Introduction

People diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (SSDs) are often prescribed antipsychotic medication for at least 1 year to prevent relapse after achieving symptomatic remission. National guidelines are inconclusive as to which antipsychotic drug should be preferred (reviewed in Correll et al., Reference Correll, Martin, Patel, Benson, Goulding, Kern-Sliwa, Joshi, Schiller and Kim2022), since differences in efficacy are regarded to be small (Huhn et al., Reference Huhn, Nikolakopoulou, Schneider-Thoma, Krause, Samara, Peter, Arndt, Bäckers, Rothe, Cipriani, Davis, Salanti and Leucht2019; Schneider-Thoma et al., Reference Schneider-Thoma, Chalkou, Dörries, Bighelli, Ceraso, Huhn, Siafis, Davis, Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti and Leucht2022). Yet, an important reason to prefer one type of medication over another, could be its potential influence on cognitive functioning. Impairments in cognitive functioning are already present very early in the disease and are subject to great variability in those with a first-episode psychosis (FEP) (Catalan et al., Reference Catalan, McCutcheon, Aymerich, Pedruzo, Radua, Rodríguez, Salazar de Pablo, Pacho, Pérez, Solmi, McGuire, Giuliano, Stone, Murray, Gonzalez-Torres and Fusar-Poli2024; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cernvall, Borg, Plavén-Sigray, Larsson, Erhardt, Sellgren, Fatouros-Bergman and Cervenka2024).

Despite extensive research (Baldez et al., Reference Baldez, Biazus, Rabelo-da-Ponte, Nogaro, Martins, Kunz and Czepielewski2021; Baldez et al., Reference Baldez, Biazus, Rabelo-da-Ponte, Nogaro, Martins, Signori, Gnielka, Passos, Czepielewski and Kunz2025; McCutcheon, Keefe, McGuire, Marquand et al., Reference McCutcheon, Keefe, McGuire and Marquand2025; Mishara & Goldberg, Reference Mishara and Goldberg2004), the evidence regarding the effects of antipsychotic medication on cognition remains inconclusive. Large studies performed in FEP (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Galderisi, Weiser, Werbeloff, Fleischhacker, Keefe, Boter, Keet, Prelipceanu, Rybakowski, Libiger, Hummer, Dollfus, López-Ibor, Hranov, Gaebel, Peuskens, Lindefors, Riecher-Rössler and Kahn2009) and long-term schizophrenia (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Bilder, Davis, Harvey, Palmer, Gold, Meltzer, Green, Capuano, Stroup, McEvoy, Swartz, Rosenheck, Perkins, Davis, Hsiao and Lieberman2007) suggest that treatment with antipsychotic medication can have a positive effect on cognitive functioning in SSD (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Xie, Yuan, Cheng, Han, Yang, Yu and Shi2020). In these studies, improvements in cognition were shown to be associated with symptom reduction and better general functioning (Helldin, Mohn, Olsson, & Hjärthag, Reference Helldin, Mohn, Olsson and Hjärthag2020; Johansson, Hjärthag, & Helldin, Reference Johansson, Hjärthag and Helldin2020; Lindgren, Holm, Kieseppä, & Suvisaari, Reference Lindgren, Holm, Kieseppä and Suvisaari2020; Santesteban-Echarri et al., Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, González-Blanch, McGorry, Gleeson and Alvarez-Jimenez2017). Antipsychotics may therefore indirectly contribute to improve cognitive functioning by reducing psychotic symptoms and increasing general functioning. Achieving symptomatic remission with antipsychotics could also be important for cognitive recovery, as it minimizes the confounding effects of psychotic symptoms (e.g. hallucinations, disorganization). Studying a population of individuals in symptomatic remission therefore allows for a more accurate assessment of cognitive abilities in people with FEP.

On the other hand, antipsychotic maintenance therapy has also been related to negative effects on cognitive functioning, especially at high doses (Allott et al., Reference Allott, Yuen, Baldwin, O’Donoghue, Fornito, Chopra, Nelson, Graham, Kerr, Proffitt, Ratheesh, Alvarez-Jimenez, Harrigan, Brown, Thompson, Pantelis, Berk, McGorry, Francey and Wood2023; Ballesteros et al., Reference Ballesteros, Sánchez-Torres, López-Ilundain, Cabrera, Lobo, González-Pinto, Díaz-Caneja, Corripio, Vieta, De La Serna, Bobes, Usall, Contreras, Lorente-Omeñaca, Mezquida, Bernardo, Cuesta, Bioque, Amoretti and Balanza-Martinez2018; Élie et al., Reference Élie, Poirier, Chianetta, Durand, Grégoire and Grignon2010; Husa et al., Reference Husa, Moilanen, Murray, Marttila, Haapea, Rannikko, Barnett, Jones, Isohanni, Remes, Koponen, Miettunen and Jääskeläinen2017; Rehse et al., Reference Rehse, Bartolovic, Baum, Richter, Weisbrod and Roesch-Ely2016; Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer, & Zald, Reference Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer and Zald2007). Previous studies commonly assessed the effects of antipsychotics on cognition by relating dose equivalents to cognitive functioning (Haddad et al., Reference Haddad, Salameh, Sacre, Clément and Calvet2023), by comparing two different drugs (i.e. olanzapine vs. haloperidol) (Désaméricq et al., Reference Désaméricq, Schurhoff, Meary, Szöke, Macquin-Mavier, Bachoud-Lévi and Maison2014) or by comparing medication types (i.e. first vs. second generation) (Baldez et al., Reference Baldez, Biazus, Rabelo-da-Ponte, Nogaro, Martins, Signori, Gnielka, Passos, Czepielewski and Kunz2025; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Levander, Kjaersdam Telléus, Jensen, Østergaard Christensen and Leucht2015). Since dopamine receptor binding may play an important role in cognitive dysfunction (Nørbak-Emig et al., Reference Nørbak-Emig, Ebdrup, Fagerlund, Svarer, Rasmussen, Friberg, Allerup, Rostrup, Pinborg and Glenthøj2016; Sala-Bayo et al., Reference Sala-Bayo, Fiddian, Nilsson, Hervig, McKenzie, Mareschi, Boulos, Zhukovsky, Nicholson, Dalley, Alsiö and Robbins2020), classifying antipsychotic medication based on dopamine D2 receptor affinity (i.e. high D2 affinity antagonists, low D2 affinity antagonists, or partial agonists) may be more useful than classification based on generations of antipsychotics (Zhou, Nutt, & Davies, Reference Zhou, Nutt and Davies2022).

Antipsychotics all share the same mechanism of dopamine D2 receptor blockade, yet they vary significantly in their receptor affinity. This dopaminergic binding property has been implicated in the effect of antipsychotics on cognitive functioning (Allott et al., Reference Allott, Yuen, Baldwin, O’Donoghue, Fornito, Chopra, Nelson, Graham, Kerr, Proffitt, Ratheesh, Alvarez-Jimenez, Harrigan, Brown, Thompson, Pantelis, Berk, McGorry, Francey and Wood2023, Reference Allott, Chopra, Rogers, Dauvermann and Clark2024; Volkow et al., Reference Volkow, Gur, Wang, Fowler, Moberg, Ding, Hitzemann, Smith and Logan1998; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yeh, Chiu, Lee, Chen, Lee and Jeffries2004). Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in several brain circuits involved in motivation and cognition, such as the reward system, memory, and attention (Goldman-Rakic, Reference Goldman-Rakic1998). In healthy individuals, administrating antipsychotics results in impaired sustained attention, processing speed, and working memory. This effect was related to the extent of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Howes, Turkheimer, Kim, Jeong, Kim, Lee, Jang, Shin, Kapur and Kwon2013; Saeedi, Remington, & Christensen, Reference Saeedi, Remington and Christensen2006).

While dopamine D2 receptor occupancy, to a certain extent, is effective in treating psychotic symptoms (Uchida et al., Reference Uchida, Takeuchi, Graff-Guerrero, Suzuki, Watanabe and Mamo2011), exceeding the optimal dopamine D2 receptor occupancy may disproportionally worsen cognitive impairment. Indeed, high dopamine D2 receptor occupancy, as measured in positron emission tomography (PET) studies, has been associated with more impaired cognitive functioning in individuals with SSD (Sakurai et al., Reference Sakurai, Bies, Stroup, Keefe, Rajji, Suzuki, Mamo, Pollock, Watanabe, Mimura and Uchida2013; Uchida et al., Reference Uchida, Rajji, Mulsant, Kapur, Pollock, Graff-Guerrero, Menon and Mamo2009) and subjective worsening of cognitive functioning (De Haan et al., Reference De Haan, Lavalaye, Linszen, Dingemans and Booij2000, Reference De Haan, van Bruggen, Lavalaye, Booij, Dingemans and Linszen2003). Therefore, we may gain a better understanding of the impact of antipsychotics on cognitive functioning by focusing on D2 receptor blockade, in addition to dosage. The D2 receptor occupancy of eight antipsychotics can be estimated based on antipsychotic type and dose using meta-analytically derived formulas (Lako et al., Reference Lako, van den Heuvel, Knegtering, Bruggeman and Taxis2013). Alternatively, assessing the interaction between antipsychotic doses and categorization of dopamine affinity is possible for all antipsychotics, and may provide comparable insights. These approaches do not require PET scanning and therefore allow evaluation in large samples. Combining both approaches, taking into account occupancy, affinity, and dose of antipsychotic medication, may provide unique and additional insights into the existing literature.

The current study aimed to examine the association between cognitive functioning and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy, dopamine D2 receptor affinity, and antipsychotic daily dose in a large FEP population in symptomatic remission (i.e. with minimal psychotic symptoms). The current study design avoids two factors that often confound similar studies. First, cognitive functioning is related to (psychotic) symptom severity and general functioning. It is therefore important to study people in symptomatic remission from an FEP, to avoid confounding influences of both active psychotic symptoms and the associated (long-term) treatment thereof. Second, as we analyzed users of different medication types in a non-randomized context, differences in baseline functioning or other characteristics could become confounding factors. To prevent this bias, we used inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) as a statistical solution for patient matching to balance clinical and sociodemographic characteristics between the dopamine D2 receptor affinity groups.

Methods and materials

Participants

Data were used from the ongoing Handling Antipsychotic Medication: Long-term Evaluation of Targeted Treatment (HAMLETT) study (Begemann et al., Reference Begemann, Thompson, Veling, Gangadin, Geraets, van ‘t Hag, Müller-Kuperus, Oomen, Voppel, van der Gaag, Kikkert, Van Os, Smit, Knegtering, Wiersma, Stouten, Gijsman, Wunderink, Staring and Sommer2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and study procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethics committee of the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands (EudraCT number: 2017-002406-12). Patients were recruited from 26 outpatient care centers in The Netherlands. Details regarding recruitment and study procedures are described by Begemann et al. (Reference Begemann, Thompson, Veling, Gangadin, Geraets, van ‘t Hag, Müller-Kuperus, Oomen, Voppel, van der Gaag, Kikkert, Van Os, Smit, Knegtering, Wiersma, Stouten, Gijsman, Wunderink, Staring and Sommer2020). The current study included data from 278 participants aged between 16 and 60 years old who were between 3 and 6 months in symptomatic remission of their first psychotic episode and used antipsychotic medication. Demographic data were collected for all participants with the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (Andreasen, Reference Andreasen1992) (Table 1). Severity of symptomatology was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987).

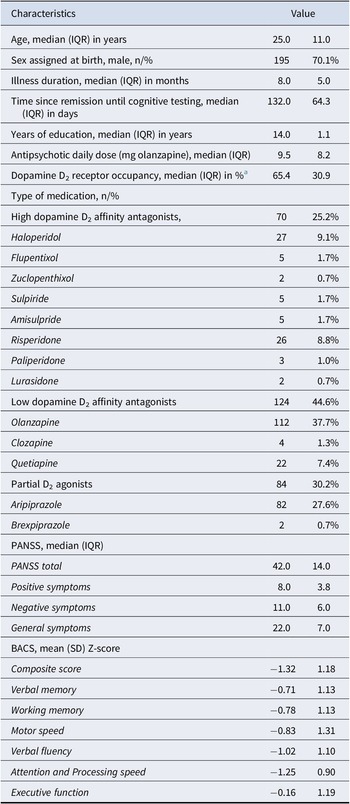

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample (n = 278)

Abbreviations: BACS: Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; IQR: Interquartile Range; DDD: Defined Daily Doses; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD: Standard Deviation.

a D2 receptor occupancy could not be estimated for n = 16 users of flupentixol, zuclopenthixol, sulpiride, lurasidone, and brexipiprazole.

Cognitive functioning

Cognitive functioning was assessed using the Dutch version of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS; Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Goldberg, Harvey, Gold, Poe and Coughenour2004). The test consists of six subtests that assess different cognitive domains: list learning (verbal memory), digit sequencing task (working memory), token motor task (motor speed), category instances and controlled oral word association test (verbal fluency), symbol coding (attention and processing speed), and Tower of London (executive function). Performances on the six subtests of the BACS were standardized by creating z-scores adjusted for sex at birth (hereafter referred to as sex) and age using norms of Keefe et al. (Reference Keefe, Goldberg, Harvey, Gold, Poe and Coughenour2004), which were subsequently averaged to create a single composite z-score reflecting global cognitive functioning. Participants missing the BACS assessment (n = 40) or with more than two missing cognitive subscores (n = 1) were excluded from analysis. For participants with ≤2 missing subscores, scores were replaced by the corresponding population mean for that specific domain (n = 9). Finally, three participants (n = 3) were excluded due to outliers on the BACS assessment. This included one participant with intellectual disabilities, one participant with dyslexia and one participant who was not a Dutch native speaker (due to a language barrier).

Medication use

Use of antipsychotic medication in this study was based on self-reports combined with individual data from the Dutch Foundation for Pharmaceutical Statistics. For a more accurate measure of medication use, self-reports were used as a primary source and were confirmed with the pharmacy records. The Dutch Foundation for Pharmaceutical Statistics collects dispensation data from 99% of community pharmacies in the Netherlands. Using a matching procedure, we received information on included participants concerning the date antipsychotic medication was handed out, including the generic name of the drug, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC5) classification, dose per unit (pills or injectables), total number of units prescribed, and daily dose. Data were matched using a pseudonym based on date of birth, name, sex, and postal code. Therefore, data were still available even when a patient collected medication at different pharmacies. As long as the pharmacy shared pseudonyms – which is the case in more than 90% of participating pharmacies, data were available.

Daily dose of antipsychotic medication was converted to olanzapine equivalents (mg/day) (Leucht et al., Reference Leucht, Crippa, Siafis, Patel, Orsini and Davis2020). Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy percentages were estimated based on published PET and SPECT results, following the meta-analytically derived formulas described by Lako et al. (Reference Lako, van den Heuvel, Knegtering, Bruggeman and Taxis2013). Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy could be calculated for amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and paliperidone users (91.3% of participants). Antipsychotics were further categorized into three groups based on their D2 receptor affinity: ‘high-affinity antagonists’ if the D2 binding affinity Ki < 10 (flupentixol, haloperidol, pimozide, risperidone, zuclopenthixol, sulpiride, paliperidone, penfluridol, amisulpride, and lurasidone); ‘low-affinity antagonists’ for Ki > 10 (olanzapine, clozapine, and quetiapine); and ‘partial D2 agonists’ for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine (Psychoactive Drug Screening Program Ki Database: https://pdsp.unc.edu/databases/kidb.php; Kaar, Natesan, McCutcheon, & Howes, Reference Kaar, Natesan, McCutcheon and Howes2020).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.3. Block-wise multiple regression analysis, with the BACS composite score as the dependent variable, was used to test several models. Residuals of the models were checked for normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. The assumption of multicollinearity among all independent variables was not violated (Variance Inflation Factor < 5).

First, the relation between the BACS composite and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy was sequentially tested with two models: (1) demographic characteristics (age, sex, and years of education) and symptom severity at testing (PANSS total score) and (2) dopamine D2 receptor occupancy added to model 1. Six subsequent exploratory analyses were performed using the same statistical approach for each cognitive domain.

Next, the relation between the BACS composite score and daily dose of antipsychotic in different groups of antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor affinity was tested with three models: (1) demographic characteristics (age, sex, and years of education), symptom severity at testing (PANSS total score), and daily antipsychotic dose (olanzapine equivalents, mg/day); (2) dopamine D2 receptor affinity group (low D2 receptor affinity; high D2 receptor affinity; partial D2 receptor agonists) added to model 1; and (3) the interaction between antipsychotic dose * dopamine D2 receptor affinity group added to model 2.

Since we analyzed all outcomes twice (dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and the interaction between antipsychotic dose and dopamine D2 affinity group), we applied a Bonferroni correction to the conventional α-level of 0.05, setting the threshold for statistical significance at 0.025 (0.05/2).

All regression analyses were corrected with IPTW to correct for bias by indication. IPTW was applied as a statistical solution for patient matching to balance potential clinical and sociodemographic differences between the dopamine D2 receptor affinity groups. These variables included age, sex, years of education, illness duration, PANSS subscores at testing, and antipsychotic dose at the time of remission in olanzapine equivalents.

Results

From a total of 287 participants with FEP, data on cognition and medication (type and dose) were sufficiently complete for subsequent analyses. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy could be estimated for 262 participants. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants had a mean age of 27.9 years (SD = 8.9, median = 25.0, interquartile range (IQR) = 11.0) and consisted of 83 females (29.9%) and 195 males (70.1%). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics per dopamine D2 affinity group are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

The final regression model (n = 262) testing the relation between the BACS composite score and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (corrected for demographics and symptom severity) explained 22.2% of the total variance in global cognitive functioning. Specifically, 18.7% of the variance was explained by the covariates age, sex, years of education, and symptom severity (F(4,257) = 14.80, p < 0.001), and an additional 3.5% was explained by the D2 receptor occupancy (F(1,256) = 11.58, p < 0.001). A higher dopamine D2 receptor occupancy was significantly related to lower global cognitive functioning (β = −0.18, p = 0.0008), as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1. The association between estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and (A) global cognitive functioning (BACS composite score); (B) attention and processing speed; and (C) verbal fluency.

Subsequent exploratory analyses for specific subdomains of cognitive functioning, corrected for demographics and symptom severity, demonstrated significant negative associations between dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and verbal fluency (β = −0.22, p = 0.0001) and attention and processing speed (β = −0.17, p = 0.003), as shown in Figure 1B,C. Detailed statistics on all regression models are provided in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

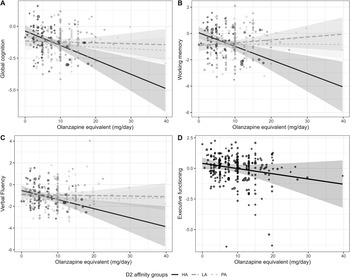

The final regression model testing the relation between the BACS composite score and the interaction between current daily antipsychotic dose and the different dopamine D2 receptor affinity groups, explained 26.9% of the total variance in global cognitive functioning. Specifically, 23.2% of the variance was explained by the covariates age, sex, years of education, and symptom severity (F(5,272) = 16.43, p < 0.001), and an additional 3.0% was explained by the interaction between antipsychotic dose * D2 receptor affinity (F(2,268) = 5.49, p = 0.005).

The interaction between daily antipsychotic dose and the different groups of antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor affinity was also significant for working memory (R2-change = 0.041, F(2,268) = 6.4, p = 0.002), but the effect for verbal fluency did not hold after correction for multiple testing (R2-change = 0.024, F = (2,268) = 3.59, p = 0.029) (Figure 2A–C). All interactions showed the same direction of effects (Figure 2A–C): Users of high-affinity antagonists showed a significantly stronger relationship between high daily antipsychotic dose and low global cognitive functioning, compared to users of low-affinity antagonists and partial agonists (all β > 0.40, all p < 0.025; Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). While executive functioning did not show a significant interaction effect, the association with current daily antipsychotic dose was statistically significant, irrespective of antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor affinity group (Figure 2D, β = −0.17, p = 0.0028). Detailed statistics of all regression models are presented in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Figure 2. The association between daily antipsychotic dose and (the interaction with) different groups of dopamine D2 receptor affinity (high affinity [HA]: continuous; low affinity [LA]: striped; partial agonists [PA]: dotted) with (A) global cognitive functioning (BACS composite score); (B) working memory; (C) verbal fluency; and (D) executive functioning.

Discussion

The current study examined the association between cognitive functioning and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy, dopamine D2 receptor affinity, and antipsychotic daily dose in 278 participants recently remitted from an FEP. Our results demonstrated that dopamine D2 receptor occupancy was negatively related to global cognitive functioning, verbal fluency, and attention and processing speed, indicating that a higher D2 receptor occupancy was related to lower cognitive functioning. In addition, the interaction between the current daily dose of antipsychotic and the different groups of antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor affinity was not only significant for global cognitive functioning, but also for working memory, and at the trend level for verbal fluency. Users of high-affinity antagonists (e.g. haloperidol, risperidone, amisulpride) showed a significantly stronger relationship between high daily antipsychotic dose and low global cognitive functioning, compared to users of low-affinity antagonists and partial agonists. While executive functioning did not show a significant interaction effect, lower executive functioning was related to higher daily antipsychotic doses, irrespective of antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor affinity.

The variance in global cognitive functioning in FEP is considerable (Catalan et al., Reference Catalan, McCutcheon, Aymerich, Pedruzo, Radua, Rodríguez, Salazar de Pablo, Pacho, Pérez, Solmi, McGuire, Giuliano, Stone, Murray, Gonzalez-Torres and Fusar-Poli2024), and generally poorly explained. Multiple studies have found that – even when combining demographic and clinical characteristics, including proxies of premorbid functioning – no more than 30% of the variance is typically accounted for (Amoretti et al., Reference Amoretti, Rabelo-da-Ponte, Rosa, Mezquida, Sánchez-Torres, Fraguas, Cabrera, Lobo, González-Pinto, Pina-Camacho, Corripio, Vieta, Torrent, de la Serna, Bergé, Bioque, Garriga, Serra, Cuesta and Bernardo2021; Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Sánchez-Torres, Cabrera, Bioque, Merchán-Naranjo, Corripio, González-Pinto, Lobo, Bombín, de la Serna, Sanjuan, Parellada, Saiz-Ruiz and Bernardo2015; González-Blanch et al., Reference González-Blanch, Crespo-Facorro, Álvarez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Pelayo-Terán, Pérez-Iglesias and Vázquez-Barquero2008; Lutgens, Lepage, Iyer, & Malla, Reference Lutgens, Lepage, Iyer and Malla2014). Other important predictors such as age, sex (Carruthers, Van Rheenen, Karantonis, & Rossell, Reference Carruthers, Van Rheenen, Karantonis and Rossell2022), negative symptom severity (Au-Yeung et al., Reference Au-Yeung, Penney, Rae, Carling, Lassman and Lepage2023), illness insight (Subotnik et al., Reference Subotnik, Ventura, Hellemann, Zito, Agee and Nuechterlein2020), and polygenic risk scores (Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, Tansey, Rai, Jones, Ripke, Chambert, Moran, McCarroll, Linden, Owen, O’Donovan, Walters and Zammit2016), individually explain less than 10% of the variance in neurocognitive functioning. For instance, Lutgens et al. (Reference Lutgens, Lepage, Iyer and Malla2014) found that socio-economic status uniquely explained only 4% of the variance in global cognitive functioning in a comparable sample of 269 participants with FEP (average global cognition z = −1.48) (Lutgens et al., Reference Lutgens, Lepage, Iyer and Malla2014). Given the substantial unexplained variance in cognitive functioning in FEP, and recognizing that cognitive impairment is significantly associated with social and occupational functioning, as well as quality of life (Cowman et al., Reference Cowman, Holleran, Lonergan, O’Connor, Birchwood and Donohoe2021; Fett et al., Reference Fett, Viechtbauer, Dominguez, Penn, van Os and Krabbendam2011; Tolman & Kurtz, Reference Tolman and Kurtz2012), the 3.5% of variance explained by D2 receptor occupancy in our study contributes a new piece of the puzzle and can be considered of clinical importance when selecting an antipsychotic drug. It is plausible that in samples with greater cognitive impairment, even stronger effects might emerge. Importantly, many factors, such as demographic and genetic background, cannot be targeted and modified to improve cognition, but the type and dose of medication are factors that can be considered when treating individuals with FEP.

While the association of cognitive functioning with antipsychotic dose and receptor affinity has been reported before (Baitz et al., Reference Baitz, Thornton, Procyshyn, Smith, MacEwan, Kopala, Barr, Lang and Honer2012; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Kumar, Pathak, Jacob, Venkatasubramanian, Varambally and Rao2022), their interactive effect in combination with D2 receptor occupancy in a large sample of people remitted from an FEP is new and suggests that antipsychotic medication may affect cognitive functioning via D2 receptor occupancy. In parallel to our current finding, our group recently observed more speech deviations (De Boer et al., Reference De Boer, Voppel, Brederoo, Wijnen and Sommer2020) and more severe negative symptoms (de Beer et al., Reference De Beer, Wijnen, Wouda, Koops, Gangadin, Veling, van Beveren, de Haan, Begemann and Sommer2024) in users of high dopamine D2 affinity antipsychotics compared to users of partial agonists or low-affinity antagonists, and previous research demonstrated a decline in cognitive functioning in individuals prescribed risperidone/paliperidone, both high dopamine D2 affinity antagonists (Allott et al., Reference Allott, Yuen, Baldwin, O’Donoghue, Fornito, Chopra, Nelson, Graham, Kerr, Proffitt, Ratheesh, Alvarez-Jimenez, Harrigan, Brown, Thompson, Pantelis, Berk, McGorry, Francey and Wood2023). Furthermore, several studies concluded that high daily doses of antipsychotics had deleterious effects on verbal fluency and processing speed (Élie et al., Reference Élie, Poirier, Chianetta, Durand, Grégoire and Grignon2010; Rehse et al., Reference Rehse, Bartolovic, Baum, Richter, Weisbrod and Roesch-Ely2016; Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer and Zald2007). However, the ratio of receptors that are occupied by antipsychotics is dependent on both receptor affinity and antipsychotic dose. Studies that have related dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (as derived from PET or plasma levels of antipsychotics) to cognition, also reported that high levels of occupancy were related to poor global cognitive functioning and attention in older individuals with long-term SSD (Sakurai et al., Reference Sakurai, Bies, Stroup, Keefe, Rajji, Suzuki, Mamo, Pollock, Watanabe, Mimura and Uchida2013; Uchida et al., Reference Uchida, Rajji, Mulsant, Kapur, Pollock, Graff-Guerrero, Menon and Mamo2009). More recent studies suggested lower cognitive functioning and hyperprolactinemia even above a threshold of 67% dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in people with long-term SSD (Iwata et al., Reference Iwata, Nakajima, Caravaggio, Suzuki, Uchida, Plitman, Chung, Mar, Gerretsen, Pollock, Mulsant, Rajji, Mamo and Graff-Guerrero2016; Kusudo et al., Reference Kusudo, Ochi, Nakajima, Suzuki, Mamo, Caravaggio, Mar, Gerretsen, Mimura, Pollock, Mulsant, Graff-Guerrero, Rajji and Uchida2022). The current findings suggest that high antipsychotic dopamine D2 receptor occupancy may have considerable negative effects on neurocognitive functioning also in young individuals with FEP. This underscores the importance of careful determination of the antipsychotic medication type in combination with the lowest effective dose, early on in psychosis treatment.

The dosage of antipsychotic medication in the current sample (median 9.48 ± IQR 8.16 mg olanzapine) follows the recommendations of several guidelines to prescribe the lowest effective dose, especially in people with FEP (Buchanan et al., Reference Buchanan, Kreyenbuhl, Kelly, Noel, Boggs, Fischer, Himelhoch, Fang, Peterson, Aquino and Keller2010; Correll et al., Reference Correll, Martin, Patel, Benson, Goulding, Kern-Sliwa, Joshi, Schiller and Kim2022). Findings of a recent study on medication strategies in the Netherlands indicated that 34% of the clinicians already began dose reduction approximately 4 months after remission from an FEP (Kikkert et al., Reference Kikkert, Veling, de Haan, Begemann, de Koning and Sommer2022). In our current data, negative effects of high D2 occupancy were evident even at relatively low doses, suggesting that, even in a relatively low-dose range, negative effects of higher doses can be observed, and not only dose reduction, but also the type of antipsychotic impacts cognition. Recent meta-analyses also concluded that haloperidol is among the worst-performing antipsychotics with regard to cognitive functioning, shown for both global composite scores and all studied cognitive domains (Baldez et al., Reference Baldez, Biazus, Rabelo-da-Ponte, Nogaro, Martins, Kunz and Czepielewski2021; Feber et al., Reference Feber, Peter, Chiocchia, Schneider-Thoma, Siafis, Bighelli, Hansen, Lin, Prates-Baldez, Salanti, Keefe, Engel and Leucht2024). The current study extends these findings to antipsychotics with strong dopamine affinity as a group and provides important leads for choosing antipsychotic drugs in individuals with FEP, as dopamine D2 receptor affinity may affect cognition in young people, even at low doses.

Current findings are of clinical importance, with implications for prescribing antipsychotics to individuals with an FEP. All antipsychotics have their own specific side-effect profiles, and the process of shared decision-making is the preferred strategy to choose the drug with the patient’s most favorable side effect profile (Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, de Wit, Blankers, Sommer and de Haan2018). During this process, patients need to be informed about the potential negative effects of high dopamine affinity drugs on cognition. When patients prioritize the impact on cognitive functioning, medication with low D2 receptor affinity or partial agonists may be preferred. While the European Psychiatric Association guidelines recommend second-generation antipsychotics based on their favorable cognitive profile (Vita et al., Reference Vita, Gaebel, Mucci, Sachs, Barlati, Giordano, Nibbio, Nordentoft, Wykes and Galderisi2022), this recommendation should be tailored to D2 receptor affinity, as several atypical drugs also have high dopamine affinity (i.e. risperidone, paliperidone, sulpiride, amisulpride).

Strengths and limitations

The main result of this study (i.e. the association between high D2 receptor occupancy and affinity and low global cognitive functioning) is based on a well-powered analysis (n = 278). Furthermore, participants were included shortly after diagnosis and had all achieved symptomatic remission before testing, so symptom severity was relatively low. Therefore, the potential confounding effect of other factors that may impact cognitive functioning, such as illness duration and severity of psychotic symptoms, was limited. However, participants were not randomized to the type of medication, but all regression analyses were corrected using IPTW as a statistical method that adjusts for differences in clinical and sociodemographic characteristics to limit the effects of bias by indication. While IPTW balances observed characteristics across the three D2 affinity groups, the findings may potentially still be influenced by unmeasured characteristics. Participants were recruited from 26 mental healthcare institutions throughout the Netherlands, covering different patient groups and practices, which may increase the generalizability of our findings. Another strength is that we used pharmacy dispensation data to confirm antipsychotic medication use. Most studies examining the association between the type and dose of antipsychotic medication and cognitive functioning are hampered by poor measures of medication use (i.e. self-report only), while low medication adherence has been reported in SSD (Roberts & Velligan, Reference Roberts and Velligan2011) and patients’ self-report of medication use often overestimates adherence (Jónsdóttir et al., Reference Jónsdóttir, Opjordsmoen, Birkenaes, Engh, Ringen, Vaskinn, Aamo, Friis and Andreassen2010). While still not flawless, pharmacy dispensation data are closer to the actual dose of medication taken than self-reports only. However, our study does not permit conclusions regarding causal relationships between medication use and cognitive functioning, due to its cross-sectional design. There have been some antipsychotic dose-reduction studies with initial positive results for cognitive improvement (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Kumar, Pathak, Jacob, Venkatasubramanian, Varambally and Rao2022; Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Suzuki, Remington, Bies, Abe, Graff-Guerrero, Watanabe, Mimura and Uchida2013; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Li, Li, Cui and Ning2018), but those studies were too small to stratify their analyses based on antipsychotic type. For that purpose, we need larger samples and confirmation in longitudinal studies in which patients are switched from high- to low-affinity drugs or to partial agonists. Furthermore, despite recent evidence indicating an association between anticholinergic burden and cognitive function in psychosis (Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Latreche, Fanshawe, Varvari, Zauchenberger, McGinn, Catalan, Pillinger, McGuire and McCutcheon2025), the effect of anticholinergic burden on cognitive functioning was not assessed in the current study. However, as cholinergic innervation of the brain declines steeply with age, anticholinergic burden is expected to be more troublesome for the cognitive functioning of older people than for our participants with an average age of 28 years (Orlando et al., Reference Orlando, Shine, Robbins, Rowe and O’Callaghan2023).

Conclusion

The current study found negative effects of high dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and high D2 receptor affinity antipsychotics on cognitive functioning in individuals remitted from an FEP, even at a low dose. This underscores the importance of the careful selection of the optimal antipsychotic type and dose already at the start of treatment in FEP, as medication with low dopamine D2 receptor affinity or partial agonists may minimize the negative impact on cognition.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102900.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their voluntary participation and effort in this study. The authors would also like to thank all HAMLETT and OPHELIA consortium members, and all students for their help with recruiting participants and data collection.

Funding statement

The HAMLETT study and the OPHELIA follow-up are funded by ZonMW in the Netherlands (grant numbers 80-84800-98-41015 and 636340001). The funders have no role in the study design, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Open access funding provided by Radboud University Nijmegen.

Competing interests

I.S. participates in a trial from Boehringer-Ingelheim and has received speakers’ fee from Otsuka, and a charity grant from Janssen. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.