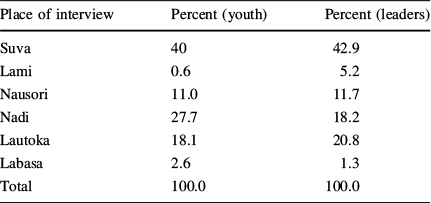

Data collection was done between March and May 2018. A total of 156 youth and 80 youth involving organisations participated in both surveys across six sites as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Distributions of participants across sites (survey data)

Place of interview |

Percent (youth) |

Percent (leaders) |

|---|---|---|

Suva |

40 |

42.9 |

Lami |

0.6 |

5.2 |

Nausori |

11.0 |

11.7 |

Nadi |

27.7 |

18.2 |

Lautoka |

18.1 |

20.8 |

Labasa |

2.6 |

1.3 |

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

For qualitative data, 35 interviews were conducted with youth participants (18–35 years old) and an additional 20 interviews with older (above 35 years) leaders of organisations. Eighteen of the 35 youth interviews were with ordinary members of voluntary associations; while, 17 were leaders. Of the 35 youth participants, 12 were female and 23 were male. All participants (youth and non-youth) had at least a high school qualification, with a majority with at least a bachelor’s degree. The choice of educated youth was informed by the fact that education, alongside, religion and culture significantly influence young people’s involvement in society (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2017). In Fiji, this is even more pertinent as Vakaoti (Reference Vakaoti2017: 700) observes, “institutionalized citizenship education has been introduced in schools in an effort to imbue students with the knowledge, values and attitudes that would make them become better informed, committed and responsible citizens.” However, Vakaoti (Reference Vakaoti2017) urges caution in the way such initiatives are viewed because civic education in schools alone does not work, and that inclusive governance processes are also required if young people are to appreciate their contribution as active citizens. We hold the view that this is possible when social institutions offer opportunities for developing and moulding desired citizenship values (Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017).

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS with the first layer analysis (used in the current paper) being descriptive. Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis techniques (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). Specifically, this was an iterative process involving reading data to ensure familiarity, followed by generating thematic codes. Thereafter, these themes were searched in the data, followed by reviewing of the themes and a final definition made. For the purposes of the current paper, the relevant themes include youth membership in voluntary associations; youth volunteering, and contributions of CSOs and volunteerism to youth citizenship development.

Findings and Discussion

In this section the nature of CSOs in youth citizenship industry are first described, followed by an analysis of the nature and extent of youth engagement (including volunteering) in these organisations. Thereafter, we analyse the social, cultural, economic, and political effects of this engagement, especially volunteerism on youth citizenship values, norms and habits. The next section is a critique that illustrates ‘dark side’ characteristics of existing avenues for youth participation. In the main, these findings illustrate that contributions and impacts of volunteering in building citizenship values reflect the diversity of youth participation in existing civic institutions.

Nature of Existing CSOs and Youth Engagement

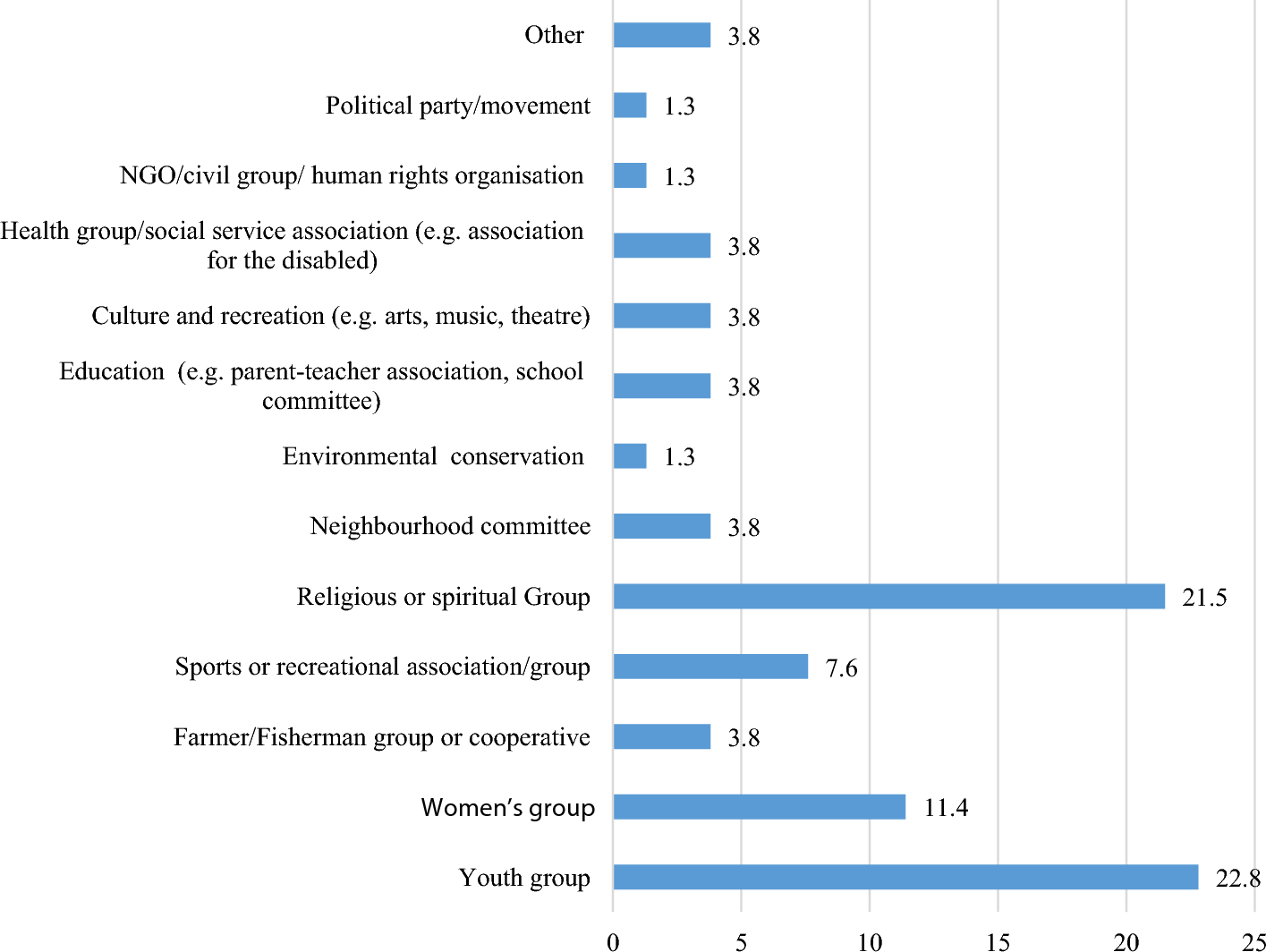

Data on the nature of existing CSOs and youth engagement was sourced through the two surveys. In the organisational survey, participants were asked to identify the type of organisation they lead. Responses were captured using a pre-determined classification developed by CIVICUS Civil Society Index (Mati et al., Reference Mati, Anheier, Hölscher, Fioramonti, List, Holland, Katz, Schall-Emden, Silva and Stares2008). Figure 1 below summarises categories of participant organisations. Worth noting is that the category “youth group” representing 22.8% of organisations in the survey are exclusively associations of young people (in Fijian context, 16–35 year) as opposed to a functional area category.

Fig. 1 Type of organisations (%)

The youth survey asked participants to select the type of organisations they were engaged in, and the type of their engagement. Engagement was conceptualised at three levels: membership, assisting without pay (i.e. volunteering), and donating of money. In the volunteering category, a distinction was made between online and participation in a physical activity. 21.8% of the respondents indicated they were members of voluntary associations. Of these, 5.1% belonged to more than one voluntary organisation; while, 16.7% were members of only one organisation. The same data indicate that Fijian youths are more likely to belong to religious/spiritual organisation than any other type of organisation. 19.2% of the youth belonged to religious/spiritual group, corroborating Vakaoti’s (Reference Vakaoti2017) observations that young Fijians engage mostly in socially sanctioned socio-cultural, traditional, and religious groups.

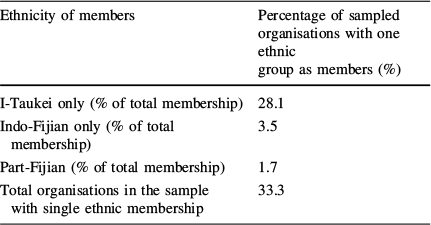

The organisational survey also sought to establish the ethnic composition of members. As shown in Table 2 below, this data revealed that combined, religious organisations, ethnic based groups, neighbourhood associations, and to some extent political parties, account for 33.3% of all surveyed organisations who have single ethic group membership.

Table 2 Organisations with single ethnic members

Ethnicity of members |

Percentage of sampled organisations with one ethnic group as members (%) |

|---|---|

I-Taukei only (% of total membership) |

28.1 |

Indo-Fijian only (% of total membership) |

3.5 |

Part-Fijian (% of total membership) |

1.7 |

Total organisations in the sample with single ethnic membership |

33.3 |

Spatially, membership composition reflects the ethnic diversity (or lack thereof) of the neighbourhoods where they are established and operate, while for religious organisations, this is because religious affiliation runs largely along ethnic lines with most indigenous Fijians being Christian while most Indo-Fijians are Hindu, 20 percent Muslim, and 6 percent Christian (Office of International Religious Freedom, 2023). It follows therefore, that faith-based groups are more likely than other types of organisations to have members from single ethnic groups. This is reflected in write-in responses to a question in the organisational survey which asked why membership was limited to a specific ethnicity. A participant from an I-Taukei only Church indicated “this is a Fijian [I-Taukei] speaking church, so mainly I-Taukei youths participate in this youth group.” Similarly, a participant from a Hindu organisation indicated, “TIV Sangam is only for South Indians of Fiji”; while, a Muslim participant indicated his organisations “is a closed group for only Ahmadiyya Muslim Youths. However, other youths can be part of the programmes if they want to learn Islamic teachings.”

The same qualitative data suggest sociohistorical reasons for dominance in of single ethnicities in these organisations. For example, “when Christianity came into Fiji the I-Taukei were the first ethnic group to convert…it has been passed down from generation to generation (Tevita, interview, 14/03/2018). Such single ethnic/religious group membership in voluntary associations, it has been argued, results in bonding-type social capital which in turn, tends to reinforce exclusive group identities and homogeneity, as well as engendering in-group solidarity while limiting opportunities for out-group members (Davies, 2018; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000).

Interview data also reveal the presence of ethnically heterogeneous groups, especially in within non-governmental organisations (NGOs) consciously bringing members of different ethnicities together and encouraging inter-ethnic diversity and multi-culturalism to break ethnic mistrusts. An example is Citizens’ Constitutional Forum which works on democracy, human rights and multi-culturalism. Tuvaluan Students Association at the University of the South Pacific, whose membership is open to all students at the University of the South Pacific is another example. A number of environment and climate justice focussed organisations such as Project Survival Pacific, New Alliance for Future Generations, Pacific Island Climate Action Network (PICAN), Pacific Urgent Action Hub for climate justice, as are sporting associations, are also in this category. These organisations help engender cosmopolitanism by deliberately “making sure membership is ethnically diverse and gender representative” (Seru, interview 13/03/2018). Such efforts, expose young Fijian to multi-cultural processes and cross-cultural learning even as they contribute to their communities (Tevita, interview, 14/03/2018).

Youth Volunteering

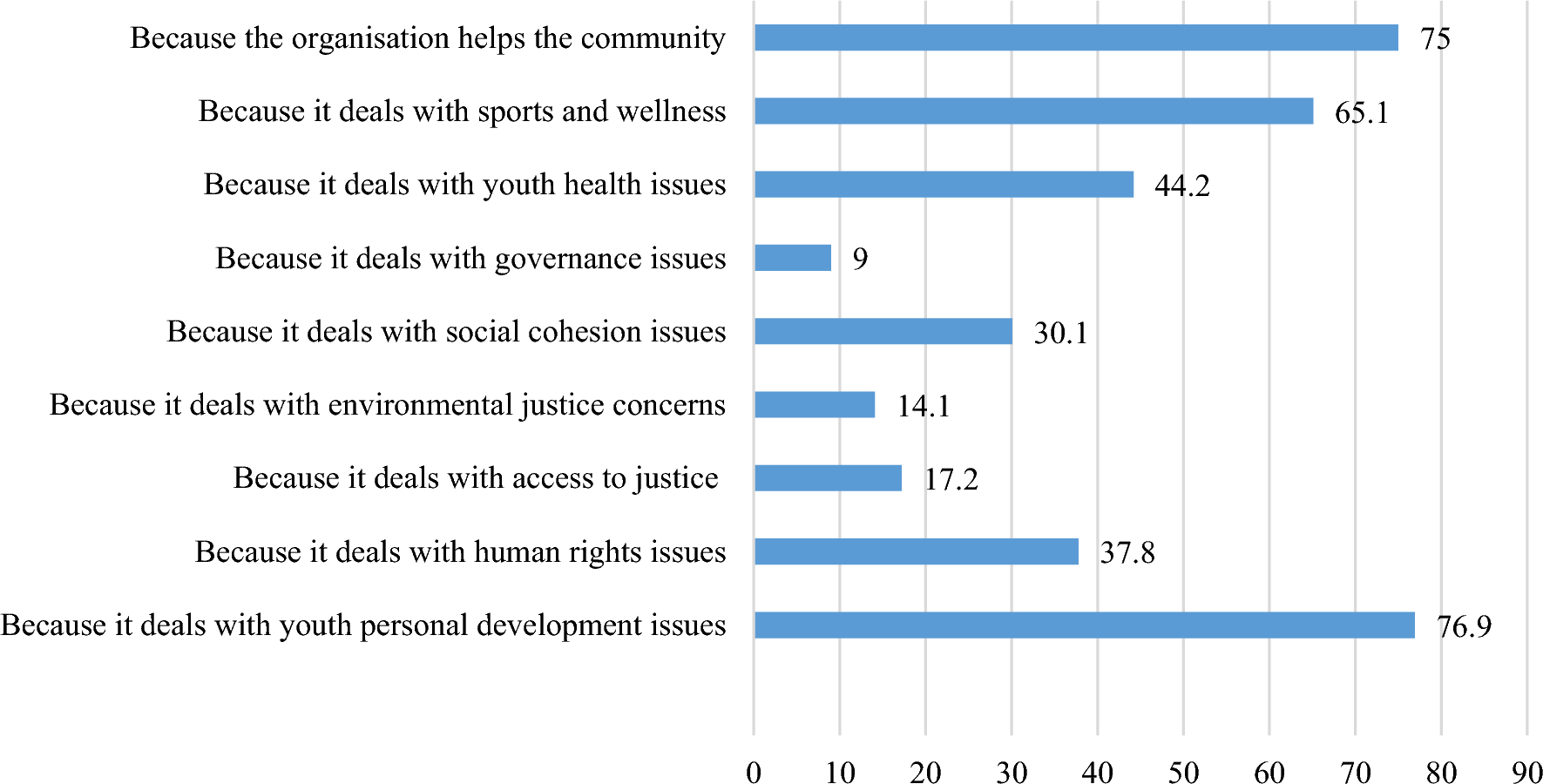

While youth engagement happens through membership activities, it is through volunteering that figures get interesting. 92.3% of the respondents in the youth survey indicated that they had volunteered in one or more organisations. The critical question is what attracts them to volunteer? Secondly, what type of organisations do they volunteer for? Data in Fig. 2 below show that young Fijians volunteer in identified organisations for various reasons.

Fig. 2 Reasons for youth to volunteer in identified organisations (%)

Collectively, these results suggest that young people are attracted to volunteer in programmes that they believe add value or are rewarding to both self and their communities. This is reinforced in qualitative interviews. For example, in responses to the question “what drove you to volunteering” a HIV/AIDS activist who volunteers for several organisations as a peer educator responded: “to fight against the double stigma of discrimination associated with being gay and HIV positive.”

Through volunteering, young Fijians are acting with a sense of responsibility to tackle a myriad of problems in their communities and therefore responding to social dictates of belonging. This is reflected, for example, in State-led programmes such as those cited earlier, as well as in policies such as 2010 Mental Health Decree and 2011 HIV/AIDS Decree which engender volunteering. In turn, volunteer involving organisations and volunteers rely on these policies, while religious institutions rely on socio-religious obligations of “service to society and volunteerism” (Jannif, interview 27/03/2018). These demands shape norms about how young people interact with others, as well as influences development of a sense of social obligation even in other societal contexts. It follows therefore, that young people’s decisions to volunteer are informed not just by individual agentic factors, but also by structural conditioning (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012; Craney, Reference Craney2022; Carling, Reference Carling2009). Given this, Vakaoti (Reference Vakaoti2017: 697) observes that “forms of young [Fijians] engagement although diverse, are dominated by the traditional discourse of … responsibility.”

Like Craney (Reference Craney2022), the current study also unearthed organisations which, though exploiting and benefitting from societal demands and expectations on youth, are also deliberately attempting to provide young people with avenues for overcoming existing structural barriers. These include some political parties and advocacy NGOs. In this regard, a political party youth wing leader indicated that his party has “opened its doors wide to all the youth and people of Fiji […and] the party youth wing is constantly organising sensitisation workshops, creating awareness on political developments in the country” (Sharveen, interview 09/04/2018). In addition, this party “promotes youth volunteerism as a way of imparting necessary political organisation skills.” Similarly, another political party has created a platform for young people to channel their issues to dominant political platforms to ensure their voices are heard.

Nonetheless, such platforms are not without fault. First, “political party youth wings have historically been tokenistic spaces for young people’s participation” (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2017: 700). Indeed, political party youth wings re-energisation witnessed since the first post-2006 coup elections in 2014 (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2017), have been tempered, as we have already seen, by exclusionary activism by one of the parties. At play here is the thorny issue of autochthony in shaping discourses of belonging and exclusion, expectations, rights, privileges, and obligations of Fijian citizenship. It is this contestation around citizenship that has been at the core of Fiji’s four coups since1987 (Kant, Reference Kant and Ratuva2019) as well as advocacy by a major political party around exclusive ethno-political paramountcy of indigenous Fijian population through “rallying I-Taukei youth around indigenous rights” (Kepa, interview 25/04/2018).

Other parties, however, have taken a different approach. A party historically representing interests of Indo-Fijian farmers in the Western division has opened their “youth wing talanoa (forums) to all youth regardless of political affiliations” (Kevin, interview 23/04/2018). This illustrates multi-cultural sensitivity which now ensures that young Fijians from different socio-cultural backgrounds interact in effective ways that shapes their collective identity as Fijian citizens. The President of St. Monica youth community at the Saint Joseph the Worker Catholic Parish in Tamavua (Suva) alluded to this when she said:

We had a concert at Lambert Hall and we tried to incorporate different cultural dances and songs…it was good to see different cultures from around the Pacific come together… they do come because everyone here shares a common interest and a common goal in what we’re trying to achieve as members of different races; it shapes the identity of St. Monica youth (Ahmad, interview 27/04/2018).

Some youth participants indicated that they have been engaged in formal long-term sustained volunteerism where cosmopolitan values are inculcated through local and international exposure. Kevin (interview, 23/04/2018) illustrates this:

I was part of Save the Children initiative called Kids Link Fiji from when I was 12 to 18. Kids Link Fiji is basically a child rights campaign and advocacy initiative. I was also a Fijian delegate to the international members meeting in India for Save the Children.

Such exposures have helped Kevin “grasp how things work, …network, [and…] to positively give back to community” (interview 23/04/2018). In addition, volunteer experiences like “Kids Link Fiji tend to promote certain aspects of tolerance, especially given that most group talks are geared towards tolerance and understanding different perspectives” (Kevin, interview 23/04/2018).

It seems therefore, that bringing youth together through volunteerism offers opportunities for interactions they would otherwise not have. Among others, Lough and Mati (Reference Lough and Mati2012), Mati (Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017), following Tajfel & Turner’s (Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) integrative theory, argue that such direct interactions especially of people from different socio-cultural backgrounds, aids in the development of interpersonal ties and solidarity through making people more comfortable with each other’s differences. The process of how this happens through such interactions is echoed in the word of the President of St. Monica youth community: “sometimes when interacting, we do some things that other people do not like. That is the time we open up. If we do not like something the other person does, we say so and the other party can explain” (Ahmad, interview 27/04/2018). The outcome of such ‘opening up’ and deliberations is a better understanding and toleration of others (Ahmad, interview 27/04/2018). Both bonding and bridging emerge or is strengthened in these situations, with positive outcomes more likely to ensue within interactions that keenly promote cross-cultural understanding, inclusion, learning and incorporating ideas from other cultures, be they local or cross-national (Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017).

On the whole, these findings suggest an active Fijian youth citizenry that challenges a pervasive narrative that contemporary Fijian youth do not seem to care much to volunteer or be actively engaged citizens. Indeed, young Fijians are actively involved in volunteering and participate variously in existing civic organisations, even though majority are most likely to volunteer or participate in organisations where they share a common ethnic or religious identity.

The question then is, how do social transactions in these contexts shape values subjectivities, norms and habits of youth citizenship? Findings of the current study corroborate previous studies that indicated that through these engagements, Fijian youth learn and acquire skills by doing things that require mobilisation, organisation and persuasion skills (Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017). This is especially evident when they volunteer together across ethnic lines. This is captured by words of St. Monica youth President:

As the president of the youth group, I reach out to the youth and involve them in work that is carried out in the community. I try to get them to socialise with people of different backgrounds, do visitations, retreats and even teach them that for those who are unemployed, this could be something that they could do other than sitting at home and relaxing (Ahmad, interview 27/04/2018).

This highlights a positive role that volunteerism can play in helping young people reach across ethnic, socioeconomic, and religious lines, but also how volunteerism is a pathway to securing employment (Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012).

Notwithstanding self-interest motives, youth volunteering benefits communities across the country. Indeed, various communities have latent youth volunteer programmes that are activated especially in disaster situations or whenever there is need. Sharneet, a 26-year-old Indo-Fijian illustrates this:

We have small communities in our own religious communities that we have formed. When anything comes up, we do voluntary work, we go out helping, such as when natural disasters appear or in any other circumstances…we just pop up, mobilise funds and donations and we just go and help people out” (interview 26/04/2018).

Sharneet is also involved in sporting activities and volunteers his time in resource mobilisation for a sporting association. Indeed, sports have generally been powerful in engendering ‘collaborative connections’, and therefore, intergroup integration between Fiji’s two main ethnicities (Sugden, Reference Sugden2017).

For Self and Society: CSOs, Volunteerism and Youth Citizenship Development

From the foregoing, we can conclude that volunteering has multiple benefits for young Fijians but also generates positive outcomes for society, often in ways that are linked to narratives and expectations of progressive citizenship, i.e. one with the right blend of social, cultural, economic, political skills that advance both individual and collective wellbeing. Below, we illustrate and discuss the manifestations of these benefits.

Social Benefits

Relational benefits of volunteering are widely reported in literature on citizenship (c.f. Davies, 2018; Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017; Post-16 2000 citizenship programme, 2000). Specifically, being a part of any voluntary youth association brings with it great benefits such as increased opportunities for social interaction that help build and strengthen networks with other individuals or associations. Such networks help young people to learn, develop personal skills and increase social capital, which can open doors on many other fronts (Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017). The interview excerpt below, suggests this:

In my involvement with [party] Youth Wing, we are constantly surrounded by people of influence in our society. Having those links and being able to sit down and have conversations with them on contradicting opinions enhances my social and networking skills. These skills, I think, are important a bit further down the road (Kevin, interview 23/04/2018).

Cultural Benefits

Literature from Eastern and Southern Africa suggests that cross-cultural interactions in volunteering spaces allows for development of ethno-relative values among volunteers and host communities (Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017). In our case, because of cross-cultural interactions in volunteering spaces, participants “learn something new every day…and understand other cultures better” (Sharveen, interview 09/04/2018). Intergroup interactions happen, sometimes, through simple acts like sharing a meal between members of different cultural groups which enable learning from each other and appreciation of Fiji’s cultural diversity (Interviews: Ahmad, 27/04/2018, Chloe, interview 06/04/2018; Samuela, 24/04/2018). In addition, sports volunteering, as already noted, “expose young Fijians to various cultural groups” (Chloe, interview 06/04/2018). These social contacts and transactions therein, can aid in shifting of “friendship preferences … from almost exclusive preference for in-group members towards increased inclusion of members from out-groups” (Lough & Mati, Reference Lough and Mati2012: 2).

Political Benefits

Engagement in socio-political organisations helps in development of civic literacy and “diplomacy skills, and how to deal with people from various backgrounds” (Sharveen, interview 09/04/2018). By civic literacy we mean “knowledge about community affairs, political issues and the processes whereby citizens effect change” (Flanagan & Faison, Reference Flanagan and Faison2001: 3). Civic literacy aids in development of social tolerance, public spiritedness, participatory attitudes and behaviour, habits of cooperation, respect for others and rule of law and reciprocity—essentially, the ties that bind members of a community together (Brehm & Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Flanagan & Faison, Reference Flanagan and Faison2001; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). For our case, joining a civic organisation or volunteering in a party youth wing activities or even participating in CSO seminars and workshops offer young people “platforms for raising awareness on many issues… learning time management and diplomacy, and doing things in the way they should be done” (Sharveen, interview 09/04/2018). Additionally, “political discourse in such seminars and workshops can be more candid and productive” especially if the environment is youth friendly (Samuela, interview 24/04/2018).

Deliberations that engage young people on contested issues and encourage them to hold autonomous opinions, as reported elsewhere, result in “greater civic knowledge, interest, and exposure to political information (Chaffee & Yang, Reference Chaffee, Yang and Ichilov1990; McLeod, Reference McLeod2000; Niemi & Junn, Reference Niemi and Junn1998), tolerance (Owen & Dennis, Reference Owen and Dennis1987) and ability to see political issues from more than one simple perspective” (Santolupo & Pratt, Reference Santolupo and Pratt1994, in Flanagan & Faison, Reference Flanagan and Faison2001: 3). This is illustrated by several participants, even outside of political volunteering contexts. For example, Ahmad (interview 27/04/2018) the St. Monica Youth President held:

I have learnt to be more open minded, truthful, and honest. So, when I do something, I make sure that I am open, and I express my views so that people know. I encourage them to do the same…people feel they are not alone and there is nothing to hide.

Another youth volunteer in a sporting association indicated:

Volunteering has helped me value inclusiveness and build values such as dignity and integrity and a sense of responsibility. At the same time, volunteering provides hope that if we continue to work together … this can lead to freedom and provision of security and equality in the country (Chloe, interview 06/04/2018).

This confirms that volunteering in multi-cultural contexts is a useful pathway for young people to challenge prejudices and break social divisions (Davies, 2018). In addition, these opportunities help widen awareness of how fates are interlinked (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000). This can be made more prominent by designing programmes with superordinate goals, such as those promoting social inclusion and tolerance among Fijian youth. In this regard, 58.5% of surveyed organisations in the youth citizenship industry indicated knowing at least one such initiative in the country.

Economic Benefits

Volunteering broadens scope of skills such as organisation, confidence, public speaking, and a sense of responsibility, which are beneficial in advancing individual career prospects (Davies, 2018; Mati, Reference Mati, Butcher and Einolf2017). Kepa, an opposition party youth wing leader illustrates this when he said: “when you volunteer, you do not just stay in office …sometimes you go out into the field. This is where you practice your public speaking, using technologies, etc.” (interview 25/04/2018). Another party youth wing leader indicated: “when it comes to politics, the closer you are to the leader and the senior team, your diplomacy skills increase, your public relations skills improve, and you become a vibrant person who has a lot of information that you can use to further your interests” (Sharveen, interview 09/04/2018).

Even outside of politics, volunteering exposes young Fijians to a number of opportunities that advance their skills set, education, and careers. This is reflected by Chloe who volunteers for a sports association when she argued:

Being a part of the […] Association has helped me personally develop my skills on court that enable me to teach in the [sport] development program…It has helped me gain experience in physiotherapy; I am a fourth-year physiotherapy student at Fiji School of Medicine … I volunteer at the Fiji Games as a physiotherapist and the Fiji Secondary Schools Tournament to better my training and skills (interview 06/04/2018).

Overall, these experiences as reported elsewhere, are enablers of individual spatial mobility, while skills gained increase employability potential (Davies, 2018) or opportunities for self-advancement, be it economically or in politics. Consequently, as Vakaoti (Reference Vakaoti2012: 6) notes, “youth volunteering has shifted; it is no longer [just] about the spirit of free giving but is fast becoming a means to an end.” It is a shift that benefits individual youth volunteers while simultaneously imparting citizenship values that benefit winder Fijian society.

Dark Side of Volunteerism?

Does youth volunteering always lead to positive citizenship values? Evidence from the current study call for the need for a nuanced reading the contributions of volunteering, as it is not always associated with positive and prosocial civic outcomes. Forms, environments, and institutional setups for volunteering, need to be understood for their positive or negative connotations on a case-by-case basis and assessed against how inclusive they are, and what sort of society they profess (and practise) to promote. Specifically, even with all the positive outcomes of volunteerism, there are still elements of ethnic intolerance in Fiji (De Vries, Reference De Vries2002; Office of International Religious Freedom, 2023). These are perpetuated through pervasive bonding-type social transactions especially seen through “blogs on social media [where] you actually see discrimination and prejudice still happens” (Paulasi, interview 18/04/2018). The existence of a political party perceived to advocate exclusionary rights of indigenous Fijians, even while coached in the language of indigenous people’s rights, adds to this conclusion. In addition, there exists groups (especially in the cyberspace) that harbour extremist views about people of other faiths or ethnicities and propagate hate against them. Singled here are some “political and faith groups with high intolerance” (Deo, interview 18/04/2018).

Though a minority (only 9% of organisation survey participants indicated there were “groups that are explicitly promoting racist, discriminatory or intolerant behaviour”), actions of such groups and individuals, as one sports association youth leader observed, “can bring about chaos in Fiji’s multi-cultural environment” (Ravi, interview 01/04/2018). This is not a far-fetched fear given the history of ethnic animosity against Indo-Fijians, which, for example, in May 2000, culminated to the overthrowal of a multi-ethnic coalition government led by the first ever Indo-Fijian Prime Minister Mahendra Choudhry. This was followed by widespread looting of Indo-Fijian owned businesses in the capital (Lal & Preters, 2001Reference Lal and Pretes2008).

In more contemporary times, the implosion of SODELPA party after the appointment of Vijay Singh as the party’s first ever Indo-Fijian vice-president is cited as evidence for deep-seated ethnic fissures in Fiji (Chanel, Reference Chanel2020). These ethnic divides emanate from the fact that historically, strong and enduring social institutions in Fiji are ethnically and religiously exclusive/segregated (Mati & Johnson, Reference Mati and Johnson2016; Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012; Khan, Shah & Siwatibau, Reference Khan, Shah and Siwatibau2007). Indeed, as we saw earlier, a third of participants in organisational survey exhibit this trait. This ethnicized institutional culture is exhibited in some national level youth organisations such as the National Youth Council, and Youth Parliament, which has resulted in their dysfunctionality due to exclusion of Indo-Fijian youth (Interviews: Sharveen, 09/04/2018; Waqatabu, 14/03/2018). In National Youth Council, where 90% of leadership is iTaukei for example, attempts by Indo-Fijian Youth to come to this space led to a “big commotion” (Waqatabu, interview 14/03/2018).

Two plausible explanations account for the intransigence of ethnicized institutional culture. First is the impact of the military’s presence in government and politics which has framed, determined, and limited the space and scope for civil society landscape, but also implanted deep fear among Fijians. To contextualise this, Mudaliar (Reference Mudaliar2020: iii) notes the existence of a constant conflict between two alternative ‘nations-of-intent’ formations in Fiji: “an ethnic communal nation-of-intent–which views Fiji as made up of different communal groups—and a civic egalitarian nation-of-intent that believes the nation should be founded on principles of equality.” This conflict has been evident throughout Fiji’s ‘coup period’ with the military taking sides in either championing indigenous Fijian ‘paramountcy’ (Rabuka’s two coups in 1987, and the George Speight’s 2000 where “comments like you get rid of them, kill the Indians, kill the non-Christian” were made (Vivian, interview, 02/05/2018)), or challenging the same in favour of civic nationalism (Bainimara’s 2006 coup). These coups come with deepening authoritarianism (Mudaliar, Reference Mudaliar2020).

Second, the rigid hierarchies of power in Fijian culture which dictate youth passivity, and respect for traditional chiefs, elders, culture and traditions, has enculturated young people to occupy a subordinated position and arrested transformative ideas (Craney, Reference Craney2022; Vakaoti, Reference Vakaoti2012). Here, “young people are not encouraged to be outspoken or to ask questions; their role is to learn from observation and example, and to do as they are instructed (Craney, Reference Craney2022: 24). The result of this, an opposition political party youth wing leader indicated, “is a nonchalant attitude towards politics of change especially among young people” (Kevin, interview 23/04/2018). Young people’s general apathy to institutional political processes is also a product of limited formal education, unemployment, gender prejudice and other manifestations of social inequality among Fijian youth (Interviews: Chloe, 06/04/2018; Ahmad, 27/04/2018; Kepa, 25/04/2018; Sharneet, 26/04/2018).

Exclusion is further exacerbated by “dysfunctionality and lack of clear structures targeting young people in majority of existing youth development programmes” (Interviews: Sharneet, 26/04/2018; Marika senior, 26/02/2018). An example is the disconnect between those invited to spaces of policy dialogue and articulating issues, and those affected by these issues. As observed by a party youth leader, “most of the time, the people talking in forums are not the ones facing the issues. They [organisations] do not go down to those affected” (Kepa, interview 25/04/2018). Similar sentiments are reported by Craney (Reference Craney2022: 116) who observes that in the Youth Parliament, youth representatives are often not young themselves and are often very “disconnected from current trends and issues affecting youth but holding on to the position of influence they have obtained.”

Conclusion

This study has illustrated that on the main, existing forms and avenues of youth engagement contributes to shaping progressive citizenship values among young Fijians. However, there exists groups and practices that temper this by propagating exclusionary group rights and goals. The implication is that rightly imagined, and inclusivity orientated youth volunteer programmes and civic associations, result in bridging social capital and progressive citizenship values. On the other hand, volunteerism practiced through organisational models dominated by bonding-type social capital could lead to exclusionary citizenship, social disparities and patterns of discrimination and privilege (Obadare, Reference Obadare2011; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

The outcome of volunteerism, therefore, are socially situated and dependent on among others, the nature of the actually existing civic institutions, the balance of power among diverse groups constituting it, and the role of the state in framing, determining, enabling or constraining the freedoms and space for participation and the scope of allowable activities within civic landscape. This means that the nature and character of Fiji’s multi-ethnic society must be factored in designs of volunteering programmes if they are to have positive citizenship effects on young Fijians. While the focus on this study was not in investigating such designs, future research should help us better understand institutional designs of volunteerism and civil society, among other social institutions, that can aid in engendering positive youth citizenship value.

We argue that this is possible especially after the 2022 elections which saw a multi-ethnic coalition democratically seize power from FijiFirst Party. The fact that the three members of pro-I-Taukei party (SODELPA) are part of this broad multi-ethnic coalition in power, provides an opportunity for recasting political and other social institutions towards transmitting multi-culturalism and other progressive values and attitudes that can unite young Fijians towards a common cause and identity, in a civic and egalitarian nation-of-intent.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

I declare that I do not have any conflict-of-interest issues in this project and manuscript.

Ethical approval

The project whose data are used in the current paper was granted ethics clearance by the University of the South Pacific Ethics Committee on July 10, 2017. The study was conducted in adherence to all research ethics principles. Names of participants in the manuscript are pseudonyms.