Introduction

In an earlier paper (Langer, Reference Langer2019), I reviewed some of our research on controlled delivery systems for macromolecules. This included the development of the first approaches to deliver nucleic acids from tiny particles (e.g., micro- and nanoparticles) (Langer and Folkman, Reference Langer and Folkman1976; Ball, Reference Ball1999; Conde et al., Reference Conde2023). This research challenged conventional wisdom at the time (the 1970s) and was greeted with great skepticism. The consequence was that my first nine research grants were rejected, and no chemical engineering department (my major department) would hire me for an assistant professor position. When I finally did get a faculty position in a Nutrition Department, many senior faculty ridiculed my concepts for drug delivery and suggested I look for a new job (Langer, Reference Langer2019, Reference Langer2025). However, over time, this skepticism helped me get patents (it certainly showed our findings were not obvious) leading to the development of controlled release systems that have saved and improved the lives of millions (Langer, Reference Langer2019, Reference Langer2025). Our lab also developed mathematical models to predict and help understand controlled release mechanisms, synthesized numerous new lipids and polymers, discovered ways to externally regulate molecular transport from materials, and created new approaches to deliver molecules through different routes in the body – oral, skin, lung, and others. We also developed new drug delivery systems including work with the Gates Foundation to invent systems for vaccine delivery, pharmaceuticals, and vital nutrients to the developing world. The QRB Editor-in-Chief asked if I would provide an update since that original paper was published (Langer, Reference Langer2019) and I am honored to do so. This update (see also Figure 1) is provided below.

Figure 1. Timeline of some drug delivery milestones from 2019 to present. For a timeline up to this point, see Langer (Reference Langer2019).

New in vitro methods for developing oral drug delivery systems

For over 40 years, monolayers of cancer-derived cell lines (e.g., Caco 2 cells) have been the standard method for studying gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of molecules and have been widely used as a tool for oral drug development. However, they display mixed in vivo predictability. With my MIT colleague Gio Traverso, who was a former fellow in my lab, we recently developed approaches to cultivate GI tissue and enable it to function ex vivo for long periods. We then created an automated robotic high-throughput system of whole segments of the GI tract (Figure 2). This GI Tract-Tissues Robotic Interface System (GI-TRIS) showed excellent predictive capacity for human oral drug absorption (Spearman correlation coefficient of .906 vs. .302 for Caco-2 cell-based systems) and enabled several thousand samples to be tested daily in an automated robotic entity. We studied the intestinal absorption of almost 3,000 formulations with the model peptide drug oxytocin and discovered an enhancer that showed a nearly 12-fold increase in oral bioavailability of oxytocin in vivo in large animals without intestinal tissue damage (von Erlach et al., Reference Von Erlach2020). It is our hope that the GI-TRIS system will transform oral drug formulation development and that GI-TRIS or systems like it become a preclinical approach for improving drug delivery for different applications. We recently developed a related type of in vitro system for brain studies (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton2025). These types of approaches may become increasingly important given the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s recent emphasis on in vitro models, as opposed to animal models, for use in drug development (FDA.gov, 2025).

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical analysis of sections of gastrointestinal tissue that were incubated for 7 days ex vivo or freshly isolated. Brown indicates the antibody signal, while blue is the counterstain. Adapted from Von Erlach et al. (Reference Von Erlach2020).

Artificial intelligence/machine learning and drug delivery

We have been exploring artificial intelligence/machine learning as it relates to drug delivery ever since I co-founded Transform Pharmaceuticals (subsequently acquired by Johnson and Johnson) in 1999 (New Technology, n.d.). In this case, we generated large amounts of data using the high-throughput systems we developed at that time and used the data predictions to enable insoluble drugs to be soluble enough to become bioavailable in vivo. More recently, we examined inactive ingredients and generally recognized as safe GRAS compounds which are considered by the FDA as safe for human consumption within specific dose ranges. However, many inactive ingredients can have unknown effects at these concentrations and alter treatment outcomes. To accelerate such discoveries, we used machine learning to examine unknown effects of inactive ingredients, focusing on P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase-2B7 (UGT2B7), two proteins that effect the pharmacokinetics of about 20% of FDA-approved drugs. We identified vitamin A palmitate and abietic acid as inhibitors of P-gp and UGT2B7. In vitro, in silico, ex vivo, and in vivo studies validated these findings. These kinds of studies have the potential to elucidate biological effects on food- and excipient-drug interactions when developing drug formulations (Reker et al., Reference Reker2020).

In another study, with my former postdoctoral fellow Dan Anderson, we used combinational chemistry coupled with machine learning approaches to identify new ionizable lipids for mRNA delivery in lipid nanoparticles. We started with a four-component reaction platform and created a library of nearly 600 ionizable lipids. We then tested mRNA transfection potencies of lipid nanoparticles containing those lipids and used the results as an initial data set for training different machine learning models. We selected the best-performing model to examine a virtual library of over 40,000 lipids, synthesizing and then experimentally evaluating the top 16 lipids we identified. We discovered a specific lipid which performed better than established benchmark lipids in transfecting muscle and immune cells in a number of tissues. This approach should facilitate the creation and evaluation of ionizable lipid libraries and also advance the development of lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery (Li et al., Reference Li2024).

In an additional study, we introduced neural networks as a deep-learning strategy for ionizable lipid design. We created a data set of >9,000 lipid nanoparticle activity measurements and used it to train a directed message-passing neural network for prediction of nucleic acid delivery with different lipid structures. Lipid optimization using neural networks predicted RNA delivery in vitro and in vivo and extrapolated to structures different from the training set. We examined over one million lipids in silico and identified two optimal structures, with local mRNA delivery to the mouse muscle and nasal mucosa. One of these was equivalent to the best existing structures for nebulized mRNA delivery to mouse lungs, and both efficiently delivered mRNA to ferret lungs (Witten et al., Reference Witten2024).

New delivery systems

For over 100 years, chemotherapy dosing has been calculated according to the weight and/or height of the patient or equations derived from these, such as body surface area (BSA). However, such calculations do not account for intra- and interindividual pharmacokinetic variations, which can lead to enormous variations in systemic chemotherapy levels and cause under- or overdosing of patients. To address these issues, we designed and developed a closed-loop drug delivery system that dynamically adjusts its infusion rate to patients so as to reach and maintain the drug’s target concentration, regardless of a patient’s pharmacokinetics (PK). With our student Louis DeRidder and Gio Traverso, we developed a closed-loop automated drug infusion regulator (CLAUDIA) that can control the concentration of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in rabbits according to a range of concentration-time profiles, which could be useful in chronomodulated chemotherapy, and over a range of PK conditions that mimic the PK variability observed clinically. In one set of experiments, conventional BSA-based dosing resulted in a concentration seven times above the target range, while CLAUDIA keeps the concentration of 5-FU in or near the targeted range (DeRidder et al., Reference DeRidder2024). We also showed that CLAUDIA is cost effective compared to BSA-based dosing and believe that CLAUDIA or systems like it could someday be translated to the clinic to enable physicians to better control chemotherapy plasma concentration and significantly improve safety and efficacy.

In addition, one Holy Grail is oral delivery of macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. This is due to their poor absorption and rapid enzymatic degradation in the gastrointestinal tract. We previously developed a way to accomplish this with a self-oriented oral injectable system (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson2019). Building on that, we recently developed an orally dosed liquid auto-injector capable of delivering up to 4-mg doses of bioavailable drugs which displayed the rapid pK of an injection, reaching an absolute bioavailability of up to 80% and a maximum plasma drug concentration within 30 min after dosing. This approach improves dosing efficiencies and pK an order of magnitude over our previously designed capsules and up to two orders of magnitude over clinically available and preclinical chemical permeation enhancement technologies (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson2021).

In another example, administering medicines to 0- to 5-year-old children in a resource-limited environment, for example, the developing world, requires dosage forms that circumvent swallowing solids; avoid on-field reconstitution; are thermostable, cheap, and versatile; and can mask taste. To solve this problem, and since many drugs lack adequate water solubility, we introduced oils, whose textures could be modified with gelling agents to form ‘oleogels’. We showed that the oleogels can be formulated to be as fluid as thickened beverages and as stiff as yogurt puddings. In swine, oleogels could successfully deliver four drugs ranging three orders of magnitude in their water solubilities and two orders of magnitude in their partition coefficients. Oleogels could be stabilized at 40 °C for long time periods, a few weeks, and used without redispersion. In addition, we developed a macrofluidic system enabling fixed and metered dosing (Kirtane et al., Reference Kirtane2021). We expect that these oleogels could be adopted for pediatric dosing, palliative care, and gastrointestinal disease applications. We believe such delivery systems are particularly important for young children because, on average, over 50 percent of parents have children who are unable to swallow a tablet or capsule (Patel et al., Reference Patel2015) and the age at which children can swallow tablets or capsules varies significantly, but is generally age 7 (Zajicek et al., Reference Zajicek2013).

Furthermore, pills are a cornerstone of medicine but can be challenging to swallow. While liquid formulations are easier to ingest, they are not able to localize therapeutics with excipients nor can they act as controlled release systems. We recently developed oral drug formulations based on liquid in situ-forming tough (LIFT) hydrogels that combine the advantages of solid and liquid dosage forms. These hydrogels form directly in the stomach through ingestion of a crosslinker solution of calcium and dithiol crosslinkers, followed by a drug-containing polymer solution of alginate and four-arm poly(ethylene glycol)-maleimide. We showed that LIFT hydrogels form in the stomachs of live rats and pigs and are mechanically tough, biocompatible, and safely cleared after 24 hours. LIFT hydrogels delivered a total drug dose comparable to unencapsulated drug and did so in a controlled manner. They also protected encapsulated therapeutic enzymes from gastric acid-mediated deactivation (Liu et al., Reference Liu2024).

We also developed delivery systems for gases. In particular, low concentrations of carbon monoxide (CO) have shown benefit in animal models, but safe delivery of appropriate doses has been challenging. Inspired by molecular gastronomy. With Drs. Traverso and Byrne, we designed gas-entrapping materials (GEMs) using materials generally recognized as safe. These include xanthan gum, methylcellulose, maltodextrin, and corn syrup. Solid, hydrogel, and foam GEMs containing CO were able to deliver different concentrations of the gas to healthy animals through noninhaled routes. In models of colitis, acetaminophen overdose, and radiation-induced proctitis, rectally administered foam GEMs reduced tissue injury and inflammation (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne2022).

Finally, food fortification is an effective strategy to address vitamin A deficiency, which is the leading cause of childhood blindness and drastically increases mortality from severe infections especially in the developing world. However, vitamin A food fortification remains challenging due to significant degradation during storage and cooking. With my MIT colleague Ana Jaklenec, who was a postdoc in my lab, we created an FDA-approved, thermostable, basic methacrylate copolymer (BMC) system to encapsulate and stabilize vitamin A in microparticles (MPs). To achieve this, we examined numerous molecules, but BMC is pH responsive, so we hypothesized it would not degrade at near neutral pH, but would dissolve at the lower pH of the stomach, thereby releasing its contents. Encapsulation of vitamin A in -BMC MPs greatly improved stability during simulated cooking conditions and long-term storage. For example, vitamin A absorption was nine times greater from cooked MPs than from cooked free vitamin A in animals. In a randomized controlled cross-over study in healthy premenopausal women, vitamin A was released almost immediately from MPs after eating and had a similar absorption profile to free vitamin A (Tang et al., Reference Tang2022). This encapsulation material has now been approved by Codex Alimentary, and we believe that this system could be introduced in Africa in the coming years to provide global food fortification strategies toward eliminating vitamin A deficiency and could save tens of thousands of children’s lives (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson2024).

New approaches for nucleic acid delivery

Multiple myeloma, a cancer that preferentially colonizes the bone marrow, is a terrible disease. It has been suggested that endothelial cells within the bone marrow microenvironment play a critical role. Specifically, cyclophilin A, a homing factor secreted by bone marrow cells (BMECs), is key to multiple myeloma homing, progression, survival, and chemotherapeutic resistance. Thus, inhibition of cyclophilin A provides a potential strategy to simultaneously inhibit multiple myeloma progression and sensitize multiple myeloma to chemotherapeutics and could improve the therapeutic response. However, inhibiting factors from the bone marrow endothelium is challenging due to delivery barriers. We combined both RNA interference (RNAi) and lipid-polymer nanoparticles to develop a nanoparticle platform for small interfering RNA (siRNA) delivery to bone marrow endothelium, and we showed that this inhibits cyclophilin A in BMECs, preventing multiple myeloma cell extravasation in vitro. In addition, we showed that siRNA-based silencing of cyclophilin A in a murine xenograft model of multiple myeloma, either alone or in combination with bortezomib, an FDA-approved multiple myeloma therapeutic, reduces tumor burden and extends survival. This nanoparticle platform may provide a broadly enabling technology to delivery nucleic acid therapies to other malignancies that home to bone marrow (Guimarães et al., Reference Guimarães2023).

In addition, the expanding applications of nonviral genomic medicines in the lung remain restricted by delivery challenges. To address this issue, with Dan Anderson, we synthesized and studied a combinatorial library of biodegradable ionizable lipids to create inhalable delivery vehicles for messenger RNA and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editors. The best nanoparticles given by repeat intratracheal dosing could achieve efficient gene editing in lung epithelium, providing avenues for siRNA gene therapy of genetic lung diseases. In addition, lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations were stabilized to resist nebulization-induced aggregation by changing the nebulization buffer to increase the LNP charge during nebulization and by the addition of a branched polymeric excipient. Finally, we synthesized a combinatorial library of ionizable, degradable lipids using reductive amination, and evaluated their delivery potential. The combination of ionizable lipid, charge-stabilized formulation, and stability-enhancing excipient yielded a major improvement in lung mRNA delivery over current state-of-the-art large nanoparticles and polymeric nanoparticles (Li et al., Reference Li2023).

Finally, working with my MIT colleague Phil Sharp and our postdoctoral fellow Vikash Chauhan, we developed an approach to significantly minimize indel errors resulting from gene editing. Prime editors make programmed genome modifications by writing new sequences into extensions of nicked DNA 3′ ends. These edited 3′ new strands must displace competing 5′ strands to install edits, yet a bias toward retaining the competing 5′ strands hinders efficiency and can cause indel errors. We discovered that nicked end degradation, consistent with competing 5′ strand destabilization, can be promoted by Cas9-nickase mutations that relax nick positioning. We used this concept to develop prime editors with very low indel errors. Combining this error-suppressing strategy with the latest efficiency-boosting architecture, we developed a next-generation prime editor. Relative to previous editors, our editor had similar efficiency but up to 60-fold lower indel errors and enabled edit:indel ratios as high as over 500:1 (Chauhan et al., Reference Chauhan2025).

A powerful example: Drug delivery nanoparticles

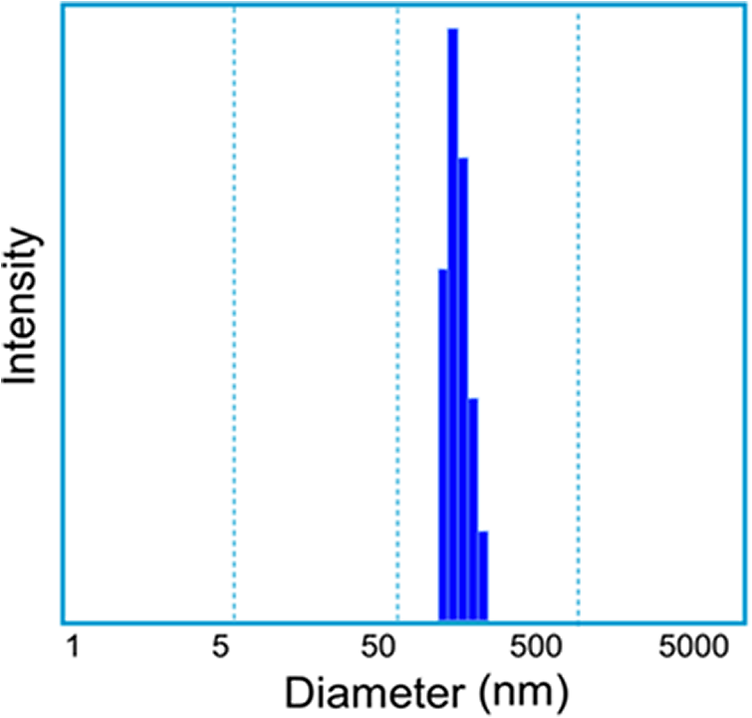

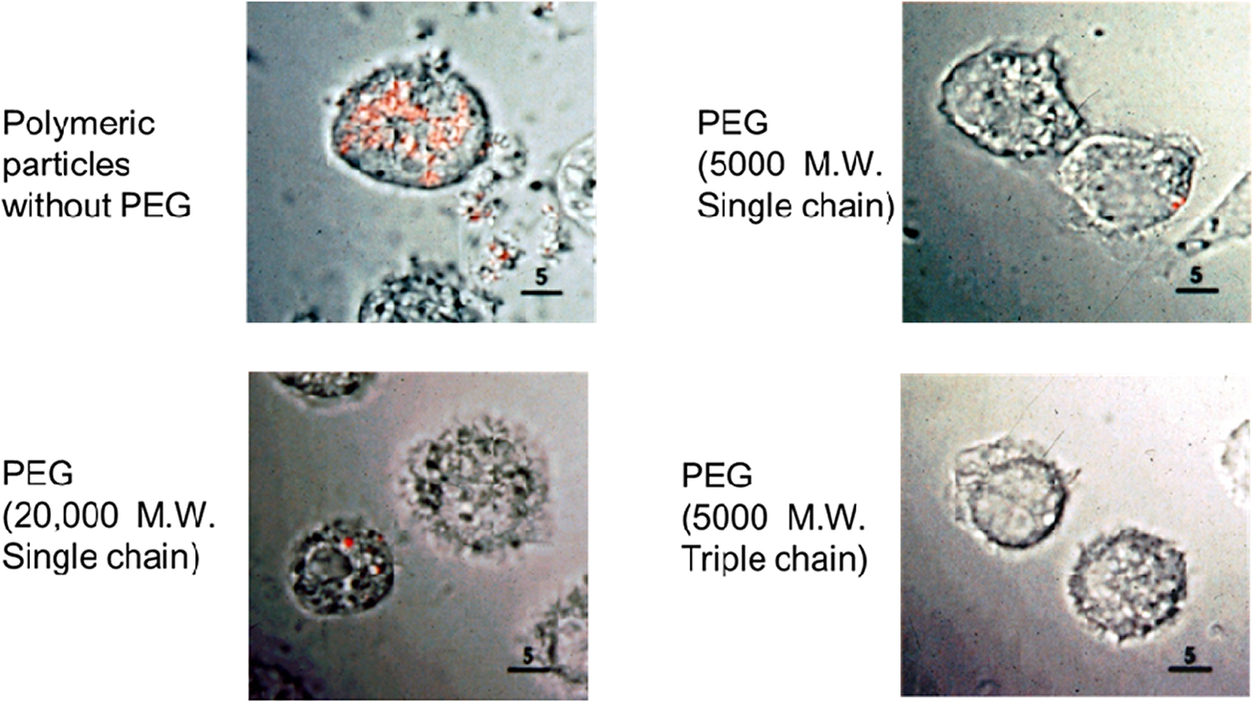

I wish that the early work we did was a cure-all for delivery systems; it hardly was. One of the things I and others would notice is when one makes nanoparticles and injects them, they can aggregate and stick together. In addition, macrophages tend to engulf them. So we and others including Vladimir Torchilin came up with special nanoparticle coatings using polyethylene glycol (PEG) which is actually in MiraLAX and is FDA approved. We published a paper over 30 years ago where we put forth seven key criteria to address the potential success of therapeutic nanoparticles and then synthesized them (Gref et al., Reference Gref1994). That they are nanoparticles can be noted with atomic force microscopy (Figure 3) or with quasi-elastic light scattering (Figure 4). In in vitro experiments with macrophages, we put an orange dye in the nanoparticles, and if they do not have the PEG, they are engulfed by macrophages within an hour. However, when one uses PEG, many fewer orange dots and sometimes none are seen inside cells (Figure 5). Omid Farokhzad, when he was a fellow in our lab, attached targeting molecules to the nanoparticles, so we could target specific cells (Farokhzad et al., Reference Farokhzad2006). All of these features are important in that this could enable the delivery of large molecules like siRNA and mRNA by protecting them from being destroyed and delivering them in an unaltered form to patients.

Figure 3. Images of nanospheres taken with an atomic force microscope. PEG-PLGA nanospheres (MW of PEG, 5KD; MW of PLGA, 45 kD; molar ratio lactic acid; glycolic acid in PLGA, 75:25). The nanospheres were prepared from diblock PLGA- PEG copolymers (Gref et al., Reference Gref1994).

Figure 4. Quasi-electric light scattering of PEG-PLGA nanospheres showing size distribution (mean diameter of 140 nm) (from Gref et al., Reference Gref1994).

As the core of our delivery platform, we examined both polymers and lipids. In the case of lipid nanoparticles, there are generally four components: cholesterol, a ‘PEG lipid’, a structural lipid, and an ionizable lipid. In the 1980s, a company called Vical started using cationic materials, specifically cationic lipids, to complex nucleic acids (Felgner et al., Reference Felgner1987). This was also be done by Wu with cationic polymers (Wu and Wu, Reference Wu and Wu1987). These approaches enabled the nanoparticles to form containing the nucleic acid, but it also caused potential problems, such as complement activation, toxicity, and in addition once the particles are taken up by a cell, it is difficult for the nucleic acids to get out of the endosome. To address this, Dan Pack and Dave Putnam in our lab designed nanoparticles with ionizable cationic molecules (Pack et al., Reference Pack2000; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam2001) as did Semple et al. (Reference Semple2001). In this case, the molecule initially bears a neutral charge, but then because of its pKa, when it enters the endosome, it becomes charged, and whatever is inside the nanoparticle gets out of the endosome. However, because it is uncharged at physiologic pH, it should not cause toxicity or complement activation. While ionizable molecules and ionizable lipids had previously been synthesized and used to study membrane fusion (Bailey and Cullis, Reference Bailey and Cullis1994), Pack et al. (Reference Pack2000) and Putnam et al. (Reference Putnam2001) and Semple et al. (Reference Semple2001) showed that ionizable molecules could be effective for drug delivery. A next question is ‘What should your ionizable lipid be?’ In this case, Dan Anderson began using combinatorial synthesis techniques that he and Dave Lynn developed in our lab (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson2003) and made hundreds of lipids (Akinc et al., Reference Akinc2008; Love et al., Reference Love2010). Alnylam, a company for which I was on the founding Scientific Advisory Board, and Akin Akinc, one of my students who worked there, led a lot of the work which would ultimately lead to the development of Onpattro, the first siRNA molecule approved by the FDA.

Founding Moderna and developing mRNA COVID-19 vaccine

We also worked on the delivery of messenger RNA. In 2010, Derrick Rossi, who was a professor at Harvard, visited me. Like some others, he had tried to get funds to start a company on messenger RNA therapies, but Third Rock Ventures and other companies said things like, ‘it’s never going to work’. So when Derrick came to see me, I thought to myself there were two pieces to messenger RNA therapies. One is the mRNA. Here, the pioneering work of Karikó and Weisman (Karikó et al., Reference Karikó2005) to modify it safely was critical. But the other piece is the delivery system. If you cannot protect mRNA and deliver it to the patient, it could never work. In fact, no large pharmaceutical company started doing anything significant on mRNA until Pfizer in 2018. Based on the work I discussed above, there were six reasons why I thought that we could address the delivery problem: first, we showed for the first time that one can deliver large molecular weight molecules including nucleic acids drugs even though others said it was not possible (Langer and Folkman, Reference Langer and Folkman1976; Ball, Reference Ball1999; Langer, Reference Langer2019; Conde et al., Reference Conde2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu2023); second, we showed that tiny particles made of either polymers (Preis and Langer, Reference Preis and Langer1979) or lipids (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen1991) could be used effectively for vaccine delivery; third were the PEG coatings; fourth was the ionizable molecule concept; fifth was the approach of having numerous lipids (Akinc et al., Reference Akinc2008; Love et al., Reference Love2010); and sixth, we had developed microfluidic approaches to make nanoparticle drug delivery systems (Karnik et al., Reference Karnik2008), which is something that, at least to me as an engineer, seemed like it could someday be scalable. So, with Derrick, Noubar Afeyan, and Ken Chien, we started Moderna in 2010. By that time, protein therapeutics had become very important clinically, with over 10 of the top selling pharmaceuticals being proteins. However, it takes a long time to make them, and it is expensive. For example, you have to use eggs if you are trying to make a flu vaccine. You generally have to start a year in advance and guess as to the precise virus strain. That is one of the reasons why flu vaccines are often only 40%–50% effective – because one is guessing. However, with messenger RNA, one would not have to guess and start so early. One could just make the mRNA and protect it with nanoparticles, inject it, and then the patient’s body would do all the work. One might also be able to treat diseases that could not be treated previously – like creating missing intracellular or membrane-bound proteins. We started Moderna in 2010.

By 2019, Moderna had 13 products in human clinical trials, eight of which were vaccines. Then, COVID-19 entered the picture. Chinese scientists published the virus genetic sequence on January 11, 2020. It took just 2 days for the Moderna scientists to design the vaccine. Then, it was put in the nanoparticles and sent to our clinical partners at NIH for testing. The first patients were dosed in March, just 2 months later. In a phase 3 trial, there were 30,000 patients: 15,000 treated and 15,000 controls. Of the 15,000 people who were treated, not a single person died, not a single person went to the hospital, and it was over 94% effective (Baden, Reference Baden2020). It has now been used all over the world. BioNtech, a German company, also successfully used messenger RNA in nanoparticles. There are many papers that have been published on these clinical trials showing that the vaccines are extremely safe and effective (see, e.g., Harris et al., Reference Harris2023, Semenzato et al., Reference Semenzato2025). Yet, any medicine or vaccine can lead to side effects. However, nearly every health agency in the world states that vaccines are the most effective public health approach in history. There have also been many studies looking at the safety of the Moderna vaccine and the BioNTech-Pfizer vaccine. Such studies show that if you compare the mRNA vaccine side effects to ones you get with a standard flu vaccine, the mRNA vaccine has fewer side effects (Kim et al., Reference Kim2022).

In terms of efficacy with COVID vaccines in the United States, as of March 2023, there were 49 failed vaccines and two approved by FDA, those by Moderna and BioNTech-Pfizer; there have been 209 failed treatments and one approved. Entities like the Commonwealth Fund have done analyses of what happens in terms of death and the economy in the United States. They found that over an 18-month period, mRNA vaccines prevented 3 million deaths, over 18 million hospitalizations, almost 120,000 COVID infections, and saved over a trillion dollars (Fitzpatrick and Moghadas, Reference Fitzpatrick and Moghadas2022). Lancet has estimated that over 20 million lives have been saved by COVID vaccines (Watson et al., Reference Watson2022).

As we look to the future, the work on COVID vaccines may open the door for personalized cancer vaccines or individualized neoantigen therapies (INT). For example, Moderna and Merck have been treating people who have advanced melanoma. In this case, one can take up to 34 mutations known as neoepitopes that are present in a patient’s cancer cells and then incorporate the neoepitopes into the mRNA vaccine the same way it was done with the COVID vaccine. Then you put it in nanoparticles. The vaccine was used in conjunction with Keytruda, a leading immunotherapy drug. In a double-blind clinical trial with 157 patients, about half the patients got Keytruda and half got Keytruda plus INT, and at 2 years, the risk of recurrence or death was reduced by 44%; at 3 years, 49% (Khattak et al., Reference Khattak2023). The patients were injected 9 times over a 27-week period. One might someday envision a single injection using the self-boosting vaccine drug delivery approach we developed (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh2017; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2025).

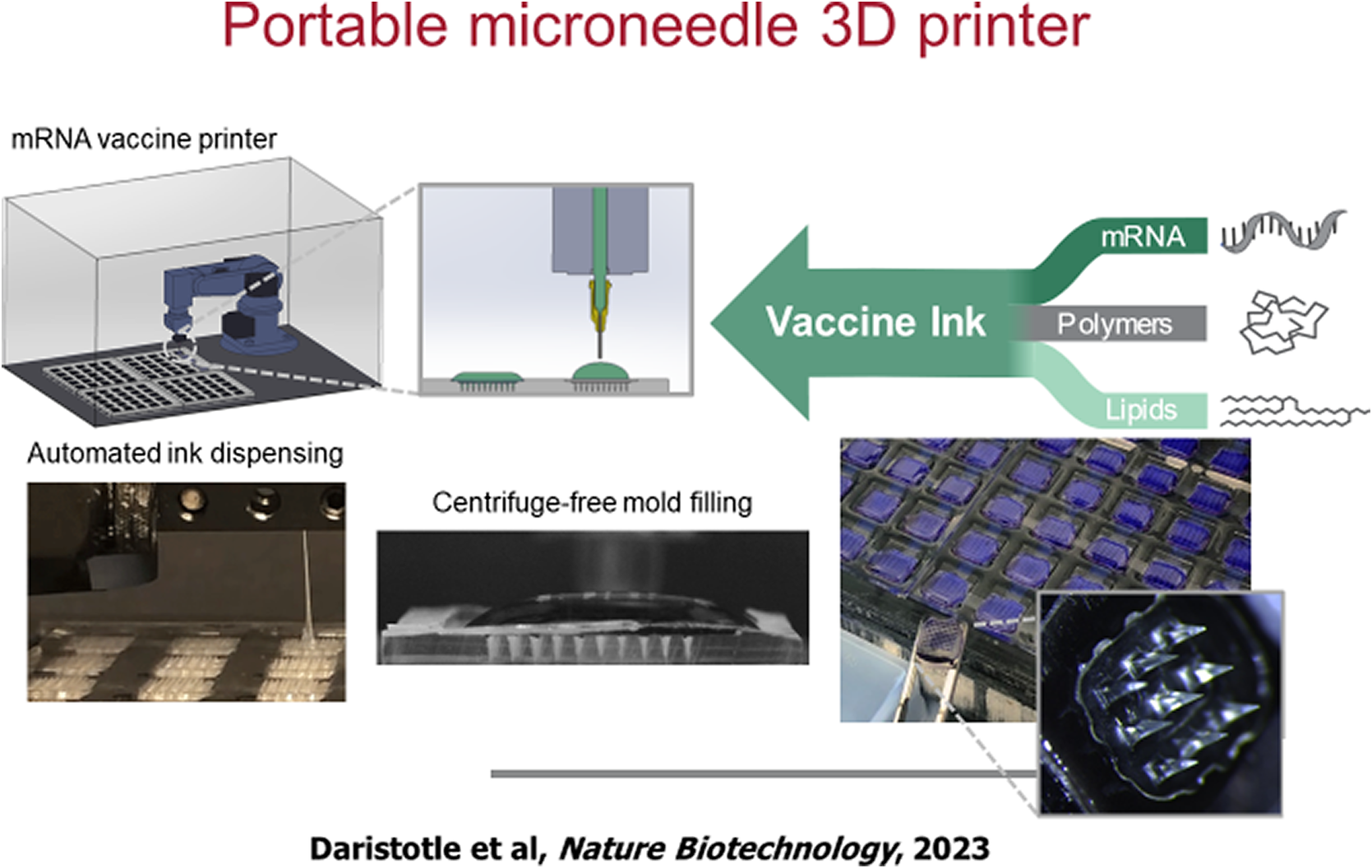

Eventually, one may put these or other vaccines in what are called microneedle patches. The idea of microneedle patches is that they are like a little Band-Aid. However, they have needles, which can enter the skin, but not very deep, so as not to cause much pain, but deep enough, so they will be able to deliver the vaccine. Mark Prausnitz, one of my former students, has done a lot of work on this. With Mark, we have made many of these patches and hopefully someday they could be shipped all over the world. To that end, BARDA approached Ana Jaklenec in our lab and asked ‘could we ever make a small portable 3d printer that you could ship to remote areas in the United States or to army bases, or underdeveloped countries to make such patches?’ In response, we made a tiny desktop 3D printer that could manufacture those patches (Figure 6). These microneedle-lipid nanoparticle patches are stable for 6 months, even at fairly high temperatures (Vander Straeten et al., Reference Vander Straeten2023).

Figure 5. In vitro phagocytosis of surface-modified nanoparticles after 1 hour. The orange dots represent an orange dye encapsulated in PEG-PLGA nanoparticles. When there is no PEG on the surface, they are engulfed by alveolar macrophages in 1 hour, whereas when PEG is added, this engulfment is greatly reduced.

Figure 6. Portable microneedle 3D printer. Modular inks containing mRNA, lipids, and polymer can be customized for microneedle vaccine printing.

Concluding remarks

As discussed in my earlier QRB article (Langer, Reference Langer2019) over the past 50 years, advanced delivery systems have matured from concepts and early research to fundamentally changing how products are developed in medicine, nutrition, consumer products, aquaculture, agriculture, and numerous other areas. They are being developed by numerous scientists and impact the lives of billions of people worldwide. In this current article, we discuss how the past 6 years have witnessed a remarkable demonstration of how discoveries in chemistry, biophysics, and engineering as applied to the development of drug delivery systems have changed the welfare and well-being of the world (Box 1, see also Figure 1). As I concluded my previous QRB article (Langer, Reference Langer2019) with some thoughts about my role as a professor and the guidance I try to impart to my students, I try to do so here as well. Recently, one of my former fellows, Yoon Yeo, a professor at Purdue University, was giving a lecture and showed a slide in which she discussed her research grant being rejected and she paraphrased some advice I gave her long ago: ‘Anyone can do great when things go well. It’s what you do when things are not in your favor that makes the difference’.

Box 1. Milestones since 2019.

1) New capsule can orally deliver drugs that usually have to be injected.

2019 https://news.mit.edu/2019/orally-deliver-drugs-injected-1007

2) New model of the GI tract could speed drug development.

2020 https://news.mit.edu/2020/model-gi-tract-drug-development-0427

3) Explained: Why RNA vaccines for Covid-19 raced to the front of the pack.

2020 https://news.mit.edu/2020/rna-vaccines-explained-covid-19-1211

4) Featured video: Covid-19 vaccines arrive at MIT.

2021 https://news.mit.edu/2021/video-covid-vaccines-0110

5) Big data dreams for tiny technologies.

2021 https://news.mit.edu/2021/big-data-dreams-tiny-technologies-0330

6) Microparticles could help prevent vitamin A deficiency.

2022 https://news.mit.edu/2022/vitamin-a-deficiency-microparticles-1212

7) Vaccine printer could help vaccines reach more people.

2023 https://news.mit.edu/2023/vaccine-printer-could-help-vaccines-reach-more-people-0424

8) A closed-loop drug-delivery system could improve chemotherapy.

2024 https://news.mit.edu/2024/closed-loop-drug-delivery-system-could-improve-chemotherapy-0424

9) New model identifies drugs that should not be taken together.

2024 https://news.mit.edu/2024/new-model-identifies-drugs-shouldnt-be-taken-together-0220

10) Ushering in a new era of suture-free tissue reconstruction for better healing.

2025 https://news.mit.edu/2025/ushering-new-era-suture-free-tissue-reconstruction-better-healing-0801

11) Particles carrying multiple vaccine doses could reduce the need for follow-up shots.

12) Technology originating at MIT leads to approved bladder cancer treatment.

2025 https://news.mit.edu/2025/technology-originating-at-mit-approved-bladder-cancer-treatment-0911

13) A more precise way to edit the genome lowers the error rate of prime editing, a technique that holds potential for treating many genetic disorders.

2025 https://news.mit.edu/2025/more-precise-way-edit-genome-0917

14) An engineered 3D ‘brain on a chip’ with six major cell types to enable personalized disease research and drug discovery. 2025 https://picower.mit.edu/news/mit-invents-human-brain-model-six-major-cell-types-enable-personalized-disease-research-drug.

Research sometimes involves traveling a long road, but I believe that facing the inevitable setbacks that occur as positively as possible and not giving up will enable the students of the future to continue to make advances that will greatly increase basic knowledge and make the world a better place.

Acknowledgments

I thank the NIH, Gates Foundation, and other funding agencies and Emmanuel Tellez and Caroline Glennon for their help preparing this paper and Shuguang Zhang for his very useful comments. Portions of this paper are excerpted from some of the articles referenced herein.

Competing interests

Please see the following link for a list of entities for the period between FY 2021 and the present in which Dr Langer has received or is receiving licensing fees for patents on which he is an inventor, or invested in, consulted for, served on Scientific Advisory Boards/Boards of Directors for, lectured and received a fee from, or conducted sponsored research at MIT for which he was not paid: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/9hrpxuzs72iwvmoqze7rx/AA_OoThWVjAex7X_LhwLRcw?rlkey=llza5qcutubtyx34uqrrfy141&st=zcgqc4qp&dl=0