Introduction

Excavations at Stanwick, Northamptonshire, between 1984 and 1992, revealed an extensive Iron Age and Romano-British settlement. 103 human burials, mostly Romano-British in date, were excavated. These included an unenclosed inhumation cemetery of 36 recovered burials and numerous smaller groups or individual burials. Of the latter, several were phased as probably or possibly fifth-century a.d. in date. This paper presents the results of a programme of scientific dating and chronological modelling carried out on a selection of burials from the cemetery and all the groups identified as potentially of fifth-century date.

Site history

The extensive Iron Age and Romano-British site at Stanwick was located on a gravel terrace on the east bank of the River Nene, 8 km southwest of the Roman town at Irchester(Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Fields and droveways, dating from the mid to late Bronze Age (around 1400–800 b.c.), formed the backdrop to scattered occupation on the site from the very early Iron Age (800–400 b.c.). During the middle Iron Age (400–100 b.c.), an unenclosed settlement developed in an organised landscape. The trackways and enclosures established in the late Iron Age (100 b.c.–a.d. 70) formed the framework for an extensive agricultural settlement that came into being here during the late first to third centuries a.d. and which was continuously occupied through the whole of the Romano-British period.Footnote 2

Fig. 1. Site location plan. (Contains data © Crown Copyright and database right 2023. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number AC0000815036).

Over the course of the second and third centuries, rectangular stone buildings on this site came to join more traditional roundhouses. From the mid-third century on, Stanwick witnessed an increased use of stone for enclosure walls, paved yard surfaces and new buildings.Footnote 3 One of these buildings — an apsidal aisled hall on substantial stone footings — probably dates to the first third of the third century. It was progressively elaborated between c. 270 and c. 340 (Fig. 2), gaining internal dividing walls as well as a bath suite and a cross range, with hypocausted rooms.Footnote 4 Roughly contemporary with the aisled hall and about 12 m to its north-east was a stone temple/mausoleum, which may have stood close to two monumental structures — a tower tomb and a monument dedicated to Jupiter and the divine house — embellished with mythological reliefs carved to a very high standard. Remains were discovered during the excavation of the fourth-century hypocaust, where the sculptured stone was recycled as building material.Footnote 5 The architectural elaborations represented by the aisled hall and the temple/mausoleum were accompanied by a significant change in the settlement’s layout, building types and construction.

Fig. 2. Development of the aisled hall. (a) Mid-third century, site phase 10; (b) late-third century to mid-fourth century, site phase 11; (c) mid-/late-fourth century, site phase 12.

In c. 370, the aisled building was transformed. As part of a major construction project, it was incorporated into a much larger and more sumptuous winged corridor villa, perhaps two storeys tall. These late fourth-century extensions boasted several grand rooms with mosaic floors (the largest of which was installed over a coin <90556> struck between 375 and 378; another coin of the same issue and date <90594> was recovered under the mosaic in the main corridor). The villa had plastered and painted walls, a hypocausted room and a new wing with a bath suite.Footnote 6 This architectural aggrandisement was accompanied by another significant change in the settlement’s layout. A large stone-walled enclosure about 70 m by 90 m was added at the front of the house. It cut across existing boundaries, and nearby building groups including the temple/mausoleum declined or went out of use. The buildings lying between the villa and the major road along the valley were cleared, although some new buildings were constructed along the inside walls of the new courtyard.

The late-phase transformations were made over a relatively short period of time, but a number of minor refurbishments were also undertaken after this initial rebuilding.Footnote 7 This scale of architectural reworking and aggrandisement, although common in Britain in the early fourth century, was rare by the 370s. Sometime after these changes, the villa underwent yet another transformation, the later fourth-century extension changing from a luxurious domestic space into a more utilitarian one, something that happened in the late-Roman period at elite sites not only in Britain, but across the western empire, as these villas’ pars urbana — the part originally built for elite comfort and display — was overtaken by their pars rustica — the productive components of an estate.Footnote 8 An oven or furnace was built through one of the mosaics, and hearths were installed in two rooms in which flagstone floors had been partially removed, including the hypocausted room.Footnote 9

Research objectives

The overall aim of our research has been to determine whether the Stanwick villa remained occupied in the post-Roman period and if so, to establish for how long and to characterise the material culture and burial practices of the latest occupation. We had good reason to suspect that Stanwick might have had a post-Roman phase. Besides the notably late date for the completion of the winged corridor villa and the evidence for its even later modifications, an impressive number of late fourth-century coins were recovered from Stanwick.Footnote 10 3,536 of these coins can be placed into Reece Issue Periods, and 1,773 of these (or 50.1%) are dated after a.d. 330.Footnote 11 However, only 2,079 of these coins were both datable and had accurately recorded findspots, as required for comparisons between areas of the site. Large numbers of Stanwick’s coins, particularly in the earlier periods, were associated with the ritual enclosure or temenos constructed in the early/mid-first century a.d. on top of a Bronze Age barrow and continuing in use for much of the Romano-British period. Considering only the coins with accurate findspots, if the temenos coins are excluded, 1,037 of the site’s remaining datable coins (68.8%) were minted in a.d. 330 or later. Of these, 470 (or 31.3% of the total) were struck during Valentinian’s reign (364–78) and a further 84 (or 6.0%) between 378 and 402 (Table 1). This is one of the largest assemblages of late fourth-century coins found on a rural British site,Footnote 12 and it signals that activity at Stanwick may well have carried on past 402.Footnote 13

Table 1. Stanwick Roman coins summarised by area and issue period

Key to Table 1.

Coin identifications by John Davies (Reference Davies1995).

The ‘whole site’ total (1) is for all Roman coins with a recorded Reece Issue Period, including coins which did not have the co-ordinates of their findspots recorded (total 3536).

The other columns (2–5) only include coins with both a Reece Issue Period and findspot co-ordinates recorded (total 2079). Figures are given for the whole site (1), for the area of the RB settlement (which excludes the temenos) (2), and for the temenos (5). The area of the RB settlement is also subdivided into the area of the villa complex, with extents as in Phases 11 and 12 (3), and the rest of the RB settlement (4).

The ‘% for area’ is the percentage of the coins from that area of the site which date to the issue period or group of issue periods. So e.g. coins of Issue Period 15a account for 21.2% of the coins from the whole site, but form 47.4% of the coins from the villa, 21.7% of the coins from the rest of the RB settlement, and only 1.7% of the coins from the temenos.

Some 103 inhumation burials from across the site were also discovered during the excavation.Footnote 14 A handful included objects that were identified as potentially post-Roman or ‘Anglo-Saxon’.Footnote 15 Four other objects unassociated with burials were also flagged as possibly late in date. A penannular Fowler type D7 brooch <95297> was recovered from a demolition layer of the caldarium of the corridor villa’s bath house,Footnote 16 and a possible late copper-alloy and enamel pin <1035> was similarly found in the destruction layer over the villa.Footnote 17 It was also argued that belt buckles <1634> and <90023> might have also been in use in the fifth century.Footnote 18 Finally, there were several stone-lined graves at Stanwick, a grave structure often considered late and/or post-Roman.Footnote 19

We selected for radiocarbon dating skeletons that we judged most likely to have been buried in the fourth century or later (Fig. 3). We chose 35 human skeletons and the skeleton of a lapdog buried in a cist. Of these, two human inhumations [6006, 6163] contained insufficient carbon for reliable dating. The 33 that were successfully dated come from six different locations on the site — an area just north of the main villa house (Group A); a walled horseshoe-shaped enclosure north-east of the villa (Group B); a small, more formal unenclosed cemetery to the north-west of the villa (Group C); a very long-lived north–south boundary (Group D), in and around the villa and its stone-walled enclosure (Group E; Fig. 4), and a single burial (Burial F) recovered from a recut of a ring-ditch [LE192143].

Fig. 3. Location of burials, with dated burials shown by group. (MS is the mid-Saxon burial).

Fig. 4. Location of burials around the late fourth-century villa and courtyard (Group E). (6170 is the mid-Saxon burial).

Radiocarbon dating

A total of 46 radiocarbon measurements are available on bone samples from these 33 human inhumations and the dog burial (Table 2). The strategy for sampling for radiocarbon determinations was to ensure that suitable material was obtained whilst minimising impact on the future research potential of the skeletal collection. Diaphyseal bone from the femur or tibia, or alternatively another long bone, as available, was sampled. Preference was given to bones that were already incomplete and fragmented; pathological areas were avoided, as were morphological landmarks. In a few infant burials, suitable long bones were not available or else sampling them would have caused unacceptable impact. In these instances, ribs were substituted.

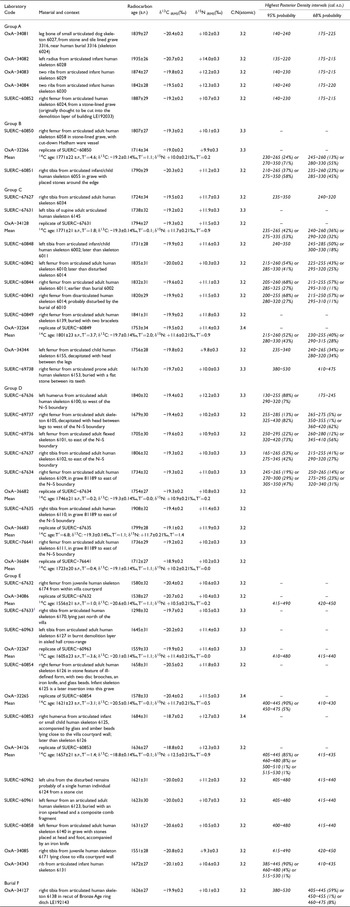

Table 2. Radiocarbon and stable isotopic measurements from later Roman Stanwick: replicate measurements have been tested for statistical consistency and combined by taking a weighted mean as described by Ward and Wilson (Reference Ward and Wilson1978; T′(5%)=3.8, ν=1 for all; Highest Posterior Density intervals derived from Model 1; see Fig. 5)

1 SUERC-67633: this burial is clearly considerably later than the other dated burials from Stanwick and so has been excluded from the modelling. This measurement calibrates to cal. a.d. 655–775 (95% probability: Stuiver and Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993), probably to cal. a.d. 665–705 (34% probability) or cal. a.d. 740–775 (34% probability).

Twenty-six measurements were made by the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC-) in 2015–17. The bones were processed by gelatinisation and ultrafiltration, before combustion to carbon dioxide, graphitisation and dating by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry.Footnote 20 Twenty samples were dated at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (OxA-) in 2015–18. These were processed by gelatinisation and ultrafiltration.Footnote 21 The samples were then combusted and graphitisedFootnote 22 and dated by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry.Footnote 23 All the samples for which results were reported produced bone collagen that met the quality standards employed by the laboratories concerned.Footnote 24

The radiocarbon results are all conventional radiocarbon ages.Footnote 25 The δ13C and δ15N measurements reported for these samples were obtained by Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) on the gelatin extracted for dating. At Oxford, δ13C and δ15N were measured by a mass spectrometer attached directly to the CN analyser used to combust the samples to carbon dioxide. At SUERC, δ13C and δ15N samples were prepared and analysed as described by Sayle et al. Footnote 26

Replicate measurements are available on ten human skeletons that were sampled and submitted to both laboratories for dating. Eight of these pairs are statistically consistent at the 5% significance level, with one more consistent at the 1% significance level and the other divergent at more than this level of significance (Table 2).Footnote 27 Pairs of replicate δ13C values and δ15N are also available for these skeletons, all of which are statistically consistent at the 5% significance level (Table 2).Footnote 28 This reproducibility is in line with statistical expectation.

Bayesian chronological modelling

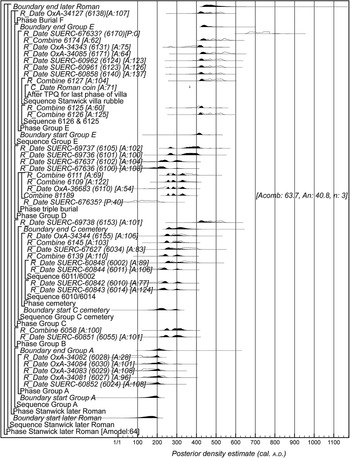

The chronological modelling has been undertaken using OxCal 4.4,Footnote 29 and the calibration curve for the northern hemisphere that is currently internationally agreed (IntCal20).Footnote 30 The models are defined by the OxCal CQL2 keywords and by the brackets on the left-hand side of Fig. 5 (and see Supplementary Information 1 and 3). In the diagram, calibrated radiocarbon dates are shown in outline and the posterior density estimates produced by the chronological modelling are shown in solid black. Distributions other than those relating to particular samples correspond to aspects of the model. For example, the distribution ‘start Group E’ is the estimated date when the first burial in and around the villa and its stone-walled enclosure was made. The Highest Posterior Density intervals which describe the posterior distributions are given in italics.

Fig. 5. Probability distributions of dates from late Roman burials at Stanwick. Each distribution represents the relative probability that an event occurs at a particular time. SUERC-67633 and SUERC-67635 are not included in the model for reasons explained in the text. The large square brackets down the left-hand side along with the OxCal keywords define the overall model exactly.

The model shown in Fig. 5 has good overall agreement (Amodel: 64Footnote 31), which means that the radiocarbon dates are compatible with the prior information included in the model. This information is of three types. First, groups of samples which are archaeologically related are defined. So, for example, all the radiocarbon dates (except, unexpectedly, that for skeleton 6170 (SUERC-67633)) are from a contiguous period of activity on the site. There are further, spatial, groupings (Groups A, C and E) which have sufficient radiocarbon dates for the relatedness of individuals within these sub-groups to be formally modelled.Footnote 32 These relationships have been modelled using the uniform phase approach described by Buck et al. Footnote 33 Second, a number of relative dating sequences derived from stratigraphic relationships between burials have been included. These are: skeleton 6014 (SUERC-60843) was probably disturbed by the burial of skeleton 6010 (SUERC-60842); burial 6011 (SUERC-60844) is earlier than burial 6002 (SUERC-60848); and skeleton 6126 (SUERC-60854 and OxA-32265) is earlier than skeleton 6125 (SUERC-60853 and OxA-34126). Third, burial 6127 (SUERC-60963 and OxA-32267) was found within a burnt destruction or demolition layer in the cross-range of the aisled hall component of the villa, post-dating the mortar floor (84924) beneath it. The floor, in turn, is dated after a.d. 367 by a coin underneath it <90322>, struck between 367 and 375. The dates on the three skeletons from ‘grave’ 81189 have been combined on the basis that there is strong archaeological evidence that the three corpses were interred in a single event (see below).Footnote 34

Chronological Model 1 (Figs 5 and 6)

Group A

These burials lay in an area about 50 m north of the late Roman villa building. The remains of a minimum of three infants were uncovered here, grouped around a stone and tile cist containing a small lapdog [6027]. Three of the infants [6028, 6029, 6130] were dated. Nearby an adult woman [6024], probably in a coffin, was buried in a stone-lined grave (Fig. 7). The site’s excavators believed that the late first- to mid-second-century pottery sherds in the grave fills were residual, and graves of the dog and the woman cut through the demolition layer of one of the site’s rectilinear stone-footed buildings, and so were late in the site’s sequence.Footnote 35

Fig. 6. Probability distributions of durations and intervals, derived from the model defined in Fig. 5.

Fig. 7. Burial 6024 (Group A) in stone-lined grave.

Although the accurate calibration of the radiocarbon dates for this group of burials is problematic (see below), the chronological modelling does suggest that all Group A burials predate the building’s collapse, and that the graves were dug into the surface below the collapsed rubble. The modelling suggests these burials are earlier than (or possibly contemporary with) the first phase of the aisled hall [LE192235], built in the first third of the third century.Footnote 36

The chronological modelling undertaken using IntCal20 suggests that burial in this area began in cal. a.d. 120–215 (95% probability; start Group A; Fig. 5), probably in cal. a.d. 160–210 (68% probability), and ended in cal. a.d. 145–270 (95% probability; end Group A; Fig. 5), probably in cal. a.d. 185–240 (68% probability). Overall, burial in this area continued for a period of 1–110 years (95% probability; use Group A; Fig. 6), probably for a period of 1–45 years (68% probability). There are insufficient radiocarbon dates from this group fully to counteract the scatter on the measurements, which leads to long tails on the posterior distributions. It is clear from the shape of these, however, that on the basis of Model 1, burial in this area probably occurred for no more than a generation or two c. 200 cal. a.d. Thus, the individuals buried here probably lived at a time when Stanwick was a relatively large, nucleated agricultural settlement, with both circular and rectangular structures with stone footings, stone-lined wells and corn dryers and stone in boundary walls, and perhaps in the same generation in which the aisled hall was built.Footnote 37 It is interesting that the elaborately buried lapdog — one of the smallest dogs yet found in Roman BritainFootnote 38 — belongs to this phase. These little animals, long prized by Roman elites in the Mediterranean, became popular in Britain in the Roman period, although they were not much seen outside urban centres until the second century.Footnote 39 The Stanwick lapdog may have been both a novelty and a status animal. It is an interesting example of the way rural provincial families of means were adopting some of the trappings of Roman elite culture in the late second and early third centuries. Both the infant burials placed in companionable clusters and their association with dogs are common on Romano-British sites.Footnote 40

Group B

Graves of an adult [6058] and an infant/child [6055] were uncovered from the horseshoe-shaped enclosure [LE192037], and they constitute our burial group B. This enclosure, first established in the late Iron Age and extensively recut in the first century a.d., lay about 100 m north-east of the main villa building.Footnote 41 Stratigraphic analysis and the presence of early Saxon pottery indicate the area remained in use during the latest phase of the settlement.Footnote 42 Like the dog and the woman in Group A, both were interred in stone-lined graves, and a Hadham ware vessel with a cut-down rim <75393> sat next to the left foot of the adult(Fig. 8). Because the vessel was damaged and modified before its deposition, it was thought to indicate a late or post-Roman date for these burials.Footnote 43 Their radiocarbon dates, however, place them firmly in the mid–late third or earlier fourth century (6058, SUERC-60851; Fig. 5; Table 2), contemporary with both the aisled hall phases and the cemetery described below.

Fig. 8. Burial 6058 (Group B) in stone lined grave with trimmed-down Hadham ware vessel.

Group C

The burials of Group C were recovered from an unenclosed cemetery. Most of the 36 individuals found here were extended, supine and unaccompanied by grave goods. It was thought that burials here began during the aisled hall phases (Fig. 2, a,b) and continued through the fourth century (Fig. 2, c) and into the post-Roman period, although the phasing report underscores that little evidence was available to date these burials to the later Roman phases of the settlement.Footnote 44 Given that a number of graves in the cemetery were intercut, it seemed likely that the cemetery was in use for an extended period of time. Two bangles <90010 and 90011> buried with one of the women here [6139] were assigned possible fifth-century dates.Footnote 45 So it was argued that the cemetery was probably a long-lived one, beginning c. a.d. 230 and continuing into the early post-Roman period.

All but one of the nine individuals we radiocarbon dated from this group [6002, 6010, 6011, 6014, 6022, 6034, 6039, 6155] appear to be from a coherent phase of burial falling earlier rather than later in this date range. The woman with the bracelets probably died by the first decades of the fourth century cal. a.d. at the latest (6139; Fig. 5; Table 2), and a child buried in the cemetery, who had been decapitated [6155], probably died at a similar time (OxA-34344; Fig. 5; Table 2). The remaining burials, all of which are supine and unaccompanied, are of much the same date. Taken together, it seems people started to be buried in the cemetery in cal. a.d. 165–255 (72% probability; start C cemetery; Fig. 5) or in cal. a.d. 270–320 (23% probability), probably in cal. a.d. 195–245 (59% probability) or cal. a.d. 290–305 (9% probability); and that burial ended there in cal. a.d. 245–390 (95% probability; end C cemetery; Fig. 5), probably in cal. a.d. 250–275 (18% probability) or cal. a.d. 290–350 (50% probability). The cemetery was in use for a period of 1–190 years (95% probability; use C cemetery; Fig. 6), probably for a period of 1–105 years (68% probability). This cemetery was probably used for several generations, between the earlier third and the earlier fourth centuries cal. a.d. Those buried here, therefore, were contemporary with the aisled hall, but it is unlikely that any, contrary to what the phasing report suggested, lived during the late corridor villa phase of the settlement (Fig. 2 c).

We initially considered one man, buried on the eastern edge of Group C [6153], to be a ninth member of this group. His was a prone burial, and someone had placed a flat stone between his teeth, perhaps as a substitute for his missing tongue (Fig. 9).Footnote 46 It is now clear, however, that this burial was 20−240 years (95% probability; gap 6153; Fig. 6) later, probably 80−180 years (68% probability) later than the latest burial in Group C, and that he was a contemporary of the later community burying its dead in and around the corridor villa (see below, Group E), as he was probably buried in the early–mid fifth century cal. a.d. (SUERC-69738; Fig. 5; Table 2).

Fig. 9. Skull of burial 6153 (Group C), showing the flat stone placed in his mouth.

Group D

Our Group D is made up of 14 burials along the persistent north/south boundary, some of which cut Roman-period ditches. Seven skeletons from this group have been dated, three of which [6109, 6110 and 6111] came from a triple burial (81189). Replicate measurements have been made on each of these three skeletons: those from 6109 and 6111 are statistically consistent, but those from 6110 are widely divergent (Table 2). Excluding SUERC-67635, the dates are compatible with the interpretation that these skeletons formed part of a single burial event (Acomb: 63.7, An: 40.8, n: 3). It seems that SUERC-67635 is slightly too old, and for this reason it has been excluded from the analysis. Triple burial 81189 occurred in cal. a.d. 245–265 (19% probability; 81189; Fig. 5) or cal. a.d. 270–300 (29% probability) or cal. a.d. 305–350 (47% probability), probably in cal. a.d. 250–265 (14% probability) or cal. a.d. 275–295 (23% probability) or cal. a.d. 320–340 (31% probability). Burials were probably made along this boundary throughout much of the Roman period, from the early third century to the later fourth century (Fig. 5).Footnote 47 Burial in or alongside ditches marking enclosures or property boundaries was ubiquitous in rural Roman Britain.Footnote 48

Group E

The Group E burials lay in and around the corridor villa and its long courtyard wall. The group comprises 10 individuals, all of whom were radiocarbon dated. Several individuals within this group were placed in the ground with grave goods that had been flagged as potentially post-Roman.Footnote 49 The grave of one individual [6127] is stratigraphically later than a coin minted in a.d. 367 at the earliest. Another individual [6123] was buried with an iron spearhead <95163> that was described in the phasing report as ‘fifth-century or later’.Footnote 50

One woman [6126] was buried close to the outside of the courtyard wall, in a grave which included a linear stone-built feature which could have been the base of a grave marker. She went into the ground with two disc brooches, a belt slider (Fig. 10) and a knife, which were considered ‘Anglo-Saxon’.Footnote 51 She also had a bead string with one amber and 45 glass beads.Footnote 52 Most of the latter (23 beads) were annular and translucent blue, but there were also six bi- or polychrome beads including two ‘traffic light’ beads in red, green and yellow. An infant [6125] was inserted into the woman’s grave at some point after her burial. The string of 13 beads which accompanied it again had a single amber bead and included four deep-blue beads. The relative numbers of amber and blue glass beads, along with the individual types where they can be closely dated, assign these strings to Brugmann’s Phase A1, for which a date of a.d. 450–530 is normally suggested.Footnote 53 A date in the earlier part of the range might be appropriate, as it is possible that a green cylindrical bead (context 84758) was originally part of the child’s string and these belong to the late fourth and earlier fifth centuries.Footnote 54 A selection of the beads are shown in Fig. 11. The beads and how they were worn are considered in more detail in Section 4.2 of the Supplementary Information. A single bone survived from the disturbed burial of a second infant in this grave.

Fig. 10. Copper-alloy adornments with burial 6126 (Group E). (1) Brooch <95572>; (2) brooch <95575>; (3) belt fitting or slider <95573>.

Fig. 11. Beads from burials 6125 and 6126.

All in all, it appears that burials began here in cal. a.d. 365–440 (92% probability; start Group E; Fig. 5) or cal. a.d. 450–475 (3% probability), probably in cal. a.d. 400–430 (68% probability), and ended in cal. a.d. 420–515 (94% probability; end Group E; Fig. 5) or cal. a.d. 520–535 (1% probability), probably in cal. a.d. 425–460 (68% probability). It is 56% probable that the last of these burials occurred in the second quarter of the fifth century cal. a.d. Burial in Group E occurred for a period of 1–105 years (95% probability; use Group E; Fig. 6), probably for a period of 1–45 years (68% probable). The shape of the posterior distribution suggests that continuing burial for a few decades is most likely.

One extended, unaccompanied burial in this area [6170], found just north of the villa with its feet up against a Roman-period wall, was not buried in the late/post-Roman period, but dates to the Middle Saxon period. The burial dates to cal. a.d. 655–775 (95% probability; SUERC-67633),Footnote 55 probably to cal. a.d. 665–705 (34% probability) or to cal. a.d. 740–775 (34% probability). This fits well with the practice described by Bell, in which individual or small groups of post-Roman burials were deliberately placed in relation to still-visible Roman structures, often with particular emphasis on their relationship to wall foundations, which ‘seems to have reached its peak at the turn of the seventh century’.Footnote 56

Burial F

Burial [6138] was recorded under salvage conditions, but appears to have been placed in a recut of a possible prehistoric ring ditch (LE192143). It was fairly complete, apart from some machine damage to the skull, but poorly described. It was probably supine, and the only finds described as associated were iron nails, but the grave fill also contained nine hobnails and a copper-alloy bracelet <96019>, as well as mixed Romano-British pottery, including MLC4 forms, and a single medieval sherd of mid-thirteenth-century date. It also probably dates to the early fifth century (OxA-34127; Fig. 5; Table 2).

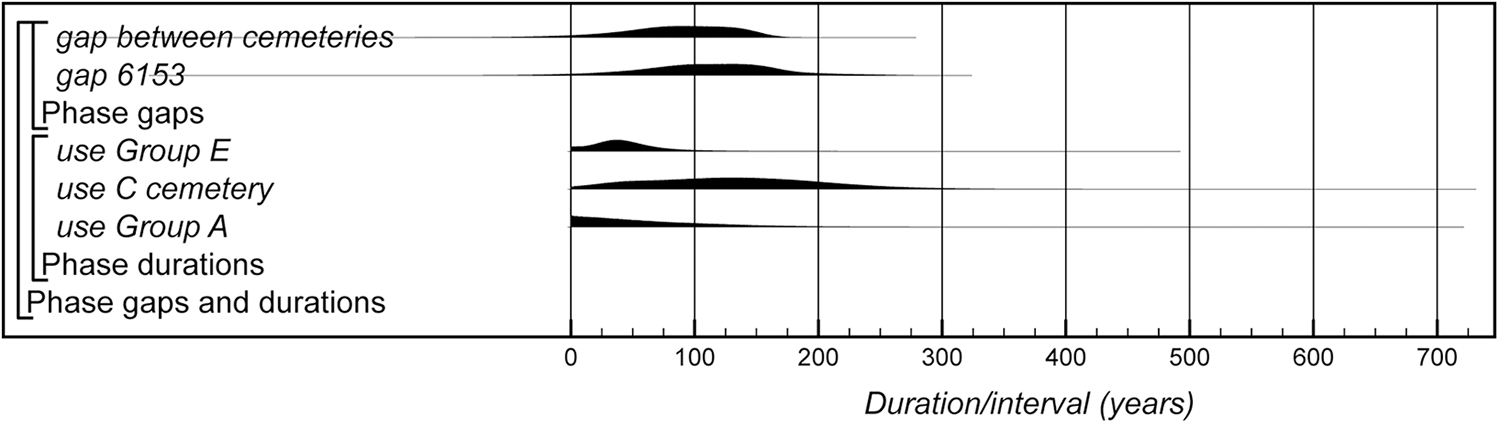

Overall dating of these burials according to Model 1

The estimated date for the start of later Roman burial at Stanwick (start later Roman; Fig. 5) probably does not relate reliably to any real change in activity on the site, since for this project we deliberately did not sample potentially earlier Roman burials. The estimated date for the end of later Roman burial (end later Roman; Fig. 5) is, however, meaningful. The model suggests that this ending occurred in cal. a.d. 425–565 (95% probability; end later Roman; Fig. 5), probably in cal. a.d. 435–505 (68% probability).

Fig. 12 shows the key parameters for the latest Roman burials at Stanwick. The final burial in Group E is probably later than both the skeleton with a stone its mouth in the area of Group C (6153, SUERC-69738; 67% probable) and Burial F (6138, OxA-34127; 73% probable). The date estimate for the end of Roman burial at Stanwick (end later Roman), however, is later than the other three parameters since it allows for the possibility that there are other burials of similar date in the Stanwick landscape which have not been recovered or sampled for radiocarbon dating. Overall, current evidence suggests that later Roman burials were probably made at Stanwick in the second half of the fifth century cal. a.d., but probably did not continue beyond the end of the century.

Fig. 12. Key parameters for latest Roman activity at Stanwick, derived from the model defined in Fig. 5.

Chronological Models 2 and 3

Diet and dates

Diet-induced radiocarbon offsets can occur if a dated individual has taken up carbon from a reservoir not in equilibrium with the terrestrial biosphere.Footnote 57 If one of the reservoir sources has an inherent radiocarbon offset — for example, if the dated individual consumed marine fish or freshwater fish from a depleted source — then the bone will take on some proportion of radiocarbon that is not in equilibrium with the atmosphere. This makes the radiocarbon age older than it would be if the individual had consumed a diet consisting of purely terrestrial resources. Such ages, if erroneously calibrated using a purely terrestrial calibration curve, will produce anomalously early radiocarbon dates.Footnote 58

In order to understand the potential impact of dietary reservoir effects on our modelled chronology for the Stanwick burials, we have constructed an alternative model which employs a personalised calibration curve for each dated individual.

The first step in the analysis is to estimate the proportions of different food sources in the diets of the dated individuals.

Stable isotopes

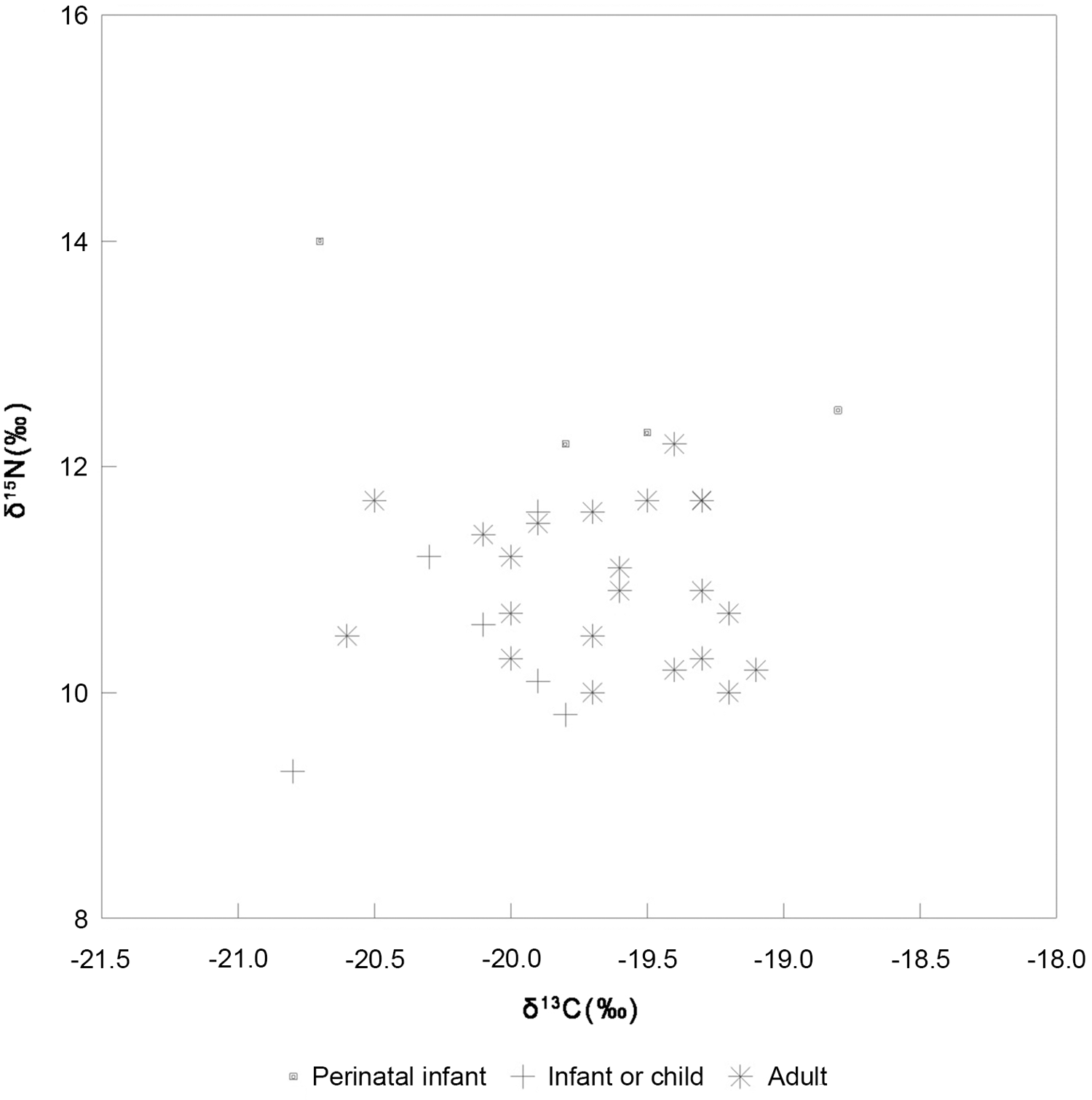

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios in bone collagen for the 33 human burials have been analysed with the aim of investigating diet. Specifically, work was aimed at investigating patterning with respect to age at death, sex, and the date of the burials. In addition, application of a Bayesian mixing model has been used to attempt to reconstruct the contribution of various food classes to diet in the Stanwick community. The osteological methods, together with the dietary modelling, are fully described in Supplementary Information 2; only a brief summary is presented here.

The results are summarised in Table 3 and plotted in Fig. 13. The isotopic data are broadly similar to others reported from coeval rural and urban contexts (Supplementary Table S1) in indicating a diet dominated by terrestrial resources. Lilliefors testsFootnote 59 indicate no significant departures from normality for the δ13C or the δ15N data, permitting parametric statistical analyses. There is no correlation between carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios so the two are analysed separately. There is no sex difference in δ13C or δ15N. Analysis of variance shows significant variation in both δ13C (F=3.79, p=0.03) and δ15N (F=14.3, p<0.001) over the three age groups in Table 3. For δ13C, post hoc multiple comparisons using the Tukey HSD statistic indicate that the infant/child group has a more depleted δ13C than the adults, although the mean difference is small (c. 0.5‰). A similar pattern, whereby adults showed a somewhat more enriched δ13C but similar δ15N to children and adolescents, has been reported from Roman London.Footnote 60 Those authors suggested that a shift in the minor aquatic component in diets from freshwater to marine might be responsible. Perhaps a similar age-related dietary shift occurred in the Stanwick population. Turning to δ15N, the Tukey HSD statistic indicates that perinatal infants are enriched in 15N compared to the two older age groups. Their values range from 12.2–14.0‰, and all are greater than the highest adult female value. In general, infant skeletal δ15N often tends to be elevated compared both to older individuals and to stillbirths.Footnote 61 This is thought to reflect the influence on bone collagen of breastfeeding, breastmilk having a higher δ15N than most other foods. The above result suggests that these perinatal infant remains represent not stillbirths, but live births who suckled sufficiently prior to death to elevate their bone collagen δ15N.

Fig. 13. δ13C and δ15N.

Table 3. Summary statistics of carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes from human skeletons at Stanwick (‰)

1 aged c. 36–40 weeks gestation; 2aged c. 3 months–15 years; 3aged 18+ years. F, female; M, male; U, unsexed.

Turning to the adults, those burials where the median of the posterior density estimate is after a.d. 400 have a mean δ13C that is c. 0.7‰ more negative than earlier interments (Supplementary Figure S1), a statistically significant pattern (t=4.52, p=0.002, analysis omits chronological outlier 6170). Review of stable isotopic data from Roman Britain has led to the suggestion that, while still a minor component, seafoods made a greater contribution to diets than was the case in the pre-Roman Iron Age.Footnote 62 One interpretation of the temporal pattern in δ13C at Stanwick could be that it represents a reversion to a more completely terrestrial diet following the collapse of trading patterns associated with Empire, with the minor aquatic component now comprising primarily freshwater rather than marine foods. An alternative explanation is that this may be a small canopy effect caused by environmental change, specifically reforestation after a.d. 400: δ13C values tend to be more depleted in food resources from a more heavily wooded environment.Footnote 63 These potential explanations require further evaluation, particularly using analyses of Stanwick faunal remains, data from which are currently lacking.

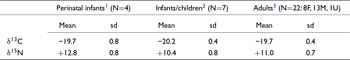

In an attempt to model diet more closely, the Bayesian mixing model FRUITSFootnote 64 was applied. To summarise the results, the model supports the inference that terrestrial foods dominated diets at Stanwick (Fig. 14). However, there are considerable uncertainties concerning the relative importance of terrestrial animal versus plant products (Fig. 14 and Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). These high levels of uncertainty severely limit the value of the FRUITS method for modelling diet in this particular data set. This problem, and some possible reasons for it, are explored in Supplementary Information 2.

Fig. 14. Box-plot of reconstruction of mean Stanwick diet using FRUITS. The boxes provide the 68% and the whiskers the 95% confidence intervals. The continuous line is the mean, the dotted line the median. FWfish = Freshwater fish.

Model 2

Although the FRUITS modelling of the stable isotopic data suggests that non-terrestrial foods provided a very low proportion of diet amongst adult and sub-adult humans at Stanwick (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5), even small proportions of such foods could impart a slight reservoir age to the dated individuals, so we have constructed an alternative chronological model to investigate the potential scale of this effect.

The marine proportion of the diet was modelled using the marine calibration dataset and a local ΔR value of –179±90 b.p. (Marine20).Footnote 65 This was calculated using the 14CHRONO Marine20 Reservoir database using the 20 closest points to Stanwick around the English coast.Footnote 66 Since the freshwater offsets observed from English sites by Keaveney and Reimer range from 703±32 b.p. to 2±54 b.p.,Footnote 67 the freshwater fish proportion of the diet was modelled using the terrestrial calibration dataset offset by a wide uniform distribution from 0–750 b.p. (IntCal20).Footnote 68 The remaining proportion of the diet was modelled using the terrestrial calibration curve (IntCal20).Footnote 69

For each dated individual the proportions of each carbon pool suggested by the FRUITS model were used to construct a personalised calibration curve. The three main carbon reservoirs were defined for the model as a whole: the atmospheric/terrestrial pool (IntCal20), the local marine environment (LocalMarine, offset from the global average with a ΔR of −179±90 b.p.) and the local freshwater (offset from the atmosphere by anywhere between 0 and 750 radiocarbon years). These curves were then combined in two stages for each case, first mixing the IntCal20 and LocalMarine in the required relative proportions (using the Mix_Curves function of OxCal v4.2),Footnote 70 and then further diluting that mixture with a contribution from the LocalFreshwater curve. The form of the model is identical to Model 1 (Fig. 15), and it is defined by the CQL2 code provided as Supplementary Information 3.

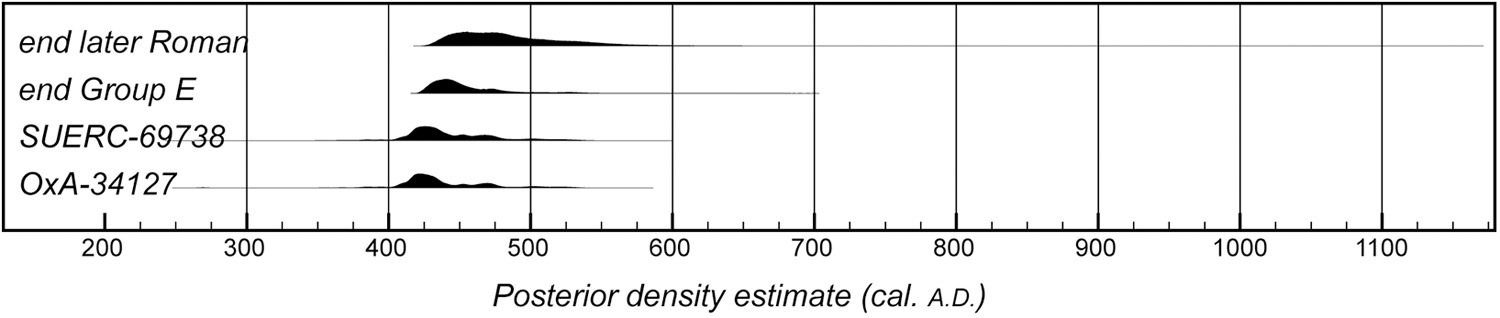

The posterior distributions for the dates produced by Model 2 for each of the 33 individuals included in the chronological modelling from Stanwick are shown in blue in Fig. 15 (those from Model 1 are shown in black). The results from Model 2 are, as expected, slightly later than those from Model 1, the medians of equivalent distributions being between 71 and 18 years older. The shape of the radiocarbon calibration curve and the proportion of non-terrestrial resources consumed through the period means that the scale of this offset varies over time, being on average 49 years for skeletons where the median of the posterior distribution lies in the second or third century a.d. (n=18) and 29 years for those where the median of the posterior distributions lies in the fourth or fifth century a.d. (n=13). This means, for example, that the medians of the posterior distributions for burials in Group E fall in the a.d. 420s and 430s according to Model 1, and in the a.d. 450s and 460s according to Model 2.

Fig. 15. Key parameters for dates from late Roman burials at Stanwick, calculated using IntCal20 (Model 1: black), mixed-sourced calibration as described in the text (Model 2: blue), and IntCal13 (Model 3: red).

We would like to emphasise that, given the difficulties of accurately estimating such small non-terrestrial components to diet from stable isotope values and our currently restricted understanding of past freshwater and marine reservoir effects, Model 2 can only be considered as indicative of the scale of dietary offsets that may be present in this dataset.

Model 3

The currently internationally agreed iteration of the radiocarbon calibration curve for the northern hemisphere, IntCal20,Footnote 71 represents a major update of the previous calibration curve, IntCal13.Footnote 72 Over the first half of the first millennium a.d., IntCal20 is based on over 550 calibration datapoints, in comparison to IntCal13, which was based on just over 100 (Fig. 16). The data included in IntCal13 were measured on decadal and bi-decadal blocks of wood, whereas IntCal20 also includes measurements on 5-year blocks for the entire half-millennium, and measurements on single-year tree-rings between a.d. 290 and a.d. 486.

Fig. 16. IntCal20 (red) and IntCal13 (grey) for the first half of the first millennium a.d., with the calibration datasets on which they are based. Those from Seattle (QL; Stuiver and Braziunas Reference Stuiver and Braziunas1993; Stuiver et al. Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Braziunas1998), Belfast (UB; McCormac et al. Reference McCormac, Bayliss, Baillie and Brown2004; Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Pilcher, Baillie, Corbett and Qua1986) and Waikato (Wk; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Palmer, Boswijk, Reimer and Brown2009) are included in both curves, those from Groningen (GrA; Sakamoto et al. Reference Sakamoto, Imamura, van der Plicht, Mitsutani and Sahara2003), Mannheim (MAMS-; Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Kromer, Sirocko, Esper, Lindauer, Nievergelt, Heussner and Westphal2019) and Palaeo Labo Co. Ltd (Sakamoto et al. Reference Sakamoto, Imamura, van der Plicht, Mitsutani and Sahara2003; Okuno et al. Reference Okuno, Hakozaki, Miyake, Kimura, Masuda, Sakamoto, Hong, Yatsuzuka and Nakamura2018) only in IntCal20.

In general, the calibration data, and thus the two curves, follow each other closely. There is, however, a more appreciable divergence between c. a.d. 80 and c. a.d. 220.Footnote 73 As previously observed,Footnote 74 this can lead to substantive differences in calibrated radiocarbon dates in this period. To investigate the effect of this issue on the modelled chronology for the late Roman burials at Stanwick, we calculated Model 1 using IntCal13. The posterior distributions for the dates produced by Model 3 for each of the 33 individuals included in the chronological modelling from Stanwick are shown in red in Fig. 15. The outputs of this model are slightly older than those provided by Model 1, the medians of equivalent distributions being between 74 and 5 years older. Again, the offset varies through time, with those before c. a.d. 220 offset by an average of 48 years and those after c. a.d. 220 offset by an average of 15 years.

The posterior distributions for the dates of the Stanwick burials, shown in Fig. 15, generally show a good degree of overlap. Those falling in the fourth and fifth centuries a.d. may vary by a few decades, depending on which calibration data are used or how potential dietary reservoirs are managed. The balance of probability in multi-model distributions may vary between peaks. More substantive differences are seen in the burials in Group A. Using IntCal20, these fall in the decades around a.d. 200 and perhaps three or four decades later using the mixed source calibration; but using IntCal13, these all fall in the decades around a.d. 130, some 60 or 70 years earlier.

The greater quantity of data in IntCal20 means that it is usually more robust than IntCal13. In this case, however, we do not know why the data we have from Japanese trees (GrA-, PLD-; Fig. 16) diverge from the data we have from European and North American trees (QL-, UB-, Wk-, MAMS-; Fig. 16) only during the second century a.d., whereas the two datasets are compatible at other times. Nakamura et al. suggest that there may be a time-variable offset in Japanese trees,Footnote 75 perhaps arising from variations in the East Asian monsoon, so it is possible that there may be locational differences in atmospheric radiocarbon that are important for archaeological interpretation at this time. Further research is clearly required before robust radiocarbon calibration can be undertaken in the second century a.d., but even on the basis of current understanding, it is clear that the Group A burials at Stanwick are earlier than those we have dated elsewhere on the site.

The finds from the gravesFootnote 76

Small finds, excluding beads

By Angela Wardle

The finds from the graves comprise a small but varied group of objects consisting chiefly of personal ornament and dress accessories, most worn on the bodies of the deceased, together with equipment in the form of knives, a spear and coins. The general style of the objects worn on the body and the presence of the knives place the graves in the post-Roman period and certain individual objects contribute in more detail to the evidence for the dating of the burials. The following summarises the grave goods within the groups identified in the dating study, which are described in more detail above.

Group A late second/early third century

No grave goods present.

Group B mid–late third/early fourth century

One burial [6058], with evidence for a coffin, contained a ceramic vessel <75393>, but there were no other grave offerings.

Group C mid–late third/early fourth century (except later burial 6153)

Only one of the 36 individuals was buried with grave goods. One burial, a woman [6139], wore a penannular bracelet on each wrist, <90010> with plain terminals, (Cool Group V) and <90011> with three vertical grooves at each terminal (Cool Group VI).Footnote 77 Both are long-lived forms, in use from the first to the fourth century and perhaps beyond.Footnote 78 They would therefore fit well within the proposed mid-third/early fourth-century date for the burial.

Group D third/fourth century

A two-strand cable twist bracelet was found on the left wrist of 6109, in the triple burial [6109, 6110, 6111]. Most of the bracelet survives, but it is in several pieces. The cable bracelet (Cool Group I) is a very common type, in circulation throughout and beyond the proposed period.Footnote 79

Group E fifth century

The finds from burials in this area were consistently later in date than the previous groups. Burial [6127] was probably associated with a copper-alloy nummus of the House of Theodosius dating to the period a.d. 388–395, and a nail-cleaner strap-end <95512>.Footnote 80 The form, which dates from the fourth century and may signal high status, has been studied by Eckardt with Crummy.Footnote 81 This example falls into their group with rounded lugs.Footnote 82

The dating of the disc brooches within Burial 6126 fits with the proposed dates for Group E. <95572>, a sturdy thick disc with ring and dot decoration, is typical of early Anglo-Saxon disc brooches with tinning (white metal plating) and a decorative motif which is seen also on late Romano-British metalwork.Footnote 83 The general dating for the use of the disc brooch was considered by Dickinson to be between c. 450 and c. 550.Footnote 84 The second brooch <95575> with an applied decorated disc is also likely to be of fifth-century date. Parallels for the design come from a pair of brooches in Luton grave 23, (BL/69/33) Luton (BL/122/33) and on a disc from Fairford, Ashmolean Museum 1961–5.Footnote 85 Evison notes that the design is unusual, in that it has all the typical characteristics of brooches found in fifth-century contexts, but the star has only four points.

The general dating of this grave to the fifth century is further confirmed by the presence of a decorative tubular copper-alloy belt fitting <95573> found in the pelvic area of the skeleton. There are parallels for similar objects from other early medieval cemeteries, for example Droxford, Hampshire (BM 1902,0722.52), there dated to the fifth century and from Bowcombe Down,Footnote 86 which is more elaborately decorated. Unlike the Stanwick example, both these examples have loops attached to the top. Two undecorated tubular belt loops from Mucking, however, have no loops and appear functionally similar to the one at Stanwick.Footnote 87 These fittings were dated to the fifth century by Evison.Footnote 88

Burial 6123 also contained an iron spear <95163>, typical of early Anglo-Saxon grave goods.

Burial F early fifth century

A copper-alloy strip bracelet, <96019> was recorded as coming from the grave fill [85447], Burial 6138, but there is no mention on the skeleton record, and the excavation took place under adverse conditions.Footnote 89 However, the bracelet, which dates from the fourth century or later, is complete and may well have been worn or placed in the grave originally. Hobnails were also recorded from this context, suggesting that shoes were also present.

The beads with Skeletons 6125–6Footnote 90

By H.E.M. Cool

The recovery of beads with two of the individuals who formed part of Burial Group E provides a welcome opportunity to reconsider both the types that might be expected in the early to mid-fifth century, and how they might have been worn. When initially excavated, the recovery of these beads together with the disc brooches and tubular belt-fitting in the grave suggested an Anglo-Saxon rather than Roman date. A detailed study in 2019 by the present author indicated that the two groups showed features normally associated with the earliest ‘Anglo-Saxon’ bead traditions with tantalising hints that a mid-fifth-century date might be possible. The radiocarbon dating work that has now been completed has produced a posterior dating estimate of cal. a.d. 410–430 for the adult 6126 and one of cal. a.d. 415–435 for the infant 6125 (see Table 2). Both of these dates relate to the 68% probability interval and have been calibrated according to Model 1. As discussed in the paper, calibration via Model 2 could move these estimates three decades later. In either case there can be no doubt that what we are looking at are bead strings that were being used and worn in the early to mid-fifth century.

This reconsideration of the beads in Section 4.2 of the Supplementary Information will look first at the beads from a typological viewpoint and then move on to a consideration of how they were being worn in the grave by the adult woman 6126. Both show interesting differences to practices that can be considered ‘Roman’, and this will be considered in the concluding part.

Discussion of Stanwick and post-Roman Britain in light of the new dating evidence

The dating evidence we have presented requires further discussion of late and post-Roman burial practices, the re-dating of some categories of fifth-century material culture and the use of new-style material culture in fifth-century Northamptonshire in the context of the continuities and reconfigurations of the long-standing settlements at and around Stanwick in the late fourth and early fifth centuries.

Where were the fifth-century dead buried?

The 103 sets of human remains recovered from across the site witness the variety of ways people in the Roman period buried their dead. Although choice of burial location narrowed at Stanwick in the very late/immediate post-Roman period, when most of the dead seem to have been buried in or near the no-longer elegant villa building, a few corpses were interred elsewhere — the man with the stone in his mouth [6153] was buried at some distance from others of the period’s dead at the edge of the abandoned cemetery, and another individual’s grave was dug into a prehistoric ring ditch [6138]. The continued variety of burial placement at Stanwick in the post-Roman period reminds us that just as there was no single way of death in the Roman period,Footnote 91 there was no single way of death in the early decades of the fifth century. The post-400 burials at Stanwick underscore the fact that the period’s dead will be found in various contexts, some traditional, others not.

For example, in the first half of the fifth century, many communities ceased placing their dead in cemeteries that had been used for generations. Indeed, the abandonment of organised late Roman cemeteries is thought to be a feature of the period. A number of sites where radiocarbon dates have been acquired — Queenford Farm, near Dorchester-on-Thames; Lynch Farm, near Peterborough; Lankhills, just outside Winchester; and Horcott Quarry, in Gloucestershire — provide evidence that long-standing cemeteries did, indeed, go out of use around the end of the fourth century (Supplementary Figs S6–S10).Footnote 92 It is hardly surprising, given that Stanwick’s cemetery had probably gone out of use by the time the winged corridor villa was built shortly after a.d. 375–378 (94% probable),Footnote 93 that people living there in the early post-Roman period were no more inclined to bury their dead in the cemetery than people at these other places. Still, radiocarbon work undertaken at a handful of other Romano-British cemeteries has shown that some fifth-century families continued to lay their dead to rest in long-standing cemeteries. Radiocarbon dating at Roman-period cemeteries at Cannington (Somerset), Wasperton (Warwickshire) and Bainesse (North Yorkshire) has shown that burial carried on in all these cemeteries into the early medieval period (Supplementary Figs S11–S13).Footnote 94 Before we scientifically dated remains in Stanwick’s unenclosed cemetery, we believed that this might be the case at Stanwick as well, but our work only turned up one late, and quite exceptional burial at the edge of the cemetery, rather than evidence for the continued use of the cemetery into the fifth century by the local community. Clearly, without radiocarbon dating researchers cannot say which late-Roman cemeteries persisted and which were abandoned. There is also the very real possibility that a few ‘Anglo-Saxon’ cemeteries were actually founded in the immediate post-Roman period. If such cemeteries do exist, their proposed fifth-century dating can only be confirmed through scientific dating programmes.

Similarly, it was not unreasonable to believe that the woman and dog in Stanwick’s cist burials were contemporary with the post-Roman burials nearby. Indeed, that is how they had been phased before our work, which determined that the two had probably lived at Stanwick just before or just after the building of the aisled hall. Once again, our findings make clear the absolute necessity of scientific dating both to date Roman-period burials without datable grave goods and for the disambiguation of Roman and post-Roman burials, a point recently made as well by both James Gerrard and Paul Booth.Footnote 95

Burial in and along boundary lines and ditches, common not only at Stanwick but in many other places in the Roman period, was another practice that, although of very long standing, is often thought to have faded away after 400. Only 23 such burials dating to the early medieval period have been identified, all belong to the sixth century or later, and all are considered ‘deviant’ rather than normative.Footnote 96 They look, therefore, to be unrelated to pre-400 mortuary practices. Still, few of the hundreds of boundary burials assumed to be Roman have been radiocarbon dated, and fifth-century examples may be lurking among them. Indeed, groups of graves dated through radiocarbon dating to the post-Roman period have been found in close proximity to and aligned along Roman-period boundary ditches, such as a group of burials at Horcott Quarry (Supplementary Fig. S14),Footnote 97 and Bancroft, in Buckinghamshire (Fig. S14).Footnote 98 These burials, however, unlike standard Roman-period boundary burials, were placed in graves dug perpendicular to boundary features rather than parallel to them, so it is unclear whether they represent a new tradition, echo older ones, or both. Still, the proximity and alignment of these early post-Roman grave groups suggest that boundaries and the bodies of the dead continued to be linked conceptually in some communities, and that this may be another place to look for the fifth-century dead.

The post-Roman ‘Group E’ burials found in and around Stanwick’s late villa building and its enclosure represent a less traditional Romano-British practice, but they fit into a relatively common category of post-400 burials — small groups of dead (usually fewer than ten) interred in close proximity to defunct Roman buildings. In Northamptonshire alone, eight such post-400 burial sites have been identified — at Borough Hill, Bozeat, Brixworth, Castor (Mill Hill), Chipping Warden, Piddington and Redlands Farm, as well as at Stanwick.Footnote 99 Tyler Bell has noted the dating issues associated with burials in and around Roman rural buildings as well as their wide date ranges, but he argues that the majority belong to the sixth and seventh centuries.Footnote 100 There are, however, a handful of Roman rural sites besides Stanwick, for which there is radiocarbon confirmation for burials taking place in the early post-Roman period — Bradley Hill, Somerton (Somerset) (Supplementary Fig. S15),Footnote 101 Henley Wood, Yatton (Somerset) (Supplementary Fig. S16),Footnote 102 and probably Bainesse Farm, Catterick (site 10) (North Yorkshire) (Supplementary Fig. S17).Footnote 103 So, although the burials at many of these sites fit comfortably into Tony Wilmott’s characterisation of both ‘no longer Roman’ and ‘non-Roman in character’,Footnote 104 not all do. Indeed, given their radiocarbon dates, all but one of the burials in Stanwick’s ‘Group E’ are probably better described as ‘Roman in character’ and should be viewed as representing a final Romano-British phase of activity on the site.

The context of the Group E burials remains interpretive, with the key question being whether they were contemporary with the latest phase of occupation of the villa or followed after its abandonment. Certainly the villa was in decline, and many parts (such as the aisled hall) were probably ruinous. But the evidence for ovens and post-holes in the rooms of the later fourth-century extensions to the villa (and the siting of most of the burials around the outside of the courtyard wall) suggests occupation may still have continued in those areas.Footnote 105

In either case, burial in the earlier fifth century in and around such an obvious Roman-period structure was probably a conscious act, similar to the seemingly deliberate underscoring of romanitas expressed through material culture and choice of burial site by a small, high-status post-Roman burial community at Dyke Hills, in Oxfordshire.Footnote 106 Placing the fifth-century burials at Stanwick may have made a strong statement about the status of the people living in or near the site and their relationship to it, just as the selecting of a prominent earthwork for a group of high-status burials with Roman military connections at Dyke Hills may have been in deliberate contrast with those interred in the nearby Queenford Farm cemetery.Footnote 107

At Stanwick we can see a clear divide between the group of burials associated with the immediate post-Roman phase of the villa buildings in the fifth century and the single mid-Saxon inhumation. This suggests two distinct episodes (and two different practices) rather than a continuum. Unlike the fifth-century people burying their dead around the villa site, by the mid-Saxon period those burying their dead around Roman buildings in the countryside probably had neither direct connection with their use nor handed-down memories of the building and its occupants.

As we have seen, Stanwick’s post-Roman burial community includes the woman and infant in ‘Group E’ who shared a grave [6125, 6126], and whose burials were accompanied by strings of beads and disc brooches. Because of the beads and brooches, these individuals were initially identified as ‘Anglo-Saxon’. Hilary Cool’s re-evaluation of the beads, however, opens up the possibility that the beads may be dated earlier than originally thought. The woman’s disc brooches, too, are early. Although this brooch type was not used in the period before 400, the ring-and-dot punched and Quoit Brooch Style embellishments on a number of them, including one of the Stanwick brooches, seemed to have developed out of Romano-British decorative styles and craft techniques. Some of these disc brooches, moreover, based on the assemblages of grave goods in which they were found, date to the first half of the fifth century. Indeed, a number are associated with metalwork that is more accurately described as post-Roman than ‘Anglo-Saxon’: in particular, those found with late Roman belt fittings and objects decorated in the Quoit Brooch style.Footnote 108 Given the radiocarbon dates for both the woman and the infant at Stanwick, which probably place their deaths in the early to mid-fifth century, the woman could either be an early adopter of new-style material culture developing in Britain after the collapse of Roman-style production, or an immigrant new to Britain. Whatever their natal identity, though, the two were buried alongside people who probably had their roots in the final phase of the Roman-period settlement at Stanwick.

The fifth-century burial rite at Stanwick

The dead making up Group E were not only placed in a novel burial location, but they may have been buried following a relatively new burial rite. Burial 6126 is the only unambiguously clothed burial from the site. Clothed burial may have occurred earlier but not been recognised due to the absence of metal fittings in third- and fourth-century costume. Three burials [6109, 6139 and an undated inhumation 6073] were each accompanied by one or two bracelets, which may indicate they were buried clothed (see Cool, Supplementary Information 4.2).Footnote 109 An infant (phased as late third-century to early/mid-fourth-century in date) was accompanied by a pierced animal canine tooth, probably an amulet. Apart from these, no items of personal adornment were recovered from earlier burials, and while three of the Group E burials [6126, 6132, 6140] were accompanied by iron implements, this was not the case for any other pre-fifth-century burials. Swift notes that the usual fourth-century burial rite was inhumation, unclothed and probably in a winding sheet. If dress accessories or items of personal adornment were present, they were placed in the grave rather than worn on the body.Footnote 110

When late Romano-British clothed burials with dress accessories worn on the body have been encountered, explanations based on the supposed ethnicity of the dead are often offered, as for example by Clarke for two groups of ‘intrusive’ clothed burials at Lankhills.Footnote 111 Strontium and oxygen isotope assessment of the group that Clarke argued were Pannonians did support a non-British origin, but the diversity of their origins did not support his suggestion that they came from a single point of origin.Footnote 112 Isotope work following further excavations at Lankhills has taken the case further.Footnote 113 Most of the burials meeting Clarke’s intrusive group criteria ‘appear to be resolutely local in origin’ and most of the individuals with ‘exotic’ isotope signatures had ‘generally unremarkable grave assemblages’.Footnote 114 The results demonstrate the diverse origins of the late Roman population buried in Winchester, but do not support a close relationship between their origins and the rites used to inter them.

These findings are further supported by Guy Halsall’s work on the late Roman clothed and weapon-accompanied burial rite appearing at this time in northern Gaul. Halsall argued that these burials, in contrast to earlier arguments, should be seen as a ‘fundamentally late “Roman”’ provincial development, with prominent families ‘making statements of local prestige’ intended to ‘recreate, underline or maintain’ a social reality in the context of declining Roman control and ‘insecure tenure of local power’.Footnote 115 We are now coming to understand that burials like these dated to the early fifth century in Britain should be interpreted as late Roman rather than intrusive and barbarian.Footnote 116

If we accept that clothed burial and the deposition of grave goods represent a display of portable wealth as part of the funeral process, these practices began taking place at Stanwick at the time when the late fourth-century villa was either in steep decline or had been abandoned, and when the lifestyle represented by this late burial activity contrasted dramatically from what it would have been in c. 370 in a building with mosaics, underfloor heating and a bath suite. The location of Group E close to the villa may be significant, as may the construction of the stone structure housing burial 6126. Was this a way of demonstrating continuing status and ownership by the occupants of the villa despite their inability or lack of desire to maintain the building in its former grand state?

The male burial 6132 should probably not be regarded as a ‘weapon burial’: a spear is as likely to represent the high-status activity of hunting as to have any military implications. The knives (found with burials 6126 and 6140) are everyday tools carried by men or women. This marks a difference from the weapon-accompanied burials in northern Gaul.

Group E also includes infant burials, both inserted into an earlier adult burial [6125] and alone [6131]. There is a suggestion that there may have been an increase in infants buried in formal urban cemeteries in the fourth century,Footnote 117 and Group E may reflect this late Roman trend of affording infants burial in the same locations as adults. In contrast, most fifth- and sixth-century burial communities considered ‘Anglo-Saxon’ did not bury neonates in communal cemeteries.Footnote 118

Although it would be unwise to extrapolate too far from such a small group of dated burials, it can be argued that Group E has a distinct character which may offer some hints for identifying other fifth-century burial groups on Romano-British rural sites. They show three characteristics: a new location, close to an occupied building; some (but not all) of the burials were clothed and/or accompanied by grave goods; and the burial group includes infants, both in separate graves and inserted into adult graves.

Another lesson from Stanwick is provided by the fact that there are clear chronological divisions between three sets of burials found near the late Roman villa building — ‘Group A’ burials, which date to around the time of the building of the aisled hall; ‘Group E’ burials, from the early fifth century; and a single mid-Saxon inhumation [6170]. Our scientific dating reveals three distinct episodes of burial near the site of the villa, governed by three different sets of burial practices.

These findings at Stanwick should encourage us to consider radiocarbon dating other groups of burials recovered from Roman villas. At Orpington in Kent, for example, although grave goods associated with a number of burials date some of them to the sixth and seventh centuries, a few graves may well be early post-Roman, in particular the graves of women with both ring-and-dot decorated disc brooches and Quoit Brooch style metalwork.Footnote 119 Those buried at Orpington in the mid-Saxon period were unlikely to have been connected to the people who once occupied the villa, but those buried in the earliest phase may well have been. Scientific dating of skeletons recovered near defunct Roman buildings, as done at Stanwick, might allow us to identify other early fifth-century individuals who belonged to the same post-Roman milieu and to refine the dating of the material culture buried with them.

Rethinking the chronology of fifth-century material culture

Despite his death in the post-Roman period, the man from ‘Group E’ buried within the villa building [6127] was probably accompanied in the ground by a nail-cleaner strap-end <95512>, a not uncommon find on fourth-century villa sites, and an object that likely signalled high social status.Footnote 120 Its burial in a post-Roman grave suggests that even some years after the Roman state’s withdrawal from Britain, objects like this and the meanings they signalled continued to resonate for those burying at Stanwick. Burial F [6138], also dating to the post-Roman period, probably included a bracelet and perhaps hobnail shoes, items that had long accompanied the dead in Britain. These two graves thus hint at the continuation of Roman-period funerary practices in the early post-Roman period. Some of the other burials in ‘Group E’, however, which may fall later rather than earlier in the burial episode, were accompanied by material culture only developing in Britain after 400. Wardle has found the closest parallels to the tubular belt fitting from Stanwick in two recovered at Mucking, in Essex. Evison dated the Mucking examples broadly to the fifth century and assigned them an insular origin.Footnote 121 Model 1 suggests that the Stanwick belt fitting was almost certainly in the ground by c. 430, although the possibility of a small amount of fish in the woman’s diet (Model 2) could shift the dating of this burial to the middle of the fifth century. This type of belt fitting, however, may have been in use in the early fifth century. The spear, the disc brooches and the belt fittings accompanying Burials 6123, 6125 and 6126 were not objects worn on the body or placed in graves in the fourth century, and the beads and belt fittings are generally dated c. 450 at the earliest. The radiocarbon dating at Stanwick, however, suggests that the traditional start date of 450, proposed by John Hines and others for these classes of objects,Footnote 122 may need to be shifted a decade or two earlier. The same may apply to the first appearance of disc brooches and the beads found in two of Stanwick’s post-400 burials.

Changes in and around Stanwick in the late and post-Roman period

There are indications that a number of small agricultural settlements in the Raunds Area, particularly on the clay plateau, were abandoned in the late Roman period, and Stephen Parry argues that the reduced extent of manuring scatters could suggest there was also a decline in grain production.Footnote 123 However, recent work by Lisa Lodwick on the isotopes from cereal grain indicates that the reduction in manuring scatters may relate to the introduction of more extensive cereal-growing operations rather than a contraction of agricultural production.Footnote 124 Data gathered from the Raunds Area Project led Parry to suggest that developments in the area hint at a reduction in the number of settlements on the clay uplands coupled with the ‘aggrandisement’ of a handful of powerful landowners and the formation of a few large estates at the expense of more independent holdings.Footnote 125 Data gathered from the New Visions of the Countryside of Roman Britain project support this interpretation, identifying the region between Gloucester and Irchester (the latter only 8 km from Stanwick) as an area with unusual signs of wealth in the late fourth century, likely centred on villa estates.Footnote 126 The proprietors at Stanwick, given the late date of the final construction phase of the villa building and the site’s large numbers of late fourth-century coins, could have been one of the movers behind such a reorganisation, and perhaps were among those bringing it about.

The rest of the settlement shows clear changes accompanying the building of the later fourth-century extensions to the villa, with some of the site’s building groups falling out of use. While some of the secondary buildings around the villa seem to have been removed, new buildings appeared inside the freshly laid-out courtyard, and a new corn dryer was built north of the villa. The aisled hall, with the occupants of its cross range removed to the new part of the villa, could have provided accommodation for the workforce as well as space for agricultural activities. It is unclear whether the overall population declined, but there is a decline in the number of occupied building complexes and the relationship between villa and village may have changed. Clearing the building groups from between the villa and the road might have enhanced the owners’ view of the landscape — or ensured a clear view of the prestigious new building from the road.

The fact that the villa’s elaborate mosaic floors were being installed no earlier than 375 points to an unusually late date for the building of such a structure. The villa must have served as a high-status residence for at least a few years, because some small improvements were made after the initial laying of the floors;Footnote 127 but at some point, the traditional elite lifeways that had long taken place at villas like this ceased. Stanwick, nonetheless, remained an important place for at least a few years, probably controlled by an important person, because it continued to attract large (for the period) amounts of copper-alloy and silver coinage. Of the seven late-issue silver siliquae at Stanwick, four show signs of light clipping,Footnote 128 a phenomenon probably taking place after 400, indeed perhaps after c. 406.Footnote 129 This in turn suggests that silver currency continued to be used in some way at the villa for some years after the withdrawal of the Roman state. Like the major reconfiguring of the villa building for more pragmatic uses, the coins hint that a powerful person or group remained in charge of the site, at least into the first decade of the fifth century.

Although it is difficult to date the end of the villa’s life as an elite building, there is certainly evidence for its continued use after this change. It is impossible to know how long after the installation of two of the villa’s mosaic floors (coin-dated no earlier than 375) that these changes took place, but the history of these floors suggests that in its final years the kind of life once led in the villa’s elaborately decorated rooms was either no longer sustainable or no longer desirable. Post-holes were cut through the mosaic floors of the southern range, corridor and southern pavilion. These were related to either ad hoc repairs to the fabric of the building or changes in the use of the rooms. A dumbbell-shaped oven was also cut through the largest of the villa’s mosaics, and hearths were established in the hypocausted room and in a room in the remodelled cross range of the former aisled hall, where floors made up of flagstones had been partially removed. Some of the fixtures in the bath suite seem to have been dismantled, perhaps for recycling, and an oven structure was inserted into the space.Footnote 130 This may have taken place before one of the men in ‘Group E’ [6127] was buried in the north end of the aisled hall, possibly after the roof had collapsed. This grave was some distance from the focus of late activity, and it seems likely that this part of the villa was abandoned and declined rapidly while the front of the building remained in use. This burial most likely took place, according to our radiocarbon dating, sometime in the early to mid-fifth century. Most of the other ‘Group E’ burials were placed along the outer side of the courtyard wall, perhaps to maintain the appropriate distance and distinction between the living and the dead.

Beyond the villa complex a few features are assigned to this late period on stratigraphic grounds. They are mostly in a restricted area north and east of the villa courtyard and include a small (7.6 m by 2.5 m) post-built rectilinear building. A sub-rectangular structure or small enclosure was defined by a trench with stake-holes in its base; daub from the fill suggests it may have had a wattle-and-daub superstructure. Several ditches possibly partly defined enclosures. No sunken-featured buildings were found at Stanwick, unlike at Redlands Farm to its south,Footnote 131 and West CottonFootnote 132 and Warth Park, Raunds to the north.Footnote 133

The failure of Stanwick in the fifth century is paralleled at other settlements in the area. Despite the difficulties with dating, Parry identified a change in preference towards locations in the river or stream valleys, although he suggests there is no evidence for a widespread retreat from the clay plateau, which has been identified as a trend by Rippon et al. Footnote 134 As at Stanwick, pottery scatters at some sites in the river valley show a shift in occupation to locations a short distance from the Romano-British settlement.Footnote 135 The roadside settlement of Higham Ferrers was ‘no longer functioning as a small town by the end of the fourth century’, and when early Saxon settlement there started in the mid-fifth century, the ‘incomers showed no interest in the relict Romano-British infrastructure’.Footnote 136 This lack of interest is also seen at Stanwick, where both the villa proprietors and the agricultural community that supported them abandoned the settlement. Our ‘Group E’, together with the occupants of the aberrant graves in the cemetery and the ring-ditch, represent some of the last inhabitants of this Romano-British settlement.

Conclusions

The use of radiocarbon dating and chronological modelling to provide accurate and precise chronologies in the Roman and post-Roman periods is challenging: a few decades make a substantive difference to archaeological narratives. Clearly, scientific techniques are advancing at pace. High-resolution single-year calibration has only recently become available for part of the period (a.d. 290–a.d. 486),Footnote 137 which means that it is essential to recalibrate and remodel all radiocarbon dates used in archaeological discussion. IntCal20 shifts date ranges by up to half a generation,Footnote 138 in comparison to IntCal13,Footnote 139 in the period where single-year calibration data are available (see Supplementary Information 5).

Further refinements may be expected in this period as additional data are measured and mathematical techniques of curve compilation improve.Footnote 140 Clearly much more substantial improvements can be expected in the earlier Roman period (before a.d. 290), for which single-year calibration data are only just being measured,Footnote 141 and where there may be evidence of significant regional offsets in atmospheric 14C across the northern hemisphere.Footnote 142 The need for recalibration and remodelling will continue (see Supplementary Information 1 and 3).

The potential input of marine and freshwater fish in diet is another complication in accurate calibration and modelling of 14C measurements on human bone. Our understanding of both marine and, even more, freshwater 14C reservoirs ranges from patchy to practically non-existent across the Roman world,Footnote 143 and the latter, in particular, are notoriously variable.Footnote 144 Interpreting dietary proportions from stable isotopic values is complex and hazardous, as many of the inputs into the modelling are imperfectly understood (see Supplementary Information 3), and the baseline values for different dietary sources may overlap. It is particularly difficult to resolve small dietary components accurately.